A Sustainable Agricultural Development Index (SADI): Bridging Soil Health, Management, and Socioeconomic Factors

Highlights

- An index (SADI) integrating soil health, management and economic performance was developed.

- A spatial map revealed critical areas of degradation across Germany.

- SADI supports diagnosing and management strategies for unsustainable agricultural systems

- Healthy soils are associated with higher levels of economic prosperity.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Pedological and Geological Datasets Incorporated into SHI Interpretation

2.3. Land Uses Separation

2.4. Soil Site Observations

2.5. Environmental Covariates (EC)

2.5.1. Soil Environmental Covariates

- Following the methodology proposed by [32], we used the Geospatial Soil Sensing System (GEOS3) to produce the Synthetic Soil Image (SYSI) which represents the bare soil across German over the entire image collection period from 1982 to 2023. This image represents the mean reflectance of bare soil and includes six spectral bands: Blue (band 1), Green (band 2), Red (band 3), NIR (band 4), SWIR1 (band 5), and SWIR2 (band 6). This product has proven to be efficient and been widely used in studies focusing on correlation analysis and prediction of soil attributes [32,34,35].

- Relief factors were incorporated as soil covariates. These variables were generated using the TAGEE methodology proposed by [31], which derives terrain attributes from a 30 m resolution digital elevation model (DEM) obtained from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM). For consistency with other datasets, all terrain attributes were resampled to a spatial resolution of 90 m.

2.5.2. Vegetation, Climatic, Ground Cover Activity Covariates

2.6. Soil Attributes Mapping

2.7. SH Assessment and Mapping

- (i)

- selecting a minimum dataset.

- (ii)

- interpreting measured indicators.

- (iii)

- (i)

- “more is better” (MBI), represented by an upper asymptote sigmoid function, applied when higher values improve SH.

- (ii)

- “less is better” (LBI), modeled with a lower asymptote sigmoid curve, used when lower values indicate improved conditions.

- (iii)

- “optimal midpoint” (OMI), represented by a Gaussian function, where intermediate values reflect ideal SH conditions.

2.8. Validation Strategy for SHI

2.8.1. Uncertainty Assessment of Soil Attribute Proxies

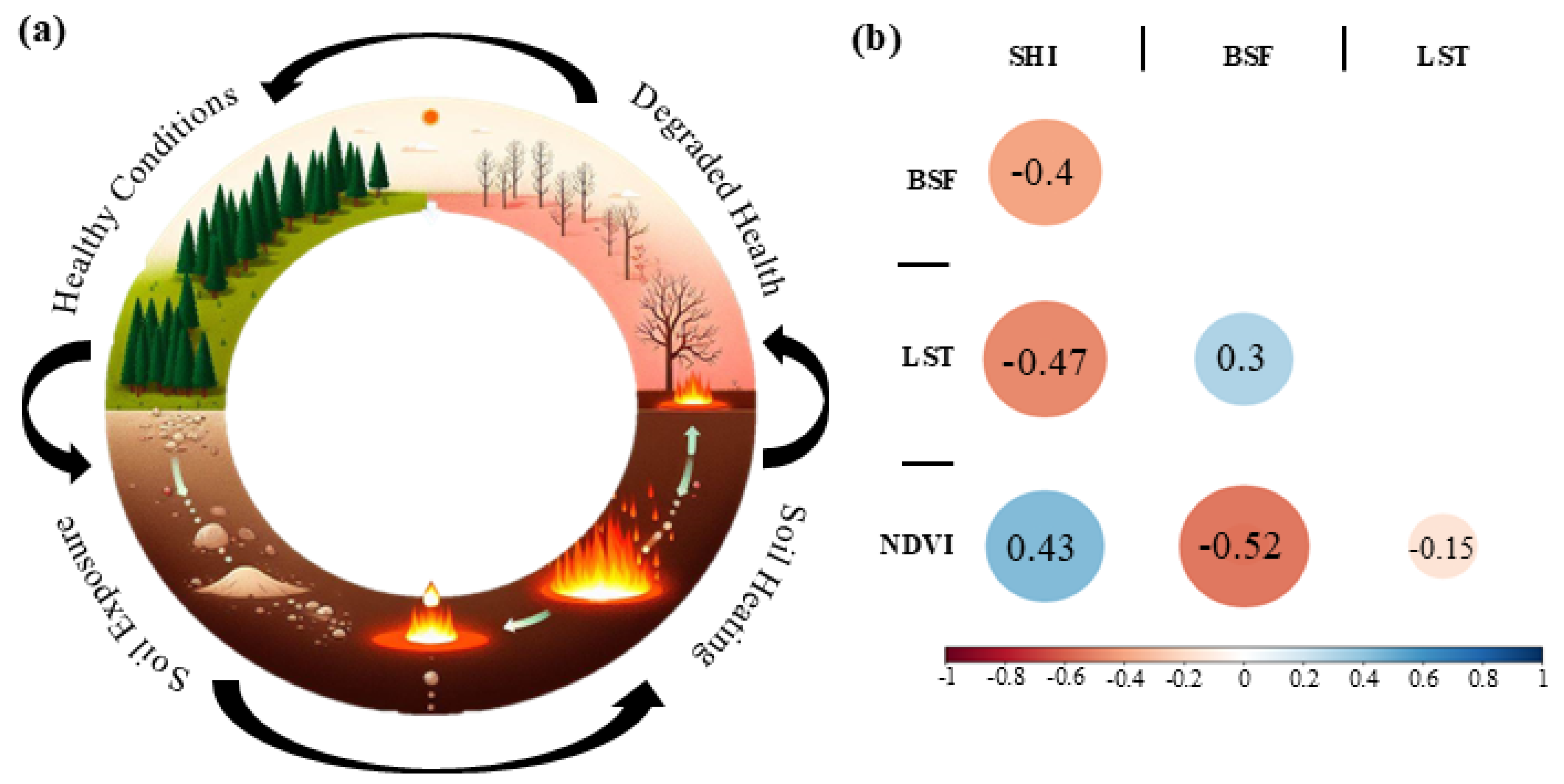

2.8.2. Spatial and Statistical Correlation with RS Sustainability Indicators

2.8.3. Correlation with Independent European Soil Degradation Products

2.9. Creation of the SADI

2.9.1. Economic, Environmental and Management Factors

2.9.2. Validation Strategy for the SADI

Independent Validation of SADI Components

Internal Consistency Assessment Using SHI Functional Components

Contextual and Explanatory Comparative Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Physical-Chemical-Biological Territorial Understanding

3.2. Uncertainty of Soil Attribute Predictions

3.3. Germany SH Assessment

3.4. SHI Validation Based on RS Indicators

3.5. External Validation Against Independent European Soil Degradation Products

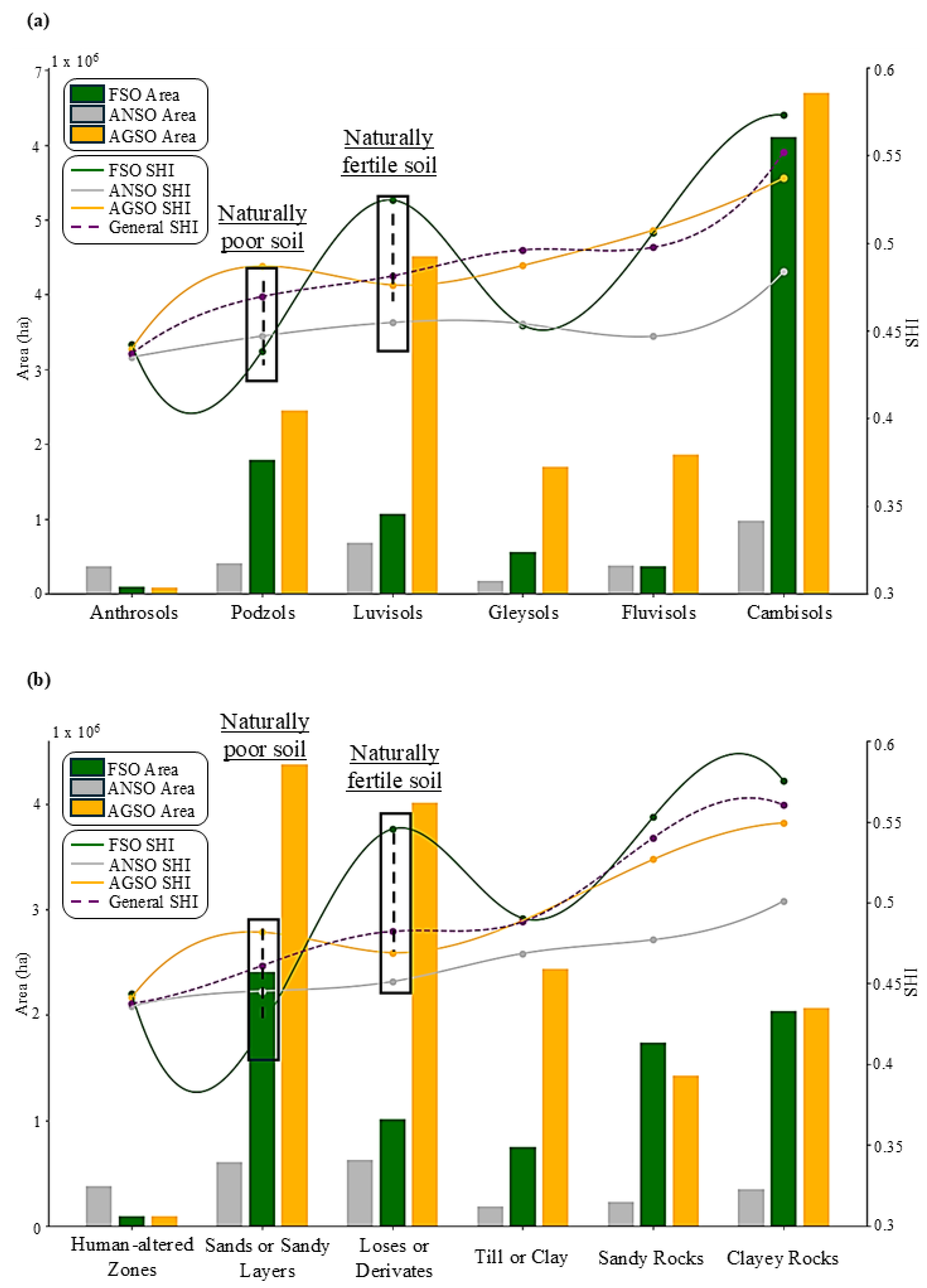

3.6. Soil and Geological Context of SHI Variations

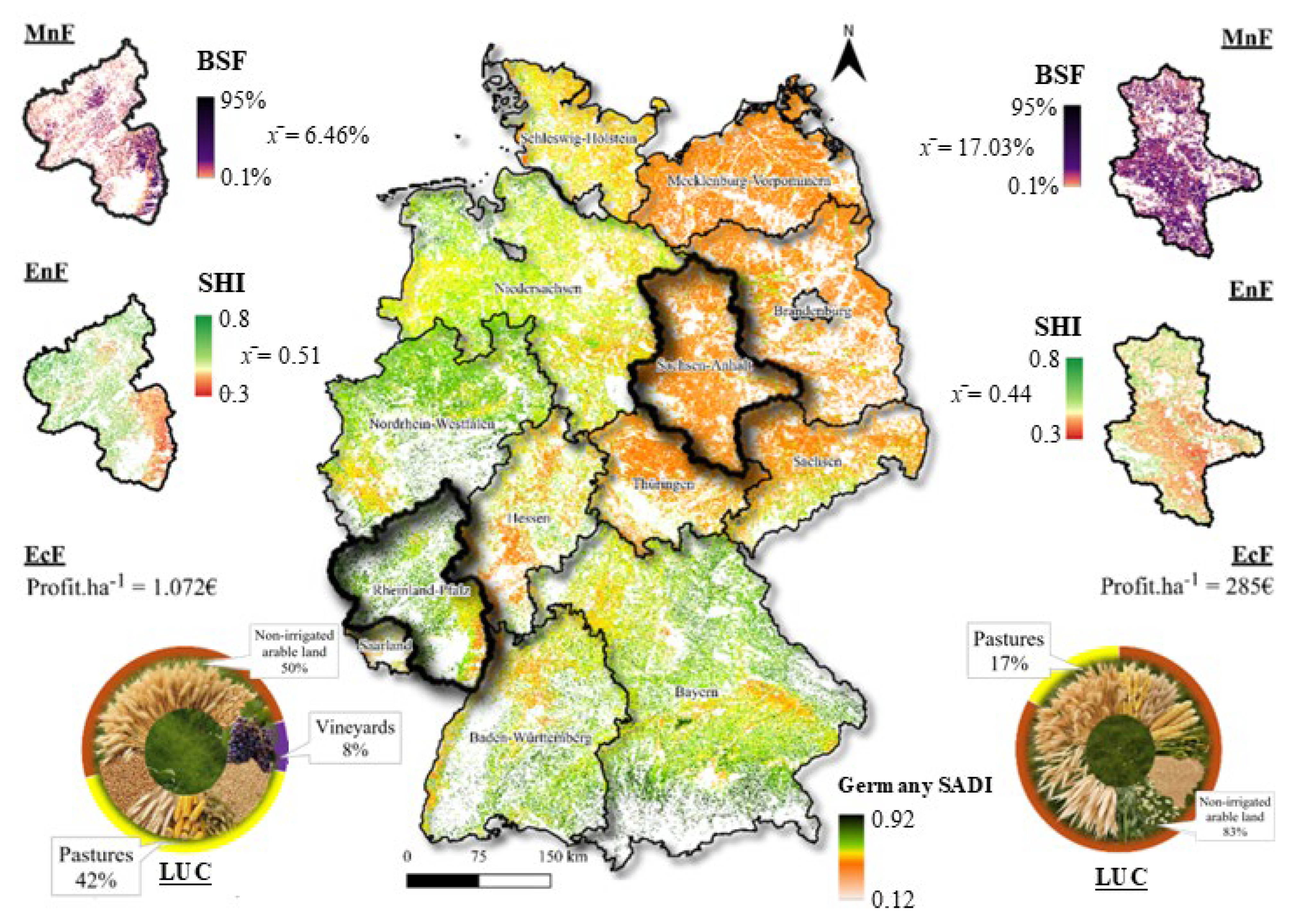

3.7. Sustainable Agricultural Development Index (SADI)

3.8. Functional Equilibrium of Soil Functions Across SADI Classes

4. Discussion

4.1. Spatial Distribution and Relationships Between Soil Attributes in Germany

4.2. Bare Soil Frequency (BSF) and Land Surface Temperature (LST) on SH Degradation

4.3. Geological and Pedological Influences on SH Dynamics in Agricultural Landscapes

4.4. Economic and Historical Influence on German SH

4.5. Interpreting the German SHI in a European SH Context

4.6. Strengths, Limitations, and Interpretative Value of SADI

4.6.1. Strengths of the SADI as an Integrative Sustainability Indicator

4.6.2. Methodological and Conceptual Limitations

4.6.3. Interpreting the SADI in the Context of German Agricultural Landscapes

4.6.4. Empirical Demonstration of SADI Interpretability: A Contrast Between Rheinland-Pfalz and Sachsen-Anhalt

4.7. Methodological Limitations, Data Gaps, and Future Directions for SH and Sustainability Monitoring in Germany

4.7.1. Structural Limitations in Soil Data and Digital Soil Mapping Approaches

4.7.2. Conceptual and Interpretative Constraints of Composite Sustainability Indices

4.8. Key Data Gaps Limiting National SH Monitoring

4.8.1. Biological Soil Indicators Remain Underrepresented

4.8.2. High-Resolution, Management-Explicit Data Are Largely Absent

4.8.3. Temporal Monitoring Remains Insufficient

4.8.4. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SH | Soil Health |

| SHI | Soil Health Index |

| RS | Remote Sensing |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| BSO | Surrounding Points |

| SOM | Soil Organic Matter |

| SADI | Sustainable Agricultural Development Index |

| ANSO | Anthropogenic Areas |

| AGSO | Agricultural Areas |

| FSO | Forest Areas |

| BD | Bulk Density |

| SOC | Soil Organic Carbon |

| K | Potassium |

| N | Nitrogen |

| CEC | Cation-exchange Capacity |

| P | Phosphorus |

| GEOS3 | Geospatial Soil Sensing System |

| SYSI | Synthetic Soil Image |

| DEM | Digital Elevation Model |

| MAT | Mean Annual Temperature |

| AP | Annual Precipitation |

| TAR | Temperature Annual Range |

| OS | Seasonal Precipitation |

| LST | Land Surface Temperature |

| GEE | Google Earth Engine |

| MIB | More is Better |

| LIB | Less is Better |

| OMI | Optimal Midpoint |

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| BSF | Bare Soil Frequency |

| EcF | Economic Factor |

| EnF | Environmental Factor |

| MnF | Management Factor |

| CTS | Conventional Tillage Systems |

| WG | West Germany |

| EG | East Germany |

| DSM | Digital Soil Mapping |

References

- Smith, P.; Poch, R.M.; Lobb, D.A.; Bhattacharyya, R.; Alloush, G.; Eudoxie, G.D.; Anjos, L.H.C.; Castellano, M.; Ndzana, G.M.; Chenu, C.; et al. Status of the World’s Soils. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2024, 49, 73–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chure, G.; Banks, R.A.; Flamholz, A.I.; Sarai, N.S.; Kamb, M.; Lopez-Gomez, I.; Bar-On, Y.M.; Milo, R.; Phillips, R. The Anthropocene by the Numbers: A Quantitative Snapshot of Humanity’s Influence on the Planet. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2101.09620. [Google Scholar]

- Molotoks, A.; Smith, P.; Dawson, T.P. Impacts of Land Use, Population, and Climate Change on Global Food Security. Food Energy Secur. 2021, 10, e261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcon, W.P.; Naylor, R.L.; Shankar, N.D. Rethinking Global Food Demand for 2050. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2022, 48, 921–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; Bossio, D.A.; Kögel-Knabner, I.; Rillig, M.C. The Concept and Future Prospects of Soil Health. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 544–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Liu, K. Cropping Systems in Agriculture and Their Impact on Soil Health-A Review. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 23, e01118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bünemann, E.K.; Bongiorno, G.; Bai, Z.; Creamer, R.E.; De Deyn, G.; de Goede, R.; Fleskens, L.; Geissen, V.; Kuyper, T.W.; Mäder, P.; et al. Soil Quality—A Critical Review. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2018, 120, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, J.W.; Coleman, D.C.; Bezdicek, D.F.; Stewart, B.A. Defining Soil Quality for a Sustainable Environment. In Defining Soil Quality for a Sustainable Environment; Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 2015; pp. 1–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, A.W. Review: The Economics of Soil Health. Food Policy 2018, 80, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouma, J.; Bonfante, A.; Basile, A.; van Tol, J.; Hack-ten Broeke, M.J.D.; Mulder, M.; Heinen, M.; Rossiter, D.G.; Poggio, L.; Hirmas, D.R. How Can Pedology and Soil Classification Contribute towards Sustainable Development as a Data Source and Information Carrier? Geoderma 2022, 424, 115988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norfleet, M.L.; Ditzler, C.A.; Puckett, W.E.; Grossman, R.B.; Shaw, J.N. Soil quality and its relationship to pedology. Soil Sci. 2003, 168, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhos, K.; Szabó, S.; Ladányi, M. Explore the Influence of Soil Quality on Crop Yield Using Statistically-Derived Pedological Indicators. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 63, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fausak, L.K.; Bridson, N.; Diaz-Osorio, F.; Jassal, R.S.; Lavkulich, L.M. Soil Health—A Perspective. Front. Soil Sci. 2024, 4, 1462428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfante, A.; Terribile, F.; Bouma, J. Refining Physical Aspects of Soil Quality and Soil Health When Exploring the Effects of Soil Degradation and Climate Change on Biomass Production: An Italian Case Study. Soil 2019, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunwald, S.; Vasques, G.M.; Rivero, R.G. Fusion of Soil and Remote Sensing Data to Model Soil Properties. Adv. Agron. 2015, 131, 1–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhen, J.; Hu, W.; Chen, S.; Lizaga, I.; Zeraatpisheh, M.; Yang, X. Remote Sensing of Soil Degradation: Progress and Perspective. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2023, 11, 429–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poppiel, R.R.; Cherubin, M.R.; Novais, J.J.M.; Demattê, J.A.M. Soil Health in Latin America and the Caribbean. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.; Tiwari, R.K.; Tiwari, S.P. A Deep Learning Multi-Layer Perceptron and Remote Sensing Approach for Soil Health Based Crop Yield Estimation. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 113, 102959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi Aqdam, K.; Rezapour, S.; Asadzadeh, F.; Nouri, A. An Integrated Approach for Estimating Soil Health: Incorporating Digital Elevation Models and Remote Sensing of Vegetation. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 210, 107922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savin, I.Y.; Zhogolev, A.V.; Prudnikova, E.Y. Modern Trends and Problems of Soil Mapping. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2019, 52, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Yang, L.; Zhang, L.; Pu, Y.; Yang, C.; Wu, Q.; Cai, Y.; Shen, F.; Zhou, C. A Review on Digital Mapping of Soil Carbon in Cropland: Progress, Challenge, and Prospect. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 123004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piikki, K.; Wetterlind, J.; Söderström, M.; Stenberg, B. Perspectives on Validation in Digital Soil Mapping of Continuous Attributes—A Review. Soil Use Manag. 2021, 37, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sklenicka, P.; Zouhar, J.; Molnarova, K.J.; Vlasak, J.; Kottova, B.; Petrzelka, P.; Gebhart, M.; Walmsley, A. Trends of Soil Degradation: Does the Socio-Economic Status of Land Owners and Land Users Matter? Land Use Policy 2020, 95, 103992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambon, I.; Benedetti, A.; Ferrara, C.; Salvati, L. Soil Matters? A Multivariate Analysis of Socioeconomic Constraints to Urban Expansion in Mediterranean Europe. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 146, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peel, M.C.; Finlayson, B.L.; Mcmahon, T.A. Updated World Map of the Koppen-Geiger Climate Classification. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2007, 11, 1633–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BGR Soil Map of the Federal Republic of Germany 1:1,000,000. Available online: https://inspire-geoportal.ec.europa.eu/srv/api/records/A95A723E-1274-4601-9E60-27079436F1F3 (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- BGR Geoportal Gruppen Der Bodenausgangsgesteine in Deutschland 1:5,000,000. Available online: https://geoportal.bgr.de/mapapps/resources/apps/geoportal/index.html?lang=de#/datasets/portal/30D75B66-DB78-4298-B80F-B7AFBD798DAE (accessed on 4 July 2024).

- CORINE Land Cover 2018 (Raster 100 m), Europe, 6-Yearly—Version 2020_20u1. 2020. Available online: https://sdi.eea.europa.eu/catalogue/copernicus/api/records/960998c1-1870-4e82-8051-6485205ebbac?language=all (accessed on 31 July 2024).

- McBratney, A.B.; Mendonça Santos, M.L.; Minasny, B. On Digital Soil Mapping. Geoderma 2003, 117, 3–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijmans, R.J.; Cameron, S.E.; Parra, J.L.; Jones, P.G.; Jarvis, A. Very High Resolution Interpolated Climate Surfaces for Global Land Areas. Int. J. Climatol. 2005, 25, 1965–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safanelli, J.L.; Poppiel, R.R.; Chimelo Ruiz, L.F.; Bonfatti, B.R.; de Oliveira Mello, F.A.; Rizzo, R.; Demattê, J.A.M. Terrain Analysis in Google Earth Engine: A Method Adapted for High-Performance Global-Scale Analysis. ISPRS Int. J. Geoinf. 2020, 9, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demattê, J.A.M.; Fongaro, C.T.; Rizzo, R.; Safanelli, J.L. Geospatial Soil Sensing System (GEOS3): A Powerful Data Mining Procedure to Retrieve Soil Spectral Reflectance from Satellite Images. Remote Sens Environ. 2018, 212, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermida, S.L.; Soares, P.; Mantas, V.; Göttsche, F.M.; Trigo, I.F. Google Earth Engine Open-Source Code for Land Surface Temperature Estimation from the Landsat Series. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho Mendes, I.; Martinhão Gomes Sousa, D.; Dario Dantas, O.; Alves Castro Lopes, A.; Bueno Reis Junior, F.; Ines Oliveira, M.; Montandon Chaer, G. Soil Quality and Grain Yield: A Win–Win Combination in Clayey Tropical Oxisols. Geoderma 2021, 388, 114880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvero, N.E.Q.; Demattê, J.A.M.; Amorim, M.T.A.; dos Santos, N.V.; Rizzo, R.; Safanelli, J.L.; Poppiel, R.R.; de Sousa Mendes, W.; Bonfatti, B.R. Soil Variability and Quantification Based on Sentinel-2 and Landsat-8 Bare Soil Images: A Comparison. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 252, 112117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas, J.T.F.; Demattê, J.A.M.; Rosin, N.A.; dos Anjos Bartsch, B.; Poppiel, R.R.; Rodriguez-Albarracin, H.S.; Novais, J.J.M.; Pavinato, P.S.; Ma, Y.; Mello, D.C.D.; et al. Geotechnologies on the Phosphorus Stocks Determination in Tropical Soils: General Impacts on Society. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 938, 173537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherubin, M.R.; Karlen, D.L.; Cerri, C.E.P.; Franco, A.L.C.; Tormena, C.A.; Davies, C.A.; Cerri, C.C. Soil Quality Indexing Strategies for Evaluating Sugarcane Expansion in Brazil. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinot, O.; Levy, G.J.; Steinberger, Y.; Svoray, T.; Eshel, G. Soil Health Assessment: A Critical Review of Current Methodologies and a Proposed New Approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 648, 1484–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.; Feng, G.; Paul, V.; Adeli, A.; Brooks, J.P. Soil Health Assessment Methods: Progress, Applications and Comparison. Adv. Agron. 2022, 172, 129–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, H.R.P.; Bach, E.M.; Bartz, M.L.C.; Bennett, J.M.; Beugnon, R.; Briones, M.J.I.; Brown, G.G.; Ferlian, O.; Gongalsky, K.B.; Guerra, C.A.; et al. Global Data on Earthworm Abundance, Biomass, Diversity and Corresponding Environmental Properties. Sci. Data 2021, 8, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piron, D.; Boizard, H.; Heddadj, D.; Pérès, G.; Hallaire, V.; Cluzeau, D. Indicators of Earthworm Bioturbation to Improve Visual Assessment of Soil Structure. Soil Tillage Res. 2017, 173, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, K.; Hartemink, A.E. Linking Soils to Ecosystem Services—A Global Review. Geoderma 2016, 262, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobnik, T.; Greiner, L.; Keller, A.; Grêt-Regamey, A. Soil Quality Indicators—From Soil Functions to Ecosystem Services. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 94, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.C.R.; Brussaard, L.; Totola, M.R.; Hoogmoed, W.B.; de Goede, R.G.M. A Functional Evaluation of Three Indicator Sets for Assessing Soil Quality. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2013, 64, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldoni, H.; Tavares, T.R.; Brasco, T.L.; Cherubin, M.R.; de Carvalho, H.W.P.; Magalhães, P.S.G.; do Amaral, L.R. Temporal Evaluation of Soil Chemical Quality Using VNIR and XRF Spectroscopies. Soil Tillage Res. 2024, 240, 106087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prăvălie, R.; Borrelli, P.; Panagos, P.; Ballabio, C.; Lugato, E.; Chappell, A.; Miguez-Macho, G.; Maggi, F.; Peng, J.; Niculiță, M.; et al. A Unifying Modelling of Multiple Land Degradation Pathways in Europe. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panagos, P.; Broothaerts, N.; Ballabio, C.; Orgiazzi, A.; De Rosa, D.; Borrelli, P.; Liakos, L.; Vieira, D.; Van Eynde, E.; Arias Navarro, C.; et al. How the EU Soil Observatory Is Providing Solid Science for Healthy Soils. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2024, 75, e13507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BMEL—Statistik: Buchführungsergebnisse Landwirtschaft 2021/22. Available online: https://www.bmel-statistik.de/landwirtschaft/testbetriebsnetz/testbetriebsnetz-landwirtschaft-buchfuehrungsergebnisse/archiv-buchfuehrungsergebnisse-landwirtschaft/buchfuehrungsergebnisse-landwirtschaft-2021/22 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- De Sousa, G.P.B.; Bellinaso, H.; Rosas, J.T.F.; de Mello, D.C.; Rosin, N.A.; Amorim, M.T.A.; dos Anjos Bartsch, B.; Cardoso, M.C.; Mallah, S.; Francelino, M.R.; et al. Assessing Soil Degradation in Brazilian Agriculture by a Remote Sensing Approach to Monitor Bare Soil Frequency: Impact on Soil Carbon. Soil Adv. 2024, 2, 100011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safanelli, J.L.; Chabrillat, S.; Ben-Dor, E.; Demattê, J.A.M. Multispectral Models from Bare Soil Composites for Mapping Topsoil Properties over Europe. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayão, V.M.; dos Santos, N.V.; de Sousa Mendes, W.; Marques, K.P.P.; Safanelli, J.L.; Poppiel, R.R.; Demattê, J.A.M. Land Use/Land Cover Changes and Bare Soil Surface Temperature Monitoring in Southeast Brazil. Geoderma Reg. 2020, 22, e00313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, C.M.; Demattê, J.A.M.; Mello, F.A.O.; Rosas, J.T.F.; Tayebi, M.; Bellinaso, H.; Greschuk, L.T.; Albarracín, H.S.R.; Ostovari, Y. Soil Degradation Detected by Temporal Satellite Image in São Paulo State, Brazil. J. South Am. Earth Sci. 2022, 120, 104036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ren, T.; Li, Y.; Chen, N.; Yin, Q.; Li, M.; Liu, H.; Liu, G. Organic Materials with High C/N Ratio: More Beneficial to Soil Improvement and Soil Health. Biotechnol. Lett. 2022, 44, 1415–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, E.; Tuller, M.; Moldrup, P.; de Jonge, L.W. Clay Content and Mineralogy, Organic Carbon and Cation Exchange Capacity Affect Water Vapour Sorption Hysteresis of Soil. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2020, 71, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Marhan, S.; Billen, N.; Stahr, K. Soil Organic-Carbon and Total Nitrogen Stocks as Affected by Different Land Uses in Baden-Württemberg (Southwest Germany). J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2009, 172, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrumpf, M.; Kaiser, K.; Schulze, E.D. Soil Organic Carbon and Total Nitrogen Gains in an Old Growth Deciduous Forest in Germany. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e89364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solly, E.F.; Weber, V.; Zimmermann, S.; Walthert, L.; Hagedorn, F.; Schmidt, M.W.I. A Critical Evaluation of the Relationship Between the Effective Cation Exchange Capacity and Soil Organic Carbon Content in Swiss Forest Soils. Front. For. Glob. Change 2020, 3, 566869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuzugullu, O.; Lorenz, F.; Fröhlich, P.; Liebisch, F. Understanding Fields by Remote Sensing: Soil Zoning and Property Mapping. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnini, M.; Marchesini, I.; Zucchini, A. Geo-LiM: A New Geo-Lithological Map for Central Europe (Germany, France, Switzerland, Austria, Slovenia, and Northern Italy) as a Tool for the Estimation of Atmospheric CO2 Consumption. J. Maps 2020, 16, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, W.R.; Foss, J.E. Contributions of Clay and Organic Matter to the Cation Exchange Capacity of Maryland Soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1972, 36, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Breemen, N.; Buurman, P. Soil Formation; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikora, L.J.; Stott, D.E. Soil Organic Carbon and Nitrogen. Methods Assess. Soil Qual. 2015, 49, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witzgall, K.; Vidal, A.; Schubert, D.I.; Höschen, C.; Schweizer, S.A.; Buegger, F.; Pouteau, V.; Chenu, C.; Mueller, C.W. Particulate Organic Matter as a Functional Soil Component for Persistent Soil Organic Carbon. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerke, J. The Central Role of Soil Organic Matter in Soil Fertility and Carbon Storage. Soil Syst. 2022, 6, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Chen, S.; Qin, X.; Baumann, F.; Scholten, T.; Zhou, Z.; Sun, W.; Zhang, T.; Ren, J.; Qin, D. Storage, Patterns, and Control of Soil Organic Carbon and Nitrogen in the Northeastern Margin of the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau. Environ. Res. Lett. 2012, 7, 035401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breuer, L.; Huisman, J.A.; Keller, T.; Frede, H.G. Impact of a Conversion from Cropland to Grassland on C and N Storage and Related Soil Properties: Analysis of a 60-Year Chronosequence. Geoderma 2006, 133, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enters, D.; Lücke, A.; Zolitschka, B. Effects of Land-Use Change on Deposition and Composition of Organic Matter in Frickenhauser See, Northern Bavaria, Germany. Sci. Total Environ. 2006, 369, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulder, C.; Hettelingh, J.P.; Montanarella, L.; Pasimeni, M.R.; Posch, M.; Voigt, W.; Zurlini, G. Chemical Footprints of Anthropogenic Nitrogen Deposition on Recent Soil C: N Ratios in Europe. Biogeosciences 2015, 12, 4113–4119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matschullat, J.; Reimann, C.; Birke, M.; dos Santos Carvalho, D.; Albanese, S.; Anderson, M.; Baritz, R.; Batista, M.J.; Bel-Ian, A.; Cicchella, D.; et al. GEMAS: CNS Concentrations and C/N Ratios in European Agricultural Soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 627, 975–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behrens, T.; Scholten, T. Digital Soil Mapping in Germany—A Review. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2006, 169, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadoux, A.M.J.C.; Brus, D.J.; Heuvelink, G.B.M. Sampling Design Optimization for Soil Mapping with Random Forest. Geoderma 2019, 355, 113913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballabio, C.; Panagos, P.; Monatanarella, L. Mapping Topsoil Physical Properties at European Scale Using the LUCAS Database. Geoderma 2016, 261, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabian, C.; Reimann, C.; Fabian, K.; Birke, M.; Baritz, R.; Haslinger, E.; Albanese, S.; Andersson, M.; Batista, M.J.; Bel-lan, A.; et al. GEMAS: Spatial Distribution of the PH of European Agricultural and Grazing Land Soil. Appl. Geochem. 2014, 48, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, T.S.; Dechow, R.; Flessa, H. Inventory and Assessment of PH in Cropland and Grassland Soils in Germany. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2022, 185, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, P.; Ramankutty, N.; Bennett, E.M.; Donner, S.D. Characterizing the Spatial Patterns of Global Fertilizer Application and Manure Production. Earth Interact. 2010, 14, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, G.; Guicharnaud, R.A.; Tóth, B.; Hermann, T. Phosphorus Levels in Croplands of the European Union with Implications for P Fertilizer Use. Eur. J. Agron. 2014, 55, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, R.W.; Noble, A.; Pletnyakov, P.; Haygarth, P.M. A Global Database of Soil Plant Available Phosphorus. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilburne, L.; Helfenstein, A.; Heuvelink, G.B.M.; Eger, A. Interpreting and Evaluating Digital Soil Mapping Prediction Uncertainty: A Case Study Using Texture from SoilGrids. Geoderma 2024, 450, 117052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Arrouays, D.; Leatitia Mulder, V.; Poggio, L.; Minasny, B.; Roudier, P.; Libohova, Z.; Lagacherie, P.; Shi, Z.; Hannam, J.; et al. Digital Mapping of GlobalSoilMap Soil Properties at a Broad Scale: A Review. Geoderma 2022, 409, 115567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanini, M.; Heiden, U.; Pace, L.; Casa, R.; Priori, S. Soil Reflectance Composite for Digital Soil Mapping in a Mediterranean Cropland District. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viscarra Rossel, R.A.; Behrens, T.; Ben-Dor, E.; Chabrillat, S.; Alexandre, J.; Demattê, M.; Ge, Y.; Gomez, C.; Guerrero, C.; Peng, Y.; et al. Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy for Estimating Soil Properties: A Technology for the 21st Century. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2022, 73, e13271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, W.; Claupein, W. Approaches Toward Conservation Tillage in Germany. In Conservation Tillage in Temperate Agroecosystems; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; pp. 141–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demattê, J.A.M.; Safanelli, J.L.; Poppiel, R.R.; Rizzo, R.; Silvero, N.E.Q.; de Mendes, W.S.; Bonfatti, B.R.; Dotto, A.C.; Salazar, D.F.U.; Mello, F.A.d.O.; et al. Bare Earth’s Surface Spectra as a Proxy for Soil Resource Monitoring. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayão, V.M.; Demattê, J.A.M.; Bedin, L.G.; Nanni, M.R.; Rizzo, R. Satellite Land Surface Temperature and Reflectance Related with Soil Attributes. Geoderma 2018, 325, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, W.S.; Panachuki, E.; de Oliveira, P.T.S.; da Silva Menezes, R.; Sobrinho, T.A.; de Carvalho, D.F. Effect of Soil Tillage and Vegetal Cover on Soil Water Infiltration. Soil Tillage Res. 2018, 175, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer, T.J.; Horton, R. Soil Heat Flux. In Micrometeorology in Agricultural Systems; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 131–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, R.; Weng, Q.; Alimohammadi, A.; Alavipanah, S.K. Spatial–Temporal Dynamics of Land Surface Temperature in Relation to Fractional Vegetation Cover and Land Use/Cover in the Tabriz Urban Area, Iran. Remote Sens. Environ. 2009, 113, 2606–2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Li, R.; Qiu, R.; Liu, S.; Tan, C.; Li, Q.; Ge, W.; Han, X.; Tang, X.; Shi, W.; et al. Global Land Surface Temperature Influenced by Vegetation Cover and PM2.5 from 2001 to 2016. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulanningtyas, H.S.; Gong, Y.; Li, P.; Sakagami, N.; Nishiwaki, J.; Komatsuzaki, M. A Cover Crop and No-Tillage System for Enhancing Soil Health by Increasing Soil Organic Matter in Soybean Cultivation. Soil Tillage Res. 2021, 205, 104749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Hartemink, A.E. Soil and Environmental Issues in Sandy Soils. Earth Sci. Rev. 2020, 208, 103295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saffigna, P.G.; Keeney, D.R.; Tanner, C.B. Nitrogen, Chloride, and Water Balance with Irrigated Russet Burbank Potatoes in a Sandy Soil. Agron. J. 1977, 69, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, A.; Dines, L. Lockhart and Wiseman’s Crop Husbandry Including Grassland; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2022; pp. 1–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catt, J.A. The Agricultural Importance of Loess. Earth Sci. Rev. 2001, 54, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Chen, L.; Fu, B.; Huang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Peng, H. Effect of Land Use on Soil Nutrients in the Loess Hilly Area of the Loess Plateau, China. Land Degrad. Dev. 2006, 17, 453–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotroczó, Z.; Fekete, I.; Juhos, K.; Prettl, N.; Nugroho, P.A.; Várbíró, G.; Biró, B.; Kocsis, T. Characterisation of Luvisols Based on Wide-Scale Biological Properties in a Long-Term Organic Matter Experiment. Biology 2023, 12, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, R.; Mordhorst, A.; Fleige, H. The Impact of Arable Soil Management on Physical Functions—The Ratio of Air Capacity and Air Permeability or Hydraulic Conductivity as a Document of Harmful Soil Compaction. Soil Tillage Res. 2024, 244, 106221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartemink, A.E. Soil Fertility Decline in Some Major Soil Groupings under Permanent Cropping in Tanga Region, Tanzania. Geoderma 1997, 75, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minasny, B.; McBratney, A.B.; Salvador-Blanes, S. Quantitative Models for Pedogenesis—A Review. Geoderma 2008, 144, 140–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Du, J.; Zhong, S.; Ci, E.; Wei, C. Changes in the Profile Properties and Chemical Weathering Characteristics of Cultivated Soils Affected by Anthropic Activities. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Soil management in the developing countries. Soil Sci. 2000, 165, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirui, O.K. Economics of Land Degradation and Improvement in Tanzania and Malawi. In Economics of Land Degradation and Improvement—A Global Assessment for Sustainable Development; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 609–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkonya, E.; Mirzabaev, A.; von Braun, J. Economics of Land Degradation and Improvement—A Global Assessment for Sustainable Development; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayaki, I.; Mathai, W. We Need a Moonshot for Africa’s Land Restoration Movement. 2021. Available online: https://www.wri.org/update/we-need-moonshot-africas-land-restoration-movement (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Hüttl, R.F.; Frielinghaus, M. Soil Fertility Problems—An Agriculture and Forestry Perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 1994, 143, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeger, M. Agricultural Soil Degradation in Germany. In Impact of Agriculture on Soil Degradation II: A European Perspective; Spinger: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruckmeier, K.; Grund, H. Agricultural Restructuring and Rural Chance in Europe; Symes, D., Jansenm, A., Eds.; Agricultural University: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann, V.; Hagedorn, K. De-Collectivisation Policies and Structural Changes of Agriculture in Eastern Germany. MOST Econ. Policy Transitional Econ. 1995, 5, 133–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagos, P.; Jones, A.; Lugato, E.; Ballabio, C. A Soil Monitoring Law for Europe. Glob. Chall. 2025, 9, 2400336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broothaerts, N.; Panagos, P.; Jones, A. A Proposal for Soil Health Indicators at EU-Level. 2024. Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC138417 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Campbell, G.A.; Smith, P.; Broothaerts, N.; Panagos, P.; Jones, A.; Cristiano Ballabio, I.; De Rosa, D.; Lis, I.; De Jonge, W.; Arthur, E.; et al. European Journal of Soil Science Continental Scale Soil Monitoring: A Proposed Multi-Scale Framing of Soil Quality. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2025, 76, 70174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matson, A.; Fantappiè, M.; Campbell, G.A.; Miranda-Vélez, J.F.; Faber, J.H.; Carvalho Gomes, L.; Hessel, R.; Lana, M.; Mocali, S.; Smith, P.; et al. A Framework for Setting Soil Health Targets and Thresholds in Agricultural Soils. Available online: https://projects.au.dk/fileadmin/projects/ejpsoil/WP8/Policy_briefs/EJPSOIL_Policy_Brief_Targets_and_Thresholds.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Romero, F.; Labouyrie, M.; Orgiazzi, A.; Ballabio, C.; Panagos, P.; Jones, A.; Tedersoo, L.; Bahram, M.; Guerra, C.A.; Eisenhauer, N.; et al. Soil Health Is Linked to Primary Productivity across Europe. bioRxiv 2023. bioRxiv:2023.10.29.564603. [Google Scholar]

- Säurich, A.; Möller, M.; Gerighausen, H. A Novel Remote Sensing-Based Approach to Determine Loss of Agricultural Soils Due to Soil Sealing—A Case Study in Germany. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannam, J.A.; Harris, M.; Deeks, L.; Hoskins, H.; Hutchison, J.; Withers, A.J.; Harris, J.A.; Way, L.; Rickson, R.J.R. Developing a Multifunctional Indicator Framework for Soil Health. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 175, 113515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Verhoef, A.; Vereecken, H.; Ben-Dor, E.; Veldkamp, T.; Shaw, L.; Wang, Y.; Bob Su, Z. Tracking Soil Health: Monitoring and Modeling the Soil-Plant System. 2024. Available online: https://essopenarchive.org/doi/full/10.22541/essoar.171804479.91646868 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Campbell, G.; Robinson, D.; Smith, P.; Wollesen de Jonge, L.; Nørgaard, T. Developing a Robust Soil Health Indicator Selection Framework. Open Access Gov. 2024, 43, 378–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoud, A. Unifying Studies of Scarcity, Abundance, and Sufficiency. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 147, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, T.; Wenner, F. Land Policy in Germany: Waiting for the Owner to Develop. In Land Policies in Europe: Land-Use Planning, Property Rights, and Spatial Development; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, B.; Klauer, B.; Schiller, J. Prospects for Sustainable Land-Use Policy in Germany: Experimenting with a Sustainability Heuristic. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 95, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Zhang, X.; Huang, Y.; Chen, S.; Dai, L.; Chen, X.; Yu, Q.; Ye, S.; Shi, Z. A Two-Dimensional Bare Soil Separation Framework Using Multi-Temporal Sentinel-2 Images across China. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2024, 134, 104181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, A.L. Strengths and Weaknesses of Common Sustainability Indices for Multidimensional Systems. Environ. Int. 2008, 34, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballabio, C.; Lugato, E.; Fernández-Ugalde, O.; Orgiazzi, A.; Jones, A.; Borrelli, P.; Montanarella, L.; Panagos, P. Mapping LUCAS Topsoil Chemical Properties at European Scale Using Gaussian Process Regression. Geoderma 2019, 355, 113912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reidsma, P.; Janssen, S.; Jansen, J.; van Ittersum, M.K. On the Development and Use of Farm Models for Policy Impact Assessment in the European Union—A Review. Agric. Syst. 2018, 159, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orgiazzi, A.; Ballabio, C.; Panagos, P.; Jones, A.; Fernández-Ugalde, O. LUCAS Soil, the Largest Expandable Soil Dataset for Europe: A Review. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2018, 69, 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagos, P.; Van Liedekerke, M.; Borrelli, P.; Köninger, J.; Ballabio, C.; Orgiazzi, A.; Lugato, E.; Liakos, L.; Hervas, J.; Jones, A.; et al. European Soil Data Centre 2.0: Soil Data and Knowledge in Support of the EU Policies. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2022, 73, e13315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viscarra Rossel, R.A.; Adamchuk, V.I.; Sudduth, K.A.; McKenzie, N.J.; Lobsey, C. Proximal Soil Sensing. An Effective Approach for Soil Measurements in Space and Time. Adv. Agron. 2011, 113, 237–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrends, H.E.; Simojoki, A.; Lajunen, A. Spatial Pattern Consistency and Repeatability of Proximal Soil Sensor Data for Digital Soil Mapping. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2023, 74, e13409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Soil Attribute | Original Soil Observations | BSO (100 km) | ANSO (3.3 × 106 ha) | AGSO (2 × 107 ha) | FSO (1.1 × 107 ha) | Filtered Soil Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physicals | ||||||

| Bulk Density (BD) | 404 | 201 | 2 | 141 | 60 | 389 |

| Clay | 2638 | 715 | 37 | 1508 | 378 | 2537 |

| Biologicals | ||||||

| Soil Organic Carbon (SOC) | 2836 | 715 | 39 | 1704 | 378 | 2595 |

| Chemicals | ||||||

| Potassium (K) | 2604 | 715 | 37 | 1478 | 378 | 2370 |

| Nitrogen (N) | 2608 | 715 | 37 | 1478 | 378 | 2394 |

| Cation-exchange Capacity (CEC) | 2608 | 715 | 37 | 1478 | 378 | 2458 |

| Phosphorus (P) | 2608 | 711 | 37 | 1478 | 378 | 2428 |

| pH | 2608 | 715 | 37 | 1478 | 378 | 2507 |

| Factors | EC | Unit | Source (Spatial Resolution) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climatic | AMT | °C | WorldClim BIO Variables V1 (90 m) | [30] |

| TAR | °C | WorldClim BIO Variables V7 (90 m) | [30] | |

| AP | mm | WorldClim BIO Variables V12 (90 m) | [30] | |

| PS | mm | WorldClim BIO Variables V15 (90 m) | [30] | |

| Relief | Elevation | Meter | SRTM (90 m) | [31] |

| Slope | Degree | TAGEE/SRTM (90 m) | [31] | |

| Aspect | Degree | TAGEE/SRTM (90 m) | [31] | |

| Hillshade | Dimensionless | TAGEE/SRTM (90 m) | [31] | |

| Northness | Dimensionless | TAGEE/SRTM (90 m) | [31] | |

| Eastness | Dimensionless | TAGEE/SRTM (90 m) | [31] | |

| Horizontal Curvature | Meter | TAGEE/SRTM (90 m) | [31] | |

| Vertical Curvature | Meter | TAGEE/SRTM (90 m) | [31] | |

| Mean Curvature | Meter | TAGEE/SRTM (90 m) | [31] | |

| Gaussian Curvature | Meter | TAGEE/SRTM (90 m) | [31] | |

| Minimal Curvature | Meter | TAGEE/SRTM (90 m) | [31] | |

| Maximal Curvature | Meter | TAGEE/SRTM (90 m) | [31] | |

| Shape Index | Dimensionless | TAGEE/SRTM (90 m) | [31] | |

| MultiScale Topographic Position Index | Meter | TAGEE/SRTM (90 m) | [31] | |

| Euclidean Distance to Water | TAGEE/SRTM (90 m) | [31] | ||

| Soil + Vegetation | SYSI Blue (450–520 nm) | - | Landsat collection (90 m) | [32] |

| SYSI Green (520–600 nm) | - | Landsat collection (90 m) | [32] | |

| SYSI Red (630–690 nm) | - | Landsat collection (90 m) | [32] | |

| SYSI NIR (760–900 nm) | - | Landsat collection (90 m) | [32] | |

| SYSI SWIR1 (1550–1750 nm) | - | Landsat collection (90 m) | [32] | |

| SYSI SWIR2 (2080–2350 nm) | - | Landsat collection (90 m) | [32] | |

| mBlue (450–520 nm) | - | Landsat collection (90 m) | In this study | |

| mGreen (520–600 nm) | - | Landsat collection (90 m) | In this study | |

| mRed (630–690 nm) | - | Landsat collection (90 m) | In this study | |

| mNIR (760–900 nm) | - | Landsat collection (90 m) | In this study | |

| mSWIR1 (1550–1750 nm) | - | Landsat collection (90 m) | In this study | |

| mSWIR2 (2080–2350 nm) | - | Landsat collection (90 m) | In this study | |

| Soil activity | Mode Land Use and Coverage | - | Sentinel & Landsat collections (90 m) | [28] |

| Vegetation | EVI | - | Landsat collection (90 m) | In this study |

| SAVI | - | Landsat collection (90 m) | In this study | |

| Land Surface Temperature (LST) | LST | Kelvin | Landsat collection (90 m) | [33] |

| Index | Soil Function | Weight | Sub-Functions | Weight | Indicators | Scoring Function | Scoring-Curve Shape | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Level | Weight | |||||||

| SHI | f(i) | 0.34 | f(i.i) | 0.4 | P | 0.33 | MBI |  |

| K | 0.33 | MBI |  | |||||

| N | 0.33 | MBI |  | |||||

| f(i.ii) | 0.4 | pH | 1 | OMI |  | |||

| f(i.iii) | 0.2 | CEC | 1 | MBI |  | |||

| f(ii) | 0.33 | SOC | 0.5 | MBI |  | |||

| Earthworms | 0.5 | MBI |  | |||||

| f(iii) | 0.33 | Bulk Density | 1 | LBI |  | |||

| ESDAC Product | Description | Bands |

|---|---|---|

| European Soil Degradation Indicators | [46] | Bands 1–12 |

| Multiband Soil Degradation Indicators | [47] | Bands 1–20 |

| State * | MnF | EnF | EcF | SADI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rheinland-Pfalz | 0.93 | 0.43 | 1.00 | 0.66 |

| Nordrhein-Westfalen | 0.92 | 0.44 | 0.86 | 0.65 |

| Bayern | 0.91 | 0.46 | 0.81 | 0.64 |

| Baden-Württemberg | 0.93 | 0.47 | 0.68 | 0.62 |

| Niedersachsen | 0.94 | 0.39 | 0.66 | 0.59 |

| Saarland | 0.97 | 0.51 | 0.13 | 0.56 |

| Schleswig-Holstein | 0.94 | 0.41 | 0.34 | 0.55 |

| Hessen | 0.92 | 0.44 | 0.32 | 0.53 |

| Sachsen | 0.85 | 0.40 | 0.12 | 0.47 |

| Thüringen | 0.84 | 0.39 | 0.07 | 0.46 |

| Mecklenburg-Vorpommern | 0.85 | 0.35 | 0.03 | 0.43 |

| Brandenburg | 0.86 | 0.32 | 0.00 | 0.41 |

| Sachsen-Anhalt | 0.83 | 0.30 | 0.04 | 0.40 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

de Sousa, G.P.B.; Demattê, J.A.M.; Chabrillat, S.; Milewski, R.; Poppiel, R.R.; Amorim, M.T.A.; Bartsch, B.d.A.; Rosas, J.T.F.; Cherubin, M.R.; Ma, Y.; et al. A Sustainable Agricultural Development Index (SADI): Bridging Soil Health, Management, and Socioeconomic Factors. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 4039. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244039

de Sousa GPB, Demattê JAM, Chabrillat S, Milewski R, Poppiel RR, Amorim MTA, Bartsch BdA, Rosas JTF, Cherubin MR, Ma Y, et al. A Sustainable Agricultural Development Index (SADI): Bridging Soil Health, Management, and Socioeconomic Factors. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):4039. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244039

Chicago/Turabian Stylede Sousa, Gabriel Pimenta Barbosa, José Alexandre Melo Demattê, Sabine Chabrillat, Robert Milewski, Raul Roberto Poppiel, Merilyn Taynara Accorsi Amorim, Bruno dos Anjos Bartsch, Jorge Tadeu Fim Rosas, Maurício Roberto Cherubin, Yuxin Ma, and et al. 2025. "A Sustainable Agricultural Development Index (SADI): Bridging Soil Health, Management, and Socioeconomic Factors" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 4039. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244039

APA Stylede Sousa, G. P. B., Demattê, J. A. M., Chabrillat, S., Milewski, R., Poppiel, R. R., Amorim, M. T. A., Bartsch, B. d. A., Rosas, J. T. F., Cherubin, M. R., Ma, Y., Oliveira, R. B. d., Nanni, M. R., & Falcioni, R. (2025). A Sustainable Agricultural Development Index (SADI): Bridging Soil Health, Management, and Socioeconomic Factors. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 4039. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244039