In this section, we will introduce the experimental setting, optimization results, ablation study, comparative experiment, and generalization ability of the proposed method.

4.1. Experimental Setting

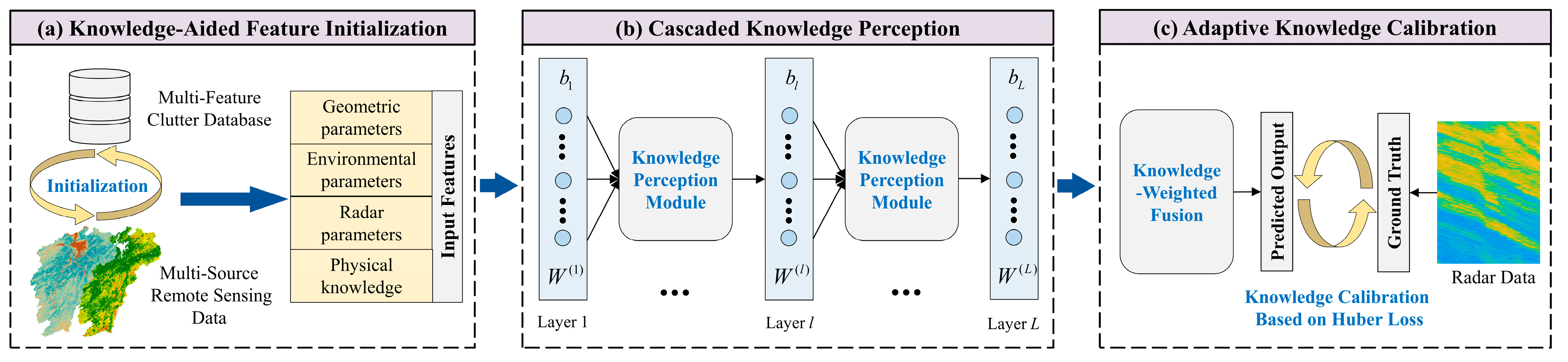

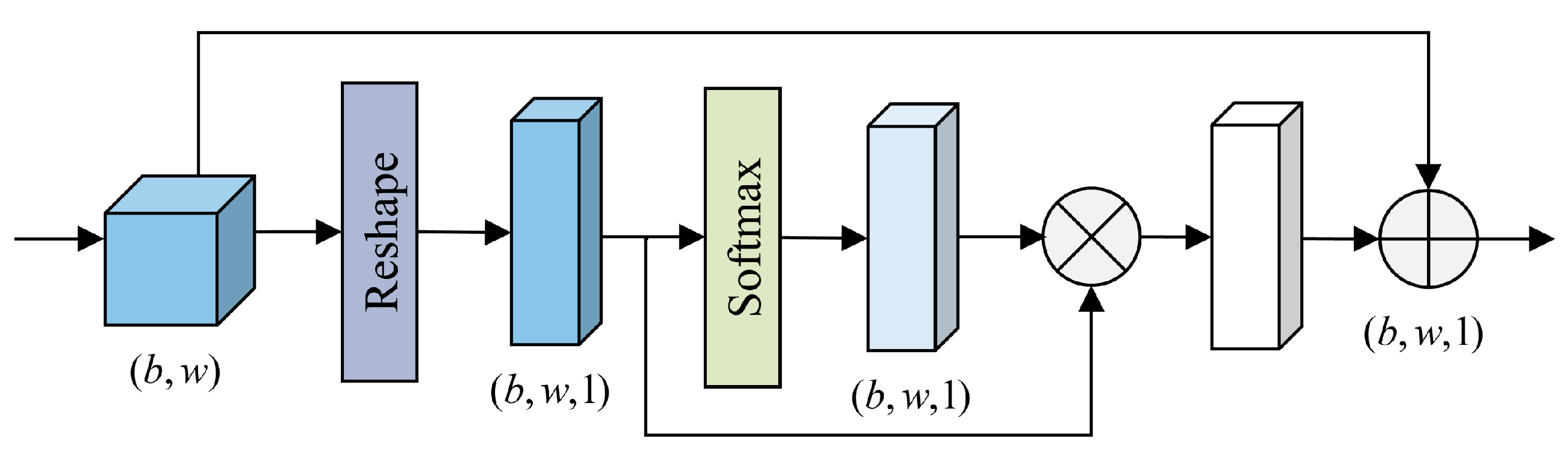

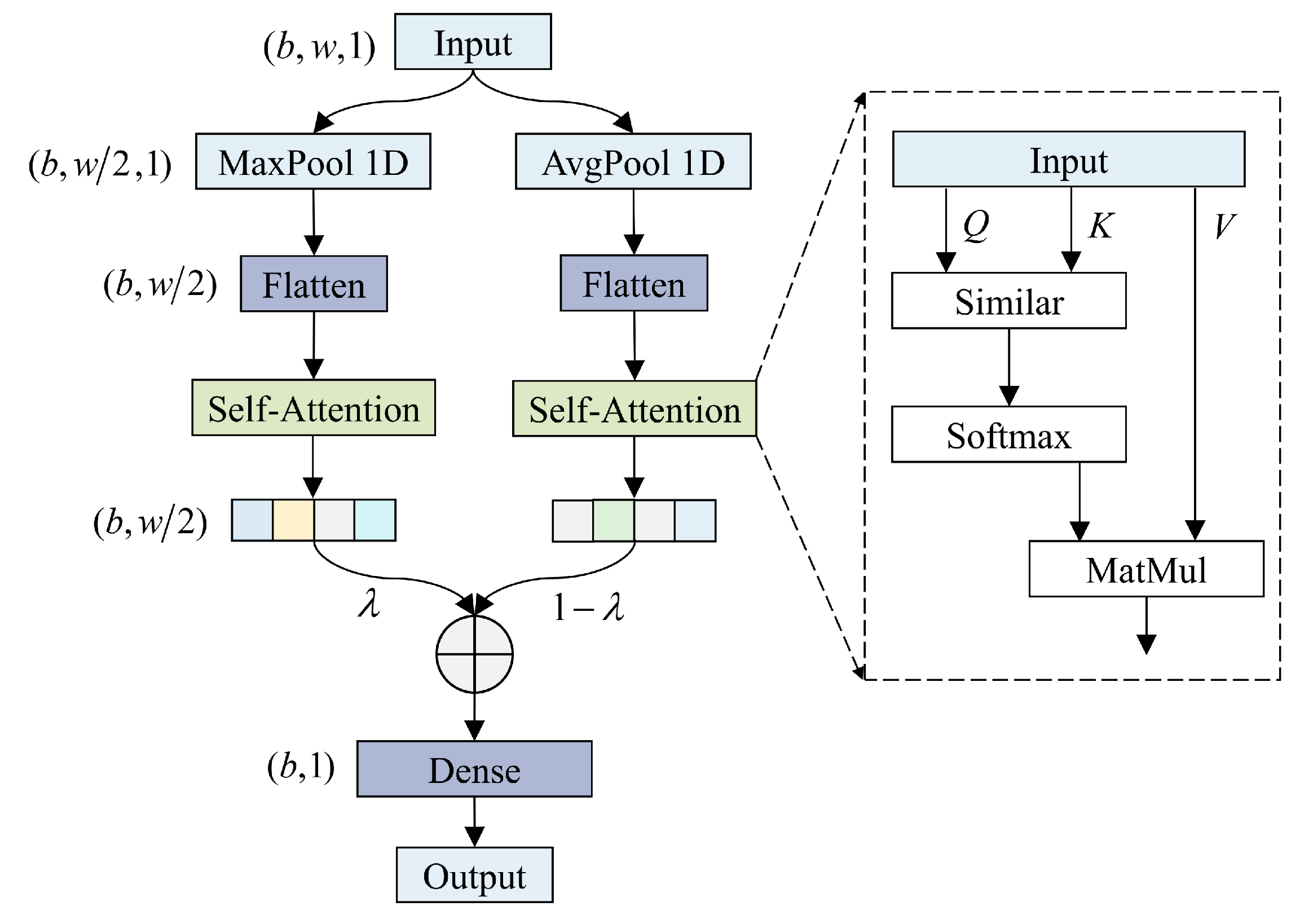

To evaluate the performance of the proposed method, we conducted a series of experiments with the measured radar data. First, we discussed the effect of DNN structure on prediction performance. Second, the contribution of KPM and KWF were performed. Third, to verify the performance of the proposed method, we compared the predicted values with those estimated by other empirical methods or state-of-the-art machine learning (ML) methods. Finally, we also provide further experiments to evaluate the generalization capability of the proposed method.

It can be noted that the proposed method was mainly implemented with the Keras framework and end-to-end trained on Windows workstation with a GPU of Nvidia Tesla V100S. Furthermore, the learning rate during the training process is equal to 10 × 10

−3. The batch size and epoch are set to 1024 and 100, respectively. Quantitatively, three common error indices were used to assess the prediction performance, namely the root mean square error (RMSE), Bias, and mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), with

where

and

are the

i-th predicted result and ground truth, respectively.

m is the number of data points.

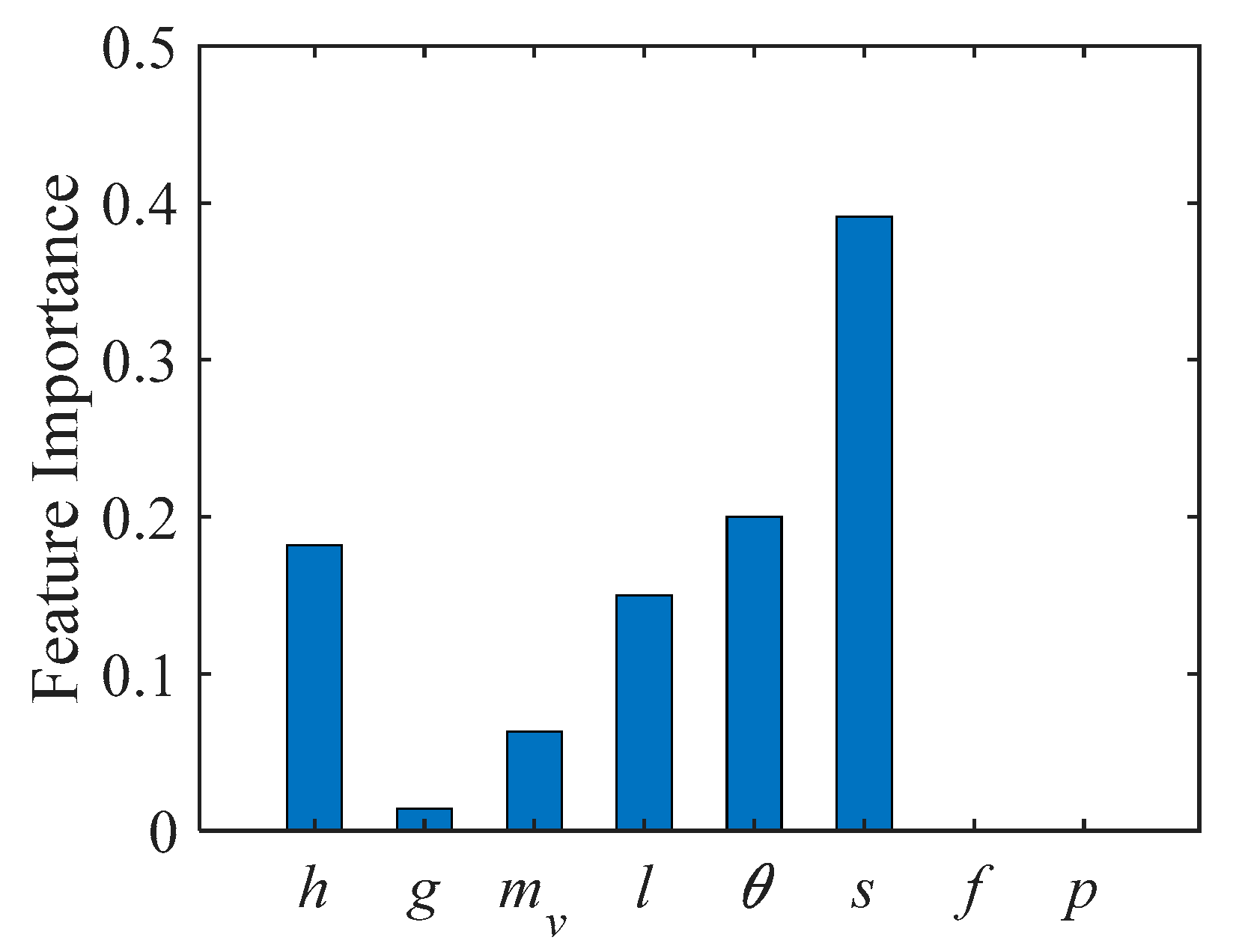

Before presenting the experimental results, it is worth mentioning at this point that we randomly selected 70% sets of the updated MFCD for training, 20% for validation, and the rest for testing. Furthermore, according to Equation (3), it can be observed that the input dimension is 8. Since principal component analysis (PCA) can reduce redundancy and stabilize training, we used PCA to decrease the dimension of the input variables, and the preserved principal components are equal to 6. Moreover, in order to minimize the biased predictions, all experiments were carried out with five independent tests, and the average values were reported for all the error indices.

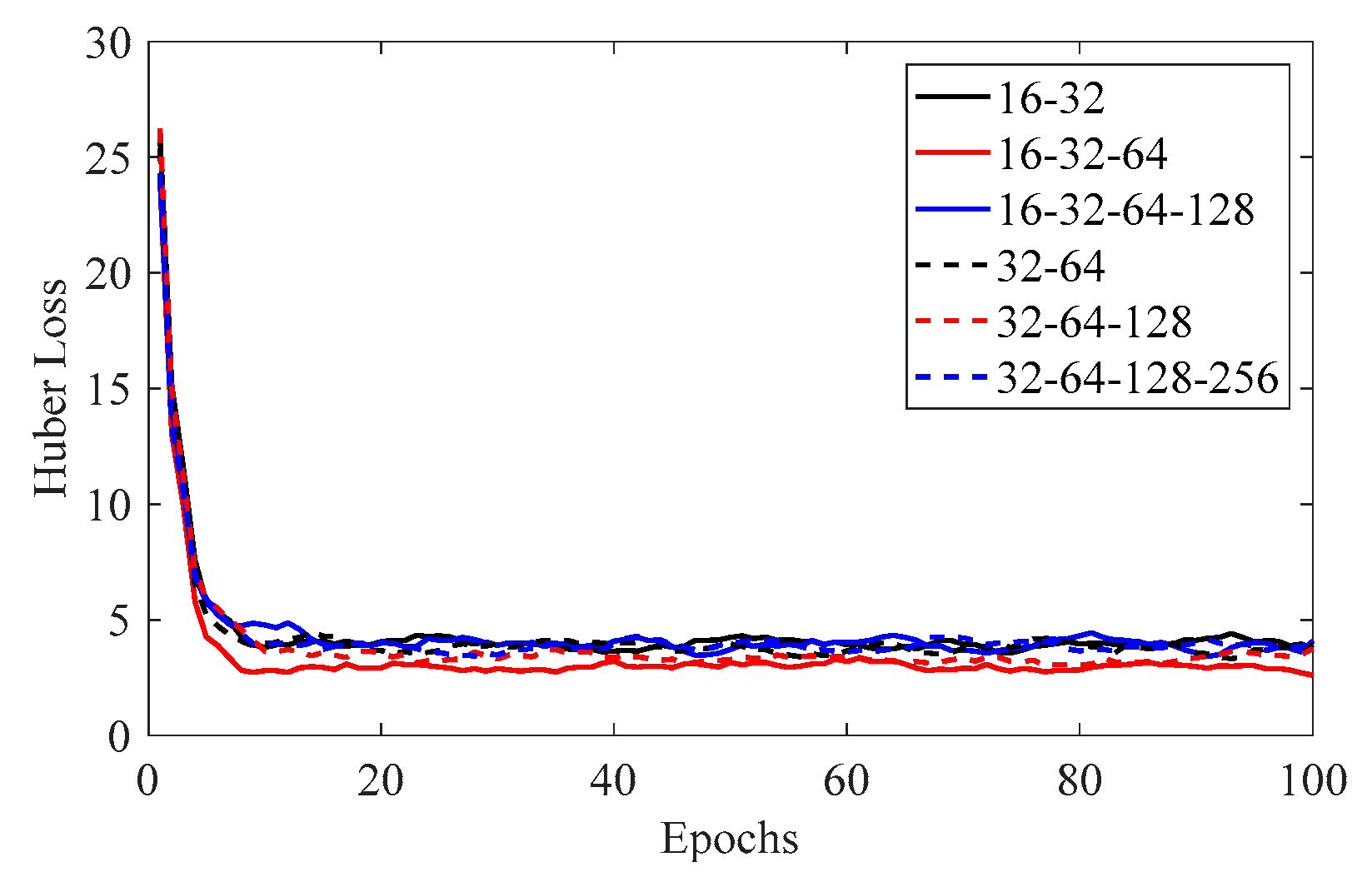

4.2. Optimization of the Cascaded DNN Solver

In order to improve the performance of the cascaded DNN solver and reduce the computational cost and time, a relatively optimal network structure must be performed before model training and prediction. Due to the excessive combinations of hidden layers and neurons, several alternatives are prepared in advance for convenience, i.e., 16-32, 16-32-64, 16-32-64-128, 32-64, 32-64-128, and 32-64-128-256, respectively. Note that, 16-32 denotes that the cascaded DNN solver is equipped with two hidden layers, and the neurons in each layer are 16 and 32, respectively.

Figure 5 shows the Huber loss of the above-mentioned cases. We can observe from

Figure 5 that, in the case of 16-32-64, the proposed method achieves the minimum loss value during the training process, while the other configurations have slightly larger ones. Moreover, we also calculate the error indices on test dataset for different configurations, and the results are listed in

Table 4. Similarly, it can be seen that the RMSE reaches the lowest value of 4.48 dB for the case of 16-32-64. When the cascaded DNN is configured with two or four hidden layers, the values of RMSE are slightly larger than those with three layers, e.g., the RMSEs of 16-32 and 16-32-64-128 are, respectively, 5.06 and 5.04 dB. This is because two hidden layers are not sufficient to adequately extract the features within the input, whereas four hidden layers achieve more redundant features, both of them reducing the model accuracy. Concerning the Bias, all configurations seem to overestimate the results of the test dataset. This may be explained by the fact that the complexity and variability of the surface features lead to a large dynamic range of radar echoes. Generally, MAPE represents the relative size of errors. From

Table 4, it can be observed that, when the DNN solver employs the configuration of 16-32-64, the model achieves the best MAPE with the lowest value of 10.6%, demonstrating that the relative error is minimized under this configuration.

In summary, the above outcomes demonstrate that when the configuration of the cascaded DNN is 16-32-64, the proposed method achieves the best performance, and therefore, all the subsequent experiments were conducted on this configuration.

4.3. Ablation Study

To quantitatively validate the effectiveness of each key component in our proposed KADL framework, we conducted a comprehensive ablation study on the test dataset. The experiment was designed to systematically evaluate the contribution of the KPM and the KWF strategy by progressively adding them to a baseline model. Specifically, we combined the different components into four groups, namely,

- (1)

Baseline: A standard DNN solver with three Dense layers (16-32-64 neurons) and ReLU activations, consistent with the structure illustrated in

Section 4.2. This model processes the raw input features without KPM and KWF.

- (2)

w/o KPM: The Baseline model enhanced with the KWF strategy but without the KPM. The KWF module processes the baseline features directly.

- (3)

w/o KWF: The Baseline model enhanced with the KPM, but without the KWF strategy. The output of the KPM is directly fed to the final regression layer.

- (4)

KADL: The complete proposed model incorporating both KPM and KWF components.

The quantitative results are shown in

Table 5. We can make the following observations from

Table 5. First, the Baseline achieves the worst performance, with the RMSE, Bias and MAPE reaching the values of 5.46 dB, 1.05 dB, and 14.9%, respectively. This indicates that while a powerful feature extraction method, pure data-driven DL model has inherent limitations in BC prediction tasks. Second, the results demonstrate both the KPM and KWF individually provide significant performance enhancements over the Baseline. Specifically, the model incorporating KWF (i.e., w/o KPM) show an obvious improvement, reducing the RMSE to 5.18 dB, and the MAPE to 13.6%. This observation confirms that KWF serves as an effective feature calibration mechanism. Similarly, w/o KWF also achieves a superior performance, with the RMSE of 5.22 dB, and MAPE of 13.3%, indicating its capability to capture meaningful representation from the input. Furthermore, an interesting phenomenon can also be observed that w/o KPM performs slightly better than w/o KWF, demonstrating that KWF contributes more significantly to the predictions. Third, the complete KADL model, which integrates both KPM and KWF, achieves the best performance across all metrics, with the RMSE of 4.84 dB, Bias of 0.67 dB, and MAPE of 11.2%. This result is not only better than the Baseline but also surpasses each ablated variant, proving that these two components are complementary.

In addition, we also evaluated the contribution of each component on different land covers, and the results are presented in

Table 6. In the first column of

Table 6, CL denotes Cultivated Land, WB stands for Water Bodies, GL and AS represent Grass Land and Artificial Surfaces, respectively. It can be observed that the proposed KADL demonstrates the best overall performance, achieving the lowest RMSE values over these five land covers. In terms of Bias and MAPE, the proposed KADL also shows excellent performance. It obtains the lowest Bias for Forest, GL, and WB, and the lowest MAPE for all of these five land covers. Furthermore, the performance of the ablated models (i.e., w/o KPM, and w/o KWF) consistently lies between the Baseline and the KADL model for the vast majority of cases. This observation confirms that both the KPM and the KWF strategy provide significant improvements regardless of the land cover type, indicating the integration of the KPM and the KWF strategy offers decisive advantages for radar backscatter prediction in complex, heterogeneous environments.

4.4. Comparative Experiments

For comprehensive benchmarking and to better verify the proposed KADL, our experimental design leverages diverse representative methods categorized as, (a) the empirical-based methods, i.e., NTCM, and ANTCM, (b) machine learning-based regressors, i.e., random forest (RF), (c) the state-of-the-art DL model, i.e., DNN, 1D convolutional neural network (1D CNN), and 1D CNN with Transformer, denoted as 1DCNNT, and (d) the proposed KADL.

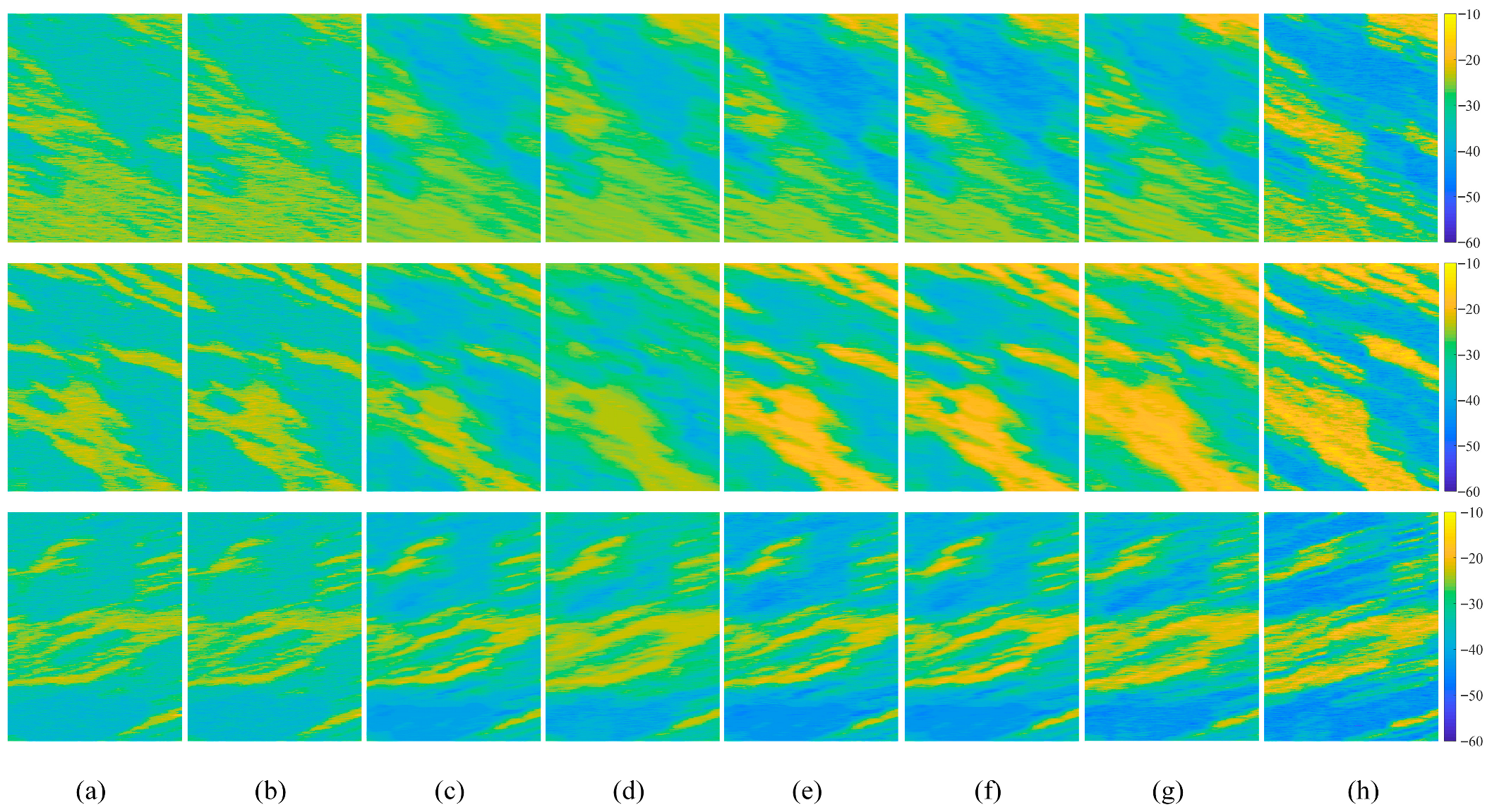

To intuitively visualize the predictions of the KADL method, we synthesized the predicted values as clutter maps based on the spatial coordinates of CCs. Typically, a clutter map provides absolute values of the BC for all CCs within the study area and represents the information on how the radar backscatter varies in the spatial domain.

Figure 6 presents three samples (namely T1, T2, and T3) of the predicted results for different methods. It can be noted that these samples consist of 400 × 100 CCs, i.e., each CC represents a pixel and is denoted by a BC. In general, all these methods can reconstruct the discriminative features of the terrains. Specifically, the performance of NTCM, ANTCM, and DNN is slightly inferior to that of KADL, while RF, 1DCNN, and 1DCNNT achieve comparable results.

To quantitively estimate these observations, the error indices are computed and listed in

Table 7. From this table, it can be seen that, for all of these samples, empirical-based methods achieve the worst predicted results. For example, the RMSEs of NTCM and ANTCM for sample T3 reach the values of 7.86 dB, and 7.73 dB, respectively. Similarly, the MAPEs for this case reach the values of 18.2%, and 17.9%, respectively, which are higher than those of other methods. Compared to NTCM, although ANTCM exhibits some improvement in accuracy, their results still fall short of satisfactory levels, sufficiently demonstrating the limitations of traditional empirical-based models. Conversely, RF, 1DCNN, and 1DCNNT achieve a relatively better performance, compared to empirical-based methods. Regarding the RMSE, RF, 1DCNN, and 1DCNNT show considerable improvement for these three samples. Taking T1 as an example, the RMSE values of RF, 1DCNN, and 1DCNNT are 5.19 dB, 5.08 dB, and 4.92 dB, respectively, demonstrating the effectiveness of these intelligence algorithms. It also can be observed that, compared to RF and 1DCNN, 1DCNNT achieves slightly better results in terms of all these error indices, indicating the powerful feature extraction capabilities of transformers. As expected, KADL reliably surpasses the performance of all these comparative methods, including the standard DNN, the 1DCNN, and the more advanced 1DCNNT. This observation validates that the integration of KPM and KWF modules provides a distinct advantage over purely data-driven architectures. In addition, regarding the Bias, all these methods seem to overestimate the BC. This can be explained by the fact that the interaction between radar signal and land surface is highly complex, thus rendering the inadequate characterization by current models.

Table 8 shows the standard deviation of the RMSE (std-RMSE) between five independent tests. Specifically, a lower std-RMSE indicates that the performance of models is more consistent and repeatable, while a higher std-RMSE suggests that the model is unstable and varies significantly from one trial to another, making its results less dependable. From

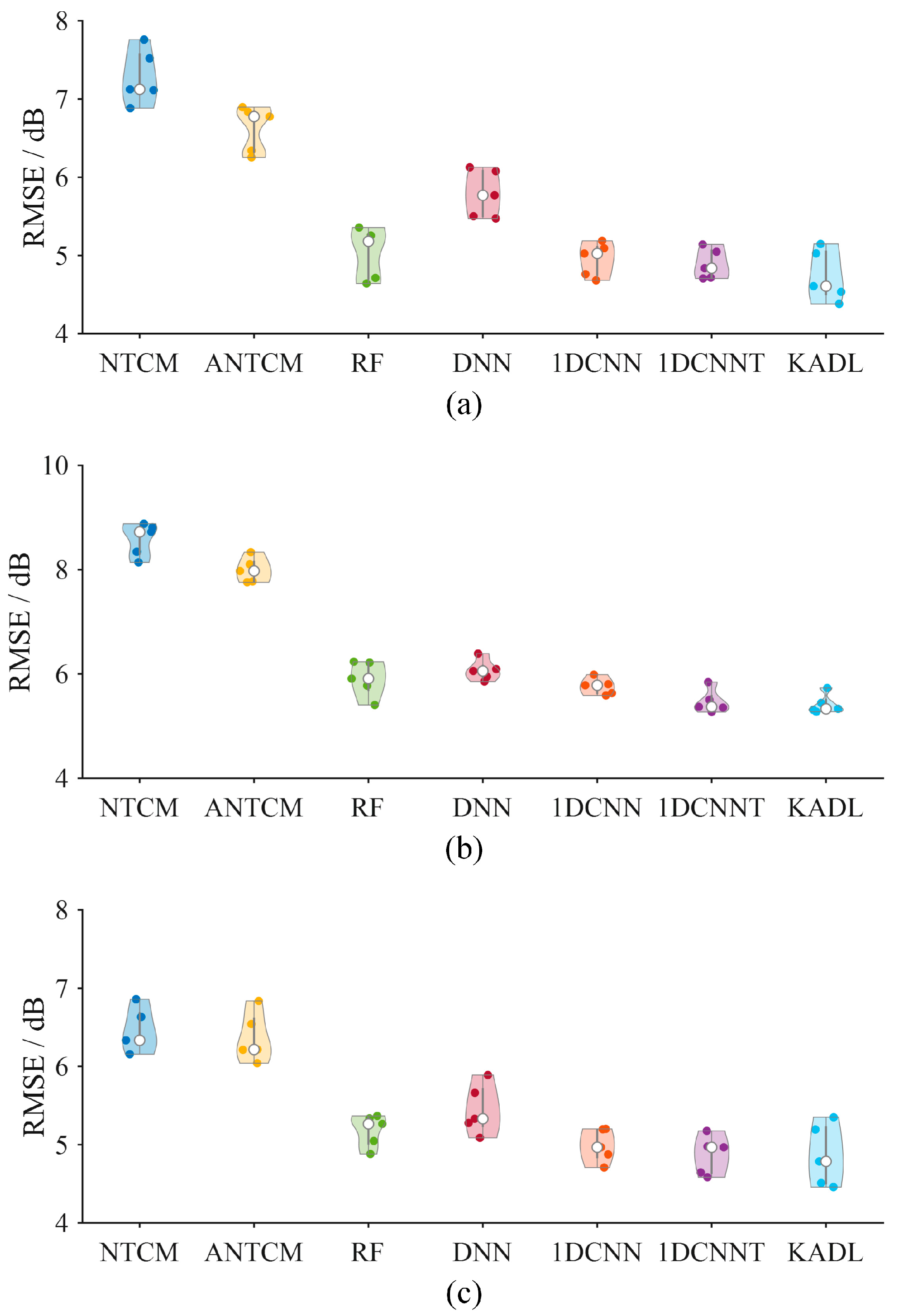

Table 8, we can see that, the std-RMSE of KADL is substantially lower than that of the empirical models (NTCM, and ANTCM) and the traditional machine learning model (RF), achieving the values of 0.22 dB, 0.19 dB, and 0.21 dB, respectively. It also shows a clear improvement in stability over the other DL models (DNN, 1DCNN, and 1DCNNT). Furthermore,

Figure 7 depicts the violin plots for RMSE distributions across five tests. It can be seen that KADL still exhibits strong robustness compared to other comparative methods, demonstrating its superiority.

The aforementioned results demonstrate that the proposed KADL perform better than empirical methods and ML methods in predicting BC from large areas, indicating the effectiveness of KADL. This is because KADL not only incorporates the effect of surface dielectric properties on radar backscatter, but also consistently focuses on the key features within the model construction.

4.5. Generalization Capability

A well-designed DL network requires not only a good accuracy on the test dataset, but also a good generalization to the new or unknown data. Therefore, we additionally registered the data of three areas (namely G1, G2, and G3) in the test region according to the method given in [

35] to evaluate the generalization capability of the proposed KA method. It should be noted that the data from these areas were not involved in the model training process.

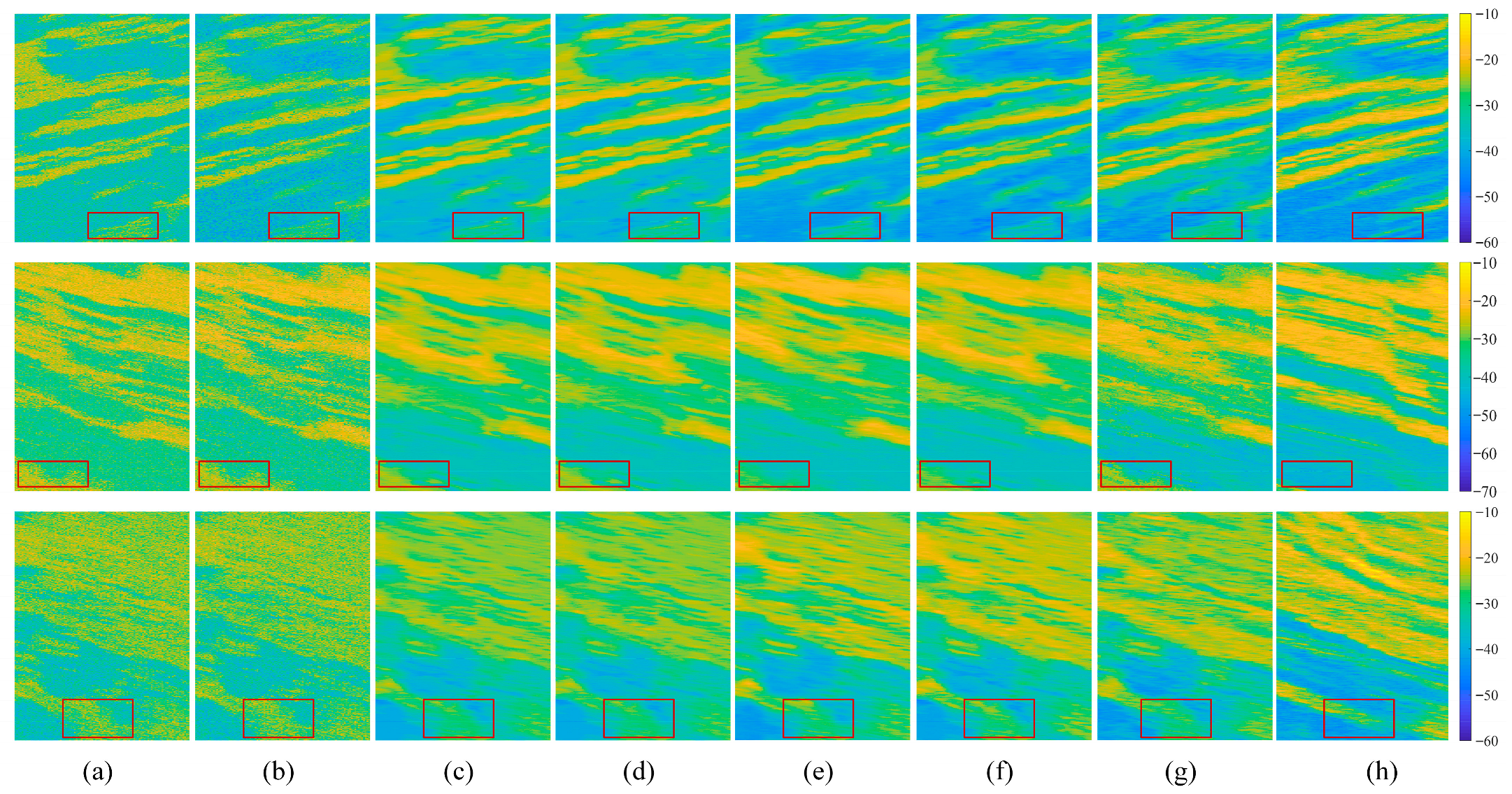

Figure 8 shows the clutter map of G1, G2, and G3 generated by different methods. In general, all these methods can reproduce the primary scattering characteristics of the study area. However, slight discrepancies can be observed visually between the predictions and the measured data in terms of amplitude. To quantitively estimate these differences,

Table 8 lists the corresponding error indices. We can make the following observations from

Table 9. First, empirical-based models, i.e., NTCM and ANTCM, yield the largest errors compared to other methods. For G2, they even obtain the RMSEs of 8.58 and 7.99 dB, proving the limitations of such models in real-world scenarios. Second, RF, and DNN give comparable predictions. More specifically, DNN performs somewhat behind, with higher RMSE values of 5.79 dB, 6.07 dB, and 5.45 dB for these three areas. Furthermore, 1DCNN and 1DCNNT obtain improved performance, with all the evaluation metrics better than RF and DNN. Third, with respect to Bias, almost all the models overestimate the measured BC. This occurrence presents further evidence of the intricate nonlinear relationship between radar signals and land features. Fourth, it is clear that the proposed KADL yields the best estimations, with the RMSE values of 4.74, 5.42, and 4.86 dB, respectively. This can be benefited from the fact that throughout the construction of KADL, KPM and KWF consistently focus on the contribution of key features to the BC, thus improving the generalization ability of the proposed method. Furthermore, regarding to the MAPE, KADL also yields the best results, with the values of 8.7%, 9.9%, and 10.8%, respectively.

Table 10 presents the std-RMSE across these three samples. As can be seen in this table, the proposed KADL model demonstrates exceptional stability, achieving the lowest std-RMSE on both the G1 (0.19 dB) and G3 (0.18 dB) test samples. As for the G2, 1DCNNT obtains the comparable results, with the std-RMSE reaching the value of 0.21 dB.

Figure 9 shows the violin plots for RMSE distributions, further demonstrating that the proposed KADL framework is not only more accurate but also significantly more robust and reliable than the benchmark models.

To further explore the robustness of the proposed method, we provide the boxplot for different methods, and the results are shown in

Figure 9. In general, box plots indicate the dispersion of the reference data by means of statistical indicators. As can be seen in

Figure 9, empirical-based methods are more sensitive to the outliers (i.e., red dotted line), with the largest differences acquired for all three areas. RF, DT, SVM and DNN obtain similar results, but both outperform NTCM and ANTCM. Furthermore, the proposed KADL achieves the best results and is more robust to outliers as expected (see

Figure 9), indicating the superiority of KADL for estimating the BC for complex scenarios.