Insights into Seagrass Distribution, Persistence, and Resilience from Decades of Satellite Monitoring

Highlights

- Seagrass persistence varies by species and in space and is, generally, low.

- Seagrass diversity and extent on the Eastern Banks has declined.

- Time-series analysis reveals a broad ecosystem shift in dominant species.

- We present a repeatable, machine learning- and cloud-processing-based mapping workflow.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

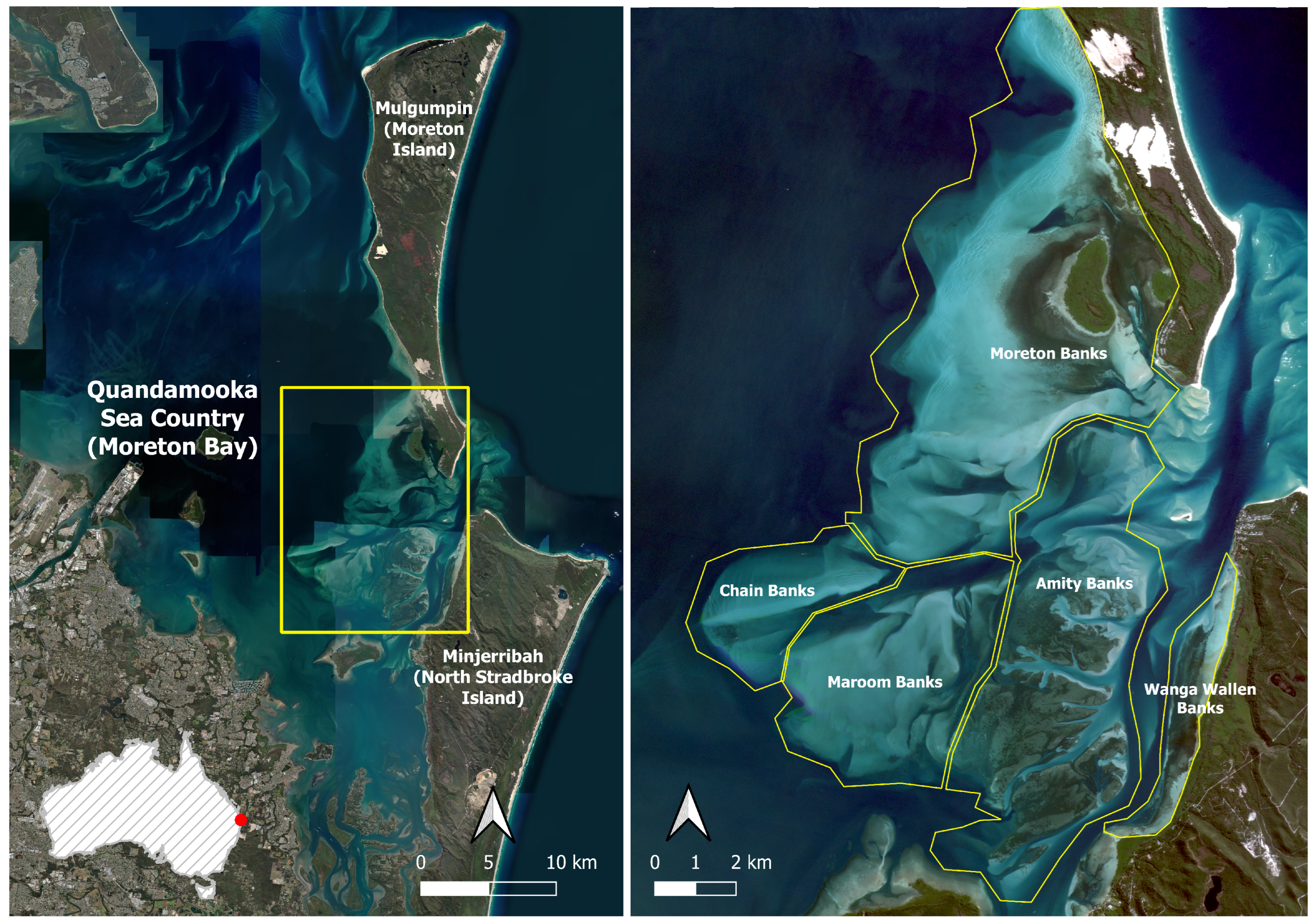

2.1. Study Area

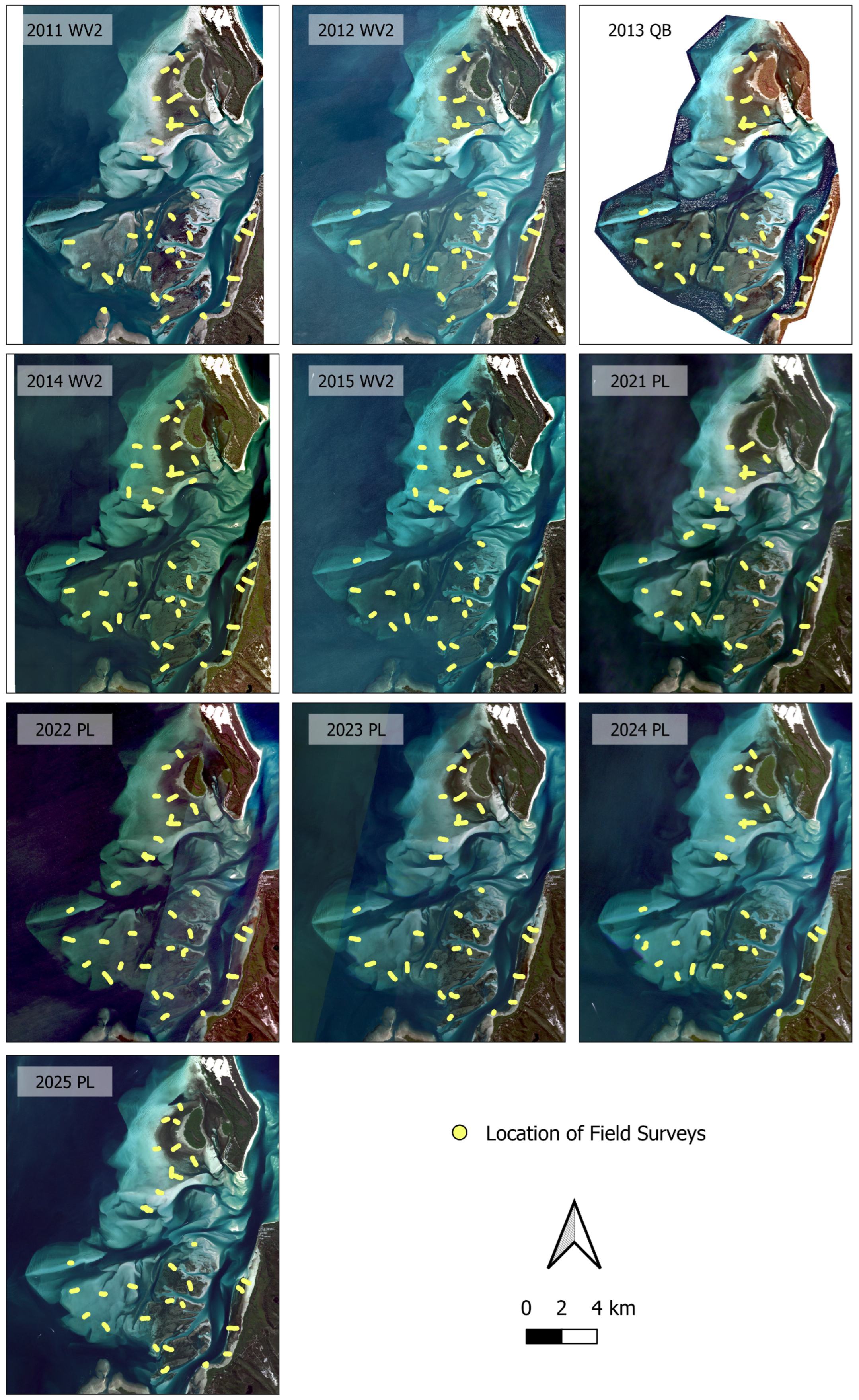

2.2. Datasets

2.2.1. Field Data Collection and Pre-Processing

2.2.2. Satellite Imagery Collection and Pre-Processing

2.2.3. Physical Attributes

2.3. Seagrass Species Composition and Abundance Mapping and Accuracy Assessment

2.4. Trend Analysis

2.5. Per-Pixel Analysis

3. Results

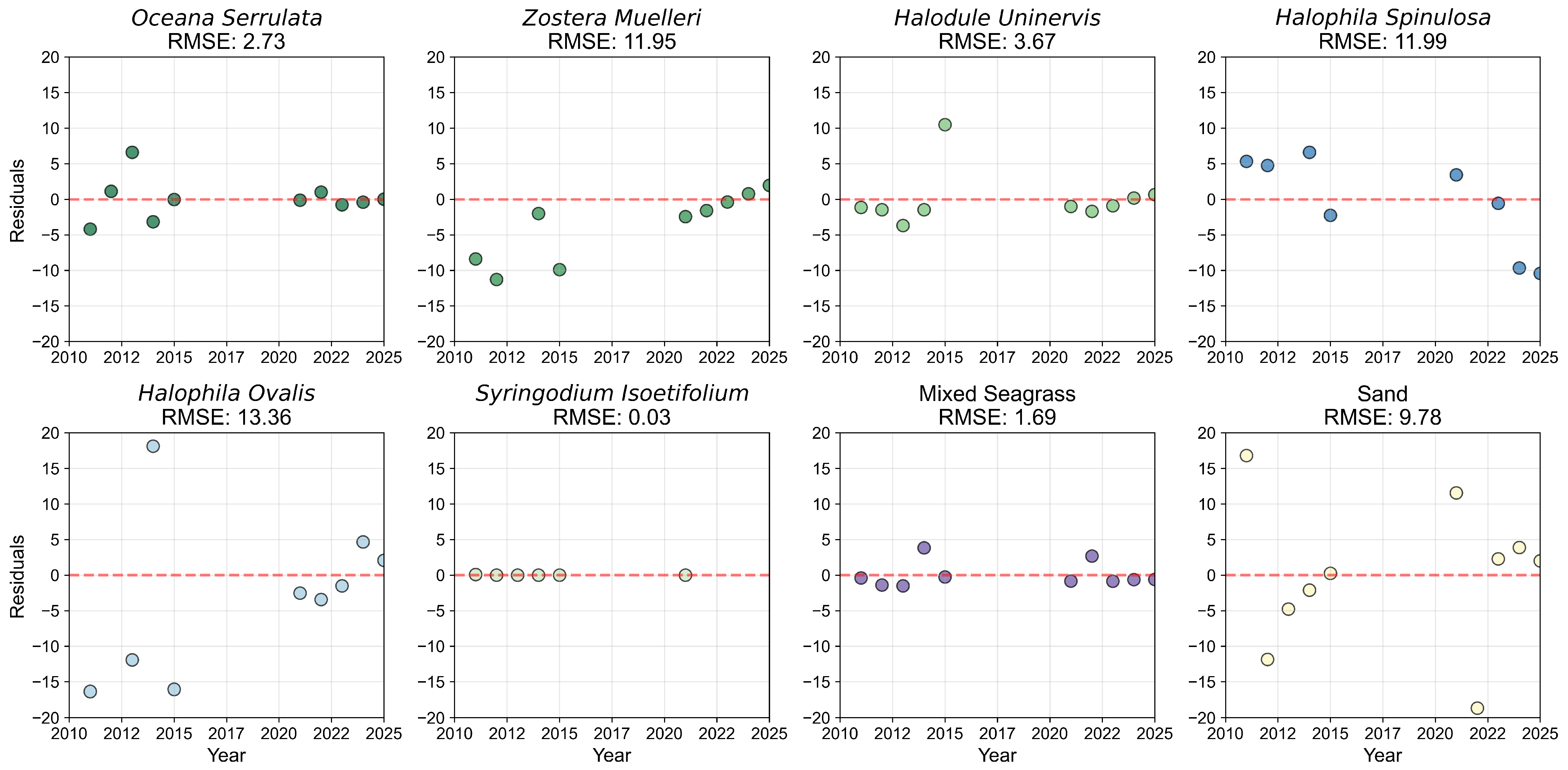

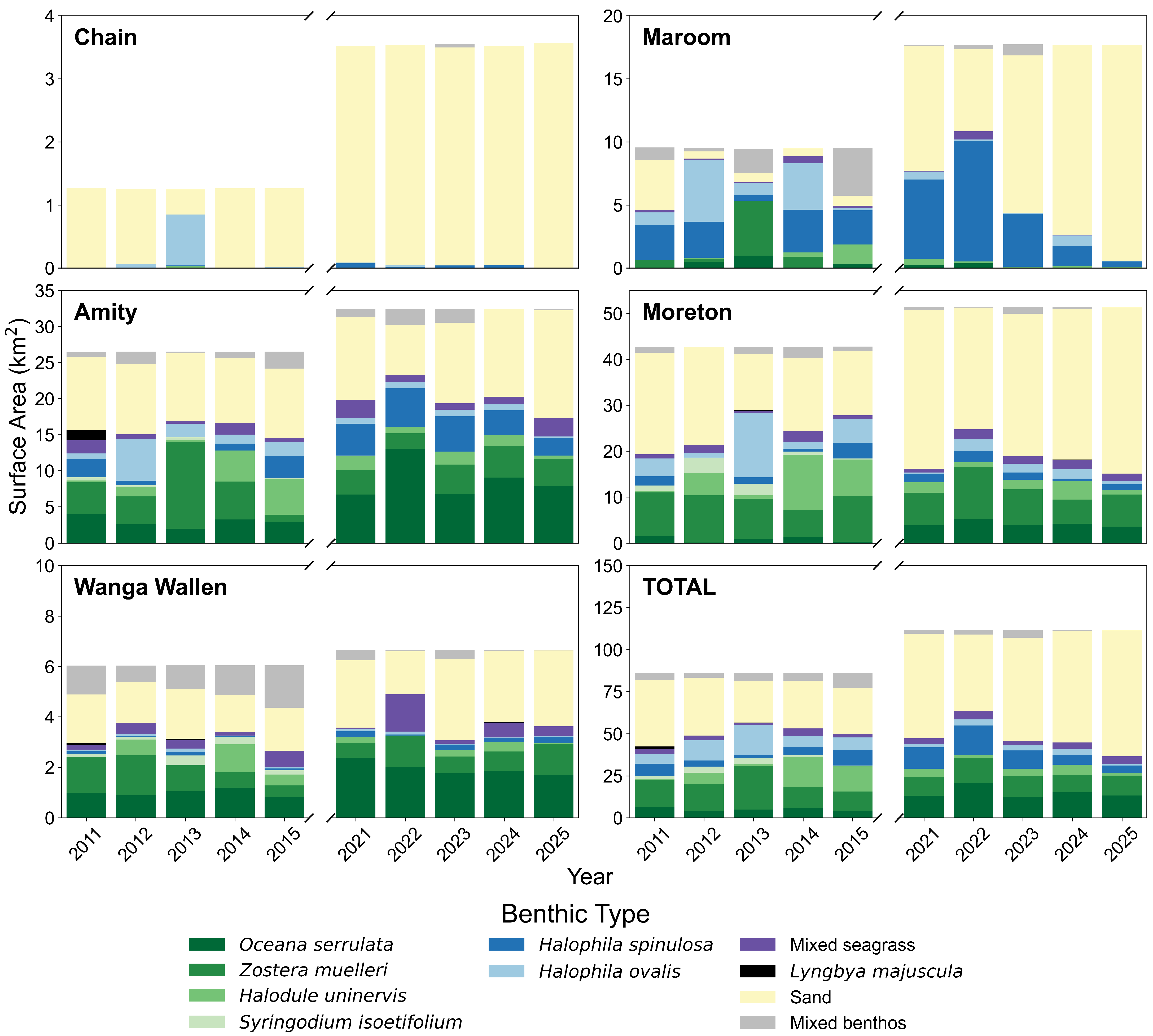

3.1. Seagrass Species Composition

3.1.1. Species Mapping and Accuracy

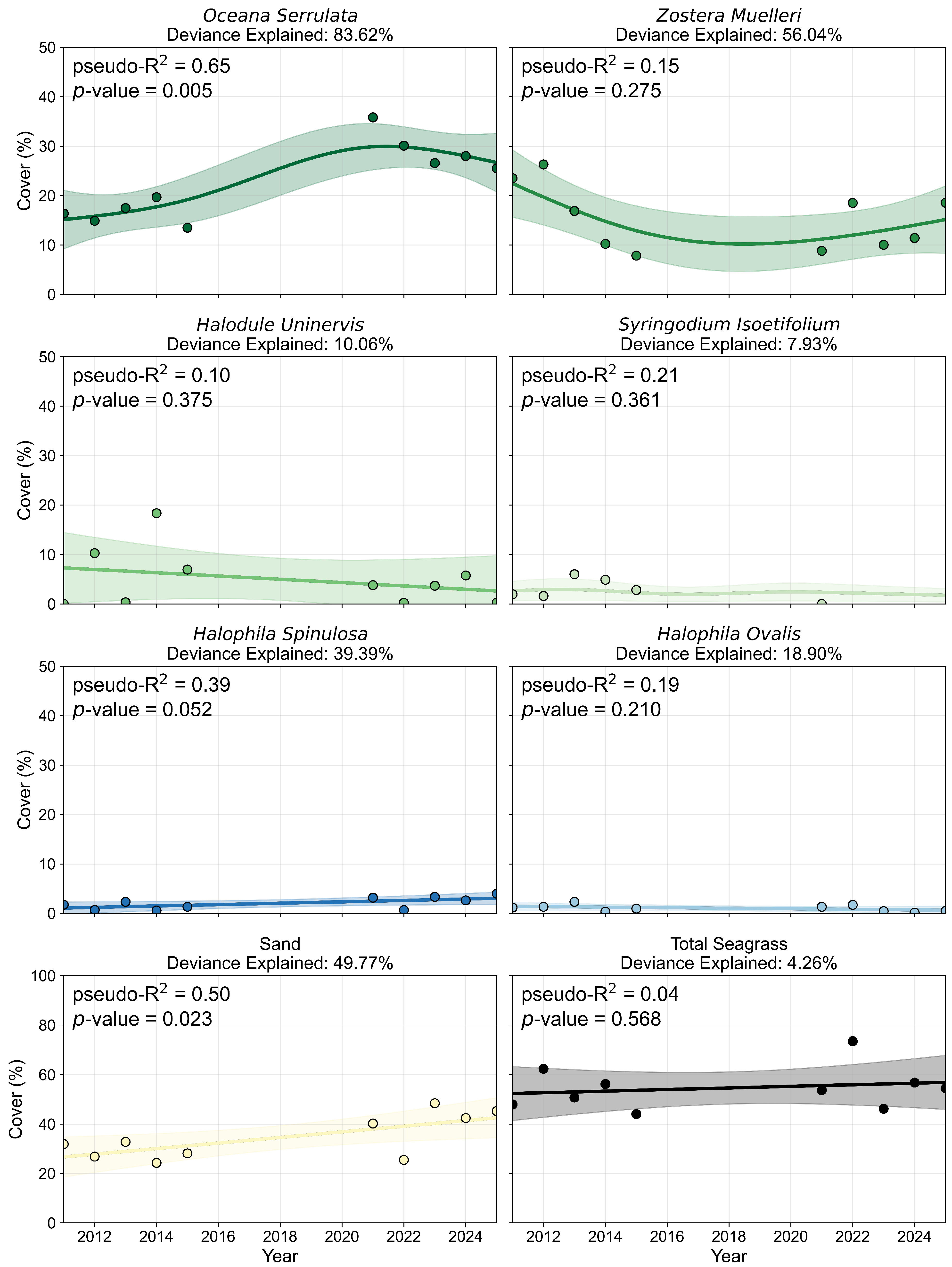

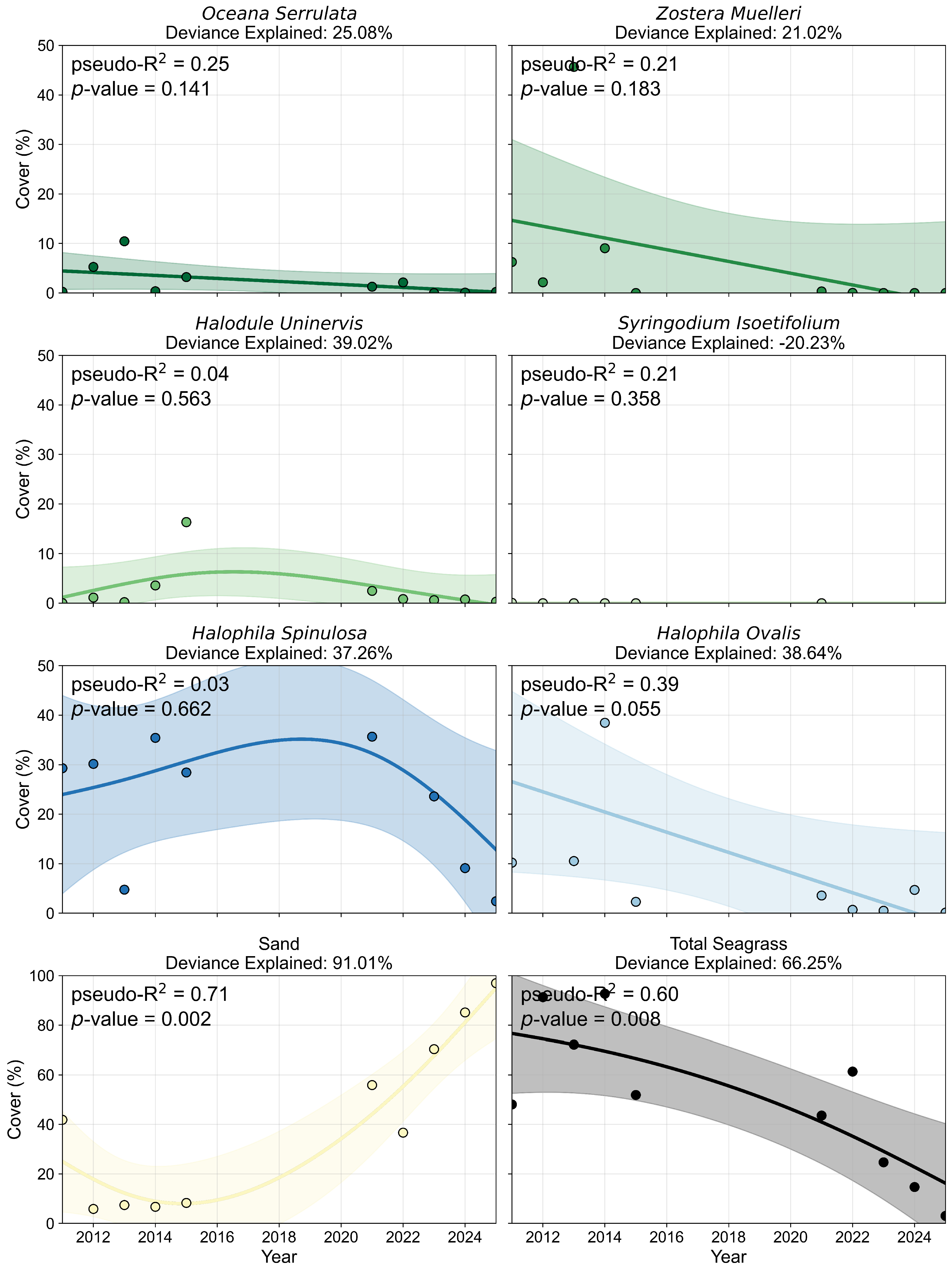

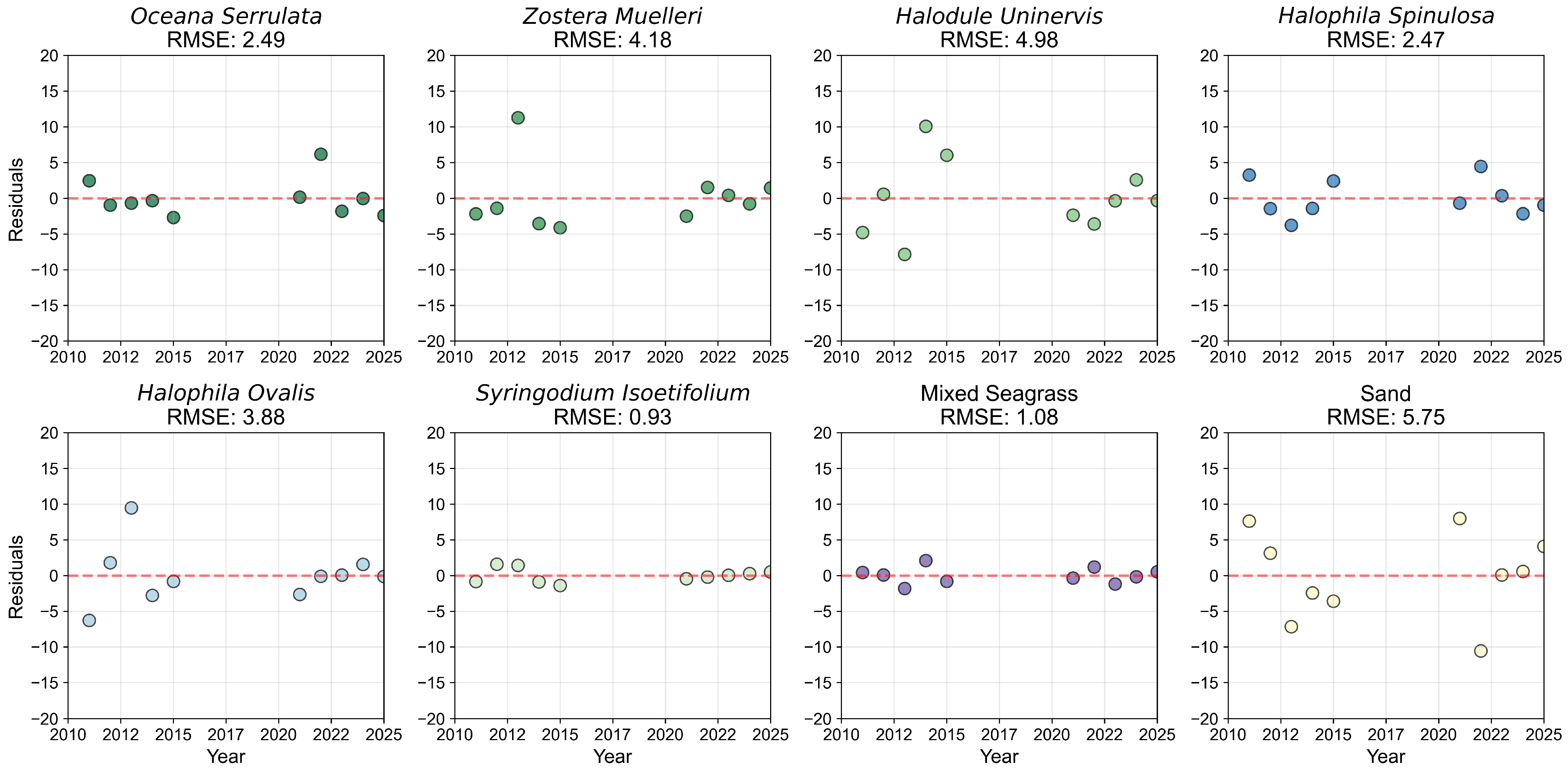

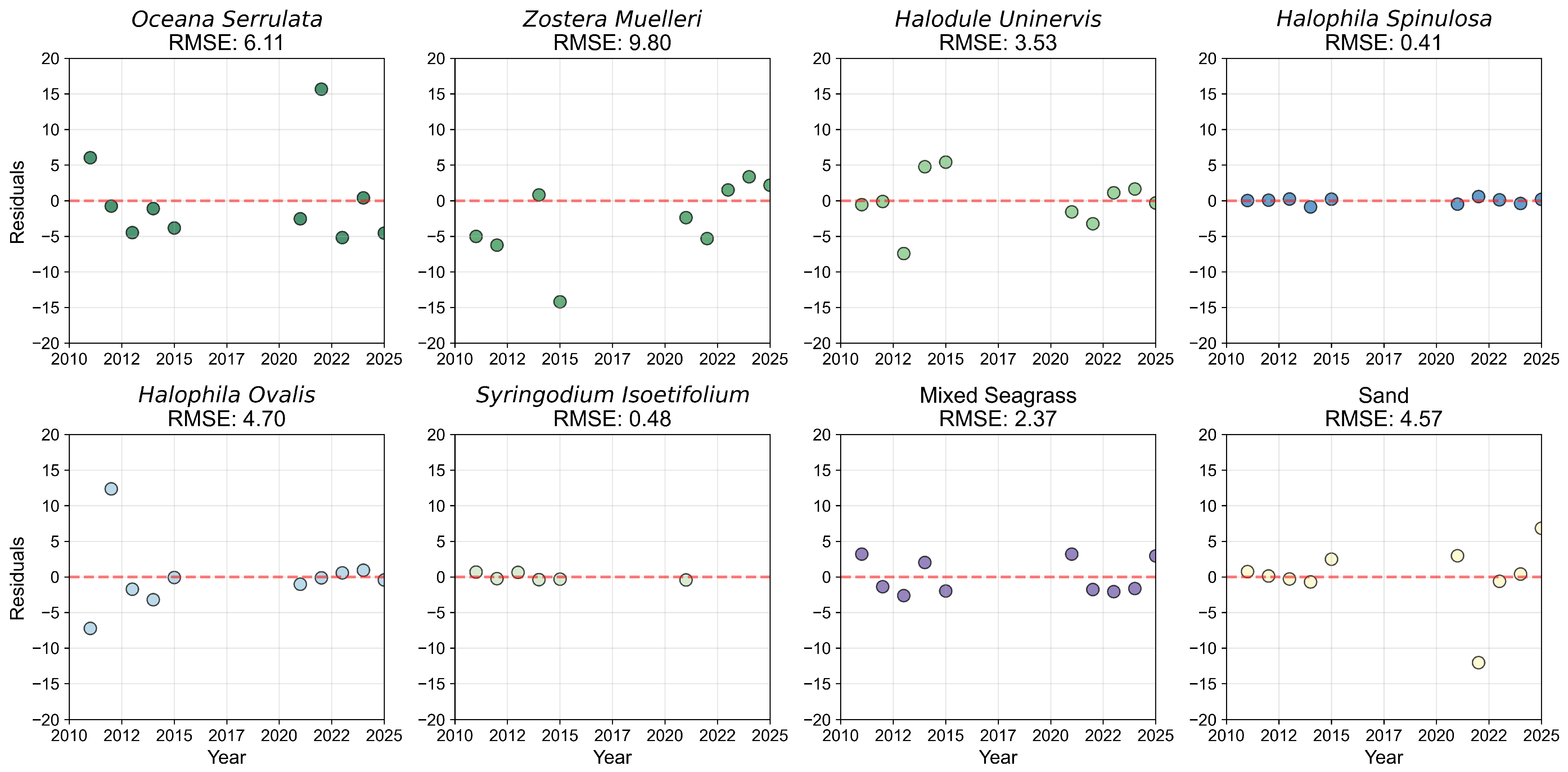

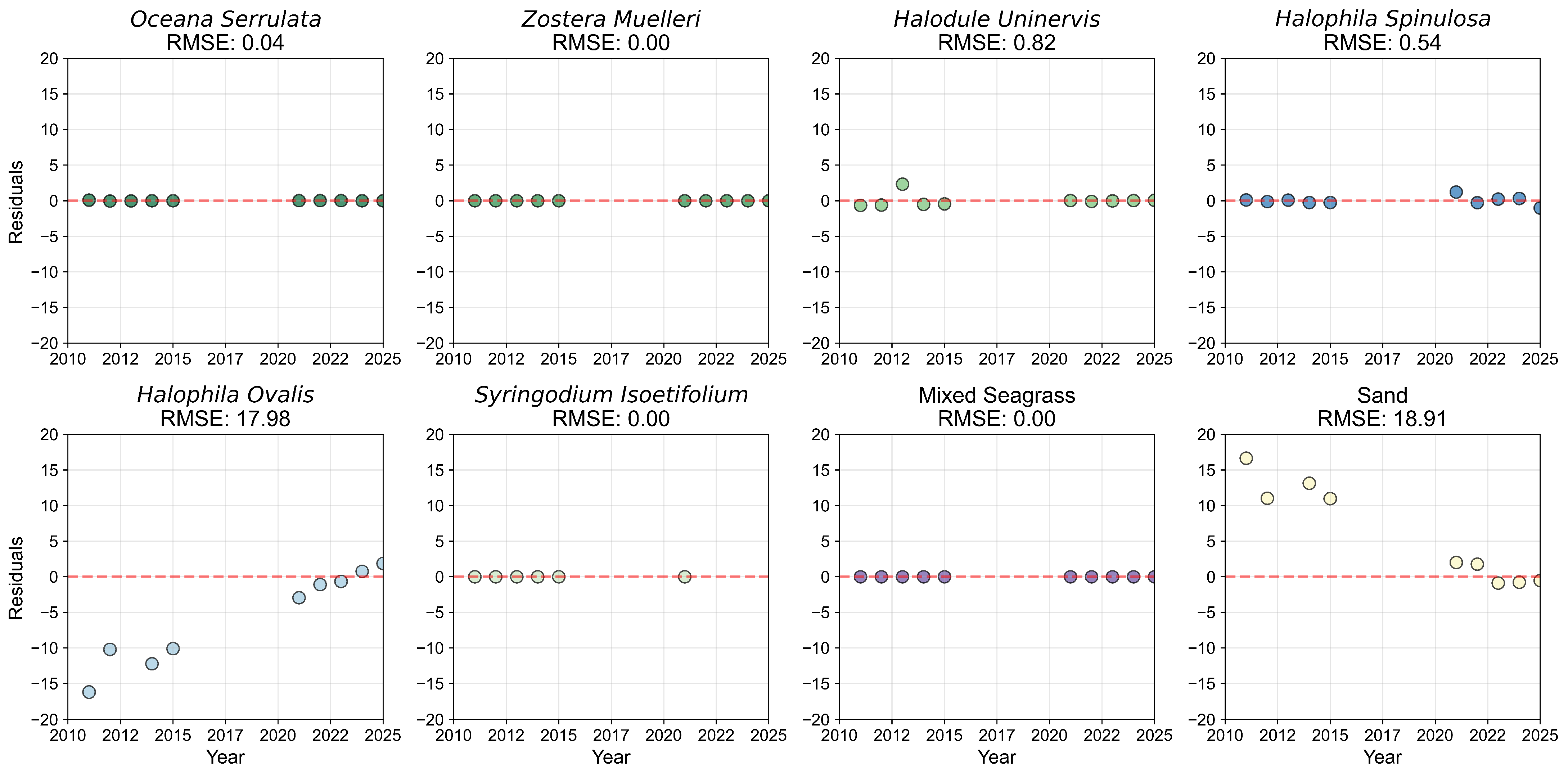

3.1.2. Species Composition and Pixel Distribution Trends

| Year | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species Cover Accuracy (%) | 74 | 71 | 74 | 72 | 69 | 78 | 73 | 72 | 71 | 77 | 73 |

| Percent Cover Accuracy (%) | 58 | 64 | 60 | 62 | 60 | 55 | 58 | 60 | 56 | 61 | 59 |

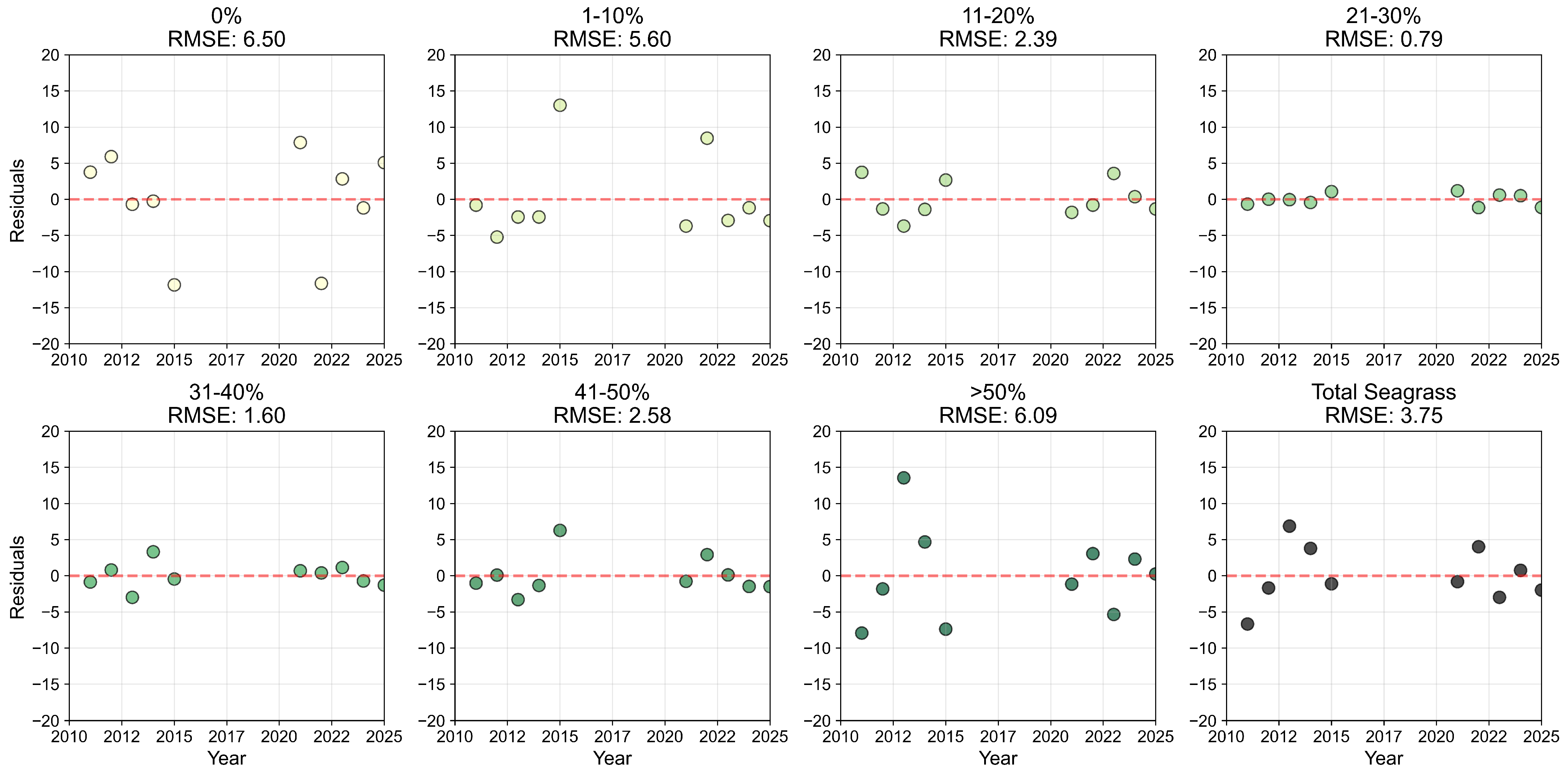

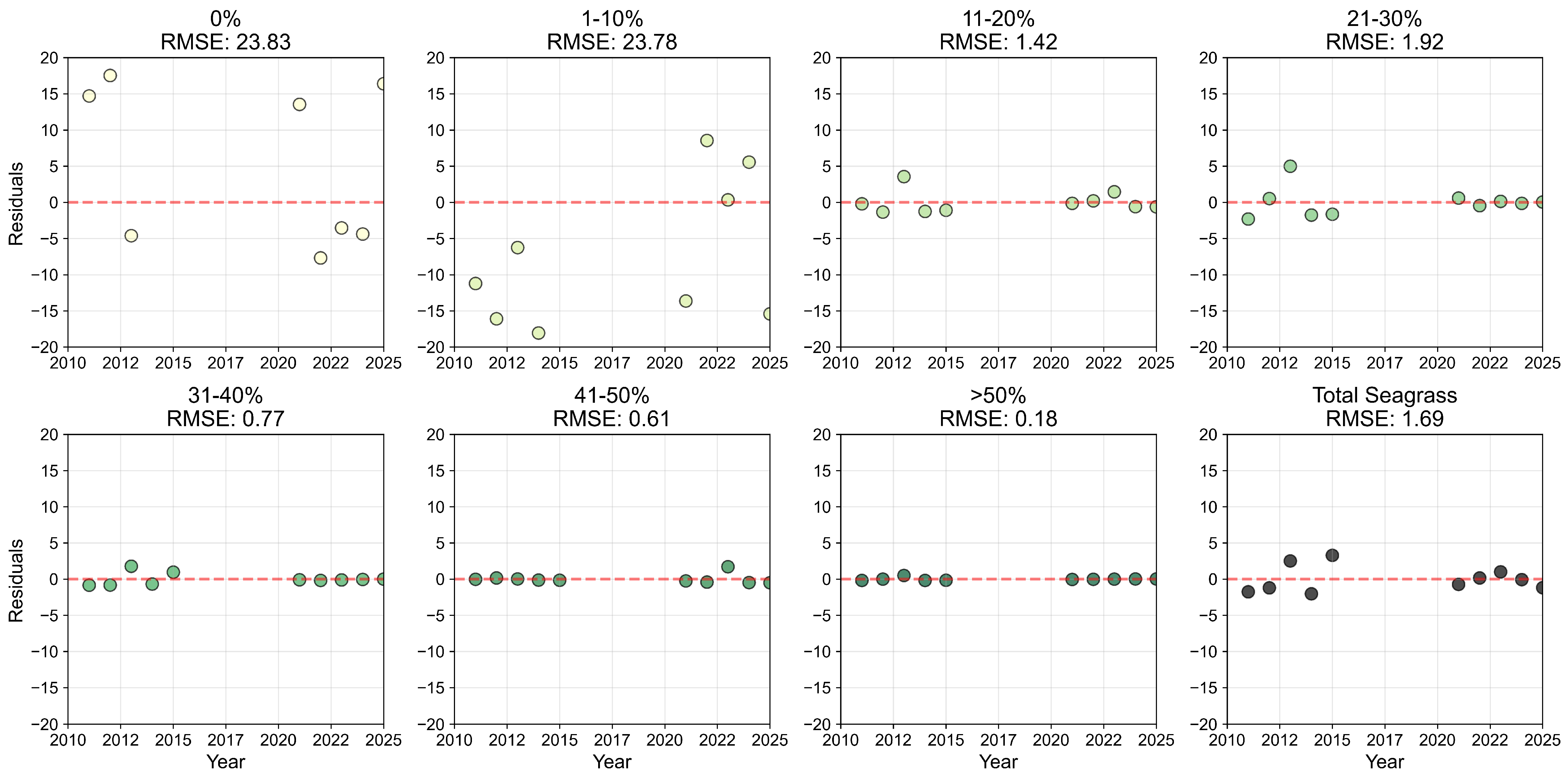

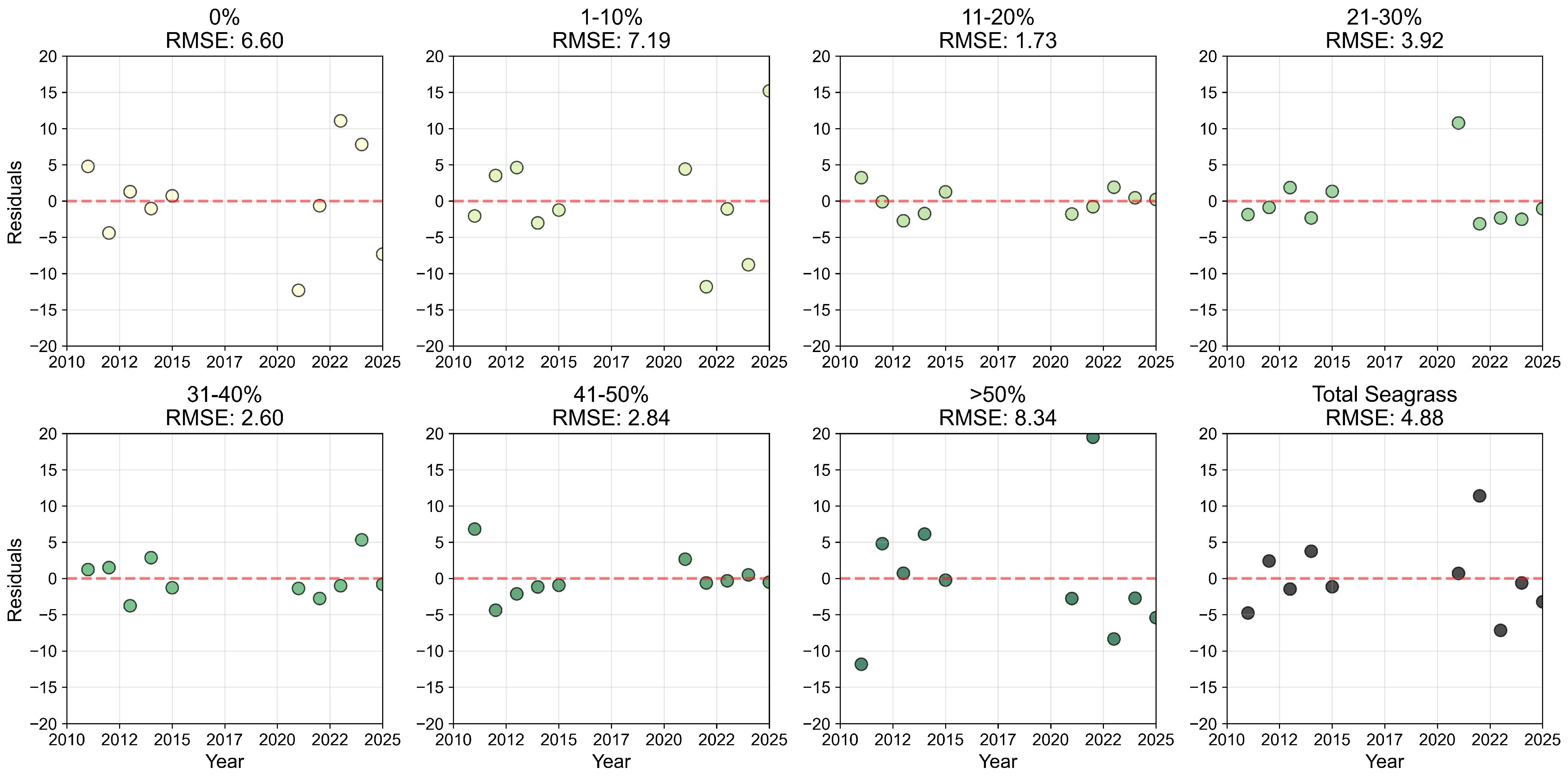

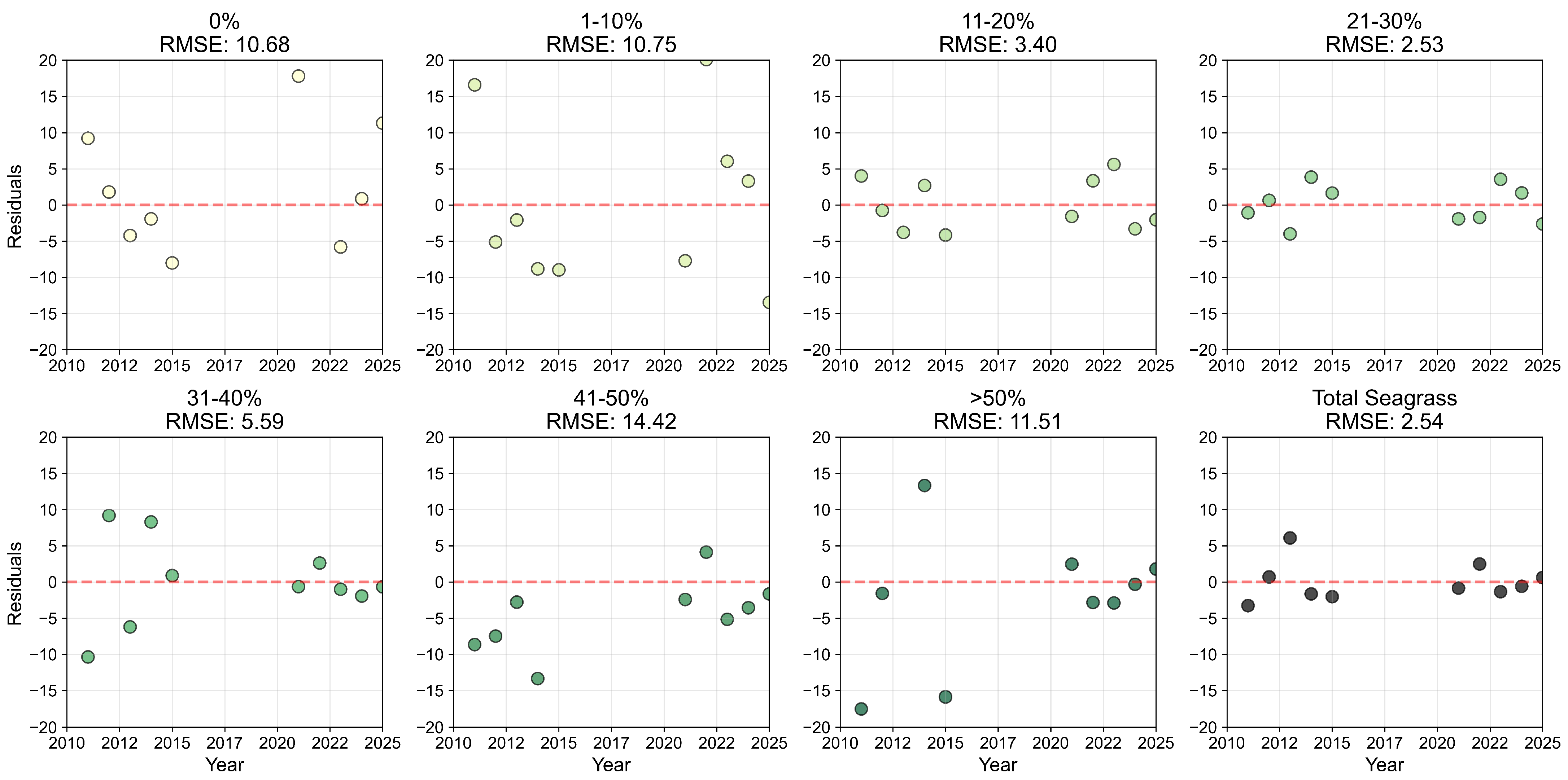

3.2. Seagrass Percent Cover

3.2.1. Percent Cover Mapping and Accuracy

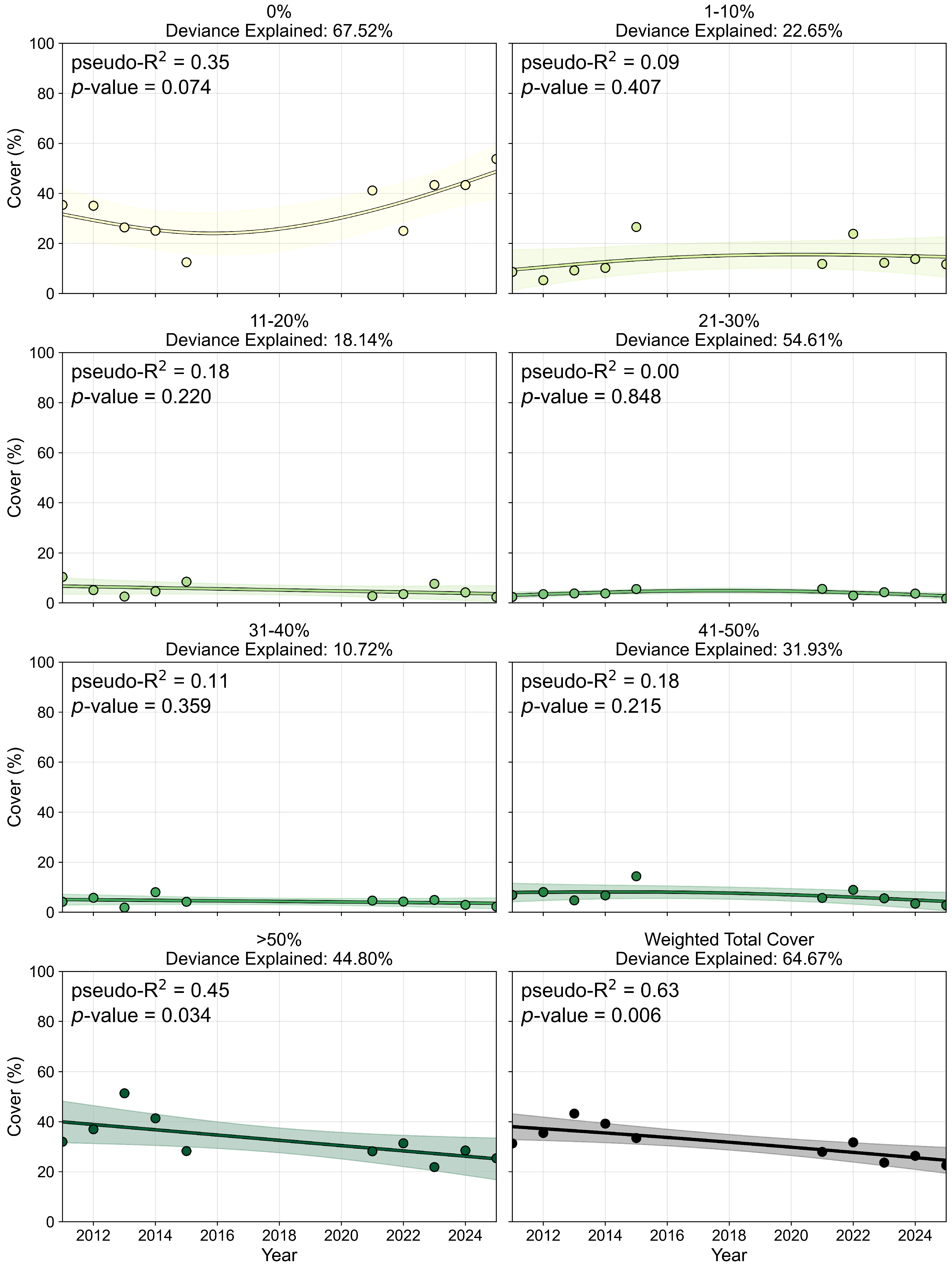

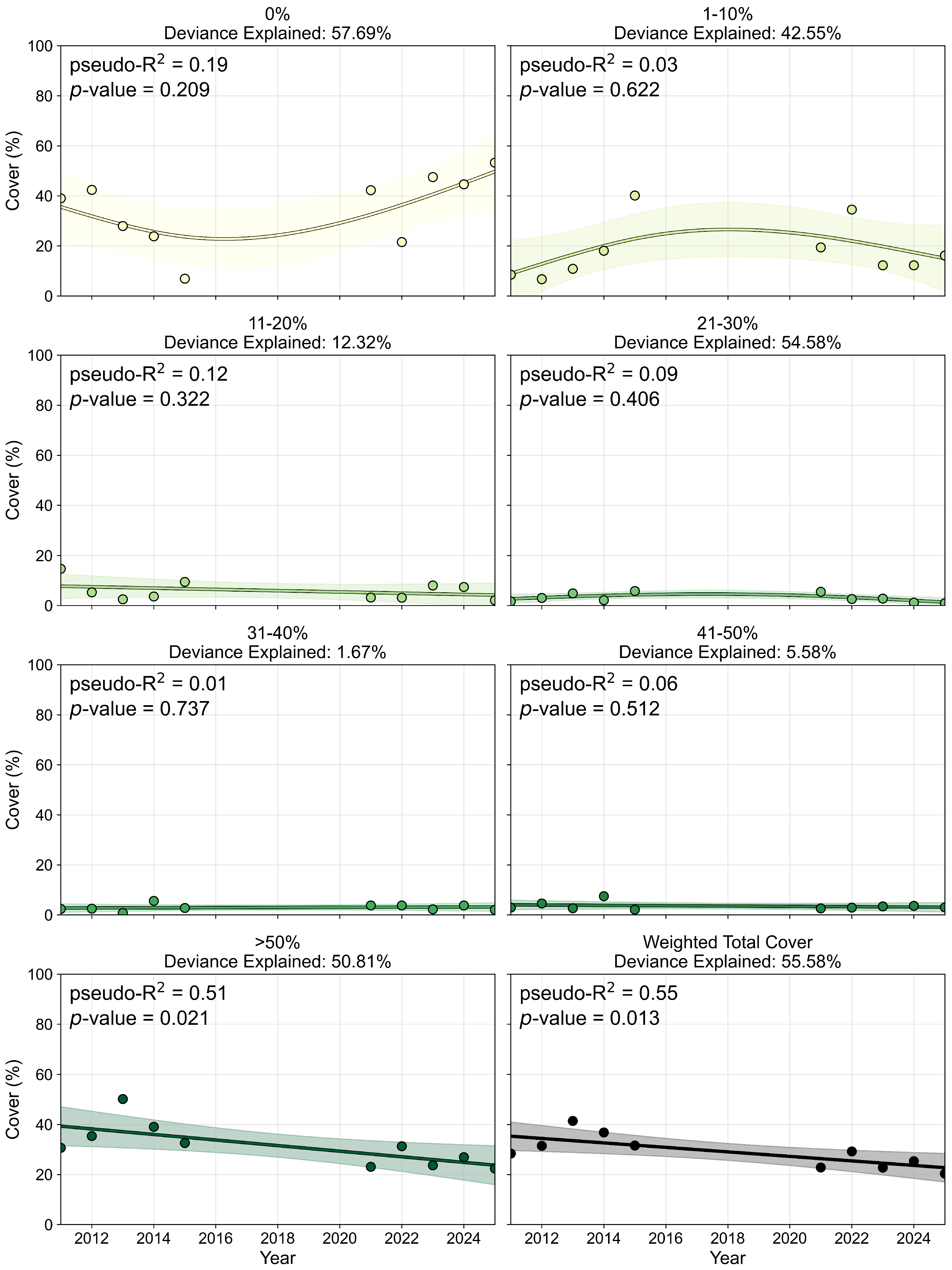

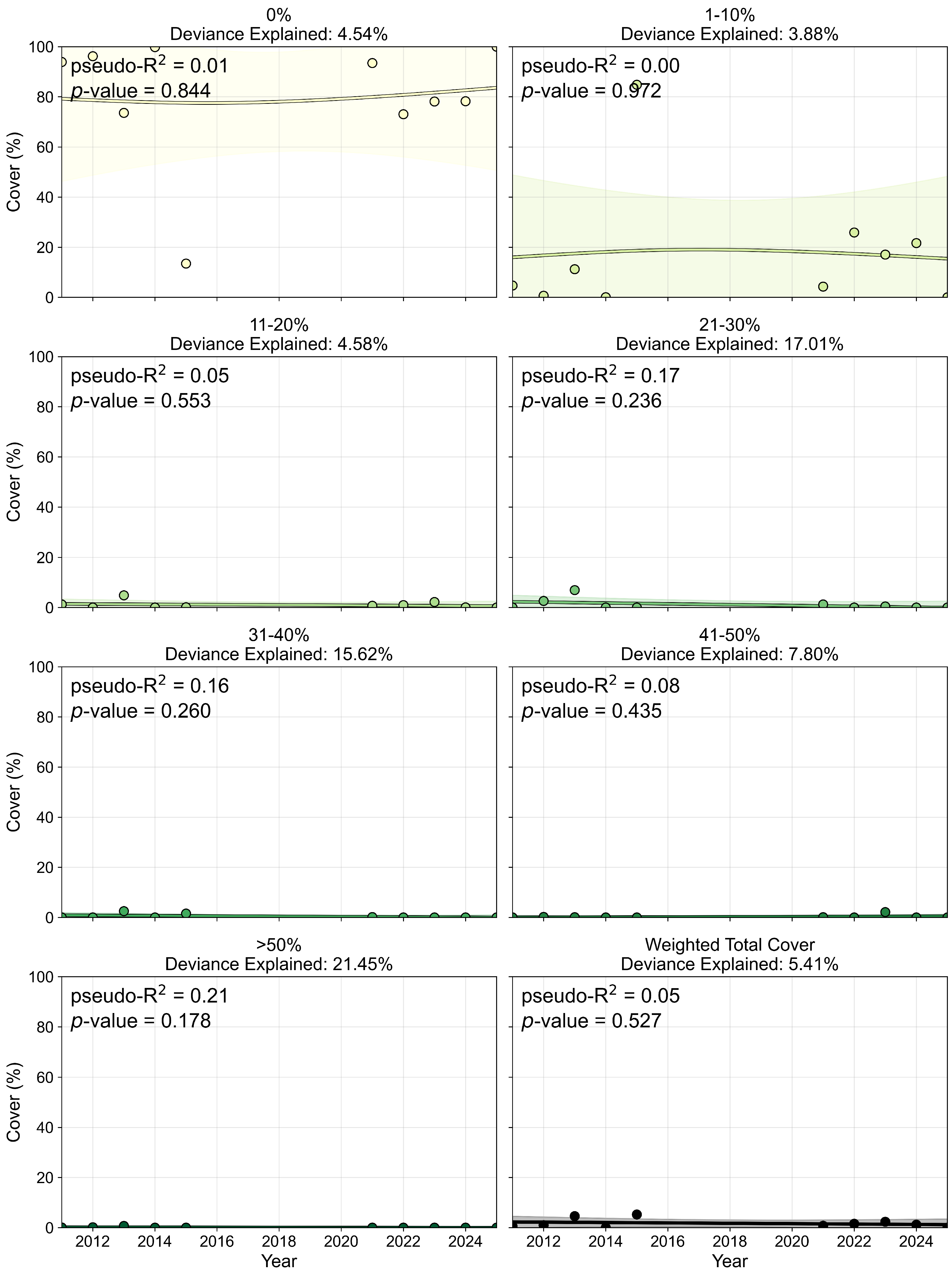

3.2.2. Percent Cover and Pixel Distribution Trends

3.3. Per-Pixel Persistence Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Spatial Trends in Seagrass Cover

4.2. Spatial Trends in Seagrass Persistence

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ENVI | ENvironment for Visualising Images |

| FLAASH | Fast Line-of-Sight Atmospheric Analysis of Hypercubes |

| GAM | Generalised Additive Model |

| GEE | Google Earth Engine |

| GLCM | Gray-Level Co-occurrence Matrix |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| PCA | Principal Components Analysis |

| PL | Planet Labs |

| RF | Random Forest |

| SNIC | Simple Non-Iterative Clustering |

| SWAN | Simulating WAves Nearshore |

| QB | Quickbird |

| TS | Total Seagrass |

| WV2 | WorldView 2 |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Appendix A.2

| Year | Field Data Points | Sensor | Pixel Size (m) | Atmospheric Corrections | Field Data Collection (dd/mm–dd/mm) | Image Acquisition (dd/mm) | Difference Field/Image Acquisition (days) | Tide at Image Acquisition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 3676 | WV2 | 2 | FLAASH® | 03/06–07/06 | 11/06 | 4 | Low |

| 2012 | 3064 | WV2 | 2 | FLAASH® | 07/06–10/06 | 12/06 | 2 | Mid (L > H) |

| 2013 | 3934 | QB | 2.4 | FLAASH® | 26/05–30/05 | 05/08 | 67 | Mid (H > L) |

| 2014 | 3437 | WV2 | 2 | FLAASH® | 14/07–16/07 | 01/07 | 15 | High |

| 2015 | 3543 | WV2 | 2 | FLAASH® | 15/06–17/06 | 01/07 | 14 | High |

| 2021 | 4379 | PL | 3 | Planet Labs | 07/06–10/06 | 17/06 | 7 | Mid (H > L) |

| 2022 | 4112 | PL | 3 | Planet Labs | 30/05–02/06 | 13/07 | 41 | High |

| 2023 | 4339 | PL | 3 | Planet Labs | 15/07–18/07 | 06/07 | 12 | High |

| 2024 | 5352 | PL | 3 | Planet Labs | 22/07–24/07 | 22/07 | 2 | High |

| 2025 | 4938 | PL | 3 | Planet Labs | 14/07–16/07 | 19/07 | 3 | Low |

Appendix B

Appendix B.1

| Year | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Accuracy (%) | 74 | 71 | 74 | 72 | 69 | 78 | 73 | 72 | 71 | 77 | 73 | 2.8 | |

| Producer’s (%) | Oceana serrulata | 87 | 85 | 84 | 95 | 86 | 82 | 80 | 77 | 85 | 88 | 85 | 4.9 |

| Zostera muelleri | 55 | 52 | 54 | 51 | 72 | 73 | 75 | 75 | 52 | 72 | 63 | 11.0 | |

| Halodule uninervis | 99 | 92 | 84 | 79 | 61 | 82 | 89 | 97 | 89 | 73 | 85 | 11.5 | |

| Halophila spinulosa | 54 | 51 | 47 | 46 | 53 | 47 | 49 | 45 | 41 | 51 | 48 | 4.0 | |

| Halophila ovalis | 79 | 60 | 78 | 67 | 67 | 87 | 75 | 67 | 77 | 88 | 75 | 9.2 | |

| Syringodium isoetifolium | 96 | 87 | 89 | 98 | 95 | 100 | - | - | - | - | 94 | 5.1 | |

| Mixed seagrass | 60 | 70 | 62 | 71 | 49 | 79 | 72 | 72 | 65 | 75 | 68 | 8.7 | |

| Lyngbya majuscula | 100 | - | 100 | - | - | - | - | - | 100 | - | 100 | 0.0 | |

| Sand | 56 | 71 | 61 | 68 | 60 | 60 | 62 | 59 | 55 | 66 | 62 | 5.1 | |

| Mixed benthos | 52 | 73 | 77 | 71 | 75 | 85 | 84 | 85 | 69 | 100 | 77 | 12.7 | |

| Consumer’s (%) | Oceana serrulata | 84 | 82 | 82 | 86 | 82 | 87 | 94 | 89 | 88 | 92 | 87 | 4.2 |

| Zostera muelleri | 80 | 78 | 80 | 65 | 73 | 85 | 73 | 78 | 60 | 84 | 76 | 8.0 | |

| Halodule uninervis | 75 | 72 | 82 | 77 | 64 | 84 | 76 | 73 | 74 | 84 | 76 | 6.1 | |

| Halophila spinulosa | 63 | 59 | 61 | 62 | 57 | 80 | 71 | 62 | 63 | 72 | 65 | 7.1 | |

| Halophila ovalis | 72 | 77 | 68 | 67 | 61 | 65 | 61 | 65 | 76 | 65 | 68 | 5.6 | |

| Syringodium isoetifolium | 74 | 83 | 71 | 72 | 70 | 100 | - | - | - | - | 78 | 11.6 | |

| Mixed seagrass | 66 | 62 | 56 | 66 | 53 | 66 | 59 | 57 | 46 | 63 | 59 | 6.6 | |

| Lyngbya majuscula | 89 | - | 99 | - | - | - | - | - | 100 | - | 96 | 6.1 | |

| Sand | 67 | 67 | 72 | 82 | 84 | 85 | 90 | 82 | 76 | 100 | 80 | 10.4 | |

| Mixed benthos | 63 | 62 | 70 | 67 | 75 | 62 | 75 | 78 | 61 | 71 | 68 | 6.3 |

| Year | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Accuracy (%) | 58 | 64 | 60 | 62 | 60 | 55 | 58 | 60 | 56 | 61 | 59 | 2.7 | |

| Producer’s (%) | No seagrass | 77 | 82 | 83 | 85 | 81 | 71 | 79 | 74 | 82 | 54 | 77 | 9.1 |

| 1–10% | 56 | 69 | 64 | 55 | 63 | 43 | 44 | 45 | 34 | 42 | 52 | 11.5 | |

| 11–20% | 48 | 71 | 56 | 58 | 60 | 43 | 46 | 59 | 58 | 55 | 55 | 8.1 | |

| 21–30% | 50 | 44 | 54 | 55 | 49 | 54 | 45 | 44 | 42 | 62 | 50 | 6.3 | |

| 31–40% | 51 | 67 | 36 | 64 | 46 | 47 | 54 | 55 | 45 | 63 | 53 | 9.8 | |

| 41–50% | 59 | 53 | 54 | 67 | 56 | 58 | 67 | 73 | 58 | 74 | 62 | 7.7 | |

| ≥50% | 65 | 62 | 73 | 66 | 64 | 69 | 74 | 68 | 67 | 72 | 68 | 4.0 | |

| Consumer’s (%) | No seagrass | 64 | 71 | 84 | 67 | 79 | 70 | 75 | 68 | 72 | 66 | 72 | 6.2 |

| 1–10% | 48 | 63 | 51 | 52 | 60 | 54 | 57 | 61 | 61 | 53 | 56 | 5.1 | |

| 11–20% | 50 | 52 | 44 | 56 | 47 | 46 | 45 | 48 | 49 | 45 | 48 | 3.7 | |

| 21–30% | 53 | 60 | 44 | 55 | 49 | 48 | 45 | 54 | 42 | 47 | 50 | 5.7 | |

| 31–40% | 56 | 54 | 66 | 55 | 47 | 46 | 47 | 51 | 44 | 49 | 52 | 6.5 | |

| 41–50% | 66 | 67 | 57 | 67 | 58 | 48 | 56 | 57 | 44 | 94 | 60 | 13.8 | |

| ≥50% | 85 | 97 | 97 | 95 | 91 | 75 | 91 | 92 | 88 | 91 | 90 | 6.5 |

Appendix B.2

References

- McHenry, J.; Rassweiler, A.; Hernan, G.; Uejio, C.; Pau, S.; Dubel, A.; Lester, S. Modelling the Biodiversity Enhancement Value of Seagrass Beds. Divers. Distrib. 2021, 27, 2036–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, J. Biodiversity and the Functioning of Seagrass Ecosystems. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2006, 311, 233–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christianen, M.; van Belzen, J.; Herman, P.; van Katwijk, M.; Lamers, L.; van Leent, P.; Bouma, T. Low-Canopy Seagrass Beds Still Provide Important Coastal Protection Services. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e62413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondiviela, B.; Losada, I.J.; Lara, J.; Maza, M.; Galván, C.; Bouma, T.; van Belzen, J. The Role of Seagrasses in Coastal Protection in a Changing Climate. Coast. Eng. 2014, 87, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, R.; d’Arge, R.; de Groot, R.; Farber, S.; Grasso, M.; Hannon, B.; Limburg, K.; Naeem, S.; O’Neill, R.; Paruelo, J.; et al. The Value of the World’s Ecosystem Services and Natural Capital. Nature 1997, 387, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, E.; Rowden, A.; Attrill, M.; Bossey, S.; Jones, M. The Importance of Seagrass Beds as a Habitat for Fishery Species. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. Annu. Rev. 2001, 39, 269–303. [Google Scholar]

- Bertelli, C.; Unsworth, R. Protecting the Hand That Feeds Us: Seagrass (Zostera Marina) Serves as Commercial Juvenile Fish Habitat. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014, 83, 425–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, C.; Marbà, N.; Gacia, E.; Fourqurean, J.; Beggins, J.; Barrón, C.; Apostolaki, E. Seagrass Community Metabolism: Assessing the Carbon Sink Capacity of Seagrass Meadows. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2010, 24, GB4032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human, L.; Snow, G.; Adams, J.; Bate, G.; Yang, S.C. The Role of Submerged Macrophytes and Macroalgae in Nutrient Cycling: A Budget Approach. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2015, 154, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordlund, L.; Jackson, E.; Nakaoka, M.; Samper-Villarreal, J.; Beca-Carretero, P.; Creed, J. Seagrass Ecosystem Services—What’s Next? Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 134, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Amaral Camara Lima, M.; Bergamo, T.; Ward, R.; Joyce, C. A Review of Seagrass Ecosystem Services: Providing Nature-Based Solutions for a Changing World. Hydrobiologia 2023, 850, 2655–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unsworth, R.; McKenzie, L.; Collier, C.; Cullen-Unsworth, L.; Duarte, C.; Eklöf, J.; Jarvis, J.; Jones, B.; Nordlund, L. Global Challenges for Seagrass Conservation. Ambio 2019, 48, 801–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yu, X.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Q.; Zuo, J.; Yu, S.; Guo, R. A Review of Seagrass Bed Pollution. Water 2023, 15, 3754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unsworth, R.; Ambo-Rappe, R.; Jones, B.; La Nafie, Y.; Irawan, A.; Hernawan, U.; Moore, A.; Cullen-Unsworth, L. Indonesia’s Globally Significant Seagrass Meadows Are under Widespread Threat. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 634, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen-Unsworth, L.; Unsworth, R. Strategies to Enhance the Resilience of the World’s Seagrass Meadows. J. Appl. Ecol. 2016, 53, 967–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, O.; Arias-Ortiz, A.; Duarte, C.; Kendrick, G.; Lavery, P. Impact of Marine Heatwaves on Seagrass Ecosystems. In Ecosystem Collapse and Climate Change; Canadell, J., Jackson, R., Eds.; Ecological Studies; Springer: Cambridge, UK, 2021; Volume 241, pp. 345–364. [Google Scholar]

- Gouvêa, L.; Fragkopoulou, E.; Araújo, M.; Serrão, E.; Assis, J. Seagrass Biodiversity Under the Latest-Generation Scenarios of Projected Climate Change. J. Biogeogr. 2024, 52, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, D.; Lukatelich, R.; Bastyan, G.; McComb, A. Effect of Boat Moorings on Seagrass Beds near Perth, Western Australia. Aquat. Bot. 1989, 26, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, K.; Suonpää, A.; Mallinson, J. The Impacts of Anchoring and Mooring in Seagrass, Studland Bay, Dorset, UK. Underw. Technol. 2010, 29, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahayu, Y.; Kendrick, G.; Masqué, P.; Kiswara, W.; Salim, H.; Lubis, A.; Vanderklift, M. Impacts of Dredging and Restoration on Sedimentary Carbon Stocks in Seagrass Meadows of Pari Island, Indonesia. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 25551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvell, C.; Lamb, J. Disease Outbreaks Can Threaten Marine Biodiversity. In Marine Disease Ecology; Behringer, D., Silliman, B., Lafferty, K., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020; pp. 141–158. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, B.; Trevathan-Tackett, S.; Neuhauser, S.; Govers, L. Review: Host-pathogen Dynamics of Seagrass Diseases under Future Global Change. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 134, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waycott, M.; Longstaff, B.; Mellors, J. Seagrass Population Dynamics and Water Quality in the Great Barrier Reef Region: A Review and Future Research Directions. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2005, 51, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraser, M.; Kendrick, G.; Statton, J.; Hovey, R.; Zavala-Perez, A. Extreme Climate Events Lower Resilience of Foundation Seagrass at Edge of Biogeographical Range. J. Ecol. 2014, 102, 1528–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendrick, G.; Nowicki, R.; Olsen, Y.; Strydom, S.; Fraser, M.; Sinclair, E.; Statton, J.; Hovey, R.; Thomson, J.; Burkholder, D.; et al. A Systematic Review of How Multiple Stressors From an Extreme Event Drove Ecosystem-Wide Loss of Resilience in an Iconic Seagrass Community. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 6, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neckles, H.; Kopp, B.; Peterson, B.; Pooler, P. Integrating Scales of Seagrass Monitoring to Meet Conservation Needs. Estuaries Coasts 2012, 35, 23–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, N.; Lavery, P. Monitoring Seagrass Ecosystem Health—The Role of Perception in Defining Health and Indicators. Ecosyst. Health 2000, 6, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernawan, U.; Rahmawati, S.; Ambo-Rappe, R.; Sjafrie, N.; Hadiyanto, H.; Yusup, D.; Nugraha, A.; La Nafie, Y.; Adi, W.; Prayudha, B.; et al. The First Nation-Wide Assessment Identifies Valuable Blue-Carbon Seagrass Habitat in Indonesia Is in Moderate Condition. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 782, 146818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unsworth, R.; Collier, C.; Waycott, M.; McKenzie, L.; Cullen-Unsworth, L. A Framework for the Resilience of Seagrass Ecosystems. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 100, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendrick, G.; Duarte, C.; Marbà, N. Clonality in Seagrasses, Emergent Properties and Seagrass Landscapes. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2005, 290, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullström, M.; de la Torre Castro, M.; Bandeira, S.; Björk, M.; Dahlberg, M.; Kautsky, N.; Rönnbäck, P.; Öhman, M. Seagrass Ecosystems in the Western Indian Ocean. AMBIO J. Hum. Environ. 2002, 31, 588–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, R.; Williams, M.; Marion, S.; Wilcox, D.; Carruthers, T.; Moore, K.; Kemp, M.; Dennison, W.; Rybicki, N.; Bergstrom, P.; et al. Long-Term Trends in Submersed Aquatic Vegetation (SAV) in Chesapeake Bay, USA, Related to Water Quality. Estuaries Coasts 2010, 33, 1144–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, R.; Heck, K. The Dynamics of Seagrass Ecosystems: History, Past Accomplishments, and Future Prospects. Estuaries Coasts 2023, 46, 1653–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macreadie, P.; Trevathan-Tackett, S.; Skilbeck, C.; Sanderman, J.; Curlevski, N.; Jacobsen, G.; Seymour, J. Losses and Recovery of Organic Carbon from a Seagrass Ecosystem Following Disturbance. Proc. R. Soc. B 2015, 282, 20151537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourque, A.; Kenworthy, W.; Fourqurean, J. Impacts of Physical Disturbance on Ecosystem Structure in Subtropical Seagrass Meadows. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2015, 540, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soissons, L.; Li, B.; Han, Q.; van Katwijk, M.; Ysebaert, T.; Herman, P.; Bouma, T. Understanding Seagrass Resilience in Temperate Systems: The Importance of Timing of the Disturbance. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 66, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgeloe, J.; Severn-Ellis, A.; Bayer, P.; Mehravi, S.; Breed, M.; Krauss, S.; Batley, J.; Kendrick, G.; Sinclair, E. Extensive Polyploid Clonality Was a Successful Strategy for Seagrass to Expand into a Newly Submerged Environment. Proc. R. Soc. B 2022, 289, 20220538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roelfsema, C.M.; Kovacs, E.M.; Phinn, S.R. Field Data Sets for Seagrass Biophysical Properties for the Eastern Banks, Moreton Bay, Australia, 2004–2014. Sci. Data 2015, 2, 150040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Tussenbroek, B.; Cortés, J.; Collin, R.; Fonseca, A.; Gayle, P.; Guzmán, H.; Jácome, G.; Juman, R.; Koltes, K.; Oxenford, H.; et al. Long-Term Study of Seagrass Beds Reveals Local Variations, Shifts in Community Structure and Occasional Collapse. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e90600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumstark, R.; Dixon, B.; Carlson, P.; Palandro, D.; Kolasa, K. Alternative Spatially Enhanced Integrative Techniques for Mapping Seagrass in Florida’s Marine Ecosystem. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2013, 34, 1248–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, A.G.; Brando, V.E.; Anstee, J.M. Retrospective Seagrass Change Detection in a Shallow Coastal Tidal Australian Lake. Remote Sens. Environ. 2005, 97, 415–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudby, A.; Newman, C.; Shaghude, Y.; Muhando, C. Simple and Effective Monitoring of Historic Changes in Nearshore Environments Using the Free Archive of Landsat Imagery. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2010, 12, S116–S122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roelfsema, C.M.; Lyons, M.; Kovacs, E.M.; Maxwell, P.; Saunders, M.I.; Samper-Villarreal, J.; Phinn, S.R. Multi-Temporal Mapping of Seagrass Cover, Species and Biomass: A Semi-Automated Object Based Image Analysis Approach. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 150, 172–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilminster, K.; McMahon, K.; Waycott, M.; Kendrick, G.; Scanes, P.; McKenzie, L.; O’Brien, K.; Lyons, M.; Ferguson, A.; Maxwell, P.; et al. Unravelling Complexity in Seagrass Systems for Management: Australia as a Microcosm. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 534, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart, J.; Hammerman, N.; Golding, K.; Markey, K.; Kovacs, E.; Roelfsema, C. Decadal Monitoring Shows Seagrass Decline and Community Shifts Following Environmental Disturbance in Moreton Bay, South-Eastern Queensland, Australia. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2025, 76, MF25049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowicki, R.; Thomson, J.; Burkholder, D.; Fourqurean, J.; Heithaus, M. Predicting Seagrass Recovery Times and Their Implications Following an Extreme Climate Event. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2017, 567, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, C.; Navarrete, S.; Jackson, E. Reactive Persistence, Spatial Management, and Conservation of Metapopulations: An Application to Seagrass Restoration. Ecol. Appl. 2023, 33, e2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, P.; Connolly, R.; Roelfsema, C.; Burfiend, D.; Udy, J.; O’Brien, K.; Saunders, M.; Barnes, R.; Olds, A.; Hendersen, C.; et al. Seagrasses of Moreton Bay Quandamooka: Diversity, Ecology and Resilience. In Moreton Bay Quandamooka & Catchment: Past, Present, and Future; Tibbets, I., Rothlisberg, P., Neil, D., Homburg, T., Brewer, D., Arthington, A., Eds.; The Moreton Bay Foundation: Brisbane, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Björk, M.; Short, F.; McLeod, E.; Beer, S. Managing Seagrasses for Resilience to Climate Change; The International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN): Gland, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, B.; Lummis, S.; Anderson, S.; Kroeker, K. Unexpected Resilience of a Seagrass System Exposed to Global Stressors. Glob. Change Biol. 2017, 24, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collier, C.; Langlois, L.; McMahon, K.; Udy, J.; Rasheed, M.; Lawrence, E.; Carter, A.; Fraser, M.; McKenzie, L. What Lies beneath: Predicting Seagrass below-Ground Biomass from above-Ground Biomass, Environmental Conditions and Seagrass Community Composition. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 121, 107156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudby, A.; Jupiter, S.; Roelfsema, C.; Lyons, M.; Phinn, S. Mapping Coral Reef Resilience Indicators Using Field and Remotely Sensed Data. Remote Sens. 2013, 5, 1311–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Fong, C.; Wu, R. The Effects of Seagrass (Zostera Japonica) Canopy Structure on Associated Fauna: A Study Using Artificial Seagrass Units and Sampling of Natural Beds. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2001, 259, 23–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, M.; Fourqurean, J.; Koehl, M. Effect of Seagrass on Current Speed: Importance of Flexibility vs. Shoot Density. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 6, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, K.; Waycott, M.; Maxwell, P.; Kendrick, G.; Udy, J.; Ferguson, A.; Kilminster, K.; Scanes, P.; McKenzie, L.; McMahon, K.; et al. Seagrass Ecosystem Trajectory Depends on the Relative Timescales of Resistance, Recovery and Disturbance. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 134, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHenry, J.; Rassweiler, A.; Lester, S. Seagrass Ecosystem Services Show Complex Spatial Patterns and Associations. Ecosyst. Serv. 2023, 63, 101543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco Rivera, D.; Diederiks, F.; Hammerman, N.; Staples, T.; Kovacs, E.; Markey, K.; Roelfsema, C. Remote Sensing Reveals Multidecadal Trends in Coral Cover at Heron Reef, Australia. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS). ReefCloud; AIMS: Cape Cleveland, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorelick, N.; Hancher, M.; Dixon, M.; Ilyushchenko, S.; Thau, D.; Moore, R. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-scale Geospatial Analysis for Everyone. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 202, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christenhusz, M.; Fay, M.; Byng, J. (Eds.) The Global Flora: GLOVAP Nomenclature Part 1; Plant Gateway Ltd.: Bradford, UK, 2018; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, M.; Phinn, S.; Roelfsema, C. Integrating Quickbird Multi-Spectral Satellite and Field Data: Mapping Bathymetry, Seagrass Cover, Seagrass Species and Change in Moreton Bay, Australia in 2004 and 2007. Remote Sens. 2011, 3, 42–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Rivero, M.; Beijbom, O.; Rodriguez-Ramirez, A.; Bryant, D.; Ganase, A.; Gonzalez-Marrero, Y.; Herrera-Reveles, A.; Kennedy, E.; Kim, C.; Lopez-Marcano, S.; et al. Monitoring of Coral Reefs Using Artificial Intelligence: A Feasible and Cost-Effective Approach. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leriche, A.; Boudouresque, C.F.; Monestiez, P.; Pasqualini, V. An Improved Method to Monitor the Health of Seagrass Meadows Based on Kriging. Aquat. Bot. 2011, 95, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, K.A.; Wilcox, D.J.; Orth, R.J. Analysis of the Abundance of Submersed Aquatic Vegetation Communities in the Chesapeake Bay. Estuaries 2000, 23, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lathrop, R.G.; Montesano, P.; Haag, S. A Multi-scale Segmentation Approach to Mapping Seagrass Habitats Using Airborne Digital Camera Imagery. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2006, 72, 665–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossa, D.; Cossa, M.; Nhaca, J.; Timba, I.; Chunguane, Y.; Vetina, A.; Macia, A.; Gullström, M.; Infantes, E. Restoring Halodule Uninervis: Evaluating Planting Methods and Biodiversity. Restor. Ecol. 2025, 33, e14382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooley, T.; Anderson, G.; Felde, G.; Hoke, M.; Ratkowski, A.; Chetwynd, J.; Gardner, J.; Adler-Golden, S.; Matthew, M.; Berk, A.; et al. FLAASH, a MODTRAN4-based Atmospheric Correction Algorithm, Its Application and Validation. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Toronto, ON, Canada, 24–28 June 2002; Volume 3, pp. 1414–1418. [Google Scholar]

- Wicaksono, P. Improving the Accuracy of Multispectral-based Benthic Habitats Mapping Using Image Rotations: The Application of Principle Component Analysis and Independent Component Analysis. Eur. J. Remote Sens. 2016, 49, 433–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haralick, R.; Shanmugam, K.; Dinstein, I. Textural Features for Image Classification. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1973, SMC-3, 610–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achanta, R.; Süsstrunk, S. Superpixels and Polygons Using Simple Non-iterative Clustering. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 4895–4904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattiaratchi, C.B.; Harris, P.T. Hydrodynamic and Sand-Transport Controls on Enechelon Sandbank Formation: An Example from Moreton Bay, Eastern Australia. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2003, 53, 1101–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veevers, J.J. Beach Sand of SE Australia Traced by Zircon Ages through Ordovician Turbidites and S-Type Granites of the Lachlan Orogen to Africa/Antarctica: A Review. Aust. J. Earth Sci. 2015, 62, 385–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queensland Department of Environment and Science. Queensland Satellite-Derived Bathymetry Data—Moreton Bay 2022–2023; Queensland Department of Environment and Science: Brisbane, Australia, 2023.

- Milford, S.N.; Church, J.A. Simplified Circulation and Mixing Models of Moreton Bay, Queensland. Aust. J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 1977, 28, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeck, E.; Udy, J.; Maxwell, P.; Grinham, A.; Moffatt, D.; Senthikumar, S.; Udy, D.; Weber, T. Water Quality in Moreton Bay and Its Major Estuaries: Change over Two Decades (2000–2018). In Moreton Bay Quandamooka & Catchment: Past, Present and Future; The Moreton Bay Foundation: Brisbane, Australia, 2019; pp. 187–210. [Google Scholar]

- Cowley, D.; Harris, D. Coastal Exposure to Swell Along a Complex, Tropical Continental Shelf and Impacts on Coastal Morphology. in preparation.

- Booij, N.; Holthuijsen, L.H.; Ris, R. The “Swan" Wave Model for Shallow Water. In Proceedings of the Coastal Engineering, Orlando, FL, USA, 2–6 September 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrant, T.; Greenslade, D.; Hemer, M.; Trenham, C. A Global Wave Hindcast Focussed on the Central and South Pacific; CAWCR Technical Report 070; The Centre for Australian Weather and Climate Research [CAWCR]: Hobart, TAS, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, G.A.; Hemer, M.; Greenslade, D.; Trenham, C.; Zieger, S.; Durrant, T. Global Wave Hindcast with Australian and Pacific Island Focus: From Past to Present. Geosci. Data J. 2021, 8, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congalton, R.; Green, K. Assessing the Accuracy of Remotely Sensed Data: Principles and Practices, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, M. Earth Engine Public Data Catalog; Google: Mountain View, CA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, M.; Roelfsema, C.; Kennedy, E.; Kovacs, E.; Borrego-Acevedo, R.; Markey, K.; Roe, M.; Yuwono, D.; Harris, D.; Phinn, S.; et al. Mapping the World’s Coral Reefs Using a Global Multiscale Earth Observation Framework. Remote Sens. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 6, 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, M.; Murray, N.; Kennedy, E.V.; Kovacs, E.M.; Castro-Sanguino, C.; Phinn, S.; Borrego-Acevedo, R.; Ordoñez Alvarez, A.; Say, C.; Tudman, P.; et al. New Global Area Estimates for Coral Reefs from High-Resolution Mapping. Cell Rep. Sustain. 2024, 1, 100015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beven, K.; Lamb, R. The Uncertainty Cascade in Model Fusion. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 2017, 408, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servén, D.; Brummitt, C. pyGAM: Generalized Additive Models in Python; GitHub: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Virtanen, P.; Gomers, R.; Oliphant, T.; Haberland, M.; Reddy, T.; Courapeau, D.; Burovski, E.; Peterson, P.; Weckesser, W.; Bright, J.; et al. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental Algorithms for Scientific Computing in Python. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McFadden, D. Conditional Logit Analysis of Qualitative Choice Behaviour. In Frontiers in Econometrics; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1972; pp. 1–58. [Google Scholar]

- Lanfredi, M.; Simoniello, T.; Macchiato, M. Temporal Persistence in Vegetation Cover Changes Observed from Satellite: Development of an Estimation Procedure in the Test Site of the Mediterranean Italy. Remote Sens. Environ. 2004, 93, 565–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, S.; O’Neil, J.; Udy, J.; Ahern, K.; O’Sullivan, C.; Dennison, W. Blooms of the Cyanobacterium Lyngbya Majuscula in Coastal Queensland, Australia: Disparate Sites, Common Factors. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2005, 51, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.; Bujang, J.; Zakaria, M.; Hashim, M. The Application of Remote Sensing to Seagrass Ecosystems: An Overview and Future Research Prospects. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2015, 36, 61–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harah, M.; Bujang, J. Occurrence and Distribution of Seagrasses in Waters of Perhentian Island Archipelago, Malaysia. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2013, 8, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Unsworth, R.; van Keulen, M.; Coles, R. Seagrass Meadows in a Globally Changing Environment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014, 83, 383–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenworthy, W.; Wyllie-Echeverria, S.; Coles, R.; Pergent-Martini, C. Seagrass Conservation Biology: An Interdisciplinary Science for Protection of the Seagrass Biome. In Seagrasses: Biology, Ecology and Conservation; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Pulliza, D.; Wilson, J.; Darmawan, A.; Campbell, S.; Andréfouët, S. Ecoregional Scale Seagrass Mapping: A Tool to Support Resilient MPA Network Design in the Coral Triangle. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2013, 80, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koedsin, W.; Intararuang, W.; Ritchie, R.; Huete, A. An Integrated Field and Remote Sensing Method for Mapping Seagrass Species, Cover, and Biomass in Southern Thailand. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicaksono, P.; Lazuardi, W. Assessment of PlanetScope Images for Benthic Habitat and Seagrass Species Mapping in a Complex Optically Shallow Water Environment. In Fine Resolution Remote Sensing of Species in Terrestrial and Coastal Ecosystems, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Selgrath, J.; Roelfsema, C.; Gergel, S.; Vincent, A. Mapping for Coral Reef Conservation: Comparing the Value of Participatory and Remote Sensing Approaches. Ecosphere 2016, 7, e01325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Zhou, T.; Zou, Z.; Zhao, X.; Huang, K.; Wu, H. Mapping Forest Biomass Using Remote Sensing and National Forest Inventory in China. Forests 2014, 5, 1267–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagawa, T.; Boisner, E.; Komatsu, T.; Mustapha, K.; Hattour, A.; Kosaka, N.; Miyazaki, S. Using Bottom Surface Reflectance to Map Coastal Marine Areas: A New Application Method for Lyzenga’s Model. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2010, 31, 3051–3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benfield, S.L.; Guzman, H.M.; Mair, J.M.; Young, J.A.T. Mapping the Distribution of Coral Reefs and Associated Sublittoral Habitats in Pacific Panama: A Comparison of Optical Satellite Sensors and Classification Methodologies. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2007, 28, 5047–5070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, E.; Roelfsema, C.; Lyons, M.; Zhao, S.; Phinn, S. Seagrass Habitat Mapping: How Do Landsat 8 OLI, Sentinel-2, ZY-3A, and Worldview-3 Perform? Remote Sens. Lett. 2018, 9, 686–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumby, P.J.; Green, E.P.; Edwards, A.J.; Clark, C.D. Coral Reef Habitat Mapping: How Much Detail Can Remote Sensing Provide? Mar. Biol. 1997, 130, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanington, P.; Hunnam, K.; Johnstone, R. Widespread Loss of the Seagrass Syringodium Isoetifolium after a Major Flood Event in Moreton Bay, Australia: Implications for Benthic Processes. Aquat. Bot. 2015, 120, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udy, J.; Udy, J.; Penna, R.; Dehaudt, B.; Venables, B. Seagrass Distribution Within Moreton Bay Marine Park: Seagrass Response to the 2022 Flood: Results of Two Years of Post-Flood Surveys and Comparison to Pre-Flood Distribution; Technical report; Science Under Sail Australia: Wellington Point, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkman, H. Decline of Seagrass in Northern Areas of Moreton Bay, Queensland. Aquat. Bot. 1978, 5, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preen, A.; Lee Long, W.; Coles, R. Flood and Cyclone Related Loss, and Partial Recovery, of More than 1000 km2 of Seagrass in Hervey Bay, Queensland, Australia. Aquat. Bot. 1995, 52, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinham, A.; Costantini, T.; Dearing, N.; Jackson, C.; Klein, C.; Lovelock, C.; Pandolfi, J.; Eyal, G.; Linde, M.; Dunbabin, M.; et al. Nitrogen Loading Resulting from Major Floods and Sediment Resuspension to a Large Coastal Embayment. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 918, 170646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y.; Nakaoka, M. Morphological Variation in the Tropical Seagrasses, Cymodocea Serrulata and C. Rotundata, in Response to Sediment Conditions and Light Attenuation. Bot. Mar. 2006, 49, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, C.J.; Waycott, M.; Ospina, A.G. Responses of Four Indo-West Pacific Seagrass Species to Shading. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2012, 65, 342–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, K.; Hennessy, A.; McGrath, A.; Daly, R.; Gaylard, S.; Turner, A.; Cameron, J.; Lewis, M.; Fernandes, M.B. Using Hyperspectral Imagery to Investigate Large-scale Seagrass Cover and Genus Distribution in a Temperate Coast. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abal, E.; Dennison, W. Seagrass Depth Range and Water Quality in Southern Moreton Bay, Queensland, Australia. Mar. Freshw. Res. 1996, 47, 763–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbes, B.; Grinham, A.; Neil, D.; Olds, A.; Maxwell, P.; Connolly, R.; Weber, T.; Udy, N.; Udy, J. Moreton Bay and Its Estuaries: A Sub-tropical System Under Pressure from Rapid Population Growth. In Estuaries of Australia in 2050 and Beyond; Wolanski, E., Ed.; Estuaries of the World; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 203–222. [Google Scholar]

- Beecroft, R.; Grinham, A.; Albert, S.; Perez, L.; Cossu, R. Suspended Sediment Transport in Context of Dredge Placement Operations in Moreton Bay, Australia. J. Waterw. Port Coast. Ocean Eng. 2019, 145, 05019001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traganos, D.; Pertiwi, A.P.; Lee, C.B.; Blume, A.; Poursanidis, D.; Shapiro, A. Earth Observation for Ecosystem Accounting: Spatially Explicit National Seagrass Extent and Carbon Stock in Kenya, Tanzania, Mozambique and Madagascar. Remote Sens. Ecol. Conserv. 2022, 8, 778–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, A.; Rayment, G.; Reilly, N.; Best, E. A Preliminary Assessment of Sediment and Nutrient Exports from Queensland Coastal Catchments; Heritage Environment Technical Report 5; Queensland Government: Brisbane, Australia, 1993.

- Steven, A.; Carlin, G.; Revill, A.; McLaughlin, J.; Chotikarn, P.; Fry, G.; Moeseneder, C.; Franklin, H. Distribution, Volume and Impact of Sediment Deposited by 2011 and 2013 Floods on Marine and Estuarine Habitats in Moreton Bay; Final Report for Healthy Waterways Limited; University of Technology Sydney: Sydney, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Golding, K.; Eyal, G.; Staples, T.; Kim, S.; Byrne, I.; Lovelock, C.; Klein, C.; Pandolfi, J.; Hammerman, N. The Impacts of Flooding on the High-Latitude Coral Communities Within an Urban Embayment, Quandamooka (Moreton Bay). in preparation.

- Erftemeijer, P.L.A.; Lewis, R.R.R., III. Environmental Impacts of Dredging on Seagrasses: A Review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2006, 52, 1553–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, W. The Sedimentary Framework of Moreton Bay, Queensland. Mar. Freshw. Res. 1970, 21, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, R.; Smith, T.; Maxwell, P.; Olds, A.; Macreadie, P.; Sherman, C. Highly Disturbed Populations of Seagrass Show Increased Resilience but Lower Genotypic Diversity. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, L.J.; Nordlund, L.M.; Jones, B.L.; Cullen-Unsworth, L.C.; Roelfsema, C.; Unsworth, R.K.F. The Global Distribution of Seagrass Meadows. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 074041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunic, J.C.; Brown, C.J.; Connolly, R.M.; Turschwell, M.P.; Côté, I.M. Long-Term Declines and Recovery of Meadow Area across the World’s Seagrass Bioregions. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 4096–4109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udy, K.; Fritsch, M.; Meyer, K.M.; Grass, I.; Hanß, S.; Hartig, F.; Kneib, T.; Kreft, H.; Kukunda, C.B.; Pe’er, G.; et al. Environmental Heterogeneity Predicts Global Species Richness Patterns Better than Area. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2021, 30, 842–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, C.M.; Krause-Jensen, D. Export from Seagrass Meadows Contributes to Marine Carbon Sequestration. Front. Mar. Sci. 2017, 4, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lybolt, M.; Neil, D.; Zhao, J.; Feng, Y.; Yu, K.F.; Pandolfi, J. Instability in a Marginal Coral Reef: The Shift from Natural Variability to a Human-Dominated Seascape. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2011, 9, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammerman, N.M.; Roff, G.; Lybolt, T.; Eyal, G.; Pandolfi, J.M. Unraveling Moreton Bay Reef History: An Urban High-Latitude Setting for Coral Development. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 884850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuttriss, A.K.; Prince, J.B.; Castley, J.G. Seagrass Communities in Southern Moreton Bay, Australia: Coverage and Fragmentation Trends between 1987 and 2005. Aquat. Bot. 2013, 108, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Lemckert, C. The Response of the River Plume to the Flooding in Moreton Bay, Australia. In Proceedings of the 11th International Coastal Symposium, Szczecin, Poland, 9–14 May 2011; Volume SI 64, pp. 1214–1218. [Google Scholar]

- Phinn, S.; Roelfsema, C.M.; Dekker, A.G.; Brando, V.E.; Anstee, J.M. Mapping Seagrass Species, Cover and Biomass in Shallow Waters: An Assessment of Satellite Multi-Spectral and Airborne Hyper-Spectral Imaging Systems in Moreton Bay (Australia). Remote Sens. Environ. 2008, 112, 3413–3425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cowley, D.; Carrasco Rivera, D.E.; Smart, J.N.; Hammerman, N.M.; Golding, K.M.; Diederiks, F.F.; Roelfsema, C.M. Insights into Seagrass Distribution, Persistence, and Resilience from Decades of Satellite Monitoring. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 4033. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244033

Cowley D, Carrasco Rivera DE, Smart JN, Hammerman NM, Golding KM, Diederiks FF, Roelfsema CM. Insights into Seagrass Distribution, Persistence, and Resilience from Decades of Satellite Monitoring. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):4033. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244033

Chicago/Turabian StyleCowley, Dylan, David E. Carrasco Rivera, Joanna N. Smart, Nicholas M. Hammerman, Kirsten M. Golding, Faye F. Diederiks, and Chris M. Roelfsema. 2025. "Insights into Seagrass Distribution, Persistence, and Resilience from Decades of Satellite Monitoring" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 4033. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244033

APA StyleCowley, D., Carrasco Rivera, D. E., Smart, J. N., Hammerman, N. M., Golding, K. M., Diederiks, F. F., & Roelfsema, C. M. (2025). Insights into Seagrass Distribution, Persistence, and Resilience from Decades of Satellite Monitoring. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 4033. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244033