Multi-Domain Intelligent State Estimation Network for Highly Maneuvering Target Tracking with Non-Gaussian Noise

Highlights

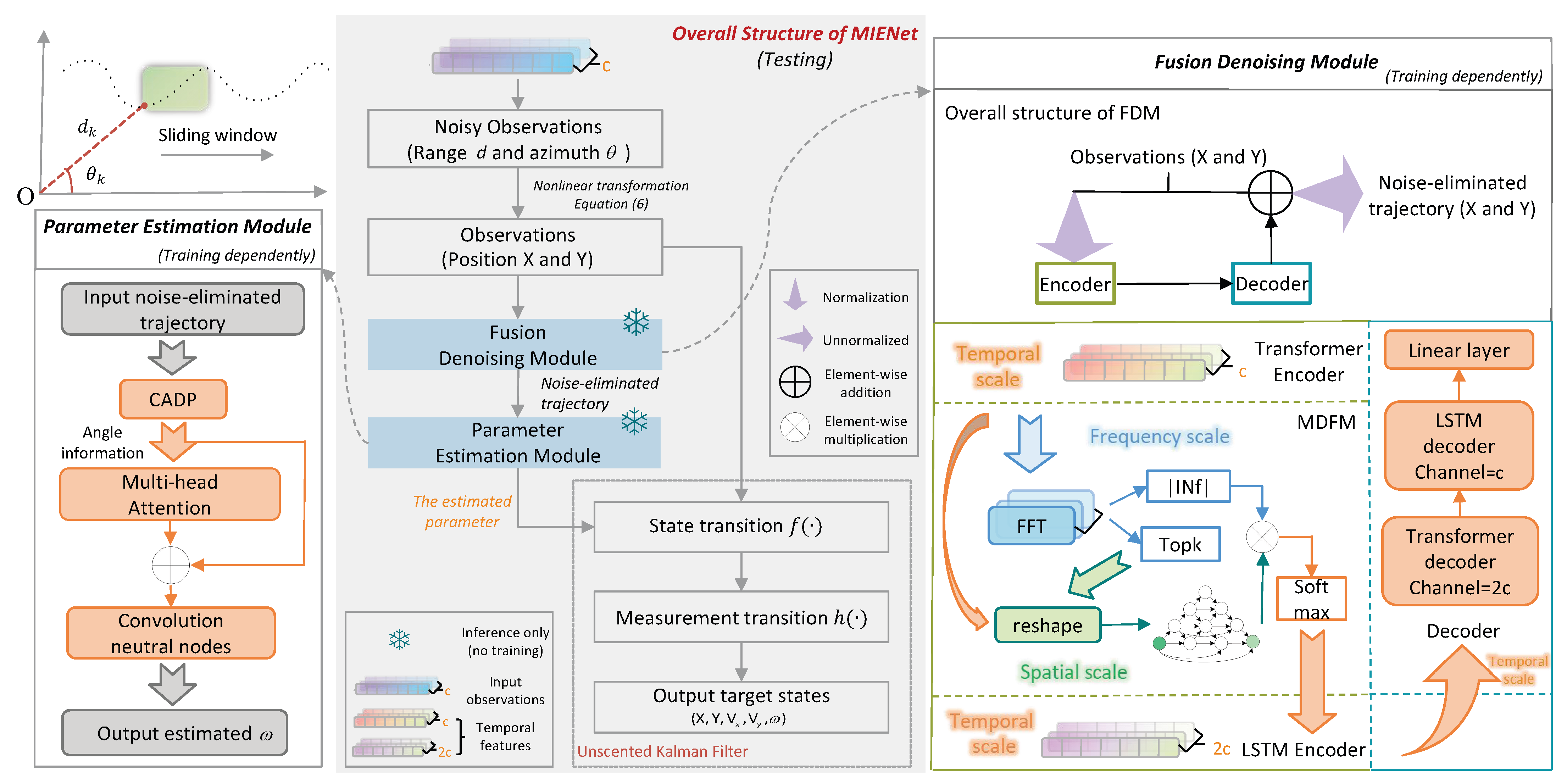

- We propose a Multi-domain Intelligent Estimation Network (MIENet) for tracking highly maneuvering targets with non-Gaussian noise.

- The MIENet consists of a fusion denoising model (FDM) and a parameter estimation model (PEM), which jointly enhance robustness and accuracy in state estimation for radar trajectory and remote sensing video data.

- The proposed MIENet achieves robust tracking performance across various noise intensities and distributions, significantly reducing observation noise and improving estimation stability.

- Our approach effectively generalizes from radar trajectory simulation to real satellite video tracking tasks, showing great potential for intelligent remote sensing target tracking in complex environments.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We propose a MIENet to estimate target states and motion patterns from non-Gaussian observation noise. The multi-domain information of target trajectories can be well incorporated, thus helping to infer the latent state of targets.

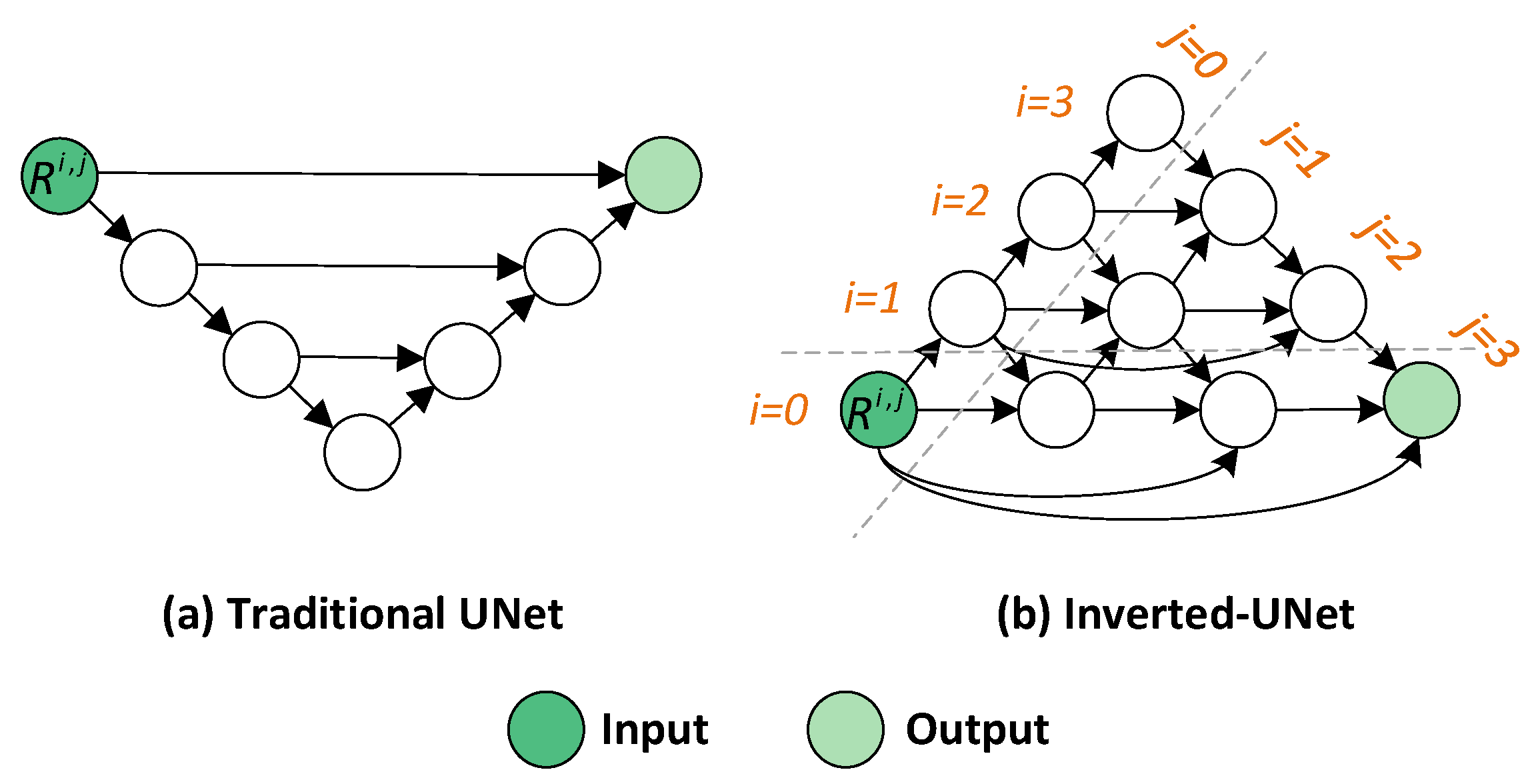

- We design an FDM to handle noise with varying intensities and distributions. It employs a novel Inverted-UNet and FFT-based weighting to integrate temporal, spatial, and frequency-domain features within an encoder–decoder framework.

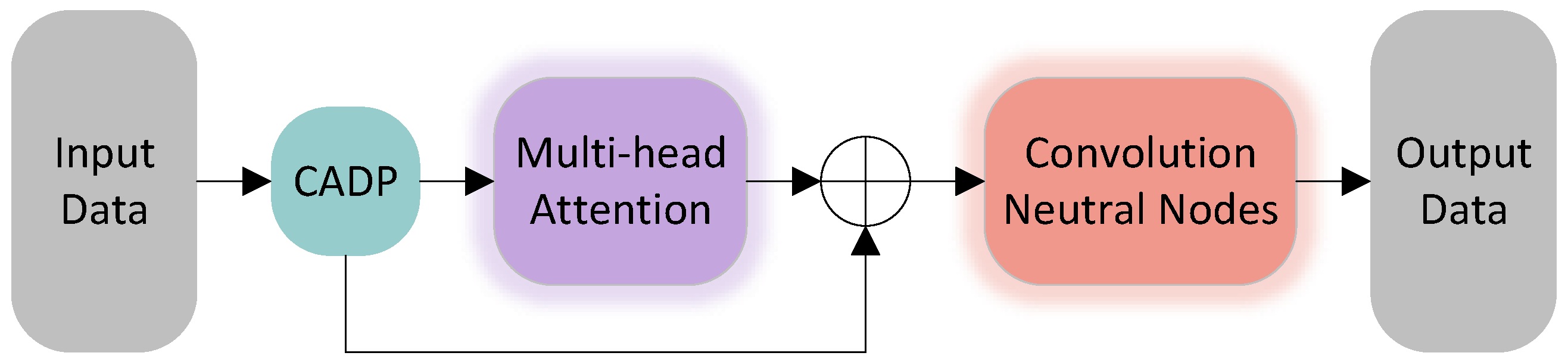

- We develop a PEM to estimate target motion patterns by fusing local and global spatial–temporal features. Considering that the state transition matrix characterizes motion dynamics and enables trajectory inference, we further introduce a PCLoss to help the PEM estimate the key turn rate parameter ().

2. Materials and Methods

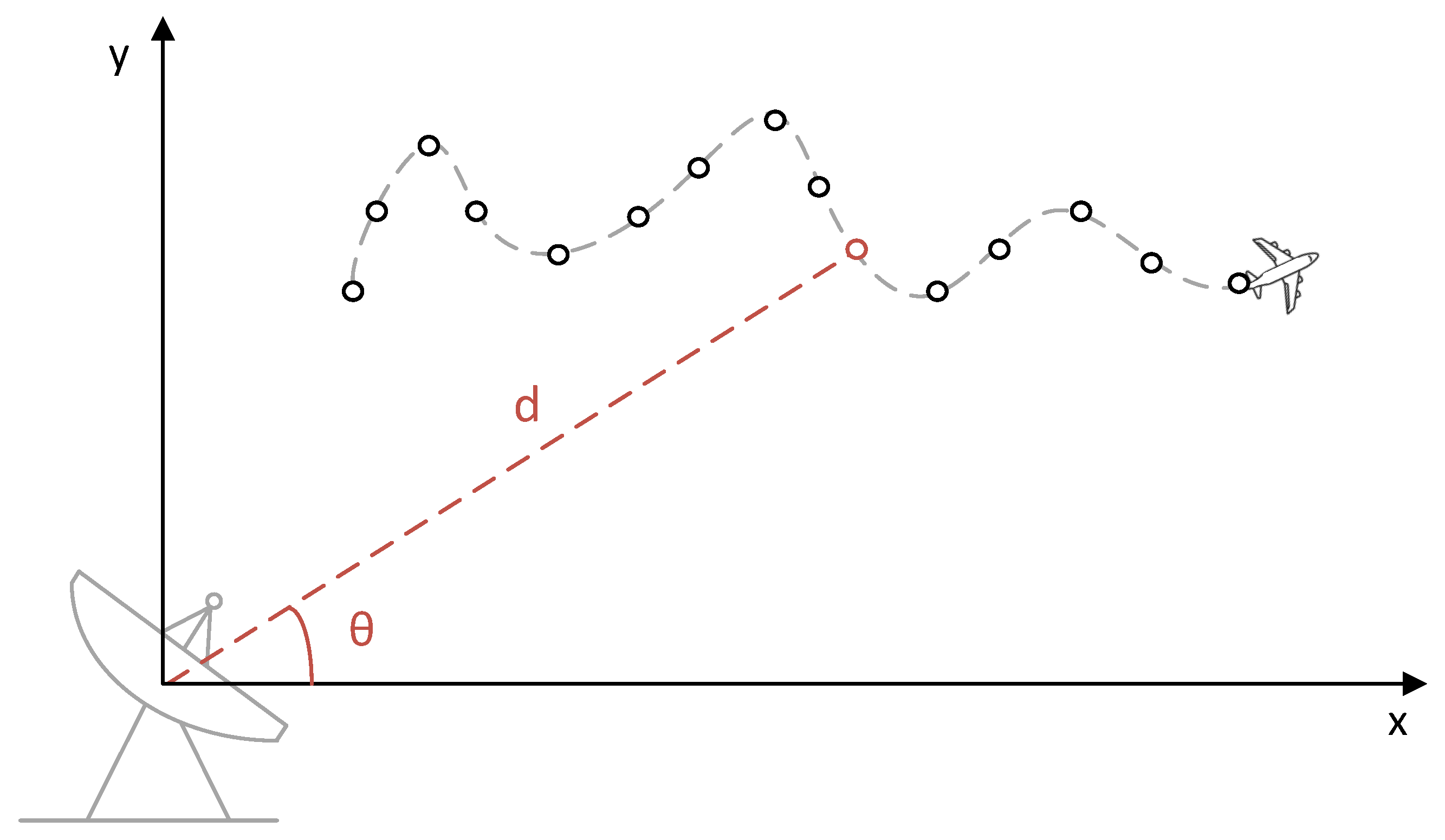

2.1. Problem Formulation

2.1.1. State Equation

2.1.2. Observation Equation

(1) The Radar Tracking System

(2) The Visual Remote Sensing Tracking System

2.1.3. Problem Addressed in This Work

2.2. Multi-Domain Intelligent State Estimation Network

2.2.1. Overall Architecture

| Algorithm 1 MIENet tracking process |

| Input: Noisy observations with N time steps. Output: Target states with N time steps.

|

2.2.2. Fusion Denoising Model

(1) Motivation

(2) The Overall Structure of FDM

(3) The Multi-Domain Feature Module

(a) The Inverted-UNet

(b) FFT-Based Weighting

2.2.3. Parameter Estimation Model

(1) Motivation

(2) The Overall Structure of PEM

(3) Physics-Constrained Loss Function

3. Results

3.1. Implementation Details

3.2. Comparison to the State-of-the-Art (SOTA)

3.2.1. Quantitative Results

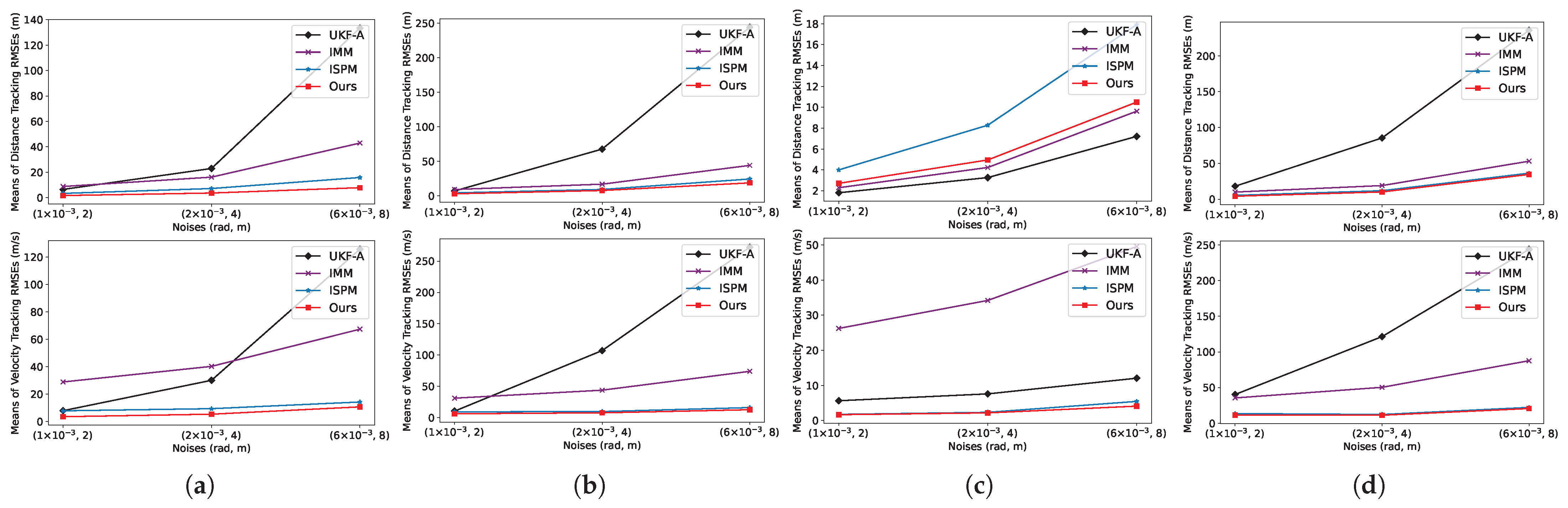

(1) The LAST Dataset

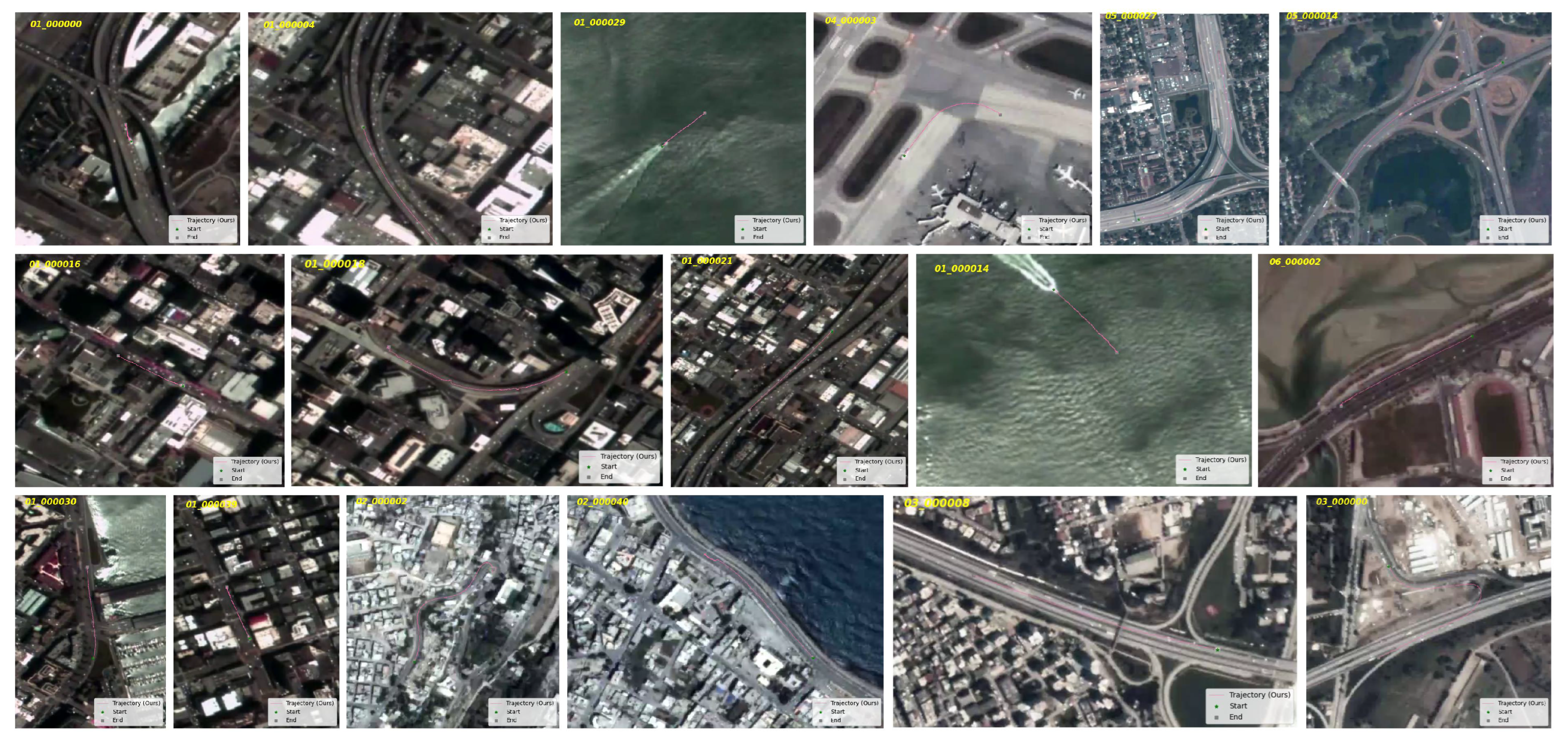

(2) The SV248S Dataset

3.2.2. Qualitative Results

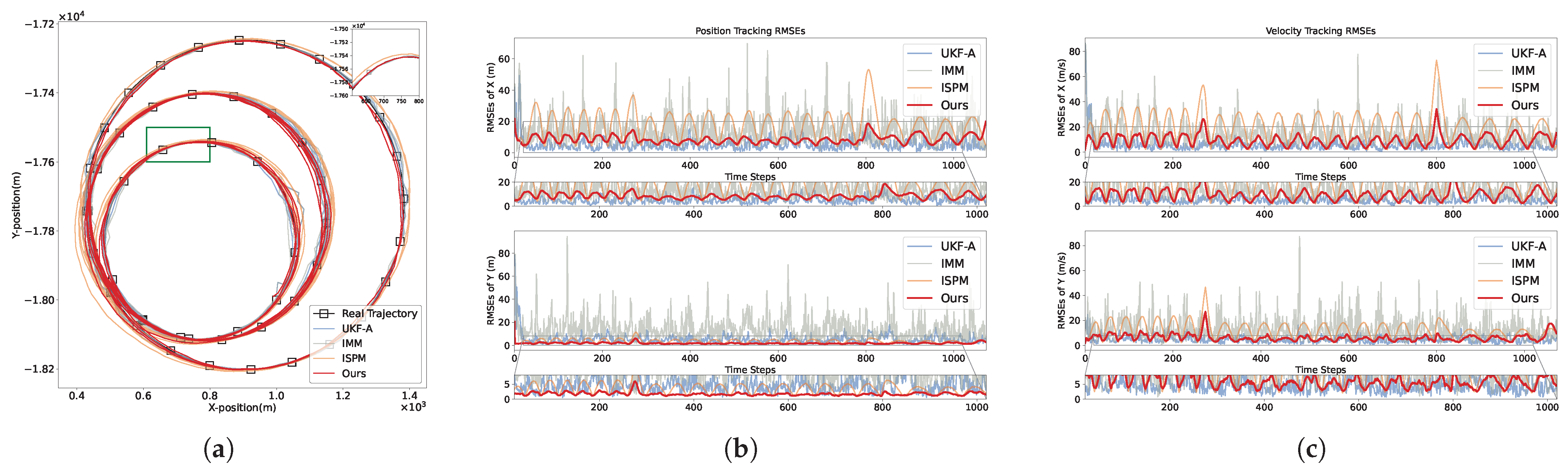

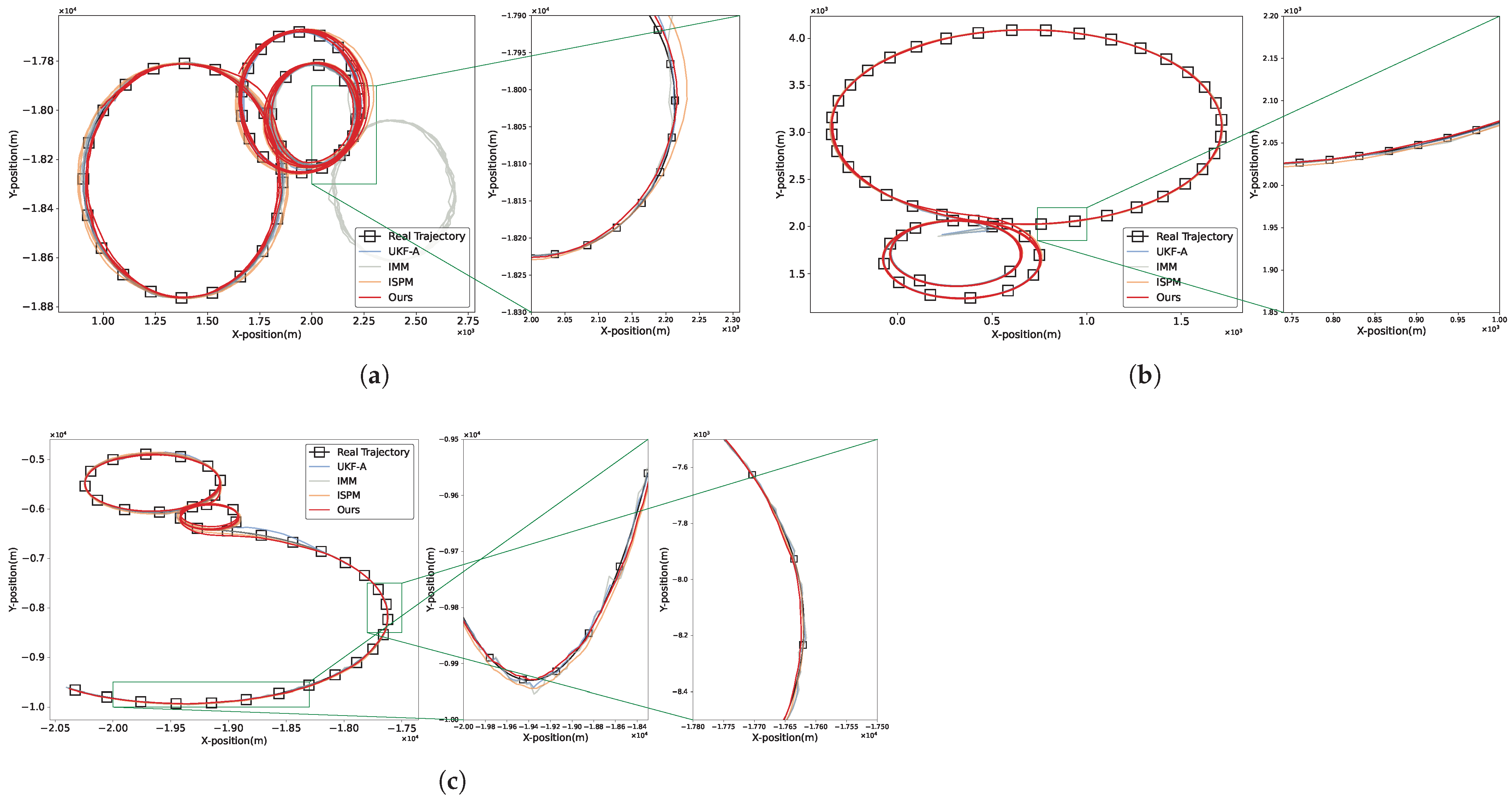

(1) The LAST Dataset

(2) The SV248S Dataset

3.3. Ablation Study

3.3.1. Ablation Study on the Magnitude and Distribution of Noise

3.3.2. Ablation Study on MDFM

- FDM w/o MDFM: As shown in Table 11, the original FDM achieves a 61.2% reduction in the RMSE, while removing the MDFM module decreases the reduction to 48.3%. The results are averaged over three noise intensity levels. This performance gap demonstrates that the Inverted-UNet is essential for denoising, as it extracts and fuses spatial-domain features more effectively from noisy observations.

- MIENet w/o MDFM: As shown in Table 12, our MIENet achieves position and velocity RMSEs of 7.78 m and 10.64 m/s, respectively. In Ablation 4, removing the MDFM module increases RMSEs to 15.83 m and 29.61 m/s. That is because the FDM, as a component of the MIENet, effectively suppresses noise and thereby contributes to its tracking performance.

3.3.3. Ablation Study on Multi-Head Attention

3.3.4. Ablation Study on Loss Function Design

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, Z.; Zhu, E.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, P.; Liu, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y. Predictive Autonomy for UAV Remote Sensing: A Survey of Video Prediction. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraternali, P.; Morandini, L.; Motta, R. Enhancing Search and Rescue Missions with UAV Thermal Video Tracking. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, D.; Ding, B.; Tong, X.; Sun, B.; Sun, X.; Guo, R.; Su, S. FSTC-DiMP: Advanced Feature Processing and Spatio-Temporal Consistency for Anti-UAV Tracking. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Tang, D.; Zhou, H.; Xiang, X. Moving Target Geolocation and Trajectory Prediction Using a Fixed-Wing UAV in Cluttered Environments. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Zhao, G.; Zhang, G.; Li, Z.; Ding, K. Visual detection and association tracking of dim small ship targets from optical image sequences of geostationary satellite using multispectral radiation characteristics. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Sun, H.; Wang, T. IAASNet: Ill-Posed-Aware Aggregated Stereo Matching Network for Cross-Orbit Optical Satellite Images. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Fu, G.; Yang, X.; Cao, X.; Niu, S.; Meng, Z. Two-Stage Spatio-Temporal Feature Correlation Network for Infrared Ground Target Tracking. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; He, W.; Deng, L.; Wu, Y.; Xie, H.; Dai, J. Trajectory tracking and load monitoring for moving vehicles on bridge based on axle position and dual camera vision. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q.; Chen, P.; Xu, G.; Sun, H.; Li, L.; Yu, G. Adaptive Path-Tracking Controller Embedded with Reinforcement Learning and Preview Model for Autonomous Driving. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2025, 74, 3736–3750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Liu, L.; Yu, Z. Towards Robust Visual Object Tracking for UAV with Multiple Response Incongruity Aberrance Repression Regularization. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2024, 31, 2005–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, Z.; Xu, M. DeepMTT: A deep learning maneuvering target-tracking algorithm based on bidirectional LSTM network. Inf. Fusion 2020, 53, 289–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yan, J.; Wan, D.; Li, X.; Al-Rubaye, S.; Al-Dulaimi, A.; Quan, Z. Digital Twins Based Intelligent State Prediction Method for Maneuvering-Target Tracking. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2023, 41, 3589–3606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, G.; Zhang, X.P.; He, Y. A deep learning model based on transformer structure for radar tracking of maneuvering targets. Inf. Fusion 2024, 103, 102120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.R.; Jilkov, V.P. Survey of maneuvering target tracking. Part I. Dynamic models. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2003, 39, 1333–1364. [Google Scholar]

- Kalman, R.E. A new approach to linear filtering and prediction problems. Trans. Asme-J. Basic Eng. 1960, 82, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, E.; Otero, D.; D’Attellis, C.E. Maneuvering target tracking using extended kalman filter. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 1991, 27, 155–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julier, S.; Uhlmann, J.; Durrant-Whyte, H.F. A new method for the nonlinear transformation of means and covariances in filters and estimators. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2000, 45, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, F.; Gunnarsson, F.; Bergman, N.; Forssell, U.; Jansson, J.; Karlsson, R.; Nordlund, P.J. Particle filters for positioning, navigation, and tracking. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2002, 50, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, H.A.; Bar-Shalom, Y. The interacting multiple model algorithm for systems with markovian switching coefficients. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 1988, 33, 780–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, H.; Zhao, W.; Wang, J. Interacting multiple model tracking algorithm fusing input estimation and best linear unbiased estimation filter. IET Radar Sonar Navig. 2017, 11, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yuan, B.; Miao, Z.; Wu, W. From GMM to HGMM: An approach in moving object detection. Comput. Inform. 2004, 23, 215–237. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Zang, C.; Wang, X.; Xiang, Y.; Cui, G. Data-Driven Intelligent Multi-Frame Joint Tracking Method for Maneuvering Targets in Clutter Environments. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2024, 61, 2679–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, Y.; Masouros, C.; You, X.; Ottersten, B. Hybrid Data-Induced Kalman Filtering Approach and Application in Beam Prediction and Tracking. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2024, 72, 1412–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhao, X.; Liu, Z.; Liu, K.; Chen, B. Converted state equation kalman filter for nonlinear maneuvering target tracking. Signal Process. 2022, 202, 108741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Davies, M.E.; Proudler, I.K.; Hopgood, J.R. Adaptive kernel kalman filter based belief propagation algorithm for maneuvering multi-target tracking. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2022, 29, 1452–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Mishra, K.V.; Chattopadhyay, A. Inverse Unscented Kalman Filter. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2024, 72, 2692–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, H.; Hu, J.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, Q. Variational nonlinear kalman filtering with unknown process noise covariance. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2023, 59, 9177–9190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Li, Z.; Luo, X.; Zhou, Z. Trajectory optimization of target motion based on interactive multiple model and covariance kalman filter. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Geoscience and Remote Sensing Mapping (GRSM), Lianyungang, China, 13–15 October 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Deepika, N.; Rajalakshmi, B.; Nijhawan, G.; Rana, A.; Yadav, D.K.; Jabbar, K.A. Signal processing for advanced driver assistance systems in autonomous vehicles. In Proceedings of the IEEE Uttar Pradesh Section International Conference on Electrical, Electronics and Computer Engineering (UPCON), Greater Noida, India, 1–3 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, S.; Rice, M.; Rice, F.; Wu, X. An expectation-maximization-based estimation algorithm for AOA target tracking with non-Gaussian measurement noises. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2022, 72, 498–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; He, J.; Wang, G.; Peng, B. A Maritime Multi-target Tracking Method with Non-Gaussian Measurement Noises based on Joint Probabilistic Data Association. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; He, J.; Peng, B.; Wang, G. Generalized interacting multiple model Kalman filtering algorithm for maneuvering target tracking under non-Gaussian noises. ISA Trans. 2024, 155, 148–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Wu, Z. Maximum correntropy quadrature Kalman filter based interacting multiple model approach for maneuvering target tracking. Signal Image Video Process. 2025, 19, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; Sun, L.; Wen, T.; Hei, X.; Qian, F. Adaptive transition probability matrix-based parallel IMM algorithm. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2019, 51, 2980–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Wang, S.; Qiu, M. Maneuvering target tracking based on LSTM for radar application. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Software Engineering and Artificial Intelligence (SEAI), Xiamen, China, 16–18 June 2023; pp. 235–239. [Google Scholar]

- Medsker, L.R.; Jain, L. Recurrent neural networks. Des. Appl. 2001, 5, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Graves, A.; Schmidhuber, J. Framewise phoneme classification with bidirectional LSTM and other neural network architectures. Neural Netw. 2005, 18, 602–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawakami, K. Supervised Sequence Labelling with Recurrent Neural Networks. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, G.; Zhang, X.P.; He, Y. Transformer-based tracking network for maneuvering targets. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2023-2023 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Rhodes Island, Greece, 4–10 June 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, L.; Su, H.; Li, Z.; Jia, C.; Yang, R. Self-attention-based Transformer for nonlinear maneuvering target tracking. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Sun, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X. Physics-Informed Data-Driven Autoregressive Nonlinear Filter. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2025, 32, 846–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revach, G.; Shlezinger, N.; Ni, X.; Escoriza, A.L.; Van Sloun, R.J.; Eldar, Y.C. KalmanNet: Neural network aided Kalman filtering for partially known dynamics. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2022, 70, 1532–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, G.; Park, J.; Shlezinger, N.; Eldar, Y.C.; Lee, N. Split-KalmanNet: A robust model-based deep learning approach for state estimation. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 72, 12326–12331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchnik, I.; Revach, G.; Steger, D.; Van Sloun, R.J.; Routtenberg, T.; Shlezinger, N. Latent-KalmanNet: Learned Kalman filtering for tracking from high-dimensional signals. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2024, 72, 352–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, M.; Shafieezadeh, A. Cholesky-KalmanNet: Model-Based Deep Learning with Positive Definite Error Covariance Structure. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2024, 32, 326–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Lu, K.; Sun, C. Deep Learning Aided State Estimation for Guarded Semi-Markov Switching Systems with Soft Constraints. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2023, 71, 3100–3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, R.; Lan, J.; Cao, X. Nonlinear Estimation Using Multiple Conversions with Optimized Extension for Target Tracking. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2023, 71, 4457–4470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortada, H.; Falcon, C.; Kahil, Y.; Clavaud, M.; Michel, J.P. Recursive KalmanNet: Deep Learning-Augmented Kalman Filtering for State Estimation with Consistent Uncertainty Quantification. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.11639. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Li, Y. Normalizing Flow-Based Differentiable Particle Filters. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2024, 73, 493–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Ma, J.; Kouw, W.M. Multiple Variational Kalman-GRU for Ship Trajectory Prediction with Uncertainty. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2024, 61, 3654–3667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Li, W.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Yang, J.; Yu, X.; Guo, L. KFDNNs-Based Intelligent INS/PS Integrated Navigation Method Without Statistical Knowledge. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 26, 12197–12209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y. AKansformer: Axial Kansformer–Based UUV Noncooperative Target Tracking Approach. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2025, 21, 4883–4891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Chen, J.; Yu, G.; Zhai, Z.; Han, P. KalmanFormer: Using transformer to model the Kalman Gain in Kalman Filters. Front. Neurorobot. 2025, 18, 1460255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Zheng, Y.; Lin, D.; Cai, P.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, S. MAML-KalmanNet: A neural network-assisted Kalman filter based on model-agnostic meta-learning. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2025, 73, 988–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuri, I.; Shlezinger, N. Learning Flock: Enhancing Sets of Particles for Multi Sub-State Particle Filtering with Neural Augmentation. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2024, 73, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, W.; Zhang, L.; Meng, Y.; Han, W.; Song, T.; Yang, R. An allocation strategy integrating power, bandwidth, and subchannel in an RCC network. Def. Technol. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, B. Joint Customer Assignment, Power Allocation, and Subchannel Allocation in a UAV-Based Joint Radar and Communication Network. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 29643–29660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Xiong, W.; Cui, Y. An adaptive interactive multiple-model algorithm based on end-to-end learning. Chin. J. Electron. 2023, 32, 1120–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Jiao, L.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, R.; Song, X.; Tian, C.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, F.; Yang, S.; et al. Deep learning-based object tracking in satellite videos: A comprehensive survey with a new dataset. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2022, 10, 181–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.M.; Liu, T.J.; Liu, K.H. SUNet: Swin transformer UNet for image denoising. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), Austin, TX, USA, 27 May–1 June 2022; pp. 2333–2337. [Google Scholar]

- Vafa, K.; Chang, P.G.; Rambachan, A.; Mullainathan, S. What has a foundation model found? using inductive bias to probe for world models. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 13–19 July 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Holleman, E.C. Flight Investigation of the Roll Requirements for Transport Airplanes in Cruising Flight; Technical Report; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 1970.

- Chen, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Xiao, Y.; Tang, Y.; He, J.; Han, T. STAR: A Unified Spatiotemporal Fusion Framework for Satellite Video Object Tracking. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Marelli, D.; Xu, Y.; Fu, M. Distributed target tracking using maximum likelihood Kalman filter with non-linear measurements. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 27818–27826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dim 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Dim 2 | 29 | 29 | 58 | 29 | 116 | 203 | 29 | 174 | 522 | 812 | 29 |

| Dim 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Dim 4 | 6 | 12 | 6 | 24 | 12 | 6 | 48 | 24 | 12 | 6 | 6 |

| Contents | Ranges |

|---|---|

| Initial distance from radar | [1 km, 10 km] |

| Initial velocity of targets | [100, 200 m/s] |

| Initial distance azimuth | [−180°, 180°] |

| Initial velocity azimuth | [−180°, 180°] |

| Maneuvering turn rate | [−90°/s, 90°/s] |

| Variance of accelerated velocity noise | 10 (m/s)2 |

| Trajectories | Initial State | The First Part | The Second Part | The Third Part |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | [1000 m, −18,000 m, 150 m/s, 200 m/s] | 27.4 s, = 50°/s | 52.6 s, = 40°/s | 27.4 s, = 30°/s |

| 2 | [1000 m, −18,000 m, 150 m/s, 200 m/s] | 40 s, = −30°/s | 27.4 s, = 70°/s | 40 s, = 50°/s |

| 3 | [500 m, 2000 m, −300 m/s, 200 m/s] | 25 s, = 60°/s | 42.4 s, = 50°/s | 40 s, = −20°/s |

| 4 | [−20,000 m, −5000 m, 250 m/s, 180 m/s] | 30 s, = −30°/s | 17.4 s, = 70°/s | 20.9 s, = −10°/s |

| Trajectories p (m)/v (m/s) | Noise Standard Deviation (Azimuth, Range) | UKF-A [64] | IMM [19] | ISPM [12] | MIENet (Ours) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (1 × 10−3 rad, 2 m) | Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 | 6.667/11.38 6.329/7.463 6.457/7.963 | 9.193/32.57 8.689/28.72 8.366/25.87 | 3.770/7.920 3.370/8.030 2.490/7.040 | 1.800/4.170 1.500/3.100 1.350/3.100 |

| All | 6.420/7.860 | 8.720/28.84 | 3.280 /7.770 | 1.580/3.470 | ||

| (2 × 10−3 rad, 4 m) | Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 | 39.73/64.94 13.23/13.67 10.86/10.17 | 17.01/47.30 15.92/39.23 15.52/36.66 | 7.950/9.570 7.360/9.630 5.500/8.410 | 4.650/6.150 2.650/4.380 3.310/4.870 | |

| All | 22.90/30.05 | 16.07/40.23 | 7.110/9.330 | 3.570/5.300 | ||

| (6 × 10−3 rad, 8 m) | Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 | 139.2/208.9 136.4/124.3 132.7/109.7 | 62.80/147.8 41.62/63.69 40.46/60.04 | 17.80/13.59 15.88/14.67 13.26/13.83 | 9.170/10.15 7.250/12.20 4.520/8.590 | |

| All | 133.5/125.8 | 42.90/67.37 | 15.80/14.21 | 7.780/10.64 | ||

| 2 | (1 × 10−3 rad, 2 m) | Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 | 6.854/8.294 10.10/26.66 6.494/8.489 | 9.481/33.15 8.692/29.30 9.013/30.38 | 2.640/7.170 5.560/12.70 4.350/8.570 | 1.790/4.930 3.340/9.200 3.870/7.260 |

| All | 6.920/10.36 | 9.090/31.10 | 4.170/9.290 | 2.840/6.190 | ||

| (2 × 10−3 rad, 4 m) | Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 | 12.04/12.22 94.06/172.2 83.27/118.6 | 17.95/45.88 15.82/44.09 16.33/42.03 | 5.600/8.870 11.74/10.53 9.970/10.07 | 3.440/6.190 10.06/9.740 11.53/10.58 | |

| All | 67.66/107.1 | 16.78/43.87 | 9.110/9.750 | 7.600/7.690 | ||

| (6 × 10−3 rad, 8 m) | Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 | 121.2/127.0 223.4/293.5 275.9/301.5 | 54.83/96.77 39.80/76.48 41.08/67.76 | 11.62/11.72 28.47/17.84 35.27/20.49 | 6.540/7.930 17.26/15.48 32.28/17.27 | |

| All | 244.4/272.4 | 44.05/73.98 | 24.30/16.07 | 18.65/12.64 | ||

| 3 | (1 × 10−3 rad, 2 m) | Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 | 1.651/5.706 1.561/5.125 2.214/6.587 | 2.106/24.70 2.010/25.08 2.723/28.50 | 5.030/1.810 4.590/1.650 2.320/1.870 | 3.300/1.920 2.590/1.550 3.120/1.760 |

| All | 1.810/5.640 | 2.290/26.23 | 4.000/1.770 | 2.710/1.670 | ||

| (2 × 10−3 rad, 4 m) | Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 | 2.953/8.071 2.758/6.747 4.097/9.735 | 3.882/32.96 3.730/32.38 5.018/36.97 | 10.31/2.440 9.540/2.150 4.760/2.470 | 6.400/2.670 5.690/2.270 4.090/1.770 | |

| All | 3.260/7.590 | 4.230/34.19 | 8.280/2.340 | 4.950/2.180 | ||

| (6 × 10−3 rad, 8 m) | Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 | 6.277/14.22 5.747/10.03 9.921/18.34 | 8.626/50.51 8.169/46.74 11.79/52.27 | 22.15/5.630 21.03/3.200 9.160/7.020 | 14.98/5.070 10.43/4.040 8.120/3.980 | |

| All | 7.210/12.06 | 9.620/49.53 | 17.92/5.450 | 10.49/4.100 | ||

| 4 | (1 × 10−3 rad, 2 m) | Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 | 8.420/16.20 15.38/43.98 42.29/77.72 | 10.47/39.53 9.549/33.30 9.838/31.73 | 3.530/9.050 8.440/19.11 4.650/13.54 | 3.650/9.910 6.380/17.36 1.300/3.490 |

| All | 18.13/40.22 | 10.01/35.40 | 5.430/13.49 | 4.180/11.38 | ||

| (2 × 10−3 rad, 4 m) | Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 | 28.23/43.75 99.56/175.2 114.5/124.9 | 20.41/55.48 17.93/50.32 18.37/44.73 | 7.150/11.13 18.42/13.35 10.81/12.76 | 8.440/6.140 16.01/18.94 2.370/6.230 | |

| All | 85.48/121.5 | 19.06/50.31 | 11.89/12.21 | 10.16/11.14 | ||

| (6 × 10−3 rad, 8 m) | Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 | 159.9/195.7 301.7/361.7 207.8/114.6 | 72.75/154.2 43.35/85.78 49.05/72.03 | 25.64/14.89 53.94/31.10 34.12/23.23 | 24.62/9.770 57.04/33.48 12.61/16.75 | |

| All | 235.5/244.0 | 53.04/87.63 | 36.33/22.10 | 34.57/20.50 |

| Trajectories | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Time Steps | 1074 | 1074 | 1074 | 683 |

| Allocated GPU Memory (MB) | 8.05 | 8.36 | 7.99 | 8.07 |

| Active GPU Memory (MB) | 1316 | |||

| FLOPs (MB) | FDM: 10 PEM: 0.02 | |||

| # Params (MB) | FDM: 1239 PEM: 14.7 | |||

| Trackers | Category-Wise Evaluations | Difficulty-Wise Evaluations | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle | L-Vehicle | Airplane | Ship | Simple | Normal | Hard | ||||||||

| PR | SR | PR | SR | PR | SR | PR | SR | PR | SR | PR | SR | PR | SR | |

| STAR [63] | 0.7542 | 0.4911 | 0.8739 | 0.6555 | 0.8399 | 0.7517 | 1.0000 | 0.7562 | 0.8800 | 0.6228 | 0.7138 | 0.4653 | 0.6652 | 0.4177 |

| Ours | 0.7550 | 0.4944 | 0.8744 | 0.6598 | 0.8399 | 0.7530 | 1.0000 | 0.7611 | 0.8816 | 0.6278 | 0.7138 | 0.4675 | 0.6760 | 0.4440 |

| Trackers | STO | LTO | DS | IV | BCH | SM | ND | CO | BCL | IPR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STAR [63] | 0.676/0.444 | 0.472/0.301 | 0.731/0.489 | 0.692/0.446 | 0.796/0.534 | 0.700/ 0.462 | 0.752/0.489 | 0.700/0.444 | 0.730/0.458 | 0.697/0.464 |

| Ours | 0.676/0.447 | 0.473/0.302 | 0.731/0.492 | 0.693/0.449 | 0.797/0.538 | 0.700/0.461 | 0.753/0.490 | 0.700/0.447 | 0.730/0.460 | 0.697/0.466 |

| Scenes | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Time Steps | 750 | 747 | 490 | 748 | 580 | 499 |

| Allocated GPU memory (MB) | 5.47 | |||||

| Active GPU Memory (MB) | 1310 | |||||

| FLOPs (MB) | FDM: 10 PEM: 0.02 | |||||

| # Params (MB) | FDM: 1239 PEM: 14.7 | |||||

| Methods RMSE (m) | Gaussian-Injected Noise (10−3 rad, m) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| (2, 4) | (8, 10) | (11, 13) | |

| Original Observation | 35.310 | 140.94 | 193.77 |

| Butterworth Filter | 28.000 | 112.09 | 153.65 |

| ISPM-NEN [12] | 17.359 | 61.978 | 84.804 |

| FDM (ours) | 13.593 (↓61.5%) | 43.690 (↓69.0%) | 61.135 (↓68.4%) |

| Methods RMSE (m) | Uniform-Injected Noise (10−3 rad, m) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| (12, 21.3) | (40.3, 56.3) | (75, 133.3) | |

| Original Observation | 61.536 | 112.78 | 153.84 |

| Butterworth Filter | 47.836 | 87.673 | 119.59 |

| ISPM-NEN [12] | 28.994 | 52.348 | 71.290 |

| FDM (ours) | 23.295 (↓62.1%) | 40.333 (↓64.2%) | 54.277 (↓64.7%) |

| Methods RMSE (m) | Noise | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (2 × 10−3 rad, 4 m) | (8 × 10−3 rad, 10 m) | (11 × 10−3 rad, 13 m) | |||

| FDM w/o MDFM | pos (m) | Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 | 15.53 16.34 15.69 | 49.34 42.67 44.04 | 74.20 58.67 62.43 |

| All | 15.97 (↓36.3%) | 44.81 (↓55.2%) | 63.91 (↓53.5%) | ||

| Ours | pos (m) | Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 | 11.63 10.25 9.960 | 39.28 33.58 38.76 | 55.11 46.97 57.77 |

| All | 10.55 (↓57.9%) | 36.45 (↓63.5%) | 52.02 (↓62.1%) | ||

| Tracking Variations | MDFM | MHN | PCLoss | Distance (m)/ Velocity (m/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ablation 1 | ✓ | 25.88/21.61 | ||

| Ablation 2 | ✓ | 19.39/28.87 | ||

| Ablation 3 | ✓ | 33.29/38.21 | ||

| Ablation 4 | ✓ | ✓ | 15.83/29.61 | |

| Ablation 5 | ✓ | ✓ | 16.90/14.07 | |

| Ablation 6 | ✓ | ✓ | 9.900/13.55 | |

| Ours | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 7.780/10.64 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, Z.; Wang, X.; Huang, Y.; Xu, Q.; An, W.; Sheng, W. Multi-Domain Intelligent State Estimation Network for Highly Maneuvering Target Tracking with Non-Gaussian Noise. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 4016. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244016

Ma Z, Wang X, Huang Y, Xu Q, An W, Sheng W. Multi-Domain Intelligent State Estimation Network for Highly Maneuvering Target Tracking with Non-Gaussian Noise. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):4016. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244016

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Zhenzhen, Xueying Wang, Yuan Huang, Qingyu Xu, Wei An, and Weidong Sheng. 2025. "Multi-Domain Intelligent State Estimation Network for Highly Maneuvering Target Tracking with Non-Gaussian Noise" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 4016. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244016

APA StyleMa, Z., Wang, X., Huang, Y., Xu, Q., An, W., & Sheng, W. (2025). Multi-Domain Intelligent State Estimation Network for Highly Maneuvering Target Tracking with Non-Gaussian Noise. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 4016. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244016