STC-DeepLAINet: A Transformer-GCN Hybrid Deep Learning Network for Large-Scale LAI Inversion by Integrating Spatio-Temporal Correlations

Highlights

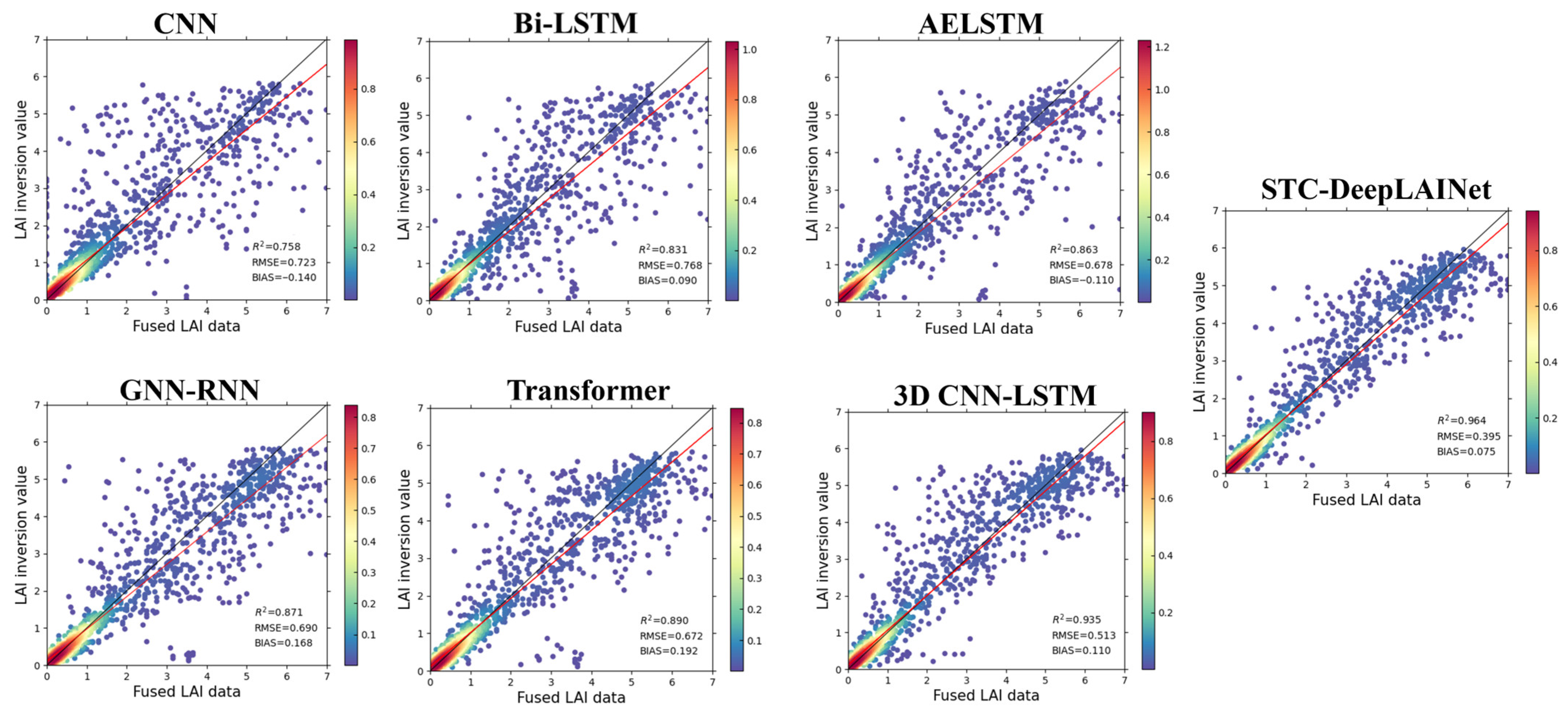

- The spatio-temporal correlation-aware deep learning network for LAI inversion, STC-DeepLAINet, outperforms eight widely used machine learning methods as well as state-of-the-art deep learning methods across all three quantitative metrics: R2, RMSE, and bias.

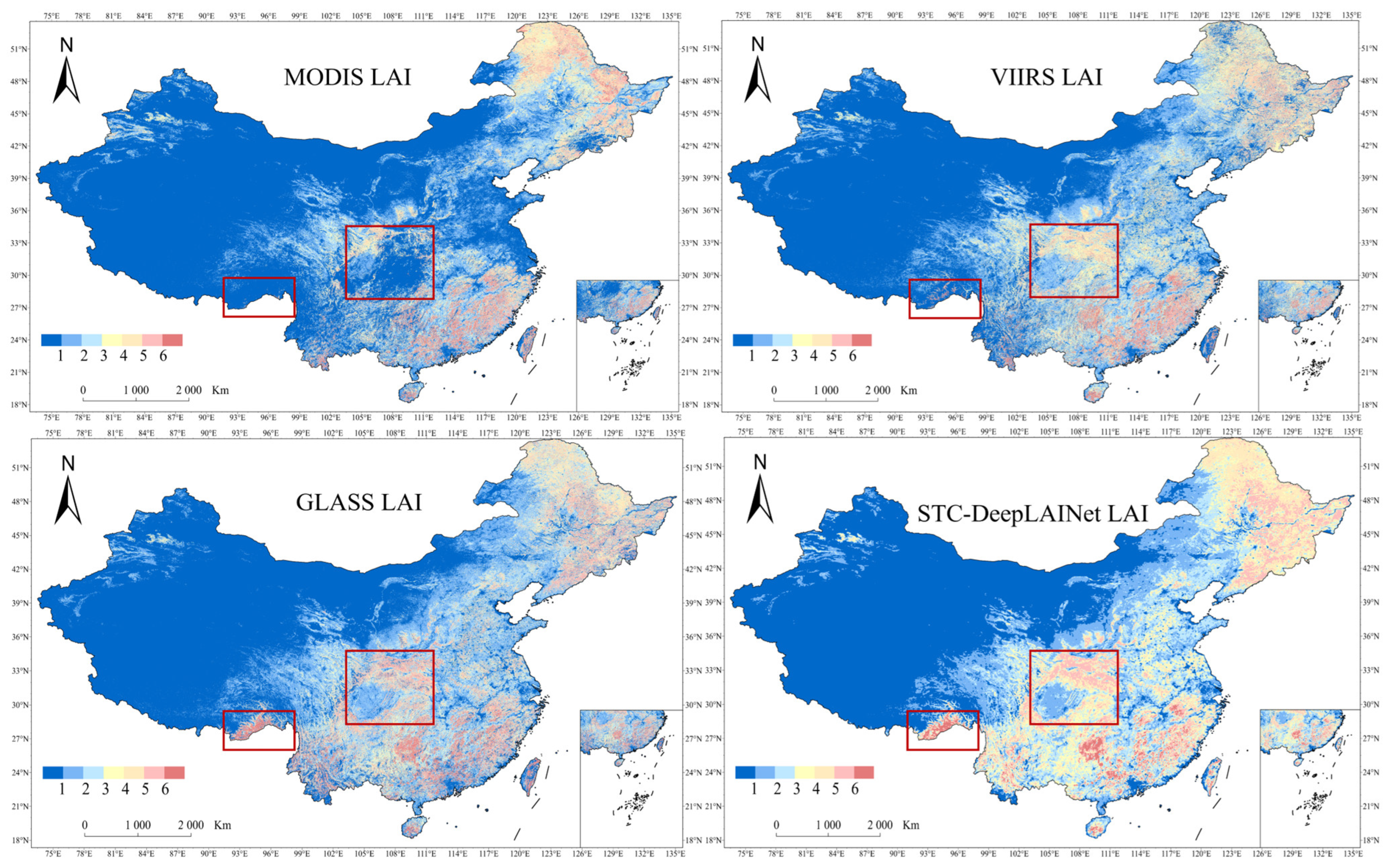

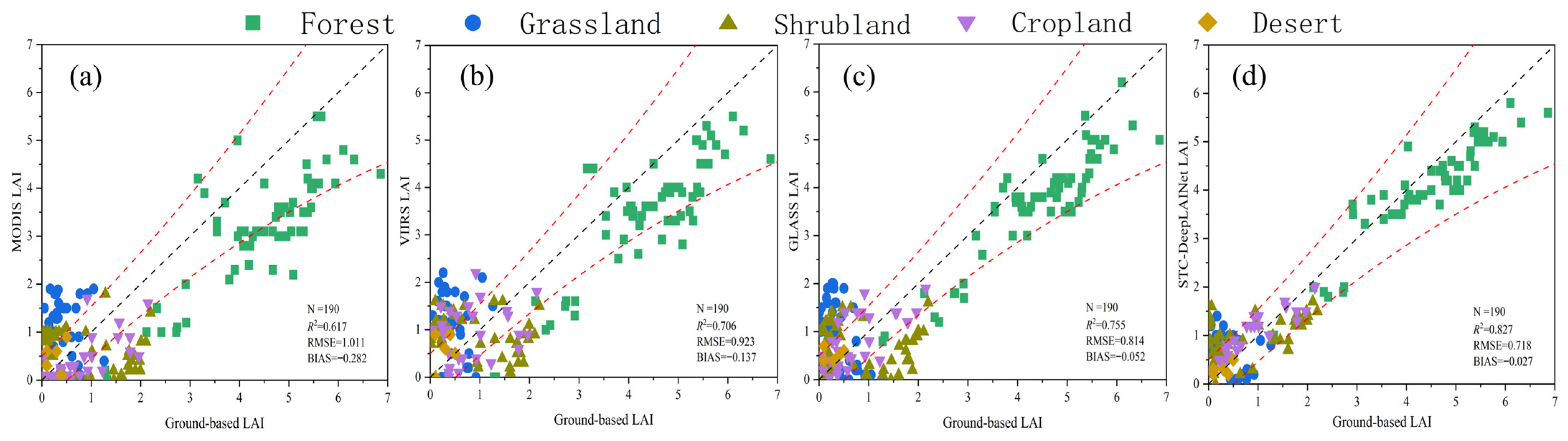

- Compared to the mainstream GLASS LAI product (prone to saturation in high LAI scenarios), STC-DeepLAINet generates LAI products with superior consistency with ground-based measurements, addressing a critical limitation of existing LAI inversion products.

- This work provides an operational framework for large-scale high-precision LAI product generation, supporting agricultural yield estimation and ecosystem carbon cycle simulation in China.

- The integration of Transformer and GCN in STC-DeepLAINet offers a new paradigm for capturing long-range spatio-temporal dependencies, advancing deep learning applications in ecological remote sensing.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- A spatio-temporal correlation attention framework is proposed, integrating Transformer-based temporal correlation mining and GCN-based spatial similarity modeling to address the limitation of capturing long-range spatio-temporal dependencies. By correlating time periods (not discrete points) and spatial slices (not pixels), it improves identifying complex spatio-temporal pattern dependencies.

- An attention-driven spatio-temporal pattern memory mechanism was designed to adaptively retrieve and leverage historically similar patterns while fusing spatio-temporal features, thereby improving LAI inversion accuracy and making it particularly suitable for complex vegetation ecosystems.

- A novel knowledge-guided loss function is designed to directly constrain the LAI inversion process, mitigating the saturation effect in LAI inversion and yielding high-precision, large-scale LAI products that offer reliable data support to agricultural and ecological research.

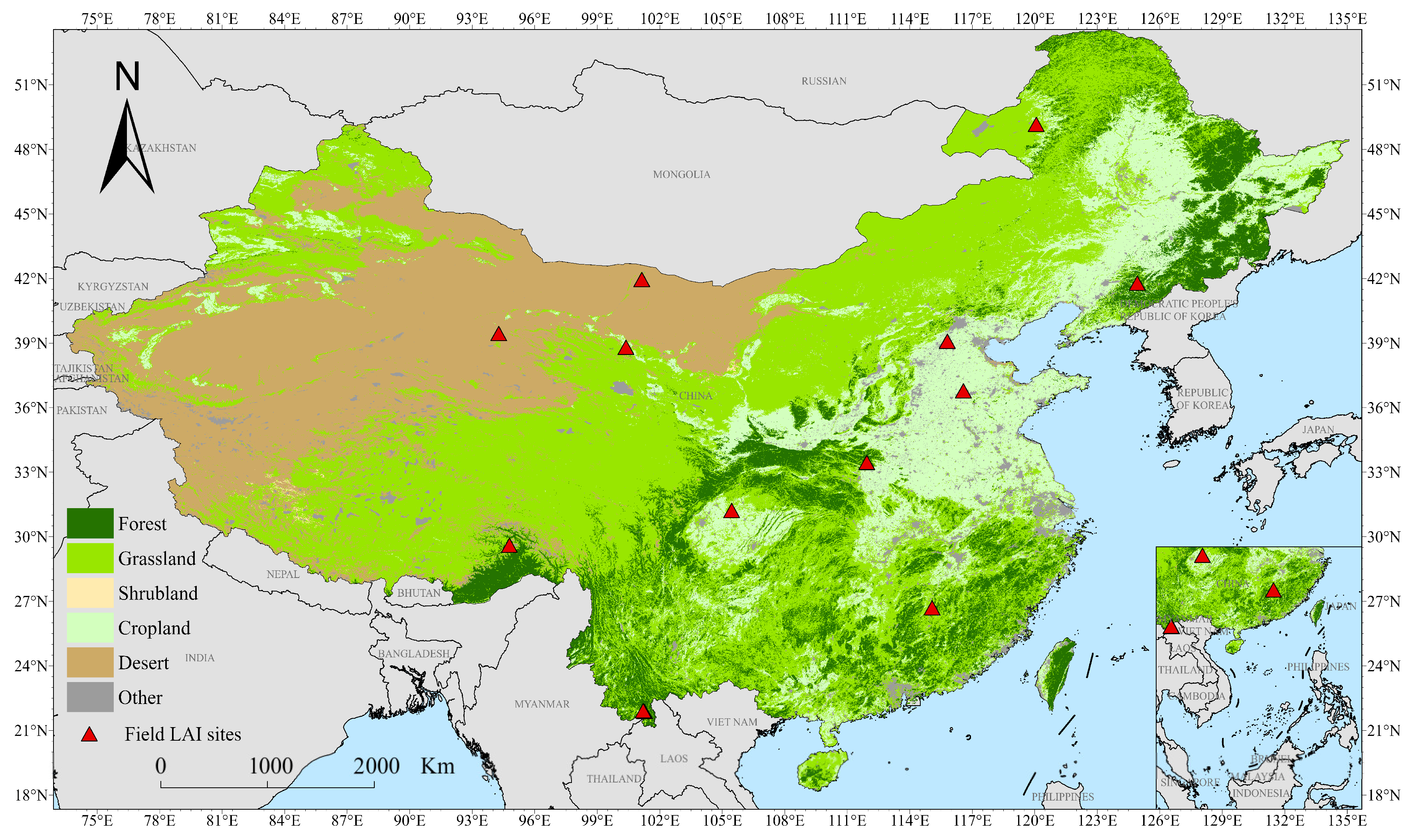

2. Materials

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Description and Processing

- (1)

- MODIS LAI

- (2)

- VIIRS LAI

- (3)

- GLASS LAI V6

- (4)

- MODIS Surface Reflectance Product

- (5)

- Ground-based LAI measurements

- (6)

- Data preprocessing

3. Methods

3.1. Overall Framework

3.2. Spectral Embedding Module

3.3. Spatio-Temporal Correlation Aware Module

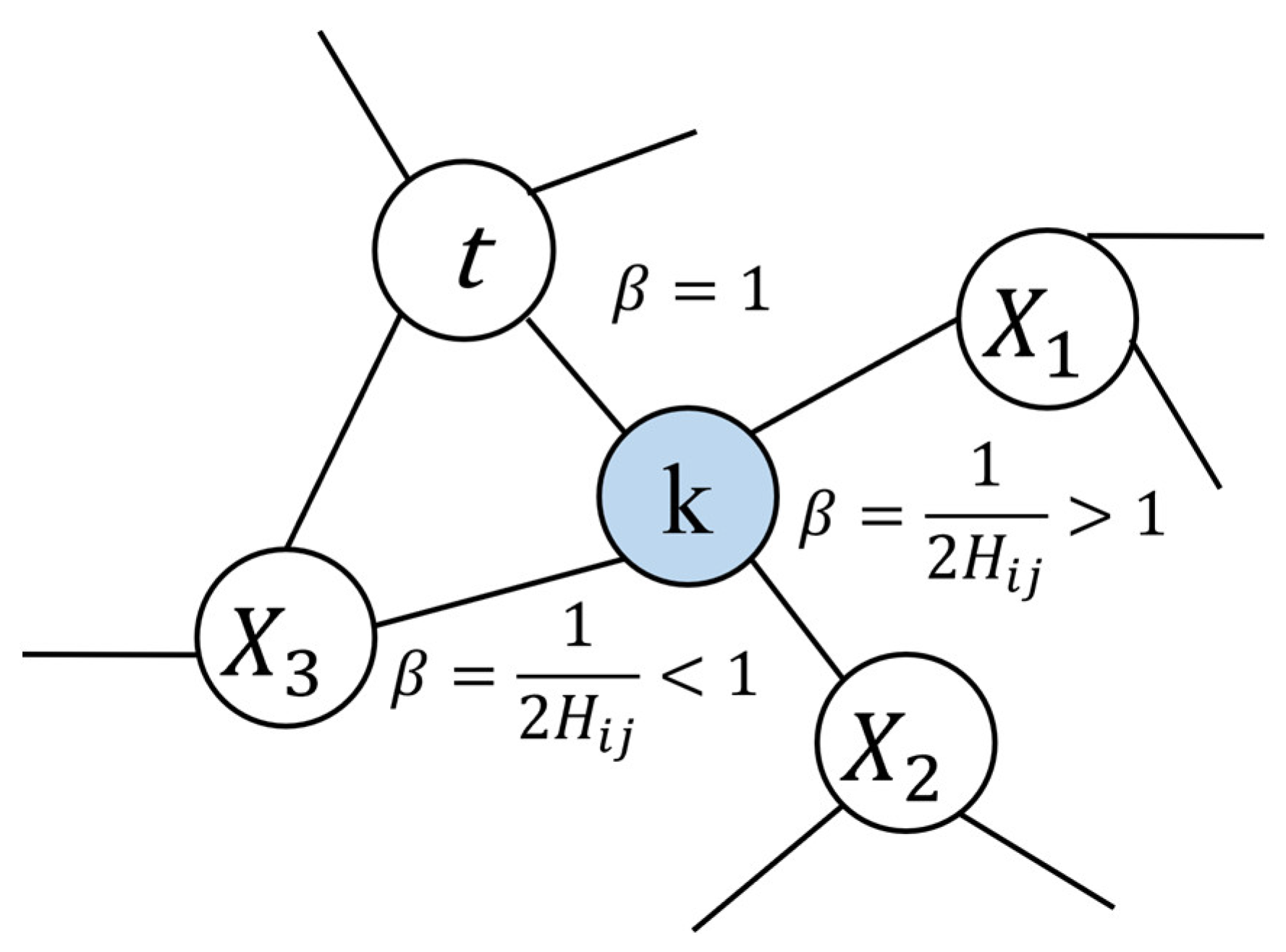

3.3.1. Spatial Correlation Aware Module

- (1)

- Capture of similar locations

- (2)

- Spatial location-aware random walk algorithm

- (3)

- Geospatial correlation calculation

- (4)

- Geospatial sparsity calculation

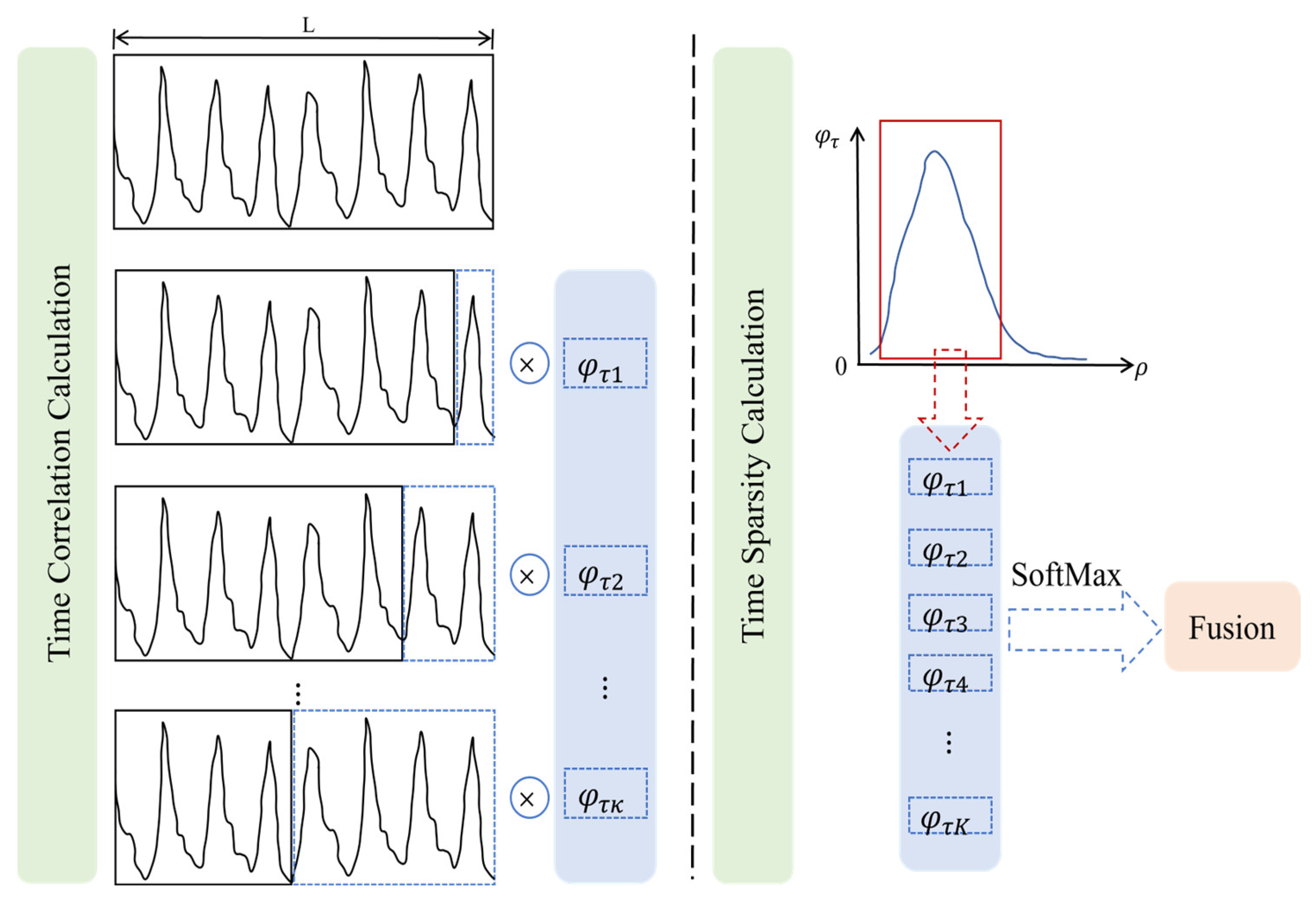

3.3.2. Temporal Correlation Aware Module

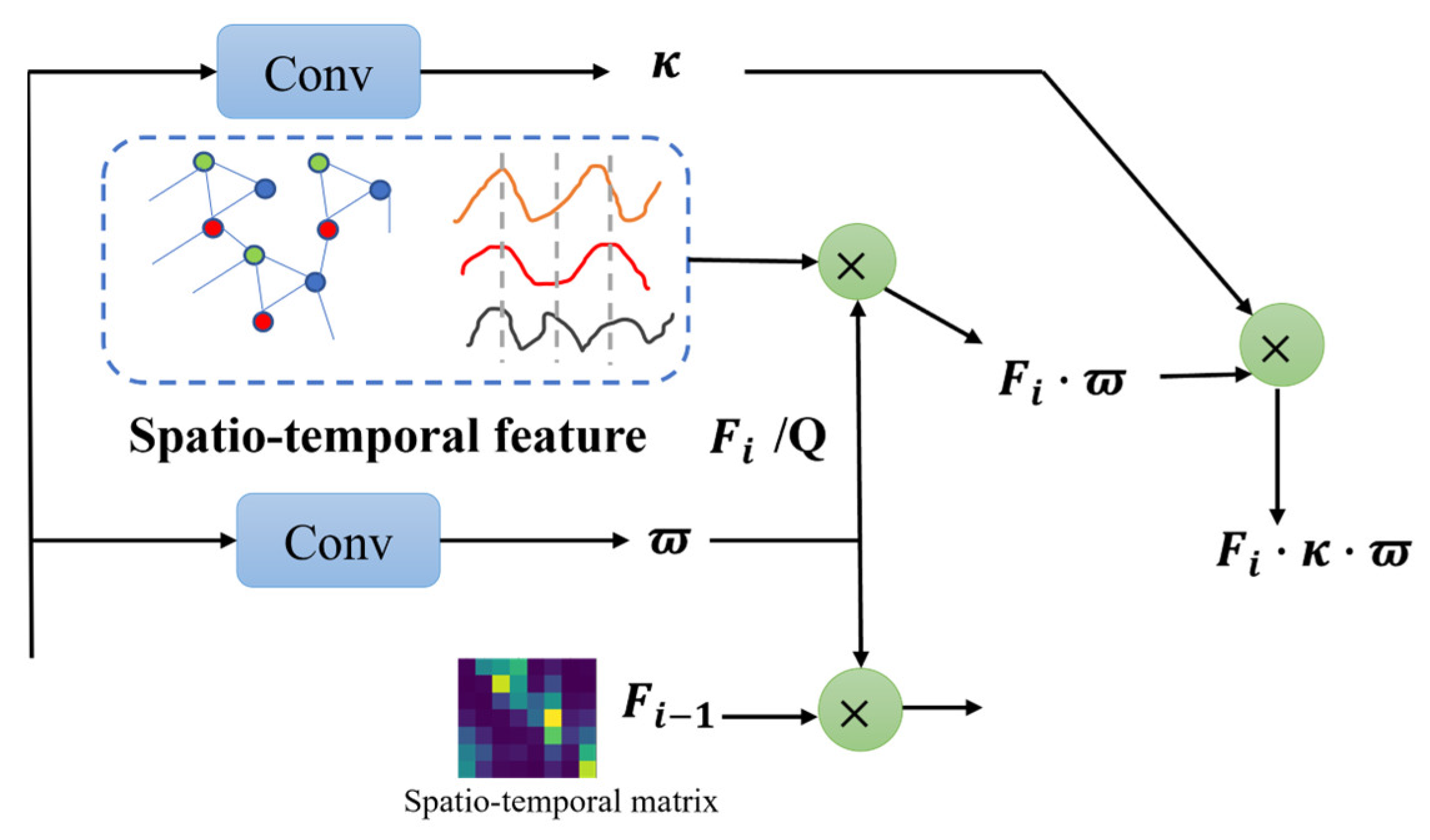

3.4. Spatio-Temporal Pattern Memory Attention Module

3.5. Knowledge-Guided Loss Function

3.6. Experimental Settings and Evaluation Metrics

3.7. Comparison Methods

- (1)

- RF [42]: An ensemble learning method based on decision trees shows robust performance in diverse time-series modeling.

- (2)

- GRNN [43]: Core algorithm of the GLASS V5 LAI product, which estimates LAI by modeling relationships between fused LAI products (MODIS, CYCLOPES) and MODIS surface reflectance.

- (3)

- CNN [44]: A spatial feature extractor for high-dimensional remote sensing imagery also services as a foundational component of our architecture.

- (4)

- Bi-LSTM [45]: It enhances traditional LSTM via forward/backward temporal dependencies, capturing past and future context in sequential data.

- (5)

- AELSTM [46]: Attention-enhanced LSTM, a network that integrates an attention mechanism into LSTM to better capture long-range temporal dependencies for vegetation LAI prediction.

- (6)

- GNN-RNN [47]: Hybrid framework combining Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) for capturing geospatial dependencies and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) for modeling temporal sequences.

- (7)

- Transformer [48]: Deep learning architecture based on self-attention (models long-range dependencies without recurrence) serves as the baseline for the proposed STC-DeepLAINet and was used to produce high-resolution 30m LAI in Jiangsu Province, China.

- (8)

- 3D CNN-LSTM [49]: Hybrid network integrating 3D CNNs and LSTM for spatio-temporal feature extraction from multidimensional satellite imagery.

4. Results

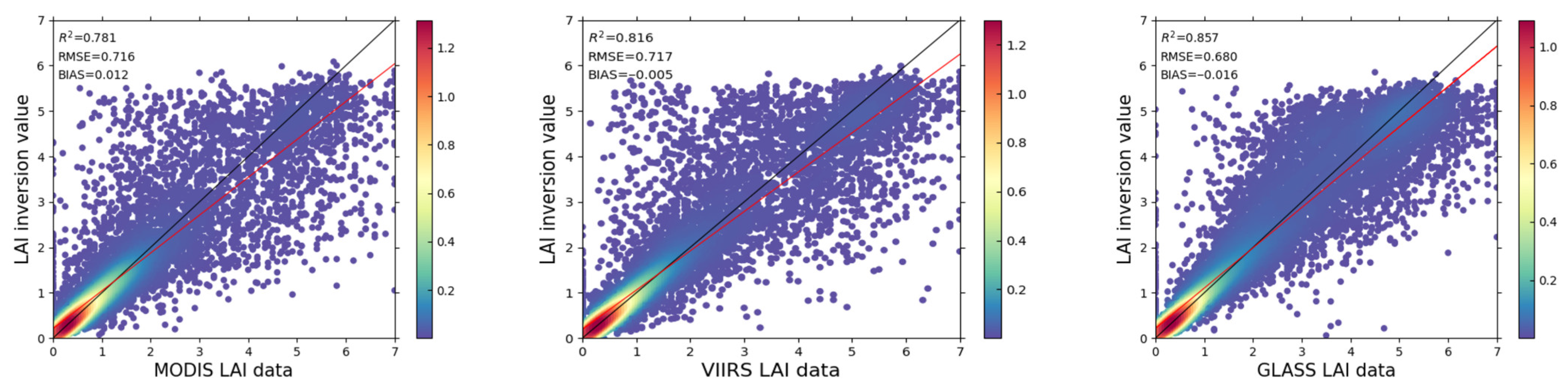

4.1. Exploratory Data Analysis of Fused LAI Training Dataset

4.2. Comparison with Competing Methods

4.3. Module Ablation Study

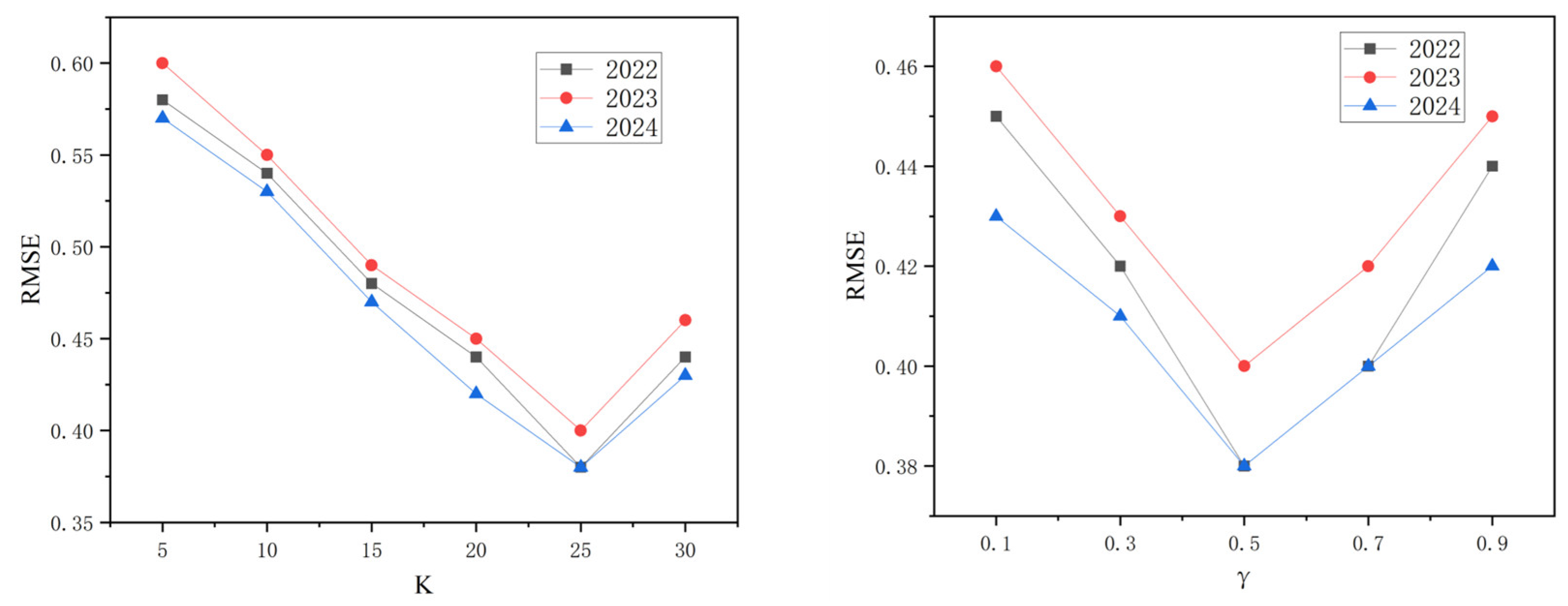

4.4. Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

4.5. Validation of LAI Products

4.6. STC-DeepLAINet’s Tolerance to Cloud/Shadow Noise

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Site Name | Year | DOY | Type | Latitude | Longitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heihe River Basin Sidaoqiao Superstation, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (http://data.tpdc.ac.cn) | 2022 | 177, 185, 193 | Shrubland | 42.0012 | 101.1374 |

| 2023 | 225, 233, 241, 249, 257, 265, 273, 281, 289, 297 | Shrubland | 42.0012 | 101.1374 | |

| 2024 | 161, 169, 177, 185, 193, 201, 209, 217, 225, 233, 241, 249, 257, 265, 273, 281, 289, 297 | Shrubland | 42.0012 | 101.1374 | |

| Yucheng Station, Shandong (http://www.nesdc.org.cn) | 2022 | 66, 101, 125, 211, 234 | Cropland | 36.8298 | 116.5709 |

| Baotianman Station, Henan (http://www.nesdc.org.cn) | 2023 | 217, 225, 233, 248 | Forest | 33.4997 | 111.9353 |

| Heihe River Basin Daman Superstation, Gansu (http://data.tpdc.ac.cn) | 2022 | 177, 185, 193, 201, 209, 217, 225, 233, 241 | Cropland | 38.8530 | 100.3760 |

| 2024 | 161, 169, 177, 185, 193, 201, 209, 217, 225 | Cropland | 38.8530 | 100.3760 | |

| Qianyanzhou Station, Jiangxi (http://www.nesdc.org.cn) | 2022 | 179, 199, 240, 250, 279 | Forest | 26.7467 | 115.0703 |

| 2023 | 32, 45, 77, 111, 137, 182, 198, 265, 281, 316 | Forest | 26.7467 | 115.0703 | |

| Xishuangbanna Station, Yunnan (http://www.nesdc.org.cn) | 2022 | 26, 57, 85, 116, 146, 177, 207, 238, 269, 299, 330 | Grassland | 21.9269 | 101.2647 |

| 2023 | 26, 57, 85, 116, 146, 177, 207, 238, 269, 299, 330 | Grassland | 21.9269 | 101.2647 | |

| 2024 | 26, 57, 86, 117, 147, 178, 208, 239, 270, 300, 331 | Grassland | 21.9269 | 101.2647 | |

| 2022 | 26, 57, 85, 116, 146, 177, 207, 238, 269, 299, 330 | Shrubland | 21.9233 | 101.2681 | |

| 2023 | 26, 57, 85, 116, 146, 177, 207, 238, 269, 299, 330 | Shrubland | 21.9233 | 101.2681 | |

| 2024 | 26, 57, 86, 117, 147, 178, 208, 239, 270, 300, 331 | Shrubland | 21.9233 | 101.2681 | |

| 2022 | 26, 57, 85, 116, 146, 177, 207, 238, 269 | Forest | 21.9650 | 101.2039 | |

| 2023 | 26, 57, 85, 116, 146, 177, 207, 238, 269 | Forest | 21.9650 | 101.2039 | |

| 2024 | 26, 57, 86, 117, 147, 178, 208, 239, 270, 300, 331 | Forest | 21.9650 | 101.2039 | |

| Dunhuang, Gansu (LAI-2200) | 2022 | 257, 265, 273, 281, 289 | Desert | 39.4912 | 94.2706 |

| Qingyuan, Liaoning (LAI-2200) | 2022 | 185, 193, 201, 209 | Forest | 41.8333 | 124.9167 |

| Hulunbuir, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (LAI-2200) | 2023 | 225, 233, 241 | Grassland | 49.2113 | 120.0681 |

| Langfang, Hebei (LAI-2200) | 2022 | 225, 233, 241 | Cropland | 39.1333 | 115.8000 |

| Mianyang, Sichuan (LAI-2200) | 2024 | 185, 193, 201 | Cropland | 31.2667 | 105.4500 |

| Nyingchi, Tibet Autonomous Region (LAI-2200) | 2023 | 193, 201, 209, 217 | Forest | 29.6500 | 94.7833 |

| Year | Strategy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SC with No SLRW | SC with SLRW | RMSE | R2 | Bias | |

| 2022 | √ | 0.45 | 0.93 | 0.10 | |

| √ | 0.41 ↓ 8.89% | 0.94 ↑ 1.08% | 0.08 ↓ 20.00% | ||

| 2023 | √ | 0.48 | 0.93 | 0.09 | |

| √ | 0.46 ↓ 4.17% | 0.94 ↑ 1.08% | 0.08 ↓ 11.11% | ||

| 2024 | √ | 0.44 | 0.94 | 0.10 | |

| √ | 0.42 ↓ 4.55% | 0.95 ↑ 1.06% | 0.09 ↓ 10.00% | ||

References

- Qi, J.; Xie, D.; Jiang, J.; Huang, H. 3D radiative transfer modeling of structurally complex forest canopies through a lightweight boundary-based description of leaf clusters. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 283, 113301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, K.; Gao, S.; Yan, G.; Ma, X.; Chen, X.; Zhu, P.; Li, J.; Gao, S.; Gastellu-Etchegorry, J.-P.; Myneni, R.B.; et al. A global systematic review of the remote sensing vegetation indices. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2025, 139, 104560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Qin, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, H.; Han, G.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, T.; Wang, B. A leaf chlorophyll vegetation index with reduced LAI effect based on Sentinel-2 multispectral red-edge information. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 236, 110500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Du, X.; Dong, T.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, M.; Zhu, J.; Yang, J. Estimation of sugarcane biomass from Sentinel-2 leaf area index using an improved SAFY model (SAFY-Sugar). Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2025, 140, 104570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability; Summary for Policymakers; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Korhonen, L.; Lang, M.; Pisek, J.; Diaz, G.M.; Korpela, I.; Xia, Z.; Haapala, H.; Maltamo, M. Comparison of semi-physical and empirical models in the estimation of boreal forest leaf area index and clumping with airborne laser scanning data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5701212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yan, K.; Liu, J.; Yang, K.; Pu, J.; Yan, G.; Heiskanen, J.; Zhu, P.; Knyazikhin, Y.; Myneni, R.B. An Insight into the Internal Consistency of MODIS Global Leaf Area Index Products. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 4411716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Liang, S. Development of the GLASS 250-m leaf area index product (version 6) from MODIS data using the bidirectional LSTM deep learning model. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 273, 112985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Démoulin, R.; Gastellu-Etchegorry, J.P.; Lefebvre, S.; Briottet, X.; Zhen, Z.; Adeline, K.; Marionneau, M.; Le Dantec, V. Modeling 3D radiative transfer for maize traits retrieval: A growth stage-dependent study on hyperspectral sensitivity to field geometry, soil moisture, and leaf biochemistry. Remote Sens. Environ. 2025, 327, 114784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallel, A.; Wang, Y.; Hedman, J.; Gastellu-Etchegorry, J.P. Canopy BRDF differentiation on LAI based on Monte Carlo Ray Tracing. Remote Sens. Environ. 2025, 327, 114785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Qin, Q.; Ren, H.; Zhang, T.; Chen, S. Red-edge band vegetation indices for leaf area index estimation from Sentinel-2/MSI imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2020, 58, 826–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myneni, R.B.; Hoffman, S.; Knyazikhin, Y.; Privette, J.L.; Glassy, J.; Tian, Y.; Wang, Y.; Song, X.; Zhang, Y.; Smith, G.R.; et al. Global products of vegetation leaf area and fraction absorbed PAR from year one of MODIS data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 83, 214–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Huang, Q.; Wu, Z.; Wu, T.; Luo, J.; Dong, W.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, D. Mapping crop leaf area index at the parcel level via inverting a radiative transfer model under spatiotemporal constraints: A case study on sugarcane. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 198, 107003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Wang, W.; Jia, C.; Liu, X. Leaf area index remote sensing based on Deep Belief Network supported by simulation data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2021, 42, 7637–7661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gao, J.; Zhang, D.; Liang, T.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Ma, Z.; Yang, J. Improved estimation of forage nitrogen in alpine grassland by integrating Sentinel-2 and SIF data. Plant Methods 2025, 21, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Yang, Y.; Peng, L.; Chen, L.; Li, W.; Zhang, W.; Chen, J. Spatio-Temporal Knowledge Graph Based Forest Fire Prediction with Multi Source Heterogeneous Data. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.; Qi, J.; Huang, H.; Li, L. Combining 3D radiative transfer model and convolutional neural network to accurately estimate forest canopy cover from very high-resolution satellite images. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 10953–10963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Jin, H.; Xie, X.; Fang, H.; Wei, D.; Li, A. Bi-LSTM model for time series leaf area index estimation using multiple satellite products. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2022, 19, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.; Feng, Y.; Cheng, W.; Mu, Z.; Wang, X. BS2T: Bottleneck Spatial-Spectral Transformer for Hyperspectral Image Classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Wang, J.; Lei, P.; Li, Y. A novel multi-step ahead forecasting model for flood based on time residual LSTM. J. Hydrol. 2023, 620, 129521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the 31st Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Shu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wen, Q.; Yang, B.; Guo, C. Pathformer: Multi-scale transformers with adaptive pathways for time series forecasting. In Proceedings of the 12th The International Conference on Learning Representations, Vienna, Austria, 7 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Jing, C.; Xu, S.; Guo, T. Attention based spatiotemporal graph attention networks for traffic flow forecasting. Inf. Sci. 2022, 607, 869–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Sun, L.; Ling, M.; Peng, Y. A survey of graph neural network based recommendation in social networks. Neurocomputing 2023, 549, 126441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Deng, K.; Ren, K.; Liu, J.; Deng, C.; Jin, Y. Deep learning in statistical downscaling for deriving high spatial resolution gridded meteorological data: A systematic review. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2024, 208, 14–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedl, M.; Sulla-Menashe, D. MODIS/Terra+Aqua Land Cover Type Yearly L3 Global 500m SIN Grid V061. NASA Land Process. Distrib. Act. Arch. Cent. 2022. Available online: https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/data/catalog/lpcloud-mcd12q1-061 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Myneni, R. VIIRS/NPP Leaf Area Index/FPAR 8-Day L4 Global 500m SIN Grid V002 [Data set]. NASA Land Process. Distrib. Act. Arch. Cent. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermote, E.F.; Ray, J.P. MODIS Surface Reflectance User’s Guide Collection [User Guide/Technical Report]; NASA Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center (LP DAAC): Sioux Falls, SD, USA, 2015; pp. 1–37. Available online: https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/data/catalog/lpcloud-mod09a1-061 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Liu, S.; Xu, Z.; Che, T.; Li, X.; Xu, T.; Ren, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, J.; Song, L.; Zhou, J.; et al. A dataset of energy, water vapor, and carbon exchange observations in oasis-desert areas from 2012 to 2021 in a typical endorheic basin. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2023, 15, 4959–4981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, J.; Yan, K.; Gao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Park, T.; Sun, X.; Weiss, M.; Knyazikhin, Y.; Myneni, R.B. Improving the MODIS LAI compositing using prior time-series information. Remote Sens. Environ. 2023, 287, 113493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román, M.O.; Justice, C.; Paynter, I.; Boucher, P.B.; Devadiga, S.; Endsley, A.; Erb, A.; Friedl, M.; Gao, H.; Giglio, L.; et al. Continuity between NASA MODIS Collection 6.1 and VIIRS Collection 2 land products. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 302, 113963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.K.; Krishna, G.; Dubey, S.R.; Chaudhuri, B.B. HybridSN: Exploring 3-D-2-D CNN feature hierarchy for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2020, 17, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoubir, A.; Missaoui, B. Graph Neural Networks with scattering transform for network anomaly detection. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 150, 110546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Han, X.; Yang, J. Estimation of leaf area index over heterogeneous regions using the vegetation type information and PROSAIL model. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2023, 16, 5405–5415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caparros-Santiago, J.A.; Rodriguez-Galiano, V.; Dash, J. Land surface phenology as indicator of global terrestrial ecosystem dynamics: A systematic review. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2021, 171, 330–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Xu, J.; Wang, J.; Long, M. Autoformer: Decomposition transformers with auto-correlation for long-term series forecasting. In Proceedings of the 35th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Online, 6–14 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, A.; Zhang, Y. An efficient spatial-temporal transformer with temporal aggregation and spatial memory for traffic forecasting. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 250, 123884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.D.; An, D.S.; Guo, X.L. The Impact of Non-Photosynthetic Vegetation on LAI Estimation by NDVI in Mixed Grassland. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, G.; Song, F.; Wen, Z.; Li, W.; Tong, L.; Kang, S. Improving chili pepper LAI prediction with TPE-2BVIs and UAV hyperspectral imagery. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 235, 110368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, P.; Xu, X.; Feng, H.; Xu, B.; Long, H.; Yang, G.; Zhao, C. Revealing the spectral bands that make generic remote estimates of leaf area index in wheat crop over various interference factors and planting conditions. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 235, 110381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulero, G.; Bonfil, D.J.; Helman, D. Wheat leaf area index retrieval from drone-derived hyperspectral and LiDAR imagery using machine learning algorithms. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2025, 372, 110648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Yao, Y.; Chen, S.; Li, Q.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Z.; Zeng, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Li, S. Improved maize leaf area index inversion combining plant height corrected resampling size and random forest model using UAV images at fine scale. Eur. J. Agron. 2024, 161, 127360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Liang, S.; Wang, J.; Chen, P.; Yin, X.; Zhang, L.; Song, J. Use of general regression neural networks for generating the GLASS leaf area index product from time-series MODIS surface reflectance. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2014, 52, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilniyaz, O.; Du, Q.; Shen, H.; He, W.; Feng, L.; Azadi, H.; Kurban, A.; Chen, X. Leaf area index estimation of pergola-trained vineyards in arid regions using classical and deep learning methods based on UAV-based RGB images. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 207, 107723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Yang, Q.; Liu, L.; Kang, Y.; Jia, X.; Chen, M.; Ghosh, R.; Xu, S.; Jiang, C.; Guan, K.; et al. A deep transfer learning framework for mapping high spatiotemporal resolution LAI. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2023, 206, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Gui, H.; Zhu, P.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, X.; Xiao, K.; Xin, Q. Predicting time series of vegetation leaf area index across North America based on climate variables for land surface modeling using attention-enhanced LSTM. Int. J. Digit. Earth. 2024, 17, 2372317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Bai, J.; Li, Z.; Ortiz-Bobea, A.; Gomes, C.P.; Assoc Advancement Artificial, I. A GNN-RNN approach for harnessing geospatial and temporal information: Application to crop yield prediction. In Proceedings of the 36th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 22 February–1 March 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P.; Zhou, K.; Fang, H. High-Resolution Seamless Mapping of the Leaf Area Index via Multisource Data and the Transformer Deep Learning Model. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 4408512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, M.; He, X.; Cheng, X.; Li, P.; Luo, H.; Zhang, L.; Tian, Z. Crop yield prediction from multi-spectral, multi-temporal remotely sensed imagery using recurrent 3D convolutional neural networks. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2021, 102, 102436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Hou, F.; Yang, J.; Guo, X. Terrain evolution of China seas and land since the Indo-China movement and characteristics of the stepped landform. Chin. J. Geophys-Ch. 2014, 57, 3968–3980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Baret, F.; Plummer, S.; Schaepman-Strub, G. An Overview of Global Leaf Area Index (LAI): Methods, Products, Validation, and Applications. Rev. Geophys. 2019, 57, 739–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazgir, O.; Zhang, R.; Dhruba, S.R.; Rahman, R.; Ghosh, S.; Pal, R. Representation of features as images with neighborhood dependencies for compatibility with convolutional neural networks. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Li, T.; Yang, Y.; Horng, S.J. Deep Air Quality Forecasting Using Hybrid Deep Learning Framework. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2021, 33, 2412–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Guo, Y.; Shangguan, H.; Li, R.; Wu, X.; Wang, A. Predicting remaining useful life of a machine based on embedded attention parallel networks. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 192, 110221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Wu, J.; Zhang, M.; Devos, P.; Botteldooren, D. Delayed Memory Unit: Modeling Temporal Dependency Through Delay Gate. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2025, 36, 10808–10818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lu, H.; Yu, L.; Yang, K. Comparison of the spatial characteristics of four remotely sensed leaf area index products over China: Direct validation and relative uncertainties. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.M.; Wang, M.Y.; Liang, M.Y.; Gao, Y.Y.; Tan, M.L.; Liu, M.Y.; Wang, X.P. Influence of terrain on MODIS and GLASS leaf area index (LAI) products in Qinling Mountains forests. Forests 2024, 15, 1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.L.; Zhang, Y.H.; Wei, S.S.; Li, W.J.; Ye, Y.C.; Sun, T.; Liu, W.W. Validation of global moderate resolution leaf area index (LAI) products over croplands in northeastern China. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 233, 111377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, K.; Pu, J.; Park, T.; Xu, B.; Zeng, Y.; Yan, G.; Weiss, M.; Knyazikhin, Y.; Myneni, R.B. Performance stability of the MODIS and VIIRS LAI algorithms inferred from analysis of long time series of products. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 260, 112438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Image | Band Name | Wavelength (nm) | Band Name | Wavelength (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOD09A1 | Band1 | 620–670 | Band5 | 1230–1250 |

| Band2 | 841–876 | Band6 | 1628–1652 | |

| Band3 | 459–479 | Band7 | 2150–2155 | |

| Band4 | 545–565 |

| Training | Validating | Testing | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years | 2019–2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 |

| Numbers | 76,988 | 38,656 | 38,180 | 37,956 | 39,306 |

| 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | Avg. | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | R2 | Bias | RMSE | R2 | Bias | RMSE | R2 | Bias | RMSE | R2 | Bias | |

| RF | 1.41 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 1.27 | 0.35 | 0.38 | 1.33 | 0.40 | 0.35 | 1.34 | 0.37 | 0.36 |

| GRNN | 1.35 | 0.41 | 0.36 | 1.38 | 0.38 | 0.32 | 1.23 | 0.45 | 0.30 | 1.32 | 0.41 | 0.33 |

| CNN | 0.72 | 0.75 | −0.14 | 0.77 | 0.74 | −0.15 | 0.67 | 0.80 | −0.13 | 0.72 | 0.76 | −0.14 |

| Bi-LSTM | 0.78 | 0.83 | 0.09 | 0.80 | 0.82 | 0.12 | 0.72 | 0.84 | 0.08 | 0.77 | 0.83 | 0.10 |

| AELSTM | 0.69 | 0.86 | −0.12 | 0.70 | 0.85 | −0.13 | 0.65 | 0.87 | −0.11 | 0.68 | 0.86 | −0.12 |

| GNN-RNN | 0.70 | 0.87 | 0.17 | 0.71 | 0.86 | 0.18 | 0.69 | 0.89 | 0.15 | 0.70 | 0.87 | 0.17 |

| Transformer | 0.66 | 0.89 | 0.18 | 0.70 | 0.86 | 0.21 | 0.68 | 0.90 | 0.20 | 0.68 | 0.88 | 0.20 |

| 3D CNN-LSTM | 0.51 | 0.94 | 0.10 | 0.53 | 0.92 | 0.13 | 0.48 | 0.95 | 0.09 | 0.51 | 0.94 | 0.11 |

| STC-DeepLAINet | 0.38 | 0.96 | 0.06 | 0.40 | 0.96 | 0.07 | 0.38 | 0.97 | 0.07 | 0.39 | 0.96 | 0.07 |

| Year | Strategy | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC | SC | MAN | KLF | RMSE | R2 | Bias | |

| Baseline | 0.66 | 0.89 | 0.18 | ||||

| √ | 0.50 ↓ 24.24% | 0.93 ↑ 4.49% | 0.12 ↓ 33.33% | ||||

| 2022 | √ | √ | 0.41 ↓ 18.00% | 0.94 ↑ 1.08% | 0.08 ↓ 33.33% | ||

| √ | √ | √ | 0.39 ↓ 4.88% | 0.95 ↑ 1.06% | 0.07 ↓ 12.50% | ||

| √ | √ | √ | √ | 0.38 ↓ 2.56% | 0.96 ↑ 1.05% | 0.06 ↓ 14.29% | |

| Baseline | 0.70 | 0.86 | 0.21 | ||||

| √ | 0.50 ↓ 28.57% | 0.91 ↑ 5.81% | 0.09 ↓ 57.14% | ||||

| 2023 | √ | √ | 0.46 ↓ 8.00% | 0.94 ↑ 3.30% | 0.08 ↓ 11.11% | ||

| √ | √ | √ | 0.42 ↓ 8.70% | 0.95 ↑ 1.06% | 0.07 ↓ 12.50% | ||

| √ | √ | √ | √ | 0.40 ↓ 4.76% | 0.96 ↑ 1.05% | 0.06 ↓ 14.29% | |

| Baseline | 0.68 | 0.90 | 0.20 | ||||

| √ | 0.46 ↓32.35% | 0.94 ↑ 4.44% | 0.11 ↓ 45.00% | ||||

| 2024 | √ | √ | 0.42 ↓ 8.70% | 0.95 ↑ 1.06% | 0.09 ↓ 18.18% | ||

| √ | √ | √ | 0.40 ↓ 4.76% | 0.96 ↑ 1.05% | 0.08 ↓ 11.11% | ||

| √ | √ | √ | √ | 0.38 ↓ 5.00% | 0.97 ↑ 1.04% | 0.07 ↓ 12.50% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, H.; Tian, T.; Geng, Q.; Li, H. STC-DeepLAINet: A Transformer-GCN Hybrid Deep Learning Network for Large-Scale LAI Inversion by Integrating Spatio-Temporal Correlations. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 4047. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244047

Wu H, Tian T, Geng Q, Li H. STC-DeepLAINet: A Transformer-GCN Hybrid Deep Learning Network for Large-Scale LAI Inversion by Integrating Spatio-Temporal Correlations. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):4047. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244047

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Huijing, Ting Tian, Qingling Geng, and Hongwei Li. 2025. "STC-DeepLAINet: A Transformer-GCN Hybrid Deep Learning Network for Large-Scale LAI Inversion by Integrating Spatio-Temporal Correlations" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 4047. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244047

APA StyleWu, H., Tian, T., Geng, Q., & Li, H. (2025). STC-DeepLAINet: A Transformer-GCN Hybrid Deep Learning Network for Large-Scale LAI Inversion by Integrating Spatio-Temporal Correlations. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 4047. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244047