1. Introduction

Avalanches are sudden mass movements of snow that occur when accumulated snow exceeds the shear strength of the underlying layers, often leading to catastrophic collapse [

1]. As one of the most hazardous natural phenomena in cold regions, avalanches pose serious threats to human life, infrastructure, and regional development, particularly when they occur near human facilities such as roads, villages, tunnels, and waterways. Southeastern Tibet is the area in China with the highest frequency of avalanche events, owing to its steep terrain and complex meteorological conditions [

2]. In recent years, the impacts of global climate change and intensive infrastructure development have led to increasingly dynamic and heterogeneous snowpack structures and geological conditions in this region. Consequently, both the frequency and intensity of avalanches are rising, placing growing pressure on transportation corridors, logistics operations, and the safety of local communities [

3,

4]. For example, a deadly avalanche at Duoxiongla tunnel on the Paimo Highway in January 2023 resulted in 28 fatalities, while a series of avalanches along the Bomo Highway in March 2025 left over a hundred people stranded [

5].

Previous studies in southeastern Tibet have provided important insights into avalanche behavior under complex climatic and topographic settings. Gao et al. [

6] analyzed the spatiotemporal variability of snow cover and its response to climate change, revealing elevation-dependent trends where snow-free periods extend at lower elevations but shorten at higher ones. Wen et al. [

7] examined channeled avalanche activity in the Parlung Tsangpo catchment, identifying typical runout altitudes between 3468 m and 4051 m, with peak occurrences from February to April. In addition, other studies have proposed threshold conditions for avalanche initiation by establishing intensity–duration relationships for extreme snowfall events that trigger regional avalanches [

4]. Together, these findings underline the distinctive avalanche regime of southeastern Tibet, shaped by its maritime snow climate and rugged mountain terrain.

However, existing avalanche monitoring approaches primarily rely on satellite remote sensing and meteorological forecasts, which are typically retrospective and limited in spatial and temporal resolution [

8,

9,

10,

11]. These methods are insufficient for providing timely and site-specific warnings, particularly in high-relief, data-sparse environments such as southeastern Tibet. Since avalanche initiation is closely linked to the mechanical failure of buried weak layers within the snowpack, reliable early warning depends on the ability to assess internal snowpack stability. There is therefore an urgent need to develop methods capable of detecting key subsurface parameters in real time and with sufficient resolution to support accurate avalanche risk forecasting in high-risk alpine environments.

At present, snowpack stability is typically assessed through in situ methods such as snow pit excavation and the deployment of sensors, including time domain reflectometers (TDR) [

12,

13] and low-frequency dielectric probes [

14,

15]. These techniques enable monitoring of snow stratigraphy and the spatiotemporal evolution of key physical parameters. In recent years, Ground-Penetrating Radar (GPR) has gained increasing attention due to its ability to non-invasively capture internal snowpack structures with adequate penetration depth and mobility [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. However, in high-altitude and topographically complex regions such as southeastern Tibet, ground-based surveys present significant logistical and safety challenges. Conducting field operations in avalanche terrain is not only hazardous and time-consuming but also costly, and these limitations hinder the spatial coverage of monitoring, leaving large portions of the landscape under-monitored.

Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV)-based remote sensing offers a promising alternative for wide-area, high-resolution snowpack assessment. UAV platforms have been used to deploy various sensors, including infrared cameras [

21,

22], synthetic aperture radar (SAR) [

23,

24], GPR [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29], and LiDAR [

30,

31], to investigate snow distribution, depth, surface temperature, and internal structure. These approaches have demonstrated significant potential in alpine environments. Despite these advances, there have been no reported successful applications of UAV-mounted snow sensing systems in China, particularly for avalanche monitoring in high-risk regions such as southeastern Tibet. Major challenges are listed as follows:

- (1)

The high elevations of the mountainous terrain in southwestern Tibet significantly constrain UAV flight performance. Extended ascent durations and reduced air density increase energy consumption and limit battery life. To ensure operational efficiency, the snow-sensing payload must be lightweight and capable of remote control. Sensor types and combinations must be carefully selected to remain within the UAV’s payload capacity while still capturing key snowpack parameters.

- (2)

When using UAV-mounted GPR to investigate internal snowpack properties, the steep terrain and UAV vibration generate considerable clutter and signal distortion. These effects reduce the clarity of subsurface reflections and hinder reliable detection of internal snow layers. To improve data quality, advanced and targeted signal-processing techniques are required. In addition, the quantitative relationship between snow properties and radar attributes remains poorly defined, which limits the accuracy and consistency of snowpack property inversion from GPR data.

- (3)

Avalanche-prone areas in southeastern Tibet are influenced by a warm, humid maritime periglacial climate, with greater precipitation and higher temperatures than typical cold-region environments. These conditions result in complex snow layering and dynamic moisture content, which differ from those assumed in most existing snow failure models. Consequently, the physical indicators of snow instability in this region are not well defined, making it difficult to assess avalanche risk using generalized approaches.

To address these challenges, this study develops a UAV-based snow sensing platform integrating GPR, thermal imaging, and optical sensors, specifically designed for operation in high-altitude and cold environments. The system’s reliability was verified through field experiments under extreme conditions. A case study was then carried out in avalanche terrain in southwestern Tibet, where the system was used to extract key snowpack properties associated with instability. The results provide a practical foundation for improving avalanche hazard assessments and supporting the safe operation of infrastructure in this high-risk region.

2. Related Work

The community have conducted extensive research on the mechanism of snow avalanche, radar-based interpretation of snowpack physical properties, yet few have considered the influence of the unique terrain and climatic conditions of southeastern Tibet. This section briefly reviews the principal theory of snowpack surveys.

2.1. Essential Snowpack Parameters for Avalanche Risk Assessment

According to the widely accepted classification system based on avalanche release mechanisms, avalanches are primarily divided into two fundamental types: loose snow avalanches, which are triggered from a point and develop downward, and slab avalanches, which are released along a linear fracture and slide as a cohesive layer [

1]. These two types have been extensively studied in various regions worldwide, with significant research conducted in Canada [

30,

31], Norway [

32,

33], Switzerland [

34,

35], and Xinjiang, China [

36,

37]. In contrast, based on the topographic characteristics of their movement paths, avalanches can also be categorized into unconfined avalanches, which occur on open slopes, and channeled avalanches, which are constrained by narrow mountain gullies [

32]. Field observations indicate that avalanches on the southeastern Tibetan Plateau predominantly exhibit the characteristics of channeled avalanches, as shown in

Figure 1. Although considerable research explored the mechanism, morphology, and impact of channeled avalanches, there remains a lack of systematic and focused studies on the dynamic features of such avalanches under the unique high-altitude geographical and monsoon climatic conditions of the southeastern Tibetan Plateau. This is largely due to their tendency to occur in sparsely populated, high-altitude regions, where direct observation and monitoring are more difficult.

In southeastern Tibet, channeled avalanches are of particular concern due to the region’s steep topography and complex climatic conditions. The area is strongly influenced by warm, humid monsoonal airflows from the Indian Ocean, resulting in heavy snowfall and frequent freeze–thaw cycles [

33]. These processes lead to highly stratified snowpacks with significant spatial and temporal variability. Temperature gradients promote the development of weak layers within the snowpack, while meltwater and rainfall infiltration further reduce bonding strength between layers. These conditions increase the likelihood of interlayer shear failure and contribute to snowpack instability [

34].

One of the key indicators of snowpack stability in such environments is the snow water equivalent (SWE), which quantifies the total amount of water stored in the snowpack [

35]. SWE is directly influenced by snow depth and density, as in Equation (1):

where

is the measured snow density,

is the layer thickness, and

is the density of water (1000 kg/m

3).

Liquid water content (LWC), all of which affect the snowpack’s mechanical strength and its susceptibility to failure [

36]. In addition to SWE, other parameters such as snow temperature, snow density, and the vertical temperature gradient are also critical. Snow temperature governs the phase state of water within the snowpack and influences bonding strength between layers [

37], while density provides insight into the compaction and layering of the snow [

38]. Together, these indicators help characterize the thermal and mechanical conditions that contribute to the formation of weak layers and potential failure planes. Therefore, reliable avalanche risk assessment in southeastern Tibet requires a comprehensive understanding of how these physical parameters evolve under wet-snow conditions, and how they relate to the onset of channeled avalanche initiation.

2.2. Relationship Between Snowpack Physical Properties and GPR Response

In contrast to parameters such as temperature and density, which can be directly measured using thermometers, infrared thermography, or mass–volume methods, the LWC and SWE of the snowpack must be estimated indirectly. These parameters are commonly inferred from the snow’s dielectric permittivity, which can be inversed non-invasively using GPR data. GPR operates by transmitting electromagnetic waves into the snowpack and detecting the reflected signals from internal layer boundaries. The fundamental physical principle underlying this technique is that the propagation velocity of radar waves within the snow is primarily governed by the dielectric permittivity of the snow medium.

The dielectric permittivity of snow, denoted as

, is not an intrinsic property but rather a composite response determined by the dielectric characteristics and volumetric fractions of its constituent phases—namely ice, air, and liquid water. In dry snow conditions, the effective dielectric permittivity (ε_dry) is predominantly controlled by snow density, which reflects the relative proportions of ice and air. However, when liquid water is present, even in small quantities, it significantly alters the dielectric behavior of the snowpack due to water’s high dielectric constant (~80), compared to that of ice (~3.2). This results in a marked increase in the overall permittivity, affecting both the real part (ε′)—which governs wave velocity—and, more prominently, the imaginary part (ε″)—which contributes to signal attenuation and energy loss [

39]. Consequently, by accurately measuring the two-way travel time or propagation velocity of radar waves through the snow layer, one can infer the real part of the dielectric permittivity. Subsequently, by applying established empirical models,

can be related to key snow properties, including snow density and LWC.

Numerous empirical models have been developed to relate snowpack physical properties to their electromagnetic characteristics. Sihvola et al. [

40] examined the dielectric behavior of snow using multiple theoretical models and evaluated their consistency with experimental observations. These models account for different factors, such as snow phase (wet or dry) [

39,

41,

42], material structure (porous or granular) [

43,

44,

45], and dielectric properties (real and imaginary components of permittivity) [

46,

47]. Specifically, Tiuri et al. [

39] measured the complex dielectric constant of snow at microwave frequencies and found that, in dry snow, it is primarily governed by density, whereas in wet snow, both the real and imaginary components increase with LWC. Denoth et al. [

48] obtained slightly different empirical coefficients for each medium and emphasized that porosity and frequency-dependent losses must be included. Several commercial snow sensors have been introduced to the market, among which the products developed by A2 Photonics [

49] and FPGA Company [

50] are the most widely used. However, the choice of model can have a substantial impact on the accuracy of inversion results. As noted by Pletnev et al. [

51], discrepancies between model predictions can reach up to 40%, highlighting the need to select or calibrate models carefully for specific environmental conditions.

Table 1 presents the abovementioned widely used empirical models and commercial snow sensors, with input parameters that are obtainable under environmental conditions typical of southeastern Tibet.

Table 1.

Widely adopted models of relationship between snow and dielectric properties.

Table 1.

Widely adopted models of relationship between snow and dielectric properties.

| Reference | Equation |

|---|

| Tiuri et al. [39] (TS) | |

| Denoth et al. [48] (Den) | |

| A2 Photonics Sensors [49] | |

| FPGA Company [50] |

|

Therefore, it is necessary to determine a model suited to the unique hydrogeological and climatic conditions of southeastern Tibet, considering factors such as snow thickness and appropriate radar frequencies.

3. UAV-Based Snowpack Stability Sensing System for High-Altitude and Cold Environments

This section presents the proposed UAV-based snowpack sensing system, developed to address the specific operational challenges of high-altitude and cold-region environments. The system is built on a UAV platform capable of maintaining stable flight at high elevations and integrates IRT, GPR, and an optical camera. By optimizing sensor placement and system configuration, the platform overcomes key limitations such as low permissible flight altitude, restricted payload capacity, and sensor field-of-view obstructions.

3.1. UAV Platform and Sensors

The UAV platform selected for this study was the FEIMA D20, chosen for its extended flight endurance and high-altitude adaptability. With a maximum payload capacity of 6 kg, the UAV offers a flight duration of up to 80 min under full load. Equipped with rotary wings and highland-specific propellers, it is capable of stable operation at elevations exceeding 6000 m, which meets the requirements for typical mountainous terrain in southeastern Tibet. The platform is also integrated with a Real-Time Kinematic (RTK) positioning module, allowing for precise recording of flight trajectories and georeferenced data collection. The platform and sensors are shown in

Figure 2a.

For thermal sensing, the system employs the TIRV1100 infrared thermography unit, which features a measurement range from −20 °C to 60 °C and a thermal resolution of 0.1 °C. The sensor is equipped with a 13 mm lens, producing thermal images with a resolution of 640 × 512 pixels. An optical camera is combined with this unit, offering a focal length of 12 mm and a resolution of 20.3 megapixels, enabling simultaneous acquisition of visible and thermal imagery.

The GPR component is a compact, wireless unit integrating the antenna and control module within a shielded housing. The system operates at a center frequency of 400 MHz. The effective penetration depth of a GPR system in wet snow is governed by the medium’s dielectric permittivity, which typically ranges from 3.5 to 15 depending on the liquid water content. Even under high-permittivity conditions, the penetration depth of a 400 MHz system reaches approximately 5 m, sufficient to resolve the full snowpack profile in melting season, where snow thickness ranged from 2.3 m to 3.2 m. However, a lower-frequency system could achieve greater penetration at the cost of reduced spatial resolution. At this frequency, the vertical resolution is approximately one-quarter of the wavelength (~0.19 m), and the horizontal resolution at a depth of 2 m is ~0.45 m, calculated from the first Fresnel zone. Therefore, the 400 MHz frequency represents an appropriate balance between penetration depth and spatial resolution for wet-snow avalanche monitoring. The GPR system has a total weight of approximately 5.4 kg and communicates with the control interface via a Wi-Fi connection, facilitating real-time monitoring and data logging during flight operations.

3.2. Mechanical Stabilization and Obstruction Mitigation Design

While the thermal and optical imaging modules were integrated into a gimbal system for active stabilization, a dedicated mechanical design was implemented for the GPR unit to ensure signal stability during flight. As illustrated in

Figure 2a, the GPR system was mounted beneath the UAV using a custom-designed pendulum structure fabricated from ABS plastic. This material was selected for its mechanical strength and electrical insulation properties, ensuring it did not interfere with radar wave transmission or reception.

As shown in

Figure 2b, the GPR antenna was supported by a tripod structure, with four elastomeric damping elements installed at the connection points. These components served a dual purpose: reinforcing the structural stability of the GPR mount and mitigating the transmission of high-frequency vibrations from the UAV rotors to the radar system. This vibration isolation is critical for preserving signal clarity, particularly when operating at high altitudes where flight-induced turbulence is common.

To maintain a balanced configuration and avoid sensor interference, the GPR antenna was oriented downward and aligned parallel to the tripod base. This arrangement left sufficient space for the thermal and optical sensors, which were mounted at the front of the UAV. Unlike the GPR, the thermal and optical modules were angled approximately 40 degrees upward relative to the vertical. This oblique field of view was chosen to enhance surface observation capabilities in steep mountainous terrain, improving coverage of vertical and sloped snow surfaces while avoiding obstruction from the UAV structure and landing gear. This configuration ensured that all sensors operated within their optimal observation geometries, allowing for effective data acquisition across surface and subsurface domains.

4. Characterization of Avalanche-Prone Snowpack Properties

A case study was carried out in an avalanche-prone region of southeastern Tibet with the self-developed UAV-based snow sensing system. The aim was to characterize key physical properties of instability-prone snowpacks, including SWE, LWC, density, snow temperature, and internal stratigraphy.

4.1. Study Area Specification

To capture snowpack conditions representative of the avalanche season, the case study was conducted in early April, in

Section 4 of G219 that located in Zayü County, Nyingchi City, in southeastern Tibet, China. This region lies on the eastern margin of the Himalayas, within a complex transition zone between the Himalayan Range and the Hengduan Mountains. The topography is characterized by steep terrain, deeply incised river valleys, and strong elevation gradients, ranging from approximately 2000 m to over 5000 m. The landscape features numerous V-shaped valleys and confined gullies, formed through long-term fluvial erosion, which are highly susceptible to channeled-type snow avalanches.

Climatically, the region is one of the wettest areas on the Tibetan Plateau, with annual precipitation exceeding 1000 mm. In winter and spring, heavy snowfall on steep slopes, combined with frequent freeze–thaw cycles, leads to complex snowpack layering and the development of weak interlayers prone to shear failure. The relatively mild winter temperatures for the elevation, together with persistent snow accumulation, result in prolonged snowpack instability at high elevations. Additionally, dense cloud cover and high humidity limit the effectiveness of satellite-based optical monitoring, further necessitating the use of UAV-based sensing systems for ground-focused avalanche assessment.

Importantly, G219 National Highway links Zayü to Mêdog Town, which serves as a strategic border route connecting southeastern Tibet to the China–India boundary region. Two test sites were selected within

Section 4 of the G219 corridor to enable both ground-based validation and UAV-based multi-sensor surveys under realistic field conditions, as shown in

Figure 3. The first site A was established on a relatively flat roadside area that is close to the avalanche area, which provided a stable platform for ground measurements. The second site B was selected on a recently collapsed avalanche slope situated near the road, making it a representative example of instability-prone snowpack conditions.

4.2. Ground-Based Snow Properties Calibration

A snow pit was excavated at ground site to characterize vertical snowpack structure through direct observation and sampling. Measurements of snow temperature, density, and stratigraphy were obtained using conventional probes and sensors to serve as a baseline for validating remote sensing results.

Snow temperature was recorded using a calibrated snow temperature probe or digital thermometer with a precision of 0.1 °C. Measurements were taken at 0.2 m vertical intervals, with the probe inserted horizontally into the pit wall to minimize surface influence. To ensure thermal equilibrium, the probe was allowed to stabilize for several seconds before recording each temperature. These measurements provided vertical temperature gradients essential for assessing thermal stratification and the potential for weak layer formation due to kinetic metamorphism.

Snow density was measured using the mass–volume method, which involved collecting snow samples from each stratigraphic layer using a standard snow cutter with a known 1 × 10

−4 m

3 volume. Each sample was carefully extracted to avoid compaction and then weighed using a portable spring balance or digital scale with an accuracy of ±1 g (as shown in

Figure 4a). The density of each layer was calculated as the ratio of mass to volume, resulting in average 0.49 g/cm

3, allowing for layer-by-layer profiling of snowpack compaction and metamorphism. Afterwards, SWE of each layer was calculated based on Equation (1). Each layer of snow properties measured are presented in

Table 2.

The dielectric permittivity of the wet snowpack was estimated using ground-coupled GPR measurements. Data were collected along the traverse line shown in

Figure 4b using the same antenna configuration as the UAV-based system. This ensured consistency in signal characteristics and eliminated the influence of air gap and flight-related parameters. The radar system was operated with a 150 ns time window and a sampling rate of 512 samples per trace. Standard preprocessing techniques were applied, including de-wow, time-varying gain adjustment, and frequency-domain filtering to suppress noise and enhance reflection clarity. Because the wheel odometer failed in soft snow and no nearby reference station was available for GNSS correction, traverse distances were inferred from trace counts and estimated movement speed. However, irregular movement across the snow surface caused repeated traces when the GPR antenna stopped, leading to errors in distance calculation. To address this, redundant traces were identified and removed by analyzing the correlation between adjacent traces and applying a moving average filter.

Since conventional full waveform inversion (FWI)—which relies on predefined models—is computationally inefficient for large datasets, this study utilized the known snow depth as a constraint to invert radar wave velocity. As illustrated in

Figure 5a, a strong reflection corresponding to the snow–ground interface was observed at approximately 10 ns two-way travel time. The actual snow depth at this location was measured to be 0.53 m using a calibrated leveling rod inserted vertically through the snowpack. Based on these measurements, the dielectric permittivity was calculated using Equation (2):

where

is the snow thickness,

is the radar wave velocity in snow,

is the two-way travel time,

is the speed of light in vacuum, and

is the relative dielectric permittivity of snow.

The entire process was repeated three times along adjacent traverse lines, and the average result was calculated. Using the measured depth and travel time, the radar wave velocity in snow was estimated as 0.15 m/ns, corresponding to a dielectric permittivity of approximately 4.6. This value is consistent with typical ranges for wet, low-density snow, confirming the presence of significant LWC within the snowpack at the test site.

Based on the LWC estimation models listed in

Table 1, the vertical distribution of LWC was derived from snow density measurements obtained by snow pit sampling, as shown in

Figure 6. The results indicate that although the absolute values differ across models due to parameterization and underlying assumptions, all consistently identify three relatively dense snow layers, characteristic of partial melting and water saturation in a very wet snowpack. The LWC profile shows an initial decrease with depth followed by a slight increase (~2.3%), deviating from the common expectation that surface snow is wetter due to direct solar radiation. Among the models, the Den model yields systematically lower LWC values, while TS and FGPA are closely aligned, and A2 lies in between. The discrepancy across models ranges from 28% to 40%. Considering that TS and FGPA incorporate both dry and wet snow conditions, their averaged result are adopted as the representative LWC in this study.

4.3. On-Site Snow Properties Measurement with UAV System

Properties of snowpack in avalanche area were measured with UAV snow sensing system.

Figure 7 presents the site area, GPR survey trajectory and temperature mapping result. Snow thickness and surface temperature were measured, and the SWE and LWC were inversed with the value calibrated in ground site A.

The UAV path for infrared thermography and optical imagery was designed for a 1:5000 mapping scale (as shown in

Figure 3). The flight altitude was maintained at a terrain-following height of 400 m above ground level, ensuring consistent ground sampling despite the average terrain elevation of 3521 m. To guarantee comprehensive spatial coverage and resolution requirement, the mission utilized high overlap rates: an along-track overlap of 80% and an across-track overlap of 70% with RTK positioning.

In contrast to the infrared and optical surveys, the UAV-GPR survey was conducted along a separate traverse due to limitations in flight altitude and battery capacity. The flight path was positioned primarily across the upper section of the gully to capture snowpack characteristics of the recently released area (upper green circle in

Figure 7), focusing on snow depth. The lower section of the survey, located within the deposit zone (lower green circle in

Figure 7), intersected a ground control point (green star in

Figure 7) where snow depth had been independently measured using a leveling rod, providing a reference for GPR velocity calibration. To accommodate the steep topography and the need for operation beyond the pilot’s visual line of sight, the UAV maintained a variable flight altitude between 2–4 m above ground level.

As shown in

Figure 7, the measured snow surface temperatures at both the gully and deposit body were generally consistent with those recorded at the ground snow pit, with values close to −0.5–0. 8 °C. This temperature condition is indicative of wet snow, where the snowpack exists at or near the melting point, resulting in a mixture of snow grains and liquid water. Notably, thermal imagery reveals a cooler region in the shaded area (blue area in

Figure 6), while the snow surface in the gully appears warmer (light blue), likely due to greater solar exposure and enhanced melting. This spatial temperature variability reflects the influence of microtopography and solar radiation on snowpack thermal dynamics, further reinforcing the need to consider both surface energy input and internal water content in avalanche hazard assessments.

As shown in

Figure 8a, distinct reflections corresponding to the air–snow interface and the snow–ground boundary are clearly identifiable in the radargram. In addition, radar signatures of two host materials are distinct. The snowpack appears as homogeneous media with smooth, continuous reflections (area below red arrow), while the subsurface of bare wet soil exhibits strong scattering and diffraction due to textural heterogeneity (area below yellow arrow).

However, additional artifacts were observed: strong ringing effects induced by the UAV landing gear, which overlapped with and distorted the primary reflections, and noticeable diffraction patterns in the homogeneous shallow ground. To address these issues, the GPR dataset was processed using standard signal conditioning procedures, including de-wow filtering, time-varying gain correction, and background removal via mean trace subtraction. These steps effectively suppressed the ringing and diffraction artifacts, yielding a clearer representation of subsurface features, as illustrated in

Figure 8b. Using the known snow depth at the control point, the radar wave velocity in the snow was calculated to be approximately 0.15 m/ns, consistent with values reported for wet snow. Based on this calibrated velocity, the two-way travel time differences between the upper and lower interfaces were converted into snow depth estimates, which ranged from 2.3 to 3.2 m along the survey path.

To further characterize snowpack properties, the SWE and LWC were estimated using the snow density values obtained from the ground site A. At the upper release area at high elevation (marked by green circle in

Figure 7), the SWE was calculated to be 1092.98 mm, with a corresponding LWC of approximately 13.8%, derived from the average of TS and FGPA wet-snow models. These values indicate pronounced moisture saturation within the snowpack. According to [

42], wet snow typically exhibits densities between 0.2 and 0.8 g/cm

3 and water contents ranging from 3–8%. The values observed in this study fall within this range, with the relatively high water content suggesting that the snowpack was in a marginally stable state, prone to shear failure and avalanche release under additional loading or warming conditions.

5. Discussion

This study characterizes the physical properties of avalanche-prone snowpacks, demonstrates the feasibility and effectiveness of using a UAV-based multi-sensor system in the high-altitude, complex terrain of southeastern Tibet. The results provide important insights into snow instability mechanisms specific to this region, which is subject to a unique combination of warm, humid monsoonal influences and steep, fluted mountain topography.

5.1. Properties of Avalanche-Prone Snowpack in Southeastern Tibet

The evaluation of several snow-dielectric inversion models, calibrated with ground measurements, indicated that the TS and FGPA models performed consistently and with similar accuracy. Both models employ separate formulations for dry and wet snow and are independent of radar frequency, making them more appropriate for GPR-based inversion in the complex snow conditions of southeastern Tibet.

Field observations revealed LWC and SWE values of up to 13.8% and 1092.98 mm, respectively, far exceeding the commonly cited critical threshold of 3–8% for wet-snow avalanche initiation. Temperature measurements obtained from both ground sampling and UAV surveys confirmed near-isothermal conditions close to 0 ‘c, particularly in release areas. The snow at fracture initiation zones, typically near ridge crests, was significantly warmer than in adjacent areas, likely due to enhanced solar radiation and localized topographic heating.

Snow depth in recently released zones exceeded 2 m, yet no discernible stratigraphic layers were observed at either ground site B or channel A. The small variation in LWC/SWE across snow pit layers indicated that the entire snowpack was uniformly wet, with differences too small to be distinguished by radar. Visual observations during snow pit excavation confirmed a high proportion of liquid water, with snow crystals showing rounded forms and poor bonding, and interspersed with ice lenses. Collectively, the observations provide an empirical indicator for early warning systems and routine monitoring of wet-snow avalanche hazards in the region.

5.2. Weak Layer at the Snow–Ground Interface

Ground site experiment shows that the SWE and LWC increases again near the snow–ground interface, which differs from the usual assumption that surface layers are wetter due to direct solar heating (

Figure 6). On-site UAV-based measurements further corroborated this observation. As illustrated in

Figure 8, reverberated reflections of higher amplitude were consistently detected below the snow–ground interface (highlighted by the yellow line), indicating the presence of liquid water within the shallow soil.

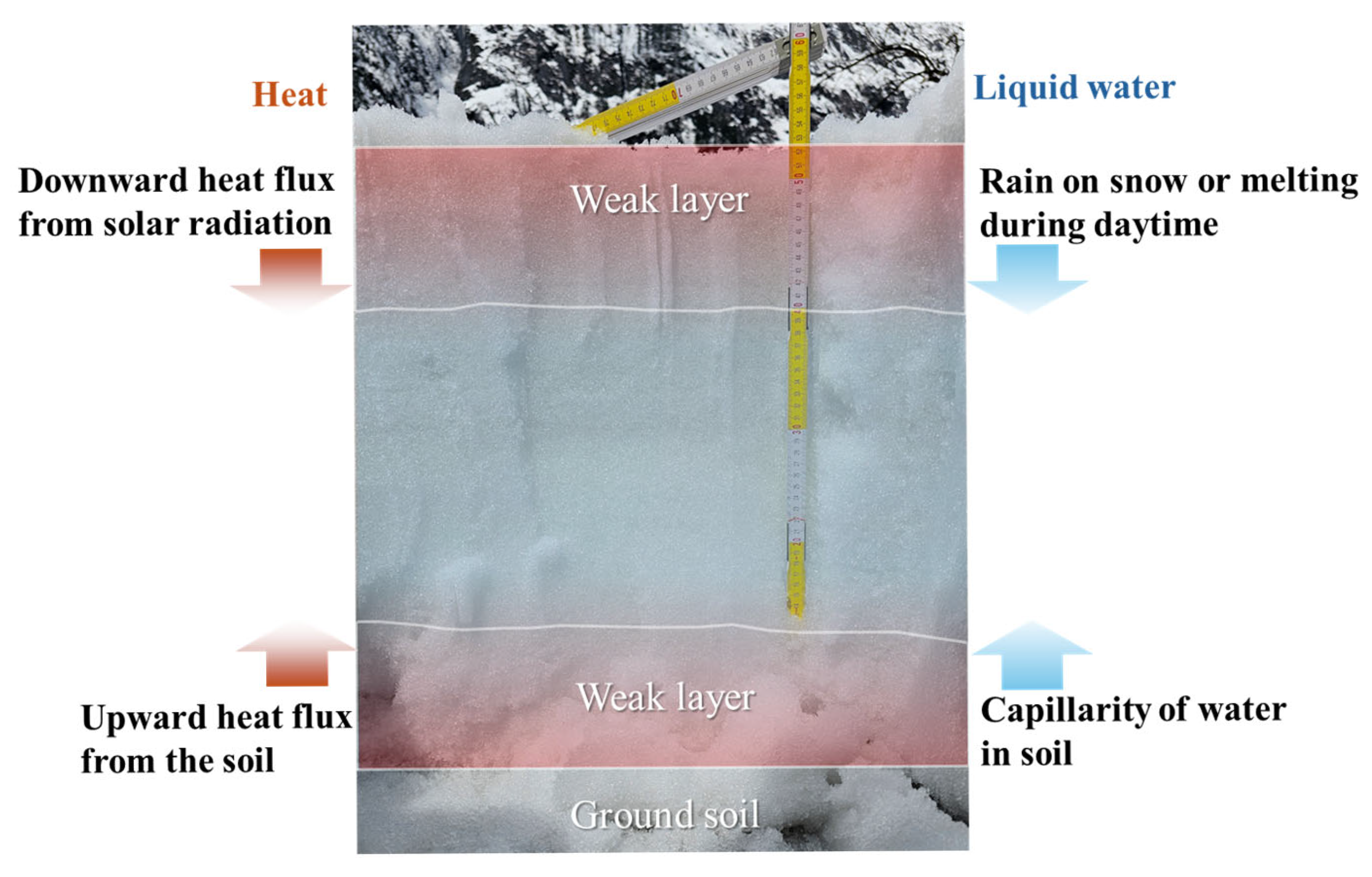

This pattern can be explained by two main processes (

Figure 9). First, meltwater formed in the upper layers infiltrates downward and accumulates in the basal snow, where reduced permeability limits further drainage. Second, the ground contributes heat and moisture: basal melting is enhanced by upward heat flux, while vapor released from the soil can condense within colder basal layers. These combined effects create a saturated basal horizon with higher LWC than the layers above, sometimes further intensified by refreezing cycles that trap liquid water behind ice lenses. Such water enrichment at the base reduces shear strength along the snow–ground contact, creating conditions favorable for wet-snow avalanche initiation at the snow–ground interface.

Accurate quantification of snow depth therefore plays a dual role: it not only constrains estimates of the release volume during an avalanche event but also provides essential input for evaluating the potential runout distance and the scale of damage to nearby infrastructure. By integrating UAV-base system, snow depth mapping can be achieved with high spatial resolution and large spatial coverage, enabling more reliable predictions of avalanche magnitude.

5.3. Efficiency and Limitation of UAV-Based Snow Sensing System

The UAV-based sensing platform enabled safe and high-resolution assessment of both surface and subsurface snowpack properties in steep and otherwise inaccessible areas. The GPR system successfully detected the snow–air and snow–ground interfaces, and SWE was estimated with the aid of ground-truth snow density and travel-time calibration. The integration of infrared thermography and optical imagery provided complementary data on snow surface temperature and slope orientation, supporting multi-modal interpretation of avalanche conditions.

However, several limitations were identified in the current system design. The 400 MHz center frequency used for GPR was sufficient for determining bulk snow depth and SWE but lacked the resolution to resolve fine-scale internal layering, which plays a crucial role in understanding snowpack metamorphism and failure mechanisms. Prior studies suggest that GPR systems operating above 1 GHz would be better suited for detecting subtle stratigraphic boundaries within wet or isothermal snow. Furthermore, due to the limited communication range of the current UAV–GPR system and flight safety constraints, near-surface data could not be obtained at the ridge-top starting zone. In future work, we plan to enhance the system’s terrain adaptability through autonomous flight control for rugged terrain and onboard data storage independent of real-time communication. Additionally, due to battery and altitude constraints in complex environment, UAV flight durations and coverage were limited. While the current system was effective for case-specific slope monitoring, sustained, long-term monitoring is necessary to capture snowpack evolution across different phases of the snow season, including accumulation, transformation, and melt-out. Establishing year-round, multi-cycle monitoring protocols would provide more robust datasets for model validation and avalanche forecasting.

6. Conclusions

This study examined the properties and failure mechanisms of wet-snow avalanche snowpacks in southeastern Tibet, where warm, humid climatic conditions and a steep, fluted terrain create instability dynamics that are distinct from those in cold, dry regions. Field calibration established the dielectric properties of avalanche-prone snow and confirmed the suitability of specific liquid water content inversion models for this environment. UAV-based surveys at a recently released avalanche channel revealed SWE and LWC values far exceeding recognized instability thresholds, near-isothermal stratigraphy, and poorly bonded wet snow layers with ice lenses. The snow depth in release zones exceeded 2 m, and no dry or cohesive layers were present, underscoring the dominance of weak, water-saturated structures in promoting failure. Collectively, these observations highlight the critical role of liquid water infiltration, soil–snow heat exchange, and thermal gradients in destabilizing snowpacks under monsoonal conditions. The results provide both methodological and regional contributions: they establish quantitative thresholds for avalanche-prone snowpack characteristics, and they illustrate how UAV-based monitoring can extend process-based understanding to inaccessible, high-relief terrain. These advances strengthen the scientific basis for early avalanche warning and hazard mitigation in southeastern Tibet and comparable mountain environments.