Infrared-Visible Image Fusion Meets Object Detection: Towards Unified Optimization for Multimodal Perception

Highlights

- Our proposed UniFusOD method integrates infrared-visible image fusion and object detection into a unified, end-to-end framework, achieving superior performance across multiple tasks.

- The introduction of the Fine-Grained Region Attention (FRA) module and UnityGrad optimization significantly enhances the model’s ability to handle multi-scale features and resolves gradient conflicts, improving both fusion and detection outcomes.

- The unified optimization approach not only improves image fusion quality but also enhances downstream task performance, particularly in detecting rotated and small objects.

- This approach demonstrates significant robustness across various datasets, offering a promising solution for multimodal perception tasks in remote sensing and autonomous driving.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

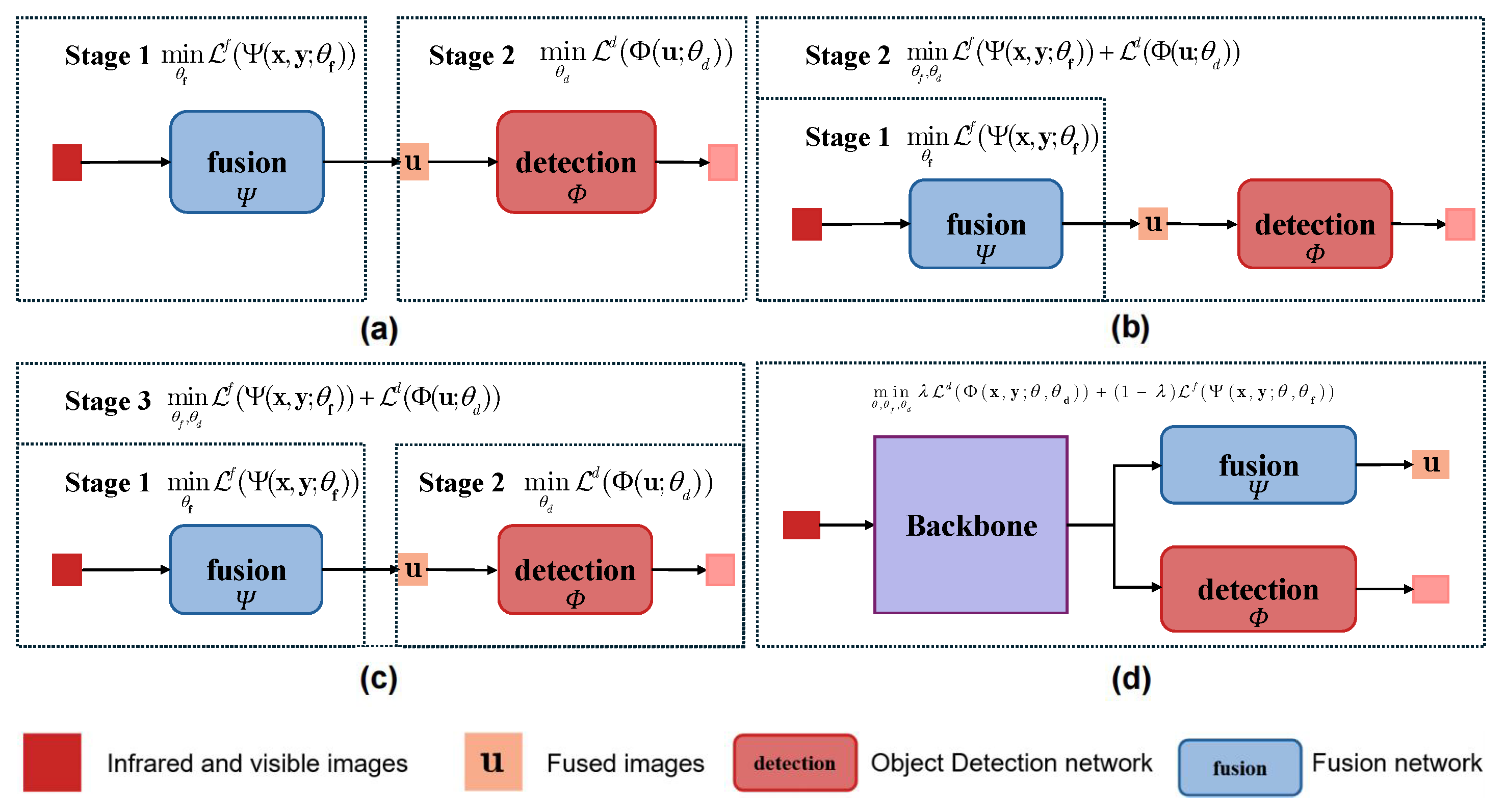

2.1. Multimodal Image Fusion and Object Detection

2.2. Multitask Learning

3. Methodology

3.1. Problem Formulation

3.2. Overall Architecture

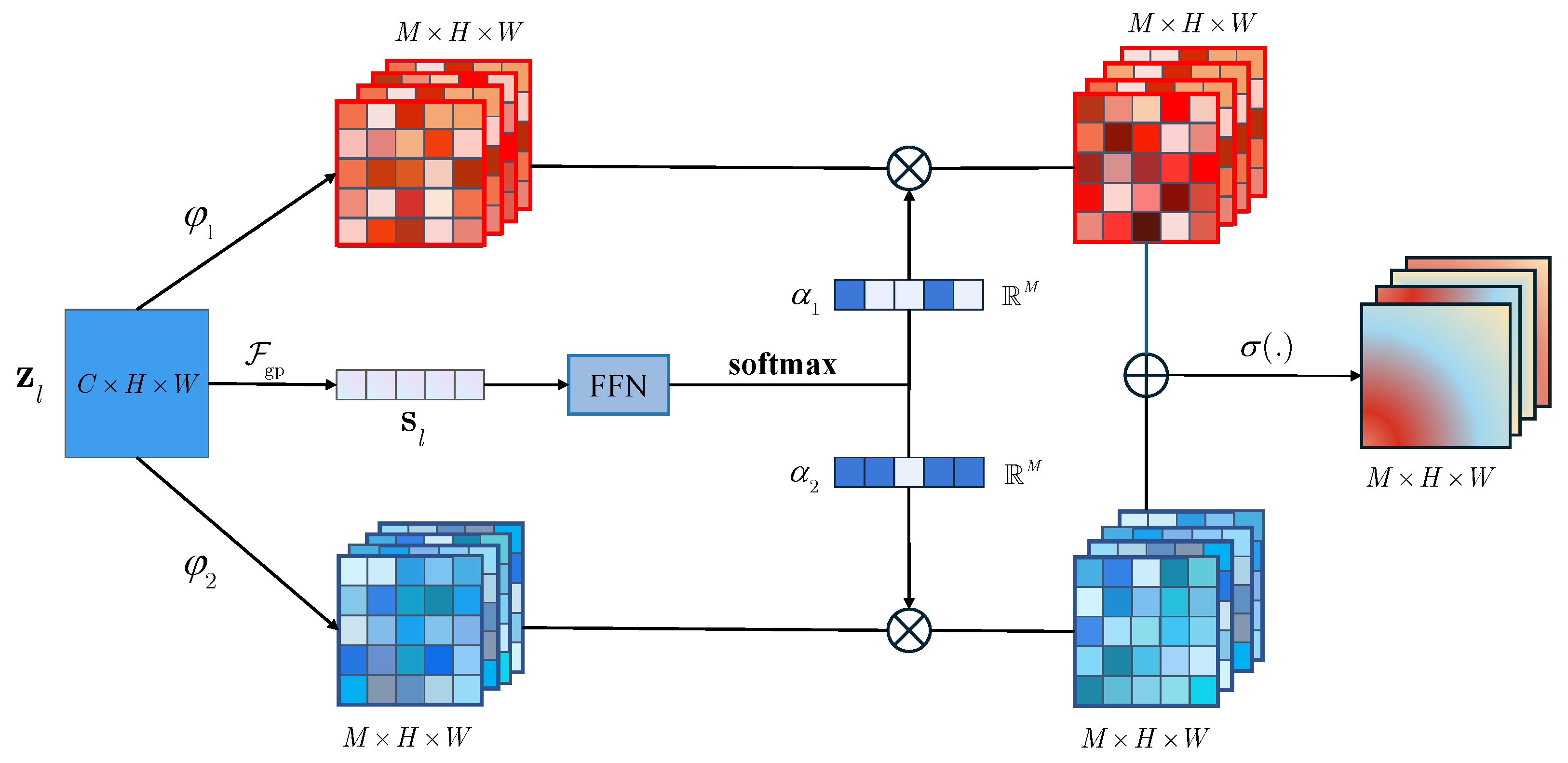

3.3. Fine-Grained Region Attention

3.4. Detection and Fusion Heads

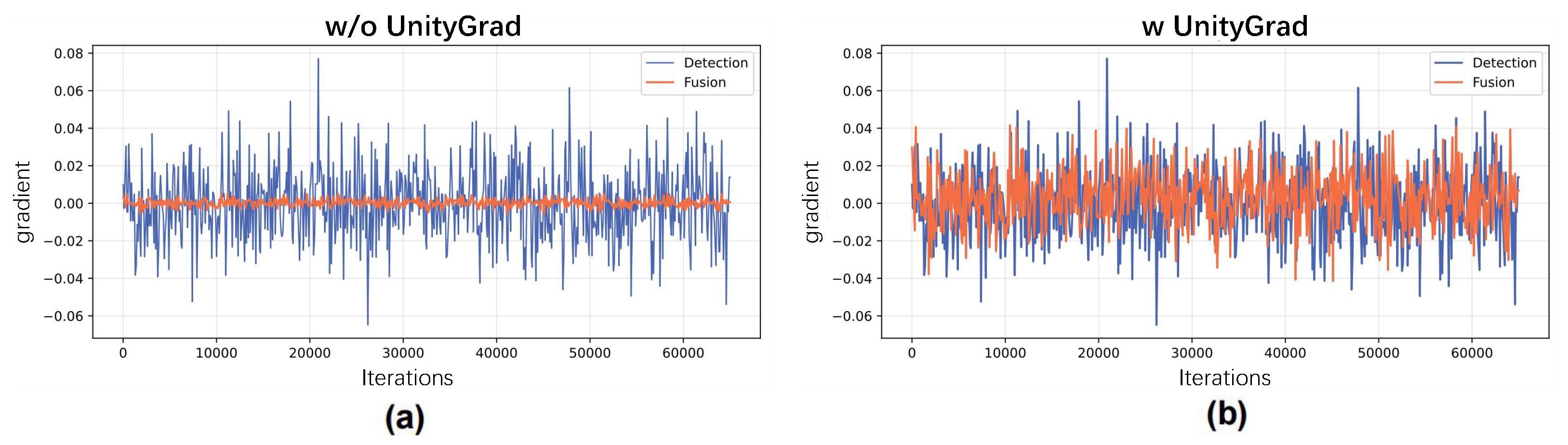

3.5. UnityGrad

| Algorithm 1 UnityGrad |

| Input: Initial shared parameters ; differentiable losses ; learning rate ; total steps T Output: for to T do Compute task gradients for to K do end for Solve for : find such that Update shared parameters end for return |

4. Experiment

4.1. Datasets and Evaluation Criteria

4.1.1. Introduction to Experimental Datasets

4.1.2. Evaluation Criteria

4.2. Implementation Details

5. Results

5.1. Results on Infrared-Visible Image Fusion

5.2. Results on Infrared-Visible Object Detection

5.3. Ablation Study Results

” indicates the module is enabled, and bold values denote the best performance.

” indicates the module is enabled, and bold values denote the best performance.6. Discussion

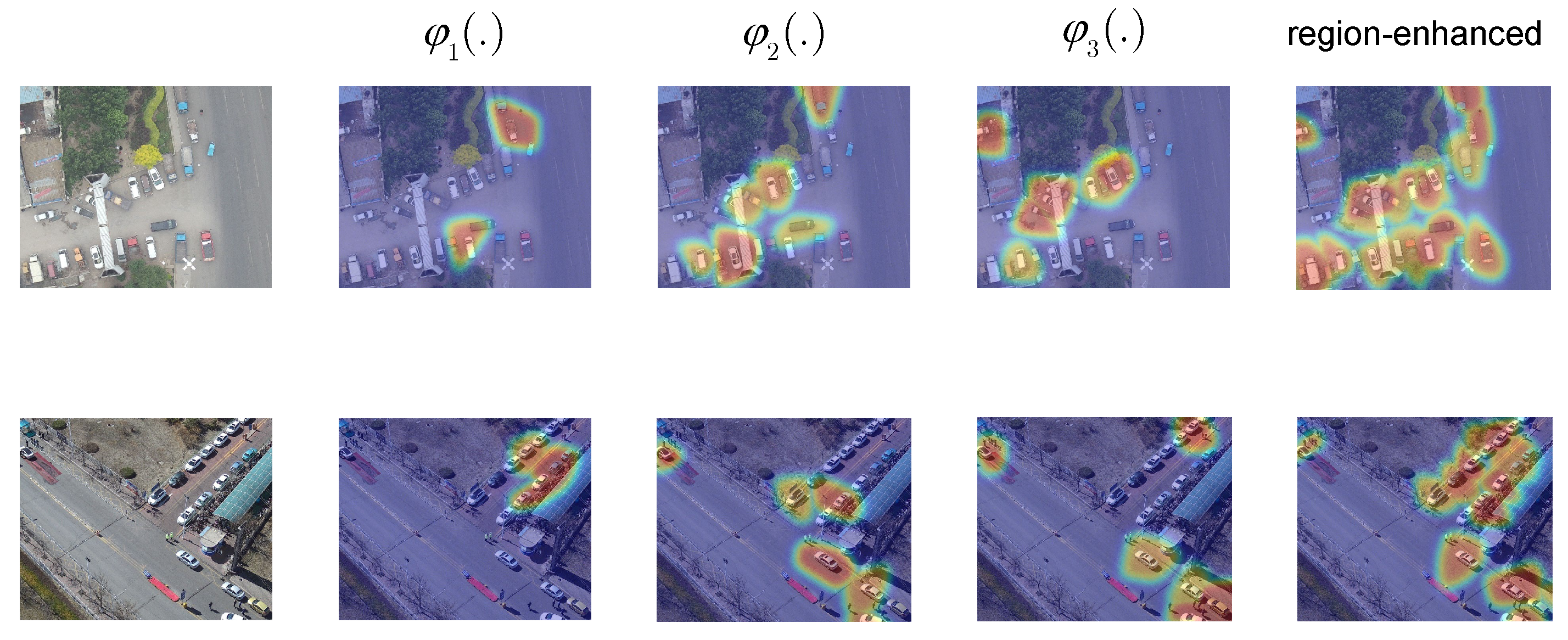

6.1. Study of Fine-Grained Region Attention

6.1.1. Effect of Different Designs

6.1.2. Effect of the Number of Region Attention Maps

6.2. Study of UnityGrad Algorithm

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, H.; Xu, H.; Tian, X.; Jiang, J.; Ma, J. Image fusion meets deep learning: A survey and perspective. Inf. Fusion 2021, 76, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ma, J. SDNet: A versatile squeeze-and-decomposition network for real-time image fusion. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2021, 129, 2761–2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, S.; Wang, S.; Metaxas, D.N. Multispectral deep neural networks for pedestrian detection. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1611.02644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wu, X.J. DenseFuse: A fusion approach to infrared and visible images. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2018, 28, 2614–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Yu, W.; Liang, P.; Li, C.; Jiang, J. FusionGAN: A generative adversarial network for infrared and visible image fusion. Inf. Fusion 2019, 48, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Demiris, Y. Visible and infrared image fusion using deep learning. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 10535–10554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.; Xu, S.; Zhang, C.; Liu, J.; Li, P.; Zhang, J. DIDFuse: Deep image decomposition for infrared and visible image fusion. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2003.09210. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.; Liang, P.; Yu, W.; Chen, C.; Guo, X.; Wu, J.; Jiang, J. Infrared and visible image fusion via detail preserving adversarial learning. Inf. Fusion 2020, 54, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Chen, L.; Cao, X. Improving multispectral pedestrian detection by addressing modality imbalance problems. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Proceedings, Part XVIII 16. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 787–803. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, M.; Cui, B.; Zhao, T.; Wei, X. UniRGB-IR: A Unified Framework for Visible-Infrared Downstream Tasks via Adapter Tuning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.17360. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.; Ruy, W. CNN-based fire detection method on autonomous ships using composite channels composed of RGB and IR data. Int. J. Nav. Archit. Ocean. Eng. 2022, 14, 100489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Hu, Z.; Feng, S.; Wang, Z.; Wu, H. GLFuse: A Global and Local Four-Branch Feature Extraction Network for Infrared and Visible Image Fusion. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wu, X.J.; Kittler, J. RFN-Nest: An end-to-end residual fusion network for infrared and visible images. Inf. Fusion 2021, 73, 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ng, M.K.; Michalski, J.; Zhuang, L. A self-supervised deep denoiser for hyperspectral and multispectral image fusion. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5520414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Xu, S.; Zhang, J.; Liang, C.; Zhang, C.; Liu, J. Efficient and model-based infrared and visible image fusion via algorithm unrolling. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2021, 32, 1186–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Zhang, D.; Wu, W.; Ma, J.; Zhou, H. A generative adversarial network for infrared and visible image fusion based on semantic segmentation. Entropy 2021, 23, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Zhang, H.; Shao, Z.; Liang, P.; Xu, H. GANMcC: A generative adversarial network with multiclassification constraints for infrared and visible image fusion. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2020, 70, 5005014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Ma, J.; Jiang, J.; Guo, X.; Ling, H. U2Fusion: A unified unsupervised image fusion network. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2020, 44, 502–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wang, X.; Ma, J. DRF: Disentangled representation for visible and infrared image fusion. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 5006713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, X.; Ren, W.; Shen, L.; Wan, S.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, Y.M. Bringing RGB and IR Together: Hierarchical Multi-Modal Enhancement for Robust Transmission Line Detection. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.15099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Han, M.; Qin, Y.; Li, Q. Self-attention progressive network for infrared and visible image fusion. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Fan, X.; Huang, Z.; Wu, G.; Liu, R.; Zhong, W.; Luo, Z. Target-aware dual adversarial learning and a multi-scenario multi-modality benchmark to fuse infrared and visible for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 5802–5811. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.; Xie, S.; Zhao, F.; He, Y.; Lu, H. Metafusion: Infrared and visible image fusion via meta-feature embedding from object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 13955–13965. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, S.; Shin, H.; Kim, H.; Park, M.; Choi, M.Y.; Oh, H. Deep learning-based human detection using rgb and ir images from drones. Int. J. Aeronaut. Space Sci. 2024, 25, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Kim, S.; Lim, H.; Lee, H.K.; Choo, H.G.; Seo, J.; Yoon, K. Performance analysis of object detection neural network according to compression ratio of RGB and IR images. J. Broadcast Eng. 2021, 26, 155–166. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, M.; Wang, Y.; Wei, X. Translation, scale and rotation: Cross-modal alignment meets RGB-infrared vehicle detection. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 509–525. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Fan, X.; Jiang, J.; Liu, R.; Luo, Z. Learning a deep multi-scale feature ensemble and an edge-attention guidance for image fusion. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2021, 32, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Liu, Z.; Liu, J.; Fan, X. Searching a hierarchically aggregated fusion architecture for fast multi-modality image fusion. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Virtual, 20–24 October 2021; pp. 1600–1608. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Lan, C.; Gao, Z. Deep Residual Fusion Network for Single Image Super-Resolution. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1693, 012164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Zhang, W.; Hou, Y.; Yu, H.; Zhu, Z.l. ECAFusion: Infrared and visible image fusion via edge-preserving and cross-modal attention mechanism. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2025, 151, 106085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; He, D. A Deep Multiscale Fusion Method via Low-Rank Sparse Decomposition for Object Saliency Detection Based on Urban Data in Optical Remote Sensing Images. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2020, 2020, 7917021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Jiang, Q.; Cai, L.; Wang, R.; Wang, P.; Jin, X. Attention-based F-UNet for Remote Sensing Image Fusion. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 23rd Int Conf on High Performance Computing & Communications; 7th Int Conf on Data Science & Systems; 19th Int Conf on Smart City; 7th Int Conf on Dependability in Sensor, Cloud & Big Data Systems & Application (HPCC/DSS/SmartCity/DependSys), Haikou, China, 20–22 December 2021; pp. 81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, L.; Yuan, J.; Ma, J. Image fusion in the loop of high-level vision tasks: A semantic-aware real-time infrared and visible image fusion network. Inf. Fusion 2022, 82, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Z.; Qiao, L. Research on Monocular Depth Estimation Algorithm Based on Structured Loss. J. Univ. Electron. Sci. Technol. China 2021, 50, 728–733. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, L.; Fan, H.; Li, J. A multi-focus image fusion method based on attention mechanism and supervised learning. Appl. Intell. 2022, 52, 339–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, Z.; Wu, G.; Ma, L.; Liu, R.; Zhong, W.; Luo, Z.; Fan, X. Multi-interactive feature learning and a full-time multi-modality benchmark for image fusion and segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 2–6 October 2023; pp. 8115–8124. [Google Scholar]

- Senushkin, D.; Patakin, N.; Kuznetsov, A.; Konushin, A. Independent component alignment for multi-task learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 20083–20093. [Google Scholar]

- Caruana, R. Multitask learning. Mach. Learn. 1997, 28, 41–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, Q. A survey on multi-task learning. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2021, 33, 2739–2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, R.; Dengler, N.; Pan, S.; Chenchani, G.K.; Bennewitz, M. EvidMTL: Evidential Multi-Task Learning for Uncertainty-Aware Semantic Surface Mapping from Monocular RGB Images. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.04441. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, H.; Zhang, P.; Wu, Y.; Wang, B. A Mutual Information Constrained Multi-Task Learning Method for Very High-Resolution Building Segmentation. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 9230–9243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Luo, P.; Loy, C.C.; Tang, X. Facial landmark detection by deep multi-task learning. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2014: 13th European Conference, Zurich, Switzerland, 6–12 September 2014; Proceedings, Part VI 13. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 94–108. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Tsvetkov, Y.; Firat, O.; Cao, Y. Gradient vaccine: Investigating and improving multi-task optimization in massively multilingual models. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.05874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Xu, H.; Wu, Y.; Wang, X. Multi-task reinforcement learning with soft modularization. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 4767–4777. [Google Scholar]

- Maninis, K.K.; Radosavovic, I.; Kokkinos, I. Attentive single-tasking of multiple tasks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 1851–1860. [Google Scholar]

- Crawshaw, M. Multi-Task Learning with Deep Neural Networks: A Survey. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2009.09796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bairaktari, K.; Blanc, G.; Tan, L.Y.; Ullman, J.; Zakynthinou, L. Multitask Learning via Shared Features: Algorithms and Hardness. In Proceedings of the Thirty Sixth Conference on Learning Theory, Bangalore, India, 12–15 July 2023; pp. 747–772. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, Q. An overview of multi-task learning. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2017, 5, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, A.; Gal, Y.; Cipolla, R. Multi-task learning using uncertainty to weigh losses for scene geometry and semantics. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 7482–7491. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Badrinarayanan, V.; Lee, C.Y.; Rabinovich, A. Gradnorm: Gradient normalization for adaptive loss balancing in deep multitask networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018; pp. 794–803. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Li, Y.; Kuang, Z.; Xue, J.; Chen, Y.; Yang, W.; Liao, Q.; Zhang, W. Towards impartial multi-task learning. In Proceedings of the ICLR, Vienna, Austria, 4 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.; Czarnecki, W.M.; Jayakumar, S.M.; Farajtabar, M.; Pascanu, R.; Lakshminarayanan, B. Adapting auxiliary losses using gradient similarity. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1812.02224. [Google Scholar]

- Panageas, I.; Piliouras, G.; Wang, X. First-order methods almost always avoid saddle points: The case of vanishing step-sizes. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.07772. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Liu, X.; Jin, X.; Stone, P.; Liu, Q. Conflict-averse gradient descent for multi-task learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 18878–18890. [Google Scholar]

- Bragman, F.J.; Tanno, R.; Ourselin, S.; Alexander, D.C.; Cardoso, J. Stochastic filter groups for multi-task cnns: Learning specialist and generalist convolution kernels. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 1385–1394. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, C.; Kim, E.; Oh, S. Deep elastic networks with model selection for multi-task learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 6529–6538. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum, C.; Klinger, T.; Riemer, M. Routing networks: Adaptive selection of non-linear functions for multi-task learning. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1711.01239. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.; Dai, Y.; Liu, X.; Huang, J.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, K.; Zhou, R.; Adhikarla, E.; Ye, W.; Liu, Y.; et al. Unleashing the power of multi-task learning: A comprehensive survey spanning traditional, deep, and pretrained foundation model eras. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.18961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotegni, S.S.; Berkemeier, M.; Peitz, S. Multi-objective optimization for sparse deep multi-task learning. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Yokohama, Japan, 30 June–5 July 2024; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Garber, D.; Kretzu, B. Projection-free online convex optimization with time-varying constraints. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.08799. [Google Scholar]

- Nash, J. Two-person cooperative games. Econom. J. Econom. Soc. 1953, 21, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navon, A.; Shamsian, A.; Achituve, I.; Maron, H.; Kawaguchi, K.; Chechik, G.; Fetaya, E. Multi-task learning as a bargaining game. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2202.01017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Cao, B.; Zhu, P.; Hu, Q. Drone-based RGB-infrared cross-modality vehicle detection via uncertainty-aware learning. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2022, 32, 6700–6713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toet, A. The TNO multiband image data collection. Data Brief 2017, 15, 249–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Bai, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, S.; Lin, Z.; Timofte, R.; Van Gool, L. Cddfuse: Correlation-driven dual-branch feature decomposition for multi-modality image fusion. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 5906–5916. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, H.; Tang, F.; Chen, Z.; Chang, H.J.; Gao, Y. AMDANet: Attention-Driven Multi-Perspective Discrepancy Alignment for RGB-Infrared Image Fusion and Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Honolulu, HI, USA, 19–25 October 2025; pp. 10645–10655. [Google Scholar]

- He, D.; Li, W.; Wang, G.; Huang, Y.; Liu, S. MMIF-INet: Multimodal medical image fusion by invertible network. Inf. Fusion 2025, 114, 102666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Cheng, G.; Wang, J.; Yao, X.; Han, J. Oriented R-CNN for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 3520–3529. [Google Scholar]

- Ultralytics. Ultralytics/yolov5: v3.1—Bug Fixes and Performance Improvements. Zenodo 2020. [CrossRef]

- Girshick, R. Fast r-cnn. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 1440–1448. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, J.; Xue, N.; Long, Y.; Xia, G.S.; Lu, Q. Learning RoI transformer for oriented object detection in aerial images. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 2849–2858. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, L.; Wang, W. Mbnet: A multi-resolution branch network for semantic segmentation of ultra-high resolution images. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2022—2022 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Singapore, Singapore, 22–27 May 2022; pp. 2589–2593. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, M.; Wei, X. C2former: Calibrated and complementary transformer for rgb-infrared object detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5403712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Guan, X.; Zhao, B.; Ni, L.; Huang, M. Vehicle detection based on adaptive multimodal feature fusion and cross-modal vehicle index using RGB-T images. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2023, 16, 8166–8177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, J.; Wang, Q.; Liu, J.; Qu, X.; Song, J.; Shen, T. Multi-modal and cross-scale feature fusion network for vehicle detection with transformers. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Machine Vision, Image Processing and Imaging Technology (MVIPIT), Hangzhou, China, 26–28 July 2023; pp. 175–180. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, J.; Jin, P.; Wang, Q. Multimodal feature-guided pre-training for RGB-T perception. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 16041–16050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Cao, B.; Zhu, P.; Hu, Q. Detfusion: A detection-driven infrared and visible image fusion network. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Lisboa, Portugal, 10–14 October 2022; pp. 4003–4011. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Chen, J.; Liu, J.; Ma, H. Learning a graph neural network with cross modality interaction for image fusion. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 29 October–3 November 2023; pp. 4471–4479. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, L.; Deng, Y.; Ma, Y.; Huang, J.; Ma, J. SuperFusion: A versatile image registration and fusion network with semantic awareness. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2022, 9, 2121–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Wang, D.; Hu, Z.; Li, S.; Ni, W.; Zhao, L.; Wang, Q. Fd2-net: Frequency-driven feature decomposition network for infrared-visible object detection. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 25 February–4 March 2025; Volume 39, pp. 4797–4805. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, W.; Zhu, H.; Lin, S.; Luo, X.; Shen, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Guo, G.; Zhang, B. Fusion-mamba for cross-modality object detection. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.09146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Kumar, S.; Gupta, A.; Levine, S.; Hausman, K.; Finn, C. Gradient Surgery for Multi-Task Learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 5824–5836. [Google Scholar]

| Model | EN | SD | MI | VIF | SSIM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DIDFuse | 6.97 | 45.12 | 1.70 | 0.60 | 0.81 |

| U2Fusion | 6.83 | 34.55 | 1.37 | 0.58 | 0.99 |

| SDNet | 6.64 | 32.66 | 1.52 | 0.56 | 1.00 |

| RFN-Nest | 6.83 | 34.50 | 1.20 | 0.51 | 0.92 |

| TarDAL | 6.84 | 45.63 | 1.86 | 0.53 | 0.88 |

| DenseFuse | 6.95 | 38.41 | 1.78 | 0.60 | 0.96 |

| MMIF-INet | 6.88 | 39.27 | 1.69 | 0.56 | 0.83 |

| FusinoGAN | 7.10 | 44.85 | 1.78 | 0.57 | 0.88 |

| AMDANet | 7.37 | 39.52 | 1.82 | 0.70 | 0.95 |

| CDDFuse | 7.12 | 46.00 | 2.19 | 0.77 | 1.03 |

| UniFusOD | 7.44 | 41.28 | 2.00 | 0.79 | 1.07 |

| Model | EN | SD | MI | VIF | SSIM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DIDFuse | 7.43 | 51.58 | 2.11 | 0.58 | 0.86 |

| U2Fusion | 7.09 | 38.12 | 1.87 | 0.60 | 0.97 |

| SDNet | 7.14 | 40.20 | 2.21 | 0.60 | 0.99 |

| RFN-Nest | 7.21 | 41.25 | 1.68 | 0.54 | 0.90 |

| TarDAL | 7.17 | 47.44 | 2.14 | 0.54 | 0.88 |

| DenseFuse | 7.23 | 44.44 | 2.25 | 0.63 | 0.89 |

| MMIF-INet | 7.24 | 49.75 | 2.05 | 0.61 | 0.78 |

| FusionGAN | 7.36 | 52.54 | 2.18 | 0.59 | 0.88 |

| AMDANet | 7.43 | 53.77 | 1.92 | 0.73 | 0.81 |

| CDDFuse | 7.44 | 54.67 | 2.30 | 0.69 | 0.98 |

| UniFusOD | 7.47 | 59.48 | 1.96 | 0.84 | 0.90 |

| Model | EN | SD | MI | SSIM | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DIDFuse | 5.97 | 41.78 | 1.37 | 0.81 | 0.54 |

| U2Fusion | 5.62 | 36.51 | 1.20 | 0.99 | 0.50 |

| SDNet | 6.21 | 34.22 | 1.24 | 1.00 | 0.61 |

| RFN-Nest | 6.01 | 37.59 | 1.01 | 0.92 | 0.51 |

| TarDAL | 5.84 | 40.18 | 1.37 | 0.88 | 0.59 |

| DenseFuse | 6.44 | 36.46 | 1.23 | 0.96 | 0.57 |

| MMIF-INet | 5.74 | 40.67 | 1.18 | 0.96 | 0.55 |

| FusionGAN | 6.30 | 39.83 | 1.16 | 0.88 | 0.53 |

| AMDANet | 6.51 | 38.27 | 1.31 | 0.97 | 0.72 |

| CDDFuse | 5.77 | 39.74 | 1.33 | 0.91 | 0.69 |

| UniFusOD | 6.60 | 42.52 | 1.40 | 0.85 | 0.68 |

| Methods | Modality | Car | Truck | Freight-Car | Bus | Van | mAP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Faster R-CNN [70] | Visible | 79.0 | 49.0 | 37.2 | 77.0 | 37.0 | 55.9 |

| RoITransformer [71] | Visible | 61.6 | 55.1 | 42.3 | 85.5 | 44.8 | 61.6 |

| YOLOv5s [69] | Visible | 78.6 | 55.3 | 43.8 | 87.1 | 46.0 | 62.1 |

| Faster R-CNN | IR | 89.4 | 53.5 | 48.3 | 87.0 | 42.6 | 64.2 |

| RoITransformer | IR | 90.1 | 60.4 | 58.9 | 89.7 | 52.2 | 70.3 |

| YOLOv5s | IR | 90.0 | 59.5 | 60.8 | 89.5 | 53.8 | 70.7 |

| Halfway Fusion [3] | Visible + IR | 90.1 | 62.3 | 58.5 | 89.1 | 49.8 | 70.0 |

| UA-CMDet [63] | Visible + IR | 88.6 | 73.1 | 57.0 | 88.5 | 54.1 | 70.0 |

| MBNet [72] | Visible + IR | 90.1 | 64.4 | 62.4 | 88.8 | 53.6 | 71.9 |

| TSFADet [26] | Visible + IR | 89.9 | 67.9 | 63.7 | 89.8 | 54.0 | 73.1 |

| C2Former [73] | Visible + IR | 90.2 | 78.3 | 64.4 | 89.8 | 58.5 | 74.2 |

| AFFCM [74] | Visible + IR | 90.2 | 73.4 | 64.9 | 89.9 | 64.9 | 76.6 |

| MC-DETR [75] | Visible + IR | 94.8 | 76.7 | 60.4 | 91.1 | 61.4 | 76.9 |

| M2FP [76] | Visible + IR | 95.7 | 76.2 | 64.7 | 92.1 | 64.7 | 78.7 |

| UniFusOD (Oriented RCNN) | Visible + IR | 96.4 | 81.3 | 63.5 | 90.8 | 65.6 | 79.5 |

| Methods | Detector | mAP50 | mAP | People | Bus | Car | Motorcycle | Lamp | Truck |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DIDFuse [7] | YOLOv5 | 78.9 | 52.6 | 79.6 | 79.6 | 92.5 | 68.7 | 84.7 | 68.7 |

| SDNet [2] | YOLOv5 | 79.0 | 52.9 | 79.4 | 81.4 | 92.3 | 67.4 | 84.1 | 69.3 |

| RFNet [13] | YOLOv5 | 79.4 | 53.2 | 79.4 | 78.2 | 91.1 | 72.8 | 85.0 | 69.0 |

| TarDAL [22] | YOLOv5 | 80.5 | 54.1 | 81.5 | 81.3 | 94.8 | 69.3 | 87.1 | 68.7 |

| DetFusion [77] | YOLOv5 | 80.8 | 53.8 | 80.8 | 83.0 | 92.5 | 69.4 | 87.8 | 71.4 |

| CDDFuse [65] | YOLOv5 | 81.1 | 54.3 | 81.6 | 82.6 | 92.5 | 71.6 | 86.9 | 71.5 |

| IGNet [78] | YOLOv5 | 81.5 | 54.5 | 81.6 | 82.4 | 92.8 | 73.0 | 86.9 | 72.1 |

| SuperFusion [79] | YOLOv7 | 83.5 | 56.0 | 83.7 | 93.2 | 91.0 | 77.4 | 70.0 | 85.8 |

| Fd2-Net [80] | YOLOv5 | 83.5 | 55.7 | 82.7 | 82.7 | 93.6 | 78.1 | 87.8 | 73.7 |

| Fusion-Mamba [81] | YOLOv5 | 85.0 | 57.5 | 80.3 | 92.8 | 91.9 | 73.0 | 84.8 | 87.1 |

| UniFusOD | YOLOv5 | 86.9 | 59.4 | 83.4 | 94.1 | 95.0 | 77.8 | 88.6 | 82.4 |

” denotes that the module is enabled.

” denotes that the module is enabled.

” denotes that the module is enabled.

” denotes that the module is enabled.| Baseline | FRA | UnityGrad | EN | SD | MI | VIF | SSIM | mAP50 | mAP50:95 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.21 | 37.68 | 1.21 | 0.52 | 0.76 | 83.3 | 57.1 | ||

|  | 6.44 | 37.55 | 1.15 | 0.64 | 0.68 | 86.0 | 58.7 | |

|  |  | 6.60 | 42.52 | 1.40 | 0.68 | 0.85 | 86.9 | 59.4 |

| Number of (K) | EN | SD | MI | VIF | mAP50 | mAP50:95 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (no region attention) | 6.44 | 37.55 | 1.15 | 0.64 | 86.0 | 58.7 |

| 1 (3 × 3) | 6.42 | 37.86 | 1.38 | 0.62 | 86.2 | 59.0 |

| 2 (3 × 3, 5 × 5) | 6.41 | 40.25 | 1.38 | 0.68 | 86.7 | 59.1 |

| 3 (3 × 3, 5 × 5, 7 × 7) | 6.60 | 42.52 | 1.40 | 0.68 | 86.9 | 59.4 |

| 4 (3 × 3, 5 × 5, 7 × 7, 11 × 11) | 6.52 | 39.88 | 1.37 | 0.66 | 86.2 | 58.9 |

| M | EN | SD | MI | VIF | SSIM | mAP50 | mAP50:95 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 6.30 | 37.00 | 1.10 | 0.62 | 0.68 | 85.8 | 58.5 |

| 4 | 6.35 | 37.30 | 1.30 | 0.61 | 0.72 | 86.0 | 58.7 |

| 6 | 6.38 | 39.00 | 1.35 | 0.65 | 0.75 | 86.5 | 59.0 |

| 8 | 6.60 | 42.52 | 1.40 | 0.68 | 0.85 | 86.9 | 59.4 |

| 10 | 6.40 | 39.50 | 1.35 | 0.64 | 0.73 | 86.0 | 58.8 |

| Method | EN | SD | MI | VIF | SSIM | mAP50 | mAP50:95 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GradNorm | 6.21 | 38.60 | 1.29 | 0.57 | 0.70 | 86.1 | 58.7 |

| PCGrad | 6.51 | 39.92 | 1.35 | 0.63 | 0.79 | 86.1 | 59.0 |

| CAGrad | 6.47 | 40.77 | 1.36 | 0.66 | 0.84 | 86.3 | 58.8 |

| UniGrad | 6.60 | 42.52 | 1.40 | 0.68 | 0.85 | 86.9 | 59.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiang, X.; Zhou, G.; Niu, B.; Pan, Z.; Huang, L.; Li, W.; Wen, Z.; Qi, J.; Gao, W. Infrared-Visible Image Fusion Meets Object Detection: Towards Unified Optimization for Multimodal Perception. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3637. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17213637

Xiang X, Zhou G, Niu B, Pan Z, Huang L, Li W, Wen Z, Qi J, Gao W. Infrared-Visible Image Fusion Meets Object Detection: Towards Unified Optimization for Multimodal Perception. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(21):3637. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17213637

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiang, Xiantai, Guangyao Zhou, Ben Niu, Zongxu Pan, Lijia Huang, Wenshuai Li, Zixiao Wen, Jiamin Qi, and Wanxin Gao. 2025. "Infrared-Visible Image Fusion Meets Object Detection: Towards Unified Optimization for Multimodal Perception" Remote Sensing 17, no. 21: 3637. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17213637

APA StyleXiang, X., Zhou, G., Niu, B., Pan, Z., Huang, L., Li, W., Wen, Z., Qi, J., & Gao, W. (2025). Infrared-Visible Image Fusion Meets Object Detection: Towards Unified Optimization for Multimodal Perception. Remote Sensing, 17(21), 3637. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17213637