TAF-YOLO: A Small-Object Detection Network for UAV Aerial Imagery via Visible and Infrared Adaptive Fusion

Highlights

- An early-fusion multimodal small-object detection framework, TAF-YOLO, is proposed for UAV aerial imagery. It effectively integrates complementary visible and infrared information at the pixel level, thereby improving small-object detection accuracy while reducing missed detections and false alarms.

- TAF-YOLO removes the PANet from the baseline model, reduces redundant information and introduces lightweight DSAB into a multimodal detection framework, achieving efficient and accurate detection of small objects.

- The proposed framework shows that early fusion of visible and infrared modalities improves robustness and precision in UAV-based small-object detection, suggesting a promising direction for multimodal sensing in complex environments.

- The integration of lightweight modules and removal of redundant network structures provide evidence that high detection accuracy can be achieved with reduced computational cost, supporting broader deployment in real-time and resource-constrained scenarios.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We propose TAF-YOLO, a novel end-to-end multimodal fusion framework specifically engineered for robust small-object detection in complex UAV scenarios. By integrating a series of targeted optimizations, the framework achieves state-of-the-art accuracy among YOLO-based visible–infrared models while maintaining a UAV-friendly computational budget.

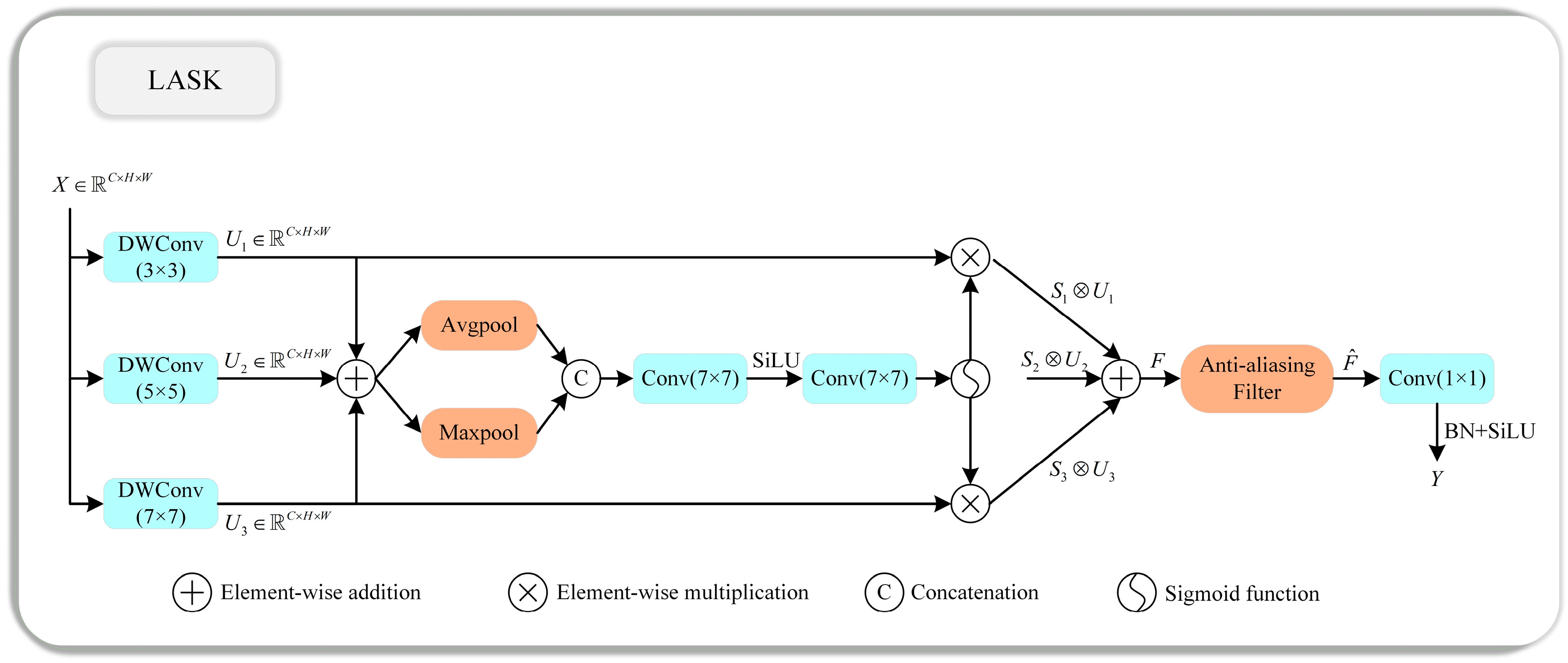

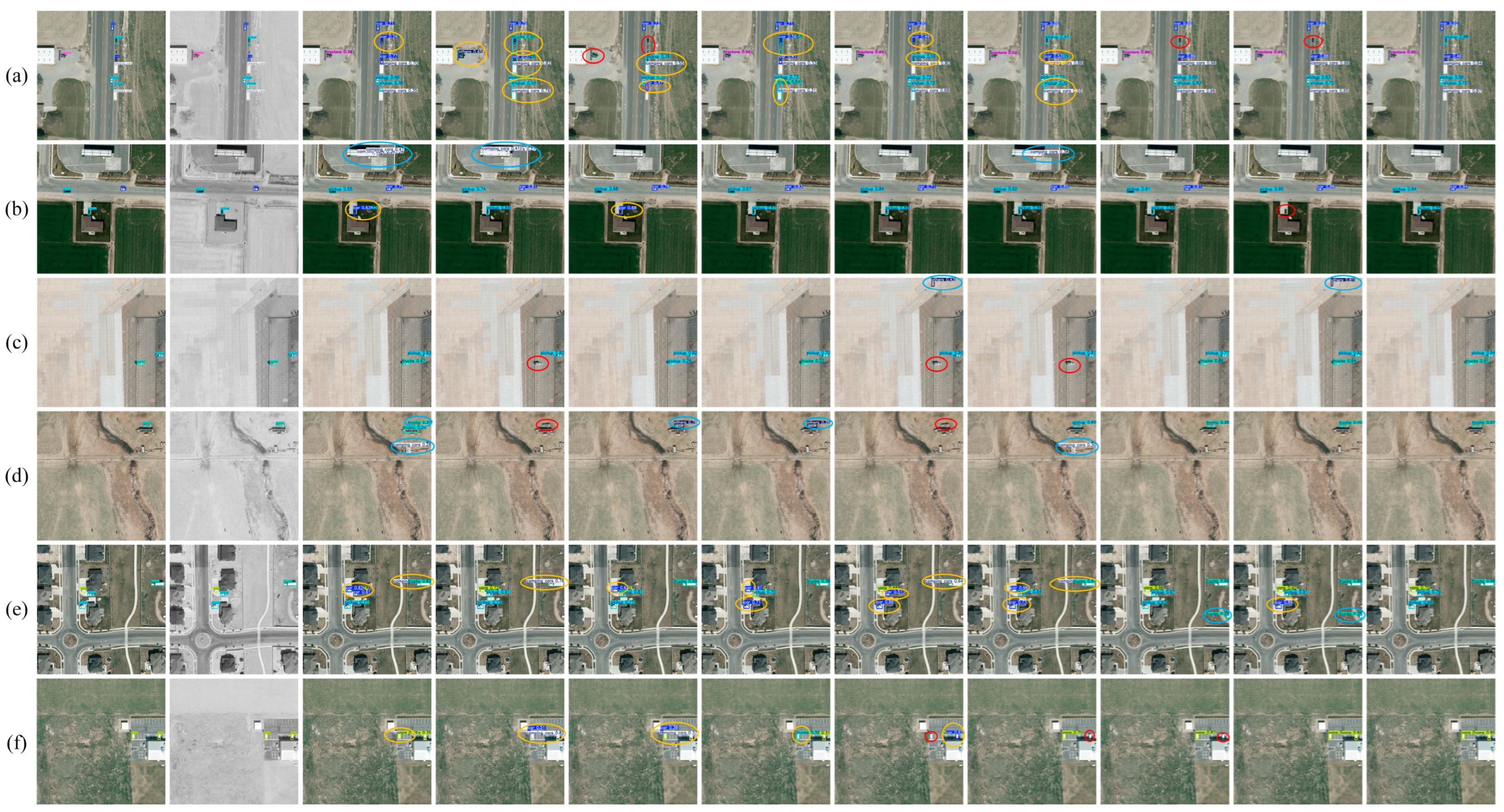

- To overcome ineffective early fusion and feature degradation during downsampling in multimodal feature fusion and propagation, we introduce a set of innovative modules. We introduce an efficient early fusion network, TAFNet, to maximize modal complementarity while preserving critical details at the input stage; the LASK module in the backbone to mitigate feature degradation of small objects via adaptive receptive fields and an anti-aliasing strategy; and the DSAB module in the neck to enhance localization precision through targeted cross-layer semantic injection.

- Extensive experiments on public UAV visible–infrared datasets are conducted to validate the effectiveness of the proposed modules and overall framework. The results demonstrate that, compared to current state-of-the-art methods, TAF-YOLO achieves superior performance in both accuracy and efficiency.

2. Related Work

2.1. Deep Learning Based Object Detection

2.2. Multimodal Fusion Object Detection

3. Methodology

3.1. Overview of Our Method

3.2. Two-Branch Adaptive Fusion Network

3.3. Large Adaptive Selective Kernel Module

3.4. Dual-Stream Attention Bridge

4. Experiment

4.1. Settings

- Hardware/Software Environment. The following experiments were performed on a computer with NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPU, 24 GB of memory, and Python code running on Ubuntu 24.04. With Visual Studio Code 1.103.2, CUDA 11.6, PyTorch 1.12, Python 3.8 and other commonly used deep learning and image processing libraries.

- Dataset. The VEDAI [48] dataset contains a total of 1246 pairs of RGB and IR images, covering nine object categories such as cars, trucks, vans, tractors, pick-ups, and other road vehicles. The images were captured by UAV and aircraft platforms over semi-urban and rural areas, featuring complex backgrounds such as roads, buildings, vegetation, and shadowed regions. Each image has a resolution of 1024 × 1024 pixels, and the objects of interest are generally small in scale, often occupying less than 1% of the total image area. These characteristics make the dataset particularly challenging for small-object detection, as the vehicles exhibit significant variations in size, shape, and orientation, and are often affected by background clutter, illumination variations, and low inter-class contrast.

- Implementation Details. We trained the network using the stochastic gradient descent (SGD) optimizer with the following hyperparameters. The initial learning rate is set to 0.01, the weight decay to 0.0005, and the momentum to 0.937. The model is trained for 300 iterations with a batch size of 8, and the input image size is set to 1024.

- Evaluation Metrics. In this work, we use Precision, Recall, and mean Average Precision (mAP), GFLOPs and Parameters as evaluation metrics to assess the performance of the detector as defined below:

4.2. Ablation Study

4.2.1. Comparisons of Different Fusion Stages and Approaches

4.2.2. Ablation Study of Each Component

4.3. Comparison of Experiment with Previous Methods

4.4. Generalization Experiment

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| CNNs | Convolutional Neural Networks |

| IR | Infrared |

| MF | Multimodal Fusion |

| VIF | Visible and Infrared Image Fusion |

| NMS | Non-Maximum Suppression |

| TAFNet | Two-branch Adaptive Fusion Network |

| LASK | Large Adaptive Selective Kernel |

| DSAB | Dual-Stream Attention Bridge |

| GSD | Ground Sampling Distance |

| A2C2f | Area-Attention Enhanced Cross-Feature module |

References

- Osco, L.P.; Marcato, J., Jr.; Marques Ramos, A.P.; de Castro Jorge, L.A.; Fatholahi, S.N.; de Andrade Silva, J.; Matsubara, E.T.; Pistori, H.; Gonçalves, W.N.; Li, J. A review on deep learning in UAV remote sensing. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2021, 102, 102456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aasen, H.; Honkavaara, E.; Lucieer, A.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J. Quantitative Remote Sensing at Ultra-High Resolution with UAV Spectroscopy: A Review of Sensor Technology, Measurement Procedures, and Data Correction Workflows. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, W.; Liu, J.; Fan, X.; Tjahjadi, T.; Ye, Q.; Fu, L. BASNet: Burned Area Segmentation Network for Real-Time Detection of Damage Maps in Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5627913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Jiang, T.; Zhu, Y.; Li, L.; Fan, F.; Jin, X. FEL-YoloV8: A New Algorithm for Accurate Monitoring Soybean Seedling Emergence Rates and Growth Uniformity. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5634217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Z.; Jiang, B.; Li, C.; Tang, J. UAV Video Vehicle Detection: Benchmark and Baseline. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5609814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Zhao, R.; Zhang, S.; Chen, L.; Shao, F.; Meng, X. IM-CMDet: An Intramodal Enhancement and Cross-Modal Fusion Network for Small Object Detection in UAV Aerial Visible-Infrared Imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5008316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Dollár, P.; Zitnick, C.L. Microsoft COCO: Common Objects in Context. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2014: 13th European Conference, Zurich, Switzerland, 6–12 September 2014; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 740–755. [Google Scholar]

- Ying, X.; Xiao, C.; An, W.; Li, R.; He, X.; Li, B.; Cao, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Hu, M.; et al. Visible-Thermal Tiny Object Detection: A Benchmark Dataset and Baselines. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2025, 47, 6088–6096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B.; Huang, Y.; Chen, J.; Huang, D. Adaptive Sparse Convolutional Networks with Global Context Enhancement for Faster Object Detection on Drone Images. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 13435–13444. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Fu, X.; Huang, Y.; Cao, C.; Shi, G.; Zha, Z.J. Generalized UAV Object Detection via Frequency Domain Disentanglement. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 1064–1073. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, Z.; Hu, X.; Zhong, P. Active Object Detection for UAV Remote Sensing via Behavior Cloning and Enhanced Q-Network with Shallow Features. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5628116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Z.; Wang, M.; Qiao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Z. Transformer-Based Object Detection in Low-Altitude Maritime UAV Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 4210413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Demiris, Y. Visible and Infrared Image Fusion Using Deep Learning. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 10535–10554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Chen, X.; Li, H.; Liu, T.; Chen, Z.; Gao, H.; Zhang, Y. Airborne Small Target Detection Method Based on Multimodal and Adaptive Feature Fusion. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5637215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Fan, X.; Jiang, J.; Liu, R.; Luo, Z. Learning a Deep Multi-Scale Feature Ensemble and an Edge-Attention Guidance for Image Fusion. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2022, 32, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, C.; Hu, Q.; Fu, H.; Zhu, P. Confidence-Aware Fusion Using Dempster-Shafer Theory for Multispectral Pedestrian Detection. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2023, 25, 3420–3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Vien, A.G.; Lee, C. Cross-Modal Transformers for Infrared and Visible Image Fusion. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2024, 34, 770–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Q.; Han, D.; Wang, Z. Cross-modality fusion transformer for multispectral object detection. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.00273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girshick, R.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Malik, J. Rich Feature Hierarchies for Accurate Object Detection and Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; pp. 580–587. [Google Scholar]

- Girshick, R. Fast R-CNN. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 1440–1448. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Vasconcelos, N. Cascade R-CNN: Delving into High Quality Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 6154–6162. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.-Y.; Berg, A.C. SSD: Single Shot MultiBox Detector. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal Loss for Dense Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2999–3007. [Google Scholar]

- Carion, N.; Massa, F.; Synnaeve, G.; Usunier, N.; Kirillov, A.; Zagoruyko, S. End-to-End Object Detection with Transformers. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2020, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; pp. 213–229. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.; Su, W.; Lu, L.; Li, B.; Wang, X.; Dai, J. Deformable DETR: Deformable transformers for end-to-end object detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.04159. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin Transformer: Hierarchical Vision Transformer using Shifted Windows. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 9992–10002. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Z.; Shen, C.; Chen, H.; He, T. FCOS: A Simple and Strong Anchor-Free Object Detector. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2022, 44, 1922–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, R.; S, M. YOLOv8: A Novel Object Detection Algorithm with Enhanced Performance and Robustness. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Advances in Data Engineering and Intelligent Computing Systems (ADICS), Chennai, India, 18–19 April 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Chen, K.; Ding, G.; Han, J.; Lin, Z.; Liu, L.; Wang, A. Yolov10: Real-time end-to-end object detection. In Proceedings of the 2024 Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 10–15 December 2024; Volume 37, pp. 107984–108011. [Google Scholar]

- Khanam, R.; Hussain, M. Yolov11: An overview of the key architectural enhancements. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.17725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Ye, Q.; Doermann, D. Yolov12: Attention-centric real-time object detectors. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.12524. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.; Lu, X.; Guo, C.; Guo, H. MV-YOLO: An Efficient Small Object Detection Framework Based on Mamba. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5632814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Cheng, X.; Xu, N.; Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Zhong, X. MFAE-YOLO: Multifeature Attention-Enhanced Network for Remote Sensing Images Object Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5631214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Bao, W.; Shang, H.; Yuan, M.; Cheng, Q. GCL-YOLO: A GhostConv-Based Lightweight YOLO Network for UAV Small Object Detection. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Xu, T.; Qin, H.; Li, J. IRSTD-YOLO: An Improved YOLO Framework for Infrared Small Target Detection. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2025, 22, 7001405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Luo, S.; Chen, M.; He, C.; Wang, T.; Wu, H. Infrared small target detection with super-resolution and YOLO. Opt. Laser Technol. 2024, 177, 111221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caesar, H.; Bankiti, V.; Lang, A.H.; Vora, S.; Liong, V.E.; Xu, Q.; Krishnan, A.; Pan, Y.; Baldan, G.; Beijbom, O. nuScenes: A Multimodal Dataset for Autonomous Driving. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 11618–11628. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, D.; Gao, L.; Yokoya, N.; Yao, J.; Chanussot, J.; Du, Q.; Zhang, B. More Diverse Means Better: Multimodal Deep Learning Meets Remote-Sensing Imagery Classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 59, 4340–4354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liao, X.; Yuan, J.; Yao, Y.; Li, Z. CDC-YOLOFusion: Leveraging Cross-Scale Dynamic Convolution Fusion for Visible-Infrared Object Detection. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2025, 10, 2080–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zuo, X.; Fan, H.; Yang, W. ICAFusion: Iterative cross-attention guided feature fusion for multispectral object detection. Pattern Recognit. 2024, 145, 109913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Liang, T.; Jin, Y.; Li, Y. MMI-Det: Exploring Multi-Modal Integration for Visible and Infrared Object Detection. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2024, 34, 11198–11213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.; Ma, Y.; Miao, D.; Song, P.; Gu, Z.; Tian, Z.; Wang, W. Decision Fusion Networks for Image Classification. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn, Syst. 2025, 36, 3890–3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Lei, J.; Xie, W.; Fang, Z.; Li, Y.; Du, Q. SuperYOLO: Super Resolution Assisted Object Detection in Multimodal Remote Sensing Imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5605415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Da, F. YOLO-FMEN: Pixel-Level Image Fusion-Based Nighttime Object Detection Network. In Proceedings of the 2025 44th Chinese Control Conference (CCC), Chongqing, China, 28–30 July 2025; pp. 9179–9186. [Google Scholar]

- Razakarivony, S.; Jurie, F. Vehicle detection in aerial imagery: A small target detection benchmark. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 2016, 34, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, L.; Jiang, H.; Weng, K.; Geng, Y.; Li, L.; Ke, Z.; Li, Q.; Cheng, M.; Nie, W. YOLOv6: A single-stage object detection framework for industrial applications. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.02976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, B.; Guo, X.; Zhu, W.; He, J.; Liu, X.; Yuan, J. DEYOLO: Dual-Feature-Enhancement YOLO for Cross-Modality Object Detection. In Pattern Recognition; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 236–252. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Cao, B.; Zhu, P.; Hu, Q. Drone-Based RGB-Infrared Cross-Modality Vehicle Detection Via Uncertainty-Aware Learning. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2022, 32, 6700–6713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | Pre | Rec | mAP50 | mAP50:95 | Params | GFLOPs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Fusion | YOLOv5n + Concat | 60.6 | 58.2 | 63.6 | 37.2 | 2.189 M | 6.0 |

| YOLOv5n + TAFNet | 62.9 | 56.0 | 63.4 | 39.9 | 2.307 M | 6.4 | |

| YOLOv6n + Concat | 57.0 | 56.3 | 56.9 | 35.9 | 4.160 M | 11.7 | |

| YOLOv6n + TAFNet | 59.1 | 61.0 | 60.6 | 39.1 | 4.235 M | 11.9 | |

| YOLOv8n + Concat | 65.4 | 52.3 | 60.9 | 38.5 | 2.691 M | 7.0 | |

| YOLOv8n + TAFNet | 66.0 | 54.8 | 61.9 | 40.6 | 3.007 M | 7.4 | |

| YOLOv10n + Concat | 68.6 | 50.4 | 60.2 | 38.3 | 2.710 M | 8.3 | |

| YOLOv10n + TAFNet | 71.6 | 52.3 | 62.0 | 39.3 | 2.698 M | 8.7 | |

| YOLOv11n + Concat | 62.0 | 59.6 | 61.6 | 40.6 | 2.412 M | 6.0 | |

| YOLOv11n + TAFNet | 62.6 | 60.4 | 62.8 | 41.2 | 2.728 M | 6.4 | |

| YOLOv12n + Concat | 54.6 | 59.3 | 60.2 | 37.3 | 2.509 M | 5.9 | |

| YOLOv12n + TAFNet | 57.5 | 62.6 | 62.4 | 41.2 | 2.810 M | 6.3 | |

| Ours + Concat | 64.3 | 59.5 | 64.1 | 42.2 | 4.231 M | 8.0 | |

| Ours + TAFNet | 68.8 | 63.7 | 67.2 | 44.3 | 4.518 M | 8.4 | |

| Intermediate Fusion | Fusion1 | 60.2 | 59.3 | 62.1 | 39.8 | 4.639 M | 39.0 |

| Fusion2 | 62.6 | 59.6 | 62.7 | 40.7 | 4.654 M | 13.0 | |

| Fusion3 | 61.7 | 61.4 | 63.1 | 41.2 | 4.827 M | 13.8 | |

| Fusion4 | 67.3 | 60.8 | 63.6 | 41.5 | 5.297 M | 14.6 | |

| Late Fusion | 60.2 | 54.3 | 59.8 | 37.2 | 11.709 M | 16.8 | |

| LASK | DSAB | Remove PANet | Params | GFLOPs | Pre | Rec | mAP50 | mAP50:95 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.810 M | 6.3 | 57.5 | 62.6 | 62.4 | 41.2 | |||

| 2 | √ | 3.024 M | 6.1 | 61.8 | 62.2 | 62.8 | 41.4 | ||

| 3 | √ | √ | 4.305 M | 8.6 | 62.7 | 62.5 | 66.9 | 43.6 | |

| 4 | √ | 1.831 M | 4.9 | 58.8 | 62.0 | 63.3 | 41.9 | ||

| 5 | √ | √ | 2.044 M | 4.7 | 62.1 | 60.8 | 63.7 | 42.4 | |

| 6 | √ | √ | √ | 4.518 M | 8.4 | 64.8 | 62.7 | 67.2 | 44.3 |

| Method | Car | Pickup | Camping | Truck | Others | Tractor | Boat | Van | mAP50 | mAP50:95 | Params | GFLOPs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv5n | RGB | 88.3 | 69.4 | 60.6 | 59.2 | 34.6 | 49.7 | 65.1 | 52.9 | 60.0 | 37.4 | 2.189 M | 5.9 |

| IR | 85.7 | 64.9 | 67.5 | 60.3 | 22.2 | 53.6 | 35.5 | 65.7 | 56.9 | 34.5 | 2.189 M | 5.9 | |

| Multi | 88.1 | 72.0 | 65.2 | 65.4 | 47.2 | 53.8 | 63.3 | 51.8 | 63.4 | 39.9 | 2.307 M | 6.4 | |

| YOLOv6n | RGB | 87.1 | 72.0 | 60.1 | 59.2 | 44.2 | 55.2 | 35.1 | 55.3 | 58.5 | 36.1 | 4.160 M | 11.6 |

| IR | 86.7 | 65.6 | 52.8 | 65.6 | 22.2 | 55.1 | 14.5 | 52.2 | 51.8 | 31.7 | 4.160 M | 11.6 | |

| Multi | 84.5 | 68.7 | 60.9 | 59.4 | 53.7 | 60.0 | 27.8 | 67.9 | 60.6 | 39.1 | 4.335 M | 11.9 | |

| YOLOv8n | RGB | 87.8 | 76.1 | 55.0 | 54.7 | 38.6 | 62.1 | 51.5 | 45.3 | 58.9 | 35.5 | 2.691 M | 6.9 |

| IR | 85.2 | 66.6 | 63.6 | 63.3 | 30.5 | 41.4 | 35.7 | 52.5 | 54.8 | 33.4 | 2.691 M | 6.9 | |

| Multi | 83.1 | 73.6 | 61.8 | 64.3 | 41.6 | 68.1 | 44.9 | 39.0 | 61.9 | 40.6 | 3.007 M | 7.4 | |

| YOLOv10n | RGB | 84.9 | 69.9 | 61.3 | 59.9 | 17.6 | 49.4 | 48.9 | 50.5 | 55.3 | 33.9 | 2.710 M | 8.2 |

| IR | 81.5 | 68.5 | 55.1 | 53.8 | 23.8 | 36.9 | 30.9 | 51.9 | 50.3 | 31.2 | 2.710 M | 8.2 | |

| Multi | 81.2 | 66.9 | 61.6 | 63.8 | 37.9 | 48.5 | 57.6 | 78.4 | 62.0 | 39.3 | 2.842 M | 8.7 | |

| YOLOv11n | RGB | 88.8 | 71.7 | 75.9 | 57.3 | 31.4 | 59.4 | 40.7 | 49.3 | 59.3 | 35.4 | 2.412 M | 5.9 |

| IR | 84.7 | 69.1 | 64.9 | 73.6 | 30.4 | 37.3 | 39.8 | 47.7 | 55.9 | 33.9 | 2.412 M | 5.9 | |

| Multi | 84.9 | 74.1 | 67.3 | 72.0 | 44.8 | 72.1 | 62.2 | 48.8 | 62.8 | 41.2 | 2.728 M | 6.6 | |

| YOLOv12n | RGB | 87.0 | 71.6 | 63.5 | 61.1 | 42.8 | 56.9 | 46.7 | 42.1 | 59.0 | 35.2 | 2.509 M | 5.8 |

| IR | 80.8 | 64.7 | 57.0 | 66.0 | 22.4 | 34.6 | 29.1 | 37.1 | 49.0 | 29.9 | 2.509 M | 5.8 | |

| Multi | 83.3 | 73.4 | 75.7 | 58.0 | 45.6 | 60.4 | 54.2 | 59.9 | 62.4 | 41.2 | 2.810 M | 6.3 | |

| CFT | Multi | 85.6 | 73.2 | 65.2 | 65.6 | 44.3 | 64.2 | 54.2 | 60.8 | 64.5 | 42.1 | 47.06 M | 117.2 |

| DEYOLOn | Multi | 85.2 | 70.5 | 70.0 | 68.3 | 50.3 | 67.0 | 60.2 | 61.5 | 65.7 | 43.2 | 6.09 M | - |

| TAF-YOLO (Ours) | RGB | 88.5 | 70.4 | 63.4 | 62.1 | 43.2 | 57.2 | 52.2 | 45.6 | 62.2 | 40.4 | 4.231 M | 7.9 |

| IR | 84.5 | 68.7 | 60.9 | 59.4 | 30.2 | 39.6 | 27.8 | 39.6 | 60.3 | 38.3 | 4.231 M | 7.9 | |

| Multi | 87.0 | 72.3 | 75.7 | 71.3 | 47.6 | 65.4 | 67.9 | 62.9 | 67.2 | 44.3 | 4.518 M | 8.4 | |

| Method | Cars | Trucks | Buses | Vans | Freight cars | mAP50 | mAP50:95 | Params | GFLOPs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv5n | Multi | 91.8 | 46.3 | 84.3 | 45.3 | 44.6 | 62.1 | 41.4 | 2.307 M | 6.4 |

| YOLOv8n | Multi | 92.0 | 50.4 | 84.3 | 46.6 | 45.2 | 62.9 | 42.1 | 3.007 M | 7.4 |

| YOLOv10n | Multi | 91.3 | 44.8 | 83.6 | 40.2 | 44.4 | 60.3 | 41.1 | 2.842 M | 8.9 |

| YOLOv11n | Multi | 91.3 | 36.4 | 80.6 | 33.7 | 41.8 | 57.4 | 38.3 | 2.728 M | 6.6 |

| YOLOv12n | Multi | 91.4 | 45.1 | 84.5 | 42.3 | 45.0 | 61.8 | 40.4 | 2.810 M | 6.3 |

| CFT | Multi | 92.4 | 55.5 | 88.6 | 44.6 | 46.3 | 65.4 | 45.7 | 47.06 M | 117.2 |

| DEYOLOn | Multi | 91.0 | 51.8 | 85.2 | 44.1 | 46.9 | 64.4 | 43.6 | 6.09 M | - |

| TAF-YOLO | Multi | 91.7 | 58.6 | 89.2 | 46.9 | 44.3 | 65.8 | 46.7 | 4.518 M | 8.4 |

| Random Seed | Pre | Rec | mAP50 | mAP50:95 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 68.8 | 63.7 | 67.2 | 44.3 |

| 2 | 68.0 | 63.9 | 67.0 | 43.9 |

| 3 | 68.7 | 64.1 | 67.3 | 44.3 |

| 4 | 68.7 | 64.2 | 67.3 | 44.4 |

| 5 | 69.0 | 64.7 | 67.9 | 44.7 |

| Mean Value | 68.64 | 64.12 | 67.34 | 44.32 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhuo, Z.; Lu, R.; Yao, Y.; Wang, S.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, J.; Yang, X. TAF-YOLO: A Small-Object Detection Network for UAV Aerial Imagery via Visible and Infrared Adaptive Fusion. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3936. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243936

Zhuo Z, Lu R, Yao Y, Wang S, Zheng Z, Zhang J, Yang X. TAF-YOLO: A Small-Object Detection Network for UAV Aerial Imagery via Visible and Infrared Adaptive Fusion. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):3936. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243936

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhuo, Zhanhong, Ruitao Lu, Yongxiang Yao, Siyu Wang, Zhi Zheng, Jing Zhang, and Xiaogang Yang. 2025. "TAF-YOLO: A Small-Object Detection Network for UAV Aerial Imagery via Visible and Infrared Adaptive Fusion" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 3936. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243936

APA StyleZhuo, Z., Lu, R., Yao, Y., Wang, S., Zheng, Z., Zhang, J., & Yang, X. (2025). TAF-YOLO: A Small-Object Detection Network for UAV Aerial Imagery via Visible and Infrared Adaptive Fusion. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 3936. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243936