1. Introduction

Three-dimensional (3-D) radar imaging has evolved into a cornerstone sensing modality for autonomous drones, ground-based surveillance, and compact antenna-test facilities. By synthesizing a large synthetic aperture in both elevation and azimuth, 3-D radar can recover volumetric scattering distributions that reveal a target’s geometry, material composition, and even internal cavities [

1,

2]. In recent years, sparse 3-D imaging—that is, reconstructing high-resolution scenes from far fewer spatial samples—has received considerable attention because it dramatically shortens acquisition time and reduces data-handling requirements [

3,

4]. Yet, sparse sampling also tightens the tolerance on antenna-trajectory accuracy: any position error directly maps into phase error that cannot be averaged out by dense measurements. Even millimeter-level deviations translate into conspicuous artifacts or complete imaging failure at Ku- and millimeter-wave bands.

One pragmatic sparse-sampling architecture is synchronized vertical scanning and azimuthal rotation (SVSAR) [

5]: the radar antenna (or the target on a turn-table) rotates horizontally while the antenna simultaneously scans linearly along the vertical rail. The helical or V-shaped trajectory generated thereby is easy to implement on existing cylindrical radar cross section (RCS) ranges and is compatible with the limited payload of small drones. Nevertheless, synchronizing two mechanical axes plus the timing of transmit/receive (T/R) events is non-trivial; unmodelled delay, servo jitter, or wind-induced vibration may offset the antenna from its nominal coordinates at each pulse repetition interval (PRI). When compounded over hundreds of pulses, these sub-millimeter offsets cause severe phase-wrapping errors and blur the 3-D reconstruction.

Numerous studies have attempted to correct trajectory errors after-the-fact [

6]. Multi-channel interferometric calibration [

7] and phase-gradient autofocus (PGA) variants [

8] may estimate inter-pulse phase drifts, but they require either extra hardware channels or strongly scattering calibration poles. Sub-aperture based residual compensation, as proposed by Zhang et al. [

9], effectively suppresses slow drift yet is less effective against high-frequency servo vibration. Manzoni et al. [

10] leveraged on-board Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) in automotive multiple-input multiple-output Synthetic Aperture Radar (MIMO-SAR) to remove constant-velocity errors, whereas the method deteriorates when IMU bias accumulates. Yang et al. [

11] exploited multi-channel interferometric phase to infer array deformation, but the multi-receiver configuration increases cost and weight. Sun et al. [

12] analyzed frequency-synchronization error in distributed SAR; their framework, however, presumes precisely surveyed base-lines and is not directly transferable to single-platform near-field setups.

The last five years have witnessed a surge of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV)-oriented trajectory–localization studies that complement sparse 3-D radar imaging. O. Nacar et al. [

13] propose a Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU)-based network that forecasts future velocities rather than positions, yielding sub-centimeter mean-square error. However, this method is purely data-driven and cannot compensate for mechanical jitter, providing insufficient support for the millimeter-level phase accuracy required for radar imaging. X. Jing et al. [

14] formulate a weighted optimization that balances down-link capacity and radar-based target localization, solved via iterative refinement. This method assumes that the UAV’s attitude is known and does not discuss trajectory errors, making it difficult to directly meet the high-precision requirements of sparse near-field imaging. A. Gupta et al. [

15] examine visual-inertial fusion and Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM) pipelines for airborne platforms [

16]. However, the performance of the visual/IMU method is limited in indoor dark rooms or metallic environments, and it does not address the issue of millimeter-wave phase alignment. Y. Pan et al. [

17] optimize multi-drone paths jointly with sensing–communication power budgets. This method assumes accurate positioning and lacks modeling for mechanical errors and timing jitter. Y. Hou et al. [

18] design a backstepping-sliding-mode controller to reject wind disturbances in quadrotors. However, this method relies on external precise location feedback and cannot independently provide the absolute coordinates required for radar positioning.

Existing research has made progress in trajectory prediction, cooperative planning, and SLAM localization, but solutions that balance sparse sampling efficiency with millimeter-level trajectory accuracy without requiring expensive hardware have not yet emerged. Existing compensation technologies either rely on expensive auxiliary sensors [

19,

20,

21,

22] (laser trackers, differential Global Positioning System (GPS)) or assume motion errors to be slow variables, thereby ignoring high-frequency jitter. For UAV radar [

23,

24] or indoor near-field turntable testing, the addition of sensors is often limited by load, power consumption, or line of sight. Moreover, many algorithms iterate in the image domain, and once the phase error becomes too large, it becomes difficult to converge. Therefore, there is an urgent need for a positioning solution that does not require mechanical structure modifications, is compatible with ground rails and drone platforms, can coexist with test scenarios, and provides centimeter to millimeter-level accuracy.

This paper introduces a microwave three-point ranging (M3PR) strategy tailored for sparse 3-D radar imaging under synchronized scanning–rotation sampling. Three low-cost metallic calibration spheres are placed outside the region of interest. At every pulse, the radar measures the round-trip distances to these spheres; the intersection of the resulting distance spheres yields the instantaneous radar position. The key contributions of this work are highlighted below:

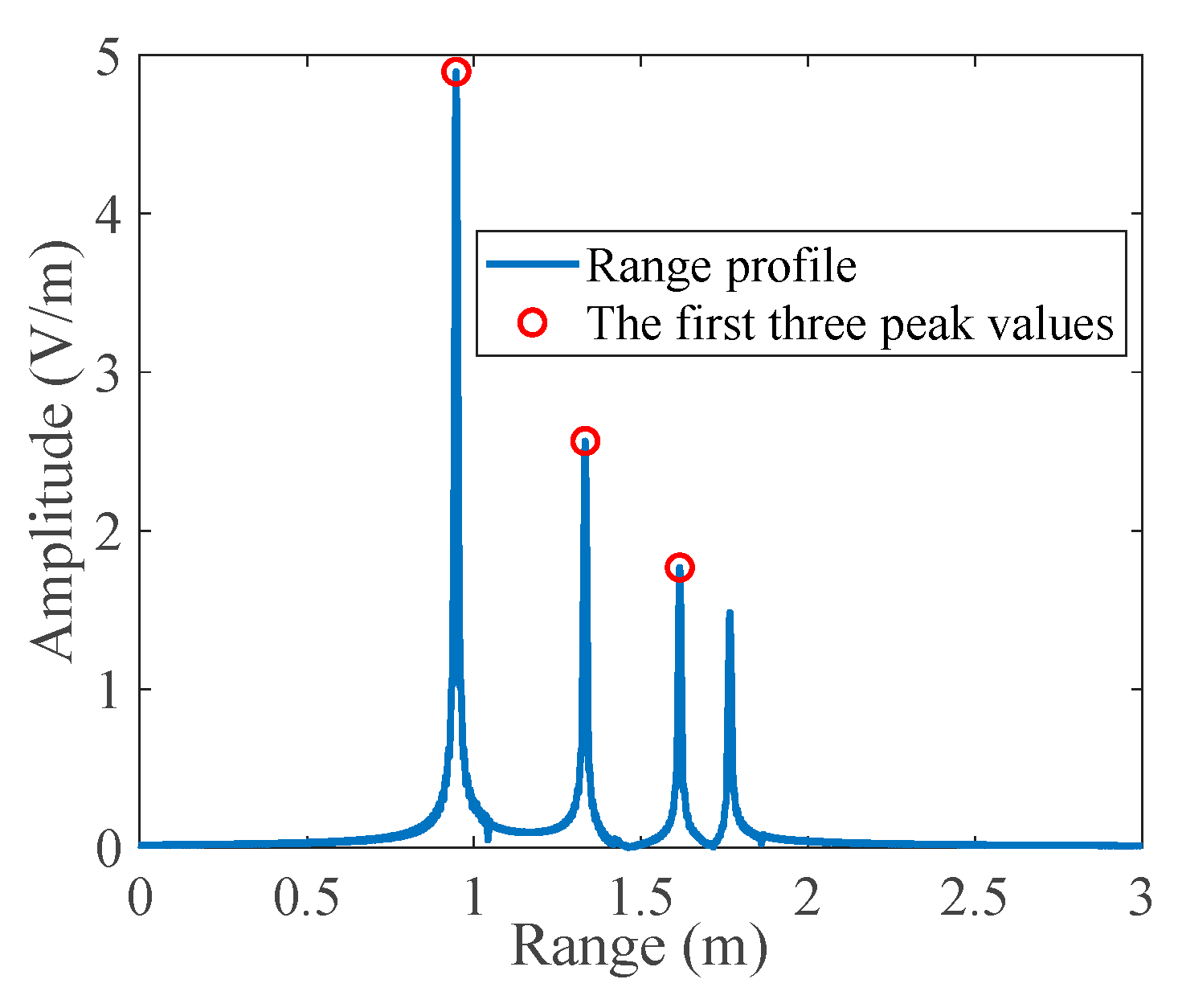

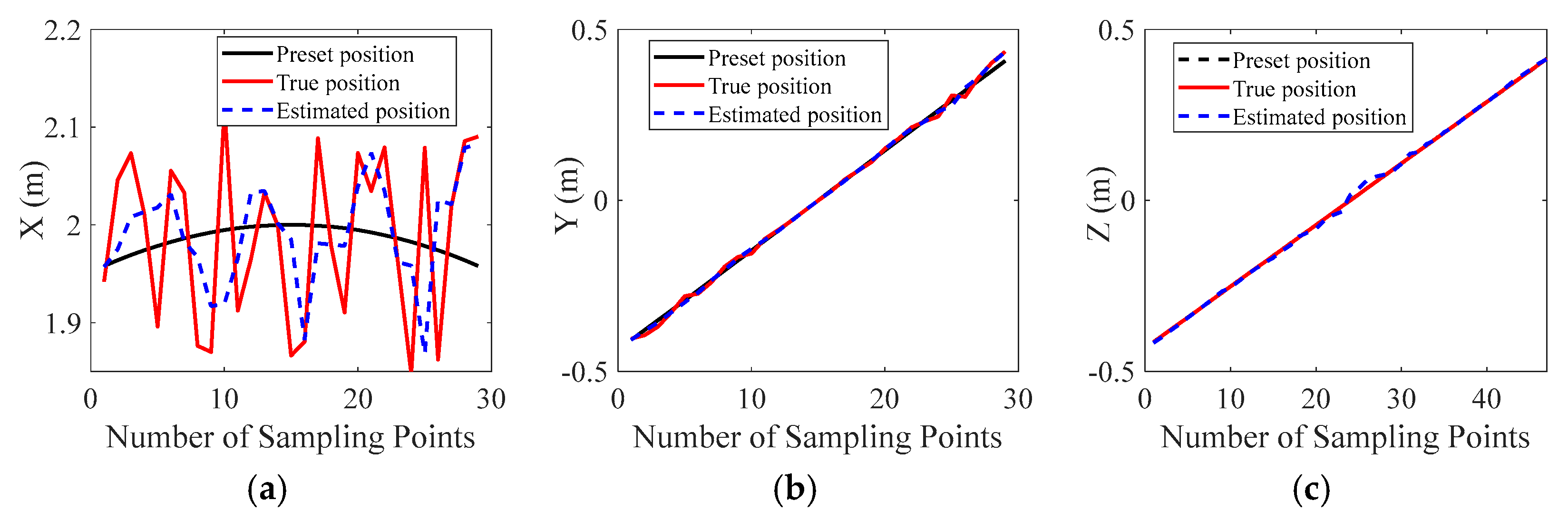

A novel trajectory estimation method is proposed for 3D radar imaging, focusing on precise radar localization via microwave three-point ranging. The method requires no communication infrastructure and relies solely on three fixed microwave-reflective calibration spheres placed outside the imaging region. By extracting one-dimensional range profiles and using the known coordinates of the sphere centers, the radar’s spatial position can be uniquely determined at each sampling instance. An analytical solution for position estimation is derived, and the sensitivity of microwave imaging systems to trajectory jitter is analyzed.

Based on the proposed localization method, its applicability is further investigated in both ISAR and SAR system configurations. For each system, a rational layout strategy for the three reference spheres is developed to ensure peak identifiability and accurate phase compensation under different geometric constraints. These layout designs provide theoretical support for future engineering implementation.

The subsequent sections of this paper are structured as follows.

Section 2 introduces the proposed trajectory estimation method and its analytical solution for 3D radar imaging, along with an analysis of the sensitivity of phase errors to trajectory deviations.

Section 3 presents the system configuration and parameter settings used for validation.

Section 4 provides trajectory localization and 3D imaging results based on the proposed method.

Section 5 discusses the positioning and phase compensation accuracy, the applicability of the proposed method to both ISAR and SAR configurations, and the layout strategies for the three reference spheres under each scenario. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the study.

2. Methods

2.1. System Model

Modern 3-D radar imaging platforms employ a variety of sampling geometries—including planar, spherical, and cylindrical trajectories—to acquire volumetric scattering data. Among these choices, cylindrical scanning strikes a favorable balance between mechanical simplicity and angular diversity, making it the de facto standard in compact antenna-test ranges and drone-borne payloads. To lay a clear theoretical foundation, we first review the conventional full-coverage cylindrical model, in which the radar (or target) rotates through a complete 360° at each elevation step. We then extend this formulation to a synchronized linear-scan and rotation scheme that enables sparse acquisition while preserving 3-D resolution. The mathematical relationships derived in the following subsections serve as the basis for the subsequent phase-error sensitivity analysis and for the proposed microwave three-point positioning method.

2.1.1. Traditional Cylindrical Sampling Model

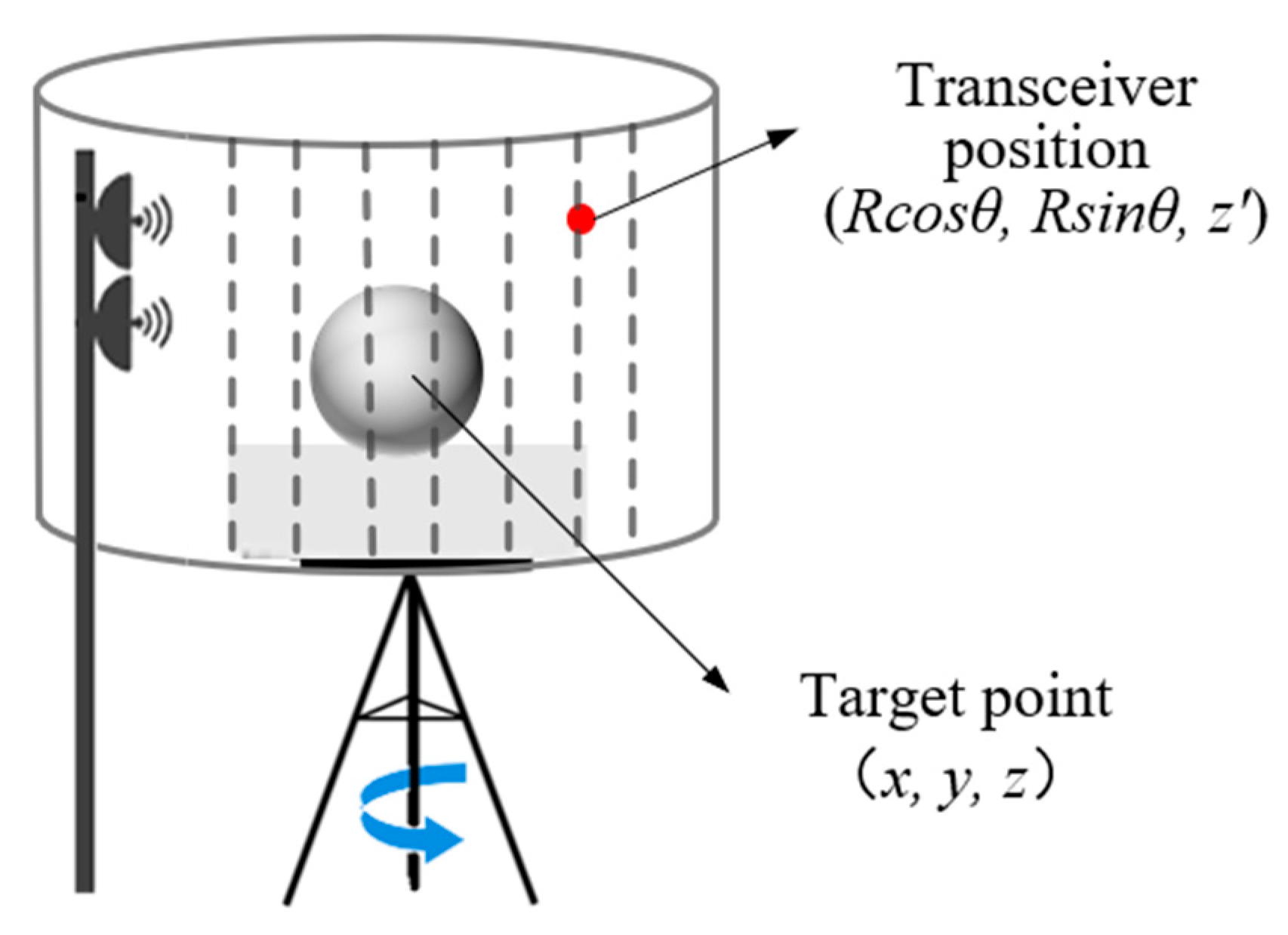

Figure 1 illustrates the model of the cylindrical sampling 3D imaging system. The imaging Cartesian coordinate system is defined with its origin at the center of the turntable. The coordinates of any imaging position are denoted by

, and the corresponding scattering intensity is

. The distance from the cylindrical sampling array of length

to the z-axis of the imaging coordinate system is

. In a classical cylindrical acquisition, the measurement proceeds as follows: the turntable first rotates by a prescribed azimuth increment and is then held stationary while the Tx/Rx antenna performs a vertical mechanical scan, transmitting and receiving echoes throughout the scan. After the vertical sweep is completed, the turntable advances by the next azimuth increment and the process is repeated. The sequence continues until the turntable has covered the full azimuthal sector of interest, thereby synthesizing a virtual cylindrical aperture for 3-D image reconstruction. The coordinates of the radar transmit-receive positions are

.

The cylindrical sampling approach has been widely adopted in indoor imaging measurements. However, in outdoor environments, its application becomes more challenging due to the typically large dimensions of the measured targets, which require long and heavy guide rails. Moreover, environmental factors—particularly wind—can induce mechanical vibrations during antenna scanning, and the limited precision of the rail system further exacerbates positioning errors. As a result, the actual position of the transmitting/receiving antenna may deviate significantly from its nominal trajectory, leading to phase compensation errors and potentially causing imaging failure. To address the positioning errors caused by rail-system limitations and external disturbances, there is a pressing need for a trajectory localization method that can accurately determine the antenna’s actual position and remain compatible with existing measurement systems.

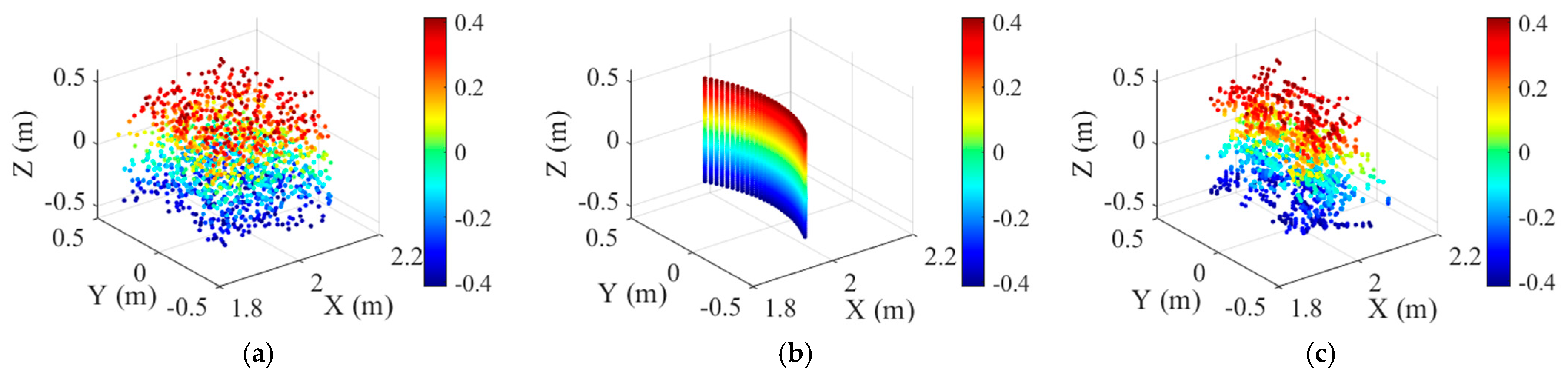

2.1.2. Sampling Model for Linear Scanning and Rotationally Synchronized Motion

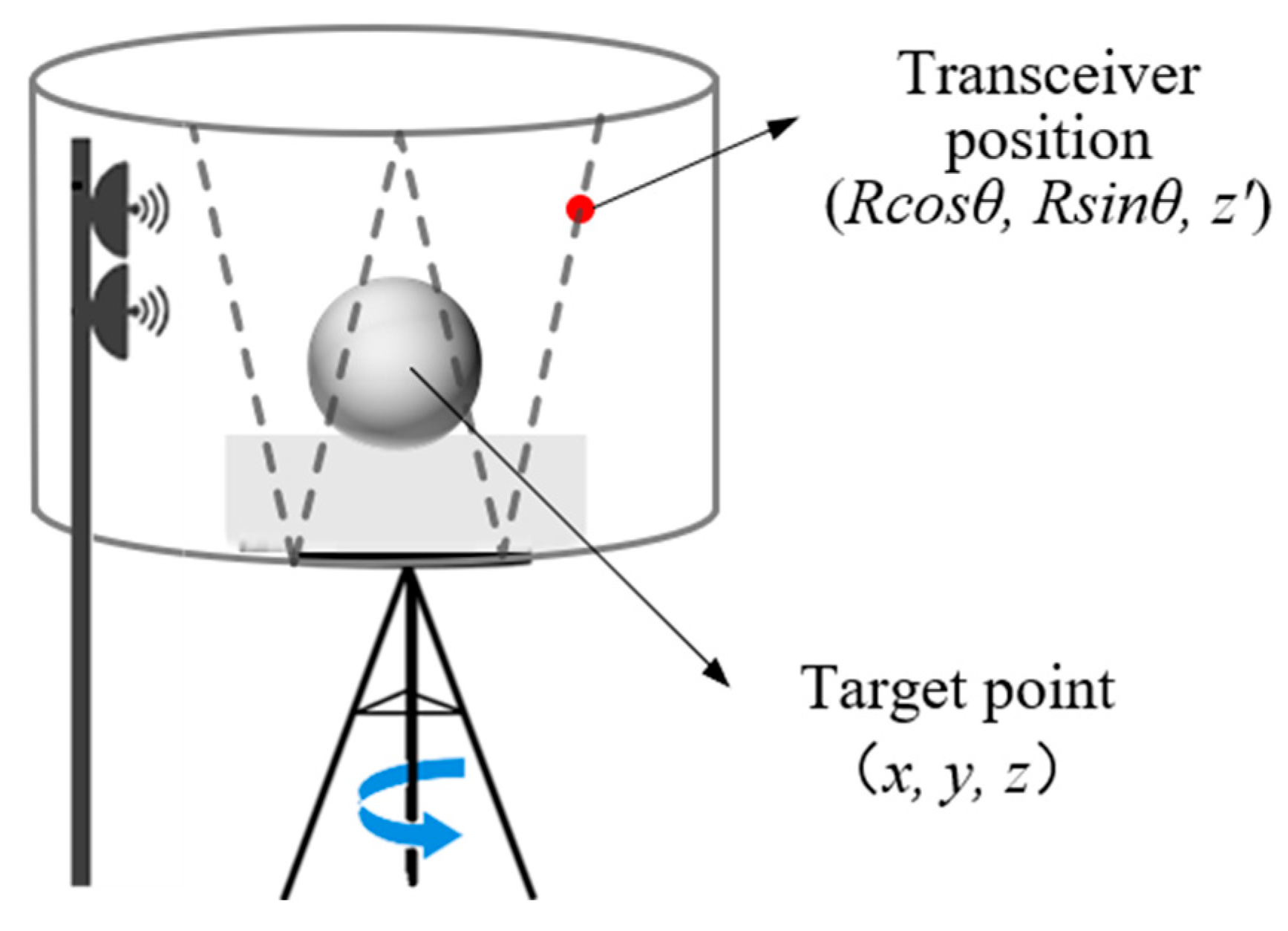

The synchronized scanning–rotation sampling scheme [

5] is a novel sparse acquisition method that offers simple operation and acceptable imaging quality, making it well-suited for integration with existing near-field imaging systems. In practical measurements, the procedure is as follows: after configuring an appropriate speed ratio between the turntable and the vertically scanning antenna, both begin moving simultaneously while the Tx/Rx antenna transmits and receives signals in parallel. The vertical scan operates in a back-and-forth manner and continues in synchrony with the turntable until the full azimuthal sector is covered. This process results in a virtual cylindrical “V”-shaped sampling trajectory, as illustrated in

Figure 2.

This sparse sampling method has been validated through principle-level experiments in an anechoic chamber. However, its practical deployment may still be affected by position errors caused by timing jitter and rail-induced vibration, which can significantly degrade phase compensation during imaging. Therefore, it is necessary to develop a jitter-error mitigation approach that enables accurate localization of the antenna’s actual motion trajectory, thereby enhancing the engineering applicability and practical value of this sparse sampling scheme.

2.2. Phase Error Sensitivity Analysis of Trajectory Deviation

To quantify the impact of scanning antenna trajectory errors on 3D imaging quality, this section derives the phase mismatch threshold based on the monostatic near-field scattering model and establishes a theoretical criterion for complete image defocusing.

For a monostatic system, the time-domain echo corresponding to the

-th pulse at frequency

(with wave number

) can be expressed as:

where

, which denotes the distance between the antenna position

and the scatterer position

, and

is the complex scattering amplitude of the

-th scatterer. In ideal imaging, reconstruction is performed using exact geometric compensation.

where

is computed from the nominal trajectory. If a trajectory deviation

exists, the actual distance becomes:

This results in a residual phase error given by:

A commonly used metric for evaluating image focusing quality can be expressed as:

where

is the root-mean-square (rms) of the residual phase error. Combining with Equation (4), the threshold for the trajectory rms position error is given by:

In other words, when the rms of the antenna jitter exceeds approximately , the focusing quality drops below 0.8, and the image begins to degrade noticeably. If the jitter approaches , resulting in , more than half of the main-lobe energy is lost, leading to severe defocusing and imaging failure.

In addition, the impact of antenna jitter on imaging accuracy varies with its direction in space. Axial (radial) errors—typically caused by rail straightness deviations or target eccentricity—directly affect the range term and therefore have the most significant influence on phase accuracy. In contrast, lateral errors (vertical or horizontal) introduce second-order phase terms under near-field conditions, with a magnitude on the order of . While their impact is relatively minor for the current imaging setup, they may still be non-negligible in short-range systems.

2.3. The Proposed Three-Point Positioning Method

A laser tracker (LT) combines laser ranging and angular encoding to rapidly measure 3-D coordinates. Using fixed target spheres to define a reference frame and a corner-cube retro-reflector (CCR) on the object, the beam returns along the incident path for interferometric/phase processing; range, azimuth, and elevation yield 3-D position via spherical-to-Cartesian transformation (Equation (7)). Leveraging spherical trilateration, LTs offer fast, sub-millimeter accuracy but require costly opto-mechanics and stable Line of Sight (LOS), limiting outdoor use. For portable radar localization needing only millimeter-level accuracy, such precision is unnecessary, motivating our low-cost three-sphere ranging scheme.

wherein,

is the distance obtained by combining measurements from the absolute distance meter and the interferometer, while

and

represent the azimuth and elevation angles, respectively.

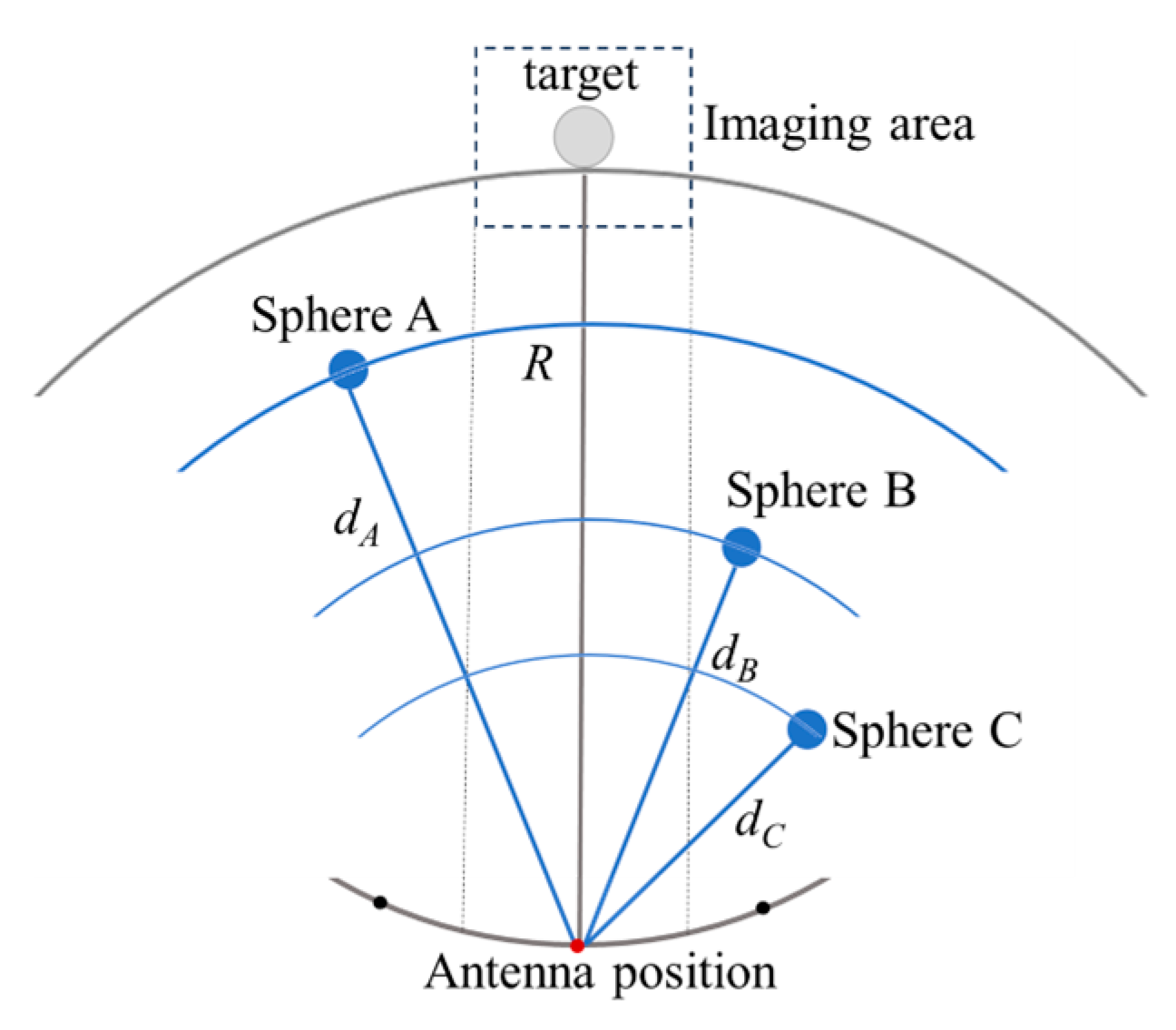

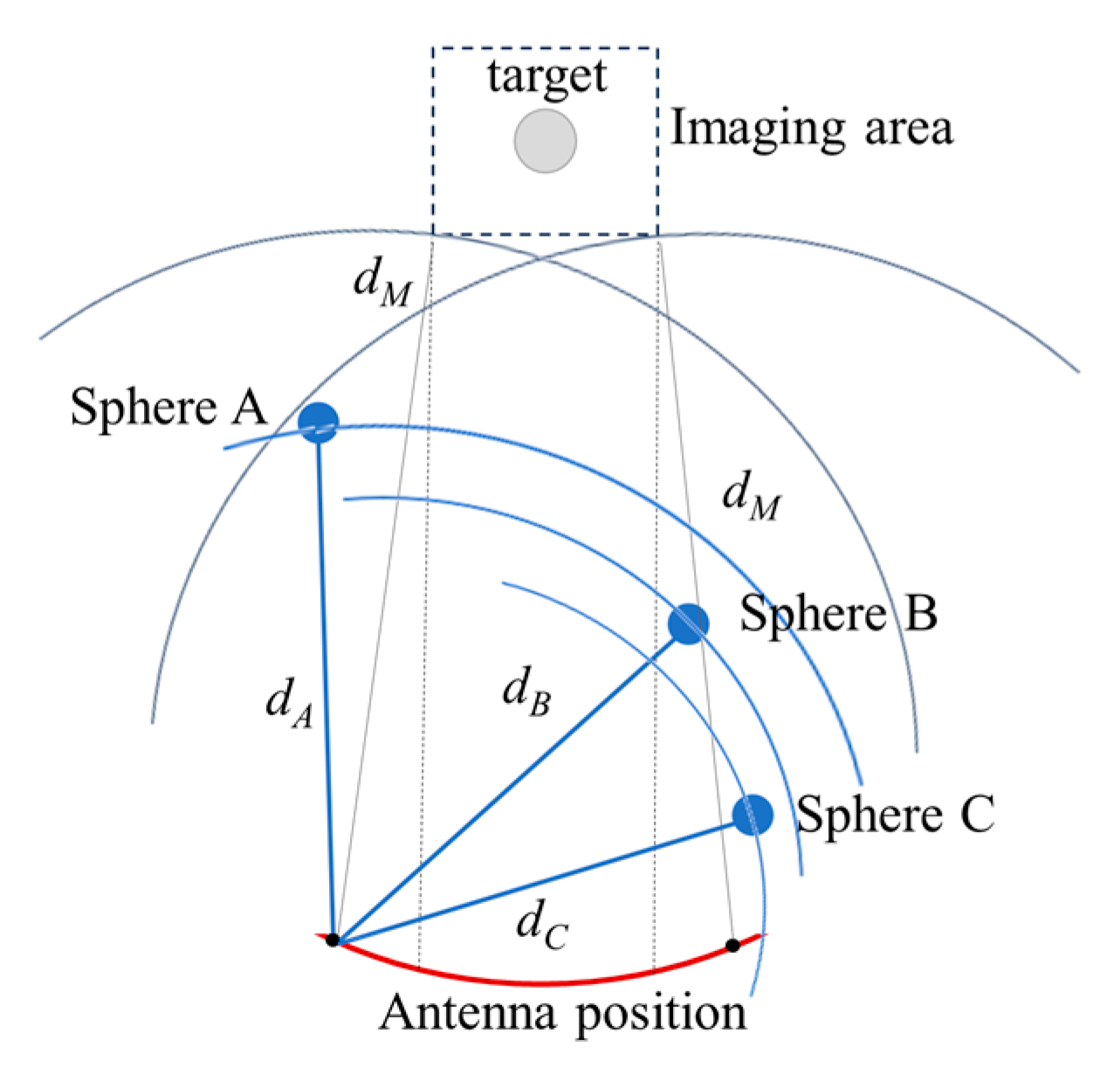

2.3.1. Three-Point Localization Algorithm

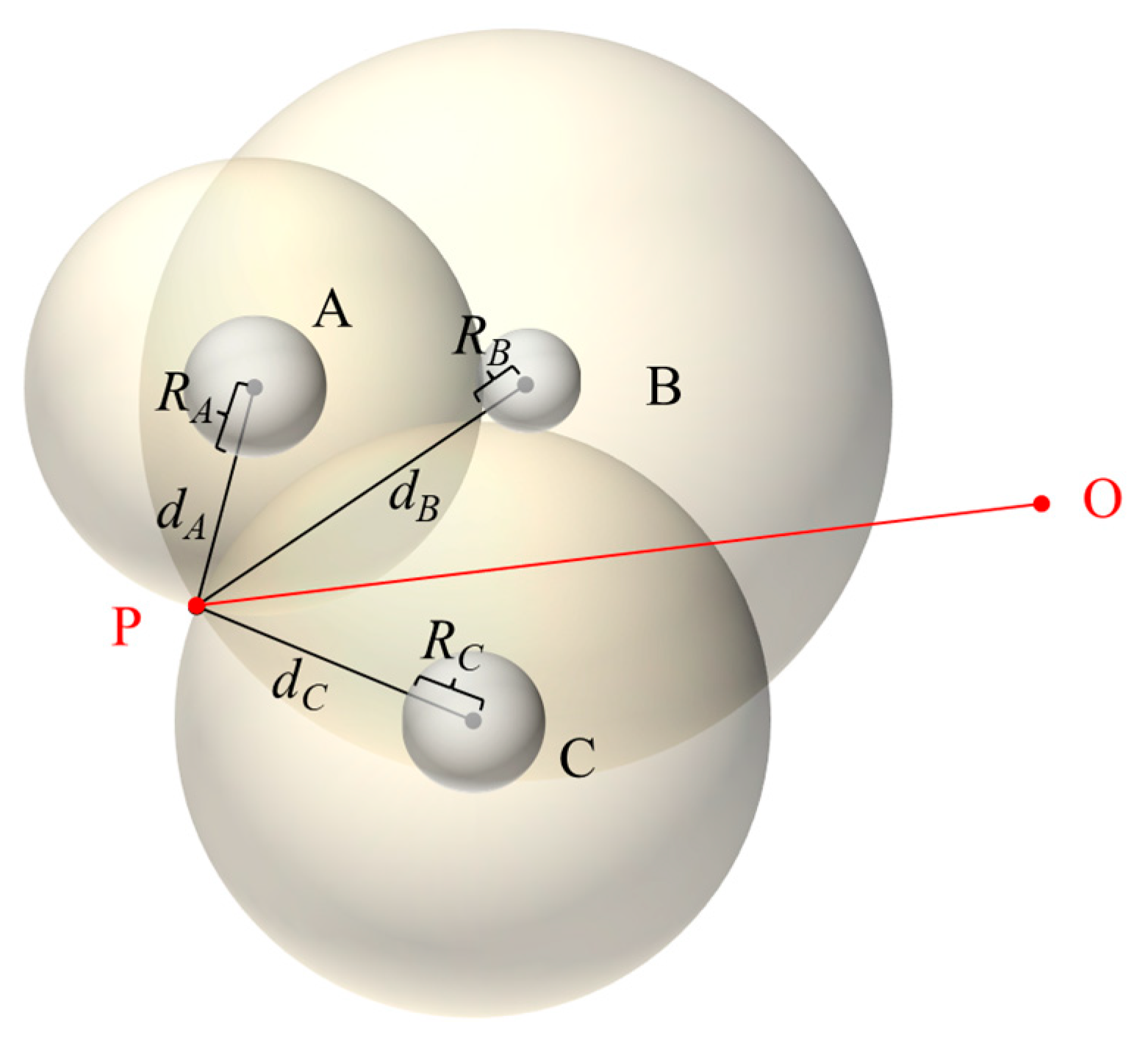

To address this, we propose using three fixed-position metallic spheres with known spatial coordinates. During the frequency sweep of the imaging process, the one-dimensional range profiles to these spheres are extracted. Taking each sphere’s center as the origin and its corresponding range as the radius, three spheres are constructed in space. The unique intersection point of these three spheres represents the actual position of the antenna. A schematic illustration of this principle is shown in

Figure 3.

The three spherical surfaces in

Figure 3 can be represented by the following system of equations:

This system of equations describes the geometric constraints between the antenna position

and the surfaces of the three spheres. Here,

denotes the center of sphere A with radius

;

is the center of sphere B with radius

; and

is the center of sphere C with radius

. To solve the system, any two Equations (e.g., those for spheres A and B) can be subtracted and expanded to eliminate the quadratic terms, resulting in a linear equation in

:

Applying the same operation to spheres A and C yields a second linear plane equation:

where is matrix multiplication.

A solution to the linear equations yields a line, where

is a particular solution and

is the null-space direction vector:

Substituting the line equation into any of the spherical Equations (e.g., sphere A) yields Equation (15), which can be expanded into a quadratic equation in the parameter

, as shown in Equation (16).

The constant term is given in Equation (17), and solving the quadratic using the root formula in Equation (18) provides two intersection points. The physically meaningful solution is selected as the final antenna position.

Although the intersection of three spheres should theoretically yield a unique solution for the antenna’s current position, in practice, the position must be solved at every time step, and factors such as measurement noise in the range estimates can prevent the three spheres from intersecting exactly. In such cases, the quadratic equation may have no real solution, causing the analytical method to fail and making it highly sensitive to noise. To improve robustness, this study adopts a nonlinear least squares strategy to estimate the antenna position by minimizing the residuals between the estimated and measured distances to the three reference points, as formulated in Equation (16).

The algorithm avoids the need for analytical intersection and guarantees a stable solution, providing enhanced fault tolerance and engineering applicability. It is well-suited for high-precision estimation of the antenna trajectory under range measurement errors and noisy conditions.

2.3.2. Three-Point Localization Measurement Model

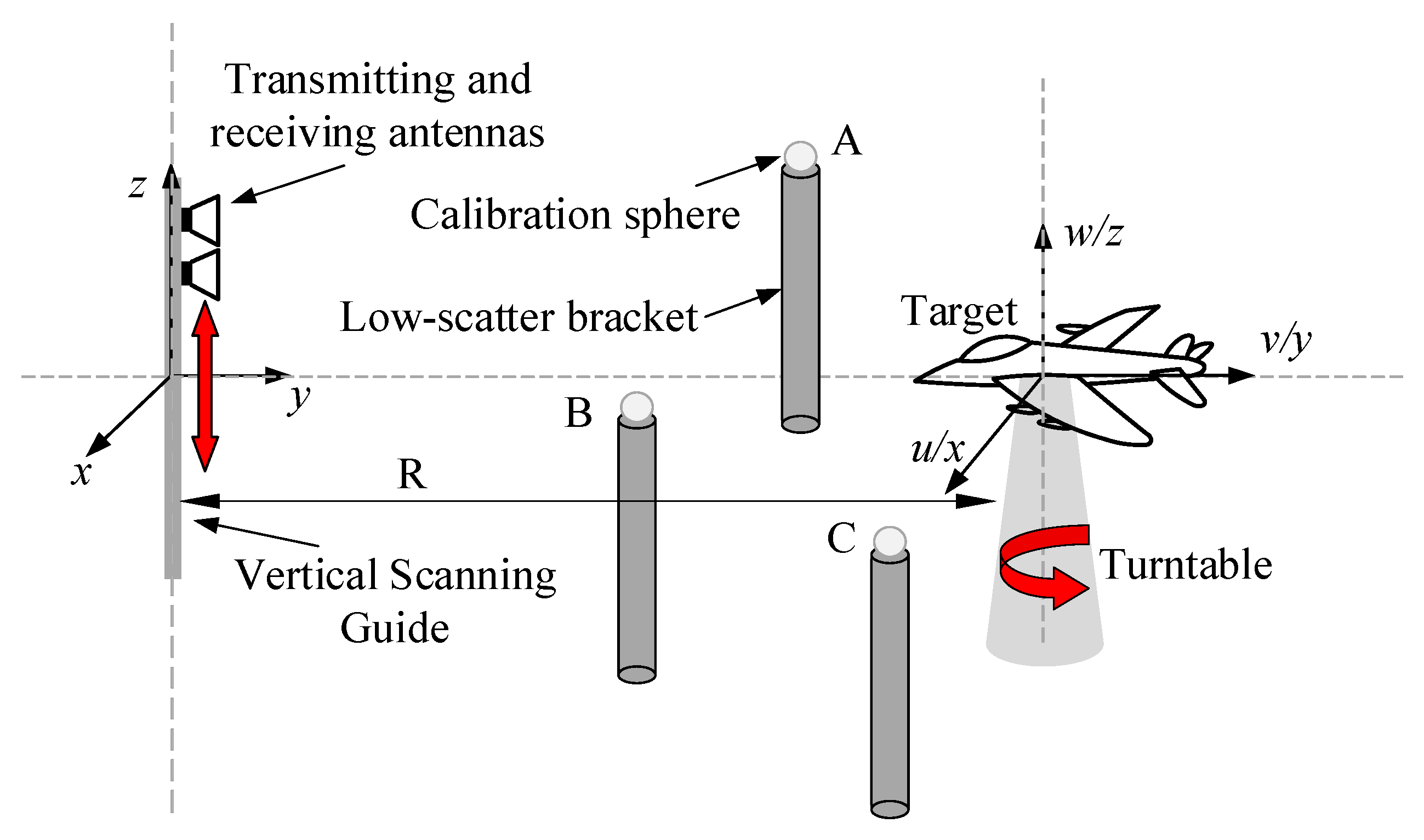

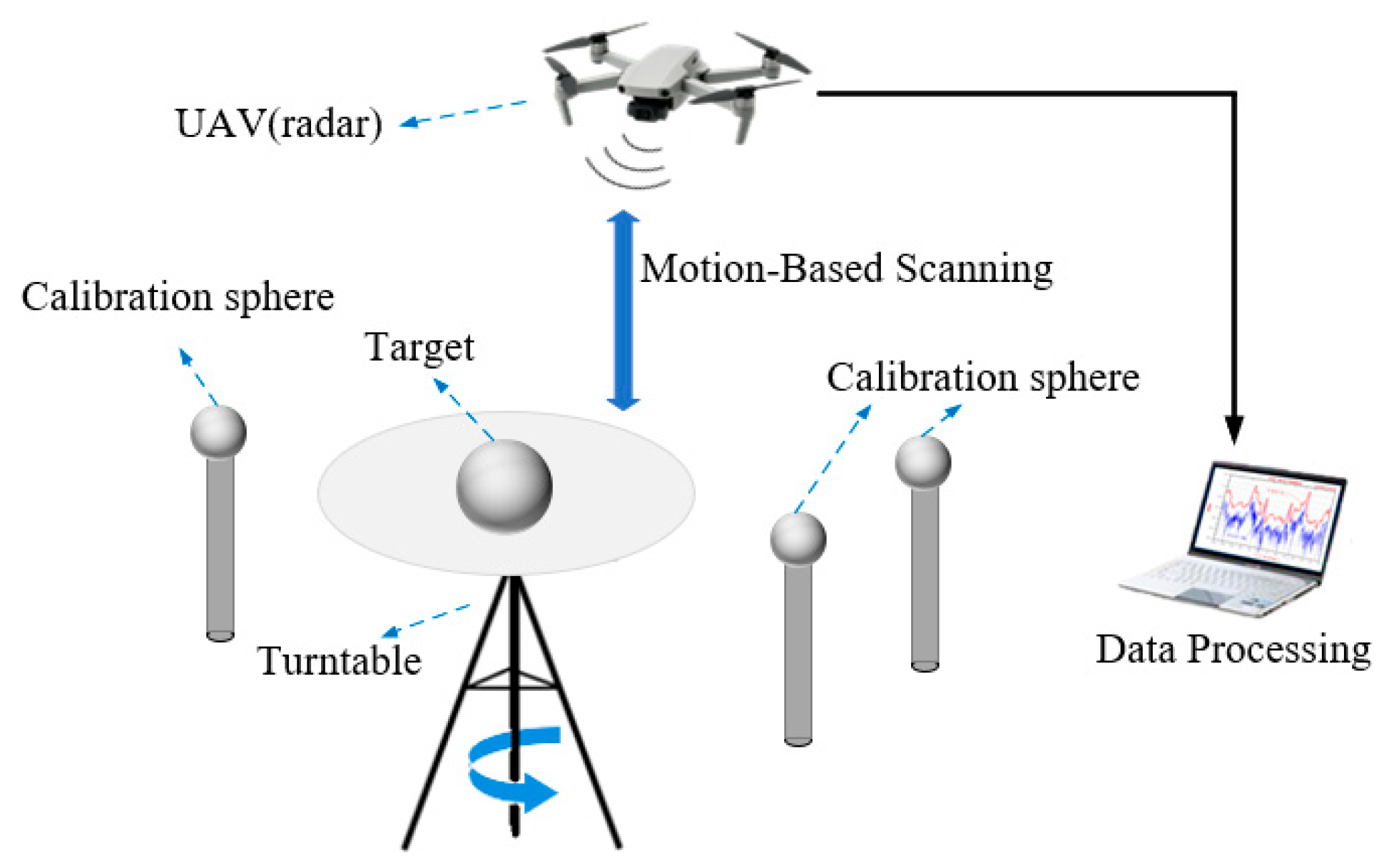

Based on the three-point localization principle, a measurement model for sparse 3D imaging can be established. Taking the synchronized scanning–rotation sampling scheme as an example, three low-scattering support rods of different heights are placed outside the target region, each mounting a metallic positioning sphere of potentially varying size. The corresponding scattering measurement model is illustrated in

Figure 4. In this setup, the target is mounted on a turntable and rotates about the vertical axis, while the Tx/Rx antenna performs a vertical scanning motion along a linear rail. This allows the system to collect backscattered data from multiple azimuths and heights, forming a composite dataset for 3D imaging.

In

Figure 4, the positioning spheres are placed outside the target region and must not obstruct the line of sight to the target. The monostatic radar (Tx/Rx antenna) is mounted on a vertical linear stage to scan the target mounted on a rotary turntable. This localization method can be extended to millimeter-level, portable radar applications. Compared to solutions such as laser trackers, the microwave three-point ranging approach significantly reduces cost and system complexity without sacrificing accuracy.

2.4. Three-Dimensional Imaging Parameters

In the imaging model, the rotation of the target on the turntable is equivalently transformed into the motion of the antenna rotating around a stationary target, as shown in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2. During this process, the antenna simultaneously performs vertical scanning. Under this equivalent configuration, the distance variation

d between the antenna and the target can be expressed as:

The transceiver antenna performs stepped vertical scanning along the vertical rail (denoted as

). At each scanning position, the antenna transmits stepped-frequency electromagnetic waves

. Assuming the target is located at position

, the reflected signal undergoes a phase delay

, where

represents the distance between the antenna and the target,

, and

c is the speed of light. If the scattering coefficient of the target is

, the received signal at each scanning position on the vertical axis can be expressed as:

Based on the received electromagnetic echo signal

and the theory of electromagnetic wave propagation, the target’s scattering coefficient

can be determined accordingly.

In the measurement process, the echo signal

is directly acquired by the receiving antenna. According to Equation (20), once the distance variation

d between the antenna and the target is known, phase compensation can be applied using Equation (22) to retrieve the scattering coefficient of the radar target. This imaging algorithm serves to validate the effectiveness of the proposed localization-based measurement model for 3D reconstruction. To ensure consistent spatial resolution in the reconstructed image, namely:

where

,

and

denote the spatial resolutions along the

x-,

y-, and

z-axes, respectively. The following condition must be satisfied [

5]:

where

is the center wavelength of the measurement frequency,

is the angular range of the measurement,

B is the system’s frequency bandwidth,

is the length of the scanning rail, and

is the vertical distance from the rail to the target origin. In addition, the sampling interval determines the extent of the imaging region

.

where

is the frequency-domain sampling interval,

denotes the angular sampling interval, and

represents the vertical scanning interval. At this point, the parameter settings for 3D imaging can be determined using Equations (24) and (25).

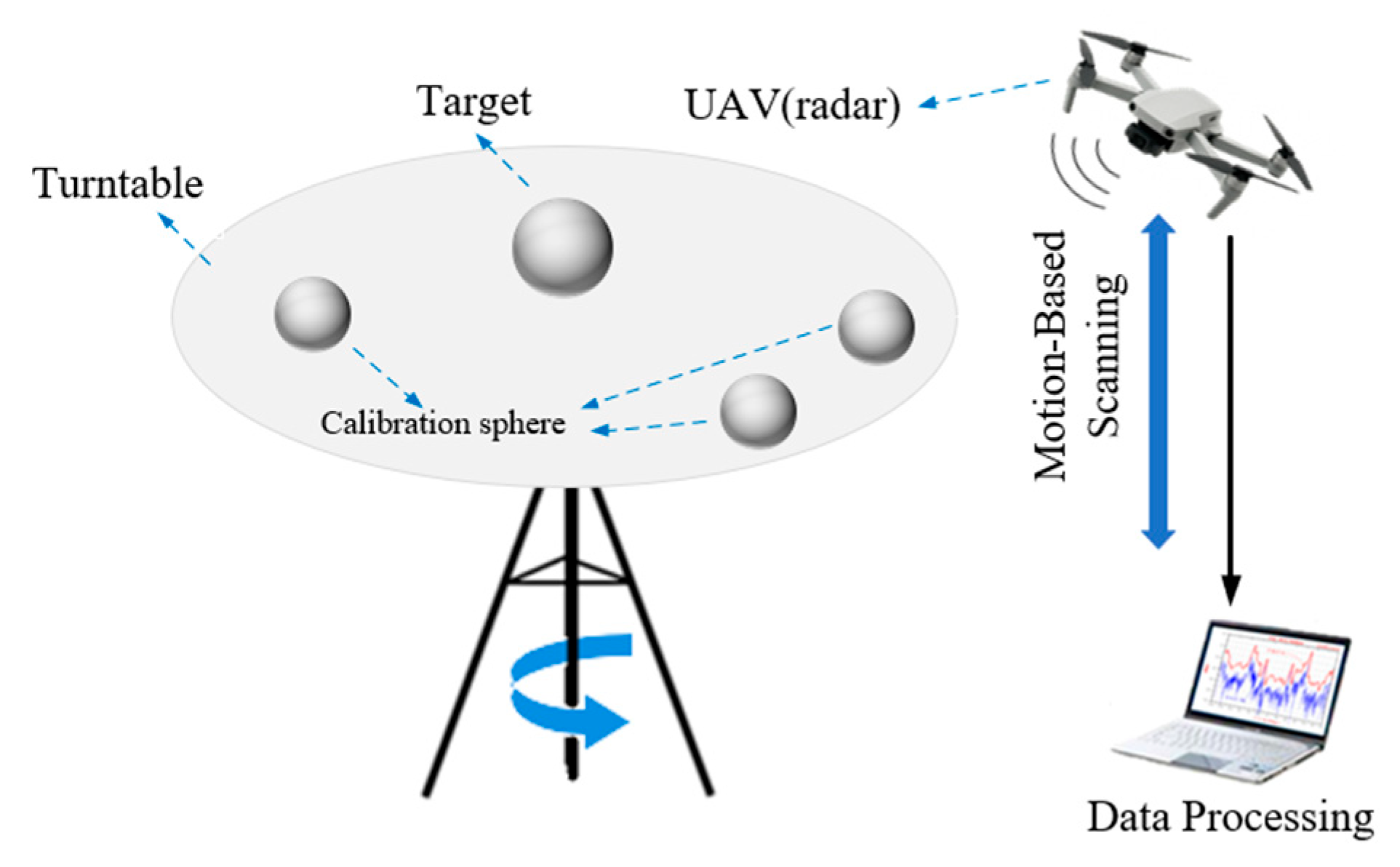

3. Validation Setup

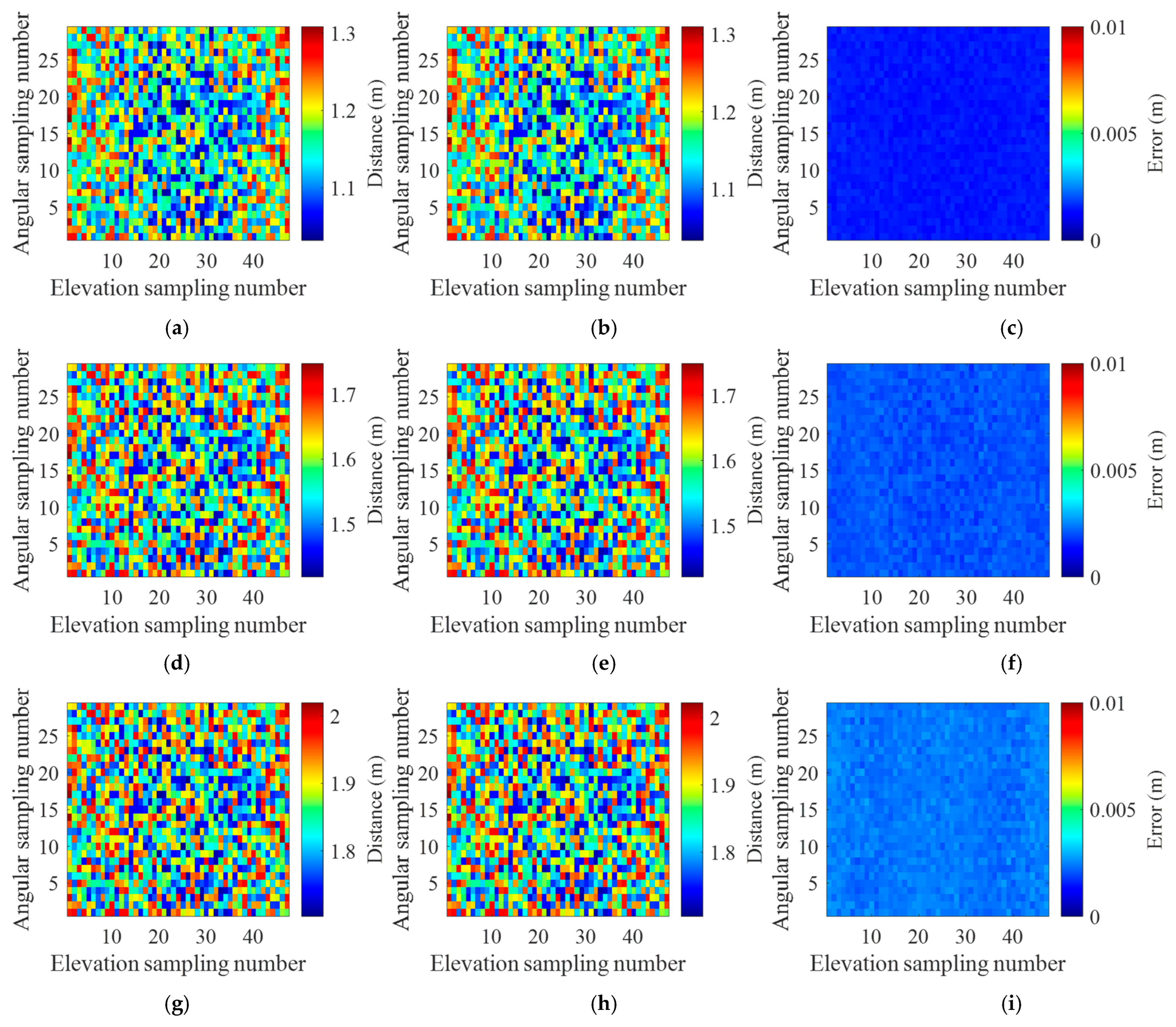

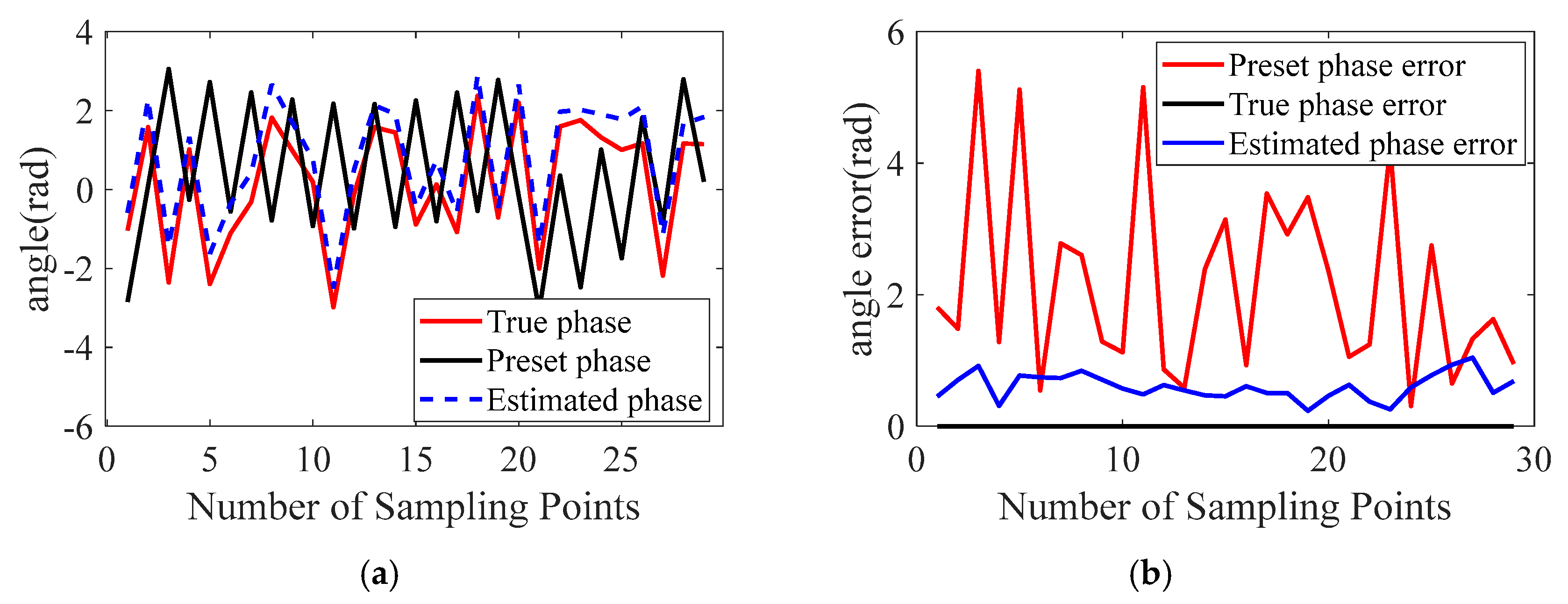

Figure 5 illustrates the schematic diagram of the system used for validation. The system consists of a UAV equipped with an onboard radar system, a turntable, three calibration spheres, and a computer processor. The UAV-borne radar is integrated within the airframe and performs electromagnetic transmission and reception (Tx/Rx). The program was executed in FEKO 2021 on a computer equipped with an Intel Core i7-13790F (2.10 GHz) processor and 32 GB RAM. CPU-based parallel acceleration was employed. In the FEKO electromagnetic simulation, an ideal point source is used as the transmitting source, and near-field reception is employed. The test target is positioned at the center of the turntable, while three reference spheres are placed away from the target area on the turntable to avoid blocking or interfering with the target’s scattering. To achieve cylindrical synthetic aperture measurement, the positions of the antennas and the turntable are continuously adjusted. In conventional cylindrical synthetic aperture configurations, the transmit–receive antenna pair performs vertical scanning at each angular step until the full azimuthal rotation is completed. In contrast, the “V”-shaped synthetic aperture configuration synchronizes the scanning of the transmit–receive antenna pair with the rotation of the target, both proceeding at constant speeds until the entire azimuthal coverage is achieved.

During the FEKO simulation for validating the proposed three-point localization theory, the first step involves positioning the target at the center of the coordinate origin (0, 0, 0). Based on the target’s size, three metallic reference spheres are placed outside the target region. In the example used in this study, three spheres with a radius of 0.1 m are located at (0.3, −0.7, 0), (0.54, 0.54, 0), and (1.2, 0.8, 0), respectively. In the second step, an electric dipole source with random position jitter is defined, along with near-field reception at jittered positions. A monostatic reception configuration is employed. The third step configures the physical optics (PO) method to compute the scattered fields. In the fourth step, the collected electric field data are processed using the three-point localization algorithm to reconstruct the 3D image of the target.

The choice of parameters in the 3D imaging process significantly affects the final image quality. This study adopts cylindrical-scanning-based measurement parameters (as listed in

Table 1) to ensure image integrity and achieve approximately uniform spatial resolution in lateral, longitudinal, and vertical directions. The spatial resolution is 0.0375 m, and the imaging volume is defined as 1 m × 1 m × 1 m.

The proposed three-point localization method requires a sufficiently precise one-dimensional (1D) range profile to identify the ranges of the auxiliary calibration spheres. Therefore, a wide measurement bandwidth is necessary (16 GHz in

Table 1). After extracting the sphere ranges and solving the three-point localization, only the central 4-GHz sub-band (8–12 GHz) is used for three-dimensional (3D) imaging. This strategy enables both accurate localization and high-fidelity 3D reconstruction. Additionally, the proposed three-point-based localization method is applicable to both conventional cylindrical sampling and advanced sparse sampling schemes. The sampling strategy does not affect the underlying localization theory presented in this study. Therefore, to enable a quantitative comparison of localization performance, cylindrical sampling is used as an example, and random positional jitter introduced during the sampling process is evaluated.

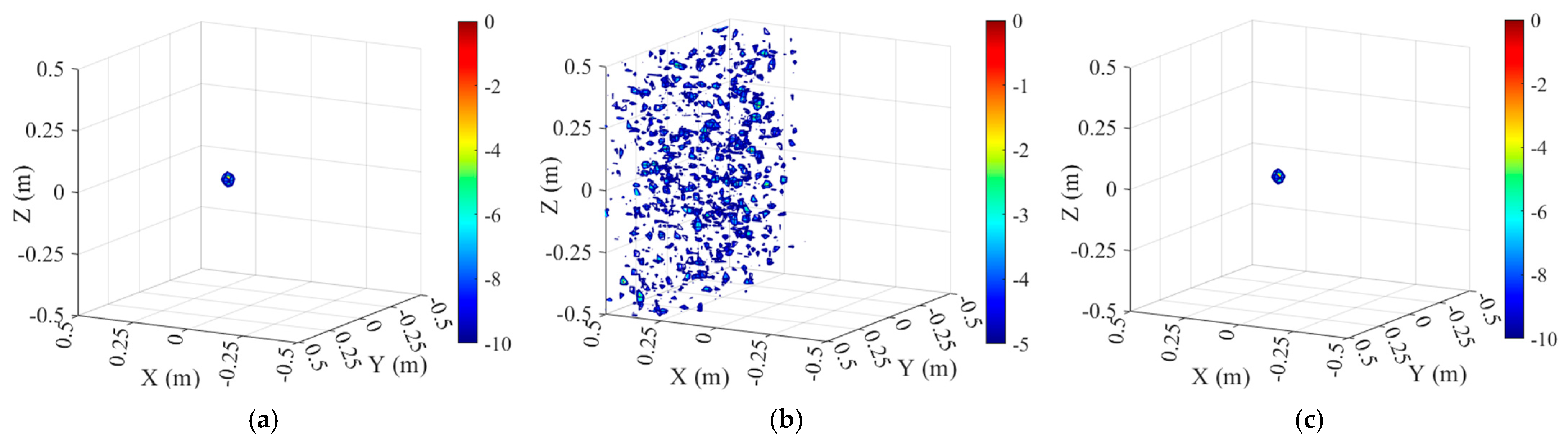

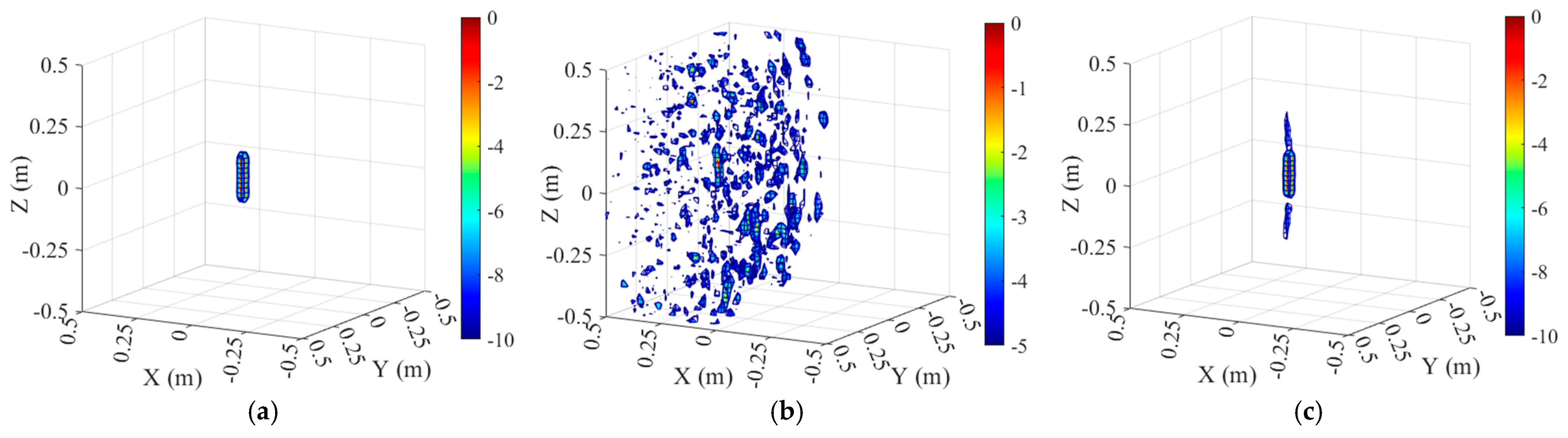

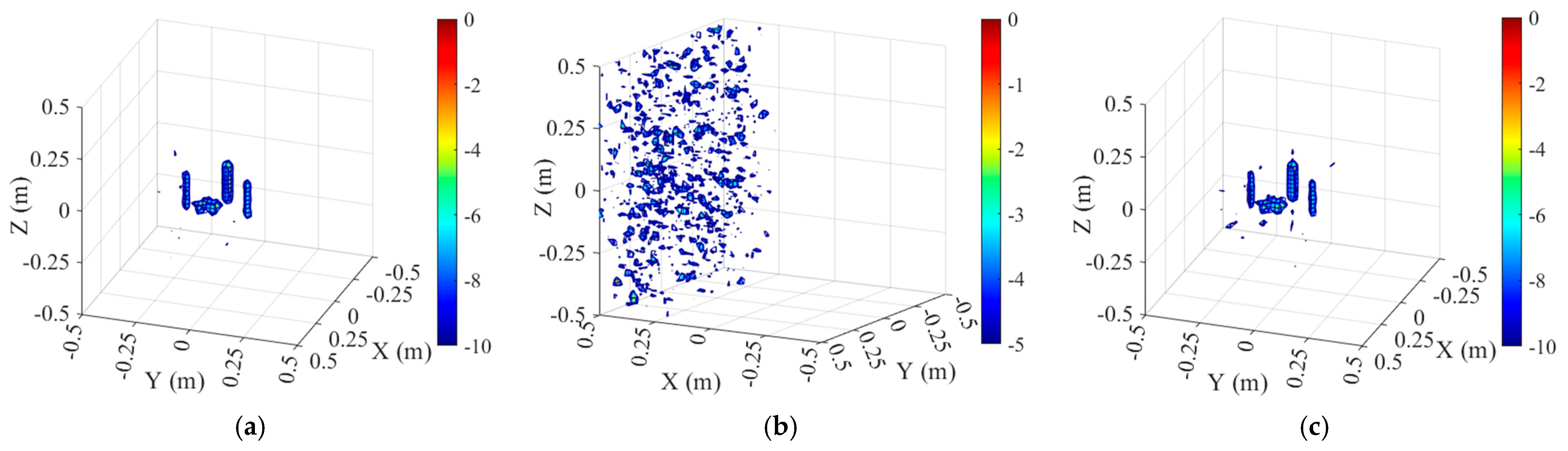

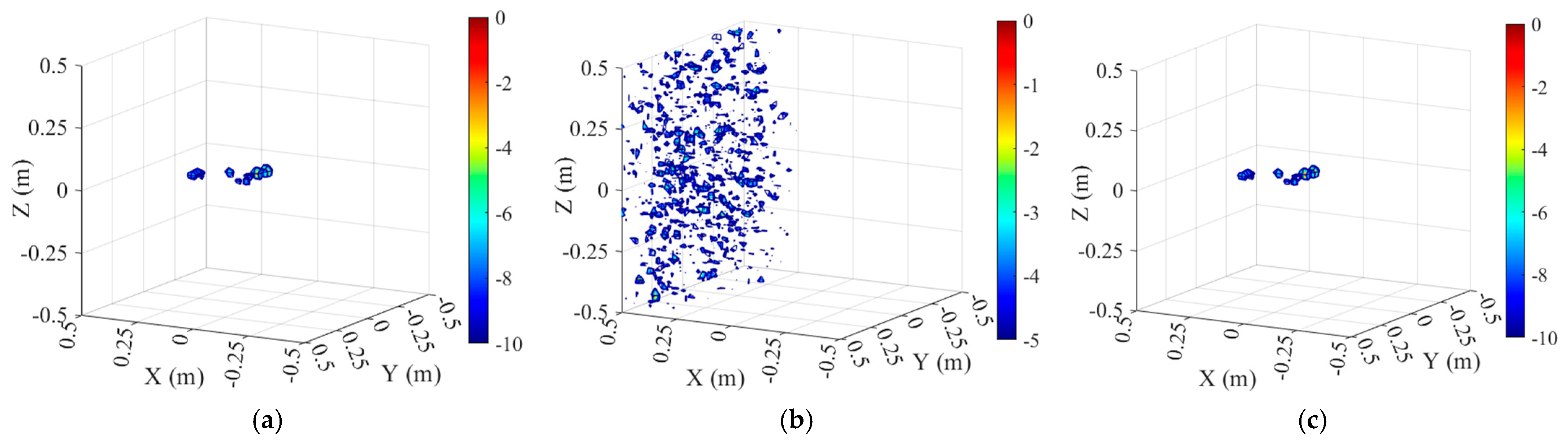

To further validate the effectiveness of the proposed trajectory-based localization method, four test targets with distinct scattering mechanisms are selected. First, a metallic sphere with a simple curved surface is used to verify the method under basic scattering conditions. Next, a cylindrical model is employed to represent a curved surface structure with linear scattering characteristics. Then, a dihedral model is adopted to simulate a planar structure exhibiting both specular and multiple scattering. Finally, a complex UAV model is selected to assess the method’s applicability under intricate scattering scenarios. Detailed information on the four targets is provided in

Table 2.

Subsequently, simulations are performed for the four selected targets, followed by phase compensation to obtain their corresponding 3D images. Specifically, three types of phase compensation strategies are applied to the jittered cylindrical sampling data: (1) imaging with phase correction using the actual jitter values, (2) imaging with direct phase correction without any localization operation, and (3) imaging with phase correction based on the UAV trajectory estimated via the proposed three-point localization method.

6. Conclusions

This study proposes a novel trajectory estimation method for 3D radar imaging, focusing on precise radar localization based on microwave three-point ranging. The method operates without any communication infrastructure, relying solely on three fixed microwave-reflective calibration spheres deployed outside the imaging region. By extracting one-dimensional range profiles during the radar scanning process and utilizing the known coordinates of the calibration sphere centers, the radar’s spatial position can be uniquely determined at each sampling moment. Building on this method, its applicability is further explored in both ISAR and SAR system configurations. For each scenario, a practical and geometry-constrained layout strategy of the reference spheres is developed to ensure clear peak discrimination and accurate phase compensation. These layout guidelines provide theoretical support for future engineering implementation. Validation results demonstrate that the one-dimensional ranging error remains within approximately 2 mm, and both the trajectory estimation accuracy and phase compensation precision are sufficient to meet the requirements of high-quality 3D imaging. The proposed method exhibits strong adaptability across different imaging scenarios and offers a robust, communication-independent localization solution for synchronized scanning systems.

It is worth noting that the current validation is conducted under ideal, clutter-free conditions with canonical targets. Future work should involve systematic quantitative evaluation on large-scale, distributed, or realistic targets, especially in outdoor environments affected by clutter, multipath effects, and other environmental factors. Such field-level experiments will serve as the next stage of practical validation and are essential for demonstrating the generalizability and real-world applicability of the proposed approach.

This work contributes significantly to the advancement of 3D radar imaging by improving the robustness of sparse sampling strategies and enabling high-precision localization on both ground-based and UAV-mounted platforms. Future research will focus on extending the method’s applicability to cluttered or multipath conditions, optimizing geometric configurations under engineering constraints, and integrating the approach with AI-driven reconstruction algorithms to support real-time, high-resolution radar imaging in complex environments.