Multi-Scale Assessment and Prediction of Drought: A Case Study in the Arid Area of Northwest China

Highlights

- Warming in the Arid Area of Northwest China offsets the humidification effect caused by increased precipitation.

- Multi-model integration significantly reduces prediction variance and bias, substantially improving simulation accuracy. Multi-scale SPEI-based projections indicate a continued intensification of meteorological drought in the region.

- The counteracting effect of warming against precipitation-induced humidification reveals an increasingly warm-dry climate trend in arid Northwest China.

- The integration of multiple models provides a more robust and reliable approach for drought prediction, reveals the trend of persistent drought intensification, and offers scientific justification and urgency for formulating adaptive water allocation and drought mitigation strategies.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

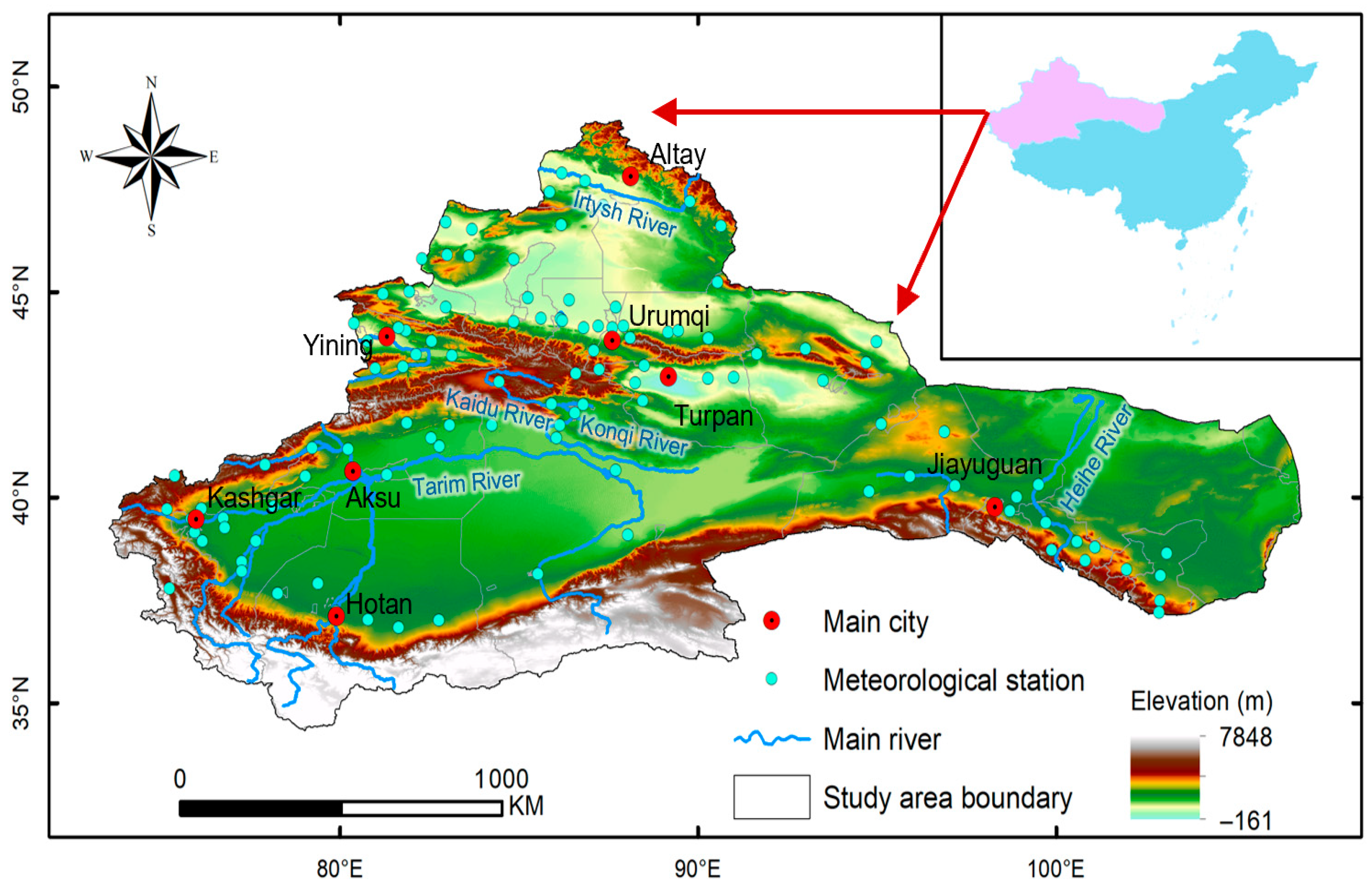

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Datasets

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. BEAST

2.3.2. SPEI

- (1)

- Calculate the climatic water balance, with the climatic water balance (Di) being the difference between precipitation (Pi) and potential evapotranspiration (PETi):

- (2)

- Establish the cumulative series of climatic water balance at different time scales:where k is the time scale (usually month) and n is the number of calculations.

- (3)

- Build a data series using the log-logistic probability density function fitting:where α is the scale coefficient, β is the shape coefficient, and γ is the origin parameter, which can be obtained by the L-moment parameter estimation method.

- (4)

- Transform the cumulative probability density into a standard normal distribution to obtain the corresponding SPEI time change sequence:where w = [−2ln(P)]1/2, when P ≤ 0.5, P = 1 − F(x); when P > 0.5, P = 1 − Pi, c0 = 2.515517; c1 = 0.802853; c2 = 0.010380; d1 = 1.432788; d2 = 0.189 269; d3 = 0.001308.

2.3.3. Elastic Network

2.3.4. Random Forest

2.3.5. Prophet with XGBoost

2.3.6. Stacking Ensemble Model

3. Results

3.1. Warming and Humidification Trend Based on Temperature and Precipitation

3.2. Meteorological Drought Intensification Based on Multi-Scale SPEI

3.3. Warming Offsets the Humidification Effect of Precipitation

3.4. Multi-Model Simulation and Prediction of SPEI

4. Discussion

4.1. Observational Evidence of Climate Warming and Wetting

4.2. Future Trends of Meteorological Drought

4.3. Innovation, Limitations, and Future Prospects

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qing, Y.; Wang, S.; Yang, Z.L.; Gentine, P. Soil Moisture−Atmosphere Feedbacks Have Triggered the Shifts from Drought to Pluvial Conditions since 1980. Commun. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Y.; Li, Z.; Chen, Y.N. The Spatiotemporal Evolution of Socioeconomic Drought in the Arid Area of Northwest China Based on the Water Poverty Index. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 401, 136719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Z.; Niu, J.; Guan, H.D.; Kang, S.Z. Three-Dimensional Linkage between Meteorological Drought and Vegetation Drought across China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 859, 160300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhao, H.; Wang, F.Q.; Yan, B.; Tang, L.; Du, Y.T.; Cui, L.B. Study on the Multi-Type Drought Propagation Process and Driving Factors on the Tibetan Plateau. J. Hydrol. 2024, 645, 132162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinoni, J.; Barbosa, P.; Bucchignani, E.; Cassano, J.; Cavazos, T.; Christensen, J.H.; Christensen, O.B.; Coppola, E.; Evans, J.; Geyer, B.; et al. Future Global Meteorological Drought Hot Spots: A Study Based on CORDEX Data. J. Clim. 2020, 33, 3635–3661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, J.; Joo, H.; Jung, J.; Lee, J.; Kim, S.; Kim, H.S. A Case Study: Bivariate Drought Identification on the Andong Dam, South Korea. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2021, 35, 549–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Tu, X.; Singh, V.P.; Chen, X.; Lin, K. Global Data Assessment and Analysis of Drought Characteristics Based on CMIP6. J. Hydrol. 2021, 6, 126091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, J. Future Global Socioeconomic Risk to Droughts Based on Estimates of Hazard, Exposure, and Vulnerability in a Changing Climate. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 751, 142159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Shi, H.; Fu, Q.; Ding, Y.; Li, T.; Liu, S. Investigating the Propagation from Meteorological to Hydrological Drought by Introducing the Nonlinear Dependence with Directed Information Transfer Index. Water Resour. Res. 2021, 57, e2021WR030028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.Q.; Wang, P.; Li, L.Q.; Fu, Q.; Ding, Y.B.; Chen, P.; Xue, P.; Wang, T.; Shi, H.Y. Recent development on drought propagation: A comprehensive review. J. Hydrol. 2024, 645, 132196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seneviratne, S.; Zhang, X.; Adnan, M.; Badi, W.; Dereczynski, C.; Luca, A.D.; Ghosh, S.; Iskandar, I.; Kossin, J.; Lewis, S.; et al. Weather and Climate Extreme Events in a Changing Climate. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis; IPCC, Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z.Y.; Duan, W.L.; Zou, S.; Zeng, Z.Z.; Chen, Y.N.; Feng, M.Q.; Qin, J.X.; Liu, Y.C. Spatiotemporal Characteristics of Meteorological Drought Events in 34 Major Global River Basins during 1901–2021. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 921, 170913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.Y.; Ma, E.Z.; Zhou, Z.Q.; Zou, Y.G.; Cao, Z.D.; Cai, H.J.; Li, C.; Yan, Y.H.; Chen, Y. Detecting the Non-separable Causality in Soil Moisture-Precipitation Coupling with Convergent Cross-Mapping. Water Resour. Res. 2024, 60, e2023WR034616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.Y.; Zhu, T.J.; Zhou, Z.Q.; Cai, H.J.; Cao, Z.D. Detecting Nonlinear Information about Drought Propagation Time and Rate with Nonlinear Dynamic System and Chaos Theory. J. Hydrol. 2023, 623, 129810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hao, Z.C.; Singh, V.P.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, S.F.; Xu, Y.; Hao, F.H. Drought Propagation under Global Warming: Characteristics, Approaches, Processes, and Controlling Factors. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 156021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Huang, S.; Huang, Q.; Liu, D.; Leng, G.; Yang, H.; Duan, W.; Li, J.; Bai, Q.; Peng, J. Analysis of Vegetation Vulnerability Dynamics and Driving Forces to Multiple Drought Stresses in a Changing Environment. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warter, M.M.; Singer, M.B.; Cuthbert, M.O.; Roberts, D.; Caylor, K.K.; Sabathier, R.; Stella, J. Drought Onset and Propagation into Soil Moisture and Grassland Vegetation Responses during the 2012–2019 Major Drought in Southern California. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2021, 25, 3713–3729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.J.; Zhang, B.Q.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Tian, L.; Kunstmann, H.; He, C.S. Identifying Spatiotemporal Propagation of Droughts in the Agro-Pastoral Ecotone of Northern China with Long-Term WRF Simulations. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2023, 336, 109474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Quiring, S.M.; Peña-Gallardo, M.; Yuan, S.S.; Domínguez-Castro, F. A Review of Environmental Droughts: Increased Risk under Global Warming? Earth-Sci. Rev. 2020, 201, 102953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, R.; Huang, G.; Wang, F.; Tian, C.; Wu, X. Observations over a Century Underscore an Increasing Likelihood of Compound Dry-hot Events in China. Earths Future 2024, 12, e2024EF004546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Yin, H.; He, H.; Li, Y. Dynamic-LSTM Hybrid Models to Improve Seasonal Drought Predictions over China. J. Hydrol. 2022, 615, 128706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, P.; Su, R.; Wu, G.; Xue, L.; Zhang, Z.; Fang, H.; Gao, R.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, D. Projecting Future Wetland Dynamics Under Climate Change and Land Use Pressure: A Machine Learning Approach Using Remote Sensing and Markov Chain Modeling. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Yu, G.; Tian, R.; Sun, Y. Application of a Hybrid CEEMD-LSTM Model Based on the Standardized Precipitation Index for Drought Forecasting: The Case of the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabzipour, B.; Arsenault, R.; Troin, M.; Martel, J.-L.; Brissette, F.; Brunet, F.; Mai, J. Comparing a long short-term memory (LSTM) neural network with a physically-based hydrological model for streamflow forecasting over a Canadian catchment. J. Hydrol. 2023, 627, 130380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, Z.; Shangguan, W.; Li, L.; Yao, Y.; Yu, F. Improved daily SMAP satellite soil moisture prediction over China using deep learning model with transfer learning. J. Hydrol. 2021, 600, 126698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majhi, B.; Naidu, D.; Mishra, A.P.; Satapathy, S.C. Improved Prediction of Daily Pan Evaporation Using Deep-LSTM Model. Neural Comput. Appl. 2020, 32, 7823–7838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silini, R.; Masoller, C. Fast and Effective Pseudo Transfer Entropy for Bivariate Data-Driven Causal Inference. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 8423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.Y.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Liu, S.N.; Cai, H.J.; Zhou, Z.Q. A New Perspective on Drought Propagation: Causality. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2022, 49, e2021GL096758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Li, R.; Hu, Q.; Niu, C.; Liu, W.; Lu, W. Contrastive Learning Network Based on Causal Attention for Fine-Grained Ship Classification in Remote Sensing Scenarios. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Lin, H.; Long, J.; Mu, G.; Li, S.; Lv, Y. Individual Tree-Level Biomass Mapping in Chinese Coniferous Plantation Forests Using Multimodal UAV Remote Sensing Approach Integrating Deep Learning and Machine Learning. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Fu, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Zhai, W.; Sun, X.; Ren, Y.; Pan, D. Modeling Potential Arsenic Enrichment and Distribution Using Stacking Ensemble Learning in the Lower Yellow River Plain, China. J. Hydrol. 2023, 625, 129985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Feng, C.; Yu, P.; Li, K.; Chen, X. Gradient Boosting Decision Tree in the Prediction of NOx Emission of Waste Incineration. Energy 2023, 264, 126174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ching, P.M.L.; Zou, X.; Wu, D.; So, R.H.Y.; Chen, G.H. Development of a Wide-Range Soft Sensor for Predicting Wastewater BOD Using an eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) Machine. Environ. Res. 2022, 210, 112953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.X.; Zhao, M.Y.; Dong, Y.; Cao, X.; Sun, H.X. Hybrid Model with Secondary Decomposition, Random Forest Algorithm, Clustering Analysis and Long Short Memory Network Principal Computing for Short-Term Wind Power Forecasting on Multiple Scales. Energy 2021, 221, 119848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.H.; Zhang, Q.; Ding, Y.; Huang, H.P. Application of a Hybrid ARIMA–SVR Model Based on the SPI for the Forecast of Drought—A Case Study in Henan Province, China. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2020, 59, 1239–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.Y.; Yu, Y.; Yang, M.L.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, L.Y.; Guo, Z.K.; Zhang, J.; Mailik, I.; Malgorzata, W.; Yu, R.D.; et al. Investigating the Effect of Climate Change on Drought Propagation in the Tarim River Basin Using Multi-Model Ensemble Projections. Atmosphere 2023, 15, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.S.; Chen, Y.N.; Chen, Y.P.; Duan, W.L.; Wang, J.Y.; Wang, X. Characteristics of Dry and Wet Changes and Future Trends in the Tarim River Basin Based on the Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index. Water 2024, 16, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.P.; Zhang, L.F.; He, Y.; Zhang, Y.L.; Chen, Y.; Yao, S.; Yang, W.; Sun, Q. Effects and Contributions of Meteorological Drought on Agricultural Drought under Different Climatic Zones and Vegetation Types in Northwest China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 821, 153270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Li, Y.; Xue, W.; Shahabi, H.; Li, S.; Hong, H.; Wang, X.; Bian, H.; Zhang, S.; Pradhan, B.; et al. Modeling Flood Susceptibility Using Data-Driven Approaches of Naïve Bayes Tree, Alternating Decision Tree, and Random Forest Methods. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 701, 134979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Toman, E.M.; Chen, G.; Shao, G.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhao, K.; Feng, Y. Mapping Fine-Scale Human Disturbances in a Working Landscape with Landsat Time Series on Google Earth Engine. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2021, 176, 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Beguería, S.; López-Moreno, J.I. A Multiscalar Drought Index Sensitive to Global Warming: The Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index. J. Clim. 2010, 23, 1696–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.; Huang, T.; Liu, Z.; Bao, L.; Guo, B.; Yu, Z.; Feng, Z.; Luo, H.; Ou, G. Improving Forest Above-Ground Biomass Estimation Accuracy Using Multi-Source Remote Sensing and Optimized Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator Variable Selection Method. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, J.K.; Narasimhan, B.; Hastie, T. Elastic Net Regularization Paths for All Generalized Linear Models. J. Stat. Softw. 2023, 106, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar]

- Charoenkwan, P.; Chiangjong, W.; Nantasenamat, C.; Hasan, M.M.; Manavalan, B.; Shoombuatong, W. StackIL6: A Stacking Ensemble Model for Improving the Prediction of IL-6 Inducing Peptides. Brief. Bioinform. 2021, 22, bbab172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzarini, R.; Tianfield, H.; Charissis, V. A Stacking Ensemble of Deep Learning Models for IoT Intrusion Detection. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2023, 279, 110941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Xie, T.; Yang, Y.; Chen, S.; Chen, F.; Huang, W.; Chen, J. Discussion of the “Warming and Wetting” Trend and Its Future Variation in the Drylands of Northwest China under Global Warming. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2023, 66, 1241–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, H.H. Temporal and Spatial Variations of Precipitation Change from Southeast to Northwest China during the Period 1961–2017. Water 2020, 12, 2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.Q.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Y.N.; Yu, X.J.; Zhang, R.B. Multi-Scale Assessments of Droughts: A Case Study in Xinjiang, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 630, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Lee, S.Y.; Wen, X.H.; Ji, Z.M.; Lin, L.; Wei, Z.G.; Zheng, Z.Y.; Xu, D.Y.; Dong, W.J. Extreme climate changes over three major river basins in China as seen in CMIP5 and CMIP6. Clim. Dyn. 2021, 57, 1187–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Su, B.; Tao, H.; Wang, Y.; Huang, J.; Li, Z.; Jiang, T. Spatio-Temporal Variations of Dryness/Wetness over Northwest China under Different SSPs-RCPs. Atmos. Res. 2021, 259, 105672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Xia, J.; Zhan, C.S.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Hu, S. Discrete Wavelet Transform-Based Investigation into the Variability of Standardized Precipitation Index in Northwest China during 1960–2014. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2018, 132, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Lai, C.; Zeng, Z.; Zhong, R.; Chen, X.; Zhou, X.; Wang, M. Does Drought in China Show a Significant Decreasing Trend from 1961 to 2009? Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 579, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Liu, C.; Cao, J.Q.; Chen, J.H.; Feng, S. Changes of Hydroclimatic Patterns in China in the Present Day and Future. Sci. Bull. 2020, 65, 1061–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trepel, J.; le Roux, E.; Abraham, A.J.; Buitenwerf, R.; Kamp, J.; Kristensen, J.A.; Tietje, M.; Lundgren, E.J.; Svenning, J.C. Meta-Analysis Shows that Wild Large Herbivores Shape Ecosystem Properties and Promote Spatial Heterogeneity. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 8, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Schwarz, L.; Rosenthal, N.; Marlier, M.E.; Benmarhnia, T. Exploring Spatial Heterogeneity in Synergistic Effects of Compound Climate Hazards: Extreme Heat and Wildfire Smoke on Cardiorespiratory Hospitalizations in California. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadj7264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, A.; Pal, S.C. Spatio-Temporal Variation of Meteorological, Hydrological and Agricultural Drought Vulnerability: Insights from Statistical, Machine Learning and Wavelet Analysis. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 27, 101380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.P.; Cai, Y.P.; Cong, P.T.; Xie, Y.L.; Chen, W.J.; Cai, J.Y.; Bai, X.Y. Quantitation of Meteorological, Hydrological and Agricultural Drought under Climate Change in the East River Basin of South China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 158, 111304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.Q.; Shangguan, W.; Liu, J.J.; Dong, W.Z.; Wu, D.Y. Assessing Meteorological and Agricultural Drought Characteristics and Drought Propagation in Guangdong, China. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2024, 51, 101611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuğrul, T.; Hınıs, M.A.; Oruç, S. Comparison of LSTM and SVM Methods through Wavelet Decomposition in Drought Forecasting. Earth Sci. Inform. 2025, 18, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Martínez, F.; Márquez-Grajales, A.; Valdés-Rodríguez, O.A.; Palacios-Wassenaar, O.M.; Pérez-Castro, N. Prediction of Agricultural Drought Behavior Using the Long Short-Term Memory Network (LSTM) in the Central Area of the Gulf of Mexico. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2024, 155, 7887–7907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, B.B.; Gaurav, A.; Attar, R.W.; Arya, V.; Bansal, S.; Alhomoud, A.; Chui, K.T. Advance Drought Prediction through Rainfall Forecasting with Hybrid Deep Learning Model. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 30459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Rating | Drought Type | SPEI |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mild drought | −1 < SPEI ≤ −0.5 |

| 2 | Moderate drought | −1.5 < SPEI ≤ −1 |

| 3 | Severe drought | −2 < SPEI ≤ −1.5 |

| 4 | Extreme drought | SPEI ≤ −2 |

| Index | Equation | Range of Index | Optimum Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| NSE | [0, 1] | 1 | |

| MAE | [0, +∞) | 0 | |

| RMSE | [0, +∞) | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pan, T.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Feng, M. Multi-Scale Assessment and Prediction of Drought: A Case Study in the Arid Area of Northwest China. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3985. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243985

Pan T, Wang Y, Chen Y, Wang J, Feng M. Multi-Scale Assessment and Prediction of Drought: A Case Study in the Arid Area of Northwest China. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):3985. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243985

Chicago/Turabian StylePan, Tingting, Yang Wang, Yaning Chen, Jiayou Wang, and Meiqing Feng. 2025. "Multi-Scale Assessment and Prediction of Drought: A Case Study in the Arid Area of Northwest China" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 3985. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243985

APA StylePan, T., Wang, Y., Chen, Y., Wang, J., & Feng, M. (2025). Multi-Scale Assessment and Prediction of Drought: A Case Study in the Arid Area of Northwest China. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 3985. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243985