Uncertainty Assessment in Multitemporal Land Use/Cover Mapping with Classification System Semantic Heterogeneity

Abstract

1. Introduction

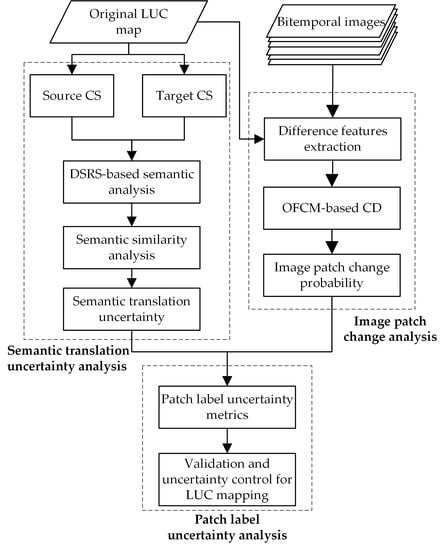

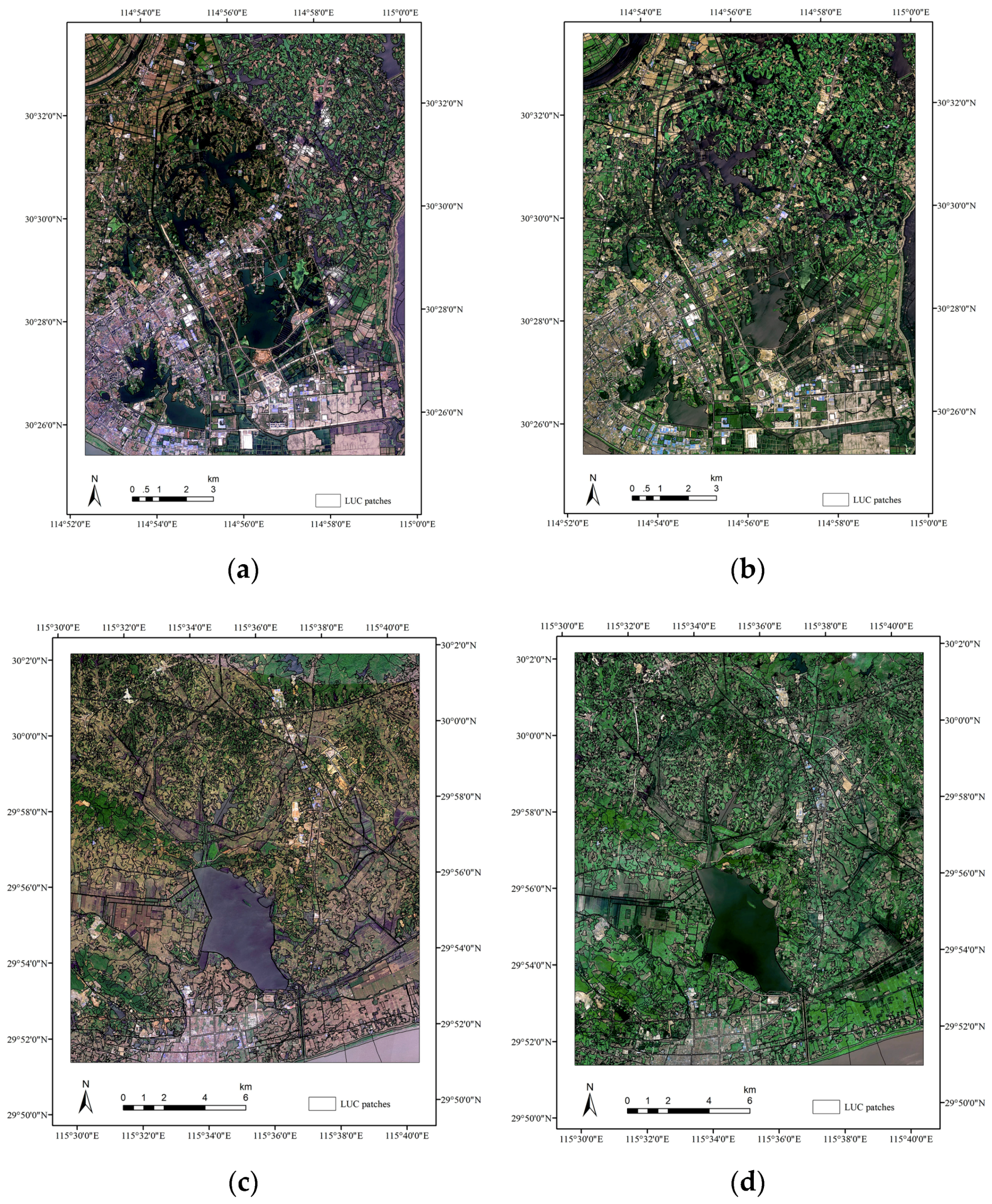

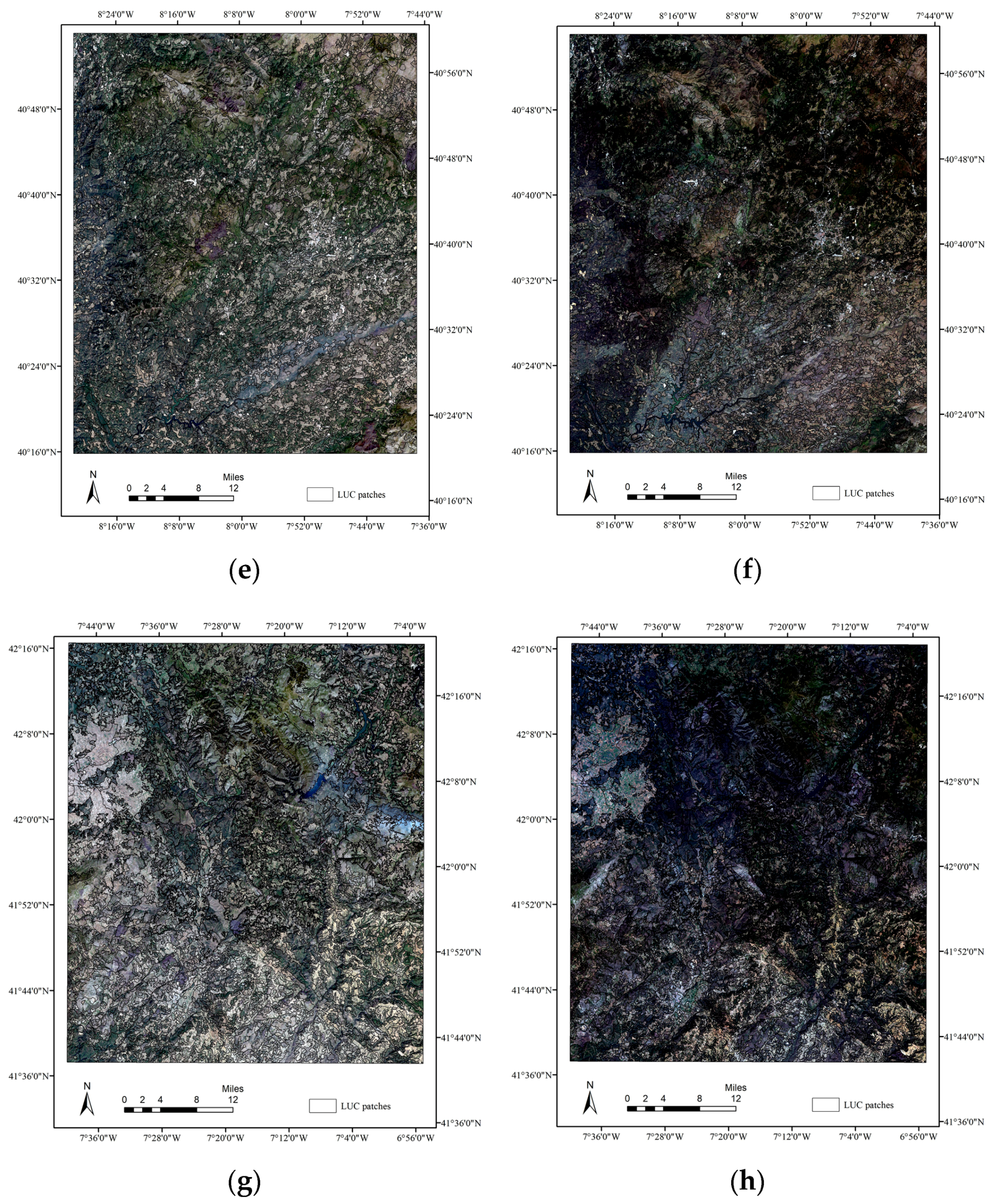

2. Study Areas and Datasets

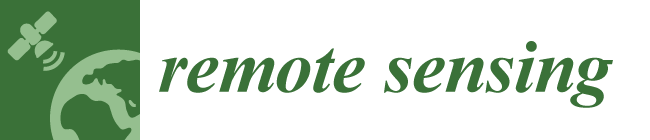

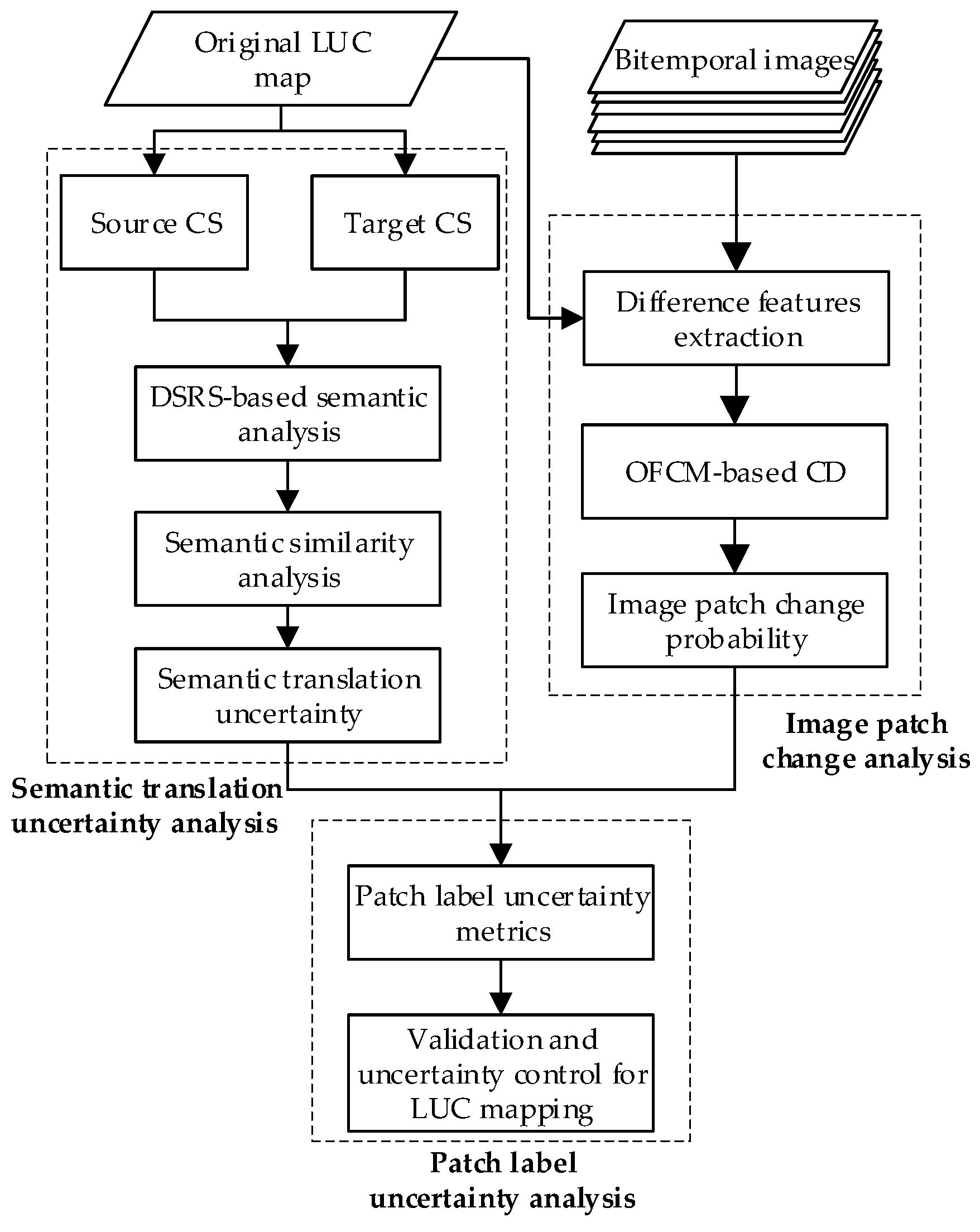

3. Methodology

3.1. Premise and Assumptions

- The impact of human factors, precision of the basic maps, and classification accuracy of updated patches were not considered in this study because there is a large amount of uncertainty in multitemporal LUC mapping and the focus of this research was on the semantic uncertainty between heterogeneous systems and the corresponding effect on the reliability of LUC data.

- We regarded the semantic translation types and image change magnitudes as the main factors affecting patch label uncertainty to model the semantic translation uncertainty and its propagation. This was because, on the one hand, a single class in the source system can be converted into one or more classes in the target system, which causes the semantic feature consistency of class pairs to be different. On the other hand, image patches with larger change magnitudes are more likely to be detected and updated.

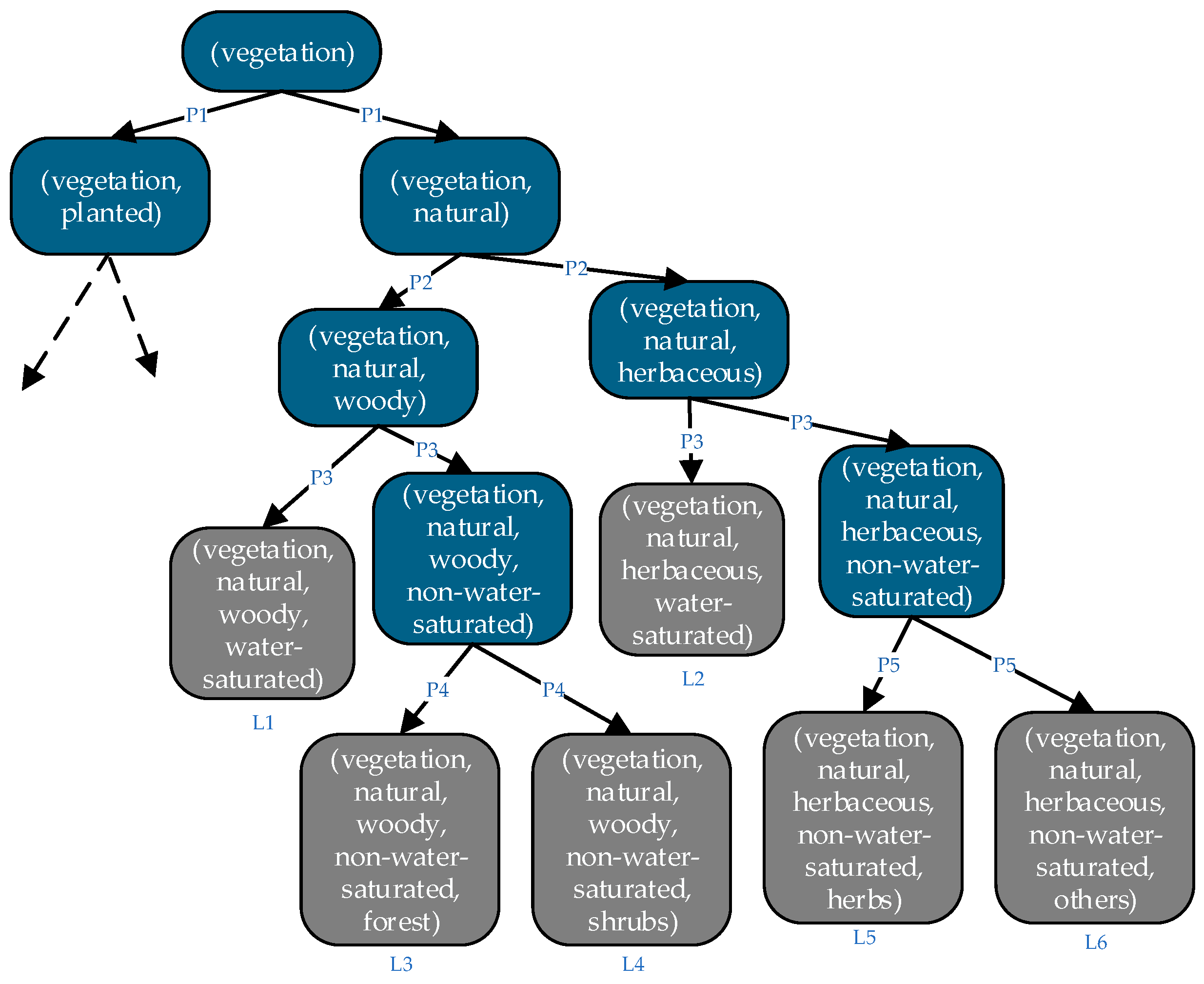

3.2. Semantic Translation Uncertainty Analysis between CSs

3.3. Image Patch Change Analysis

3.4. Patch Label Uncertainty Assessment

4. Results

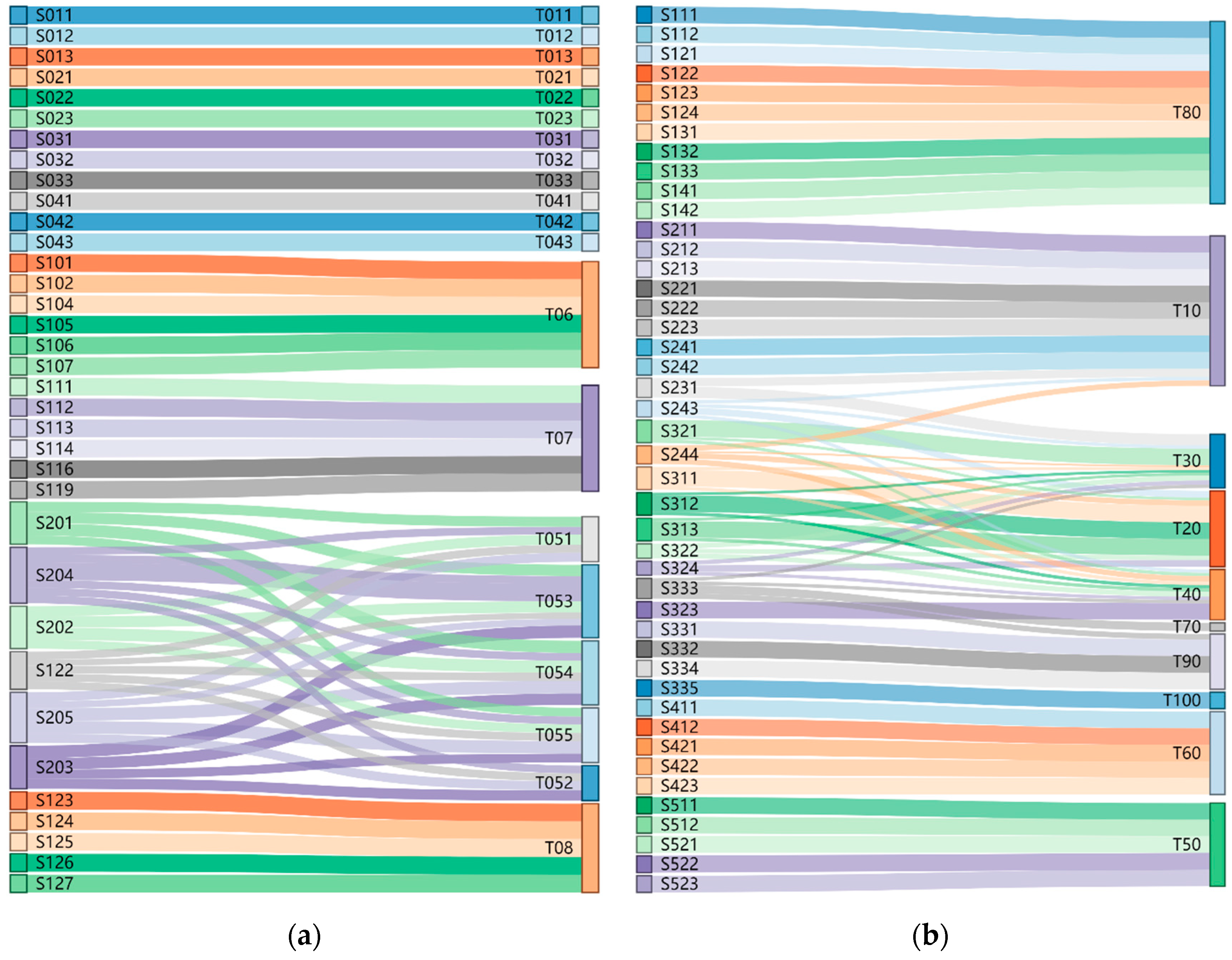

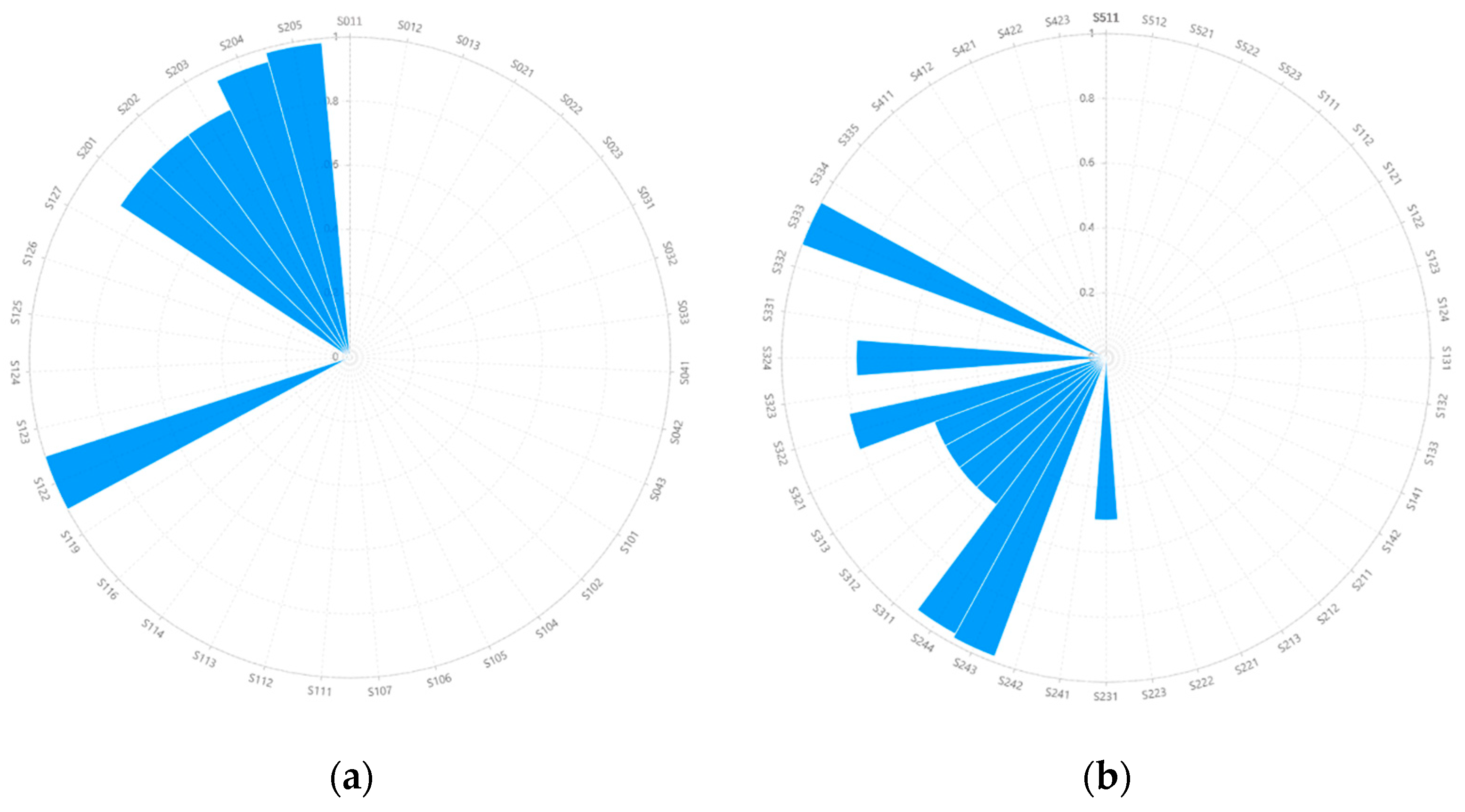

4.1. Results of Semantic Translation Uncertainty Analysis

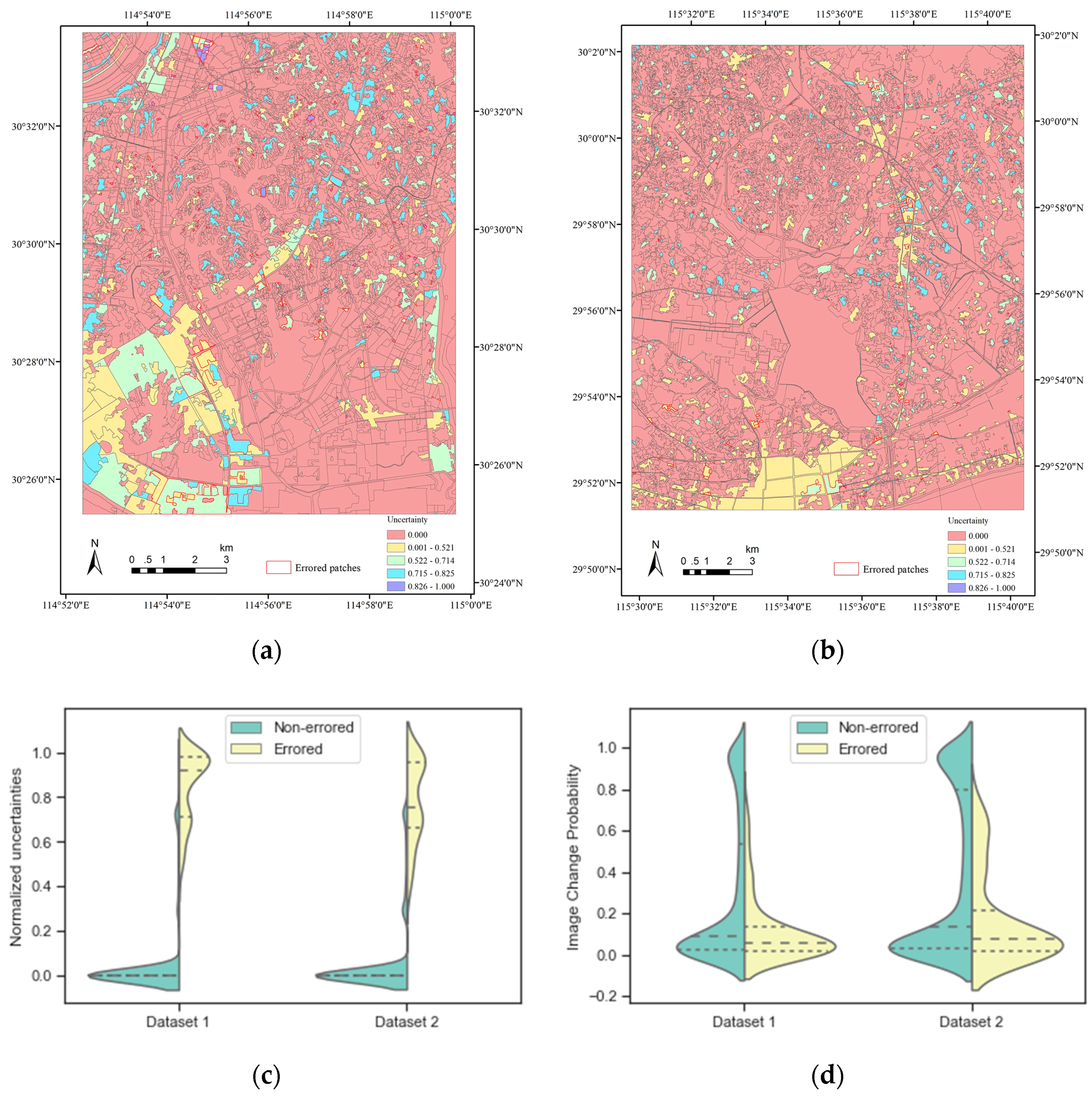

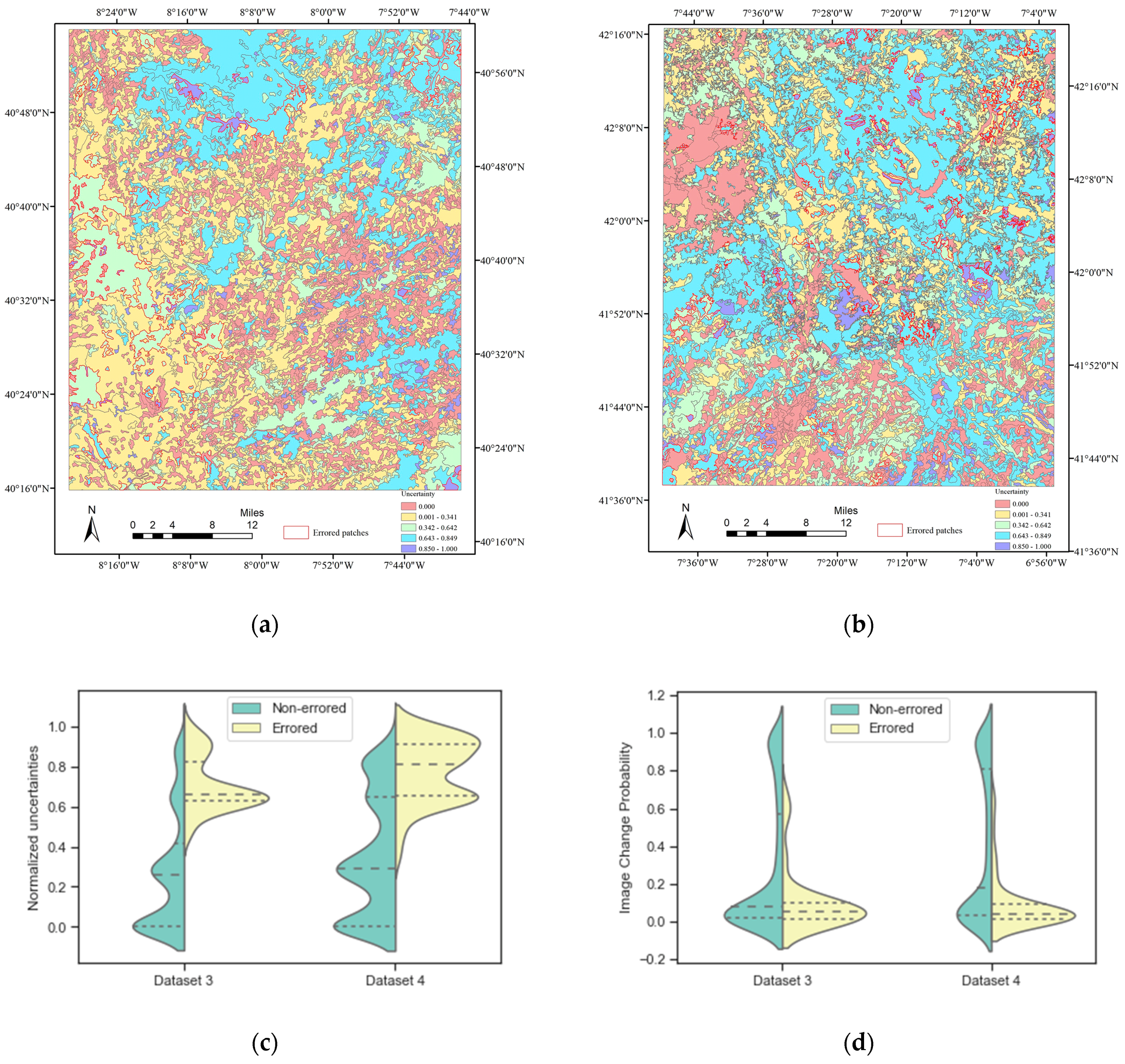

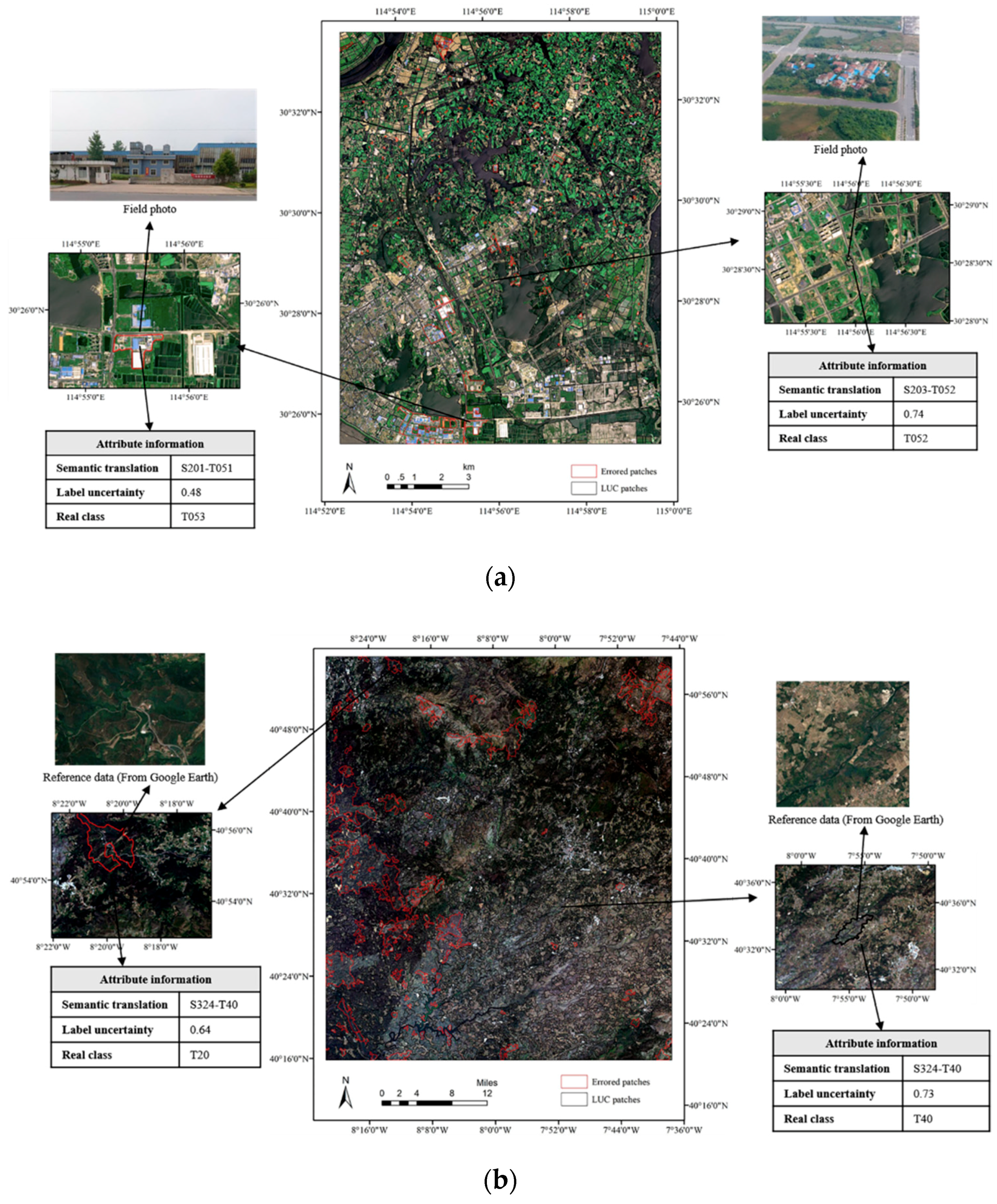

4.2. Results of Patch Label Uncertainty Assessment

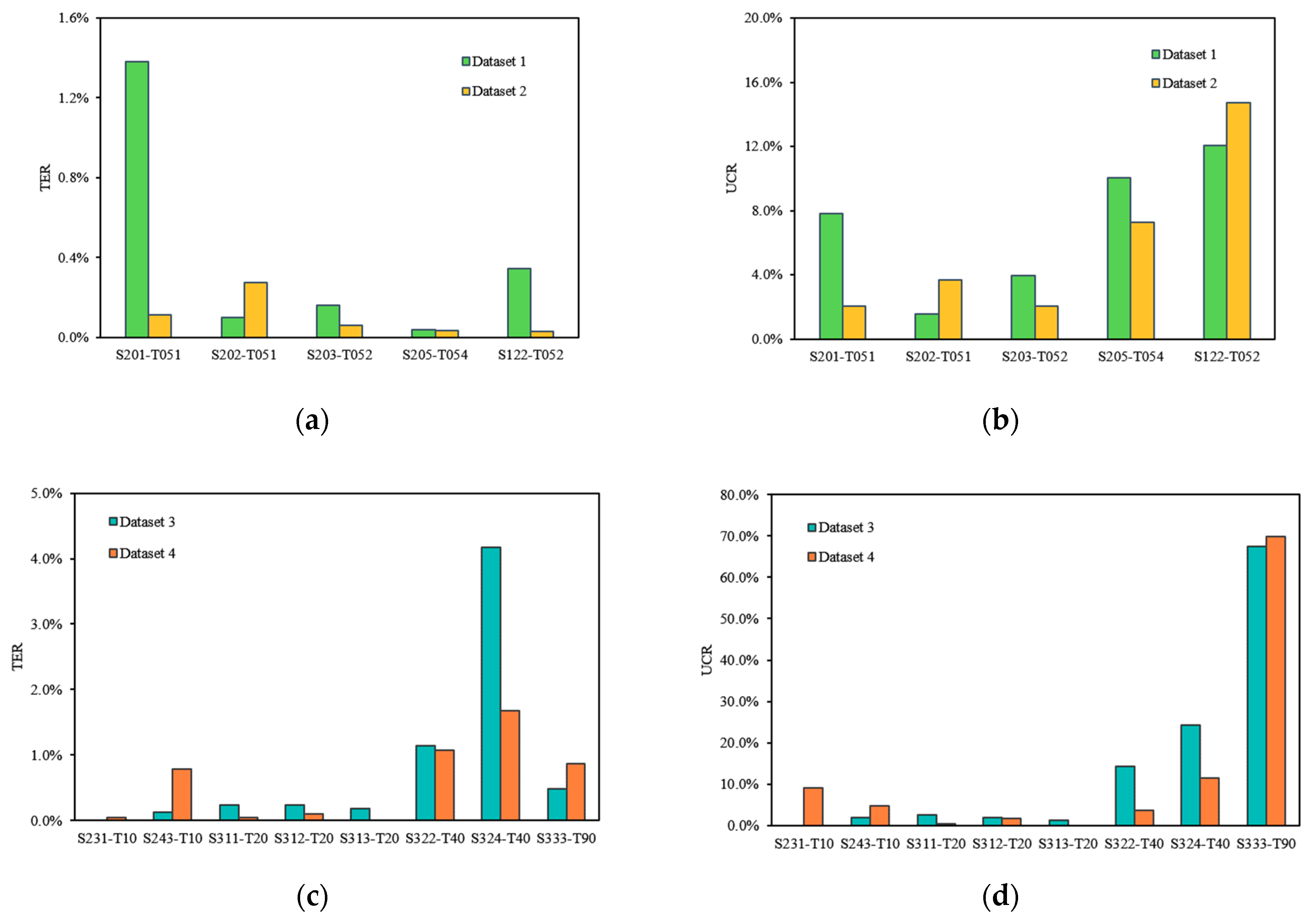

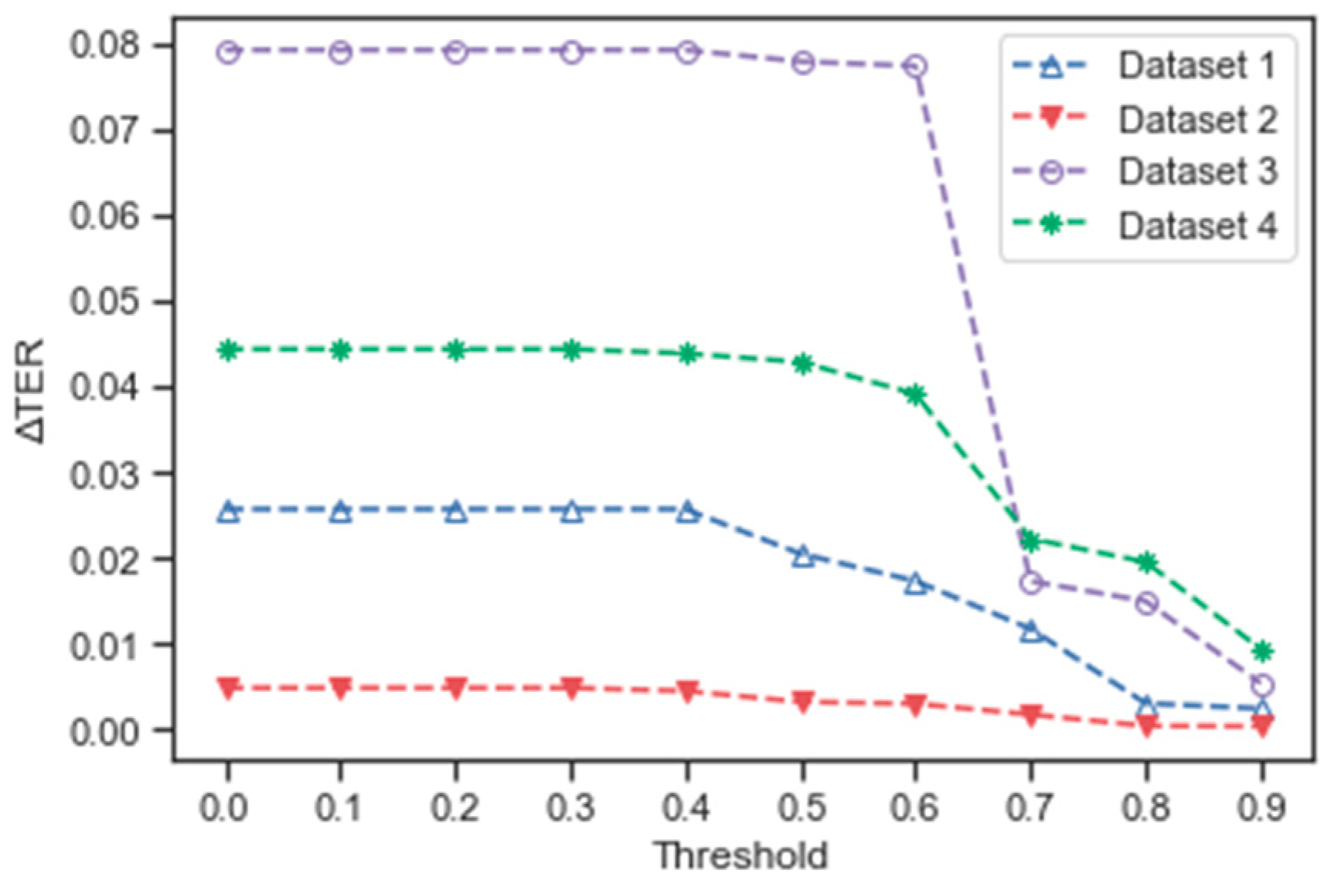

4.3. Effects of Uncertainty on LUC Map Reliability

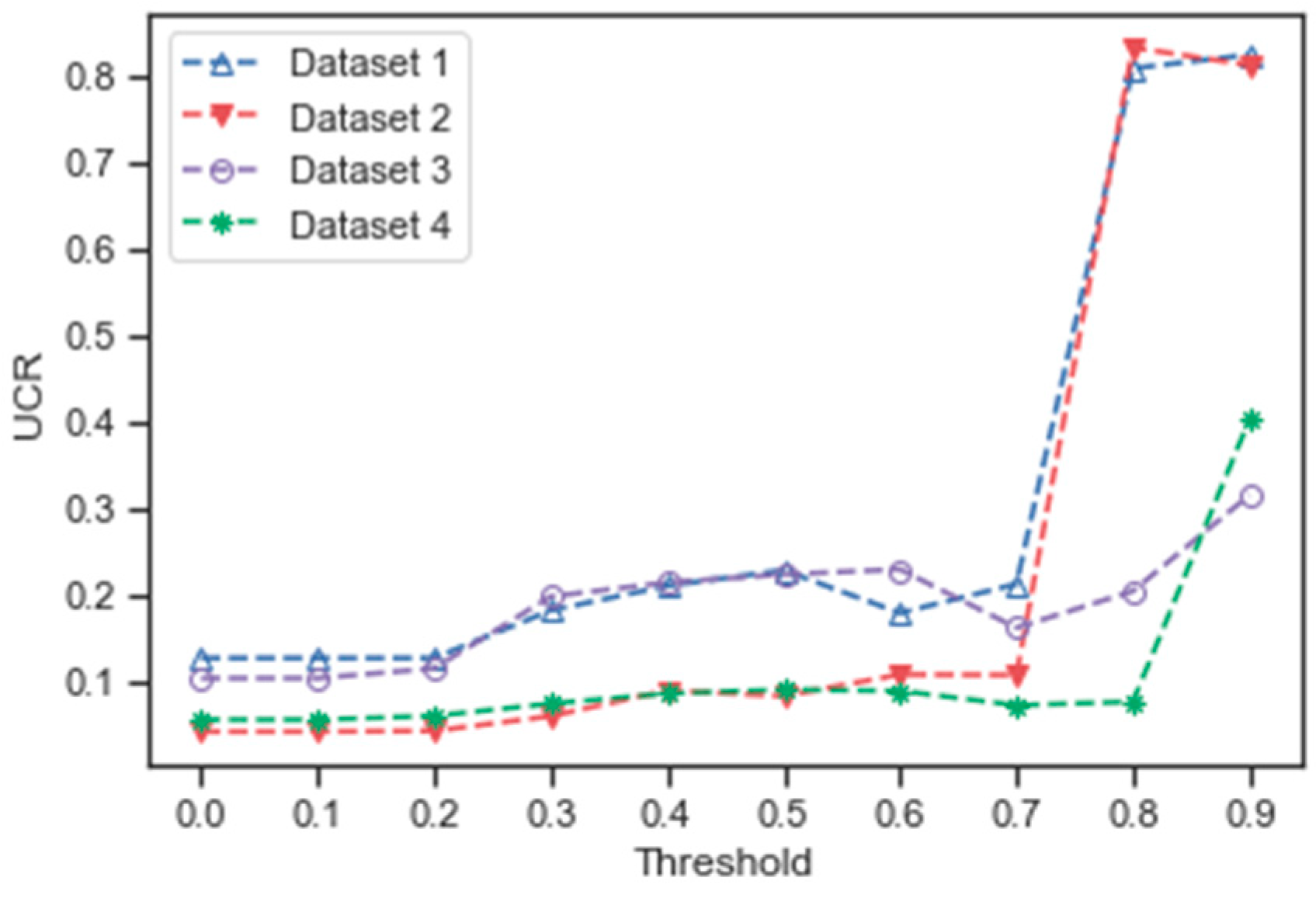

4.4. Uncertainty Control Based on Patch Label Uncertainty

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Foley, J.A.; DeFries, R.; Asner, G.P.; Barford, C.; Bonan, G.; Carpenter, S.R.; Chapin, F.S.; Coe, M.T.; Daily, G.C.; Gibbs, H.K. Global consequences of land use. Science 2005, 309, 570–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Running, S.W.; Nemani, R.R.; Heinsch, F.A.; Zhao, M.; Reeves, M.; Hashimoto, H. A continuous satellite-derived measure of global terrestrial primary production. Bioscience 2004, 54, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambin, E.F.; Turner, B.L.; Geist, H.J.; Agbola, S.B.; Angelsen, A.; Bruce, J.W.; Coomes, O.T.; Dirzo, R.; Fischer, G.; Folke, C. The causes of land-use and land-cover change: Moving beyond the myths. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2001, 11, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foody, G.M. Status of land cover classification accuracy assessment. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 80, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W. Principles of Modeling Uncertainties in Spatial Data and Spatial Analyses; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- McRoberts, R.E.; Stehman, S.V.; Liknes, G.C.; Næsset, E.; Sannier, C.; Walters, B.F. The effects of imperfect reference data on remote sensing-assisted estimators of land cover class proportions. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2018, 142, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, D.; Chun, Y. Spatial autocorrelation and uncertainty associated with remotely-sensed data. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, P. An Uncertainty Descriptor for Quantitative Measurement of the Uncertainty of Remote Sensing Images. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comber, A.; Fisher, P.; Brunsdon, C.; Khmag, A. Spatial analysis of remote sensing image classification accuracy. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 127, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löw, F.; Knöfel, P.; Conrad, C. Analysis of uncertainty in multi-temporal object-based classification. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2015, 105, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofsson, P.; Foody, G.M.; Herold, M.; Stehman, S.V.; Woodcock, C.E.; Wulder, M.A. Good practices for estimating area and assessing accuracy of land change. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 148, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Zhang, X.; Hao, M.; Shao, P.; Cai, L.; Lyu, X. Validation of land cover products using reliability evaluation methods. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 7846–7864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Li, S.; Chen, J.; Zhang, X.; Xu, S. The standardization and harmonization of land cover classification systems towards harmonized datasets: A review. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2017, 6, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsendbazar, N.-E.; De Bruin, S.; Fritz, S.; Herold, M. Spatial accuracy assessment and integration of global land cover datasets. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 15804–15821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, K.; Herold, M.; Hartley, A.; Schmullius, C. Comparative assessment of CORINE2000 and GLC2000: Spatial analysis of land cover data for Europe. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2007, 9, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.C.; Reed, B. A comparison of the IGBP DISCover and University of Maryland 1 km global land cover products. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2000, 21, 1365–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chen, J.; Liao, A.; Cao, X.; Chen, L.; Chen, X.; He, C.; Han, G.; Peng, S.; Lu, M. Global land cover mapping at 30 m resolution: A POK-based operational approach. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2015, 103, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Yang, L.; Zhu, Z.; Homer, C. A land cover change detection and classification protocol for updating Alaska NLCD 2001 to 2011. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 195, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congalton, R.; Gu, J.; Yadav, K.; Thenkabail, P.; Ozdogan, M. Global land cover mapping: A review and uncertainty analysis. Remote Sens. 2014, 6, 12070–12093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herold, M.; Woodcock, C.E.; Di Gregorio, A.; Mayaux, P.; Belward, A.S.; Latham, J.; Schmullius, C.C. A joint initiative for harmonization and validation of land cover datasets. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2006, 44, 1719–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vancutsem, C.; Marinho, E.; Kayitakire, F.; See, L.; Fritz, S. Harmonizing and combining existing land cover/land use datasets for cropland area monitoring at the African continental scale. Remote Sens. 2013, 5, 19–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herold, M.; Mayaux, P.; Woodcock, C.; Baccini, A.; Schmullius, C. Some challenges in global land cover mapping: An assessment of agreement and accuracy in existing 1 km datasets. Remote Sens. Environ. 2008, 112, 2538–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, C.; Zhu, Z.; Reed, B. A comparative analysis of the Global Land Cover 2000 and MODIS land cover data sets. Remote Sens. Environ. 2005, 94, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Hoyos, A.; García-Haro, F.; San-Miguel-Ayanz, J. Conventional and fuzzy comparisons of large scale land cover products: Application to CORINE, GLC2000, MODIS and GlobCover in Europe. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2012, 74, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallum, I.; Obersteiner, M.; Nilsson, S.; Shvidenko, A. A spatial comparison of four satellite derived 1 km global land cover datasets. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2006, 8, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xiao, P.; Feng, X.; Li, H. Accuracy assessment of seven global land cover datasets over China. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2017, 125, 156–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pflugmacher, D.; Krankina, O.N.; Cohen, W.B.; Friedl, M.A.; Sulla-Menashe, D.; Kennedy, R.E.; Nelson, P.; Loboda, T.V.; Kuemmerle, T.; Dyukarev, E. Comparison and assessment of coarse resolution land cover maps for Northern Eurasia. Remote Sens. Environ. 2011, 115, 3539–3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Qiu, P.; Liu, X.; Lu, F.; Wan, B. A holistic approach to aligning geospatial data with multidimensional similarity measuring. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2018, 11, 845–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajbhandari, S.; Aryal, J.; Osborn, J.; Lucieer, A.; Musk, R. Leveraging machine learning to extend Ontology-Driven Geographic Object-Based Image Analysis (O-GEOBIA): A case study in forest-type mapping. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.; Li, H.; Yan, L.; Liu, Z.; Blaschke, T.; Soergel, U. An object-based semantic classification method for high resolution remote sensing imagery using ontology. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, D.; Batet, M.; Isern, D.; Valls, A. Ontology-based semantic similarity: A new feature-based approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2012, 39, 7718–7728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.-C.; Flewelling, D.M. Assessment of semantic similarity between land use/land cover classification systems. Comput. Environ. Urban. Syst. 2004, 28, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlqvist, O. Extending post-classification change detection using semantic similarity metrics to overcome class heterogeneity: A study of 1992 and 2001 US National Land Cover Database changes. Remote Sens. Environ. 2008, 112, 1226–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q. Modelling Semantic Uncertainty of Land Classification System. Ph.D. Thesis, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- CORINE Land Cover—Contents. Available online: http://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/COR0-landcover (accessed on 1 January 1995).

- GLC30 Information Service. Available online: http://www.globallandcover.com (accessed on 21 February 2017).

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhao, X.; Liu, B.; Yi, L.; Zuo, L.; Wen, Q.; Liu, F.; Xu, J.; Hu, S. A 2010 update of National Land Use/Cover Database of China at 1: 100000 scale using medium spatial resolution satellite images. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 149, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tversky, A. Features of similarity. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.E.; Weaver, W. The Mathematical Theory of Communication; University of Illinois Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, M.; Zhan, T.; Zhang, P.; Miao, Q. Superpixel-based difference representation learning for change detection in multispectral remote sensing images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2017, 55, 2658–2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Shi, W.; Liang, P.; Hao, M. Level set evolution with local uncertainty constraints for unsupervised change detection. Remote Sens. Lett. 2017, 8, 811–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Liu, T.; Zhang, P.; Benediktsson, J.A.; Lei, T.; Zhang, X. Novel Adaptive Histogram Trend Similarity Approach for Land Cover Change Detection by Using Bitemporal Very-High-Resolution Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2019, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haralick, R.M.; Shanmugam, K.; Dinstein, I.H. Textural features for image classification. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1973, 610–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, P.; Shi, W.; He, P.; Hao, M.; Zhang, X. Novel approach to unsupervised change detection based on a robust semi-supervised FCM clustering algorithm. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krinidis, S.; Chatzis, V. A robust fuzzy local information C-means clustering algorithm. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2010, 19, 1328–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| AT (km2) | AU (km2) | AE (km2) | TER | UCR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dataset 1 | 178.99 | 36.39 | 4.60 | 2.57% | 12.64% |

| Dataset 2 | 341.01 | 39.89 | 1.65 | 0.48% | 4.13% |

| Dataset 3 | 4605.22 | 3702.00 | 365.19 | 7.93% | 10.31% |

| Dataset 4 | 4603.84 | 4280.80 | 204.30 | 4.44% | 5.52% |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, X.; Shi, W.; Lv, Z. Uncertainty Assessment in Multitemporal Land Use/Cover Mapping with Classification System Semantic Heterogeneity. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2509. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11212509

Zhang X, Shi W, Lv Z. Uncertainty Assessment in Multitemporal Land Use/Cover Mapping with Classification System Semantic Heterogeneity. Remote Sensing. 2019; 11(21):2509. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11212509

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Xiaokang, Wenzhong Shi, and Zhiyong Lv. 2019. "Uncertainty Assessment in Multitemporal Land Use/Cover Mapping with Classification System Semantic Heterogeneity" Remote Sensing 11, no. 21: 2509. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11212509

APA StyleZhang, X., Shi, W., & Lv, Z. (2019). Uncertainty Assessment in Multitemporal Land Use/Cover Mapping with Classification System Semantic Heterogeneity. Remote Sensing, 11(21), 2509. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11212509