Decrypting Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Optimization Pathway of Ecological Resilience Under a Panarchy-Inspired Framework: Insights from the Wuhan Metropolitan Area

Highlights

- A nested local–global assessment (2000–2020) revealed a slight decline in ecological resilience, with notable east–west disparities.

- Integrating XGBoost-SHAP with DBN uncovered the evolving causal network of ecological resilience and pinpointed forest and construction land as key drivers.

- Provides a panarchy-inspired framework using remote sensing, offering a new tool for assessing and managing ecological resilience across scales.

- The framework provides transferable guidance for sustainable land management in rapidly urbanizing regions.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Foundations of the Theoretical Framework

2.1. Connotation of the Substrate Resilience

2.2. Theoretical Framework: Panarchy-Inspired Ecological Resilience Assessment

3. Study Area and Data Source

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Data Source

4. Methods

4.1. Nested Ecological Resilience Assessment

4.1.1. Local Substrate Resilience: “Resistance–Recovery–Adaptation”

4.1.2. Global Resilience Modification: “Structure–Quality–Function”

- (1)

- Ecological Network

- (2)

- Network Resilience

4.1.3. Nested Ecological Resilience: Cross-Spatial Scale Calculation

4.2. Driving Mechanism of Ecological Resilience Based on Hybrid Machine Learning

4.2.1. Preliminary Selection of Driving Factors Based on XGBoost-SHAP

4.2.2. Dynamic Bayesian Network: Resilience Modeling Across Time Scales

4.3. Multi-Scenario Optimization of Land Use from the Perspective of Ecological Resilience Improvement

5. Results

5.1. Ecological Resilience Assessment and Spatiotemporal Evolution

5.1.1. Evolution Characteristics of Local Ecological Resilience Based on the “Resistance–Adaptation–Recovery” Model

5.1.2. Evolution Characteristics of Global Ecological Resilience Based on Complex Networks

5.1.3. Evolution of Comprehensive Ecological Resilience

5.2. Driving Mechanism of Ecological Resilience

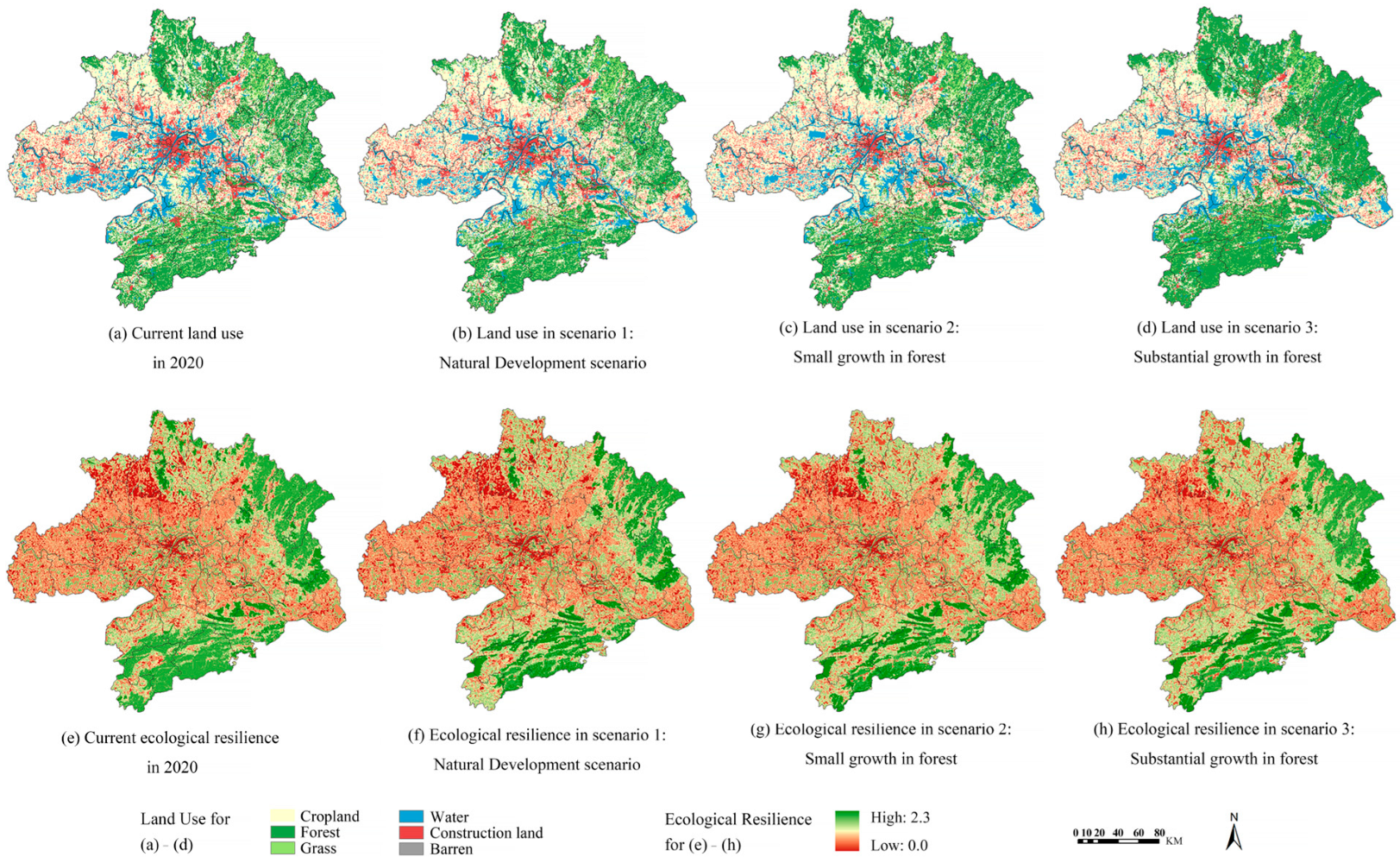

5.3. Multi-Scenario Ecological Spatial Optimization Based on DBN and PLUS Models

6. Discussion

6.1. Advancing Spatial Resilience Assessment: From Local Attributes to Panarchy in Cross-Scale Framework

6.2. Spatiotemporal Responses of Ecological Resilience to Socio–Natural–Spatial Drivers

6.3. Policy Implications and Advantages of Enhancing Ecological Resilience Using the DBN-PLUS Framework

- (1)

- Conservation-oriented land use planning should aim to optimize both land use quantity and spatial configuration [93]. Policy-making should employ scenario analysis to anticipate land cover impacts on resilience and proactively designate ecological buffer zones and protected areas to mitigate future disturbances [94]. Future policies should more strictly control unregulated urban expansion and promote ecological restoration programs such as natural forest conservation, reforestation, and greening of previously developed land, especially in peri-urban transition zones of high conservation value. These actions should be embedded in a robust and flexible governance framework that supports multi-objective spatial coordination to ensure effectiveness.

- (2)

- Ecological engineering should aim to increase the number and diversity of green patches to improve landscape heterogeneity, evenness, and connectivity—a strategy directly supported by our findings that increased patch density and Shannon evenness enhance resilience. Specific measures include: restoring wetlands, grasslands, or forests in farmland areas can diversify landscape elements [95,96] and moderately fragmenting large forest patches to create canopy gaps that can increase edge effects and biodiversity [97]. In high-density urban areas, the construction of parks, green roofs, and ecological nodes, as well as the establishment of green wedges and corridors, can enhance landscape connectivity [98].

- (3)

- Another policy orientation is to incorporate DBN for long-term monitoring and adaptive policy adjustment, while fostering cross-sectoral collaboration among conservation agencies, planning departments, and regional governance bodies. Given the adaptive nature of ER, DBN models enable a shift from static assessments to ongoing, real-time monitoring, informing long-term protection and restoration strategies [46]. Furthermore, by integrating diverse natural and socio-economic variables and incorporating stakeholder feedback, DBN can promote interdepartmental communication and the integration of multiple planning approaches [73]. We recommend establishing a cross-departmental platform centered on DBN outcomes to institutionalize this collaborative approach.

6.4. Deficiencies and Prospects

7. Conclusions

- (1)

- ER exhibited a distinct spatial gradient characterized by higher values in the east and lower values in the west. ER remained relatively stable, with a slight decline from 0.4856 in 2000 to 0.4503 in 2020. Forest land demonstrated higher resilience due to its ecological value and role as habitat space.

- (2)

- Elevation and spatial pattern factors—particularly spatial composition and structure—were identified as the dominant drivers of ER. Among these, the proportion of forest land had a significant positive impact, while higher proportions of cropland and construction land suppressed ER.

- (3)

- The key drivers of ER exhibited time-lag effects, and by maintaining DBN-identified spatial composition variables within critical thresholds, future land use layouts can increase the probability of ER enhancement.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ER | Ecological Resilience |

| EN | Ecological Network |

| ES | Ecosystem Service |

| DBN | Dynamic Bayesian Network |

| GA | Genetic Algorithm |

| PLUS | Patch-Generating Land Use Simulation |

| BNs | Bayesian Networks |

| WMA | Wuhan Metropolitan Area |

| LEAS | Land Expansion Analysis Strategy |

| CARS | Multitype Random Patch Seed Cellular Automata Model |

| EM | Expectation-Maximization Algorithm |

| CPTs | Conditional Probability Tables |

| BIC | Bayesian Information Criterion |

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| NPP | Net Primary Production |

| DEM | Digital Elevation Model |

| GDP | Gross national Product |

References

- Huang, A.; Wang, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Tian, L.; Zhou, G.; Zhuang, Y.; Zhu, L. A comprehensive framework for assessing spatial conflicts risk: A case study of production-living-ecological spaces based on social-ecological system framework. Habitat Int. 2024, 154, 103218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Peng, S.; Ma, X.; Lin, Z.; Ma, D.; Shi, S.; Gong, L.; Huang, B. Identification of potential conflicts in the production-living-ecological spaces of the Central Yunnan Urban Agglomeration from a multi-scale perspective. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 165, 112206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Gu, T.; Xiang, J.; Luo, T.; Zeng, J.; Yuan, Y. Ecological restoration zoning of territorial space in China: An ecosystem health perspective. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 364, 121371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Cheng, S.; Xu, K.; Qian, Y. Ecological network resilience evaluation and ecological strategic space identification based on complex network theory: A case study of Nanjing city. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 158, 111604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohr, J.R.; Bernhardt, E.S.; Cadotte, M.W.; Clements, W.H. The ecology and economics of restoration: When, what, where, and how to restore ecosystems. Ecol. Soc. 2018, 23, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.W.F.; Coffman, G.C. Integrating the resilience concept into ecosystem restoration. Restor. Ecol. 2023, 31, e13907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Song, Y.; Xue, D.; Ma, B.; Liu, X.; Zhang, L. Spatial and Temporal Changes in Ecological Resilience in the Shanxi–Shaanxi–Inner Mongolia Energy Zone with Multi-Scenario Simulation. Land 2024, 13, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Xu, L.; Zhao, D.; Xu, T.; Lei, P. A new model for describing the urban resilience considering adaptability, resistance and recovery. Saf. Sci. 2020, 128, 104756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, Z.; Long, Y.; Yang, L.; Ding, X.; Sun, X.; Chen, T. Impacts of urbanization on the spatiotemporal evolution of ecological resilience in the Plateau Lake Area in Central Yunnan, China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 160, 111836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, G.S.; Peterson, G.D. Unifying Research on Social–Ecological Resilience and Collapse. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2017, 32, 695–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, G.S. Spatial resilience: Integrating landscape ecology, resilience, and sustainability. Landsc. Ecol. 2011, 26, 899–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Yan, J.; Li, T. Ecological resilience of city clusters in the middle reaches of Yangtze river. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 443, 141082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Xu, X.; Tan, Y.; Lin, Y. Assessing ecological vulnerability and resilience-sensitivity under rapid urbanization in China’s Jiangsu province. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 167, 112607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batabyal, A.A. On some aspects of ecological resilience and the conservation of species. J. Environ. Manag. 1998, 52, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Xie, Y.; Chen, L.; Cai, Y. Machine learning insights into the evolution of flood Resilience: A synthesized framework study. J. Hydrol. 2024, 643, 131991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Xie, Y.; Chen, L.; Li, Y. Toward explainable flood risk prediction: Integrating a novel hybrid machine learning model. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 120, 106140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Feng, H.; Arashpour, M.; Zhang, F. Enhancing urban flood resilience: A coupling coordinated evaluation and geographical factor analysis under SES-PSR framework. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 101, 104243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Liu, D.; Tian, Y.; Fu, C.; Li, J.; Ju, P.; Sun, P.; Ye, Z.; Liu, Y.; Watanabe, Y. Critical transitions and ecological resilience of large marine ecosystems in the Northwestern Pacific in response to global warming. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 5310–5328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Ru, X.; Gao, T.; Moore, J.M.; Yan, G. Early Predictor for the Onset of Critical Transitions in Networked Dynamical Systems. Phys. Rev. X 2024, 14, 031009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Li, Z.; Ma, J.; Zhou, M.; Chen, L.; Peng, J. Ecosystem resilience response to forest fragmentation in China: Thresholds identification. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 380, 125180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, L.M.; Irvine, K.N.; Beza, B.B.; Chua, L.H.C. Adaptive resilience in wetlands: An integrative review of principles, research gaps, and ways forward for better adaptive management. Ecol. Eng. 2025, 220, 107720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camini, N.; Bachi, L.; Ribeiro, S.C.; Da Costa, A.M. Traditional Management Practices and Multifunctional Land-Use Systems in Tropical Landscapes: Contributions to Ecosystem Services and Food System Resilience. Curr. Landsc. Ecol. Rep. 2025, 10, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datola, G. Implementing urban resilience in urban planning: A comprehensive framework for urban resilience evaluation. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 98, 104821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xu, F.; Gao, C.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Gao, J. Deep learning resilience inference for complex networked systems. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Q.; Li, Q.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Du, Y.; Zhang, Y. Evaluation and optimization of ecological spatial resilience of Yanhe River Basin based on complex network theory. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yan, W. Service flow changes in multilayer networks: A framework for measuring urban disaster resilience based on availability to critical facilities. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2024, 244, 104996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Zeng, F.; Loo, B.P.Y.; Zhong, Y. The evolution of urban ecological resilience: An evaluation framework based on vulnerability, sensitivity and self-organization. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 116, 105933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, S. Multi-criteria assessment of the resilience of ecological function areas in China with a focus on ecological restoration. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 119, 106862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, E.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J. Measuring Urban Infrastructure Resilience via Pressure-State-Response Framework in Four Chinese Municipalities. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.R.; Angeler, D.G.; Chaffin, B.C.; Twidwell, D.; Garmestani, A. Resilience reconciled. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 898–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.; Liu, Q.; Wang, P. Spatiotemporal characteristics of ecological resilience and its influencing factors in the Yellow River Basin of China. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Bai, Z.; Zhang, J.; Xu, C. Increasing urban ecological resilience based on ecological security pattern: A case study in a resource-based city. Ecol. Eng. 2022, 175, 106486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, H.; Duan, Z.; Zhou, G. Exploring the impacts of urbanization on ecological resilience from a spatiotemporal heterogeneity perspective: Evidence from 254 cities in China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Xu, M.; Zhong, Y.; Li, Q.; Loo, B.P.Y.; Xiu, C. Urban resilience and panarchy: Insights from Nanchang City, China. Cities 2025, 162, 105934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beita, C.M.; Murillo, L.F.S.; Alvarado, L.D.A. Ecological corridors in Costa Rica: An evaluation applying landscape structure, fragmentation-connectivity process, and climate adaptation. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2021, 3, e475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, P.; Zhou, L.; Sun, Y. Estimating the nonlinear response of landscape patterns to ecological resilience using a random forest algorithm: Evidence from the Yangtze River Delta. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 153, 110409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Li, B.; Kong, F.; He, T. Spatial-temporal variation, driving mechanism and management zoning of ecological resilience based on RSEI in a coastal metropolitan area. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 158, 111447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Yin, X.; Shao, M. Natural and anthropogenic factors on China’s ecosystem services: Comparison and spillover effect perspective. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 324, 116064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, A.; Spaan, R.S.; Peterson, J.T.; Pearl, C.A.; Adams, M.J. Bayesian networks facilitate updating of species distribution and habitat suitability models. Ecol. Model. 2025, 501, 110982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ma, X.; Luo, G. Trade-offs and synergistic relationships on soil-related ecosystem services in Central Asia under land use and land cover change. Land Degrad. Dev. 2024, 35, 5011–5028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahlin, U.; Helle, I.; Perepolkin, D. “This Is What We Don’t Know”: Treating Epistemic Uncertainty in Bayesian Networks for Risk Assessment. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2020, 17, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linkov, I.; Trump, B.D. Resilience as Function of Space and Time. In The Science and Practice of Resilience; Linkov, I., Trump, B.D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 9–34. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, X.; Zhou, F.; Chen, J. Spatiotemporal Heterogeneity and Zoning Strategies for Urban Ecological Resilience in Yichang, China. Land Degrad. Dev. 2025, 36, 5957–5975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, S.; Yang, F. Ecological resilience in water-land transition zones: A case study of the Dongting Lake region, China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 166, 112284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Xue, J.; Zhao, J.; Feng, X.; Sun, H.; Tang, J.; Chang, J. Dynamic Bayesian networks for spatiotemporal modeling and its uncertainty in tradeoffs and synergies of ecosystem services: A case study in the Tarim River Basin, China. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2024, 38, 4311–4329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco-Gaviria, F.; Amador-Jiménez, M.; Millner, N.; Durden, C.; Urrego, D.H. Quantifying resilience of socio-ecological systems through dynamic Bayesian networks. Front. Glob. Change 2022, 5, 889274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhang, K.; Liu, Q.; He, Q.; van de Koppel, J.; Teng, S.N.; Miao, X.; Liu, M.; Bertness, M.D.; Xu, C. Long-distance facilitation of coastal ecosystem structure and resilience. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2123274119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Peng, L.; Li, S.; Yue, Y.; Wang, K. Integrating transfer entropy and network analysis to explore social-ecological resilience evolution: A case study in South China Karst. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 518, 145926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, G.S.; Morrison, T.H.; Hughes, T.P. New Directions for Understanding the Spatial Resilience of Social ecological Systems. Ecosystems 2017, 20, 649–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; He, Q. Spatio-temporal evaluation of the urban agglomeration expansion in the middle reaches of the Yangtze River and its impact on ecological lands. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 790, 148150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Zeng, P.; Guo, Y.; Shen, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, K.; Zhang, L. Decoding the spatiotemporal dynamics and driving mechanisms of ecological resilience in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei urban agglomeration: A deep learning approach. Urban Clim. 2025, 61, 102436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yin, L.; Zhang, B. Potential heterogeneity of urban ecological resilience and urbanization in multiple urban agglomerations from a landscape perspective. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 342, 118129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ge, Q. Ecological resilience of three major urban agglomerations in China from the “environment–society” coupling perspective. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 169, 112944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Yan, K.; Shi, Y.; Lv, T.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X. Decrypting resilience: The spatiotemporal evolution and driving factors of ecological resilience in the Yangtze River Delta Urban Agglomeration. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2024, 106, 107540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wang, L. Study of regional variations and convergence in ecological resilience of Chinese cities. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.S. Understanding the Complexity of Economic, Ecological, and Social Systems. Ecosystems 2001, 4, 390–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linkov, I.; Trump, B.D. Panarchy: Thinking in Systems and Networks. In The Science and Practice of Resilience; Linkov, I., Trump, B.D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Challies, E.; Newig, J.; Lenschow, A. What role for social–ecological systems research in governing global teleconnections? Glob. Environ. Change 2014, 27, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelleri, L.; Waters, J.J.; Olazabal, M.; Minucci, G. Resilience trade-offs: Addressing multiple scales and temporal aspects of urban resilience. Environ. Urban. 2015, 27, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Bai, Y.; Xue, J.; Gong, L.; Zeng, F.; Sun, H.; Hu, Y.; Huang, H.; Ma, Y. Dynamic Bayesian networks with application in environmental modeling and management: A review. Environ. Model. Softw. 2023, 170, 105835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeler, D.G.; Heino, J.; Rubio-Ríos, J.; Casas, J.J. Connecting distinct realms along multiple dimensions: A meta-ecosystem resilience perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 889, 164169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z. Reconceptualizing urban heat island: Beyond the urban-rural dichotomy. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 77, 103581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, Z.; Li, Q. Emergence of urban clustering among U.S. cities under environmental stressors. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 63, 102481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, Z. A network-based toolkit for evaluation and intercomparison of weather prediction and climate modeling. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 268, 110709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hu, W.; Min, M.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, S.; Liu, T. Optimization of ecological connectivity and construction of supply-demand network in Wuhan Metropolitan Area, China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 146, 109799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.A.; Bodin, Ö.; Anderies, J.M.; Elmqvist, T.; Ernstson, H.; McAllister, R.R.J.; Olsson, P.; Ryan, P. Toward a network perspective of the study of resilience in social-ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 2006, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Ouyang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Z. Multidimensional Bird Habitat Network Resilience Assessment and Ecological Strategic Space Identification in International Wetland City. Land 2025, 14, 1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Hu, Y.; Bai, Y. Construction of ecological security pattern in national land space from the perspective of the community of life in mountain, water, forest, field, lake and grass: A case study in Guangxi Hechi, China. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 139, 108867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, H.; Zhang, J.; Mao, D.; Wang, M.; Yu, F.; Wang, Z.; Li, H. Optimizing ecological security patterns considering zonal vegetation distribution for regional sustainability. Ecol. Eng. 2023, 194, 107055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.Y.; Wang, J.; Cheng, H.G. Spatiotemporal changes in ecological network resilience in the Shandong Peninsula urban agglomeration. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 339, 130681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, P.J.G.; Pena Jardim Gonçalves, L.A. Urban resilience: A conceptual framework. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 50, 101625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, C.; Liu, M.; Cui, Q.; Wang, H.; LV, J.; Li, B.; Xiong, Z.; Hu, Y. Spatial characteristics and driving factors of urban flooding in Chinese megacities. J. Hydrol. 2022, 613, 128464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Jiang, J.; Gu, X.; Cao, C.; Shen, C. Using dynamic Bayesian belief networks to infer the effects of climate change and human activities on changes in regional ecosystem services. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 170, 113023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruk, M. SHAP-NET, a network based on Shapley values as a new tool to improve the explainability of the XGBoost-SHAP model for the problem of water quality. Environ. Model. Softw. 2025, 188, 106403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Tao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, J.; Bai, X. Use of interpretable machine learning for understanding ecosystem service trade-offs and their driving mechanisms in karst peak-cluster depression basin, China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 166, 112474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L. Performance evaluation model for operation research teaching based on IoT and Bayesian network technology. Soft Comput. 2024, 28, 3613–3631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colesanti Senni, C.; Goel, S. Nature scenario plausibility: A dynamic Bayesian network approach. Ecol. Econ. 2025, 236, 108647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.; Zhang, W.; Ma, L.; Wu, Y.; Yan, K.; Lu, H.; Sun, J.; Wu, X.; Yuan, B. An efficient Bayesian network structure learning algorithm based on structural information. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2023, 76, 101224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Qin, M.; Wu, X.; Luo, D.; Ouyang, H.; Liu, Y. Spatiotemporal evolution and driving factors of ecosystem service bundle based on multi-scenario simulation in Beibu Gulf urban agglomeration, China. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wang, S.; Rong, W. Construction of ecological network in Suzhou based on the PLUS and MSPA models. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Kong, W.; Wang, L.; Wang, T.; Luo, P.; Cui, J. A novel and dynamic land use/cover change research framework based on an improved PLUS model and a fuzzy multiobjective programming model. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 80, 102460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kéfi, S.; Saade, C.; Berlow, E.L.; Cabral, J.S.; Fronhofer, E.A. Scaling up our understanding of tipping points. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2022, 377, 20210386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huo, H.; Liu, P.; Li, S.; Hou, W.; Xu, W.; Wen, X.; Bai, Y. Study on the Spatiotemporal Evolution Relationship Between Ecological Resilience and Land Use Intensity in Hebei Province and Scenario Simulation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L.; Ma, E.; Long, H.; Peng, X. Land Use Transition and Its Ecosystem Resilience Response in China during 1990–2020. Land 2022, 12, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Fang, C.; Liu, J.; Zhang, L. The evaluation and obstacle analysis of urban resilience from the multidimensional perspective in Chinese cities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 86, 104160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cushman, S.A.; McGarigal, K. Metrics and Models for Quantifying Ecological Resilience at Landscape Scales. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 7, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.; Fu, H.; Jin, W. Landscape Pattern Changes and Ecological Vulnerability Assessment in Mountainous Regions: A Multi-Scale Analysis of Heishui County, Southwest China. Land 2025, 14, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Geng, H. Investigating of Spatiotemporal Correlation between Urban Spatial Form and Urban Ecological Resilience: A Case Study of the City Cluster in the Yangzi River Midstream, China. Buildings 2024, 14, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Xie, C.; Liu, J. The impact of population agglomeration on ecological resilience: Evidence from China. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2023, 20, 15898–15917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, Z.; Wu, W.; Yu, L. Effects of landscape pattern change on ecosystem services and its interactions in karst cities: A case study of Guiyang City in China. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 145, 109646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.R.; Angeler, D.G.; Cumming, G.S.; Folke, C.; Twidwell, D.; Uden, D.R. Quantifying spatial resilience. J. Appl. Ecol. 2016, 53, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Lei, F.; Zeng, H.; Xie, L.; Ouyang, X. Estimating non-linear effects of natural and anthropogenic factors on ecological resilience: Evidence from the southern hilly areas. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Zhao, X.; Pu, J.; Gu, Z.; Ran, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wu, B.; Dong, W.; Qu, G.; Xiong, B.; et al. Defining the land use area threshold and optimizing its structure to improve supply-demand balance state of ecosystem services. J. Geogr. Sci. 2024, 34, 891–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, J.; Gochfeld, M.; Brown, K.G.; Ng, K.; Cortes, M.; Kosson, D. The importance of recognizing Buffer Zones to lands being developed, restored, or remediated: On planning for protection of ecological resources. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part A 2023, 87, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, B.; Lei, K.; Wu, Y.; Wei, D.; Zhang, B. Assessing rural landscape diversity for management and conservation: A case study in Lichuan, China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 27, 14523–14551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ye, X.; Wang, A. Dynamic Changes in Landscape Pattern of Mangrove Wetland in Estuary Area Driven by Rapid Urbanization and Ecological Restoration: A Case Study of Luoyangjiang River Estuary in Fujian Province, China. Water 2023, 15, 1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, F.; Fahrig, L. Landscape-scale habitat fragmentation is positively related to biodiversity, despite patch-scale ecosystem decay. Ecol. Lett. 2022, 26, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumia, G.; Praticò, S.; Di Fazio, S.; Cushman, S.; Modica, G. Combined use of urban Atlas and Corine land cover datasets for the implementation of an ecological network using graph theory within a multi-species approach. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 148, 110150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakos, V.; Kéfi, S. Ecological resilience: What to measure and how. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 043003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MEA. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; pp. 1–137. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, G.; Liu, S.; Liu, W.; Wu, X. Nonlinear trade-off relationship and critical threshold between ecosystem services and climate resilience for sustainable urban development. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 103, 105253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, P.; Hu, S.; Frazier, A.E.; Yang, S.; Song, X.; Qu, S. The dynamic relationships between landscape structure and ecosystem services: An empirical analysis from the Wuhan metropolitan area, China. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 325, 116575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Yuan, S.; Prishchepov, A.V. Spatial-temporal heterogeneity of ecosystem service interactions and their social-ecological drivers: Implications for spatial planning and management. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 189, 106767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Cui, W.; Yang, F. Spatiotemporal variations and driving forces analysis of ecosystem water conservation in coastal areas of China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 162, 112019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Z.; Zheng, H.; Xiao, Y.; Polasky, S.; Liu, J.; Xu, W.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Xiao, Y.; Rao, E.; et al. Improvements in ecosystem services from investments in natural capital. Science 2016, 352, 1455–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Yan, W.; Li, Z.; Wende, W.; Xiao, S. A framework for integrating ecosystem service provision and connectivity in ecological spatial networks: A case study of the Shanghai metropolitan area. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 100, 105018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Deng, W.; Yang, J.; Huang, W.; de Vries, W.T. Construction and optimization of ecological security patterns based on social equity perspective: A case study in Wuhan, China. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 136, 108714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottero, M.; Comino, E.; Riggio, V. Application of the Analytic Hierarchy Process and the Analytic Network Process for the assessment of different wastewater treatment systems. Environ. Modell. Softw. 2011, 26, 1211–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.Y.; Wang, Y.W.; Li, C.Y. A Dual-Layer Complex Network-Based Quantitative Flood Vulnerability Assessment Method of Transportation Systems. Land 2024, 13, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, T.; Qu, Z. Constructing an Ecological Spatial Network Optimization Framework from the Pattern–Process–Function Perspective: A Case Study in Wuhan. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.J.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, F.Q.; Xia, Y.P. Multi-scenario simulation prediction of land use in Nanchang based on network robustness analysis. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 167, 112599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Q.; Zheng, Y.P.; Yang, Y.; Ren, H.; Liu, J.W. Spatiotemporal evolution of ecological vulnerability on the Loess Plateau. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 170, 113060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Liu, Y.; Wu, J.; Lv, H.; Hu, X. Linking ecosystem services and landscape patterns to assess urban ecosystem health: A case study in Shenzhen City, China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 143, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Kong, X.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, B. A study on land use change simulation based on PLUS model and the U-net structure: A case study of Jilin Province. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 176, 113619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cao, P.; Roosli, R. Assessing land use and carbon storage changes using PLUS and InVEST models: A multi-scenario simulation in Hohhot. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2025, 26, 100655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data | Data Format | Spatial Resolution | Data Sources/Processing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) | Raster | 1 km | EARTHDATA (https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/ (accessed on 28 June 2024)) |

| Precipitation | Raster | 1 km | National Tibetan Plateau Data Center (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/zh-hans/data/faae7605-a0f2-4d18-b28f-5cee413766a2 (accessed on 28 June 2024)) |

| Temperature | Raster | 1 km | China Meteorological Data Service Centre, National Meteorological Information Centre (https://data.cma.cn/ (accessed on 28 June 2024)) |

| Evapotranspiration | Raster | 1 km | National Tibetan Plateau Data Center (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/zh-hans/data/faae7605-a0f2-4d18-b28f-5cee413766a2 (accessed on 20 November 2024)) |

| Soil data | Raster | 1 km | Harmonized World Soil Database (HWSD) version 2, International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) (https://gaez.fao.org/pages/hwsdhttps://iiasa.ac.at/ (accessed on 22 July 2024)) |

| Net Primary Production (NPP) | Raster | 500 m | NASA MODIS_MOD17A3 (https://search.earthdata.nasa.gov/search (accessed on 1 July 2024)) |

| Land use data | Raster | 30 m | Resource and Environmental Science Data Platform, Chinese Academy of Sciences (https://www.resdc.cn/ (accessed on 21 July 2024)) |

| Digital elevation model (DEM) | Raster | 30 m | Geospatial Data Cloud (http://www.gscloud.cn (accessed on 20 November 2024)) |

| Slope | Raster | 30 m | Calculated in ArcGIS |

| Road | Vector | - | Open Street Map (http://www.openstreetmap.org (accessed on 21 July 2024)) |

| Population density | Raster | 1 km | EARTHDATA (https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/ (accessed on 22 July 2024)) |

| Gross national product (GDP) | Raster | 1 km | Resource and Environmental Science Data Platform, Chinese Academy of Sciences (http://www.resdc.cn/DOI),2017.DOI:10.12078/2017121102 (accessed on 20 November 2024)) |

| Nighttime lighting | Raster | 500 m | NPP-VIIRS-like nighttime light data (https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/YGIVCD (accessed on 20 November 2024)) |

| Land Use Type | Proportion of Land Types in Different Scenarios | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current | Scenario 1: Natural Development | Scenario 2: Moderate Forest Expansion | Scenario 3: Large Forest Expansion | |

| Cropland | 0.4913 | 0.4767 | 0.4622 | 0.4060 |

| Forest | 0.3001 | 0.2978 | 0.3299 | 0.3862 |

| Water | 0.1046 | 0.1055 | 0.1046 | 0.1046 |

| Construction land | 0.0761 | 0.0926 | 0.0761 | 0.0761 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tong, A.; Zhou, Y.; Zheng, J.; Liu, Z. Decrypting Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Optimization Pathway of Ecological Resilience Under a Panarchy-Inspired Framework: Insights from the Wuhan Metropolitan Area. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3941. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243941

Tong A, Zhou Y, Zheng J, Liu Z. Decrypting Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Optimization Pathway of Ecological Resilience Under a Panarchy-Inspired Framework: Insights from the Wuhan Metropolitan Area. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):3941. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243941

Chicago/Turabian StyleTong, An, Yan Zhou, Jiazi Zheng, and Ziqi Liu. 2025. "Decrypting Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Optimization Pathway of Ecological Resilience Under a Panarchy-Inspired Framework: Insights from the Wuhan Metropolitan Area" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 3941. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243941

APA StyleTong, A., Zhou, Y., Zheng, J., & Liu, Z. (2025). Decrypting Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Optimization Pathway of Ecological Resilience Under a Panarchy-Inspired Framework: Insights from the Wuhan Metropolitan Area. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 3941. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243941