1. Introduction

The Roman hydraulic network and associated mining infrastructure represent one of the largest and best-preserved examples of engineering works in Antiquity. Their relevance was highlighted by the UNESCO in 1997, when the site of Las Médulas (León, NW Spain) was declared a World Heritage Site, due to its importance as an outstanding example of innovative Roman technology, where ancient landscape, both industrial and cultural coexist harmonically [

1,

2,

3].

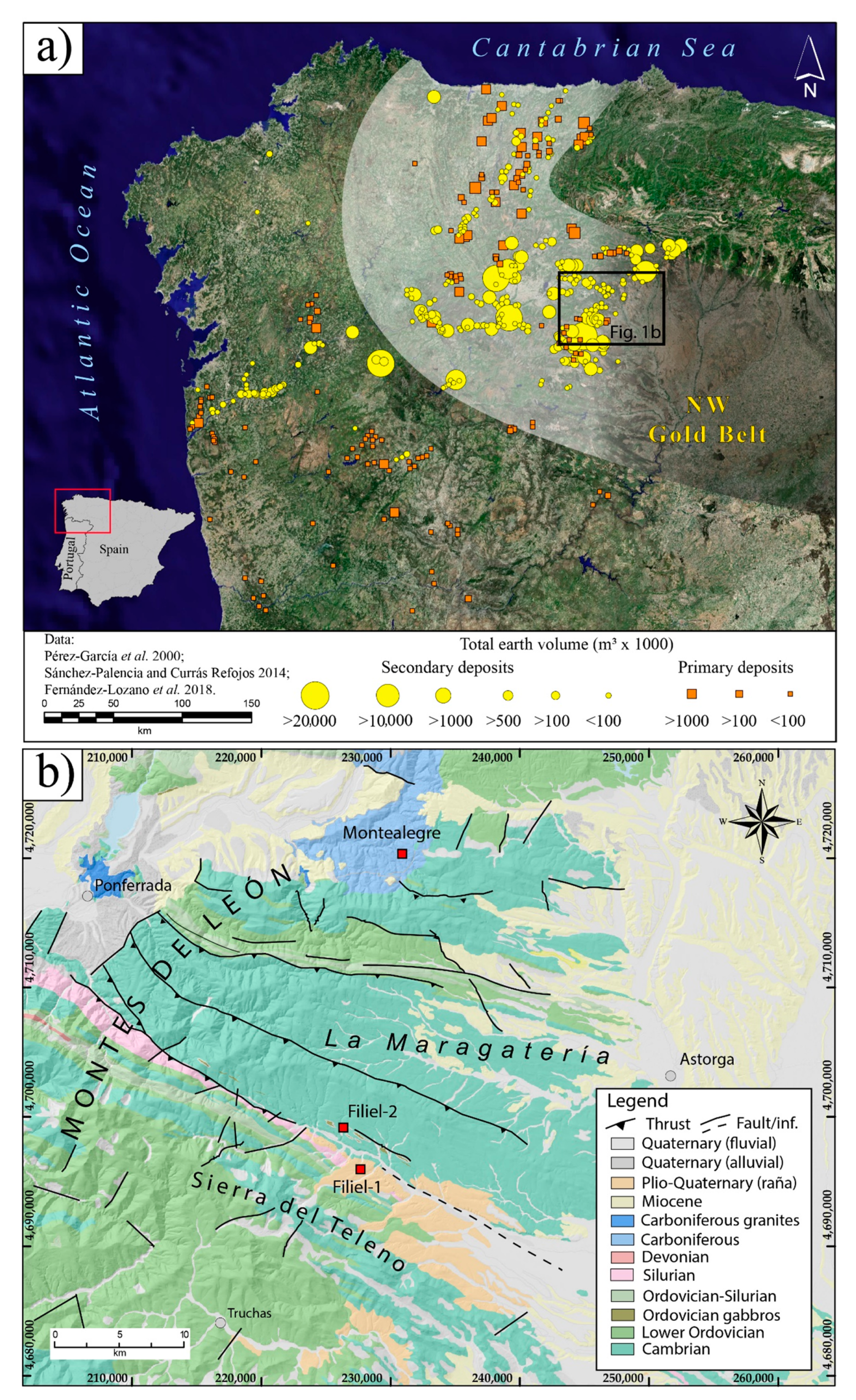

NW Spain and Portugal concentrate a large number of Roman gold works (

Figure 1a) that were systematically studied by archaeologists since the early 1970s [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9], but considerable progress was made in its identification and description in the past decades [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Despite most of these studies focusing on the archaeological interest of the hydraulic network and the analysis of the territory, in recent years, there is a renewed interest on in the geological information surrounding the mining infrastructure [

15,

16]. Geological studies were mostly focused on the characterization of gold lodes and obtention of extracted volumes for quantification of gold extraction, during the Roman times. Recently, there is a new interest in the geomorphological expression of mining activity and drainage development of such ancient landscapes [

17]. However, these works are often restricted by the outcrop exposure and the presence of highly vegetated areas, as most mining sites are located in remote and mountainous regions.

This has led to the integration of remote sensing techniques for the identification and description of Roman mining, in the past years. Thus, high-resolution airborne LiDAR technology was recently used for the exploration of highly vegetated areas providing noteworthy results [

14]. The ubiquitous use of LiDAR in geoarchaeological research is focused on terrain analysis, but it is strongly limited to certain geographic areas and resolutions (1–5 m for the Spanish Geographic Institute-IGN) [

14]. Therefore, the introduction of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) contributed to fill the gap by means of aerial photogrammetry, based on fast and easy-to-use Structure-from-Motion (SfM) algorithms [

18,

19]. Eventually, the combination of high-resolution Digital Terrain Models (DTM) generated from LiDAR and UAV-derived data with image enhancement tools led researchers to improve the visualization of the terrain morphology and mining remains. Undoubtedly, this has had a thoughtful influence on geoarchaeological research by unveiling new findings in the past years [

20], highlighting the potential of UAVs for the study of Roman gold mining infrastructure [

20,

21]. However, the problem of landscape geoarchaeology for identification of ancient structures in areas with dense vegetation cover remains.

Until now, most scientific attention was paid to the documentation of the hydraulic network using traditional stereoscopic images, LiDAR and UAVs [

9,

14,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Often, the accuracy of surveying works, and recognition based on aerial images of morphological features strongly depends on subjective factors inherent to the technician experience, technology, and other extrinsic parameters, such as quality of vision [

24]. Therefore, the implementation of new methodologies that allow a precise and unambiguous methodological approach to developing accurate strategies for mapping morphostructures are of great interests to the scientific community.

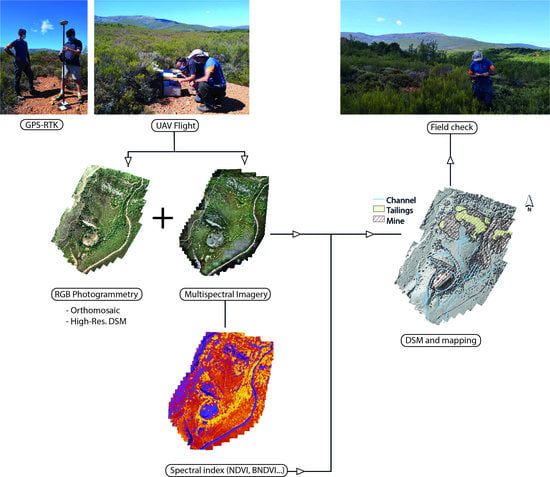

Traditionally, the analysis of the hydraulic parameters obtained on the channels were carried out through aerial photographs, by studying the network, extrapolating observations made locally to the entire system, over tens of kilometers. This entails an oversimplification of the technical complexity of the geometry of the channels from specific evidence. Therefore, there is not yet a detailed analysis that allows the characterization of this infrastructure that helps to establish the impact of geological inheritance on the location and morphology of the channels. These limitations are due to certain factors such as destruction of most of the channel network, anthropic landscape modification and farming, as well as the extensive vegetation cover that hides these remains. To gain insights into the Roman hydraulic system in NW Spain, a multi-approach investigation based on UAV-derived photogrammetry and multispectral images was carried out. This work explores the potential of remote sensing applications for the identification of anthropic structures and scientific analysis of morphometric and lithological factors that involve the Roman hydraulic system. The analysis of spectral signals obtained from high-resolution multispectral images has an extraordinary potential to identify differences on vegetation, which are closely associated with lithological changes. The geomorphic patterns provided by the Roman mining infrastructure can be studied, based on these variations in spectral indices from areas densely covered by vegetation. The channels and other hydraulic elements notably retain humidity levels that allows the establishment of certain plant species showing strong differences in a hydric stress regime, in comparison to the surrounding vegetation. Hence, the implementation of remote sensing methods based on spectral analysis can help to improve the identification and description of such infrastructure. On the one hand, the incorporation of more efficient and higher-resolution technology based on UAV systems contributes to boost the traditional analysis of spectral data from satellite images and aerial orthoimages. On the other hand, the generation of other UAV-derived datasets, like RGB orthomosaics and high-resolution Digital Elevation Models allows the characterization and geometrical analysis of the channels, improving their identification in those areas with low vegetation thanks to the enhancement of geomorphic elements over the landscape. To conduct this study, three channel stretches located in the upper, middle, and lower sectors of the mining infrastructure built on different types of lithology (i.e., sedimentary rocks, metamorphic rocks, and sediments) were investigated. The main objectives were (i) to explore the capabilities of UAV-derived photogrammetry and multispectral images for channel identification in different geological terrains and areas covered by different density degrees of vegetation and species, according to variations in the most common spectral indices, depending on the plant characteristics (BNDVI, NDVI, LCI, and VARI); (ii) to establish the geometrical parameters of the channel network across different exploitation sectors using RGB sensors; (iii) provide new evidence on the control of geology on channel morphology, which allows a better characterization of the Roman hydraulic infrastructure using a combination of UAV-derived dataset consisting of RGB orthomosaics, multispectral images, and Digital Surface Models; and (iv) provide a useful remote sensing methodological approach for studying the mining infrastructure based on different 2D and 3D sources. All in all, the proposed approach enables the analysis of Roman mining remains using remote sensing applications in a distinctive way, providing an accurate, rapid, cost-effective, and easy-to-access methodology, based on UAV-derived data to see the unseen.

3. Hydraulic Infrastructure of Roman Gold Mining

The mining infrastructure in NW Iberia comprises three different elements—(i) the exploitation sectors, such as open-cast mines and large-scale trenches; (ii) mine-waste drainage structures and tailing deposits, and (iii) the hydraulic system. During the whole process of gold mining, hydraulic force was required for extraction, washing, and drainage of waste material. The relevance of water in the mining process was pointed out by Pliny the Elder (NH XXXIII, 74–78) as a major impact on the mining works, even suggesting that water necessarily implied a similar effort or an even higher one, in comparison to the costs of extraction and treatment of the auriferous material [

9].

This importance is highlighted by the numerous legal, administrative, and political aspects preserved in the archaeological record [

34] and the astonishing extent of the hydraulic system, characterized by a more than 1200 km long channel system, mapped in the province of León, some of them running through more than 140 km in the mountains [

35].

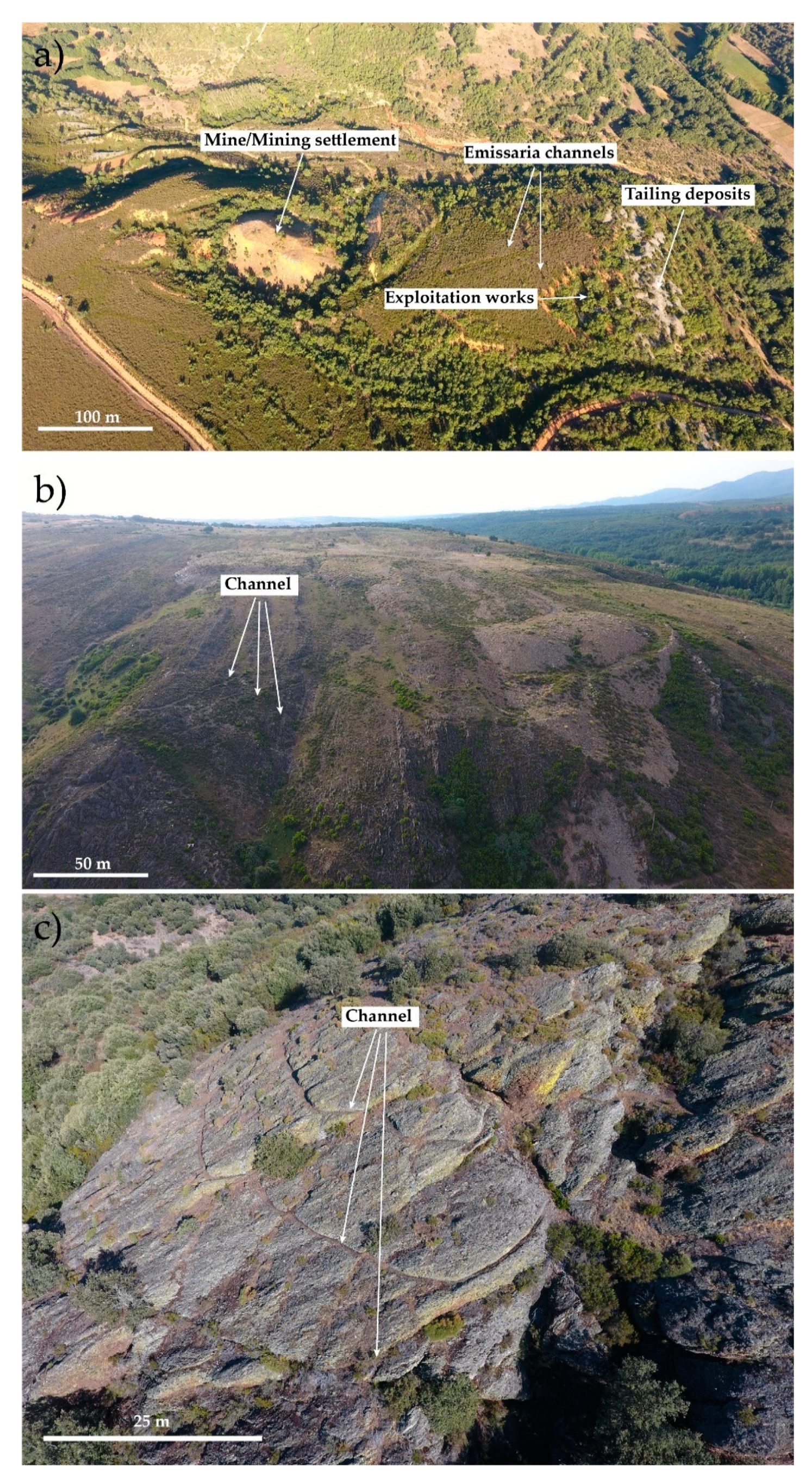

The Roman hydraulic infrastructure was characterized by the presence of water tanks (piscinae or stagna), which served for the regulation of water derived through the supply channels. These channels distributed the water along the mining fronts. The channels were constructed on a slate rock using peaks, chisels, and iron hammers. In fact, in those areas characterized by a high rock strength (i.e., quartzite), galleries and tunnels were constructed using fire. It is important to remark that in NW Iberia, these channels are partially or totally preserved along their length when they were excavated in metamorphic rocks. Channels developed in sediments, also known as leats, were rarely preserved since they were excavated in soils that were intensely transformed due to anthropic activity. However, they can still be found near the exploitation sectors and are associated with placer-gold deposits.

Two different types of channels can be distinguished according to their function [

22,

35]. On the one hand, there are supply channels (i.e.,

corrugus or

canalis) that collect water from rivers or stream headwaters, snow, etc., and are distributed towards tanks that act as regulators of flow into new areas of exploitation (

Figure 2). These generally have their corresponding deposits and their trace was modified during the exploitation works. These often run for tens to hundreds of kilometers in the mountainous regions of NW Iberia. On the other hand, there are the emissary or exploitation channels, which are also known as

emissaria. This type of channels can vary in length and hold some ramifications directed from water tanks towards the mining sectors.

The main morphometric characteristics of the hydraulic system provide useful information concerning the shape and geometry, slope and dimensions of the channels as well as flow rate. In general, channels maintain regular inclinations along their length. It might vary from 0.2 to 0.4%, although in some areas, probably depending upon the stretch of the studied mining sector, they can range from 1 to 1.5%. Although their width is also variable, they might reach a mean width of 1–1.5 m. Recent works carried out in leats found in the region of Zamora suggest that the average flow rate might range from 0.2–0.4 m

3/s, considering a water depth of 0.2–0.35 m [

36].

According to Vitrubio (Vtr. VIII 5 1–2), channels were constructed using sophisticated equipment, always from the mining sector to the catchment areas, to avoid calibration errors that might spoil the hydraulic system. This equipment consisted of levels that used pendulums and water, like present-day alidades and goniometers, to measure horizontal angles (dioptra and chorobates).

4. Materials and Methods

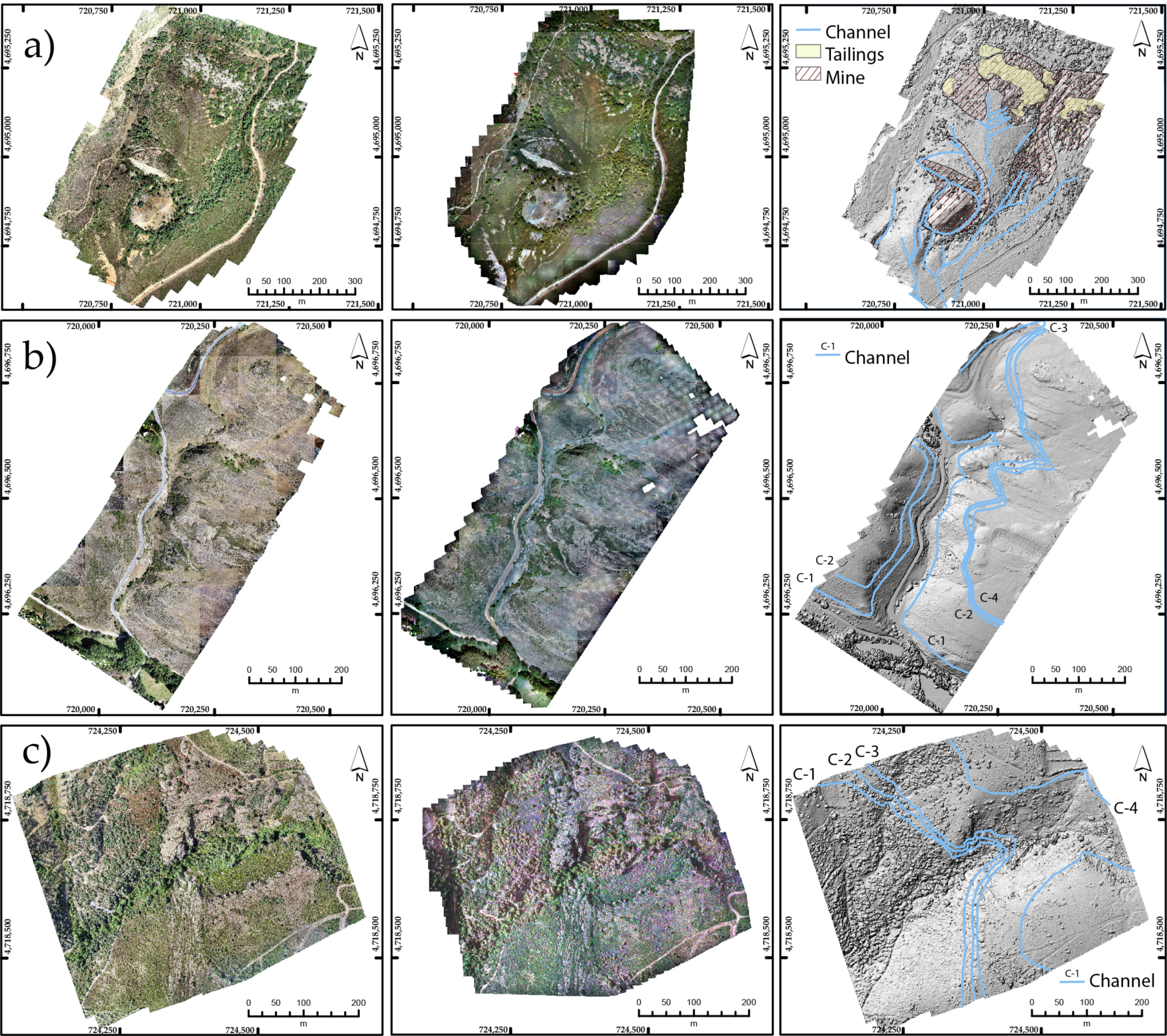

Three different mining sectors (Filiel-I, Filiel-II, and Montealegre sectors) were surveyed using RGB and Multispectral sensors mount in UAVs (

Figure 3). They comprised a wide variety of lithologies, from sedimentary and metamorphic rocks to gravel sediments. Additionally, the studied sectors correspond to the upper, middle, and lower stretches of the hydraulic infrastructure, all characterized by different supplementary mining features (i.e., mine, waste deposits, irrigation channels, etc.).

4.1. Flight Equipment

The DJI Phantom 4 Pro is a simple, yet robust, multi-rotor UAV with a 30-min flight duration, with a maximum weight of 1.388 g, including battery and propellers. It is commercial equipment primarily designed for amateur video and photography capture, but it is frequently employed for research purposes, due to its high performance and low price. The DJI Phantom 4 Pro incorporates an RGB camera, model DJI FC6310, with a physical sensor size of 13.2 × 8.8 mm, a focal length of 8.8 mm and a mechanical shutter feature that avoids typical rolling shutter problems.

The camera was configured to generate a 20-megapixel.jpg image with a resolution of 5472 columns and 3648 rows. Additionally, the automatic exposure feature was used here. The UAV positioning system uses a code-based, single-frequency L1 GNSS receiver, which can achieve—according to the manufacturer’s specifications—an accuracy of 2.5 m. After each flight, all image files had a geographic location stored in the EXIF header (image: ‘Properties/Details’), derived from this GNSS receiver. However, this location information was not used for further processing.

The DJI Phantom Multispectral is a very similar drone unit, as compared to the Phantom 4 Pro, but has some interesting additional features. First, it has a unique camera with 6 different 1/2.9” CMOS sensors, including one RGB sensor, and five monochrome sensors for multispectral imaging. All six sensors have a resolution of 1600 × 1300 pixels, accounting for an effective resolution of 2.08 MPixels per sensor. The final Ground Sampling Distance after the image processing is shown in

Table 1. In front of the 5 monochrome sensors, there are five selective filters for capturing Blue (450 nm ± 16 nm), Green (560 nm ± 16 nm), Red (650 nm ± 16 nm), Red edge (730 nm ± 16 nm), and Near-infrared (840 nm ± 26 nm) channels. The DJI multispectral integrates, on top of the drone, a spectral sunlight sensor that captures solar irradiance. This information is continuously saved as metadata in the TIFF imagery. Once this information is considered, accurate and consistent radiometry data can be achieved across all photos taken during the flight.

A second interesting feature of the Phantom 4 Pro is its Multi-Frequency Multi-System High-Precision RTK GNSS. It uses a L1/L2 GPS/GLONASS/Beidou receiver, which, according to the manufacturer, is capable of a vertical positioning accuracy of 1.5 cm + 1 ppm (RMS) and a horizontal accuracy of 1 cm + 1 ppm (RMS), where 1 ppm indicates an error with a 1 mm increase over 1 km of movement. The RTK receiver is connected with the DJI’s TimeSync system, which continuously aligns the flight controller and the RTK module for ensuring accurate coordinates of the center of each CMOS sensor. According to the manufacturer, this system provides centimeter-level precise measurements on photos.

4.2. Mission Planning

The flight control stations were established at the highest point in each area. Mission planning for all flights was done by the DJI GS Pro App, running IOS on an Apple iPad device. This software automatically calculates the photo positions (or waypoints) and the UAV orientations, transmitting them to the UAV, once the area of interest is delimited and the flight height and overlaps are specified. Two different missions were planned at each of the three locations—one for the high-resolution imagery from the DJI Phantom 4 Pro and the other for the DJI Phantom multispectral. The height of flights was adjusted for the use of two batteries for each mission that resulted in mean GSDs of about 2 cm for the RGB high resolution and 5 cm for the multispectral images. Overlaps and side overlaps were established at 70% and 60%, at the most elevated areas, although due to the high relief in these zones, the averaged sufficient overlaps were much higher. Multispectral flight azimuths were chosen to be transversal to the incident sun rays, whereas high-resolution RGB azimuth strips were parallel to the largest dimension at each location. All flights were planned under a sunny and clear sky day.

Table 1 shows the main flight parameters.

4.3. Georeferencing Strategy

For georeferencing the photogrammetric model, two different resources were used—the RTK positioning feature included in the DJI Phantom 4 Multispectral and the ground control points (GCPs) visible on photos. For enabling RTK fixed solutions on the DJI Phantom 4 Multispectral, an Internet ntrip data flow was passed from an Android Smartphone to the UAV, via the Apple Ipad and the DJI remote. The nearest ETRS89 reference stations available were Astorga and Ponferrada (Red GNSS de Castilla y León), with distances of approximately 30 and 40 km, respectively.

Ground Control Points were widely distributed, particularly towards the periphery, but also in the center of the area (see Sanz-Ablanedo [

37] for further methodological information). Around 9–12 squared, black and white mosaics, 20 cm size targets were established at each of the 3 study areas. For establishing accurate coordinates in GCPs, a surveying grade Leica GS08 Plus receiver was employed. Here, the virtual reference stations (VRS) generated by the Red GNSS de Castilla y León were used as a source of ntrip flow corrections received through the Internet. The RTK performance at the usage conditions was 2–3 cm, like the GSD of the photos.

4.4. Processing

Two processing software packages were used for SfM photogrammetric processing of the aerial images. For processing the high-resolution images of the DJI Phantom 4 Pro, the Agisoft Metashape 1.6.4 was used to produce a high-resolution DSM raster and an RGB orthomosaic, besides other supplementary photogrammetric products, like a dense cloud. On the other hand, the Pix4Dfields 1.8.1 was used for processing the DJI Phantom Multispectral aerial images, using different reflectance indices. Pix4Dfields allowed the radiometrically processing of aerial multispectral images, by taking into account the irradiance sensor and other factors related to camera exposure, in order to achieve absolute reflectance on the 5 monochrome sensors. For processing the images, the default options were selected—the relative rig calibration and the radiometric correction were turned on, and a clear sky was chosen in the weather conditions during capture—.

In the Metashape software, all images of RGB high-resolution, were initially aligned or oriented, using the medium accuracy option. Processing time was reduced by selecting the option “Generic Pre-selection”. With this option, a low-resolution image matching alignment was initially achieved. In a second step, the alignment was repeated at a higher resolution, only considering the overlapping images. In the alignment processing stage, an upper limit of 20,000 feature points and 2000 tie points per image was considered. The option “reference option” was turned off because of the high topographic variability. The “adaptive camera model fitting” option was also turned off due to the high-quality pre-calibration of the Phantom 4 Pro camera [

38]. The “Guided Image Matching” was also turned off since its advantages are not very well documented, nor clear. Residuals obtained after the alignment process indicated a good camera calibration, without areas with substantial errors.

To achieve georeferencing, targets in all photos were measured manually, getting around 10–60 images by the target. Once all measurements were done, a new bundle adjustment was performed by recalculating new positions and orientations for the image block. Prior to this step, the accuracy of the RTK multispectral aerial photos was set to 15 cm, GCPs accuracies were set to 5 cm, whereas georeferencing data of the RGB Phantom 4 Pro aerial photos was turned off. After processing, errors in GCPs were about 3 cm (RMSE), which according to Sanz-Ablanedo et al. [

37] could translate to a real 3D accuracy of about 9 cm (RMSE), in the project.

4.5. General Workflow

After digital information was generated, mapping of the mining infrastructure was aimed at using all acquired datasets. However, since the combination of different datasets does not automatically differentiate between the channel features and any other anthropogenic structure, additional work must be carried out in the field to confirm the channel findings. The RGB orthomosaics allowed the identification of preserved channel stretches and the location of mining infrastructure in the low vegetated areas. The channels were better preserved in rocky outcrops, so RGB images provided better results in the Filiel-II and Montealegre sectors, allowing the recognition of long channel stretches. In addition, in areas with low vegetation cover, images offered good insights into the identification and description of the mining infrastructure. Similar information was provided by the multispectral image, using all bands. A little change was observed in the identification of the hydraulic network. Preserved channels in rock were also rapidly identified using the Digital Surface Models, since differences in relief are displayed in the digital models as linear features. Moreover, the constant width of the channel segments across strike was used for recognition of such structures. It is worth noticing that the paths rarely maintained their width along their length, and the channels were characterized by maintaining a constant slope <1–2%, they tended to follow the topographic contours and more often, the widths were maintained on average across strike. Finally, in those sectors where vegetation cover was dense enough to hide the channel trace, the combination of different spectral indices from multispectral images provided a good response, due to the different types of vegetation.

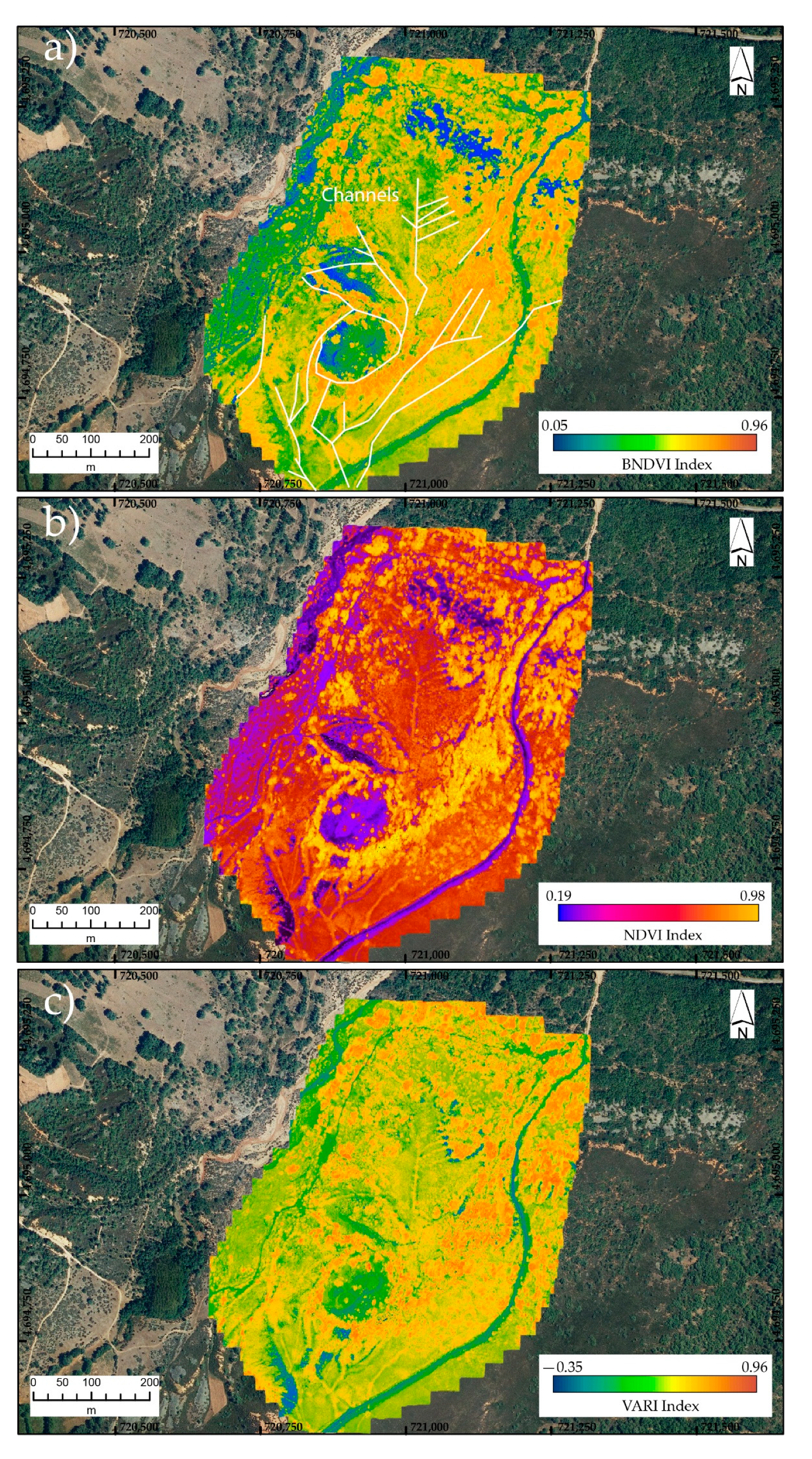

4.6. Spectral Indices Analysis

The spectral indices chosen for the identification of the Roman hydraulic system were selected according to the vegetation response. Nowadays channels are often fully covered by vegetation. Different plant species provided a variety of patterns that allowed the recognition of channel stretches. Low vegetation, characterized in the Filiel-II sector by heather, prickly broom, and rockrose, comprise small leaves that are rapidly affected by hydric stress. However, areas such as Filiel-I are covered with oak trees that present green leaves during summertime and maintain the chlorophyllic function till the leaf is lost in autumn. Therefore, indices such as NDVI, LCI, or VARI might provide an acceptable response based on the variations on chlorophyll content and leaf coverage (high or low), for the identification of vegetated sectors along the channel stretches. According to this rationale, the spectral indices used in this work correspond to the following indices:

The Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), which shows the leaf coverage and plant health according to the humidity conditions:

Being (the reflectance of the near infrared) and the (visible red).

The Blue Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (BNDVI), which shows areas sensitive to the chlorophyll content:

The LCI or Leaf Chlorophyll index, often used for assessing the chlorophyll content in areas of complete leaf coverage:

The VARI or Visible Atmospherically Resistant index (RGB index for leaf coverage):

6. Discussion

A comparison of different data sources from aerial imagery and LiDAR (PNOA-IGN,

www.ign.es) with those obtained from drone flights, showed significant differences in data resolution.

Figure 9 shows one of the sectors studied in the area of Montealegre (Villagatón), where the channels on the orthoimage (35 cm/pix) and LiDAR model (interpolated to 1 m) from the PNOA-IGN database, were not distinguishable (

Figure 9a,b). However, these were easily recognizable in the orthomosaics provided by drones (

Figure 9c,d). The topographic profiles produced using the UAV-derived DSM provided a good estimation of the location of the channels and their geometry. These could be identified by a break in slope observed in the model, as they were excavated in the Carboniferous conglomerates.

Besides the different methodologies employed for improving the identification of channels [

14,

20,

21], the analysis of the geometric characteristics is a matter of discussion among researchers [

35]. Hitherto, the dimensions and width of the channels were considered to vary according to the availability of water resources. Thus, in valleys with nearby rivers and streams of regular flow, the channels were built with characteristics that allowed them to supply water with the maximum efficiency that the hydraulic structure could provide. This conditioned the height of the water sheet, which hardly exceeded 25–30 cm in height, according to the marks identified on the sections of the channels. Similar inferences of water sheet height were established in the mining sector of Rionegro (Zamora), further south [

36]. On the other hand, in the mountainous regions where water resources could be limited seasonally, the water was obtained from springs and snowmelt water, and transported along the narrow channels (0.3–0.5 m) to the water tanks, for regulation (

Figure 2a).

The geometric analysis carried out on the three studied sectors (

Figure 1) strongly depended on the geological characteristics of the terrain. As shown in the previous section, lithological variations play a crucial role in channel box geometry, such as the width. In this case, Carboniferous sedimentary siliciclastic conglomerates present higher strength than the metamorphic slates. Big boulders might impede the construction of the channels influencing the rock-cutting works. Thus, while in the loose sediments the width of the channel could reach 4 m in diameter, the size was reduced in the slates (1.20 m) and was even more remarkable in the Carboniferous clast-supported conglomerates of Montealegre (0.4 m) (compare

Figure 7a,b). In the latter, this was certainly surprising, since it was constructed in a valley with a large number of water resources available throughout the entire year. This suggests that the width of the channel box was not only conditioned by the availability of water resources but must also be controlled by geological factors, which makes the construction of the channel layout difficult, such as the hardness of the rock, its texture, and the fracture pattern.

In addition, as shown in

Figure 7, the channel width varied along its length. The observed variations in the channel box width, along a lithologically homogeneous stretch, were especially evident in the curved sectors (

Figure 4). Hence, in areas of significant curvature, the width of the water box increased to reduce the flow speed. This was already observed in nearby areas along channels constructed in metamorphic slates [

21]. This technical solution would serve to avoid an increase on flow speed that might compromise the well-function of the channel, and its breakage at times when the flow is greater. This is a conservative way for maintenance of the channels, thus avoiding possible breakage that could temporarily affect the course of the mining works.

Channels constructed in metamorphic materials with a fragile mechanical behavior and reduced hardness (i.e., slate), where engineering works would be technically much easier, allowed the construction of a broader channel box. For instance, in the Filiel-II area (

Figure 1b) channels exceed 1.2 m. However, as in the Montealegre example, hard rock makes it difficult to work the rock and the diameter of the box varied along its length to reduce the speed of flow in the curves by increasing the channel´s section (

Figure 7).

A different example was that of the channels excavated in crumbly alluvial sediments of the Plio-Quaternary (Filiel-I area,

Figure 1b), where the width of the channel was much greater, reaching up to 4 m in width (

Figure 4a). This increase in channel width served to maintain the stability of its edges, thus avoiding the channel walls from falling apart, and leading to an eventual clogging of the channel and the subsequent reduction of flow through. High water flow would have had catastrophic consequences for the future of the mining activity, provoking channel destruction.

Everything that was argued up to now implies the need to carry out a correct geometric and hydraulic characterization of the channels, along the representative sections. To do so, new advanced technologies, such as drones, showed the potential to explore and improve the knowledge of the Roman hydraulic infrastructure. This is especially important in mountainous, remote regions, or areas of high vegetation, where the channels are hidden or partially preserved.

Most geoarchaeological works focus their attention on the identification of structures and 3D-documentation of ancient remains using UAV-derived photogrammetry [

20,

40,

41,

42,

43]. Lately, scientific research was implemented by applying multispectral and thermal imagery [

44,

45]. The application of remote sensing methods for scientific research proved to be advantageous, especially in vegetated areas. Thus, the introduction of multispectral images and the processing of spectral indices, such as BNDVI, NDVI, LCI, and VARI provided a good response for the identification of linear structures (i.e., channels and other anthropic features). The former was demonstrated to be a powerful tool to identify channel stretches due to the presence of rock/soil that allowed the colonization of different plant species and the maintenance of moisture necessary to mark the hydric stress in vegetation (

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 8). Depending on lithology, the width and depth of the channel might vary (see the important differences shown above between the channels excavated in sediments or rock). This factor strongly influenced the type of vegetation that could occupy the space. For instance, Plio-Quaternary sediments allowed colonization by high heather bushes and oak trees, since the argillaceous matrix gain humidity (i.e., due to its hygroscopic properties) and have a high drainage potential; while slates and conglomerate rocks (Filiel-II and Montealegre) comprised a poor and thin clayey soil layer colonized by grass, which provided different spectral index. In either case, the impermeable characteristics of the slate rocks and conglomerates offer, in general, vegetation with low spectral index. Little differences were observed between the different spectral indices, but BNDVI and NDVI often offered better results than the VARI and LCI indices. This good response of the BNDVI and NDVI could be related to the sensitivity to the chlorophyll content of the plants, which rely on the plant health. Subtle differences were often found between the VARI and LCI indices, which were probably associated with the type of vegetation in the area. For instance, areas covered by Prickly broom and heather plants (abundant in the Filiel sectors) provided good response for the VARI index, whereas oak trees showed better results using the LCI index. These differences seemed to be related to the type of vegetation, since the chlorophyll content depended on the leaf coverage in oak trees, this could be complete across the whole leaf.

The analysis of multispectral indices is of great interest, since the identification of hydraulic structures does not entirely rely on the skills of the technician that performs the remote sensing analysis, nor on any other extrinsic factors that might affect the extrapolation of the hydraulic network. It is important to remark that potential findings need to be confirmed in the field, given that multispectral images require validation to avoid misleading structures, due to the presence of pathways and other anthropic landscape modifications. The relevance of this work lies on the potential use of UAV-derived images (i.e., RGB and Multi-spectral) for the identification of the Roman hydraulic infrastructure. This is especially important in sectors where difficulties arise from the dense vegetation cover. Our approach would help archaeologist to improve the identification and description of hydraulic remains, opening new possibilities for research worldwide. Good examples in which our methodology could improve the results are the thousands of kilometer-long African and Arabian qanats, karez, and foggaras, as well as the Roman and Arab aqueducts in Europe (Spain, France, Germany, Italy, Romania, etc.) [

46,

47,

48,

49].

As was shown, the study of the Roman hydraulic network could not be exclusively reduced to the mere documentation of the channel arrangement. It requires an integrated analysis that allows addressing archaeological problems from different perspectives (archaeological, geological and mining, and remote sensing). All in all, the multi-approach interpretation of UAV-derived photogrammetric and multispectral information can provide relevant information to gain insights into the main characteristics of the hydraulic system. UAVs also helped to constrain the main limitations faced by channel construction, due to the lithological control. Since the last century, geological analysis was used to solve intriguing archaeological problems [

50,

51]. Henceforth, the combination of different methodologies and approaches combining geoarchaeological analysis, remote sensing technology, etc., could successfully help to improve our archaeological knowledge. This research provided a detailed analysis of the Roman hydraulic system allowing to puzzle out the impact of the Roman mining works in NW Iberia and understanding the landscape transformation that occurred as a result of gold mining activity.

7. Conclusions

UAV-derived photogrammetric products provide valuable information for the description and characterization of the hydraulic mining infrastructure, although it is not exempt from certain limitations. Airborne data allow us to obtain high-resolution images and DSMs and are especially useful in those sectors where orthoimages and LiDAR models (1 m) do not allow the detailed study of the channels. Their use in areas of dense vegetation cover or zones where the infrastructure is partially destroyed (mainly in valleys and strongly anthropogenic peneplains) is now improved by using multispectral images. Therefore, a combination of different methodologies (i.e., photogrammetric and multispectral data) enhances the detailed analysis of the hydraulic network. However, the value of these tools lies on their ability to know how to take advantage of the technique, depending on the extrinsic and intrinsic conditioning factors that make the study of hydraulic network difficult, adapting the research needs to the appropriate methodology in each case. This work explores the conditioning factors that govern channel geometry and dimensions, in addition to the availability of existing water resources in the catchment areas where they are located. It is also worth noticing the impact of lithological factors (rock hardness), as well as other technical factors, such as the hydraulics of the system, to maintain the channels functions throughout their length. Therefore, a combination of different UAV technologies can help to determine the location and geometry of the hydraulic network, providing useful information about the nature and magnitude of the mining works carried out during the domination of the Roman Empire in Iberia. As was stated in the text, the methodological approach based on the analysis of spectral indices from UAV-derived multispectral images was accurate, rapid, high-resolution and cost-effective, providing an extremely useful application of remote sensing data for the identification and description of mining infrastructure. Variability in the coefficients of spectral data were associated with differences in plant species, which in turn, was strongly controlled by lithological variations. These differences highlight the geomorphic impact of the mining infrastructure on the landscape, and thus represent an extraordinary method for studying the hydraulic system. In addition, analysis of RGB images and DSMs provides useful information for the description and morphological characterization of the whole infrastructure, pointing to the geometric control by the lithological variations along different mining sectors. In light of the above, UAV-mulstispectral images represent a promising remote sensing application for accurate, rapid, and cost-effective analysis of densely vegetated and remote areas, to gain new insights into the impact over the territory and extent of one of the most astonishing mining infrastructures ever preserved. Our methodological approach, based on UAV-derived remote sensing methods, would help scientists for recognition of hydraulic structures in vegetated areas, using spectral analysis, and providing a useful tool for surveying their remains worldwide.