1. Introduction

An expanding human population has driven increased demand for timber products, placing stress on supply and threatening the survival of native forest resources [

1,

2]. In response, the agroforestry industry has expanded to meet the growing commercial demand for a plantation product that is deemed to be sustainable and the result of responsible environmental practices [

3,

4]. In south-east Queensland, plantation trees can take up to 25 years to reach commercial maturity [

5], and consequently, large amounts of capital are invested in an agricultural industry that is slow to produce returns on investment. During this time, the crop faces a myriad of potential threats including drought, floods, pests and fire, any of which could lead to a total loss of monies invested [

6]. Therefore, responsible forest management practice needs to include strategies designed to mitigate a total loss of invested funds. With respect to fire, risk mitigation needs to be based on a detailed knowledge of the location and structure of available fuels [

7] and on an informed understanding of which components of those fuels represent the major risk, before resources tasked with reducing that risk can be effectively deployed.

The creation of fire requires three basic ingredients: a supply of suitable fuel, available oxygen and an ignition source. In an outdoor environment, the limitation of available oxygen is not feasible. Therefore, reducing the risk of a fire is limited to either eliminating the ignition source or reducing the amount of available dry fuel. Wildfire ignition sources can broadly be classified as either natural or anthropogenic [

8]. Human behaviour concerning fire is often quite unpredictable and impossible to comprehend, with many fires resulting from deliberate acts of arson [

9,

10]. Despite this, lightning remains the largest source of natural ignitions [

8,

11]. However, after researching the causes of wildfires in south-eastern Australia, Nampak et al. [

12] found that the percentage of strikes that result in an ignition event is extremely low, with an annual efficiency of only 0.24%. However, the study also concluded that low-level vegetation such as dry summer grasses and understories significantly increased the likelihood of a successful lightning ignition. This finding supports the assumption that lower-level vegetation is an important determinant of potential fire risk and further reinforces the belief that if the potential risk from a wildfire is to be mitigated, those tasked with performing the mitigation need a good understanding of the profiles of that lower-level vegetation, which, in many cases, is a forest or woodland understory.

Understanding the mechanisms of lightning and successful wildfire ignitions has been further complicated by a changing climate [

8,

13,

14]. There is evidence that global warming has driven increased lightning activity and the logical conclusion is that this will result in more wildfires [

15]. However, as weather events and atmospheric activity are outside anthropogenic control [

11], the only risk mitigation pathway available is to improve methods of limiting the spread of fire following an ignition by reducing or altering the fuels available to support that spread.

Globally, forest ecosystems and ignition sources may vary, but few fires successfully increase in size without the existence of an understory with a volume, structure and sufficiently low moisture content capable of supporting that increase [

16,

17]. As with oxygen availability and ignition sources, the fuel moisture content usually cannot be feasibly altered in forested environments and, therefore, reductions in the development of a wildfire from an ignition revolve around interventions that reduce the understory fuel volumes or alter their structures before conditions favourable to the development of a wildfire exist.

Anthropogenic behaviour has altered forest understory composition and structure [

4]. For example, land use changes in the Mediterranean have led to an increased amount of more flammable scrubby understory vegetation, increasing chances of ignition and fire intensity [

18]. The situation has been further complicated by human-induced changes in climate patterns and associated increased periods of warmer weather, limiting the time available to implement planned fuel hazard reductions, and further contributing to potential scenarios of larger, more prevalent wildfires. Evidence suggests that this is already occurring in Australia, where the number and scale of wildfires have increased due to increased amounts of drier fuel resulting from longer, hotter seasons [

19,

20,

21,

22]. Similar conditions are emerging in Asia and the Americas as extended drier and hotter summer seasons produce increased volumes of dry understory fuels [

23,

24]. Most recent studies have concluded that this trend will continue [

14,

25].

Cruz et al. [

26] concluded that high surface fuel loads were the primary factors influencing the ignition and spread of the intense 2009 Black Saturday Fires in Victoria, Australia. The surface fuels of concern were the dry understory layers comprising desiccated vegetation and remnant eucalypt litter such as bark and limbs [

27,

28]. Research by Erni et al. [

29] supported the belief that understory profiles in the Canadian and North American forests were major determinants of fire ignition and spread.

Consequently, there is an increased need for intervention to reduce the risk of intense wildfires developing from ignition events occurring during fire-favourable weather conditions by reducing the available ground-level fuels [

30,

31]. Fuel load reductions primarily using controlled hazard reduction burns have long been used as the primary method of mitigating this risk [

32,

33], but in commercial forestry, fuel load management can also be in the form of chemical or mechanical reduction [

5,

34]. Fuel reduction burns to reduce the amount of available understory fuel by burning during the cooler seasons, with the aim being to reduce understory volume and alter the understory structure without damaging the tree crowns of taller vegetation. However, in some juvenile pine plantations, the use of fire can lead to tree mortality and is therefore not appropriate. Whatever the chosen method, effective fuel hazard reduction programmes direct what are usually limited resources towards regions assessed as being at substantial risk. Unless the ignition source of a forest fire is a fully developed crowning fire spreading from an adjacent forested environment, the initial ignition site and, consequently, the area of highest risk is likely to be in regions with dense understory vegetation, which becomes highly flammable as it dries [

31]. Therefore, the effective implementation of hazard reduction requires a detailed assessment and a good understanding of that understory if effective measures are to be implemented to limit the likelihood of a successful ignition and subsequent spread [

35]. At present, the assessment of sometimes large regions to determine potential high-risk locations within is largely based on field observations, which are both time-consuming and expensive. The reality of large capital losses due to increases in wildfire intensity and frequency has provided the impetus to improving forest management practices aimed at limiting the potential losses from destructive events.

Research projects have examined alternative methods that remotely sense forest structures. However, most of the early studies utilised data from satellite imagery, high-resolution aerial photographs or LiDAR, obtained using rotary or fixed-wing aircraft, to produce profiles of forest environments [

7,

36,

37]. These methods were able to cover large areas, but were expensive to implement and the limited resolution of satellite imagery made the definition of smaller trees difficult [

37,

38,

39]. The methodologies mainly concentrated on quantitative assessment of potential commercial timber inventories using Individual Tree Crown Detection and Delineation (ITCD) techniques [

37,

38].

The finer-scale analysis of forest environments has been enhanced by recent developments in unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) photogrammetry and LiDAR, leading to the availability of more cost-effective options for forest structure profiling [

37]. The higher resolution data, when compared to that of satellites, has enabled improved assessment of areas composed of smaller trees. Again, most of the initial studies concentrated on the quantification of commercial products contained beneath the forest canopy [

37,

38,

39]. Despite extensive literature reviews conducted by the authors, it appears that to date, little work has been carried out using these techniques to determine what constitutes other forest layers such as the qualification and quantification of understory profiles as part of overall fuel hazard management planning.

Improvements in UAVs, the associated data sensing equipment payload and the computer software capable of analysing the resultant data have enabled some studies to extend profiling to include the complete forest environment. More recently, with an increased realisation of the fire risk associated with the forest floor and understory, there has been an emerging emphasis on the use of remote sensing technologies to profile the lower levels of forests [

40,

41].

The adaptation of remote sensing to improve efficiencies in fuel hazard management has potential benefits for not only the natural environment, but also agricultural operations, where loss due to fire has major financial implications [

42]. This is especially relevant in (but not limited to) Australia, a country with a history of destructive wildfires that are likely to become more severe as climate change progresses. Of particular concern to this study is the growing potentially negative impacts on agricultural operations, particularly silviculture.

Research projects have attempted to find more economically viable methods to implement fire management protocols in forest environments around the world [

43,

44,

45]. Many of those projects have investigated the use of UAV-supported remote sensing techniques [

37,

46]. Despite this research, the commercial pine industry has persisted in reliance on field observations to assess potential fire risks and to direct treatments. These methods are labour-intensive and therefore expensive [

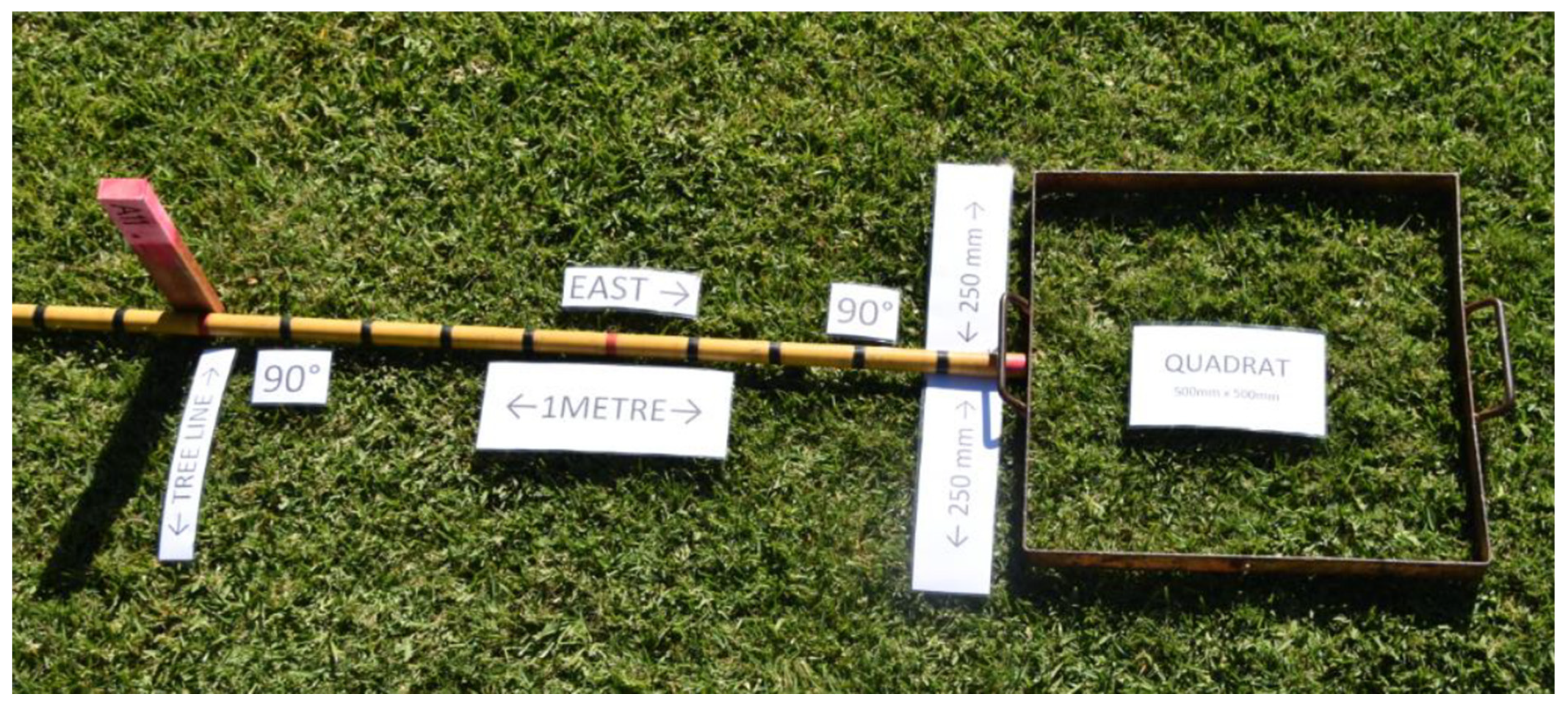

47]. This study aimed to investigate the use of drone-derived data using photogrammetry to determine the amount, composition and structure of understory fuels that could potentially improve efficiencies in fuel hazard management in the commercial pine plantations of south-eastern Queensland.

4. Discussion

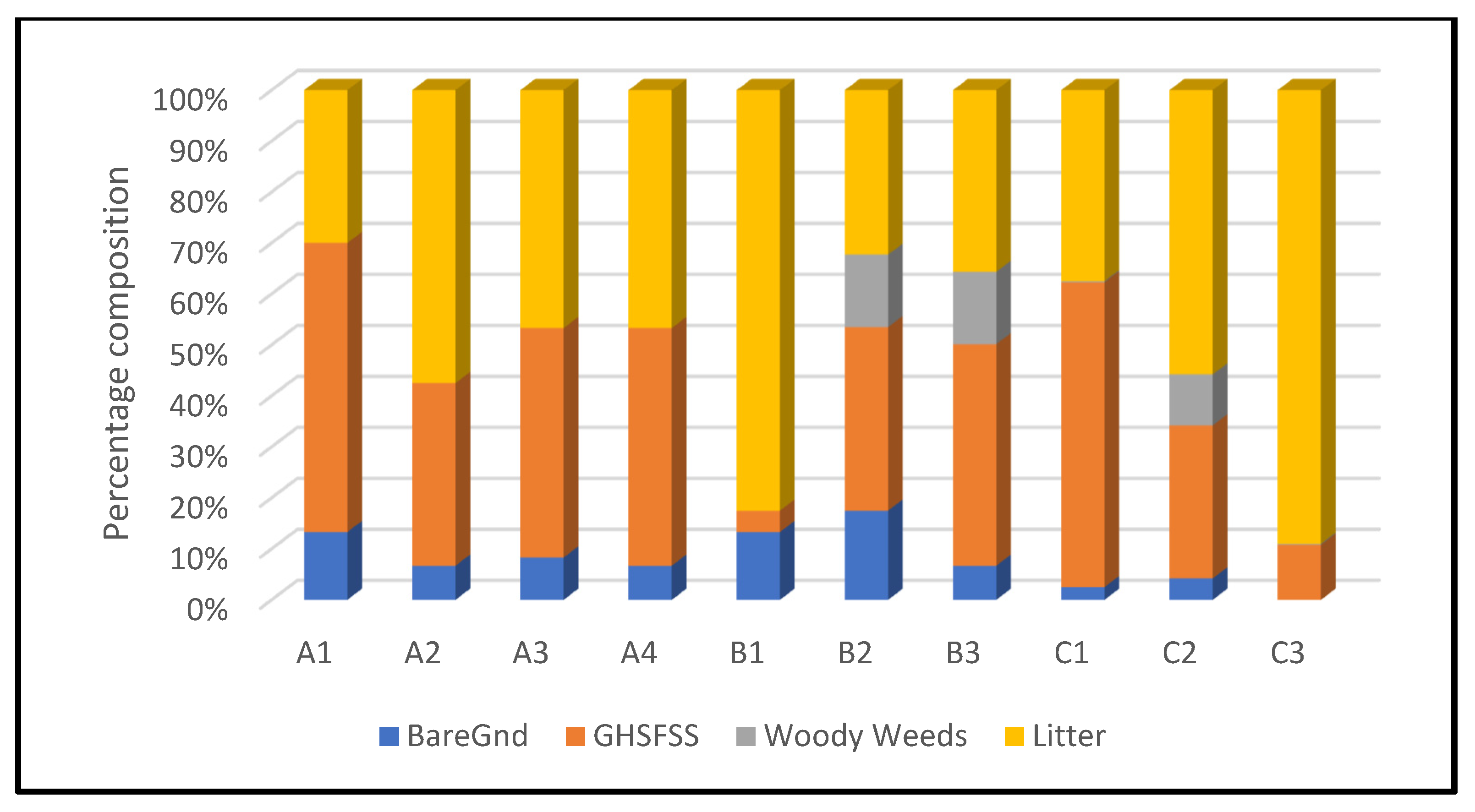

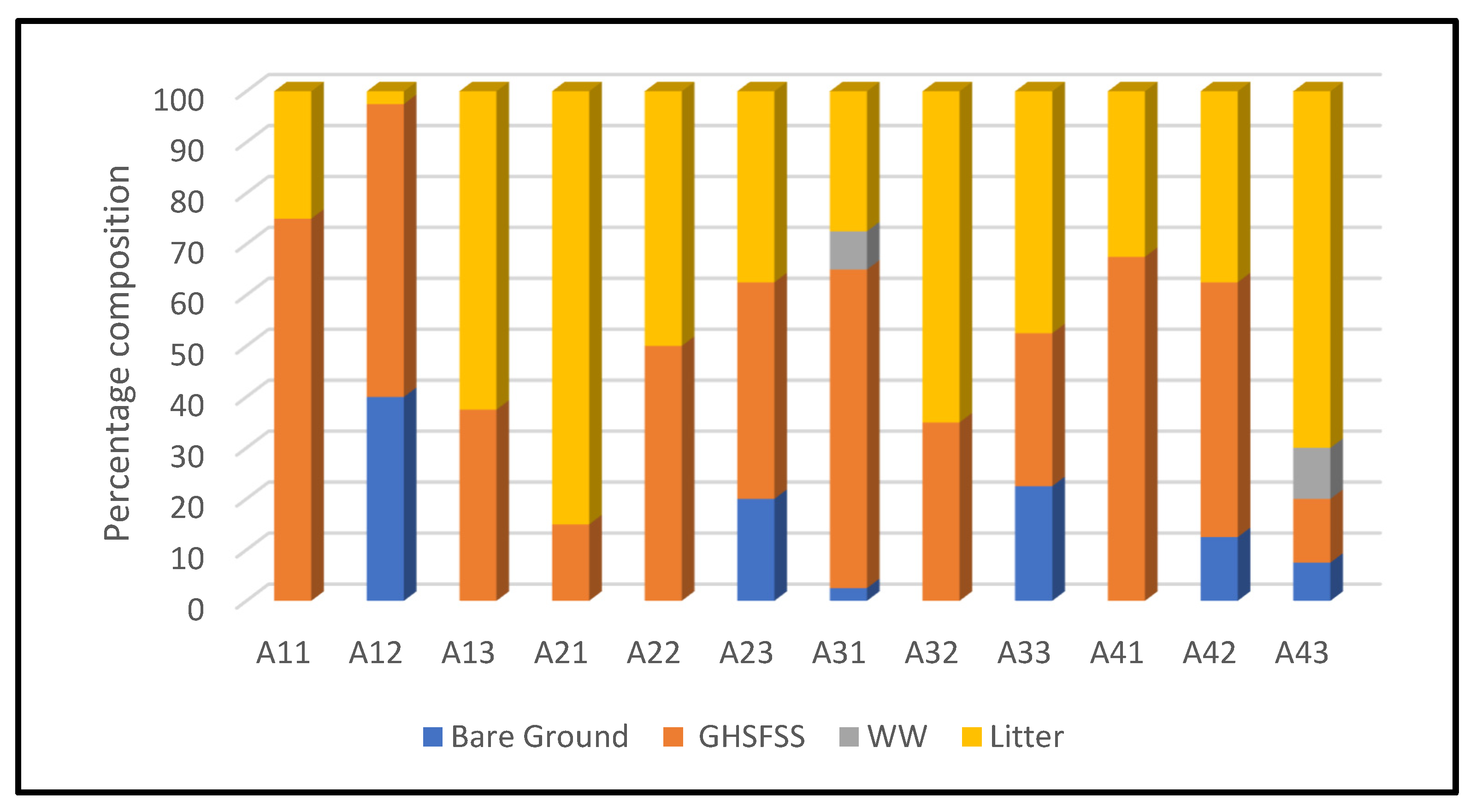

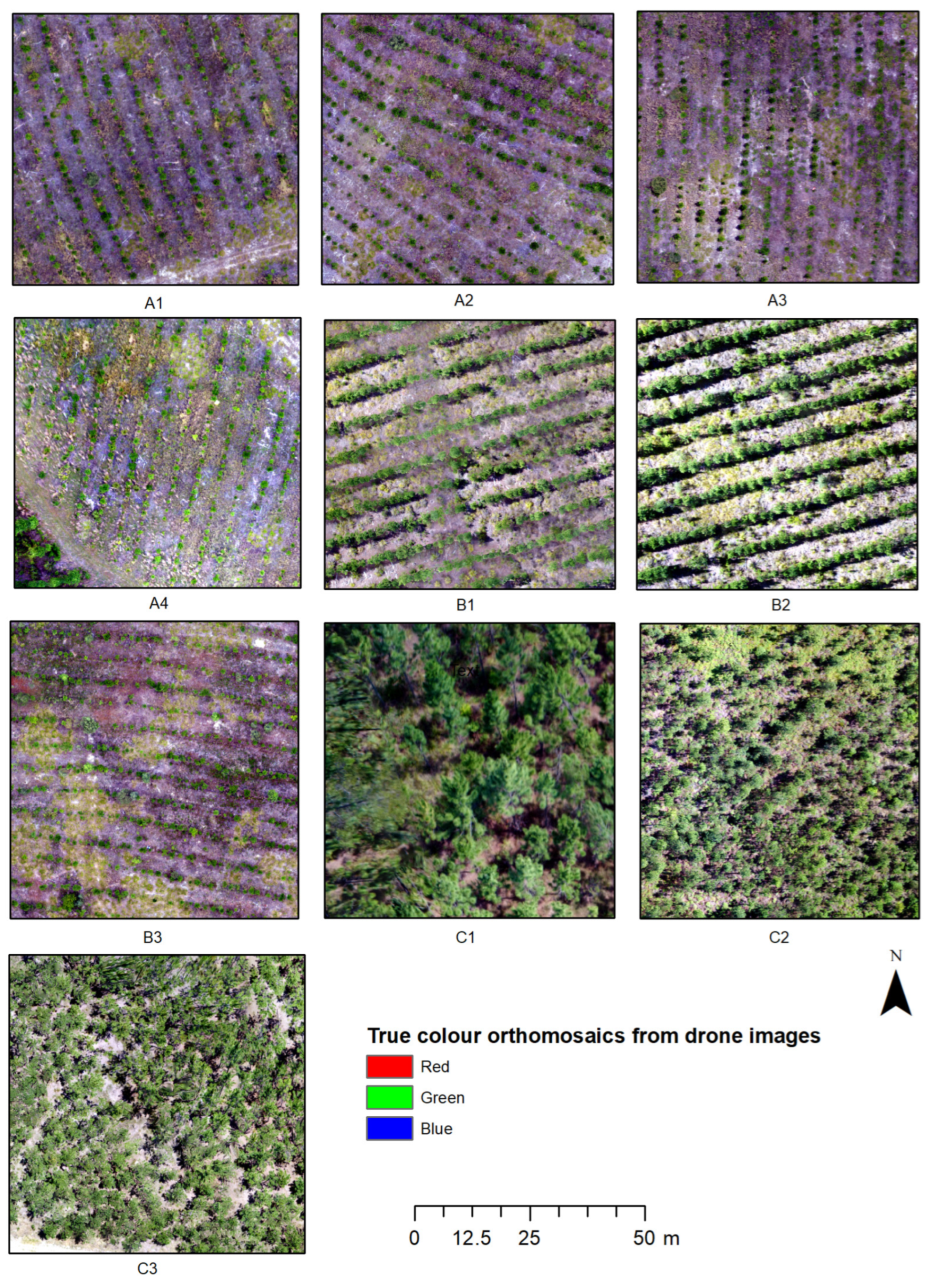

This study successfully used drone-derived data to determine the amount, composition and structure of understory fuels that could potentially improve efficiencies in fuel hazard management forests. The goal was to develop a workflow that is efficient, cost-effective and of sufficient accuracy to safely direct fuel management protocols within the juvenile forest environment. The investigation concluded that the use of remotely sensed data to quantify understories was possible using the application of MCWS algorithms to identify and eliminate taller vegetation in the digital models, and with some further refinement, this method could become an alternative to the less efficient practices currently employed. The use of the supervised classification of orthomosaics successfully provided information about understory vegetation composition with a level of detail suitable for potential fuel hazard determination.

However, while the results were encouraging, certain aspects of this study indicate that further investigation and refinement would be required before this approach could become a viable commercial reality. The method showed very promising results for younger plantations where the understory was not obscured by canopy closure. This finding was consistent with many other remote sensing forest profiling studies where the results using photogrammetry were good in open forest environments, but became less accurate compared to LiDAR-based studies as forests aged [

47,

51,

52].

In general, the use of MCWS to mask the commercial plantation trees for the subsequent modelling for average understory height calculations produced reliable results for less mature plantations—those 1–3 YOA and for some compartments 3–7 YOA. However, the outcomes for A4, B2 and B3 were exceptions. Despite the numerical variation in some more mature compartments, the trends were mostly consistent and statistically, the results were significant.

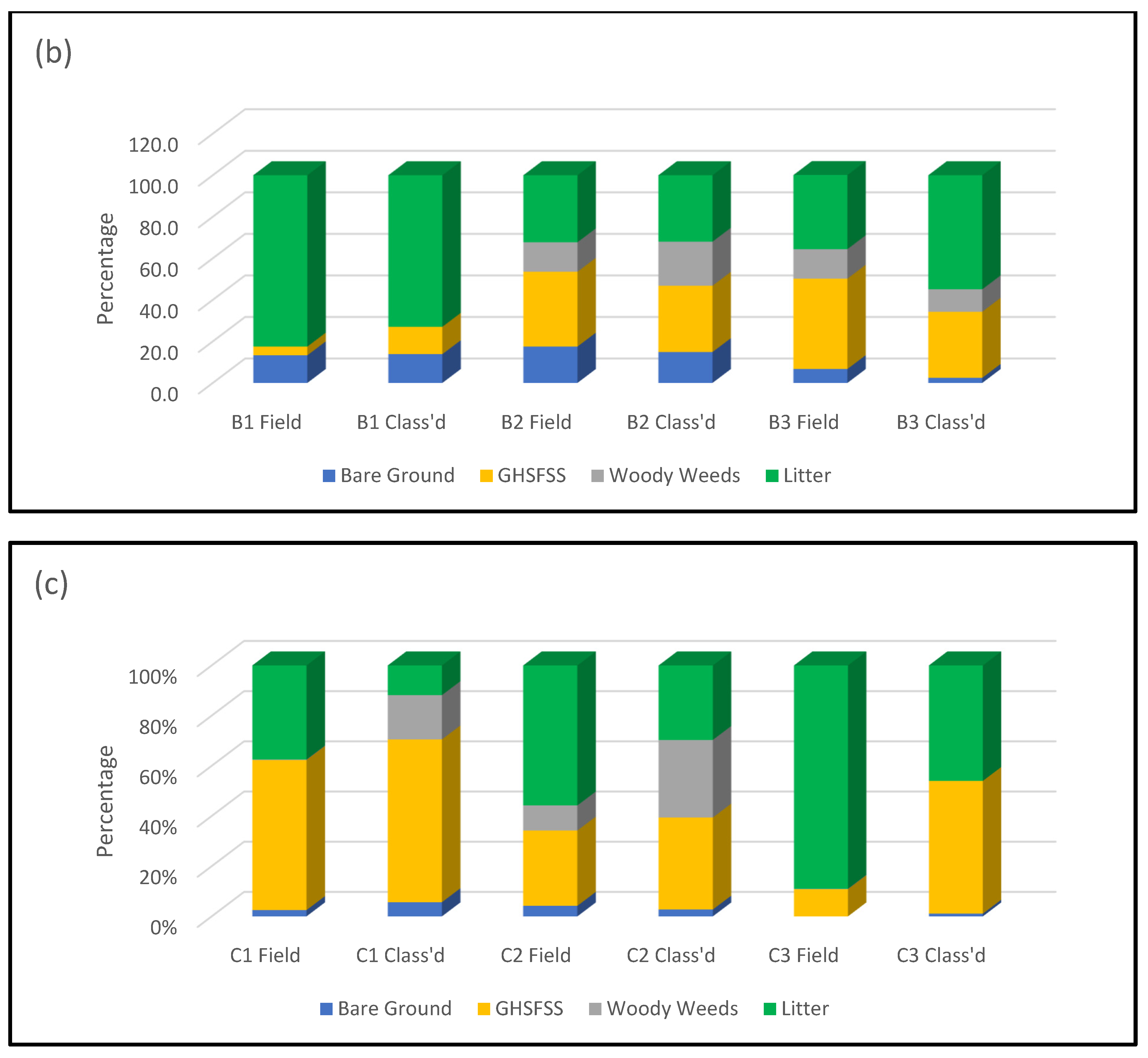

The classification results showed a similar pattern, with mostly good correlations in younger plantations and less agreement in those that were more mature, as canopy closure advanced limiting the detail of the aerial imagery. The statistical significance for the ‘A’ and ‘B’ compartments suggests a 99% chance that the results were correct and the correlations between the field and classified values were strong. The gap between the actual understory composition and the classified model widened with the ‘C’ compartments, where the results showed weaker agreement. As with the height calculations, this trend was probably due to a decrease in the percentage of visible understory within compartments as the amount of canopy closure increased.

The degree of error was potentially magnified in the more mature compartments as the classified composition model became increasingly based on smaller areas of visible vegetation, further contributing to a general deterioration in the results in older compartments. This explained the reasonably strong association between the two sets of average height values in the A compartments and B1, and the lessening of correlations in compartments B2, B3 and all C compartments where plantation maturity and increased canopy closure influenced the agreement between the field values and the analytical results. In these older compartments, the models produced were based on the limited areas within a compartment where the imagery included the understory. Our methods then expanded those findings to cover the invisible areas under the canopy, based on the assumption that the vegetation under the canopy layer had the same characteristics. Factors such as altered pH, shading and ground wetness may have affected the nature of the under-canopy vegetation [

53] and the modelling assuming continuity may be flawed. The problems profiling understory in forests with advanced canopy closure might be overcome with the use of aerial LiDAR together with RGB cameras. Ongoing improvements in drone and LiDAR technologies are likely to make this a viable future alternative, but at the current level of development, drone-based systems capable of the necessary endurance whilst supporting a payload of both LiDAR equipment and an RGB camera is a more expensive option [

54,

55].

Successful height analysis using the remotely sensed data was hindered by the difficulty of establishing an effective ground zero. The drone was flown at 60 m above the ground height at the take-off/landing point. An idiosyncrasy of DJI Phantom 4 drones was that this did not necessarily mean that the image EXIF values relating to the altitude at which an image was taken corresponded to that value. Other studies using the same equipment have experienced similar problems [

56]. The range variation in ground level altitude across all of the compartments was less than 4 m, whilst the range in EXIF values for the images obtained from the field flights was approximately 41.1 m (28.2 m (C2)–69.3 m (B2)). GNSS ‘georeferencing’ would usually be the method of choice used to correct these inconsistencies, but for the reasons previously alluded to, this study aimed to find methodologies that did not utilise this technique. Many alternative methods were trialled, and some did produce results. The reporting of those results was outside the scope of this study, but the researchers wondered whether some of those methods discarded due to lower correlations may have shown more promise if compared to the results emanating from a study with more field sampling.

A repetition of this study with an increased number of field data sampling sites per compartment would also influence correlation probabilities. The low number of samples affected the results in two ways. Firstly, it potentially altered the statistical analysis, elevating the critical values required for the results to have statistical significance. In several compartments, a favourable Pearson’s correlation coefficient was not supported by a correspondingly favourable statistical significance value. Secondly, it is possible that the field sampling was not extensive enough to reflect the true height or composition profiles of the compartments. The field observations indicated that large variations existed within compartments and between compartments of the same age grouping. Establishing understory average heights and composition within compartments using only six field samples was probably not an effective method of establishing an average height or composition profile reflective of that compartment, especially with respect to compartments with advanced canopy closure where the composition and structure of the understory became more complicated. An interesting result is that of compartment C3; this compartment had, at some time, been subjected to fire, possibly a fuel hazard reduction burn and the understory consisted of a small amount of remnant pine debris, some regenerated sedges and a continuous layer of pine needle litter approximately 100 mm in depth. The DSM(Un) resulted from MCWS application to a CHM derived using a DEM interpolated from ground points that may have potentially been the surface of the litter layer as captured in the drone imagery of compartment C3. Adjustment for this possible error would have significantly improved the results for the modelled average heights in this compartment. Similar potential error scenarios may have existed in other B and C compartments where shadowing and difficulties in the differentiation between the colour of bare ground and ground litter increased, complicating the determination of the true nature of the surface selected as a ground point. As before, point clouds produced from the analysis of aerial-derived LiDAR data would improve the results by minimising these errors.

The potential for the use of MCWS in the natural environment is only just being realised. As previously mentioned, it improves the delineation or outline of features of interest, enabling more accurate quantification of that feature. Initially, its main use was the interpretation of medical imagery such as MIRs to determine the extent of tumorous lesions. For example, the technology was investigated as a method to analyse imagery of human brains by Michael [

57]. Cui et al. [

58] were able to adapt MCWS to successfully interpret cancerous lesions in medical imagery of breast tissue. However, it has the potential to assist the interpretation of any form of imagery, and since 2010, its use has expanded to other fields including agriculture and industry. Devi and Singh [

59] successfully used the algorithm to count pigs, and Heltin Genitha et al. [

60] were able to use MCWS to delineate ships detected in satellite imagery. Dahlstrom et al. [

61] adapted the use of MCWS to improve coating processes in paper manufacture. The forestry industry has recognised the benefits of applying MCWS to the delineation of individual tree canopies visible in aerial imagery [

62,

63,

64]. However, after extensive literature searches, it is the author’s conclusion that this study is the first to investigate the use of MCWS algorithms to profile forest understories. Part of the initial goal for this project was to develop simple methods of data analysis. Complicated computer pathways involving highly developed software and large capacity hardware requires increased operator specialisation and drives increased costs [

65]. In silviculture, the increased processing time from data acquisition to model availability decreases efficiency, elevates costs and possibly leads to the lack of outcome relevancy, as a forest is a constantly changing environment and opportunities may have been lost. Processing using ESRI software and subsequent MCWS application was complicated, and initial attempts involved using ArcGIS Pro to process the Agisoft Metashape DPC. Driven by a need to further understand the processes attempted and to refine those processes to improve results, the researchers reverted to using ArcGIS software, which allowed more operator input to refine the methodology. Once refined, processing could be simplified by producing workflows capable of completing the analysis more efficiently and without the need for continual analyst intervention.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates an alternative, more cost-effective method than direct field observations to determine fuel management in commercial as well as natural forest systems. Our research concluded that point cloud and orthomosaics resulting from the photogrammetric analysis of drone imagery and the subsequent derivation of canopy height models from that dense point cloud, the classification of the RGB orthomosaics and the application of MCWS on the CHMs could profile the understory vegetation within commercial pine plantations. With further refinement, the application of marker-controlled watershed segmentation to this method of understory vegetation modelling using remotely sensed UAV photographic imagery could become a very cost-effective and efficient method of understory fuel load determination, not only for use in these pine plantations, but in all forests where canopy closure does not inhibit views of most of the forest floor. However, in forests approaching levels of canopy maturity, this approach would have limited application in determining the amount of understory present, and the effective determination of that understory’s composition and structure using classification software would also be compromised.

Refinements in methodology might include further testing to fine-tune the MCWS parameters, enhancing the quality of the outcomes. Incorporating these upgrades into developed automated workflows would further improve efficiencies by reducing the amount of operator input required to complete the data analysis. Methodologies improving the ground point selection process, as part of DEM creation, would lead to improved accuracies in the calculation of the average understory vegetation heights.

Our results have been partially successful, indicating that alternative methods do exist and they do work in immature plantations. Considering that compartments of juvenile pine trees are the most susceptible to total investment loss in the event of even a mild wildfire, the method proposed and tested in this study is worthy of further consideration. The method is very cheap. It is quick and of high accuracy in immature forest plantings. The method could act as a stopgap until developments in UAV—LiDAR-RBG Camera platforms become a more commercially viable option.