RSAM: Vision-Language Two-Way Guidance for Referring Remote Sensing Image Segmentation

Highlights

- A novel benchmark dataset, RISORS, containing 36,697 high-quality instruction–mask pairs, is constructed to advance referring remote sensing image segmentation (RRSIS) research.

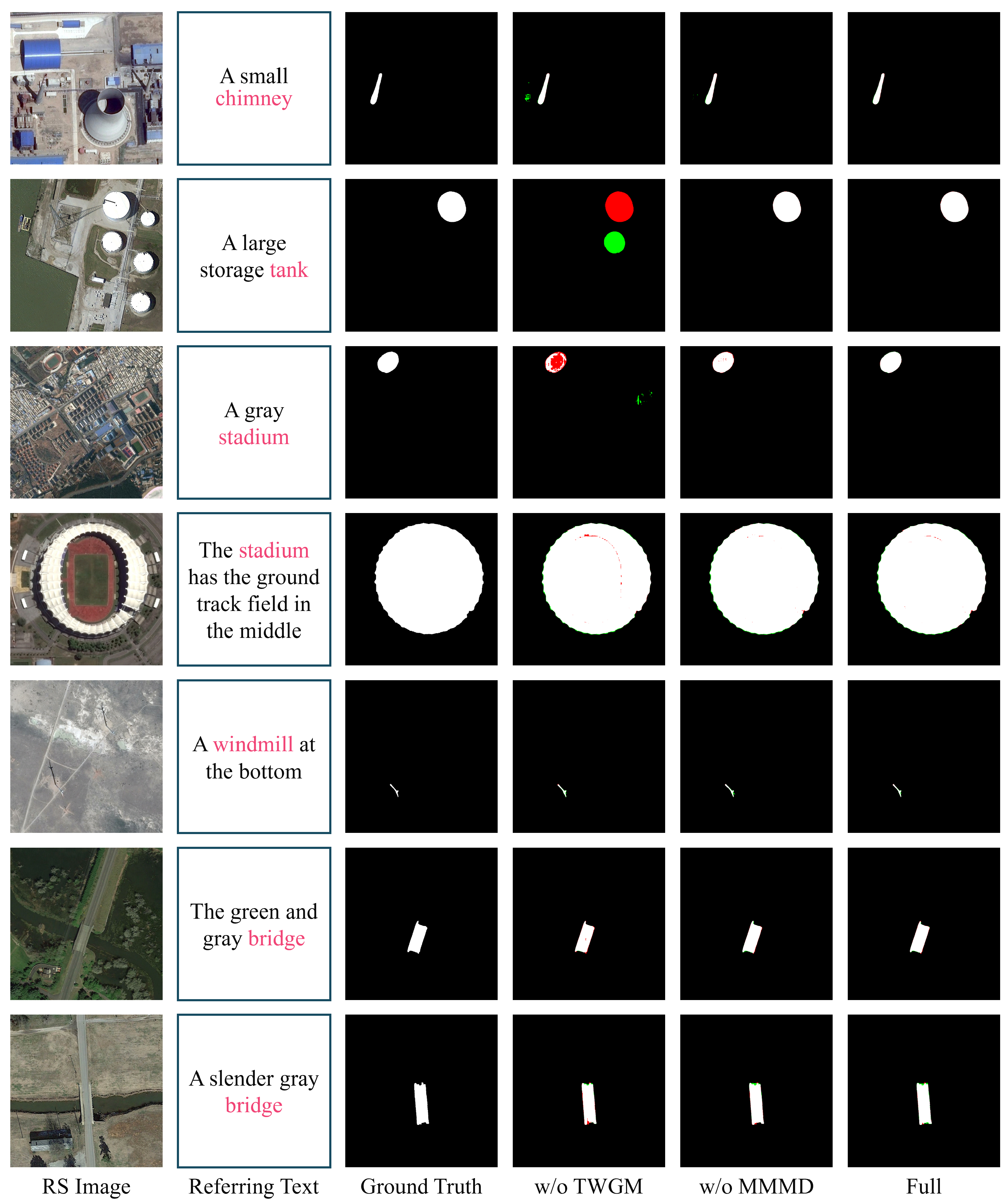

- The proposed Referring-SAM (RSAM) framework, featuring a Two-Way Guidance Module (TWGM) and a Multimodal Mask Decoder (MMMD), achieves state-of-the-art segmentation performance, especially for small and diverse targets.

- The RISORS dataset and the RSAM framework provide a foundation and a baseline for future research in integrated vision-language analysis for referring remote sensing image segmentation.

- The design of TWGM and MMMD demonstrates an effective approach for achieving robust cross-modal alignment and precise text-prompted segmentation in complex remote sensing scenarios.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We construct RISORS, a novel dataset for the RRSIS task. It provides precise pixel-level masks for each instance and contains a total of 36,697 text description–mask pairs. This dataset will be released as an open-source resource for the research community.

- We propose a Two-Way Guidance Module (TWGM). It enables synchronous updates of image and text features, allowing them to mutually guide each other. Meanwhile, it incorporates position embeddings into every attention layer, which is critical for enhancing the model’s ability to understand relationships between objects.

- We introduce RSAM, a variant of SAM 2 equipped with a Multimodal Mask Decoder, enabling linguistic interpretation and precise referring segmentation of remote sensing images. Experimental results show our method achieves state-of-the-art segmentation precision.

2. Related Work

2.1. Referring Image Segmentation on Natural Images

2.2. Referring Remote Sensing Image Segmentation

2.3. SAM with Text Prompt

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Datasets

3.1.1. Construction Procedure of RISORS

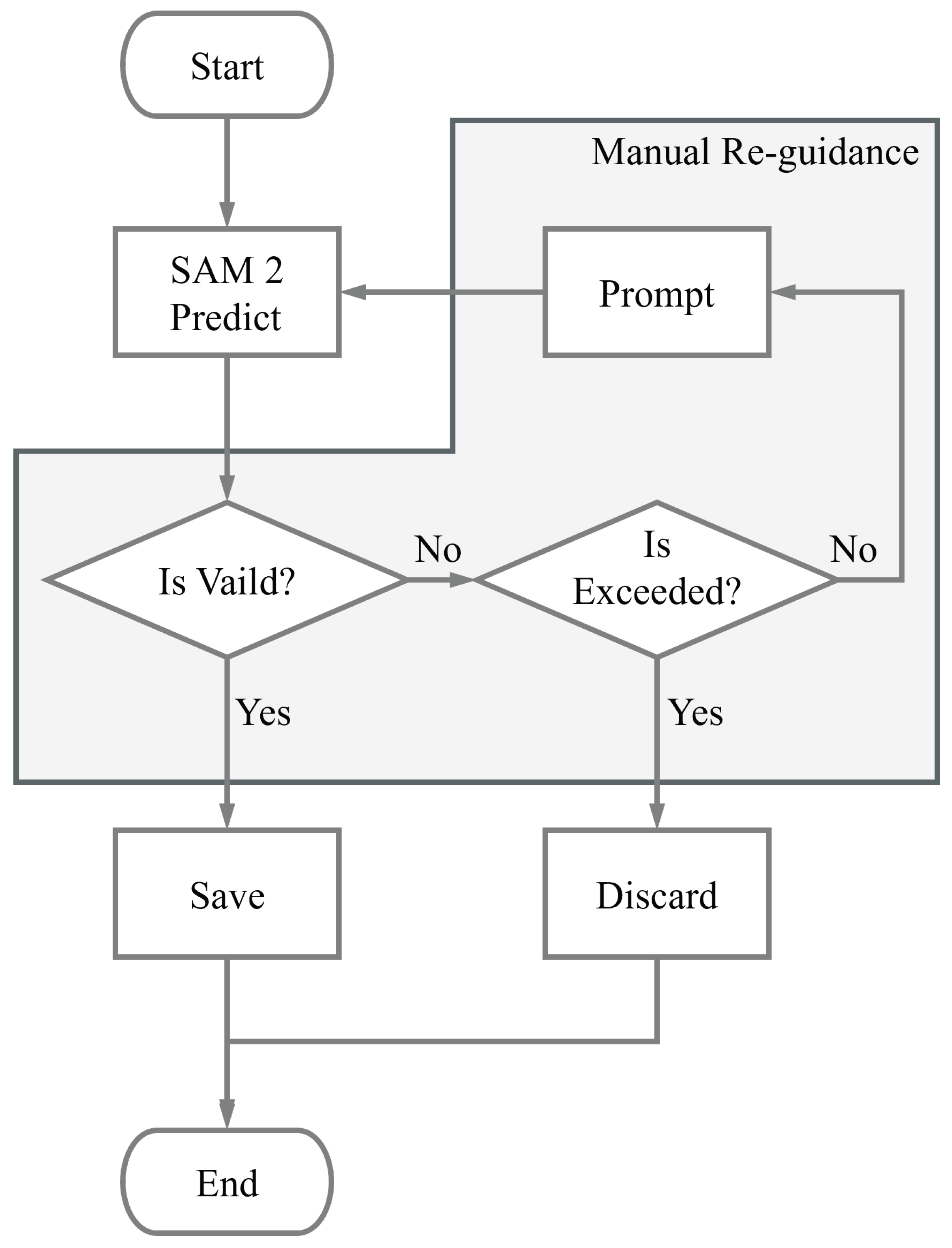

- (1)

- For each instance, using the original bounding boxes of the targets as prompts, sam2.1-hiera-large generates three different pixel-level initial masks.

- (2)

- These masks undergo manual screening to select effective ones; if all three are invalid, manual re-guidance is implemented. This re-guidance involves adding a point prompts to any of the previously generated masks, including positive points which indicating areas to retain and negative points which indicating areas to discard. Sam2.1-hiera-large takes the manually added points, original bounding box, and previously generated mask as prompts to generate new masks. This manual re-guidance process can be executed multiple times until an effective mask is obtained. If too many re-guidance attempts still fail to produce a valid mask, the instance is discarded.

- (3)

- All images and masks are uniformly resized to by cropping or padding with black borders. Annotations are stored in SA-1B format [21]. The annotations preserve the original text instructions and bounding boxes, masks, and all manually added prompt points. Additional instance information is also maintained, as detailed in Table 1. The masks are stored using Run-Length Encoding (RLE) for efficient representation.

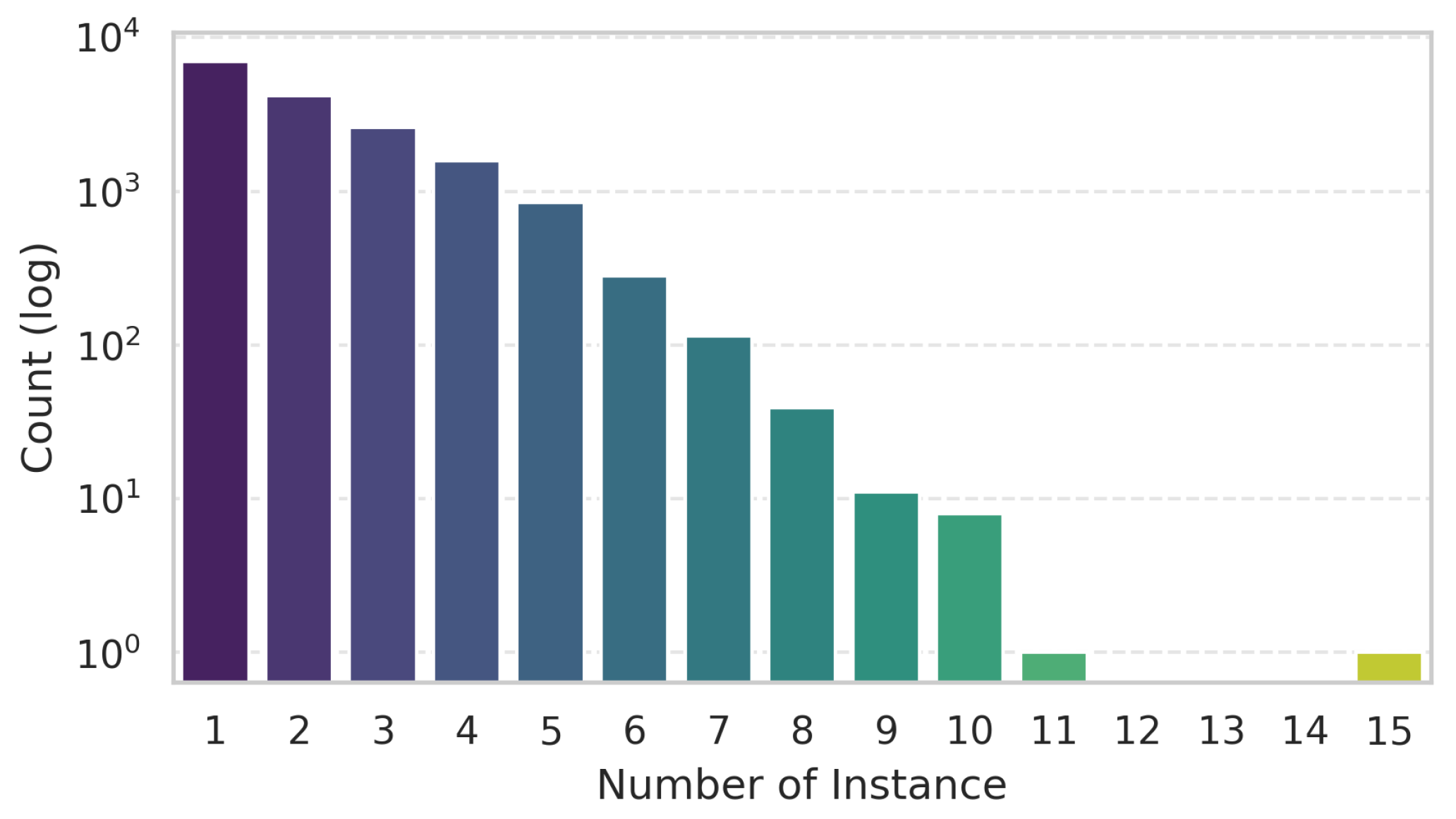

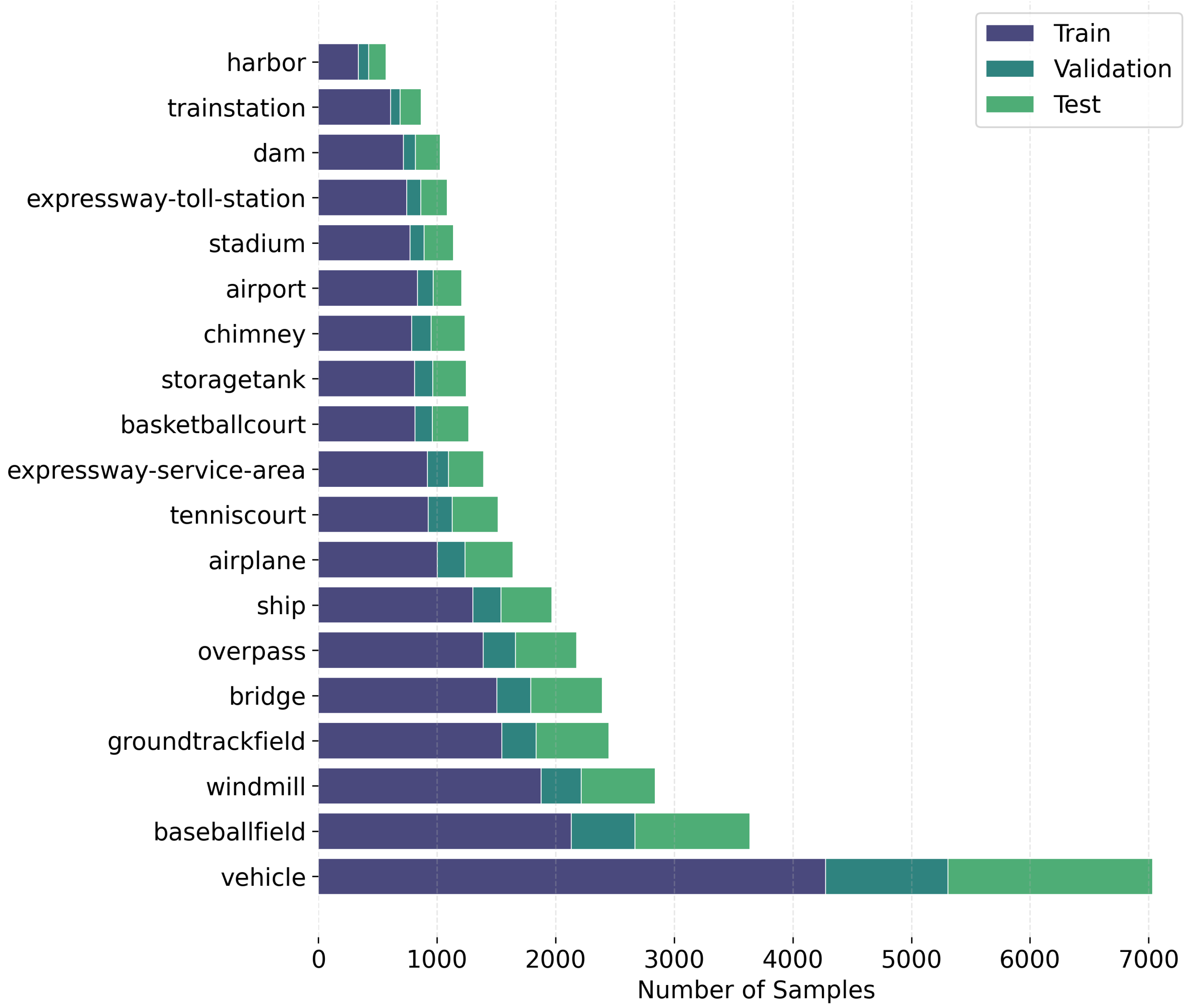

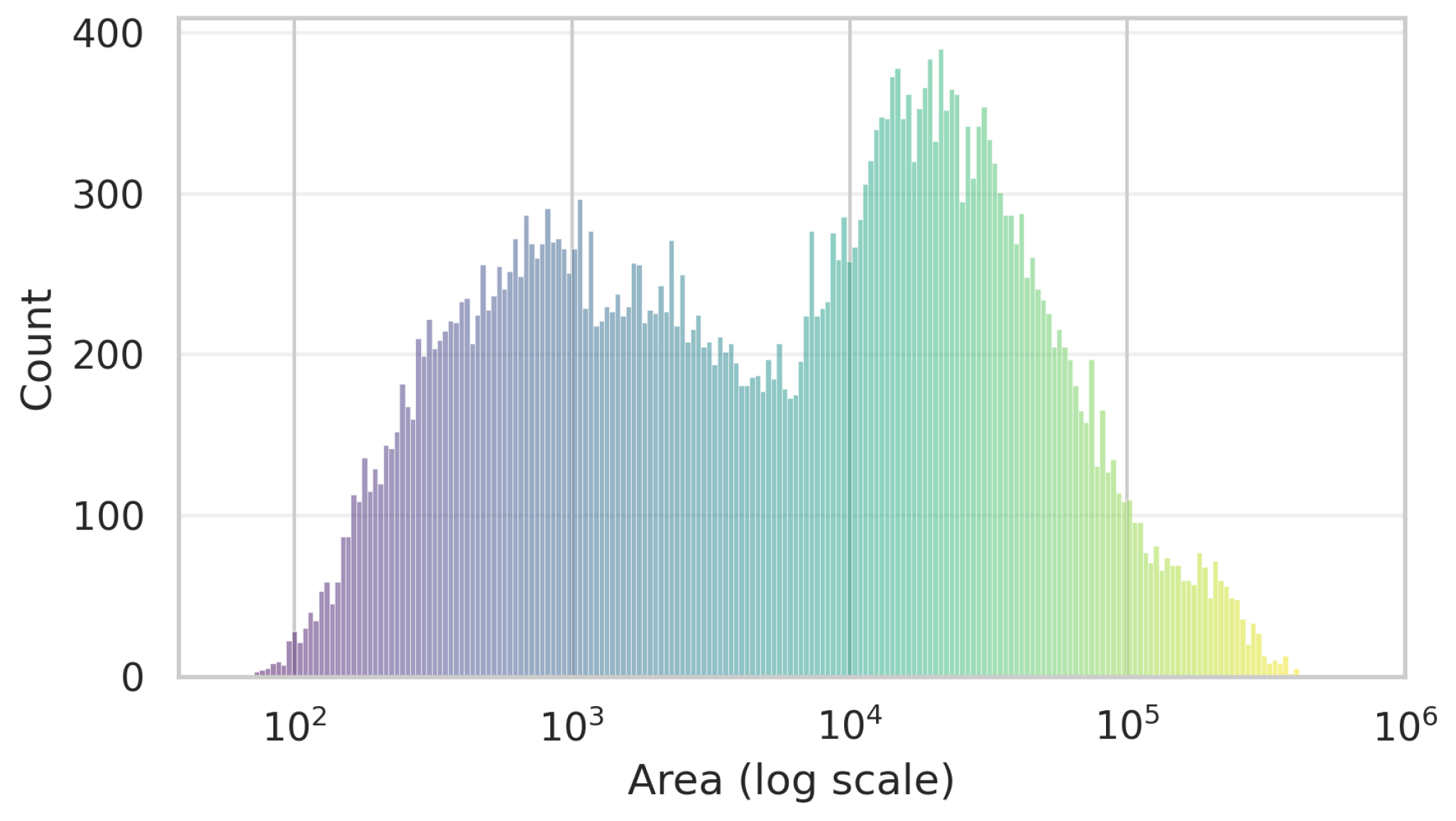

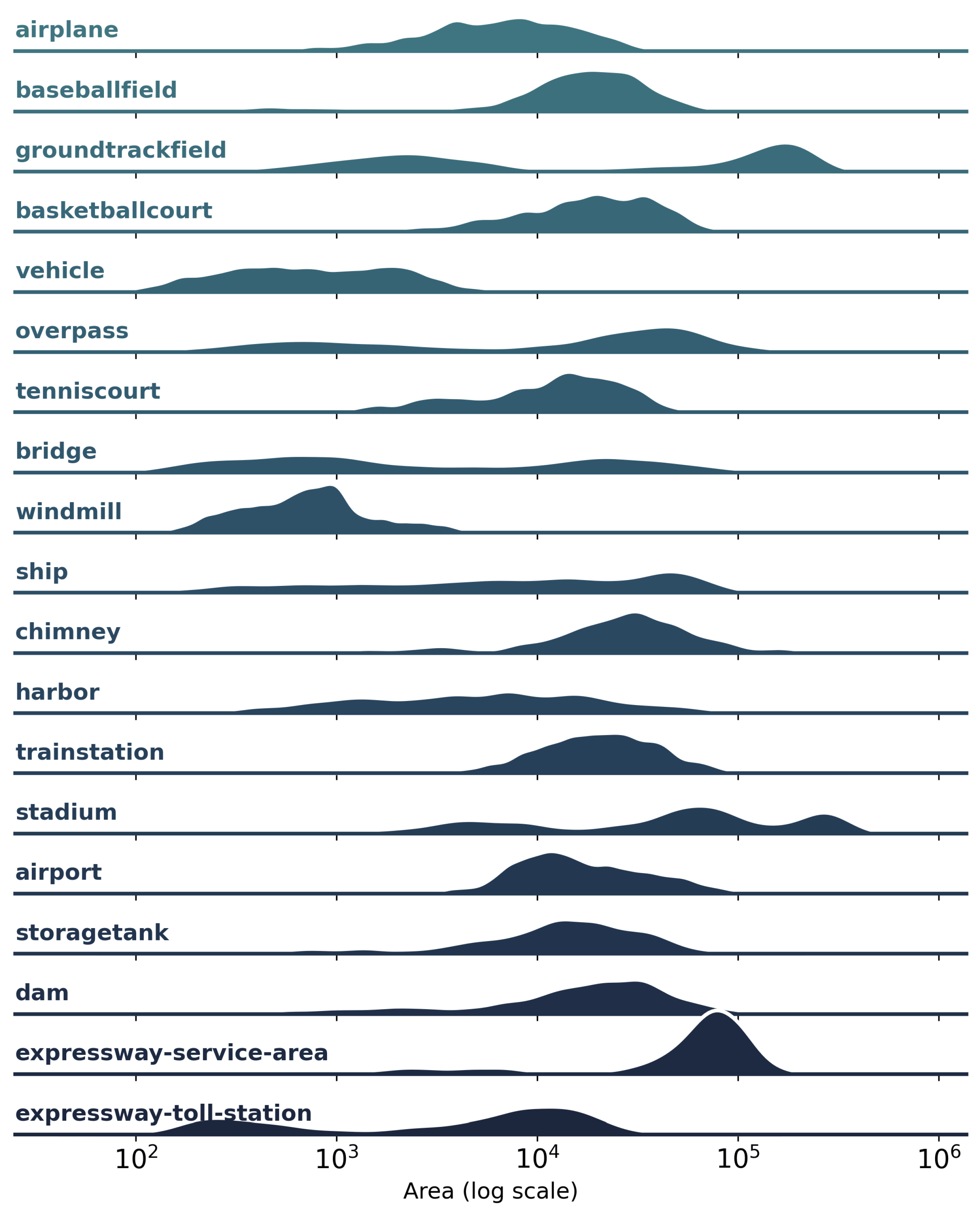

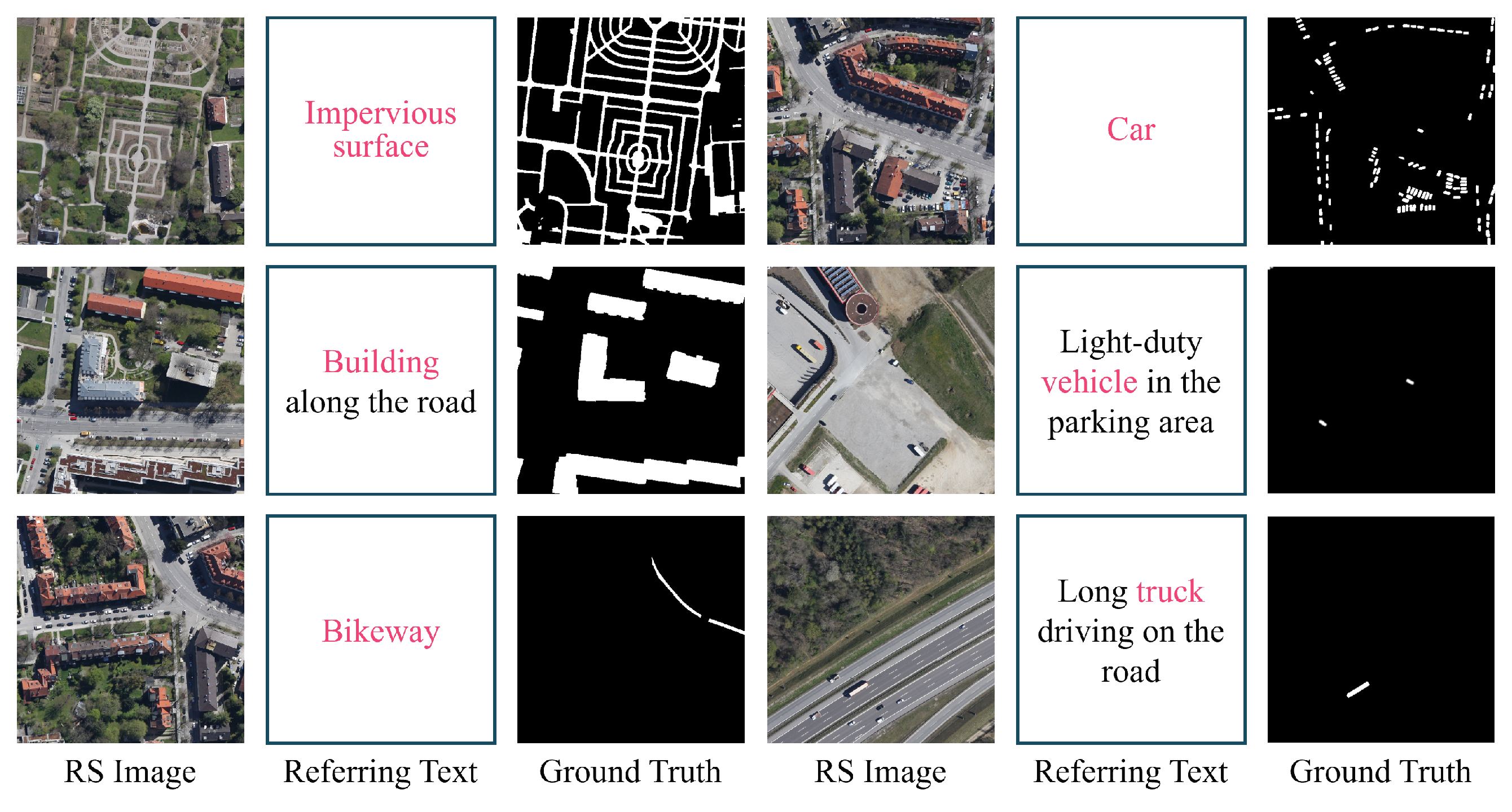

3.1.2. Data Characteristics and Analysis of RISORS

3.1.3. Comparison of Datasets

3.2. Proposed Method

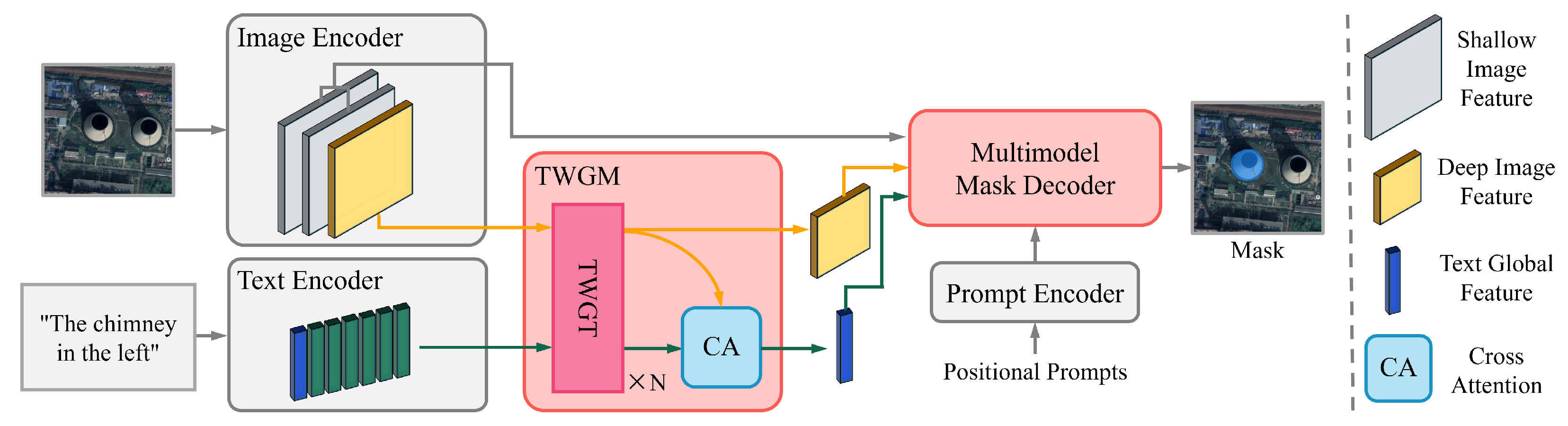

3.2.1. Overall Architecture and Formulation

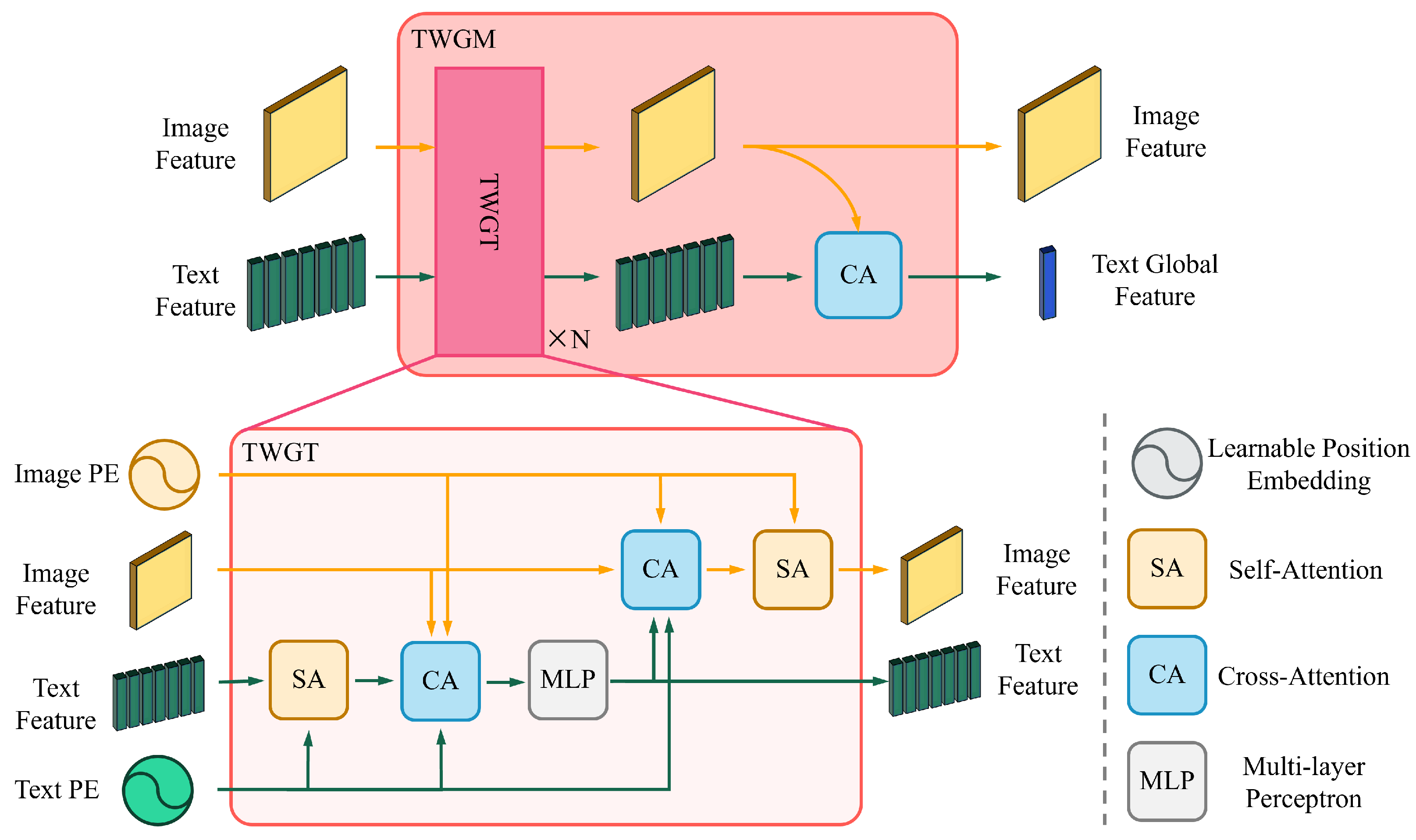

3.2.2. Two-Way Guidance Transformer Module

3.2.3. Multi-Model Mask Decoder

3.2.4. Objective Function

3.3. Experimental Setup

3.3.1. Evaluation Metrics

3.3.2. Comparative Experiment

3.3.3. Ablation Studies

3.3.4. Comparison of Different Model Setting

3.3.5. Multimodal Prompt Capability

4. Results

4.1. Comparisons with Other Methods

4.2. Ablation Studies

4.3. Comparison of Different Model Setting

4.4. Multimodal Prompt Capability

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yuan, Z.; Mou, L.; Hua, Y.; Zhu, X.X. Rrsis: Referring Remote Sensing Image Segmentation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2306.08625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikeš, S.; Haindl, M.; Scarpa, G.; Gaetano, R. Benchmarking of Remote Sensing Segmentation Methods. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2015, 8, 2240–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, L.T.; Sappa, A.D. Multispectral semantic segmentation for land cover classification: An overview. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 14295–14336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Song, F.; Jeon, G.; Sun, R. Scene changes understanding framework based on graph convolutional networks and Swin transformer blocks for monitoring LCLU using high-resolution remote sensing images. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Hong, D.; Gao, L.; Yao, J.; Zheng, K.; Zhang, B.; Chanussot, J. Deep learning in multimodal remote sensing data fusion: A comprehensive review. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 112, 102926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Nepal, M.; Nguyen, K.; Dur, F. Machine learning and remote sensing integration for leveraging urban sustainability: A review and framework. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 96, 104653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagliardi, V.; Tosti, F.; Bianchini Ciampoli, L.; Battagliere, M.L.; D’Amato, L.; Alani, A.M.; Benedetto, A. Satellite remote sensing and non-destructive testing methods for transport infrastructure monitoring: Advances, challenges and perspectives. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Fu, X.; Qin, R.; Wang, X.; Ma, Z. High-speed lightweight ship detection algorithm based on YOLO-v4 for three-channels RGB SAR image. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlik, I.; Miller, T.; Kostecka, E.; Tuński, T. Artificial Intelligence in Maritime Transportation: A Comprehensive Review of Safety and Risk Management Applications. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proc. IEEE 1998, 86, 2278–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, S.; Lin, H.; Ren, H.; Hu, Z.; Weng, L.; Xia, M. Mdanet: A high-resolution city change detection network based on difference and attention mechanisms under multi-scale feature fusion. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Li, X.; Du, Z.; Shen, H. Spatiotemporal enhancement and interlevel fusion network for remote sensing images change detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5609414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C.; Zhang, X.; Tong, X.; Guan, N.; Yi, X.; Yang, K.; Zhu, J.; Yu, A. Few-shot remote sensing image scene classification: Recent advances, new baselines, and future trends. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2024, 209, 368–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Y.; Gang, S.; Guan, C. FCIHMRT: Feature cross-layer interaction hybrid method based on Res2Net and transformer for remote sensing scene classification. Electronics 2023, 12, 4362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Xu, X.; Chen, H.; Li, J.; Pu, F. Visual Global-Salient Guided Network for Remote Sensing Image-Text Retrieval. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5641814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Xu, Y.; Yuan, C.; Liu, W.; Li, B.; Hu, W. Improving visual grounding with visual-linguistic verification and iterative reasoning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 9499–9508. [Google Scholar]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2015: 18th International Conference, Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.C.; Zhu, Y.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Encoder-decoder with atrous separable convolution for semantic image segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 801–818. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, E.; Wang, W.; Yu, Z.; Anandkumar, A.; Alvarez, J.M.; Luo, P. SegFormer: Simple and efficient design for semantic segmentation with transformers. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 12077–12090. [Google Scholar]

- Kirillov, A.; Mintun, E.; Ravi, N.; Mao, H.; Rolland, C.; Gustafson, L.; Xiao, T.; Whitehead, S.; Berg, A.C.; Lo, W.Y.; et al. Segment anything. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 2–6 October 2023; pp. 4015–4026. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Ji, J.; Sun, X.; Ji, R. Rotated multi-scale interaction network for referring remote sensing image segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–21 June 2024; pp. 26658–26668. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, S.; Xiao, X.; Zhang, T.; Li, H.C.; Shi, Z.; Zhu, Q. Exploring fine-grained image-text alignment for referring remote sensing image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 63, 5604611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryali, C.; Hu, Y.T.; Bolya, D.; Wei, C.; Fan, H.; Huang, P.Y.; Aggarwal, V.; Chowdhury, A.; Poursaeed, O.; Hoffman, J.; et al. Hiera: A hierarchical vision transformer without the bells-and-whistles. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–29 July 2023; pp. 29441–29454. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; Volume 1, pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, R.; Rohrbach, M.; Darrell, T. Segmentation from natural language expressions. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; pp. 108–124. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Lin, Z.; Shen, X.; Yang, J.; Lu, X.; Yuille, A. Recurrent multimodal interaction for referring image segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 1271–1280. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.; Li, K.; Kuo, Y.C.; Shu, M.; Qi, X.; Shen, X.; Jia, J. Referring image segmentation via recurrent refinement networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 5745–5753. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, L.; Rochan, M.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y. Cross-modal self-attention network for referring image segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 16–20 June 2019; pp. 10502–10511. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, G.; Zhou, Y.; Ji, R.; Sun, X.; Su, J.; Lin, C.W.; Tian, Q. Cascade grouped attention network for referring expression segmentation. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Virtual, 12–16 October 2020; pp. 1274–1282. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z.; Feng, G.; Sun, J.; Zhang, L.; Lu, H. Bi-directional relationship inferring network for referring image segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 4424–4433. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Xia, M.; Li, G.; Zhou, H.Y.; Yu, Y. Bottom-up shift and reasoning for referring image segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Virtual, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 11266–11275. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Virtual, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 10012–10022. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, J.; Tang, Y.; Chen, K.; Zhao, H.; Torr, P.H. Lavt: Language-aware vision transformer for referring image segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 18155–18165. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Ding, H.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, X. Multi-Modal Mutual Attention and Iterative Interaction for Referring Image Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2023, 32, 3054–3065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Sun, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, Y. Rethinking the Implicit Optimization Paradigm with Dual Alignments for Referring Remote Sensing Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Melbourne, Australia, 28 October–1 November 2024; pp. 2031–2040. [Google Scholar]

- Ravi, N.; Gabeur, V.; Hu, Y.T.; Hu, R.; Ryali, C.; Ma, T.; Khedr, H.; Rädle, R.; Rolland, C.; Gustafson, L.; et al. Sam 2: Segment anything in images and videos. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.00714. [Google Scholar]

- Diab, M.; Kolokoussis, P.; Brovelli, M.A. Optimizing zero-shot text-based segmentation of remote sensing imagery using SAM and Grounding DINO. Artif. Intell. Geosci. 2025, 6, 100105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zeng, Z.; Ren, T.; Li, F.; Zhang, H.; Yang, J.; Jiang, Q.; Li, C.; Yang, J.; Su, H.; et al. Grounding dino: Marrying dino with grounded pre-training for open-set object detection. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; pp. 38–55. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, H.; Li, X.; Zhang, T.; Huang, Z.; Xu, S.; Ji, S.; Tong, Y.; Qi, L.; Feng, J.; Yang, M.H. Sa2VA: Marrying SAM2 with LLaVA for Dense Grounded Understanding of Images and Videos. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.04001. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, X.; Tian, Z.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, S.; Jia, J. Lisa: Reasoning segmentation via large language model. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–21 June 2024; pp. 9579–9589. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Li, C.; Wu, Q.; Lee, Y.J. Visual instruction tuning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 34892–34916. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, Y.; Xiong, Z.; Yuan, Y. Rsvg: Exploring data and models for visual grounding on remote sensing data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5604513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.Y.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Hariharan, B.; Belongie, S. Feature pyramid networks for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 2117–2125. [Google Scholar]

- Karpathy, A.; Fei-Fei, L. Deep visual-semantic alignments for generating image descriptions. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 3128–3137. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Q.; Bai, C.; Kpalma, K. Intra-modal constraint loss for image-text retrieval. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Bordeaux, France, 16–19 October 2022; pp. 4023–4027. [Google Scholar]

- Chng, Y.X.; Zheng, H.; Han, Y.; Qiu, X.; Huang, G. Mask grounding for referring image segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–21 June 2024; pp. 26573–26583. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Carion, N.; Massa, F.; Synnaeve, G.; Usunier, N.; Kirillov, A.; Zagoruyko, S. End-to-end object detection with transformers. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; pp. 213–229. [Google Scholar]

- Long, J.; Shelhamer, E.; Darrell, T. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 3431–3440. [Google Scholar]

- Ba, J.L.; Kiros, J.R.; Hinton, G.E. Layer normalization. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1607.06450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, D.; Dai, A.; Le, Q.V. Hypernetworks. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1609.09106. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal loss for dense object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2980–2988. [Google Scholar]

- Milletari, F.; Navab, N.; Ahmadi, S.A. V-net: Fully convolutional neural networks for volumetric medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2016 Fourth International Conference on 3D Vision (3DV), Stanford, CA, USA, 25–28 October 2016; pp. 565–571. [Google Scholar]

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L.; et al. PyTorch: An Imperative Style, High-Performance Deep Learning Library. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Wallach, H., Larochelle, H., Beygelzimer, A., d’Alché-Buc, F., Fox, E., Garnett, R., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2019; Volume 32. [Google Scholar]

- Loshchilov, I.; Hutter, F. Decoupled weight decay regularization. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1711.05101. [Google Scholar]

- Hui, T.; Liu, S.; Huang, S.; Li, G.; Yu, S.; Zhang, F.; Han, J. Linguistic structure guided context modeling for referring image segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Virtual, 23–28 August 2020; pp. 59–75. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.; Hui, T.; Liu, S.; Li, G.; Wei, Y.; Han, J.; Liu, L.; Li, B. Referring image segmentation via cross-modal progressive comprehension. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 10488–10497. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Hui, T.; Huang, S.; Wei, Y.; Li, B.; Li, G. Cross-modal progressive comprehension for referring segmentation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 44, 4761–4775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Field Name | Description |

|---|---|

| id | The id of instance |

| name | The category to which the instance belongs |

| description | A text instruction of the instance |

| area | The number of pixels occupied by the mask |

| bbox | The bounding box of the instance |

| point_coords | Coordinates of points added during manual re-guidance |

| point_labels | Mark whether the point is positive or negative |

| segmentation | The mask in RLE format |

| predicted_iou | The IoU predicted by SAM when generating masks, should not be considered as ground truth during training |

| Set | Images | Instances |

|---|---|---|

| Training | 11,132 | 23,304 |

| Validation | 1886 | 4708 |

| Test | 3624 | 8685 |

| Total | 16,642 | 36,697 |

| Dataset | Images | Instances | Ave. Words | Image Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RefSegRS | 4420 | 4420 | 3.09 | 512 × 512 |

| RRSIS-D | 17,402 | 17,402 | 6.80 | 800 × 800 * |

| RISORS | 16,642 | 36,697 | 7.45 | 800 × 800 |

| Dataset | Train | Val | Test | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RefSegRS | 2172 | 431 | 1817 | 4420 |

| RRSIS-D | 12,181 | 1740 | 3481 | 17,402 |

| RISORS | 23,304 | 4708 | 8685 | 36,697 |

| Methods | P@0.5 | P@0.6 | P@0.7 | P@0.8 | P@0.9 | oIoU | mIoU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSTM-CNN [26] | 15.69 | 10.57 | 5.17 | 1.10 | 0.28 | 53.83 | 24.76 |

| ConvLSTM [28] | 31.21 | 23.39 | 15.30 | 7.59 | 1.10 | 66.12 | 43.34 |

| CMSA [29] | 28.07 | 20.25 | 12.71 | 5.61 | 0.83 | 64.53 | 41.47 |

| BRINet [31] | 22.56 | 15.74 | 9.85 | 3.52 | 0.50 | 60.16 | 32.87 |

| LAVT [35] | 70.23 | 55.53 | 30.05 | 14.42 | 4.07 | 76.21 | 57.30 |

| LGCE [1] | 76.55 | 67.03 | 44.85 | 19.04 | 5.67 | 77.62 | 61.90 |

| RMSIN [22] | 73.25 | 59.88 | 34.07 | 12.27 | 2.37 | 72.64 | 59.07 |

| FIANet [23] | 81.29 | 69.73 | 48.60 | 20.20 | 3.63 | 75.85 | 64.12 |

| RSAM (Ours) | 80.77 | 72.86 | 61.76 | 39.40 | 8.63 | 76.21 | 68.48 |

| Methods | P@0.5 | P@0.6 | P@0.7 | P@0.8 | P@0.9 | oIoU | mIoU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNN [28] | 51.07 | 42.11 | 32.77 | 21.57 | 6.37 | 66.43 | 45.64 |

| CMSA [29] | 55.32 | 46.45 | 37.43 | 25.39 | 8.15 | 69.39 | 48.53 |

| LSCM [58] | 56.02 | 46.25 | 37.70 | 25.28 | 8.27 | 69.05 | 49.92 |

| CMPC [59] | 55.83 | 47.40 | 36.94 | 25.45 | 9.19 | 69.22 | 49.24 |

| BRINet [31] | 56.90 | 48.77 | 39.12 | 27.03 | 8.73 | 69.88 | 49.65 |

| CMPC+ [60] | 57.65 | 47.51 | 36.97 | 24.33 | 7.78 | 68.64 | 50.24 |

| LAVT [35] | 66.93 | 60.99 | 51.71 | 39.79 | 23.99 | 76.58 | 59.05 |

| LGCE [1] | 69.41 | 63.06 | 53.46 | 41.22 | 24.27 | 76.24 | 61.02 |

| RMSIN [22] | 72.34 | 64.72 | 52.60 | 39.39 | 21.00 | 76.21 | 62.62 |

| FIANet [23] | 73.97 | 67.19 | 55.93 | 41.71 | 23.50 | 76.88 | 63.41 |

| RSAM (Ours) | 78.85 | 73.54 | 63.61 | 48.51 | 29.85 | 78.25 | 67.58 |

| Category | RMSIN | FIANet | RSAM |

|---|---|---|---|

| vehicle | 46.08 | 46.84 | 54.16 |

| windmill | 58.54 | 59.54 | 63.24 |

| expressway toll station | 68.00 | 70.95 | 75.20 |

| airplane | 67.33 | 69.21 | 72.14 |

| tennis court | 68.52 | 69.87 | 74.48 |

| bridge | 48.42 | 48.03 | 53.63 |

| storage tank | 72.38 | 75.53 | 78.33 |

| harbor | 34.85 | 35.53 | 37.01 |

| basketball court | 67.35 | 66.39 | 68.76 |

| ship | 63.22 | 61.62 | 69.20 |

| baseball field | 83.92 | 85.24 | 85.30 |

| dam | 60.17 | 62.93 | 65.54 |

| train station | 61.88 | 63.79 | 65.28 |

| overpass | 60.26 | 61.49 | 63.57 |

| chimney | 77.97 | 77.11 | 81.53 |

| airport | 56.81 | 56.04 | 60.74 |

| expressway service area | 69.58 | 70.75 | 72.78 |

| ground track field | 74.86 | 75.04 | 81.74 |

| golf field | 75.52 | 76.80 | 77.21 |

| stadium | 82.10 | 83.66 | 81.85 |

| average | 64.89 | 65.82 | 69.08 |

| Methods | P@0.5 | P@0.6 | P@0.7 | P@0.8 | P@0.9 | oIoU | mIoU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSIN [22] | 75.46 | 70.71 | 63.37 | 51.77 | 32.84 | 80.38 | 67.15 |

| FIANet [23] | 75.19 | 70.39 | 63.50 | 52.46 | 33.70 | 79.59 | 67.04 |

| RSAM (Ours) | 80.17 | 77.24 | 72.61 | 64.87 | 46.80 | 81.84 | 72.80 |

| Category | RMSIN | FIANet | RSAM |

|---|---|---|---|

| windmill | 66.99 | 65.67 | 75.12 |

| vehicle | 55.85 | 56.77 | 65.61 |

| expressway toll station | 77.14 | 77.01 | 82.05 |

| airplane | 71.00 | 72.08 | 75.42 |

| harbor | 38.23 | 38.32 | 42.54 |

| bridge | 45.46 | 47.38 | 57.65 |

| tennis court | 75.25 | 75.43 | 79.63 |

| storage tank | 77.06 | 75.81 | 78.43 |

| ship | 69.21 | 68.17 | 75.79 |

| baseball field | 80.96 | 80.41 | 84.31 |

| basketball court | 73.45 | 74.97 | 77.51 |

| dam | 63.10 | 61.66 | 65.36 |

| airport | 65.55 | 65.93 | 67.81 |

| train station | 65.49 | 66.55 | 69.48 |

| overpass | 59.24 | 59.00 | 63.97 |

| chimney | 78.06 | 75.85 | 79.90 |

| expressway service area | 75.18 | 74.56 | 77.74 |

| ground track field | 75.11 | 75.38 | 79.34 |

| stadium | 85.18 | 85.64 | 87.01 |

| average | 68.45 | 68.24 | 72.88 |

| Methods | Total Params | Trainable Params | FLOPs |

|---|---|---|---|

| RMSIN | 240 M | 240 M | 204 G |

| FIANet | 251 M | 251 M | 210 G |

| RSAM | 194 M | 86 M | 280 G |

| TWGM | MMMD | P@0.5 | P@0.6 | P@0.7 | P@0.8 | P@0.9 | oIoU | mIoU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 77.00 | 73.77 | 68.97 | 60.80 | 43.04 | 78.68 | 69.73 | ||

| √ | 78.60 | 75.19 | 70.48 | 62.39 | 43.92 | 80.09 | 71.27 | |

| √ | 79.25 | 76.03 | 71.32 | 63.19 | 45.49 | 80.31 | 71.71 | |

| √ | √ | 80.17 | 77.24 | 72.61 | 64.87 | 46.80 | 81.84 | 72.80 |

| Module | Text Encoder | Image Encoder | Total Params | Trainable Params | oIoU | mIoU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| base+ | 194 M | 194 M | 81.76 | 72.75 | ||

| base+ | * | 194 M | 85.7 M | 81.84 | 72.80 | |

| base+ | * | * | 194 M | 16.6 M | 78.30 | 67.88 |

| large | 338 M | 338 M | 80.44 | 70.70 | ||

| large | * | 338 M | 229 M | 80.70 | 72.22 | |

| large | * | * | 338 M | 16.6 M | 77.60 | 67.19 |

| Dataset | P@0.5 | P@0.6 | P@0.7 | P@0.8 | P@0.9 | oIoU | mIoU | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base+ | Large | Base+ | Large | Base+ | Large | Base+ | Large | Base+ | Large | Base+ | Large | Base+ | Large | |

| RefSegRS | 80.77 | 83.79 | 72.86 | 76.65 | 61.76 | 66.92 | 39.40 | 48.63 | 8.63 | 13.90 | 76.21 | 76.66 | 68.48 | 71.65 |

| RRSIS-D | 78.85 | 75.29 | 73.54 | 71.13 | 63.61 | 61.83 | 48.51 | 47.50 | 29.85 | 28.65 | 78.25 | 74.26 | 67.58 | 64.85 |

| RISORS | 80.17 | 79.14 | 77.24 | 76.17 | 72.61 | 72.09 | 64.87 | 64.70 | 46.80 | 46.17 | 81.84 | 80.70 | 72.80 | 72.22 |

| Number of Points | P@0.5 | P@0.6 | P@0.7 | P@0.8 | P@0.9 | oIoU | mIoU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 80.17 | 77.24 | 72.61 | 64.87 | 46.80 | 81.84 | 72.80 |

| 1 | 97.34 | 95.35 | 91.78 | 83.90 | 61.54 | 91.21 | 88.38 |

| 2 | 98.54 | 97.16 | 94.76 | 88.14 | 65.93 | 93.09 | 90.04 |

| Dataset | RMSIN | FIANet | RSAM | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| oIoU | mIoU | oIoU | mIoU | oIoU | mIoU | |

| RefSegRS | 72.64 | 59.07 | 75.85 | 64.12 | 76.21 | 68.48 |

| RRSIS-D | 76.21 | 62.62 | 76.88 | 63.41 | 78.25 | 67.58 |

| RISORS | 80.38 | 67.15 | 79.59 | 67.04 | 81.84 | 72.80 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, Z.; Xu, X.; Huang, B.; Chen, H.; Pu, F. RSAM: Vision-Language Two-Way Guidance for Referring Remote Sensing Image Segmentation. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3960. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243960

Zhao Z, Xu X, Huang B, Chen H, Pu F. RSAM: Vision-Language Two-Way Guidance for Referring Remote Sensing Image Segmentation. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):3960. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243960

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Zilong, Xin Xu, Bingxin Huang, Hongjia Chen, and Fangling Pu. 2025. "RSAM: Vision-Language Two-Way Guidance for Referring Remote Sensing Image Segmentation" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 3960. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243960

APA StyleZhao, Z., Xu, X., Huang, B., Chen, H., & Pu, F. (2025). RSAM: Vision-Language Two-Way Guidance for Referring Remote Sensing Image Segmentation. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 3960. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243960