Enhanced Calculation of

Highlights

- This paper presents a new approach for deriving directly from the standard satellite product, using a global database spanning diverse marine optical conditions. Among the tested methods, a power-law regression provided the best performance.

- The resulting model is accurate and robust, making it suitable for large-scale marine monitoring programs

- The best performing model is ready for operational implementation in monitoring programs to produce consistent time series.

- This approach provides a reliable basis for studying water quality, phytoplankton dynamics, and other events affecting the light field in the water. It can be operationally estimated to support satellite monitoring programs and thus provide high-quality data for marine management programs.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Databases

2.1.1. Considerations for In Situ Data

- (1)

- The first method was when the data was already published in the consulted database. In this case these were used directly.

- (2)

- The second method was where the stations had data on a downwelling irradiance PAR , profile. In these cases, the Equation (1) [6] was usedwhere the dependent variable is the natural logarithm of and the independent variable is the depth at which such irradiance was measured.

- (3)

- The third method was when the station had a profile of spectral downwelling irradiance (). In this case to obtain the , between 400 and 700 nm were integrated; then, Equation (1) was applied.

- (4)

- The fourth method was when the station reported Secchi disk depth readings (). In these cases, were used the approaches reports by Castillo-Ramírez et al. [10].

- (1)

- The first method was when the data was already published in the consulted database. In this case these were used directly.

- (2)

- The second method was when the station had a profile of spectral downwelling irradiance (). In this case the profiles were selected. If the exactly the 490 nm profile was not available, the nearest value was used, provided it did not exceed a difference of ±10 nm. was estimated using Equation (1) [6].

2.1.2. Considerations for Satellite Data

2.2. Numerical Procedures

2.3. Empirical Models

Statistical Significance for the Generated Empirical Models

2.4. Model Validation

3. Results

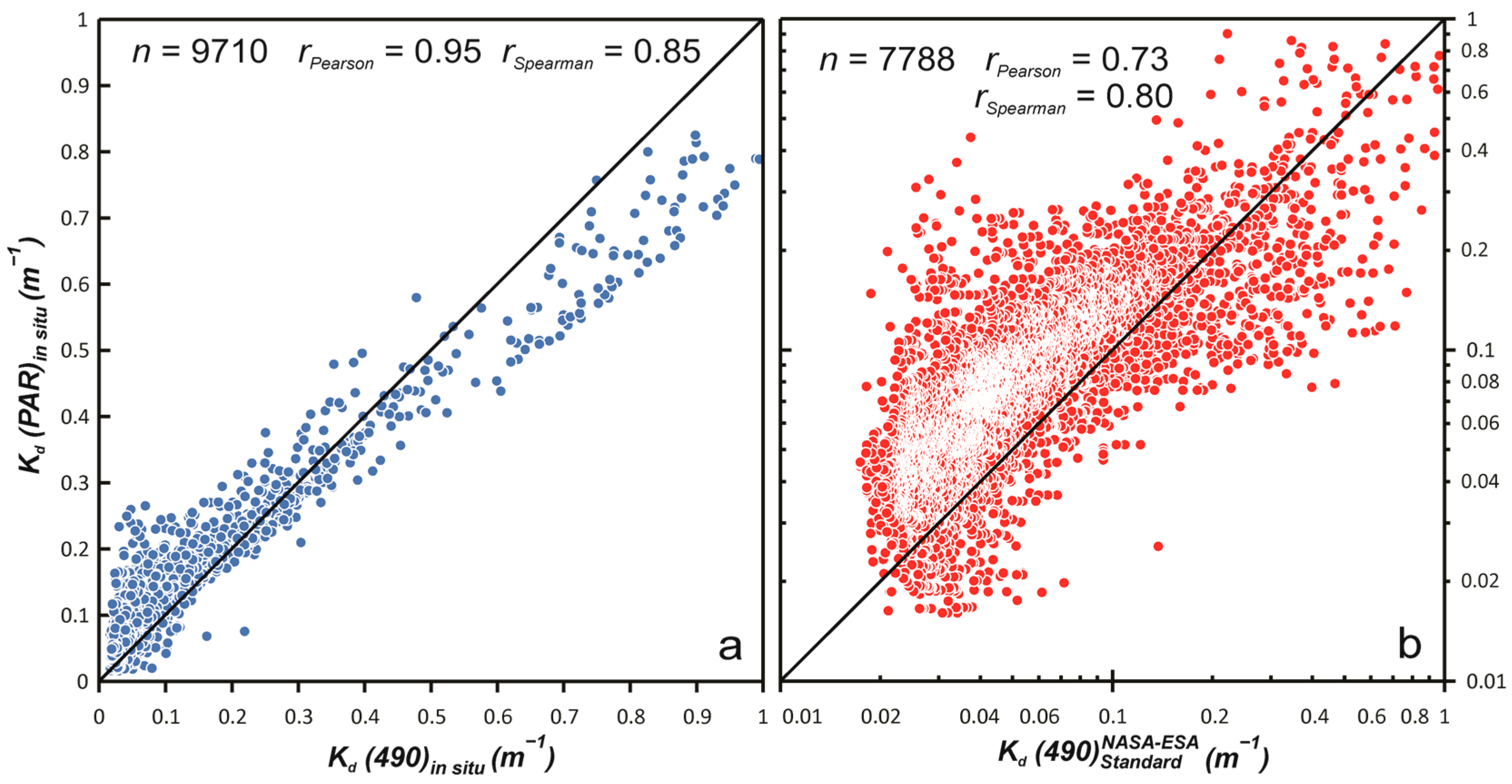

3.1. Database

3.2. Models

3.2.1. Versions

3.2.2. Models Validation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AOP | Apparent Optical Properties |

| BGC-Argo | Biogeochemical-Argo |

| BIAS | Bias Analysis |

| Coefficient associated with the variable independent k | |

| CAR/RCU | Cartagena Convention and the Regional Coordination Unit |

| CONABIO | National Commission for the Knowledge and Use of Biodiversity |

| Covariance of the a and b | |

| Covariance of the ranks of a and b | |

| CZCS | Coastal Zone Color Scanner |

| Downwelling irradiance just below the sea surface | |

| Downwelling PAR irradiance | |

| Downwelling spectral irradiance | |

| ES | Ecosystem services |

| Calculated F-test value to test the overall significance of each model | |

| GEF | Global Environment Facility |

| GLO | Global Area Coverage |

| Integrated Absolute Residuals | |

| IV | Independent variable |

| Diffuse light attenuation coefficient | |

| Diffuse light attenuation coefficient of optically pure seawater | |

| Diffuse attenuation coefficient of photosynthetically active radiation | |

| Diffuse attenuation coefficient of photosynthetically available radiation in situ data | |

| Diffuse attenuation coefficient of photosynthetically active radiation modeling | |

| Diffuse attenuation coefficient at 490 nm coefficient | |

| Diffuse attenuation coefficient at 490 nm coefficient in situ data | |

| satellite standard data | |

| recalculation of according with Begouen-Demeaux et al. [24] | |

| L2 | Level 2 |

| L3 | Level 3 |

| LAC | Local Area Coverage |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| MAPE | Mean Absolute Percentage Error |

| MERIS | Medium Resolution Imaging Spectrometer |

| MLAC | Merged Local Area Coverage |

| MODIS | Moderate-Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer |

| MPI | Model Performance Index |

| NESA | NASA-ESA Inspired Ocean Color Model |

| NOAA | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration |

| NOMAD | NASA bio-Optical Marine Algorithm Dataset |

| OLCI | Ocean and Land Colour Instrument |

| PACE | Plankton, Aerosol, Cloud, ocean Ecosystem |

| PAR | Photosynthetically Active Radiation |

| POPEYE | Phytoplankton Ecology Team of the UABC |

| Power | Power Regression Model |

| R2 | Coefficient of determination |

| Individual absolute ranks of | |

| Individual ranks for | |

| RMSD | Root Mean Square Deviation |

| Individual ranks for | |

| Pearson’s correlation coefficient | |

| Spearman’s correlation coefficient | |

| SeaBASS | SeaWiFS Bio-optical Archive and Storage System |

| SeaWiFS | Sea-viewing Wide Field-of-view Sensor |

| SECIHTI | Secretary of Science, Humanities, Technology and Innovation |

| Standard error of the coefficient | |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals |

| SEMARNAT | Secretary of Environment and Natural Resources |

| SIMAR | Coastal Marine Information and Analysis System |

| Standard deviations of j | |

| Standard deviation of the ranks of j | |

| SWM | Slope Weighting Model |

| UABC | Autonomous University of Baja California |

| UNEP | United Nations Environmental Programme |

| VIIRS | Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite |

| Secchi Disk depth |

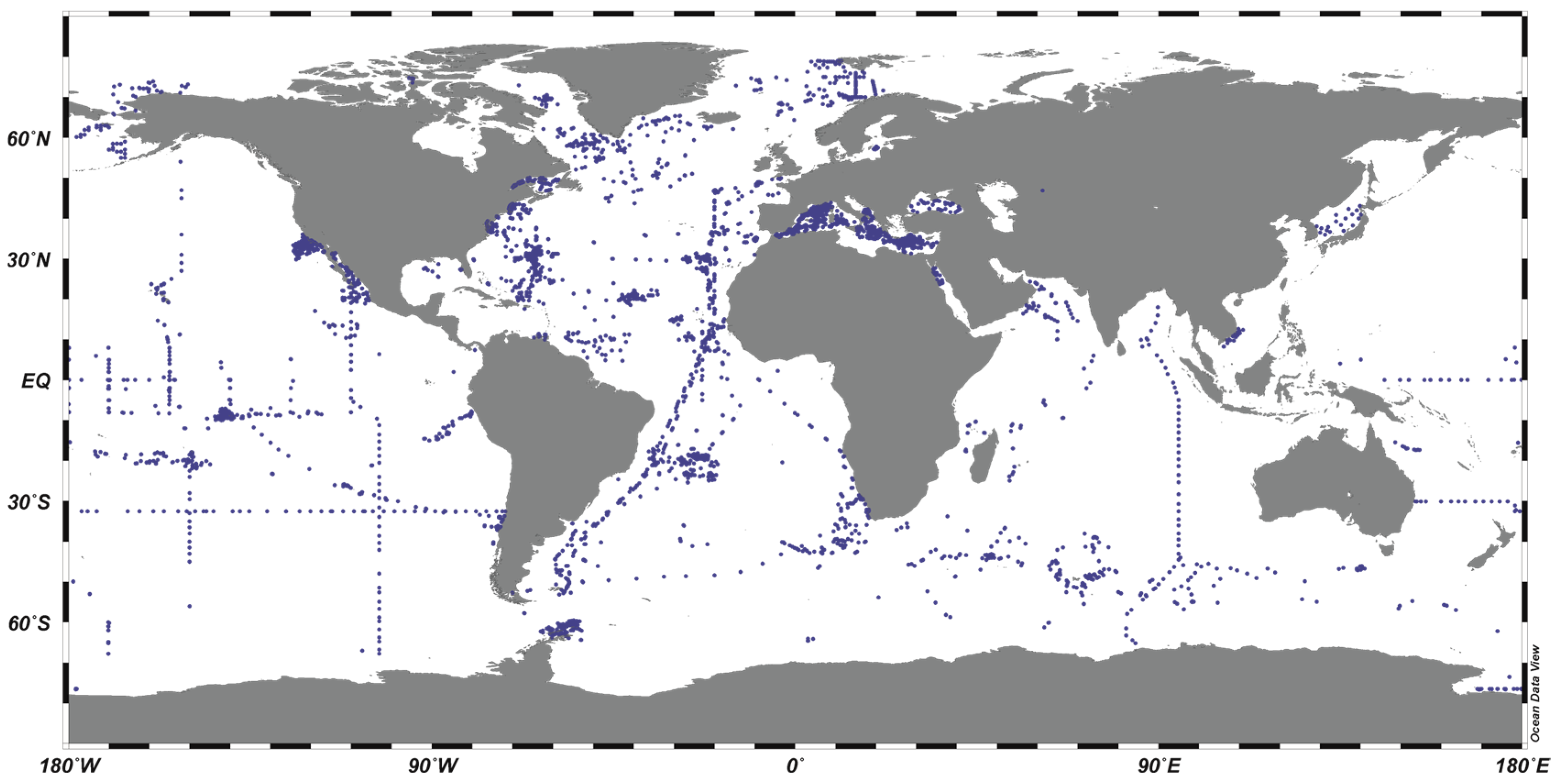

Appendix A. Global Distribution of Stations with Data

Appendix B

| Model | IV | RMSD | BIAS | MAPE | MPI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear | 0.0485 | 0.0018 | 32.329 | 0.7593 | |

| Power | 0.0462 | 0.0057 | 26.856 | 0.8704 | |

| NESA | 0.0483 | 0.0083 | 25.825 | 0.8333 | |

| Morel et al. [14] | 0.0527 | 0.0216 | 44.487 | 0.2407 | |

| Pierson et al. [15] | 0.0485 | 0.0649 | 126.949 | 0.2963 | |

| Pierson et al. [15] | 0.0473 | 0.0094 | 35.672 | 0.6759 | |

| Wang et al. [16] | 0.0495 | 0.0239 | 36.811 | 0.4537 | |

| Saulquin et al. [18] | 0.0505 | 0.0098 | 29.551 | 0.5648 | |

| SWM [37,38] | 0.0519 | 0.0284 | 43.185 | 0.2685 | |

| Linear | 0.0529 | 0.0002 | 31.853 | 0.5463 | |

| Power | 0.0494 | 0.0042 | 27.032 | 0.7593 | |

| NESA | 0.0506 | 0.0045 | 26.991 | 0.6574 | |

| Morel et al. [14] | 0.0517 | 0.0098 | 34.766 | 0.4630 | |

| Pierson et al. [15] | 0.0524 | 0.0593 | 122.131 | 0.1019 | |

| Pierson et al. [15] | 0.0487 | 0.0004 | 30.166 | 0.8056 | |

| Wang et al. [16] | 0.0506 | 0.0320 | 41.253 | 0.3148 | |

| Saulquin et al. [18] | 0.0504 | 0.0192 | 31.726 | 0.4907 | |

| SWM [37,38] | 0.0520 | 0.0366 | 47.946 | 0.1667 | |

| Linear | 0.0504 | 0.0020 | 30.680 | 0.6667 | |

| Power | 0.0600 | 0.0405 | 67.424 | 0.1019 | |

| NESA | 0.0488 | 0.0077 | 26.199 | 0.7778 | |

| Morel et al. [14] | 0.0488 | 0.0179 | 45.979 | 0.4630 | |

| Pierson et al. [15] | 0.0525 | 0.0612 | 126.953 | 0.0648 | |

| Pierson et al. [15] | 0.0482 | 0.0056 | 36.846 | 0.7037 | |

| Wang et al. [16] | 0.0492 | 0.0288 | 35.571 | 0.4815 | |

| Saulquin et al. [18] | 0.0487 | 0.0147 | 27.793 | 0.6944 | |

| SWM [37,38] | 0.0497 | 0.0339 | 41.817 | 0.3426 | |

| Linear | 0.0512 | 0.0016 | 31.434 | 0.6204 | |

| Power | 0.0682 | 0.0555 | 84.859 | 0.0741 | |

| NESA | 0.0488 | 0.0062 | 26.544 | 0.7685 | |

| Morel et al. [14] | 0.0499 | 0.0190 | 46.377 | 0.3704 | |

| Pierson et al. [15] | 0.0519 | 0.0620 | 127.223 | 0.0741 | |

| Pierson et al. [15] | 0.0483 | 0.0065 | 37.069 | 0.6481 | |

| Wang et al. [16] | 0.0497 | 0.0277 | 35.651 | 0.4537 | |

| Saulquin et al. [18] | 0.0495 | 0.0135 | 27.952 | 0.6296 | |

| SWM [37,38] | 0.0506 | 0.0327 | 41.932 | 0.2963 |

References

- UN (United Nations). Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/es/development-agenda/ (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Santamaría-del-Ángel, E.; Sebastia-Frasquet, M.T.; Millán-Nuñez, R.; González-Silvera, A.; Cajal-Medrano, R. Anthropocentric BIAS in Management Policies. Are We Efficiently Monitoring Our Ecosystems. In Coastal Ecosystems: Experiences and Recommendations for Environmental Monitoring Programs; Sebastia-Frasquet, M.T., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Häder, D.-P.; Banaszak, A.T.; Villafañe, V.E.; Narvarte, M.A.; González, R.A.; Helbling, E.W. Anthropogenic Pollution of Aquatic Ecosystems: Emerging Problems with Global Implications. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 713, 136586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojiri, A.; Zhou, J.L.; Robinson, B.; Ohashi, A.; Ozaki, N.; Kindaichi, T.; Farraji, H.; Vakili, M. Pesticides in Aquatic Environments and Their Removal by Adsorption Methods. Chemosphere 2020, 253, 126646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaría-del-Ángel, E.; Soto, I.; Millán-Núñez, R.; González, A.; Wolny, J.; Cerdeira-Estrada, S.; Cajal-Medrano, R.; Muller, F.; Padilla-Rosas, Y.X.S.; Mercado-Santana, A. Phytoplankton Blooms: New Initiative Using Marine Optics as a Basis for Monitoring Programs. In Coastal Ecosystems: Experiences and Recommendations for Environmental Monitoring Programs; Sebastia-Frasquet, M.T., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 57–88. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk, J.T.O. Light and Photosynthesis in Aquatic Ecosystems, 3rd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; p. 649. ISBN 978-1-139-16821-2. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Z.; Du, K.; Arnone, R.; Liew, S.; Penta, B. Penetration of Solar Radiation in the Upper Ocean: A Numerical Model for Oceanic and Coastal Waters. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2005, 110, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Lee, Z.; Ondrusek, M.; Kahru, M. Attenuation Coefficient of Usable Solar Radiation of the Global Oceans. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2016, 121, 3228–3236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, E.T.; Walve, J.; Andersson, A.; Karlson, B.; Kratzer, S. The Effect of Optical Properties on Secchi Depth and Implications for Eutrophication Management. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 5, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Ramírez, A.; Santamaría-del-Ángel, E.; González-Silvera, A.; Frouin, R.; Sebastiá-Frasquet, M.T.; Tan, J.; Lopez-Calderon, J.; Sánchez-Velasco, L.; Enríquez-Paredes, L. A New Algorithm to Estimate Diffuse Attenuation Coefficient from Secchi Disk Depth. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IOCCG. Uncertainties in Ocean Colour Remote Sensing; Mélin, F., Ed.; IOCCG Report Series, No. 18; International Ocean Colour Coordinating Group (IOCCG): Dartmouth, NS, Canada, 2019; ISBN 978-1-896246-68-0. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, J.L. SeaWiFS Algorithm for the Diffuse Attenuation Coefficient, K(490), Using Water-Leaving Radiances at 490 and 555 nm. In SeaWiFS Postlaunch Calibration and Validation Analyses; Standford, B.H., Ed.; NASA Goddard Space Flight Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; Volume 3, pp. 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Mobley, C.D. Light and Water: Radiative Transfer in Natural Waters; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994; p. 592. [Google Scholar]

- Morel, A.; Huot, Y.; Gentili, B.; Werdell, P.J.; Hooker, S.B.; Franz, B.A. Examining the Consistency of Products Derived from Various Ocean Color Sensors in Open Ocean (Case 1) Waters in the Perspective of a Multi-Sensor Approach. Remote Sens. Environ. 2007, 111, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierson, D.C.; Kratzer, S.; Strömbeck, N.; Håkansson, B. Relationship between the Attenuation of Downwelling Irradiance at 490 Nm with the Attenuation of PAR (400 nm–700 nm) in the Baltic Sea. Remote Sens. Environ. 2008, 112, 668–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Son, S.; Harding, L.W., Jr. Retrieval of Diffuse Attenuation Coefficient in the Chesapeake Bay and Turbid Ocean Regions for Satellite Ocean Color Applications. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2009, 114, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, S.; Lee, Z.; Wei, G. Characterization of MODIS-Derived Euphotic Zone Depth: Results for the China Sea. Remote Sens. Environ. 2011, 115, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saulquin, B.; Hamdi, A.; Gohin, F.; Populus, J.; Mangin, A.; d’Andon, O.F. Estimation of the Diffuse Attenuation Coefficient KdPAR Using MERIS and Application to Seabed Habitat Mapping. Remote Sens. Environ. 2013, 128, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerlov, N.G. Marine Optics, 2nd ed.; American Elsevier Publishing Company Incorporation: New York, NY, USA, 1976; Volume 14, ISBN 978-0-08-087050-2. [Google Scholar]

- Solonenko, M.G.; Mobley, C.D. Inherent Optical Properties of Jerlov Water Types. Appl. Opt. 2015, 54, 5392–5401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werdell, P.J.; Bailey, S.; Fargion, G.; Pietras, C.; Knobelspiesse, K.; Feldman, G.; McClain, C. Unique Data Repository Facilitates Ocean Color Satellite Validation. Eos. Trans. AGU 2003, 84, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werdell, P.J.; Bailey, S.W. An Improved In-Situ Bio-Optical Data Set for Ocean Color Algorithm Development and Satellite Data Product Validation. Remote Sens. Environ. 2005, 98, 122–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tara Oceans Consortium, Coordinators; Tara Oceans Expedition, Participants. Environmental Context of All Samples from the Tara Oceans Expedition (2009–2013), about Mesoscale Features [Dataset]. PANGAEA 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begouen-Demeaux, C.; Boss, E.; Tan, J.; Frouin, R. Algorithms to Retrieve the Spectral Diffuse Attenuation Coefficient of Light in the Ocean from Remote Sensing. Opt. Express 2024, 32, 2507–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preisendorfer, R.W. Secchi Disk Science: Visual Optics of Natural Waters. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1986, 31, 909–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Ramírez, A.; Santamaría-del-Ángel, E.; González-Silvera, A.; Aguilar-Maldonado, J.; Lopez-Calderon, J.; Sebastiá-Frasquet, M.-T. Use of Digital Images as a Low-Cost System to Estimate Surface Optical Parameters in the Ocean. Sensors 2023, 23, 3199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NASA Ocean Color Web. Available online: https://oceancolor.gsfc.nasa.gov/ (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Kahru, M.; Di Lorenzo, E.; Manzano-Sarabia, M.; Mitchell, B.G. Spatial and Temporal Statistics of Sea Surface Temperature and Chlorophyll Fronts in the California Current. J. Plankton Res. 2012, 34, 749–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahru, M.; Kudela, R.M.; Anderson, C.R.; Mitchell, B.G. Optimized Merger of Ocean Chlorophyll Algorithms of MODIS-Aqua and VIIRS. GRSL 2015, 12, 2282–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaría-del-Ángel, E.; Millan-Nuñez, R.; Gonzalez-Silvera, A.; Cajal, R. Comparison of In Situ and Remotely-Sensed Chl-a Concentrations: A Statistical Examination of the Match-up Approach. In Handbook of Satellite Remote Sensing Image Interpretation: Applications for Marine Living Resources Conservation and Management; Morales, J., Stuart, V., Platt, T., Sathyendranath, S., Eds.; EU PRESPO and IOCCG: Dartmouth, NS, Canada, 2011; pp. 241–260. [Google Scholar]

- Perdices, M. Null Hypothesis Significance Testing, p-Values, Effects Sizes and Confidence Intervals. Brain Impair. 2018, 19, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, L. A Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient Based Decision Tree and Its Parallel Implementation. Inf. Sci. 2018, 435, 40–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnsworth, D.L.; Triola, M.F. Review of Elementary Statistics. Technometrics 1990, 32, 456–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokoska, S.; Nevison, C. Critical Values For Spearman’s Rank Correlation Coefficient. In Statistical Tables and Formulae; Kokoska, S., Nevison, C., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1989; p. 86. ISBN 978-1-4613-9629-1. [Google Scholar]

- IOCCG. Synergy between Ocean Colour and Biogeochemical/Ecosystem Models; Dutkiewicz, S., Ed.; IOCCG Report Series, No. 19; International Ocean Colour Coordinating Group (IOCCG): Dartmouth, NS, Canada, 2020; p. 184. [Google Scholar]

- Luijken, K.; Wynants, L.; van Smeden, M.; Calster, B.V.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Groenwold, R.H.H.; Timmerman, D.; Bourne, T.; Ukaegbu, C. Changing Predictor Measurement Procedures Affected the Performance of Prediction Models in Clinical Examples. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2020, 119, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kratzer, S.; Håkansson, B.; Sahlin, C. Assessing Secchi and Photic Zone Depth in the Baltic Sea from Satellite Data. Ambio 2003, 32, 577–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Chen, C.; Zhan, H.; Xu, D. Remotely-Sensed Estimation of the Euphotic Depth in the Northern South China Sea. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Barcelona, Spain, 23–28 July 2007; pp. 917–920. [Google Scholar]

- Araveeporn, A. Improved Probability-Weighted Moments and Two-Stage Order Statistics Methods of Generalized Extreme Value Distribution. Mathematics 2025, 13, 2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jui, J.J.; Molla, M.M.I.; Ahmad, M.A.; Hettiarachchi, I.T. Recent Advances and Applications of the Multi-Verse Optimiser Algorithm: A Survey from 2020 to 2024. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2025, 32, 4491–4524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcoxon, F. Individual Comparisons by Ranking Methods. Biom. Bull. 1945, 1, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaría-del-Ángel, E.; Millán-Núñez, R.; De-Peña-Nettel, G. Effect of Turbidity on Primary Productivity at Two Stations in the Area of the Colorado River Delta. Cienc. Mar. 1996, 22, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Millán-Nuñez, R.; Santamaría-del-Ángel, E.; Cajal-Medrano, R.; Barocio-León, O.A. The Colorado River Delta: A High Primary Productivity Ecosystem. Cienc. Mar. 1999, 25, 509–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bastidas-Salamanca, M.; Gonzalez-Silvera, A.; Millán-Núñez, R.; Santamaria-del-Angel, E.; Frouin, R. Bio-Optical Characteristics of the Northern Gulf of California during June 2008. Int. J. Oceanogr. 2014, 2014, 384618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercado-Santana, J.A.; Santamaría-del-Ángel, E.; González-Silvera, A.; Sánchez-Velasco, L.; Gracia-Escobar, M.F.; Millán-Núñez, R.; Torres-Navarrete, C. Productivity in the Gulf of California Large Marine Ecosystem. Environ. Dev. 2017, 22, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Maldonado, J.A.; Santamaría-del-Ángel, E.; Sebastiá-Frasquet, M.T. Reflectances of SPOT Multispectral Images Associated with the Turbidity of the Upper Gulf of California. Rev. De Teledetección 2017, 50, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betancur-Turizo, S.P.; González-Silvera, A.G.; Santamaría-Del-Ángel, E.; Millán-Núñez, R.; Millán-Núñez, E.; García-Nava, H.; Godínez, V.M.; Sánchez-Velasco, L. Variability in the Light Absorption Coefficient by Phytoplankton, Non-Algal Particles and Colored Dissolved Organic Matter in the Northern Gulf of California. Open J. Mar. Sci. 2018, 8, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betancur-Turizo, S.P.; González-Silvera, A.; Santamaría-del-Ángel, E.; Tan, J.; Frouin, R. Evaluation of Semi-Analytical Algorithms to Retrieve Particulate and Dissolved Absorption Coefficients in Gulf of California Optically Complex Waters. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregg, W.W.; Casey, N.W. Global and Regional Evaluation of the SeaWiFS Chlorophyll Data Set. Remote Sens. Environ. 2004, 93, 463–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djavidnia, S.; Mélin, F.; Hoepffner, N. Analysis of Multi-Sensor Global and Regional Ocean Colour Products. MERSEA-IP Mar. Environ. Secur. Eur. Area-Integr. Proj. Rep. Deliv. D 2006, 2, 228. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar-Maldonado, J.A.; Santamaría-del-Ángel, E.; Sebastiá-Frasquet, M.T. Applying SPOT Images to Study the Colorado River Effects on the Upper Gulf of California. Proceedings 2017, 2, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SIMAR. Available online: https://simar.conabio.gob.mx/explorer/ (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Aguilar-Maldonado, J.A.; Santamaría-del-Ángel, E.; González-Silvera, A.; Cervantes-Rosas, O.D.; Sebastiá-Frasquet, M.-T. Mapping Satellite Inherent Optical Properties Index in Coastal Waters of the Yucatán Peninsula (Mexico). Sustainability 2018, 10, 1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Maldonado, J.A.; Santamaría-del-Ángel, E.; González-Silvera, A.; Cervantes-Rosas, O.D.; López, L.M.; Gutiérrez-Magness, A.; Cerdeira-Estrada, S.; Sebastiá-Frasquet, M.-T. Identification of Phytoplankton Blooms under the Index of Inherent Optical Properties (IOP Index) in Optically Complex Waters. Water 2018, 10, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaría-del-Ángel, E.; Cañon-Páez, M.L.; Sebastiá-Frasquet, M.T.; González-Silvera, A.; Gutierrez, A.L.; Aguilar-Maldonado, J.A.; López-Calderón, J.; Camacho-Ibar, V.; Franco-Herrera, A.; Castillo-Ramírez, A. Interannual Climate Variability in the West Antarctic Peninsula under Austral Summer Conditions. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirabal, U.; Linacre, L.; Durazo, R.; Santamaría-del-Ángel, E.; Pallàs-Sanz, E.; Lara-Lara, J.R. Regionalization of Oceanic Waters Based on Satellite Bio-Optical Properties in the Central and Southern Gulf of Mexico. RSASE 2025, 39, 101695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda-Alvarez, C.; González-Silvera, A.; Santamaría-del-Angel, E.; López-Calderón, J.; Godínez, V.M.; Sánchez-Velasco, L.; Hernández-Walls, R. Phytoplankton Pigments and Community Structure in the Northeastern Tropical Pacific Using HPLC-CHEMTAX Analysis. J. Oceanogr. 2020, 76, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larios-Muñiz, M.; González-Silvera, A.; Castro, R.; Santamaría-del-Ángel, E.; Collins, C.A.; López-Calderón, J. Variability of Hydrographic Factors, Biomass and Structure of the Phytoplankton Community at the Entrance to the Gulf of California (Spring 2013). Cont. Shelf Res. 2022, 235, 104665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautenberger, R.; Fernández, P.A.; Strittmatter, M.; Heesch, S.; Cornwall, C.E.; Hurd, C.L.; Roleda, M.Y. Saturating Light and Not Increased Carbon Dioxide under Ocean Acidification Drives Photosynthesis and Growth in Ulva Rigida (Chlorophyta). Ecol. Evol. 2015, 5, 874–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Cooley, R.I.; Gerrodette, T.; Fiedler, P.C.; Chivers, S.J.; Danil, K.; Ballance, L.T. Temporal Variation in Pelagic Food Chain Length in Response to Environmental Change. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1701140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; He, R.; Lee, Z. Effects of Ocean Optical Properties and Solar Attenuation on the Northwestern Atlantic Ocean Heat Content and Hurricane Intensity. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, e2021GL094171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Wang, M. Ocean Responses to Hurricane Ian from Daily Gap-Free Satellite Observations. Remote Sens. Lett. 2023, 14, 877–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, P.I. The Role of Satellite Observations in Understanding the Impact of El Niño on the Carbon Cycle: Current Capabilities and Future Opportunities. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2018, 373, 20170407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jauregui, Y.R.; Chen, S.S. MJO-Induced Warm Pool Eastward Extension Prior to the Onset of El Niño: Observations from 1998 to 2019. J. Clim. 2024, 37, 855–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Zhan, W.; Zhang, Y.; He, Q.; Bo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhan, H. Spatial Heterogeneity and Seasonality of Phytoplankton Responses to Marine Heatwaves in the Northeast Pacific. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 20, 014042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-H.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Wan, L.; Yuan, Y.; Yan, Y.; Hannah, C.; Chai, F. Arctic Warming as a Potential Trigger for the Warm Blob in the Northeast Pacific. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2025, 8, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Platform | Sensor | Revision Used |

|---|---|---|

| OrbView-2 | Sea-viewing Wide Field-of-view (SeaWiFS) | SeaWiFS_R2022.0 |

| TERRA | Moderate-Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) | MODIST_R2022.0 |

| ENVISAT | Medium Resolution Imaging Spectrometer (MERIS) | MERIS_R2022.0 |

| AQUA | Moderate-Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) | MODISA_R2022.0 |

| Soumi-NPP | Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) | VIIRS-SNPP_R2022.0 |

| Sentinel-3A | Ocean and Land Colour Instrument (OLCI) | OLCIA-WRR ver. 003 |

| NOAA-20 | Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) | VIIRS-JPSS1_R2022.0 |

| Sentinel-3B | Ocean and Land Colour Instrument (OLCI) | OLCIB-WRR_ver. 003 |

| NOAA-21 | Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) | VIIRS-JPSS2_R2022.0 |

| Reference | Model |

|---|---|

| Slope-Weighting Model derived from a first-degree, first-order polynomial (SWM) (Kratzer et al. [37]; Tang et al. [38]). | where |

| Morel et al. [14] | If If |

| Pierson et al. [15] | |

| Pierson et al. [15] | |

| Wang et al. [16] | |

| Saulquin et al. [18] | If If |

| Type of Model | IV | RMSD | BIAS | MAPE | MPI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear | 0.0435 | 0.0030 | 23.3178 | 0.3333 | |

| Power | 0.0428 | 0.0041 | 21.5977 | 0.4444 | |

| NESA | 0.0453 | 0.0033 | 22.7503 | 0.2222 | |

| Linear | 0.0403 | 0.0015 | 23.0121 | 0.3333 | |

| Power | 0.0397 | 0.0022 | 21.8091 | 0.4444 | |

| NESA | 0.0437 | 0.0027 | 21.0465 | 0.2222 |

| Equation | n | IV | α = 5% df = n−p | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (11) | 3733 | 72.2 | 0.0380 | 58.45 | 0.740 | 98.39 | 1.96 | 9681.32 | 2.99 | |

| (12) | 3729 | 72.1 | 0.0334 | 48.93 | 0.961 | 98.21 | 1.96 | 9645.68 | 2.99 | |

| (13) | 3717 | 74.9 | 0.0245 | 35.39 | 1.03 | 105.34 | 1.96 | 11,097.47 | 2.99 | |

| (14) | 3719 | 75.3 | 0.0273 | 40.72 | 0.970 | 106.57 | 1.96 | 11,356.68 | 2.99 | |

| Equation | n | IV | α = 5% df = n−p | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (15) | 3804 | 70.2 | 0.575 | −24.72 | 0.683 | 94.53 | 1.96 | 8936.38 | 2.99 | |

| (16) | 3799 | 70.5 | 0.737 | −12.39 | 0.732 | 95.22 | 1.96 | 9066.07 | 2.99 | |

| (17) | 3797 | 72.0 | 0.807 | −8.73 | 0.791 | 98.68 | 1.96 | 9738.64 | 2.99 | |

| (18) | 3797 | 71.9 | 0.761 | −11.07 | 0.775 | 98.44 | 1.96 | 9691.13 | 2.99 | |

| Equation | n | IV | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (19) | 3805 | 71.2 | −0.17 | −3.56 | 2.68 | 10.27 | 4.78 | 10.13 | 3.77 | 10.98 | 0.96 | 11.10 | 1.96 | 2344.83 | 2.37 | |

| (19) | 3808 | 71.1 | 0.04 | 0.55 | 3.36 | 9.05 | 5.59 | 9.19 | 4.09 | 9.96 | 0.99 | 10.06 | 1.96 | 2337.92 | 2.37 | |

| (19) | 3792 | 72.7 | 0.72 | 5.76 | 5.92 | 10.18 | 9.30 | 9.90 | 6.54 | 10.32 | 1.58 | 10.38 | 1.96 | 2525.14 | 2.37 | |

| (19) | 3792 | 72.7 | 0.41 | 4.33 | 4.77 | 10.24 | 7.73 | 9.88 | 5.61 | 10.33 | 1.38 | 10.35 | 1.96 | 2525.77 | 2.37 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zapata-Hinestroza, J.A.; Santamaría-del-Ángel, E.; Castillo-Ramírez, A.; Cerdeira-Estrada, S.; González-Silvera, A.; Caballero-Aragón, H.; Aguilar-Maldonado, J.A.; Martell-Dubois, R.; Rosique-de-la-Cruz, L.; Sebastiá-Frasquet, M.-T.

Enhanced Calculation of

Zapata-Hinestroza JA, Santamaría-del-Ángel E, Castillo-Ramírez A, Cerdeira-Estrada S, González-Silvera A, Caballero-Aragón H, Aguilar-Maldonado JA, Martell-Dubois R, Rosique-de-la-Cruz L, Sebastiá-Frasquet M-T.

Enhanced Calculation of

Zapata-Hinestroza, Jorvin A., Eduardo Santamaría-del-Ángel, Alejandra Castillo-Ramírez, Sergio Cerdeira-Estrada, Adriana González-Silvera, Hansel Caballero-Aragón, Jesús A. Aguilar-Maldonado, Raúl Martell-Dubois, Laura Rosique-de-la-Cruz, and María-Teresa Sebastiá-Frasquet.

2025. "Enhanced Calculation of

Zapata-Hinestroza, J. A., Santamaría-del-Ángel, E., Castillo-Ramírez, A., Cerdeira-Estrada, S., González-Silvera, A., Caballero-Aragón, H., Aguilar-Maldonado, J. A., Martell-Dubois, R., Rosique-de-la-Cruz, L., & Sebastiá-Frasquet, M.-T.

(2025). Enhanced Calculation of