Highlights

What are the main findings?

- This paper introduces Off-nadir-Scene10, the first benchmark dataset for off-nadir satellite image scene classification, containing 5200 images across 10 categories and 26 viewing angles.

- This study proposes an angle-aware active domain adaptation method that leverages nadir imagery to improve off-nadir classification performance while reducing annotation requirements.

What is the implication of the main finding?

- This work demonstrates that training on larger off-nadir angles enhances cross-view transferability by promoting view-invariant feature learning.

- This study provides practical guidelines for dataset construction and training strategies to build robust off-nadir scene classification systems for real-world applications.

Abstract

Accurate remote sensing scene classification is essential for applications such as environmental monitoring and disaster management. In real-world scenarios, particularly during emergency response and disaster relief operations, acquiring nadir-view satellite images is often infeasible due to cloud cover, satellite scheduling constraints, or dynamic scene conditions. Instead, off-nadir images are frequently captured and can provide enhanced spatial understanding through angular perspectives. However, remote sensing scene classification has primarily relied on nadir-view satellite or airborne imagery, leaving off-nadir perspectives largely unexplored. This study addresses this gap by introducing Off-nadir-Scene10, the first controlled and comprehensive benchmark dataset specifically designed for off-nadir satellite image scene classification. The Off-nadir-Scene10 dataset contains 5200 images across 10 common scene categories captured at 26 different off-nadir angles. All images were collected under controlled single-day conditions, ensuring that viewing geometry was the sole variable and effectively minimizing confounding factors such as illumination, atmospheric conditions, seasonal changes, and sensor characteristics. To effectively leverage abundant nadir imagery for advancing off-nadir scene classification, we propose an angle-aware active domain adaptation method that incorporates geometric considerations into sample selection and model adaptation processes. The method strategically selects informative off-nadir samples while transferring discriminative knowledge from nadir to off-nadir domains. The experimental results show that the method achieves consistent accuracy improvements across three different training ratios: 20%, 50%, and 80%. The comprehensive angular impact analysis reveals that models trained on larger off-nadir angles generalize better to smaller angles than vice versa, indicating that exposure to stronger geometric distortions promotes the learning of view-invariant features. This asymmetric transferability primarily stems from geometric perspective effects, as temporal, atmospheric, and sensor-related variations were rigorously minimized through controlled single-day image acquisition. Category-specific analysis demonstrates that angle-sensitive classes, such as sparse residential areas, benefit significantly from off-nadir viewing observations. This study provides a controlled foundation and practical guidance for developing robust, geometry-aware off-nadir scene classification systems.

1. Introduction

Remote sensing technology has undergone tremendous advancements over the past few decades, fundamentally transforming how we observe and analyze the Earth’s surface [1,2]. Among various remote sensing tasks, scene classification—the automatic assignment of semantic labels to images on the basis of image content—plays a critical role [3,4]. Accurate scene classification enables the effective identification of land cover types and other geospatial features, which is essential for applications such as urban planning [5,6], environmental monitoring [7,8,9], disaster management [10,11,12], and geospatial intelligence [5,13].

Most existing remote sensing scene classification studies and datasets focus primarily on nadir-view satellite or airborne images captured from near-vertical overhead angles under ideal imaging conditions. Classic datasets such as UC Merced Land-Use [14], AID [15], and NWPU-RESISC45 [16] have laid a solid foundation by providing large-scale, multi-class labeled samples, significantly advancing classification model development [17,18,19]. However, nadir imagery provides only a limited viewpoint of surface objects, overlooking valuable spatial information observable from off-nadir angles, which are taken at varying angles deviating from the vertical [20,21].

In real-world scenarios, particularly during emergency response and disaster relief operations, acquiring nadir-view satellite images is often infeasible due to cloud cover, satellite scheduling constraints, or dynamic scene conditions [22,23,24]. Instead, off-nadir images that contain rich side and angular views of ground objects are frequently captured. Off-nadir images potentially increase scene understanding and classification accuracy since structural details and three-dimensional (3D) characteristics that are not observable from nadir views are revealed [20,25].

Despite their advantages, off-nadir images pose significant challenges for scene classification. The off-nadir viewing angles introduce geometric distortions, increased occlusions, varying illumination and shadow effects, and changes in object appearance [20,25,26]. Therefore, off-nadir and nadir imagery should not be considered in the same domain. Models trained solely on nadir-view data often perform poorly when directly applied to off-nadir images [27,28], highlighting the need for dedicated datasets and tailored algorithms.

1.1. Existing Datasets and Their Limitations

Several notable public datasets have accelerated remote sensing scene classification research in recent years. Datasets such as UC Merced Land-Use (UCM) [14], AID [15], NWPU-RESISC45 [16], and OPTIMAL-31 [29] offer diverse scene categories with high-quality nadir imagery. In these datasets, the annotated images share a uniform resolution; for example, UCM, NWPU-RESISC45, and OPTIMAL-31 use 256 × 256 pixels, and AID uses 600 × 600 pixels. These datasets have been important in advancing models that are both accurate and robust across various urban and natural landscapes [17,18,19,30,31,32]. However, these datasets predominantly contain nadir-view images.

Some newer datasets, such as SpaceNet MVOI [33], S2Looking [34], BANDON [25], AiRound and CV-BrCT [35], have introduced off-nadir imagery in image classification [31,36,37,38], object detection [39,40,41,42], and change detection tasks [43,44,45,46,47]. Their focus has been largely restricted to man-made structures such as buildings, with limited scene categories and a relatively narrow range of viewing angles. Furthermore, these datasets often feature fewer annotated off-nadir angles, thereby limiting research on generalizable off-nadir scene classification.

To date, there remains an evident absence of an off-nadir scene classification dataset that comprehensively covers multiple common remote sensing scene categories, providing multi-view images across a broad range of off-nadir angles. The lack of such a dataset presents a significant barrier to advancing off-nadir scene classification algorithms and understanding the angular effect on classification performance [20,25]. Additionally, collecting and annotating off-nadir images at scale is inherently challenging due to the diversity of viewpoints and the complexity of image interpretation [33,34], which results in considerable time and cost burdens for manual labeling.

1.2. Off-Nadir Imagery: Potential and Challenges

Compared with nadir imagery, off-nadir imagery provides richer spatial, angular, and spectral information by capturing objects from different perspectives. This multi-view observation enables a more detailed representation of side structures, shadows, and three-dimensional characteristics of landscapes [48,49]. Such diverse information has proven beneficial in pixel- and object-level tasks, most notably in image classification [50,51,52,53], object detection [27,39,54], and change detection [25,44,45]. However, despite these advances, research on scene-level classification using off-nadir imagery remains limited. The impact of off-nadir angle variation on classification performance is still understudied.

In image classification, angle-induced variations in shading, texture, and 3D geometry provide additional cues that improve recognition. Multi-angle features such as GLCM MA-T [52] and angular-difference features (ADF) [51] have been shown to enhance the discrimination of spectrally similar objects such as roads and buildings. Network designs, including CAPNet [53] and S2Net [50], further leverage stereo disparity and geometric cues to capture urban structures more effectively. These studies demonstrate the strong potential of off-nadir imagery in classification tasks, suggesting that similar multi-view advantages may extend to scene-level classification.

Off-nadir imagery also enriches object detection by revealing oblique perspectives and structural details otherwise hidden in nadir views. Methods such as the NaGAN normalize angular distortions to improve building detection [39], whereas offset vector learning schemes enable more accurate footprint extraction from tilted views [27]. Global built-up area mapping approaches also highlight the usefulness of multi-angular indices in capturing vertical features [54]. However, challenges such as geometric distortions, occlusions, and varying shadow effects remain [33]. These factors underscore that angle variation can significantly influence detection outcomes and may similarly impact scene-level classification.

For change detection, off-nadir perspectives provide complementary observations that capture structural changes more reliably. The S2Looking dataset has facilitated progress, with methods such as CGNet [44] and BAN [45] improving temporal analysis and leveraging knowledge from foundation models. These studies confirm that multi-angle information enhances change detection for man-made objects. However, most work remains limited to building-focused applications, leaving broader scene categories insufficiently explored.

Overall, off-nadir imagery has proven effective across classification, detection, and change detection, largely due to its enriched geometric and angular information [25]. However, these advances primarily address object-centric or urban-focused categories. The evolution of classification accuracy across different off-nadir angles for diverse land-use and land-cover scenes remains unclear. This poses an important open challenge for developing robust scene-level classification models and guiding data collection strategies.

1.3. Domain Adaptation and Its Limitations

Domain adaptation seeks to extend a model trained on a source domain to a target domain by reducing distribution discrepancies [55]. The main challenge is the misalignment of feature and label spaces between domains [56]. In remote sensing, numerous deep learning-based methods have been developed to address domain shifts. Contrastive self-supervised learning approaches combined with consistency self-training have proven effective in extracting transferable features and identifying unknown classes [57]. Joint optimization strategies that minimize both global and local distribution differences while enhancing class separability have shown significant improvements in cross-domain performance [58]. Subspace alignment techniques incorporating additional alignment layers in CNNs help mitigate distribution gaps between domains [59]. Universal domain adaptation frameworks have been developed to handle scenarios with unknown label sets and can even operate without source data access [60]. Partial domain adaptation strategies that utilize auxiliary domain modules and entropy regularization effectively reduce negative transfer effects [28]. Active domain adaptation methods have also emerged, integrating active learning principles by selectively labeling informative target-domain samples to increase model adaptability across domains [61].

These approaches have demonstrated strong performance across diverse remote sensing applications, including cross-sensor adaptation from high-resolution optical imagery to SAR data, cross-region transfer for urban and agricultural mapping despite climate and spectral variations, and multi-temporal adaptation to address seasonal and phenological changes [55]. These successes highlight the effectiveness of distribution alignment in bridging domain gaps caused by sensor characteristics, geographic variability, and temporal dynamics. However, these methods share common limitations. Most assume that annotations in the target domain are scarce or entirely unavailable, and they generally treat the source and target as unrelated distributions. This assumption overlooks potential structural and semantic correlations that exist between domains. In the context of nadir-to-off-nadir adaptation, such limitations become especially pronounced. Nadir and off-nadir images share the same underlying ground semantics, but the latter suffers from viewpoint-induced distortions, occlusions, and appearance changes [20,39]. This angular effect introduces systematic feature shifts that cannot be fully addressed by conventional distribution alignment, which focuses primarily on reducing overall global discrepancies.

Thus, while domain adaptation methods have advanced remote sensing classification, their effectiveness in nadir-to-off-nadir transfer remains insufficient. Developing approaches that account for the angle-specific nature of off-nadir imagery remains a crucial challenge for enabling robust scene classification across viewing geometries.

1.4. Motivation for This Work

To bridge the gaps identified above, we propose the following key initiatives:

- (1)

- Creation of Off-nadir-Scene10 benchmark dataset: We introduce Off-nadir-Scene10, the first multi-category dataset explicitly designed for off-nadir satellite image scene classification. It contains 5200 images covering 10 common remote sensing scene types captured at 26 different off-nadir angles, providing extensive angular diversity and scene complexity. This dataset addresses the critical shortage of annotated off-nadir imagery needed for advancing off-nadir scene classification research. The Off-nadir-Scene10 dataset is available at https://github.com/AIP2025-RS/Off-nadir-Scene10 (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- (2)

- Angle-aware active domain adaptation for scene classification: Leveraging the abundance of labeled nadir remote sensing images, we develop an improved active domain adaptation method that incorporates off-nadir angle awareness into sample selection and model adaptation. By integrating angle-dependent weighting into the sample selection criterion, our approach effectively transfers discriminative knowledge from nadir to off-nadir domains. This reduces the demand for labeled off-nadir samples, thereby enhancing classification accuracy.

- (3)

- Comprehensive angular impact analysis: We systematically analyze how off-nadir viewing angles affect classification performance by dividing the dataset into groups on the basis of off-nadir angle magnitude and examining intra- and cross-group training/testing accuracies. Our results reveal pronounced angular influences on generalization and provide insights into the asymmetric transferability between large- and small-angle views, which can guide future data collection and model design.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the Off-nadir-Scene10 dataset construction and characteristics. Section 3 details the design of the angle-aware active domain adaptation methodology. Section 4 presents extensive experimental results and an analysis of angular impact. Section 5 provides a discussion, and Section 6 offers conclusions.

2. Off-Nadir Image Scene Classification Benchmark Dataset

2.1. Process of Dataset Building

The creation of the Off-nadir satellite image benchmark dataset for remote sensing scene classification was divided into four steps, namely, scene category selection, data source acquisition, sample point annotation, and image cropping.

2.1.1. Scene Category Selection

By referencing existing remote sensing scene classification datasets, we identified ten common and representative scene categories: baseball diamond, commercial area, dense residential, forest, freeway, industrial area, lake, overpass, parking lot, and sparse residential. These scene categories consist of different types of ground objects. They exhibit various visual variations in different off-nadir remote sensing images.

2.1.2. Data Source Acquisition

To avoid differences in land features among various regions in the subsequent effect analysis of off-nadir angles, the selected images with different off-nadir angles should ideally cover the same area and be acquired on the same day. We selected 26 different off-nadir satellite images covering the Atlanta area in the eastern United States as the data source for creating the dataset. These images were acquired with Maxar’s WorldView-2 satellite on 22 December 2009.

2.1.3. Sample Point Annotation

The scene types of the off-nadir remote sensing images are determined with the reference data. For each scene category, 20 different sample points were selected with the raw full image at the lowest off-nadir angle. These sample points were annotated with reference to OpenStreetMap (OSM) vector data and Google Earth imagery. The latitude and longitude coordinates of these sample points were recorded in the point vector file.

2.1.4. Image Cropping

The raw full off-nadir images in the source data first undergo preprocessing, such as projection transformation. When cropping labeled images from these raw full images, the sample point was used as the center point of the labeled image. The size of the cropped image was determined by the off-nadir angle of the raw full image, which was set to a predetermined dimension. For the same sample point, 26 cropped images with the label of the sample point were obtained from 26 raw full off-nadir images in turn. In this way, the off-nadir satellite image benchmark dataset for remote sensing scene classification, Off-nadir-Scene10, was created.

2.2. Dataset Description

The Off-nadir-Scene10 dataset contains a total of 5200 off-nadir remote sensing images, encompassing ten categories: baseball diamond, commercial area, dense residential, forest, freeway, industrial area, lake, overpass, parking lot, and sparse residential. Each category includes 20 scene areas, with each scene area covered by 26 different off-nadir images. The specific parameters of these off-nadir images are provided in Table 1. The off-nadir angles of these images range from 8.1° to 53.8°, corresponding to different spatial resolutions and pixel sizes of scene images. The scene image with the minimum off-nadir angle of 8.1° has the highest spatial resolution of 0.474 m and a pixel size of 902 × 902, whereas the scene image with the maximum off-nadir angle of 53.8° has the lowest spatial resolution of 1.67 m and a pixel size of 256 × 256.

Table 1.

Parameters of Off-nadir Images in Off-nadir-Scene10 Dataset.

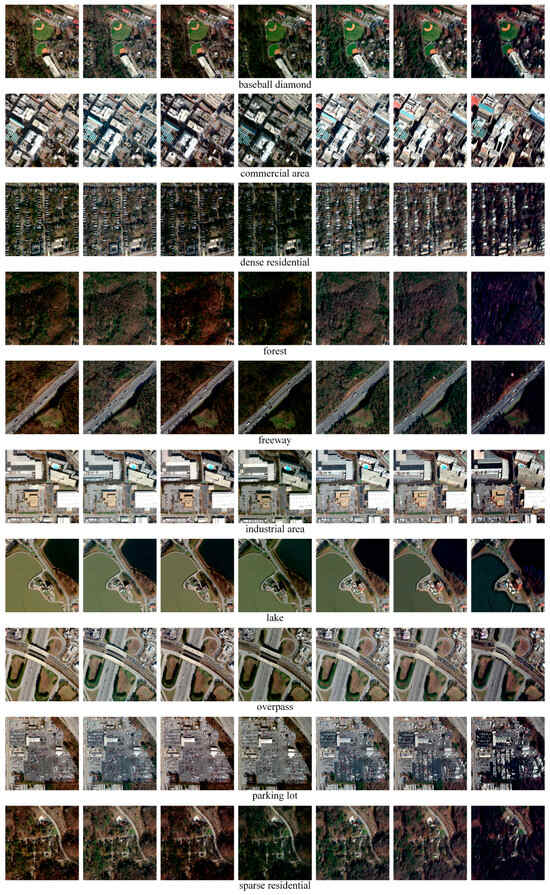

For each category, seven typical observation angles of the same scene area are presented as example images of the dataset in Figure 1. Different categories of scenes exhibit visual differences under various viewing angles, which can be categorized based on the prominence of geometric distortions, shadow variations, and the visibility of object sides. Specifically, these visual differences manifest through the extent of shadow area changes as off-nadir angle increases, the degree to which lateral surfaces of elevated structures become visible, and the level of occlusion and perspective distortion affecting ground objects. Scene categories with tall buildings, such as commercial areas and industrial areas, show greater visual differences across large and small off-nadir images. In these categories, large off-nadir angles produce substantially more pronounced shadow areas, expose multiple building facades that are invisible in nadir views, and introduce significant perspective foreshortening. These angular-dependent changes provide rich geometric cues but also increase classification difficulty due to appearance variability. In contrast, scene categories with simple combinations of ground objects having minimal height differences from surrounding objects or terrain, such as freeways, usually exhibit minimal visual differences across various off-nadir images.

Figure 1.

Examples of off-nadir images in the Off-nadir-Scene10 dataset. The image examples for each category are all from the same region. The off-nadir angle IDs of these example images from left to right are OA7, OA15, OA22, OA32, OA33, OA44, and OA54, respectively.

3. Methodology

3.1. Angle-Aware Active Domain Adaptation

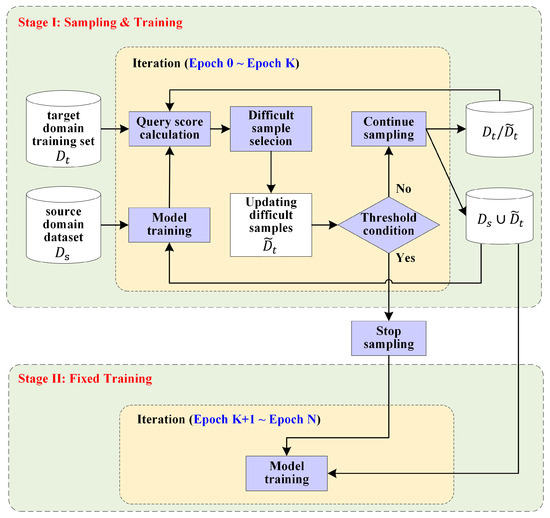

Angle-aware active domain adaptation (AADA) is performed for off-nadir satellite image scene classification with limited labeled data. As shown in Figure 2, model training consists of two stages: the first stage involves sample selection and training, whereas the second stage continues training after the training samples are fixed at the end of the first stage. The first stage of model training spans from epoch 0 to epoch K, whereas the second stage of model training spans from epoch K + 1 to the final epoch, where the sampling reaches the threshold condition at epoch K.

Figure 2.

Illustration of model training for angle-aware active domain adaptation (AADA).

The specific model training process of AADA is described below. The labeled off-nadir images are used as the target domain training set , whereas the auxiliary labeled nadir images are used as the source domain data . During model training, the model is optimized through backpropagation to minimize margin loss, using the union of the source domain data and difficult sample data in the domain data . In the first stage of model training, difficult sample data in the domain data are continually updated until the threshold condition is reached. In the first epoch of model training, the difficult sample data are an empty set , which is equivalent to using only the source domain data ; the difficult sample data are updated from the target domain training set with a query score function, which takes off-nadir angles of images in court. In other epochs of the first stage, the difficult sample data of the previous epoch are combined with the source domain data for model training. In this way, difficult samples from the target domain are added to improve model robustness. In the first stage of the model training process, the difficult sample dataset , the target domain training set , and the complete training set are continuously updated through sampling until the sample number in reaches the given sampling threshold . Once the quantity of difficult samples meets the sampling threshold, the complete training set is finalized, ending the adaptive sampling phase. In the second stage of model training, the model is further refined on the compiled training dataset until the end of the training process, enabling stable learning performance over epochs K + 1 to N. This two-stage training approach ensures that the model is both flexible in adapting to domain challenges during sampling and robust after sample selection is completed.

3.2. Margin Loss Function in Model Training

A margin loss function is designed to ensure that the model can adapt more effectively to the target domain. Only samples whose classification scores for the ground-truth class are close to those for other classes can contribute meaningfully to the deep network’s gradient. As a result, the model during training is not overly influenced by redundant source domain samples but instead focuses more on those with ambiguous boundaries and close scores, allowing the model to adapt better to the target domain.

Mathematically, the margin loss function is initially calculated as follows:

where represents the samples in the source domain dataset, is the feature extractor, is the linear classifier that classifies the features into a class vector of size , denotes zero-clip operation , the subscripts and indicate the and entries of vectors, and is a hyper-parameter to control the expected margin width. The loss function, defined in Equation (1), explicitly expands the gap in the feature space of different scene category data.

The margin loss function is further refined to be dynamically adjusted to effectively prevent simple samples from dominating the model’s training. The network training adaptively focuses more on hard-to-classify samples with smaller margins while ensuring high classification confidence for the ground-truth class. The dynamically adjusted margin loss function is defined as follows:

where is the max-logit term, which ensures that the model consistently assigns higher scores to the true class . denotes the zero-clip operation . With the improved margin loss function defined in Equation (2), the network adaptively focuses on hard-to-classify samples while maintaining high confidence for the ground-truth class. This approach enables the model to update parameters in the direction of maximizing the feature distance among different scene categories.

3.3. Sampling Query Function

A sampling query function is proposed to evaluate the importance of unlabeled target samples for network training. During training, the network naturally focuses more on samples in the target domain that have similar class scores in the probability vector since the margin loss function used expands the distance between classification clusters of different scene categories. Moreover, the off-nadir angle of the target sample needs to be included in the sampling query function to achieve good domain adaptation. Given that the source domain involves only nadir images, more attention should be given to large off-nadir angles to improve the learning efficiency of the network in the target domain. With the sampling query function, the sampled data first have large off-nadir angles and are close to the decision boundary of the trained network.

Mathematically, the sampling query function is initially defined as follows:

where represents the sample in the target domain training set, and where is the off-nadir angle of the sample . Meanwhile, and represent the indices of the maximum and second maximum values in the probability vector , which is obtained through mapping the logit vector via the Softmax operation. The probability vector is calculated as shown in Equation (4):

The query score of an image in the target domain, calculated according to Equation (3), ranges from 0 to 1. Those images with large query score values are prioritized for inclusion in the hard sample dataset .

The sampling query function is further refined by introducing a correction term to ensure that the gradient of the loss term and the margin sampling show similar directions in the feature space. As formulated in Equation (5), the query function is refined as follows:

where is a balance factor, and where is the cosine similarity metric for measuring the similarity between directions of probability gradient estimations and . The probability gradient estimation is consistent with the marginal sampling and is calculated as shown in Equation (6):

where and represent the labels corresponding to the largest and second largest values in the probability vector , respectively.

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Experimental Setting

4.1.1. Overall Experimental Setup

To comprehensively evaluate the created Off-nadir-Scene10 dataset, we designed three types of experiments. For the first type, 22 representative scene classification networks were conducted on the created dataset. For the second type, three training modes were compared to clarify the effectiveness of the AADA method. For the third type, experiments grouped by off-nadir angles were conducted to investigate the effectiveness of additional information provided by off-nadir images for scene classification. The AADA method was used in the latter two types of experiments. This study used NWPU-10, a subset of the NWPU-RESISC45 dataset [16], as source domain data, containing 10 scene categories matching the Off-nadir-Scene10 dataset with 700 images per category. These images are 256 × 256 pixels in size with spatial resolutions ranging from 0.2 to 30 m.

In all experiments, the batch size was set to 16, and the number of epochs was set to 200. The learning rate was set to 0.0001, and the Adam optimizer was selected for model optimization. All experiments consistently employed commonly used data augmentation techniques to enhance model generalization. The training images were first resized to 256 × 256 pixels and then randomly cropped to 224 × 224 pixels. Horizontal flipping was applied with a probability of 0.5 to increase orientation diversity, and mild color jittering with ±10% adjustment in brightness, contrast, saturation, and hue was used to simulate illumination variability. All augmentation settings were kept identical across experiments to ensure fair comparisons among methods. All experiments were implemented using PyTorch 2.5.1 and conducted on a personal computer equipped with an Intel Core i5-1135G7 CPU (manufactured by Intel Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and a Tesla P100-PCIE GPU (manufactured by NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with 16 GB of memory.

4.1.2. Experiments of Representative Networks

The 22 representative networks selected to test the usability of the Off-nadir-Scene10 dataset were VGG16 [62], Inception-v3 [63], ResNet-50 [64], SqueezeNet-10 [65], DenseNet-121 [66], ShuffleNetV2 [67], MobileNetV2 [68], ResNeXt-50 [69], Swin-T [70], ConvNeXt V2 Tiny [71], ResNeSt-50 [72], PVT v2-B2 [73], PoolFormer-S24 [74], DaViT-Tiny [75], EdgeNeXt-S [76], TinyViT-21M [77], Sequencer2D-S [78], InceptionNeXt-T [79], FastViT-SA24 [80], RepGhostNet [81], RepViT-M1.1 [82], and EfficientViT-B1 [83]. These networks, pre-trained on ImageNet, were fine-tuned with the Off-nadir-Scene10 dataset. Moreover, three different training ratios were used in this study: 20%, 50%, and 80%. Table 2 shows the number of locations and images in the training and testing sets under three different training ratios.

Table 2.

Number of locations and images in the training and testing sets under different training ratios.

4.1.3. Comparison Experiment of Training Modes

Three training modes were compared on the Off-nadir-Scene10 dataset. (i) Finetuned-ImageNet. This mode fine-tuned the ResNet50 model pre-trained on ImageNet with the Off-nadir-Scene10 dataset. (ii) Finetuned-NWPU10. This mode fine-tuned the ResNet50 model pre-trained on ImageNet and NWPU10 in sequence, with the Off-nadir-Scene10 dataset. (iii) AADA. This mode used the weights of the ResNet50 model pre-trained on ImageNet as the initial weights of the network, and trained with the NWPU-10 dataset as the source domain data and the Off-nadir-Scene10 dataset as the target domain data. The specific sampling setting during the training process was to fix the number of scene images sampled from the target domain at 1040, regardless of the amount of training data. The AADA method was trained not only with the input images re-sized to 256 × 256 pixels but also re-sized to 600 × 600 pixels, denoted as AADA-600. Furthermore, these training modes were compared against the advanced domain adaptation method, SDM [61], on the Off-nadir-Scene10 dataset.

4.1.4. Grouping Experiment by Off-Nadir Angles

The Off-nadir-Scene10 dataset was divided into two groups based on the off-nadir angles: Group A with small off-nadir angles, and Group B with large off-nadir angles. The off-nadir IDs and specific angle information for these two groups are detailed in Table 3. According to the sources of the training and testing data groups, four experiments with different off-nadir angle modes were defined: A_A (training and testing images from Group A), A_B (training from Group A, testing from Group B), B_B (training and testing from Group B), and B_A (training from Group B, testing from Group A). Moreover, to obtain more comprehensive results, the target domain training data for these four modes of experiments were set at ratios of 20%, 50%, and 80%. Each experiment under these three training ratios was sampled 26 times, with 20 sampling rounds to ensure a consistent number of training images, i.e., 520 images.

Table 3.

Detailed statistical information of the two groups with different off-nadir angles.

4.2. Classification Results of Representative Networks

Table 4 shows the scene classification accuracy results of 22 selected representative networks on the Off-nadir-Scene10 dataset under three different training ratios, namely 20%, 50%, and 80%. For the same network, the scene classification accuracy increases as the training ratio increases. The overall classification accuracy under the training ratio of 20% is generally 4.81% to 24.35% lower than that of the 80% training ratio. Most networks achieved good classification performance with a training ratio of 80%.

Table 4.

Overall classification accuracy results of 22 commonly used networks on the Off-nadir-Scene10 dataset under three different training ratios.

4.3. Performance of Training Modes vs. SDM

The overall classification accuracy results of the methods under different training modes on the Off-nadir-Scene10 dataset are shown in Table 5. For the same method, the order from lowest to highest accuracy is under training ratios of 20%, 50% and 80%. Under the same training ratio, the accuracy of methods under different training modes, from lowest to highest, is as follows: Finetune-ImageNet, Finetune-NWPU10, SDM, AADA, and AADA-600. AADA and AADA-600 achieved higher accuracy than SDM, with AADA-600 performing slightly better than AADA. Compared with Finetune-NWPU10, the AADA method shows significant performance improvements at lower training ratios, achieving approximately 0.04 overall accuracy gains at both 20% and 50% training ratios, while showing diminished effectiveness with less than 0.01 accuracy improvement at the 80% training ratio.

Table 5.

Overall classification accuracy results of methods under different training modes and SDM on the Off-nadir-Scene10 dataset.

The computation time results of the methods under different training modes on the Off-nadir-Scene10 dataset are shown in Table 6. For the same method, the order from lowest to highest computation time is under training ratios of 20%, 50% and 80%. Under the same training ratio, the computation times of methods under different training modes from lowest to highest are as follows: Finetune-ImageNet, Finetune-NWPU10, SDM, AADA, and AADA-600. Under the three training ratios, AADA-600 requires significantly more computation time than AADA but achieves only slightly higher accuracy. This limited improvement suggests a saturation effect, as classification performance at large off-nadir angles is likely dominated by geometric distortions rather than local spatial detail. Therefore, the AADA method trained with the input images re-sized to 256 × 256 pixels was used in the other experiments.

Table 6.

Computational time of methods under different training modes and SDM on the Off-nadir-Scene10 dataset. Unit: hour.

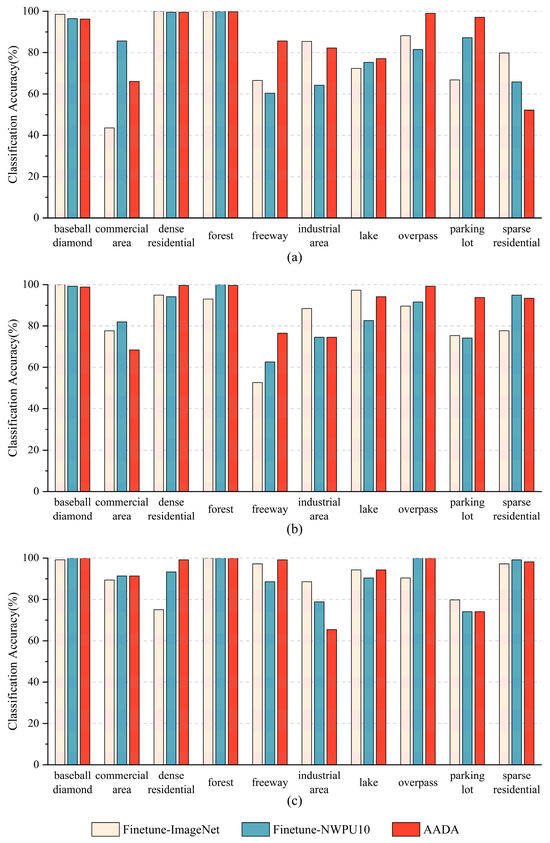

4.4. Results of Methods for Different Training Modes

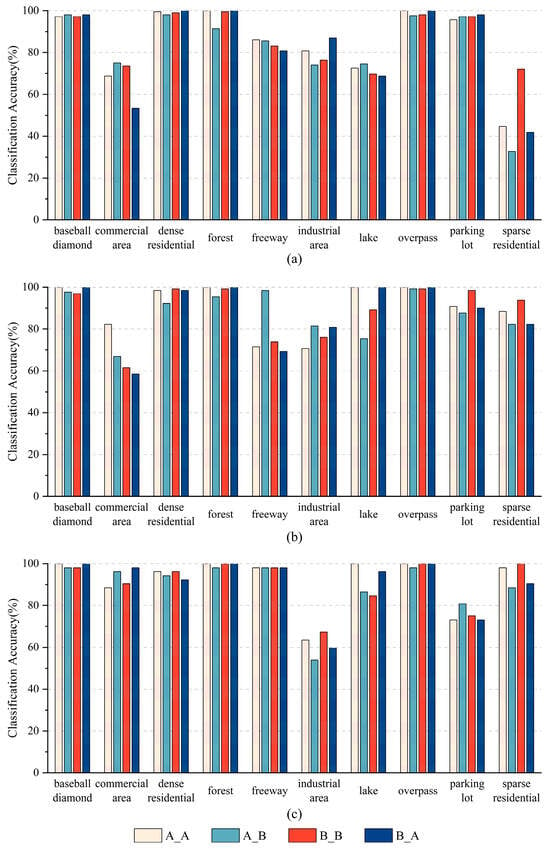

Figure 3 shows scene classification accuracy for each category with three methods under different training modes on the Off-nadir-Scene10 dataset. Different scene categories usually obtain various accuracy results when using the same method under the same training ratio. The AADA method obtains various accuracy gains for different scene categories in comparison to the Finetune-ImageNet method. The AADA method obtains high accuracy gains for many categories, especially for freeway, overpass, and parking lot, under the lower training ratio, such as 20% and 50%. Some scene categories, such as baseball diamond, achieve exceptionally high accuracy with the Finetune-ImageNet method even under the 20% training ratio, making it challenging for the AADA method to surpass these results.

Figure 3.

Scene classification accuracy for each category with three methods under different training modes on the Off-nadir-Scene10 dataset under three different training ratio settings: (a) 20%, (b) 50%, and (c) 80%.

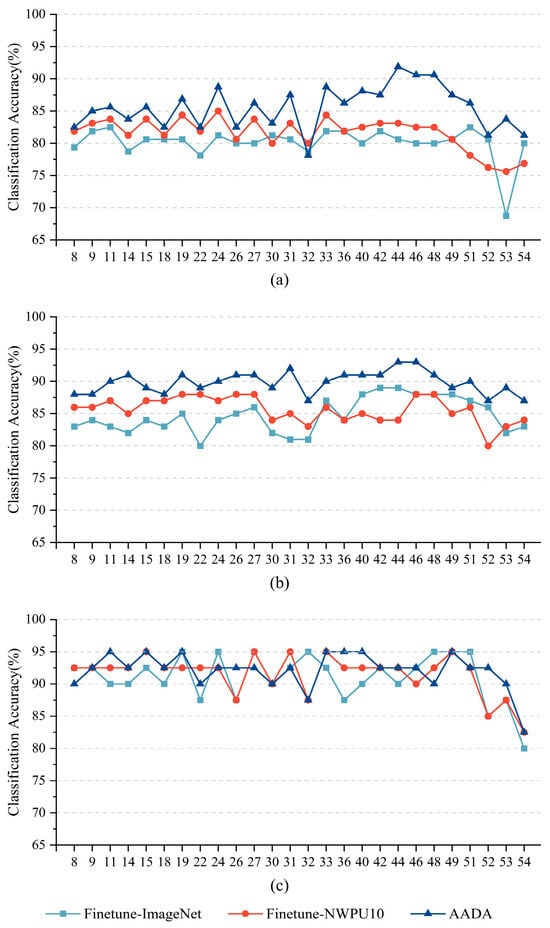

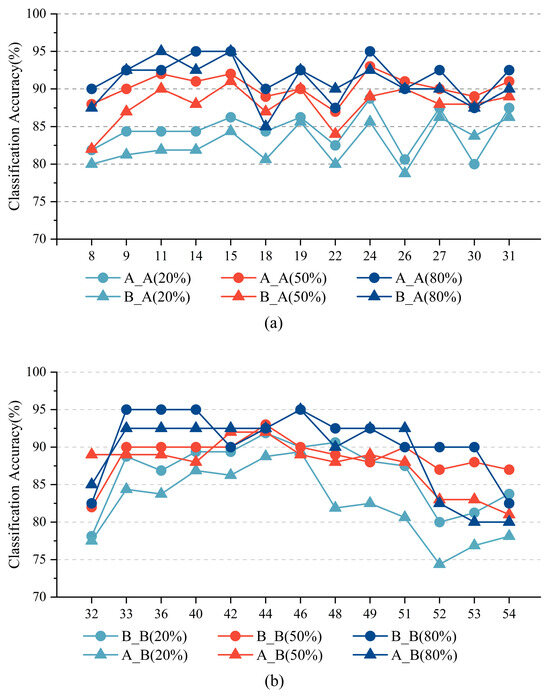

Figure 4 shows the classification accuracy results for different off-nadir angles when three methods are used under different training modes on the Off-nadir-Scene10 dataset. The classification accuracy varies with the off-nadir angle when the same method is used under the same training ratio. For the same off-nadir angle, the classification accuracy usually increases as the training ratio increases. Under the 20% training ratio, the AADA method obtained higher accuracy than the Finetune-ImageNet method for almost all off-nadir angles, especially for off-nadir angles larger than 33°. Under the 50% training ratio, the AADA method obtained consistent accuracy gains in comparison to the Finetune-ImageNet method. Under the 80% training ratio, the three methods obtained comparable accuracy results for most off-nadir angles.

Figure 4.

Classification accuracy results of different off-nadir angles with three methods under different training modes on the Off-nadir-Scene10 dataset under three different training ratio settings: (a) 20%, (b) 50%, and (c) 80%.

4.5. Results of Grouping Experiments by Off-Nadir Angles

Table 7 shows the overall classification accuracy results of four experiments with different off-nadir angle modes, which use the small off-nadir angle Group A or the large off-nadir angle Group B as the training or test data. Under the same training ratio, two experiments in which training and testing were from the same group, A_A and B_B, achieved higher accuracy than the other two experiments in which training and testing were from different groups, A_B and B_A. The accuracy of experiment B_A is higher than that of experiment A_B under the same training ratio. In other words, models trained on larger off-nadir angles transfer better to smaller angles than vice versa. Moreover, for an experiment, the overall classification accuracy increases as the training ratio increases.

Table 7.

Overall classification accuracy results of four experiments with different off-nadir angle modes.

Figure 5 shows the scene classification accuracy for each category with four experiments with different off-nadir angle modes on the Off-nadir-Scene10 dataset. In these four experiments, some scene categories, e.g., baseball diamond and overpass, obtain comparable accuracy results, whereas other scene categories, e.g., sparse residential, usually obtain various accuracy results. Under the same training ratio, two experiments in which training and testing are from the same group, A_A and B_B, usually achieve comparable or higher accuracy than the other two experiments in which training and testing are from different groups, A_B and B_A. Moreover, the B_A group usually outperforms the A_B group across categories, especially under the 50% training ratio in categories such as sparse residential, in which category scenes of discriminative objects have abundant side-view information or possess three-dimensional features.

Figure 5.

Scene classification accuracy for each category with four experiments with different off-nadir angle modes on the Off-nadir-Scene10 dataset under three different training ratio settings: (a) 20%, (b) 50%, and (c) 80%.

Figure 6 shows the scene classification accuracy of different off-nadir angles with four experiments with different off-nadir angle modes on the Off-nadir-Scene10 dataset under three different training ratios. The test images of the two experiments A_A and B_A were from Group A, whereas the test images of the two experiments A_B and B_B were from Group B. Thus, only the two experiments A_A and B_A are included in Figure 6a, whereas only the two experiments A_B and B_B are included in Figure 6b.

Figure 6.

Scene classification accuracy of different off-nadir angles with four experiments with different off-nadir angle modes on the Off-nadir-Scene10 dataset under three different training ratios: (a) accuracy of small off-nadir angles in Group A, (b) accuracy of large off-nadir angles in Group B.

The classification accuracy for a given off-nadir angle is influenced by both the training ratio and the discrepancy between the off-nadir angle ranges of the training and testing datasets. Specifically, for a fixed off-nadir angle, the classification accuracy tends to improve with increasing training ratio. Under identical training ratios, experiments where training and testing data originate from the same group generally exhibit higher accuracy than those where training and testing data come from different groups. When a substantial difference exists between the tested off-nadir angle and the training angle range, the accuracy for that off-nadir angle tends to decline, particularly at lower training ratios. For example, as illustrated in Figure 6a, the classification accuracy from OA8 to OA18 for B_A is lower than that of A_A. Similarly, in Figure 6b, the classification accuracy from OA48 to OA54 for A_B is lower than for B_B. Furthermore, a comparative analysis of Figure 6a,b reveals that the accuracy curves in Figure 6a display greater stability with smaller fluctuations across different off-nadir angles. This suggests that knowledge transfer from larger to smaller off-nadir angles is more robust and consistent than the reverse direction.

5. Discussion

5.1. Contributions of the Off-Nadir-Scene10 Dataset

The Off-nadir-Scene10 dataset addresses a significant gap in existing benchmarks by focusing on off-nadir viewing conditions rather than conventional vertical perspectives. It systematically covers 26 off-nadir angles across 10 common scene categories, capturing geometric distortion, occlusion, shadow effects, and appearance changes that standard nadir datasets cannot represent. This comprehensive coverage transforms viewpoint variation from an uncontrolled factor into an explicit research dimension, enabling systematic off-nadir angle-based analyses and more accurate evaluation of cross-view performance.

The dataset employs a controlled experimental design that prioritizes scientific rigor over raw diversity. All images were acquired by WorldView-2 on the same day, which represents a deliberate methodological choice rather than a limitation. By controlling temporal, atmospheric, and sensor variables, the dataset isolates the viewing angle as the primary independent variable, enabling unambiguous attribution of classification performance changes to geometric perspective effects. This controlled approach prevents confounding factors such as seasonal variations, illumination differences, atmospheric conditions, or sensor-specific characteristics from obscuring the fundamental relationship between the off-nadir angle and scene classification accuracy. Such experimental control is essential for establishing a baseline understanding of angular effects before introducing additional complexity.

The Off-nadir-Scene10 dataset addresses limitations in existing resources by providing essential off-nadir angle data for model training and testing under realistic imaging conditions. Unlike multi-source datasets that introduce sensor heterogeneity, the Off-nadir-Scene10 enables researchers to isolate and quantify the specific impact of viewing geometry on classification performance. This focused approach has revealed fundamental insights that would be difficult to extract from datasets with multiple confounding variables, including the asymmetric nature of angular knowledge transfer and category-specific sensitivity patterns.

By making Off-nadir-Scene10 publicly available, this work reduces access barriers and encourages the research community to build upon a shared foundation. The dataset creators provide a clear framework for future benchmarks, defining approaches for angle coverage, class diversity, and sample size. Despite its moderate size, the dataset’s controlled design and angular completeness establish it as an important foundation for future benchmark construction. Its structured organization also facilitates subsequent expansion to multi-satellite or multi-temporal datasets without compromising its consistent angular sampling framework, allowing broader generalization studies to build upon a unified standard. For algorithm developers, it supports fair comparisons and systematic investigation of high-performance training approaches, including nadir-to-off-nadir transfer learning, angle-aware sampling strategies, and active selection that prioritizes informative large-angle samples.

We recognize that complementary datasets incorporating multiple satellites, geographic regions, and temporal coverage would provide additional dimensions for robustness evaluation. The controlled foundation established by Off-nadir-Scene10 enables such extensions to build upon a clear baseline understanding of angular effects. Future work will expand geographic and temporal coverage while preserving systematic angular sampling, which makes rigorous cross-view analysis possible.

5.2. Role of Nadir Data and Angle-Aware Active Domain Adaptation

The results with the proposed AADA method demonstrate that nadir imagery serves as an effective source domain when adaptation explicitly considers viewing geometry rather than depending solely on global alignment. By incorporating angle-dependent weighting into the active selection process, the method focuses limited labeling resources on samples that are both informative and angle-diverse, producing consistent accuracy improvements across training ratios while controlling annotation costs. The underlying principle is clear: nadir and off-nadir views represent the same scene semantics but differ systematically due to perspective effects, shadows, and occlusions. Consequently, an effective transfer approach should be geometry aware rather than geometry independent.

Two practical implications emerge from these findings. First, abundant nadir labels can significantly facilitate learning in the off-nadir domain when the adaptation process focuses on samples that reveal view-dependent differences rather than distributing effort uniformly. Second, angle-guided active selection provides an efficient labeling approach to expose the model early to challenging perspectives, improving robustness without requiring extensive off-nadir annotation. As seen in Table 5, comparative experiments demonstrate that AADA outperforms the advanced domain adaptation method, the SDM, across different training ratios. When training images are resized to 256 × 256 pixels, AADA achieves comparable computational time to SDM while maintaining higher accuracy. As seen in Table 5 and Table 6, increasing the image size from 256 × 256 pixels to 600 × 600 pixels substantially raises computation cost but yields minimal accuracy gains. This saturation effect occurs because classification performance at large off-nadir angles is likely dominated by geometric distortions rather than local spatial detail. Consequently, the 256 × 256-pixel configuration provides a more efficient balance between computational cost and discriminative performance.

The performance of AADA depends on several hyperparameters that balance adaptation effectiveness and computational cost. The active sampling ratio determines the proportion of unlabeled samples selected per iteration, directly affecting the annotation efficiency and model exposure to diverse angular perspectives. The learning rate and adaptation regularization weight control the strength of domain alignment relative to task-specific learning, influencing convergence stability and generalization to unseen angles. While our experiments employed commonly used data augmentation techniques consistently across all the compared methods, the synergistic effects of augmentation strategies with angle-aware selection deserve further study. Similarly, systematic analysis of hyperparameter sensitivity across different angular distributions would provide more robust guidelines for practical deployment. These aspects represent important directions for future methodological refinement.

5.3. Angular Impact Analysis on Scene Classification

The results of grouping experiments by off-nadir angles reveal two stable patterns that guide model design and data selection. As seen in Table 7, the accuracy is highest when training and testing share comparable off-nadir ranges, confirming that distributional alignment remains central to view-robust classification. Furthermore, when there is a substantial discrepancy between the training and testing off-nadir angle ranges, the classification accuracy significantly decreases, especially at lower training ratios. Notably, models trained on larger off-nadir angles transfer better to smaller angles than vice versa, demonstrating an asymmetric behavior in knowledge transfer. As shown in Figure 6, this asymmetry is evidenced by more stable accuracy curves and smaller variations when transferring from large to small angles, as opposed to the greater variability observed in the reverse direction. This phenomenon occurs because exposure to severe distortions and occlusions at large off-nadir angles promotes the learning of robust, geometry-independent features. In contrast, models trained only on small angles lack sufficient adaptability to extreme off-nadir viewing conditions.

Our experiments demonstrate this asymmetric transferability with an angle span of approximately 26 degrees between large and small off-nadir angle groups, which are defined according to Table 4. While this span reveals the fundamental directional preference in angular knowledge transfer, the quantitative relationship between the angle span magnitude and accuracy degradation remains to be systematically characterized. Future work should conduct angle span gradient experiments with finer granularity (e.g., 5-, 10-, 15-, 20-, and 25-degree spans) to establish precise degradation curves. Such quantitative characterization would enable data collection strategies to balance coverage costs against performance requirements by identifying critical angle span thresholds beyond which accuracy loss becomes unacceptable for specific applications. This would provide actionable guidance for satellite tasking decisions where acquisition constraints necessitate trade-offs between angular diversity and sample quantity.

The controlled acquisition design of Off-nadir-Scene10 was essential for revealing these asymmetric transferability patterns. By eliminating temporal and sensor variables, the dataset enables direct measurement of how the geometric perspective alone influences feature learning and cross-view generalization. These findings would be difficult to establish definitively in datasets where angular effects are confounded with seasonal changes, atmospheric variations, or sensor differences.

Category-specific analysis provides practical guidance for implementation. As seen in Figure 5, scene classes with significant angular variation or frequent occlusion, such as sparse residential areas, show substantial benefits from side-view information available at larger off-nadir angles. This finding indicates that off-nadir data diversity is most beneficial for categories where side structures or height information significantly improve visual discrimination. These findings support two practical implementation strategies. First, broader off-nadir angle coverage for angle-sensitive classes is provided through angle-aware sampling and category-specific augmentation. Second, ensuring that training includes sufficient off-nadir views to develop reliable cross-view features.

While this study focuses on the impact of viewing angles on surface scene classification, it is necessary to clarify the distinction between general off-nadir imaging and limb observations. Off-nadir satellite imaging refers to angled viewing geometries used for surface analysis, improving coverage and revisit frequency while preserving recognizable ground features. Limb observation, by contrast, represents an extreme off-nadir configuration in which the sensor views tangentially along the Earth’s horizon to measure atmospheric properties. This mode, primarily used for atmospheric sounding, differs fundamentally from surface-oriented imaging in both purpose and data characteristics. The Off-nadir-Scene10 dataset, therefore, focuses on off-nadir angles up to about 53 degrees, where geometric distortion becomes pronounced but the surface structure remains clearly discernible for reliable scene classification.

6. Conclusions

This work addresses a critical gap in remote sensing scene classification by introducing the first comprehensive off-nadir benchmark dataset and developing a novel adaptation method for cross-view generalization. The Off-nadir-Scene10 dataset, comprising 5200 images across 10 scene categories and 26 off-nadir angles, provides the research community with essential resources for the systematic study of viewpoint effects in satellite image classification. Although the dataset scale is moderate due to the challenge of collecting multiple off-nadir angles per region, it represents a meaningful benchmark at the current stage of geometry-aware classification research. Unlike heterogeneous multi-source datasets, its controlled single-day acquisition design isolates the effect of viewing geometry while minimizing confounding factors such as illumination or atmospheric differences. This controlled foundation enables clear attribution of classification performance changes to the geometric perspective alone. Our angle-aware active domain adaptation method demonstrates that strategic leveraging of abundant nadir data can significantly improve off-nadir classification performance while alleviating annotation requirements. Our method achieves consistent accuracy gains across different training ratios through geometry-aware sample selection.

The comprehensive angular impact analysis reveals fundamental insights into cross-view transferability: training on larger off-nadir angles generalizes better to smaller angles than vice versa. This finding indicates that exposure to stronger geometric distortions promotes the learning of view-invariant features. Moreover, controlled experiments confirm that this asymmetric transferability arises specifically from geometric perspective effects rather than temporal or sensor variability. Category-specific analysis further shows that angle-sensitive classes, such as sparse residential areas, benefit disproportionately from multi-view observations, highlighting the importance of side structure information in discriminating among confusable classes. These findings establish clear guidelines for data collection strategies and training strategy design. The Off-nadir-Scene10 dataset thus provides a practical and extensible foundation for future studies, particularly those incorporating multi-satellite and multi-temporal data, to evaluate broader generalization while preserving its rigorous angular sampling structure.

The contributions of this work extend beyond methodological advances to provide actionable insights for the remote sensing community. The open-access Off-nadir-Scene10 dataset serves as both a benchmark for fair algorithm comparison and a reference for the future construction of an off-nadir scene classification dataset. The demonstrated effectiveness of angle-aware adaptation opens new avenues for exploiting geometric relationships in domain transfer. The asymmetric transferability patterns inform optimal training strategies for view-robust scene classification systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.P.; methodology, H.H. and M.G.; software, H.H. and M.G.; validation, F.P. and L.J.; formal analysis, F.P. and L.J.; investigation, F.P. and L.J.; data curation, H.H. and T.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, F.P. and M.G.; writing—review and editing, F.P. and L.J.; visualization, M.G.; supervision, F.P.; project administration, F.P.; funding acquisition, F.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grants 42071389 and 42471446, the Project Supported by the Key Laboratory for Geographical Process Analysis and Simulation of Hubei Province under Grant ZDSYS202402, and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities under Grants CCNU25JCPT001.

Data Availability Statement

The Off-nadir-Scene10 dataset is available at https://github.com/AIP2025-RS/Off-nadir-Scene10 (accessed on 9 November 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lu, S.; Guo, J.; Zimmer-Dauphinee, J.R.; Nieusma, J.M.; Wang, X.; VanValkenburgh, P.; Wernke, S.A.; Huo, Y. Vision Foundation Models in Remote Sensing: A Survey. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2025, 13, 190–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Han, W.; Huang, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Li, J. Trustworthy Remote Sensing Interpretation: Concepts, Technologies, and Applications. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2024, 209, 150–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Sun, C.; Gao, J.; Wang, Q. Few-Shot Remote Sensing Scene Classification via Parameter-Free Attention and Region Matching. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2025, 227, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C.; Zhang, X.; Tong, X.; Guan, N.; Yi, X.; Yang, K.; Zhu, J.; Yu, A. Few-Shot Remote Sensing Image Scene Classification: Recent Advances, New Baselines, and Future Trends. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2024, 209, 368–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, A.; Horanont, T.; Neupane, B.; Aryal, J. Deep Learning for Remote Sensing Image Scene Classification: A Review and Meta-Analysis. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Chen, B.; Wu, S.; Su, M.; Chen, J.M.; Xu, B. Deep Learning for Urban Land Use Category Classification: A Review and Experimental Assessment. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 311, 114290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, R.N.; Fraternali, P. Learning to Identify Illegal Landfills through Scene Classification in Aerial Images. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jozdani, S.; Chen, D.; Chen, W.; Leblanc, S.G.; Lovitt, J.; He, L.; Fraser, R.H.; Johnson, B.A. Evaluating Image Normalization via GANs for Environmental Mapping: A Case Study of Lichen Mapping Using High-Resolution Satellite Imagery. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 5035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Wu, Y.; Ma, X. Deep Learning-Based Algal Bloom Identification Method from Remote Sensing Images—Take China’s Chaohu Lake as an Example. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.; Zhao, W.; Ji, F.; Peng, R.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Q. Recognizing Unknown Disaster Scenes with Knowledge Graph-Based Zero-Shot Learning (KG-ZSL) Model. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5621315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Xiao, Z.; Hu, J.; Han, J.; Kim, J.Y.; Sharma, R.; Li, C. FSBNet: A Classifying Framework of Disaster Scene for Volcanic Lithology through Deep-Learning Models. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 15101–15115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Zhang, F.; Xia, J.; Xie, J.; Zhang, Z.; Du, Z.; Liu, R. Identifying Damaged Buildings in Aerial Images Using the Object Detection Method. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Tang, W.; Chen, S.-E.; Allan, C. SA-Encoder: A Learnt Spatial Autocorrelation Representation to Inform 3D Geospatial Object Detection. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Newsam, S. Bag-of-Visual-Words and Spatial Extensions for Land-Use Classification. In Proceedings of the 18th SIGSPATIAL International Conference on Advances in Geographic Information Systems, San Jose, CA, USA, 2–5 November 2010; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 270–279. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, G.-S.; Hu, J.; Hu, F.; Shi, B.; Bai, X.; Zhong, Y.; Zhang, L.; Lu, X. AID: A Benchmark Data Set for Performance Evaluation of Aerial Scene Classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2016, 55, 3965–3981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Han, J.; Lu, X. Remote Sensing Image Scene Classification: Benchmark and State of the Art. Proc. IEEE 2017, 105, 1865–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Jiang, K.; He, J.; Lin, C.-W.; Zhang, L. TTST: A Top-k Token Selective Transformer for Remote Sensing Image Super-Resolution. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2024, 33, 738–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Yuan, J.; Wen, C.; Lu, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, X. RSGPT: A Remote Sensing Vision Language Model and Benchmark. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2025, 224, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Chen, S.; Ermon, S.; Lobell, D.B. Transfer Learning in Environmental Remote Sensing. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 301, 113924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNally, S.; Nielsen, A.; Barrieau, A.; Jabari, S. Improving Off-Nadir Deep Learning-Based Change and Damage Detection through Radiometric Enhancement. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2024, 48, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poli, D.; Moe, K.; Legat, K.; Toschi, I.; Lago, F.; Remondino, F. Use of Vertical Aerial Images for Semi-Oblique Mapping. ISPRS—Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2017, 42, 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Kao, C.-H.; Phoo, C.P.; Mall, U.; Hariharan, B.; Bala, K. AllClear: A Comprehensive Dataset and Benchmark for Cloud Removal in Satellite Imagery. In Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 10–15 December 2024; Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Satriano, V.; Ciancia, E.; Pergola, N.; Tramutoli, V. A First Extension of the Robust Satellite Technique RST-FLOOD to Sentinel-2 Data for the Mapping of Flooded Areas: The Case of the Emilia Romagna (Italy) 2023 Event. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, A.; Ramanathan, V.; Pentland, A.; Mahajan, D. Adaptive Methods for Real-World Domain Generalization. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 14335–14344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, C.; Wu, J.; Ding, J.; Song, C.; Xia, G.-S. Detecting Building Changes with Off-Nadir Aerial Images. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2023, 66, 140306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; He, T.; McVicar, T.R.; Liang, S.; Liu, T.; Peng, W.; Song, D.-X.; Tian, F. Quantifying How Topography Impacts Vegetation Indices at Various Spatial and Temporal Scales. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 312, 114311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Meng, L.; Li, W.; Yang, W.; Yu, L.; Xia, G.-S. Learning to Extract Building Footprints from Off-Nadir Aerial Images. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 1294–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, W.; Chen, M.; Li, W.; Fu, H. Partial Domain Adaptation for Scene Classification from Remote Sensing Imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5626911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, S.; Chanussot, J.; Li, X. Scene Classification with Recurrent Attention of VHR Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2019, 57, 1155–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Chen, B.; Liu, C.; Li, W.; Zou, Z.; Shi, Z. RSMamba: Remote Sensing Image Classification with State Space Model. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 8002605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, C.J.; Gupta, R.; Li, S.; Brockman, S.; Funk, C.; Clipp, B.; Keutzer, K.; Candido, S.; Uyttendaele, M.; Darrell, T. Scale-MAE: A Scale-Aware Masked Autoencoder for Multiscale Geospatial Representation Learning. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 4–6 October 2023; pp. 4065–4076. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Li, W.; Zhang, M.; Tao, R.; Chanussot, J. Remote-Sensing Scene Classification via Multistage Self-Guided Separation Network. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5615312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, N.; Lindenbaum, D.; Bastidas, A.; Etten, A.V.; McPherson, S.; Shermeyer, J.; Vijay, V.; Tang, H. SpaceNet MVOI: A Multi-View Overhead Imagery Dataset. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 992–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Lu, Y.; Chen, H.; Wei, H.; Xie, D.; Yue, J.; Chen, R.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, A.; Lv, S.; et al. S2Looking: A Satellite Side-Looking Dataset for Building Change Detection. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 5094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, G.; Ferreira, E.; Nogueira, K.; Oliveira, H.; Brito, M.; Gama, P.H.T.; dos Santos, J.A. AiRound and CV-BrCT: Novel Multiview Datasets for Scene Classification. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 488–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hänsch, R.; Arndt, J.; Lunga, D.; Gibb, M.; Pedelose, T.; Boedihardjo, A.; Petrie, D.; Bacastow, T.M. Spacenet 8-the Detection of Flooded Roads and Buildings. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 1472–1480. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Wan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Y.; Guo, H.; Pei, Y.; Hu, Z. PSDA: Pyramid Spatial Deformable Aggregation for Building Segmentation in Multiview Remote Sensing Images. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 8995–9008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhang, R.; Xu, F.; Liang, S.; Wang, Y.; Yang, W. BuildMon: Building Extraction and Change Monitoring in Time Series Remote Sensing Images. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 10813–10826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, L.; Huo, C.; Zhang, X.; Wang, P.; Zhang, L.; Guo, K.; Zhou, Z. NaGAN: Nadir-like Generative Adversarial Network for Off-Nadir Object Detection of Multi-View Remote Sensing Imagery. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, T.; Weng, X.; Holail, S.; Hao, C.; Xia, G.-S. DAM-Net: Flood Detection from SAR Imagery Using Differential Attention Metric-Based Vision Transformers. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2024, 212, 440–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, F.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, P.; Fang, Y. An Active Object-Detection Algorithm for Adaptive Attribute Adjustment of Remote-Sensing Images. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, R.; Jia, Z.; Yin, X.; Niu, Y.; Qi, Y. Domain Feature Decomposition for Efficient Object Detection in Aerial Images. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toker, A.; Kondmann, L.; Weber, M.; Eisenberger, M.; Camero, A.; Hu, J.; Hoderlein, A.P.; Şenaras, Ç.; Davis, T.; Cremers, D. Dynamicearthnet: Daily Multi-Spectral Satellite Dataset for Semantic Change Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 21158–21167. [Google Scholar]

- Han, C.; Wu, C.; Guo, H.; Hu, M.; Li, J.; Chen, H. Change Guiding Network: Incorporating Change Prior to Guide Change Detection in Remote Sensing Imagery. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2023, 16, 8395–8407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Cao, X.; Meng, D. A New Learning Paradigm for Foundation Model-Based Remote-Sensing Change Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5610112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Zhu, K.; Peng, D.; Tang, H.; Yang, K.; Bruzzone, L. Adapting Segment Anything Model for Change Detection in VHR Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5611711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Ermon, S.; Kim, D.; Zhang, L.; Zhong, Y. Changen2: Multi-Temporal Remote Sensing Generative Change Foundation Model. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2025, 47, 725–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marí, R.; Facciolo, G.; Ehret, T. Sat-NeRF: Learning Multi-View Satellite Photogrammetry with Transient Objects and Shadow Modeling Using RPC Cameras. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–20 June 2022; pp. 1310–1320. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, S.; Zhang, L.; Jeon, G.; Yang, X. Remote Sensing Neural Radiance Fields for Multi-View Satellite Photogrammetry. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, P.; Zhang, X.; Chen, G.; Wang, T.; Li, X.; Yang, H.; Zhou, W.; He, C.; Wang, Q. S2Net: A Multitask Learning Network for Semantic Stereo of Satellite Image Pairs. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5601313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Chen, H.; Gong, J. Angular Difference Feature Extraction for Urban Scene Classification Using ZY-3 Multi-Angle High-Resolution Satellite Imagery. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2018, 135, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Li, S.; Li, J.; Jia, X.; Li, J.; Zhu, X.X.; Benediktsson, J.A. A Multispectral and Multiangle 3-D Convolutional Neural Network for the Classification of ZY-3 Satellite Images over Urban Areas. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 59, 10266–10285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, R.; Huang, X.; Li, J.; Pan, X. A Cross-Angle Propagation Network for Built-Up Area Extraction by Fusing Spatial–Spectral-Angular Features From the ZY-3 Multiview Satellite Imagery: Dataset and Analysis of China’s 41 Major Cities. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5408320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Huang, X.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, H.; Tang, X.; Gong, J. Automatic Extraction of Built-up Area from ZY3 Multi-View Satellite Imagery: Analysis of 45 Global Cities. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 226, 51–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Deng, W. Deep Visual Domain Adaptation: A Survey. Neurocomputing 2018, 312, 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, S.; Wang, S.; Zhuo, J.; Li, L.; Huang, Q.; Tian, Q. Towards Discriminability and Diversity: Batch Nuclear-Norm Maximization under Label Insufficient Situations. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 3940–3949. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Hou, D.; Xing, H. A Self-Supervised-Driven Open-Set Unsupervised Domain Adaptation Method for Optical Remote Sensing Image Scene Classification and Retrieval. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5605515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Pan, B.; Chen, Z.; Xu, X.; Shi, Z. An Open Set Domain Adaptation Algorithm via Exploring Transferability and Discriminability for Remote Sensing Image Scene Classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5609512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Yu, H.; Miao, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Lin, Y.; Wang, S. Domain Adaptation for Convolutional Neural Networks-Based Remote Sensing Scene Classification. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2019, 16, 1324–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Shi, Y.; Yuan, X.; Zhu, X.X. Universal Domain Adaptation for Remote Sensing Image Scene Classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 4700515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Luo, Z.; Gan, Z.; Sun, Z.; Chi, M.; Wang, C.; Wang, P. Learning Distinctive Margin toward Active Domain Adaptation. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 7983–7992. [Google Scholar]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.1556. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Vanhoucke, V.; Ioffe, S.; Shlens, J.; Wojna, Z. Rethinking the Inception Architecture for Computer Vision. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 2818–2826. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Iandola, F.N.; Moskewicz, M.W.; Ashraf, K.; Han, S.; Dally, W.J.; Keutzer, K. SqueezeNet: AlexNet-Level Accuracy with 50x Fewer Parameters and <1MB Model Size. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1602.07360. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; Van Der Maaten, L.; Weinberger, K.Q. Densely Connected Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 2261–2269. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, N.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, H.-T.; Sun, J. ShuffleNet V2: Practical Guidelines for Efficient CNN Architecture Design. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2018, Munich, Germany, 14–18 September 2018; Ferrari, V., Hebert, M., Sminchisescu, C., Weiss, Y., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 122–138. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L.-C. MobileNetV2: Inverted Residuals and Linear Bottlenecks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 4510–4520. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, S.; Girshick, R.; Dollár, P.; Tu, Z.; He, K. Aggregated Residual Transformations for Deep Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 5987–5995. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin Transformer: Hierarchical Vision Transformer Using Shifted Windows. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 9992–10002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.; Debnath, S.; Hu, R.; Chen, X.; Liu, Z.; Kweon, I.S.; Xie, S. ConvNeXt V2: Co-Designing and Scaling ConvNets with Masked Autoencoders. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 16133–16142. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Wu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Lin, H.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, Y.; He, T.; Mueller, J.; Manmatha, R.; et al. ResNeSt: Split-Attention Networks. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–20 June 2022; pp. 2735–2745. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Xie, E.; Li, X.; Fan, D.-P.; Song, K.; Liang, D.; Lu, T.; Luo, P.; Shao, L. PVT v2: Improved Baselines with Pyramid Vision Transformer. Comput. Vis. Media 2022, 8, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Luo, M.; Zhou, P.; Si, C.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, X.; Feng, J.; Yan, S. MetaFormer Is Actually What You Need for Vision. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 10809–10819. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, M.; Xiao, B.; Codella, N.; Luo, P.; Wang, J.; Yuan, L. DaViT: Dual Attention Vision Transformers. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2022, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; Avidan, S., Brostow, G., Cissé, M., Farinella, G.M., Hassner, T., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 74–92. [Google Scholar]

- Maaz, M.; Shaker, A.; Cholakkal, H.; Khan, S.; Zamir, S.W.; Anwer, R.M.; Shahbaz Khan, F. EdgeNeXt: Efficiently Amalgamated CNN-Transformer Architecture for Mobile Vision Applications. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2022 Workshops, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; Karlinsky, L., Michaeli, T., Nishino, K., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, K.; Zhang, J.; Peng, H.; Liu, M.; Xiao, B.; Fu, J.; Yuan, L. TinyViT: Fast Pretraining Distillation for Small Vision Transformers. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2022, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; Avidan, S., Brostow, G., Cissé, M., Farinella, G.M., Hassner, T., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 68–85. [Google Scholar]

- Tatsunami, Y.; Taki, M. Sequencer: Deep LSTM for Image Classification. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2205.01972. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, W.; Zhou, P.; Yan, S.; Wang, X. InceptionNeXt: When Inception Meets ConvNeXt. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 5672–5683. [Google Scholar]

- Vasu, P.K.A.; Gabriel, J.; Zhu, J.; Tuzel, O.; Ranjan, A. FastViT: A Fast Hybrid Vision Transformer Using Structural Reparameterization. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023; pp. 5762–5772. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Guo, Z.; Zeng, H.; Xiong, P.; Dong, J. RepGhost: A Hardware-Efficient Ghost Module via Re-Parameterization. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.06088. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Chen, H.; Lin, Z.; Han, J.; Ding, G. Rep ViT: Revisiting Mobile CNN From ViT Perspective. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 15909–15920. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, H.; Li, J.; Hu, M.; Gan, C.; Han, S. EfficientViT: Lightweight Multi-Scale Attention for High-Resolution Dense Prediction. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023; pp. 17256–17267. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |