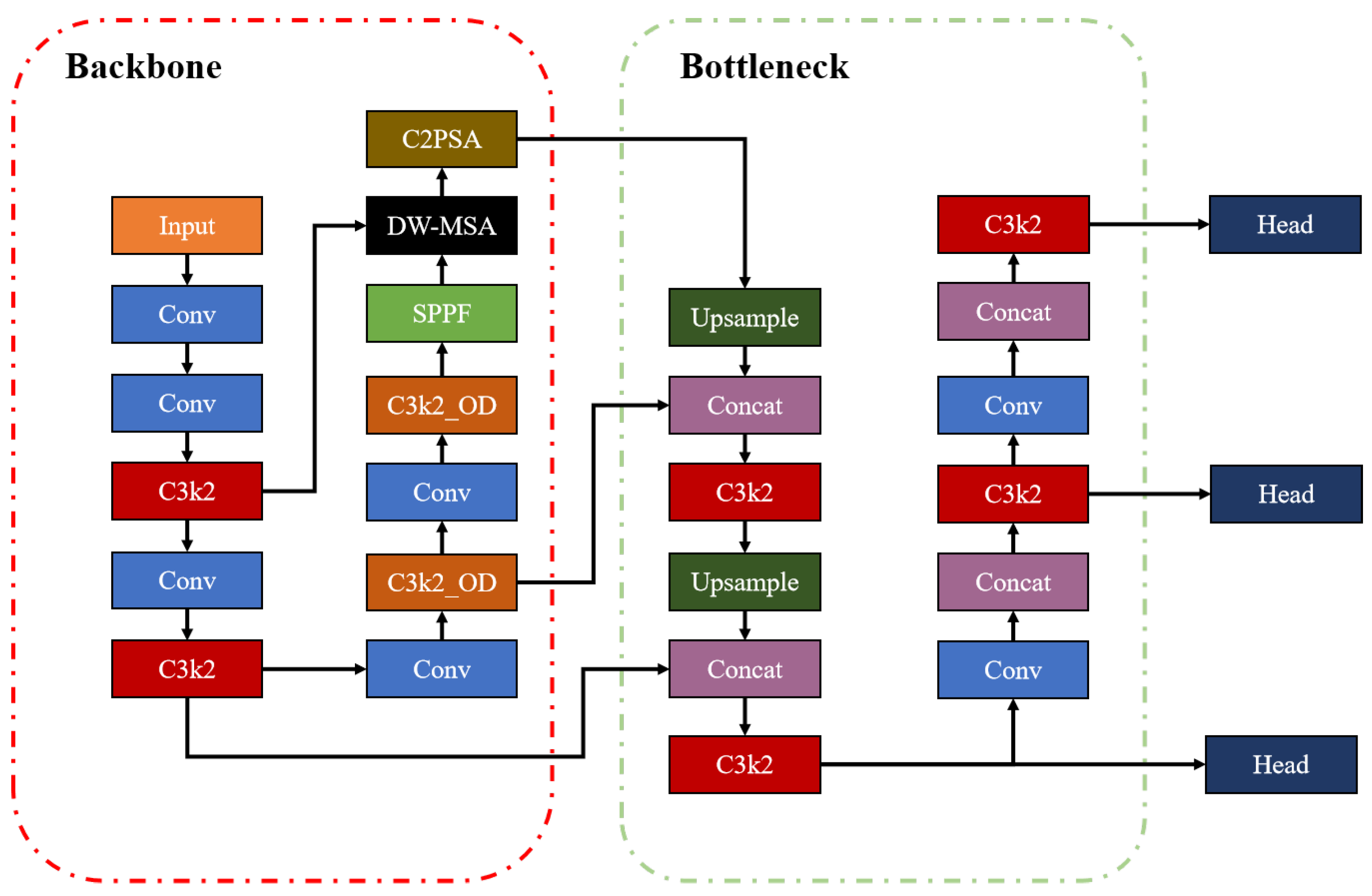

3.1. General Overview

The remote sensing aircraft detection framework proposed in this study is improved on the basis of YOLOv11 [

43]. The overall framework is shown in

Figure 1.

Firstly, the multilayer semantic fusion enhancement module utilizes the dense window self-attention mechanism to process feature maps at different scales in the FPN—by stitching shallow and deep features and applying sliding window self-attention to achieve joint modeling of local details and contextual information, which enhances the detection of small objects. Secondly, the dynamic feature response module introduces a mechanism to adaptively adjust the weights of convolution kernels to cope with scale changes, attitude perturbations, and complex textures exhibited by objects in remote sensing images, which makes the network feature representation more flexible and adaptable. Finally, the rotational geometry modeling module optimizes the RBB regression through Gaussian–Cosine distribution loss function. This achieves error smoothing from the centroid position to the rotation regression, effectively mitigates the periodic jump problem and improves the prediction accuracy.

The overall framework takes high-resolution remote sensing images as input, extracts multi-scale features and processes them sequentially through the aforementioned three modules to produce accurate rotated bounding box predictions. Unlike conventional approaches that rely solely on convolutional or attention-based architectures, the proposed method effectively addresses key challenges in the detection of remote sensing aircraft such as object overlap, loss of small objects, and unstable rotation regression, by integrating structural fusion, dynamic adaptability, and geometric optimization, which results in significant improvements in detection accuracy and robustness.

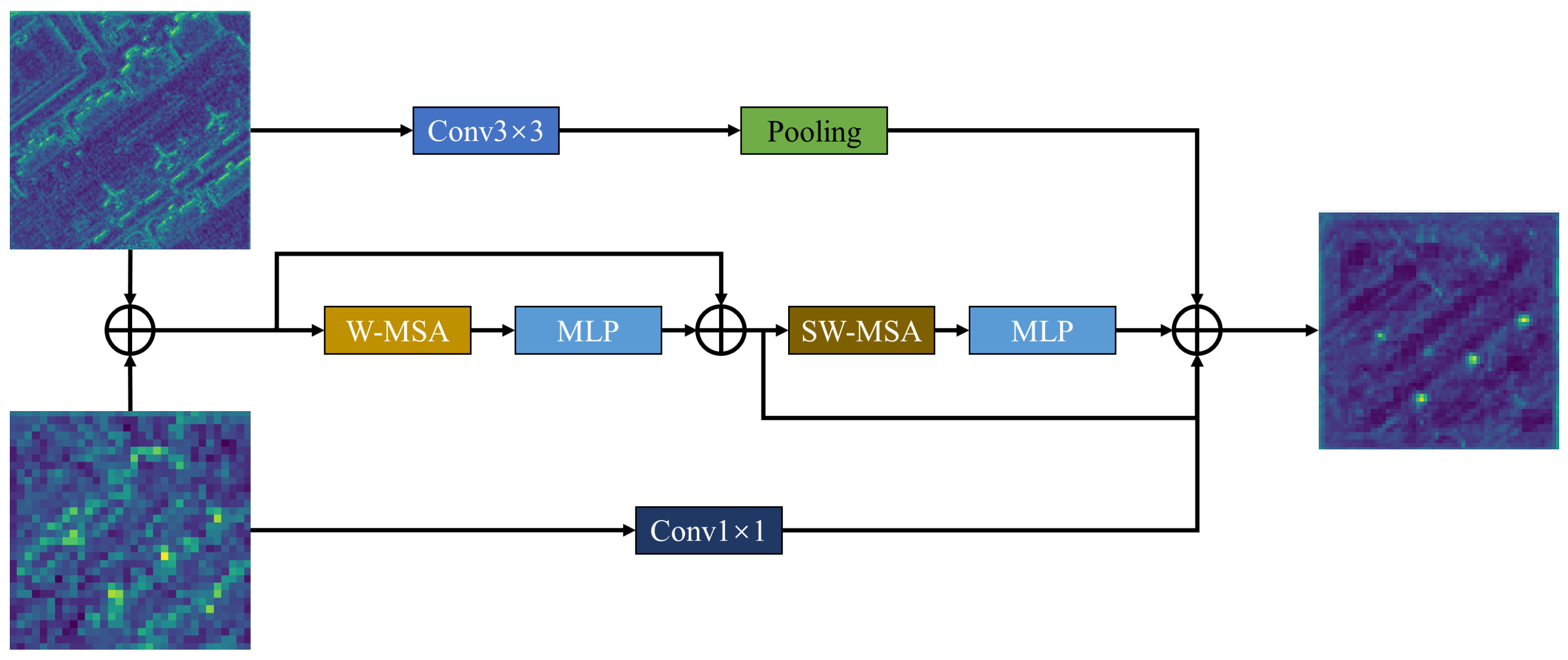

3.2. Dense Window Multi-Head Self-Attention

Objects in remote sensing imagery are often characterized by high spatial density, large-scale variation, and complex orientation changes, all of which impose stringent requirements on feature representation. To address these challenges, we design an enhanced sliding window self-attention mechanism named Dense Window Multi-head Self-Attention (DW-MSA) as shown in

Figure 2. Inspired by the Sliding Window Multi-head Self-Attention (SW-MSA) in Swin Transformer [

44], DW-MSA is redesigned to incorporate a cross-layer feature fusion strategy structurally, aiming to integrate shallow contour details, spectral textures, and deeper semantic information for robust recognition of multi-scale and diverse objects morphologically.

In the DW-MSA module, we utilize the P3 and P5 layers from the Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) as input, representing fine-grained local details and high-level semantic context, respectively. Due to differences in spatial resolution and channel dimensions, the P3 feature map is first processed by a 3 × 3 convolution to expand its receptive field and enhance texture modeling. Subsequently, it is downsampled via a stride-2 pooling operation (or an equivalent strided convolution) to match the resolution of P5. Simultaneously, a 1 × 1 convolution is applied to the P5 feature map to unify its channel dimensions. These aligned feature maps are then concatenated along the channel axis to construct a fused representation

, which takes the following form:

The final

convolution compresses the concatenated features back to the same channel dimension as the original P5.

To preserve spatial continuity and enhance inter-window communication, we adopt a sliding window partitioning strategy. The fused feature map is divided into overlapping local windows, within which multi-head self-attention is computed independently. The windows in DW-MSA use an overlap rate

to control the shared area across windows, thereby alleviating the problem of edge information fragmentation. In this paper, the overlap rate

fixed to 0.5, corresponding to a half-step sliding between adjacent windows. This design ensures a balanced overlap between local regions, allowing boundary information from neighboring windows to interact while maintaining computational efficiency. The attention calculation form within the window is modeled as follows:

where

represents the

ith sliding window operation with an overlap rate of

.

This design effectively mitigates the edge information loss typically caused by non-overlapping windows in the original Swin Transformer and promotes receptive field sharing across adjacent regions. Through this windowed attention mechanism, DW-MSA captures long-range dependencies between object regions and improves recognition robustness under background interference.

Following the attention computation, the output features are concatenated with the original aligned P3 and P5 maps along the channel dimension. A final 1 × 1 convolution is applied for feature compression and information reconstruction. The resulting DW-MSA output incorporates three complementary types of information: (1) spatial context and global dependencies modeled via attention, (2) fine edge and texture features from the shallow P3 map, and (3) high-level semantic abstraction from the P5 map. This fused representation exhibits superior discriminability and stability for detecting small objects with blurred boundaries and significant rotational variations. The final DW-MSA output represents

where the pooled

feature map and the transformed

feature map are aligned to the same spatial resolution and concatenated along the channel dimension, after which a convolution with kernel size

is applied for feature fusion. In our implementation,

is used to perform lightweight channel mixing after concatenation, while

is adopted to adjust

before alignment.

Overall, the DW-MSA module effectively overcomes the representational limitations of traditional convolutional or pure Transformer-based architectures in complex remote sensing scenes. Its modular design, enhanced expressiveness, and cross-scale perception ability improve the detection robustness of the model significantly and provide a more informative foundation for subsequent feature interaction and object regression stages.

3.3. Omni-Dimensional Dynamic Convolution

In remote sensing object detection, small objects often exhibit irregular shapes, indistinct boundaries, and low-texture features, placing elevated demands on the feature extraction capacity of detection models. To enhance recognition accuracy under such conditions, we incorporate Omni-Dimensional Dynamic Convolution [

45] (ODConv) into the YOLOv11 architecture. By integrating a multi-dimensional attention mechanism, ODConv modulates convolutional kernel weights adaptively in response to the semantic structure and spatial distribution of input features, thereby strengthening the model’s focus on salient object regions—particularly those corresponding to small objects in high-resolution remote sensing imagery.

The core mechanism of ODConv lies in its four-dimensional attention modulation, which adjusts convolution behavior across the spatial, channel, kernel, and filter dimensions. Each dimension generates an attention weight vector that calibrates the response of the convolution operation dynamically within its scope, enabling more flexible and fine-grained feature adaptation across positions, scales, and orientations.

As shown in

Figure 3, ODConv performs dynamic adjustment of the convolution operation through a sequence of four attention mechanisms, each operating along a distinct dimension:

Spatial-wise Attention: this step is a multiplication operation along the spatial dimension of the convolution kernel to adjust the weights of different spatial locations in each convolution kernel;

Channel-wise Attention: this step is a multiplication operation along the dimension of the input channels, assigning different weights to each input channel

Convolution kernel-wise Attention: this step is a multiplication operation along the convolution kernel dimension. Each convolution kernel is weighted;

Filter-wise Attention: this step is a multiplication operation along the filter dimension to adjust the convolutional weights of each output channel.

By combining these attention operations, ODConv generates dynamic convolution kernels that are conditioned on the input features, thereby enhancing the flexibility and specificity of feature extraction.

The overall computation process can be summarized as follows:

where

represents the attention weights of spatial, channel, output channel and convolution kernel dimensions, respectively,

is the convolution kernel,

x is the input feature map, and

y is the output feature map.

The above attention mechanisms work in concert to generate dynamic convolution kernels with input sensing ability, which enables the model to respond more accurately to the changing and complex aircraft in remote sensing images in the feature extraction stage. ODConv improves the sensitivity of the network to small objects and the ability of regional expression significantly while retaining the computational structure of the original convolution module.

In the SPOD-YOLO framework, ODConv is integrated into the downsampling module C3k2 in YOLOv11, replacing traditional convolutional layers. The modified version of this module is referred to as C3k2_OD. This module is responsible for low-level feature extraction and spatial resolution reduction. During training, the attention weights across spatial, channel, and kernel dimensions are learned to automatically adapt convolutional parameters to variations in the input. Additionally, both the number and behavior of convolution kernels are adjusted dynamically, thereby enhancing the adaptability of network and improving detection performance. C3k2_OD achieves this while preserving the computational efficiency of standard convolution modules, offering a practical balance between accuracy and model complexity.

3.4. Gaussian–Cosine-Based Angle-Aware Loss Function

In remote sensing imagery, particularly in typical scenarios such as airports, aircraft often exhibit strong directional consistency and dense spatial distributions. In such scenes, traditional object detection methods that employ HBB face critical limitations. Due to the intrinsic orientation of aircraft, horizontal boxes fail to tightly enclose object boundaries, resulting in significant redundant background regions. This issue becomes more pronounced in dense scenes, where multiple HBBs tend to overlap extensively, severely impacting the performance of non-maximum suppression (NMS). These overlaps often lead to increased false positives and missed detections. In contrast, RBB detection can align with the principal axis of objects, providing more compact and precise enclosures. This alignment alleviates bounding box collisions in high-density areas and enhances detection robustness under crowded conditions.

More importantly, RBBs not only improve spatial fitting but also offer richer geometric descriptions. Each rotated box output encodes the object centroid coordinates, width, height, and orientation angle , where the direction and the length of the long axis jointly define the object structural signature.

Based on these considerations, this work adopts a rotated bounding box representation within the detection framework. This design not only improves localization accuracy and object separability in dense environments, but also provides structured, orientation-aware features that facilitate robust object tracking and re-identification across sequential remote sensing frames.

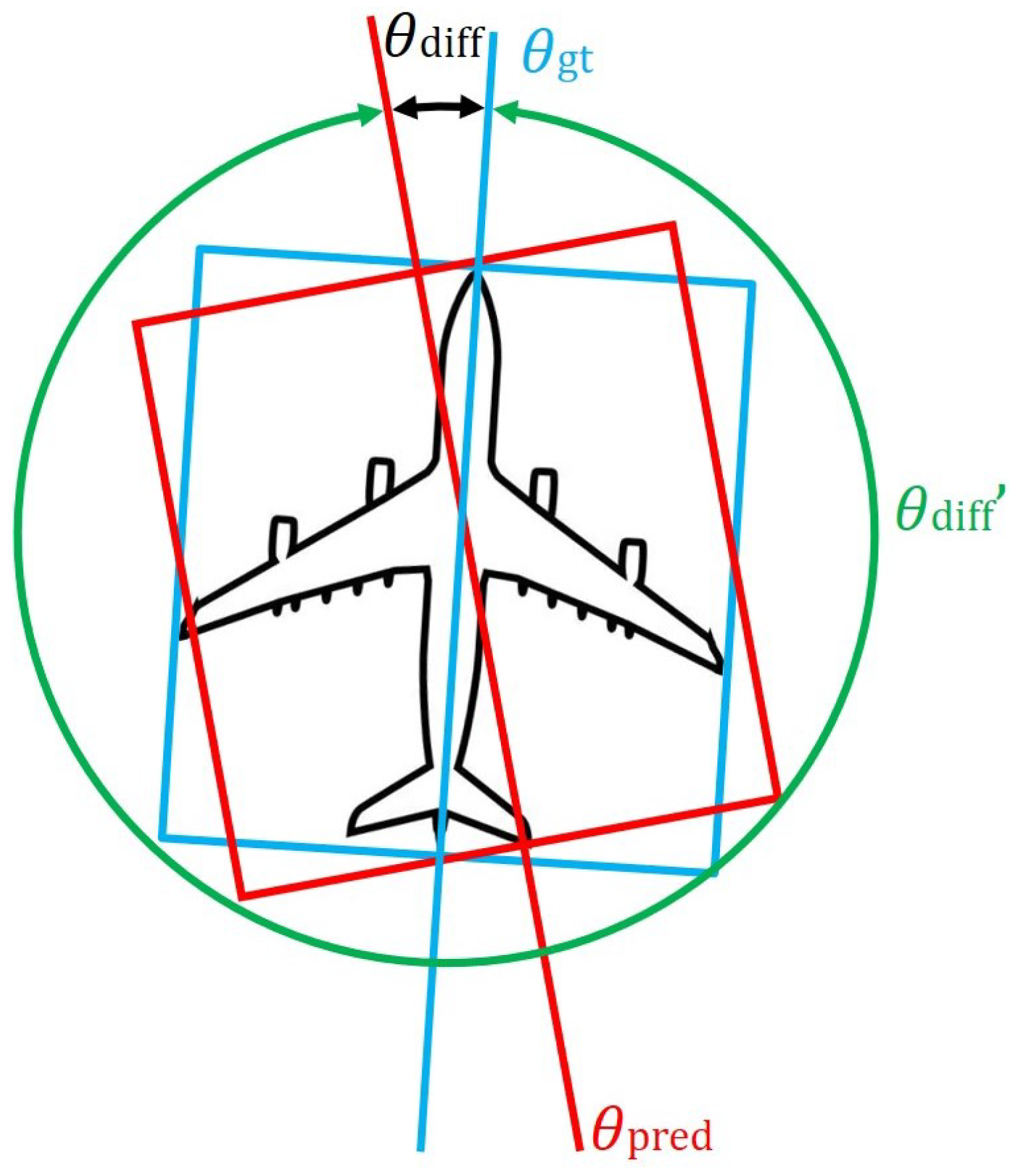

In the process of RBB object detection, in addition to the regression of position and size, it is also necessary to supervise the rotation angle of the object. The rotation regression adopted by most current RBB object detection methods is mainly based on linear loss functions (e.g., L1, Smooth L1). However, this loss function has obvious shortcomings in dealing with periodic angular variables, which may introduce serious gradient misjudgment and affect the learning of the real orientation of the object.

As shown in

Figure 4, if the true angle of the object

is 5° and the predicted value

is 355°, the two are almost equivalent geometrically, and the actual

has only 10° deviation, but the result of linear loss calculation

is 350°, which is obviously unreasonable.

To solve the above problem, this part proposes a Gaussian–Cosine-based Angle-aware Loss function, which periodically maps the angular difference by introducing the cosine function, so that the loss function can give a more reasonable gradient feedback when the angular error is small in a geometric sense.

In YOLO rotated frame object detection task, the angle of rotation is defined as

and hence the difference between the predicted angle and the true angle ranges from

to

. For this purpose, the angular difference needs to be multiplied by a factor of 2 and then fed into a trigonometric function to realize the periodic mapping. The rotated detection frame formed in the image when the difference between two angles is

is geometrically overlapping, which is the same as the correct result when the angle difference is 0. Therefore, the function value is close to 1 when the angle difference is 0 or when the value of the function is close to 1, i.e.,

x is 0 or

. Based on this, the cosine function is chosen to map the angle difference

to

x:

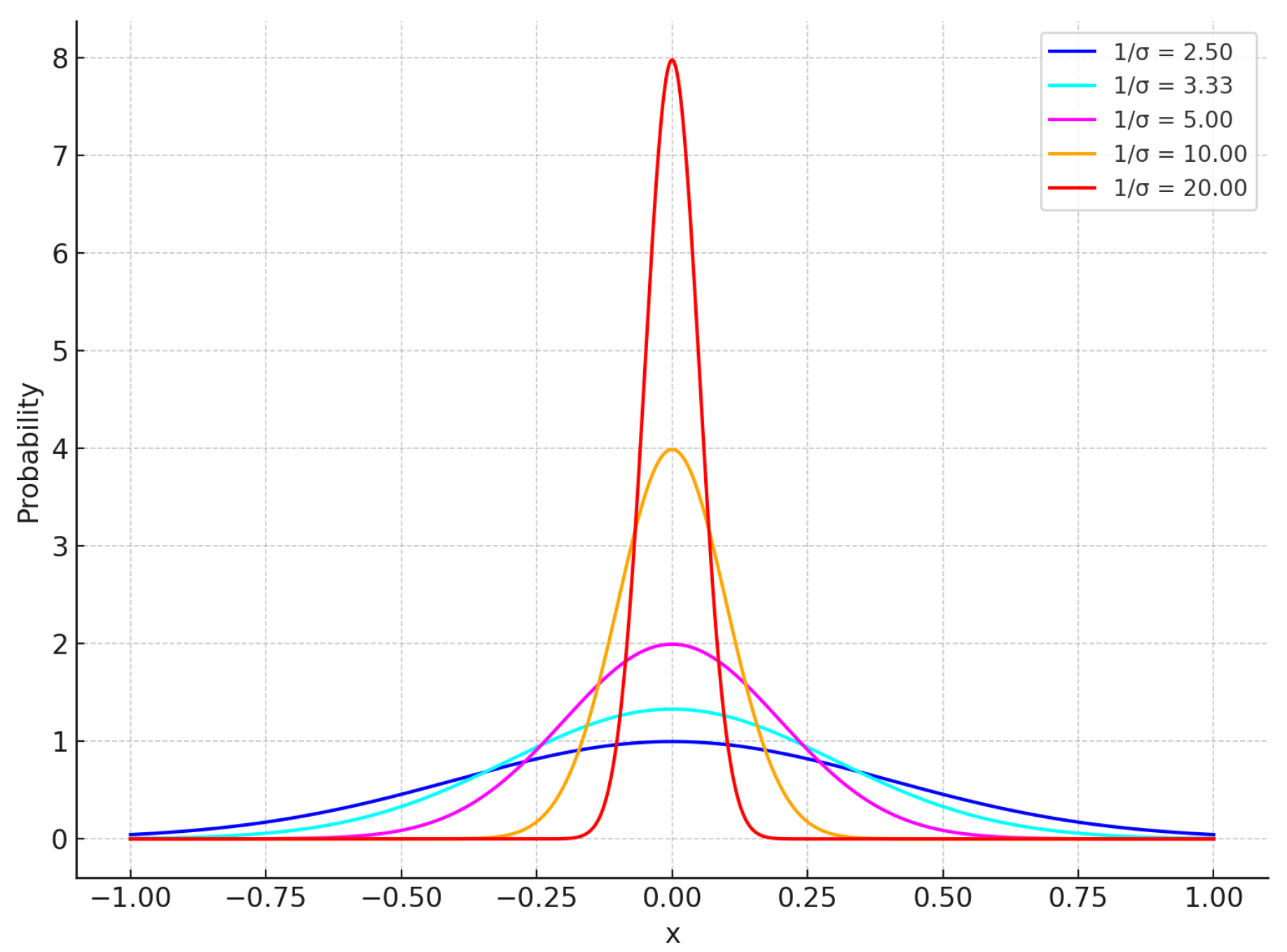

Then input the obtained x into a Gaussian distribution function to obtain the final loss function:

where

is the standard deviation of the Gaussian distribution, controlling the width of its peak and thus affecting the sensitivity of angular differences to losses. When

is large, the function is smoother and the model is less sensitive to angular errors, and conversely the function is steeper and angular deviations produce greater losses. The effect of different

in the Gaussian distribution function is illustrated in

Figure 5. Multiple sets of tuning experiments were conducted on the values of the angular loss weights to balance their effect on model training.