5.1.1. Spatial Distribution of Different Dimensions of Vitality

Initially, the four dimensions of vitality—economic, spatial, social, and ecological—were meticulously mapped and analyzed to discern the overarching distribution patterns of these vitalities across Wuhan.

Economic vitality, a critical dimension of urban growth, was meticulously evaluated using NTL and GDP data, segmented into five distinct levels by employing the natural breaks method (

Figure 3). This methodological approach revealed a stark contrast in Wuhan’s economic vitality, with the central urban areas showcasing robust levels of economic activity, while the suburban peripheries lag in economic engagement. Notably, the northwestern quadrant of Wuhan’s core urban zone emerges as exceptionally dynamic, hosting bustling commercial streets and versatile business centers catering to an array of local needs spanning commerce, leisure, and culture. Despite this, other central locales, although characterized by multiple business districts, display only moderate economic vitality. This is largely attributed to their limited scope and the lack of major industries or flagship corporations. In contrast, the peripheral zones of Wuhan rely heavily on traditional manufacturing and agriculture, hindered by a lack of innovation and investment in high-tech sectors, consequently impacting their economic vitality adversely. Throughout 2018 to 2019 (

Figure 3a,c), Wuhan observed a significant surge in economic vitality, particularly in zones previously identified as being vibrant. However, this upward trajectory experienced a setback between 2019 and 2020 (

Figure 3e,g), as areas once teeming with economic life began to exhibit signs of declining vitality, indicating a complex interplay of factors influencing the urban economy. According to the Local Moran’s I index, the central urban area of Wuhan exhibited a significant trend of high–high clustering and diffusion before the public health emergency. In contrast, the city’s most peripheral urban areas demonstrated low–low clustering, while the economic vitality in other regions was not statistically significant. A comparative analysis across four distinct periods reveals that while economic vitality was highly concentrated in the central urban area, smaller yet notable agglomerations also emerged in some outlying urban areas.

Remote sensing imagery and Point of Interest (POI) data lay the groundwork for evaluating Wuhan’s social vitality and were subsequently divided into five categories through the natural breaks method (

Figure 4). This methodology uncovered a robust link between social vitality and land use, illustrating how Wuhan’s complex land usage fosters a diverse array of social dynamics throughout the municipality. In 2018 (

Figure 4a), the social structure of Wuhan was largely monocentric, with the bulk of social vitality being concentrated in the western part of the central city. This scenario evolved in 2019 and 2020 (

Figure 4e,g) towards a more polycentric model, propelled by the rich variety in land uses, encompassing public services, residential communities, and business districts. The shift from a monocentric to a polycentric distribution enabled a more equitable spread of development, enhancing social vitality in various city segments. The heart of Wuhan is replete with public infrastructure, including libraries, museums, cultural venues, and administrative buildings, enriching the city’s social environment. Conversely, the outskirts display reduced social vitality, attributed to the underdeveloped nature of their land use, which is still in a phase of expansion, and the deliberate preservation of natural terrains such as agricultural land, forests, and wetlands. These areas’ social vitality is further influenced by demographic factors, economic accessibility, and the availability of social and recreational opportunities, underscoring the multifaceted determinants of social vitality in urban settings. An analysis of the spatial vitality through the Local Moran’s I index (

Figure 4b) reveals an extensive high–high cluster in Wuhan’s central city, with an anomalous low–high outlier noted along the Yangtze River. From July to December 2018 (

Figure 4b), a distinct low–low cluster was observed in the northern and southern expanses, which diminished as the city developed. Throughout the four time periods studied, social vitality distributions were marked by low–high and high–low outliers, primarily in remote urban areas. The prevalence of these outliers can be attributed to the significant areas of low-social-vitality land, predominantly used for forestry and agriculture, in these remote locations.

Spatial vitality in Wuhan was meticulously evaluated using traffic-related Points of Interest (POIs) alongside road density metrics and divided into five categories through the natural breaks method (

Figure 5). Our analysis revealed a spatial vitality average of approximately 0.03 across the various study units, with notable disparities being observed between central locales and more peripheral areas. Significantly, the zenith of spatial vitality was identified in areas adjacent to the Yangtze River, Wuhan’s vital artery, serving as essential nodes for both intracity and regional connectivity. These pivotal areas host a rich array of transport facilities, including railway and bus stations, underpinned by an extensive subway system designed to meet the city’s robust parking demand. Moreover, the central zones of Wuhan benefit from increased spatial vitality, attributed to the widespread availability of metro and bus services, thereby enhancing the city’s transportation network density. In contrast, suburban areas display markedly lower levels of spatial vitality, with occasional spikes along major thoroughfares. This discrepancy stems from the peripheral dominance of industrial and residential areas, where transportation infrastructure remains limited. A temporal analysis indicates steady spatial vitality in Wuhan’s outskirts, while central urban areas witnessed a notable increase from 2018 to 2019 (

Figure 5a,c), followed by a subsequent decline through to 2020 (

Figure 5g). This fluctuation underscores the dynamic nature of spatial vitality, influenced by urban development, transportation infrastructure enhancements, and changing public health contexts. The Local Moran’s I index results reveal that high–high clustering of the spatial vitality in Wuhan is confined to a small central area, while extensive low–low clustering occurs in peripheral regions. This pattern reflects a clear correlation with Wuhan’s subway line infrastructure. Despite substantial government investments in subway construction, full subway line coverage is limited to the central city. In contrast, remote areas typically feature only a single subway line, influencing the spatial distribution of the city’s vitality.

By analyzing NDVI and AQI data, the ecological vitality of the study area was quantified and categorized into five levels from low to high using the natural breaks method (

Figure 6). The findings indicate that ecological vitality in Wuhan predominantly oscillates between medium and weak, with a tendency towards the latter. The central urban areas of Wuhan, characterized by a scarcity of green spaces amid dense residential and commercial development, recorded ecological vitality values below 0.02 (

Figure 6a). In contrast, Wuhan’s eastern region exhibits a broader spectrum of ecological vitality due to its expansive geography and varied land usage, reflecting a more diverse ecological state. The city’s outskirts showcase a sustained medium level of ecological vitality, attributed to restrained urban development and the conservation of natural landscapes, including numerous wetland parks and lakes. These areas, with their development curtailed to protect tourism and ecological resources, exemplify the positive impact of environmental preservation on ecological vitality. Over time, the ecological vitality of these peripheral areas remains relatively stable, with some achieving consistent medium levels, while others experience variations between weak and medium. This analysis underscores the complex interplay between urban development, land use, and ecological preservation in shaping the ecological vitality of Wuhan. Utilizing the Local Moran’s I index, the results shown reveal that significant clustering is generally absent across the city, attributed to the low overall ecological vitality. In the northern and southern regions, however, the presence of wetlands and large parks correlates with relatively high ecological vitality, resulting in several high–high clusters. Conversely, the central city exhibits low–low clustering as a consequence of its saturated land use and scarcity of green spaces.

When analyzing the spatial distribution of vitality, it is observed that both the economic vitality and spatial vitality are more pronounced in the central urban zones. The economic vitality exhibits a polycentric formation, whereas the spatial vitality demonstrates a monocentric pattern. On the contrary, the distribution of social vitality lacks a discernible spatial structure, and ecological vitality is notably greater in the more remote urban regions.

5.1.2. Spatial Distribution of Comprehensive Urban Vitality

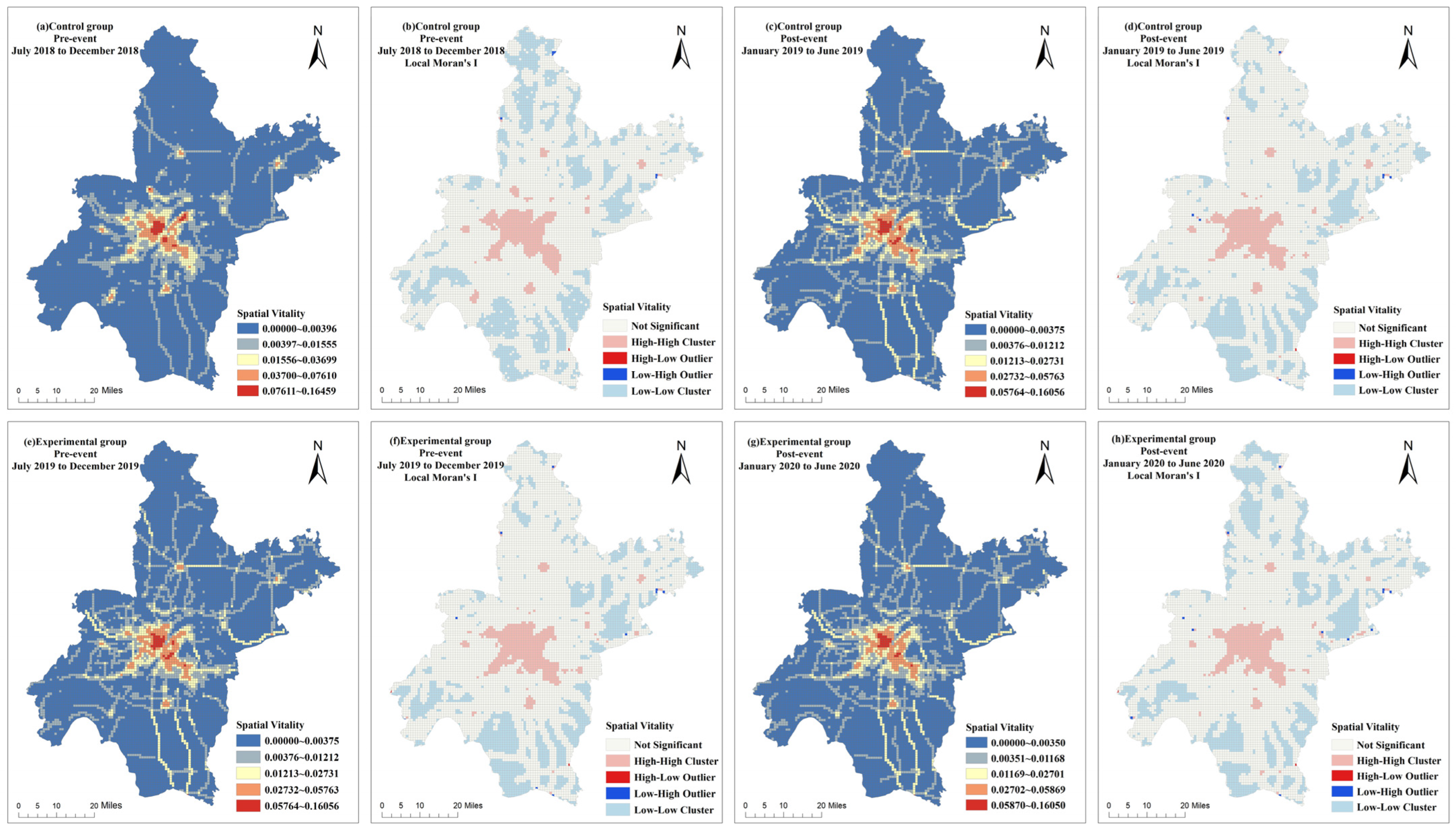

Different types of vitality in Wuhan were evaluated using the entropy weighting method, resulting in a measure of the city’s comprehensive vitality. This comprehensive vitality was then classified into five levels through the natural breaks method, producing a detailed distribution map of Wuhan’s comprehensive vitality (

Figure 7).

Wuhan’s overall vitality exhibits significant regional variation, with the most vibrant areas being concentrated in the city center and the vitality diminishing towards the city’s outskirts. This pattern mirrors the distributions of the economic and spatial vitality, which are particularly pronounced in regions adjacent to the Yangtze River. These areas enjoy elevated urban vitality, attributed to their accessible public transportation, thriving commercial zones, abundant cultural and tourist sites, and comprehensive social institutions, as well as their residents’ active participation in social activities. In contrast, while other central urban areas also boast diverse land use and a wealth of parks, shops, and residences, their urban vitality is considered medium. This is primarily due to underdeveloped economic structures and less effective urban planning. The vitality landscape of Wuhan’s outlying urban areas shows marked variability. Zones close to the central city demonstrate enhanced vitality, in contrast to peripheral regions, where urban vitality falls below 0.04. Notably, the northern and northeastern outskirts show an evolution into distinct nodes of vitality. The pattern of urban vitality in these areas parallels that of the social vitality, albeit with variance in intensity. Predominantly industrial and manufacturing in nature, these sectors struggle with challenges like scarce employment options and a lower appeal for living and working, diminishing their impact on the city’s aggregate urban vitality. On the other hand, the city’s outskirts are distinguished by robust ecological vitality, benefiting from vast undeveloped natural terrains. This is further amplified by local government efforts to foster eco-development.

An analysis of the data across the four periods with the Local Moran’s I index reveals distinct clustering patterns of comprehensive vitality within Wuhan, persisting throughout all four periods. The central city exhibits consistent high–high clustering, with both the intensity and clustering of vitality dispersing outward from 2018 to 2019. Transitional zones between the central and outlying urban areas display unique low–high outliers, attributed to stark contrasts in their urban vitality values. Conversely, the distant urban regions are characterized by a mix of non-significant and low–low clustering, alongside occasional high–high clusters. Throughout all four periods, the urban vitality in the northern and southern sectors consistently ranks the lowest, resulting in a predominance of low–low clustering compared to other areas.

Employing a 1 km × 1 km grid as the study unit enables us to visualize the urban vitality distribution, whereas utilizing administrative districts as the study unit enhances our understanding of policy impacts. Given that administrative districts are central to daily life, employment, and governance, vitality statistics at this level more precisely capture the economic, social, and cultural characteristics of different areas. Furthermore, these statistics provide insights into each district’s governmental policy decisions during the epidemic.

The average urban vitality of each administrative district was determined using an area-based weighted summation approach (

Figure 8). The three central districts on the western side of the Yangtze River maintained the highest vitality levels throughout the four periods analyzed, as illustrated in the figure. Their superior urban vitality can be attributed to rich resources and significant investments. Conversely, the outer suburban districts exhibit low urban vitality, compounded by their distance from central areas, poor connectivity, and inadequate infrastructure. These peripheral districts, being on the outskirts of Wuhan, also face a scarcity of public amenities (such as healthcare, education, and transportation) and a dearth of commercial hubs and industrial clusters, which are factors that significantly diminish their low vitality.

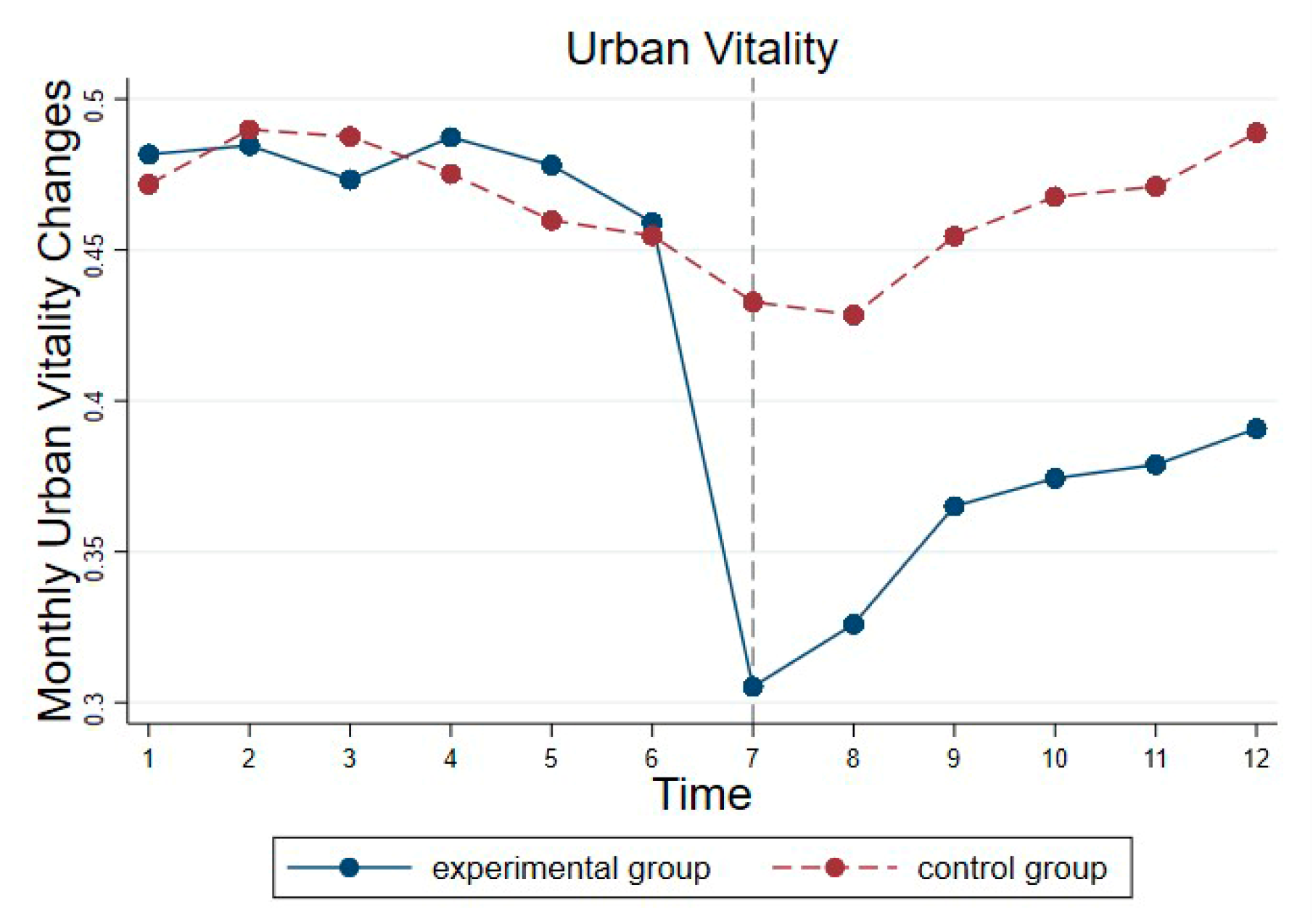

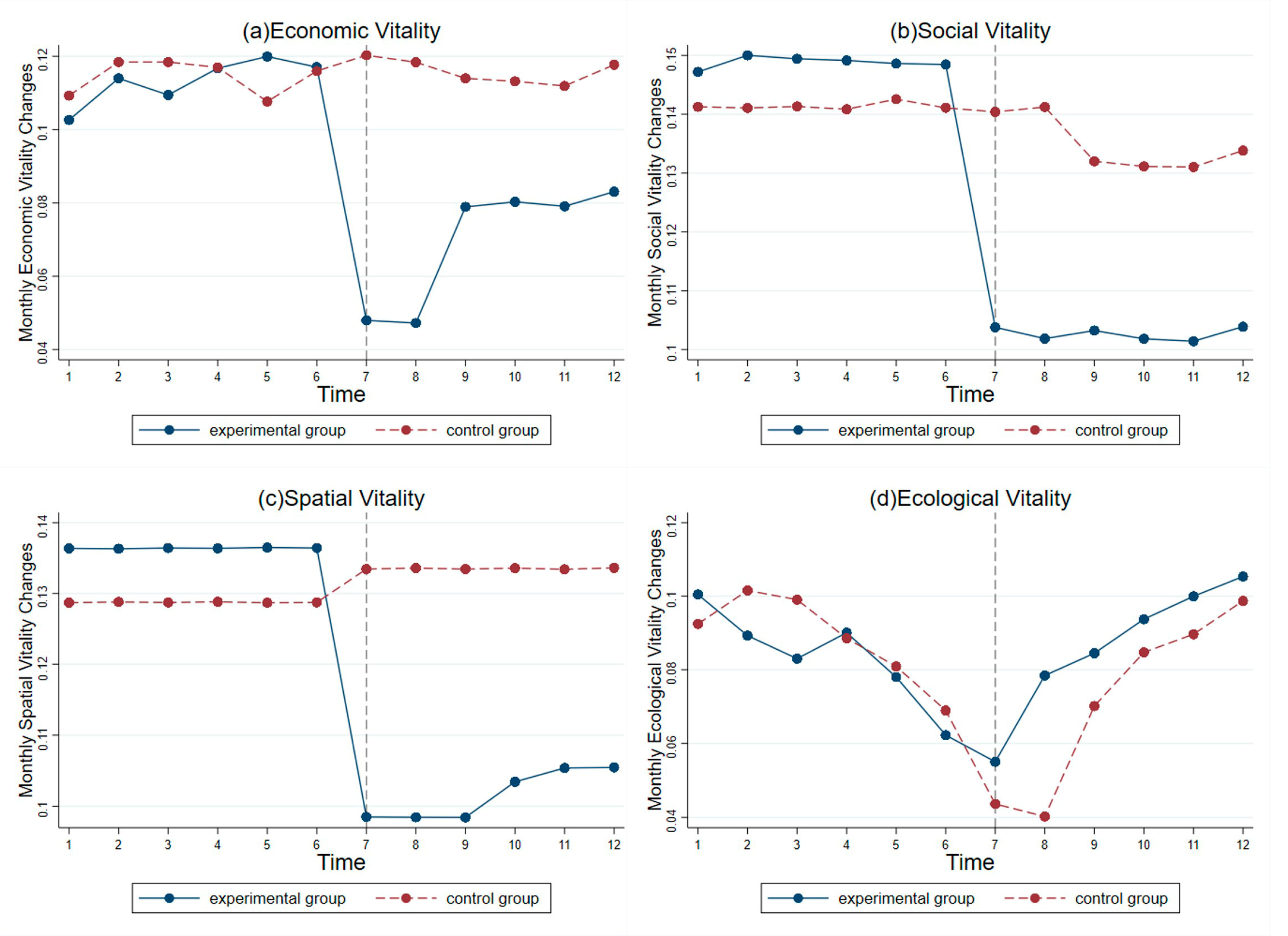

Changes in the four studied dimensions of vitality in different regions of Wuhan are shown in

Figure 9. For instance, the districts of Hannan and Jiangxia consistently show higher levels of spatial vitality compared to other forms of vitality, whereas in the districts of Qingshan and Hanyang, social vitality predominates. Assessing the impact of public health emergencies on these vitality dimensions solely through time-series analysis proves challenging. Therefore, we propose a Difference-In-Difference model for more comprehensive future studies.