Dominant Role of Meteorology and Aerosols in Regulating the Seasonal Variation of Urban Thermal Environment in Beijing

Highlights

- Meteorology and aerosol optical depth (AOD) are the main driving factors for the seasonal variation of Land Surface Temperature (LST) in Beijing.

- The influence of aerosols on LST changes significantly with seasons, while precipitation provides a relatively stable cooling effect.

- In the context of relatively stable urban buildings, the response of Beijing’s urban thermal environment to external influencing factors is mostly nonlinear.

- Managers should comprehensively consider the synergistic relationship between urban landscape and atmospheric environment to alleviate urban thermal environment.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

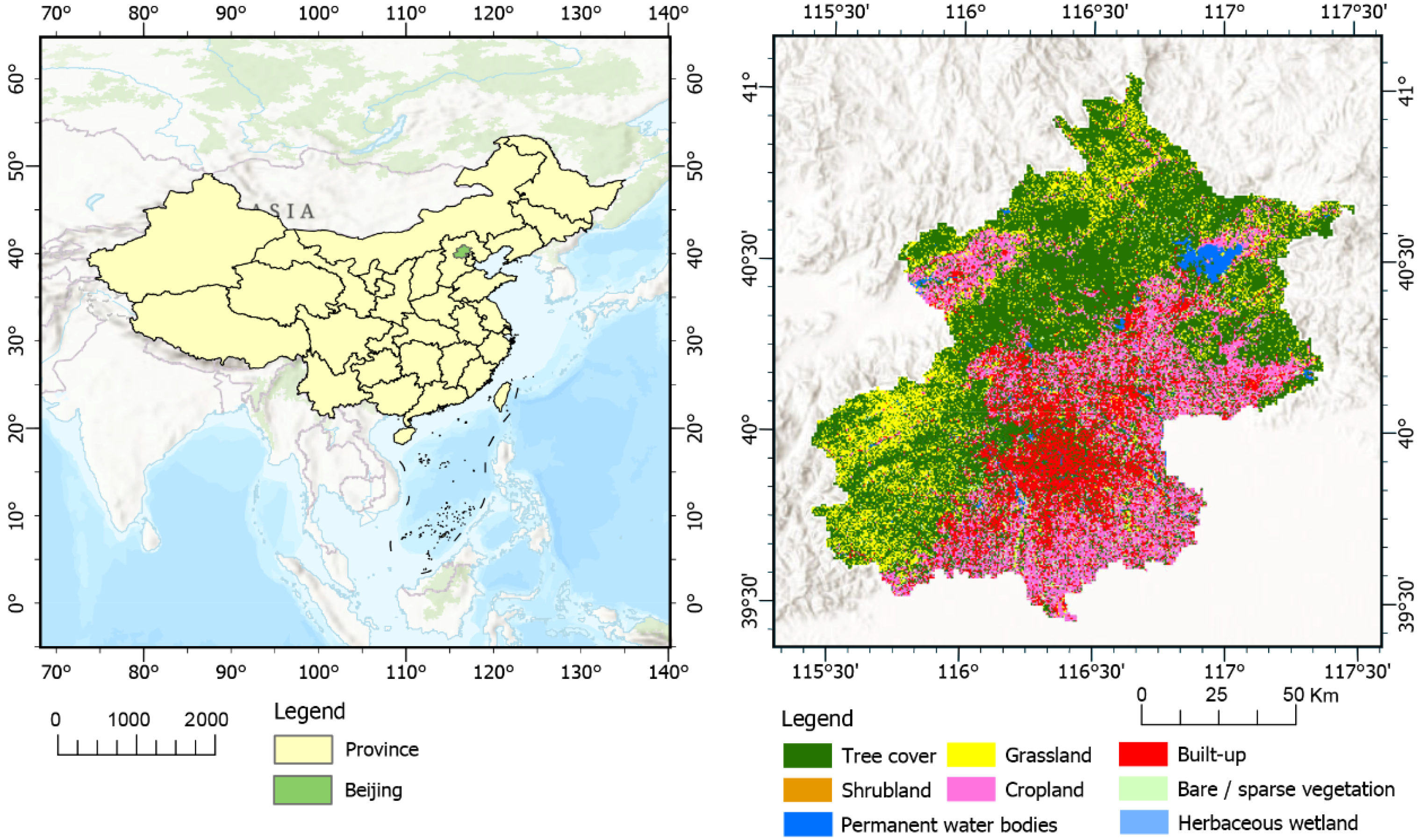

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Source

2.3. Multicollinearity Examination

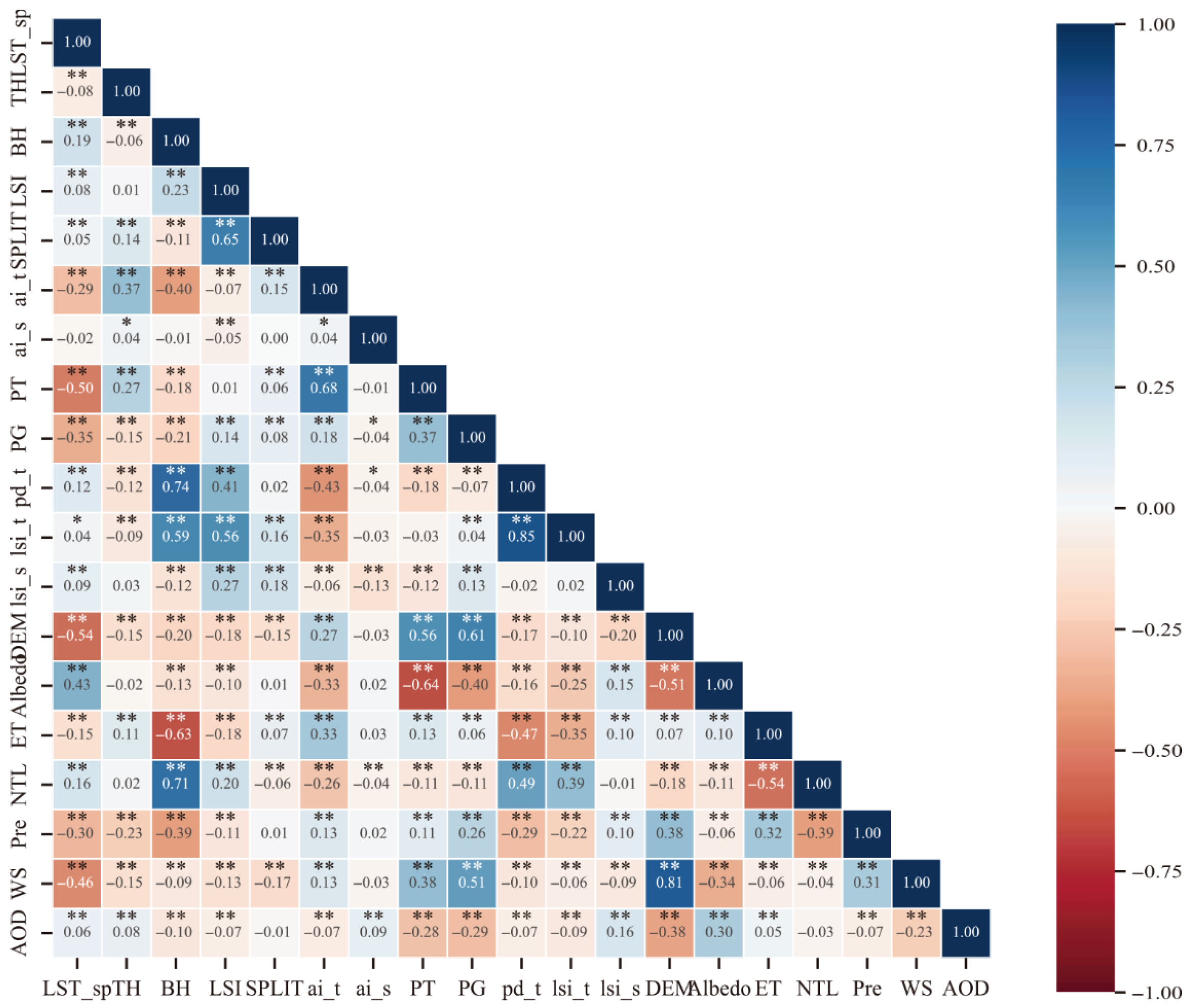

2.4. Correlation Analysis

2.5. Analysis of Influencing Factors

3. Results

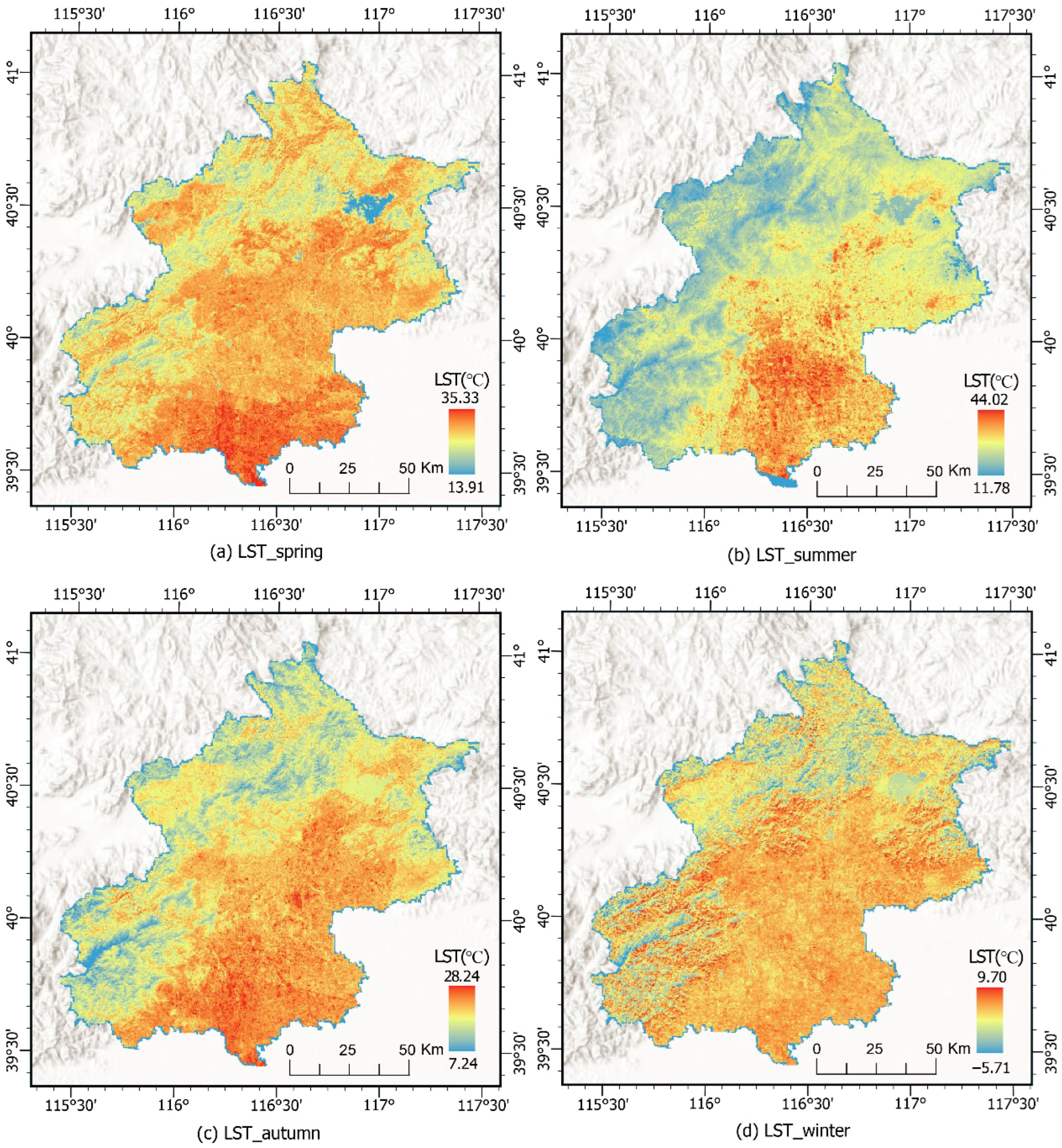

3.1. Spatiotemporal Variation in LST

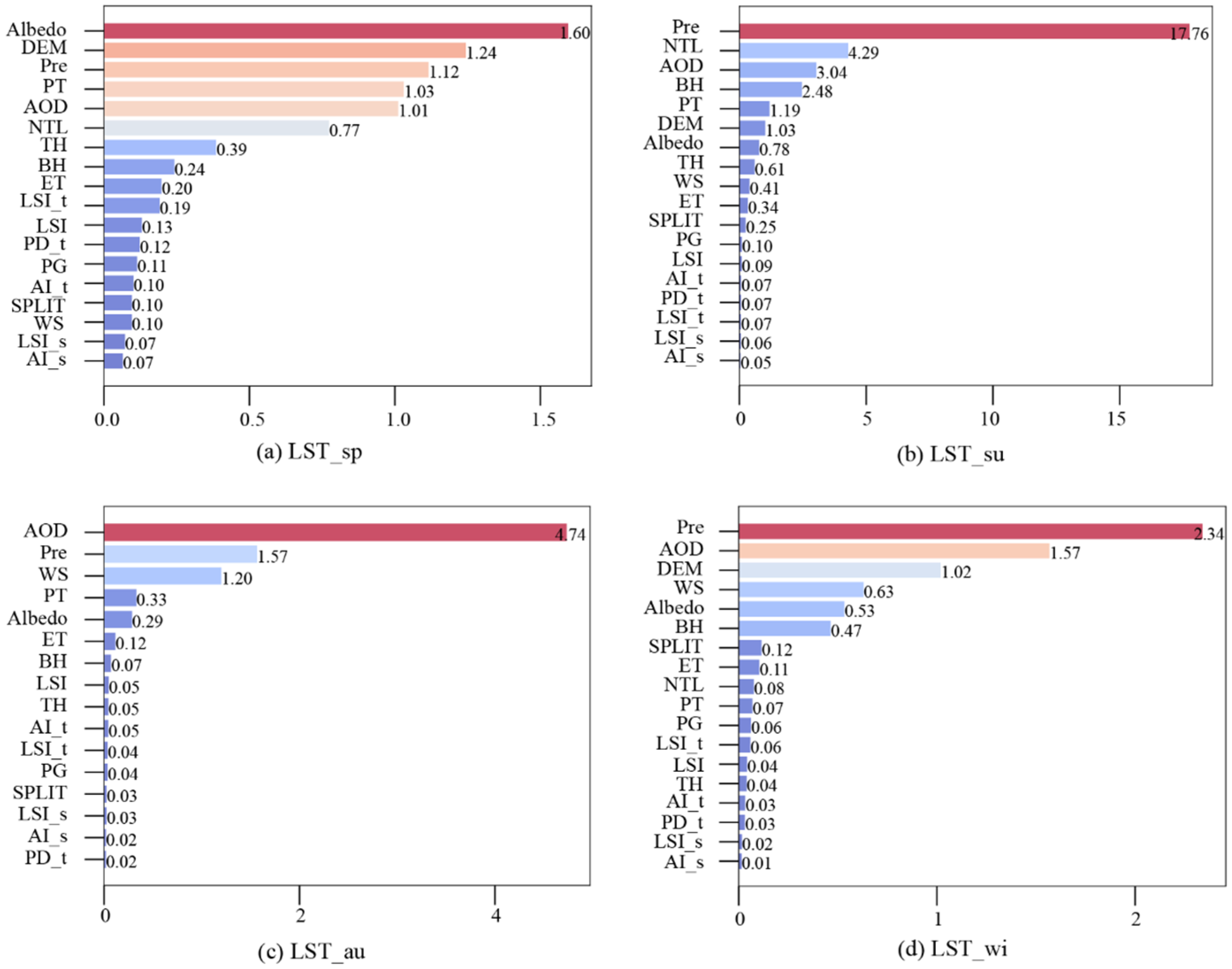

3.2. Relative Impacts of Urban Features on LST

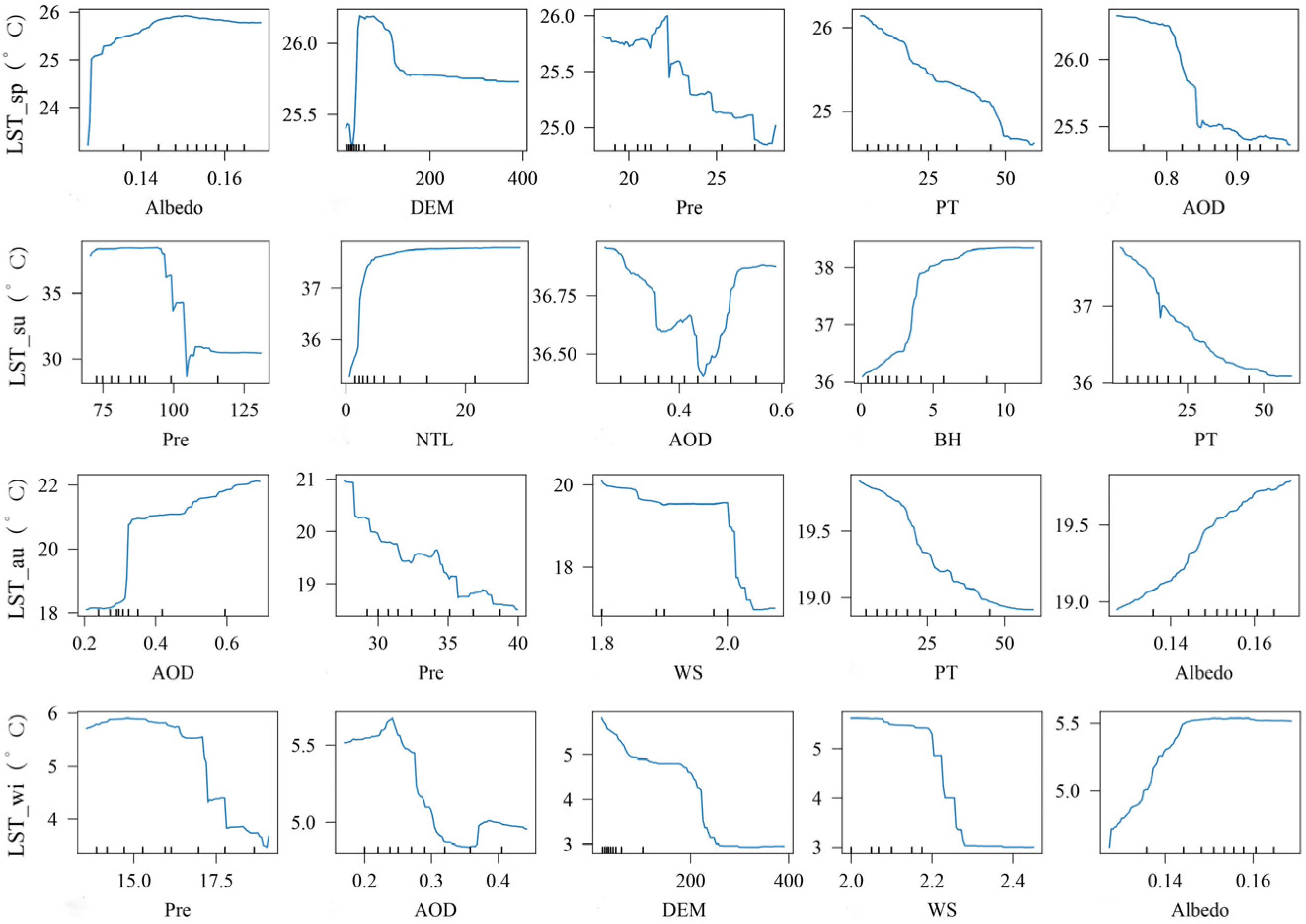

3.3. Marginal Effects of the Main Indicators on LST

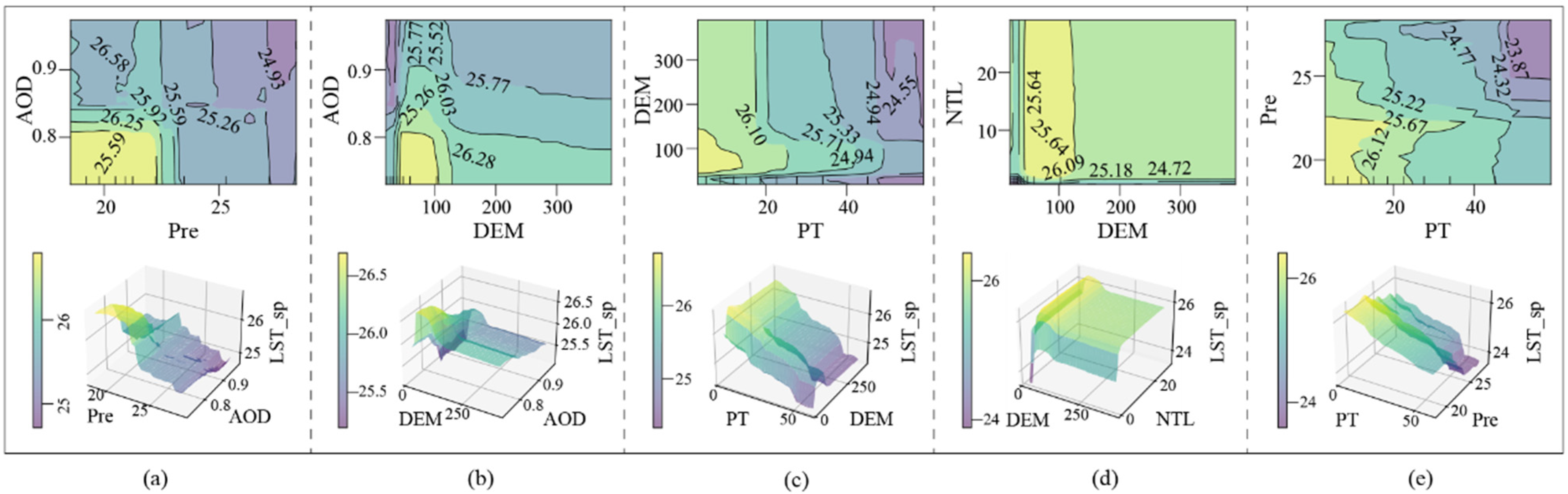

3.4. Interaction Effects of the Main Indicators on LST

4. Discussion

4.1. The Effect of a Single Variable on LST

4.2. Interaction Effects of Various Variables on LST

4.3. Implications for Urban Planning and Management

4.4. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abhijith, K.V.; Kumar, P.; Gallagher, J.; McNabola, A.; Baldauf, R.; Pilla, F.; Broderick, B.; Di Sabatino, S.; Pulvirenti, B. Air pollution abatement performances of green infrastructure in open road and built-up street canyon environments—A review. Atmos. Environ. 2017, 162, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Qiao, Z. Synergizing climate, energy, and air quality: Uncovering urban heat island, energy consumption, carbon emission, and air pollution nexus linkages. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2026, 117, 108202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokaie, M.; Zarkesh, M.K.; Arasteh, P.D.; Hosseini, A. Assessment of Urban Heat Island based on the relationship between land surface temperature and Land Use/Land Cover in Tehran. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2016, 23, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahed, J.; Kinab, E.; Ginestet, S.; Adolphe, L. Impact of urban heat island mitigation measures on microclimate and pedestrian comfort in a dense urban district of Lebanon. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 61, 102375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, P.; Sun, F.; Liu, Y.; Tian, T.; Wu, J.; Dong, Q.; Peng, S.; Che, Y. The influence of the landscape pattern on the urban land surface temperature varies with the ratio of land components: Insights from 2D/3D building/vegetation metrics. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 78, 103599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatvani-Kovacs, G.; Belusko, M.; Skinner, N.; Pockett, J.; Boland, J. Heat stress risk and resilience in the urban environment. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2016, 26, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, J.; Alqadhi, S. Explainable artificial intelligence models for proposing mitigation strategies to combat urbanization impact on land surface temperature dynamics in Saudi Arabia. Urban Clim. 2025, 59, 102259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Zhong, R.; Liu, M.; Ye, C.; Chen, X. Spatiotemporal distribution characteristics of PM2.5 concentration in China from 2000 to 2018 and its impact on population. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 323, 116273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Hu, D.; Schlink, U. A new nonlinear method for downscaling land surface temperature by integrating guided and Gaussian filtering. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 271, 112915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, D.-K.; Brown, R.D.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.-H.; Sung, S. The effect of extremely low sky view factor on land surface temperatures in urban residential areas. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 80, 103799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Huang, C.; Huang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, X. Seasonal variations of the dominant factors for spatial heterogeneity and time inconsistency of land surface temperature in an urban agglomeration of central China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 75, 103285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgarian, A.; Amiri, B.J.; Sakieh, Y. Assessing the effect of green cover spatial patterns on urban land surface temperature using landscape metrics approach. Urban Ecosyst. 2015, 18, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Han, G.; Li, L.; Qin, H. The impact of macro-scale urban form on land surface temperature: An empirical study based on climate zone, urban size and industrial structure in China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 74, 103217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Qiao, R.; Liu, Y.; Blaschke, T.; Li, S.; Wu, J.; Xu, Z.; Liu, Q. A wavelet coherence approach to prioritizing influencing factors of land surface temperature and associated research scales. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 246, 111866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, D.; Wang, H. The dominant factors and influence of urban characteristics on land surface temperature using random forest algorithm. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 79, 103722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, Y.; Bao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wei, W.; Chen, X. Spatial coupling relationship between architectural landscape characteristics and urban heat island in different urban functional zones. Build. Environ. 2024, 257, 111545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Wang, C.; Guo, Y.; Hong, S.; Zhang, P.; Ma, Z.; Hong, W.; Wang, X.; Geng, R.; Meng, F. The cooling capacity of urban vegetation and its driving force under extreme hot weather: A comparative study between dry-hot and humid-hot cities. Build. Environ. 2024, 263, 111901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Ren, Z.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, P.; Hong, S.; Ma, Z.; Hong, W.; Wang, X. Assessing urban population exposure risk to extreme heat: Patterns, trends, and implications for climate resilience in China (2000–2020). Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 103, 105260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Zhao, L.; Oleson, K.W. Large model structural uncertainty in global projections of urban heat waves. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Dai, F.; Yang, B.; Zhu, S. Effects of urban green space morphological pattern on variation of PM2.5 concentration in the neighborhoods of five Chinese megacities. Build. Environ. 2019, 158, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, X.; Qian, J.; Lu, Y.; Yang, X. Mapping fine-scale anthropogenic heat flux in Shanghai by integrating multi-source geospatial big data using Cubist. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 101, 105125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Q.; Dong, Y.; Dong, W.; Xiao, S. Spatiotemporal dynamics and nonlinear landscape-driven mechanisms of urban heat islands in a winter city: A case study of Harbin, China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 133, 106842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.F.; Dai, Z.X.; Guldmann, J.M. Modeling the impact of 2D/3D urban indicators on the urban heat island over different seasons: A boosted regression tree approach. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 266, 110424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Leung, L.; Zhao, N.; Zhao, C.; Qian, Y.; Hu, K.; Liu, X.; Chen, B. Contribution of urbanization to the increase of extreme heat events in an urban agglomeration in east China. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2017, 44, 6940–6950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Wang, J.; Cadenasso, M.L. Effects of the spatial configuration of trees on urban heat mitigation: A comparative study. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 195, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, K.; Li, K.; Ma, M.; Li, K.; Li, Z.; Guo, J.; Chang, N.-B.; Tan, Z.; Han, D. LGHAP: The Long-term Gap-free High-resolution Air Pollutant concentration dataset, derived via tensor-flow-based multimodal data fusion. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2022, 14, 907–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, X.; Meng, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, H. Exploring the impact of urban features on the spatial variation of land surface temperature within the diurnal cycle. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 91, 104432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Yue, W.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Lu, D. Spatiotemporal patterns of summer urban heat island in Beijing, China using an improved land surface temperature. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 257, 120529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Fan, S.; Guo, C.; Wu, F.; Zhang, N.; Dong, L. Assessing the effects of landscape design parameters on intra-urban air temperature variability: The case of Beijing, China. Build. Environ. 2014, 76, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D.P.; Wulder, M.A.; Loveland, T.R.; Woodcock, C.E.; Allen, R.G.; Anderson, M.C.; Helder, D.; Irons, J.R.; Johnson, D.M.; Kennedy, R.; et al. Landsat-8: Science and product vision for terrestrial global change research. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 145, 154–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; An, H.; Wang, F.; Xu, X.; Qiao, Z.; Wang, M.; Sui, X.; Liang, S.; Hou, X.; Cai, H.; et al. Understanding seasonal contributions of urban morphology to thermal environment based on boosted regression tree approach. Build. Environ. 2022, 226, 109770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoud, J.I. Multicollinearity and regression analysis. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2017, 949, 012009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zheng, L.; Wang, Y. Revealing the Roles of Climate, Urban Form, and Vegetation Greening in Shaping the Land Surface Temperature of Urban Agglomerations in the Yangtze River Economic Belt of China. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 377, 124602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logan, T.M.; Zaitchik, B.; Guikema, S.; Nisbet, A. Night and day: The influence and relative importance of urban characteristics on remotely sensed land surface temperature. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 247, 111861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, H.; Yang, Y.; Li, J. Surface albedo regulates aerosol direct climate effect. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manoli, G.; Fatichi, S.; Schläpfer, M.; Yu, K.; Crowther, T.W.; Meili, N.; Burlando, P.; Katul, G.G.; Bou-Zeid, E. Magnitude of urban heat islands largely explained by climate and population. Nature 2019, 573, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, S.; Piao, S.; Ciais, P.; Friedlingstein, P.; Ottle, C.; Bréon, F.-M.; Nan, H.; Zhou, L.; Myneni, R.B. Surface urban heat island across 419 global big cities. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 696–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Yang, Z.; Lo, M.H.; Hur, J.; Im, E.-S. Deciphering the capricious precipitation response: Irrigation impact in the North China Plain. Npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2025, 8, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Gu, X.; Slater, L.J.; Liu, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Kong, D. Urbanization-induced increases in heavy precipitation are magnified by moist heatwaves in an urban agglomeration of East China. J. Clim. 2023, 36, 693–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, L.; Liu, S.; Yang, Y.; Ren, G.; Yu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y. Synergistic influence of local climate zones and wind speeds on the urban heat island and heat waves in the megacity of Beijing, China. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 9, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Li, X.-X.; Zhang, X.; Yin, T.; Norford, L.K.; Yuan, C. Estimation of anthropogenic heat from buildings based on various data sources in Singapore. Urban Clim. 2023, 49, 101434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, C.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yang, X.; Fan, H.; Zhao, X.; Yang, J. Vertical Dependency of Aerosol Impacts on Local Scale Convective Precipitation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2023, 50, e2022GL102186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Guo, J.; Li, J.; Shao, J.; Tong, B.; Zhang, S. The Prestorm Environment and Prediction for Local- and Nonlocal-Scale Precipitation: Insights Gained from High-Resolution Radiosonde Measurements Across China. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2022, 127, e2021JD036395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zeng, X.; Huang, Y.; Li, X. Analysing urban local cold air dynamics and climate functional zones using interpretable machine learning: A case study of Tianhe district, Guangzhou. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 114, 105731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, Y.; Zhang, D.-L.; Gao, W.; Yin, J.; Zhao, C.; Li, J.; Guo, J.; Liu, H. Spatiotemporal Variations of the Effects of Aerosols on Clouds and Precipitation in an Extreme-Rain-Producing MCS in South China. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2024, 129, e2023JD040014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Ye, Y.; Peng, C.C.; Teng, M.J.; Zhou, Z.X. Seasonal variations for combined effects of landscape metrics on land surface temperature (LST) and aerosol optical depth (AOD). Ecol. Indic. 2022, 138, 108810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauwaet, D.; Berckmans, J.; Hooyberghs, H.; Wouters, H.; Driesen, G.; Lefebre, F.; De Ridder, K. High-Resolution Modelling of the Urban Heat Island of 100 European Cities (2008–2017). Urban Clim. 2024, 54, 101850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.J.; de Beurs, K.M.; Wynne, R.H. Dryland vegetation phenology across an elevation gradient in Arizona, USA, inves-tigated with fused MODIS and Landsat data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 144, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.; Guo, X. Disparities in the impact of urban heat island effect on particulate pollutants at different pollution stages—A case study of the “2 + 36” cities. Urban Clim. 2025, 59, 102273. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, C.; Qi, L.; Chu, H. Analysis of the midsummer local convection distribution and weather factors under the control of the Western Pacific subtropical high in the Yangtze Delta region of China. J. Meteorol. Environ. 2023, 39, 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T.; Qiao, Z. Synergistic governance of urban heat islands, energy consumption, carbon emissions, and air pollution in China: Evidence from a spatial durbin model. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 372, 126025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Zhou, Y.; Asrar, G.R.; Zhu, Z. Creating a seamless 1 km resolution daily land surface temperature dataset for urban and surrounding areas in the conterminous United States. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 206, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Yao, F.; Stouffs, R.; Wu, J. An integrated framework for jointly assessing spatiotemporal dynamics of surface urban heat island intensity and footprint: China, 2003–2020. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 112, 105601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data | Spatial Resolution | URL |

|---|---|---|

| LST/Albedo | 30 m | http://earthexplorer.usgs.gov (accessed on 27 July 2025) |

| ESA World Cover 2020 | 10 m | https://worldcover2020.esa.int/ (accessed on 6 July 2025) |

| Aerosol | 1 km | https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5652257 (accessed on 29 June 2025) |

| DEM | 30 m | https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/ (accessed on 29 June 2025) |

| NTL | 500 m | https://www.ngdc.noaa.gov/eog/viirs (accessed on 30 July 2025) |

| GFCH | 30 m | https://glad.umd.edu/dataset/gedi (accessed on 24 November 2025) |

| Evapotranspiration | 500 m | https://search.earthdata.nasa.gov/search?q=MOD16A2 (accessed on 13 July 2025) |

| Precipitation | 0.1° | https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets (accessed on 14 June 2025) |

| Category of Variables | Variable | Meaning of Variable |

|---|---|---|

| Buildings and landscape | BH | Average height of each building |

| SPLIT | Landscape type separation index | |

| LSI | Landscape shape index reflects patch shape complexity | |

| lsi_t | Landscape shape index of trees | |

| lsi_s | Landscape shape index of shrubs | |

| pd_t | Patch density of trees | |

| ai_t | Landscape aggregation index of trees | |

| ai_s | Landscape aggregation index of shrubs | |

| Vegetation index | TH | Average height of trees |

| PT | Percentage of tree area | |

| PG | Percentage of grassland area | |

| Natural environmental | DEM | Average elevation of the grid |

| Albedo | Average surface albedo value | |

| ET | Mean value of evapotranspiration | |

| Pre | Mean value of precipitation | |

| WS | Mean value of wind speed | |

| Human activity | NTL | Mean value of NTL for the detection of human activity |

| AOD | Average aerosol optical depth represents the atmospheric pollution |

| Metrics | LST_sp (°C) | LST_su (°C) | LST_au (°C) | LST_wi (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 25.59 | 36.91 | 19.50 | 5.33 |

| Standard Deviation | 2.47 | 4.42 | 2.50 | 2.05 |

| Min | 13.91 | 11.78 | 7.12 | −5.71 |

| Max | 35.33 | 44.02 | 28.24 | 9.70 |

| Season | R2 | RMSE |

|---|---|---|

| Spring | 0.67 | 1.44 |

| Summer | 0.85 | 1.90 |

| Autumn | 0.89 | 0.84 |

| Winter | 0.85 | 0.86 |

| Dependent Variable | Rank | Characteristic Quantity Group | H-Statistic |

|---|---|---|---|

| LST_sp | 1 | Pre vs. AOD | 0.12 |

| 2 | DEM vs. AOD | 0.10 | |

| 3 | PT vs. DEM | 0.07 | |

| 4 | DEM vs. NTL | 0.07 | |

| 5 | PT vs. Pre | 0.06 | |

| LST_su | 1 | NTL vs. Pre | 0.36 |

| 2 | Pre vs. AOD | 0.26 | |

| 3 | BH vs. Pre | 0.17 | |

| 4 | PT vs. Pre | 0.11 | |

| 5 | TH vs. Pre | 0.09 | |

| LST_au | 1 | WS vs. AOD | 0.37 |

| 2 | Pre vs. AOD | 0.18 | |

| 3 | Pre vs. WS | 0.09 | |

| 4 | PT vs. WS | 0.06 | |

| 5 | PT vs. AOD | 0.05 | |

| LST_wi | 1 | Pre vs. AOD | 0.33 |

| 2 | Albedo vs. WS | 0.21 | |

| 3 | DEM vs. Albedo | 0.21 | |

| 4 | DEM vs. Pre | 0.19 | |

| 5 | Pre vs. WS | 0.16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, S.; Yang, Y.; Wang, H.; Fan, H.; Qi, J.; Lai, X. Dominant Role of Meteorology and Aerosols in Regulating the Seasonal Variation of Urban Thermal Environment in Beijing. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3921. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233921

Zhang S, Yang Y, Wang H, Fan H, Qi J, Lai X. Dominant Role of Meteorology and Aerosols in Regulating the Seasonal Variation of Urban Thermal Environment in Beijing. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(23):3921. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233921

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Shiyu, Yan Yang, Haitao Wang, Hao Fan, Jiayun Qi, and Xiuting Lai. 2025. "Dominant Role of Meteorology and Aerosols in Regulating the Seasonal Variation of Urban Thermal Environment in Beijing" Remote Sensing 17, no. 23: 3921. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233921

APA StyleZhang, S., Yang, Y., Wang, H., Fan, H., Qi, J., & Lai, X. (2025). Dominant Role of Meteorology and Aerosols in Regulating the Seasonal Variation of Urban Thermal Environment in Beijing. Remote Sensing, 17(23), 3921. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233921