1. Introduction

Icebergs in the Arctic are hazards to maritime operations. Iceberg detection with synthetic aperture radar (SAR) images is therefore of paramount importance to numerous industries, including shipping [

1], insurance [

2], oil and gas [

3], fishing and tourism [

4], as well as state-run ice services [

5]. SAR is particularly suitable for iceberg monitoring as it is an active remote sensing system capable of operating day and night, through all weather and cloud conditions. The Arctic’s remoteness and harsh environment make in situ iceberg observation logistically difficult, further emphasising the importance of remote methods.

Beyond SAR, iceberg detection has been approached with radar altimetry and scatterometry, which provide useful large-scale detection and size/height characterisation [

6,

7]. Optical sensors (e.g., Sentinel-2) are also commonly used for validation under cloud-free conditions. SAR remains attractive due to all-weather, day-night capability and high spatial resolution; however, combining modalities often yields the most robust operational solutions.

Globally, Arctic shipping activity has tripled since 2010 [

8]. Historical analyses of archival records indicate an average of roughly 2–3 ship–iceberg collisions per year over past centuries, but no recent consolidated global annual collision statistic is available [

9]. Climate change has accelerated sea-ice decline, opening new shipping routes such as the Northwest Passage, while simultaneously increasing iceberg calving rates [

10]. Around 30,000–40,000 medium-to-large icebergs are produced annually from Greenland’s marine-terminating glaciers [

11,

12].

Franz Josef Land (FJL), located in the Barents Sea, is an area where iceberg monitoring is especially needed due to high levels of shipping, fishing, and oil and gas activities. Icebergs in the Barents Sea originate primarily from marine-terminating glaciers in FJL, Svalbard, and Novaya Zemlya [

13]. Typical iceberg sizes are 91 m ± 51 m × 64 m ± 37 m × 15 ± 7 m (length × width × height) [

14]. The FJL region is characterised by the presence of fast ice—a stationary form of sea ice that remains attached to the coast or seabed [

15]. This environment creates a shear zone between fast and drift ice, within which icebergs can become embedded for months until the fast ice melts sufficiently for them to move freely. Detecting icebergs in such conditions allows for the labelling of icebergs in both optical and SAR data acquired several hours apart, as performed in this study.

Traditional iceberg detection approaches have largely relied on adaptive threshold algorithms [

16], such as Constant False Alarm Rate (CFAR) detection [

17], which exploit contrasts in radar backscatter between icebergs and surrounding sea ice. Many variants have been proposed, including the Dual Intensity Polarisation Ratio Anomaly Detector (iDPolRAD) introduced by ref. [

18] and subsequently applied in several studies [

12,

19]. The iDPolRAD algorithm leverages dual-polarisation Sentinel-1 Extra Wide Swath (EWS) imagery to enhance iceberg contrast by filtering and combining co-polarised (HH/VV) and cross-polarised (HV/VH) intensity images.

In recent years, deep learning methods have gained traction for iceberg detection and classification [

20,

21,

22,

23] due to the robustness of convolutional neural networks (CNNs). However, discriminating icebergs from sea ice remains challenging, as their SAR backscatter characteristics can be similar [

24] and are affected by factors such as surface roughness, dielectric constant, incidence angle, and proximity to the sensor’s noise floor [

25]. Sentinel-1′s spatial resolution in EWS mode (90 m) limits reliable detection to icebergs larger than ~100 m. Icebergs smaller than this threshold occupy only a few pixels and are difficult to detect reliably with Sentinel-1 EWS imagery. Optical Sentinel-2 imagery offers higher spatial resolution but suffers from cloud cover and seasonal darkness. Consequently, combining both datasets provide complementary information: SAR offers consistent temporal coverage, while optical imagery supports manual labelling and validation.

Several CNN architectures have been explored for general object detection, including ResNet [

26], Faster R-CNN [

27], Single Shot Detector (SSD) [

28], and You Only Look Once (YOLO) [

29]. Within iceberg detection, applications of YOLO remain limited, with [

30] being the only known study employing YOLOv3 for iceberg–ship discrimination in Sentinel-1 imagery. While they achieved a reasonable F1 score (0.53), the authors highlighted the limited availability of labelled iceberg data as the main barrier to improved performance. This challenge persists across the field, where the scarcity of labelled data and environmental constraints restrict the application of standard model-optimisation practices.

Previous detection methods, such as classical thresholding and CFAR, often lack the precision required to discriminate icebergs within high-clutter fast-ice environments, and can be computationally intensive for near-real-time use. This raises an important question regarding environmental feasibility: Can a modern CNN (YOLOv8) feasibly detect icebergs embedded in land-fast ice within the physical and observational limitations of SAR imagery?

Accordingly, the aim of this proof-of-concept study is to evaluate the feasibility of applying a YOLOv8 deep learning model within an iDPolRAD filtering framework to detect icebergs in the fast-ice environments of Franz Josef Land. The study demonstrates that a modern deep learning model can be adapted for a niche, data-limited, and environmentally constrained application, establishing the foundation for future large-scale implementations.

We note that the present experiments are restricted to land-fast sea ice. This environment is particularly challenging, with stationary floes and subtle iceberg contrasts, making it ideal for testing detection methods. While studies of icebergs in open water are well-established in the literature, we focus on sea ice to demonstrate performance under more difficult conditions. Consequently, although our model is tailored to fast sea ice, we expect it to perform reliably in open-water scenarios, where iceberg-background contrast is generally higher. While our findings motivate potential maritime-safety applications, direct operational deployment in shipping lanes requires further validation under open-water and drifting-ice conditions. Expected effects and a plan for such validation are discussed in

Section 5.

2. Dataset

This study utilises Sentinel-1 Extra Wide Swath (EWS) mode imagery [

31], which operates at C-band frequency in dual-polarisation (HH and HV) (

Table 1). The data are provided as Ground Range Detected (GRD) products, where the nominal pixel spacing is 40 m, and the effective spatial resolution is approximately 90 m. This distinction is important, as pixel spacing describes the image sampling interval, whereas spatial resolution describes the smallest ground feature that can be reliably distinguished. In the Barents Sea region, this mode allows image acquisitions up to twice per day, making it ideal for tracking iceberg and sea-ice dynamics under varying conditions.

Standard preprocessing steps were applied, including thermal-noise removal and radiometric calibration to a normalised radar cross section (σ

0) using the lookup tables provided in the accompanying XML metadata. All calibrated σ

0 values were converted to the decibel (dB) scale for analysis. Terrain correction was performed using the Sentinel-1 toolbox orthorectification routine with a digital elevation model, ensuring geometric (not radiometric) accuracy; multi-looking was not applied to preserve the spatial detail of small iceberg targets. All images were georeferenced using the GDAL 3.8.3. software library and projected into the EPSG:32640 coordinate reference system (UTM Zone 37 N). The selected acquisitions had incidence angles between 18° and 46°, providing sufficient contrast between icebergs and the surrounding fast ice for the application of the iDPolRAD algorithm (

Section 3.1). The two SAR acquisitions used in this study have the same overall incidence-angle range in the original metadata. While this removes variability between images at the acquisition stage, iceberg detectability may still vary locally within each swath due to incidence angle and orientation effects. We therefore continue to discuss this as a methodological limitation in

Section 5Complementary Sentinel-2 MSI optical imagery (

Table 2) was used for visual validation and manual iceberg labelling. Optical images were selected to have < 30% cloud cover and to be acquired outside the polar night period. Sentinel-2 provides up to 13 spectral bands covering the 440–2200 nm range; here, we used the visible bands (2, 3, 4) with a spatial resolution of 10 m to identify icebergs under clear-sky conditions. To facilitate co-registration and visual comparison, the SAR images were resampled to 10 m pixel size using bilinear interpolation.

Image pairs were chosen based on overlapping Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 acquisitions within the FJL region (

Figure 1). Temporal variability in iceberg drift and sea-ice deformation limited the number of valid pairs, as only scenes with consistent iceberg positions could be used. Additionally, high-latitude orbit constraints reduced overlap frequency, so the dataset represents carefully selected dates with adequate dual-sensor coverage.

For each selected region, SAR images were clipped to match the Sentinel-2 tiles (T40XEQ and T40XDQ;

Table 3), producing subset images aligned across both datasets. To exclude static land areas, a land mask from the Polar Geospatial Centre (500 m spatial resolution) was applied. Manual labelling was performed on these subsets, resulting in 1128 individual icebergs identified in T40XEQ and 1216 in T40XDQ, producing a high-quality dataset for CNN training and validation. The top-left physical coordinates of each SAR image slice are provided in

Supplementary Files S1 (tile T40XEQ) and S2 (tile T40XDQ).

Overall, this dataset reflects the practical constraints of iceberg detection in fast-ice environments: limited temporal overlap, environmental variability, and the need for manual labelling. Such conditions are central to evaluating the environmental feasibility of deep learning–based iceberg detection.

3. Materials and Methods

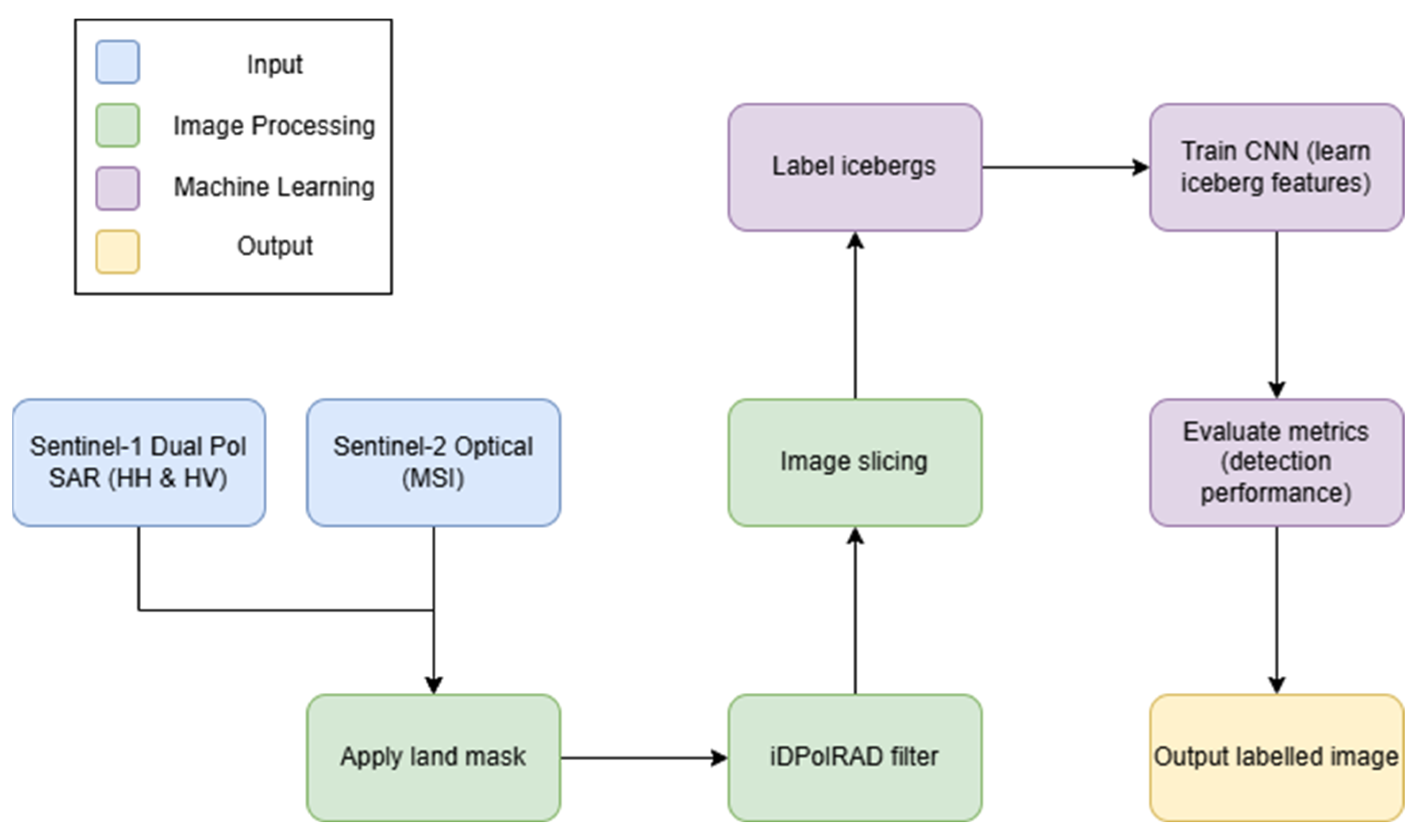

This study implements a deep learning–based detection workflow for icebergs embedded in land-fast sea ice (

Figure 2). For an introduction to polarimetric SAR (PolSAR) concepts, the reader is referred to [

32]. The methods proceed as follows:

iDPolRAD filtering to enhance iceberg contrast in SAR imagery (

Section 3.1).

Manual labelling of icebergs by visually comparing SAR and optical imagery to create a training dataset (

Section 3.2).

Convolutional neural network (CNN) architecture used for object detection (

Section 3.3).

This workflow allows us to demonstrate the environmental feasibility of applying CNNs to detect icebergs under the physical and observational constraints of the Franz Josef Land region.

3.1. iDPolRAD Filter

The iDPolRAD filter was proposed by [

18] and has been successfully applied in previous studies to separate and detect icebergs in sea-ice environments [

19,

33]. The filter exploits dual polarisation SAR data (in this case, HH and HV) to enhance contrast between icebergs and surrounding fast ice.

Icebergs exhibit distinct radar signatures due to volume scattering (from undulations, cracks, and crevasses) and surface scattering (from reflective ice surfaces or toppled ice bodies). In some cases, double-bounce scattering can occur when the radar pulse reflects off both the iceberg and the water surface. These mechanisms lead to a higher depolarisation ratio, defined as the ratio between the cross-polarised (HV) and co-polarised (HH) intensity images, which differentiates icebergs from surrounding sea ice.

To quantify this, two boxcar filters are applied over the HV and HH intensity images using a small testing window (1 × 1 pixels) within a larger training window (57 × 57 pixels). The detector can be written as

where

and

represent spatial averages over the testing and training windows, and

is a threshold. Traditionally, the threshold is set to optimise a probability density function as in CFAR detectors. Here, rather than applying a threshold at this stage, we generate iDPolRAD filtered images as input for the CNN, allowing the network to learn features directly from the processed data.

The training window is implemented as a 57 × 57 pixel region with a 2D Gaussian weighting (σ = 7) centred on the pixel of interest, following Soldal et al. (2019) [

33], and the testing window is a single pixel (1 × 1). These choices were selected because comparison of different training σ values and test window sizes showed that this configuration gave the best separation between icebergs and background. The training window captures local background statistics while preserving small iceberg features, and the testing window corresponds to the pixel being evaluated in the HV image.

Because

is a ratio, the detector is scale-invariant, which can reduce intensity information. To restore this, we multiply

by the HV intensity:

A detection occurs when pixels in the testing window exhibit stronger volume or double-bounce scattering than the surrounding training window. Negative values indicate lower cross-polarisation than the local background, which can happen over open water patches.

3.2. Manual Detection

Manual detection was performed to generate a high-quality training dataset for the CNN, based on both SAR and optical imagery. To facilitate this, the Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 images were divided into image slices of 549 × 549 pixels. Twenty slices per row were selected, producing a total of 400 slices for manual inspection. This tiling also reduced computational load. Assuming that the data is sampled with a 10 m pixel spacing, the physical coordinates of each slice’s top-left corner were recorded to enable conversion between pixel and real-world coordinates:

where

and

are the top-left physical x and y coordinates of each slice.

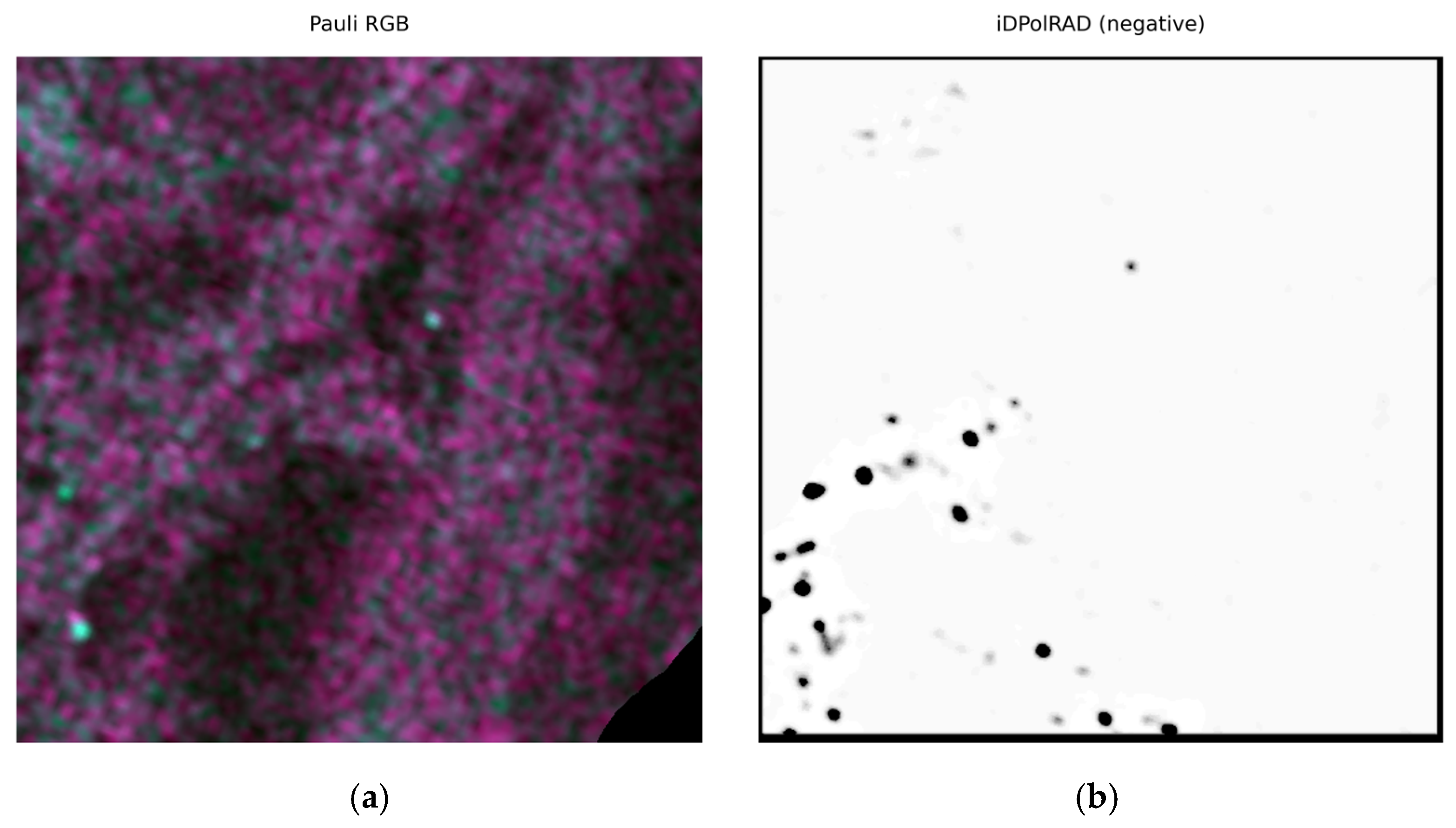

SAR HH and HV slices were combined using the iDPolRAD filter proposed by [

18] (Equations (1) and (2)) to enhance contrast between icebergs and fast ice. Training and testing windows of 57 and 1 pixels, respectively, were found to be the most optimal for distinguishing icebergs from clutter in the SAR images to optimise iceberg discrimination. Image display contrast was adjusted using the 5th and 95th percentile pixel values to improve visual identification. Preliminary RGB composites of SAR and optical images were used to aid manual detection (

Figure 3).

Icebergs were selected if they satisfied the following criteria:

Visible in both SAR and optical imagery.

Bright relative to the surrounding clutter in SAR.

Exhibited a shadow in optical imagery.

Embedded in fast ice, reducing the likelihood of drift between image acquisitions.

Because pre-filtering excludes icebergs not visible in SAR, reported accuracy reflects the CNN’s ability to detect icebergs visible in SAR data, not the total number present. This ensures meaningful validation under Sentinel-1 resolution constraints while minimising false detections from ships, islands, or other sea ice features.

Land areas were excluded using a two-stage masking procedure. First, a coarse 500 m Polar Geospatial Centre land mask was applied to remove large-scale continental land. Second, a fine shoreline filter based on the DEM with a 13 m elevation threshold was applied to remove near-shore high-reflectance features and coastal clutter not excluded by the coarse mask. The 13 m threshold was chosen empirically by visual comparison with HH SAR images to best separate water/fast ice from land and represents a conservative elevation above typical tidal and shoreline variations in the study area. This approach reduced false positives at the coastline.

For labelling, bounding boxes were manually drawn around each iceberg in SAR slices, validated against the corresponding optical image. All boxes were annotated by a single author. Objects were included only if they exhibited sufficient contrast with the surrounding ice; borderline or uncertain cases were excluded from the training set. Boxes were centred approximately on each iceberg, but not perfectly aligned, to prevent the model from overfitting to central positions. Box sizes varied with iceberg size; those near slice edges were clipped by 10 pixels to preserve spatial context (avoiding edge artifacts introduced by local filters and resampling). Bounding box coordinates (pixel-based) and class labels were exported using Label Studio 1.13.1 in a format compatible with the CNN, along with the corresponding image slices (PNG format).

This procedure produced a labelled dataset suitable for CNN training while maintaining high visual fidelity to both SAR and optical observations.

3.3. YOLOv8 Model

For iceberg detection, we employ YOLOv8, a state-of-the-art single-stage CNN known for high accuracy, speed, and ease of use [

29]. YOLOv8 predicts bounding boxes and class probabilities for objects in an image and is trained on annotated datasets [

34]. In this study, the model predicts the presence of icebergs in iDPolRAD-processed SAR slices.

The network consists of a backbone, a neck, and a head. The backbone uses a Cross Stage Partial-Darknet architecture to extract features at multiple scales, the neck merges the features to capture information across scales, and the head predicts bounding boxes, objectness scores, and class probabilities. YOLOv8 employs coarse-to-fine convolutional blocks and anchor-free detection, making it particularly suited for small, variable-brightness targets like icebergs. Unlike sliding-window approaches, the model processes the full image in a single forward pass, so pre-filtering with iDPolRAD ensures small icebergs remain detectable.

Key advantages of YOLOv8 for this application include the following:

Fast inference speed, enabling near-real-time monitoring.

Robustness to SAR backscatter variability through integrated augmentation strategies.

Improved localisation precision in cluttered fast-ice environments.

Detection of small objects with variable brightness, critical for icebergs.

We use the medium YOLOv8 model (yolov8m.pt) with 218 layers and 25.9 million parameters. The network employs three loss functions:

Centre distance intersection over union (CIoU) loss for bounding box geometry;

Varifocal loss for classification accuracy;

Distribution Focal Loss (DFL) for localisation precision.

These three components use the default loss-weighting scheme implemented in Ultralytics YOLOv8 (i.e., the framework applies its own internal weights to Lobj, Lcls, and Lbox), and no additional manual re-weighting was applied.

Bounding boxes are used instead of instance segmentation because icebergs are small relative to Sentinel-1 resolution, and bounding boxes reduce sensitivity to slight shape errors. Only icebergs visible in both SAR and optical imagery are labelled to ensure target purity.

This study is the first application of a CNN (YOLOv8) to iDPolRAD-processed Sentinel-1 data. Novel contributions include the following:

Replacing classical CFAR detection with a CNN.

A dual SAR/optical verification strategy to reduce false positives.

A pre-processing pipeline in which SAR images are terrain-corrected and geocoded, and Sentinel-2 images are resampled to the same projection, enabling dual SAR/optical validation without performing explicit image co-registration. Benchmarking CNN performance against prior CFAR results in the same region.

The choice of YOLOv8 for this study is motivated by its combination of accuracy, speed, and ease of use, which makes it well-suited for a proof-of-concept evaluation under Arctic SAR constraints. Although two-stage detectors such as Faster R-CNN may offer higher small-object localisation precision, YOLOv8 provides a practical balance between detection accuracy and inference speed. Pre-filtering with iDPolRAD enhances small-object contrast, improving YOLOv8’s ability to detect icebergs embedded in fast ice while maintaining computational efficiency. Unlike previous approaches using CFAR or older YOLO versions, this study demonstrates that a modern CNN can be applied successfully to iDPolRAD-processed Sentinel-1 data and validated with Sentinel-2 imagery. The novelty lies not merely in replacing CFAR with a CNN, but in demonstrating that the YOLOv8-based pipeline is feasible in a challenging, high-latitude, cluttered fast-ice environment with limited labelled data. While YOLOv8 is a large model, the goal here is environmental feasibility rather than model optimisation; pre-filtering with iDPolRAD ensures that small icebergs are detectable despite the network’s size and limited training dataset. Finally, bounding boxes were chosen over polygons due to Sentinel-1’s spatial resolution, which preserves the key features for CNN detection while minimising errors. This approach validates the concept that CNN-based detection can function effectively with the combination of SAR and optical data under operationally realistic conditions.

3.4. Evaluation Metrics

The labelled iDPolRAD image slices were used to train the YOLOv8 model. Training was performed using the standard medium model with pretrained weights to improve feature extraction, given the limited dataset. We used the default Ultralytics COCO-trained weights. The dataset was split into training (80%) and validation (20%) sets, ensuring that images from the same temporal acquisition were not split across sets to avoid data leakage.

To augment the limited SAR dataset, data augmentations such as horizontal/vertical flips, small rotations were applied. Because iceberg shapes lack a preferred orientation in SAR, augmentation was performed using flips rather than full rotations. Each image was augmented with a horizontal flip, a vertical flip, and a horizontal–vertical flip, resulting in three additional training samples per original. These simulate variations in SAR backscatter, iceberg orientation, and ice state, improving the model’s ability to generalise to unseen images. Training was performed on a standard GPU setup, taking approximately 12 min, with validation performed in 1 min.

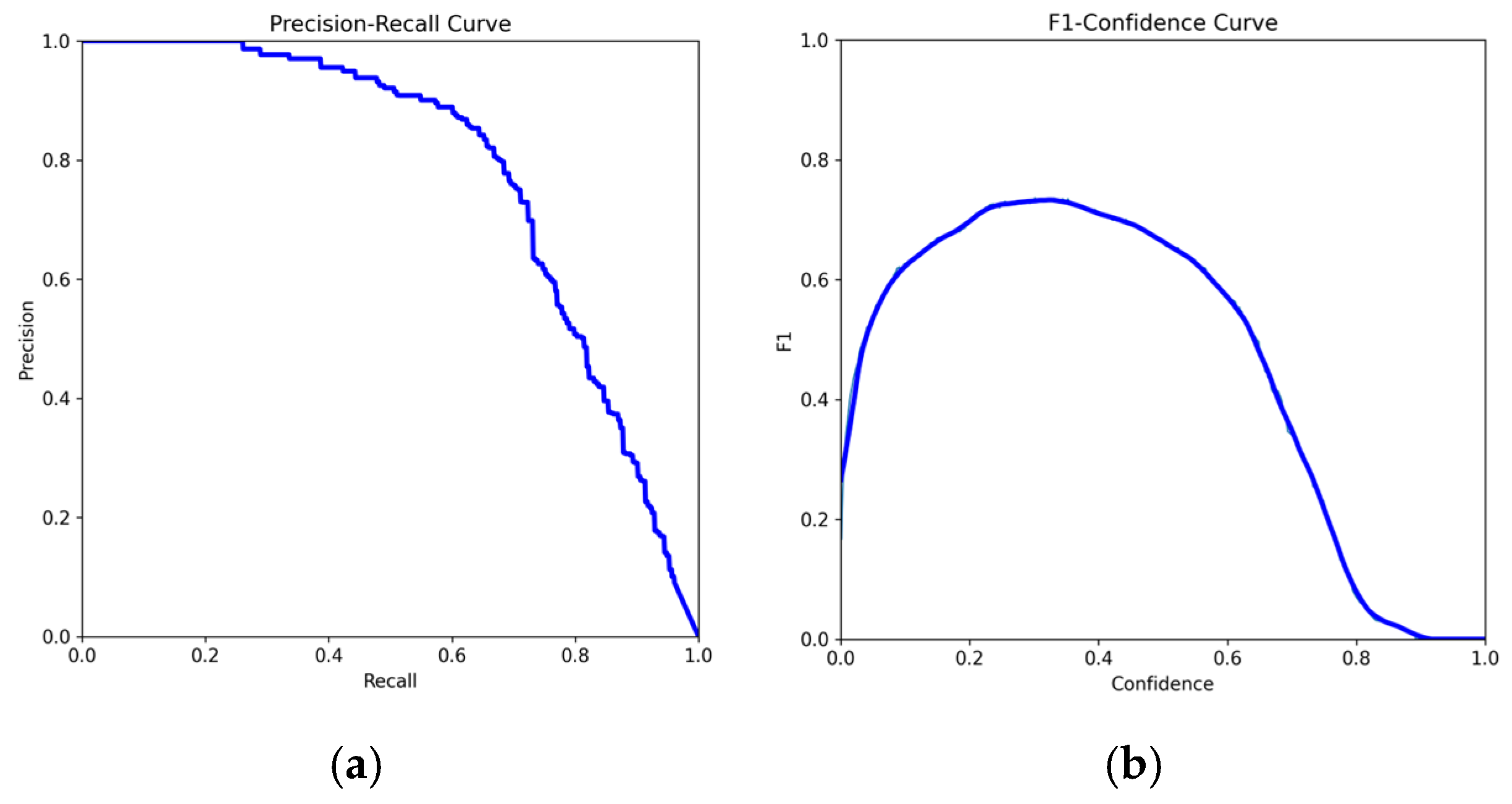

Evaluation metrics were calculated to quantify model performance, including Precision, Recall, F1 score, mean average precision (mAP), and CIoU. These are defined as follows:

where TP, FP, and FN are true positives, false positives, and false negatives, respectively. Precision measures the ratio of correctly detected icebergs to all detections, while recall measures the proportion of detectable icebergs successfully identified. F1 combines both to assess overall performance.

To complement precision, recall, and F1, we also report mean Average Precision (mAP), defined as the mean of the area under the precision–recall curve across IoU thresholds (t). Specifically, mAP is computed as follows:

where

is the integral of the precision–recall curve at IoU threshold

, which is defined as

where

is the precision–recall curve at a given IoU threshold.

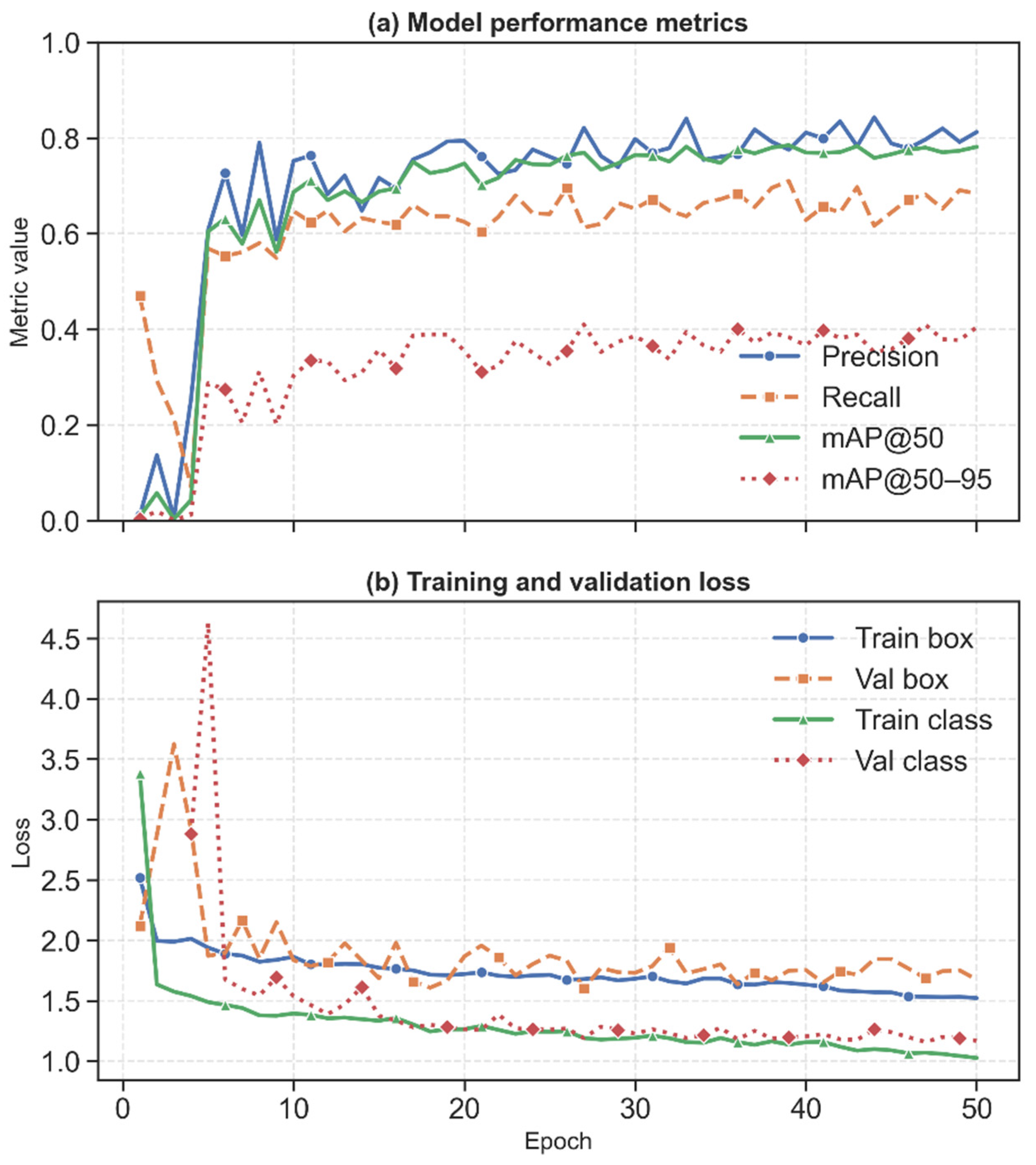

For this study, we report mAP 50 and mAP 50–95, where 50 denotes average precision (AP) at IoU = 0.50, and 50–95 denotes the average AP across IoU thresholds from 0.50 to 0.95 in 0.05 increments (COCO-style mAP [0.5:0.95]). Although CIoU (centre distance IoU) was used as the bounding-box loss during training, evaluation metrics in

Figure 4 are computed using standard AP measures rather than generalised intersection over union (GIoU). YOLOv8 model training metrics are reported in

Supplementary File S3. The configuration parameters used for YOLOv8 training are listed in

Supplementary File S4.

3.5. Comparison to Soldal et al. (2019) [33]

The iceberg detection workflow in this study uses Sentinel-1 data pre-processed with the iDPolRAD chain, which includes radiometric calibration, geometric correction, and speckle filtering. These processed backscatter tiles are then supplied to the YOLOv8 CNN for supervised training and testing.

While the iDPolRAD preprocessing itself is not novel, the key difference lies in the detection stage. Ref. [

33] employed classical CFAR thresholding combined with a technique they referred to as “blob detection” to identify iceberg candidates. Here, “blob” simply denotes regions exceeding a backscatter threshold. In contrast, our approach replaces this rule-based stage with a deep learning–based CNN, enabling the model to directly learn iceberg signatures from labelled data, including subtle features in complex fast-ice environments.

This comparison highlights that the novelty of this study lies in the integration of a modern CNN detection framework with iDPolRAD-pre-processed SAR data, demonstrating the feasibility of automated iceberg detection under Arctic operational constraints.

5. Discussion

In this work, we considered the feasibility of implementing the YOLOv8 CNN for iceberg detection in a fast sea ice environment. Below, we outline the major issues facing detection and modelling, and place our findings in context with previous work.

5.1. Comparison with Soldal Results

The precision, recall, and F1 scores reflect the performance of our model based on one primary approach to detect icebergs in the SAR iDPolRAD images. Bright iceberg-like objects exhibited higher prediction values, likely due to strong HV backscatter observed in the imagery. While HH polarisation can also produce strong returns, HV generally provides better contrast between icebergs and fast ice in our dataset. These observations are directly derived from the Sentinel-1 imagery used in this study and are consistent with previous studies [

18,

33].

Ref. [

33] applied a blob detector followed by a traditional CFAR approach. The blob detector first identified candidate bright regions in the SAR images based on local intensity variations, and CFAR then filtered these candidates based on local background statistics to maintain a constant false-alarm rate. Their metrics depended heavily on the CFAR Probability of False Alarm (PF) threshold, while YOLOv8 outputs both precision and recall at a single confidence threshold and aggregated mAP. Ref. [

33] often experienced high false positives relative to true detections, whereas YOLOv8 achieved higher detection rates with fewer false alarms. However, since our training labels were pre-filtered to include only targets visible in Sentinel-2 imagery, the metrics likely represent an upper bound for visually verifiable icebergs. Difficulties remain in discriminating icebergs from fast ice features such as hummocks and ridges.

It is important to note that our workflow does not employ CFAR. The iDPolRAD preprocessing used here is non-CFAR-based, and detection is performed solely by the YOLOv8 model. CFAR is discussed only in the context of the baseline provided by [

33]. Parameter tuning of CFAR is therefore not applicable to our method.

5.2. Alternative Baselines and Future Work

Besides CFAR and blob detection, a range of non-deep learning methods have been used for SAR target detection, including matched-filter/template matching [

35], morphological blob detectors ref. [

17], texture-based classification (e.g., GLCM features + Support Vector Machine) [

36], Hough-transform methods for geometric features [

37], and other local-statistics anomaly detectors. Lightweight deep learning models, for example, compact CNNs, or small single-stage detectors, such as YOLOv8n/YOLOv8s or MobileNet-SSD [

38], also provide attractive baselines when training data are limited. A comprehensive comparison of these approaches against the YOLOv8 pipeline (including parameter optimisation for classical detectors and the design/training of a simple CNN baseline) is outside the scope of the present proof-of-concept, but we recognise its importance and plan it as immediate future work to quantify trade-offs in accuracy, false-alarm characteristics, and computational cost.

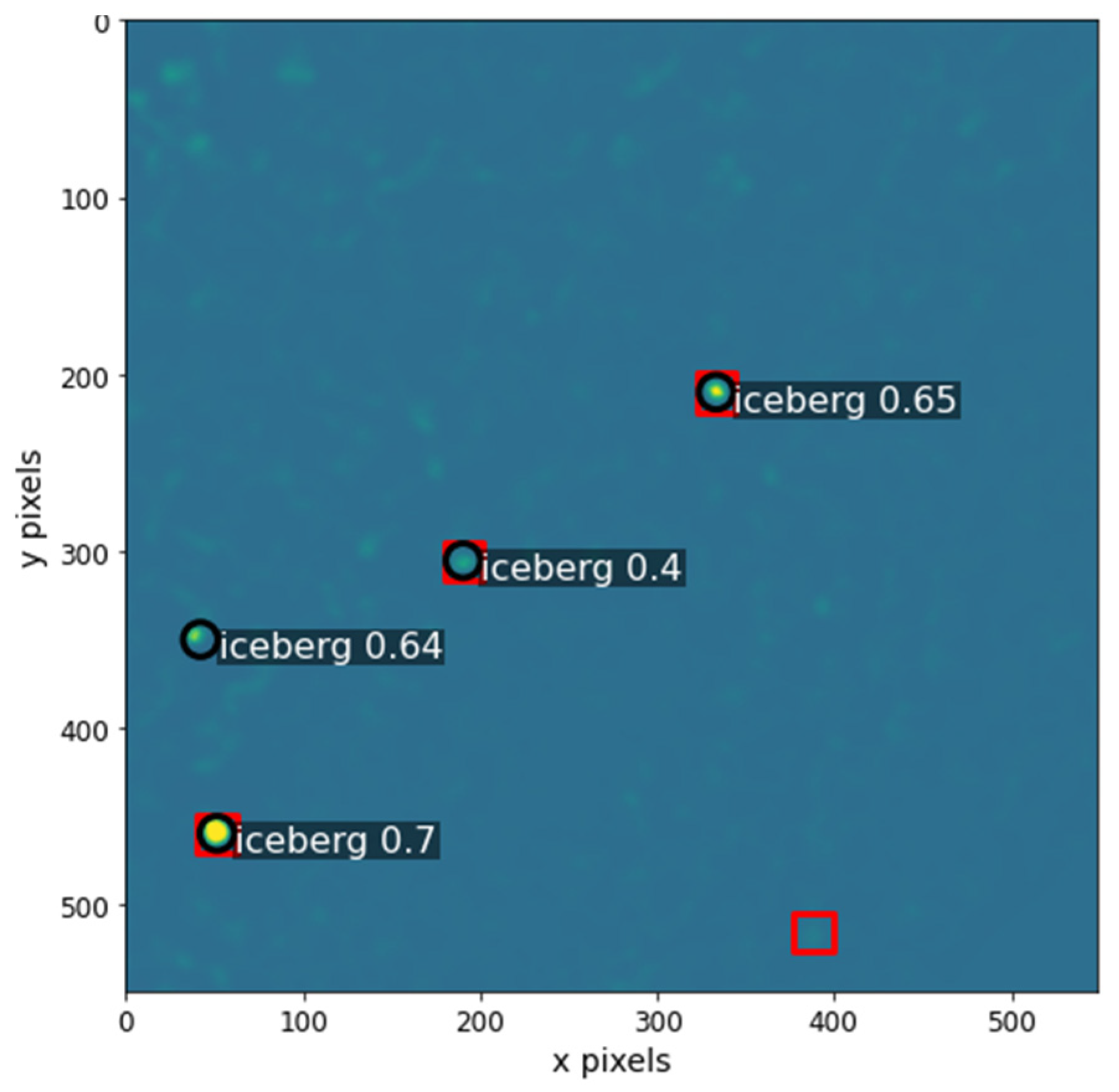

5.3. Failure Case Analysis

Although overall detection performance is high, several systematic failure modes were observed during visual inspection of the validation results. We show a representative example of a false positive and a false negative in

Figure 7.

False positives were primarily associated with sea-ice ridges and rough fast-ice zones, which often exhibit strong HH and HV backscatter and therefore resemble iceberg signatures in iDPolRAD-filtered imagery. In several scenes, the model responded to elongated ridge features that produce bright, compact highlights at 90 m resolution, making them indistinguishable from small tabular icebergs. A second false-positive category consisted of bright brash-ice patches or refrozen fracture zones, which form small high-backscatter clusters similar in size and texture to iceberg fragments. Occasional false responses to SAR side-lobe or multi-path artefacts were also observed, although these were infrequent.

False negatives were typically linked to icebergs with very low contrast relative to the surrounding fast ice, for example, where surface snow cover reduces HV volume scattering or where the surrounding ice was unusually bright. Several missed targets were close to or below the effective resolution limit of Sentinel-1 EWS mode (≈90 m), making them only 1–2 resolution cells in extent. In such cases, even manual identification was uncertain. A small number of icebergs embedded within high-backscatter ridge complexes were also missed, as the local background suppressed the contrast required for detection.

These patterns indicate that most failure cases arise from SAR backscatter physics and resolution constraints, rather than from model architecture limitations. Improved performance would likely require (i) training data that explicitly includes ridge-dominated and low-contrast conditions, (ii) incidence-angle-normalised inputs, or (iii) higher-resolution sensors such as Sentinel-1 Single Look Complex (SLC) or commercial SAR.

5.4. Study Limitations

Dataset and domain limitations: The study is based on a limited number of Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 scenes covering specific dates and regions in the FJL archipelago. Seasonal variability in iceberg production, fast-ice extent, and environmental conditions (e.g., wind, sea state, and snow cover) was not included, potentially limiting generalisability. Detection performance may also vary seasonally: in summer or melt-season conditions, melt ponds and other surface features can produce low-backscatter areas resembling open water, reducing the contrast between icebergs and surrounding sea ice. The current model has only been evaluated on fast-ice conditions; performance under summer conditions remains to be assessed in future work. Regional factors such as glacier terminus geometry, local bathymetry, and fast-ice topography may also influence backscatter and detection performance, requiring future evaluation. The model is trained exclusively on Franz Josef Land data, and performance in other Arctic regions may differ due to variations in sea ice dynamics, snow cover, salinity, and other environmental factors affecting SAR backscatter. Additional region-specific training or fine-tuning would be required to extend the approach to other Arctic areas.

Radar data characteristics: Sentinel-1 GRD data were radiometrically calibrated and terrain-corrected, but no additional normalisation for incidence angle variation was applied. Incidence angles ranged from 18 to 46°, which may affect backscatter intensity and iceberg detectability, particularly for low-contrast targets [

25]. Detection performance may therefore vary with iceberg orientation and size. Future work could incorporate incidence-angle correction or gamma nought normalisation to mitigate this variability.

Polarimetric limitations: Only dual-polarisation (HH/HV) data were available. Fully polarimetric SAR could improve discrimination between icebergs and fast ice by exploiting additional scattering channels, although such data are typically available only during Announcement of Opportunity periods and have narrower swath widths.

Detection approach: Object detection was prioritised over instance segmentation due to the resolution of Sentinel-1 data. Icebergs < 120 m are unlikely to be reliably detected, and bounding boxes provide a practical compromise, capturing both the iceberg and its immediate context. Pre-filtering to include only icebergs visible in both Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 likely inflates the reported metrics, and results should be interpreted as an upper bound.

Training data constraints: There is a lack of available labelled iceberg datasets. Manual labelling is time-consuming, and iceberg populations change annually, meaning that comprehensive datasets across Greenland, Svalbard, and FJL remain unavailable.

Applicability to open water: In open-water/drifting-ice environments, the contrast between iceberg and background can change due to vessel-induced wakes, ocean surface roughness and larger Doppler effects. iDPolRAD preprocessing may respond differently where the background is dynamic rather than stationary. We therefore expect (a) increased false positives from transient low-backscatter features (e.g., wind-roughened water, breaking waves), and (b) potential detection of smaller icebergs due to higher contrast against open water, but with different false-alarm characteristics. We plan to evaluate performance on Sentinel-1 scenes with documented drifting ice and AIS-correlated iceberg observations in future work.

Despite dataset and environmental constraints, this study demonstrates that YOLOv8 CNNs, when combined with iDPolRAD filtering, are feasible for automated detection of icebergs in fast ice environments. The approach could be scaled to other Arctic regions with similar environmental characteristics, particularly where overlapping SAR and optical imagery are available. Operational deployment would benefit maritime safety by providing near-real-time monitoring of iceberg hazards and supporting climate monitoring by enabling consistent iceberg tracking under challenging polar conditions.

6. Conclusions

In this proof-of-concept study, we proposed an automated deep learning approach for detecting icebergs using ESA Sentinel-1 satellite imagery around Franz Josef Land (FJL) in the Arctic. Our work demonstrates the capabilities of the YOLOv8 CNN framework while highlighting key implementation challenges.

The YOLOv8 model achieved a high F1 score of 0.74 and a mAP50 of 0.78, corresponding to an overall accuracy of 78% for detecting icebergs embedded in fast ice. While this is the first study to combine a CNN with an iDPolRAD filter for iceberg detection, these results should be interpreted with caution. Model performance under more variable conditions, such as open water environments, remains unknown. Additionally, instance segmentation was not performed, so the detection of smaller icebergs may be limited by spatial resolution and polarisation modes. Future work could explore combining object detection and instance segmentation with higher-resolution, quad-polarimetric SAR imagery.

A major limitation remains the lack of extensive labelled datasets, driven by the dynamic environment around glacier tongues. Expanding training datasets through additional overlapping acquisitions could help improve model robustness. Although icebergs generally exhibit strong cross-polarised backscatter, some icebergs remain undetectable in SAR imagery compared to optical imagery. Despite these limitations, our results indicate that integrating YOLOv8 CNNs with iDPolRAD filtering offers a promising approach for automated iceberg detection, with potential benefits for maritime safety and climate change research.