1. Introduction

With the rapid development of remote sensing technology and its widespread applications in land monitoring, urban planning, natural disaster assessment, and battlefield situation awareness, change detection (CD) based on remote sensing imagery has become a key research direction in Earth observation [

1,

2]. Change detection aims to compare remote sensing data of the same area acquired at different times to identify spatial or attribute changes of ground objects, thereby enabling the monitoring and analysis of the dynamic evolution of surface targets [

3,

4]. In particular, for tasks such as natural disaster response, emergency management, and damage assessment, change detection can provide governments or military departments with first-hand data support, enabling rapid response and precise deployment.

Among various change detection tasks, building damage detection, as a fine-grained and target-specific form of change detection, has attracted increasing attention in recent years [

5,

6]. As the primary carriers of urban spatial structure, buildings serve as direct indicators of the intensity of disasters or attacks in a given area. In particular, after war conflicts or major natural disasters, timely and accurate acquisition of building damage information is of great significance for rescue operations, post-disaster reconstruction, and war impact assessment [

7,

8]. Compared with traditional ground surveys, remote sensing imagery offers advantages such as wide coverage, high timeliness, and repeatable acquisition, making it an ideal tool for war damage monitoring and assessment [

9,

10].

Although change detection techniques have made initial progress in disaster remote sensing, building damage change detection based on remote sensing imagery still faces multiple challenges [

11]. First, unlike macroscopic changes such as land cover transitions or urban expansion, building damage typically manifests as structural destruction, occlusion damage, or partial collapse, which are more fine-grained and irregular. Second, in complex battlefield environments, images are often affected by shadows, smoke, occlusions, and ground disturbances, which severely impair a model’s ability to accurately identify true change regions. More critically, there is a lack of publicly available, high-quality datasets of real war-scene building damage. Most existing studies rely on simulated or synthetic data, resulting in limited model generalization and difficulty in meeting the requirements of real-world deployment.

With the rapid advancement of artificial intelligence, particularly the widespread adoption of deep learning in image classification [

12], semantic segmentation [

13], and object detection [

14], remote sensing image change detection has gradually shifted from traditional image differencing methods [

15] and machine learning approaches [

16] toward end-to-end strategies based on deep neural networks [

17]. The introduction of dual-branch structures (e.g., Siamese Networks) [

18], attention mechanisms [

19], and Transformer architectures [

20] has greatly enhanced the ability of models to represent and robustly detect changes in complex scenarios. In recent years, the rise of foundation models [

21]—notably under the pretraining–fine-tuning paradigm—has attracted significant attention in computer vision. Among them, Meta’s Segment Anything Model (SAM), as a foundation model for segmentation, demonstrates powerful cross-task transferability and fine-grained boundary perception. It can generate high-quality segmentation masks without task-specific annotations, offering new solutions for weakly supervised or zero-shot remote sensing tasks. However, current foundation vision models like SAM are primarily designed for natural images, and their direct application to remote sensing imagery often leads to semantic shifts and structural misinterpretations [

22]. Effectively integrating the prior knowledge of foundation models into task-specific remote sensing networks thus remains an urgent research direction.

At the same time, the development of lightweight neural network models has provided new tools for efficient remote sensing analysis. The recently proposed Mamba architecture [

23], which models long-range dependencies through linear recurrent units, achieves a balance between lightweight design and strong temporal modeling capabilities. Its introduction into image modeling tasks has opened new pathways for feature representation beyond CNNs and Transformers, indicating potential advantages for remote sensing change detection in terms of both efficiency and temporal feature extraction.

However, despite these advancements, existing building damage detection methods still face significant limitations that hinder their applicability in real-world complex scenarios. Many CNN- and Transformer-based approaches struggle with structural consistency modeling, making it difficult to maintain the coherence of building geometry under non-rigid deformations, fragmented destruction, or occlusions. Similarly, their adaptability to complex war-zone environments remains insufficient, as fuzzy boundaries, small-scale damage, and cluttered backgrounds often lead to missed or misclassified change regions. While SAM provides strong structural priors and Mamba offers efficient sequence modeling, current approaches still lack an effective mechanism to integrate these complementary strengths.

In addition to these methodological gaps, several critical challenges remain in building damage change detection. First, data scarcity is a major obstacle: there is a lack of publicly available, real, and representative datasets of damaged buildings in remote sensing imagery, particularly from actual war scenarios. This severely limits model training, performance evaluation, and method comparison. Second, even state-of-the-art models struggle to capture fine-grained structural details, often failing to handle fuzzy boundaries and complex damage patterns in real battlefield environments. Third, mechanisms for efficiently incorporating foundation model priors are still immature; existing approaches do not fully leverage the structural cues contained in foundation vision models (e.g., SAM), reducing their potential effectiveness for building damage analysis. Finally, achieving both high accuracy and high efficiency remains challenging: foundation models offer strong representational power but incur high computational cost, whereas lightweight CNN-Mamba architectures improve efficiency but exhibit reduced robustness in highly complex scenes.

To address the above challenges, this paper proposes a novel building damage change detection framework, CMSNet. CMSNet adopts CNN-Mamba as the backbone, leveraging its capability for effective detail and temporal feature modeling to extract multi-scale semantic features from bi-temporal remote sensing imagery. Meanwhile, SAM is introduced as an external structural prior, enhancing intermediate features to guide the model toward building boundaries and damaged regions, thereby improving segmentation accuracy and structural consistency. To fully exploit the potential of foundation models, we design a Pretrained Visual Prior-Guided Feature Fusion Module (PVPF-FM), which aligns and fuses SAM outputs with CNN-Mamba intermediate features, strengthening the model’s ability to detect complex change regions. Moreover, to mitigate the issue of data scarcity, we construct a new high-resolution dataset, RWSBD, based on real war-zone remote sensing imagery from the Gaza Strip. RWSBD covers diverse damage types, large-area scenes, and complex environments, providing a valuable benchmark for building damage change detection in real-world war scenarios.

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of CMSNet, we conducted extensive experiments on four remote sensing change detection datasets: RWSBD, CWBD, WHU-CD, and LEVIR-CD+, and compared it with eight state-of-the-art methods. The results demonstrate that CMSNet consistently outperforms competing approaches across multiple metrics (including F1-score, IoU, Precision, and Recall), showing particular advantages in fine-grained building damage detection with stronger boundary preservation and robustness. In summary, the main contributions of this work are as follows:

- (1)

We propose CMSNet, a building damage change detection framework that integrates the foundation vision model SAM with CNN-Mamba, combining structural prior enhancement with efficient feature modeling.

- (2)

We design a Pretrained Visual Prior-Guided Feature Fusion Module (PVPF-FM) to effectively integrate SAM segmentation priors with backbone feature representations.

- (3)

We construct the RWSBD dataset, providing a high-resolution benchmark of real-world war-zone building damage for remote sensing change detection, supporting future research in this area.

- (4)

We systematically validate CMSNet on four remote sensing datasets, demonstrating superior accuracy and robustness in complex scenarios.

2. Related Work and Problem Statement

Remote sensing-based building damage assessment has undergone a long evolution, forming two major research paradigms: (1) single-temporal image–based classification, and (2) multi-temporal image–based change detection. Early studies primarily relied on single-temporal images, where damage levels were inferred from post-event optical or SAR imagery using handcrafted features such as texture descriptors, spectral indices, morphological profiles, and rule-based classifiers. Although effective in certain structured environments, these methods could not reliably distinguish true structural damage from naturally dark roofs, shadows, debris, or seasonal variations, due to the absence of explicit temporal comparison. With the availability of multi-temporal remote sensing data, the research paradigm gradually shifted toward change detection, where differences between pre- and post-event images provide more discriminative cues for identifying actual structural destruction. This paradigm has proven more robust for disaster scenarios, especially for recognizing collapse, partial roof failure, or severe structural fragmentation.

Driven by deep learning advancements, remote sensing change detection—one of the core tasks in intelligent image interpretation—has made substantial progress in recent years [

24,

25]. In the area of building change detection, researchers have extensively explored backbone feature extraction, temporal interaction mechanisms, multi-scale modeling, and structural prior integration [

24,

25]. Based on backbone modeling strategies, current methods can be broadly divided into four categories: CNN-based methods, Transformer-based methods, Mamba-based methods, and methods integrating foundation models. Despite the improvements contributed by these paradigms, significant challenges remain for detecting damaged buildings in complex war-zone environments characterized by irregular destruction patterns, heterogeneous backgrounds, and fragmented structures.

2.1. CNN-Based Change Detection Methods

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have long been the mainstream modeling framework for remote sensing change detection tasks [

18,

26]. Typical methods such as FC-EF, FC-Siam-Conc, and FC-Siam-diff [

27] employ end-to-end architectures to extract bi-temporal features, discriminate changes, and generate binary masks. CNNs provide strong local perceptual capabilities and can enhance fine details through multi-scale convolutional designs. However, as inherently local feature extractors, they struggle with long-range spatial dependencies, complex damage patterns, and irregular building boundaries [

28]. In real war scenarios, asymmetric destruction, occlusions, and debris-induced texture anomalies are difficult to model with local kernels alone [

29]. CNNs also lack long-term temporal modeling capacities, limiting their ability to distinguish subtle structural damage from background noise. Thus, although simple and stable, CNN-based methods often fail to capture global relationships, making them insufficient for modeling discontinuous and irregular war-zone building changes.

2.2. Transformer-Based Change Detection Methods

Transformers [

30], widely applied in NLP [

31] and image recognition [

32], introduce global attention mechanisms to remote sensing change detection tasks [

20]. Models such as ChangeFormer [

33], BIT [

20], and MATNet [

34] use self-attention to capture long-range contextual cues, alleviating the receptive field limitations of CNNs. This global modeling ability supports the detection of large-scale changes such as massive collapses or structural disintegration [

35]. However, Transformers entail heavy computation, parameter redundancy, and high memory consumption. They also tend to generate blurred change boundaries and exhibit sensitivity to training data volume [

36]. In war-zone imagery with limited high-quality samples, Transformers may overfit or fail to converge effectively [

37]. Although strong in global modeling, their limitations in boundary precision, efficiency, and small-sample robustness hinder their applicability in real war-damage detection tasks.

2.3. Mamba-Based Change Detection Methods

The Mamba architecture [

23] replaces conventional attention with a linear state-space model, enabling efficient long-range dependency modeling with low computation overhead. This makes Mamba an emerging alternative to CNNs and Transformers in vision modeling. Mamba-based change detection approaches such as Change-Mamba [

38], CDMamba [

39], and M-CD [

40] have shown significant advantages in accuracy and efficiency, drawing increasing attention within the remote sensing community. However, Mamba’s adaptation to remote sensing imagery remains limited [

41]. Current methods often neglect shallow edges and fine texture details, leading to inaccuracies in scenarios involving irregular building boundaries. Most architectures rely on shallow temporal difference modules, lacking deeper bi-temporal interaction strategies. For building damage detection—where changes can be fragmented, subtle, or boundary-focused—the ability of Mamba to model evolving spatiotemporal features remains insufficiently validated. Existing designs are largely generic and not optimized for paired bi-temporal remote sensing images. While theoretically promising, Mamba-based change detection is still in its early stages and lacks task-specific structural optimization.

2.4. Foundation Model-Based Change Detection Methods

Foundation vision models such as SAM [

21], CLIP [

42], and DINO [

43] have demonstrated remarkable generalization ability. Among them, SAM shows strong competence in boundary perception, occlusion handling, and structural delineation, making it particularly attractive for remote sensing segmentation tasks. Existing attempts—such as RemoteSAM [

22], SAM3D [

44], and SCD-SAM [

45]—have explored using SAM in building extraction or semantic interpretation tasks. However, effectively integrating SAM’s structural priors into change detection remains challenging. SAM lacks temporal awareness and may introduce noise if its structural priors are fused improperly. Additionally, SAM’s natural-image pretraining limits its adaptation to scale variations and complex backgrounds in remote sensing [

22,

46]. Key open problems include robust fusion of SAM priors with bi-temporal features, handling semantic shifts, and adapting SAM to irregular building damage structures. While foundation models introduce new opportunities for structural prior integration, substantial modeling challenges remain.

To address these challenges, this paper proposes a novel method—CMSNet—which combines the efficient feature modeling capability of CNN-Mamba with the structural awareness of the SAM foundation model. We design a Pretrained Visual Prior-Guided Feature Fusion Module (PVPF-FM) to enhance structural representation in damage regions. We also construct RWSBD, a real-world war-zone building damage dataset, providing a critical benchmark for the field. CMSNet achieves breakthroughs in structural perception, boundary precision, temporal modeling, and foundation-model-guided fusion, leveraging complementary strengths across modeling paradigms and exploring new strategies for remote sensing building damage change detection.

3. The Dataset of Real War Scenes

To support in-depth research on building damage detection in real war-zone remote sensing imagery, this paper constructs a remote sensing change detection dataset for real war scenarios—RWSBD.

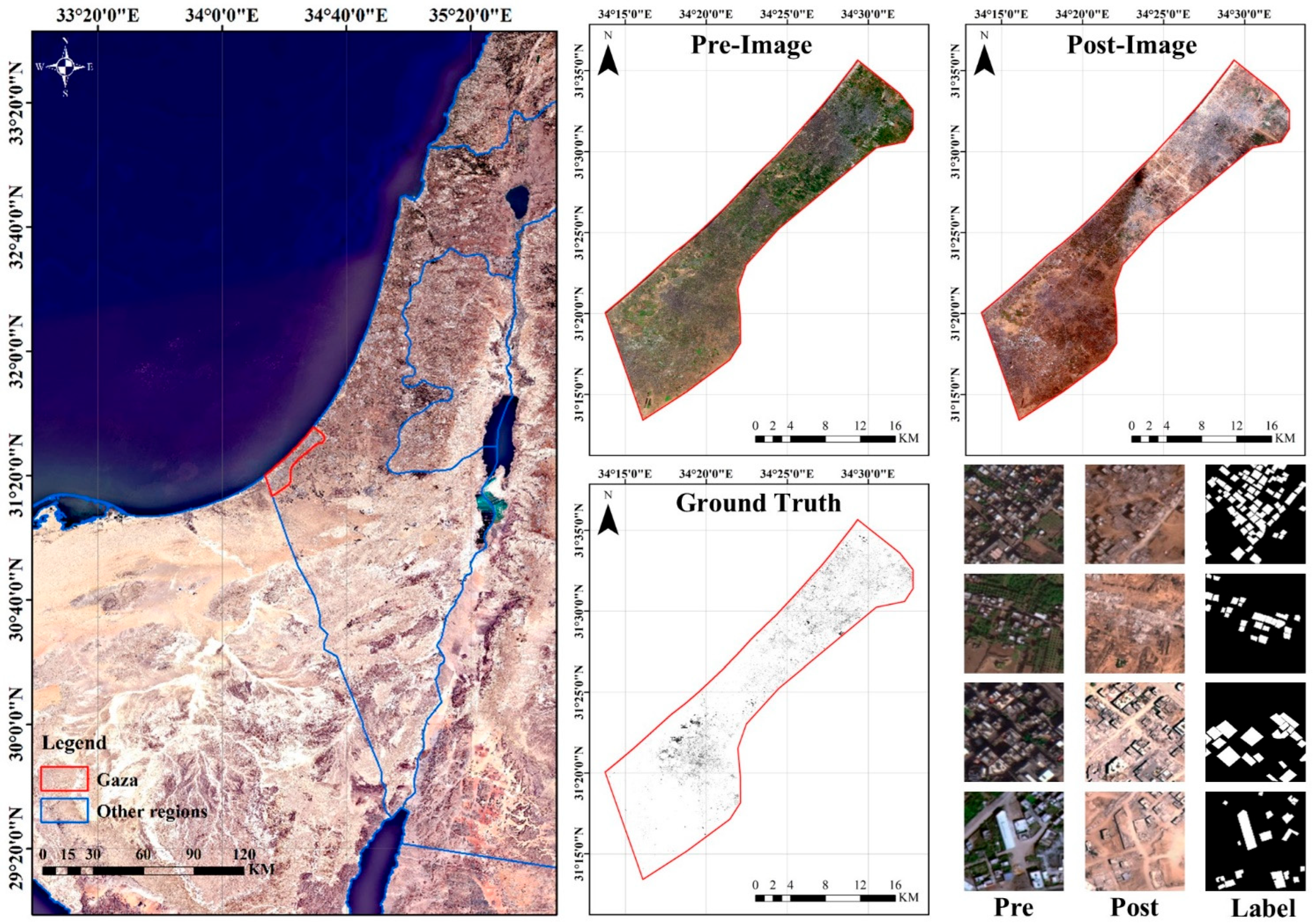

The dataset is based on high-resolution optical imagery and a rigorous manual annotation process, covering typical damage patterns in real war-affected areas, making it highly practical and valuable for research (see

Figure 1). RWSBD consists of two high-resolution images of the Gaza Strip acquired by the GF-2 optical remote sensing satellite, captured on 24 September 2022 (pre-conflict) and 3 May 2024 (post-conflict), with a spatial resolution of 0.8 m. The geographic coverage spans the entire Gaza Strip, including urban, suburban, and densely built-up areas. To ensure alignment, the pre- and post-conflict images were carefully registered using feature-based image registration techniques, with key points matched and refined through local affine transformations. Accuracy control was conducted via visual inspection and cross-verification with high-resolution reference data to ensure spatial consistency and annotation reliability. These images effectively capture building structural details and local damage characteristics, providing a high-quality visual foundation for subsequent building damage recognition and change analysis.

During dataset construction, a manual, building-by-building annotation approach was employed to precisely label damaged buildings in the post-conflict images. Annotations were performed by remote sensing professionals with interpretation experience, focusing on severe war damage features such as roof collapse and total building collapse. In total, 42,723 damaged building instances were annotated, covering diverse scenarios including urban and suburban areas, fully reflecting the variety and complexity of war-zone building damage. To meet the training requirements of deep learning models, the pre- and post-conflict images along with their corresponding annotations were uniformly cropped into 256 × 256-pixel patches. Through cropping and filtering, 28,210 image pairs with aligned and accurately labeled masks were obtained. These samples are representative and discriminative, serving as a high-quality training set for high-resolution war-zone building damage change detection. The construction of the RWSBD dataset not only fills the gap of high-resolution remote sensing datasets for building damage detection in real war scenarios but also provides a solid benchmark for model training, evaluation, and transfer learning in subsequent research.

During annotation, partially damaged buildings were labeled by marking only the visually confirmed damaged portions rather than the entire building footprint, ensuring precise localization of destruction. Since this study focuses on binary damaged/undamaged identification, we did not assign multi-level damage categories, as doing so requires additional standardized criteria and expert consensus; such severity-level annotations will be considered in future extensions of the dataset. Moreover, buildings that were naturally demolished, renovated, or newly constructed between the two temporal images were not included, in order to avoid semantic ambiguity and ensure that the dataset strictly reflects war-induced structural damage.

4. Methodology

4.1. CMSNet Overall Architecture

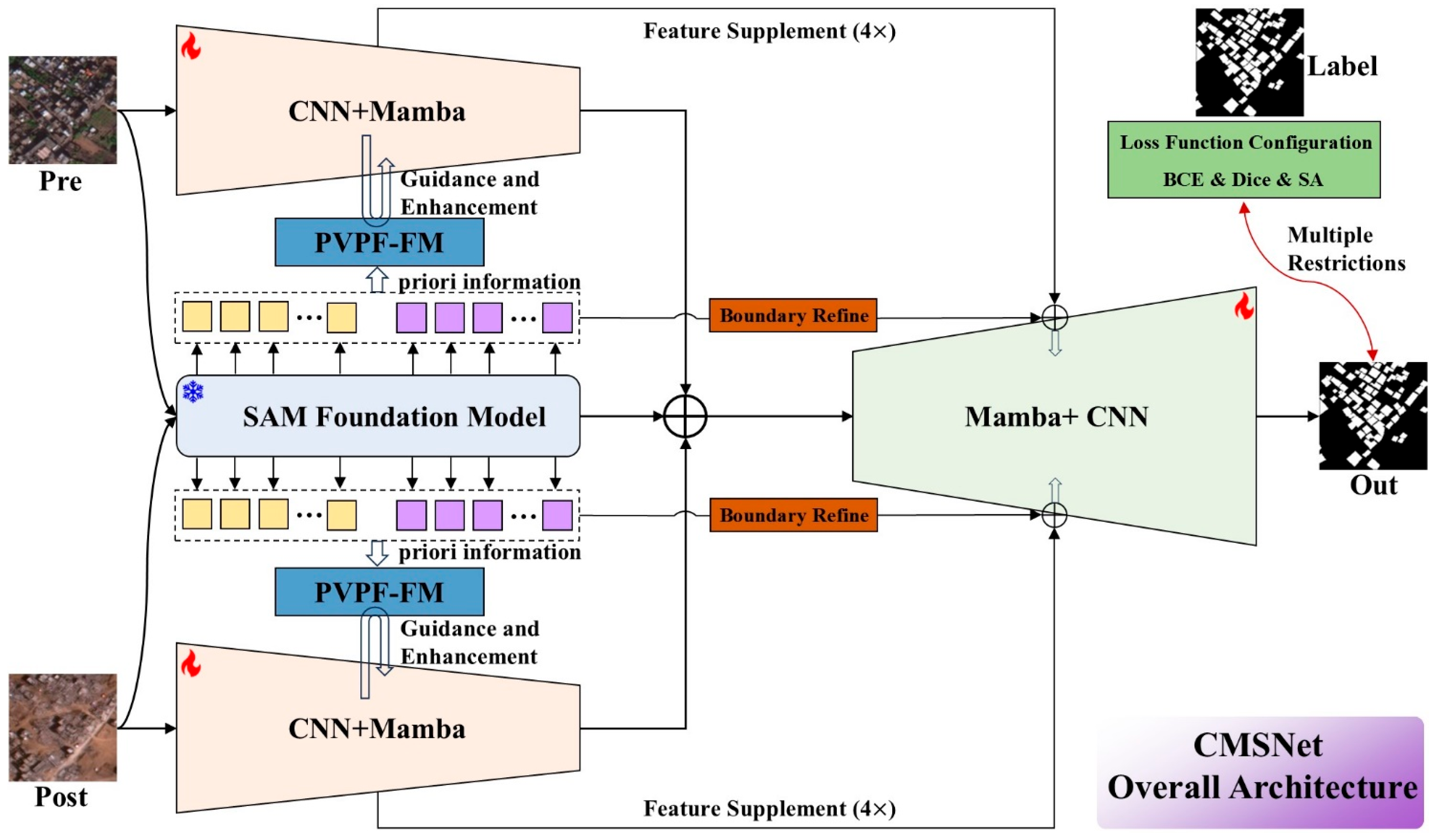

The CMSNet architecture adopts an encode–fuse–decode design, aiming to simultaneously enhance structural awareness of damaged targets and the modeling of change features. The main network is built with a CNN-Mamba hybrid structure, enabling synergistic modeling of local texture details and global temporal dependencies. In addition, a structural prior awareness path is incorporated: building structure masks extracted by the pretrained SAM foundation model serve as guidance, further enhancing the network’s ability to capture building boundaries and morphological changes, enabling precise extraction of fine-grained damaged building regions (see

Figure 2). CMSNet employs a dual-stream parameter-sharing structure to process pre- and post-conflict images. Each stream consists of a shallow CNN module and a deep Mamba module. The CNN extracts low-level local features, such as edges and textures, while Mamba—a structured state-space model—captures long-range dependencies and temporal differences, effectively modeling global semantic changes across time. This combination preserves edge details while providing awareness of large-scale semantic variations. To further enhance structural understanding, CMSNet introduces the SAM structural prior path alongside the backbone. Pre- and post-conflict images are input into a frozen SAM to extract multi-level structural mask features, which are then deeply integrated with backbone semantic features via the Pretrained Visual Prior-Guided Feature Fusion Module (PVPF-FM) during intermediate fusion. This module employs channel and spatial attention mechanisms to dynamically adjust the fusion weights between SAM masks and CNN-Mamba features, improving discrimination in cases of blurred boundaries, minor damage, or dense destruction. SAM remains frozen during training, serving solely as a source of structural priors to provide building integrity constraints. The decoding process uses a multi-scale decoder fusion structure that progressively upsamples and integrates features from both the encoder and SAM branch. A boundary refinement channel further enhances the recovery quality of building edges. The final output is a pixel-level damage mask from the change prediction head, ensuring fine boundaries, clear regional structures, and minimal local errors. Throughout decoding, spatial details from CNN, semantic changes from Mamba, and structural guidance from SAM are synergistically maintained. To jointly optimize pixel-level accuracy, structural consistency, and boundary fidelity, CMSNet employs a multi-component loss system. The base loss uses binary cross-entropy (BCE) to supervise overall damage segmentation, combined with Dice loss to address class imbalance and instability in small target regions. A Structure Alignment Loss is introduced to constrain consistency between SAM-guided features and actual change features, improving structural prediction stability. The total loss is a weighted combination of these components, ensuring synergistic coordination among feature guidance, boundary restoration, and change perception during training.

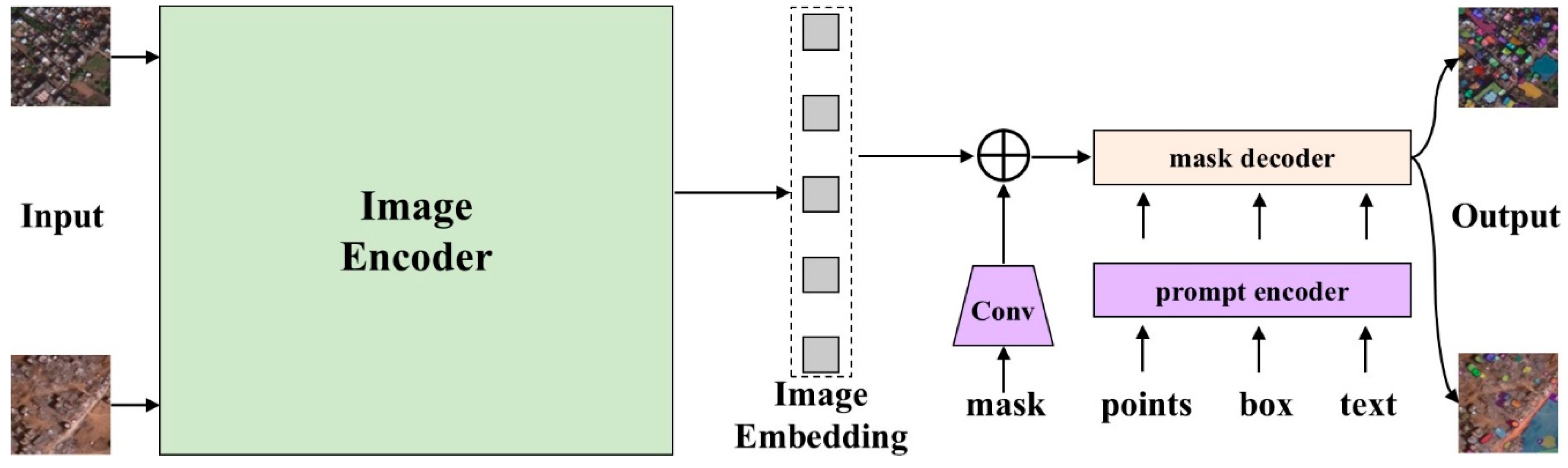

4.2. Overview of the SAM Foundational Model

SAM, released by Meta AI in 2023, is a pretrained foundation model with broad visual perception and segmentation capabilities. It provides a general-purpose image segmentation framework with strong zero-shot segmentation ability, enabling mask prediction for any object or region in an image without relying on task-specific downstream training. The core idea of SAM is to unify image segmentation as a “prompt-to-mask” problem, where different types of input prompts—points, boxes, or text—are used to predict high-quality masks for the corresponding regions in the image. This makes SAM widely adaptable across multiple domains, including natural images, medical imaging, and remote sensing, and allows it to serve as a structural prior model embedded within more complex recognition systems. SAM’s overall architecture consists of three key modules: an image encoder, a prompt encoder, and a mask decoder. The image encoder uses a Vision Transformer (ViT) to embed the input image into high-dimensional representations, forming a global visual feature tensor. The prompt encoder embeds user-provided prompts—points, boxes, or semantic vectors—into the same feature space. The mask decoder employs a lightweight Transformer architecture to fuse the image features with the prompt embeddings, and uses a multi-head attention mechanism to predict the mask regions corresponding to the prompts. The basic processing workflow can be formally described as follows:

Image embedding generation step: Generate a high-dimensional feature representation based on ViT from an input image

of size

:

where

denotes the input image,

represents the image encoder, and

denotes the resulting high-dimensional feature.

In the prompt vector embedding step, embedding vectors are generated based on the provided prompt inputs:

where

represents the input prompt, which can be in the form of points, bounding boxes, or text, and

denotes the output embedding vector in the same feature space as the image features.

In the mask prediction step, the mask output is decoded based on the high-dimensional image features

and the prompt embedding vectors

:

where

represents the mask decoder,

denotes the predicted mask, and

.

Through the above process, the SAM acquires the ability to parse structural regions from arbitrary visual prompts. Its mask outputs typically exhibit high boundary quality and structural integrity, making them particularly suitable as structural prior inputs for tasks in the remote sensing domain, such as building recognition and damage detection. In this study, we freeze the SAM and use only the building structure masks generated from pre- and post-event remote sensing images as prior features to guide the backbone network, enabling more accurate focus on damaged regions and improving the completeness of damage boundaries and semantic consistency (see

Figure 3).

In our implementation, the SAM encoder is kept frozen during CMSNet training. The pretrained SAM extracts high-level structural mask features from the input images, which serve as external visual priors to guide the network’s focus on building boundaries and potential structural changes. No fine-tuning is applied to SAM’s weights, ensuring that the foundation model’s structural knowledge is preserved and consistently integrated into the PVPF-FM module. Only the downstream CNN-Mamba backbone and fusion layers are updated during training, which maintains experimental reproducibility and stability across different datasets. This design allows CMSNet to leverage SAM’s global structural awareness without incurring additional computational overhead or risking overfitting to the training data.

4.3. CNN-Mamba Encoder–Decoder Architecture

In remote sensing building damage change detection, building structures are often complex and diverse, with changes ranging from severe structural collapse to roof damage. These changes typically involve multi-scale spatial information, long-range dependencies, temporal semantic shifts, and blurred edge details. Traditional CNN-based networks perform well in extracting local features but are limited by their receptive field and lack of global modeling capability, making it difficult to capture cross-scale and large-area semantic changes. Transformer-based architectures, while providing global perception, incur high computational costs and are less sensitive to boundaries, rendering them less suitable for large-scale, high-resolution remote sensing scenarios. To address these challenges, this study proposes an effective integration of CNN with the state-space modeling architecture Mamba, forming a powerful CNN-Mamba encoder–decoder backbone network that enables precise perception and reconstruction of multi-scale, multi-temporal building changes.

The backbone of CMSNet follows a symmetrical dual-stream encoder–decoder architecture, processing input pairs of pre- and post-event remote sensing images

. Each stream is composed of four stacked CNN-Mamba blocks, forming multi-scale semantic representations. The final change mask is reconstructed through cross-stream difference modeling and feature fusion. In this architecture, CNN-extracted edge details are combined with Mamba-learned global temporal change patterns, enabling local-global collaborative perception: shallow layers focus on structural details, while deeper layers capture semantic and spatial dependencies. The decoder integrates multi-scale features from the encoding stage to reconstruct high-precision damage masks. The encoder employs a hierarchical design, with each layer containing a CNN-Mamba block that includes convolutional feature extraction, downsampling, state-space modeling, and residual connections. Within each block, standard convolution is first applied to extract local spatial features, preserving fine details such as boundary shapes, building contours, and texture variations:

where

denotes the output from the previous layer, and

represents the output of the convolutional branch at the current layer. In this work, standard ResNet modules are employed to construct the shallow feature representations.

The Mamba module unfolds spatial features along rows or columns and employs a state-space modeling mechanism to capture long-range contextual dependencies and global temporal dynamics. Unlike Transformers, Mamba has linear time complexity

, making it suitable for large-scale image inputs. Its fundamental unit can be expressed as:

where

denotes the sequence of convolutional feature vectors,

represents the hidden state,

is the output feature representation, and A, B, C, and D are learnable parameters.

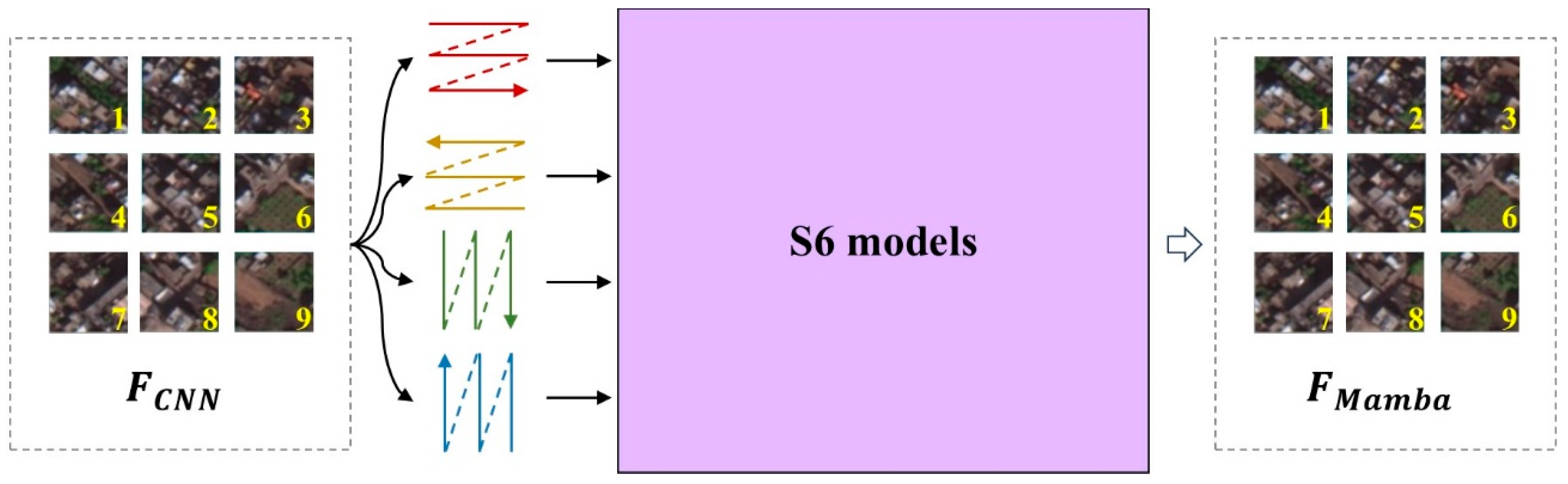

As shown in

Figure 4, at the image level, this can be understood as splitting the 2D feature tensor

along the H and W dimensions into sequences, processing them through the Mamba module, and then reassembling them into a 2D feature map

.

Finally, the outputs of the CNN and Mamba branches are fused. In this step, Mamba efficiently models spatiotemporal change patterns through multi-dimensional temporal dependency modeling, showing strong responsiveness to long-term changes such as roof collapses or complete building destruction. The CNN branch excels at preserving boundary clarity, particularly for detecting edges of medium-scale damage in remote sensing images, maintaining fine-grained details. By combining the two, global–local joint optimization is achieved, and residual fusion ensures semantic consistency while avoiding distortion in global modeling. Moreover, Mamba’s linear computational complexity and parallelizable structure allow the model to maintain high efficiency without sacrificing performance. The feature fusion process between CNN and Mamba is computed as follows:

where

is a learnable weighting coefficient used to balance the contributions of the CNN and Mamba features. The fused features retain fine spatial details while incorporating global modeling capabilities.

In CMSNet, the decoder restores spatial resolution in a top-down, multi-scale manner, integrating outputs from each encoder layer via skip connections. Corresponding SAM feature masks are also incorporated at each decoding stage, fusing with existing features to improve boundary mapping accuracy during mask reconstruction. The decoder employs a structure combining VSS modules with learnable transposed convolutions. This design not only restores spatial information from compressed features but also preserves long-range dependencies and semantic consistency, making it especially suitable for reconstructing complex, edge-blurred damaged regions in remote sensing images. Each decoding unit performs progressive upsampling, aggregation, and reconstruction of change regions, which can be formally expressed as:

where

denotes the VSS module at layer

,

represents the transposed convolution upsampling operation, and

refers to the skip-connection fusion and subsequent processing at that layer.

The VSS module in the decoding stage focuses on modeling structural consistency and semantic alignment across multi-scale change regions during feature reconstruction. Its processing flow involves unfolding the current feature map into sequences, applying state-space modeling to capture structural dependencies across pixels, and reconstructing the image. This module enhances the preservation of spatial structures during decoding, ensuring that building change regions remain coherent when upsampled, particularly for fractured edges or collapsed areas.

It is important to clarify that SAM is not employed as a feature extraction backbone or a temporal modeling module in our method. Instead, SAM is used only once to generate structural priors that provide coarse building masks and boundary cues. These priors are lightweight to obtain, do not introduce Transformer-based computational burdens during training or inference, and are fused into the CNN–Mamba feature space solely for structural enhancement. Therefore, the integration of SAM does not contradict the limitations of Transformer architectures discussed earlier; rather, it complements the proposed model by supplying high-quality structural guidance without affecting the overall efficiency and boundary modeling capability of the CNN–Mamba backbone.

4.4. Feature Enhancement Mechanisms of Foundation Model

This section focuses on the structural principles and workflow of the PVPF-FM module, a feature enhancement component in CMSNet built on top of foundation vision models. Serving as a bridge between a pretrained foundation model and the backbone change detection network, this module fully leverages the structural and boundary priors encoded in foundation models to improve the perception and alignment of building structures and damaged regions. Although the CNN-Mamba backbone network exhibits strong local-global feature fusion capabilities, it may still encounter challenges such as false positives, missed detections, or blurred boundaries when processing remote sensing images with dense buildings, complex change patterns, and indistinct edges. To address this, we introduce structural prior information from a universal foundation model such as SAM to guide the backbone network in focusing on critical regions and enhancing its structural awareness of building targets.

The core idea of the PVPF-FM module is to incorporate the structural mask features generated by SAM into the change detection process, thereby guiding the backbone network to enhance the structural consistency, boundary integrity, and semantic clarity of damaged regions during the mid-to-high-level feature representation stage. As shown in

Figure 5, the module consists of four subcomponents: the mask embedding encoder, which transforms the structural masks into high-dimensional guidance features; the temporal guidance fusion module, which performs guided fusion separately for pre- and post-event features; the feature difference enhancement module, which strengthens responses in change regions by leveraging differences in SAM masks; and the feature fusion output module, which outputs structure-aware enhanced feature maps for further decoding. Specifically,

and

denote the pre- and post-event image features extracted by the backbone encoder, while

and

represent the building structure masks generated by SAM for the corresponding images. The binary SAM mask

is first passed through multiple convolutional layers to obtain a guidance feature map

, which encodes spatial boundary and structural contour information of buildings.

where

denotes the convolutional feature transformation block, which consists of a standard convolution (Conv), batch normalization (BN), and a ReLU activation function.

Based on

, feature fusion is performed separately with

and

to enable the features from the foundation visual model to be deeply integrated with the backbone features. In this work, a residual-enhanced fusion strategy is adopted, and the computation can be expressed as follows:

where

denotes the operation of dimension reduction and attention-based fusion applied after feature concatenation using a 1

1 convolution, while

represents a learnable coefficient.

After obtaining the features enhanced by the foundation visual model, the difference between the pre- and post-event structural masks is computed to guide the network’s focus toward the damaged regions. The difference feature is calculated as follows:

Finally, the difference mask guidance map is embedded into the feature space and applied to the enhanced backbone features, thereby combining the “structural location prior” with “temporal semantic differences” to improve the model’s ability to focus on key regions (damaged building areas) for change recognition. The feature embedding process is defined as follows:

The output of PVPF-FM is a structure-aware enhanced bi-temporal fused feature, whose dimensionality is consistent with that of the backbone features and can be directly fed into the decoder for change region reconstruction. In this process, strong structural priors, guided by SAM mask information, direct the model to focus on building areas, thereby improving the recognition of small-scale damage. Meanwhile, boundary enhancement helps address issues of blurred boundaries and misclassification in change regions. In addition, PVPF-FM can be flexibly inserted as a module into feature layers of different scales, demonstrating good compatibility. Furthermore, knowledge transfer from the SAM foundation model enhances the model’s stability under small- and medium-scale sample conditions.

4.5. Loss Function Configuration

To effectively improve the detection accuracy of building damage areas by CMSNet in real remote sensing war-damage scenarios, we design a multi-objective optimization strategy composed of three complementary loss functions, which jointly consider pixel-level classification accuracy, regional integrity, and structural prior consistency. In this strategy, the basic loss supervises the accuracy of mask prediction, while the structure-guided loss further enhances the model’s focus on building regions. The overall loss function is defined as follows:

where

,

, and

denote the weighting coefficients of the respective loss functions. In this work, we set

,

and

.

Among them, the BCE loss is the most commonly used pixel-wise binary classification loss function, which measures the per-pixel discrepancy between the predicted mask and the ground truth damage labels, and is defined as follows:

where

represents the predicted damage probability for the i-th pixel,

is the corresponding ground truth label, and

denotes the total number of pixels.

Dice serving as a complementary region-level supervision, helps improve the detection of small targets and sparse change areas. It emphasizes the overlap between the predicted region and the ground truth, making it suitable for evaluating segmentation quality. It is defined as follows:

where

denotes a small constant term.

Considering that CMSNet incorporates structural masks provided by SAM as auxiliary supervision, we design a Structure-Guided Loss to direct the model’s attention toward actual building regions, thereby improving the spatial plausibility and structural alignment of the predicted masks. It is defined as follows:

where

denotes the building region mask extracted by SAM, serving as a weak supervisory signal during training, particularly useful in cases of incomplete annotations or severe occlusions. This loss encourages the model to focus on the main building areas during change detection, thereby reducing the risk of false positives in the background.

5. Experiments and Analysis

5.1. Dataset Details

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of CMSNet in multi-scenario building damage detection tasks, experiments were conducted on four representative datasets, covering various types such as real-world war zones and typical urban changes. These four datasets are RWSBD, CWBD, WHU-CD, and LEVIR-CD+, with the following specific details:

RWSBD is a high-resolution remote sensing building damage change detection dataset independently constructed in this study, specifically designed for real-world war scenarios, with strong practical applicability and research value. The dataset is based on two GF-2 satellite optical images with a spatial resolution of 0.8 m, acquired on 24 September 2022, and 3 May 2024, respectively, covering the entire Gaza Strip. Building damage regions in the bi-temporal images were manually annotated, resulting in a total of 42,723 damaged building instances. During preprocessing, all images and labels were cropped into 256 × 256-pixel patches, forming 28,210 paired image samples along with their corresponding mask labels.

The CWBD dataset [

6] focuses on building damage scenarios caused by war, explosions, and conflicts. Its remote sensing images are sourced from multiple times, locations, and sensors, featuring a higher spatial resolution of 0.3 m, which allows for capturing finer damage details. The CWBD dataset contains a total of 4065 pairs of pre- and post-event image samples, each consisting of a 256 × 256-pixel bi-temporal image pair and the corresponding damage mask. The dataset exhibits significant diversity in damaged building regions, posing greater challenges to the accuracy and robustness of change detection algorithms.

WHU-CD [

47] is a high-quality remote sensing dataset focused on post-earthquake building reconstruction and change detection. The dataset covers an area affected by a 6.3-magnitude earthquake in February 2011, along with the reconstruction progress from 2012 to 2016. It contains high-resolution aerial imagery with significant building changes. After cropping, the images are divided into 256 × 256-pixel patches, with a spatial resolution of approximately 0.2 m. WHU-CD provides high-quality bi-temporal remote sensing images and precise change annotations, making it widely used for developing and evaluating various change detection methods, particularly suitable for binary building change detection tasks.

The LEVIR-CD+ dataset [

48] is specifically designed for urban-scale remote sensing building change detection tasks. It covers multiple urban scenarios and includes various types of building changes, such as expansions, new constructions, and demolitions. The dataset contains 985 pairs of high-resolution image samples, each with a size of 1024 × 1024 pixels and a spatial resolution of 0.5 m. Each sample pair includes a pre-change image, a post-change image, and a change annotation map. Overall, the dataset encompasses approximately 80,000 building change instances, offering high sample density and diversity. With improvements in image resolution, change density, and annotation precision, LEVIR-CD+ has become one of the widely used benchmark datasets in the field of remote sensing building change detection.

5.2. Experimental Implementations

All experiments in this study were conducted on a high-performance server equipped with an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 GPU (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with 24 GB of memory, running Ubuntu 20.04. The deep learning framework used was PyTorch (version 12.2). During model training, the batch size was set to 6, with a total of 100 training epochs. The Adam optimizer was employed, initialized with a learning rate of 1

and dynamically adjusted based on validation performance. The loss function followed the combined strategy defined in

Section 4.5 (BCE, Dice, and SAM-guided loss) to enhance pixel-wise classification accuracy, region integrity, and structural consistency. All input images were cropped to 256 × 256 pixels, and standard data augmentation techniques, including random flipping, slight rotation, and color perturbation, were applied during training to improve model generalization and robustness. This consistent experimental setup provided a reliable foundation for the stable training of CMSNet and for performance comparisons across multiple remote sensing change detection datasets.

5.3. Evaluation Methods and Metrics

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of CMSNet in detecting building damage changes from remote sensing images, this study selected eight representative mainstream change detection methods as baselines and employed four commonly used quantitative metrics for performance comparison and analysis. These baseline methods span different network architecture paradigms, including CNN, Transformer, and Mamba, as well as diverse encoding strategies, allowing a thorough assessment of CMSNet’s effectiveness and robustness from multiple perspectives. Specifically, the eight methods cover mainstream CNN architectures, Siamese network structures, Transformer-based models, and the latest Mamba state-space modeling paradigm, enabling comparison of CMSNet’s change modeling capabilities across different modeling levels. The details are described as follows:

ChangeMamba [

38]: A change detection method based on spatiotemporal state-space modeling, which uses the Mamba structure to model pre- and post-event images and capture long-range dependencies. It is one of the recently proposed efficient change detection models.

RS-Mamba [

49]: An improved Mamba network optimized for remote sensing scenarios, enhancing feature extraction capability for high-resolution images and providing better spatial modeling performance.

ChangeFormer [

33]: A typical Transformer-based change detection method that introduces cross-temporal feature interaction and global modeling capability, suitable for detecting complex structures and long-range changes.

SNUNet: A symmetric multi-scale nested U-Net network that fuses semantic features across scales to improve change region detection accuracy, demonstrating strong local detail modeling capability.

IFN [

49]: A CNN-based network incorporating pre- and post-event interaction mechanisms, enhancing the model’s responsiveness to change features through explicit information exchange.

FC-Siam-diff [

50]: Similar to FC-Siam-conc but models feature differences explicitly, emphasizing changes between pre- and post-event features and focusing on fine-grained differences.

FC-Siam-conc [

50]: A classical fully convolutional Siamese network that fuses pre- and post-event features through concatenation, directly modeling differences between the two images.

FC-EF [

50]: An early-fusion change detection network that merges pre- and post-event images at the input stage, focusing on extracting overall temporal difference features.

To objectively evaluate the performance of these methods in building damage change detection, this study employs four standard metrics: F1-score (F1), Intersection over Union (IoU), Precision (P), and Recall (R). All metrics are computed based on pixel-level predictions against ground truth labels. The calculation formulas are as follows:

where TP represents true positives, FP represents false positives, and FN represents false negatives. P indicates the proportion of predicted change regions that are actually true changes; a high precision means fewer false alarms and misclassified areas. R reflects the proportion of actual change regions successfully detected by the model; a high recall indicates fewer missed detections and more comprehensive identification of true changes. IoU measures the overlap between predicted and ground-truth change regions, with higher values indicating closer alignment between the predicted and true masks. F1-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, representing a balanced evaluation of the model’s overall performance; higher F1 values indicate better trade-off between precision and recall.

5.4. Benchmark Comparison

In this section, we conduct a systematic comparison between the proposed method and several baseline models on the RWSBD, CWBD, WHU-CD, and LEVIR-CD+ datasets. To provide an intuitive understanding of the prediction performance,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 present visualization results of representative examples, with three typical instances selected from each dataset for a clear comparison of predictions across different methods. Meanwhile,

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4 summarize the quantitative evaluation results, covering P, R, F1, and IoU. These results together enable a comprehensive analysis of the strengths and weaknesses of different approaches across diverse datasets.

Before presenting the comparative results, we briefly summarize the key characteristics of the eight state-of-the-art methods evaluated in this study. FC-EF, FC-Siam-conc, and FC-Siam-diff are classical CNN-based Siamese networks, focusing on local feature extraction and multi-scale convolutional representation. IFN and SNUNet are advanced CNN-based architectures with enhanced feature fusion and attention mechanisms, aiming to improve change detection accuracy in complex scenarios. ChangeFormer is a Transformer-based model that leverages global attention to capture long-range dependencies and contextual information. RS-Mamba and ChangeMamba are Mamba-based methods that employ linear state-space modeling to efficiently capture temporal dependencies and structural changes in bi-temporal images. These methods cover a wide range of paradigms, from purely CNN-based to Transformer- and Mamba-based architectures, providing a comprehensive benchmark for evaluating the performance and generalization capabilities of CMSNet.

From the prediction results shown in

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9, it is evident that the detection accuracy and robustness of different models vary significantly across the four datasets. The earlier FC-series models (FC-EF, FC-Siam-conc, FC-Siam-diff) often suffer from blurred boundaries and misdetections in complex scenarios, performing poorly especially when building structures are intricate or exhibit large scale variations. In contrast, Transformer- and Mamba-based models (e.g., ChangeFormer, RS-Mamba, ChangeMamba) achieve superior performance in maintaining boundary continuity and suppressing false changes, with predictions that are closer to the ground truth. Notably, CMSNet produces more complete change regions with sharper boundaries across multiple datasets, demonstrating strong cross-scene generalization capability. In the sample visualizations, CMSNet and ChangeMamba deliver the most outstanding results: both are able to capture small-scale targets while effectively distinguishing adjacent building clusters, thereby reducing missed detections and over-merged predictions. RS-Mamba also shows relatively stable performance, though slight boundary breaks are still observed in certain areas. By comparison, SNUNet generates coarser predictions, struggling to delineate fine structural details. These results indicate that network architectures incorporating sequence modeling and long-range dependency mechanisms achieve stronger representational power. Such enhancements also improve the models’ adaptability to complex change scenarios.

From the quantitative results shown in

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4, it can be observed that the traditional FC-series models generally lag behind the more recent approaches across all four datasets. For example, on the RWSBD dataset, the F1 scores of FC-EF, FC-Siam-conc, and FC-Siam-diff remain around 80%, while IFN, ChangeFormer, and ChangeMamba achieve a better balance between IoU and F1. Notably, CMSNet achieves an F1 score of 82.60% and an IoU of 73.13% on RWSBD, ranking as the best among all models. On the CWBD dataset, RS-Mamba and CMSNet demonstrate particularly outstanding performance, with F1 scores of 87.26% and 87.54% and IoU values of 78.77% and 79.04%, respectively, clearly surpassing other models. On the large-scale WHU-CD and LEVIR-CD+ datasets, the performance gap becomes even more pronounced. Taking WHU-CD as an example, CMSNet achieves an F1 score of 96.50%, significantly outperforming other models and highlighting its robustness and accuracy in large-scale scenarios; ChangeMamba also delivers nearly optimal performance, with an F1 score of 95.71%. On LEVIR-CD+, both CMSNet and ChangeMamba remain leading, with F1 scores of 94.72% and 94.64%, respectively, and IoU values exceeding 90%. Overall, the Mamba series and CMSNet consistently achieve stable and superior performance across different datasets, demonstrating their strong generalization ability and application potential in building change detection.

From the experimental results, it can be observed that CMSNet exhibits higher sensitivity to damaged buildings and can effectively distinguish between destroyed and intact areas, which is particularly evident in complex backgrounds and multi-scale scenarios. The performance gains mainly stem from the network architecture and the synergistic effect of its key components. On one hand, the SAM highlights salient features of damaged regions and suppresses background interference, thereby enhancing the model’s local discriminative power. On the other hand, the PVPF-FM module enables deep interaction with backbone semantic features, effectively integrating multi-level information and improving the delineation of building boundaries and subtle damage details. In addition, the overall network design ensures sufficient multi-scale feature representation, allowing CMSNet to adapt well to both small-scale damage instances and large-scale destruction scenarios. Collectively, the modules complement each other at different levels, jointly enhancing the model’s sensitivity and discriminative capacity for damaged buildings, thus providing strong support for final detection performance. At the architectural level, CMSNet adopts a hierarchical feature extraction and fusion strategy, balancing local and global information. This not only guarantees accurate detection of small-scale damage but also maintains high adaptability to widespread destruction. Meanwhile, the structure is designed to balance efficiency and representational power, enabling high-quality modeling of complex disaster scenarios under relatively low computational complexity. In summary, the modular architecture and hierarchical design of CMSNet act in concert to establish its significant advantages in building damage detection tasks.

A quantitative analysis of relative performance improvements highlights the advantages of CMSNet over existing methods. On the RWSBD dataset, CMSNet achieves an F1 score of 82.60%, outperforming the best baseline (ChangeMamba, 80.71%) by 1.89%, and an IoU of 73.13%, which is 1.92% higher than the best baseline (ChangeMamba, 71.21%). On the CWBD dataset, CMSNet improves the F1 score to 87.54%, surpassing the best baseline (RS-Mamba, 87.26%) by 0.28%, and the IoU to 79.04%, exceeding the best baseline (RS-Mamba, 78.77%) by 0.27%. For the WHU-CD dataset, CMSNet achieves the highest F1 score of 96.50%, which is 0.79% higher than the best baseline (IFN, 95.71%), although its IoU is slightly lower than the top baseline (IFN, 92.28%). On the LEVIR-CD+ dataset, CMSNet attains an F1 of 94.72%, surpassing the best baseline (ChangeMamba, 94.64%) by 0.08%, and an IoU of 90.27%, slightly exceeding the best baseline (ChangeMamba, 90.12%) by 0.15%. These results clearly demonstrate that CMSNet consistently improves both F1 and IoU across multiple datasets, confirming its effectiveness in capturing fine-grained building damage and maintaining boundary consistency, as well as its generalization ability across diverse war-zone and urban scenarios.

5.5. Ablation Study

To further verify the effectiveness of the PVPF-FM module in enhancing the overall performance of the model, ablation experiments were conducted in this section. To ensure a comprehensive and fair evaluation of the proposed network design, all ablation models were constructed based on the full CMSNet architecture and were trained and tested on all four datasets used in this study, including RWSBD, CWBD, WHU-CD, and LEVIR-CD+. Since the PVPF-FM module functions in both the encoder and decoder stages of the network, we designed three ablation settings: removing the PVPF-FM module from the encoder (del-e), removing it from the decoder (del-d), and removing it from both the encoder and decoder (del-e&d). These three settings correspond to three different ablation models. To ensure fairness, all models were retrained under the same configurations and datasets as the baseline experiments, followed by a comprehensive comparative evaluation.

From the visual results shown in

Figure 10, it can be observed that removing the PVPF-FM module significantly weakens the model’s performance in boundary delineation and fine-grained region detection. Specifically, the del-e model, which removes the encoder interaction branch, tends to produce incomplete target regions in complex backgrounds, while the del-d model, which removes the decoder interaction branch, yields relatively blurry predictions along boundaries. The del-e&d model, with both branches removed, performs the worst, exhibiting a noticeable increase in missed detections and false alarms in damaged regions. In contrast, CMSNet with the complete PVPF-FM module achieves more accurate and consistent results across all regions.

The bar charts in

Figure 11 quantitatively validate these observations. Across all four evaluation metrics (Precision, Recall, F1, and IoU), removing the PVPF-FM module leads to performance degradation. While del-e and del-d show moderate declines, del-e&d results in a substantial drop, particularly in IoU and F1. This pattern reflects the varying roles of encoder and decoder interactions: encoder-side interaction establishes cross-scale semantic associations at shallow layers, strongly influencing global feature coherence and completeness; decoder-side interaction mainly contributes to detail refinement and structural recovery. Removing both interactions simultaneously impairs global modeling and local detail enhancement, resulting in the poorest performance. Overall, these results highlight the critical importance of dual-stage interaction in CMSNet and demonstrate the essential contribution of the PVPF-FM module to network robustness and detection accuracy.

7. Conclusions

This paper proposes a novel change detection method for damaged buildings in re-al-world war-zone remote sensing imagery—CMSNet. The method synergistically combines the structural prior awareness of the SAM foundation model with the temporal modeling and fine-detail representation capabilities of CNN-Mamba, effectively addressing challenges such as non-rigid deformations, localized fragmentation, and blurred boundaries of buildings in complex warzone environments. By incorporating the PVPF-FM module, high-level structural guidance from SAM is deeply fused with bi-temporal optical image features, enabling CMSNet to enhance the modeling of structural consistency, semantic integrity, and boundary continuity in the mid-to-high-level feature representation stage. Additionally, this work introduces RWSBD, a large-scale, high-resolution real-world war-damaged building dataset from the Gaza region, providing a solid data foundation for war damage change detection. Extensive experimental results demonstrate that CMSNet significantly outperforms state-of-the-art methods across RWSBD and three other public datasets, achieving leading performance in IoU, F1-score, Precision, and Recall. The model exhibits particularly strong robustness and generalization in identifying fine-grained damaged regions and adapting to complex scenarios. This study not only innovatively integrates foundational visual models with efficient temporal modeling structures at the methodological level but also provides a valuable data benchmark for real-world war-damage building detection, offering substantial academic and practical significance.

Although CMSNet demonstrates high accuracy and robustness in detecting damaged buildings in real-world war-zone scenarios, certain limitations remain. First, this study relies solely on optical remote sensing imagery and does not incorporate cross-modal data such as SAR, which limits model stability under extreme conditions like cloud cover or optical image failure. Second, while the CNN-Mamba architecture achieves a balance be-tween feature modeling capability and computational efficiency, there remains room for improvement in large-scale rapid inference and lightweight deployment. Future work will focus on exploring cross-modal fusion techniques and more efficient network architecture to enhance the method’s applicability and scalability for multi-source remote sensing data and rapid post-disaster response over large areas.