1. Introduction

Tidal flats, which develop in intertidal coastal zones, cover approximately 127,921 km

2 (95% CI: 124,286–131,821 km

2), or about 14% of the global coastline, and serve as a core component of coastal ecosystems [

1]. They provide various ecological services, including biodiversity conservation, buffering against marine disasters, and serving as habitats for fisheries, and are increasingly recognized for their long-term blue carbon storage function [

2]. In particular, the west coast of South Korea is characterized by broad tidal flats that have developed due to flat topography and large tidal ranges and has been designated a UNESCO World Natural Heritage site under the name “Getbol, Korean Tidal Flats” [

3]. The sediment layers in tidal flats absorb atmospheric CO

2 and store it over long periods. The organic carbon stock in Korean tidal flats is estimated to be approximately 1.314 × 10

7 MgC, with an annual carbon sequestration rate of about 7.14 × 10

4 MgC/yr (≈2.61 × 10

5 tCO

2e/yr), which is equivalent to offsetting the annual emissions of approximately 110,000 passenger vehicles [

4]. However, the total area of Korea’s tidal flats has decreased by approximately 22.5% over 30 years, from 3203.5 km

2 in 1987 to 2487 km

2 in 2018, due to land reclamation and other anthropogenic factors [

5]. The loss of tidal flat area not only reduces carbon sequestration capacity but also degrades essential ecosystem functions such as coastal disaster mitigation and habitat provision. Therefore, it is necessary to continuously monitor tidal flat areas and geomorphological characteristics and to establish scientifically informed conservation strategies.

Various spatial data acquisition methods are employed to accurately survey and monitor changes in tidal flat topography, including satellite-based remote sensing, ship-based acoustic sounding, and drone- or aircraft-based LiDAR surveys [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Satellite imagery enables large-scale and repeated observation [

10,

11,

12], but has limitations in spatial resolution and tidal interference, making precise monitoring of intertidal changes difficult. Ship-based acoustic sounding provides high-precision bathymetric data, but in the shallow, high-tidal range coastal waters of Korea, it is inefficient due to limited operational windows and accessibility challenges [

13]. Drone- and aircraft-based optical or LiDAR sensors are advantageous for high-resolution DEM construction [

14] but are limited to exposed terrain and cannot provide continuous information for submerged areas [

15,

16].

To overcome these limitations, airborne bathymetric LiDAR (ABL) has gained attention. ABL utilizes 532 nm green lasers to penetrate the water surface and simultaneously capture reflections from the water column and seabed, enabling efficient observation of wide intertidal zones in short time windows. A LiDAR system records the signal intensity change over time as a waveform when a laser pulse reflects off an object. This waveform is then processed to decompose into the components of reflection from individual objects and convert them into points with a location [

17]. Therefore, ABL’s waveform is a continuous record of signals reflected from the water surface, water column, and seabed. Due to the laser’s refraction and underwater scattering effects as it passes through the water, different waveform processing techniques are required compared to typical land-based airborne topographic LiDAR (ATL). Since the performance of seabed observation is affected by the waveform processing technique applied, studies have been conducted to develop effective waveform decomposition techniques [

18]. Traditional approaches often assume fixed functional forms: Gaussian or Weibull models for water surface and bottom returns, and triangular or quadrilateral models for the water column, sometimes adapted according to water depth. Early studies established this framework using simulated LiDAR signals, where the surface, column, and bottom components were represented by Gaussian, triangular, and Weibull functions, respectively [

19]. Subsequent refinements introduced more flexible geometries: a quadrilateral fitting scheme was designed to better capture the asymmetric shape of underwater backscattering [

20], and exponential terms were later embedded into that model to simulate energy attenuation with depth [

21]. To reduce reliance on predefined analytical shapes, a depth-adaptive strategy was proposed that classifies waveform types based on empirical scattering patterns rather than fixed equations [

22]. While these methods have advanced the physical interpretation of ALB signals, their applicability remains limited under challenging conditions. Field validations have revealed substantial accuracy degradation in noisy environments, where standard deviations in bathymetry estimates increase significantly due to solar radiation interference and detector noise, with noise contributions accounting for over 60% of total uncertainty in some airborne configurations [

20]. Furthermore, weak bottom returns in deep or turbid water present critical challenges, as denoising algorithms designed to suppress noise may inadvertently filter out genuine but weak bottom signals [

22]. Each method still depends on calibration parameters tied to specific systems or environments, and performance deteriorates further when surface and bottom returns overlap with water column scattering. Thus, fixed-model decompositions continue to perform reliably only in clear-water settings with minimal interference and favorable signal-to-noise conditions.

Recent studies have explored flexible Gaussian decomposition methods that neither fix a specific model for each return component nor restrict the number of mathematical models, thereby enhancing ABL performance in complex underwater environments. Guo et al. [

23] introduced the Gaussian half-wavelength progressive decomposition (GHPD) method, which progressively applies half-wavelength Gaussian functions to reduce peak-position shifts caused by echo superposition and thereby improves bathymetric accuracy in shallow water. Another recent study [

24] proposed a method to solve weak underwater laser returns and superimposed waveforms, aiming to enhance the recognition of submerged echoes. Although effective in mitigating overlapping signals, this approach is still sensitive to noise and shows limitations in highly complex or variable environments. Fang et al. [

25] combined an adaptive B-spline model with particle swarm optimization (PSO) to improve the decomposition of overlapping echoes in full-waveform LiDAR data; however, under very low-SNR or high-noise conditions, the spline model tends to be over-fitted or may falsely detect reflection peaks. Within this research context, our earlier study [

26] developed the progressive Gaussian decomposition (PGD), which achieved improved waveform approximation by iteratively estimating potential peaks that were not initially detected. PGD was capable of handling atypical waveforms—such as overlapping peaks in shallow water, absent bottom returns in deep water, and weak bottom signals—leading to improved seabed detection performance. These flexible Gaussian decomposition techniques may be more suitable than fixed-model approaches for handling ABL waveforms collected in tidal flat environments, where rapid signal attenuation and waveform distortion caused by high turbidity, as well as the overlap of surface and bottom returns in very shallow water, are common. However, such methods remain vulnerable to strong noise and are limited by their inability to identify the water layer type of each decomposed component.

Recently, Wu et al. [

27] proposed a high-precision fusion strategy using multi-channel airborne LiDAR, in which waveform curvature and inter-channel information were jointly exploited to improve nearshore bathymetric accuracy. Although their approach effectively integrates multi-channel signals, the reliability of near-infrared (NIR) returns is often compromised by specular reflections from water surfaces, and many recently developed systems—aiming to improve efficiency and reduce system complexity—employ only a single green laser wavelength.

To address these limitations and further enhance bathymetric performance in tidal flat environments, this study proposes an adaptive PGD (APGD) method that extends the previous PGD framework. The workflow is designed to process single-wavelength green waveforms, which are increasingly relevant as modern systems adopt single-channel configurations for efficiency. The contributions of this study are threefold:

Empirical characterization of ABL waveforms in tidal flats, emphasizing high noise energy, peak overlap in shallow water, and strong attenuation effects.

A PGD update with residual-based adaptive termination to enhance stability and reduce overfitting in complex tidal flat waveforms.

A water-layer classification module that labels decomposed components and enables robust bottom detection without relying on a distinctly separated bottom peak.

We validate the proposed approach on tidal flat datasets covering a range of depths and turbidity levels, and we compare the results with those obtained from both a vendor-provided program and the conventional PGD method. The results demonstrate consistent improvements in bottom detection reliability and bathymetric completeness in tidal flat environments.

3. Methods

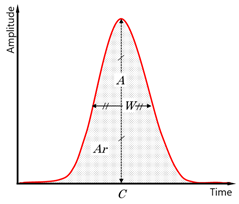

The green laser beam in ABL penetrates the water surface and propagates through the water column to the bottom. Its amplitude is rapidly attenuated by absorption, scattering, and refraction; if not fully extinguished, the backscattered signal returns to the receiver, revealing the water surface and bottom as peaks in the recorded waveform. A typical ABL waveform, therefore, consists of returns from the water surface, water-column backscatter, and bottom reflection, superimposed on noise. In processing, each waveform is decomposed into constituent components, the corresponding points are extracted, and a point cloud is generated (

Figure 2).

The LiDAR waveform can be modeled as a convolution of a Gaussian pulse and a surface scattering function, and it is often represented as a Gaussian mixture model, as in Equation (1), where parameters such as amplitude (

), center (

), and standard deviation (

) have physical meanings [

32]. To decompose the waveform into Gaussian models, iterative optimization (e.g., Levenberg–Marquardt) is used, requiring careful selection of initial parameter values. In conventional Gaussian decomposition (CGD), the number of Gaussian components

n is set to the number of initially detected peaks (local maxima). This intuitive approach is generally effective for ATL over land, where individual returns appear as distinct peaks.

However, ABL data often violate these assumptions because water-column backscatter produces left-skewed waveforms [

23]. In very shallow water, surface and bottom returns frequently overlap and appear as a single peak [

33,

34], impeding accurate separation with traditional Gaussian methods. In highly turbid environments, enhanced underwater scattering and absorption substantially reduce the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), hindering the transmission of bottom returns to the sensor [

35]. These effects increase waveform asymmetry and further complicate the separation of surface and bottom reflections.

Given these challenges in shallow, turbid, and dynamically varying waters such as tidal flats, waveform processing techniques must be tailored to local conditions. Accordingly, we first analyze the properties of waveforms acquired under these environments and then propose an ABL waveform processing framework optimized for them. The approach builds on our previously developed progressive Gaussian decomposition (PGD), and the overall workflow is illustrated in

Figure 3. The pipeline begins with noise removal to suppress background and random noise components, followed by signal range selection to isolate valid return segments. The refined waveform is then decomposed into Gaussian components through the adaptive PGD algorithm. Subsequently, waveform-derived features—such as amplitude, width, and area—are extracted and used for water-layer classification (surface, column, and bottom). The classified points are finally registered to generate the bathymetric point cloud.

3.1. Waveform Characteristics in Shallow and Turbid Waters

To analyze ABL waveform characteristics in tidal flat areas, we compared ABL (Seahawk) waveforms collected at the Hwangdo and Gomso Bay test sites with data acquired in clear waters off Korea’s east coast (mean SPM ≈ 4.5 mg/L in 2022). Relative to the clear-water site, waveforms from the turbid tidal flats often exhibited excessive or irregularly distributed random noise within portions of individual traces. For each waveform, the random noise level was estimated as the standard deviation of the no-signal range (0.10 µs; 160 bins) defined for the Seahawk system. In clear water, the random noise level averaged 91.03 ± 10.20 (max 235.40), whereas in the tidal flats it was 85.02 ± 19.34 (max 1264.33) at Hwangdo and 87.06 ± 16.62 (max 1291.14) at Gomso Bay, indicating strongly non-Gaussian behavior with occasional extreme bursts despite comparable means. This pattern is consistent with water column scattering under turbid conditions, which degrades the received signal’s SNR [

22].

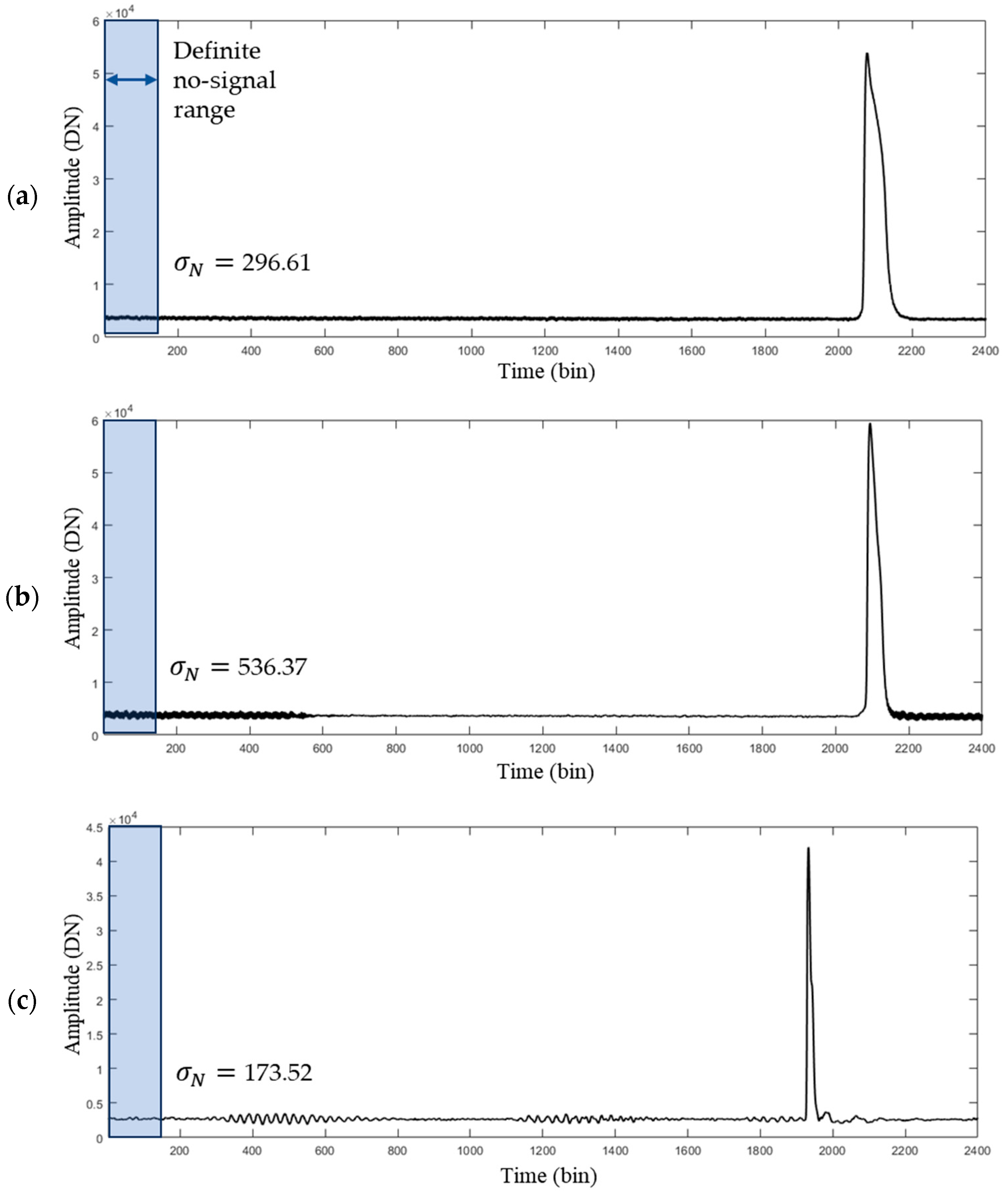

Figure 4 illustrates representative waveform types from turbid water with non-Gaussian random noise: (

Figure 4a) large but uniformly distributed noise across the trace, which can often be mitigated with conventional low-pass filtering or adjacent-measurement-based waveform stacking techniques [

36], which are designed to reduce ALB noise effects in shallow waters. However, (

Figure 4b,c) locally inhomogeneous, intermittent noise that is not easily removed by low-pass filtering alone. In case (

Figure 4c), automatic detection is particularly challenging because the no-signal range’s standard deviation is not itself large. Consequently, in turbid environments, it becomes critical to discriminate true reflection peaks from noise and to determine the actual signal range of the waveform with high fidelity.

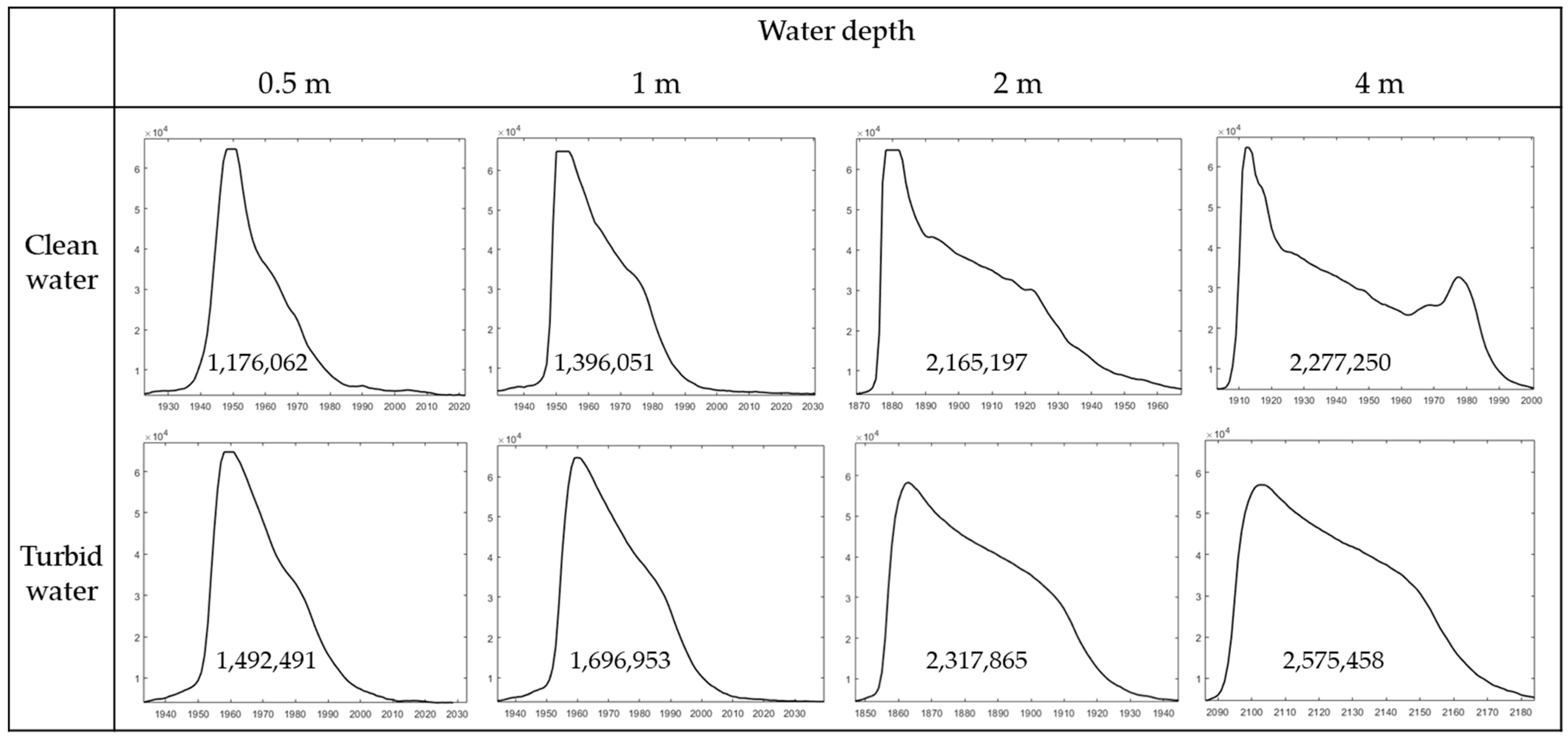

Figure 5 presents actual signal ranges of representative waveforms collected by the Seahawk system in shallow water under different turbidity conditions. Each column displays waveforms acquired at similar depths, with the annotated values denoting the integrated waveform area, which corresponds to the total return energy. (These examples are illustrative; actual waveform shapes may vary under different environmental conditions beyond just depth and turbidity.) At very shallow depths (approximately 0.5 m and 1 m), water surface and bottom reflections merge into a single peak in both clear and turbid waters, making it impossible to visually resolve a distinct bottom return. In clear water at deeper depths (2 m and 4 m), the water surface and bottom reflections become comparatively more distinct. In contrast, under turbid conditions, bottom returns remain inseparable from water surface and water column signals even at larger depths. This underscores the difficulty of isolating bottom components from ABL data in turbid environments, as well as the challenge of determining whether a waveform contains a true bottom return or only water surface and backscattered water column echoes.

Another important observation is that the waveform area varies with both turbidity and depth. Theoretically, the total integrated waveform area from a water column can be expressed as the sum of the cumulative water-column backscatter and the attenuated bottom reflection [

37]:

where

is the backscatter coefficient,

is the attenuation coefficient,

is the bottom depth, and

is the bottom reflectance. The first term represents the cumulative contribution of volume backscatter, which increases with depth before saturating, while the second term represents the bottom return that decreases exponentially with depth due to absorption and scattering. As shown in

Figure 5, an analysis of shallow-water data (depths < 5 m) revealed that the total waveform area increases with depth in both clear- and turbid-water conditions. This trend can be explained by the cumulative contribution of volume backscatter along the water column and the enlargement of the laser footprint with increasing depth, which together outweigh the effects of attenuation losses. In addition, for the same depth, the total area tended to be larger in turbid waters than in clear waters. This analysis indicates that, in shallow waters, the restricted reflection angles at shallower depths limit the amount of energy that can be collected. In addition, in turbid waters, increased underwater backscattering can lead to greater energy being detected by the sensor compared with clear water conditions [

38].

3.2. Preliminary Work

PGD [

26] was designed to decompose diverse forms of ABL waveforms acquired under varying conditions—such as different water depths, turbidity levels, and the presence of underwater objects—by iteratively estimating undetected potential peaks and progressively refining the Gaussian mixture model. As a preprocessing step, PGD applies noise removal and valid signal range selection to improve computational efficiency and minimize outliers. Noise reduction was achieved by subtracting the mode (the most frequently occurring value) of each individual waveform to eliminate background noise, followed by Gaussian smoothing to suppress random fluctuations. For signal range selection, the algorithm identified the portion of the waveform where the signal amplitude exceeded a threshold determined from the standard deviation of the no-signal range, thereby isolating meaningful return signals for subsequent analysis. Then, the decomposition process begins with local maxima, or original peaks (OPs), which are used as initial parameters for Gaussian fitting via the Levenberg–Marquardt optimization algorithm. After fitting, estimated peaks (EPs) are compared with the OPs. If the time difference between them is within a specified threshold (τ) and the model achieves sufficient fitness (R

2 between the original waveform and the approximated Gaussian mixture model), the iteration terminates. Otherwise, additional potential peaks are selected—typically those most distant from the OPs—and added to the initial values of the decomposition in subsequent iterations. In this way, PGD adaptively determines the optimal number of Gaussian components rather than fixing it a priori. For detailed descriptions of PGD algorithms and parameterization, readers are referred to [

26].

Despite these strengths, several limitations remain, particularly in shallow, turbid, and dynamic tidal flat environments (

Section 3.1). First, the signal-range selection step can misclassify large-amplitude, spatially localized noise as a valid signal. Second, using R

2 as a termination criterion is not always appropriate for nonlinear ABL waveforms. The types of misdecomposition that can occur due to these causes will be discussed in more detail in the next section,

Section 3.3. In addition, PGD focuses on decomposition itself and does not label each component by water layer type (surface, water column, bottom), which complicates robust seabed discrimination. These issues are exacerbated under high turbidity and overlapping returns, motivating the methodological refinements presented in the next section.

3.3. Adaptive Progressive Gaussian Decomposition

As a preprocessing step, the waveform undergoes noise removal and signal range selection. Background noise mainly originates from low-frequency noise generated by solar radiation and detector dark current, and is generally distributed uniformly throughout the waveform. Random noise is generally removed using low-pass filtering, and Gaussian filtering is applied for smoothing to minimize distortion of the original waveform:

where

is the original waveform

is the Gaussian filtered value at time

,

denotes the number of waveform samples, and

is the standard deviation of the Gaussian distribution.

Next, it is important to determine the valid signal range to improve computational efficiency and prevent outliers. Since valid signals occupy only a small portion of the waveform, restricting the analysis to the signal range enhances processing efficiency and prevents large-amplitude noise in the non-signal range from being misinterpreted as a reflection echo. The start point and end point of the signal range are based on the standard deviation (

) and mean (

) of the no-signal range. In the original PGD method, the start and end points of the signal range were simply defined as the positions where consecutive y-values increased or decreased by more than a multiple of the standard deviation. However, this approach can be inadequate when random noise occurs irregularly and excessively. To avoid misinterpreting noise as valid signals, we improved the signal range determination method as follows. The start point (

) of the valid signal range was determined as the point where the surface reflection signal begins, specifically where the signal amplitude (DN) exceeds

and shows a significant increase (greater than

) over at least five consecutive bins, and the point with the longest continuous section (

) was selected. Although specific implementations vary, many previous studies have similarly employed the

criterion derived from the no-signal region to determine valid signal ranges in LiDAR waveform analysis [

22,

39,

40]. The duration of five consecutive bins corresponds to 3.125 ns in the Seahawk system, and this threshold was empirically determined based on prior waveform analyses as a practical value that effectively suppresses random noise while still capturing the true onset of the signal in ABL waveforms. The end point (

) was determined as the point where the amplitude decreases below the DN value (

) at the start point.

To ensure stable multi-Gaussian model fitting, the background noise value was set to

, so that the DN value at the start point becomes zero. The waveform was then adjusted by subtracting this value:

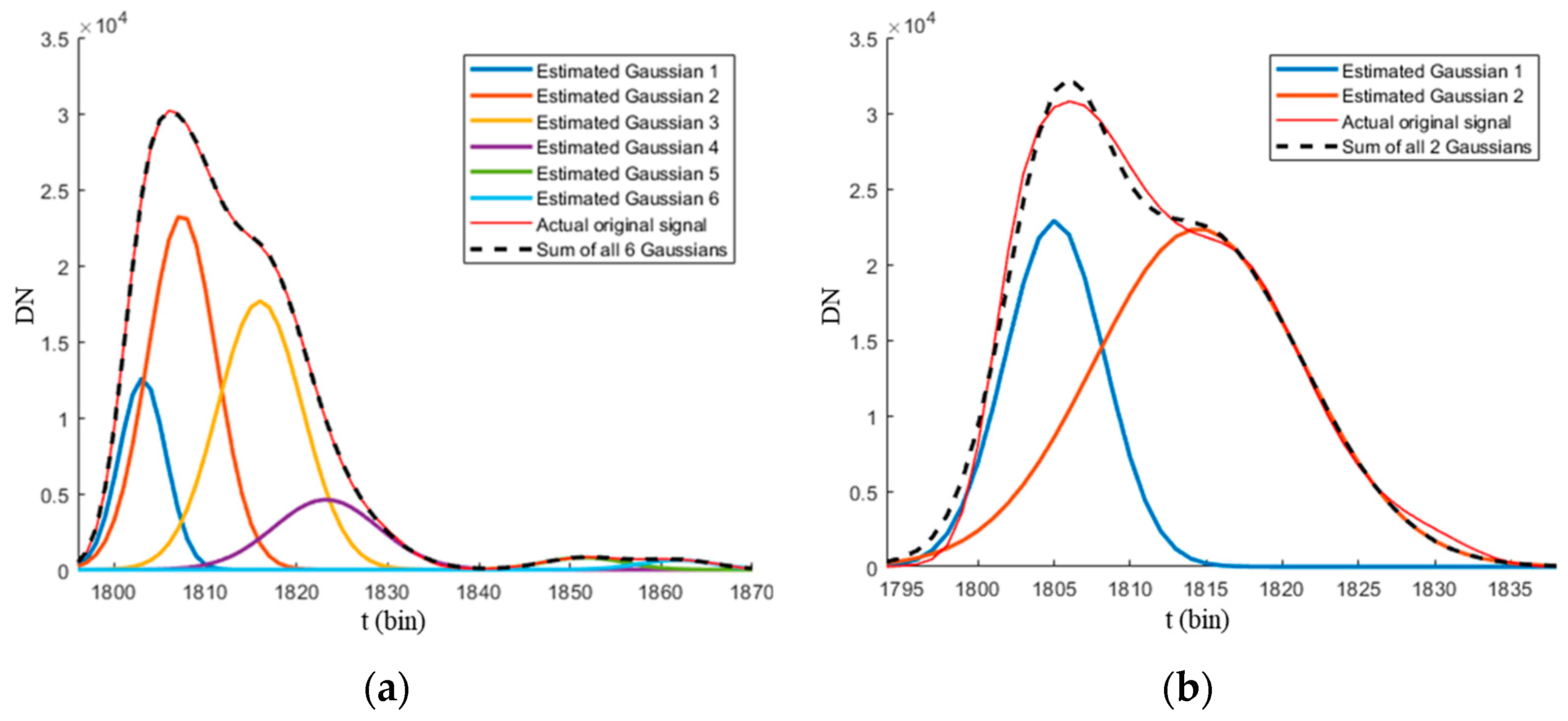

Figure 6 compares the results of signal range selection between the previous PGD method and the proposed approach for a waveform exhibiting excessive and irregular noise, as shown in

Figure 4c. The PGD method (

Figure 6a) included noise-dominated regions in the signal range, leading to incorrect decomposition and spurious components such as Estimated Gaussian Components 5 and 6. When these components are registered into points, they appear as outliers distributed below the actual seabed. In contrast, the proposed method (

Figure 6b) selected an appropriate signal range, preventing unnecessary iterative computations and yielding stable and accurate decomposition results.

Basically, the decomposition process of APGD proceeds similarly to PGD. However, as noted earlier, R2 used as a termination criterion is not suitable for assessing the fitness of nonlinear models. Instead, we adopted the maximum residual () as the termination criterion based on residuals. The modified waveform decomposition process can be expressed in the following steps:

Step . ;

Step . ; Gaussian curve fitting with

Step .

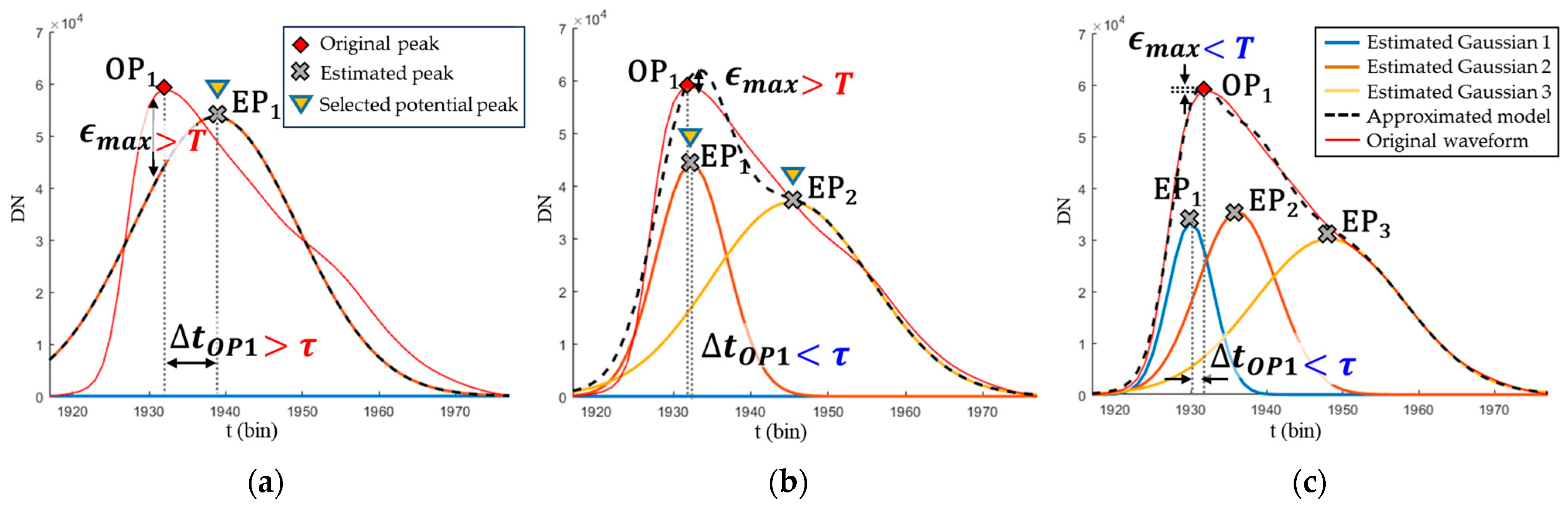

Figure 7 illustrates an example of the proposed APGD process. It shows the decomposition of a waveform recorded at a very shallow depth (0.8 m), where surface and bottom reflections overlap, resulting in only a single OP. In the first iteration (

Figure 7a), the number of Gaussian components is set equal to the number of OPs, and each produces an estimated peak. In this case, the

exceeded the threshold

, and

was also above the limit, prompting another iteration. The results of the first fitting (

Figure 7a) are equivalent to those of the CGD, demonstrating that CGD alone is insufficient for ABL waveforms. In the second iteration (

Figure 7b),

decreased compared with the threshold; however,

still exceeded the limit. In the conventional PGD method, this step would satisfy both termination conditions—

below the threshold and R

2 above 0.95—thus ending the iteration. However, the shape of the Gaussian-fitted waveform (black dashed line) does not approximate the original waveform (red line) well enough. Since the proposed APGD method adopts

as an additional termination criterion, it proceeds with further iterations. In this step, two EPs were selected as potential peaks for the initial value of the next iteration. The iterative fitting continued until both criteria were satisfied, producing the final Gaussian mixture models (

Figure 7c).

3.4. Water-Layer Classification Based on Waveform Features

The waveform decomposition method is designed to separate return components but does not inherently identify the type of water column layer (i.e., water surface, water column, or bottom) associated with each component. Typically, the first return component in waveforms acquired over water bodies can be attributed to the water surface, while subsequent returns are generally assumed to originate from the water column (

Figure 2). However, it remains necessary to determine whether the final return component represents an actual bottom reflection or a non-bottom return caused by subsurface scattering.

To address this, we employed waveform features to support bottom discrimination. Since each return component is modeled using Gaussian functions, various features can be derived for each component. In this study, we extracted features such as amplitude, center position, width, return number, number of returns, area, total area, area ratio, AW ratio, and normalized return (

Table 3), and examined their relevance for bottom detectability.

To classify whether the last component corresponds to a bottom return, we compared feature distributions between bottom-detected and non-bottom-detected areas. Feature importance was calculated based on the total Gini impurity reduction at each split in the decision tree, as implemented in scikit-learn [

41]. The resulting importance values in

Table 4 represent the relative contribution of each feature to the overall classification performance, normalized to a total of 100%. Feature importance analysis indicated that total area was by far the most influential feature, with an importance score exceeding 96%. Total area, defined as the sum of all Gaussian component areas within a waveform, represents the total reflected energy and decreases due to energy losses caused by surface reflection, underwater scattering, and bottom reflection. In particular, bottom reflection losses are influenced by diffuse scattering, subsurface penetration, bottom reflectivity, and the angle of incidence. The analysis further revealed that the total area of bottom-detected waveforms was generally smaller than that of non-bottom signals. Therefore, an empirical threshold was applied to classify water layers based on this feature. As discussed in

Section 3.1, however, waveform area is influenced by both turbidity and depth; thus, the threshold must be determined with consideration of these conditions in the study area.

5. Discussion

This study introduced an enhanced waveform-processing technique optimized for ABL surveys in shallow and highly turbid tidal flat environments. By refining signal-range selection and introducing an adaptive termination criterion, the proposed APGD method substantially improved bottom-detection robustness compared with the manufacturer’s LBASSD software and the conventional PGD approach. Across the two test sites, seabed coverage ratios ranged from 66.7 to 70.4%, and bottom-classification accuracies reached 97.3% and 96.7%. Positional accuracy evaluations further demonstrated that APGD reduced mean depth errors relative to PGD, thereby minimizing systematic bias and satisfying the IHO Order 1b standard.

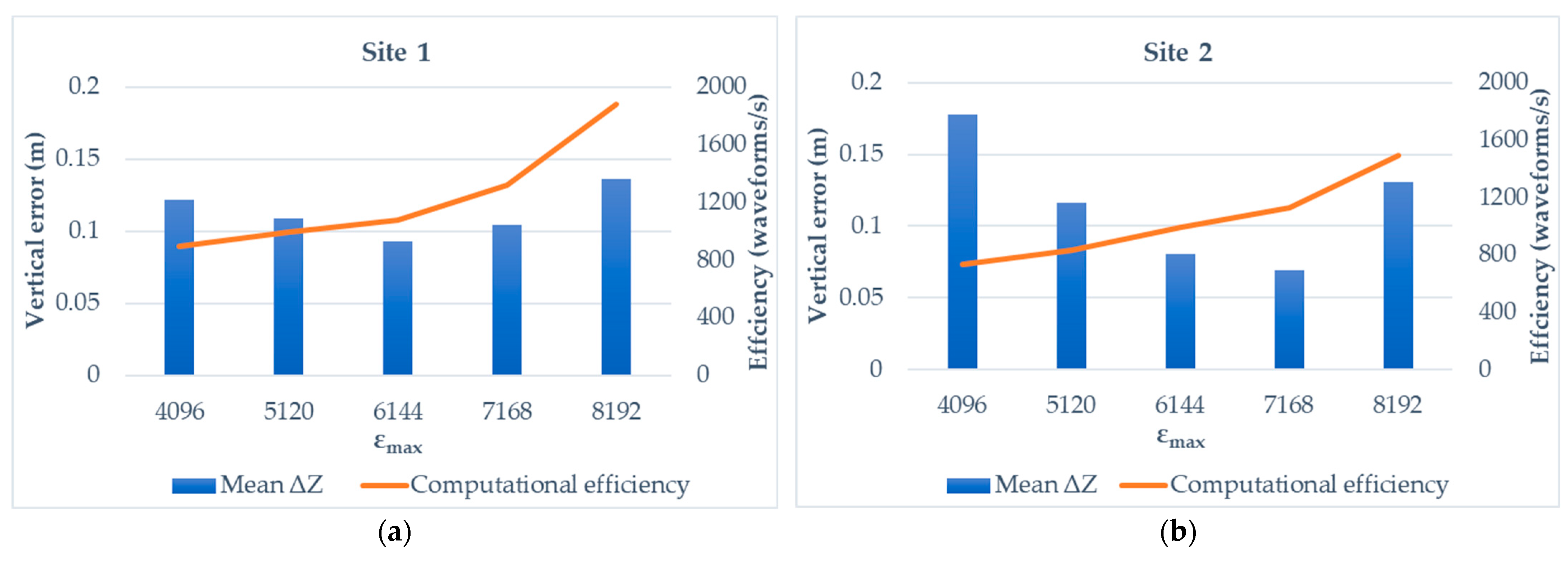

The sensitivity analysis of the termination parameter ε

max (

Figure 12) revealed a trade-off between bathymetric accuracy and computational efficiency. As ε

max increases, the waveform fitting becomes less constrained, resulting in faster convergence and higher processing rates. However, excessive ε

max values lead to coarse approximations and greater underestimation of bottom depths, as indicated by the increased mean vertical error (ΔZ). Conversely, smaller ε

max values impose stricter residual thresholds, improving fitting precision but at the cost of computational efficiency and potential over-fitting in highly noisy conditions. This behavior was consistent across both test sites, but the influence of ε

max was more pronounced at Site 2, which exhibited higher turbidity. In turbid environments, the received waveform contains stronger subsurface scattering and irregular noise components, increasing the risk of over-fitting when ε

max is too small. Therefore, a, respectively higher ε

max threshold is required to ensure stable decomposition and to suppress spurious bottom points. According to the sensitivity analysis, ε

max was set to 6144 for Site 1 and 7168 for Site 2. It is important to note that the ε

max values presented in this study are not absolute but were empirically determined for the Seahawk system operated in Korean tidal flat conditions. The optimal ε

max value is expected to vary depending on sensor characteristics as well as environmental parameters, including turbidity and water depth. Accordingly, ε

max should be treated as an adaptive parameter rather than a fixed constant, and further calibration is required to optimize it under different survey settings.

Waveform-feature analysis further supported this adaptive perspective. Among all extracted features, the total area (representing cumulative signal energy) was identified as the most influential factor for distinguishing bottom returns, showing consistent differences between bottom-detected and non-bottom-detected waveforms. Because total area is affected by both turbidity and depth, empirical thresholds for classification should also be adjusted according to the optical and environmental conditions at the survey site. These findings collectively underscore the importance of environment-specific calibration when applying rule-based waveform classification methods.

Finally, visual analyses (

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11) confirmed that APGD yields more continuous and reliable bottom surfaces under shallow and turbid conditions, and that classification results align closely with ATL and MBES ground truth. Overall, the proposed APGD waveform processing framework represents a scalable solution for high-resolution bathymetric mapping in complex waters, while also laying the groundwork for extended applications such as water–land boundary detection and submerged object identification.

While the proposed approach proved reliable, opportunities for further improvement remain. Turbidity can fluctuate substantially even within a single flight due to local tidal dynamics, making a single fixed threshold suboptimal for entire survey areas. Recent studies such as Chen et al. [

43] suggest that adaptive or machine-learning-based strategies may further enhance generalizability, particularly in low-SNR or highly turbid environments. Additionally, simultaneous turbidity estimation offers important potential. Future work may involve mounting ABL and hyperspectral imaging systems on the same aircraft to collect concurrent datasets over tidal flats. As part of a related project, precise calibration of hyperspectral imagery—including atmospheric correction tailored to tidal flat conditions—and turbidity-mapping supported by in situ measurements are currently underway. Such integration would allow real-time observation of turbidity and water-optical properties during ABL acquisition, providing valuable auxiliary parameters for APGD and improving bottom-detection robustness in optically complex waters. In parallel, deep-learning models may be used to automate waveform-based classification and adaptive threshold tuning, allowing APGD to self-optimize across diverse turbidity and noise conditions.

Although APGD was developed using Seahawk ALB data, its processing logic is fundamentally system-independent and can be applied to other waveform-recording ALB sensors through modest recalibration of parameters such as τ and εmax. To explore broader applicability and identify sensor-specific calibration requirements, validation experiments using another representative ALB system are currently in progress and will be reported in future work.