Flood Susceptibility Mapping Using Machine Learning and Geospatial-Sentinel-1 SAR Integration for Enhanced Early Warning Systems

Abstract

Highlights

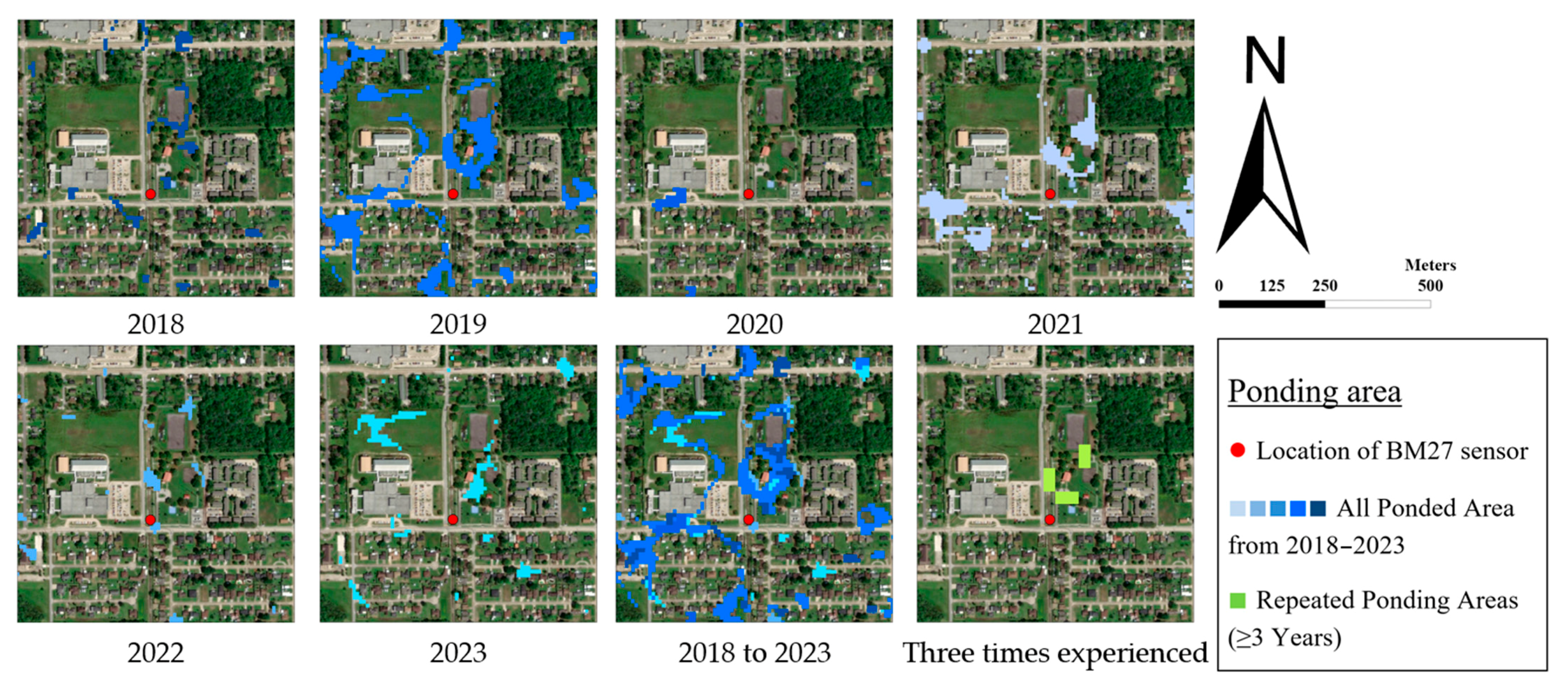

- A multi-year flood inventory was generated from Sentinel-1 SAR imagery (2018–2023) using Google Earth Engine, capturing repeated ponding occurrences as inputs for the target of susceptibility modeling.

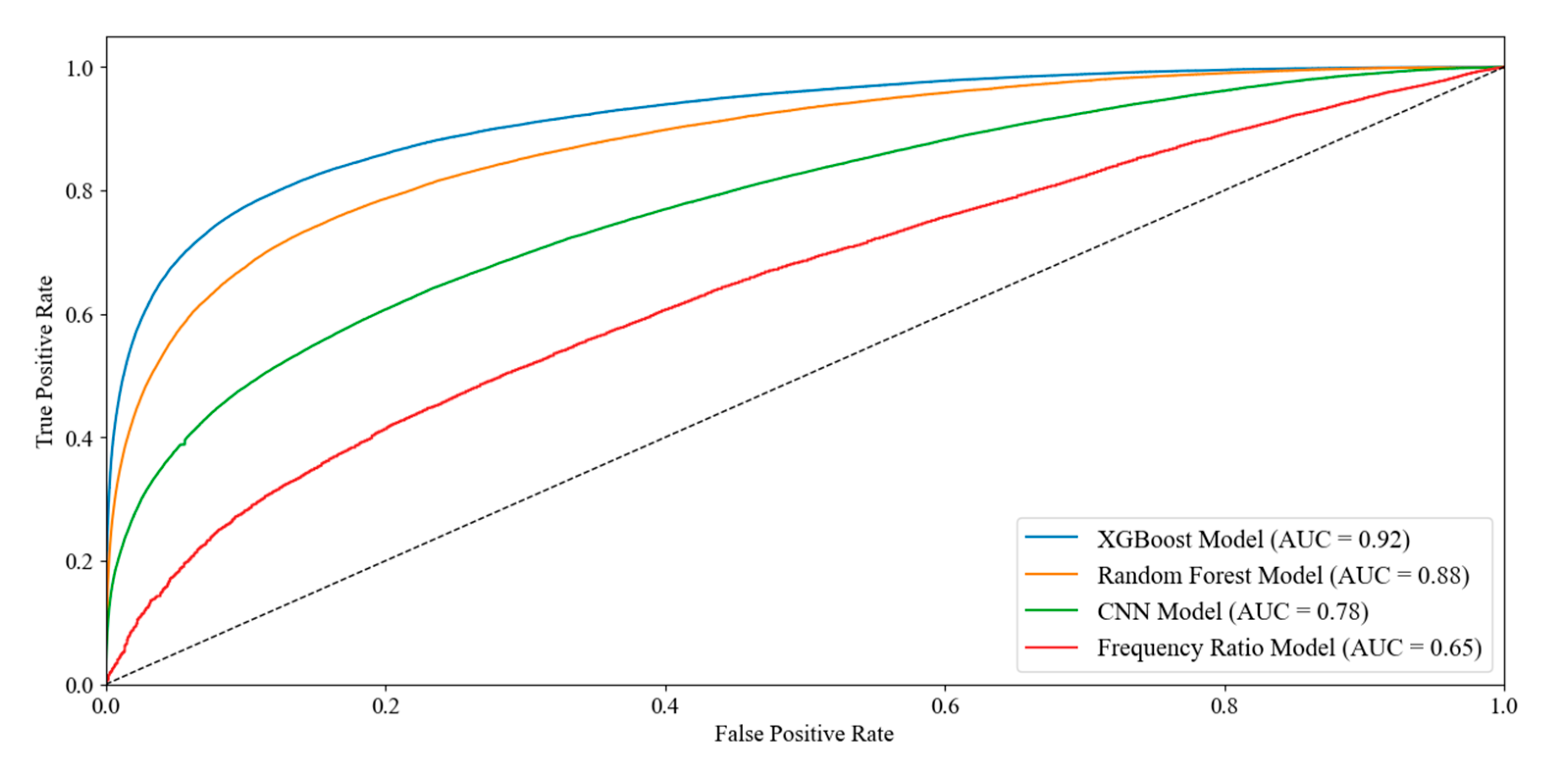

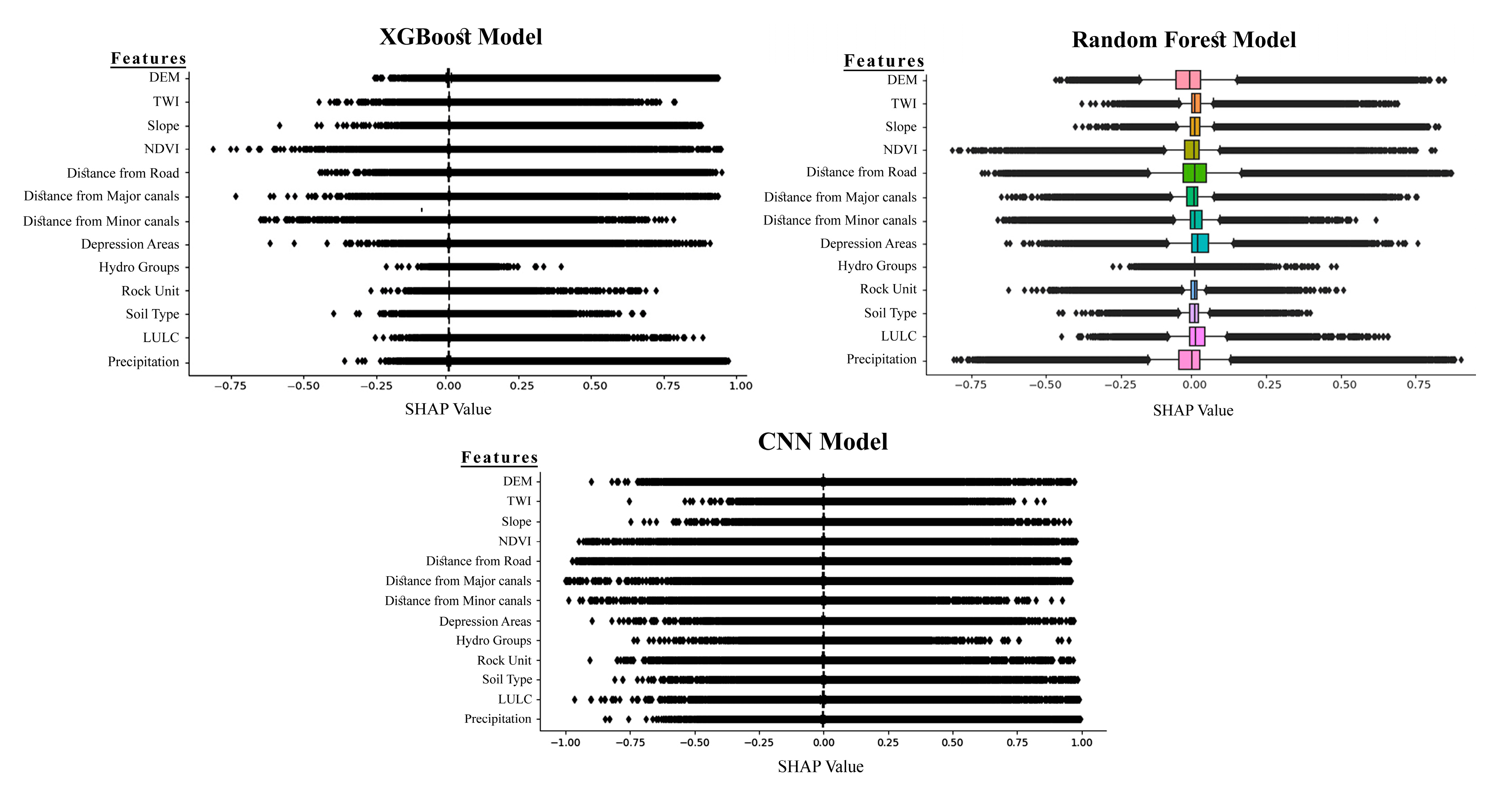

- Flood susceptibility maps were developed using both a statistical model (FR) and machine learning models (RF, XGBoost, CNN), with model performance assessed through AUC and feature interpretability evaluated with SHAP and validated with available high-risk locations monitored by early warning flood sensors.

- The integration of SAR-based flood inventory with geospatial factors provides a robust framework for identifying high-frequency flood-prone areas in Jefferson County, TX, serving as a representative example for data-scarce regions.

- The methodology supports data-driven flood risk management by offering accurate, interpretable, and transferable tools that can inform planning and adaptation strategies in other flood-prone regions.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Identifying which area in Jefferson County has high-frequency ponding hot spots using Sentinel-1 Radar Imagery.

- Using the Sentinel-1 Radar Imagery as a target for Machine learning and statistical models to create a high-frequency ponding susceptibility.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Study Area

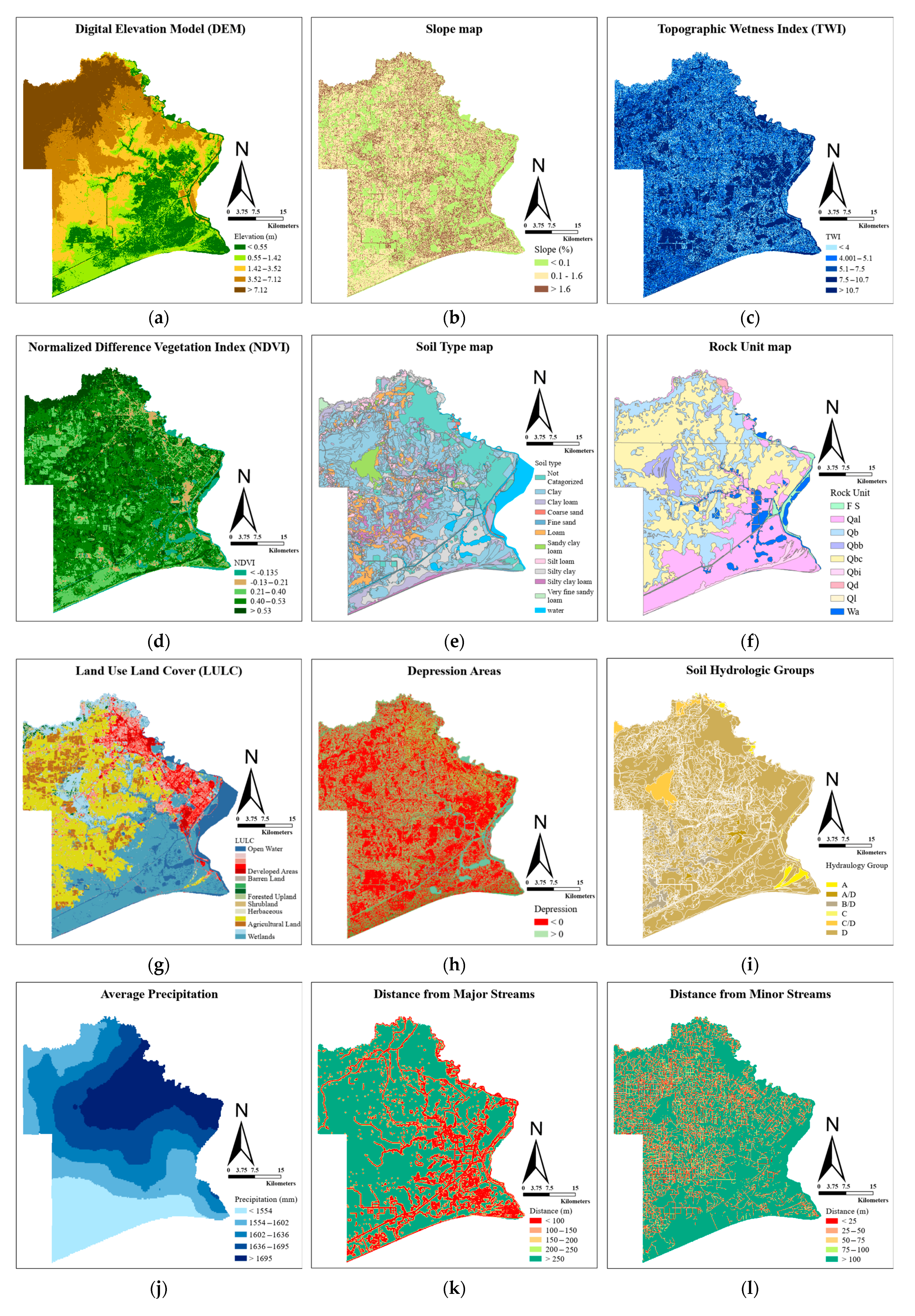

2.2. Flood Susceptibility Factors and Data Preparation

2.2.1. Digital Elevation Model

2.2.2. Slope

2.2.3. Topographic Wetness Index (TWI)

2.2.4. Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI)

2.2.5. Soil Type

2.2.6. Rock Unit

2.2.7. Land Use Land Cover

2.2.8. Depression Areas

2.2.9. Soil Hydrology Group

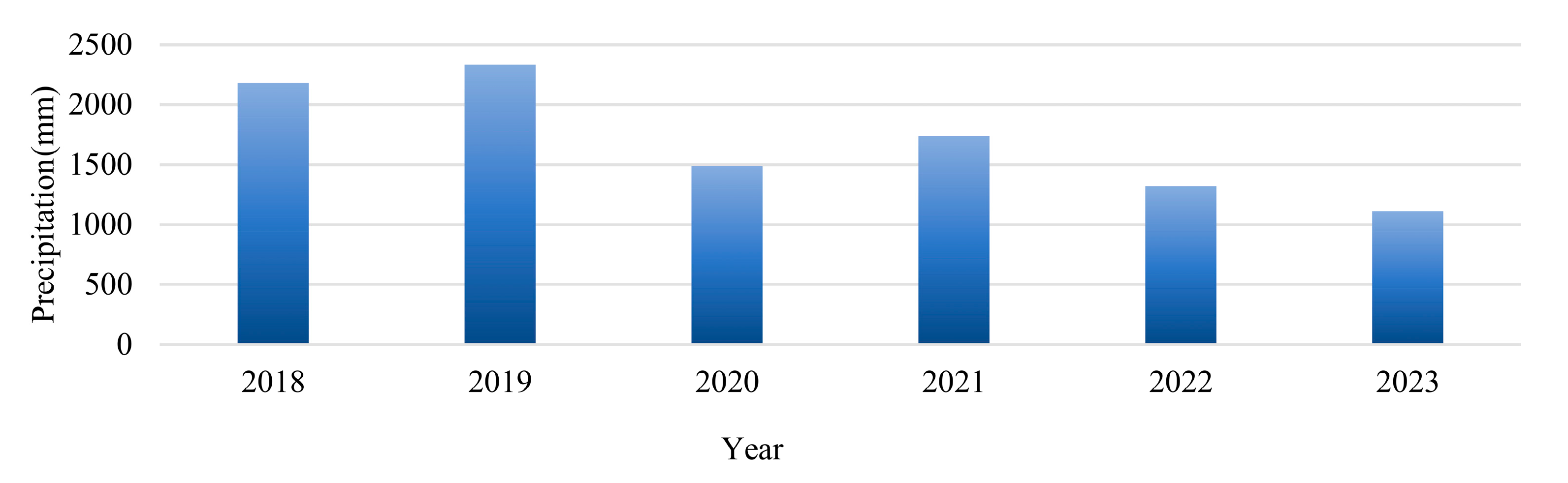

2.2.10. Average Precipitation

2.2.11. Distance for Streams and Waterbodies

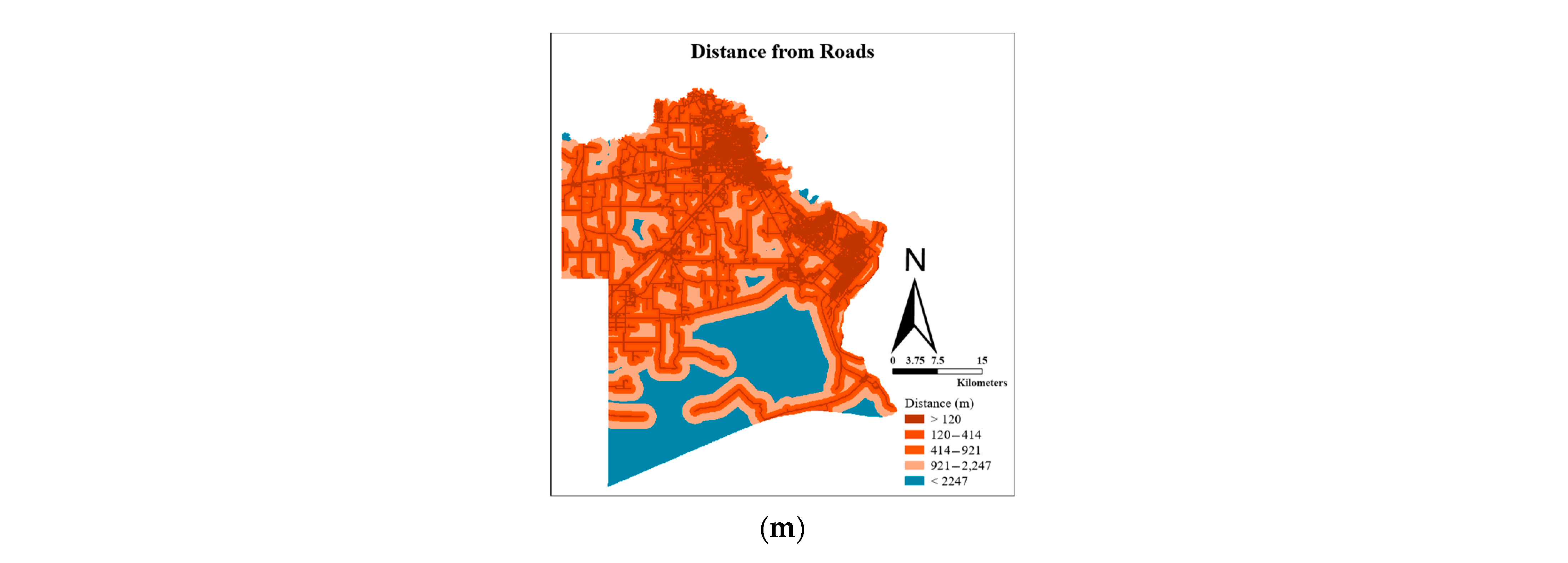

2.2.12. Distance from Road

2.2.13. Sentinel 1 SAR Image

| Algorithm 1. Flood Inventory Mapping Using Sentinel-1 SAR Imagery. |

| Input: Sentinel-1 SAR imagery (2018–2019), PRISM rainfall data Output: Water pixels map |

|

2.3. Methodology

- Statistical Model (Frequency Ratio, FR): The FR method was applied to calculate the relative likelihood of flooding for each class of conditioning factors, providing a baseline statistical assessment of susceptibility.

- Machine Learning Models: three machine learning models, Random Forest, XGBoost, and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), were employed to generate flood susceptibility maps. Random Forest and XGBoost were selected as tree-based algorithms, which are widely recognized as effective models for tabular datasets. Random Forest used as a robust ensemble method with relatively simple structure and interpretability, whereas XGBoost, as an advanced boosting algorithm, was included to capture complex nonlinear relationships and interactions feature space. The CNN model was also introduced as a deep learning architecture capable of learning local feature dependencies and nonlinear patterns across the geospatial predictors.

2.3.1. Model Development

Statistical Model

Machine Learning

- i.

- Model Preprocessing

- ii.

- Models

- is the predicted output after boosting rounds.

- is the newly added decision tree.

- represents the loss function (e.g., log-loss for binary classification).

- is the regularization term, which helps prevent overfitting and is defined as

- is the number of leaves in the tree.

- and are regularization hyperparameters.

- represents leaf weights.

2.3.2. Model Evaluation

- ROC Curve (AUC) metric

- ▪

- TP (True Positive) = number of ponding-prone areas correctly predicted as flood-prone

- ▪

- FN (False Negative) = number of ponding-prone areas incorrectly predicted as non-flood-prone

- ▪

- FP (False Positive) = number of non-ponding-prone areas incorrectly predicted as flood-prone

- ▪

- TN (True Negative) = number of non-ponding-prone areas correctly predicted as non-flood-prone

- ii.

- SHAP Value Interpretability

- iii.

- Validation by High-Risk Locations

- iv.

- Comparison with BLE Maps

3. Results and Discussion

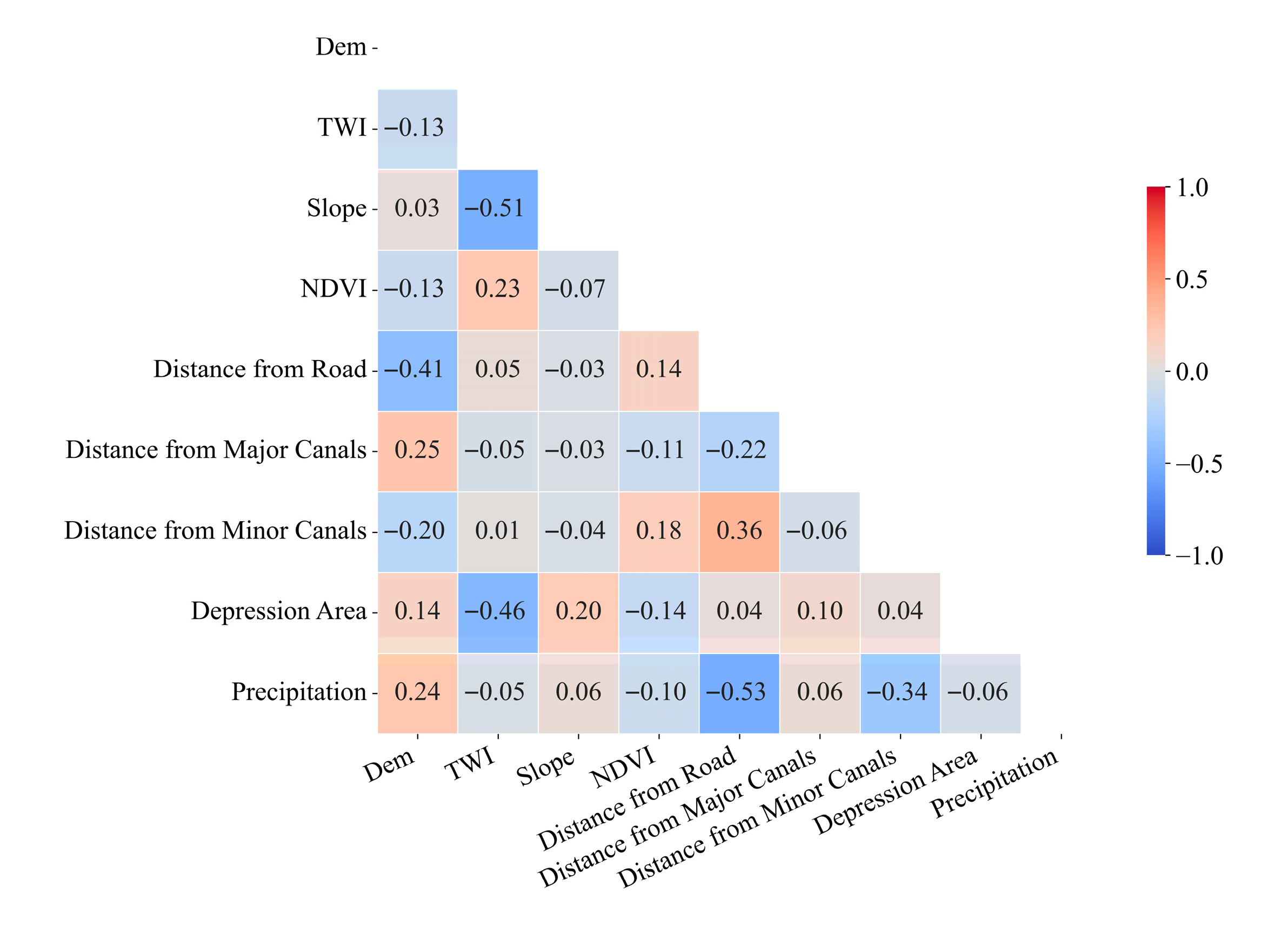

3.1. Correlation Analysis

3.2. Statistical Model Results

3.3. Machine Learning Model

3.3.1. Hyperparameter Tuning

3.3.2. AUC Score

3.3.3. SHAP Score

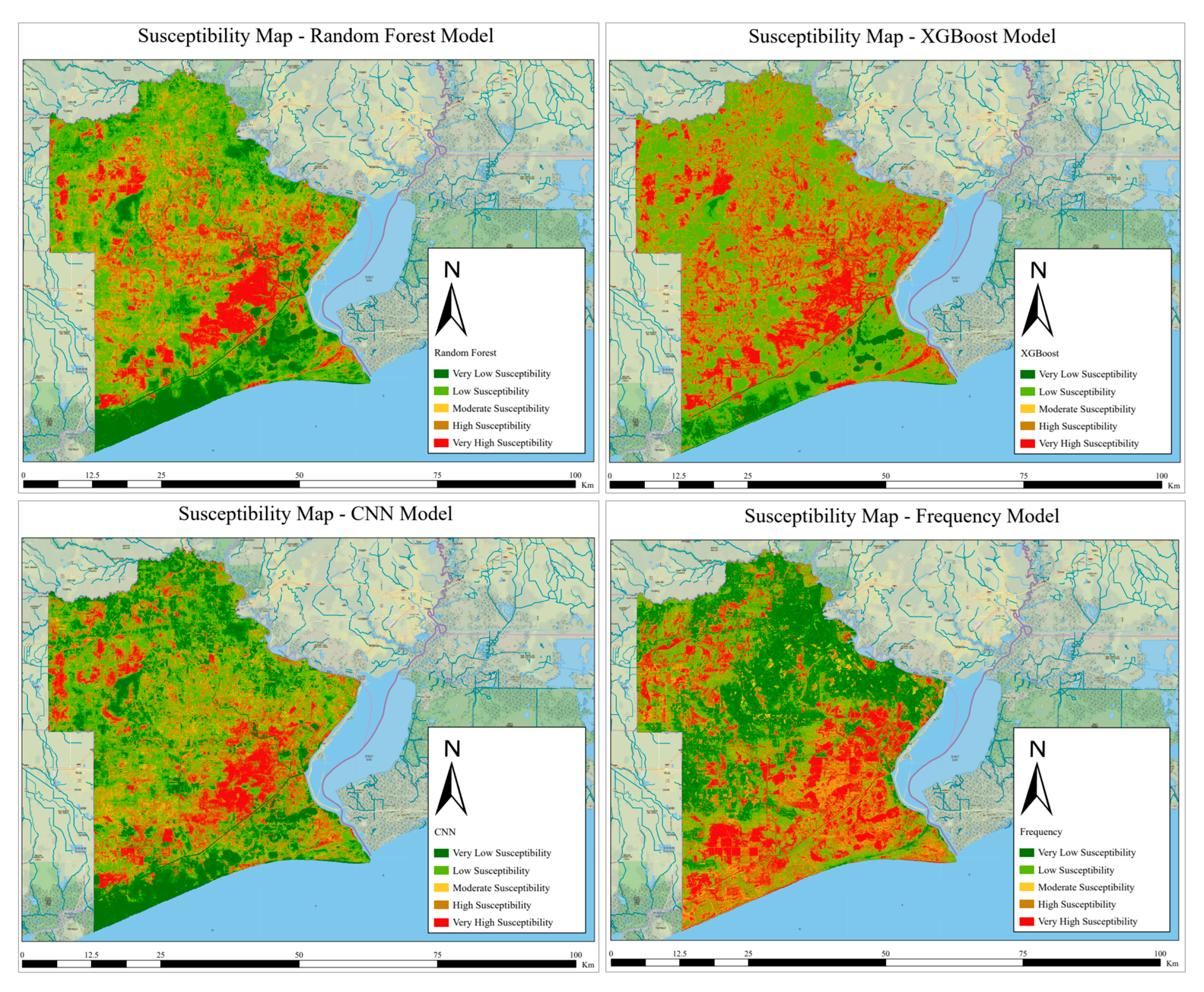

3.4. Flood Susceptibility Maps

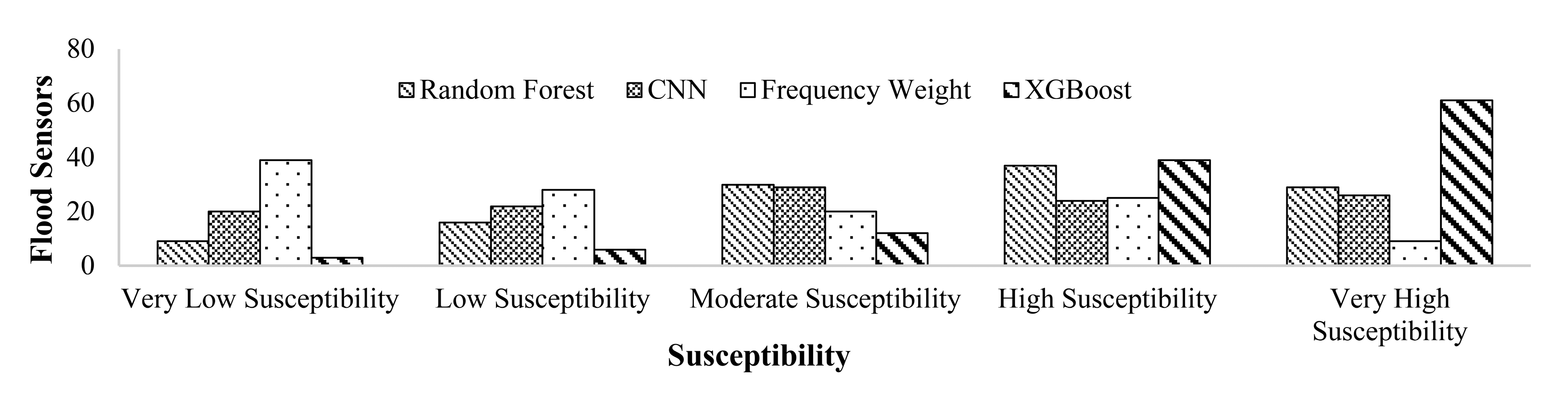

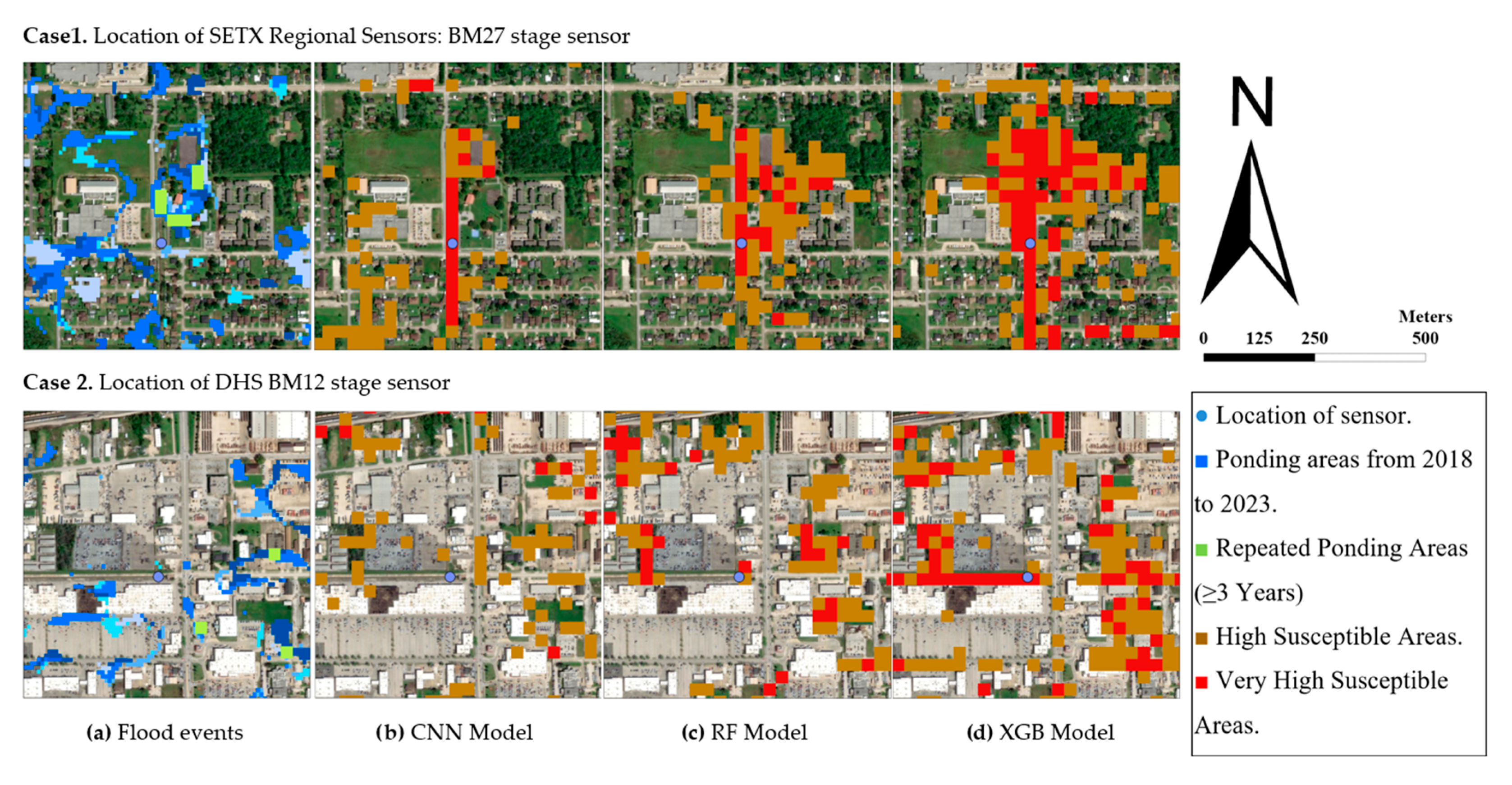

3.5. High Flood-Risk Locations Monitored by Flood Sensors

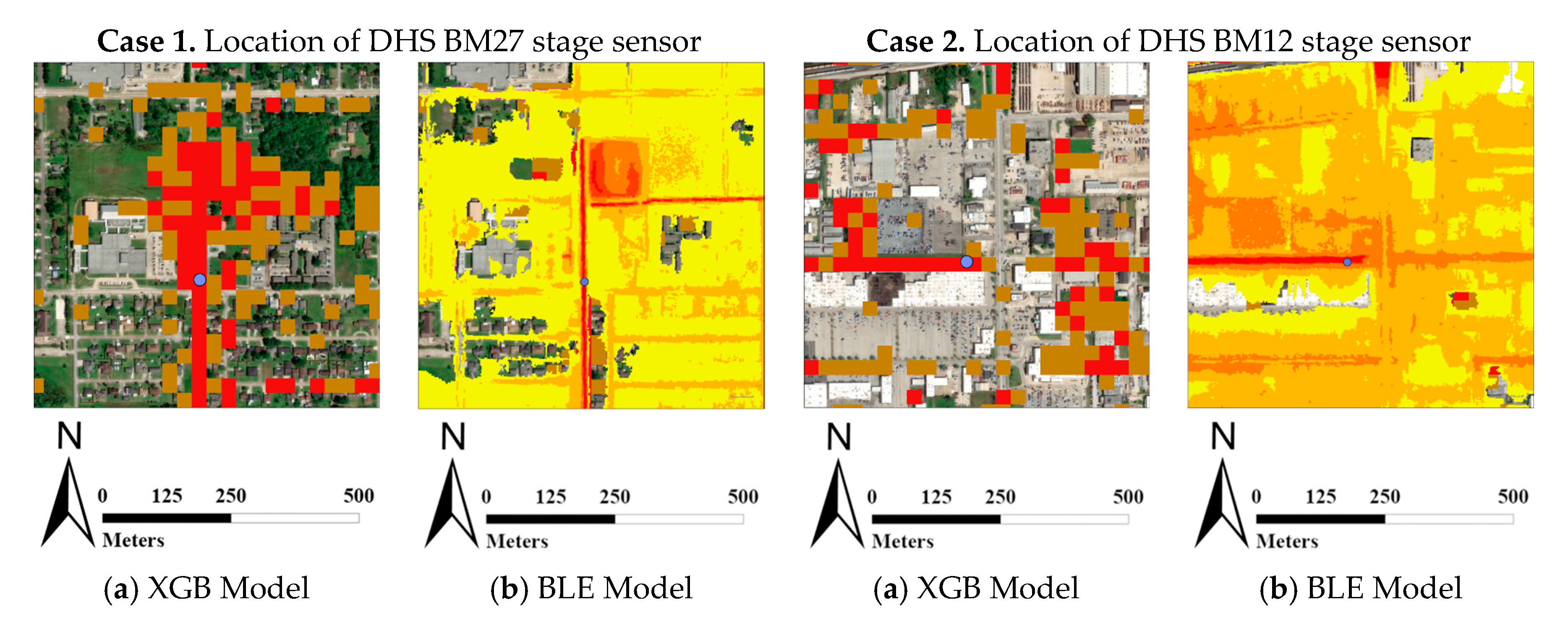

3.6. Comparison with the BLE Map

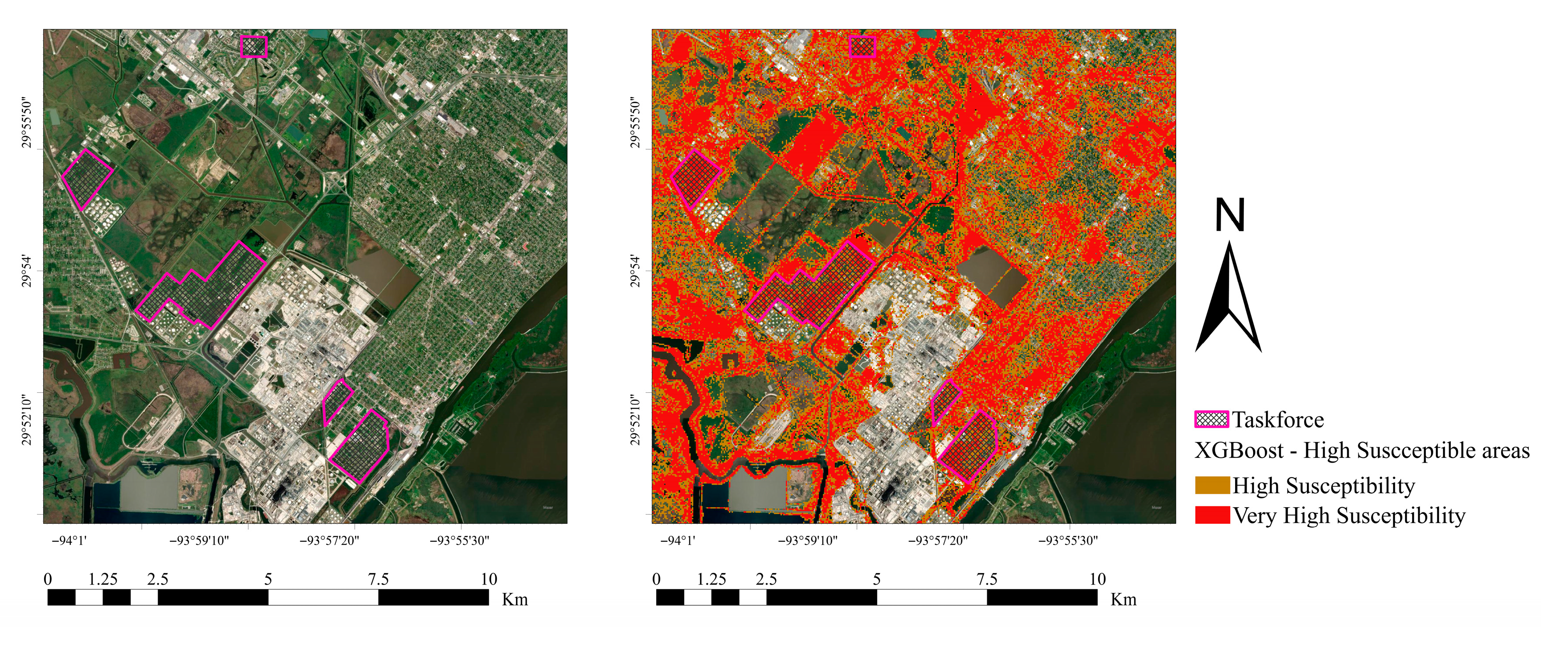

3.7. High-Risk Areas Identified by the Local Community Taskforce

4. Conclusions

- The alignment of the XGBoost model with the BLE risk map and the community task force assessments indicates strong qualitative agreement and model reliability.

- The XGBoost model achieved the best performance (AUC = 0.92), correctly classifying 100 of 121 sensor-identified high-risk locations, outperforming all other methods. Random Forest showed good accuracy (AUC = 0.88) but underestimated severity, while CNN (AUC = 0.78) misclassified many high-risk areas. The Frequency Ratio model had the weakest predictive power (AUC = 0.65), confirming XGBoost as the most reliable approach for flood susceptibility mapping in Jefferson County.

- SHAP value analysis further validated the XGBoost model interpretability, revealing that elevation, slope, TWI, and NDVI were consistently the most influential features. This helps researchers, engineers, and policymakers by highlighting the key environmental factors that drive flood susceptibility.

- Policymakers can use flood susceptibility maps to identify high-risk hotspots and develop optimized early warning systems. By integrating these maps with real-time rainfall and sensor data, flood-prone areas can be predicted more accurately. This supports timely alerts, efficient resource allocation, and improved evacuation planning, ultimately enhancing community preparedness and reducing losses.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sharif, H.O.; Yates, D.; Roberts, R.; Mueller, C. The use of an automated nowcasting system to forecast flash floods in an urban watershed. J. Hydrometeorol. 2006, 7, 190–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, K.N.; First, J.M.; Strader, S.M.; Grondin, N.S.; Burow, D.; Medley, Z. The climatology, vulnerability, and public perceptions associated with overlapping tornado and flash flood warnings in a portion of the southeast United States. Weather Clim. Soc. 2023, 15, 943–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- First, J.M.; Ellis, K.; Strader, S. Double trouble: Examining public protective decision-making during concurrent tornado and flash flood threats in the US Southeast. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 81, 103297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, V.; Braswell, A.E.; Rossi, M.W.; Joseph, M.B.; McShane, C.; Cattau, M.; Koontz, M.J.; McGlinchy, J.; Nagy, R.C.; Balch, J. Risky development: Increasing exposure to natural hazards in the United States. Earth’s Future 2021, 9, e2020EF001795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Summers, J.; Lamper, A.; McMillion, C.; Harwell, L. Observed changes in the frequency, intensity, and spatial patterns of nine natural hazards in the United States from 2000 to 2019. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. A Multi-Attribute Method for Ranking the Risks from Multiple Hazards in a Small Community; Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- (NWS), N.W.S. Flood Fatalities. Hydrologic Information Center. 2014. Available online: http://nws.noaa.gov/oh/hic/flood_stats/recent_individual_deaths.shtml (accessed on 10 March 2014).

- Service, N.W. Summary of Natural Hazard Statistics for 2013 in the United States; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, US Department of Commerce: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- FEMA. Texas Historical Flood Information. 2025. Available online: https://www.cityofcorinth.com/engineering/page/fema-texas-historical-flood-information (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- NOAA. Tropical Cyclone Point Maxima. 2025. Available online: https://www.wpc.ncep.noaa.gov/tropical/rain/tcmaxima.html (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Han, Z.; Sharif, H.O. Analysis of flood fatalities in the United States, 1959–2019. Water 2021, 13, 1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vipulanandan, C.; Parameswaran, S. Hurricane Harvey survey assessment and lessons learned. In Proceedings of the Texas Hurricane Center for Innovative Technology Conference and Exhibition, Houston, TX, USA, 3 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Center, N. National Hurricane Center; Honolulu Forecast Office: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Blake, E.; Zelinsky, D. National Hurricane Center Tropical Cyclone Report Hurricane Harvey (AL092017) 17 August–1 September 2017; NOAA National Hurricane Center: Miami, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Asli, H.H.; Brake, N.; Kruger, J.; Haselbach, L.; Adesina, M. Field surveying data of low-cost networked flood sensors in southeast Texas. Data Brief 2023, 50, 109504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haselbach, L.; Thies, C.; Evans, H.; Apple, C.; Tindall, N. Findings from Two Flood Disaster Response Exercises for Southeast Texas. In Leveraging Sustainable Infrastructure for Resilient Communities; ASCE: Reston, VA, USA, 2022; pp. 22–33. [Google Scholar]

- Vilasan, R.T.; Kapse, V.S. Evaluation of the prediction capability of AHP and F-AHP methods in flood susceptibility mapping of Ernakulam district (India). Nat. Hazards 2022, 112, 1767–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, R.M.A.; He, J. Flood Susceptibility Mapping in Punjab, Pakistan: A Hybrid Approach Integrating Remote Sensing and Analytical Hierarchy Process. Atmosphere 2024, 16, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatah, K.K.; Mustafa, Y.T. Flood susceptibility mapping using an analytic hierarchy process model based on remote sensing and GIS approaches in Akre District, Kurdistan Region, Iraq. Iraqi Geol. J. 2022, 55, 121–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, O.S. Flood hazard susceptibility areas mapping using Analytical Hierarchical Process (AHP), Frequency Ratio (FR) and AHP-FR ensemble based on Geographic Information Systems (GIS): A case study for Kastamonu, Türkiye. Acta Geophys. 2022, 70, 2747–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munyi, J.-m.M. The Influence of Urban Morphology on Flood Susceptibility in Slums in a Data Scarce Environment Using Machine Learning. Master’s Thesis, University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, A. Artificial neural networks for flood susceptibility analysis in Gangarampur sub-division of Dakshin Dinajpur, West Bengal, India. Front. Eng. Built Environ. 2025, 5, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, M.; Abedi Koupai, J.; Gohari, S.A. Integration of SWAT, SDSM, AHP, and TOPSIS to detect flood-prone areas. Nat. Hazards 2024, 120, 6307–6325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasnaoui, Y.; Tachi, S.E.; Bouguerra, H.; Yaseen, Z.M. Transfer learning-based deep learning models for flood and erosion detection in coastal area of Algeria. Earth Sci. Inform. 2025, 18, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotou, C.F.; Feloni, E.; Aristidou, K.; Eliades, M. Probabilistic assessment of flood susceptibility via a coparticipative multicriteria decision analysis. Environ. Process. 2025, 12, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotou, C.F. Copula-based assessment of flood susceptibility in the island of Cyprus via stochastic multicriteria decision analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 979, 179469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Msabi, M.M.; Makonyo, M. Flood susceptibility mapping using GIS and multi-criteria decision analysis: A case of Dodoma region, central Tanzania. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2021, 21, 100445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodangeh, E.; Choubin, B.; Eigdir, A.N.; Nabipour, N.; Panahi, M.; Shamshirband, S.; Mosavi, A. Integrated machine learning methods with resampling algorithms for flood susceptibility prediction. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 705, 135983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharakhanlou, N.M.; Perez, L. Flood susceptible prediction through the use of geospatial variables and machine learning methods. J. Hydrol. 2023, 617, 129121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumne, W.; Samanta, S. Geospatial Mapping of Inland Flood Susceptibility Based on Multi-Criteria Analysis–A Case Study in the Final Flow of Busu River Basin, Papua New Guinea. Int. J. Geoinform. 2023, 19, 31–48. [Google Scholar]

- Rezaei, M.; Amiraslani, F.; Samani, N.N.; Alavipanah, K. Application of two fuzzy models using knowledge-based and linear aggregation approaches to identifying flooding-prone areas in Tehran. Nat. Hazards 2020, 100, 363–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaddari, A.; Jari, A.; Chakiri, S.; El Hadi, H.; Labriki, A.; Hajaj, S.; El Harti, A.; Goumghar, L.; Abioui, M. A comparative analysis of analytical hierarchy process and fuzzy logic modeling in flood susceptibility mapping in the Assaka Watershed, Morocco. J. Ecol. Eng. 2023, 24, 62–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wubalem, A.; Tesfaw, G.; Dawit, Z.; Getahun, B.; Mekuria, T.; Jothimani, M. Comparison of statistical and analytical hierarchy process methods on flood susceptibility mapping: In a case study of the Lake Tana sub-basin in northwestern Ethiopia. Open Geosci. 2021, 13, 1668–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seydi, S.T.; Kanani-Sadat, Y.; Hasanlou, M.; Sahraei, R.; Chanussot, J.; Amani, M. Comparison of machine learning algorithms for flood susceptibility mapping. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Huang, G.; Chen, W. Towards better flood risk management: Assessing flood risk and investigating the potential mechanism based on machine learning models. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 293, 112810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sado-Inamura, Y.; Fukushi, K. Empirical analysis of flood risk perception using historical data in Tokyo. Land Use Policy 2019, 82, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Ma, C.; Lian, J.; Xu, K.; Chaima, E. Urban flooding risk assessment based on an integrated k-means cluster algorithm and improved entropy weight method in the region of Haikou, China. J. Hydrol. 2018, 563, 975–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Das, A. Wetland conversion risk assessment of East Kolkata Wetland: A Ramsar site using random forest and support vector machine model. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 123475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, Z.; Lai, C.; Lin, G. Quantitative assessment of the relative impacts of climate change and human activity on flood susceptibility based on a cloud model. J. Hydrol. 2020, 588, 125051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Pang, B.; Xu, Z.; Peng, D.; Xu, L. Assessment of urban flood susceptibility using semi-supervised machine learning model. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 659, 940–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmati, O.; Pourghasemi, H.R.; Zeinivand, H. Flood susceptibility mapping using frequency ratio and weights-of-evidence models in the Golastan Province, Iran. Geocarto Int. 2016, 31, 42–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edamo, M.L.; Ayele, E.G.; Yisihak Ukumo, T.; Alemayehu Kassaye, A.; Paulos Haile, A. Capability of logistic regression in identifying flood-susceptible areas in a small watershed. H2Open J. 2024, 7, 351–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kindi, K.M.; Alabri, Z. Investigating the role of the key conditioning factors in flood susceptibility mapping through machine learning approaches. Earth Syst. Environ. 2024, 8, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, M. GIS-Based Multi-Criteria Modelling for Fluvial Flood Susceptibility Analysis in South-Eastern Norway. Master’s Thesis, University of South-Eastern Norway, Notodden, Norway, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sharker, R.; Islam, M.R.; Hosen, M.B.; Kader, Z.; Aziz, M.T.; Tahera-Tun-Humayra, U.; Hossain, M.A.; Pervin, R.; Hasan, M.; Roy, A. GIS-based AHP approach to flood susceptibility assessment in Tangail district, Bangladesh. J. Earth Syst. Sci. 2025, 134, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, P.B.; Handique, A.; Dutta, C.K.; Bori, D.; Acharjee, S.; Longkumer, L. Assessment of flood susceptibility in Cachar district of Assam, India using GIS-based multi-criteria decision-making and analytical hierarchy process. Nat. Hazards 2025, 121, 7625–7648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rihan, M.; Mallick, J.; Ansari, I.; Islam, M.R.; Hang, H.T.; Rahman, A. Flash flood susceptibility modeling using optimized deep learning method in the Uttarakhand Himalayas. Earth Sci. Inform. 2025, 18, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SSURGO. Soil Hydrologic Group. Available online: https://www.arcgis.com/home/item.html?id=be2124509b064754875b8f0d6176cc4c (accessed on 19 June 2017).

- Meena, S.R.; Gudiyangada Nachappa, T. Impact of spatial resolution of digital elevation model on landslide susceptibility mapping: A case study in Kullu Valley, Himalayas. Geosciences 2019, 9, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, S.; Karmakar, S.; Mezbahuddin, S.; Hossain, M.M.; Chaudhary, B.S.; Hoque, M.E.; Abdullah Al Mamun, M.; Baul, T.K. The limits of watershed delineation: Implications of different DEMs, DEM resolutions, and area threshold values. Hydrol. Res. 2022, 53, 1047–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, S.H.; Gan, T.Y. Multi-criteria approach to develop flood susceptibility maps in arid regions of Middle East. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 196, 216–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addis, A. GIS– based flood susceptibility mapping using frequency ratio and information value models in upper Abay river basin, Ethiopia. Nat. Hazards Res. 2023, 3, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachappa, T.G.; Piralilou, S.T.; Gholamnia, K.; Ghorbanzadeh, O.; Rahmati, O.; Blaschke, T. Flood susceptibility mapping with machine learning, multi-criteria decision analysis and ensemble using Dempster Shafer Theory. J. Hydrol. 2020, 590, 125275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lappas, I.; Kallioras, A. Flood susceptibility assessment through GIS-based multi-criteria approach and analytical hierarchy process (AHP) in a river basin in Central Greece. Int. Res. J. Eng. Technol. 2019, 6, 738–751. [Google Scholar]

- Essaadia, A.; Abdellah, A.; Ahmed, A.; Abdelouahed, F.; Kamal, E. The normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) of the Zat valley, Marrakech: Comparison and dynamics. Heliyon 2022, 8, e12204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, J.N. Using Google Earth Engine for Landsat NDVI Time Series Analysis to Indicate the Present Status of Forest Stands. Bachelor Thesis, Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, Basel, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Amiri, M.; Pourghasemi, H.R. Mapping the NDVI and monitoring of its changes using Google Earth Engine and Sentinel-2 images. In Computers in Earth and Environmental Sciences; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 127–136. [Google Scholar]

- Sari, D.N.; Rianti, D.I.; Sukmahati, S.M.; Rini, A.M.P. Monitoring Spatio-Temporal of Vegetation Indices Using NDVI and EVI Algorithms on Google Earth Engine (GEE) in Tuntang Watershed Area, Indonesia. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Malang, Indonesia, 24–25 July 2024; p. 012026. [Google Scholar]

- Priscillia, S.; Schillaci, C.; Lipani, A. Flood susceptibility assessment using artificial neural networks in Indonesia. Artif. Intell. Geosci. 2021, 2, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soil Survey Staff Soil Survey Geographic Database. 2024. Available online: https://sdmdataaccess.sc.egov.usda.gov (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Megahed, H.A.; Abdo, A.M.; AbdelRahman, M.A.; Scopa, A.; Hegazy, M.N. Frequency ratio model as tools for flood susceptibility mapping in urbanized areas: A case study from Egypt. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, W.R.; Turner, K.; Bohannon, R.; Berry, M.; Williams, V.; Miggins, D.; Ren, M.; Anthony, E.; Morgan, L.; Shanks, P. Geological, Geochemical, and Geophysical Studies by the US Geological Survey in Big Bend National Park, Texas; US Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, I. Origin of the sodium sulfate deposits of the northern great plains of Canada and the United States. In Geological Survey Research: Chapter B; United States Department of the Interior: Washington, DC, USA, 1968; p. 104. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, W.R.; Knudsen, T.R.; Vice, G.S.; Shaw, L.M. Geologic Hazards and Adverse Construction Conditions; Special Study 127; Utah Geological Survey (UGS), A Division of Utah Department of Natural Resources: Salt Lake, UT, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- TNRIS. Texas Natural Resources Information System. 2023. Available online: https://home-pugonline.hub.arcgis.com/maps/f164b734fedb415082574c438d08e817/explore, published on 5 April 2022 (accessed on 27 March 2024).

- Erima, G.; Gidudu, A.; Bamutaze, Y.; Egeru, A.; Kabenge, I. Spatiotemporal analysis of the hydrological responses to land-use land-cover changes in the Manafwa catchment, eastern Uganda. Prof. Geogr. 2024, 76, 259–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Liu, S.; Mo, X.; Wang, Z. Interpretable flash flood susceptibility mapping in Yarlung Tsangpo River Basin using H2O Auto-ML. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Solanki, Y.P.; Sharma, K.V.; Patel, A.; Tiwari, D.K.; Mehta, D.J. India’s flood risk assessment and mapping with multi-criteria decision analysis and GIS integration. J. Water Clim. Change 2024, 15, 5721–5740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NLCD. National Land Cover Database. 2021. Available online: https://www.mrlc.gov/data (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Akhter, S.; Rahman, M.M.; Monir, M.M. Flood susceptibility analysis to sustainable development using MCDA and support vector machine models by GIS in the selected area of the Teesta River floodplain, Bangladesh. HydroResearch 2025, 8, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadmaan, M.S.; Hassan, K.M. Assessment of flood susceptibility in Sylhet using analytical hierarchy process and geospatial technique. Geomatica 2024, 76, 100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhrel, U. Identifying Urban Pluvial Nuisance Flooding Hotspots Using the Topographic Control Index and Remote Sensing Radar Images. Master’s Thesis, Lamar University-Beaumont, Beaumont, TX, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Di Salvo, C.; Ciotoli, G.; Pennica, F.; Cavinato, G.P. Pluvial flood hazard in the city of Rome (Italy). J. Maps 2017, 13, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, B.; Bach, P.M.; Cunningham, L.; Deletic, A. A Cellular Automata fast flood evaluation (CA-ffé) model. Water Resour. Res. 2019, 55, 4936–4953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, L. A depression-based index to represent topographic control in urban pluvial flooding. Water 2019, 11, 2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschboeck, K.K. Climate and floods. In National Water Summary 1988-89, US Geological Survey Water Supply Paper 2375; USGS Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 1991; pp. 67–88. [Google Scholar]

- PRISM. 2023. Available online: https://prism.oregonstate.edu/explorer/ (accessed on 13 October 2023).

- Abrar, M.F.; Iman, Y.E.; Mustak, M.B.; Pal, S.K. Assessment of vulnerability to flood risk in the Padma River Basin using hydro-morphometric modeling and flood susceptibility mapping. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunwumi, T.; Njoku, C.; Uzoezie, A.; Benson, I. Flood Susceptibility Mapping of Internally Displaced Persons Camps in Maiduguri, Borno State Nigeria. Res. Sq. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Suwanno, P.; Yaibok, C.; Pornbunyanon, T.; Kanjanakul, C.; Buathongkhue, C.; Tsumita, N.; Fukuda, A. GIS-based identification and analysis of suitable evacuation areas and routes in flood-prone zones of Nakhon Si Thammarat municipality. IATSS Res. 2023, 47, 416–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konapala, G.; Kumar, S.V.; Ahmad, S.K. Exploring Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 diversity for flood inundation mapping using deep learning. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2021, 180, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Qiu, X.; Ding, C.; Lei, B. Identification of stable backscattering features, suitable for maintaining absolute synthetic aperture radar (SAR) radiometric calibration of sentinel-1. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcione, V.; Buono, A.; Nunziata, F.; Migliaccio, M. A sensitivity analysis on the spectral signatures of low-backscattering sea areas in Sentinel-1 SAR images. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.T.; Meng, Q. An exploratory study of Sentinel-1 SAR for rapid urban flood mapping on Google Earth Engine. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 113, 103002. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.; Gupta, S.K.; Shukla, D.P. Estimating Suitable Categorization Method for Landslide Susceptibility Mapping of Mandi District. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2022-2022 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 17–22 July 2022; pp. 5481–5484. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Huang, D.; Tang, A.; Han, X. Model performance analysis for landslide susceptibility in cold regions using accuracy rate and fluctuation characteristics. Nat. Hazards 2021, 108, 1047–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Z.; Du, Z.; Zhang, F.; Huang, F.; Chen, J.; Li, W.; Guo, Z. Landslide susceptibility prediction based on remote sensing images and GIS: Comparisons of supervised and unsupervised machine learning models. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Z.; Dahri, N.; Vanclooster, M.; Mehmandoostkotlar, A.; Labbaci, A.; Ben Zaied, M.; Ouessar, M. Hybrid Fuzzy AHP and Frequency Ratio Methods for Assessing Flood Susceptibility in Bayech Basin, Southwestern Tunisia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijal, S.; Nursaputra, M.; Dari, H.U. Flood Susceptibility Analysis Using Frequency Ratio Method in Walanae Watershed. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2024, 19, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Poonia, M.; Rai, A.; Biniwale, R.B.; Tügel, F.; Holzbecher, E.; Hinkelmann, R. Flood Susceptibility Mapping Using GIS-Based Frequency Ratio and Shannon’s Entropy Index Bivariate Statistical Models: A Case Study of Chandrapur District, India. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2024, 13, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, U. An identification and mapping of flood susceptible areas in the Wardha Basin using frequency ratio and statistical index models, India. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 32, 1565–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Pang, B.; Bai, P.; Zhao, G.; Liu, S.; Liu, Y.; Li, M. Flood susceptibility assessment with random sampling strategy in ensemble learning (RF and XGBoost). Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Zhang, S.; Li, R.; Shahabi, H. Performance evaluation of the GIS-based data mining techniques of best-first decision tree, random forest, and naïve Bayes tree for landslide susceptibility modeling. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 644, 1006–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masetic, Z.; Subasi, A. Congestive heart failure detection using random forest classifier. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2016, 130, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N.; Zhang, H.; Dahal, A.; Cheng, W.; Zhao, M.; Lombardo, L. On the use of explainable AI for susceptibility modeling: Examining the spatial pattern of SHAP values. Geosci. Front. 2024, 15, 101800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letoffe, O.; Huang, X.; Asher, N.; Marques-Silva, J. From SHAP scores to feature importance scores. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.11766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Wu, C.; Meadows, M.E.; Feng, M. Pixel level spatial variability modeling using SHAP reveals the relative importance of factors influencing LST. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, D.; Zoh, K. Study on the spatial distribution patterns and formation mechanism of religious sites based on XGBoostSHAP and spatial econometric models: A case study of the Yangtze River Delta, China. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesina, M.; Brake, N.; Haselbach, L.; Hariri Asli, H. Interagency deployment of a shared low-cost flood monitoring system to improve flood resilience across Southeast Texas: A case study. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2024, 17, e12940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BLE. Base Level Engineering, Region 6 Submittal Guidance. 2019. Available online: https://webapps.usgs.gov/infrm/pubs/BLE_Submittal%20Guidance_V5_201904.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2024).

- Ahmed, M.T.; Ahmed, M.W.; Kamruzzaman, M. A systematic review of explainable artificial intelligence for spectroscopic agricultural quality assessment. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 235, 110354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Abbreviation | Definition | Abbreviation | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| AHP | Analytic Hierarchy Process | MCDA | Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network | NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve | NHC | National Hurricane Center |

| BSA | Bivariate Statistical Analysis | NLCD | National Land Cover Database |

| BLE | Base Level Engineering | NRCS | Natural Resources Conservation Service |

| BM | Benchmark (sensor ID, e.g., BM27) | NWS | National Weather Service |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network | PRISM | Parameter-elevation Regressions on Independent Slopes Model |

| DEM | Digital Elevation Model | RF | Random Forest |

| DHS | Department of Homeland Security | ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| DOE | Department of Energy | RS | Remote Sensing |

| DT | Decision Tree | SAR | Synthetic Aperture Radar |

| ECDF | Empirical Cumulative Distribution Function | SETxFCS | Southeast Texas Flood Coordination Study |

| FEMA | Federal Emergency Management Agency | SHAP | Shapley Additive Explanations |

| FN | False Negative | SSURGO | Soil Survey Geographic Database |

| FP | False Positive | SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| FR | Frequency Ratio | SWAT | Soil and Water Assessment Tool |

| FPR | False Positive Rate | TNRIS | Texas Natural Resources Information System |

| GEE | Google Earth Engine | TN | True Negative |

| GIS | Geographic Information System | TP | True Positive |

| LULC | Land Use/Land Cover | TPR | True Positive Rate |

| LR | Logistic Regression | TWI | Topographic Wetness Index |

| ML | Machine Learning | WoE | Weights of Evidence |

| MLT | Machine Learning Technique | XGBoost | Extreme Gradient Boosting |

| Factor | Data Types | Resolution | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| DEM | Raster | 30 m × 30 m | USGS Elevation DATA |

| Slope | Raster | 30 m × 30 m | DEM |

| TWI | Raster | 30 m × 30 m | DEM |

| NDVI | Raster | 30 m × 30 m | Landsat 8 imagery |

| Soil type | Polygon | Soil Survey Geographic Database 2.3.2 [48] | |

| Rock Unite | Polygon | RockUnitPoly250K, Texas (TNRIS) Geologic Data | |

| LULC | Raster | 30 m × 30 m | NLCD 2021 Land Cover (CONUS) |

| Depression Areas | Raster | 30 m × 30 m | DEM |

| Soil Hydrology group | Polygon | SSURGO Database | |

| Average Precipitation | Polygon | PRISM (2018–2023) | |

| Distance for streams and waterbodies | Polygon | Jefferson County Drainage District No. 6 | |

| Distance from Road | Polygon | TxDOT Roadways dataset |

| Flood Occurrence (Times) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of water pixels | 496,973 | 144,806 | 35,630 | 7342 | 1636 | 238 |

| Name | Class | Total Area | Total Area Percentage | Number of Flood Events | Event Percentage | Frequency Ratio (Fr) | FR × 100 | FR Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dem | <0.55 | 543,130 | 20.132 | 11,812 | 26.339 | 1.308 | 130.834 | 130 |

| 0.55–1.42 | 538,189 | 19.948 | 10,749 | 23.969 | 1.202 | 120.153 | 120 | |

| 1.42–3.52 | 538,873 | 19.974 | 8313 | 18.537 | 0.928 | 92.805 | 92 | |

| 3.52–7.12 | 538,586 | 19.963 | 5280 | 11.774 | 0.590 | 58.977 | 58 | |

| >7.12 | 539,115 | 19.983 | 8692 | 19.382 | 0.970 | 96.993 | 96 | |

| Slope | <0.1 | 903,006 | 33.471 | 23,418 | 52.219 | 1.560 | 156.01 | 156 |

| 0.1–1.6 | 1,111,196 | 41.188 | 13,145 | 29.311 | 0.712 | 71.166 | 71 | |

| >1.6 | 683,691 | 25.342 | 8283 | 18.470 | 0.729 | 72.883 | 72 | |

| Distance from the roads | <120 | 523,825 | 19.416 | 5497 | 12.258 | 0.631 | 63.131 | 63 |

| 120–414 | 554,926 | 20.569 | 6304 | 14.057 | 0.683 | 68.341 | 68 | |

| 414–921 | 540,024 | 20.017 | 7564 | 16.867 | 0.843 | 84.263 | 84 | |

| 921–2247 | 539,084 | 19.982 | 11,171 | 24.910 | 1.247 | 124.663 | 124 | |

| >2247 | 540,034 | 20.017 | 14,310 | 31.909 | 1.594 | 159.411 | 159 | |

| Distance from Major Streams | <100 | 521,718 | 19.338 | 12,032 | 26.830 | 1.387 | 138.740 | 138 |

| 100–150 | 181,893 | 6.742 | 3031 | 6.759 | 1.002 | 100.247 | 100 | |

| 150–200 | 163,546 | 6.062 | 2575 | 5.742 | 0.947 | 94.719 | 94 | |

| 200–250 | 149,130 | 5.528 | 2250 | 5.017 | 0.908 | 90.765 | 90 | |

| >250 | 1,681,606 | 62.330 | 24,958 | 55.653 | 0.893 | 89.287 | 89 | |

| Distance from minor Streams | <25 | 271,804 | 10.075 | 4404 | 9.820 | 0.975 | 97.475 | 97 |

| 25–50 | 198,580 | 7.361 | 3253 | 7.254 | 0.985 | 98.548 | 98 | |

| 50–75 | 253,717 | 9.404 | 4258 | 9.495 | 1.010 | 100.962 | 100 | |

| 75–100 | 191,096 | 7.083 | 3236 | 7.216 | 1.019 | 101.873 | 101 | |

| >100 | 1,782,696 | 66.077 | 29,695 | 66.215 | 1.002 | 100.209 | 100 | |

| TWI | <4 | 558,867 | 20.715 | 6695 | 14.929 | 0.721 | 72.068 | 72 |

| 4–5.1 | 510,613 | 18.926 | 5705 | 12.721 | 0.672 | 67.215 | 67 | |

| 5.1–7.5 | 548,889 | 20.345 | 7290 | 16.256 | 0.799 | 79.899 | 79 | |

| 7.5–10.7 | 532,726 | 19.746 | 9774 | 21.795 | 1.104 | 110.375 | 110 | |

| >10.7 | 546,798 | 20.268 | 15,382 | 34.300 | 1.692 | 169.234 | 169 | |

| NDVI | <−0.135 | 593,018 | 21.981 | 10,045 | 22.399 | 1.019 | 101.902 | 101 |

| −0.13–0.21 | 486,977 | 18.050 | 6389 | 14.247 | 0.789 | 78.927 | 78 | |

| 0.21–0.40 | 543,431 | 20.143 | 7817 | 17.431 | 0.865 | 86.536 | 86 | |

| 0.40–0.53 | 534,539 | 19.813 | 12,035 | 26.836 | 1.354 | 135.44 | 135 | |

| >0.53 | 539,928 | 20.013 | 8560 | 19.088 | 0.954 | 95.376 | 95 | |

| Soil Type | Clay | 1,157,825 | 42.916 | 21,257 | 47.400 | 1.104 | 110.44 | 110 |

| Clay loam | 292,744 | 10.851 | 4075 | 9.087 | 0.837 | 83.741 | 83 | |

| Coarse sand | 3381 | 0.125 | 39 | 0.087 | 0.694 | 69.394 | 69 | |

| Fine sand | 3380 | 0.125 | 139 | 0.310 | 2.474 | 247.400 | 247 | |

| Loam | 200,463 | 7.430 | 4265 | 9.510 | 1.280 | 127.99 | 127 | |

| Sandy clay loam | 68,769 | 2.549 | 1759 | 3.922 | 1.539 | 153.87 | 153 | |

| Silt loam | 76,439 | 2.833 | 1594 | 3.554 | 1.255 | 125.45 | 125 | |

| Silty clay | 334,235 | 12.389 | 3905 | 8.708 | 0.703 | 70.286 | 70 | |

| Silty clay loam | 98,628 | 3.656 | 2058 | 4.589 | 1.255 | 125.53 | 125 | |

| Very fine sandy loam | 9934 | 0.368 | 40 | 0.089 | 0.242 | 24.223 | 24 | |

| water | 61,629 | 2.284 | 811 | 1.808 | 0.792 | 79.166 | 79 | |

| no-data | 390,466 | 14.473 | 4904 | 10.935 | 0.756 | 75.556 | 75 | |

| Rock Unit | F S | 27,520 | 1.020 | 322 | 0.718 | 0.704 | 70.390 | 70 |

| Qal | 663,801 | 24.604 | 9705 | 21.641 | 0.880 | 87.955 | 87 | |

| Qb | 647,102 | 23.985 | 9958 | 22.205 | 0.926 | 92.576 | 92 | |

| Qbb | 79,950 | 2.963 | 2206 | 4.919 | 1.660 | 165.99 | 165 | |

| Qbc | 1,134,389 | 42.047 | 20,195 | 45.032 | 1.071 | 107.09 | 107 | |

| Qbi | 44,282 | 1.641 | 1271 | 2.834 | 1.727 | 172.67 | 172 | |

| Qd | 6689 | 0.248 | 46 | 0.103 | 0.414 | 41.371 | 41 | |

| Ql | 27 | 0.001 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0 | |

| Wa | 94,133 | 3.489 | 1143 | 2.549 | 0.730 | 73.047 | 73 | |

| LULC | Agricultural Land | 1,052,065 | 19.498 | 18,378 | 20.490 | 1.051 | 105.08 | 105 |

| Barren | 7890 | 0.292 | 328 | 0.731 | 2.501 | 250.09 | 250 | |

| Developed | 457,827 | 16.970 | 4576 | 10.204 | 0.601 | 60.129 | 60 | |

| Forested Upland | 36,632 | 1.358 | 426 | 0.950 | 0.700 | 69.960 | 69 | |

| Grassland and pasture | 13,773 | 0.511 | 557 | 1.242 | 2.433 | 243.29 | 243 | |

| Shrubland | 4988 | 0.185 | 54 | 0.120 | 0.651 | 65.128 | 65 | |

| Wetlands | 998,782 | 37.021 | 17,493 | 39.007 | 1.054 | 105.36 | 105 | |

| water | 125,936 | 4.668 | 3034 | 6.765 | 1.449 | 144.93 | 144 | |

| Depression | <0 | 1,348,059 | 0.500 | 29,032 | 0.647 | 1.296 | 129.559 | 129 |

| >0 | 1,349,834 | 0.500 | 15,814 | 0.353 | 0.705 | 70.479 | 70 | |

| Average precipitation | <1554 | 535,490 | 19.848 | 10,057 | 22.426 | 1.130 | 112.984 | 112 |

| 1554–1602 | 531,687 | 19.707 | 7978 | 17.790 | 0.903 | 90.269 | 90 | |

| 1602–1636 | 549,570 | 20.370 | 11,096 | 24.742 | 1.215 | 121.46 | 121 | |

| 1636–1695 | 542,972 | 20.126 | 10,274 | 22.910 | 1.138 | 113.83 | 113 | |

| >1695 | 538,174 | 19.948 | 5441 | 12.133 | 0.608 | 60.821 | 60 | |

| Soil Hydrologic groups | A | 31,459 | 1.166 | 741 | 1.652 | 1.417 | 141.701 | 141 |

| A/D | 17,303 | 0.641 | 156 | 0.348 | 0.542 | 54.238 | 54 | |

| B/D | 95,411 | 3.537 | 2199 | 4.903 | 1.387 | 138.65 | 138 | |

| C | 1900 | 0.070 | 13 | 0.029 | 0.412 | 41.161 | 41 | |

| C/D | 78,197 | 2.898 | 1576 | 3.514 | 1.212 | 121.24 | 121 | |

| D | 2,473,623 | 91.687 | 40,161 | 89.553 | 0.977 | 97.672 | 97 |

| Random Forest | Xgboost | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Optimum Value | Parameter | Optimum Value |

| n_estimators | 50 | lambda | 0.03251274199317688 |

| max_depth | 20 | alpha | 0.6440814745700857 |

| min_samples_split | 10 | colsample_bytree | 0.9 |

| min_samples_leaf | 4 | subsample | 0.6 |

| learning_rate | 0.008 | ||

| n_estimators | 1000 | ||

| max_depth | 60 | ||

| min_child_weight | 1 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Feizbahr, M.; Brake, N.; Arbabkhah, H.; Hariri Asli, H.; Woods, K. Flood Susceptibility Mapping Using Machine Learning and Geospatial-Sentinel-1 SAR Integration for Enhanced Early Warning Systems. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3471. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17203471

Feizbahr M, Brake N, Arbabkhah H, Hariri Asli H, Woods K. Flood Susceptibility Mapping Using Machine Learning and Geospatial-Sentinel-1 SAR Integration for Enhanced Early Warning Systems. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(20):3471. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17203471

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeizbahr, Mahdi, Nicholas Brake, Homayoon Arbabkhah, Hossein Hariri Asli, and Kolby Woods. 2025. "Flood Susceptibility Mapping Using Machine Learning and Geospatial-Sentinel-1 SAR Integration for Enhanced Early Warning Systems" Remote Sensing 17, no. 20: 3471. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17203471

APA StyleFeizbahr, M., Brake, N., Arbabkhah, H., Hariri Asli, H., & Woods, K. (2025). Flood Susceptibility Mapping Using Machine Learning and Geospatial-Sentinel-1 SAR Integration for Enhanced Early Warning Systems. Remote Sensing, 17(20), 3471. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17203471