Abstract

The first grassroots initiatives for renewable energy in The Netherlands were a small number of wind cooperatives that developed in the 1980s and 1990s. After a few years without developments, new initiatives started emerging after 2000, and after 2009 the movement boomed, growing from around 40 to over 360 initiatives. These initiatives form an active, large and diverse movement that uses various motivations, technologies and connections, which have changed over time. This article uses a mixed methodology, aiming to map the development of these different “waves of initiatives” and relate them to the way in which the initiatives fit with their institutional environment. Institutional changes—such as the liberalization of the energy market, changing energy policies and discourses and a policy field that became increasingly multi-actor and multi-level—have influenced the presence and activities of grassroots initiatives. The article concludes that the growth and increasing visibility of the movement can be attributed to a large institutional fit at the decentral level, but that the low priority for grassroots initiatives and the economic rationale of the national government have hindered the political influence and installed capacity of renewable energy production facilities of the initiatives.

1. Introduction

1.1. Institutionalization of Grassroots Initiatives

There is a seeming asymmetry between the recent rapid growth of Dutch grassroots initiatives for renewable energy and the apparent lack of responsiveness from the institutional environment in which they develop, especially at the national administrative level. From 2009 to 2016, the number of grassroots initiatives (GIs) grew from around 40 to over 360 [1] and they seem to provide an opportunity for local renewable energy that is community organized and financed and has a high local acceptance. Despite this potential, few (national) rules, subsidies or other support measures are targeted towards GIs. The aim of this research is to analyze the development of the GIs movement in relation to its policy environment. This prompts two research questions, one empirical and one analytical: how did the movement of GIs in The Netherlands develop, and how and why has this movement become (limitedly) institutionalized in the Dutch (renewable) energy policy domain? Answering these questions reveals if and how the observed asymmetry occurs in practice and how this affects the development of the movement of GIs: findings that are placed in the academic debate on the (innovative) potential of GIs.

Overlooking the GIs movement is all too easy for the Dutch government: GIs form a heterogeneous group of initiatives with various scales, activities and degrees of professionalism, but with a typically modest aim and local focus. Turning to the larger players in the system is claimed to have the advantage for the central government of dealing with lower-risk and higher-impact projects [2,3], but the dependence of the incumbents on fossil fuels and cheap electricity hinders a radically new or innovative approach to energy and could slow down the transition. Bottom-up initiatives could provide a valuable testing ground for technological and governance innovations [4] and could provide legitimacy and reduce NIMBY reactions [5]. In addition, a focus on large scale production does not facilitate a role for individual homeowners and energy consumers, who can have a significant impact: individual citizens and community projects for example account for a large share of the installed RE capacity in Germany, one of the energy transition leaders in Europe [6]. A decentralized and diversified policy could create an environment in which GIs could positively influence the energy transition.

1.2. Main Concepts

The concept “grassroots initiative” is based on the grassroots innovations literature, which defines grassroots innovations as “networks of activists and organizations generating novel bottom-up solutions for sustainable development; solutions that respond to the local situation and the interests and values of the communities involved” [7,8]. We prefer the term grassroots initiative over innovation in order to include all bottom-up alternatives for local sustainability, including those that are innovative in the sense of shifting ownership and roles of citizens rather than through the use of technological innovations [7]. We define grassroots initiatives for renewable energy as local, bottom-up collaborations between citizens, motivated by the desire to supply or produce renewable energy on a local scale. This refers to a broad category of organizations and projects with a wide range of participation modes such as initiation, administration, management and (co-)ownership of projects [9]. Initiatives may consist of larger or smaller groups of citizens, local farmers or businesses, or more well-established NGOs taking up renewable energy. Although cooperatives are the most well-known organizational form, more informal, businesslike or other organizational types also occur [10]. Research has also identified GIs as community initiatives, civic initiatives, bottom up projects or local renewable energy companies [1,10,11] and includes accounts on the growth and variety of the phenomenon [11], their contribution to the renewable energy transition [12,13] and their innovative potential [7]. This study aims to contribute to the debate on the potential of GIs through an institutional approach.

GIs can be viewed as a “movement” in the sense that they form an informal network between a plurality of groups and organizations, which are active within the renewable energy domain based on their shared value of local, renewable energy provision and the dissatisfaction with this provision by the government. The growth of the movement refers both to the increased numbers of GIs and to the strengthening of their network. The institutionalization of GIs refers to the process in which new actors become embedded in the structure and discourse of a policy field: through repeated interactions between new actors and the established actors, rules and ideas present in the policy field, new actors may become part of the policy making processes and the game of distribution of resources, and may find legitimacy for their position [14].

The process of development and institutionalization of GIs exemplifies a social and organizational innovation in the energy sector, in which the sector becomes multi-actor and decentralized and citizens move beyond their role of consumers to become players in the decision making and production process. The process of institutional embedment of this innovation is a regulatory response of the institutional system. Hence, this research contributes to the topic of the Special Issue “Innovation in the European Energy Sector and Regulatory Responses to It” of the journal Sustainability, by providing an example of the regulatory response of institutionalization to a social innovation.

1.3. Grassroots Initiatives in The Netherlands

In the past six years, GIs went from being virtually absent in the Dutch energy scene to being present in almost every municipality and increasingly visible and influential as a movement. Although a handful of GIs emerged in the 1970s, the current landscape of GIs for renewable energy in The Netherlands consists of at least 360 formalized GIs [1], over 75% of which have been established after 2008.

The growth of the GIs movement takes place in a strongly fossil fuel oriented energy system that faces the challenge of a renewable energy transition. The 2016 Dutch electricity production is for 50.1% based on coal and for 37.2% on natural gas, with a 5.8% share of renewable energy (RE) [15]. In order to comply with the European targets for reduction of CO2 emissions, the renewable energy share should rise to 16% by 2023 [16]. GIs, with their focus on local renewable electricity production, could be potentially interesting partners for the government. However, the government takes a centralized approach, focusing on large scale projects with high installed capacities, such as offshore wind projects [16,17]. The 2013 Energy Agreement has a modest focus on decentralization and inclusion in designing policies, but most of the current measures are aimed at larger companies and investors and the current incumbents (e.g., through subsidizing biomass co-combustion) [3]. Commenting on this, an interviewee from The Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency remarks that the national government engages in a variety of partnerships with the traditional energy sector, grid operators, market parties and regional and local government, but has relatively little attention for the many small, local and citizen-led projects that have emerged in the past decade.

1.4. Literature Review on Dutch Grassroots Initiatives

To describe and interpret the broad history of Dutch GIs is a novel approach: academic accounts on the Dutch situation up until now consist of single and comparative case studies, mostly of frontrunners that provide insights in innovations among GIs but do not represent the movement as a whole. This section provides a literature review of these studies.

Van der Schoor and Scholtens (2015) and Hufen and Koppejan (2015) both aim at understanding the role and contribution of GIs in the renewable energy transition [18,19]. Van der Schoor and Scholtens compare 13 cases in the north of The Netherlands between 2010 and 2013, and conclude that these GIs were still developing and relatively young, but that formalizing the initiative strengthened their position and internal organization. They also observe an increase in regional umbrella organizations, such as the GrEK in Groningen province [18]. Hufen and Koppejan study four frontrunner GIs: Deltawind, Texel Energie, Grunneger Power and Lochem Energy. They conclude that wind cooperatives have a strong potential to contribute to the RE transition because of their unique local situation, but that GIs that are not solely focused on wind have little potential, due to relatively expensive “green” energy and scarce possibilities for RE production [19].

Hoppe et al. (2015) compare two successful Local Energy Initiatives, Lochem Energy (in The Netherlands) and Saerbeck (Germany), focusing on motivations, visions, actors and networks, and learning. They highlight the importance of the role of networking, dealing with expectations, facilitating community learning, leadership and process management of public officials [20]. Warbroek and Hoppe (2017) focus on the response of local and regional authorities to the emergence of local low-carbon energy initiatives in the provinces of Overijssel and Friesland. These cases are directed towards policy innovation and institutional adaptation, and the results show that the regional authorities govern through enabling, whereas the local governments’ modes of governing are more of an ad hoc and incremental in nature [21].

De Boer and Zuidema (2015) develop an “integrated energy landscape” to conceptualize the intertwining of physical and socio-economic elements of the energy system. The integrated approach aids spatial planners and policy makers in their understanding of the contributions of energy initiatives in the light of an energy transition [22].

The study of De Vries et al. (2016) is dedicated to civic energy communities (CEC) and qualitatively explores five “best practice cases”, being CALorie, Morgen Groene Energie, Hilverstroom, Lochem Energie and Duurzaam Hoonhorst. The case studies focus on the role of users in (technological) innovation practices, and reveal that existing technologies are gradually implemented into existing configurations in a community learning process. Particularly, the learning process adds to the network building of the community with external parties, which opens up different resources and other networks [23].

These case studies provide valuable information on local cases within their context, but as most of the above scholars acknowledge, they only provide specific knowledge on particular cases, which cannot easily be transferred towards other cases. In addition, the majority of studies are dedicated to best practices or frontrunners within the GI movement. Consequently, a more complete picture of the GIs in The Netherlands is lacking. This paper aims to provide a more generic overview, contributing to the understanding of GIs in The Netherlands through collecting and analyzing GIs, their history, goals, activities and partnerships.

1.5. An Institutional Approach

The development of GIs in the Dutch energy policy system can be viewed as a process of institutionalization: the translation from local niche experiments into concrete changes in the energy policy system. This process of institutionalization of new actors can be hindered by vested interests and institutional obstacles, which preserve the status quo and favor unimaginative innovations and incremental changes [24]: “while not monolithic, omnipresent or immutable, institutions can only rarely be avoided, modified, or replaced without a considerable degree of effort” [25]. The development of GIs can be viewed as an interactive process in which a certain degree of institutionalization enables further development of the movement, which then increases their potential to instigate change and reduce the institutional obstacles that hinder their development.

We view the energy system as an institutional system, defining institutions as “the formal or informal procedures, routines, norms and conventions embedded in the organizational structure of the polity or political economy” [26] (p. 938). The changes and institutionalization processes of GIs in that system are mapped using the policy arrangements approach (PAA) and the concept of institutional fit. The PAA is an institutional approach to map specific policy systems such as the energy policy system, through analyzing four interrelated dimensions of the system: the (coalitions of) actors, the formal and informal rules, the distribution of resources such as funds and knowledge, and the discourses, relating to the multiple ideas and frames in the system and their relative dominance [14,26]. Each of these dimensions can be both a source or a hindrance for change processes, and, likewise, each of these dimensions can provide opportunities or hindrances for the institutionalization of GIs, i.e., the process in which they become embedded in each dimension of the system.

The way in which each dimension creates opportunities or hindrances for GIs to access the system is described as “institutional fit”, which can be defined as the congruence between GIs and the institutional system, stemming from the idea that local initiatives are only able to emerge when institutions do not create insuperable barriers [27,28]. This fit is a dynamic process of mutual adjustment between GIs and the arrangement [29] and can be operationalized in the four dimensions of the PAA. In the dimension of actors, the ability of GIs to form coalitions and collaborations with others is referred to as relational fit. The access to resources is referred to as distributive fit. Third, regulatory fit refers to the options or limits posed by the rules in the system. Lastly, discursive fit is the alignment of the ideas and values of GIs with those of other actors, which can be a basis for collaboration [30]. This includes ideas on renewable energy or e.g., environmental considerations, but also includes ideas on the legitimacy of GIs as actors in the energy system. Thus, fit in one dimension influences the opportunities and constraints in other dimensions. Institutional fit is constantly created, recreated and altered in a dynamic interaction between GIs and their environment and through the dynamics within the system itself, and GIs need a certain amount of fit in order to successfully expand beyond their first niche activities [31].

2. Materials and Methods

The research uses a mixed method based on quantitative data of 360 GIs, in order to present a broad overview of the movement. The GIs were identified using data from umbrella organizations HIER Opgewekt (Produced HERE) and ODE Decentraal (Organization for Decentral Renewable Energy), the Lokale Energie Monitor (Local Energy Monitor) report [1] and membership data of decentral umbrella organizations such as the Provincial umbrellas of Gelderland and Noord-Brabant. Data on these initiatives were gathered using a web-search of the websites of GIs and media coverage of the GIs. The method of web analysis was chosen in order not to overburden the volunteers engaged in GI projects. The data collection included around 60 questions on themes such as the contact details of the organization; their goals; the location, technology, capacity, planning and progress of projects; activities not aimed at production, partnerships, alliances and memberships; publicity; and innovations.

The database was analyzed using basic statistical techniques, which led to the identification of the four “waves” of development of GIs. The network analysis is based on membership data of the national and decentral umbrella organizations and data on formal collaborations found through the web search. This was supplemented with qualitative data from the interviews and informal contacts with the umbrella organizations.

The “waves of development” were studied in more detail using qualitative data on the institutional context of initiatives, such as content analysis of policy documents of European, national and local energy policy and media coverage of GIs and energy policy, all referred to in the text. In addition, we conducted over 30 interviews and informal meetings with representatives from the umbrella groups ODE Decentraal and HIER Opgewekt, (local) policy makers, representatives of energy producers and grid operators and initiators of GIs. The interviews were semi-structured and contained questions on the interplay between GIs and actors in their environment, and topics also covered in the database. Summaries of the interviews were used to identify instances of (lacking) institutional fit.

3. Results

3.1. The History of Dutch Grassroots Initiatives: A Development in Waves

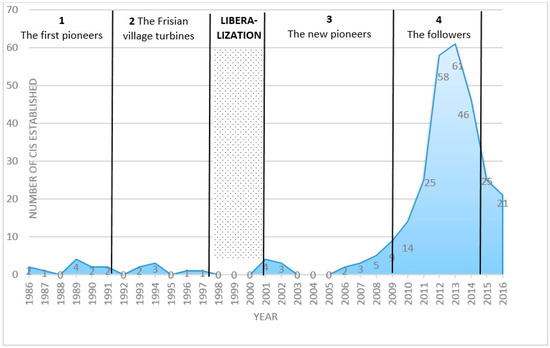

Our 2016 database identifies 360 GIs in The Netherlands, which form a diverse group of well-established cooperatives that produce or sell electricity, as well as new initiatives in the process of establishing their internal organization and formulating RE goals. An overview of the “birth” of the initiatives displays a pattern in different waves (see Figure 1). These waves become even more apparent if one looks at the “signature” of the initiatives. Each wave has its own distinguished type of GIs in terms of the core motivations, activities and technologies of the GIs and their interaction with their institutional environment.

Figure 1.

Number of Dutch grassroots initiatives for renewable energy established per year (own data).

The first community wind cooperative was established in 1985 and was rooted in the anti-nuclear movement. In the early years of GIs, we see some pioneers in different provinces (wave 1) followed by some more wind cooperatives in Friesland province (wave 2). These waves remained modest and their development stopped during the process of liberalization of the energy market. A few years later, new pioneer emerge (wave 3) followed by the large growth in numbers that prompted this research (wave 4). After 2014 the numbers of newly established GIs seem to drop. The development pattern that Figure 1 displays is described below and explained through the institutional fit of the emerging GIs with their environment.

3.2. The Seedbed for GIs in the 1970s–1980s

The seedbed for the first GIs lies in the 1970s, when the oil crises and anti-nuclear protests challenged the national government’s approach to energy. Previously, the energy sector had been monopolized and based on imported oil and coal and on domestic natural gas, the latter of which was quickly rolled out after the discovery of the Dutch gas reserves in Slochteren in 1959. Grid ownership and production was divided into regional monopolies of private companies, with provinces and municipalities as their majority shareholders. Energy policy was based only on economic considerations [32,33], which included large gas revenues that the state received. In the 1970s, the passive and economic approach of the government met with increasing societal opposition. The oil crises created awareness of the dependency on oil producing and the government’s discourse of utility maximization was challenged after publication of the 1972 “Limits to Growth” report [34].

A second discursive challenge was formed by the fierce anti-nuclear protests. As a strategy to increase energy independence and thus secure energy supply, the government invested in nuclear power, but this led to ongoing and large protests. Despite the public opposition, the government did not abandon its nuclear strategy until the 1986 Chernobyl disaster, which left nuclear power politically unviable. However, the protests installed in community members the notion that energy policy could be contested and that communities could undertake action.

The first community action in the energy field thus emerged out of dissatisfaction with governmental energy policy. Communities and individuals started experimenting with alternatives such as private wind turbines. In broader innovative experiments, such as “De Kleine Aarde” (The Small Earth, est. 1972), community groups experimented with more sustainable and environmentally friendly living, energy and food production [34]. However, these initiatives were met with a complete lack of regulatory fit: decentral grid access was prohibited, which rendered real GI activities in the energy field impossible.

The government started basing its policies on a broader discourse on energy that included energy security issues and environmental considerations [35], and the first RE policy dates from 1979 (the Second White Paper on Energy [36]). It envisioned only a modest role for RE, but enabled decentral grid access in 1980 with the aim to enable farmers to produce local energy and break the local utility monopolies, that had grown into a “cartel” and were united in the influential umbrella organization SEP. The monopolized market created little fit for new entrants, but the new decentral grid access formed a regulatory option that aligned with the discourse of local community action.

3.3. The First Wave: Pioneer Wind Cooperatives in 1985–1991

Despite the limited fit in the actor coalition and the unfavorable rules, a small number of pioneers started experimenting with individually owned small turbines, and united themselves in umbrella organization ODE (Organization for Renewable Energy). ODE started in 1979 as a network for “do-it-yourself turbine builders” and grew to become the umbrella organization for GIs for renewable energy. A small number of private turbines emerged, mostly owned by farmers as the costs were too high for other citizens. Soon, these wind power pioneers realized that citizen ownership was more feasible if organized through a cooperative or legal association that would pool their (financial and knowledge) resources. The first cooperatives were formed in the early 1980s to plan collectively owned and operated turbines, and in 1987 the first turbine was erected in Delft by the Cooperative Turbine Association Delft (Coöperatieve Windmolen Vereniging Delft).

Connected through ODE and inspired by initial successes, 25 wind cooperatives emerged in a time span of only five years, mostly in locations with available land and high wind potential [37] (see Figure 2). These GIs are all bottom-up, civil initiatives, although a few collaborated with farmers for e.g., access to land. This development took place outside of the political realm and even though the pioneers were inspired by the anti-nuclear movement, they did not seek political influence or actively challenge the arrangement. These GIs typically exploited (and often still exploit) a small number of local wind turbines and acted on a discourse that combined environmental concerns with a wish for local independence. The turbines are financed through shares upon which members receive interest. Unable to obtain a supplier permit, cooperatives sold their product to large suppliers and the cooperative’s members received interest over their shares. This business model was supported through the 1989 Electricity Act, which obliged energy suppliers to buy decentrally produced electricity for a standard price and guaranteed grid access [37] (p. 216). The main focus of the Act was to break the regional monopolies by introducing some competition, and stimulate unbundling of production and supply [38]. However, the intended competition remained weak as the SEP turned out to function as a cartel [38]. The grid access and price guarantees, originally meant for farmers and small businesses, increased the regulatory and distributive fit for GIs.

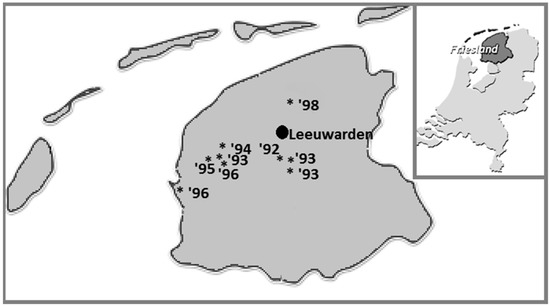

Figure 2.

Geographical distribution and year of founding of wave 1 wind cooperatives. Data from Agterbosch [37] (p. 216).

Although these GIs were successful in their plans, the movement barely expanded in the 1990s and remained of little influence to policy makers. In the late 1990s the movement had around 2000 (mostly passive) members but was not seen as very influential or promising: “this phenomenon would not really take off. The cooperative idea, that can be found in agriculture, is a lot weaker than in Denmark, and in the 1980s the electricity sector formed a mighty lobby that was not very fond of decentralized production of electricity” [28] (p. 98). Nobody expected the citizens movement to expand the way it did later. The GIs themselves had fulfilled their own ambitions and did not intend to grow or expand their activities.

What stands out is that for these first wave GIs, the hypothesis that actors would seek to change their institutional environment and increase their position does apply. On the contrary, GIs found a niche in the sector and tailored their activities to fit within the possibilities. Institutional support was limited, although the 1989 Electricity Act provided some favorable regulations. The modest tariffs and profits however kept the activities reserved for environmental activists, although the profitability increased somewhat in the early 1990s. The government did not perceive GIs as a viable alternative and worked primarily with the established electricity sector, excluding GIs from political decision making (which they in turn did not seek). Moreover, the system indeed proved quite resistant to change, including to decentralization and to the introduction of competition and unbundling in the electricity sector. The system did not offer much relational or distributive fit for GIs, but the regulatory fit had improved somewhat through the decentral grid access and guaranteed prices. Lastly, the ongoing economic rationale of the government did not align with the environmental and local discourse of GIs.

3.4. The Second Wave: The Frisian Village Turbines in 1991–1997

The emergence of the second wave illustrates the importance of institutional fit at a decentral level. Where the momentum for GIs at the national level was small, nine village wind cooperatives emerged in Friesland province, with a rationale that was quite different from the first GIs (see Figure 3). These turbines, erected between 1991 and 1997, were built by local village interest groups (some in collaboration with commercial project developers) not out of environmental concerns but also with the purpose of generating profits for the local community [39]. This was successful: over the years, the village turbines in Friesland invested revenue from the turbines in local football clubs, church restorations, village fairs and more, also including other RE measures, such as solar panels on local schools [40]. The goal of these associations was to enhance the quality of living in small, rural villages and the exploitation of the turbines is seen as a means to create revenue to invest locally.

Figure 3.

Geographical distribution and year of founding of wave 2 Frisian village wind cooperatives (own data).

The success of the Frisian turbines can be explained by large institutional fit and the absence of unsurpassable thresholds in each of the dimensions of the arrangement. The villages built a discourse coalition with the province and municipalities based on the shared aim of revitalizing the community, which was perceived as a legitimate and high priority aim. Based on this discursive and relational fit, the province made resources available and the collaboration with the province convinced local banks to contribute, creating distributive fit at the local level. Lastly, the rules that needed to be complied with were suitable for local wind projects, as the laws under which the first wave of GIs had developed were not altered. More than this local institutional fit, the GIs also benefited from some favorable local circumstances outside of the energy policy arrangement. The projects benefited from the tightness of the small, local communities in these villages, which are remote rural areas in which people know and trust each other. The local community had faith in the initiators and because revenues were invested in collective goods, the public acceptance of the turbines was very high. The turbine in Reduzum is for example lovingly called “us mûne” (our mill) by the local people [40]. Moreover, a local learning effect occurred in which one village was inspired by a turbine in a neighboring village, and local learning took place, allowing for access to knowledge as a resource. Lastly, the initiators felt a high urgency to act because the villages faced poverty and depopulation, often leading to the termination of local facilities such as schools and libraries. Through the revenues of the turbines, these facilities could remain open, which was a strong motivation for the initiators [41].

At the national level the institutional fit for GIs was still small. In reaction to the 1986 Chernobyl disaster and the 1987 Brundtland report, sustainable development was put on the national policy agenda and brought about an environmental discourse that was further strengthened by the founding of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) by the United Nations in 1988. These international ambitions translated into Dutch policy documents such as the 1989 National Environmental Policy Plan (NMP) that encouraged recycling and energy efficiency [42]. The first wind plan was presented in 1991 and included goals and liberties for the seven Dutch provinces with the highest wind potential. This plan lacked a reinforcement mechanism though, and, from the aimed 1000 MW, only 437 MW was realized by 2000. This increase in discursive fit for GIs did not translate into opportunities in the actor constellation, as the national government partnered mostly with the SEP, which had merged into four large regional distribution monopolists [36]. Provinces and municipalities had large financial interests in the SEP but little control, and the national government had few steering mechanisms and “struggled with the climate targets” [28] (p. 119). It was unclear which climate models should be followed, and economic growth and energy use reduction seemed impossible to reconcile. Here, the old and new energy discourses collided, and the economic considerations and lobby proved to be persistent: the government was hesitant to implement measures that would harm industrial development. The search for appropriate policy strategies was appointed to the Exploration Committee Energy Research, which fittingly called its 1996 report “Search for directions in a maze”. In 1996, the government established the aim to achieve a 10% share of RE by 2020 [43] and sought collaboration with the market, mostly because a new, major complication had been added to the already complex sector: the EU plan to liberalize the energy market.

3.5. Intermezzo: Liberalization of the Energy Market

The liberalization of the Dutch energy market was a transformative process that changed all dimensions of the arrangement through a very non-transparent and messy process, in other words: “it led to a complete tilt in the energy sector, with new power relations, new players, and above all large insecurity about the future for all involved parties” [34] (p. 114). This insecurity had a disruptive short-term impact on the developments of renewable energy in general and the involvement of GIs: actors waited until the dust settled. Agterbosch characterizes this era, starting with the first preparations in 1996, as an “interbellum” in which the monopoly powers were awaiting what would happen and the free market was not yet in place [37] (p. 233). The process was shaped through a series of laws and White Papers, culminating in the 2004 free market for consumers and with some processes such as unbundling still ongoing.

The new situation of the liberalized market was a new “playing field” for GIs. The actor constellation became more internationally oriented, as the former SEP members could not compete with international energy conglomerates and were taken over (e.g., Nuon became part of Vattenfall and Essent was bought by German energy company RWE). A few years into the liberal market, small market players started to emerge with a distinct “green” signature, such as Greenchoice, Huismerk and VandeBron. For GIs, this provided more fit for collaboration than the international energy giants, which have little interest in non-market players and in the local level. The resource distribution also provides little fit: a liberalized market is characterized by competition and the potential of GIs to compete with more professional companies is limited. Lastly, the discourse became more market oriented, but environmental concerns appeared as a form of “branding” of some of the new companies, which offered discursive fit for GIs.

Domestic renewable energy production suffered under the liberalization. The chances for economically unviable technologies are small in an open market, which hinders experimentation. Moreover, increased international competition and international trade of green energy certificates led to large competition from, e.g., cheap Nordic hydropower. RE projects require relatively high investments and have long timeframes for return of investment [37]. Since open markets have a tendency to favor short payback times and low prices over longer (more sustainable) investments, RE was not commercially interesting [44].

Because of the high instability and unpredictability of the energy system during liberalization, GIs were notably absent. It was very unclear for GIs—and other investors—how the future would unfold, which caused actors to wait. The first two waves of GIs had been building wind turbines, something that requires a long time frame and future outlook. It is not surprising that the first GIs to emerge after the liberalization sought other, more easily attainable activities and technologies than wind power. Driven by a mix of dissatisfaction with the energy market, environmental concerns and financial motives, the first new citizens’ activities for RE started to emerge a few years after the liberalization was introduced.

3.6. The Third Wave: The New Pioneers in 2000–2008

In the liberalized market, the Dutch government embraced the RE transition as a policy goal, but through a broad and inconsistent approach. A series of experiments, subsidies, pilot projects and policy platforms occurred, but because of the many changes in government and the novelty of the RE challenge in a liberalized market, there was very little continuity and the investment climate was uncertain. For example, the 2003 MEP subsidy for RE projects was very popular but had to be capped when it became too costly. The overall energy policies in these years have been characterized as “jiggling” and a lack of continuity in policy aims, rules and subsidies and fuzzy distribution of roles and responsibilities [45] have “caused The Netherlands to be lagging behind [in the RE transition] for years” [46]. Still, some of the goals were reached, such as the Kyoto protocol goals (through emissions trading) and the goals for offshore wind that were set for 2010, but the share of RE remained negligible. In 2008, net metering became allowed for private households, which strongly stimulated investment in solar panels, and a new subsidy called SDE (Incentive Renewable Energy) became available for (GIs) energy projects.

The dominant discourse on energy policy of the national government was an ongoing difficult compromise between economic and environmental sustainability concerns, in which climate change concerns emerged as a new layer that was introduced through e.g., the “Stern Review on the Economic Impact on Climate Change” (2006), the IPCC reports on global warming (e.g., 2007) and Al Gore’s documentary “An Inconvenient Truth” (2006). The coupling of energy with anthropogenic climate change created momentum for RE in the national government. Locally, RE gained momentum as a method for branding, for example as “energy smart city” or “transition town”. This discursive fit for RE led to local awareness and budget for RE measures such as subsidies, local smart grids and heat pumps: in other words it created local distributive and regulatory fit.

In this institutional environment, which was still unpredictable but in which the RE transition gained discursive legitimacy, a group of new GIs emerged from broader NGOs and initiatives from adjacent fields such as neighborhood development, housing construction and existing collaborations between farmers and their neighbors. For example, the first collective solar roofs were developed in 2006 through Project “Farmer Seeks Neighbor” in which local people gave loans on solar panels to a local farmer, and received interest from the profits. In 2006 foundation Urgenda (urgent agenda) was founded by two Rotterdam academics, who presented an action agenda to become climate neutral by 2030. Another example, pioneer Kroetenwind, was established in 2002 in order to make a local newly built neighborhood in Breda sustainable through compulsory membership of all new plot owners. Similarly, projects emerged on business campuses (e.g., Bedrijvenpark Twentekanaal). Inspired by these new pioneers and by international examples such as the Danish island Samsø that appeared in the Dutch media, a new type of actor emerged: the broad energy cooperative. “New style” cooperatives such as Meewind, Texel Energie, AEC and Duurzaam Zwolle were founded in 2006–2009 and had a broad agenda for sustainability and a local approach, inspired by their predecessors like Urgenda.

These new GIs started with a much broader range of activities than the classical wind cooperatives, opting for less high risk and complex activities, and for more visible short-term results. These activities include resale of green electricity and collective purchase of privately owned solar panels and providing members with information about energy savings and production. In 2006, Urgenda was the first organization to organize a collective purchase for solar panels called We Want Solar (Wij Willen Zon), and the price of PV, which had already been declining due to (Chinese) technological improvements and increased production, dropped further because of the collective shipments and the success of the activity, which sold 50,000 panels to households between 2006 and 2010 and was repeated by other organizations. Another activity that quickly became popular was resale of green electricity, a white label construct through which local GIs offer RE supply, using the back office and supplier permit of a larger, for-profit RE supplier Consumers would buy e.g., ‘Grunneger Power’ that would be delivered through Greenchoice. This local branding of renewable energy made consumers enthusiastic, and the cooperative gained some profits from the resale. From these low hanging fruits, many GIs developed towards broader and more ambitious projects, whereas others were happy with modest activities. Organizing collectively owned production was now no longer the initial goal of a GI, but becomes a final activity which some would never (attempt to) reach.

These new and innovative activities are enabled by the dropping prices of solar panels and the net metering rules, but the creativity that GIs display also stems from a poor fit with the institutional arrangement. Even though innovation and a broad approach are beneficial for GIs, the system was too inscrutable and unstable for GIs to develop in the traditional fashion. The lack of regulatory and distributive fit stems partly from the inaccessibility of the energy system and the difficulty in obtaining permits and finances, but mostly from the unpredictability of the system, causing GIs to display risk averse behavior.

3.7. The Fourth Wave: Large Numbers of Followers in 2009–2015

Starting in 2009, the GIs movement grew from around 40 initiatives to over 360 initiatives, which were enabled by a liberalized market and net metering, and inspired by the new activities of the third wave pioneers. Our survey identified 360 GIs, including 185 cooperatives, 41 foundations, 21 associations, and many GIs in the process of formal registration. Combinations of legal forms also occur, e.g., cooperatives start a separate foundation for the development of a production facility. There are both rural and urban GIs, although the majority is situated in more densely populated areas. This section looks in more detail at the institutional setting of these new GIs and at their identity: their motivations, activities, and network connections.

3.7.1. Institutional Setting

The boom of GIs does not coincide with a better institutional fit, on the contrary: since 2010, the Dutch government cut down on investments for RE and implemented a retrenchment of R&D for innovation and subsidies for unprofitable projects or technologies, focusing only on large market parties and proven technologies. This largely reduced distributive fit for GIs and also questioned their legitimacy as small actors were not deemed relevant.

Current energy policies took shape in the 2013 Energy Agreement, which was designed by the national government, employers, business representatives and environmental groups. Despite this broad basis, the Agreement focuses on the economic attainability of the energy transition and discusses activities and goals in terms of employment opportunities, payback times and smart investments [3]. The same focus is visible in the 2016 Energy Agenda, designed in reaction to the 2015 Paris Agreement. The Agenda was based on a series of debates (the Energy Dialogue) in which GIs were present, but the outcomes do not facilitate GIs. The urgency and necessity to stimulate the energy transition remain strongly framed in terms of economic benefits and compliance to international agreements, with climate change as a less dominant argument. The ambition is summarized as “CO2 low, safe, reliable, and affordable” [47]. This does not reflect the discourse of local action, inclusion and environmental concerns that GIs value. GIs were mentioned implicitly in the Energy Agenda, but only for their symbolic value and not their potential: “locally produced renewable energy is more expensive and less cost efficient than large scale renewable energy production. Despite this, the Cabinet still supports the development of local renewable energy, because of its contribution to the societal awareness and public support for the energy transition” [47]. The support of the Cabinet mostly means that GIs are not prohibited, but there are no measures to stimulate local RE in the Energy Agenda.

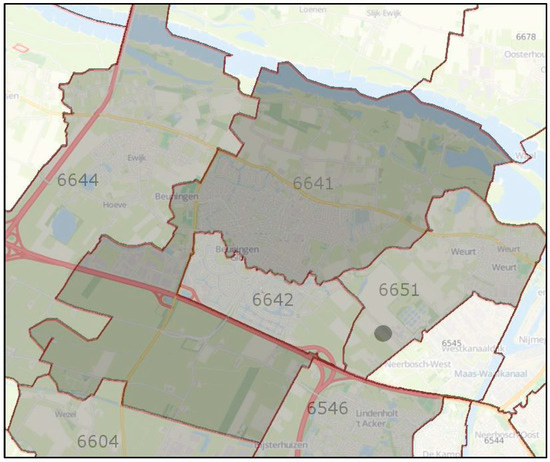

In the current Energy Agreement, one policy measure is directed towards GIs: the so-called “zipcode rose project”, a case of distant net metering in which energy consumers get an energy tax deduction for the amount of energy they produce in a collective project (usually a solar roof), situated in their zipcode area or an adjacent area (hence the “rose” name, see Figure 4). At first, the energy tax system made the projects unprofitable, but a heavy lobby of GIs interest groups finally resulted in an altered taxation. Despite the still modest profits, 38 zipcode rose projects were realized in 2016. Larger projects rather opt for a more profitable subsidy for RE that is targeted to companies (the so-called SDE+ subsidy), but this more difficult to obtain. The successful lobby and the inclusion of a policy measure for GIs demonstrate that some institutionalization did take place: the movement was able to push its political agenda and was included in the actor coalition for decision making and in the resource distribution. At the same time, the derogatory tone of the Energy Agenda displays that GIs lack discursive fit and are not seen as valuable contributors to the energy transition.

Figure 4.

Zipcode rose project of NovioVolta, Beuningen. The heart of the rose is the dark region, the adjacent grey regions can also participate. Provided by NovioVolta respondent.

Provinces and municipalities are more supportive than the national government. Using the profits from selling their shares in the regional and local utilities, they installed subsidies for home-owners and support GIs with starting subsidies or loans, practical advice, and e.g., temporary office space. Moreover, municipalities and provinces have encouraged networks between GIs and wider sustainability activities, such as Power2Nijmegen (Nijmegen municipality) and the Community of Practice of energy cooperatives (Gelderland province).

3.7.2. Motivations of GIs

Whereas the traditional wind cooperatives had a strong environmental motivation, and the Frisian turbines were built to generate local revenue, the motivations for the third and fourth wave GIs are much more diverse and include various economic, environmental and societal arguments. The environmental motivation is still dominant for most GIs, and encompasses reasons such as sustainability; being environmentally friendly, leaving a better (green) world for next generations, reducing CO2 emissions and reversing climate change. Opposition to nuclear power plays a much smaller role than it did some decades ago. Economic motivations for GIs are on the rise. Initiators are often volunteers who are “in it for the environment”, but many passive members see GIs as a profitable investment. Interview respondents indicate that reducing the energy bill, offering a cheap or independent alternative to fossil fuels, and creating revenue for investors are strong motivations to attract members. Lastly, societal reasons are less prominent. Developing the region or community, improving the local landscape, and achieving independence as a community are often cited as secondary reasons. For “branding”, the local identity is very important, as Lochem Energy explains: “If people can buy Lochem energy, it makes them feel more connected than if they buy from a national company”. Most GIs brand themselves distinctively as local by using the name of their village, city or region. A handful of small projects are aimed more directly at revitalizing communities: these are mainly rural areas with problems of demographic decline and relative poverty. The combination of elements in the motivation is increasingly common, which is reflected in the common GIs catchphrase “samen lokaal duurzaam” (together, local, sustainable), emphasizing both sustainability and a community orientation.

New GIs were also hugely inspired by the success of the third wave pioneers and their visibility in e.g., the HIER Opgewekt national events, the popular documentary “Power to the People” [48], and the media attention for Urgenda. “When I saw that on TV, I thought: that’s what I want too” explains a local initiator. Increasing networking and subsequent availability of practical information for starting cooperatives further enabled initiators. The economic crisis led to a relatively high unemployment rate among higher educated people, many of whom founded GIs, often with the active support of the municipalities, which co-founded many GIs or gave start-up subsidies. In short, the motivations form a broad mix of environmental, social and economic discourses that fit well with local governments, but form a poor fit with the national government, which focuses on large projects and economic gains.

3.7.3. Activities

The third and fourth wave GIs display a wide range of (new) activities. The boom of the fourth wave came prior to the zipcode rose and SDE+ subsidies, but was inspired by the introduction of a new activity by the third wave pioneers: collective purchase of solar panels. Because of technological developments in solar PV and economies of scale, the prices of (Chinese) solar panels had dropped steeply. With subsidies still in place, the net metering law of 2008, and with a number of provincial and municipal subsidies for home improvements regarding RE, the pay-back time for solar PV dropped from over 20 years to below 10 years, with even better deals if one bought solar panels through a collective. Led on by a number of high profile examples such as Urgenda, this activity was repeated by many new GIs. Especially with the government’s cutbacks since 2010, GIs became a popular alternative. The social acceptance of solar projects was high and they became a common sight in the built environment. Solar panels were also seen as a way to cut back on future expenses on energy, which was very appealing in these times of economic crisis.

The spectacular growth of GIs is nuanced somewhat if one looks at their activities. Since many GIs are very young, they are still in an early phase of development, and as it can take many years to realize a project for RE production or provision, this is not reached (yet) by most of the new initiatives. Even with popular collective purchase actions, almost a third of GIs does not display any activities beyond organizing information meetings for members and organizing the GI internally, with regards to communication, membership recruitment and developing business cases or projects (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Occurrence of activities of GIs.

Table 1 shows that facilitation, the “low hanging fruit” is harvested by the majority of the initiatives. This ranges from organizing an evening on led-lighting to collectively purchasing and installing solar panels on private roofs. Only a minority moves beyond that to more laborious activities. Supply of green electricity is popular, mostly because some licensed suppliers actively seek collaboration with local GIs. For example, supplier NLD pays a fee to the cooperatives for each of their members who buys their electricity and invites cooperatives to become affiliated with them. These constructions are also seen with, e.g., Greenchoice, Eneco, Qwint and Huismerk Energie, sometimes with branding of the electricity as a product of the GI, sometimes as an affiliation.

The production of RE by GIs consists of a mix of technologies often supported by the SDE+ subsidy for wind parks and solar roofs. In 2015, 52 solar projects were built and 67 in 2016 (including the 38 zipcode roses). These solar projects range from very small (e.g., on a local school) to as large as 27,000 solar panels in Garyp. In 2016, 19 cooperatives have been founded specifically for a zipcode rose project, which means that despite the dominant signature of the fourth wave GIs as broad in activities, some “specialists” also arise [1]. In this specialization we see a shift in technology from wind to solar PV, which was enabled by technological developments in solar panels but it also a consequence of the limited institutional fit for wind projects. Because of technological developments, wind turbines have increased in cost and as one wind pioneer explains: “without subsidies, it would be impossible to build cooperative turbines at present”.

3.7.4. Networks

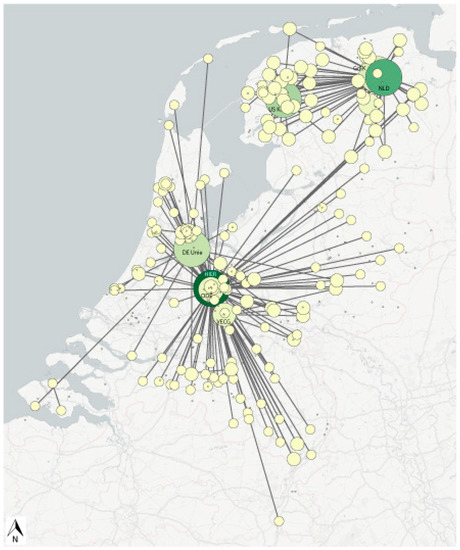

In order to overcome regulatory, economic and political constraints, GIs increasingly connect among each other to exchange knowledge, marshal public support and forge political alliances. These connections take many shapes and sizes: there are national networks; networks regarding a specific technology; regional networks; and networks that include GIs and their partners such as municipalities, energy companies or local businesses. There are three large national umbrellas for GIs: ODE Decentraal, REScoop and HIER Opgewekt.

- ODE Decentraal, founded in 1979, grew to become an important independent network and lobbyist. It merged in 2015 with E-decentraal, an umbrella for wind cooperatives, and is increasingly influential in lobby (e.g., it successfully lobbied for better tax rules in the zipcode rose). It also facilitates knowledge exchange among members and practical support for GIs.

- HIER Opgewekt was founded in 2012 and is financed by the Dutch grid operators in order to strengthen local initiatives, connect people working on RE and support the realization of their ambitions. HIER Opgewekt functions as a platform to connect GIs and hosts a large annual national event for networking and knowledge exchange.

- REScoop NL, the Dutch umbrella for 37 wind and solar cooperatives, was founded in 2013 following an EU project to form a network of energy cooperatives. REScoop NL primarily supports local production ambitions, mostly wind parks, through practical support in the project development phase, and sometimes through sharing in the financial risk. It works closely together with ODE Decentraal.

Regional alliances have also emerged in the past few years, such as US Kooperaasje in Friesland, GrEK in Groningen, Drentse KEI in Drenthe, NLD as a collaboration between the former three, VECG in Gelderland, VECB in Noord-Brabant, but also more local organizations such as Power2Nijmegen and Energy Made in Arnhem, both citywide umbrella platforms, and AGEM for the region Achterhoek. Figure 5 maps the national and regional networks of GIs and demonstrates the increasing connectivities between GIs. These networks focus on knowledge exchange and GIs help each other with e.g., business cases and subsidy applications. Here, an increase in relational fit also improves the distributive fit for GIs, and the visibility of the movement strengthens the legitimacy of their actions. Furthermore, there are partnerships for electricity resale with energy companies such as Greenchoice and more recently DE Unie (which serves as an energy company for 24 local RE production GIs) and Huismerk Energie (three GIs). In addition, nearly all GIs cooperate with local organizations, such as municipalities, provinces, schools, provincial environmental organizations and local sports or cultural organizations.

Figure 5.

Local and national networks between GIs in The Netherlands. Connections represent primary and secondary affiliations according to GI’s website. National and regional umbrella organizations and abbreviations: HIER Opgewekt (HIER); ODE Decentraal (ODE); Duurzame Energie Unie (DE Unie); Vereniging Energie Coöperaties Gelderland (VCEG); Groninger Energie Koepel (GrEK); Ús Koöperaasje (US K); Noordelijk Lokaal Duurzaam (NLD).

Next to increasing networking, another trend becomes visible: increasing professionalization of a few GIs and frustration and waning enthusiasm among the others. The “low hanging fruits” of collective purchase activities have been harvested, which means that the target group of home owners that privately invest in their properties has been catered for, leaving GIs disillusioned that “creating a local energy transition” is not as easy as they initially hoped and the institutional fit for larger activities is very limited. There is a current stagnation in the growth of the number of initiatives. This can be explained by a saturation of the field—there are now over 360 initiatives in 390 municipalities—and by demotivation and waning enthusiasm among the initiatives that have difficulties in starting up projects. There seems to be a divide between strong projects that expand and thrive, and weaker projects that cease to exist. Umbrella organization ODE Decentraal expects that with the announced termination of net metering after 2020, new projects will become even less.

Professionalization and waning enthusiasm are in this case two sides of the same coin: the bar for projects is raised, and GIs that do make it through the first process steps of a new project will be strong, well-connected and visible local players that can play a significant role in the Dutch energy transition. The current generation of GIs has to professionalize, which means hiring personnel rather than depending on volunteers, and collaborating with other GIs, such as Spinderwind in Tilburg, in which ten cooperatives work together to build a four turbine wind park, and BRES Breda, where four GIs work together in a joint development cooperative. We expect that the number of GIs will stabilize or even drop as the market for the more easily attainable projects is saturated. Instead, some GIs will cease to exist where others will continue to professionalize and team up with each other in order to build larger scale projects, with a focus on wind and solar parks. The local, regional and national networks will become even more important as GIs activities scale up. For example, REScoop NL is setting up an investment fund that can share the financial risk of a wind park in early stages of the development, and ODE Decentraal is offering workshops “how to build your own wind park”. These types of support can prove very helpful for aspiring GIs.

Lastly, the increased networking and visibility of GIs leads to a stronger position in the political lobby of umbrella organization ODE Decentraal. Whereas the market parties still have a much stronger voice in the political debate, ODE Decentraal is increasingly present at meetings and consultations, which could lead to institutional barriers (such as limited net metering and unfavorable taxes) to at least be recognized and discussed as such in The Hague.

3.8. Overview of Waves of Development of GIs

To summarize, the development of the GIs movement in The Netherlands has had a number of distinct waves, and the institutional circumstances in which the GIs developed clearly made its mark on the GIs (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Overview of waves of GI development.

From Table 2, it becomes clear that institutional conditions indeed have a strong effect on the development of GIs for renewable energy. The most notable example is the period around the liberalization of the energy market, in which the conditions were so unpredictable that the development of GIs came to a complete standstill. Similarly, we see that the second wave of Frisian turbines did not expand nationally as the success of the project depended for a significant degree on the subsidies and support provided by the province. Conversely, we see that, in the fourth wave of projects, many new GIs jump to the opportunity and start a collective purchase action or a solar project using SDE+ or zipcode rose subsidies. This illustrates that both the number of GIs in the field and their activities can be constrained or enabled by the institutional conditions in which they emerge.

4. Discussion

The process of development and institutionalization of GIs in The Netherlands can be used to nuance the academic findings on the innovative potential of GIs for renewable energy. The literature on grassroots innovations and of bottom-up transition management generally attributes a large potential to GIs, but our research suggests that this potential is highly context dependent. We adhere to the conclusion that GIs can develop the capacity to “nurture an innovation culture based on democracy, openness, diversity, practical experimentation, social learning and negotiation” [49]. However, in an institutional structure that does not share this discourse, it is very difficult for GIs to establish meaningful coalitions and position their local and small-scale approach vis-à-vis large companies, offshore windparks, and the lobby and interests of energy giants.

The activities of GIs have been described as instances of governance, in which policy making becomes more multi-level and multi-actor. Indeed, many of the countries in which GIs are successful provide (or have provided) such an environment, such as the UK, Denmark and Germany [6,11] that have active national policies that stimulate GIs. The importance of these instances of institutional fit becomes apparent if one looks at countries where GIs are less developed, such as southern and eastern Europe. The difference in numbers of GIs between countries has been explained by socio-economic characteristics of the institutional environment [12] and the poor connection between the macro institutional framework and the local, micro-level actor network. This could be characterized as institutional fit and the findings of this study confirm the importance of this connection, adding that not only the occurrence of GIs but also (and more so) their relative success depends on their local and national embedment. Discursive fit can also be emphasized in this context, as the shared belief in the legitimacy of GIs as actors determines their inclusion in policy making processes. Designing policies to aid GIs implicitly acknowledges the position of community members as actors rather than as consumers of energy, which is something that is lacking in the Dutch institutional environment at the national level. This makes institutionalization very difficult and hinders the potential for GIs to act.

In a “game” of large incumbents and economic considerations, the institutional structure can form a socio-technical constraint that is insuperable for GIs even though when forming a promising niche. This constraint has two consequences: it slows down the growth of the movement of GIs, which is only slowly and with difficulty finding ways to have its political voice heard, and decreases the degree of innovation of GIs. In a culture in which they are more nurtured and embedded in policy, GIs find a “protected space” in which they can experiment more freely [50]. Conversely, in a system in which subsidies are granted for projects with higher outputs and where rules are subject to change, such as the Dutch system, we see risk averse behavior and activities that can be considered “low hanging fruits”. Grassroots initiatives are therefore not by definition innovative, something that can also be seen in the widespread copying of successful practices, from the Frisian wind turbines in the 1990s to the recent collective purchase activities. Though there have been innovations in the movement, most of the current GIs form a clear path of development in their activities, and their main innovation is a shift to the local level and to a multi-actor energy system, which is hindered by the strong influence of the national level and large incumbents. The modest position of GIs in The Netherlands has created little opportunities to change their environment in order to create a better fit. More opportunities for GIs seem to be found at the decentral level, where the fit is larger. The Dutch case studies illustrate the importance of local embeddedness for success of GIs [18,20,21].

Concerning the conceptual contributions of this paper, we contend that specifying institutional fit into relational fit, distributive fit, regulatory fit and discursive fit, creates a detailed picture of the embeddedness of grassroots initiatives. Following recent calls to place institutional analysis at the core of low-carbon energy transitions [51] (p. 223), we were able to enhance institutional analysis with these four types of institutional fit. The analysis shows differences in fit, both in time and in level of governance. The relatively strong fit at the regional and local level is much in line with the findings of Warbroek and Hoppe [21] for the provinces of Overijssel and Friesland. Indeed, our study shows a relational fit at the provincial and local level, rather than the national level.

The regulatory and distributive fit of GIs with the energy policy system can be characterized as GIs following policy changes, instead of GIs provoking regime changes. This is in line with the later transition literature, which sees regimes as initiators of transformations [52], instead of GIs as loci of innovations [53].

5. Conclusions

This research departed from the puzzling seeming asymmetry between the growth of GIs in a system that provided limited institutional fit, asking two central questions: how did the movement of GIs in The Netherlands develop, and how and why has this movement become (limitedly) institutionalized in the Dutch (renewable) energy policy domain? In answer to these questions, we indeed see the asymmetry in practice: GIs developed largely outside of the political realm, finding institutional fit at the local level but barely becoming institutionalized at the national level. The development of the movement of GIs can be characterized in four waves, the first two of which focused on wind power and the latter two with a broad sustainability agenda and solar PV as main technology. None of these waves were institutionalized at the national level in the sense that they were acknowledged as potentially influential and valuable partners with influence in the policy making process. This lack of institutionalization can be attributed to different reasons. The first two waves did not seek political influence, as they never had the intention to grow beyond their niche activities. Moreover, the second wave valued local institutionalization (i.e., access to and a good relationship with the province) rather than national influence. The third and fourth wave did seek to become part of mainstream energy policy, but faced a lack of institutional fit. Most importantly, the economic and large-scale discourse of the national government collided with the environmental and local orientation of GIs, creating no ground for a meaningful actor coalition. As a result, GIs had little access to the distribution of (financial) resources and policies were not tailored to their types of activities, and thus faced poor distributive and regulatory fit. They aligned better with the provincial and municipal governments, which valued the local emphasis of GIs, but energy policy remains quite centralized and the lack of fit at the national level has hindered both the development of GIs as a movement and their innovative potential. Overall, energy policy in The Netherlands remains a game of the national government, large industrial and market players, and rules and technologies aiming for large RE projects with the highest profit margins. In this game, there is little place for GIs, which create activities that do not require a large fit in this national game, but focus on local coalitions, or seek to professionalize in order to become recognized and secure a position in the system.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the four anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments, which helped us to improve the manuscript. The article is a result of the research activities within the project ‘MobGIs—Mobilizing grassroots capacities for sustainable energy transitions: path improvement or path change?’ which has received funding from The Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) as part of the JPI Climate Joint Call for Transnational Collaborative Research Projects, Societal Transformation in the Face of Climate Change.

Author Contributions

The article and research, including the interviews and construction of the database, are a collaborative effort of the three authors. M.O. took the lead in conducting the interviews and preparing the manuscript; and H.K. took the lead in constructing the database.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Schwencke, A.M. Lokale Energie Monitor; HIER Opgewekt: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2016. (In Dutch) [Google Scholar]

- Rijksdienst Voor Ondernemend Nederland. Rapportage Hernieuwbare Energie 2014; Rijksdienst Voor Ondernemend Nederland: Zwolle, The Nederlands, 2015. (In Dutch)

- Grol, C. RWE Krijgt 1,2 mrd Euro Subsidie voor Bijstook Biomassa; FD Media Groep: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. (In Dutch) [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, S.; Mazzucchelli, P. Evaluating the perspectives for hydrogen energy uptake in communities: Success criteria and their application. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 5359–5371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolsink, M. Wind power and the NIMBY-myth: Institutional capacity and the limited significance of public support. Renew. Energy 2000, 21, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, C.; Jungjohann, A. Energy Democracy: Germany’s Energiewende to Renewables; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Seyfang, G.; Smith, A. Grassroots innovations for sustainable development: Towards a new research and policy agenda. Environ. Politics 2007, 16, 584–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.; Upham, P. Grassroots social innovation and the mobilisation of values in collaborative comsumption: A conceptual model. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 134, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J.C.; Simmons, E.A.; Convery, I.; Weatherall, A. Public perceptions of opportunities for community-based renewable energy projects. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 4217–4226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, G.; Devine-Wright, P. Community renewable energy: What should it mean? Energy Policy 2008, 36, 497–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfang, G.; Park, J.; Smith, A. A thousand flowers blooming? An examination of community energy in the UK. Energy Policy 2013, 61, 977–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnani, N.; Osti, G. Does civil society matter? Challenges and strategies of grassroots initiatives in Italy’s energy transition. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 13, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfang, G.; Haxeltine, A. Growing grassroots innovations: exploring the role of community-based initiatives in governing sustainable energy transitions. Environ. Plan. C Politics Space 2012, 30, 381–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, P.; Arts, B. Institutional Dynamics in Environmental Governance; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek. Kerncijfers Energiebalans. 2016. Available online: https://www.cbs.nl (accessed on 24 January 2017).

- Ministerie van Economische Zaken. Energieagenda; Ministerie van Economische Zaken Den Haag: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2016. (In Dutch)

- Sociaal-Economische Raad (SER). Energieakkoord voor Duurzame Groei; Sociaal-Economische Raad: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2013. (In Dutch) [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Schoor, T.; Scholtens, B. Power to the people: Local community initiatives and the transition to sustainable energy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 43, 666–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hufen, H.; Koppejan, J. Local Renewable Energy Cooperatives: Revolution in Disguise? Energy Sustain. Soc. 2015, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, T.; Graf, A.; Warbroek, B.; Lammers, I.; Lepping, I. Local Governments Supporting Local Energy Initiatives: Lessons from the Best Practices of Saerbeck (Germany) and Lochem (The Netherlands). Sustainability 2015, 7, 1900–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warbroek, B.; Hoppe, T. Modes of governing and policy of local and regional governments supporting local low-carbon energy initiatives; exploring the cases of the Dutch regions of Overijssel and Fryslân. Sustainability 2017, 9, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer, J.; Zuidema, C. Towards an integrated energy landscape. Urban Des. Plan. 2015, 163, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, G.W.; Boon, W.P.; Peine, A. User-led innovation in civic energy communities. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2016, 19, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, F.; Smith, A. Restructuring energy systems for sustainability? Energy transition policy in the Netherlands. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 4093–4103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlett, M.; Ramesh, M.; Perl, A. Studying Public Policy: Policy Cycles and Policy Subsystems; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wiering, M.; Arts, B. Discursive shifts in Dutch river management: ‘Deep’ institutional change or adaptation strategy? In Living Rivers: Trends and Challenges in Science and Management; Springer: Houten, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 327–338. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E.; Janssen, M.A.; Anderies, J.M. Going beyond panaceas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 15176–15178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagedorn, K. Particular requirements for institutional analysis in nature-related sectors. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2008, 35, 357–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knill, C.; Lenschow, A. Implementing EU Environmental Policy: New Directions and Old Problems; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hajer, M.A. The Politics of Environmental Discourse: Ecological Modernization and the Policy Process; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Oteman, M.; Wiering, M.; Helderman, J.-K. The institutional space of community initiatives for renewable energy: A comparative case study of the Netherlands, Germany and Denmark. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2014, 4, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlijm, W. De Interactie Tussen de Overheid en de Elektriciteitssector in Nederland; Radboud Universiteit: Nijmegen, The Netherlands, 2002. (In Dutch) [Google Scholar]

- Correljé, A.; van der Linde, C.; Westerwoudt, T. Natural Gas in the Netherlands. From Cooperation to Competition; Oranje-Nassou Groep: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Verbong, G.; van Selm, A.; Knoppers, R.; Raven, R. (Eds.) Een Kwestie van Lange Adem. De geschiedenis van duurzame energie in Nederland; Aeneas: Boxtel, The Netherlands, 2001. (In Dutch) [Google Scholar]

- Ministerie van Economische Zaken. Energienota; Tweede Kamer der Staten Generaal: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 1974. (In Dutch)

- Tweede Kamer der Staten Generaal. Tweede Energienota; Session 1978–1979, 15100 nr. 18; Tweede Kamer der Staten Generaal: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 1979. (In Dutch)

- Agterbosch, S. Empowering Wind Power; On Social and Institutional Conditions Affecting the Performance of Entrepreneurs in the Wind Power Supply Market in the Netherlands; Utrecht University: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Veraart, M. Sturing van Publieke Dienstverlening; Uitgeverij Van Gorcum: Assen, The Netherlands, 2007. (In Dutch) [Google Scholar]

- Trommelen, J. Dorpsmolens zijn de toekomst van windenergie. In Volkskrant; Persgroep Nederland: Ede, The Netherlands, 2014. (In Dutch) [Google Scholar]

- Walthaus, A. Molenliefde—Reduzum Blijft Blij Met Eigen Dorpsturbine. In Leeuwarder Courant; NDC Media Groep: Leeuwarden, The Netherlands, 2014. (In Dutch) [Google Scholar]

- Bouma, J. De dorpsmolen heeft draagvlak. In Trouw; Persgroep Nederland: Ede, The Netherlands, 2014. (In Dutch) [Google Scholar]

- Ministerie van Economische Zaken. Nationaal Milieubeleidsplan; Tweede Kamer der Staten Generaal: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 1989. (In Dutch)

- Van Damme, E. Liberalizing the Dutch Electricity Market: 1998—2004. Energy J. 2005, 26, 155–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasbergen, P. Transities naar een duurzame ontwikkeling. Over de relevantie van het benutten van het marktmechanisme. Milieu 2002, 3, 110–122. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Loo, F.A. Op Reis Naar Het Zuiden: Energietransitie 2000–2010; MGMC Uitgeverij: Haarlem, The Netherlands, 2012. (In Dutch) [Google Scholar]

- Bremmer, D. (Ed.) Nijpels en SER zijn kritiek ‘peperdure’ windmolens zat. In Alg. Dagbl.; De Persgroep: Ede, The Netherlands, 2015. (In Dutch) [Google Scholar]

- Ministerie van Economische Zaken. Energierapport Transitie naar Duurzaam; Ministerie van Economische Zaken Den Haag: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2016. (In Dutch)

- Lubbe Bakker, S. (Director) Tegenlicht. Power to the People, [documentary]; VPRO: Hilversum, The Netherlands, 2012.

- Ornetzeder, M.; Rohracher, H. Of solar collectors, wind power, and car sharing: Comparing and understanding successful cases of grassroots innovations. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 856–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, R.; Rotmans, J. Managing the transition to sustainable mobility. In System Innovation and the Transition to Sustainability; Elzen, B., Geels, W., Green, K., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2005; pp. 137–167. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews-Speed, P. Applying Institutional Theory to the Low-Carbon Energy Transition. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 13, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbong, G.; Geels, F. Exploring Sustainability Transitions in the Electricity Sector with Socio-Technical Pathways. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2010, 77, 1214–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbloom, D.; Berton, H.; Meadowcroft, I. Framing the Sun: A discursive approach to understanding multi-dimensional interactions within socio-technical transitions through the case of solar electricity in Ontario, Canada. Res. Policy 2016, 45, 1275–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).