5.1. Implementation Details

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of IFADiff, we conducted both unconditional and conditional generation experiments on the synthetic datasets provided by HSIGene [

13]. The synthetic dataset consists of five different hyperspectral image datasets, including Xiongan [

34], Chikusei [

35], DFC2013, DFC2018, and Heihe [

36,

37]. To ensure spectral consistency, we applied linear interpolation to align all data to 48 spectral bands spanning the 400–1000 nm range [

38], and cropped them into

image patches with a stride of 128 for training the generative models. For the conditional generation experiments, to guarantee comparability with HSIGene, we similarly selected farmland, citybuilding, architecture and wasteland images from the AID dataset [

39], which were processed with the same stride and cropping strategy. This consistent preprocessing ensures that IFADiff operates on data prepared under the same conditions as the pretrained HSIGene backbone, allowing fair performance comparison and isolating the effect of the proposed sampling strategy.

During the inference stage of IFADiff, we set the sampling steps to 10, 20, and 50 to evaluate the trade-off between performance and generation efficiency under different sampling budgets. Notably, IFADiff can be seamlessly integrated into ODE solvers of arbitrary integer order, thereby enhancing the generation quality of diverse pretrained diffusion models while preserving sampling efficiency. In selecting ODE solvers for experiments, we adopted the first-order DDIM [

15] and the fourth-order PLMS [

20] as baseline methods. In addition, we designed ablation studies to analyze the influence of the fractional order parameter

on generation quality, and further compared our approach with single fractional-order methods to validate the effectiveness of the alternating sampling framework.

To comprehensively evaluate the performance and perceptual quality of the generated hyperspectral images, we employed a combination of reference-based and no-reference image quality metrics:

(1) Reference-based metrics. Inception Score (IS) [

40] measures both the realism and diversity of generated images by assessing the entropy of predicted class distributions from a pretrained Inception network, where higher IS values indicate more realistic and diverse samples. Structural Similarity Index Measure (SSIM) [

41] evaluates the structural fidelity between generated and reference images by comparing luminance, contrast, and texture components; higher SSIM denotes better spatial and structural consistency. Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity (LPIPS) [

42] computes perceptual distances in deep feature space, reflecting how similar two images appear to the human visual system. Lower LPIPS values correspond to higher perceptual similarity. Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) measures the average pixel-wise spectral deviation between generated and real hyperspectral signatures, where lower values indicate more accurate radiometric reconstruction. For unconditional HSI generation without paired references, each generated spectrum is assigned a pseudo-reference by finding its closest real spectrum via Euclidean nearest-neighbor matching. Spectral Angle Mapper (SAM) computes the angular difference between generated and real spectra, reflecting similarity in spectral shape independent of magnitude. In the unconditional setting, SAM is likewise calculated between each generated spectrum and its nearest real spectrum obtained through spectral nearest-neighbor search.

(2) No-reference metrics. To evaluate image quality in the absence of ground-truth references, we adopted several blind image quality assessment (IQA) measures implemented in the PyIQA framework [

43]. Natural Image Quality Evaluator (NIQE) [

44] models natural scene statistics to estimate perceived distortion without supervision. Lower NIQE scores indicate more natural-looking images. Perception-based Image Quality Evaluator (PIQE) [

45] assesses local distortions such as blurring and artifacts based on block-wise spatial analysis, with lower values denoting better quality. Blind Referenceless Image Spatial Quality Evaluator (BRISQUE) [

46] quantifies deviations from natural scene statistics using spatial features, where smaller values represent higher perceptual quality. Finally, the Neural Image Assessment (NIMA) [

47] employs a deep neural network trained on human aesthetic ratings to predict perceptual quality scores. Higher NIMA scores indicate greater visual appeal.

Among these metrics, lower PIQE, BRISQUE, and LPIPS values and higher SSIM, IS, and NIMA values correspond to better overall image quality. These complementary metrics jointly capture fidelity, perceptual realism, and structural coherence, providing a comprehensive assessment of both visual and spectral–spatial performance. For all experiments, each configuration was conducted five times with different random seeds, and the reported results are presented as the mean and standard deviation across these runs to ensure statistical robustness.

All experiments were conducted on a Linux server equipped with dual Intel Xeon Gold 6226R CPUs (2.90 GHz, 64 threads) and eight NVIDIA Tesla V100 GPUs (32 GB memory each). The implementation was based on PyTorch 1.12.1+cu113 (Meta Platforms, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA) with CUDA 11.3 (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and cuDNN 8.3.

5.2. Unconditional Generation

In the unconditional generation experiments, we employed the pretrained HSIGene model to evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed IFADiff. Under a uniform timestep setting, IFADiff was applied to two representative integer-order solvers, DDIM and PLMS, to verify its generality. In addition to these solvers, we further compared IFADiff with several advanced multi-step integer-order methods, including DEIS, DPM-solver++, and UniPC, to comprehensively validate the effectiveness and robustness of the proposed approach. A total of 1024 hyperspectral images with a resolution of

were synthesized for evaluation. Quantitative results under 10, 20, and 50 sampling steps are summarized in

Table 2. Across all configurations, IFADiff consistently outperforms the baseline solvers in both reference-based (RMSE, SAM) and no-reference (IS, BRISQUE, PIQE, NIMA) quality metrics. Particularly at small step counts (e.g., 10), IFADiff achieves substantial gains in IS and perceptual scores, demonstrating its ability to enhance generation quality while maintaining efficiency.

In contrast, solvers such as DPM-Solver++ and UniPC, though often referred to as multi-step methods, are essentially coupled multi-stage schemes that perform several network evaluations within a single update. Their composite formulations are not directly compatible with the explicit single-step structure required by IFADiff; incorporating them would first require decoupling into equivalent single-step forms, which we leave for future work. Moreover, their single-step variants degenerate to DDIM, which is already included as a baseline. Therefore, in this paper we mainly evaluate IFADiff within the DDIM and PLMS frameworks to ensure a fair and representative comparison.

Visual comparisons further corroborate these findings. As shown in

Figure 3, when the number of sampling steps is small, DDIM and PLMS often produce blurry textures and degraded spectral details. In contrast, IFADiff (DDIM) and IFADiff (PLMS), incorporating fractional-order corrections into the sampling process, generate sharper spatial structures and more consistent spectral characteristics. At 10 and 20 steps, IFADiff effectively reduces boundary artifacts and restores fine textures absent in the baselines. Although advanced solvers such as DPM-solver++ and UniPC also achieve competitive results with fewer steps, IFADiff exhibits superior stability, smoother convergence, and more balanced performance across visual and spectral metrics. Even with more sampling steps (e.g., 50), IFADiff continues to produce clearer edges and finer textures as results converge toward the baselines. These results demonstrate that the proposed alternating integer–fractional strategy not only accelerates convergence but also enhances spectral–spatial fidelity in high-dimensional HSI generation. Similar trends are observed in

Appendix A.1.

In addition,

Figure 4 presents the intermediate denoising results of IFADiff and DDIM during the sampling process. It can be observed that IFADiff converges to the final result earlier and faster, showing stronger stability throughout the iterative process. Moreover, IFADiff demonstrates a superior ability to preserve emerging structural features in the intermediate stages, whereas DDIM tends to oversmooth or even erase these details in subsequent iterations.

To assess the physical plausibility of the generated spectra, we analyze the average spectral reflectance and its first-order derivatives of the unconditionally generated HSIs. Since the employed model has no paired reference HSI for pixel-wise evaluation, we instead compare the average spectral curves of our method and the baselines. As shown in

Figure 5, IFADiff produces smoother and more physically consistent spectral curves over 400–1000 nm. When combined with DDIM or PLMS, it suppresses high-frequency oscillations while preserving key reflectance transitions. The derivative plots also exhibit smaller fluctuation magnitudes than DPM-Solver++ and UniPC, indicating improved spectral smoothness and physical consistency.

We further evaluated the computational efficiency of IFADiff. As summarized in

Table 3, IFADiff introduces negligible GPU memory and runtime overhead across different solvers and sampling steps. For instance, at 10 sampling steps, IFADiff (

) + DDIM requires only 0.7‰ additional memory and even slightly reduces inference time (

) compared with DDIM. At higher steps (e.g., 50), all IFADiff variants maintain less than 1‰ memory overhead, while higher-order solvers such as DPM-solver++ and UniPC incur 5–10× greater resource costs. These results confirm that IFADiff significantly improves performance without sacrificing computational efficiency, making it practical for large-scale diffusion-based HSI generation.

Notably, we observe that the choice of fractional order should vary with the number of sampling steps. When the step count is small and the baseline generation quality is relatively poor, a larger is beneficial because it incorporates more information from past states, helping to compensate for insufficient predictions and improving spectral–spatial fidelity. However, as the number of steps increases, relying too heavily on historical states introduces redundant noise from earlier steps, making a smaller preferable to avoid overcorrection and maintain stable, high-quality generation. In practice, should be set relatively large for small step counts and gradually decreased as the steps grow, a trend consistently observed in both unconditional and conditional generation experiments.

5.3. Conditional Generation

In the conditional generation experiments, we likewise employed the pretrained HSIGene model, using DDIM and PLMS under the uniform timestep setting as baseline solvers. Following CRSDiff [

17], four types of conditional inputs were adopted to guide the generation process: HED (Holistically-nested Edge Detection), which extracts hierarchical edge and object boundary features; Segmentation, which provides semantic masks of the HSI data; Sketch, which represents the image as simplified line drawings capturing contours and structural shapes; and MLSD (Multiscale Line Segment Detection), which detects straight line segments to encode structural layouts. For each condition, we performed comparative analyses under 10, 20, and 50 sampling steps.

Table 4 reports the quantitative results for the HED condition. Across different step settings and

values, IFADiff consistently outperforms the DDIM baseline by achieving higher SSIM and NIMA scores, along with lower NIQE, BRISQUE, LPIPS, PIQE, RMSE, and SAM values. Similar to the unconditional generation setting, we also observe that larger

values are more suitable under fewer sampling steps, while

should be gradually reduced as the number of steps increases to avoid noise accumulation and overcorrection. These results indicate that IFADiff not only enhances the structural fidelity of the generated images but also improves their perceptual quality, especially under a small number of sampling steps. Similar trends are observed for the other conditional settings, confirming the general effectiveness of our method. The detailed quantitative comparisons for MLSD, Sketch, and Segmentation are provided in

Appendix A.2.

Visual comparisons in

Figure 6 further demonstrate these advantages. When guided by HED, MLSD, Sketch, or Segmentation maps, baseline DDIM often struggles to fully preserve structural cues, producing blurry or inconsistent textures under low sampling steps (e.g., 10). In contrast, IFADiff generates outputs that better align with the input conditions, recovering sharper boundaries in HED, more coherent line structures in MLSD and Sketch, and clearer region layouts in Segmentation. Notably, under HED, MLSD, and Segmentation conditions, the results obtained with only 10 steps are already close to those generated with 50 steps, further highlighting the efficiency of the proposed approach. Even at larger step counts (20 or 50), IFADiff continues to deliver improvements, underscoring the benefits of the integer–fractional alternating inference strategy for conditional HSI generation.

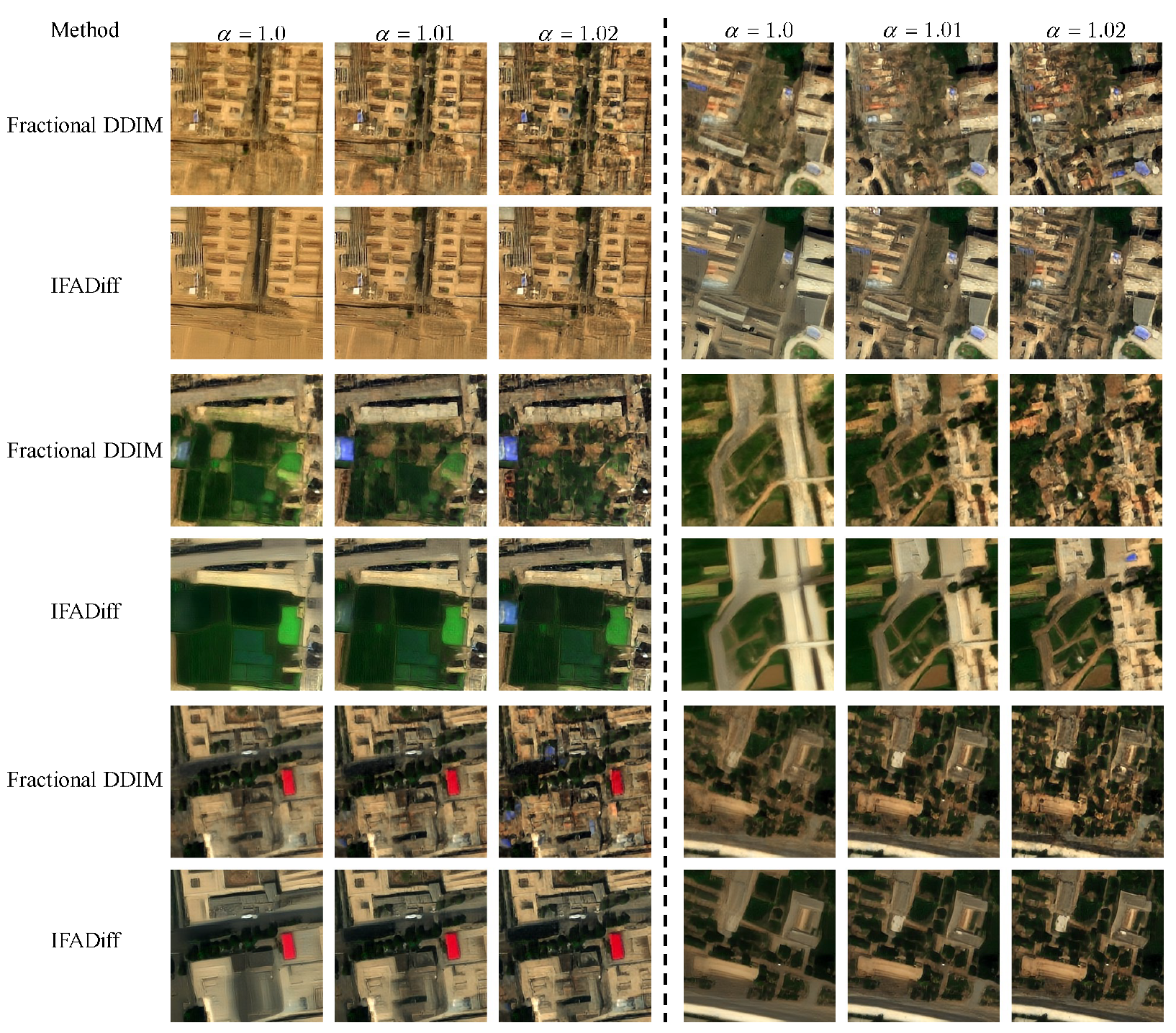

5.4. Ablation Study

In this section, we analyze the effect of the fractional order

on the performance of IFADiff. The experiments were conducted under the unconditional generation setting with 10 sampling steps. The results for 20 and 50 sampling steps are provided in

Appendix A.3, and they lead to conclusions consistent with those observed under 10 steps. We compared the proposed IFADiff, which alternates between integer-order and fractional-order updates, against two counterparts: the standard integer-order DDIM and the purely fractional-order variant (denoted as Fractional DDIM). Notably, when

, Fractional DDIM reduces to the standard DDIM solver, serving as a natural reference point for comparison. Such a three-way comparison highlights the respective strengths and weaknesses of integer-only and fractional-only approaches, and more clearly demonstrates the advantages of the alternating strategy in achieving stable and high-quality HSI generation.

As shown in

Table 5 and

Figure 7, when

, IFADiff achieves the highest IS score, but its PIQE value does not surpass that of DDIM and the outputs appear overly smoothed with suppressed details. This inconsistency arises from the nature of IS: since it measures classifier confidence, smoother images with reduced high-frequency noise yield sharper posterior distributions, thereby inflating the score. However, this does not imply better perceptual quality—BRISQUE and PIQE clearly indicate that oversmoothing degrades naturalness and fidelity, underscoring the need for multiple metrics beyond IS. Because results at

already suffer from excessive smoothness, we did not test smaller values, as they would exacerbate this issue. Therefore, our experiments focus on

. As

increases toward 1.02, IFADiff achieves the best BRISQUE and PIQE while maintaining competitive IS, and the generated images exhibit richer textures and greater diversity. However, when

exceeds 1.02, the generation process becomes prone to instability and amplified noise, leading to a degradation in overall image quality, with IS scores even falling below those of DDIM.

Therefore, in practical applications, can be flexibly adjusted according to user requirements: values closer to 1.0 (e.g., around 1.01) are preferable when smoother and cleaner outputs with fewer artifacts are desired, whereas slightly larger values (e.g., around 1.02) are suitable for scenarios prioritizing richer details and higher content diversity. Consequently, the optimal range of lies between 1.01 and 1.02. This trade-off is consistent with the trends observed in the conditional generation experiments, where smaller values favor structural clarity under sufficient sampling steps, while larger values better preserve fine-grained details when fewer steps are available.