To validate the effectiveness of the proposed DFAS-YOLO, experiments were conducted on two challenging aerial object detection datasets: VisDrone2019 and HIT-UAV. These datasets feature dense small objects, complex scenes, and diverse backgrounds, making them suitable for evaluating detection performance in remote sensing scenarios.

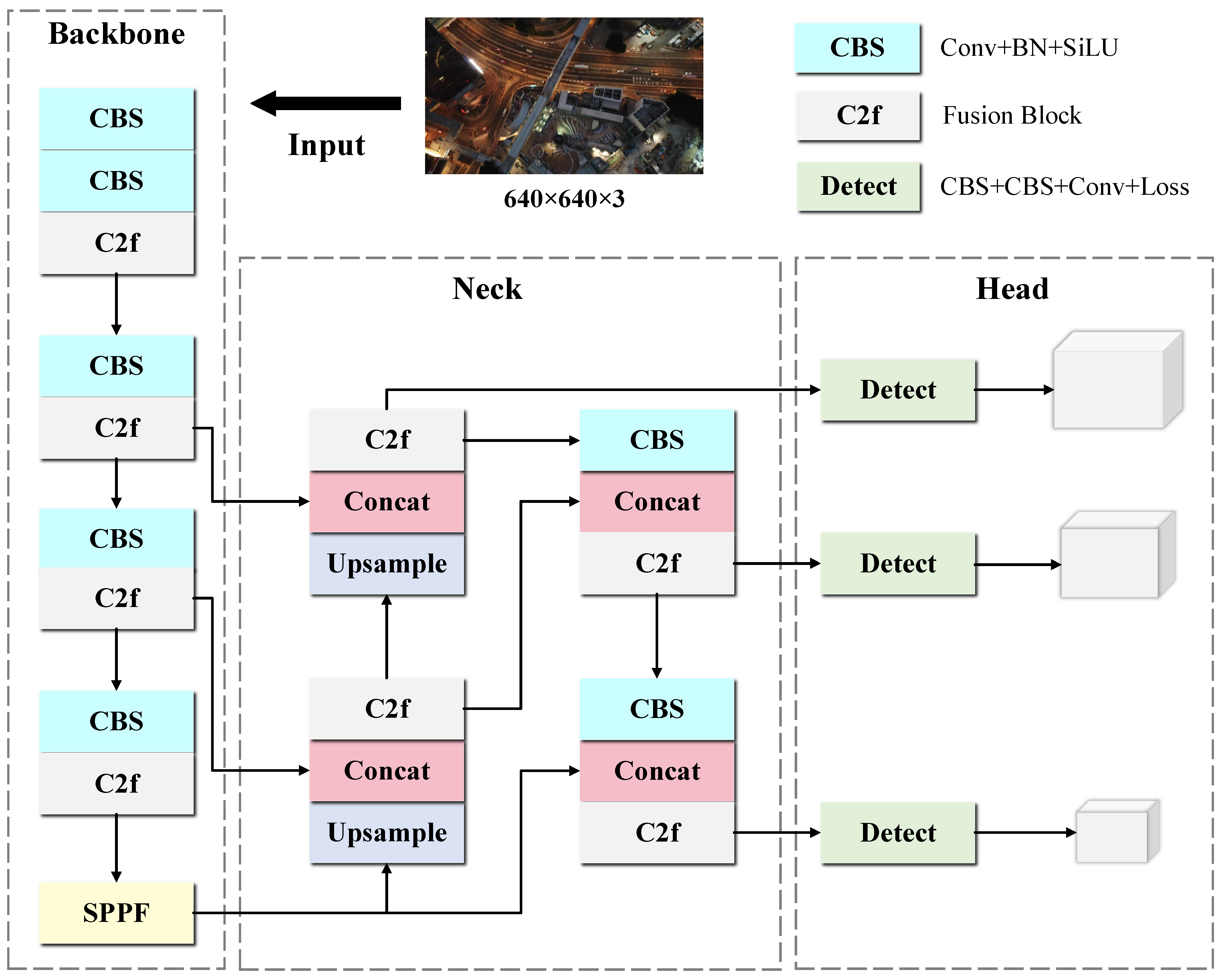

YOLOv8s was adopted as the baseline, balancing accuracy and parameter size for lightweight deployment. All proposed improvements—including the SAAF module, GDLA module, and detection head reconfiguration—were implemented on top of YOLOv8s. Experiments were conducted under consistent training settings to ensure fair comparison with the original model.

4.1. Experimental Dataset Description

- (1)

VisDrone2019: The VisDrone2019 dataset was developed by the AISKYEYE team at Tianjin University. It consists of a large number of video frames and static images captured by UAVs equipped with cameras across various urban and rural regions in China. Each video sequence was collected at different altitudes under diverse weather and lighting conditions. The dataset contains a total of 288 video clips, 261,908 image frames, and 10,209 static images, covering a wide range of object densities and spatial distributions.

Over 2.6 million object instances are manually annotated, including pedestrians, cars, bicycles, and tricycles, with rich attributes such as category, truncation, occlusion, and visibility. Images were collected from different UAV platforms, enhancing the dataset’s diversity. In our experiments, we followed the official split: 6471 images for training, 548 for validation, and 1610 for testing, focusing on UAV-based object detection. The object category distribution is summarized in

Table 1.

- (2)

HIT-UAV: The HIT-UAV dataset, proposed by the Harbin Institute of Technology, is a high-resolution UAV dataset designed for small-object detection. It contains 326 video sequences captured at altitudes of 45–120 m across diverse environments, including highways, urban intersections, playgrounds, parking lots, and residential areas, with both sparse and dense scenes.

The dataset provides over 285,000 annotated object instances across seven categories, such as pedestrians, cars, trucks, buses, motorcycles, and bicycles. Due to high-altitude capture, objects are small and often affected by occlusion, motion blur, and low contrast. Each frame includes class labels, bounding boxes, and visibility states. For our experiments, we followed the split: 2029 training images, 290 validation images, and 579 testing images. The detailed category distribution is listed in

Table 2.

4.2. Model Training and Evaluation Metrics

The proposed model was implemented based on the PyTorch 2.0.0 deep learning framework and trained on a workstation. The detailed hardware and software environment is shown in

Table 3.

The model was trained for 300 epochs using a stochastic gradient descent (SGD) optimizer. The initial learning rate was set to 0.01, with a momentum of 0.937 and weight decay of 0.0005. The batch size was set to 16, and the input image resolution was . Automatic mixed precision (AMP) training was enabled to accelerate convergence and reduce memory usage. Early stopping with a patience of 100 was applied to prevent overfitting. Data loading utilized 8 parallel workers for improved training throughput. During the first 3 epochs, a warm-up strategy was adopted: the momentum linearly increased from 0.8, and the learning rate for bias parameters started from 0.1. The classification loss and Distribution Focal Loss (DFL) weights were set to 0.5 and 1.5, respectively.

In the comparative experiments, all YOLOv5–V11 variants were retrained under the same training settings as described above, while results for other comparison models were directly cited from the corresponding references. The ablation studies were also conducted using identical training parameters.

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the proposed model, precision, recall, average precision (AP), and mean average precision (mAP) were adopted as primary evaluation metrics. The computation of each metric is described as follows:

Precision measures the proportion of correctly predicted positive samples among all predicted positives. It is defined as follows:

where

denotes the number of true positives and

the number of false positives.

Recall evaluates the ability of the model to detect all relevant objects in the ground truth. It is calculated as follows:

where

represents the number of false negatives.

By varying the confidence threshold, multiple

pairs are obtained, forming a precision–recall (P-R) curve. The area under this curve is defined as the average precision:

where

denotes the precision as a function of recall

r. In practice, the integral is approximated using a finite set of recall levels and the corresponding precision values.

The mean average precision at an IoU threshold of 0.50 is computed by averaging the AP over all object classes:

where

N is the number of object categories.

Following the COCO evaluation protocol,

is computed by averaging the AP over ten IoU thresholds ranging from 0.50 to 0.95, with a step size of 0.05:

This metric provides a more rigorous and comprehensive evaluation of the model’s detection performance under various overlap conditions.

4.3. Comparisons with Previous Methods

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed DFAS-YOLO model, a comprehensive comparison was conducted with mainstream detection algorithms on two representative UAV datasets: VisDrone2019 and HIT-UAV. These two datasets reflect different sensing modalities and detection challenges. Various classical and recent detectors were compared, with metrics including precision, recall, mAP50, mAP50:95, and model size (in millions of parameters) evaluated on the validation sets. Visual qualitative comparisons are presented based on results from the testing sets.

- (1)

VisDrone2019:

Table 4 presents the detection results of DFAS-YOLO alongside various classical and recent methods, including YOLOv5, YOLOv8, YOLOv10, and transformer-based approaches.

Compared to existing methods, DFAS-YOLO achieves superior detection performance on the VisDrone2019 dataset. As shown in

Table 4, our method outperforms mainstream one-stage detectors such as YOLOv5, YOLOv8, and YOLOv10, as well as more complex two-stage frameworks like Faster R-CNN and RetinaNet. Specifically, DFAS-YOLO obtains the highest values in both

(0.448) and

(0.273), indicating stronger localization precision and robustness across different IoU thresholds.

Notably, DFAS-YOLO surpasses its baseline YOLOv8s by a considerable margin of +6.4% in and +4.3% in , demonstrating the effectiveness of our design in enhancing small-object detection under crowded and cluttered UAV scenarios. Moreover, the proposed DFAS-YOLO significantly reduces the model size from 11.1M to 7.52M parameters, suggesting that the improvements are not only effective but also lightweight and efficient.

When compared to other lightweight and specialized UAV detection models such as Drone-YOLO and FFCA-YOLO, DFAS-YOLO still maintains a performance advantage. For example, while Edge-YOLO reaches a comparable (0.448), its parameter count (40.5M) is more than five times that of DFAS-YOLO. This reflects the strong balance that our model strikes between accuracy and computational cost, making it better suited for resource-constrained UAV platforms.

Qualitative results in

Figure 7 further support our findings. DFAS-YOLO demonstrates superior detection performance on weak and small targets, effectively addressing missed detections that are commonly observed in the baseline model. It accurately detects small, overlapping, or occluded objects in complex environments, validating the effectiveness of the proposed SAAF and GDLA modules in enhancing multi-scale feature fusion and semantic sensitivity. The visual improvements highlight DFAS-YOLO’s enhanced ability to capture subtle object cues that the baseline often fails to detect.

- (2)

HIT-UAV: As shown in

Table 5, DFAS-YOLO achieves the highest

(0.785) and

(0.541) among all competing methods, outperforming conventional detectors like YOLOv5 and YOLOv8, as well as transformer-based models such as RTDETR. Notably, our model maintains a compact size of only 7.52M parameters, while achieving better performance than significantly larger models like YOLOv5m (25.1M) and RTDETR-L (32.8M).

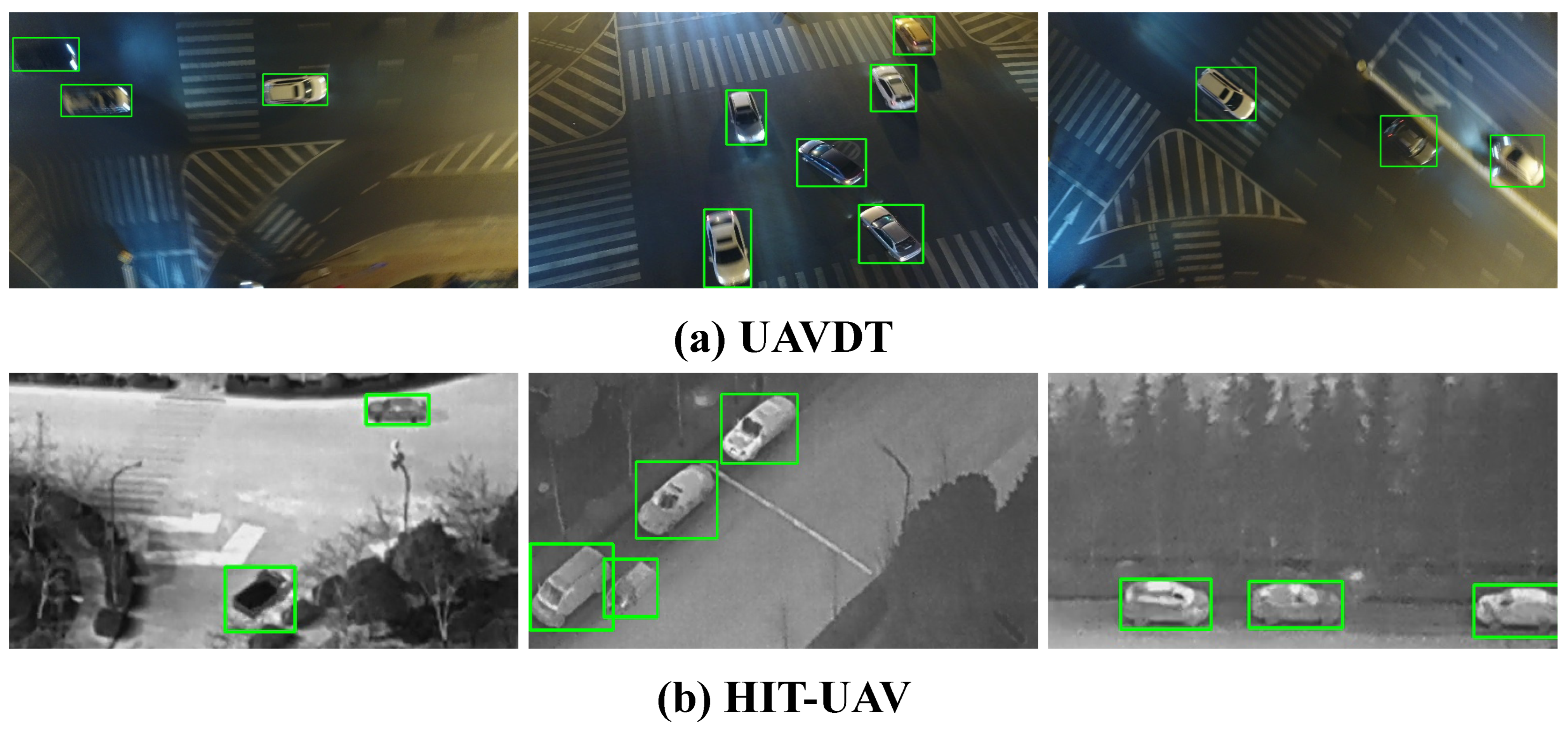

The visual results in

Figure 8, obtained on the testing set, further demonstrate the robustness of DFAS-YOLO in detecting low-contrast targets and preserving fine-grained structures in thermal imagery. Notably, DFAS-YOLO successfully avoids false positives that occur in the baseline YOLOv8, showcasing its superior discrimination ability. These results highlight the effectiveness of our designed modules, particularly under adverse sensing conditions, and validate the enhanced reliability of DFAS-YOLO in challenging environments.

To demonstrate the practical effectiveness of DFAS-YOLO in complex real-world scenarios, qualitative detection results are presented for both the VisDrone2019 and HIT-UAV datasets. As illustrated in

Figure 9, DFAS-YOLO achieves accurate and reliable detection across representative scenes in the VisDrone2019 dataset, including congested urban streets, densely populated basketball courts, and nighttime road environments.

Figure 10 further showcases the model’s robustness in detecting small and low-contrast objects across various infrared scenes from the HIT-UAV dataset, such as forested areas and parking lots. These visualizations underscore the model’s strong generalization capability under diverse sensing conditions.

Qualitative detection results on the VisDrone2019 and HIT-UAV datasets provide an initial assessment of DFAS-YOLO’s detection ability across standard scenes. These results illustrate that the model can accurately detect objects under typical conditions.

To further evaluate transferability, the model trained on the VisDrone dataset was directly tested on the UAVDT and HIT-UAV datasets. The visualizations in

Figure 11 indicate that DFAS-YOLO maintains effective detection performance despite the domain shift, highlighting its cross-dataset generalization capability.

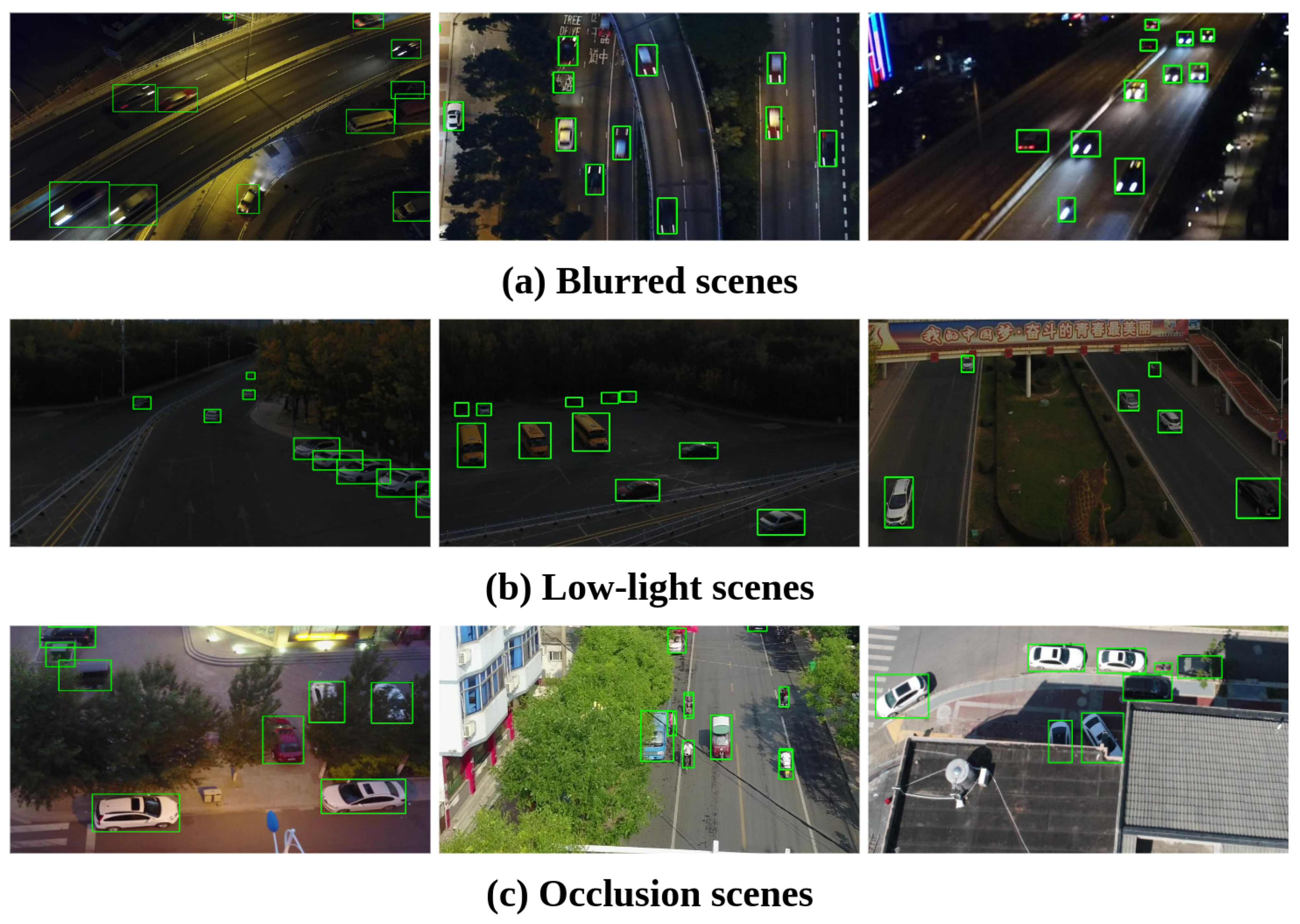

Additionally, robustness was assessed by presenting detection results under challenging imaging conditions, including blur, low light, and occlusion. As shown in

Figure 12, DFAS-YOLO consistently detects objects even when the visual quality is degraded, demonstrating stability under non-ideal conditions.

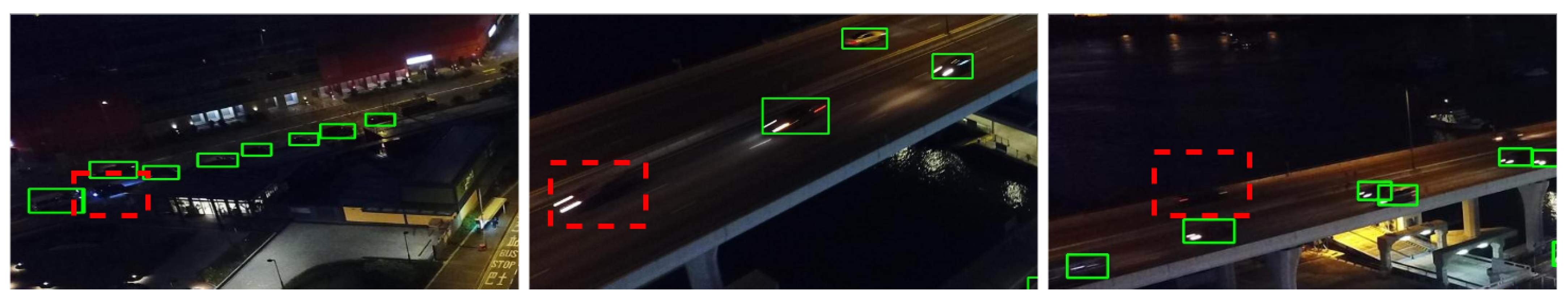

Besides the aforementioned successful detections, failure cases were observed under dark and blurred conditions. As shown in

Figure 13, DFAS-YOLO occasionally misses objects when the scene is both poorly lit and blurred, reflecting the model’s limitations under extreme image degradation. Missed detections usually occur for small objects or regions with low contrast against the background, suggesting that future improvements could involve data augmentation, more robust attention mechanisms, or exploration of multimodal information.

4.4. Ablation Experiments

To evaluate the contribution of each component in DFAS-YOLO, extensive ablation experiments were conducted on the VisDrone2019 validation set. The experiments were categorized into four aspects: overall module effectiveness, upsampling methods, loss functions, and the GDLA window size.

- (1)

Overall Module Effectiveness: As shown in

Table 6, a progressive ablation study was conducted to evaluate the individual and combined contributions of SAAF, GDLA, the P2–P5 adjustment, and WIOU loss. Starting from the YOLOv8s baseline, which achieved 0.384

and 0.230

, each module yielded noticeable gains. Introducing the SAAF module boosts

by 1.7%, thanks to its soft-aware feature fusion that mitigates misalignment during upsampling. The GDLA module provides further enhancement in precision and recall by reinforcing low-level semantics in dim or cluttered regions. Meanwhile, replacing the original detection heads with a finer-scale P2 and removing the coarse-scale P5 further improves performance, highlighting the importance of small-object detection in UAV scenes. Finally, switching from CIOU to WIOU brings consistent gains in both recall and

. When all four components are integrated, DFAS-YOLO reaches 0.448

and 0.273

, clearly surpassing the baseline and demonstrating the effectiveness and complementarity of each proposed module.

FPS results were measured on the VisDrone2019 validation set with single-image inference using an RTX 3090 GPU. Although adding modules inevitably introduces extra computation and slightly reduces speed, the complete model still achieves 132 FPS. This indicates that our method improves detection accuracy while maintaining a favorable inference speed.

- (2)

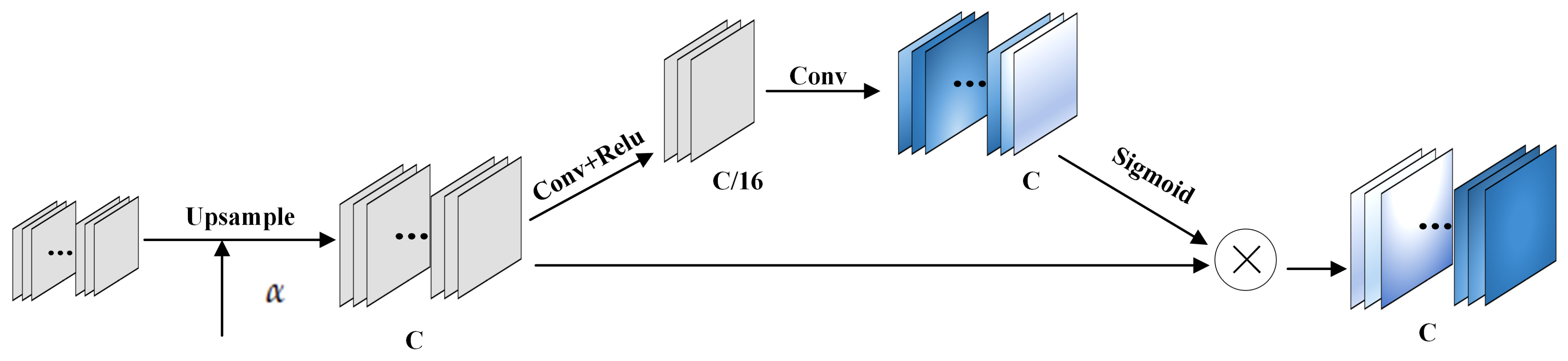

Comparison of Upsampling Methods: To validate the superiority of the proposed SAAF upsampling strategy, it was compared with several commonly used methods, including bilinear, bicubic, and transposed convolution, as summarized in

Table 7. The default upsampling in YOLOv8 yields only 0.384

, while bilinear and bicubic interpolation produce marginal improvements. Transposed convolution offers higher recall and mAP, but at the cost of significantly increased computational overhead (35.4GFLOPs). In contrast, the SAAF module achieves the highest overall performance, with 0.401

and 0.242

, while maintaining moderate computational complexity (29.4 GFLOPs). This confirms that SAAF effectively balances accuracy and efficiency by introducing soft-aware interpolation, which refines feature alignment without excessive computation, making it better suited for resource-constrained UAV detection tasks. Compared with CARAFE and CARAFE++, the SAAF module achieves higher mAP values while keeping computational complexity lower (29.4 GFLOPs vs. 30.3 GFLOPs). This indicates that SAAF provides a more effective balance between detection performance and efficiency.

- (3)

Comparison of Loss Functions:

Table 8 also presents the performance of different IoU-based loss functions used for bounding-box regression. While EIOU yields slightly higher precision (0.512), it suffers from a trade-off in recall and fails to significantly improve the overall localization quality. In contrast, WIOU demonstrates a more balanced performance across all metrics, achieving the highest recall (0.386),

(0.390), and

(0.236). The improved

, which accounts for stricter IoU thresholds, indicates that WIOU provides more precise box alignment, which is especially beneficial for small or overlapping objects in crowded UAV scenarios. Furthermore, its adaptive weighting strategy helps suppress outliers during optimization, enhancing model robustness. Based on these observations, WIOU was selected as the final localization loss function in DFAS-YOLO.

- (4)

Comparison of Downsampling Methods: As shown in

Table 9, we conducted a comprehensive comparison between GDLA and several representative downsampling modules, including GSConvE, ADown, GhostConv, and SCDown, under the same experimental settings. The results demonstrate that GDLA achieves the highest overall performance, yielding the best

(0.398) and

(0.235), as well as the best recall (0.389). Although SCDown slightly outperforms GDLA in terms of precision, GDLA provides a more balanced improvement across all metrics, confirming its superiority in enhancing detection accuracy. The computational complexity of GDLA (29.3 GFLOPs) is marginally higher than that of the other methods, but the performance gain justifies this trade-off, validating the effectiveness of the proposed design.

- (5)

GDLA Window Size Study: As shown in

Table 10, the impact of different local window sizes in the GDLA module was investigated to explore how regional context aggregation affects performance. Among the tested configurations, a

window yielded the best balance between recall and accuracy, achieving the highest

(0.398) and

(0.235). This suggests that an intermediate window size provides sufficient spatial context to enhance weak semantic responses without diluting local detail. This proves particularly effective for improving detection in infrared and low-contrast scenes, where small objects often suffer from blurred or ambiguous features. Therefore, the

setting was adopted in our final design.

- (6)

Comparison of Attention in GDLA: As shown in

Table 11, we compared different attention mechanisms applied within the GDLA module. While SE and CBAM slightly improve precision or recall, EMA achieves the best overall performance, yielding 0.398

and 0.235

. This indicates that EMA more effectively integrates global, local, and dense features, enabling better feature selection across the concatenated branches. Therefore, EMA is adopted as the attention mechanism in GDLA to enhance discriminative feature representation while maintaining efficiency.

- (7)

Performance of SAAF and GDLA on Larger Backbones:

Table 12 demonstrates that the proposed SAAF and GDLA modules maintain consistent performance improvements when integrated into larger backbones (YOLOv8m/l). Both modules enhance recall and detection accuracy, confirming their scalability and effectiveness across different network capacities. The stable improvements across different model sizes indicate that the proposed designs are robust and are not limited to lightweight architectures.

- (8)

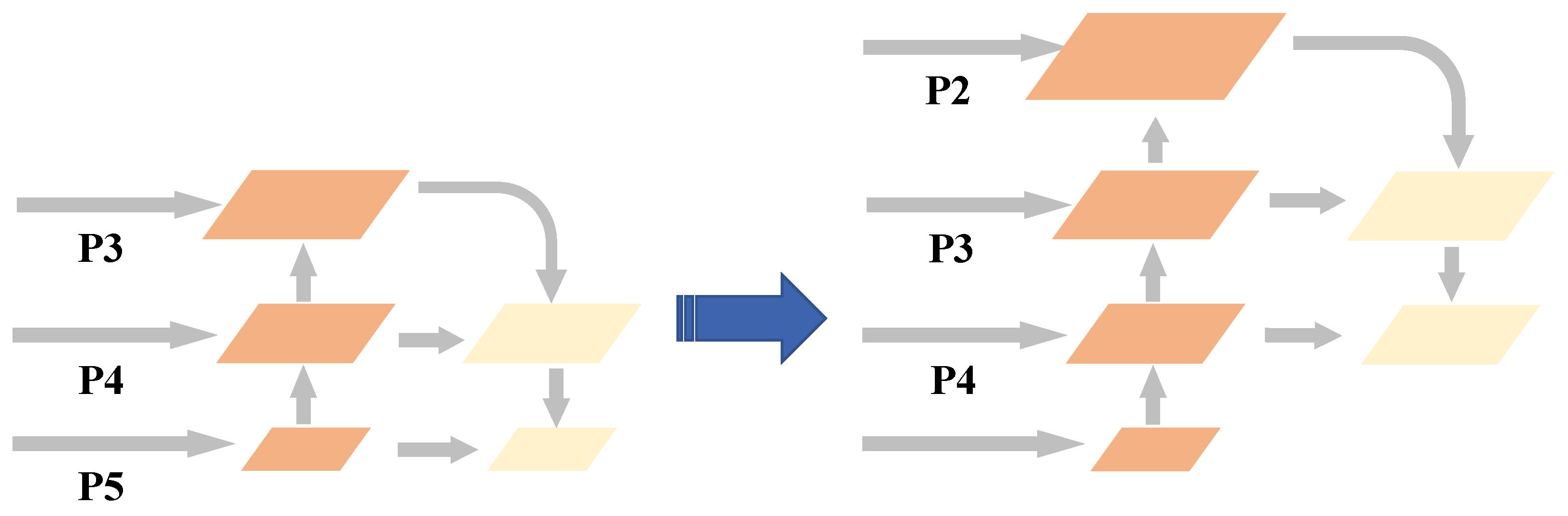

Performance of Detection Head on Small, Medium, and Large Objects: To investigate the impact of modifying the detection heads, we removed the original large-object P5 detection head in YOLOv8 and added a new small-object P2 detection head. The target scales are defined as follows: small objects with an area of 0 to pixels, medium objects with an area of to pixels, and large objects with an area greater than pixels.

As shown in

Table 13, after adding the P2 detection head, small-object AP increased from 0.114 to 0.158, medium-object AP increased from 0.313 to 0.343, and large-object AP slightly increased from 0.394 to 0.407. This improvement can be attributed to the P2 detection head leveraging low-level high-resolution features to capture fine-grained information. Through multi-scale feature fusion, these enhanced features are propagated to mid- and high-level layers, strengthening the representation of large objects. As a result, the adjusted detection head structure not only significantly improves the small-object detection performance but also provides a slight gain for medium and large objects, achieving balanced performance across multiple scales.

Overall, the ablation results validate the effectiveness and necessity of each design component in DFAS-YOLO, and their synergy contributes significantly to performance gains on challenging UAV datasets.