1. Introduction

In recent years, the use of Uncrewed Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) has rapidly expanded within the field of remote sensing, propelled by both scientific advancements and commercial success [

1]. UAVs, or Uncrewed Aerial Systems (UASs), are now widely used in diverse applications including agriculture and forestry for crop monitoring and precision farming, environmental assessments, firefighting for detection and management of forest fires and support in emergency operations, and earth observation tasks such as aerial photography, mapping, and surveying. The increasing popularity of UASs in remote sensing is largely attributed to several factors. Compared to traditional satellite and crewed aerial platforms, UAS offer significantly higher spatial, spectral, and temporal resolution at a much lower cost [

1]. Furthermore, their low-altitude operation—typically under 120 m above ground level (AGL)—reduces the atmospheric path length, thereby minimizing radiative interference and decreasing the need for complex atmospheric corrections [

2]. UASs also provide operational flexibility. They can be rapidly deployed on-demand, including under partially cloudy conditions, as long as clouds remain above the flight altitude. This capability allows for consistent data collection even when satellite-based observations are impeded by cloud cover. Additionally, advances in electronics and materials science have contributed to the development of lightweight navigation systems, flight controllers [

2], and durable plastic chassis with mechanical properties comparable to metal-based frames [

3]. These innovations have improved flight efficiency and extended operational time. Together, these attributes—coupled with cost-effectiveness and ongoing technological improvements—position UAS as powerful platforms for remote sensing. However, the rapid expansion of UAS applications has also underscored the need for standardized image calibration procedures and improved data quality.

Radiometric calibration is a fundamental requirement for any optical sensor used in scientific remote sensing. All optical sensors initially record measurements in arbitrary units, typically referred to as Digital Numbers (DN). Without calibration—i.e., the conversion of DN values into physical radiometric quantities such as radiance, reflectance, or temperature—these values are not scientifically meaningful and cannot be reliably used for analysis [

3]. Consequently, consistent, accurate, and reproducible radiometric calibration is essential for all UAS-based remote sensing data intended for research applications.

Prior to deployment, optical sensors are generally calibrated in controlled laboratory environments. This is commonly performed using an integrating sphere or a calibrated reflectance panel illuminated by a traceable light source [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Such laboratory characterization is also critical for evaluating key sensor properties including dark current, non-uniformity, radiometric linearity, and vignetting effects, all of which influence sensor performance and data quality.

Once deployed in the field, sensor performance may drift due to environmental conditions. For satellite-based sensors, factors such as launch vibration and exposure to the space environment can alter their initial calibration. To mitigate this, most satellite systems include onboard calibration mechanisms—such as solar diffusers, lamps, or shutter-based dark calibrators—that monitor sensor stability over time. Additionally, independent validation is conducted using ground-based measurements and pseudo-invariant calibration sites (PICS) [

8,

9,

10,

11]. For UAS-mounted sensors, radiometric calibration is typically performed using one of three main approaches: the Empirical Line Method (ELM) using reflectance calibration panels, the use of downwelling irradiance sensors, or radiative transfer modeling [

12,

13,

14]. Radiative transfer models estimate at-sensor radiance based on atmospheric and illumination conditions using complex radiative transfer codes. However, these models require detailed atmospheric characterization, which can be difficult to obtain accurately in the field.

ELM remains one of the most widely used methods for UAS applications due to its simplicity and reliability. It requires one or more known reflectance targets within the image scene and directly relates DN values to surface reflectance. More recently, the use of downwelling irradiance sensors mounted on UAS platforms has gained traction. These sensors measure incident solar radiation during flight, enabling reflectance calibration without the need for external ground targets [

13,

14,

15] although results can be inconsistent [

16].

The Headwall Nano-Hyperspec hyperspectral sensor and the MicaSense RedEdge-MX Dual multispectral imaging system are widely utilized in agricultural applications, including crop health monitoring and land cover/land use classification. Multispectral sensors, such as the MicaSense system, acquire imagery in a limited number of broad spectral bands and are commonly used for vegetation indices and general land surface monitoring [

17]. In contrast, hyperspectral sensors like the Nano-Hyperspec capture data across hundreds of narrow, contiguous spectral bands, making them particularly well-suited for applications requiring high spectral resolution, such as mineral identification, nutrient deficiency detection [

18] and/or plant disease monitoring [

19]. UAS-mounted sensors typically generate radiance or reflectance products based on internal metadata and the spectral profile of artificial calibration targets recommended by the manufacturer. These calibration parameters are generally fixed unless the sensor undergoes a new laboratory calibration or in-field radiometric adjustment. In many instances, UAS sensors are not individually calibrated, and default metadata values are used across different systems [

6]. Furthermore, both sensor sensitivity and calibration target reflectance may degrade over time, potentially compromising data quality. Addressing these factors is essential to ensure the accuracy of radiometric products generated from UAS platforms.

The primary objective of this study is to evaluate the absolute radiometric calibration performance of the Headwall Nano-Hyperspec hyperspectral sensor and the MicaSense RedEdge-MX Dual Camera multispectral sensor. Reflectance products derived using the manufacturer’s recommended calibration procedure were compared to in situ measurements for validation. The Empirical Line Method (ELM) was applied to enhance the radiometric accuracy of reflectance outputs from both sensors. Additionally, this study investigates the influence of calibration target characteristics—including material type, size, reflectance intensity, and quantity—on the effectiveness of radiometric calibration for UAS-based imaging systems.

2. Materials and Methods

To achieve the objectives of this study, a field campaign was conducted from 15 to 18 July 2023, at the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Earth Resources Observation and Science Center (EROS) Ground Viewing Radiometer (GVR) site in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, USA. The campaign was supported by the USGS EROS Cal/Val Center of Excellence (ECCOE) and the USGS National Uncrewed Systems Office (NUSO), which provided calibration targets, instrumentation, remote pilots, and field personnel.

2.1. Field Campaign

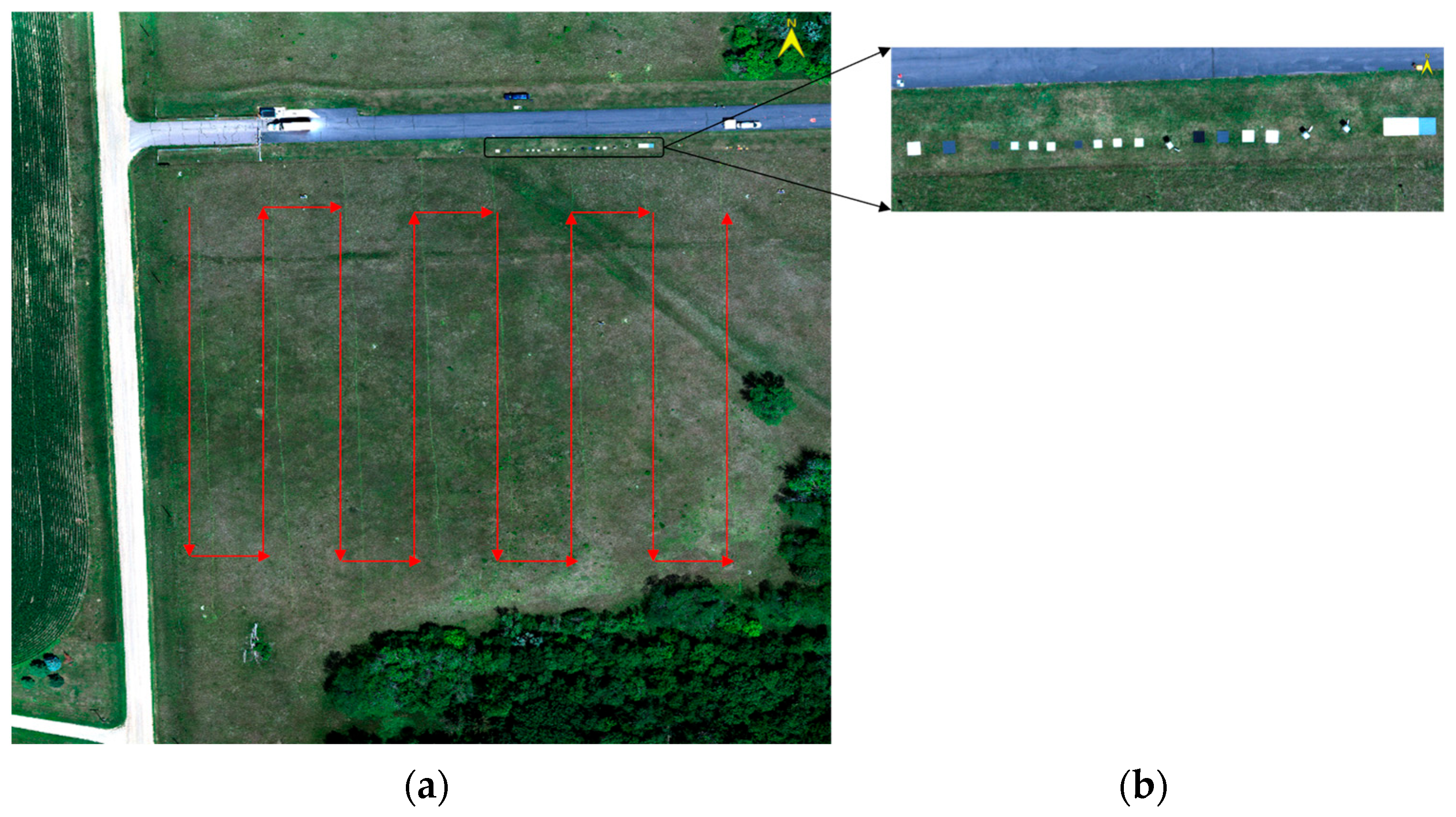

This field campaign was conducted over a 160 m × 160 m vegetated area at USGS EROS that has been used for Landsat sensor calibration and validation since 2021 (

Figure 1). The campaign involved three daily UAS flights for each sensor—Headwall Nano-Hyperspec (hyperspectral) and MicaSense RedEdge-MX Dual (multispectral)—over the course of four days, from 15 to 18 July 2023. A summary of the flight schedule is provided in

Table 1.

For each flight, UAS platforms first acquired images of calibration targets, followed by imaging of the EROS GVR site. The campaign was specifically designed to coincide with satellite overpasses from platforms including Landsat 9 Operational Land Imager (OLI), Sentinel-2A Multispectral Imager (MSI), and the Environmental Mapping and Analysis Program (EnMAP). This coordination aimed to enable cross-platform validation of surface reflectance measurements. However, during the first three days, coincident satellite overpasses were adversely affected by cloud cover and wildfire smoke [

20]. As a result, direct comparisons between UAS and satellite imagery are not presented in this paper. Atmospheric conditions on 18 July 2023 were improved relative to the previous days. Consequently, only data acquired on this date are presented and discussed in the remainder of this study.

Both the Headwall and MicaSense sensors were flown at an altitude of 200 feet (62 m) above ground level (AGL). This altitude was selected as a tradeoff between full coverage of the EROS GVR site and the limitations of UAS battery life. At this altitude, the entire site could be surveyed using a single battery, minimizing the time gap between acquisition of calibration targets and natural vegetation. Flying at a lower altitude would have extended the overall flight duration, thereby increasing the time interval between the acquisition of calibration target images and the sampling of the natural site. This extended interval could also introduce greater variability in solar angle during data collection, potentially compromising the fidelity of the radiometric calibration.

2.2. Targets

A variety of calibration targets were deployed during the field campaign. Because one of the focuses of the campaign was on evaluating different materials for constructing artificial targets suitable for calibration and validation of UAS imagery, some targets were fabricated at USGS EROS, while others were acquired from commercial vendors.

Table 2 shows the summary of target material, size, and source of artificial calibration targets.

Figure 1b shows the layout and variety of artificial targets that were used during the field campaign.

Targets were made from six different materials: felt, melamine, plywood, Permaflect, Spectralon, and pigmented polyester fabric. Felt targets were purchased and wrapped around thick material for structure and support. Melamine and Plywood targets were commercially purchased and subsequently painted with different levels of intensity-modifying paint at EROS. The following paints, each with a flat finish and applied using a roller, used in this experiment were: Dura Clean (Dutch Boy Paints, Cleveland, OH) colors True Black (DFTB), Ultra-White (DFUW), Refined Gray (DFRG), Baltic Gray (DFBG), and Pittsburgh Ultra (The Pittsburgh Paints Company, Cranberry Township, PA) color Light Drizzle (PFLD). Permaflect and Spectralon targets were manufactured by Labsphere (North Sutton, NH, USA) and Malvern Panalytical (Malvern, Worcestershire, UK), respectively. Fabric tarps manufactured by Group 8 Technology, Inc. (Provo, UT, USA) with three grayscale levels were provided by Headwall Photonics, Inc. (Bolton, MA, USA) as part of the purchase of their hyperspectral sensor for calibration.

In addition to material variations, targets of different sizes were also employed. The fabric tarps were 1.4 m × 1.4 m, felt targets were 0.9 m × 0.9 m, Melamine and Plywood targets were 0.6 m × 0.6 m, Permaflect targets were 1 m × 1 m, and Spectralon panels were approximately 0.3 m × 0.3 m in size. A 150 m × 150 m homogeneous vegetated area at the EROS GVR site served as the natural target for comparison.

Using targets of different materials and sizes provided insights into the impact of target characteristics on the calibration and validation of UAS-acquired imagery.

2.3. Equipment Used

The EROS ECCOE field team operated a field spectrometer to measure the surface reflectance of both the EROS GVR site and the artificial calibration targets [

21]. Simultaneously, the USGS NUSO team operated the UAS platforms to acquire imagery of the same targets and vegetated site [

22]. The spectrometer measurements were calibrated using a reflectance calibration panel that provided reference data for evaluating the radiometric accuracy of the UAS-derived reflectance products. Additionally, spectrometer-based measurements of the calibration targets were used to calibrate the UAS imagery through implementation of the Empirical Line Method (ELM).

The technical specifications of the primary equipment used during the field campaign are detailed in the following sections.

2.3.1. UAS Sensor Overview

The technical specifications of the Headwall Nano-Hyperspec hyperspectral sensor and the MicaSense RedEdge-MX Dual multispectral sensor used during the field campaign are described in the sections below.

Headwall Nano-Hyperspec

The Headwall Nano-Hyperspec (Headwall Photonics, Inc., Bolton, MA, USA) is a pushbroom hyperspectral sensor, which captures imagery line-by-line as the UAS moves along its flight path. Each line consists of 640 spatial pixels, with all pixels recorded simultaneously across 274 spectral channels. The sensor operates with 12-bit radiometric resolution and captures data across the visible to near-infrared range, from 398 nm to 1002 nm. It has a spectral sampling interval of approximately 2.2 nm, with a full width at half maximum (FWHM) of ~6 nm [

23]. The sensor was paired with a 12 mm focal length lens. Additional technical details and performance characterizations of the sensor are available in [

7,

24].

MicaSense RedEdge-MX Dual Camera Imaging System

The MicaSense sensor is a five-band multispectral imaging system designed for agricultural applications such as crop health monitoring and precision management [

6]. The MicaSense RedEdge-MX Dual Camera System (AgEagle Aerial Systems Inc., Wichita, KS, USA) consists of two integrated five-band sensors: the RedEdge-MX and the RedEdge-MX Blue. Together, the system captures imagery across 10 distinct spectral bands.

The MicaSense sensor operates at a maximum capture rate of one image per second with a field of view (FOV) of 47.2°. The center wavelengths and full width at half maximum (FWHM) values for each spectral band are provided by the manufacturer and listed in

Table 3.

The relative spectral responses (RSRs) of the MicaSense RedEdge-MX Dual system are shown in

Figure 2. The RedEdge-MX and RedEdge-MX Blue sensors are represented by solid and dashed lines, respectively. RSRs for the RedEdge-MX were characterized through laboratory measurements, while those for the RedEdge-MX Blue were modeled using Gaussian distributions based on the manufacturer-provided center wavelengths and FWHM values in

Table 3.

2.3.2. Spectrometer

The primary instruments used in this study included a pair of general-purpose spectrometers, each paired with a calibrated white reference panel. The spectrometers were FieldSpec 4 models acquired from Malvern Panalytical (Malvern, Worcestershire, UK). Internally, the FieldSpec 4 system integrates three spectrometers within a single housing: a visible and near-infrared (VNIR) spectrometer covering 350–1000 nm, a shortwave infrared (SWIR 1) spectrometer covering 1000–1800 nm, and a SWIR 2 spectrometer covering 1800–2500 nm [

25]. Designed for field portability, the FieldSpec 4 features an 8° fore-optic field of view (FOV) and measures radiant energy across a broad spectral range from 350 nm to 2500 nm. The instrument offers 1 nm spectral sampling and variable spectral resolution: approximately 3 nm in the 350–1000 nm range and 10 nm in the 1000–2500 nm range. Spectral sampling precision is 1.4 nm in the 350–1000 nm range and 1.1 nm in the 1000–2500 nm range. Wavelength accuracy across the full spectral range is ±0.5 nm. The instrument was radiometrically calibrated by Malvern Panalytical, with reported radiance calibration uncertainties of 3.58% at 350 nm, 2.56% at 654.6 nm, 2.38% at 900 nm, 2.35% at both 1600 nm and 2000 nm, and 3.15% at 2400 nm. The long-term stability for these channels is approximately 2%.

2.3.3. Reference Calibration Panel

Another key component used in this study was the Spectralon

® panel, manufactured by Labsphere, Inc. (North Sutton, NH, USA). The 12″ × 12″ (0.3 m × 0.3 m) Spectralon panel served as a reflectance calibration standard for spectrometer measurements and was essential for computing surface reflectance using the reflectance-based method [

26,

27,

28]. Each Spectralon panel, commonly referred to as a “white reference panel,” was characterized at the manufacturing facility, where its spectral reflectance was measured under controlled laboratory conditions. A set of calibration constants was provided by the manufacturer. However, the panels were not initially characterized for hemispherical bidirectional reflectance factor (BRF). Therefore, the panels were further characterized by the College of Optical Sciences at the University of Arizona, which performed comprehensive hemispherical BRF measurements and quantified associated uncertainties. Additional technical details about the spectrometer and Spectralon panel can be found in [

25,

29].

2.4. Data Collection Methodology

Various artificial targets and the natural vegetated site were measured simultaneously using both a spectrometer and UAS platforms. The measurement sequence began with the spectrometer, followed by UAS imaging, to ensure temporal consistency.

2.4.1. Spectrometer Measurement

The USGS EROS ECCOE team used a dual-spectrometer approach to measure surface reflectance of the artificial calibration targets and the vegetated site. Each spectrometer was paired with a calibrated white reference panel [

29]. One spectrometer was stationary and continuously measured downwelling irradiance throughout the field campaign. The second spectrometer was mobile and was used to measure the reflectance of targets and the site at various locations.

Each field session began with measurements of the fixed reference calibration panel, followed by measurements from the mobile reference calibration panel. After establishing baseline irradiance conditions, the mobile spectrometer was used to measure the artificial targets and subsequently the vegetative target. The vegetated site was sampled following the walking path shown by the red lines in

Figure 1a. To maintain calibration accuracy, the mobile spectrometer was redirected to the reference panel approximately every five minutes during both artificial and natural target measurements.

2.4.2. UAS Measurement Sequence

Low-altitude UAS flights were conducted by the NUSO at the EROS Center in Sioux Falls, SD. To enable UAS positional post-processing corrections, a Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) base station was run throughout the day of data collection. Survey control was established using 12 AeroPoint smart targets (Propeller, Sydney, Australia) as temporary ground control points (GCPs) distributed across the vegetated field prior to mapping [

30].

A DJI Matrice 600 Pro (M600, SZ DJI Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) hexacopter UAS with approved government edition firmware carrying a MicaSense RedEdge-MX Dual sensor was flown at an altitude of 62 m (200 feet) above ground level with an automatic exposure setting. At this flight altitude, MicaSense multispectral images had a ground sample distance (GSD) and swath of ~3.8 cm and 24.46 m, respectively. A MicaSense-provided calibration panel (serial number RP06-2210452-OB) was imaged before and after each UAS flight as recommended by MicaSense. A downwelling light sensor (DLS 2, also known as a sun sensor) that came with the MicaSense Dual configuration was secured to the top of the UAS to capture incident illumination data.

Headwall Nano-Hyperspec hyperspectral UAS flights were flown using a second M600 aircraft at an altitude of 62 m (200 ft) above ground level. The hyperspectral camera was mounted on a gimbal, which compensated for roll, pitch, and yaw movements of the aircraft during flight to maintain a nadir orientation of the camera. At flight altitude, the hyperspectral sensor had a GSD and swath width of ~4.16 cm and 53.20 m, respectively. Sensor exposure was set based on current illumination levels prior to each flight using a white piece of paper to avoid saturation of bright materials.

After setting each sensor’s capture and exposure parameters according to recommendations by their manufacturers, the NUSO remote pilots coordinated their mapping flights with the ECCOE team’s spectral measurements to reduce temporal variability between the ground-based and aerial datasets. By the time the mobile spectrometer operator had performed measuring of the series of artificial targets on the ground, the multispectral UAS data collection began, followed by the hyperspectral UAS data collection within minutes. Both UASs were programmed to follow the same general flight path: first, a single transect was flown from east to west over the row of artificial targets. Then, each aircraft transitioned to flying north–south parallel transects to capture imagery from west to east across the vegetated field, similar to the pattern walked by the mobile spectrometer operator illustrated in

Figure 1a.

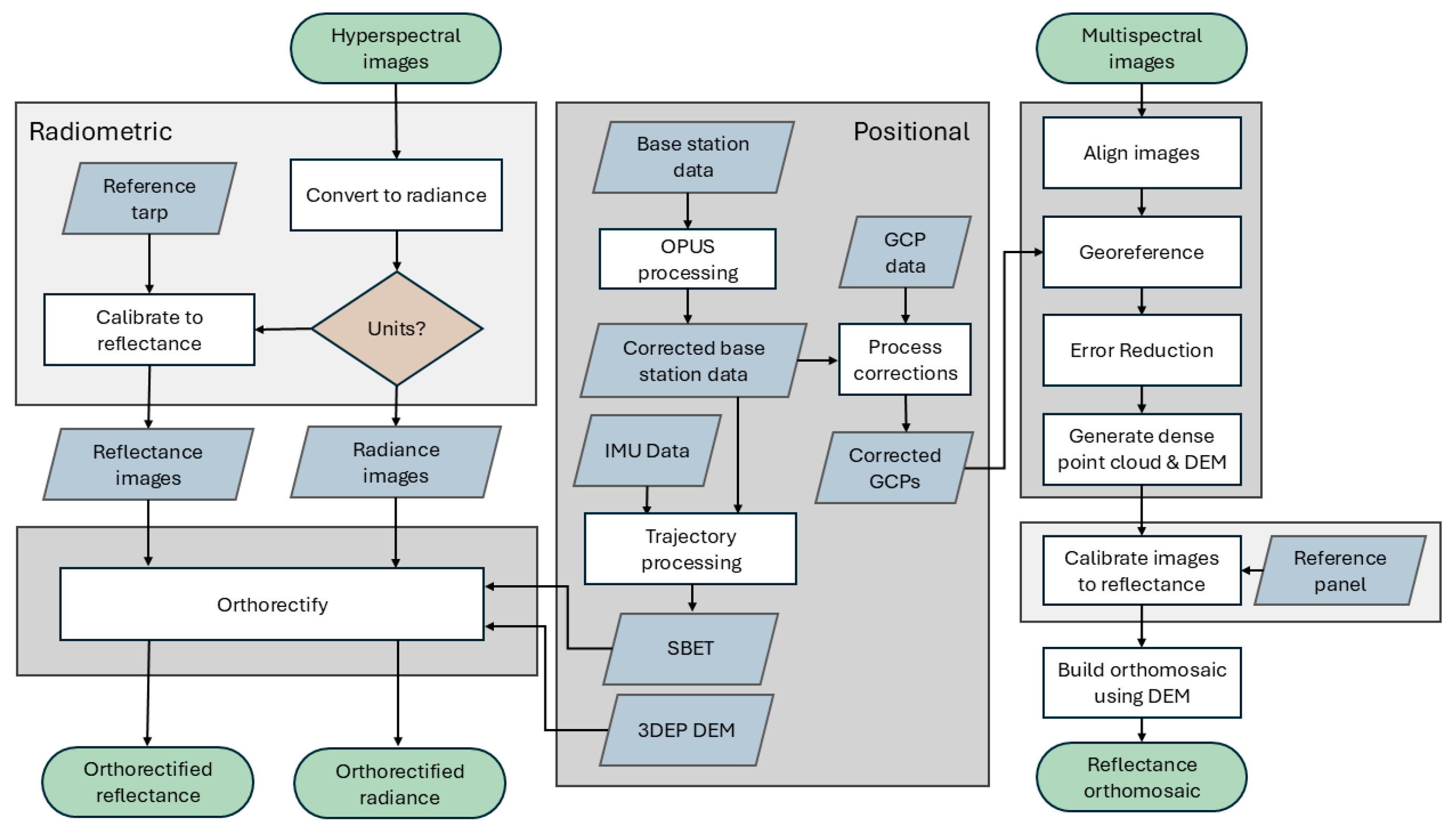

2.5. Data Processing and Manufacturer Recommendation Calibration Workflows

This section describes the processing steps applied to the hyperspectral and multispectral data, summarized in

Figure 3.

2.5.1. UAS Hyperspectral Data Processing

The hyperspectral images were post-processed using the sensor manufacturer’s proprietary software following their recommended workflow, as summarized in this section.

Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) base station data was post-processed using the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Online Positioning User Service (OPUS) to refine its positional accuracy. The Headwall Nano-Hyperspec sensor was flown with an integrated Applanix APX-15 (Trimble Applanix, Richmond Hill, ON, Canada) high-resolution GNSS-Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) to record the sensor’s spatial position and orientation throughout each UAS flight. The trajectory data files from the IMU were post-processed using the OPUS-corrected base station data in Applanix POSPac UAV software. This processing produced a Smoothed Best Estimate of Trajectory (SBET) file, which was subsequently used in the orthorectification of the hyperspectral imagery.

Raw hyperspectral imagery was imported into Headwall SpectralView software and converted to radiance units (mW/(cm2·sr·μm)) using a radiometric calibration file provided by the manufacturer, along with dark reference data acquired immediately before each flight. Reflectance conversion was then performed using a light gray fabric tarp with an approximate reflectance of 56%. The Spectral Angle Mapper tool in SpectralView was used to select 100 representative pixels from within the tarp region. These pixels were related to a reference spectrum corresponding to the tarp’s known reflectance. The derived calibration relationship was applied for each spectral band across the entire image to scale pixel values to units of reflectance (ranging from 0.0 to 1.0).

Reflectance-calibrated hyperspectral images were orthorectified to correct for geometric distortions introduced by aircraft motion and terrain displacement. This process utilized the SBET file created in

Section 2.5 from the GNSS-inertial solution system and a 1 m digital elevation model (DEM) raster downloaded from the USGS 3D Elevation Program (3DEP) lidar explorer [

31]. The orthorectification was performed in SpectralView’s Ortho-Rectification tool, with parameters manually optimized to maximize spatial alignment between images.

These processing steps yielded a series of hyperspectral images, each with 274 spectral bands spanning the visible and near-infrared wavelengths.

2.5.2. UAS Multispectral Data Processing

The MicaSense images were post-processed in photogrammetry software following the manufacturer’s recommended workflow, as summarized in this section.

A separate project was created in Agisoft Metashape Professional software to generate structure-from-motion (SfM) data products from the multispectral images using a standard workflow [

32]. After importing and aligning photos, an initial optimization or bundle adjustment was performed to refine the estimated positions and orientations of the cameras within the photogrammetry project.

Ref. [

30] GCPs were post-processed using corrections from the concurrently operating GNSS base station and imported into the photogrammetry project as markers for georeferencing the multispectral data products. The GCP locations were manually refined to match the center of each checkered target within images.

The point cloud (also known as tie points, resulting from the photo alignment and optimization) was edited using an iterative error reduction procedure to filter the data and delete points with high errors based on user-defined thresholds. Next, a dense cloud was generated using the remaining tie points, followed by DEM generation with interpolation enabled. These structural SfM data products capture topographic variation and elevations across the scene.

Radiometric calibration of MicaSense camera converts the sensor raw values to absolute spectral radiance with a unit of W/

/Sr/nm using Equation (1). This process compensates for a range of sensor and imaging conditions such as sensor black-level, sensitivity, gain and exposure setting, and lens vignette effects. All of these parameters in the model can be read from metadata embedded within the image files [

33].

where

p is the normalized raw pixel value.

is the normalized black level value.

are the radiometric calibration coefficients.

is the vignette polynomial function for pixel (

x,

y).

is the image exposure time.

is the sensor gain setting.

are the pixel column and row number. L is the spectral radiance in W/

/Sr/nm.

Using photos containing the MicaSense calibration panel (acting as a reference with known reflectance values), the images captured at flight altitude were calibrated to reflectance units using the “Calibrate Reflectance” tool in Metashape, following MicaSense processing guidelines. The calibration was performed both with and without the sun sensor data, and the impact of the sun sensor on the resulting reflectance values within the reference tarps was assessed. Enabling the sun sensor parameter led to more variable and less accurate reflectance values across the day, so we decided to leave this parameter unchecked and exclude the sun sensor data in subsequent analysis.

An orthomosaic was generated using the resulting 16-bit reflectance images and the DEM surface. Multispectral bands 1 through 10 of the orthomosaic were divided by a scale factor of 32,768 using the Raster Calculator tool to yield a 10-band reflectance raster product with values between 0 and 1, where 1 indicates 100% reflectance [

31]. These processing steps yielded a 10-band multispectral reflectance orthomosaic for each flight.

2.6. Implementing the Empirical Line Method (ELM)

The ELM was used to generate reflectance products from both the hyperspectral and multispectral sensors using independent calibration sources. ELM is one of the most widely used radiometric calibration techniques for UAS imagery due to its simplicity, effectiveness, and ease of implementation in the field [

12].

ELM does not require detailed knowledge of atmospheric conditions, such as diffuse skylight or adjacent radiance. Furthermore, ELM does not depend on a calibrated sensor or fixed sun-sensor geometry, making it applicable across various platforms, including airborne and satellite-based sensors [

34,

35,

36,

37]. In this approach, an uncalibrated sensor first images known reflectance targets and then images the area of interest. ELM assumes the presence of one or more calibration targets in the imagery that span a broad range of reflectance values across the sensor’s spectral bands. These known reflectance values within the imagery are then used to derive a calibration relationship which is applied to convert image data to reflectance.

Although ELM can technically be implemented with a single calibration target, prior research has shown that using two targets—one dark and one bright—significantly reduces calibration error [

38]. Despite its simplicity, the ELM has critical nuances. For example, it is essential to select calibration targets that cover the reflectance range of the scene. In addition, thorough spectral characterization of the targets is crucial to avoid inaccuracies [

12].

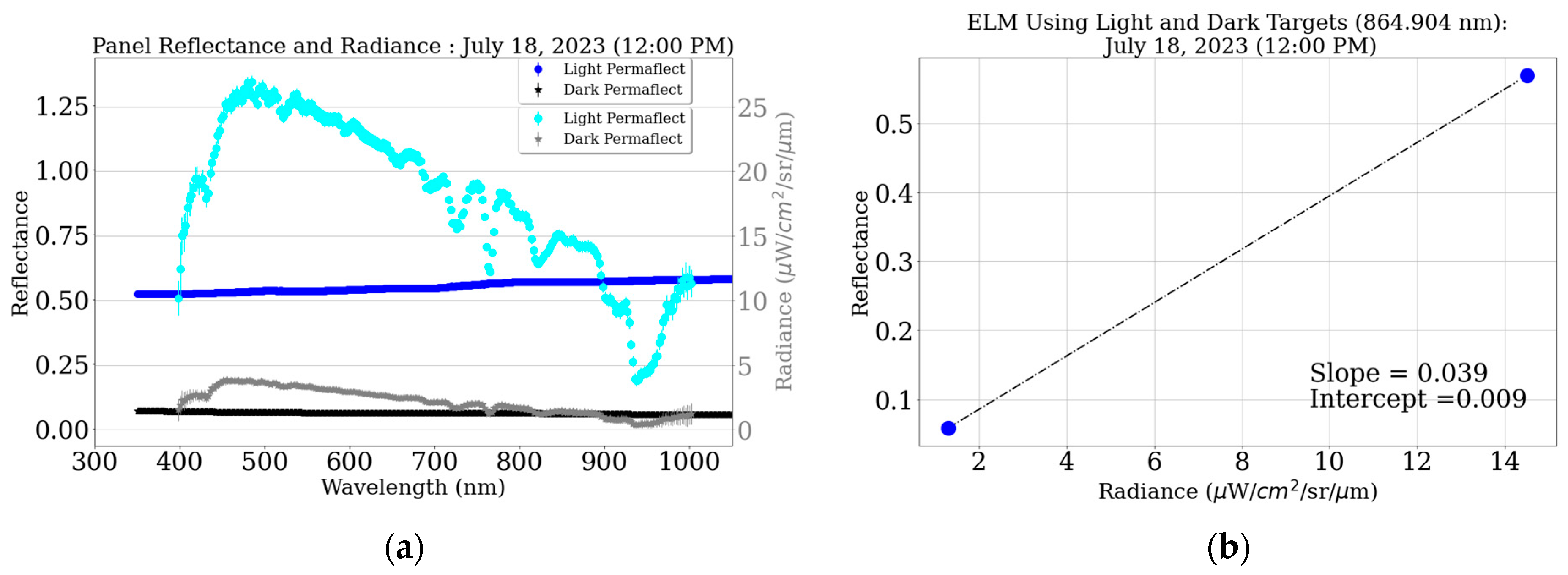

In this study, ELM was implemented using two reference targets per scene, one bright and one dark, to ensure coverage of the reflectance range within the scene, as shown in

Figure 4a.

Figure 4a shows reflectance and radiance for bright and dark Permaflect calibration targets. The blue and black lines represent the spectrometer-based reflectance measurements of the bright and dark Permaflect materials, respectively, while the cyan and gray lines show the corresponding radiance measurements from the UAS hyperspectral sensor. UAS data were extracted using regions of interest (ROIs) that were manually selected for each target to include only pure pixels and exclude edge pixels, which may be affected by adjacency effects or the point spread function (PSF) of the sensor [

17,

39].

Calibration coefficients (slope and intercept) were calculated by performing a linear regression between the UAS sensor measurements (radiance for Headwall, reflectance for MicaSense) and in situ spectrometer-based reflectance measurements, as shown in

Figure 4b. These calibration coefficients convert the hyperspectral radiance product to a reflectance and radiometrically normalized MicaSense reflectance product. Radiance and reflectance products were used instead of digital numbers because they were generated using manufacturer-recommended software, and hence, intrinsic hardware-related adjustments such as lens distortion and vignetting correction were applied within the software.

4. Discussion

This section discusses inconsistencies in UAS hyperspectral sensor data caused by gimbal malfunctions, as well as saturation issues in UAS multispectral data resulting from the sensor’s automatic exposure settings. The importance of stable atmospheric conditions during UAS field campaigns is also discussed because fluctuations can adversely affect image calibration and overall data quality. This section also discusses the impact of target specification and quantity on radiometric calibration of UAS sensors.

4.1. Headwall Nano-Hyperspec Hyperspectral Sensor

The Headwall UAS hyperspectral sensor underestimated surface reflectance over the vegetative site, as shown in

Figure 5. This underestimation is attributed to inaccurate calibration of the reflectance targets. Specifically, the spectral profile of the calibration target provided by the sensor manufacturer appears darker than in situ measurements, as illustrated in

Figure 6. This discrepancy in the target’s spectral profile propagates into the reflectance product, reducing its accuracy.

To address sensor underestimation of surface reflectance, the Empirical Line Method (ELM) was implemented using in situ measurements of the calibration targets instead of the manufacturer’s provided spectral profile. As a result, the reflectance profile of the vegetative target, derived from the Headwall sensor, showed improved agreement with in situ site measurements (

Figure 7). This finding emphasizes that the accuracy of reflectance products using ELM is highly dependent on the precise characterization of the calibration targets. To ensure the quality of UAS-derived reflectance products, it is essential either to regularly calibrate the reference targets or to perform in situ measurements during UAS data collection.

The application of ELM significantly improved the quality of the hyperspectral reflectance data, reducing the average absolute difference to within 0.005 when compared with in situ measurements. This level of accuracy suggests that the Headwall Nano-Hyperspec sensor, when properly calibrated, has strong potential for validating satellite-based surface reflectance products from well-calibrated platforms such as Landsat and Sentinel.

The following subsections address the gimbal issue encountered during one of the data collections and also discuss the adverse impacts of atmospheric conditions on calibrating UAS imagery.

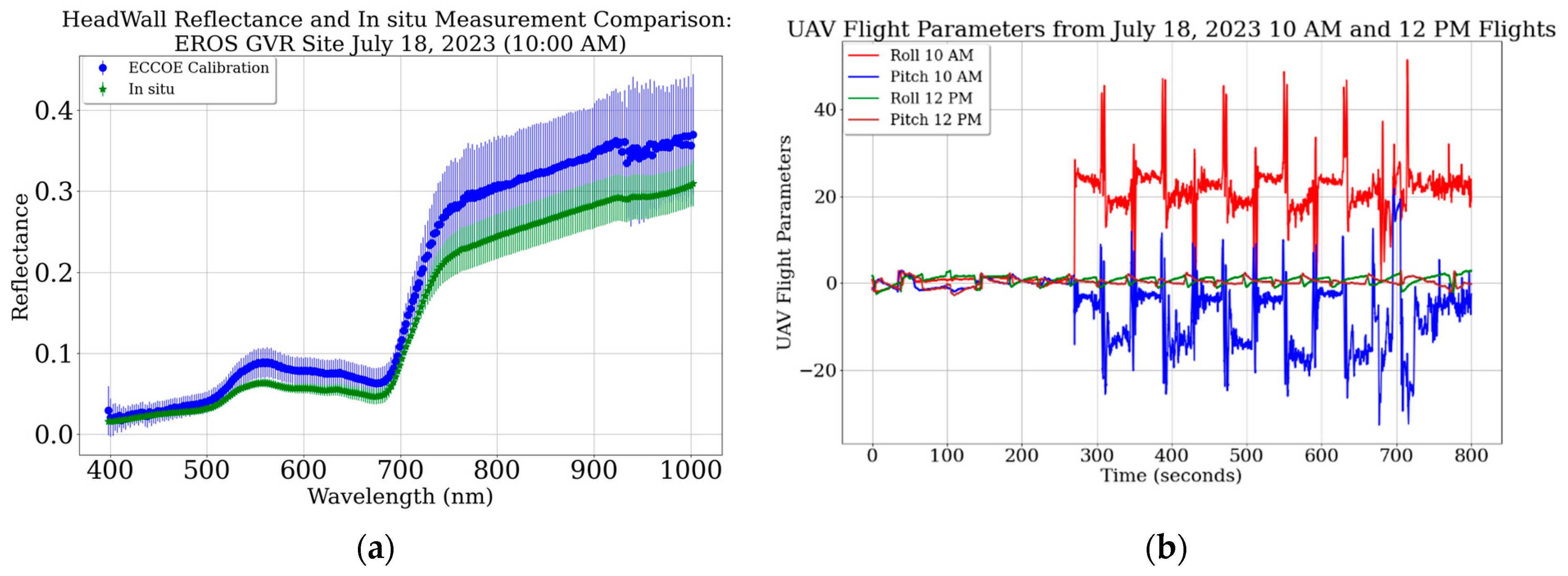

4.1.1. 18 July, 10 AM Gimbal Issue

Figure 13a shows a comparison between the UAS hyperspectral reflectance and in situ measurements. Blue symbols represent the UAS hyperspectral profile of the site, whereas green symbols represent coincident in situ measurements. Despite the stable atmospheric conditions during the flight, the Nano Spec hyperspectral profile shows a significant discrepancy compared to the in situ measurements, as shown in

Figure 13a. The observed discrepancy is larger than the one attributed to calibration issues shown in

Figure 5. One potential source for the observed discrepancy might be sensor orientation during the flight.

The hyperspectral sensor was mounted to the UAS using a gimbal, which compensates for roll, pitch, and yaw movements of the aircraft during flight and maintains a nadir orientation of the sensor.

Figure 13b plots the pitch and roll angles recorded during the flights on 18 July 2023, at 10 AM and 12 PM, to better understand sensor alignment. The yaw angle is not plotted, as it remained similar across both flights. In the plot, the red and blue curves represent roll and pitch angles from the 10 AM flight, while the green and brown curves represent angles from the 12 PM flight. During the initial ~280 s of the flights, the roll and pitch angles from both flights remain near nadir and are relatively similar. After that point, the roll and pitch angles from the 10 AM flight increase for an unknown reason, while those from the 12 PM flight remain near nadir for the remainder of the flight. Specifically, the roll angle during the 10 AM flight changes from approximately 0° to 50°, staying around 20° for most of the remaining time. The pitch angle ranges from −30° to 20°, fluctuating mostly between approximately −4° and −15°.

To investigate whether the discrepancy observed in

Figure 13a can be attributed to sensor misalignment during the 10 AM flight, only the Headwall Nano-Hyperspec data collected under near-nadir roll and pitch angles were considered for comparison with in situ measurements. There were only two UAS hyperspectral images that include the EROS GVR site vegetated area and were captured with near-nadir alignment. These images were located on the west side of the site and include the first two transects of the in situ measurements, as shown in

Figure 1. UAS hyperspectral reflectance values were extracted using a subset of the EROS GVR site ROI and compared with average in situ measurements from the first two transects, as shown in

Figure 14. In

Figure 14, the blue curve represents UAS hyperspectral reflectance, and the green curve represents coincident in situ measurements. The UAS hyperspectral reflectance closely agrees with the in situ measurements. The reflectance values match within 0.005 for most wavelengths, with a slightly larger discrepancy of up to 0.013 observed around ~450 nm and wavelengths greater than 930 nm.

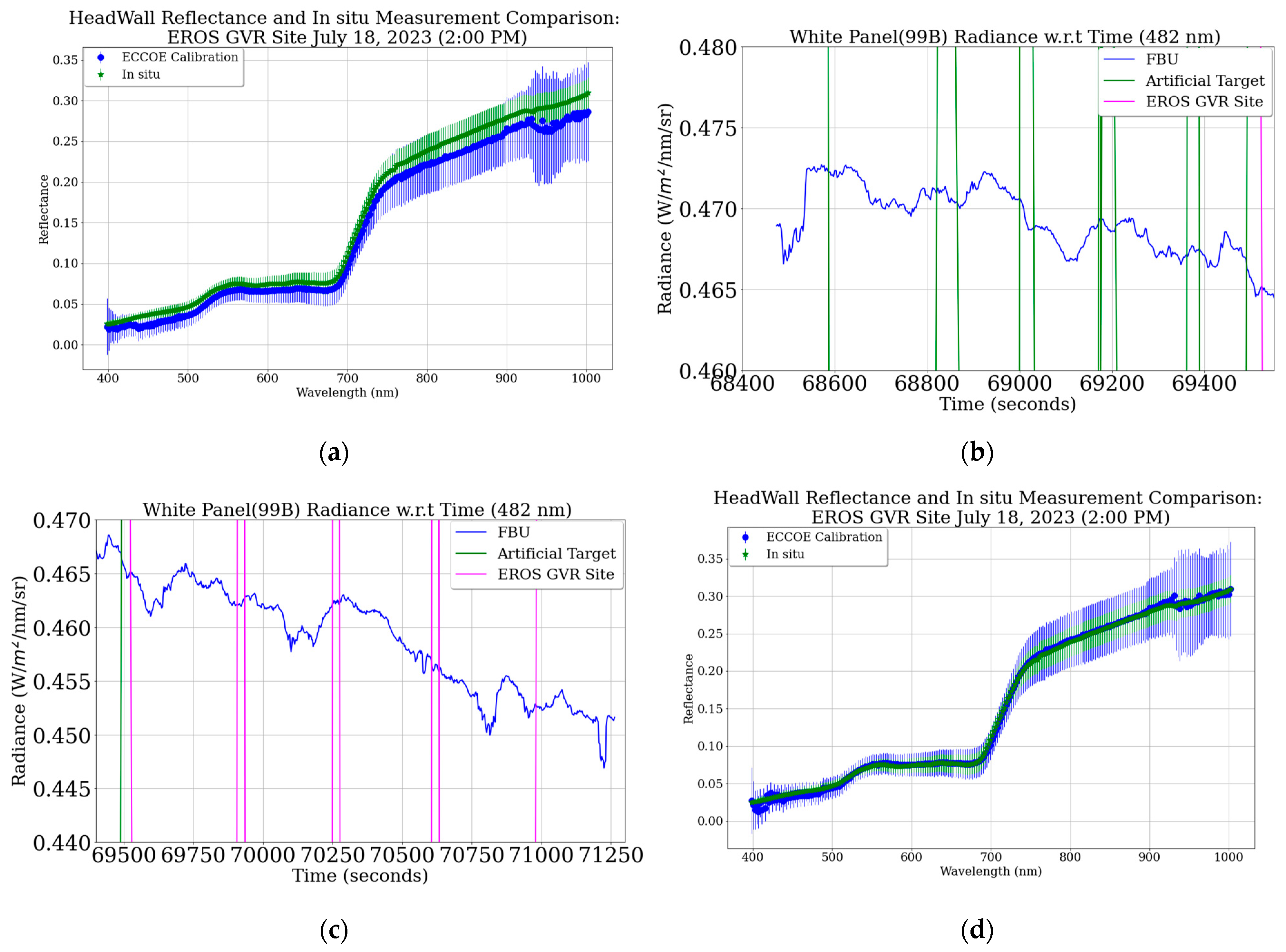

4.1.2. Significance of Atmosphere Stability

Atmospheric conditions represent one of the most challenging variables during field-based remote sensing campaigns. Maintaining stable atmospheric conditions throughout data acquisition is critical, particularly when sampling calibration targets and the EROS GVR site. Discrepancies in atmospheric conditions between these measurements can introduce errors during the empirical line method (ELM) implementation, as illustrated in

Figure 15a. In this figure, the green and blue curves represent in situ measurements and ELM-derived reflectance using Permaflect targets, respectively. The observed differences are likely the result of atmospheric inconsistencies between calibration and target site measurements.

To monitor atmospheric behavior during the campaign, one field spectrometer was directed at a spectral calibration panel to record downwelling irradiance. This information is visualized in

Figure 15b,c, where the blue curves show downwelling irradiance measured during calibration target sampling and EROS GVR site sampling, respectively. Under clear-sky conditions, downwelling irradiance is expected to decrease monotonically over time as the solar zenith angle increases with the lowering sun. However,

Figure 15b,c exhibit intermittent dips and spikes in irradiance caused by transient cloud cover and variable aerosol scattering and absorption. Notably, Permaflect targets were measured after 69,400 UTC seconds, during a period characterized by a spike in downwelling irradiance. This timing likely contributed to the atmospheric inconsistency that caused the discrepancy observed in

Figure 15a. Similar discrepancies were observed with other calibration targets—except for the fabric tarps.

Figure 15d presents a comparison between UAS hyperspectral reflectance over the EROS GVR site and corresponding in situ measurements. The difference between the two datasets remains within 0.005 reflectance units across most wavelengths. The close agreement is likely due to the relatively stable atmospheric conditions at the time of fabric tarp target measurement, around 68,620 UTC seconds, compared to other target measurements.

4.2. MicaSense Sensor

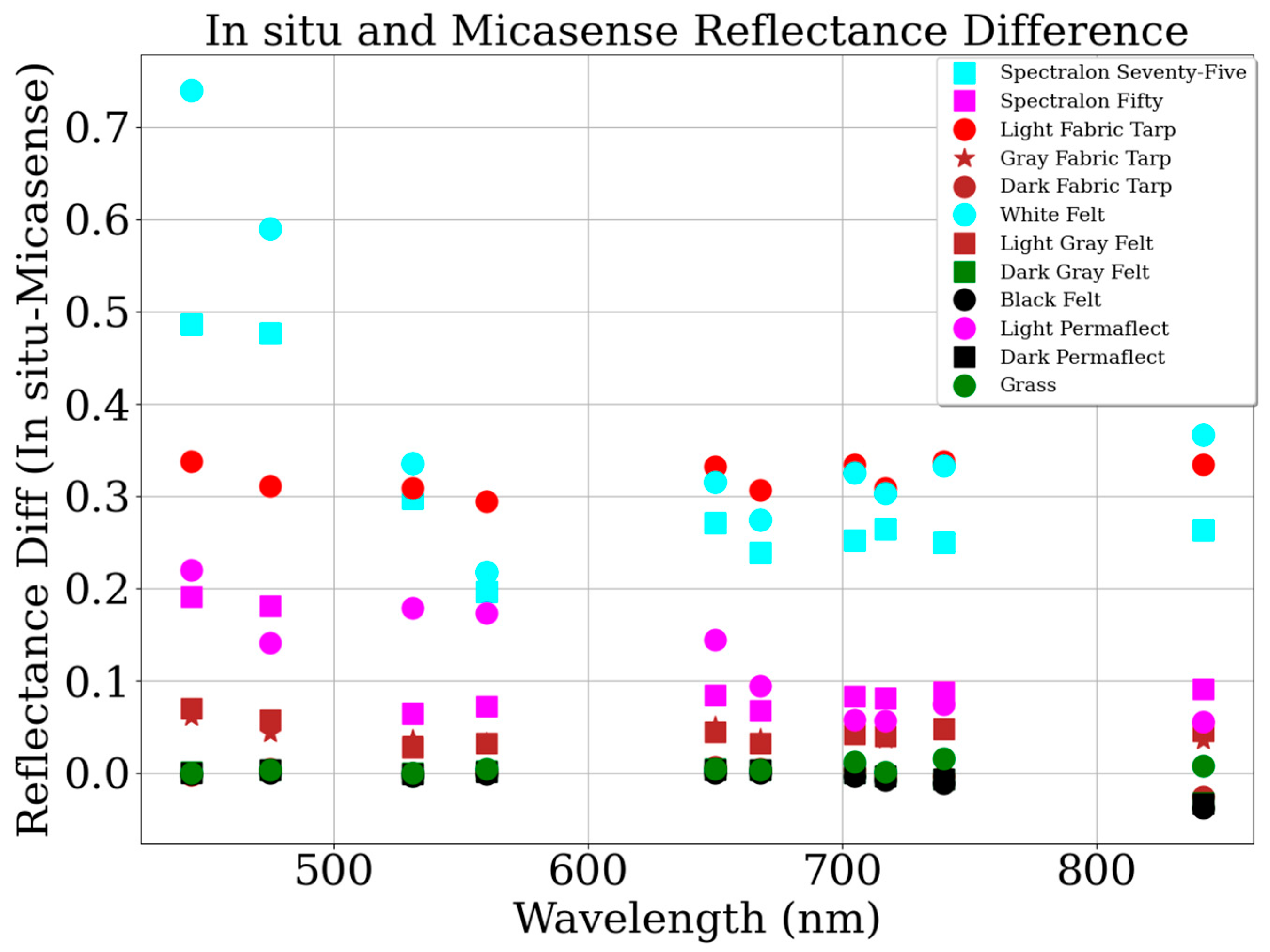

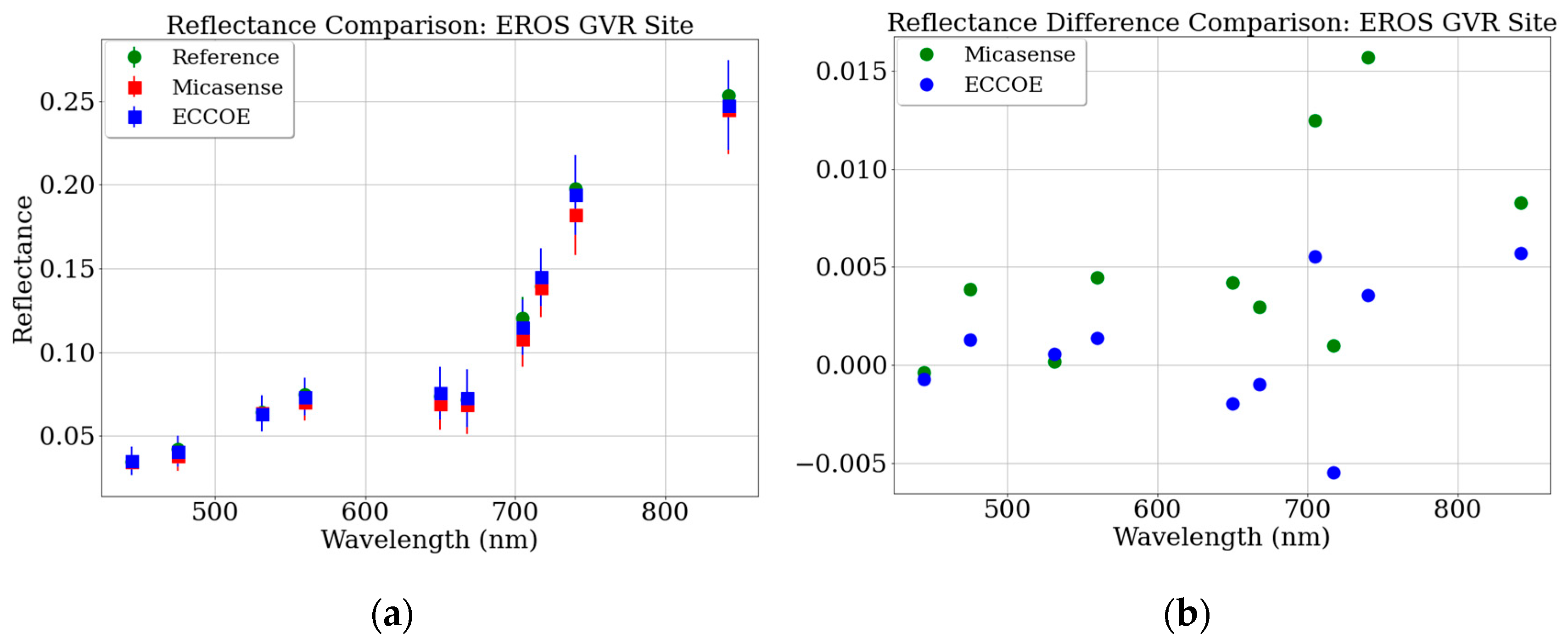

The MicaSense sensor demonstrates superior absolute calibration accuracy compared to the Headwall hyperspectral sensor. As illustrated in

Figure 10a, MicaSense shows the best agreement with vegetation surface reflectance in comparison to artificial targets. For wavelengths below 700 nm, MicaSense sensor reflectance measurements agree with in situ data within 0.005 reflectance units, and within 0.015 units for wavelengths above 700 nm. Application of the ELM further enhances this performance, reducing discrepancies to within 0.005 across all bands. However, despite this improvement,

Figure 10b reveals that reflectance differences can reach up to 0.20 in certain cases, particularly for bright targets.

A comparative analysis indicates that MicaSense performs more reliably on darker targets than brighter ones. The sensor shows strong agreement with in situ measurements for surfaces with reflectance between 30 and 40% or lower but tends to saturate for targets exceeding this range. This suggests a bias in sensor response toward darker surfaces—likely a result of its design intent to support agricultural professionals, where typical vegetative reflectance falls within the 30–40% range [

6].

To better understand this limitation, digital number (DN) statistics were analyzed for a range of calibration targets (

Table 4). MicaSense is a 16-bit sensor, producing DNs between 0 and 65,535. The sensor saturated when imaging highly reflective targets, such as Spectralon 75%, Spectralon 50%, and the light fabric tarp targets. The gray fabric tarp target (38% reflectance) exhibited a mean DN of 65,140.87—close to the upper boundary of the sensor’s dynamic range—while the dark fabric tarp target (5% reflectance) produced a mean DN of 28,032.66, positioned near the middle of the range. These results indicate that the sensor’s automatic exposure and gain control are insufficiently responsive to bright targets, leading to overexposure. Similar findings have been reported in prior studies [

17].

This behavior may indicate an intentional design trade-off: the sensor’s auto-exposure settings appear optimized to fully utilize the dynamic range when imaging targets with reflectance in the 30–40% range, typical of vegetative surfaces. This maximization of radiometric resolution within the expected reflectance range enhances performance for agricultural applications, which aligns with the sensor’s intended use.

The manufacturer’s calibration method uses a 50% reflective panel with a surface area of 10.16 cm × 10.16 cm. Despite this relatively bright calibration reference, the resulting reflectance profiles for vegetative surfaces still match in situ measurements within 0.015 reflectance units, indicating reasonably robust calibration under typical field conditions.

4.3. Target Specification

One of the main objectives of this research was to assess target material, size, and quantity to improve UAS data quality using ELM.

4.3.1. Target Material

Spectralon (polytetrafluoroethylene) targets provide highly diffuse reflectance and possess nearly Lambertian reflective properties [

29,

44]. However, Spectralon panels are expensive and need meticulous care to maintain their calibration, so they might not be a viable option to use as calibration targets for all UAS calibrations and operations. Researchers have used various artificial targets, such as Masonite hardboard, Permaflect, mirrors, concrete, mirrors, and asphalt, as well as natural targets like sand and water bodies to implement the ELM [

17,

37,

45,

46,

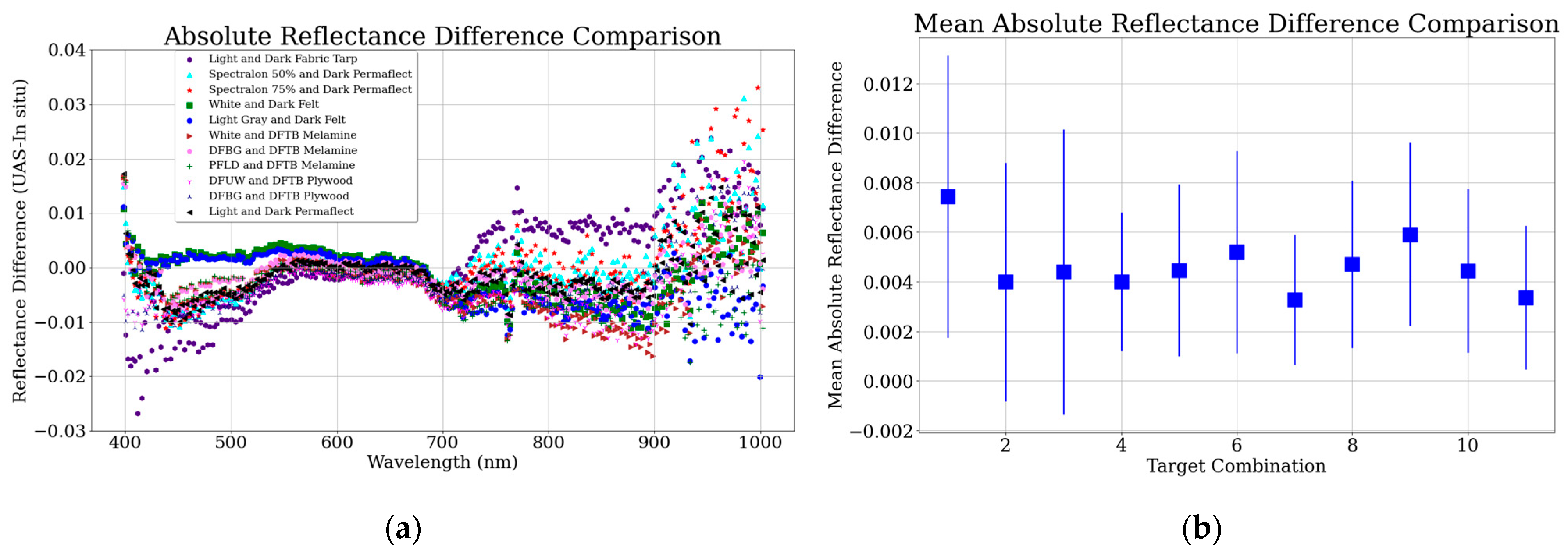

47]. Different types of commercial and homemade targets were used in this experiment. Among the targets used in this experiment, Permaflect is comparatively Lambertian in nature (visual observation). However, the absolute difference between the in situ measurement and UAS hyperspectral reflectance, implementing ELM using different target combinations, is within 0.005 as shown in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7. This suggests that the calibration of UAS imagery using felt, Permaflect, melamine, and plywood gives similar accuracy despite Permaflect being more Lambertian in nature. This might be because the Bidirectional Reflectance Distribution Function (BRDF) is minimum as the acquisition is at noon. Felt and Permaflect targets are lighter than melamine and painted plywood; portability and ease of use for calibration materials are additional factors to consider during UAS operations.

4.3.2. Target Size

Target size in ELM is driven by the ability to obtain pure pixels over a calibration target because any contamination of the spectra of the calibration targets is directly transferred to the retrieved reflectance. Researchers have suggested that the calibration target size should be at least several times greater than the sensor’s ground instantaneous field of view [

12]; others suggest that the side of the square calibration target should be at least 10 times larger than the maximum pixel size [

45]. The dimension of the target is provided in terms of pixel size or sensor ground instantaneous field of view, as pure pixels from the calibration target depend on multiple factors such as flight altitude, point spread function, and adjacency effects.

Four different sizes of targets were used in this experiment: Spectralon panels were 0.3 m × 0.3 m, painted plywood and melamine targets were 0.6 m × 0.6 m, felt targets were 0.9 m × 0.9 m, and Permaflect targets were 1 m × 1 m. The UAS was flown at 200 ft (62 m) above ground level (AGL) which resulted in pixel sizes of 3.8 cm and 4.16 cm for Headwall and MicaSense sensors, respectively. For the Headwall (UAS hyperspectral) imagery, the 75% reflectance panel provided only 9 pure pixels. It was challenging to extract pure pixels from the Spectralon panels because of their smaller size; however, the rest of the targets provided at least 72 pure pixels that could be used to implement ELM. The major factor that impacts the number of pure pixels is the flight altitude of UAS. As described by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) 14 CFR Part 107 rules, the legal upper limit for a small UAS, less than 55 pounds, is 400 ft AGL. Depending on the application, many researchers fly UAS at altitudes of 100–200 ft AGL [

13,

17]. For such users, a calibration target of 0.6 m × 0.6 m should provide enough pure pixels. However, remote pilots conducting higher altitude flights might need 1 m × 1 m calibration targets to comfortably obtain enough pure pixels to implement ELM.

4.3.3. Number of Targets

ELM is one of the common methods to radiometrically calibrate airborne remote sensing data because of its simplicity and effectiveness [

12]. However, users have implemented the ELM using different numbers of calibration targets. Researchers have implemented ELM using one calibration target [

40,

41]; however, most researchers have used two calibration targets of different intensities [

48,

49,

50], and some researchers have used four or more calibration targets to improve calibration [

42,

43]. Researchers using a single-point calibration method for their images have reported 15–20% error. ELM calibration using a single calibration target assumes that a surface with zero reflectance will produce zero radiance. However, in reality, the sensor records additional energy due to diffuse and adjacent radiance which induces an offset that results in inaccurate calibration. To mitigate this issue, researchers have adapted ELM using two calibration targets, one dark and one bright [

12,

37]. ELM using dark calibration targets can include the offset due to diffuse and adjacent radiance by considering dark targets, which are not observed as zero radiance, as “true black” [

34].

This research also used the two-point ELM to account for diffuse and adjacency effects. Additional targets were also used to study where calibration can be improved but found that there is no significant improvement in calibration by increasing the number of calibration targets.

Figure 9a,b show that the slope and intercept of a calibration curve are similar when using two calibration points and 19 calibration points. This is because the sensor response is linear in nature. However, if the sensor response is non-linear, then the number of calibration points would have an impact on calibration accuracy. Wang et al. [

45] showed that their sensor digital number and reflectance are exponential; in this scenario, a greater number of calibration targets would increase calibration accuracy.

Despite using different sizes, types, and numbers of targets to implement the ELM, the experiment generated similar output reflectance spectral profiles which agree with in situ measurement within 0.005 for most wavelengths.

5. Lessons Learned, Limitations, and Future Work

5.1. Lessons Learned

UAS imaging sensor manufacturers’ recommended calibration procedures might not provide the calibration accuracy that their users need. The MicaSense multispectral sensor reflectance agreed with in situ measurements within 0.015 reflectance units, and the Headwall hyperspectral reflectance agreed within 0.08 reflectance units. MicaSense showed better absolute radiometric calibration than the Headwall sensor, so applications that do not need absolute reflectance accuracy better than 0.015, in the case of MicaSense, and 0.08, in the case of Headwall, can go with the manufacturer-recommended protocols. However, the radiometric calibration accuracy can be improved by implementing two-point ELM.

Headwall and MicaSense reflectance differences with in situ measurements decreased to within 0.005 reflectance units by implementing two-point ELM. It was found that adding more calibration targets does not improve radiometric calibration of a sensor if the sensor has a linear response. During two-point ELM implementation, the bright target should be chosen intentionally to utilize the sensor’s dynamic range. The optimal bright calibration target would be a few reflectance units brighter than the brightest reflectance present within the scene to be mapped. For example, if the brightest pixel in an image is 0.4, bright calibration targets with 0.45 reflectance would help fully use the dynamic range of the sensor.

Different target materials provide similar calibration quality. UAS hyperspectral reflectance values were within 0.005 of in situ measurements using felt, melamine, and Permaflect targets. Felt and Permaflect targets are lighter (in weight) than melamine, and target weight is one factor to consider during a field campaign. Another factor to consider while choosing the calibration targets would be diffuse reflectance. Targets producing diffuse reflectance have less directional dependency, which minimizes the impact of illumination angle changes. For UAS flight altitudes within 200 ft AGL, a target size of 0.6 m× 0.6 m is likely to provide enough pure pixels (~100 pixels) to implement ELM.

It is crucial to ensure that gimbals are functioning properly as they stabilize the sensor platform during the flight which directly influences the quality, consistency, and accuracy of the collected imagery.

5.2. Limitation of Field Campaign

The ELM calibration target should be within the stage for implementing ELM, and the time difference between the calibration target measurement with spectrometer and the UAS should be minimal. However, it took ~20 min to sample 19 artificial targets, during which the illumination geometry and atmospheric conditions might have changed slightly, which could have adversely impacted the calibration.

Due to the large number of targets, targets were sampled at the beginning of the experiment before the UAS imaged the site. However, sampling at the end of the experiment as well helps to account for the change in illumination angle and atmospheric conditions. The panels used in the experiment did not have BRDF characterization, which would help to compensate for the change in illumination angle.

5.3. Future Work

Due to the large number of calibration targets, the targets were sampled using a spectrometer only once before each UAS flight. Recommended future studies include downsizing of the number of calibration targets. These targets could be sampled both before and after each UAS flight, and both of these measurements could be used to implement ELM. This could help to minimize calibration errors induced due to changes in illumination and atmospheric conditions. The BRDF of the targets could be characterized to help more accurately estimate the reflectance of the target.

ELM is simple and effective but has its own challenges. Calibration targets are needed and are typically laid out during field UAS data acquisition, which is labor- and cost-intensive. Calibration targets must be kept clean, stored properly, and undamaged to preserve their calibration. However, over time, their calibrations can change due to exposure to sunlight and environmental conditions during the field campaign. To maintain their calibrations, targets should either be measured frequently in a calibration laboratory or measured during the field campaign using a calibrated source. To mitigate the dependency on calibration targets, researchers have also used downwelling irradiance to calculate surface reflectance [

51]. Downwelling irradiance can be modeled using atmospheric radiative transfer models [

52] or measured using a downwelling irradiance sensor [

14]. MicaSense and other multispectral sensor types come with downwelling irradiance sensors, although their inclusion in the radiometric calibration workflow can have variable effects on the output surface reflectance.

Future UAS field campaigns could be conducted with coincident satellite observations. UAS surface reflectance could be compared with satellite surface reflectance measurements and in situ measurements to help understand the potential of UAS for validating satellite surface reflectance products in an operational manner.

6. Conclusions

This study aimed to evaluate the absolute calibration of the Headwall Nano-Hyperspec hyperspectral sensor and the MicaSense RedEdge-MX Dual multispectral imaging system. ELM was implemented to calibrate the imagery from these sensors, with results compared against in situ measurements. This analysis assessed the impact of ELM on improving data quality. This study also examined the influence of target specifications such as size, material, and intensity on calibration outcomes.

The absolute calibration of hyperspectral and multispectral sensors was assessed by comparing their reflectance, obtained using manufacturer-recommended procedures, with in situ measurements of a vegetated target. Results showed that the UAS hyperspectral sensor underestimated the target’s reflectance by approximately 0.05. This discrepancy was attributed to inaccuracies in the spectral profiles of the fabric tarp calibration targets provided by the sensor manufacturer at the time of purchase, which were darker than the in situ reflectance measurements obtained during the field campaign. Consequently, this discrepancy was propagated into the UAS hyperspectral reflectance product. However, when the Headwall radiance product was converted to a reflectance product using the Empirical Line Method (ELM), the discrepancy was reduced to within 0.005.

The MicaSense sensor exhibited a difference of approximately 0.015 compared to in situ measurements, which decreased to within 0.005 after implementing the ELM. While the MicaSense sensor calibration was accurate for vegetated targets, substantial reflectance discrepancies were observed for targets with reflectance values exceeding ~0.40. This issue arose because the sensor’s automatic settings failed to adjust gain and exposure time adequately for high-intensity targets, leading to saturation.

Applying the ELM using one dark and one bright target improved the data quality of both sensors in this study. However, adding more calibration targets did not necessarily enhance calibration accuracy. For a UAS flight altitude above ground level (AGL) of 200 ft, a target size of 0.6 m × 0.6 m or larger provided sufficient pure pixels for implementing ELM with the Headwall and MicaSense sensors, whereas smaller targets (e.g., 0.3 m × 0.3 m) made identifying pure pixels challenging. ELM results using felt, Permaflect, and melamine calibration targets showed comparable outcomes.

Both the Headwall Nano-Hyperspec hyperspectral sensor and the MicaSense RedEdge-MX Dual Camera imaging system multispectral sensor have limitations in accurately predicting reflectance. Absolute calibration accuracy was higher for the MicaSense sensor compared to the Headwall sensor. Users should be aware of these limitations when utilizing the data for various applications. Nonetheless, ELM significantly enhances data quality and improves the reliability of these sensors for remote sensing applications.