Towards a Global Water Use Scarcity Risk Assessment Framework: Integration of Remote Sensing and Geospatial Datasets

Highlights

- Ensemble machine learning was employed to generate multi-year global terrestrial water storage and water withdrawal by integrating remote sensing and geospatial datasets.

- Big data and IPCC exposure-hazard-vulnerability paradigm were used to assess variation and evolution of global water scarcity risk over the past two decades.

- Largest TWS losses and highest risk cluster in Asia and Africa imply that policy should prioritize storage buffering, withdrawal management and capacity building to curb widening water-security inequities.

- A storage-aware remote sensing-driven EHV framework offers a consistent basis for global risk mapping, supporting operational early warning and transboundary planning while reducing dependence on model-only proxies.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Remote Sensing-Derived TWS

2.2. Water Withdrawal Based on Geospatial Dataset, Remote Sensing and Machine Learning

2.3. Risk Assessment Framework

2.3.1. Exposure Calculation

2.3.2. Hazard Calculation

2.3.3. Vulnerability Calculation

2.4. Analysis Framework

3. Results

3.1. Accuracy of Reconstructed Dataset

3.2. TWS Dynamic over Past Two Decades

3.3. Human Water Withdrawal over Past Two Decades

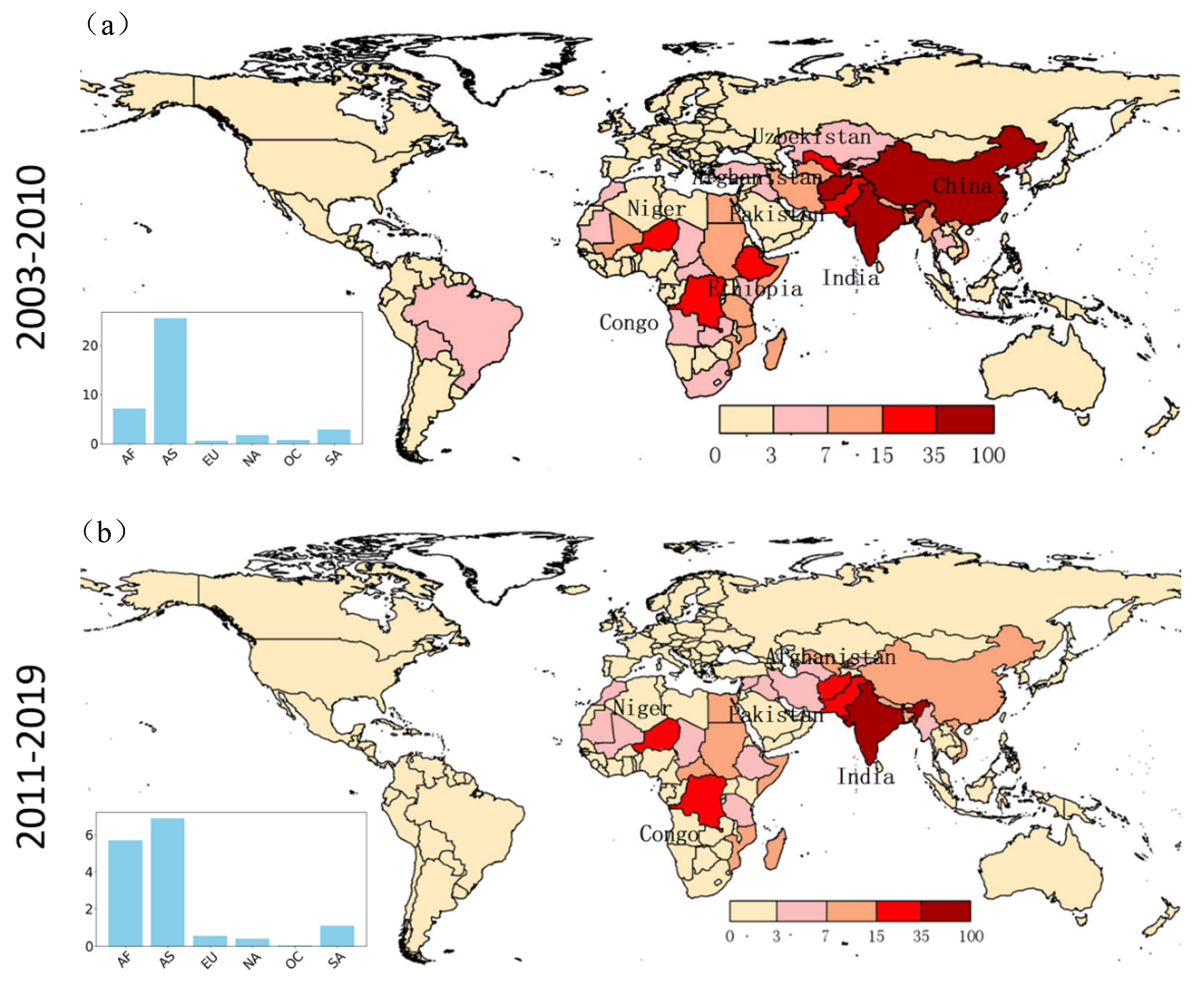

3.4. Water Scarcity Assessment

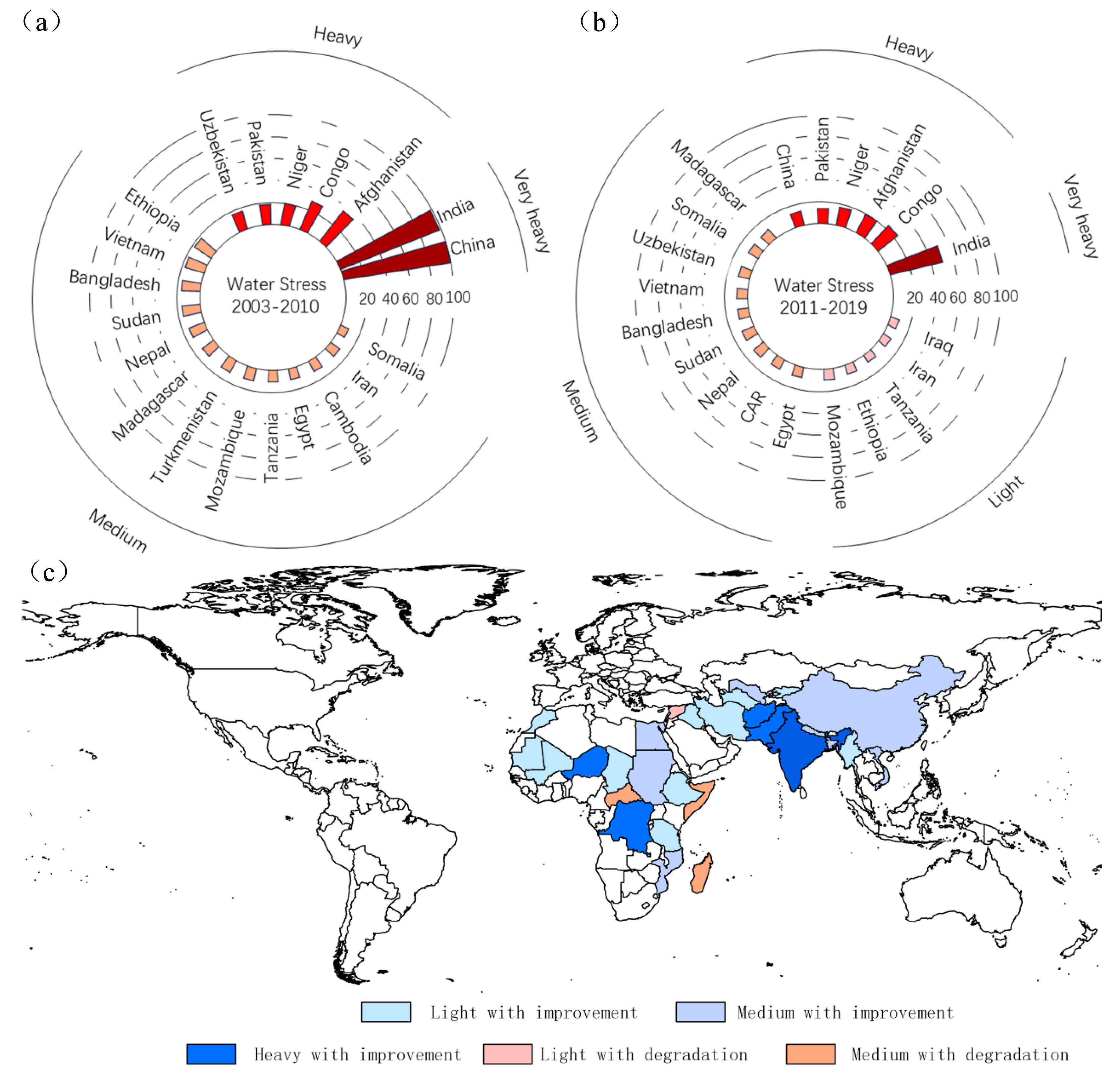

3.5. Evolution of Water Scarcity

3.6. Socio-Economic Drivers of Water Scarcity

4. Discussion

4.1. Advancing Beyond Existing Approaches

4.2. Inequality and Implication in Water Resource Management

4.3. Uncertainty Analysis and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TWS | Terrestrial water storage |

| EHV | Exposure-Hazard-Vulnerability |

| GRACE | the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment |

| GRACE-FO | GRACE Follow-On |

| TWSA | TWS anomaly |

| CSR | the Center for Space Research |

| STL | Seasonal and Trend decomposition with Loess |

| ECMWF | European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts |

| GLEAM | the Global Land Evaporation Amsterdam Model |

| GIA | Glacial Isostatic Adjustment |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| MAE | Mean absolute error |

| WS | Water stress |

| scPDSI | Self-calibrated Palmer Drought Severity Index |

| GE | the Government effectiveness indicator |

| HDI | Human Development Index |

| WFA | Water Footprint Assessment |

Appendix A

| Variable | Definition | Calculation Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Water stress (WS) | Potential consequences for water resource risk in each region, driven by the interplay of hazard, vulnerability, and exposure. | |

| Water withdrawal | Volume of water extracted from sources such as rivers, lakes, and groundwater. | |

| Self-calibrated Palmer Drought Severity Index (scPDSI) | Indicator used to measure the severity of drought, calculated by meteorological data and soil moisture. | |

| Government Effectiveness (GE) | Index used to evaluate the capacity of governments to deliver public services, formulate effective policies, and enforce laws. | |

| terrestrial water storage anomalies (TWSA) | Deviation of terrestrial water storage components (such as soil water, groundwater, lake water, and reservoir water) from multi-year average. | |

| GDP per capita (GDPpc) | Gross Domestic Product (GDP) within a country or region, by dividing the total population. | |

| Human Development Index (HDI) | Composite index introduced by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) to measure the overall human development level of a country or region, incorporating education, income, and life expectancy. | |

| Exposure (E) | Total water requirements of vegetation and agriculture within a region, directly influencing water resource allocation. | |

| Hazard (H) | Combined impact of drought intensity and governance quality, highlighting regions most at risk from natural disasters. | |

| Vulnerability (V) | Capacity to withstand and adapt to water scarcity challenges, influenced by the Human Development Index, water storage, and GDP per capita. |

References

- Wheeler, T.; von Braun, J. Climate Change Impacts on Global Food Security. Science 2013, 341, 508–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Zhang, X. Unrevealing past and future vegetation restoration on the Loess Plateau and its impact on terrestrial water storage. J. Hydrol. 2023, 617, 129021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Mann, M.E.; Wehner, M.F.; Christiansen, S. Increased frequency of planetary wave resonance events over the past half-century. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2504482122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, A. Drought under global warming: A review. WIREs Clim. Chang. 2011, 2, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Tang, B.; Shen, D.; Yin, G.; Li, Y.; Chen, X.; Hu, Z.; Habib Nazrollozoda, S. Future challenges of terrestrial water storage over the arid regions of Central Asia. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf 2024, 132, 104026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosling, S.N.; Arnell, N.W. A global assessment of the impact of climate change on water scarcity. Clim. Chang. 2016, 134, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yang, H.; Gosling, S.N.; Kummu, M.; Flörke, M.; Pfister, S.; Hanasaki, N.; Wada, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, C.; et al. Water scarcity assessments in the past, present, and future. Earth’s Future 2017, 5, 545–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; He, B.; Guo, L.; Liu, J.; Xie, X. The relative contributions of precipitation, evapotranspiration, and runoff to terrestrial water storage changes across 168 river basins. J. Hydrol. 2019, 579, 124194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoff, H. Global water resources and their management. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2009, 1, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masih, I.; Uhlenbrook, S.; Maskey, S.; Ahmad, M.D. Regionalization of a conceptual rainfall–runoff model based on similarity of the flow duration curve: A case study from the semi-arid Karkheh basin, Iran. J. Hydrol. 2010, 391, 188–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posada-Marín, J.; Salazar, J.; Rulli, M.C.; Wang-Erlandsson, L.; Jaramillo, F. Upwind moisture supply increases risk to water security. Nat. Water 2024, 2, 875–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Mueller, N.D.; Siebert, S.; Jackson, R.B.; AghaKouchak, A.; Zimmerman, J.B.; Tong, D.; Hong, C.; Davis, S.J. Flexibility and intensity of global water use. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swami, D.; Parthasarathy, D. Dynamics of exposure, sensitivity, adaptive capacity and agricultural vulnerability at district scale for Maharashtra, India. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 121, 107206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, J. Future global socioeconomic risk to droughts based on estimates of hazard, exposure, and vulnerability in a changing climate. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 751, 142159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, C.; Chiew, F.H.S.; Post, D.A.; Zhang, X.; Ma, N.; Tian, J.; Kong, D.; Leung, L.R.; Yu, Q.; et al. Southern Hemisphere dominates recent decline in global water availability. Science 2023, 382, 579–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Jia, L.; Menenti, M.; Zheng, C.; Hu, G.; Ji, D. The impacts of drought on water availability: Spatial and temporal analysis in the Belt and Road region (2001–2020). Int. J. Digit. Earth 2025, 18, 2449706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Lian, X.; Huntingford, C.; Gimeno, L.; Wang, T.; Ding, J.; He, M.; Xu, H.; Chen, A.; Gentine, P.; et al. Global water availability boosted by vegetation-driven changes in atmospheric moisture transport. Nat. Geosci. 2022, 15, 982–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, D.; Yang, W.; Scanlon, B.R.; Zhao, J.; Liu, D.; Burek, P.; Pan, Y.; You, L.; Wada, Y. South-to-North Water Diversion stabilizing Beijing’s groundwater levels. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Li, X.; Long, X. Trends in groundwater changes driven by precipitation and anthropogenic activities on the southeast side of the Hu Line. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 094032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugonnet, R.; McNabb, R.; Berthier, E.; Menounos, B.; Nuth, C.; Girod, L.; Farinotti, D.; Huss, M.; Dussaillant, I.; Brun, F.; et al. Accelerated global glacier mass loss in the early twenty-first century. Nature 2021, 592, 726–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; You, W.; Tian, S.; Jiang, Z.; Wan, X. A Two-Step Linear Model to Fill the Data Gap Between GRACE and GRACE-FO Terrestrial Water Storage Anomalies. Water Resour. Res. 2023, 59, e2022WR034139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, Y. Filling GRACE data gap using an innovative transformer-based deep learning approach. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 315, 114465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Bo, Y.; Yao, X.; Chen, G.; Liu, K.; Wang, S.; Yang, B.; Li, X. A Deep Learning Framework for Long-Term Soil Moisture-Based Drought Assessment Across the Major Basins in China. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, K.; Wang, S.; Li, D.; Xu, Y.; Wang, M. Hybrid Theory-Guided Data Driven Framework for Calculating Irrigation Water Use of Three Staple Cereal Crops in China. Water Resour. Res. 2024, 60, e2023WR035234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Ding, F.; Liu, L.; Yin, F.; Hao, M.; Kang, T.; Zhao, C.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, D. Monitoring water quality parameters in urban rivers using multi-source data and machine learning approach. J. Hydrol. 2025, 648, 132394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, K.; Yang, B.; Wang, S.; Meng, Y.; Wang, D.; Liu, X.; Li, L.; Li, D.; Bo, Y.; et al. Continuous monitoring of grassland AGB during the growing season through integrated remote sensing: A hybrid inversion framework. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2024, 17, 2329817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Lu, S.; Bo, Y.; Zhou, G. Quantifying Past and Future Terrestrial Water Storage Scarcity Across China Through Midcentury. Earth’s Future 2025, 13, e2025EF006071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Li, X.; Wang, S. Assessing reclamation potential of abandoned drylands using knowledge-guided machine learning (KGML) and remote sensing. Water Res. 2025, 288, 124623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, Y.; Wisser, D.; Bierkens, M.F.P. Global modeling of withdrawal, allocation and consumptive use of surface water and groundwater resources. Earth Syst. Dynam. 2014, 5, 15–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Save, H.; Bettadpur, S.; Tapley, B.D. High-resolution CSR GRACE RL05 mascons. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2016, 121, 7547–7569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Kusche, J.; Chao, N.; Wang, Z.; Löcher, A. Long-Term (1979-Present) Total Water Storage Anomalies Over the Global Land Derived by Reconstructing GRACE Data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, e2021GL093492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Long, D.; Yang, W.; Li, X.; Pan, Y. Reconstruction of GRACE Data on Changes in Total Water Storage Over the Global Land Surface and 60 Basins. Water Resour. Res. 2020, 56, e2019WR026250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, C.; Chiew, F.H.S.; Tian, J.; Ma, N.; Zhang, X. Can Indirect Evaluation Methods and Their Fusion Products Reduce Uncertainty in Actual Evapotranspiration Estimates? Water Resour. Res. 2022, 58, e2021WR031069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Liu, S.; Mo, X.; Jiang, L.; Bauer-Gottwein, P. Polar Drift in the 1990s Explained by Terrestrial Water Storage Changes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, e2020GL092114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller Schmied, H.; Cáceres, D.; Eisner, S.; Flörke, M.; Herbert, C.; Niemann, C.; Peiris, T.A.; Popat, E.; Portmann, F.T.; Reinecke, R.; et al. The global water resources and use model WaterGAP v2.2d: Model description and evaluation. Geosci. Model Dev. 2021, 14, 1037–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebert, S.; Döll, P.; Hoogeveen, J.; Faures, J.M.; Frenken, K.; Feick, S. Development and validation of the global map of irrigation areas. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2005, 9, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuke, A.; Rinke, P.; Todorović, M. Efficient hyperparameter tuning for kernel ridge regression with Bayesian optimization. Mach. Learn. Sci. Technol. 2021, 2, 035022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Zhang, H. A robust gap-filling approach for European Space Agency Climate Change Initiative (ESA CCI) soil moisture integrating satellite observations, model-driven knowledge, and spatiotemporal machine learning. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2023, 27, 577–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Schrier, G.; Barichivich, J.; Briffa, K.R.; Jones, P.D. A scPDSI-based global data set of dry and wet spells for 1901–2009. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2013, 118, 4025–4048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, D.; Kraay, A. Governance Indicators: Where Are We, Where Should We Be Going? World Bank Res. Obs. 2008, 23, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, B.L.; Kasperson, R.E.; Matson, P.A.; McCarthy, J.J.; Corell, R.W.; Christensen, L.; Eckley, N.; Kasperson, J.X.; Luers, A.; Martello, M.L.; et al. A framework for vulnerability analysis in sustainability science. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 8074–8079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trautmann, T.; Koirala, S.; Carvalhais, N.; Güntner, A.; Jung, M. The importance of vegetation in understanding terrestrial water storage variations. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2022, 26, 1089–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Slater, L.J.; Khouakhi, A.; Yu, L.; Liu, P.; Li, F.; Pokhrel, Y.; Gentine, P. GTWS-MLrec: Global terrestrial water storage reconstruction by machine learning from 1940 to present. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2023, 15, 5597–5615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kummu, M.; Taka, M.; Guillaume, J.H.A. Gridded global datasets for Gross Domestic Product and Human Development Index over 1990–2015. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 180004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Zhou, G. Past and future adverse response of terrestrial water storages to increased vegetation growth in drylands. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2023, 6, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, D.; Pan, Y.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Y.; Hou, X.; Hong, Y.; Scanlon, B.R.; Longuevergne, L. Global analysis of spatiotemporal variability in merged total water storage changes using multiple GRACE products and global hydrological models. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 192, 198–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Long, D.; Scanlon, B.R.; Mann, M.E.; Li, X.; Tian, F.; Sun, Z.; Wang, G. Climate change threatens terrestrial water storage over the Tibetan Plateau. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2022, 12, 801–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Mann, M.E.; Wehner, M.F.; Rahmstorf, S.; Petri, S.; Christiansen, S.; Carrillo, J. Role of atmospheric resonance and land–atmosphere feedbacks as a precursor to the June 2021 Pacific Northwest Heat Dome event. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2315330121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.S. Water, Agriculture and Food: Challenges and Issues. Water Resour. Manag. 2017, 31, 2985–2999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Hejazi, M.; Li, X.; Tang, Q.; Vernon, C.; Leng, G.; Liu, Y.; Döll, P.; Eisner, S.; Gerten, D.; et al. Reconstruction of global gridded monthly sectoral water withdrawals for 1971–2010 and analysis of their spatiotemporal patterns. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2018, 22, 2117–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Yang, Y.; Xia, J. Hydrological cycle and water resources in a changing world: A review. Geogr. Sustain. 2021, 2, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falster, G.M.; Wright, N.M.; Abram, N.J.; Ukkola, A.M.; Henley, B.J. Potential for historically unprecedented Australian droughts from natural variability and climate change. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2024, 28, 1383–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkiaka, E. Exploring the socioeconomic determinants of water security in developing regions. Water Policy 2022, 24, 608–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, D.J.; Paltán, H.A.; García, L.E.; Ray, P.; George, S.F.S. Water-related infrastructure investments in a changing environment: A perspective from the World Bank. Water Policy 2021, 23, 31–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Cao, C.; Zhu, X.; Gao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, X. Unveiling hidden dynamics: Fine-scale mapping of groundwater-dependent ecosystems using multi-source Earth observations. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2025, 18, 2528636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, W.; Liu, L.; Tang, Q.; Liu, J.; Yang, H. Environmental flow requirements largely reshape global surface water scarcity assessment. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 104029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Liu, X.; Yang, H.; Ciais, P.; Wada, Y. Global Water Scarcity Assessment Incorporating Green Water in Crop Production. Water Resour. Res. 2022, 58, e2020WR028570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, F.; Moss, C.; Joy, E.J.M.; Quinn, R.; Scheelbeek, P.F.D.; Dangour, A.D.; Green, R. The Water Footprint of Diets: A Global Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Adv. Nutr. 2020, 11, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekstra, A.Y.; Chapagain, A.K.; Van Oel, P.R. Advancing Water Footprint Assessment Research: Challenges in Monitoring Progress towards Sustainable Development Goal 6. Water 2017, 9, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Sultan, M.; Wahr, J.; Yan, E. The use of GRACE data to monitor natural and anthropogenic induced variations in water availability across Africa. Earth Sci. Rev. 2014, 136, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyoum, W.M.; Milewski, A.M. Improved methods for estimating local terrestrial water dynamics from GRACE in the Northern High Plains. Adv. Water Resour. 2017, 110, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhani, P.; Esmaeilzadeh, H.; Deljouei, A.; Wolf, I.D.; Marcu, M.V.; Sadeghi, S.M.M. Assessing water security and footprint in hypersaline Lake Urmia. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 155, 110955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergier, I.; Assine, M.L.; McGlue, M.M.; Alho, C.J.R.; Silva, A.; Guerreiro, R.L.; Carvalho, J.C. Amazon rainforest modulation of water security in the Pantanal wetland. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 619, 1116–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castle, S.L.; Thomas, B.F.; Reager, J.T.; Rodell, M.; Swenson, S.C.; Famiglietti, J.S. Groundwater depletion during drought threatens future water security of the Colorado River Basin. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2014, 41, 5904–5911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chawla, I.; Karthikeyan, L.; Mishra, A.K. A review of remote sensing applications for water security: Quantity, quality, and extremes. J. Hydrol. 2020, 585, 124826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, K.; Liu, J.; Yan, L.; Huang, H. Integrating ecosystem services flows into water security simulations in water scarce areas: Present and future. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 670, 1037–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, K. Farmers’ adaptation to water scarcity in drought-prone environments: A case study of Rajshahi District, Bangladesh. Agric. Water Manag. 2015, 148, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, M.M.; Hoekstra, A.Y. Four billion people facing severe water scarcity. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1500323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Wu, X.; He, W.; Kong, Y.; Degefu, D.M.; Ramsey, T.S. Using the fuzzy evidential reasoning approach to assess and forecast the water conflict risk in transboundary Rivers: A case study of the Mekong river basin. J. Hydrol. 2023, 625, 130090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Lian, Z.; Sun, H.; Wu, X.; Bai, X.; Wang, C. Simulating trans-boundary watershed water resources conflict. Resour. Policy 2021, 73, 102139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ID | Parameters Used | Data Sources | Time Period | Temporal Resolution | Spatial Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | TWSA | GRACE/GRACE-FO | 2003–2019 | Monthly | 0.25° |

| 2 | Precipitation | GPM | 2003–2019 | Monthly | 10 km |

| 3 | Precipitation | ERA5 | 2003–2019 | Monthly | 0.1° |

| 4 | ET | GLEAM | 2003–2019 | Monthly | 0.25° |

| 5 | Soil Moisture | GLEAM | 2003–2019 | Monthly | 0.25° |

| 6 | Runoff | ERA5 | 2003–2019 | Monthly | 0.1° |

| 7 | Air temperature | ERA5 | 2003–2019 | Monthly | 0.1° |

| 8 | Surface Shortwave Radiation | ERA5 | 2003–2019 | Monthly | 0.1° |

| 9 | Glacier Mass Change | Hugonnet, McNabb, Berthier, Menounos, Nuth, Girod, Farinotti, Huss, Dussaillant, Brun and Kääb [20] | 2003–2019 | Monthly | 100 m |

| 10 | Agricultural water withdrawal | WaterGAP v.2.2d | 2003–2019 | Monthly | 0.5° |

| 11 | Non-agricultural water withdrawal | WaterGAP v.2.2d | 2003–2019 | Monthly | 0.5° |

| 12 | Statistical water withdrawal | Chinese Ministry of Water Resources | 2003–2015 | Annual | County-level |

| 13 | Statistical water withdrawal | FAO AQUASTAT | 2010, 2019 | Annual | Country-level |

| 14 | Nighttime Lights | DMSP-OLS and VIIRS-DNB | 2003–2019 | Monthly | 1 km |

| 15 | Land Cover | ESA | 2003–2019 | Annual | 300 m |

| 16 | Irrigated Areas | GMIA | 2003–2019 | Annual | ~10 km |

| 17 | scPDSI | CRU-TS version 4.08 | 2003–2019 | Monthly | 0.5° |

| 18 | Government effectiveness (GE) | World Bank | 2003–2019 | Annual | Country-level |

| 19 | Population | GPW | 2005, 2015 | Annual | 25 km |

| 20 | GDP | 2005, 2015 | Annual | ~10 km | |

| 21 | Human Development Index | Kummu, Taka and Guillaume [44] | 2005, 2015 | Annual | ~10 km |

| ID | Approach | Study Region | Descriptions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hydro-economic and water footprint diagnosis | Lake Urmia Basin, Iran | Establishing a direct link between agricultural water use (>85%) and ecological crises but remains static and omits adaptive capacity/governance. | Sobhani et al. [62] |

| 2 | Cross-system teleconnection analysis | Amazon-Pantanal Corridor, South America | Quantifying remote ecological dependence (>50% moisture contribution), but results are sensitive to moisture-tracking parameter choices. | Bergier et al. [63] |

| 3 | Groundwater depletion and drought response | Colorado River Basin, USA | Revealing >50% groundwater loss but focuses on a single component with limited surface-water integration. | Castle et al. [64] |

| 4 | Remote sensing technology monitoring | Global | Providing dynamic, meter-scale data in data-scarce regions, but indirect retrieval introduces ~10–30% uncertainty. | Chawla et al. [65] |

| 5 | Ecosystem services integrated modeling | Water-scarce areas (Regional scale) | Coupling ecosystem flows with water security, but high model complexity compounds uncertainty. | Qin et al. [66] |

| 6 | Atmospheric moisture tracking & source-sink analysis | Global | Quantifying transboundary moisture dependencies but is highly dependent on tracking algorithm assumptions. | Posada-Marín, Salazar, Rulli, Wang-Erlandsson and Jaramillo [11] |

| 7 | Integrating remote sensing, geospatial datasets, and ensemble machine learning techniques | Global | Reconstruct multi-year, high-resolution, globally consistent datasets; reduces reliance on parameterized land-surface models; integrates natural and socio-economic indicators. | This study |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Jin, G.; Luo, Z.; Sun, M.; Fu, Y.; Wu, T.; Liu, K. Towards a Global Water Use Scarcity Risk Assessment Framework: Integration of Remote Sensing and Geospatial Datasets. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3999. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243999

Wang Y, Li X, Jin G, Luo Z, Sun M, Fu Y, Wu T, Liu K. Towards a Global Water Use Scarcity Risk Assessment Framework: Integration of Remote Sensing and Geospatial Datasets. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):3999. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243999

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yunhan, Xueke Li, Guangqiu Jin, Zhou Luo, Mengze Sun, Yu Fu, Taixia Wu, and Kai Liu. 2025. "Towards a Global Water Use Scarcity Risk Assessment Framework: Integration of Remote Sensing and Geospatial Datasets" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 3999. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243999

APA StyleWang, Y., Li, X., Jin, G., Luo, Z., Sun, M., Fu, Y., Wu, T., & Liu, K. (2025). Towards a Global Water Use Scarcity Risk Assessment Framework: Integration of Remote Sensing and Geospatial Datasets. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 3999. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243999