Abstract

In Europe, the energy transition by means of a governance shift through liberalization is followed by a transition and shift towards community energy initiatives, with a particular view of supporting the demand for greater energy sustainability. What institutional legal consequences, as constraints and opportunities for lawful behaviour, follow from a shift in legal governance towards facilitating resilient community energy services? This conceptual article looks for an answer to this question by combining governance theory with Ostrom’s IAD-framework and Institutional Legal Theory. A key aspect is understanding normative alignment (as institutional conduciveness and resilience) in relation to the possible shift from the current institutional environment of regulated energy market to that of a community energy network. The heuristic and analytical (design) relevance of the approach is illustrated with two policy examples contrasting the energy democratization and energy expansion frames, and discussed also in the perspective of energy governance experimentation with community energy initiatives in The Netherlands. Three scenarios of shifts in legal governance are identified. The key issue in legal governance design is the choice between these, particularly with respect to the integrity of institutional environments in terms of former frames to provide proper guidance to operational (experimental) activity.

1. Introduction

In this article, the Special Issue theme of ‘Innovation in the European Energy Sector and Regulatory Responses to It’ is taken up to discuss some underlying legal governance issues of energy sector innovation by community energy services. Such services are managed by or for a community entity and primarily in service of energy needs of that same community, and can contribute to the rise of smart energy systems that are deemed necessary to improve on renewable energy generation and energy saving and energy efficiency [1]. This article does not aim to suggest that these community energy services (henceforth CESs) offer the best approach to foster the energy transition (towards renewable energy services). It does however aim to improve our understanding of the normative nature of this approach, so as to contribute to its potential, while considering how it relates to other approaches, particularly those that focus on regulating the energy market. The legal governance understanding should support normative, but also (future) empirical analyses of existing CES-initiatives, and could also contribute to their design. Consequently, this article is mainly of a conceptual and theoretical nature addressing normative issues. With regard to its design aspect, the article focuses particularly on the element of normative resilience of CESs; the capability of CESs to endure over their intended lifespan while maintaining their normative integrity (i.e., providing stability to and putting community energy needs first): to absorb shocks (e.g., in response to unlawful practices) and to be sufficiently nimble to adapt when changes are needed (e.g., refocusing to facilitate third party involvement).

The leading question of this article is: what institutional legal consequences, as constraints and opportunities for lawful behaviour, are involved in a shift in legal governance towards facilitating resilient community energy services?

Shifts in legal governance to foster renewable energy services, particularly through CESs, will be the point of departure of this article in Section 2. It brings into focus the legal governance perspective of three basic modes of ‘Institutional Environments’ with relevance to energy governance: ‘Constitutional order’, featuring patterns of behaviour with respect to interactions with public government, ‘Competitive markets’, featuring patterns of behaviour concerning private enterprise interactions, and ‘Civil networks’, featuring patterns of behaviour regarding community and network interaction. (Henceforth written with first letter capitals to emphasize their specific type of characteristic: Co, Cm and Cn.) Next, in Section 3 the concepts of normative alignment between levels of governance, and normative resilience are introduced. Not with intent of innovative conceptualization, but primarily to add nuance to this article’s focus on institutional legal consequences of shifts in governance.

The conceptual framework of this article will be unfolded, step-by-step, in Section 4. It consists of three analytical layers. The first layer concerns the position of Institutional Environments, particularly their function from a perspective of multiple levels of governance(-analysis). The second layer builds on this understanding and adds a multi-actor governance perspective, whereby the relation between the said Institutional Environments and operational activities of CESs can be analysed. Collective action within institutionalized patterns of behaviour at one level can produce outcomes that, at least in part, shape similar patterns at another level. While the first and second layer are discussed as being about institutions as empirical phenomena, the third layer discusses the normative dimension of institutionalized patterns of behaviour; legal institutions purport empirically observable patterns of behaviour by virtue of legal prescription. This prescriptive side of institutions is key to the normative alignment; i.e., how actions at different governance levels should legally align. It is also key to the normative resilience of institutional arrangements, such as that of CESs, in the context of a given Institutional Environment, especially with regards to community involvement in operational practice. Table 1 pictures the framework.

Table 1.

Conceptual framework.

Against the backdrop of this framework, a brief reflection is provided, in Section 5, on two studies of renewable energy policy practice that were cause to concerns about normative resilience and thus to the analysis presented in the earlier paragraphs—these are illustrations as to the relevance of a normative, legal governance analysis. These studies were also the key incentive to look more closely, as described in Section 6, into the Dutch regime for legally arranged experimentation with CESs. These experiments aim to foster evidence-based choices on the future of energy governance, particularly with regard to the position of CESs—a case by which to demonstrate heuristic relevance of the above framework. Both the examples of Section 5 and the example of Section 6 are intended to illustrate the key elements of legal governance involved in enhancing an energy transition with normative resilience, thereby demonstrating, as will be discussed in Section 7, the heuristic, analytical and design relevance of the legal governance framework presented in Section 4. The article is concluded with key findings relevant to answering the above leading questions.

2. Background—The Energy Trilemma and Institutional Shifts in Mode of Governance

In Europe, the recent and partly still on-going energy transition through a governance shift from energy provision by public enterprises to provision by private corporations, now comes accompanied by initiatives towards another transition: a governance shift towards energy provision by private collectives (e.g., communities). A major driver behind this potential new shift is that the energy market does not seem to live up to the desired sustainability objectives.

From the viewpoint of the energy trilemma—reliable, affordable and sustainable energy services—there are various reasons for this new shift [2,3,4]. Less a concern over affordable access, as the market is generally believed to deliver on this, but certainly a concern over reliability, especially in view of geopolitical concerns, and also over sustainability, given the need for an expedient response to the threats of climate change.

Meanwhile, the transition through a shift from government to market through privatization and liberalization is incomplete, placing energy production and delivery in a hybrid zone of a ‘regulated market’. This is largely due to the public-value aspects of the energy trilemma: concerns over human rights and distributive justice (e.g., access to energy) add a particular dimension to the requirement of energy affordability. One that has given rise to regulatory interventions in the price/demand and supply mechanism, such as the vertical unbundling requirement, regulation of tariffs, duty of supply, and constraints on the power to disconnected consumers from energy delivery.

Another public value concern is that the market should not only deliver static efficiency, leading to lower prices, but also dynamic efficiency, which can enhance reliability and sustainability of energy services. Two public governance types of responses, typical of the current regulated energy market, address this latter concern: (1) retaining public ownership over energy grids; (2) regulating production and supply to secure reliability and sustainability by technical standards [5]. Meanwhile a third response has emerged, suggesting another mode of governance, as ‘Institutional Environment’ to energy actor interactions: (3) ‘Civil networks’. Such networks are about empowering civil society cooperation, and facilitate private community collectives, sharing and prosumerism.

This article is about understanding the normative nature of this third response from a legal governance perspective—not to claim that it is the best response to the challenge of, particularly, sustainability, but to better understand its normative functioning and to support its best possible use.

3. Legal Space—Normative Alignment and Resilience

In the context of a possible new shift in governance, fostering CESs, our leading question focuses on legal consequences of the normative dimension of a fitting new Institutional Environment to such CESs, to the existing public energy service practice.

3.1. Normative Alignment

The relevant energy service practice is that of actor forms, actor relations and actor behaviour concerning energy services. The most important actor types are community energy services (CESs—managed by or for a community entity and primarily in service of energy needs of that same community), energy regulators (i.e., government authorities in standard setting, monitoring and enforcement), distribution system operators (DSOs—responsible for operating, ensuring the maintenance of and, if necessary, developing the distribution system for delivery of electricity to the end-user), transmission system operators (TSOs—responsible for developing, maintaining and operating the high voltage energy grid, transmission of electricity to the distribution system, while balancing supply and demand), energy suppliers (i.e., energy companies that provide consumers with energy), energy brokers (i.e., companies that offer services as ‘middleman’ between other actors), and energy aggregators (i.e., energy brokers which pool and represent consumers and prosumers).

The normative dimension of an Institutional Environment is the ‘legal space’ applicable to such practice. Legal space encompasses the existing legal liberties to act lawfully, determined by rules of conduct, such as permission to produce and supply energy, and available legal abilities to validly change legal liberties, determined by rules of power, such as to prohibit prosumerism [6,7]. To speak of the normative dimension of an Institutional Environment is to claim that, aside from its characteristic empirically observable pattern of behaviour in practice, it also is prescriptive of a characteristic normative pattern of behaviour, as the applicable legal space, with basic rules of power and of conduct [8]. As we will discuss in Section 4.3, in some cases such a legal space of a type of Institutional Environment manifests as a legal institution, that may be instantiated repeatedly [9,10].

Normative alignment is about the lawfulness of practices at different levels of governance, with a focus on how lawfulness is determined across such levels. The Institutional Environment for energy governance that is, for example, shaped at the supranational EU-level, should align across EU member states to CESs practices of local communities within these states. Normative alignment is relevant firstly to the functionality and functional conduciveness of a given Institutional Environment. Does the environment provide the proper legal instruments and incentives to indeed establish the kind of desired new practices it prescribes, such as that of setting-up and operating CESs? Does the legal space provide functional legal liberties, such as licences to install energy generating facilities? Does it come with functional legal abilities, such as the legal powers to grant licences and agree on contracts to operate a community energy grid? [7,11] If an Institutional Environment is about promoting CESs, then it should provide a functional legal space that offers the legal instruments and incentives to make this happen in an effective, efficient, legitimate and just way.

3.2. Normative Resilience

Next to conduciveness, normative alignment is about resilience. Resilience, taken from a legal standpoint, is about the ability of an Institutional Environment to absorb, by legal mechanisms of resistance and recovery, unlawful practices, and also to adapt its legal space rules to accommodate and retain, or to improve its legal functionality vis-a-vis a new desired practice. (Note that ‘resilience’ has many definitions. We follow Folke [12] given how he explicitly includes the element of renewal next to the capacity to absorb.)

The legal capacity to absorb shocks amounts to resisting non-aligned (i.e., legally invalid) or misaligned (i.e., unlawful) actor forms, relations and behaviour—ex ante or upon occurrence. Absorption is also about, ex post to a breach, being able to recover. When, for example, CESs are not allowed to operate as energy companies, but are seen to do so anyway, (how) is the prohibition enforced and (how) is the possible harm to others compensated? Absorption is important to normative alignment, as this builds on the assumption that practice should legally agree with the institutionalized legal space and not vice versa.

The capacity to adapt is relevant to normative alignment because it enables Institutional Environments to change their legal space to (re)connect to desired (new) practices [13,14]. This may be to improve on functional conduciveness, by better legal instruments and incentives towards the desired practice, such as by introducing a dedicated type of legal personality for CESs. Adaptation may also be aimed at improving the absorptive capacity to address misalignment, for example by introducing new sanctions or remedies to unlawful behaviour. Finally, it may be to improve adaptive capacity itself, as the institutional nimbleness, for instance by introducing greater regulatory discretion of energy regulators, or freedom to experiment. Should an unlawful but desired innovative practice evolve, such as of informal CESs, the relevant regulator could then decide to ignore its ability of absorbing the shock by enforcing compliance with the existing legal space, and instead nimbly opt for embracing such practice by (experimental) adaptation of that legal space.

Normative resilience of an Institutional Environment is about its capacity to retain its normative integrity over its intended lifespan. This involves two aspects. Firstly, a continued certainty over legal settings of legal abilities and legal liberties, to allow a stable legal governance practice to develop over the institutional lifespan. When establishing a CES it is important that there can be reliance on the relevant rules, instruments and incentives, so that the CES can become successful when remaining in alignment. The second aspect is that the normative identity, of purpose and nature of the Institutional Environment is retained in the course of its lifespan. In case of an Institutional Environment of civil energy networks, within which CESs can legally operate, this would be at stake when the guiding purpose of promoting ‘democratization’ of renewable energy services, with a key say by and benefit to CES’ communities—internalizing procedural and distributive justice [15,16]—would, through decisions of regulators and courts, be mixed with or replaced by mere ‘expansion’ of renewable energy services. Such change could seriously infringe on the legal position of CESs, on both justice aspects, by limiting participation in and benefits from (commercially driven) renewable energy services [17].

While ‘slippery slope’ normative reframing should be resisted, the desire for normative integrity should not preclude the possibility of change through adaptation. Such change could follow from ‘intrinsic powers’, embedded in the legal space of an Institutional Environment, granting relevant actors the legal capacity to ‘self-regulate’ their relations (i.e., to decide on the rules of game-play). Alternatively, changes could follow from ‘extrinsic) powers’, of higher authorities, such as a constitutional or prime legislator, to establish and to (re)shape the legal space of Institutional Environments (i.e., to decide on the rules of the game). This difference between intrinsic and extrinsic powers to make legal changes resists a situation whereby actors within an Institutional Environment can change the settings of that environment—such as by creating new powers, to change the ‘rules of the game’. (Note that next to ‘rules of the game’ there are ‘rules of game-play’, which follow choices about strategies of playing the game within given ‘rules of the game’—assuming that the latter allow strategic discretion. For example: within the rules of the football game there are different strategies, such as an offensive or a defensive strategy, which require that players adhere to different sets of rules to play the game.) The design of the legal space of an Institutional Environment (i.e., the rules of the game) will determine how much discretion exists for actors within to make changes. The environment of a regulated energy market may perhaps come with considerable powers of an energy regulator, to reshape the rules of conduct between CESs and DSOs, but conversely it may be that such regulatory powers are constrained to safeguard greater legal certainty and integrity, particularly when the higher authority holds a strict view on, for example, the purpose of energy democratization through CESs, versus mere expansion of renewable energy services.

In principle a shift in governance, as a shift from one to another type of Institutional Environment, lies in the hands of the named higher authorities responsible for establishing and (re)shaping such environments. In practice, however, when intrinsic powers do leave more discretion for actors to (re)shape their own legal space, there may be considerable changes in legal positions, without ‘outside’ intervention—unless such changes trigger higher authority (i.e., extrinsic) intervention. Generally, when we speak of shifts in governance, we refer to disruptive changes in the legal space available to certain types of interactions, such as those concerning energy services. New or different types of actor forms and actor relations are introduced or excluded, together with new or different opportunities and constrains to de facto actor behaviour; to make for a different mode of allocation of goods, services and (other) resources. Changes initiated from within existing Institutional Environments are likely to be of a more evolutionary nature, and even when they do come with new and different legal arrangements, these are less likely to be regarded as legally disruptive because they were potentially included in the discretion granted to their makers. (Note that the term disruption is used in analogy to its use in business studies [18].) Clearly privatization and liberalization of energy provision, as a move from Constitutional order in the direction of a Competitive market, is an example of a legally disruptive change. Even the resulting shift to the hybrid Institutional Environment of the Regulated energy market, combining elements of Constitutional order and of Competitive markets has this disruptive nature. This follows, particularly, from adding ‘alien’ to Competitive markets’ incentives, such as constraints on the freedom of contracting, as regards pricing and disconnecting defaulters, and also through the requirement of (vertically) unbundling energy generation and distribution, and the prohibition of prosumerism. These are elements beyond merely adding some ‘hybrid vigour’ to an existing Institutional Environment, as a matter of intrinsic adaptive resilience (i.e., from within), with the aim of changing the balance in the energy trilemma. Clearly though, normative resilience is an aspect of normative alignment between levels of governance that should be analysed or designed-in with a view on power distribution between different institutional levels—which is a topic in the next paragraph.

To summarize and conclude, normative alignment is relevant as a matter of conduciveness and resilience.

- -

- Conduciveness is about an Institutional Environment providing instrumental and incentivizing conditions, through legal liberties and abilities that functionally facilitate and support a desired practice—in normative alignment.

- -

- Resilience is about mechanisms for absorption of shocks of misalignment (through resistance, by legal duties or immunities, and through enforcement (sanctions) and recovery (measures of restoration) and mechanisms of adaptation that bring the nimbleness to enhance normative alignment in the light of a desired practice (through improved conduciveness, absorption and adaptation).

- -

- Resilience is relevant as normative integrity of an Institutional environment will enhance the necessary legal certainty and normative guidance to see a desired, normatively aligning practice develop and flourish.

- -

- Shifts in governance may occur that come with disruptive institutional change, as they reach beyond resilience following (intrinsic) acts from actors operating within the given legal space of an Institutional Environment, and involve (extrinsic) acts from actors that have the authority to introduce, change and terminate Institutional Environments—particularly with regard to the powers that are allocated to actors within—ultimately to require practice to align with this new or changed regime. (Note that there is a significant difference between institutional change as a mere social fact, ascertainable by empirical analysis, and such change as an institutional legal fact, ascertainable by normative analysis—more on this later.)

Normative alignment is about consistency and coherence across governance levels, of lawful and valid connections, while normative resilience is about the strength of these connections (through instruments of enforcement provided by one of the next levels), and built-in capacity to change a rule or an institution (through nimbleness from within and/or an outside up-level). Normative integrity is, in all of the before, and again also across levels, the element of normative identity/purpose, that gives (policy) meaning to the whole framework of legal rules and institutions—such as in the quest for energy democratization. This article places both elements (alignment and resilience) in a legal governance perspective relevant to the facilitation of CESs.

Table 2 presents the main elements of normative alignment as set out in the above. A distinction is made between ‘static alignment’ (in the top half of the table) for the analytical question if, in a given setting, there is alignment, and ‘resilient alignment’ (in the bottom half of the table), focusing on the dynamic aspects of the normative alignment challenge.

Table 2.

Elements of Resilient Normative Alignment.

4. Theory—Combining Energy Governance with Legal Institutions

We will now take the three steps mentioned in Section 1 (and pictured in Table 1), whereby we place normative alignment in a broader governance perspective, particularly of lawfulness of practices at different levels of governance, based upon how lawfulness is determined across such levels. As explained in Section 1, we have three layers that together form our conceptual framework. We start, in Section 4.1, with a model for multi-level analysis of governance and key types of Institutional Environments, so we will have a first idea about governance levels and about the nature and types of Institutional Environments. Next, in Section 4.2, we look at the multi-actor character of governance, particularly through the lens of collective action. This is intended to clarify actions at different governance levels influence each other, which is crucial to institutional alignment. The particular focus of normative alignment will be introduced, in Section 4.3, which discusses the legal governance perspective through the lens of Institutional legal Theory.

4.1. Modes and Levels of Governance

Shifts involved in major energy transitions relate to different modes of governance. Modes of regular and recurring patterns of coordination of interactions between different actors in the energy field. These patterns have our interest as a matter of public governance, being relevant to interactions with (intended) impacts on societal interests, such as on public energy services. Patterns or modes of public governance involve a combination of relevant levels or scales (e.g., international, national, local), structures (e.g., informal/formal relations/organizations), perceptions (e.g., of perceived societal and actor needs and problems), resources (e.g., factual or legal, such as powers and rights) [11], and mechanisms (e.g., procedures of decision-making). On such basis actors engage in interactions. Such interactions concern either transactions regarding goods, services, information, rights, votes, and (other) resources [19,20,21], or regulation, as a ‘focused and sustained attempt to alter the behaviour of others’ [22]. (Note that “The defining hallmark of interaction is influence; each partner’s behaviour influences the other partner’s subsequent behaviour” [23] (p. 845). J.R. Commons [19] defines a transaction as an exchange of goods or services between technologically separable entities. Oliver E. Williamson [20] spoke of a transaction as an “exchange of goods or services across a technologically separable interface.”) (Note also the possibility of overlaps between transactions and regulation, such as through transfer of information.) (Note finally, that there may be other subcategories of interactions, such as those supporting transactions and regulation, such as negotiating, nudging).

In Williamson’s [24] model of social analysis, governance is connected to four institutional levels. Each level comes with institutions that have their own average frequency of change, and each higher level imposes constraints on (patterns of) interactions at the immediately below level, with reverse feedbacks for institutional change. Our interest goes out mostly to the relation between the two mid-levels: levels 2 and 3. Level 2 is about establishing ‘Institutional Environments’, determining the ‘rules of the game’, such as rules of property law, or rules determining the make-up of government. These rules of the game impact upon level 3, which is about arranging ‘governance structures’, such as relational contracting and establishing a firm, ready for use at level 4. Levels 2 and 3 are placed in-between long-term ‘Embeddedness’, at level 1, and day-to-day ‘Resource allocation’, at level 4.

Table 3 presents Williamson’s model, but amended for some level-labels (in columns 1 and 2) that we find easier to use. (Note that while Williamson uses ‘governance’ to describe phenomena at level 3 (being about “an effort to craft order, thereby to mitigate conflict and realize mutual gains.” [24] (p. 599), we prefer to use ‘governance’ to capture both levels 2 and 3, which we feel is still in keeping with the afore description.) (Note also how the levels presented by Williamson are also traceable in relevant recent work of Scholten and Künneke [25].)

Table 3.

Institutional Levels of Governance. (Taken, with some amendments, from: O.E. Williamson (2000) Figure 1: Economics of Institutions).

To regard Institutional Environments as “characterized by the elaboration of rules and requirements to which individual organizations must conform if they are to receive legitimacy and support’’ [26] (p. 132), is key to alignment between situations and events at level 2 and level 3. Institutional Environments are as the ‘habitats’ in which ‘organisms’ interact—analogous to animals and plants interacting in water, on land and in the air. The basic rules that make for an Institutional Environment preordain a characteristic pattern of relations and interest pursuits, and so enable and constrain certain types of actors and of interactions between them. They settle the rules of the game that underpin the making and resilient functioning of level 3. (Governance Structures) to establishing the rules of game-play that facilitate playing the game at level 4. The existence of such level 2 patterns may only be a matter of empirical regularity, following from ‘strategies’ upon mutually understood actor preferences, or from ‘norms’ about shared actor perceptions on proper behaviour [27] (pp. 581–583). Alternatively, level 2 patterns are of a prescriptive nature, as a pattern following the rules of a particular legal space, perhaps as a type of legal institution—more on which when we discuss the third layer of our framework, in Section 4.3.

It may seem that in the above model institutions at higher levels are more resilient, when considering their average length of lifespan. At lower levels resilience would then be assumed to be lower. It is, however, important to keep in mind that resilience is relative to intended lifespan, and to discretion as regards normative identity—a contract with an intended lifespan of minutes or days between agreement and execution, should have a fitting absorptive and adaptive capacity, tailored to circumstances, with a proper balance between intrinsic and extrinsic powers to adapt. (Note that the rules concerning a contract for a cup of coffee should allow for adaptation if both parties agree that it be changed to tea when the coffee machine isn’t working—generally the institutional rules allow much contractual discretion, particular to mutually agreed changes.) Clearly, for Institutional Environments to make sense, a considerable lifespan is generally foreseen; 10–102 years, according to Williamson. Mechanisms of absorptive and adaptive capacity should again fit purpose in normative integrity, across the intended lifespan and regarding normative time, to withstand and, if necessary, adjust to undesired or desired practices. In any case, normative resilience will depend on a proper fit between higher and lower level institutions, to validate lower level institutions by their fit with higher level institutions (e.g., energy generation permits upon state power), and to realize higher level institutions’ purpose by a fitting lower level practice (e.g., a Regulated market functioning through unbundled energy companies).

4.1.1. Three Institutional Environments

As empirically observable patterns of a game-type, Institutional Environments define ‘rules of the game’ for establishing fitting Governance Structures at level 3. We conceptualise these level 2 patterns as being founded on a specific ‘institutional nexus’, defined by a matching pair of a key type of interest and a key type of relationship between actors. (See Arentsen and Künneke, for a similar but more economical approach [5].)

As regards key interests, as dominant incentive and justification of an interaction, we distinguish three types. ‘Private interests’ are about interests of single private individuals or organisations (e.g., private freedoms or gains). ‘Social interests’ are about interests shared by/between members of a group of persons, possibly a community or society as a whole (e.g., education, safety, clean environment). (Note that ‘sharing’ suggests that social interests are a subtype of private interests, implicating that there will be some individual interests which are strictly personal and not shared by others, let alone by society as a whole. It’s debatable, but will not be debated here, if there are social interests that are not also private/individual interests.) Thirdly, ‘public interests’ are social interests identified by government as a government concern [28]. Despite overlaps, each of these three types of interests has its own characteristic and operates as key driver behind relational behaviour of actors, being either in service of private, social, or public interests.

As regards key-types of relationships, as dominant mechanism of interaction, we distinguish three types. ‘Hierarchical’ relations connect a superior to (one or more) subordinates, and express a command mechanism of interaction (e.g., a government versus citizens; an owner versus property users and employer vis-à-vis employees). ‘Exchange’ relations are about actors engaging in a mechanism of reciprocal interaction (e.g., buying and selling between individuals; B2C or B2B). ‘Network’ relations are about actors engaging in a cooperative mechanism of collaborative interaction (e.g., sharing, assisting or supporting). (Note that, alternatively, Reis et al. [23] (p. 846) refer to Clark and Mills’ [29] distinction between communal (reciprocal responsiveness) and exchange (benefit repayment) relationships, and also to Fiske’s [30] four types of relationship: communal sharing, authority ranking, equality matching, and market pricing).

Theoretically, nine institutional nexus of interest-relationship combinations exist as models of social order, upon which patterns of interactions can come to exist and institutionalise in practice. Table 4 presents these theoretical possibilities.

Table 4.

Patterns of interactions following matching relationship and interest types (institutional nexus).

Our focus is on three Institutional Environments: Constitutional order, Civil network and Competitive market. More than the other six environments in the above table, these three have, particularly in social practice within liberal democracies, evolved to empirically observable, institutionalized and resilient public governance patterns of coordinated interaction, operating at different levels and embracing supportive structures, mechanisms and procedures (e.g., countervailing powers, competition rules, social inclusion). They have become important objects of study applied in mainstream analytical frameworks, such as by Dahl [31], Powell [32], Thompson [33], Rhodes [34,35] and Ostrom [36]. (Note that, arguably, the other six discrete forms are generally seen, in liberal democracies, as less effective, efficient, legitimate and/or just in broadly shaping public governance, such as ‘private hierarchy’ (with legitimacy concerns) or public networks (with effectiveness and efficiency concerns). They may yet be relevant to specific settings regarding specific societal concerns.) We characterise these key types as follows:

- -

- Constitutional orders combine hierarchical relationships with pursuit of the public interest, assuming that the latter is best served when government holds the power to not only determine the public interest but also pursue this interest unilaterally, by command vis-à-vis citizens. Examples are municipalities, states and the EU.

- -

- Competitive markets combine exchange relationships with the pursuit of private interests, assuming that the latter are being best served through the market mechanism of consensual exchange in a competitive context. Examples are markets for CO2 emissions, for local commodities and for energy provision.

- -

- Civil networks combine communal relationships with the pursuit of social interests, assuming that the latter are best served through voluntary civil society cooperation in co-productive or sharing networks. Examples are the networks of NGO’s in religious, cultural, university and professional life, in welfare, care, political and social awareness and mobilisation.

In Table 5. The above three Institutional Environments are named, while adding some categories and specifics of characteristics that cannot be elaborated upon here.

Table 5.

Three types of institutional environments.

Acknowledged at Embeddedness level as generally accepted key concepts of games of public governance, all three environments are perceived to provide a proper balance on four dimensions of their workings in terms of legal governance of public service: effectiveness, efficiency, legitimacy and justice. (Note that these dimensions build upon public service dimensions from public administration literature, adding ‘justice’ (i.e., substantive or distributive/procedural justice) to ‘effectiveness’ (i.e., achieving objectives), ‘efficiency’ (i.e., cost utility; achievement at low(est) cost), ‘legitimacy’ (i.e., right to power in decision making) [37,38]. These dimensions are broadly similar to input legitimacy (participation, accountability, transparency) and output legitimacy (effective and efficient achievements) [39,40,41].) Each environment strikes a distinctive balance of it being functionally conducive to and resilient in a particular scope of public governance application, such as, traditionally: safety and security within a Constitutional order, private household goods within Competitive markets, and cultural and welfare activities through Civil networks. Evaluation, at Embeddeness-level, of a balanced institutional fit is relevant both from the individualist viewpoint (of private persons, groups and organisations), and from a collective viewpoint (of society in general)—and as such crucial to normative resilience. Over time societal acceptance of the workings of an environment may of course change, in general or particular to being suited to certain public governance challenges, causing a challenge to resilience, but perhaps also causing adaption, and perhaps even a shift between environments. (Note that the French revolution, for example, put an end to (acceptance of) Private hierarchy of enlightened despotism as a general mode of public governance.)

4.1.2. Interaction between Institutional Environments

As there are various Institutional Environments (at L2) and as we saw that there are shifts in governance that lead to a change in legal space for a given practice (or a new space for a new practice—such as following the establishment of a market for trading CO2 allowances), we need to understand how Institutional Environments interact.

First of all, in practice there will be very many personal unions across Institutional Environments because individuals, groups and organisations can take positions characteristic to relations within such environments. Members of a CES, are also consumers in various Competitive markets and citizens in various Constitutional orders. Personal unions do not formally change basic institutional rules. Informally though, practices may be affected, such as when being the owner of an energy company influences voting-behaviour of that owner as citizen in government elections or his willingness to become a member of some NGO. (Note that at some point, de facto ‘capture’ may indeed result, such as when the energy company owner becomes head of state, but ideally position rules (or boundary rules about entering such positions [36]) should safeguard against this.)

Secondly, and aside from personal unions, interaction between Institutional Environments may follow from regulatory interventions between them. While Institutional Environments have their own evolutionary momentum—of community development, markets coming into existence, and state formation—possibly as a matter of adaptive resilience responses to their functioning. This momentum may, however, also originate in or be impacted by regulatory interventions across environments. Governments in Constitutional orders are particularly known to be involved in this, as they often exert their regulatory influence upon the basic rules of competitive markets (e.g., introducing or amending property, contract and competition law) and of civil networks (e.g., introducing new forms of legal personality for societal enterprises). In the liberal democracy doctrine, all three environments exist in parallel—as against state doctrines where markets and networks are subordinately nested within the state. Although liberal Constitutional orders do come with legislative power to influence basic rules of markets and networks, the latter two are regarded as fundamentally autonomous in their basic workings and not hierarchically nested within the state. Hence the state has only limited powers to interfere, and should preferably use these powers only to foster their functioning, such as of markets from an ordoliberal perspective [42], and networks to advance participatory governance [43]. This does certainly not exclude the option of the state designing a new Institutional Environment, of either non-hierarchical types, to specific public interest objectives, such as a regulated market for trading CO2 allowances or a civil network for university life (or indeed for CESs). (Note that instead of using Constitutional order instruments, government thus uses instruments of a different Institutional Environment to attain public interest goals.) Furthermore, states are bound by Constitutional order requirements following the rule of law; involving principles of legality, legal certainty, equality, proportionality, and respect for fundamental rights, such as of property, association and voice. (Note that by contrast, totalitarian states assume primacy or dominance of the state over markets and civil society, as nested/subset Institutional Environments, rather as discretionary types of coordination within the state.)

Thirdly, parallelism between environments existing side-by-side, may lead to overlap in regulating the same or related interactions; perhaps complementary, but possibly in competition and in conflict [44]. States, markets and networks may put a different emphasis on the key interests of the energy trilemma, which in sum could be productive but equally unproductive to a properly balanced (i.e., effective, efficient, legitimate and just) public energy service. While competition and experimentalist governance, applying different modes of governance side-by-side, may lead to greater energy policy wisdom [45,46], it may also trigger the desire for the state to orchestrate public governance, such as by prescribing that there will be a Regulated energy market and/or that there will be a Community energy network. (Note that at orchestration the state is not an ‘unmoved mover’, and given the basic autonomy of markets and networks, the state can do little more than facilitate and incentivize. Conversely, leading actors within competitive markets and civil networks may exert regulatory influence upon basic rules of Constitutional orders. Not by hierarchy-based regulation, but rather through competition-and community-based regulation, the influence of which is more of an informal nature, such as in political bargaining, influencing member or consumer behaviour etc.) Such a regulatory intervention by government addresses relevant subsets of citizens, such as citizens as energy companies, as NGO-members or as energy consumers. While regulated within a Constitutional order, impacts go out to their position and scope of interactions within another environment, through positional unions. (Note that when assuming the existence of only two actor types with each mode (government/citizen; buyer/seller; NGO/member) and regulation addressing either one or both types (through the encompassing type of another environment), there would be three regulatory relations from each environment to the other, so six in all.)

4.1.3. Hybrid Institutional Environments

As is demonstrated by the earlier reference to the Regulated energy market, there may be hybrid Institutional Environments alongside the earlier mentioned ideal types. The normative integrity of such hybrids, particularly to how their legal space creates scope for consistent practices while combining contrasting interests and relation types, is a complex issue. It challenges normative alignment and resilience, as it has to allow for a functional practice at lower levels of governance—such as of intertwined hierarchical and exchange interactions. Hence, first of all, the concept of institutional hybridity needs to be clear.

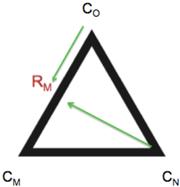

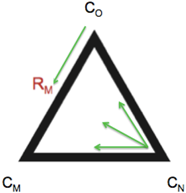

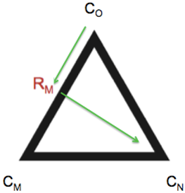

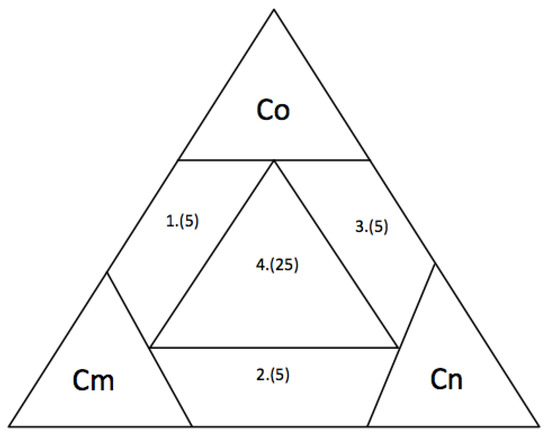

An Institutional Environment is considered hybrid when on either or both sides of its core institutional nexus, fusing its relationship and interest type, it combines two or three relation-types (i.e., command, exchange, cooperate) or two or three interest types (private, social, public). This means that hybridity may only concern the relationship type or the interest type, but it may also involve both typologies. (Note that hybridity is unilateral when only one side of the institutional nexus combines two or three different relationship types or interest types, and bilateral when both sides combine two or three different types. To have one relation type and one interest type on either side would merely amount to one out of the nine ideal type Institutional Environments.) When we limit our analysis to the ideal types of Constitutional orders, Competitive markets and Civil networks, then some ‘dual hybrids’ will combine relations and/or interests of two of these three ideal types and some ‘trial hybrids’ will combine relations and/or interests from all three ideal types. To picture this, we can use the well-known ‘Governance Triangle’, as in the below Figure 1. When we place Constitutional orders, Competitive markets and Civil networks at the angular points of this Triangle, then the dual hybrids are positioned along the sides, and trial hybrids are placed in the middle. We speak of plurality of hybrid forms on all sides and in the centre, because when we add up all possible hybrid nexus combinations there are in all 40 varieties—but this detailing need not distract us here. (Note that we assume symmetry, so that, for example, Co-Cm equals Cm-Co. Further nuance would lead to contingent detailing: see the supplement to this article for a full overview of the variety—43 in all, and 49 when including the other 6 pure environments.) The bigger picture is that the abovementioned hybrid of a regulated energy market would be placed along the left side-line, between Constitutional orders and Competitive markets. Similarly, one can think of hybrids that relate to Civil network characteristics; whether dual with Constitutional orders (as regulated energy networks) or with Competitive markets (as networked energy markets), or trial, combining characteristics of all ideal types (as societal energy platforms). (Note that these names are made up, as there is no official taxonomy.)

Figure 1.

Governance Triangle (with pure and hybrid governance modes of Institutional Environments). Legend: Co = Constitutional orders; Cm = Competitive markets; Cn = Civil networks; #1–4 are hybrid environments; Of those #1–3 are dual hybrids, combining characteristics of two pure Institutional Environments, and #4 is about trial hybrids, which combine characteristics of all three pure Institutional Environments; Between brackets are the theoretically possible hybrid variations per hybrid type.

The inherent complexity of hybrids, caused by combining different relation and/or interest types in their institutional nexus, is likely to give rise to transaction costs in safeguarding a balance between public service dimensions—securing at least some minimum of either effectiveness, efficiency, legitimacy and/or justice. In the context of application to public energy services more extreme benefits of hybridity, such as on effectively and efficiently securing a desired new balance in the energy trilemma, may outweigh the relative detriments, such as to (input) legitimacy and justice (including the perhaps additional costs of safeguarding the latter’s minimum content [37,38]. (Note, for example, that within a Regulated energy market, the price-mechanism is seen as an important asset to energy services (esp. affordability) but regulation is added to provide boundaries to the freedom of (not) contracting, not in service of the private interest (e.g., proper working of the market), but in service of a public interest value (e.g., equally affordable, reliable and sustainable energy provision). As long as there is clarity about which interest and which relation type is relevant, and incentives are properly aligned, the hybrid may be (even more) functional in properly balancing the public service dimensions (than its alternatives). The ultimate comparison would be one of ‘remediableness’ [20] in terms of ‘best at achieving alignment’.)

Hybrids are not about improving the functioning of the ideal types as such. When a Constitutional order legislator intervenes in the working of the Competitive market, such as by introducing competition and consumer protection law, this is about improving the functioning of its characteristic institutional nexus. When that same legislator initiates a shift in governance of energy services, by establishing a hybrid Regulated energy market, it is not merely improving the functioning of the market as market, but it is aimed to adjust the market institutional nexus, and hence the normative integrity, to serve mixed interests (both public and private) through mixed relations (both hierarchical and exchange), to safeguard reliable and universal access, while improving affordability through efficient profit-based, demand driven exchange transactions.

Against this backdrop, given that our focus is on the shift towards accommodating CESs, we need answers to the following key questions:

- Are CESs are accommodated by a legal space characteristic of the ideal type Civil energy network (Cen), or rather those of some (dual or trial) hybrid?

- In what way does the mode found in answering a. differ from the existing hybrid Regulated energy market mode (Rem)?

- Is it possible for these modes (from a. and b./Rem) to co-exist as (perhaps overlapping) parallel Institutional Environments, or perhaps combined as a dedicated hybrid environment?

In relation to question c. additional questions pop-up. Would a hybrid environment that overarches the Regulated energy market and CESs networks, through enabling and allowing energy transactions between energy companies, governments and CESs lead to a functional balance, or would such an arrangement ultimately risk sacrificing legitimacy to efficiency, by placing affordability above reliability and sustainability? In other words, would energy democratization fall victim to the desire for expansion of renewable energy services? Would things be different when institutional environments (i.e., Rem-Cen) are kept separate? In such a parallel setting, would there still be a legal scope for CESs, as NGOs with prosumer-members, to hold the position of energy company within a Regulated energy market? Or, conversely, could such energy companies and governments, be the owner or financier of a CESs positioned within Civil society—perhaps to reduce NIMBY-ism?

As follows from Section 4.1.2, with separate environments, the possibility for cross-environment interaction depends on whether there is overlap through positional unions, manifesting when the same or related interactions are regulated by actors from different environments. Such overlap can be one of nesting (i.e., hierarchically—one being the exception to the other) or of parallelism (i.e., in competition or complementary). When overlaps are (legally) precluded, as positions cannot be held across environments, then a state of ‘peaceful parallelism’ could follow. For example, when reciprocal arrangements exist whereby Regulated energy market conditions preclude CES-prosumerism, while Civil energy network conditions preclude commercial energy company activity, including ownership of CESs. Whether such ‘peaceful parallelism’ would help to foster CESs is another matter. Again, aside parallelism there is the option of nesting, such as when the legal space of a Regulated market holds some specifically defined pockets of legal space for Civil energy networks, as a mode of exceptional practice, under particular conditions. (Note that this is similar to how it could be made possible to have pockets for agreements between groups of producers and NGOs on sustainable production that would come at higher consumer costs. Such pockets would entail a separate scope for a hybrid competitive market/civil network regime, made possible through a Constitutional order intervention in the competition rules of Competitive markets.)

It follows from the above that a key question of this article is whether the separation between providers and consumers of energy, within the vertically unbundled and exchange driven Regulated energy market, can also (be made to) agree with the concept of (cooperative) ‘prosumerism’ in Civil energy networks—in parallel, nested or as an overarching hybrid. To this end we need to not only understand that there are (discrete and hybrid) types of Institutional Environments, at some level (L2) of governance, but we must also understand the logic of multi-actor collective action in and, particularly, between various levels of governance.

4.2. Modes of Governance, Collective Action Situations and Institutional Choice

Collective action, more or less orchestrated, lies at the basis of Institutional Environments, and once established, basic rules of Institutional Environments orchestrate subsequent collective action. Once established, a Regulated energy market projects and prescribes an arena for TSOs, DSOs, energy regulators, energy companies, brokers and aggregators, as well as energy consumers to enter into interactions following enabling and constraining rules characteristic to this environment. Upon these interactions energy is de facto being generated, distributed, supplied and consumed.

In general, for an Institutional Environment to come into existence is either as a matter of evolution in practice (e.g., a local food market), design (e.g., the EU emissions trading scheme), or combinations of both (e.g., government and constitution building) [24] (p. 598). (Note that one may argue that conception of institutional environments typically takes place at a ‘meta-constitutional level’, including the evolution of informal institutive rules, so that formal instantiation is mostly a matter of recognition (and perhaps some modification) at constitutional level. This fits with Williamson’s [24] writing that the structures at level 2 (Institutional environment) “are partly the product of evolutionary processes, but design opportunities are also posed.”, and that level 2 is about moving from informal to formal rules.) Whichever applies, evolution and/or design, once established they come with conditions in formal and informal rules, norms and strategies, which together structure different types of Institutional Environments as collective ‘action situation’ [36]. (Following Ostrom’s Institutional Analysis and Development (IAD) framework [36], instantiation of an Institutional Environment as an action situation in practice, such as an energy market, will depend on exogenous factors, such as biophysical/material conditions (e.g., operating an energy service system), attributes of the community (e.g., views on energy justice) and rules-in-use (as relied upon in practice, either or not upon legal rules).)

Similar to Williamson’s levels of social analysis, action situations in Ostrom’s IAD framework [30] are placed at different levels. (In IAD these actions are about establishing and maintaining common pool recourses, such as shared fishing ponds, but we believe they can also apply to collective challenges of concerted action towards public energy services [47].) The (bottom level) ‘Operational level’ concerns de facto collective actions relevant to the de facto generation, delivery and use of energy. The rules of operational game-play, whether they feature CESs or large energy utilities, are set at the ‘Collective choice level’, following relevant stakeholders’ decisions establishing the organisations, permits, and contracts that determine how energy services are de facto provided at Operational level. In turn, interactions at ‘Constitutional level’, such as legislating an energy act, are necessary to provide the empowering ‘rules of the game’ that enable the aforementioned collective choice interactions. Institutional Environment patterns at Constitutional level follow a particular game-concept that is informally settled at ‘Meta-constitutional level’. Thus embedded, Constitutional order interactions may lead to a Regulated energy market, Competitive market interactions could lead to a setting for establishing private energy service standards, and interactions in Civil networks could settle community boundaries regarding decision-making on sharing a local hydropower resource.

Table 6 provides a layered picture of these action situations, similar to the Table 2 model of Williamson. (Ostrom has mostly pictured her levels with the Operational Situation at the top and the others below. [36]. Given an upside-down framing in Polski and Ostrom [48] (p. 40) and our earlier use of Williamson’s model, we place the Operational Situation at the bottom.)

Table 6.

Levels of action situations.

Similar to Williamson’s model, In IAD action situations at different levels have a different pace of producing outcomes. (Ostrom herself pointed at the similarity between her and Williamson’s model [36].) At higher levels change is more difficult and more costly, which emphasizes absorptive over adaptive resilience, through the “stability of mutual expectations among individuals interacting at (...) [these levels].” [36] (p. 58). The pace of change of institutional settings will, however, depend on the positional relations between the levels; also depending on whether the same persons hold positions at different levels.

From a legal perspective, interactions within and relations between action situations at different levels may be understood as follows:

- (1.)

- At Metaconstitutional level, so-called rules of recognition [6] develop as foundation for legal order and for the recognition of the concept of Institutional Environments.

- (2.)

- At Constitutional level, Institutional Environments are instantiated, related positions generated (e.g., a legislator) and a legal space, particularly regarding rules of power, made available to Collective choice interactions. (Following Von Wright [49], Ostrom distinguishes a particular categories of rules called ‘generative rules’ of the form: “let there be an X.”, which create legally relevant positions held in Action situations. [36] (p. 138).) Depending on existing needs, environments may serve a general purpose, such as a legal regime for Competitive markets in general, or a specific purpose, such as a legislative regime for Regulated energy markets.

- (3.)

- At Collective choice level, final rules of conduct are set, upon powers granted at the above level, to arrange legal space for Operational level positions and factual interactions. Upon, for example, a Regulated energy market’s rules of the game following a Constitutional level Energy Act, at Collective choice level energy regulators, energy companies, and NGOs would be established, permits granted and contracts signed, also with energy consumers—so as to provide the rules of game-play/conduct.

- (4.)

- At Operational level, at level 4, but within the level 3 rules, factual activities take place, such as the making and maintenance of energy grids, and the generation, distribution and use of energy, such as within a CESs. (Note that Ostrom has explained that it is possible to extend the number of levels as high “as needed until we hit rock bottom—the biophysical world.” [36] (p. 58), which fits the often many legal levels involved with rule making at different levels.)

Currently, the push for legally facilitating CESs is both a bottom-up and a top-down process. Bottom-up, persons involved at operational level in exploring the possibilities for CES are faced with a regulatory disconnect [13,14,50]: existing Regulated market-based regulation, made at higher levels, does not allow for (i.e., resists) group-prosumerism. Hence these parties call for change. (Note that to use the term ‘regulatory disconnect’ has a pejorative meaning, suggesting that it should not be the case. We must keep in mind that some perceived disconnects are actually well-considered barriers to practices that may be technologically possible and desirable to some, but are nonetheless forbidden—e.g., human cloning, but perhaps also CESs within a Regulated energy market.) Top-down, persons in top-level strategic positions may advocate new future proof/smart energy modes of governance to enhance technological and social change at lower levels. Wherever the process is initiated, a successful shift will require that legal space available at different levels align. Possibly such shifts are brought about by first creating across-level regimes for CES experiments [35]. Aside from energy transitions incentivized by a Constitutional order legislative intervention, orchestration may also follow from strategic coordination in a trial hybrid, such as a societal energy platform, as an Institutional Environment engaging public energy offices, energy companies and energy NGO’s, towards aligning their objectives and efforts. In the Netherlands this type of trial/tripartite coordination, is known as ‘poldering’, and has, inter alia, lead to a National Energy Covenant on the energy transition [51]. Of course with such platforms the question does rise as to the bindingness of their outcomes in Collective choice follow-up and Operational level practice—as a matter of normative alignment and resilience. This is a question that relates to the normative side of modes of governance in a multi-level perspective, and particularly the normative dimension of Institutional Environments. The next subparagraph is about this dimension.

4.3. Legal Institutions (Esp. of the Third Kind)

The impact of institutional shifts in energy services requires proper understanding of when, why and how Institutional Environments and Governance Structures can, next to their empirical dimension, also have a normative dimension [8] (pp. 349–366). So far we merely alluded to the legal dimension of Institutional Environments and the impact of their legal space on the actors’ liberties and abilities holding positions within them. Clearly, actors have a stake in the realization of a proper balance of public service dimensions preordained by Institutional Environment rules of the game. As individual persons, groups or organizations actors are members of the polity that has a societal interest in institutionalizing such balance, as it should also be conducive and resilient with respect to their individual interests. Further, actors are crucial to personal and positional unions regarding interactions and relations between overlapping Institutional Environments. Finally, actors take positions in, perhaps various action situations at different IAD-levels. As a final theoretical step we will now look at the legal governance dimension. What is the nature of legal space of Institutional Environments and of the legal position of actors, particularly at Constitutional and Collective choice levels, particularly regarding institutional shifts that disruptively change legal space to become more conducive and resilient to an ‘energy trilemma balance’ that accommodates CES-performance?

4.3.1. Legal Institutions

Institutional Legal Theory [52,53,54] relates to normative patterns of behaviour that are guided by regimes that cluster relevant legal rules. Adulthood, ownership, public authority, contracts, permits and companies are examples of phenomena that operate on the basis of such clusters of rules, also referred to as ‘legal regimes’. They are purported to operate as if they are mere empirically observable social institutions, but do so upon legal prescription, either by design or by recognition, of a pattern of behaviour that can be instantiated at a given time and place within a legal order—such as informal agreements sometimes being understood as legal contracts. Their understanding as legal institution builds upon four basic prescriptive ‘word-to-world’ rule-types applicable to the particular patterns of behaviour [52,54]:

- -

- ‘constitutive rules’ concerning recognition or design of a social institution that is in existence or could become existent, as a type of legal institution within a given legal order, such as of contracts (i.e., recognised) or of trading emission rights (designed);

- -

- ‘institutive rules’ on how an instance of a type of legal institution can be brought about, such as about how to a permit can be issued by an energy regulator, or how to establish such a regulator.

- -

- ‘consequential rules’ which apply upon individual legal institutions as instantiated, such as on conditions to powers of an energy regulator, or duties and claims of parties to an energy contract.

- -

- ‘terminative rules’ on how an instance of a type of legal institution can be ended, such as about how to withdraw an energy distribution permit or to dissolve an energy company.

Strictly taken, we only speak of a legal space as a legal institution when the prescribed pattern of behaviour is defined by at least the last three types of rules—assuming that the first would be implicit to the second. A mere composite set of energy law rules will define the legal space for a functional legal practice, of all events with energy law significance, but does not make for a legal institution. Only a system of such rules that prescribes a particular coherent pattern of behaviour that can be instantiated (repeatedly), possibly with particular legal consequences (as dedicated legal space) to each instantiation, and which can be terminated, counts as legal institution, such as an energy certificates regime or a regime for CESs.

Ruiter offers a conceptualization of two orders of legal institutions [8] [54], (pp. 1–4). The first order is of institutions about legal attributes of persons (e.g., public authority), of objects (e.g., a monument) and of relations between persons (e.g., contracts, permits), between a person and an object (e.g., ownership) and between objects (e.g., an easement). The second order consists of legal persons (i.e., personifications of legal relations to make legal entities; e.g., enterprises and associations) and legal objects (i.e., legal relations that become objects of legal relations; e.g., tradable rights/claims and legal powers). Lammers and Heldeweg [10] posit a third order of related or contextualized relationships: Institutional Environments, each providing a legal regime of a particular relationship-interest nexus as a context in which first and second order legal institutions function.

4.3.2. Legal Persons as Legal Institutions

Second order legal institutions of legal persons are relevant to energy governance to understand the legal nature of TSOs and DSOs, of energy regulators, companies, brokers and aggregators, and also of group-prosumers, organized in communities or collectives. (Note that in group-consumerism the collective aspect is prevalent in, at least, energy generation, whereas prosumerism as a general term may also concern individuals with private solar panels who, actually or virtually, consume their own power, while their surplus may be fed into the main grid.) Such nature is key to their fit with positions they may hold in and across different Institutional Environments. Ruiter points at three basic forms [9] and [55] (pp. 102–103): (1) associations of members, such as a green energy action platform; (2) corporations with shareholding, such as an energy company; (3) foundations with designated means, such as a green energy subsidy fund. Again, there may be hybrids, such as the co-operative. An example of the latter is a private community smart grid energy initiative, mixing attributes of an association and a corporation, with owner/shareholding membership. Once established, the exact content of these core attributes will follow from the consequential rules applicable to its (pure/discrete or hybrid) type, with further specification to its particular instantiation, for example as ‘Energy community X’, established as association of members of type Y-persons, at some time ‘T’ in jurisdiction ‘Y’.

4.3.3. Institutional Environments as Legal Institutions (Sui Generis)

Normative resilience in terms of absorptive legal resistance and recovery is relevant to keep legal persons from unlawfully taking positions and pursuing interests infringing on the consequential rules of the Institutional Environment in which they are legally positioned: e.g., a prosumerist entity operating in a Competitive market environment where production and consumption shall be separate. (Note that in the IAD-framework this state of affairs could either be seen as to go against ‘boundary rules’ (rules determining requirements, substantive and/or procedural, to take a position), or ‘choice rules’ (about what holders in a particular position are required or allowed to do) [36].) At the same time, as a matter of adaptive resilience, governance shifts can bring disruptive legal change whereby another type of Institutional Environment, with a distinctly different legal space, becomes applicable to (legal) persons and their interactions (see Section 3.2).

A shift in governance of Institutional Environments can take place in several ways and with different consequences.

- -

- A shift can follow from mere practice, by a change in the empirically displayed pattern of behaviour, as rules-in-use to which actors refer in justification of their actions [30]—such as when groups of people de facto disconnect from the electricity grid and start unlawfully sharing the collectively generated energy (i.e., group prosumerism).

- -

- A shift can also follow (only) from a change in key legal rules-in-form, such as when an Energy Act henceforth allows previously prohibited prosumerism (experiments).

The latter type of shift has our legal governance interest—which includes attention to the first shift as a matter of normative resilience—to counterfactually absorb or to adapt and legalize. Institutive, consequential and terminative rules are important to legal governance shifts because together they are key to legally bringing about a (change in) legal space with a (new) normative integrity. An example would be to transform a Regulated energy market by lifting the ban in on group-prosumerism when performed within a community association. The most common way of bringing about such a shift in legal governance is by legal act. The EU Regulated energy market, for example, was instantiated by a sequence of legislative acts at Constitutional level, both at EU and at Member State level. A next legislative act could be to legalize already existing unlawful CESs, by creating a Community energy network legal space.

Of course to consider creating a legal institution as a type of legal space for existing or desired patterns of behaviour requires justification in terms of societal significance and (expected) failure of such behaviour to ensue—for else why not leave such practice to follow from informal incentives only. (Consider, for example, that there is usually no need for contract law rules for agreements between children or for family-members to have dinner.) The policy aim of achieving a public service balance regarding the energy trilemma and failure of the Regulated energy market to do so, could provide such justification. Still, this does imply that the mere empirically observed existence of an Institutional Environment, for example a configuration of CESs and related energy services, is not necessarily indicative of a legal institution of a Civil energy network, as it could be a mere informal practice. When it does concern a characteristic legal space, this could indeed follow from a concept of a legal institution with Civil network characteristics, upon elaborate institutive, consequential and terminative rules; similar to regimes in state constitutions about the making and functioning of municipality Constitutional orders. Rules to a legal institution could also be more implicit. In liberal legal orders we find that the existence of the private Institutional Environments of markets and civil society are constitutionally acknowledged either explicitly or implicitly. Perhaps only as a constitutive constitutional rule, listing the conditions upon which more detailed rules, institutive and consequential, are possible in legislative, regulatory and court practice. (Note that there is a fundamental debate behind this sentence that is however not immediately relevant to this article. The crucial element is that there is a constitutive concept from which there is a normative logic regarding how markets are made or acknowledged and what operative/consequential rules apply to their functioning. Further reading see [56].)

Implicit to the afore is that normative alignment between action situation settings and outcomes at different institutional levels, as discussed in par 4.2, is key also to the making and functioning of legal institutions. When informal interactions at Metaconstitutional level lead to some legal order, this will come with concepts of basic first and second order legal institutions, such as legal personality, property and contract. When legal order comes with some form of a(n un)written ‘Constitution’, it thereby conceptualizes and instantiates a Constitutional order. When such order expresses a liberal state doctrine, its Constitution will also recognize the existence of the autonomous environments of Competitive markets and of Civil networks. If deemed necessary, instantiation of the latter as legal institutions, with clear consequential rules, is likely to follow at Constitutional level. Interactions at that level, such as state legislative action following constitutional rules of power (Rules respectful of separation and decentralization of power, and of human rights.) may, for example, lead to the conceptualization and instantiation of a Regulated energy market. Instantiation of accompanying legal persons, such as an energy regulator may happen in the same legislative act, such as an Energy Act, but instantiation may also be left to interactions within action situations at Collective choice level. That would also be the level appropriate to establishing legal persons for TSOs and DSOs, and the granting of permits and signing of relational contracts—all of which in keeping with institutive and rules of relevant to those types of legal institutions (e.g., rules on contracting), but also to the consequential rules of that Energy Act (e.g., maximum tariffs in energy contracts). Finally, the rules of conduct included in the legal institutions instantiated at Collective choice level (e.g., an energy supply permit) will further channel lawful factual behaviour at Operational level (e.g., providing energy services), making for an operational liberty space (e.g., prohibition or permission of group prosumerism).

All of this is to say, firstly, that legal space, fitting to action situations at each level results as output from an action situation at the next higher level. Secondly, it demonstrates that the legal space for instantiating legal persons or legal relations and other 1st and 2nd order legal institutions is legally either enabled or constrained by an applicable Institutional Environment as instantiated at a higher level of collective action, most likely at Constitutional level. When a Regulated energy market holds regulatory provisions requiring vertical unbundling of grid management, production and delivery, universal access, and licenses for energy delivery, these consequential rules of conduct limit legal ability space vis-à-vis performing legal acts (e.g., of signing an energy contract), and of legal liberty space, such as that of community organisations wanting to establish a prosumer energy grid.

Building upon the ‘ILTIAD’-model of Lammers and Heldeweg [10], Table 7 pictures the interconnection between action situations at different levels.

Table 7.

Connected action situation levels.

5. Institutional Alignment—Some Reflections on Practice

Two studies of renewable energy policy practice triggered interest in the legal governance aspects of normative resilience, and reason to embark on the legal governance analysis presented in the afore Section 4, and to the study, presented in the next Section 6, of the Dutch regime for experimentation with community renewable energy services. Both studies are briefly discussed in the below because despite their selection may be somewhat arbitrary, they do no more nor less than paint the picture of the key legal governance issues of normative alignment in the energy transition practice. (Note that the relevant authors gave explicit permission to the use of (quotes from) their papers in this particular article.)

5.1. Community Solar Programs—Expansion or Democratization?

As an introduction to strategies of enhancing CESs, Hoffman and High-Pippert [17] discuss the case of ‘duelling frames’ in the 2013 US-State of Minnesota’s Solar Garden Program. This statutory program was focused on enhancing the deployment of shared solar projects, also known as ‘solar gardens’. A solar garden would involve at least three actors: a developer (to build and own the array), a utility (agreeing to purchase power generated by the array), and subscribers (agreeing to purchase a portion of the output) [17] (p. 4). Solar gardens were not allowed to have a ‘nameplate capacity’ of over one megawatt (MW), and had to be designed to serve the energy use of at least five subscribers, each of which with a maximum share of 40% of the array’s total energy output. Furthermore, these subscribers had to be customers of the utility participating in the project and residents of the county where the solar garden was located. The largest energy provider in the state of Minnesota, ‘Xcel Energy’, was under statutory requirement to create a solar garden program, but other cooperative utilities also participated in the implementation.