A Dynamic Gaussian Modified Spectral Band Adjustment Factors Method for Radiometric Cross-Calibration of HJ-2A/HSI with ZY1-02D/AHSI

Highlights

- A DG-SBAF method was developed to model spectral channels with Gaussian response functions, dynamically matching multiple reference-sensor channels and optimizing SBAF weights.

- Applied to HJ-2A/HSI–ZY-1-02D/AHSI cross-calibration, the method achieved 12.11% and 8.64% relative improvements in VNIR and SWIR, respectively.

- DG-SBAF mitigates spectral mismatches and enhances radiometric stability.

- Enables more accurate on-orbit calibration and long-term radiometric consistency among sensors.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Calibration Sites and Data Preparation

2.1. Calibration Sites

2.2. Data Preparation

2.3. Data Preprocessing

3. Methodology

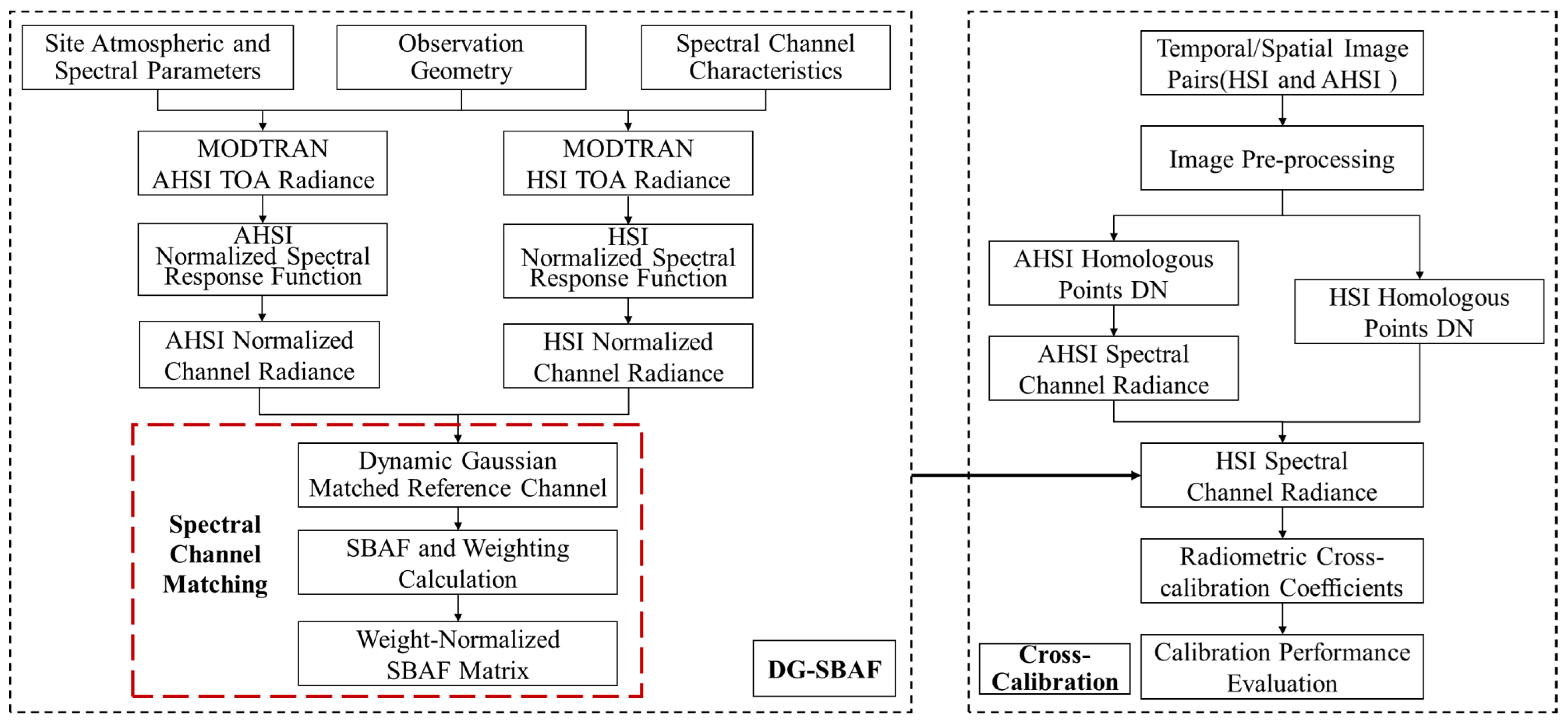

3.1. Overall Workflow for Cross-Calibration

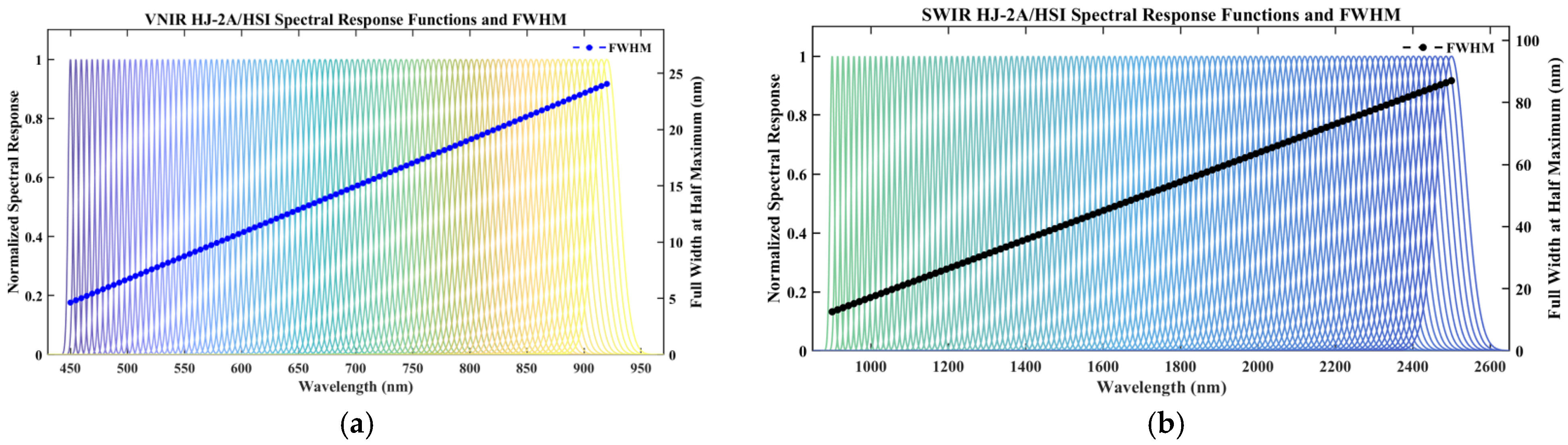

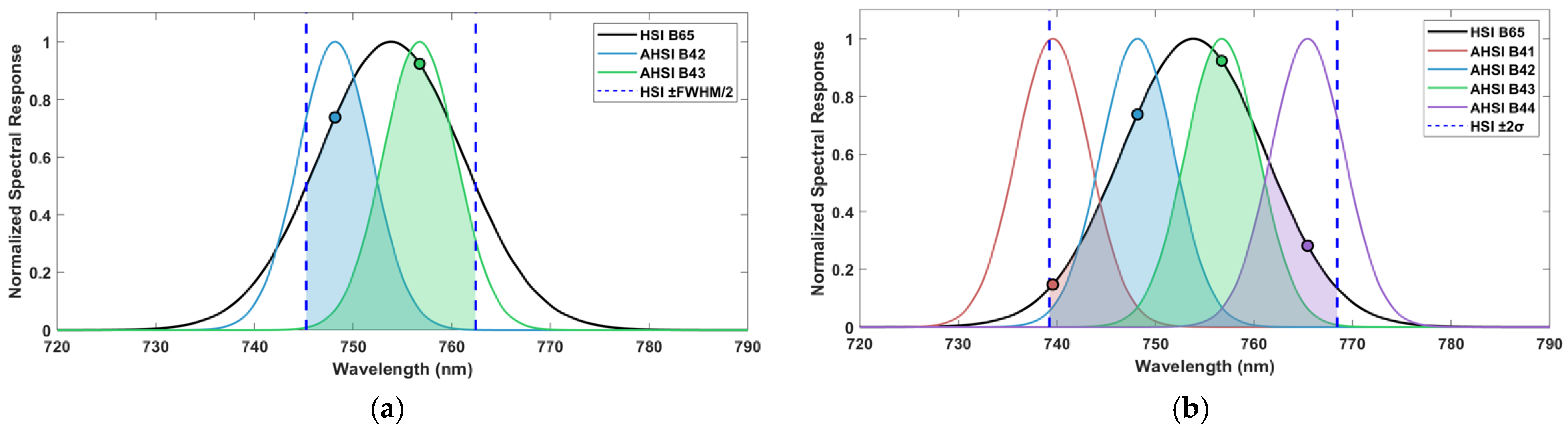

3.2. Dynamic Gaussian Modified SBAF Method

3.3. Validation Metrics

4. Results

4.1. Cross-Calibration Results

4.2. Validation Results

5. Discussion

5.1. DG-SBAF Method Generalizability and Limitations

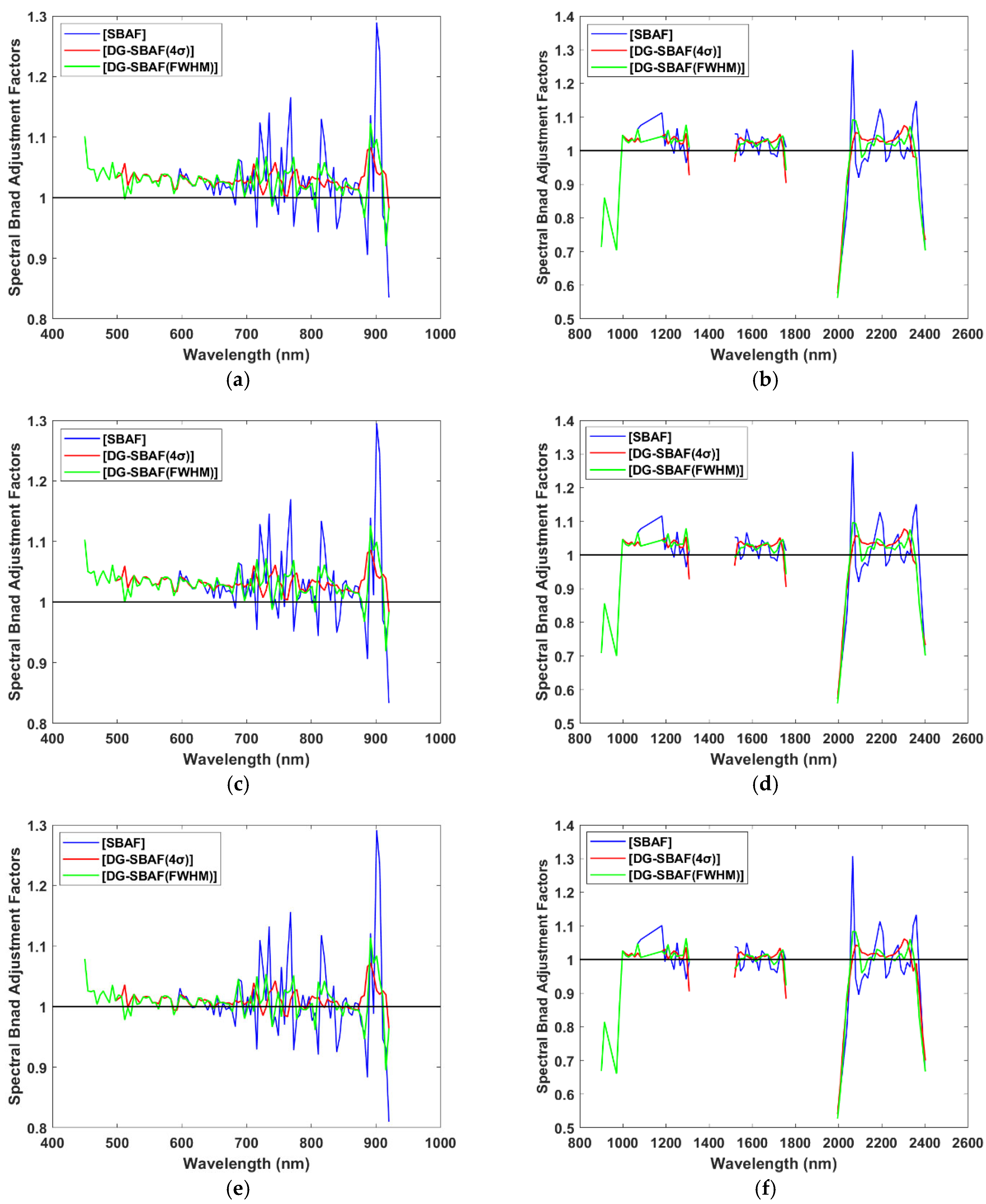

5.2. SBAF Fluctuation

5.3. Calibration Sites Stability

5.4. Cross-Calibration Accuracy Limitation

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DG-SBAF | Dynamic Gaussian Spectral Band Adjustment Factors |

| HJ-2A/HSI | Huanjing Jianzai-2A hyperspectral imager |

| ZY1-02D/AHSI | ZiYuan1-02D Advanced Hyperspectral Imager |

| GF-5B/AHSI | Gaofen-5B Advanced Hyperspectral Imager |

| Landsat-9/OLI-2 | Landsat-9 Operational Land Imager-2 |

| SWIR | Short-wave Infrared |

| VNIR | Visible and Near-infrared |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| EO-1 | Earth Observing-1 |

| Landsat 7/ETM+ | Landsat 7/Enhanced Thematic Mapper Plus |

| Terra/MODIS | Terra/Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer |

| FY-4A/AGRI | FengYun-4A/Advanced Geostationary Radiation Imager |

| GF-1/PMS | Gaofen-1/Panchromatic and Multispectral Sensor |

| Landsat-8/OLI | Landsat-8/Operational Land Imager |

| Landsat-5/TM | Landsat-5/Thematic Mapper Thematic Mapper |

| MODTRAN | MODerate resolution TRANsmission |

| HY-1C/COCTS | HaiYang-1C/Chinese Ocean Color and Temperature Scanner |

| Sentinel-3/OLCI | Sentinel-3/Ocean and Land Colour Instrument |

| CBERS | China-Brazil Earth Resources Satellite |

| CEOS | Committee on Earth Observation Satellites |

| WGCV | Working Group on Calibration and Validation |

| RadCalNet | Radiometric Calibration Network |

| CV | Coefficient of variation |

| DN | Digital number |

| SNR | Signal-to-noise ratios |

| SURF | Speeded-Up Robust Features |

| TOA | Top-of-atmosphere |

| SRF | Spectral response functions |

| FWHM | Full width at half maximum |

| SAM | Spectral Angle Mapper |

| RD | Relative deviation |

| BRDF | Bidirectional Reflectance Distribution Function |

References

- Li, S.; Wei, Z.; Wang, P.; Hu, K.; Liu, M. Study on applications of HJ-2A/B satellites for emergency response and disaster risk reduction. Spacecr. Eng. 2022, 31, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Bai, G.; Dong, J.; Zhu, J.; Cong, Q.; Yao, S.; Li, Z.; Lin, J.; Zhuang, C. Imaging model design and effectiveness evaluation of HJ-2A/B satellites. Spacecr. Eng. 2022, 31, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ABai, Z.; Dong, J.; Zhu, J.; Sun, J.; Ma, L. System design and technology innovation of HJ-2A/B satellites. Spacecr. Eng. 2022, 31, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Chen, X.; Liu, X.; Hu, B.; Li, S.; Hao, X. Design and verification of hyperspectral imager on HJ-2A/B satellites. Spacecr. Eng. 2022, 31, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, J.; Wei, R.; Yu, T.; Lv, Q.; Zhou, J.; Wang, L. Influence of optical system distortion on LASIS data. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Conference on Imaging Systems and Techniques Proceedings, Manchester, UK, 16–17 July 2012; IEEE: Manchester, UK, 2012; pp. 148–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Centre for Resources Satellite Data and Application. The Absolute Radiometric Calibration Coefficients of Domestic Civilian Land Observation Satellites. Available online: https://www.cresda.cn/zgzywxyyzx/zlxz/0107/20250107110105361912927_pc.html (accessed on 23 December 2024).

- Chander, G.; Angal, A.; Choi, T.; Xiong, X. Radiometric cross-calibration of EO-1 ALI with L7 ETM+ and Terra MODIS sensors using near-simultaneous desert observations. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2013, 6, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Li, H.; Zhou, G.; Tian, Z.; Wu, L. Cross-radiometric calibration and NDVI application comparison of FY-4A/AGRI based on Aqua-MODIS. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Gu, X.; Yu, T.; Sun, Y.; Liu, Q. Cross-calibration of GF-1 PMS sensor with Landsat 8 OLI and Terra MODIS. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2016, 54, 4847–4854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelmann, J.E.; Helder, D.; Morfitt, R.; Choate, M.J.; Merchant, J.W.; Bulley, H. Effects of Landsat 5 Thematic Mapper and Landsat 7 Enhanced Thematic Mapper Plus radiometric and geometric calibrations and corrections on landscape characterization. Remote Sens. Environ. 2001, 78, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markham, B.L.; Storey, J.C.; Williams, D.L.; Irons, J.R. Landsat sensor performance: History and current status. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2004, 42, 2691–2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chander, G.; Mishra, N.; Helder, D.L.; Aaron, D.B.; Angal, A.; Choi, T.; Xiong, X.; Doelling, D.R. Applications of spectral band adjustment factors (SBAF) for cross-calibration. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2013, 51, 1267–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villaescusa-Nadal, J.L.; Franch, B.; Roger, J.-C.; Vermote, E.F.; Skakun, S.; Justice, C. Spectral adjustment model’s analysis and application to remote sensing data. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2019, 12, 961–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Feng, D.; Shao, W.; Han, J.; Chen, Y. Radiometric cross calibration of HY-1C/COCTS based on Sentinel-3/OLCI. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 10422–10431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; He, Z.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, H. Radiometric Cross-Calibration of GF6-PMS and WFV Sensors with Sentinel 2-MSI and Landsat 9-OLI2. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, B.; Zhang, Y.; Du, T.; Yang, A.; Lv, W.; Liu, Q. Cross-calibration of HJ-1/CCD over a desert site using Landsat ETM + imagery and ASTER GDEM product. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2014, 52, 7247–7263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajardo Rueda, J.; Leigh, L.; Kaewmanee, M.; Monali Adrija, H.; Teixeira Pinto, C. Derivation of Hyperspectral Profiles for Global Extended Pseudo Invariant Calibration Sites (EPICS) and Their Application in Satellite Sensor Cross-Calibration. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Tao, Z.; Xie, Y.; Li, H.; Liu, Q.; Guan, X. A novel radiometric cross-calibration of GF-6/WFV with MODIS at the Dunhuang radiometric calibration site. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 1645–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Jiang, X.; Li, X.; Li, X. The cross-calibration of CBERS-02B/CCD visible–near infrared channels with Terra/MODIS channels. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2012, 34, 3688–3698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Gu, X.; Yu, T.; Liu, L.; Sun, Y.; Xie, Y.; Liu, Q. Validation of the Calibration Coefficient of the GaoFen-1 PMS Sensor Using the Landsat 8 OLI. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Zhao, Y.; Li, C.; Ma, L.; Wang, N.; Qian, Y.; Ren, L. An Investigation of a Novel Cross-Calibration Method of FY-3C/VIRR against NPP/VIIRS in the Dunhuang Test Site. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Ma, L.; Li, C.; Gao, C.; Wang, N.; Tang, L. Radiometric cross-calibration of Landsat-8/OLI and GF-1/PMS sensors using an instrumented sand site. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2018, 11, 3822–3829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ma, L.; Wang, N.; Qian, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Qiu, S.; Gao, C.-X.; Long, X.-X.; Li, C.-R. On-orbit radiometric calibration of the optical sensors on-board SuperView-1 satellite using three independent methods. Opt. Express 2020, 28, 11085–11105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Ma, L.; Tang, L.; Gao, C.; Qian, Y.; Wang, N.; Wang, X. A comprehensive calibration site for high resolution remote sensors dedicated to quantitative remote sensing and its applications. Natl. Remote Sens. Bull. 2021, 25, 198–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, J.; Zhou, X.; Wang, S. Study on spatiotemporal changes of fractional vegetation cover in Baotou City based on NDVI in the past 20 years. Grassl. Turf. 2024, 44, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Yang, J.; Che, H.; Li, X.; Xia, X. Verification for the satellite remote sensing products of aerosol optical depth in Taklimakan desert area. Clim. Environ. Res. 2012, 17, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, C.; Tan, K.; Wang, X.; Han, B.; Ge, S.; Du, P.; Wang, F. Radiometric cross-calibration of the ZY1-02D hyperspectral imager using the GF-5 AHSI imager. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Rao, K.; Wu, Z.; Wang, S.; Dai, Z.; Fang, R.; Wang, K. Radiometric cross-calibration of hyperspectral microsatellites using spectral homogeneity factor. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 2342–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czapla-Myers, J.S.; Thome, K.J.; Anderson, N.J.; Leigh, L.M.; Pinto, C.T.; Wenny, B.N. The ground-based absolute radiometric calibration of the Landsat 9 Operational Land Imager. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondeaux, G.; Steven, M.D.; Clark, J.A.; Mackay, G. La Crau: A European test site for remote sensing validation. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1998, 19, 2775–2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porwal, S.; Katiyar, S.K. Performance evaluation of various resampling techniques on IRS imagery. In Proceedings of the 2014 Seventh International Conference on Contemporary Computing (IC3), Noida, India, 7–9 August 2014; IEEE: Noida, India, 2014; pp. 489–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coburn, C.A.; Logie, G.S.J. Temporal dynamics of sand dune bidirectional reflectance characteristics for absolute radiometric calibration of optical remote sensing data. J. Appl. Rem. Sens. 2017, 12, 012006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Wu, P.; Ma, G.; Hu, Q.; Hu, X.; Wu, R.; Wang, Y.; Xu, H.; Chen, L.; Zhang, P. In-flight spectral response function retrieval of a multispectral radiometer based on the functional data analysis technique. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satellite Application Center for Ecology and Environment (SECEE). The Absolute Radiometric Calibration Coefficients for Domestic Civilian Land Observation Satellites in Orbit (2024). Available online: https://www.secmep.cn/xzzx/dbxs/ (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, T.; Zheng, T.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Yu, Y.; Li, L. On-Orbit Geometric Calibration and Performance Validation of the GaoFen-14 Stereo Mapping Satellite. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Jupp, D.; Qin, Y.; Gu, X.; Yu, T. Cross-calibration of the HSI sensor reflective solar bands using Hyperion data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2015, 53, 4127–4137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storch, T.; Honold, H.-P.; Chabrillat, S.; Habermeyer, M.; Tucker, P.; Brell, M.; Ohndorf, A.; Wirth, K.; Betz, M.; Kuchler, M.; et al. The EnMAP imaging spectroscopy mission towards operations. Remote Sens. Environ. 2023, 294, 113632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PARAMETER | HJ-2A/HSI | ZY1-02D/AHSI | GF-5B/AHSI | Landsat-9/OLI-2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orbit altitude (km) | 645 | 778 | 705 | 705 |

| Revisit period (days) | 41 | 55 | 51 | 16 |

| Ground sample distance (m) | VNIR: 48 SWIR: 96 | 30 | 30 | 30 (1–7,9) |

| Swath width (km) | 96 | 60 | 60 | 185 |

| Spectral range (nm) | 450–2500 | 400–2500 | 380–2500 | 430–2300 |

| Spectral resolution (nm) | VNIR: 4~24 SWIR: 12~87 | VNIR: 10 SWIR: 20 | VNIR: 5 SWIR: 10 | 20–200 |

| Spectral bands | 215 | 166 | 330 | 9 |

| Accuracy of the absolute radiometric calibration | -- | <7% | <5% | <5% |

| Accuracy of the relative radiometric calibration | <3% | <3% | <3% | <1% |

| Sites | Sensors | Dates | Times | Solar Zenith | Solar Azimuth | Satellite Zenith | Satellite Azimuth |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dunhuang | HJ-2A/HSI | 2 August 2024 | T05:08:01 | 24.14° | 156.76° | 1.00° | 164.57° |

| ZY1-02D/AHSI | 3 August 2024 | T04:37:11 | 27.26° | 140.07° | 9.57° | 280.35° | |

| Baotou | HJ-2A/HSI | 26 September 2024 | T04:10:43 | 42.75° | 171.18° | 5.34° | 110.50° |

| ZY1-02D/AHSI | 26 September 2024 | T03:29:06 | 44.84° | 157.11° | 0.36° | 174.43° | |

| Tak | HJ-2A/HSI | 26 September 2024 | T05:48:55 | 40.65° | 170.01° | 0.97° | 167.53° |

| ZY1-02D/AHSI | 26 September 2024 | T05:10:14 | 42.65° | 155.10° | 0.36° | 173.50° |

| Sites | Sensors | Dates | Times | Solar Zenith | Solar Azimuth | Satellite Zenith | Satellite Azimuth |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dunhuang | HJ-2A/HSI | 29 July 2024 | T05:11:10 | 23.21° | 155.85° | 5.38° | 110.39° |

| GF-5B/AHSI | 30 July 2024 | T04:45:00 | 25.95° | 142.37° | 0.09° | 194.05° | |

| Landsat-9/OLI-2 | 30 July 2024 | T04:25:41 | 28.78° | 133.31° | 0.21° | 183.47° | |

| Vegetation | HJ-2A/HSI | 20 August 2024 | T04:08:39 | 29.73° | 162.28° | 5.38° | 110.49° |

| GF-5B/AHSI | 23 August 2024 | T03:40:14 | 32.35° | 150.99° | 0.09° | 194.38° | |

| Landsat-9/OLI-2 | 18 August 2024 | T03:17:53 | 32.98° | 140.16° | 0.21° | 183.47° |

| Band Range | Methods | Dunhuang | Baotou | Tak | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VNIR | DG-SBAF(4σ) | 4.68% | 7.70% | 6.99% | 6.46% |

| DG-SBAF(FWHM) | 4.89% | 8.12% | 7.57% | 6.86% | |

| Traditional SBAF | 5.33% | 8.74% | 7.99% | 7.35% | |

| SWIR | DG-SBAF(4σ) | 7.75% | 9.79% | 8.48% | 8.67% |

| DG-SBAF(FWHM) | 8.08% | 10.14% | 9.02% | 9.08% | |

| Traditional SBAF | 8.40% | 10.46% | 9.62% | 9.49% |

| Band Range | Methods | Dunhuang | Baotou | Tak | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VNIR | DG-SBAF(4σ) | 0.0355 | 0.0374 | 0.0206 | 0.0312 |

| DG-SBAF(FWHM) | 0.0391 | 0.0408 | 0.0287 | 0.0362 | |

| Traditional SBAF | 0.0636 | 0.0653 | 0.0602 | 0.0630 | |

| SWIR | DG-SBAF(4σ) | 0.1053 | 0.1067 | 0.1137 | 0.1086 |

| DG-SBAF(FWHM) | 0.1089 | 0.1102 | 0.1197 | 0.1129 | |

| Traditional SBAF | 0.1186 | 0.1202 | 0.1297 | 0.1228 |

| Band Range | Methods | Dunhuang | Baotou | Tak | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VNIR | DG-SBAF(4σ) | 3.64° | 3.09° | 2.92° | 3.22° |

| DG-SBAF(FWHM) | 3.82° | 3.11° | 3.14° | 3.36° | |

| Traditional SBAF | 4.07° | 3.12° | 3.67° | 3.62° | |

| SWIR | DG-SBAF(4σ) | 4.00° | 3.46° | 3.90° | 3.79° |

| DG-SBAF(FWHM) | 4.04° | 3.48° | 3.90° | 3.81° | |

| Traditional SBAF | 4.34° | 3.60° | 4.26° | 4.07° |

| Band Range | Methods | Dunhuang | Baotou | Tak | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VNIR Dunhuang | DG-SBAF(4σ) | 4.08° | 4.82° | 4.04° | 4.31° |

| DG-SBAF(FWHM) | 4.14° | 4.84° | 4.21° | 4.40° | |

| Traditional SBAF | 4.24° | 4.85° | 4.41° | 4.50° | |

| VNIR Vegetation | DG-SBAF(4σ) | 6.82° | 5.90° | 5.78° | 6.12° |

| DG-SBAF(FWHM) | 6.84° | 5.92° | 5.82° | 6.19° | |

| Traditional SBAF | 6.97° | 5.93° | 5.87° | 6.26° |

| Band Range | Methods | Dunhuang | Baotou | Tak | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VNIR | DG-SBAF(4σ) | 3.79° | 4.23° | 4.48° | 4.17° |

| DG-SBAF(FWHM) | 3.80° | 4.27° | 4.51° | 4.19° | |

| Traditional SBAF | 4.03° | 4.33° | 4.69° | 4.35° | |

| SWIR | DG-SBAF(4σ) | 4.95° | 4.08° | 4.84° | 4.62° |

| DG-SBAF(FWHM) | 5.10° | 4.16° | 5.04° | 4.77° | |

| Traditional SBAF | 5.59° | 4.26° | 5.50° | 5.12° |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, C.; Gao, X.; Zhao, H.; Feng, X.; Cheng, J.; Hu, B.; Wang, S. A Dynamic Gaussian Modified Spectral Band Adjustment Factors Method for Radiometric Cross-Calibration of HJ-2A/HSI with ZY1-02D/AHSI. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3988. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243988

Yu C, Gao X, Zhao H, Feng X, Cheng J, Hu B, Wang S. A Dynamic Gaussian Modified Spectral Band Adjustment Factors Method for Radiometric Cross-Calibration of HJ-2A/HSI with ZY1-02D/AHSI. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):3988. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243988

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Can, Xiangyu Gao, Hang Zhao, Xiangpeng Feng, Juan Cheng, Bingliang Hu, and Shuang Wang. 2025. "A Dynamic Gaussian Modified Spectral Band Adjustment Factors Method for Radiometric Cross-Calibration of HJ-2A/HSI with ZY1-02D/AHSI" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 3988. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243988

APA StyleYu, C., Gao, X., Zhao, H., Feng, X., Cheng, J., Hu, B., & Wang, S. (2025). A Dynamic Gaussian Modified Spectral Band Adjustment Factors Method for Radiometric Cross-Calibration of HJ-2A/HSI with ZY1-02D/AHSI. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 3988. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243988