Evaluating Consistency and Accuracy of Public Tidal Flat Datasets in China’s Coastal Zone

Highlights

- Systematic evaluation of six tidal flat datasets across China reveals pronounced spatial discrepancies and regional variations in accuracy;

- Independent edge-based validation demonstrates that dataset reliability strongly depends on sensor type and index selection.

- It provides a benchmark for dataset selection and methodological optimization, supporting improved coastal wetland monitoring and management.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study Area and Dataset

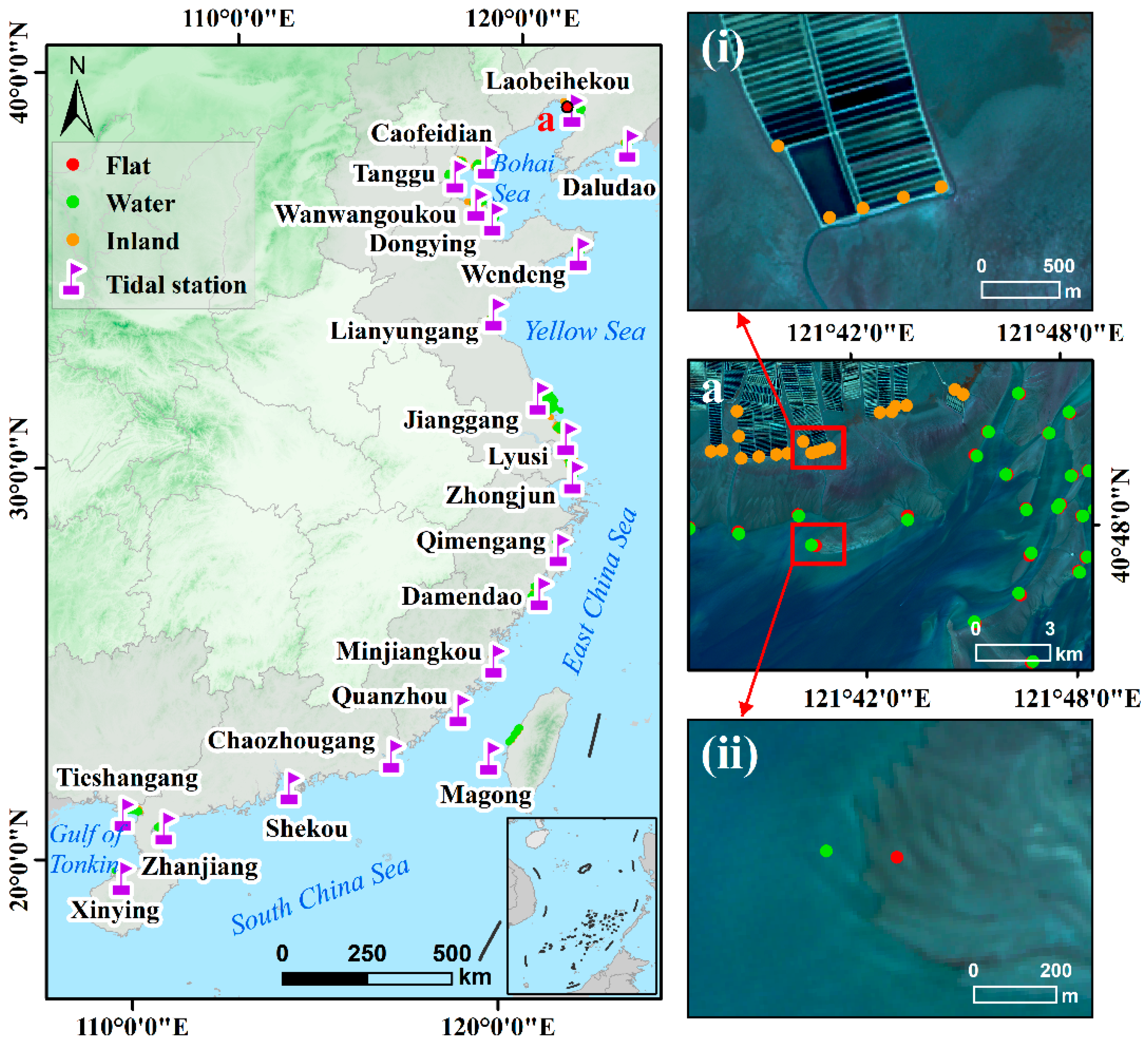

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Publicly Available Tidal Flat Datasets

3. Methods

3.1. Dataset Standardization

3.2. Quantitative Comparison

3.2.1. Area Discrepancy

3.2.2. Spatial Consistency

3.3. Edge Validation

3.3.1. Sample Collection

3.3.2. Accuracy Assessment

4. Results

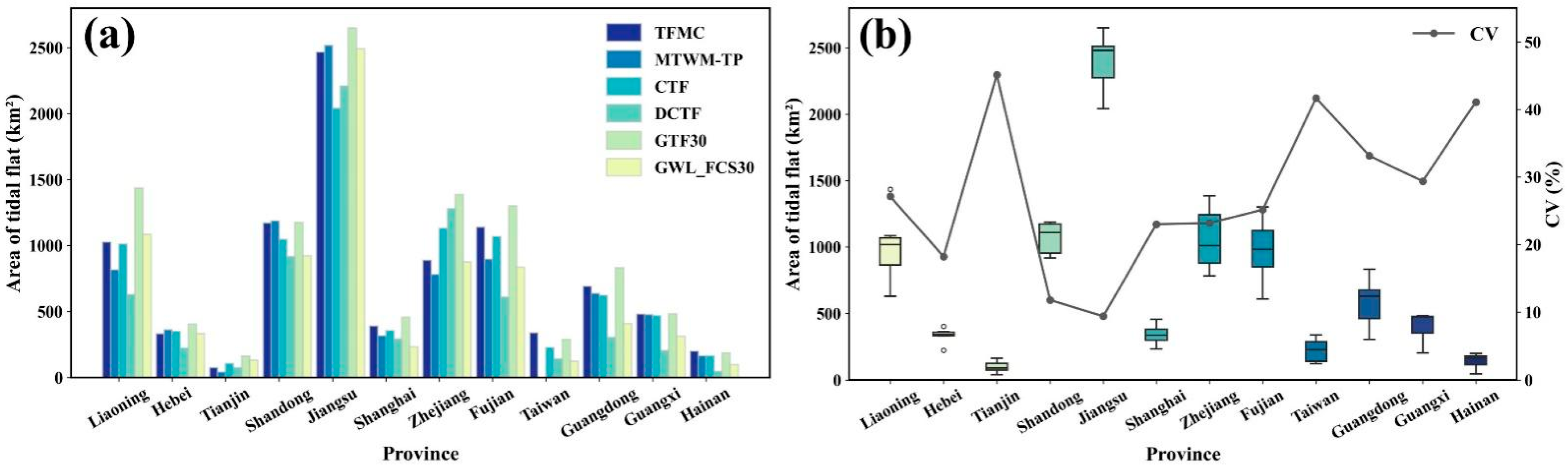

4.1. Inter Dataset Variability in Tidal Flat Area

4.2. Provincial Scale Area Rankings

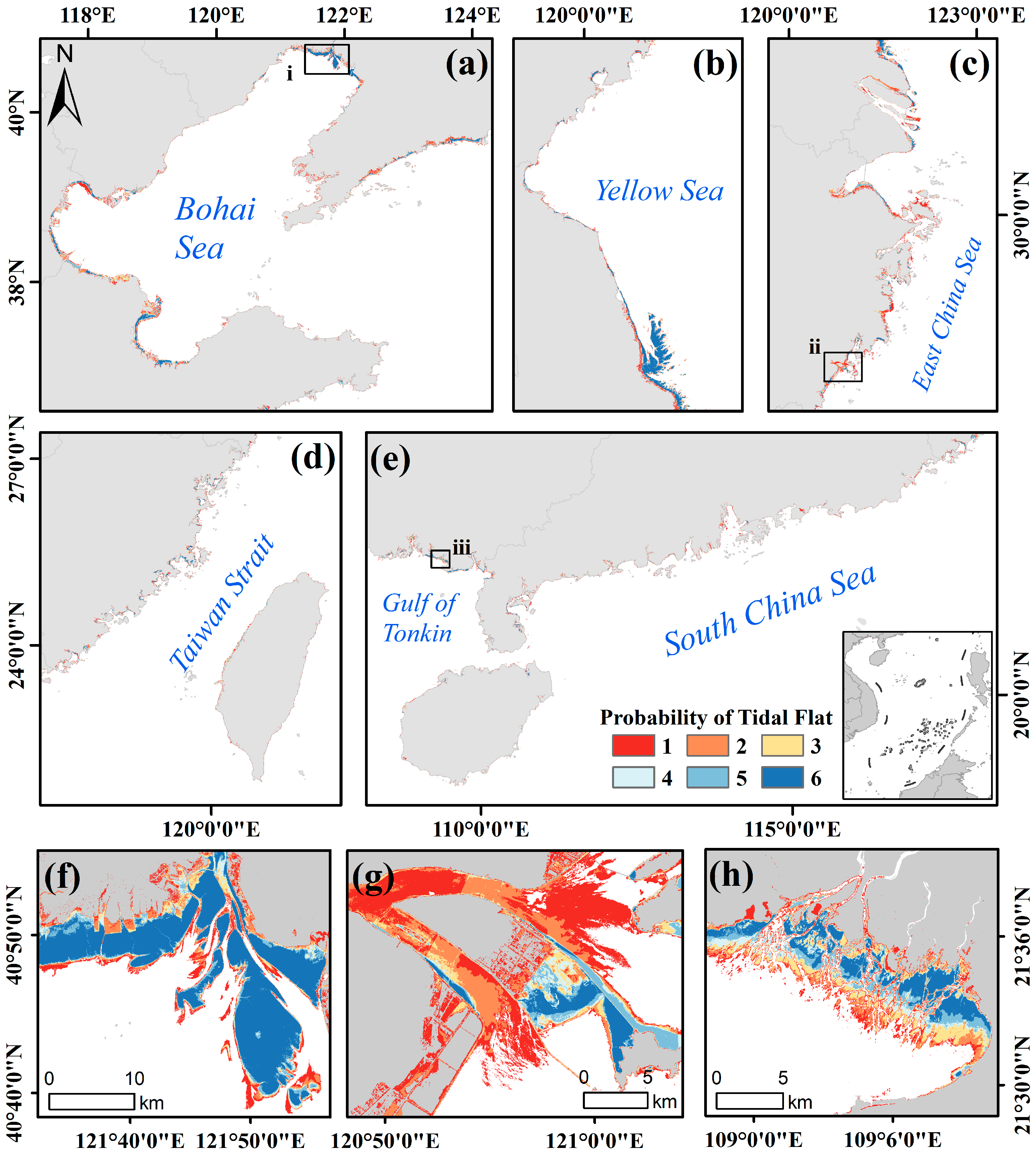

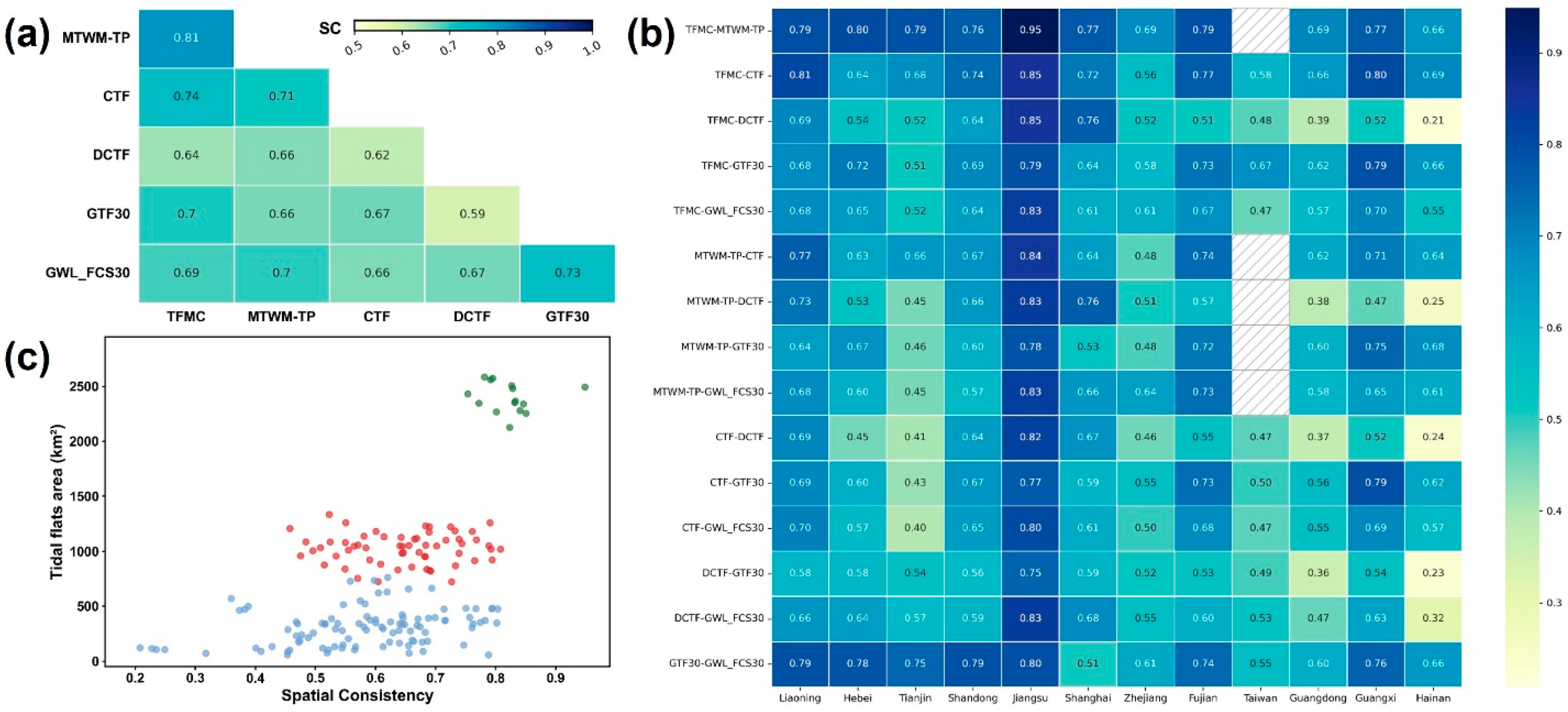

4.3. Spatial Agreement Assessment

4.4. Accuracy Assessment Using 3150 Edge Validation Points

5. Discussion

5.1. Sensor-Specific Impacts on Tidal Flat Extraction

5.2. Suppression of Inland Interference Through Tidal Flat Boundary Constraints

5.3. Local Adaptability of Spectral Indices

5.4. Robustness of Classification Approaches

5.5. Recommendations

5.5.1. Methodological Recommendations

5.5.2. Data Recommendations

5.6. Limitations and Future Perspectives

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GTF30 | Global Tidal Flats at 30 m |

| GWL_FCS30 | Global 30 m Wetland Map with a Fine Classification System |

| MTWM-TP | Multi-Class Tidal Wetland Mapping by integrating Tide-level and Phenological Features |

| DCTF | Tidal Flats Dataset Covering the Coastal Region in North of 18°N Latitude of China |

| CTF | China Tidal Flat |

| TFMC | Tidal Flats Map of China at 10 m |

| UQD | A Global Tidal Flats Product with a 30 m Resolution for the Years 1984–2016 From University of Queensland |

| FUDAN/OU | Fudan University/University of Oklahoma’s Tidal Flat Map |

| SZU | Shenzhen University’s Tidal Flat Map |

| IGSNRR | Institute of Geographical Sciences and Natural Resources Research’s Tidal Flat Map |

| OA | Overall Accuracy |

| PA | Producer’s Accuracy |

| UA | User’s Accuracy |

| GEE | Google Earth Engine |

| mNDWI | Modified Normalized Difference Water Index |

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| NDWI | Normalized Difference Water Index |

| LTideI | Low-Tide Index |

| TWDI | Tidal Flat Recognition Index |

| LSWI | Land Surface Water Index |

| AWEI | Automated Water Extraction Index |

| BSI | Bare Soil Index |

| EVI | Enhanced Vegetation Index |

| MSAVI | Modified Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Index |

| NDBI | Normalized Difference Buildup Index |

References

- Dyer, K.; Christie, M.; Wright, E. The classification of intertidal mudflats. Cont. Shelf Res. 2000, 20, 1039–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, N.J.; Phinn, S.R.; DeWitt, M.; Ferrari, R.; Johnston, R.; Lyons, M.B.; Clinton, N.; Thau, D.; Fuller, R.A. The global distribution and trajectory of tidal flats. Nature 2019, 565, 222–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, N.J.; Worthington, T.A.; Bunting, P.; Duce, S.; Hagger, V.; Lovelock, C.E.; Lucas, R.; Saunders, M.I.; Sheaves, M.; Spalding, M.; et al. High-resolution mapping of losses and gains of Earth’s tidal wetlands. Science 2022, 376, 744–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Zhou, Y.; Li, R.; Li, X. Mapping changes in coastlines and tidal flats in developing islands using the full time series of Landsat images. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 239, 111665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loke, L.H.; Todd, P.A. Structural complexity and component type increase intertidal biodiversity independently of area. Ecology 2016, 97, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nienhuis, J.H.; Ashton, A.D.; Edmonds, D.A.; Hoitink, A.J.F.; Kettner, A.J.; Rowland, J.C.; Törnqvist, T.E. Global-scale human impact on delta morphology has led to net land area gain. Nature 2020, 577, 514–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Jia, A.; Song, X.; Bai, Y. Extraction and spatiotemporal evolution analysis of tidal flats in the Bohai Rim during 1984–2019 based on remote sensing. J. Geogr. Sci. 2023, 33, 76–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, C.M.; Losada, I.J.; Hendriks, I.E.; Mazarrasa, I.; Marbà, N. The role of coastal plant communities for climate change mitigation and adaptation. Nat. Clim. Change 2013, 3, 961–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Xu, N.; Li, Y.; Li, Y. Sub-continental-scale mapping of tidal wetland composition for East Asia: A novel algorithm integrating satellite tide-level and phenological features. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 269, 112799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Dong, X.; Liu, Z.; Gao, W.; Hu, Z.; Wu, G. Mapping tidal flats with Landsat 8 images and google earth engine: A case study of the China’s eastern coastal zone circa 2015. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, D.; Wang, Z.; Wu, J.; Wu, B.; Zeng, Y.; Song, K.; Yi, K.; Luo, L. China’s wetlands loss to urban expansion. Land Degrad. Dev. 2018, 29, 2644–2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Liang, M.-J.; Chen, L.; Xu, M.-P.; Chen, X.; Geng, L.; Li, H.; Serrano, D.; Zhang, H.-Y.; Gong, Z.; et al. Processes, feedbacks, and morphodynamic evolution of tidal flat–marsh systems: Progress and challenges. Water Sci. Eng. 2022, 15, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, M.D.; Roberts, H.H. Drowning of the Mississippi Delta due to insufficient sediment supply and global sea-level rise. Nat. Geosci. 2009, 2, 488–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, D.; Liu, M.; Wang, Z.; Li, L.; Man, W.; Jia, M.; Zhang, Y. Rapid invasion of Spartina alterniflora in the coastal zone of mainland China: Spatiotemporal patterns and human prevention. Sensors 2019, 19, 2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, L.; Wang, J.; Zhao, T.; Liu, W.; Chen, X. Automated Mapping of Global 30-m Tidal Flats Using Time-Series Landsat Imagery: Algorithm and Products. J. Remote Sens. 2023, 3, 0091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, L.; Zhao, T.; Chen, X.; Lin, S.; Wang, J.; Mi, J.; Liu, W. GWL_FCS30: Global 30 m wetland map with fine classification system using multi-sourced and time-series remote sensing imagery in 2020. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2022, 15, 265–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Tian, J.; Song, J.; Chen, W.; Zhou, B.; Qu, X.; Zhang, L. Developing a new index with time series Sentinel-2 for accurate tidal flats mapping in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 958, 178037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.; Wang, Z.; Mao, D.; Ren, C.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y. Rapid, robust, and automated mapping of tidal flats in China using time series Sentinel-2 images and Google Earth Engine. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 255, 112285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhang, C.; Tian, B.; Wu, W.; Zhou, Y. Tide2Topo: A new method for mapping intertidal topography accurately in complex estuaries and bays with time-series Sentinel-2 images. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2023, 200, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFeeters, S.K. The use of the Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI) in the delineation of open water features. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1996, 17, 1425–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H. Modification of normalised difference water index (NDWI) to enhance open water features in remotely sensed imagery. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2006, 27, 3025–3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.; Li, P.; Li, Z.; Wang, H. Mapping tidal flats of the Bohai and Yellow seas using time series Sentinel-2 images and Google earth engine. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xiao, X.; Zou, Z.; Hou, L.; Qin, Y.; Dong, J.; Doughty, R.B.; Chen, B.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Y.; et al. Mapping coastal wetlands of China using time series Landsat images in 2018 and Google Earth Engine. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2020, 163, 312–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Xu, Y.; Yin, Y.; Zhang, K.; Wu, G.; Wang, C.; Cui, L.J. Tidal flats dataset covers coastal region in north of 18° N latitude of China (1989–2020). J. Glob. Change Data. Discov. 2022, 6, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Qin, C.-Z.; Teng, J. Mapping large-area tidal flats without the dependence on tidal elevations: A case study of Southern China. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2020, 159, 256–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Feng, M.; Jiang, H.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y. Validation of Land Cover Maps in China Using a Sampling-Based Labeling Approach. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 10589–10606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xiao, X.; Zou, Z.; Chen, B.; Ma, J.; Dong, J.; Doughty, R.B.; Zhong, Q.; Qin, Y.; Dai, S.; et al. Tracking annual changes of coastal tidal flats in China during 1986–2016 through analyses of Landsat images with Google Earth Engine. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 238, 110987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Xiao, P.; Feng, X.; Li, H. Accuracy assessment of seven global land cover datasets over China. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2017, 125, 156–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, G.; Xu, R.; Lu, Y. Comparison of interpolation method for high and low tidal lever extending to hourly data. Port Waterw. Eng. 2019, 9, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congalton, R.G. A review of assessing the accuracy of classifications of remotely sensed data. Remote Sens. Environ. 1991, 37, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foody, G.M. Status of land cover classification accuracy assessment. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 80, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Chen, L.; Xi, Y.; Xiao, X.; Doughty, R.B.; Liu, M.; Jia, M.; et al. Rapid expansion of coastal aquaculture ponds in China from Landsat observations during 1984–2016. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2019, 82, 101902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Matsushita, B.; Pahlevan, N.; Gurlin, D.; Lehmann, M.K.; Fichot, C.G.; Schalles, J.; Loisel, H.; Binding, C.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Remotely estimating total suspended solids concentration in clear to extremely turbid waters using a novel semi-analytical method. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 258, 112386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surisetty, V.V.A.K.; Sahay, A.; Ramakrishnan, R.; Samal, R.N.; Rajawat, A.S. Improved turbidity estimates in complex inland waters using combined NIR–SWIR atmospheric correction approach for Landsat 8 OLI data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2018, 39, 7463–7482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.-L.; Ho, C.-R.; Huang, C.-C.; Srivastav, A.L.; Tzeng, J.-H.; Lin, Y.-T. Hyperspectral sensing for turbid water quality monitoring in freshwater rivers: Empirical relationship between reflectance and turbidity and total solids. Sensors 2014, 14, 22670–22688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feyisa, G.L.; Meilby, H.; Fensholt, R.; Proud, S.R. Automated Water Extraction Index: A new technique for surface water mapping using Landsat imagery. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 140, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekar, K.; Sesha Sai, M.; Roy, P.; Dwevedi, R.S. Land Surface Water Index (LSWI) response to rainfall and NDVI using the MODIS Vegetation Index product. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2010, 31, 3987–4005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsu, N. A threshold selection method from gray-level histograms. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1979, 9, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, M.C.; Martinez, J.-M.; Peña-Luque, S. Automatic water detection from multidimensional hierarchical clustering for Sentinel-2 images and a comparison with Level 2A processors. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 253, 112209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donchyts, G.; Schellekens, J.; Winsemius, H.; Eisemann, E.; Van De Giesen, N. A 30 m resolution surface water mask including estimation of positional and thematic differences using landsat 8, srtm and openstreetmap: A case study in the Murray-Darling Basin, Australia. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dataset | Time | Range | Data Sources | Resolution | Core Index/Band | Nominal Accuracy | Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GTF30 [15] | 2000–2022 | Global | Landsat | 30 m | Landsat’s six bands, LTideI, NDVI, mNDWI, LSWI | 90.34% | Tidal flat |

| GWL_FCS30 [16] | 2020 | Global | Sentinel-1 &Landsat | 30 m | Landsat’s six bands, NDVI, mNDWI, EVI, LSWI | 86.44% | Tidal flats, Salt marshes, Mangroves, Inland wetlands |

| MTWM-TP [9] | 2020 | Esat Asia | Sentinel-2 | 10 m | Sentinel-2’s twelve bands, NDVI, NDWI | 97.02% | Tidal flats, Salt marshes, Mangroves |

| CTF [18] | 2020 | China | Sentinel-2 | 10 m | mNDWI, NDVI | 95% | Tidal flats |

| DCTF [24] | 1989–2020 | China | Landsat | 30 m | NDVI, mNDWI, LSWI, BSI, EVI, MSAVI, NDBI | 90.84% | Tidal flats, Salt marshes |

| TFMC [17] | 2020 | China | Sentinel-2 | 10 m | mNDWI, TWDI | 97% | Tidal flats |

| Province | Tidal Station | Image Sources | Overpass Times | Tidal Height (cm) | Chart Datum (cm) | Type of Tide |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liaoning | Laobeihekou | Sentinel-2 | 6 May 2020 10:56:26 | 51 | −209 | Irregular Semidiurnal |

| Daludao | Sentinel-2 | 19 January 2020 10:46:27 | 152 | −332 | Regular Semidiurnal | |

| Hebei | Caofeidian | Sentinel-2 | 11 April 2020 10:56:55 | 60 | −178 | Irregular Diurnal |

| Tianjin | Tanggu | Sentinel-2 | 24 May 2020 11:06:59 | 94 | −241 | Irregular Semidiurnal |

| Shandong | Wanwangoukou | Sentinel-2 | 8 July 2020 11:07:13 | 39 | −130 | Regular Semidiurnal |

| Dongying | Landsat 8 | 14 March 2020 10:41:49 | 62 | −100 | Irregular Semidiurnal | |

| Zhangjiabu | Sentinel-2 | 14 January 2020 10:47:28 | 10 | −220 | Irregular Semidiurnal | |

| Jiangsu | Lianyungang | Sentinel-2 | 27 December 2020 10:58:09 | 131 | −290 | Regular Semidiurnal |

| Jianggang | Sentinel-2 | 28 April 2020 10:48:31 | 97 | −301 | Regular Semidiurnal | |

| Lvsi | Sentinel-2 | 14 March 2020 10:48:46 | 135 | −310 | Regular Semidiurnal | |

| Shanghai | Zhongjun | Landsat 8 | 12 May 2020 10:24:24 | 107 | −225 | Regular Semidiurnal |

| Zhejiang | Qimengang | Sentinel-2 | 13 August 2020 10:49:37 | 295 | −379 | Regular Semidiurnal |

| Damendao | Sentinel-2 | 11 November 2020 10:40:11 | 184 | −363 | Regular Semidiurnal | |

| Fujian | Minjiangkou | Sentinel-2 | 26 August 2020 10:50:41 | 140 | −353 | Regular Semidiurnal |

| Quanzhou | Sentinel-2 | 26 August 2020 10:50:59 | 133 | −366 | Regular Semidiurnal | |

| Taiwan | Magong | Sentinel-2 | 21 November 2020 10:41:08 | 52 | −160 | Regular Semidiurnal |

| Guangdong | Chaozhougang | Sentinel-2 | 7 December 2020 11:01:11 | 59 | −101 | Irregular Semidiurnal |

| Shekou | Sentinel-2 | 20 November 2020 11:11:45 | 88 | −152 | Irregular Diurnal | |

| Zhanjiang | Sentinel-2 | 3 January 2020 11:22:02 | 154 | −220 | Irregular Semidiurnal | |

| Hainan | Xinying | Sentinel-2 | 2 May 2020 11:22:29 | 78 | −205 | Regular Diurnal |

| Guangxi | Tieshangang | Sentinel-2 | 2 May 2020 11:22:17 | 174 | −255 | Irregular Diurnal |

| Dataset | Class | TF | Non-TF | UA | OA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inland | Water | |||||

| TFMC | TF | 926 | 175 | 207 | 0.71 | 0.84 |

| Non-TF | 124 | 875 | 843 | 0.93 | ||

| PA | 0.88 | 0.83 | 0.80 | |||

| MTWM-TP | TF | 853 | 64 | 226 | 0.75 | 0.85 |

| Non-TF | 147 | 936 | 774 | 0.92 | ||

| PA | 0.85 | 0.94 | 0.77 | |||

| CTF | TF | 627 | 94 | 485 | 0.69 | 0.78 |

| Non-TF | 423 | 956 | 865 | 0.81 | ||

| PA | 0.6 | 0.91 | 0.82 | |||

| DCTF | TF | 254 | 188 | 85 | 0.48 | 0.66 |

| Non-TF | 796 | 862 | 965 | 0.7 | ||

| PA | 0.24 | 0.82 | 0.92 | |||

| GTF30 | TF | 664 | 368 | 145 | 0.56 | 0.71 |

| Non-TF | 386 | 682 | 905 | 0.8 | ||

| PA | 0.63 | 0.65 | 0.86 | |||

| GWL_FCS30 | TF | 349 | 242 | 58 | 0.54 | 0.68 |

| Non-TF | 701 | 808 | 992 | 0.72 | ||

| PA | 0.33 | 0.77 | 0.94 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Su, Q.; Lei, H.; Shen, S.; Cheng, P.; Gu, W.; Zhou, B. Evaluating Consistency and Accuracy of Public Tidal Flat Datasets in China’s Coastal Zone. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3679. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17223679

Su Q, Lei H, Shen S, Cheng P, Gu W, Zhou B. Evaluating Consistency and Accuracy of Public Tidal Flat Datasets in China’s Coastal Zone. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(22):3679. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17223679

Chicago/Turabian StyleSu, Qianqian, Hui Lei, Shiqi Shen, Pengyu Cheng, Wenxuan Gu, and Bin Zhou. 2025. "Evaluating Consistency and Accuracy of Public Tidal Flat Datasets in China’s Coastal Zone" Remote Sensing 17, no. 22: 3679. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17223679

APA StyleSu, Q., Lei, H., Shen, S., Cheng, P., Gu, W., & Zhou, B. (2025). Evaluating Consistency and Accuracy of Public Tidal Flat Datasets in China’s Coastal Zone. Remote Sensing, 17(22), 3679. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17223679