Windthrow Mapping with Sentinel-2 and PlanetScope in Triglav National Park: A Regional Case Study

Highlights

- Within-sample overall accuracy for PlanetScope 72.9% (95% CI: 71.2–74.6%) and Sentinel-2 69.2% (95% CI: 67.4–71.2%) in this alpine regional case study.

- Detection was size-dependent: gaps larger than 0.5 ha were consistently detected, while gaps smaller than 0.1 ha were frequently omitted. Omissions were higher for Sentinel-2 and lower for PlanetScope, indicating a modest advantage for smaller fragmented patches in this sample.

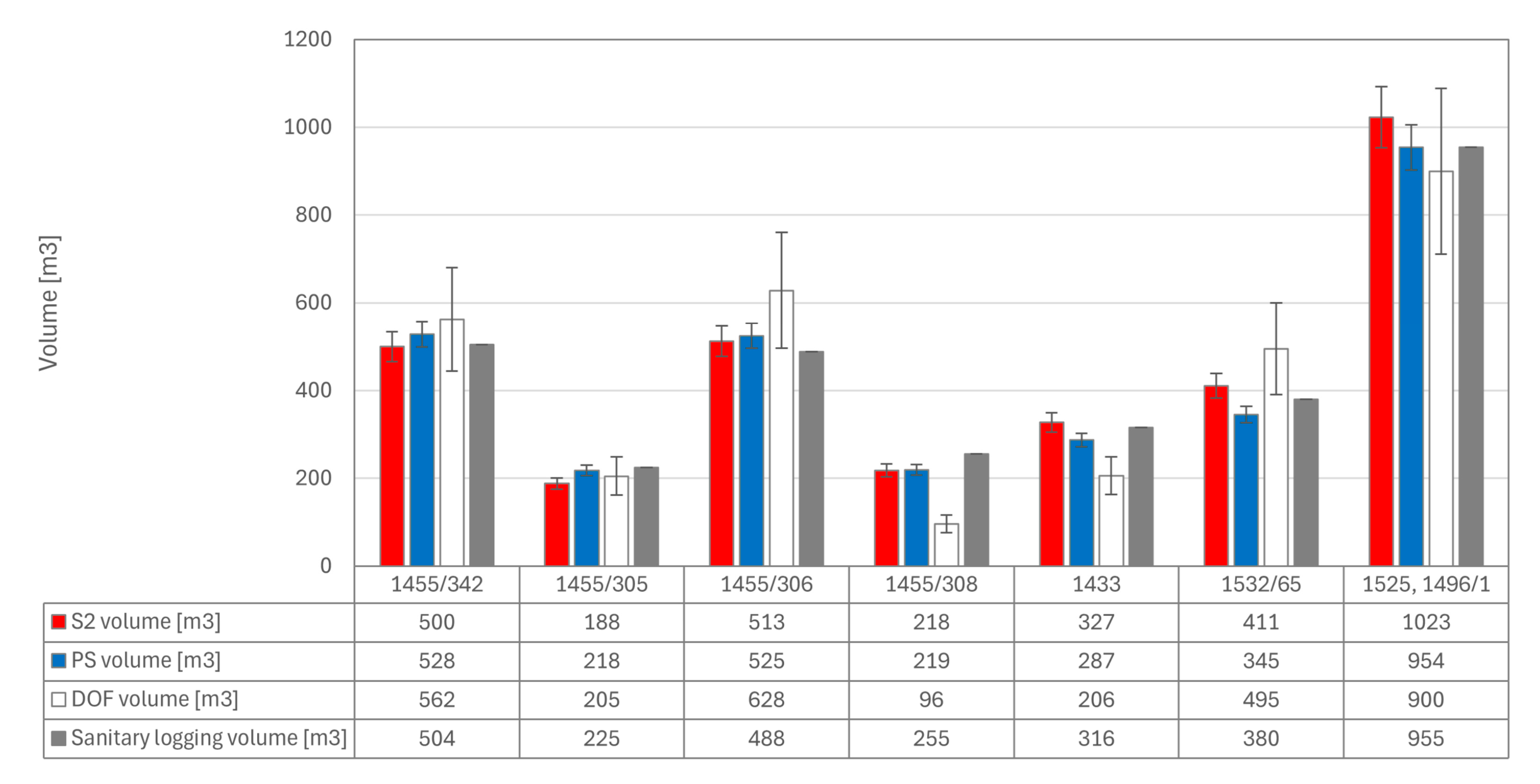

- Linking satellite-derived change maps with available forest stand data enabled parcel-level estimates of damaged timber volume. Across n = 8 non-probability parcels, compared with official sanitary-logging records, mean absolute deviations were 5–7%; these figures are preliminary and not generalisable.

- The study documents within-sample performance from a regional case study in alpine terrain. Any broader generalisation will require larger, probability-based validation across additional events and forest types, as well as broader access to parcel-level official records.

- In our sample, PlanetScope omitted fewer smaller fragmented gaps than Sentinel-2, while gaps smaller than 0.1 ha often required field verification or VHR/UAV follow-up. The reported bootstrap confidence intervals express within-sample uncertainty and do not constitute operational performance guarantees.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

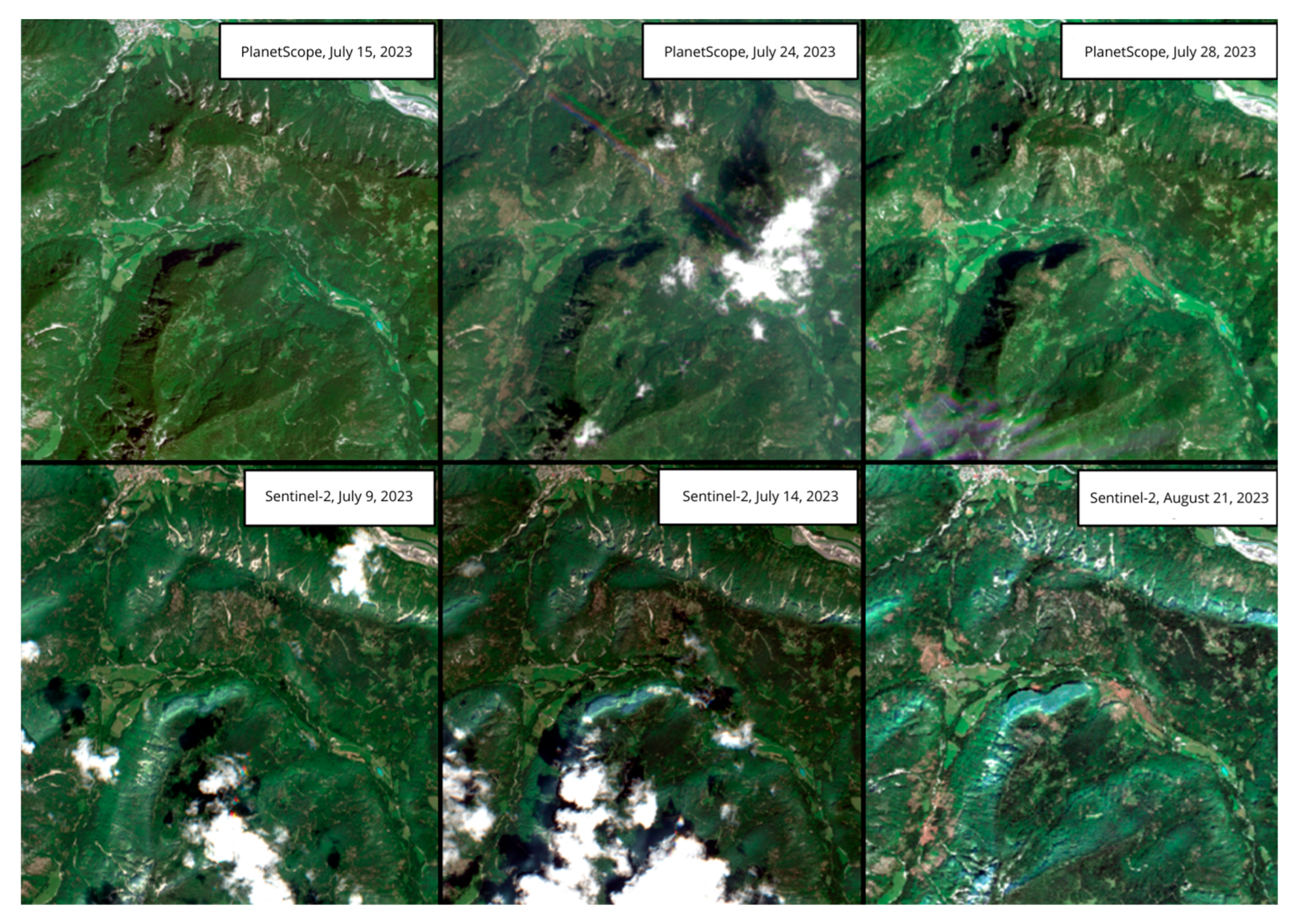

2.2. Satellite Images Dataset

2.2.1. Sentinel-2 Data

2.2.2. PlanetScope Data

2.3. Ancillary Data

- A forest stand map of Slovenia, provided by the Slovenian Forestry Institute (SFI) in a vector format, was used to estimate the volume of damaged timber. The database is updated on a 10-year cycle, with approximately 10% of the national forest area revised each year. For the study area analysed in this research, the most recent update corresponds to 2021. As no more recent data were available, this may introduce a potential bias in cases where forest stand conditions have changed since the last update.

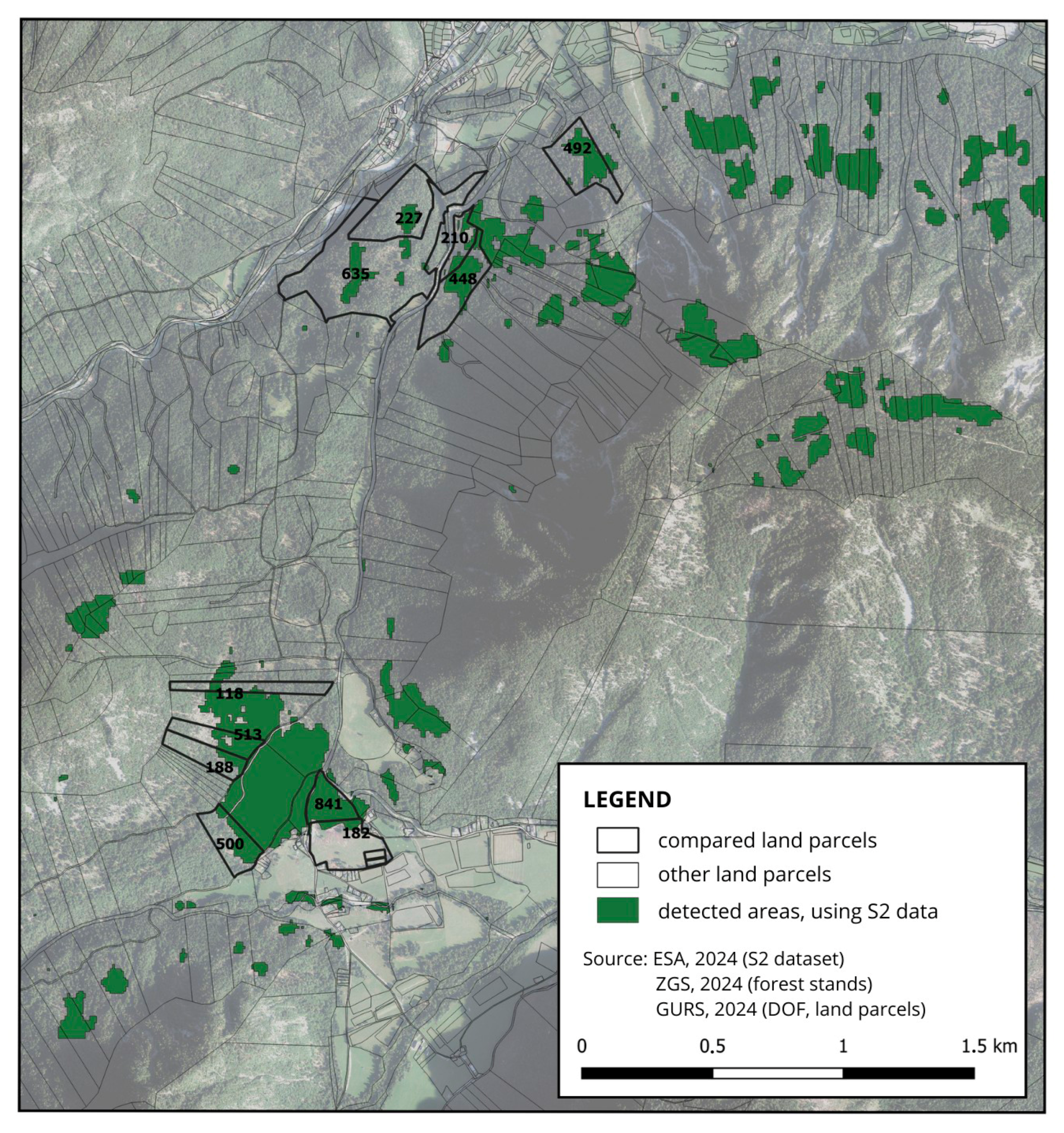

- Digital Orthophoto (DOF) of Slovenia—Acquired in August 2023 by the Surveying and Mapping Authority of the Republic of Slovenia (GURS) [25]. DOF was used as a reference dataset for validating the change detection results. Manually digitised polygons derived from DOF served as reference data.

- Administrative and cadastral layers—Municipality, cadastral municipality, and land parcel boundaries, provided by GURS, were used to assess storm damage at smaller administrative units and to compare with in situ data.

- In situ timber data—Field data on damaged timber volume per land parcel, provided by the Slovenia Forest Service (SFS), were used for validation of volume estimates [26].

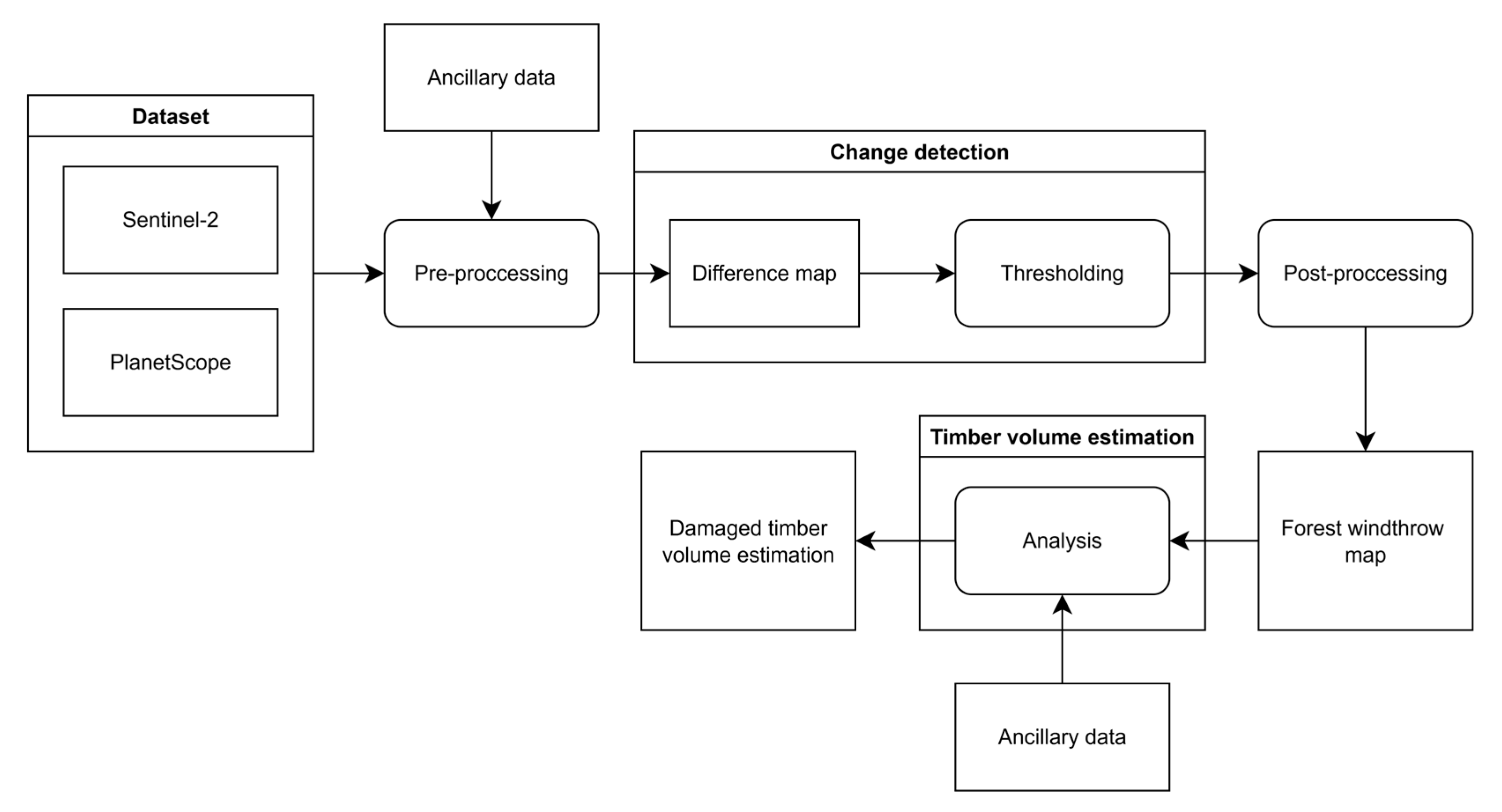

2.4. Methods

2.4.1. Data Pre-Processing

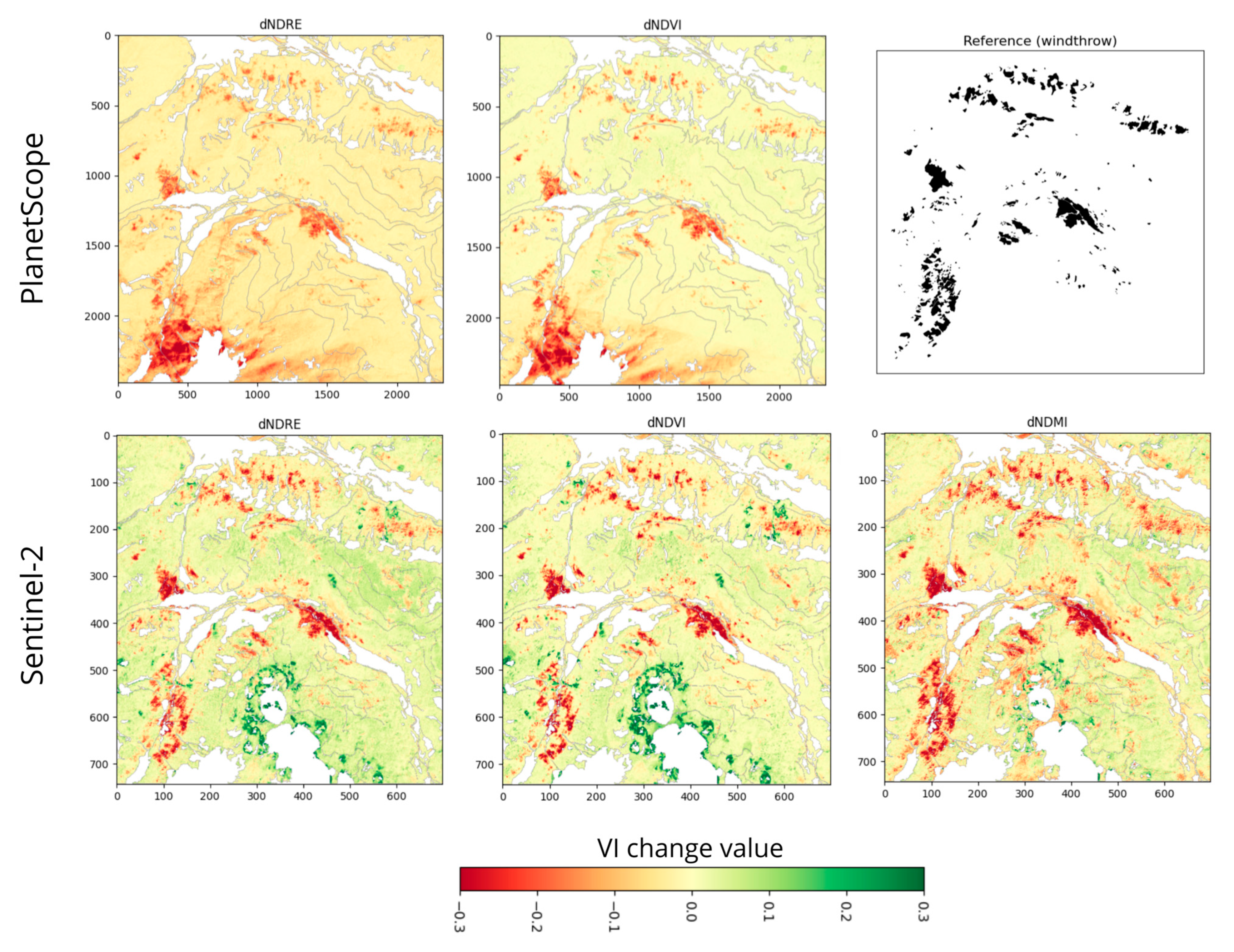

2.4.2. Windthrow Detection

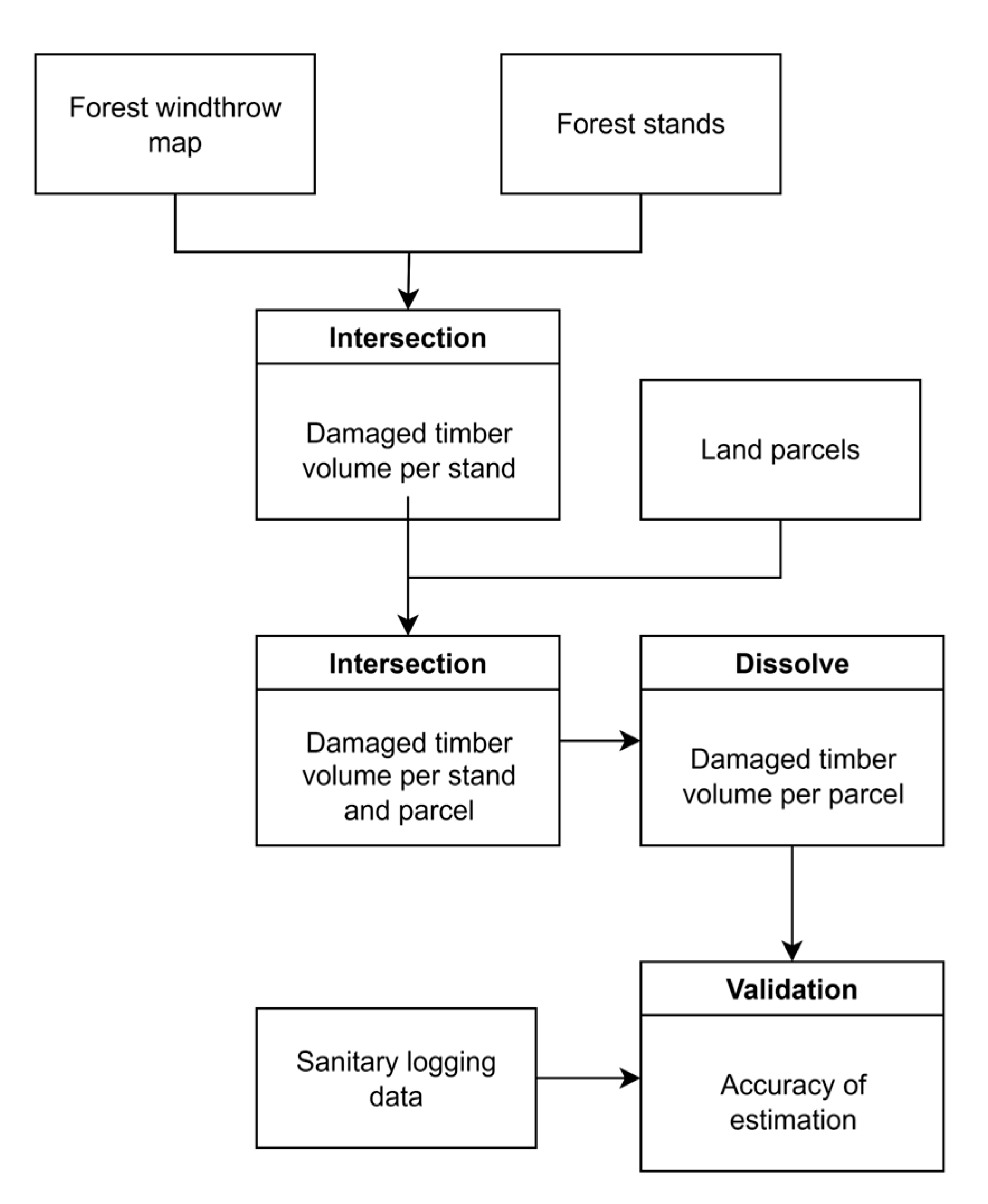

2.4.3. Post-Processing for Damaged Timber Volume Estimation

3. Results

3.1. Threshold Selection

3.2. Sensitivity Analysis of Thresholds

3.3. Accuracy Assessment

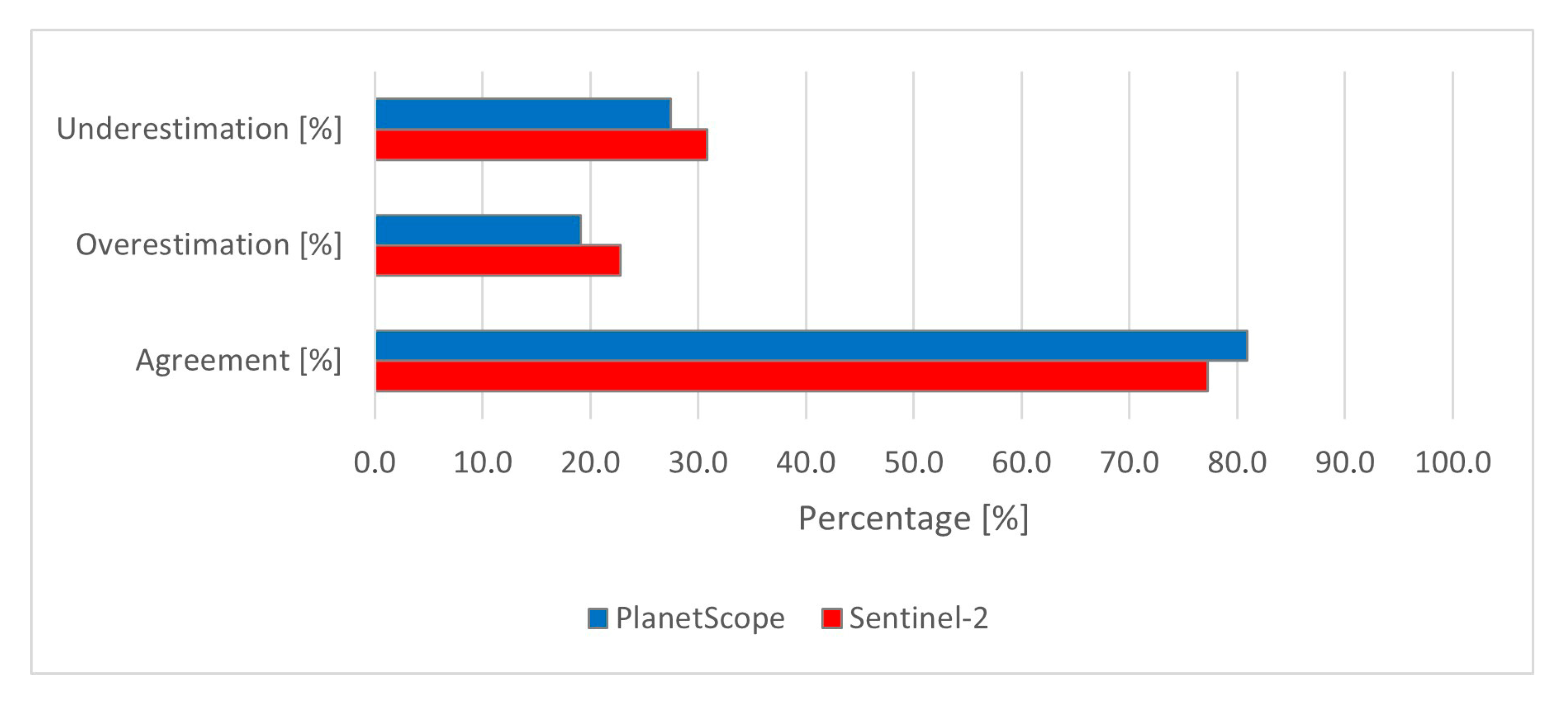

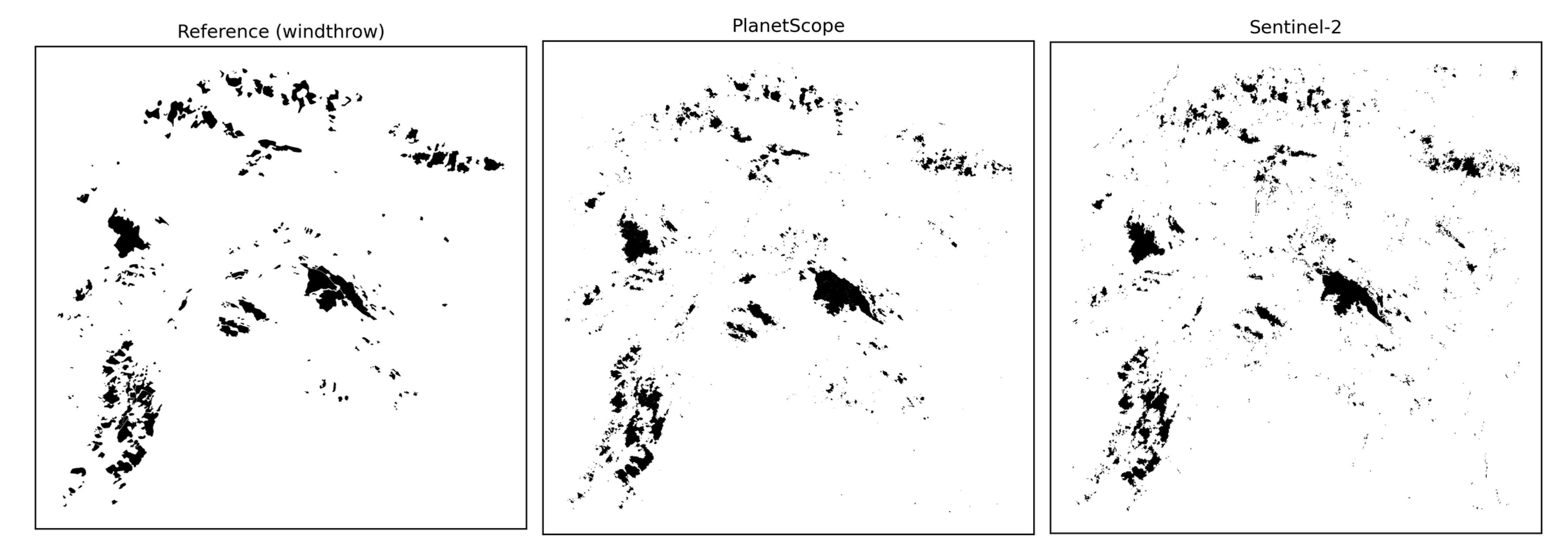

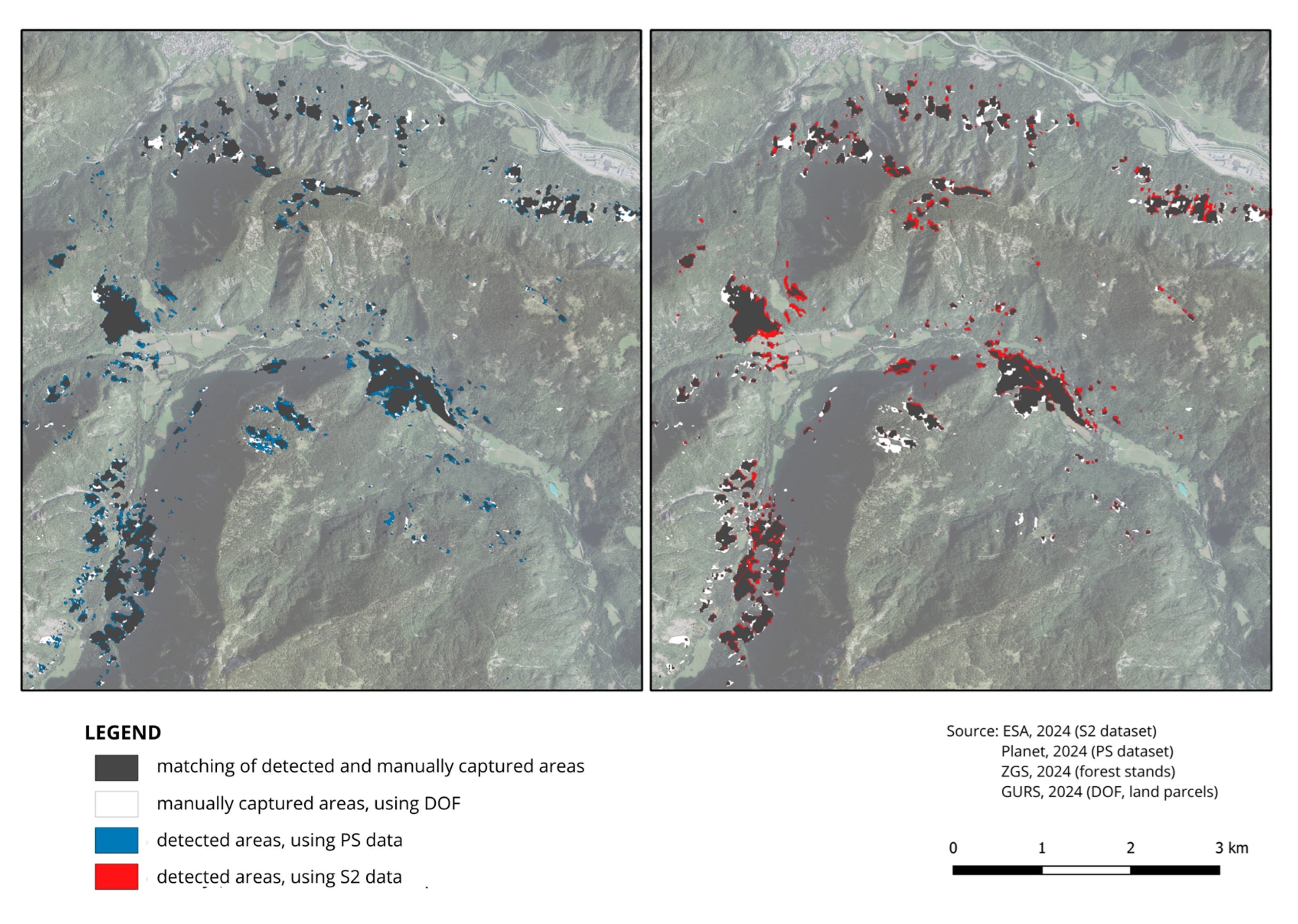

3.3.1. Spatial Agreement with Reference Polygons

3.3.2. Bootstrap Accuracy and Confidence Intervals

3.3.3. Omission Analysis

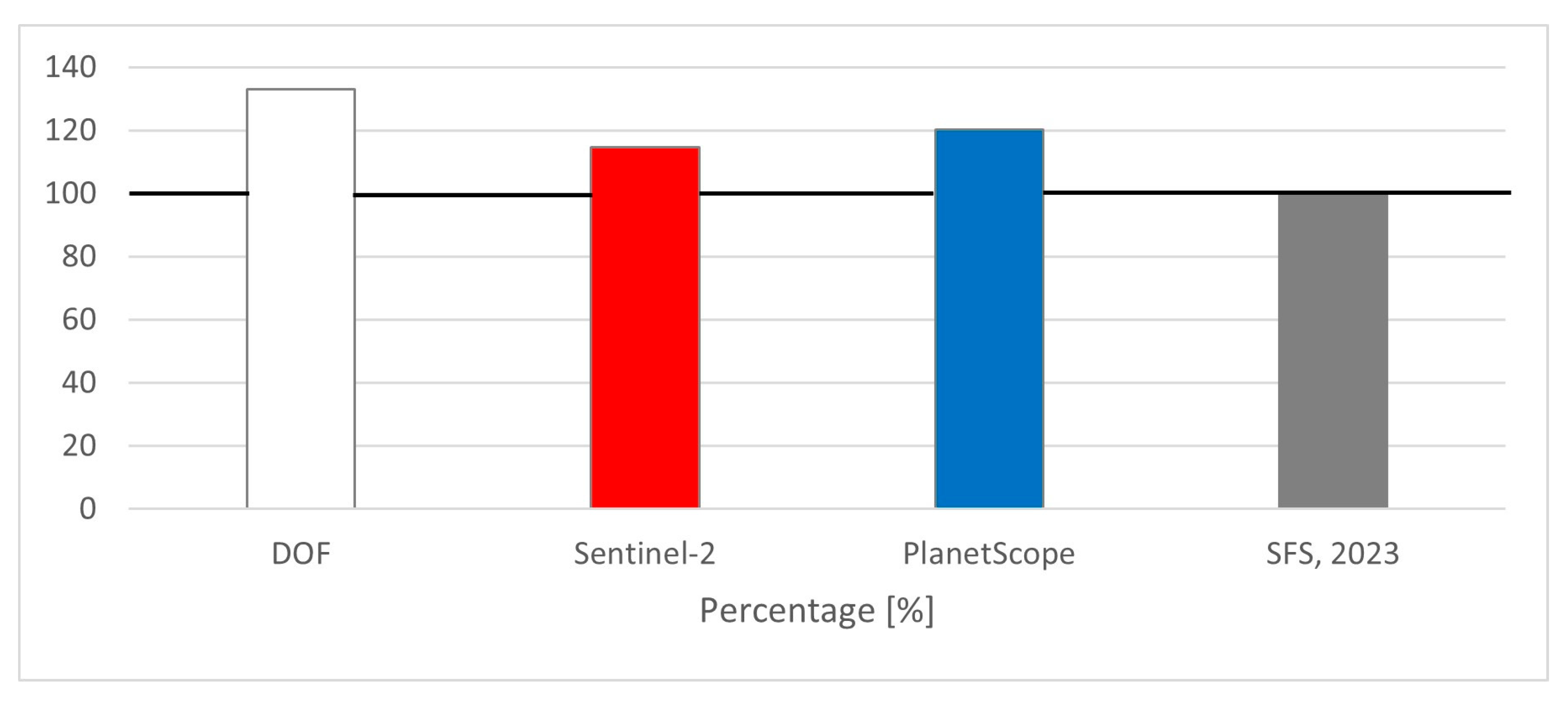

3.4. Validation of Damaged Timber Volume Estimates

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CD | Change Detection |

| DOF | Digital Orthophoto |

| GURS | Surveying and Mapping Authority of the Republic of Slovenia |

| NIR | Near Infrared |

| NDVI | Normalised Difference Vegetation Index |

| PS | PlanetScope |

| S2 | Sentinel-2 |

| SFI | Slovenian Forest Institute |

| SFS | Slovenian Forest Service |

| UAV | unmanned aerial vehicles |

Appendix A. Sentinel-2 Time Series (NDVI, NDRE and NDMI)

Appendix B. Threshold Selection Histograms, Sensitivity and Additional Result Evaluation

Appendix B.1

Appendix B.2. Threshold Sensitivity by Spectral Index (Lead-In)

Appendix B.3. Sensitivity of Mapped Windthrow Area to the Change-Threshold (τ) by Sensor and Index

Appendix B.4

| Data | Index | Threshold | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | Specificity | F1-Score | IoU | Kappa | Diff Area [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PS | NDVI | −0.08 | 0.945 | 0.453 | 0.641 | 0.961 | 0.531 | 0.361 | 0.503 | +41.4 |

| −0.09 | 0.949 | 0.482 | 0.591 | 0.968 | 0.531 | 0.362 | 0.505 | +22.6 | ||

| −0.10 | 0.952 | 0.507 | 0.541 | 0.973 | 0.523 | 0.354 | 0.498 | +6.74 | ||

| −0.11 | 0.954 | 0.526 | 0.492 | 0.977 | 0.508 | 0.341 | 0.484 | −6.6 | ||

| −0.12 | 0.955 | 0.540 | 0.445 | 0.981 | 0.488 | 0.323 | 0.465 | −17.7 | ||

| NDRE | −0.09 | 0.951 | 0.490 | 0.382 | 0.980 | 0.430 | 0.274 | 0.404 | +82.2 | |

| −0.10 | 0.939 | 0.413 | 0.627 | 0.955 | 0.498 | 0.332 | 0.467 | +51.6 | ||

| −0.11 | 0.944 | 0.443 | 0.564 | 0.964 | 0.496 | 0.330 | 0.467 | +27.5 | ||

| −0.12 | 0.948 | 0.465 | 0.501 | 0.971 | 0.482 | 0.318 | 0.455 | +7.71 | ||

| −0.13 | 0.950 | 0.481 | 0.439 | 0.976 | 0.459 | 0.298 | 0.433 | −8.6 | ||

| −0.14 | 0.951 | 0.490 | 0.382 | 0.980 | 0.430 | 0.274 | 0.404 | −22.0 | ||

| S2 | NDVI | −0.09 | 0.971 | 0.700 | 0.696 | 0.985 | 0.698 | 0.536 | 0.683 | −0.56 |

| −0.10 | 0.972 | 0.739 | 0.666 | 0.988 | 0.701 | 0.539 | 0.686 | −9.77 | ||

| −0.11 | 0.973 | 0.770 | 0.637 | 0.990 | 0.697 | 0.535 | 0.683 | −17.33 | ||

| NDRE | −0.10 | 0.967 | 0.660 | 0.659 | 0.983 | 0.660 | 0.492 | 0.642 | −0.15 | |

| −0.11 | 0.969 | 0.699 | 0.627 | 0.986 | 0.661 | 0.494 | 0.645 | −10.21 | ||

| −0.12 | 0.970 | 0.735 | 0.595 | 0.989 | 0.658 | 0.490 | 0.642 | −18.97 | ||

| NDMI | −0.17 | 0.965 | 0.645 | 0.603 | 0.983 | 0.623 | 0.453 | 0.605 | −6.50 | |

| −0.18 | 0.966 | 0.677 | 0.578 | 0.986 | 0.623 | 0.453 | 0.606 | −14.61 | ||

| −0.19 | 0.967 | 0.704 | 0.550 | 0.988 | 0.618 | 0.447 | 0.601 | −21.82 | ||

| −0.20 | 0.967 | 0.729 | 0.524 | 0.990 | 0.610 | 0.438 | 0.593 | −28.21 |

Appendix C. Parcel-Level Damaged-Volume Checks (Within-Sample)

Appendix C.1

Appendix C.2

Appendix C.3

References

- Seidl, R.; Schelhaas, M.-J.; Rammer, W.; Verkerk, P.J. Increasing Forest Disturbances in Europe and Their Impact on Carbon Storage. Nat. Clim. Change 2014, 4, 806–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usbeck, T.; Wohlgemuth, T.; Dobbertin, M.; Pfister, C.; Bürgi, A.; Rebetez, M. Increasing Storm Damage to Forests in Switzerland from 1858 to 2007. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2010, 150, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlásny, T.; Krokene, P.; Liebhold, A.; Montagné-Huck, C.; Müller, J.; Qin, H.; Raffa, K.; Schelhaas, M.-J.; Seidl, R.; Svoboda, M.; et al. Living with Bark Beetles: Impacts, Outlook and Management Options; From Science to Policy; European Forest Institute: Joensuu, Finland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Einzmann, K.; Immitzer, M.; Böck, S.; Bauer, O.; Schmitt, A.; Atzberger, C. Windthrow Detection in European Forests with Very High-Resolution Optical Data. Forests 2017, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonikavičius, D.; Mozgeris, G. Rapid Assessment of Wind Storm-Caused Forest Damage Using Satellite Images and Stand-Wise Forest Inventory Data. Iforest-Biogeosci. For. 2013, 6, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalponte, M.; Marzini, S.; Solano-Correa, Y.T.; Tonon, G.; Vescovo, L.; Gianelle, D. Mapping Forest Windthrows Using High Spatial Resolution Multispectral Satellite Images. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2020, 93, 102206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalponte, M.; Solano-Correa, Y.T.; Marinelli, D.; Liu, S.; Yokoya, N.; Gianelle, D. Detection of Forest Windthrows with Bitemporal COSMO-SkyMed and Sentinel-1 SAR Data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2023, 297, 113787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Xu, Y.J. Comparison of Remote Sensing Change Detection Techniques for Assessing Hurricane Damage to Forests. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2010, 162, 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, R.L.; Frelich, L.; Reich, P.B.; Bauer, M.E. Detecting Wind Disturbance Severity and Canopy Heterogeneity in Boreal Forest by Coupling High-Spatial Resolution Satellite Imagery and Field Data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2010, 114, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, M.; Ozdogan, M.; Wolter, P.T.; Krylov, A.; Vladimirova, N.; Radeloff, V.C. Landsat Remote Sensing of Forest Windfall Disturbance. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 143, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, M.; Steinmeier, C.; Holecz, F.; Stebler, O.; Wagner, H. Detection of Windthrow in Mountainous Regions with Different Remote Sensing Data and Classification Methods. Scand. J. For. Res. 2003, 18, 525–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rüetschi, M.; Small, D.; Waser, L.T. Rapid Detection of Windthrows Using Sentinel-1 C-Band SAR Data. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsah, A.A.; Nazeer, M.; Wong, M.S. LIDAR-Based Forest Biomass Remote Sensing: A Review of Metrics, Methods, and Assessment Criteria for the Selection of Allometric Equations. Forests 2023, 14, 2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirici, G.; Bottalico, F.; Giannetti, F.; Del Perugia, B.; Travaglini, D.; Nocentini, S.; Kutchartt, E.; Marchi, E.; Foderi, C.; Fioravanti, M.; et al. Assessing Forest Windthrow Damage Using Single-Date, Post-Event Airborne Laser Scanning Data. For. Int. J. For. Res. 2018, 91, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokroš, M.; Výbošťok, J.; Merganič, J.; Hollaus, M.; Barton, I.; Koreň, M.; Tomaštík, J.; Čerňava, J. Early Stage Forest Windthrow Estimation Based on Unmanned Aircraft System Imagery. Forests 2017, 8, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogris, N.; Džeroski, S.; Jurc, M. Windthrow Factors—A Case Study on Pokljuka. Zb. Gozdarstva Lesar. 2004, 74, 59–76. [Google Scholar]

- Štofko, P.; Kodrík, M. Comparison of the Root System Architecture between Windthrown and Undamaged Spruces Growing in Poorly Drained Sites. J. For. Sci. 2008, 54, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhe, J. Growth and Development of the Root System of Norway Spruce (Picea Abies) in Forest Stands—A Review. For. Ecol. Manag. 2003, 175, 253–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovenia Forest Service (SFS, ZGS). Neurje Najbolj Prizadelo Gozdove na Gorenjskem; Slovenia Forest Service: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2023. Available online: https://www.zgs.si/informacije/sporocila-za-javnost/neurje-najbolj-prizadelo-gozdove-na-gorenjskem-1214 (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Slovenia Forest Service (SFS, ZGS). Poročilo Zavoda za Gozdove Slovenije o Gozdovih za Leto 2023; Slovenia Forest Service: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2024.

- Copernicus Data Space Ecosystems Copernicus Browser. Available online: https://browser.dataspace.copernicus.eu/ (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Planet Labs Planet Labs: Satellite Imagery & Earth Data Analytics. Available online: https://www.planet.com/ (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- SentiWiki. European Space Agency S2 Mission. Available online: https://sentiwiki.copernicus.eu/web/s2-mission (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Planet Labs Education and Research Program. Available online: https://www.planet.com/industries/education-and-research/ (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Surveying and Mapping Authority of the Republic of Slovenia (SMARS, GURS). Geodetska Uprava Republike Slovenije. Available online: https://www.e-prostor.gov.si/en/access-to-geodetic-data/ (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Slovenia Forest Service (SFS, ZGS). Zavod za gozdove Slovenije. Available online: https://www.zgs.si/en/ (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Çinar, T.; Uslu, A.; Aydin, A. Monitoring the Rehabilitation Process of the Windthrow Area Using UAS Images and Performance Comparison of Sentinel-2A Based Different Vegetation Indexes. Earth Sci. Inform. 2025, 18, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candotti, A.; De Giglio, M.; Dubbini, M.; Tomelleri, E. A Sentinel-2 Based Multi-Temporal Monitoring Framework for Wind and Bark Beetle Detection and Damage Mapping. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 6105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legendre, P. Spatial Autocorrelation: Trouble or New Paradigm? Ecology 1993, 74, 1659–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marriott, P.; Efron, B.; Tibshirani, R.J. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A Stat. Soc. 1995, 158, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaart, A.W.V.D. Asymptotic Statistics, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998; ISBN 978-0-511-80225-6. [Google Scholar]

- Congalton, R.G.; Green, K. Assessing the Accuracy of Remotely Sensed Data: Principles and Practices, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-0-429-14397-7. [Google Scholar]

- Senf, C.; Seidl, R. Natural Disturbances Are Spatially Diverse but Temporally Synchronized across Temperate Forest Landscapes in Europe. Glob. Change Biol. 2018, 24, 1201–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovenian Forestry Institute (SFI, GOZDIS). Sanitarni Posek Dreves. Available online: https://www.zdravgozd.si/sanitarni_index.aspx (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Legat, J. (Slovenian Forest Services, OE Bled, KE Jesenice, Slovenia). Personal communication, 2024.

- Elatawneh, A.; Wallner, A.; Manakos, I.; Schneider, T.; Knoke, T. Forest cover database updates using multi-seasonal RapidEye data—Storm event assessment in the Bavarian forest national park. Forests 2014, 5, 1284–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaglio Laurin, G.; Francini, S.; Luti, T.; Chirici, G.; Pirotti, F.; Papale, D. Satellite Open Data to Monitor Forest Damage Caused by Extreme Climate-Induced Events: A Case Study of the Vaia Storm in Northern Italy. Forestry 2021, 94, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofsson, P.; Foody, G.M.; Herold, M.; Stehman, S.V.; Woodcock, C.E.; Wulder, M.A. Good practices for estimating area and assessing accuracy of land change. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 148, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stehman, S.V.; Foody, G.M. Key issues in rigorous accuracy assessment of land cover products. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 231, 111199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Band | Wavelength (nm) | Spectral Band | Spatial Resolution (m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 443 | Atmospheric Corrections (Aerosols) | 60 |

| 2 | 490 | Blue | 10 |

| 3 | 560 | Green | 10 |

| 4 | 665 | Red | 10 |

| 5 | 705 | Red Edge 1 (Vegetation) | 20 |

| 6 | 740 | Red Edge 2 | 20 |

| 7 | 783 | Red Edge 3 | 20 |

| 8 | 842 | Near-Infrared (NIR) | 10 |

| 8A | 865 | Red Edge 4 (Narrow NIR) | 20 |

| 9 | 940 | Atmospheric Corrections (Water Vapour) | 60 |

| 10 | 1375 | Atmospheric Corrections (Cirrus) | 60 |

| 11 | 1610 | Short-Wave Infrared 1 (SWIR 1) | 20 |

| 12 | 2190 | Short-Wave Infrared 2 (SWIR 2) | 20 |

| Band | Wavelength (nm) | Spectral Band | Spatial Resolution (m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 443 | Coastal Blue | 3 |

| 2 | 490 | Blue | 3 |

| 3 | 531 | Green I | 3 |

| 4 | 565 | Green | 3 |

| 5 | 610 | Yellow | 3 |

| 6 | 665 | Red | 3 |

| 7 | 705 | Red Edge | 3 |

| 8 | 865 | Near Infrared (NIR) | 3 |

| Sentinel-2 | PlanetScope | |

|---|---|---|

| Reference dataset | 252.5 ha | |

| Detected area | 226.2 ha | 226.3 ha |

| Matching with reference dataset | 174.7 ha (77.2%) | 183.1 ha (80.9%) |

| Overestimation | 51.5 ha (22.8%) | 43.2 ha (19.1%) |

| Underestimation | 77.8 ha (30.8%) | 69.4 ha (27.5%) |

| S2-PS match | 174.5 ha | |

| Data Source | Timber Volume (m3) |

|---|---|

| SFS estimation | >60,000 |

| DOF | 80,000 |

| Sentinel-2 | 69,000 |

| PlanetScope | 72,000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zupan, M.; Oštir, K.; Potočnik Buhvald, A. Windthrow Mapping with Sentinel-2 and PlanetScope in Triglav National Park: A Regional Case Study. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3568. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17213568

Zupan M, Oštir K, Potočnik Buhvald A. Windthrow Mapping with Sentinel-2 and PlanetScope in Triglav National Park: A Regional Case Study. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(21):3568. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17213568

Chicago/Turabian StyleZupan, Matej, Krištof Oštir, and Ana Potočnik Buhvald. 2025. "Windthrow Mapping with Sentinel-2 and PlanetScope in Triglav National Park: A Regional Case Study" Remote Sensing 17, no. 21: 3568. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17213568

APA StyleZupan, M., Oštir, K., & Potočnik Buhvald, A. (2025). Windthrow Mapping with Sentinel-2 and PlanetScope in Triglav National Park: A Regional Case Study. Remote Sensing, 17(21), 3568. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17213568