Determining Peak Altitude on Maps, Books and Cartographic Materials: Multidisciplinary Implications

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Determine the errors in historical and current paper sources versus field measurements;

- Verify altitudes from DTM models obtained using ALS;

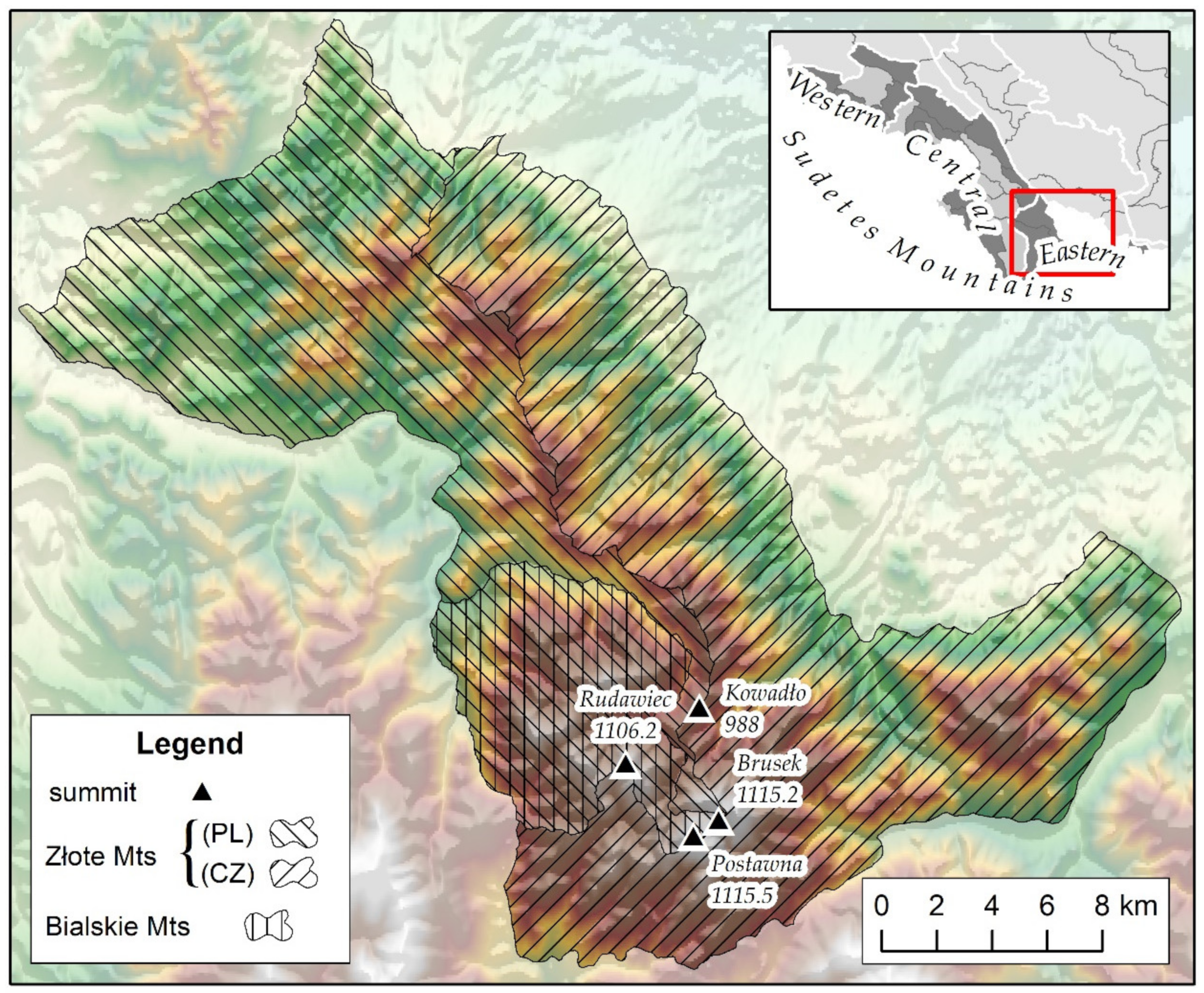

- Measure the altitude of the highest summits of selected mountain ranges and determine the highest value for mesoregions;

- Compare measurements taken with GNSS receivers in smartphones against measurements obtained with geodetic receivers;

- Critically examine the automatic seeding of spatial databases from data obtained by ALS without verification;

- Develop a methodology for conducting future verification measurements of mountain summits;

- Determine the tourism changes in:

- ○

- summit altitudes,

- ○

- the highest summit in the mountain range;

- Determine the possibility of correcting the trail to correctly identify the highest peak;

- Inspire other researchers to conduct similar studies elsewhere to obtain accurate elevation data using modern techniques.

2. Background of the Multifaceted Approach

2.1. Cartography Revisited: What Exactly Is the Altitude of This Summit?

2.2. Tourism Implications

2.3. Source Criticism

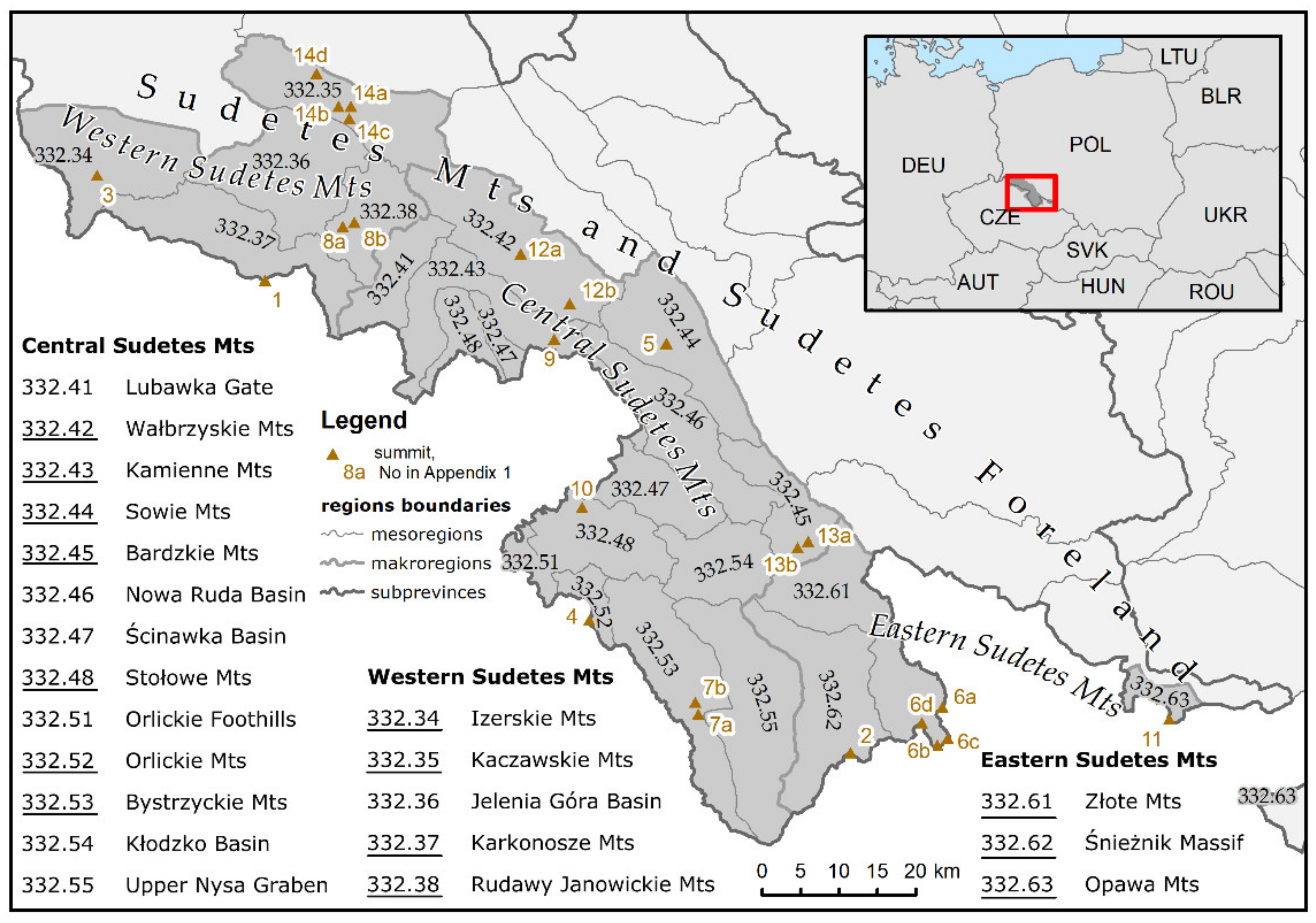

3. Sudetes Regionalisation

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Altitude Determination Methods

4.1.1. Historical Methods for Altitude Determination

4.1.2. GNSS

4.1.3. LiDAR

4.1.4. Other Methods

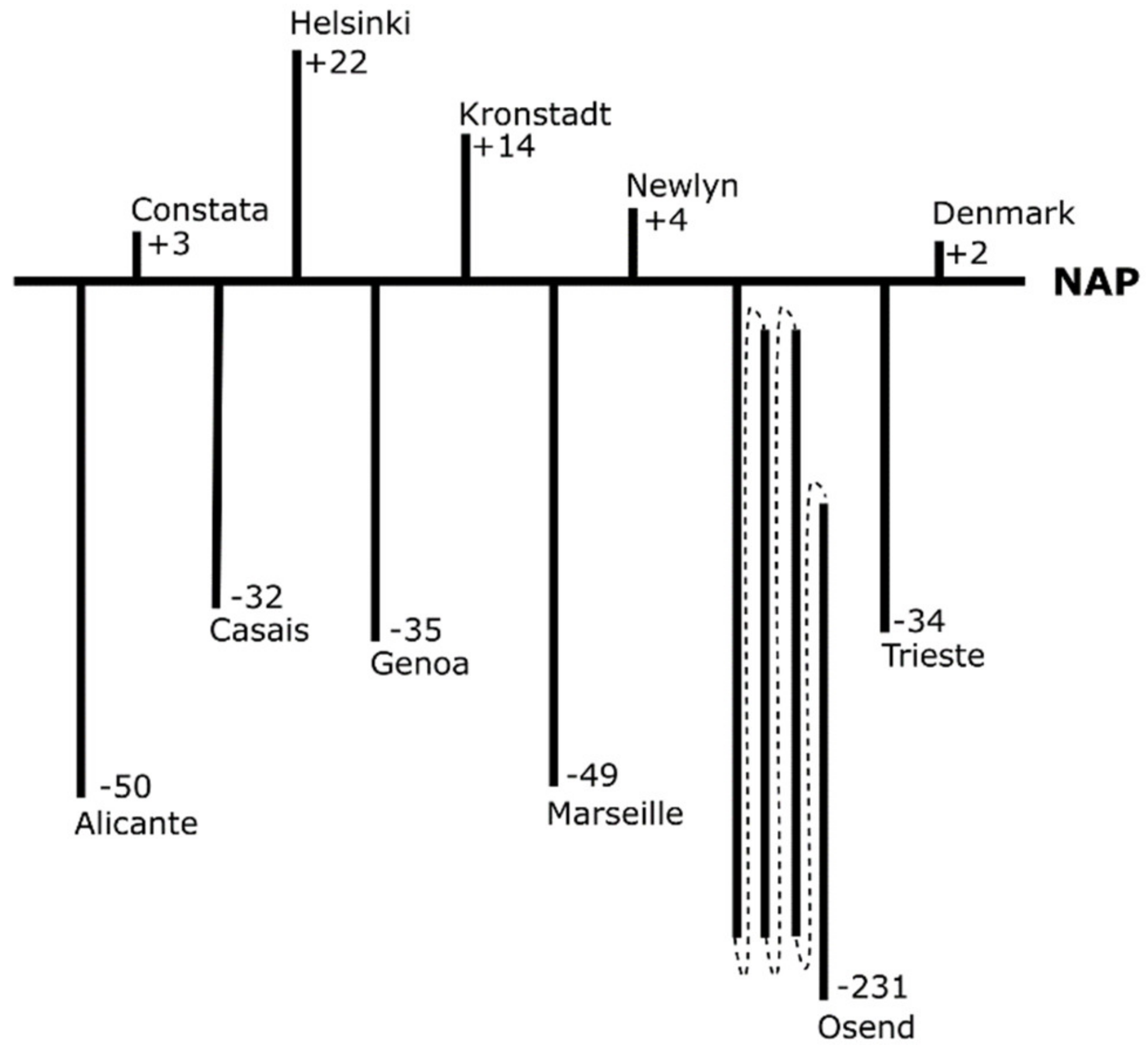

4.2. The Reference System and Geoid Models

4.3. Adopted Methodology

- Selection of ASL data: the activity consisted in the selection of the specific fragment of ASL point cloud for the corresponding peak; here, the selection method was applied with a 3D buffer of 500 m radius;

- The selected point cloud was the input data for DTM calculation; the natural neighbour method was used for grid interpolation from irregularly distributed points;

- Finding the position of the highest point and optical verification of its position on the basis of available materials: orthophoto maps, satellite images, topographic maps and others. Since for some peaks the indication was ambiguous (small differences of one to five centimetres), it was decided to record data for more than one point;

- Designing the measurement session by planning the access route, the stopping point and the route to the summit. At this point, measurement forms containing, among others, XYZ coordinates, a fragment of the base map, and a form to be completed during measurements were also created in an automated way;

- Upon reaching the summit, the height was verified using a GPS receiver (if possible) or a leveller. This allowed the selection of the highest point;

- At this point, it was decided on the basis of local vision about the location of the measuring point; most often, it was a direct measurement on the point, and in four cases, an eccentric point was measured (Table 2);

- GNSS measurement depending on possibilities using the RTK method or static method;

- In the case of eccentric measurement, the height was transferred from the GNSS point to the highest point;

- The last stage was calculating and recording of all data, intermediate results, measurements, and photo documentation in the database.

5. Results

6. Discussion

6.1. A Comparison of the Methods for Altitude Determination: Pros and Cons

6.2. Can a Modification of the Altitude of (the Highest) Summits Influence Tourism in Those Regions?

- The Rudawy Janowickie Mountain Range (Figure 9a): Mount Skalnik (944.5 m) lost its title to Mount Ostra Mała (944.8 m). In this case, the differences were extremely small, which may cause further controversy. Mount Ostra Mała is situated a short distance off the trail (approximately 150 m from the crossing of the yellow, green, blue and red trails (the main Sudetes trails)). It should be noted that Mount Ostra Mała is part of Mount Skalnik;

- The Bardzkie Mountain Range (Figure 9b): Mount Kłodzka Góra (757.2 m) to Mount Szeroka Góra (766.3 m). Mount Szeroka Góra is off the trail (approximately 300 m from the blue trail). Moreover, Mount Szeroka Góra (the highest in the range, according to our calculations) lies within the same mountain as the top of Mount Kłodzka Góra (previously considered the highest);

- The Bystrzyckie Mountain Range (Figure 9c): Mount Jagodna (977.2 m) lost its title to Mount Jagodna Północna (984.5 m). Mount Jagodna Północna is off the trail (approximately 100 m from the blue trail);

- The Kaczawskie Mountain Range (Figure 9d–f): Mount Skopiec (720.7 m) to the summit of Mount Okole (725.3 m). Mount Okole is off the trail (approximately 30 m from the blue trail). As many as four summits were considered for the title of the highest summit of the Kaczawskie Mountains (in addition to the previously mentioned summits, Mount Folwarczna and Mount Baraniec were also included). Moreover, Mount Okole is a lesser known summit;

- The Wałbrzyskie Mountain Range: Mount Chełmiec (850 m) to Mount Borowa (853.3 m). Mount Borowa is on the trail (red and black). Moreover, in the Wałbrzyskie Mountains, Mount Borowa has long been recognised by tourists as the highest mountain in the range. Many tourists climb this summit and Mount Chełmiec.

7. Conclusions

- By investigating an entire mountain range, this research demonstrated the need for verification of the altitude of peaks and verification of which peak is the highest. For the Sudetes Mountains, in most printed sources, old altitude data were later reproduced in other (more recent) editions of the Sudetes guidebooks or changed to new, ‘inaccurate’ ones. A comparison of these altitude data with our GNSS measurements demonstrated the need for an update of the Internet and book sources. Furthermore, LiDAR should be used as a first-stage method (before professional GNSS field measurements), as its accuracy is questionable. This study highlights the urgent need for the correction of peak heights. In general, people trust maps and books and expect the information they contain to be accurate. Moreover, altitude data are usually relied upon by authors in various research activities. Thus, the primary conclusion of this study is not only the need for altitude corrections but also the need for improvement of the accuracy of data on the Internet and in printed sources. Furthermore, as mentioned earlier, Wikipedia is freely accessible by the public (e.g., using this research as a source); however, in the case of books and maps, only publishers and authors can cease reproduction of old and inaccurate data. After this article is published, the authors will disseminate information about mountain heights and the highest peaks in each mesoregion by including the study data in the WikiData database. Therefore, the data will be easily accessible in all languages. The altitude information (and the location of the highest point of a mountain) must be included in official topographic maps. This can only happen if the contractors of these maps are obliged to use correct data sources such as PRNG. In this database, height information can be recorded as comments. An alternative method could be to manually edit the DTM rasters and give one cell representing the highest point of the mountain the correct height. Perhaps the GUGiK would decide to take such a step in the next tender for large-scale LiDAR data acquisition. For this reason, it is crucial to record significant mountain heights in a public database such as the PRNG. Information on mountain heights, based on GNSS measurements, LiDAR data analysis and a literature query, would be reliable for the producers of topographic maps. Technical standards for topographic map preparation indicate the numerical terrain model as the source for elevation points. This is one of the few exceptions because most objects on Polish contemporary topographic maps were created using the Database of Topographic Object (BDOT10k) as a source. The names of the mountains originate directly from the PRNG database. The standards do not specify where the value for the height of a mountain should come from. Therefore, it is necessary to disseminate knowledge about the importance of using supplementary GNSS measurements for mountain peak altitudes, as demonstrated in this study. The sources compared in the article were suggested for use by the geodetic administration in Poland. It was a NMT service, which allows users to obtain heights for any point from the territory of Poland. The connection of this website with a database storing information about geographical objects (National Register of Geographic Names) allowed the authors to treat it as the official source of altitude data. This service is based on data from airborne laser scanning. The same data (but used in a different way) was compared in the article. This allowed for a critical analysis of this data source, which, when used incorrectly (but recommended by the administration), provides erroneous results. The authors found no such comparison in the literature;

- The approach used in the article allows for the minimization of errors in the future by using this type of data in determining the height of mountains. These analyses seem important not only for Polish researchers but also for a constantly growing number of other countries in Europe and worldwide, where LiDAR datasets are becoming more freely accessible to anyone interested;

- Moreover, measurements from the LiDAR in this text were made by creating hydrological maps; thus, it cannot be treated as a reliable source for mountain altitude determination. The ‘theoretica’ error calculated by the authors is 18 cm, while comparison with GNSS results lead up to a couple of metres;

- Altitude obtained from direct GNSS measurements are the most accurate and reliable from all techniques currently used. In the worst-case error, this can lead to a 12 cm difference;

- The most important issue is the differences between GNSS and LiDAR. If the altitudes from LiDAR are bigger than from GNSS, the source of the error might be caused by the incorrect classification (e.g., grass or trees in top). In our case, the majority of the altitudes from LiDAR are smaller than GNSS and bigger than the accuracy (18 cm) factor, which cannot be treated as the classification issue, more like ‘real’ LiDAR accuracy;

- The last but most important issue is a global problem of the data sources. Most of the available data on the Internet are based on the DTM from the LiDAR data; our paper shows that these altitudes cannot be treated as reliable and differences between ‘true’ values can be up to a few metres.

8. Limitations

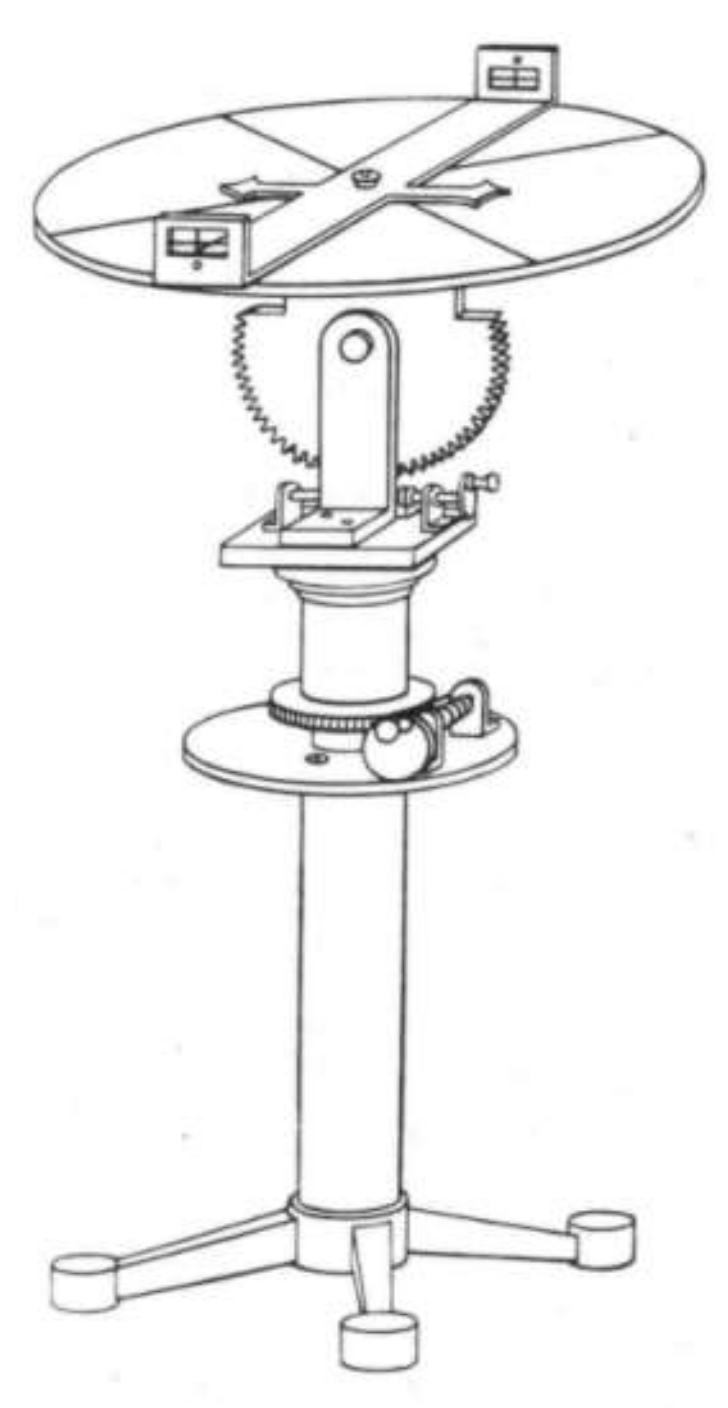

- Steep inselbergs making it difficult to stabilise the measuring instrument (Figure 8);

- High vegetation at the summit site making it difficult to take GNSS measurements (Figure 10a);

- Low vegetation making it difficult to identify the highest point of the summit (Figure 10a);

- Technical infrastructure not related to tourism (Figure 10b);

- Tourist infrastructure (e.g., on Mount Borowa);

- Rocks at the summit that were not permanently attached to the ground (e.g., loose mounds of stones on Mount Wysoka Kopa).

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| No | Summit (24) | Mountain Range (14) | Heights Sources [m] | G-L [m] | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internet Sources | Paper Sources | Calculated | |||||||||||||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (G)NSS | σG [m] | mG [m] | (L)iDAR | ||||

| 1 | Śnieżka | Karkonosze Mts | 1603.3 | 1602.0 | 1603.0 | 1603.3 | 1603.0 | 1603.0 | 1602.0 | 1602.0 | 1605.0 | 1603.0 | 1602.0 | 1602.0 | 1603.2 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 1603.2 | 0.0 |

| 2 | Śnieżnik | Śnieżnika Massif | 1423.0 | 1425.0 | 1426.0 | 1425.0 | 1422.9 | 1425.0 | 1425.0 | 1425.0 | 1422.0 | 1426.0 | 1425.0 | 1425.0 | 1423.0 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 1427.2 | −4.2 |

| 3 | Wysoka Kopa | Izerskie Mts | 1126.0 | 1126.0 | 1126.0 | 1126.0 | 1127.0 | 1126.0 | 1126.0 | 1126.0 | 1127.0 | 1126.0 | 1126.0 | 1126.0 | 1127.6 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 1127.3 | 0.3 |

| 4 | Orlica | Orlickie Mts | 1084.0 | 1084.0 | 1084.0 | 1079.8 | 1080.4 | 1084.0 | 1084.0 | 1080.0 | 1084.0 | 1084.0 | 1084.0 | 1084.5 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 1084.3 | 0.2 | |

| 5 | Wielka Sowa | Sowie Mts | 1015.0 | 1015.0 | 1015.0 | 1014.0 | 1015.3 | 1014.0 | 1015.0 | 1015.0 | 1015.0 | 1015.0 | 1015.0 | 1015.0 | 1015.7 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 1015.3 | 0.4 |

| 6a | Kowadło | Złote Mts | 988.0 | 989.0 | 988.0 | 987.6 | 988.3 | 990.0 | 987.0 | 989.0 | 988.0 | 988.0 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 989.7 | −1.7 | |||

| 6b | Postawna | 1116.8 | 1112.0 | 1117.0 | - | 1115.7 | 1125.0 | 1125.0 | 1109.0 | 1115.5 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 1115.9 | −0.4 | |||||

| 6c | Brusek | 1115.9 | 1116.0 | - | 1114.7 | 1124.0 | 1115.2 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 1115.5 | −0.3 | ||||||||

| 6d | Rudawiec | 1106.4 | 1106.0 | 1106.2 | 1106.9 | 1106.2 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 1106.9 | −0.7 | |||||||||

| 7a | Jagodna | Bystrzyckie Mts | 977.2 | 977.0 | 977.0 | 977.2 | 976.9 | 978.0 | 978.0 | 977.0 | 977.0 | 977.0 | 977.0 | 977.0 | 977.2 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 977.9 | −0.7 |

| 7b | Jagodna Północna | 985.0 | 985.0 | 978.0 | - | 984.5 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 985.1 | −0.6 | |||||||||

| 8a | Skalnik | Rudawy Janowickie Mts | 944.0 | 945.0 | 944.0 | 940.0 | 943.7 | 935.0 | 945.0 | 945.0 | 945.0 | 945.0 | 945.0 | 945.0 | 944.5 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 944.2 | 0.3 |

| 8b | Ostra Mala | 935.0 | 936.0 | 945.0 | 934.2 | 944.8 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 944.4 | 0.4 | |||||||||

| 9 | Waligóra | Kamienne Mts | 933.9 | 936.0 | 934.0 | 936.0 | 933.9 | 936.0 | 936.0 | 936.0 | 936.0 | 936.0 | 936.0 | 934.3 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 934.3 | 0.0 | |

| 10 | Szczeliniec Wielki | Stołowe Mts | 919.0 | 919.0 | 919.0 | 919.1 | 910.3 | 919.0 | 919.0 | 919.0 | 919.0 | 919.0 | 919.0 | 919.0 | 921.7 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 921.6 | 0.1 |

| 11 | Biskupia Kopa | Opawskie Mts | 890.0 | 889.0 | 891.0 | 890.3 | 886.1 | - | 889.0 | 889.0 | 890.0 | 891.0 | 889.8 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 889.8 | 0.0 | ||

| 12a | Chełmiec | Wałbrzyskie Mts | 851.0 | 869.0 | 851.0 | - | 849.8 | 850.0 | 869.0 | - | 834.0 | 851.0 | 869.0 | 850.0 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 850.0 | 0.0 | |

| 12b | Borowa | 853.3 | 853.0 | 853.1 | 853.2 | 854.0 | 853.0 | 853.0 | 853.0 | 853.0 | 853.4 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 853.4 | 0.0 | ||||

| 13a | Kłodzka Góra | Bardzkie Mts | 757.0 | 765.0 | 757.0 | 762.0 | 756.4 | 762.0 | 765.0 | 765.0 | 762.0 | 765.0 | 765.0 | 765.0 | 757.2 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 757.0 | 0.2 |

| 13b | Szeroka Góra | 765.0 | 766.0 | - | 765.5 | 740.0 | 766.3 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 766.0 | 0.3 | ||||||||

| 14a | Skopiec | Kaczawskie Mts | 718.6 | 724.0 | 719.0 | 724.1 | 718.2 | 724.0 | 724.0 | 724.0 | 720.0 | 724.0 | 724.0 | 720.7 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 720.4 | 0.3 | |

| 14b | Folwarczna | 722.9 | 723.0 | - | 722.2 | 720.0 | - | 724.7 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 722.9 | 1.8 | |||||||

| 14c | Baraniec | 720.3 | 720.0 | 723.3 | 718.7 | - | 723.0 | 720.0 | 720.1 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 719.8 | 0.3 | ||||||

| 14d | Okole | 718 (725.1) | 722.0 | 721.0 | 715.4 | 721.0 | 721.0 | 714.0 | 725.3 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 722.9 | 2.4 | ||||||

References

- Kozioł, K.; Maciuk, K. New heights of the highest peaks of Polish mountain ranges. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apollo, M.; Mostowska, J.; Maciuk, K.; Wengel, Y.; Jones, T.E.; Cheer, J.M. Peak-bagging and cartographic misrepresentations: A call to correction. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apollo, M. The true accessibility of mountaineering: The case of the High Himalaya. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2017, 17, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurick, D.N. Adventure Travel and Sustainable Tourism in the Peripheral Economy of Nepal. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1992, 82, 608–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyaupane, G.P. Mountaineering on Mt Everest: Evolution, economy, ecology and ethics. In Mountaineering Tour; Taylor and Francis Inc.: Oxfordshire, UK, 2015; pp. 265–271. ISBN 9781317668732. [Google Scholar]

- Apollo, M. Dual Pricing—Two Points of View (Citizen and Non-citizen) Case of Entrance Fees in Tourist Facilities in Nepal. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 120, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, O.J.; Hoyer, M.; Hernández, J.; Rodríguez, C.; Márques, V.; Sué, N.; Velandia, J.; Fernandes, J.; Deiros, D. GPS height measurement of peak bolivar, venezuela. Surv. Rev. 2006, 38, 697–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auh, S.C.; Lee, S.B. Analysis of the Effect of Tropospheric Delay on Orthometric Height Determination at High Mountain. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2018, 22, 4573–4579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TeamKILI2008. Precise Determination of the Orthometric Height of Mt. Kilimanjaro. In Proceedings of the FIG Working Week, Eilat, Israel, 3–8 May 2009; p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- European Global Navigation Satellite Systems Agency (GSA). White Paper on Using GNSS Raw Measurements on Android Devices; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Realini, E.; Caldera, S.; Pertusini, L.; Sampietro, D. Precise GNSS Positioning Using Smart Devices. Sensors 2017, 17, 2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lachapelle, G.; Gratton, P.; Horrelt, J.; Lemieux, E.; Broumandan, A. Evaluation of a Low Cost Hand Held Unit with GNSS Raw Data Capability and Comparison with an Android Smartphone. Sensors 2018, 18, 4185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robustelli, U.; Baiocchi, V.; Pugliano, G. Assessment of Dual Frequency GNSS Observations from a Xiaomi Mi 8 Android Smartphone and Positioning Performance Analysis. Electronics 2019, 8, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wielgocka, N.; Hadaś, T. Czy to już koniec? Geodeta 2019, 4, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Q.; Sun, M.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, P. Precise Point Positioning Using Dual-Frequency GNSS Observations on Smartphone. Sensors 2019, 19, 2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uradziński, M.; Bakuła, M. Assessment of Static Positioning Accuracy Using Low-Cost Smartphone GPS Devices for Geodetic Survey Points’ Determination and Monitoring. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 5308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogoi, N.; Minetto, A.; Linty, N.; Dovis, F. A Controlled-Environment Quality Assessment of Android GNSS Raw Measurements. Electronics 2018, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paziewski, J.; Fortunato, M.; Mazzoni, A.; Odolinski, R. An analysis of multi-GNSS observations tracked by recent Android smartphones and smartphone-only relative positioning results. Measurement 2021, 175, 109162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez Diaz, J.C.; Carter, W.E.; Shrestha, R.L.; Glennie, C.L. LiDAR Remote Sensing. In Handbook of Satellite Applications; Pelton, J., Madry, S., Camacho-Lara, S., Eds.; Springer New York: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Coastal Services Center. Lidar 101: An Introduction to Lidar Technology, Data and Applications; NOAA Coastal Services Center: Charleston, SC, USA, 2012.

- Wężyk, P. (Ed.) Informatyczny System Osłony Kraju Przez Nadzwyczajnymi Zagrożeniami. Podręcznik dla Uczestników Szkoleń z Wykorzystania Produktów LiDAR, 2nd ed.; Główny Urząd Geodezji i Kartografii: Warszawa, Poland, 2015; ISBN 9788325421007. [Google Scholar]

- Kurczyński, Z. Fotogrametria (Photogrammetry); PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- White, R.A.; Dietterick, B.C.; Mastin, T.; Strohman, R. forest roads mapped using LiDAR in steep forested terrain. Remote Sens. 2010, 2, 1120–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wężyk, P.; Borowiec, N.; Szombara, S.; Wańczyk, R. Generation of Digital Surface and Terrain Models of the Tatras Mountains based on Airborne Laser Scanning (ALS) Point Cloud. Arch. Photogramm. Photogramm. Cartogr. Remote Sens. 2008, 18, 651–661. [Google Scholar]

- Migoń, P.; Kasprzak, M.; Traczyk, A. How high-resolution DEM based on airborne LiDAR helped to reinterpret landforms—examples from the Sudetes, SW Poland. Landf. Anal. 2013, 22, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfricht, K.; Kuhn, M.; Keuschnig, M.; Heilig, A. Lidar snow cover studies on glaciers in the Ötztal Alps (Austria): Comparison with snow depths calculated from GPR measurements. Cryosphere 2014, 8, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farías-Barahona, D.; Ayala, Á.; Bravo, C.; Vivero, S.; Seehaus, T.; Vijay, S.; Schaefer, M.; Buglio, F.; Casassa, G.; Braun, M.H. 60 years of glacier elevation and mass changes in the Maipo River Basin, central Andes of Chile. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkinson, C.; Demuth, M.; Sitar, M.; Chasmer, L. Applications of airborne LiDAR mapping in glacierised mountainous terrain. Int. Geosci. Remote Sens. Symp. 2001, 2, 949–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrustek, P.; Wężyk, P. Using High Resolution LiDAR Data to Estimate Potential Avalanche Release Areas on the Example of Polish Mountain Regions. In Proceedings of the ISSW 09—International Snow Science Workshop, Innsbruck, Austria, 7–12 October 2018; pp. 495–499. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.; Ma, H.; Zhou, L. DEM Retrieval From Airborne LiDAR Point Clouds in Mountain Areas via Deep Neural Networks. IEEE Geosci. Remote. Sens. Lett. 2017, 14, 1770–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrisman, N.R. The error component in spatial data. Geogr. Inf. Syst. 1991, 1, 165–174. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, L.; Lee, M.Y. Are tourists satisfied with the map at hand? Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 18, 1048–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudrys, J.; Buśko, M.; Kozioł, K.; Maciuk, K. Determination of the normal height of Chornohora summits by a precise modern measurement techniques. Maejo Int. J. Sci. Technol. 2020, 14, 156–165. [Google Scholar]

- Collier, P.A.; Croft, M.J. Heights from GPS in an engineering environment. Surv. Rev. 1997, 34, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Featherstone, W.E.E.; Dentith, M.C.C.; Kirby, J.F.F. Strategies for the accurate determination of orthometric heights from GPS. Surv. Rev. 1998, 34, 278–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poretti, G.G. Reporter 47—The Magazine of Leica Geosystems; Leica Geosystems AG: Heerbrugg, Switzerland, 1999; pp. 28–29. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, M. The height of Mount Everest. Alp. J. 1995, 100, 30–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, K. Measuring Mount Everest. Discover 2000, 36, 38. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, J.; Guo, C.; Zhang, P. Height Determination of Qomolangma Feng (MT. Everest) in 2005. Surv. Rev. 2010, 42, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saburi, J.; Angelakis, N.; Jaeger, R.; Illner, M.; Jackson, P.; Pugh, K.T. Height measurement of Kilimanjaro. Surv. Rev. 2000, 35, 552–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulotu, P. Mount Kilimanjaro Orthometric Height by TZG08 Geoid Model and GPS Ellipsoidal Heights from 1999 and 2008 GPS Campaigns. J. Land Adm. East Afr. 2020, 2. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Prosper-Ulotu-3/publication/315831204_Mount_Kilimanjaro_Orthometric_Height_by_TZG08_Geoid_Model_and_GPS_Ellipsoidal_Heights_from_1999_and_2008_GPS_Campaigns_Journal_of_Land_Administration_East_Africa/links/5e27f59e92851c3aadcfb742/Mount-Kilimanjaro-Orthometric-Height-by-TZG08-Geoid-Model-and-GPS-Ellipsoidal-Heights-from-1999-and-2008-GPS-Campaigns-Journal-of-Land-Administration-East-Africa.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2021).

- Muller, J.-C. The Concept of Error in Cartography. Cartogr. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Geovisualization 1987, 24, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cater, E.; Mieczkowski, Z. Environmental Issues of Tourism and Recreation. Geogr. J. 1996, 162, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beedie, P.; Hudson, S. Emergence of mountain-based adventure tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 625–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, C. Recreational Tourism: Demand and Impacts; Channel View Publications: Clevedon, UK, 2003; Volume 43, ISBN 0047287504272. [Google Scholar]

- Caber, M.; Albayrak, T. Push or pull? Identifying rock climbing tourists’ motivations. Tour. Manag. 2016, 55, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, S.M.; Durand-Bush, N.; Doell, K. Exploring feel and motivation with recreational and elite Mount Everest climbers: An ethnographic study. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2010, 8, 373–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew, A.A.; Han, G. A World Geography of Mountain Trekking. In Mountaineering Tour; Taylor and Francis Inc.: Oxfordshire, UK, 2015; pp. 19–39. ISBN 9781317668732. [Google Scholar]

- Kuby, M.J.; Wentz, E.A.; Vogt, B.J.; Virden, R. Experiences in developing a tourism web site for hiking Arizona’s highest summits and deepest canyons. Tour. Geogr. 2001, 3, 454–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crockett, L.J.; Murray, N.P.; Kime, D.B. Self-Determination Strategy in Mountaineering: Collecting Colorado’s Highest Peaks. Leis. Sci. 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leick, A.; Rapoport, L.; Tatarnikov, D. GPS Satellite Surveying, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; ISBN 9781119018612. [Google Scholar]

- Kleusberg, A.; Teunissen, P.J.G. GPS for Geodesy; Otto, J.-C., Dikau, R., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Earth Sciences; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1996; Volume 115, ISBN 3-540-60785-4. [Google Scholar]

- Seeber, G. Satellite Geodesy; Walter de Gruyter: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 2003; ISBN 9783110200089. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, C.; Hsiao, Y.-S.; Lu, C.; Wu, W.-S.; Tseng, Y.-H. Determination of Northeast Asia’s Highest Peak (Mt. Jade) by Direct Levelling. Surv. Rev. 2007, 39, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, H.; Cao, C.; Jia, H.; Xu, M.; Myneni, R.B. The analysis on the accuracy of DEM Retrieval by the Ground Lidar Point Cloud Data Extraction Methods in Mountain Forest Areas. In Proceedings of the International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), Munich, Germany, 22–27 July 2012; pp. 6067–6070. [Google Scholar]

- Pawłuszek, K.; Borkowski, A.; Ziaja, M. Ocena dokładności wysokościowej danych lotniczego skaningu laserowego systemu ISOK na obszarze doliny rzeki Widawy. Acta Sci. Pol. Geod. Descr. Terrarum 2014, 13, 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Kurałowicz, Z.; Słomska, A. Stacje Mareograficzne i Wybrane Wysokościowe Układy Odniesienia w Europie. Inżynieria Morska i Geotechnika 2015, 843–853. Available online: https://yadda.icm.edu.pl/baztech/element/bwmeta1.element.baztech-b49dec3b-348b-4d5e-abed-9ff1bc971dc5 (accessed on 14 February 2021).

- Solon, J.; Borzyszkowski, J.; Bidłasik, M.; Richling, A.; Badora, K.; Balon, J.; Brzezińska-Wójcik, T.; Chabudziński, Ł.; Dobrowolski, R.; Grzegorczyk, I.; et al. Physico-geographical mesoregions of Poland: Verification and adjustment of boundaries on the basis of contemporary spatial data. Geogr. Pol. 2018, 91, 143–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondracki, J.; Richling, A. Mapa 53.3. Regiony fizycznogeograficzne. In Atlas Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej; IGiPZ PAN, Główny Geodeta Kraju, PPWK im. E. Romera: Warszawa, Poland, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kondracki, J. Geografia Regionalna Polski, 2nd ed.; PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2000; ISBN 9788301130503. [Google Scholar]

- Úřad, Z. Geomorfologické Jednotky ČR. Available online: https://geoportal.cuzk.cz/(S(lfbleuq3wxtolown0jzp4lib))/Default.aspx?mode=TextMeta&side=wms.AGS&metadataID=CZ-CUZK-AGS-GEOMORF&metadataXSL=metadata.sluzba&head_tab=sekce-03-gp&menu=3144 (accessed on 12 October 2020).

- Walczak, W. Sudety i Przedgórze Sudeckie. In Geomorfologia polski, Tom 1 Polska południowa, góry i wyżyny; Klimaszewski, M., Ed.; Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe: Warszawa, Poland, 1972; pp. 173–174. [Google Scholar]

- Potocki, J. Funkcje Turystyki w Kształtowaniu Transgranicznego Regionu Górskiego Sudetów; Wrocławskie Towarzystwo Naukowe: Wrocław, Poland, 2009; ISBN 978-83-7374-061-7. [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowski, W.; Więckowski, M. Korona Gór Polski. Poznaj Swój Kraj 1997, XL, 17. [Google Scholar]

- PTTK Komisja Turystyki Górskiej Oddział Wrocławski Diadem Polskich Gór. Available online: http://www.ktg.wroclaw.pl/diadem.php (accessed on 15 October 2020).

- Zarząd_Główny_PTTK; Kmisja_Turystyki_Górskiej_PTTK; Komisja_Turystyki_Narciarskiej. Górska Odznaka Turystyczna PTTK, Odznaki narciarskie PTTK; Centralny Ośrodek Turystyki Górskiej PTTK: Kraków, Poland, 2015; ISBN 978-83-62473-59-5. [Google Scholar]

- Mazurski, K.R. Masyw Śnieżnika i Góry Bialskie; Oficyna Wydawnicza Oddziału Wrocławskiego PTTK: Wrocław, Poland, 1995; ISBN 83-8555048-8. [Google Scholar]

- Compass. Masyw Śnieżnika, Góry Bialskie; Gmina Stronie Śląskie: Stronie Śląskie, Poland, 2017; ISBN 9788376058283. [Google Scholar]

- Badora, K. Proposition for physico-geographical regionalization of Eastern Sudetes. Pract. i Stud. Geogr. 2018, 63, 59–73. [Google Scholar]

- Cajori, F. History of Determinations of the Heights of Mountains. ISIS 1929, 12, 482–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M.J.T. Surveying Instruments of Greece and Rome; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004; ISBN 0511031939. [Google Scholar]

- Heron. Heronis Alexandrini Opera Quae Supersunt Omnia: Vol. III Rationes Dimetiendi et Commentatio Dioptrica; (German Edition); Schöne, H., Ed.; Vieweg+Teubner Verlag: Wiesbaden, Germany, 1976; ISBN 3519014157. [Google Scholar]

- Hycner, R. Geodezja wczoraj dziś i jutro: Wnauce, technice i w innych dziedzinach. Acta Sci. Acad. Ostroviensis 2007, 43–54. Available online: Bazhum.muzhp.pl/media/files/Acta_Scientifica_Academiae_Ostroviensis/Acta_Scientifica_Academiae_Ostroviensis-r2007-t-n27/Acta_Scientifica_Academiae_Ostroviensis-r2007-t-n27-s43-54/Acta_Scientifica_Academiae_Ostroviensis-r2007-t-n27-s43-54.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2021).

- Szaniawska, L. Nowe metody prezentacji rzeźby terenu: Trójwymiarowe modele, kreskowanie i poziomice—zarys od xvi wieku do 1799 roku. Analectea 2011, 20, 9–50. [Google Scholar]

- Cassini de Thury, C.-F.; Maraldi, J.D.; Cassini, J.-D.; Dheulland, G.A. Nouvelle Carte Qui Comprend les principaux Triangles qui servent de Fondement a la Description Géométrique de la France Levée par ordre du Roy Par Messres; Guillaume Dheulland: Paris, France, 1744. [Google Scholar]

- Konopska, B. O Mappie Krajowej—Jan Śniadecki (1790). Stud. Geohistorica 2017, 5. Available online: http://hint.org.pl/hid=A8150 (accessed on 14 February 2021).

- Alexandrowicz, S.W. Karl Kolbenheyer (1841–1901)—Teacher, naturalist, tourist. Stud. Hist. Sci. 2017, 16, 201–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Gersdorf, A.T. Versuch, die Höfe des Riesengebirges durch Barometrische Abmessungen zu Bestimmen; Glebitschische Buchhandlung: Leipzig, Germany, 1772. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, S. Applied Mathematics and the Quantification of Experimental Physics: The Example of Barometric Hypsometry. Hist. Stud. Phys. Sci. 2014, 15, 127–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolski, J. Topographic cartography of the Western Boyko Region (1772–1939). In The Western Boyko Region—Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow; Wolski, J., Ed.; Instytut Geografii i Przestrzennego Zagospodarowania im. Stanisława Leszczyckiego Polska Akademia Nauk: Warszawa, Poland, 2016; pp. 107–174. ISBN 978-83-61590-64-. [Google Scholar]

- Makowska, A. Precyzyjna niwelacja trygonometryczna w terenach górskich. Pr. Inst. Geod. i Kartogr. 1986, 37, 193–220. [Google Scholar]

- Makowska, A. Dynamika tatr Wyznaczana Metodami Geodezyjnymi; Instytut Geodezji i Kartografii: Warszawa, Poland, 2003; ISBN 839162160X. [Google Scholar]

- GUGiK ASG-EUPOS Serwisy (Usługi). Available online: http://www.asgeupos.pl/index.php?wpg_type=serv&sub=gen (accessed on 1 December 2010).

- Romanyshyn, I.; Hajdukiewicz, M. The Height Survey of Mount Łysica in the Context of Verification of Geodesical and Cartographic Studies. Struct. Environ. 2019, 11, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolecka, N. Photo-based 3D scanning vs. laser scanning—Competitive data acquisition methods for digital terrain modelling of steep mountian slopes. ISPRS Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2012, XXXVIII-4, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šašak, J.; Gallay, M.; Kaňuk, J.; Hofierka, J.; Minár, J. Combined use of terrestrial laser scanning and UAV photogrammetry in mapping alpine terrain. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammartano, G.; Spanò, A. DEM generation based on UAV photogrammetry data in critical areas. In Proceedings of the GISTAM 2016—2nd International Conference on Geographical Information Systems Theory, Applications and Management, Rome, Italy, 26–27 April 2016; pp. 92–98. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, V.K.; Ray, P.K.C.; Jeyaseelan, A.P.T. Orthorectification and Digital Elevation Model (DEM) Generation Using Cartosat-1 Satellite Stereo Pair in Himalayan Terrain. J. Geogr. Inf. Syst. 2010, 02, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruen, A.; Kocaman, S.; Wolff, K. High Accuracy 3D Processing of Stereo Satellite Images in Mountainous Areas. In Proceedings of the Dreilaendertagung, Muttenz, Basel, Switzerland, 19–21 June 2007; pp. 625–636. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Ren, Z.; Wu, C.; Lei, Q.; Gong, W.; Ou, Q.; Zhang, H.; Ren, G.; Li, C. DEM generation from Worldview-2 stereo imagery and vertical accuracy assessment for its application in active tectonics. Geomorphology 2019, 336, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepe, A. A Review of Interferometric Synthetic Aperture RADAR (InSAR) Multi-Track Approaches for the Retrieval of Earth’s Surface Displacements. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarov, A.; Minchev, D.; Minchev, C. InSAR Modeling of Geophysics Measurements. In Geographic Information Systems in Geospatial Intelligence; IntechOpen Limited: London, UK, 2019; p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Kadaj, R. Algorytm Opracowania Modelu PL-geoid-2011. In Proceedings of the Realizacja Osnów Geodezyjnych a Problemy Geodynamiki, Grybów, Poland, 25–27 September 2014; Próchniewicz, D., Ed.; Politechnika Warszawska: Grybów, Poland, 2012; p. 26. [Google Scholar]

- Praca Zbiorowa. Niwelacja Precyzyjna; Baran, W., II, Ed.; PPWK im. E. Romera S.A.: Warszawa, Poland; Wrocław, Poland, 1993; ISBN 83-7000-082-7. [Google Scholar]

- RTKLIB RTKLIB: An Open Source Program Package for GNSS Positioning. Available online: http://www.rtklib.com/ (accessed on 11 November 2020).

- Psychas, D.; Bruno, J.; Massarweh, L.; Darugna, F. Towards Sub-meter Positioning using Android Raw GNSS Measurements. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Technical Meeting of the Satellite Division of the Institute of Navigation, ION GNSS+ 2019, Hyatt Regency, Miami, FL, USA, 16–20 September 2019; pp. 3917–3931. [Google Scholar]

- Darugna, F.; Wübbena, J.; Ito, A.; Wübbena, T.; Wübbena, G.; Schmitz, M. RTK and PPP-RTK Using Smartphones: From Short-Baseline to Long-Baseline Applications. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Technical Meeting of the Satellite Division of the Institute of Navigation, ION GNSS+ 2019, Hyatt Regency, Miami, FL, USA, 16–20 September 2019; pp. 3932–3945. [Google Scholar]

- Polski Klub Zdobywców Korony Gór Wykaz szczytów Klubu Zdobywców Korony Gór Polski. Available online: https://kgp.info.pl/wykaz-szczytow/ (accessed on 11 October 2020).

- Mapa-Turystyczna.pl. Available online: https://mapa-turystyczna.pl (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Chanas, R.; Czerwiński, J. Sudety. Przewodnik; Wydawnictwo Sport i Turystyka: Warszawa, Poland, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Sarosiek, J.; Sembrat, K.; Wiktor, A. Sudety; Wiedza Powszechna: Warszawa, Poland, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Collective Work. Atlas Gór Polski. Szczyty w Zasięgu Ręki; Expressmap Polska Sp. z o. o.: Warszawa, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- GUGiK Numeryczny Model Terenu. Available online: http://www.gugik.gov.pl/pzgik/zamow-dane/numeryczny-model-terenu (accessed on 14 October 2020).

- Minister of Administration and Digitization Regulation of 14 February 2012 concerning National Register of Geographical Names. Dz. Ustaw 2012, 1–80. Available online: http://ksng.gugik.gov.pl/pliki/Ljubljana_report.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2021).

- Skorupa, B. The problem of GNSS positioning with measurements recorded using Android mobile devices. Bud. i Archit. 2019, 18, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The General Directorate for Environmental Protection. Aktualizacja Granic Mezoregionów Fizyczno-Geograficznych Polski. Available online: https://www.gdos.gov.pl/aktualizacja-granic-mezoregionow-fizyczno-geograficznych-polski (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Angus-Leppan, P.V. The height of mount everest. Surv. Rev. 1982, 26, 367–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wielka Korona Gór Polski Czyli 40 Najwyższych Szczytów Wszystkich Pasm Górskich w Polsce. Available online: http://www.wielka-korona-gor-polski.102.pl/index.htm (accessed on 1 September 2020).

- Vystoupil, J.; Šauer, M.; Repík, O. Quantitative Analysis of Tourism Potential in the Czech Republic. Acta Univ. Agric. Silvic. Mendelianae Brun. 2017, 65, 1085–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stursa, J. Impacts of Tourism Load on the Mountain Environment (A Case Study of the Krkonoše Mountains National Park—the Czech Republic). In Proceedings of the Monitoring and Management of Visitor Flows in Recreational and Protected Areas, Vienna, Austria, 30 January–2 February 2002; pp. 364–370. Available online: https://mmv.boku.ac.at/refbase/files/stursa_jan-2002-impacts_of_tourism_l.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2021).

- Bartos, L.; Cihar, M. Socio Environmental Attitudes amongst the Inhabitants of Border Mountain Regions Close to the Former Iron Curtain: The Situation in the Czech Republic. J. Environ. Prot. 2011, 2, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žebříček letošních výstupů nad 1000 m n. m. Available online: https://www.vrcholovka.cz/zebricek/letosnich-vystupu-nad-1000m/ (accessed on 24 September 2020).

- The Czech, Moravian and Silesian Thousanders. Available online: http://www.tisicovky.cz/en/ (accessed on 24 September 2020).

- Vrchařské Koruny. Available online: https://www.vk-bike.eu/ (accessed on 24 September 2020).

- Kapłon, J. Główny Szlak Beskidzki—Od Ustronia w Beskidzie Śląskim do Wołosatego w Bieszczadach. Available online: http://cotg.n.pttk.pl/odznaki/gsb/ (accessed on 15 October 2020).

- Bargański, A.; Drecki, I.; Kucharski, J.; Neugass, H.; Niecikowski, K.; Zieliński, M.; Pluciński, T. Archiwum Map Wojskowego Instytutu Geograficznego 1919–1939. Available online: http://mapywig.org/ (accessed on 15 October 2020).

- Koszarski, W. W Sudetach; Państwowe Zakłady Wydawnictw Szkolnych: Warszawa, Poland, 1963; ISBN 9788302037306. [Google Scholar]

- Walczak, W. Sudety i Pogorze Sudeckie. In Geomorfologia Polski, T1; Klimaszewski, M., Ed.; PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 1972; pp. 176–231. [Google Scholar]

- Czerwiński, J. Sudety. Przewodnik; Muza: Warszawa, Poland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Szewczyk, R. Sudety Dla Aktywnych; Muza: Warszawa, Poland, 2013; ISBN 9788377582152. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Standard I | Standard II |

|---|---|---|

| Point cloud density | ≥4–6 pt/m2 | ≥12 pt/m2 |

| Vertical accuracy (mean error) of the ALS point cloud after alignment (on flat, paved surfaces) | mh ≤ 0.15 m | mh ≤ 0.10 m |

| Horizontal accuracy (mean error) of the ALS point cloud after alignment (on flat, paved surfaces) | mp ≤ 0.50 m | mp ≤ 0.40 m |

| Term of measurement | From October to the end of April | Entire year |

| No | Summit | Mountain Range | Mean Levelling Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GNSS Point | Eccentric Point | dH | |||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |||

| 6b | Postawna | Złote Mts | 1115.4 | 1115.52 | 0.121 |

| 8a | Skalnik | Rudawy Janowickie Mts | 944.2 | 944.47 | 0.274 |

| 12b | Borowa | Wałbrzyskie Mts | 853.0 | 853.38 | 0.382 |

| 13a | Kłodzka Góra | Bardzkie Mts | 755.7 | 757.21 | 1.513 |

| Summit | HS [m] | σHs [m] | dHG-S [m] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mount Śnieżnik | 1422.3 | 4.6 | 0.7 |

| Mount Szczeliniec Wielki | 919.2 | 6.1 | 2.5 |

| Mount Orlica | 1084.3 | 5.7 | 0.2 |

| Mount Borowa | 854.6 | 4.6 | −1.2 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maciuk, K.; Apollo, M.; Cheer, J.M.; Konečný, O.; Kozioł, K.; Kudrys, J.; Mostowska, J.; Róg, M.; Skorupa, B.; Szombara, S. Determining Peak Altitude on Maps, Books and Cartographic Materials: Multidisciplinary Implications. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1111. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs13061111

Maciuk K, Apollo M, Cheer JM, Konečný O, Kozioł K, Kudrys J, Mostowska J, Róg M, Skorupa B, Szombara S. Determining Peak Altitude on Maps, Books and Cartographic Materials: Multidisciplinary Implications. Remote Sensing. 2021; 13(6):1111. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs13061111

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaciuk, Kamil, Michal Apollo, Joseph M. Cheer, Ondřej Konečný, Krystian Kozioł, Jacek Kudrys, Joanna Mostowska, Marta Róg, Bogdan Skorupa, and Stanisław Szombara. 2021. "Determining Peak Altitude on Maps, Books and Cartographic Materials: Multidisciplinary Implications" Remote Sensing 13, no. 6: 1111. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs13061111

APA StyleMaciuk, K., Apollo, M., Cheer, J. M., Konečný, O., Kozioł, K., Kudrys, J., Mostowska, J., Róg, M., Skorupa, B., & Szombara, S. (2021). Determining Peak Altitude on Maps, Books and Cartographic Materials: Multidisciplinary Implications. Remote Sensing, 13(6), 1111. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs13061111