Characteristics of Planetary Boundary Layer Height (PBLH) over Shenzhen, China: Retrieval Methods and Air Pollution Conditions

Highlights

- What are the main findings?

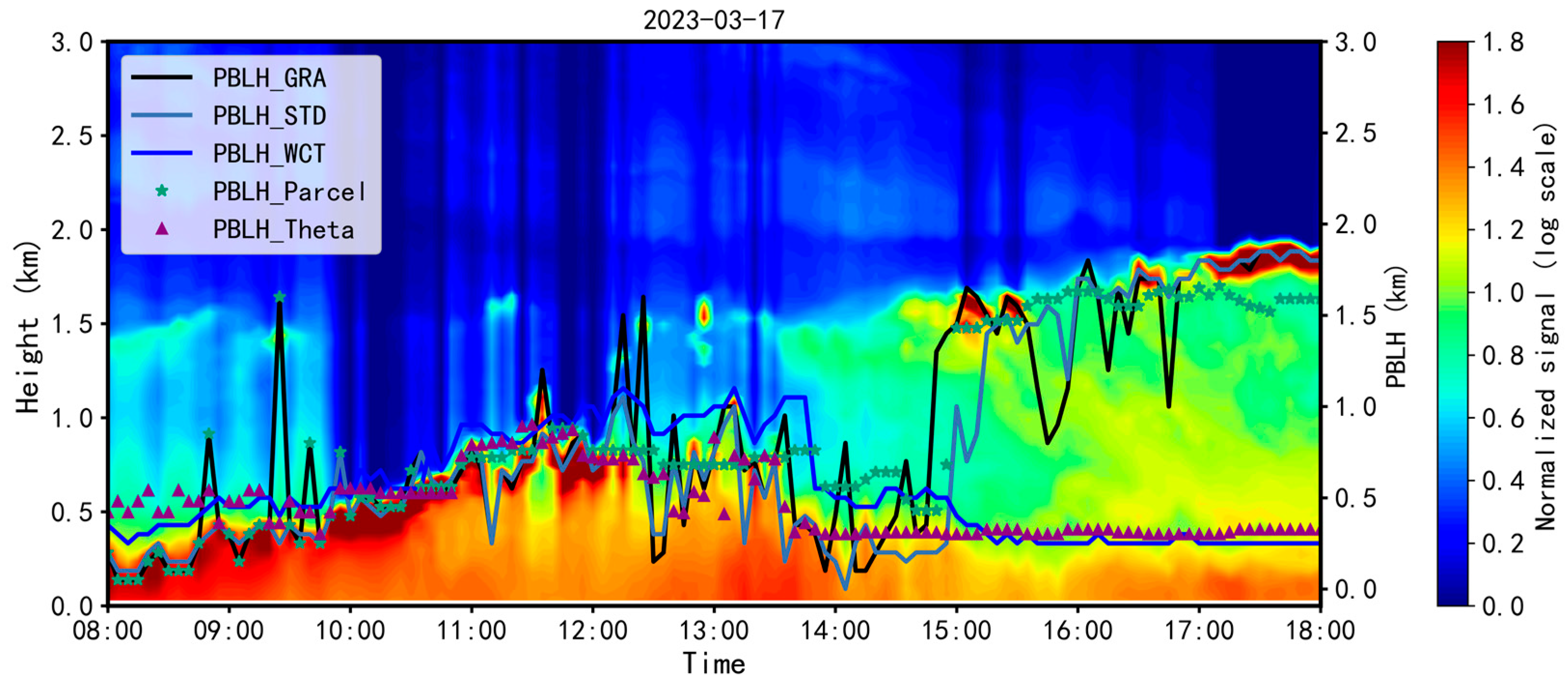

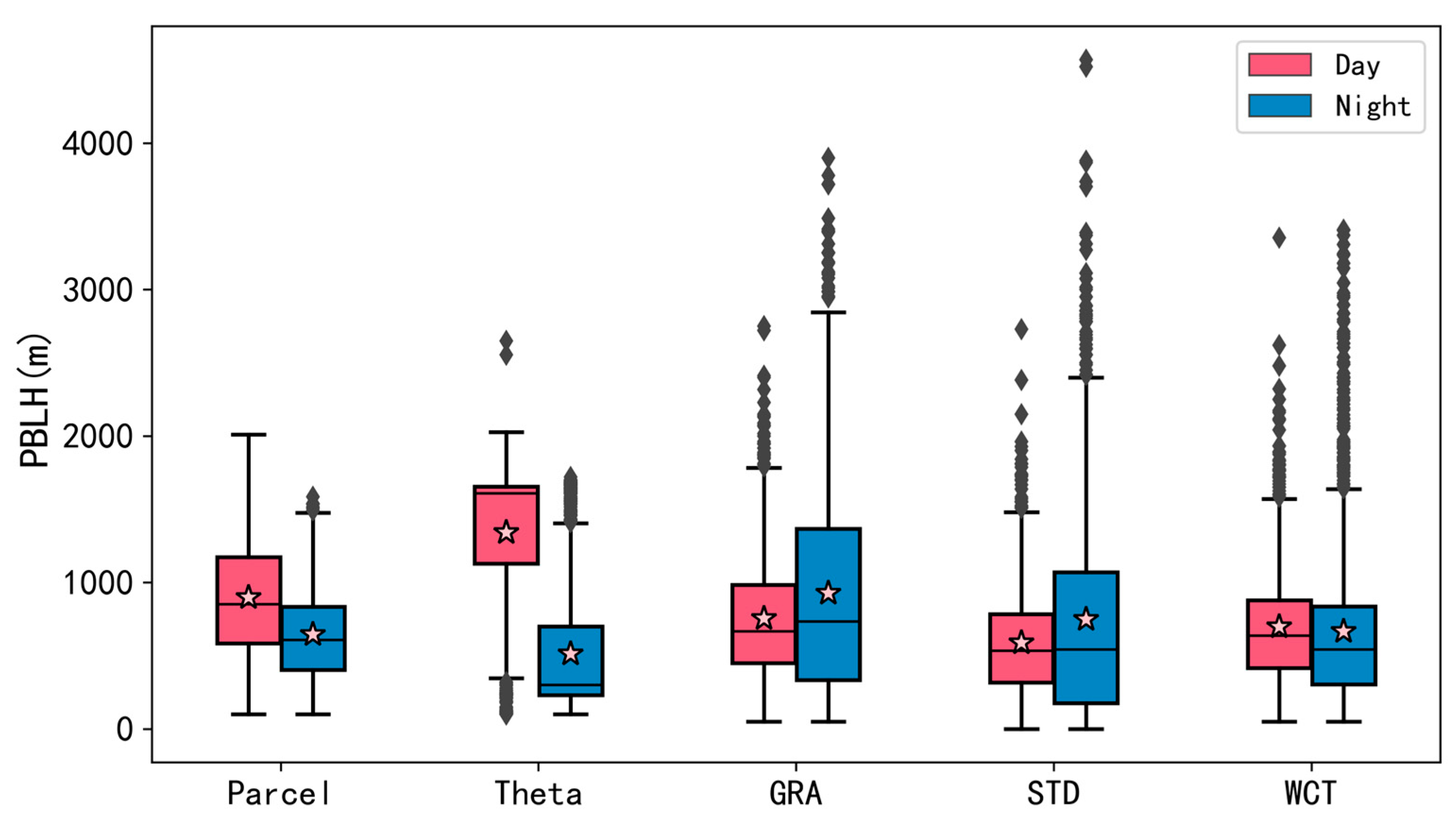

- The gradient method and standard deviation method based on Micro-Pulse Lidar and the parcel method based on Microwave Radiometers are more sensitive to abrupt changes in boundary layer height.

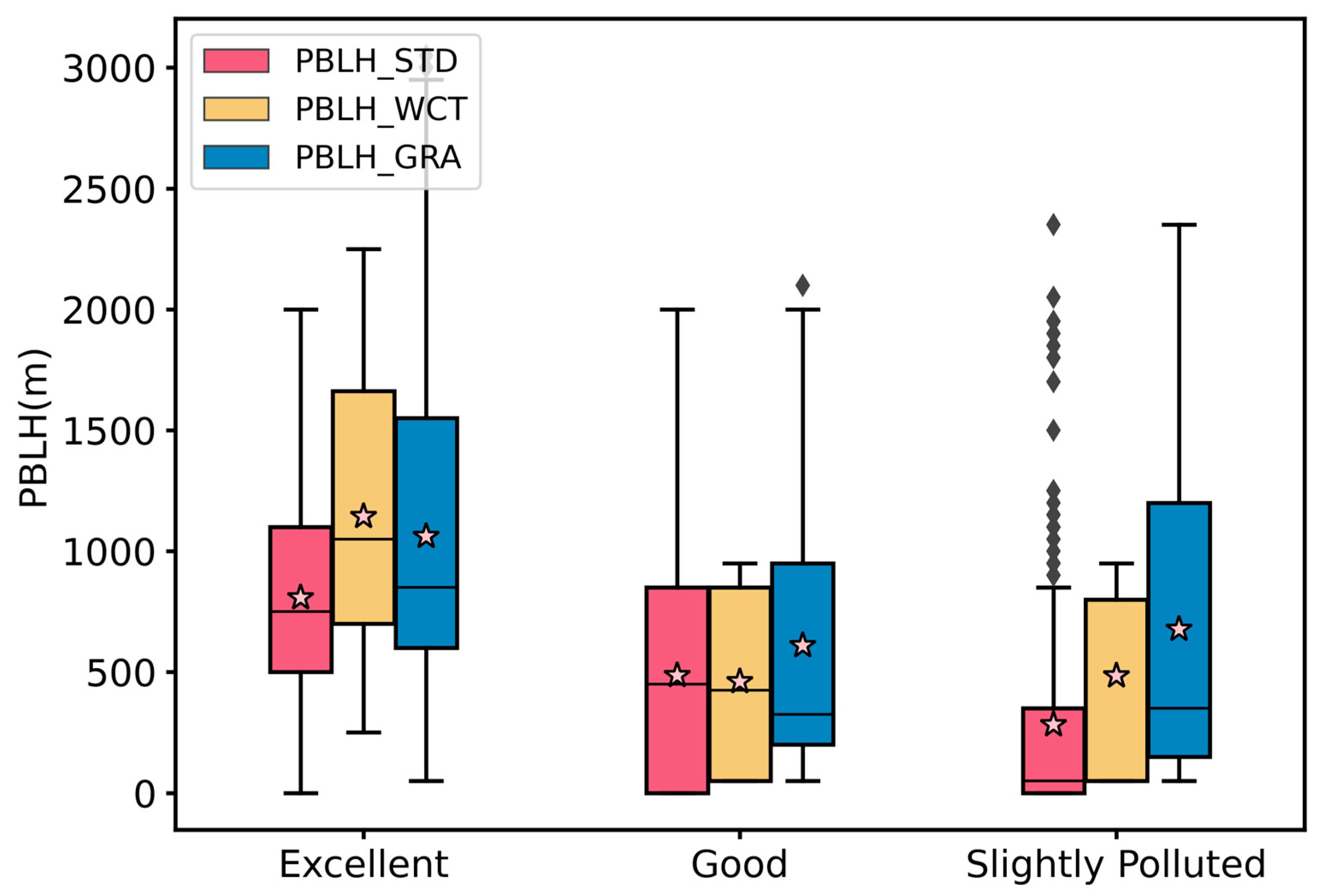

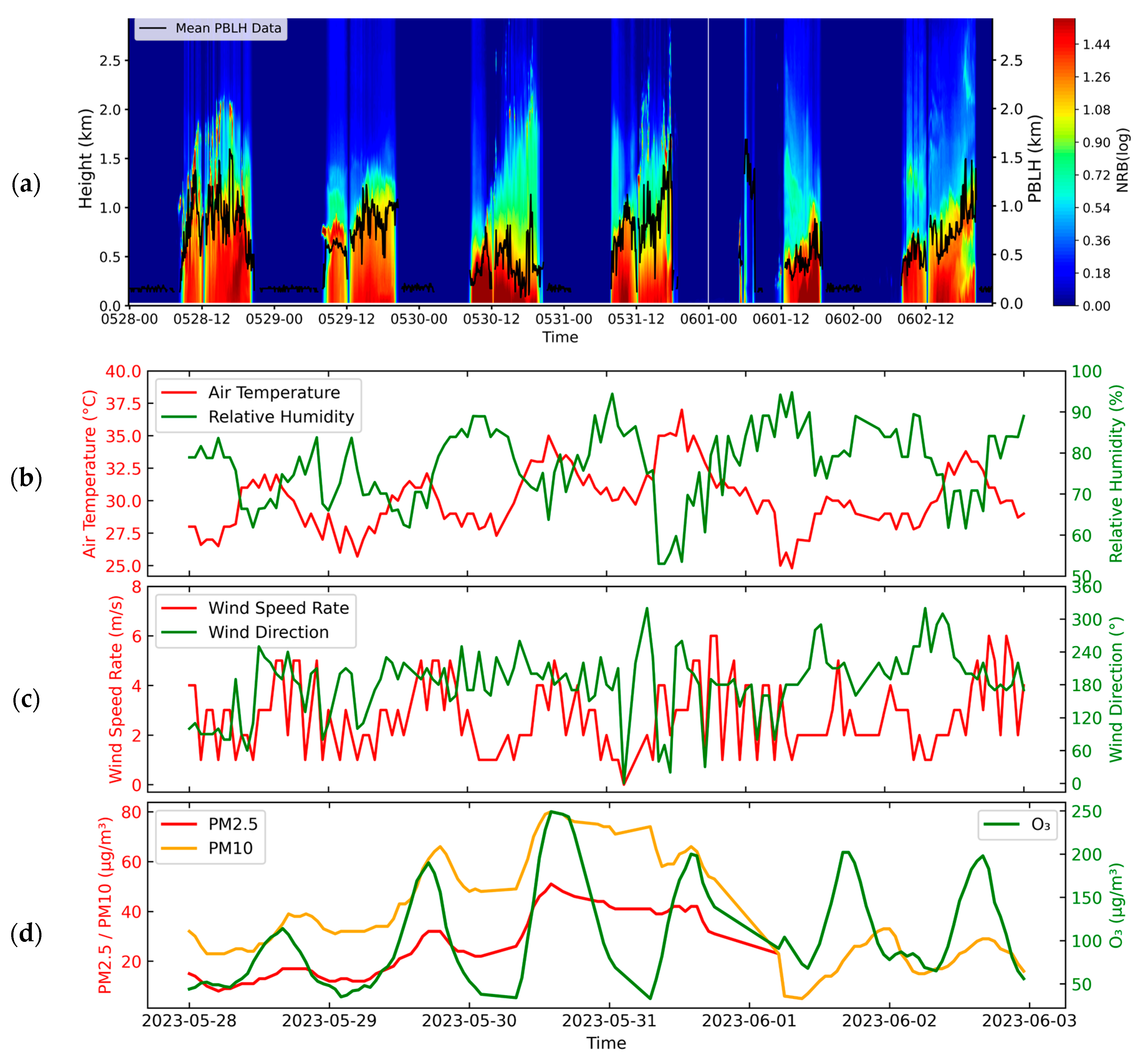

- During the observation period, Shenzhen’s PBLH characteristics exhibited significant diurnal variation and high sensitivity to pollution, the daytime mean PBLH ranged from approximately 512 to 1345 m, while nighttime values generally decreased to around 500 to 650 m. And under high aerosol loading conditions, PBLH was significantly suppressed to approximately 500 m, indicating that pollution limits atmospheric mixing by inhibiting boundary layer development.

- What are the implications of the main findings?

- By comparing different retrieval methods, we can identify the strengths and weaknesses of each method, providing guidance on selecting appropriate algorithm for similar urban environments.

- The study of boundary layer characteristics in Shenzhen holds significant scientific value for future research on factors influencing boundary layer height in megacities.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Aera

2.2. Instrumentations

2.2.1. MPL

2.2.2. MWR

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Retrieving Method PBLH from MPL

2.3.2. Retrieving Method PBLH from MWR

2.3.3. Comparison of PBLH Calculation Methods

2.4. Other Datasets

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of PBLH Retrieved by Different Instruments and Methods

3.2. PBLH Variation Properties Under Different Particulate Pollution Condition

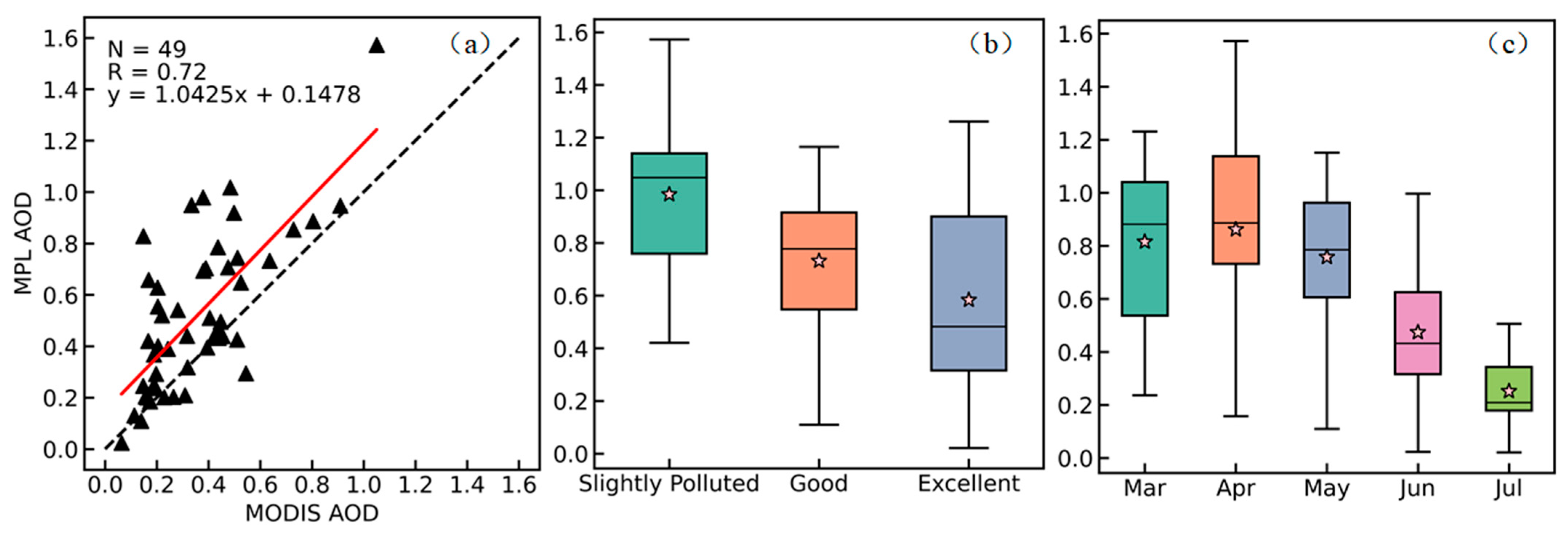

3.3. Correlation Between PBLH and AOD

3.4. Case Study

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Garratt, J.R. Review: The Atmospheric Boundary Layer. Earth-Sci. Rev. 1994, 37, 89–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molod, A.; Salmun, H.; Dempsey, M. Estimating Planetary Boundary Layer Heights from NOAA Profiler Network Wind Profiler Data. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2015, 32, 1545–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibert, P.; Beyrich, F.; Gryning, S.-E.; Joffre, S.; Rasmussen, A.; Tercier, P. Review and Intercomparison of Operational Methods for the Determination of the Mixing Height. Atmos. Environ. 2000, 34, 1001–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stull, R.B. An Introduction to Boundary Layer Meteorology; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; ISBN 978-94-009-3027-8. [Google Scholar]

- Soong, W.-K.; Hung, C.-H. Intrinsic Mechanisms for High-Concentrated PMs in Southern Taiwan: Combined Effects by PBLH, LCFs and Large-Scale Subsidence. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2025, 25, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, T.; Li, Z.; Li, C.; Li, J.; Han, W.; Shen, C.; Tan, W.; Wei, J.; Guo, J. The Significant Impact of Aerosol Vertical Structure on Lower Atmosphere Stability and Its Critical Role in Aerosol–Planetary Boundary Layer (PBL) Interactions. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2020, 20, 3713–3724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, O.; Hohman, T.; Buren, T.V.; Bou-Zeid, E.; Smits, A.J. The effect of stable thermal stratification on turbulent boundary layer statistics. J. Fluid Mech. 2017, 812, 1039–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Ye, J.; Xin, J.; Zhang, W.; Vilà-Guerau de Arellano, J.; Wang, S.; Zhao, D.; Dai, L.; Ma, Y.; Wu, X.; et al. The Stove, Dome, and Umbrella Effects of Atmospheric Aerosol on the Development of the Planetary Boundary Layer in Hazy Regions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2020, 47, e2020GL087373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, A.J.; Fu, C.B.; Yang, X.Q.; Sun, J.N.; Petäjä, T.; Kerminen, V.-M.; Wang, T.; Xie, Y.; Herrmann, E.; Zheng, L.F.; et al. Intense Atmospheric Pollution Modifies Weather: A Case of Mixed Biomass Burning with Fossil Fuel Combustion Pollution in Eastern China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2013, 13, 10545–10554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Guo, J.; Ding, A.; Liao, H.; Liu, J.; Sun, Y.; Wang, T.; Xue, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, B. Aerosol and Boundary-Layer Interactions and Impact on Air Quality. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2017, 4, 810–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; He, J.; Ren, Y.; Wang, H. Aerosol-PBL Relationship under Diverse Meteorological Conditions: Insights from Satellite/Radiosonde Measurements in North China. Atmos. Res. 2025, 321, 108125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, J.; Xu, S.; Li, J.; He, J.; Huang, J. Diurnal Variation in the Near-Global Planetary Boundary Layer Height from Satellite-Based CATS Lidar: Retrieval, Evaluation, and Influencing Factors. Remote Sens. Environ. 2023, 299, 113847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-H.; Yeo, H.; Park, S.; Park, D.-H.; Omar, A.; Nishizawa, T.; Shimizu, A.; Kim, S.-W. Assessing CALIOP-Derived Planetary Boundary Layer Height Using Ground-Based Lidar. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmun, H.; Josephs, H.; Molod, A. GRWP-PBLH: Global Radar Wind Profiler Planetary Boundary Layer Height Data. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2023, 104, E1044–E1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, L.; Wilczak, J.M. Convective Boundary Layer Depth: Improved Measurement by Doppler Radar Wind Profiler Using Fuzzy Logic Methods. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2002, 19, 1745–1758. [Google Scholar]

- Schween, J.H.; Hirsikko, A.; Löhnert, U.; Crewell, S. Mixing-Layer Height Retrieval with Ceilometer and Doppler Lidar: From Case Studies to Long-Term Assessment. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2014, 7, 3685–3704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotthaus, S.; Grimmond, C.S.B. Atmospheric Boundary-Layer Characteristics from Ceilometer Measurements. Part 1: A New Method to Track Mixed Layer Height and Classify Clouds. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2018, 144, 1525–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Arruda Moreira, G.; Guerrero-Rascado, J.L.; Bravo-Aranda, J.A.; Benavent-Oltra, J.A.; Ortiz-Amezcua, P.; Róman, R.; Bedoya-Velásquez, A.E.; Landulfo, E.; Alados-Arboledas, L. Study of the Planetary Boundary Layer by Microwave Radiometer, Elastic Lidar and Doppler Lidar Estimations in Southern Iberian Peninsula. Atmos. Res. 2018, 213, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Song, M.; Mamtimin, A.; Xue, Y.; Peng, J.; Sayit, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Gao, J.; Aihaiti, A.; et al. An Evaluation of the Applicability of a Microwave Radiometer Under Different Weather Conditions at the Southern Edge of the Taklimakan Desert. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menut, L.; Flamant, C.; Pelon, J.; Flamant, P.H. Urban Boundary-Layer Height Determination from Lidar Measurements over the Paris Area. Appl. Opt. 1999, 38, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, D.J.; Ao, C.O.; Li, K. Estimating Climatological Planetary Boundary Layer Heights from Radiosonde Observations: Comparison of Methods and Uncertainty Analysis. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2010, 115, D16113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, D.J.; Zhang, Y.; Beljaars, A.; Golaz, J.-C.; Jacobson, A.R.; Medeiros, B. Climatology of the Planetary Boundary Layer over the Continental United States and Europe. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2012, 117, D17106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compton, J.C.; Delgado, R.; Berkoff, T.A.; Hoff, R.M. Determination of Planetary Boundary Layer Height on Short Spatial and Temporal Scales: A Demonstration of the Covariance Wavelet Transform in Ground-Based Wind Profiler and Lidar Measurements. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2013, 30, 1566–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, I.M. Finding Boundary Layer Top: Application of a Wavelet Covariance Transform to Lidar Backscatter Profiles. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2003, 20, 1092–1105. [Google Scholar]

- Steyn, D.G.; Baldi, M.; Hoff, R.M. The Detection of Mixed Layer Depth and Entrainment Zone Thickness from Lidar Backscatter Profiles. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 1999, 16, 953–959. [Google Scholar]

- Holzworth, G.C. Estimates of mean maximum mixing depths in the contiguous united states. Mon. Weather. Rev. 1964, 92, 235–242. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, X.; Tang, L.; Han, G.; Chen, W. Temperature Gradient Method for Deriving Planetary Boundary Layer Height from AIRS Profile Data over the Heihe River Basin of China. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, D.; Córdoba-Jabonero, C.; Adame, J.A.; De La Morena, B.; Gil-Ojeda, M. Estimation of the Atmospheric Boundary Layer Height during Different Atmospheric Conditions: A Comparison on Reliability of Several Methods Applied to Lidar Measurements. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2017, 38, 3203–3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, T.; Wang, N.; Shen, X.; Xiao, D.; Xiang, Z.; Liu, D. Determination of Planetary Boundary Layer Height with Lidar Signals Using Maximum Limited Height Initialization and Range Restriction (MLHI-RR). Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, B.; Ma, X.; Jin, S.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Gong, W. Evaluation of Retrieval Methods for Planetary Boundary Layer Height Based on Radiosonde Data. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2021, 14, 5977–5986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopoulos, J.A.; Saide, P.E.; Ferrare, R.; Collister, B.; Barton-Grimley, R.A.; Scarino, A.J.; Collins, J.; Hair, J.W.; Nehrir, A. Improving Planetary Boundary Layer Height Estimation From Airborne Lidar Instruments. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2025, 130, e2024JD042538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, N.; Wang, R. School of Hydrology and Water Resources, Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology, Nanjing 210044, China; State Oceanic Administration Key Laboratory for Polar Science, Polar Research Institute of China, Shanghai 200136, China Diurnal Variability of the Planetary Boundary Layer Height Estimated from Radiosonde Data. Earth Planet. Phys. 2020, 4, 479–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, B.; Fang, X.; Zhu, W.; Fan, Q.; Liao, Z.; Liu, J.; Zhang, A.; Fan, S. Combined Effect of Boundary Layer Recirculation Factor and Stable Energy on Local Air Quality in the Pearl River Delta over Southern China. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2018, 68, 685–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Wang, B.; Tesche, M.; Engelmann, R.; Althausen, A.; Liu, J.; Zhu, W.; Fan, Q.; Li, M.; Ta, N.; et al. Meteorological Conditions and Structures of Atmospheric Boundary Layer in October 2004 over Pearl River Delta Area. Atmos. Environ. 2008, 42, 6174–6186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Gao, C.Y.; Hong, J.; Gao, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Fan, S.; Zhu, B. Surface Meteorological Conditions and Boundary Layer Height Variations During an Air Pollution Episode in Nanjing, China. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2019, 124, 3350–3364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Hu, F.; Xiao, Z.; Fan, G.; Zhang, Z. Comparison of Four Different Types of Planetary Boundary Layer Heights during a Haze Episode in Beijing. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 711, 134928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, J.T.; Stauffer, R.M.; Thompson, A.M.; Tzortziou, M.A.; Loughner, C.P.; Jordan, C.E.; Santanello, J.A. Surf, Turf, and Above the Earth: Unmet Needs for Coastal Air Quality Science in the Planetary Boundary Layer (PBL). Earths Future 2023, 11, e2023EF003535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Tian, Y.; Wei, N.; Ho, S.; Li, J. Rising Planetary Boundary Layer Height over the Sahara Desert and Arabian Peninsula in a Warming Climate. J. Clim. 2021, 34, 4043–4068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakoudi, K.; Giannakaki, E.; Dandou, A.; Tombrou, M.; Komppula, M. Planetary Boundary Layer Height by Means of Lidar and Numerical Simulations over New Delhi, India. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2019, 12, 2595–2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Wang, J.; Sheng, L.; Jiang, Q. A Comparative Study on Four Methods of Boundary Layer Height Calculation in Autumn and Winter under Different PM2.5 Pollution Levels in Xi’an, China. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, T.; Li, Z.; Kahn, R. Relationships between the Planetary Boundary Layer Height and Surface Pollutants Derived from Lidar Observations over China: Regional Pattern and Influencing Factors. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2018, 18, 15921–15935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Sun, C.; Liu, C.; Jiang, L.; Xie, Y.; Yan, S.; Jiang, Z.; Qi, Q.; Zhang, A. The Influence of Air Pollutants and Meteorological Conditions on the Hospitalization for Respiratory Diseases in Shenzhen City, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Lu, C.; Chan, P.-W.; Zhang, X.; Yang, H.-L.; Lan, Z.-J.; Zhang, W.-H.; Liu, Y.-W.; Pan, L.; Zhang, L. Tower Observed Vertical Distribution of PM2.5, O3 and NOx in the Pearl River Delta. Atmos. Environ. 2020, 220, 117083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.R.; Hlavka, D.L.; Welton, E.J.; Flynn, C.J.; Turner, D.D.; Spinhirne, J.D.; Scott, V.S.; Hwang, I.H. Full-Time, Eye-Safe Cloud and Aerosol Lidar Observation at Atmospheric Radiation Measurement Program Sites: Instruments and Data Processing. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2002, 19, 431–442. [Google Scholar]

- He, Q.S.; Mao, J.T.; Chen, J.Y.; Hu, Y.Y. Observational and Modeling Studies of Urban Atmospheric Boundary-Layer Height and Its Evolution Mechanisms. Atmos. Environ. 2006, 40, 1064–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Xu, J.; Tie, X.; Mao, X.; Gao, W.; Chang, L. Long-Term Measurements of Planetary Boundary Layer Height and Interactions with PM2.5 in Shanghai, China. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2019, 10, 989–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, W.P.; Eloranta, E.W. Lidar Measurements of Wind in the Planetary Boundary Layer: The Method, Accuracy and Results from Joint Measurements with Radiosonde and Kytoon. J. Clim. Appl. Meteorol. 1986, 25, 990–1001. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, K.J.; Gamage, N.; Hagelberg, C.R.; Kiemle, C.; Lenschow, D.H.; Sullivan, P.P. An Objective Method for Deriving Atmospheric Structure from Airborne Lidar Observations. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2000, 17, 1455–1468. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Liang, X.-Z. Observed Diurnal Cycle Climatology of Planetary Boundary Layer Height. J. Clim. 2010, 23, 5790–5809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Gong, W.; Liu, B.; Ma, Y.; Jin, S.; Wang, W.; Fan, R.; Jiang, S.; Wang, Y.; Tong, Z. Sea Breeze-Driven Variations in Planetary Boundary Layer Height over Barrow: Insights from Meteorological and Lidar Observations. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Zhao, W.; Chen, Y. Lidar and Microwave Radiometer Observations of Planetary Boundary Layer Structure under Light Wind Weather. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 2012, 6, 063513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, T.; Li, Z.; Kahn, R. A New Method to Retrieve the Diurnal Variability of Planetary Boundary Layer T Height from Lidar under Different Thermodynamic Stability Conditions. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 237, 111519. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Xin, J.; Zhao, D.; Jia, D.; Tang, G.; Quan, J.; Wang, M.; Dai, L. Analysis of Differences between Thermodynamic and Material Boundary Layer Structure: Comparison of Detection by Ceilometer and Microwave Radiometer. Atmos. Res. 2021, 248, 105179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Han, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Dong, L.; Zhou, Q.; Xiao, P. Interaction Influence Characteristics of Air Quality and Aerosol Properties between Beijing-Tianjing-Hebei (BTH) and Yangtze River Delta (YRD), China. Urban Clim. 2025, 61, 102395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Hao, T.; Yang, X.; Yang, Y.; Luo, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Lu, M. Land-Sea Difference of the Planetary Boundary Layer Structure and Its Influence on PM2.5—Observation and Numerical Simulation. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 858, 159881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-H.; Park, M.-S.; Choi, Y. Planetary Boundary-Layer Structure at an Inland Urban Site under Sea Breeze Penetration. Asia-Pac. J. Atmos. Sci. 2021, 57, 701–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HJ 633-2012; Technical Regulation on Ambient Air Quality Index (on Trial). Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2012.

- Zheng, B.; Wu, D.; Li, F.; Deng, T. Changes in the Aerosol Optical Properties in Guangzhou under the South China Sea Summer Monsoon. J. Trop. Meteorol. 2013, 29, 207–214. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ye, L.; Huang, M.; Zhong, B.; Wang, X.; Tu, Q.; Sun, H.; Wang, C.; Wu, L.; Chang, M. Wet and Dry Deposition Fluxes of Heavy Metals in Pearl River Delta Region (China): Characteristics, Ecological Risk Assessment, and Source Apportionment. J. Environ. Sci. China 2018, 70, 106–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Ding, X.; He, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, D.; Zhang, T.; Yang, K.; Wang, J.; Cheng, Q.; Jiang, H.; et al. Long-Term Trends in PM2.5 Chemical Composition and Its Impact on Aerosol Properties: Field Observations from 2007 to 2020 in Pearl River Delta, South China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2025, 25, 13729–13745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| GRA | Applicable to lidar data, especially suitable for use under clear-sky conditions | In the case of rapid gradient changes, it may lead to abrupt or discontinuous results |

| STD | Wide applicability | It may yield inconsistent results under complex boundary layer or unstable conditions |

| WCT | Effectively identifies PBLH based on temperature gradients, suitable for both stable and unstable atmospheric conditions. | It may produce errors when identifying inversion layers. |

| Parcel | Directly reflects the potential temperature structure of the boundary layer | Sensitive to surface temperature errors, and less accurate under strong convection or non-adiabatic conditions |

| Theta | Effectively reflects changes in potential temperature gradients, especially suitable for cases with clear temperature profiles | It may overestimate under strong vertical temperature gradients. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, Y.; Han, Y.; Hu, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, Y.; Dong, L.; Xiao, P. Characteristics of Planetary Boundary Layer Height (PBLH) over Shenzhen, China: Retrieval Methods and Air Pollution Conditions. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3937. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243937

Zhou Y, Han Y, Hu Z, Zhou Q, Liu Y, Dong L, Xiao P. Characteristics of Planetary Boundary Layer Height (PBLH) over Shenzhen, China: Retrieval Methods and Air Pollution Conditions. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):3937. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243937

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Yaqi, Yong Han, Zhiyuan Hu, Qicheng Zhou, Yan Liu, Li Dong, and Peng Xiao. 2025. "Characteristics of Planetary Boundary Layer Height (PBLH) over Shenzhen, China: Retrieval Methods and Air Pollution Conditions" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 3937. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243937

APA StyleZhou, Y., Han, Y., Hu, Z., Zhou, Q., Liu, Y., Dong, L., & Xiao, P. (2025). Characteristics of Planetary Boundary Layer Height (PBLH) over Shenzhen, China: Retrieval Methods and Air Pollution Conditions. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 3937. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243937