Abstract

In the urban development policy in China, city brands play an important role in setting targets for Chinese cities. These economic city brands, however, are not produced in an institutional vacuum: they are embedded in the visions national, provincial and municipal governments have for these cities, i.e., on multi-level governance. In this paper, a data-intense analysis of economic city branding practices has been conducted in the Greater Pearl River Delta, taking into account national, provincial and municipal documents in socio-economic, urban and land use planning. Evidence of economic and ecological initiatives through branding at the level of symbolic urban projects, such as new towns, has also been examined. It transpires that Hong Kong, Macau, Guangzhou and Shenzhen have adopted more sophisticated economic brand identities than the others and the reflection of brand-related targets from their actual projects is also more credible. While China’s national plans focus primarily on Hong Kong and Macau, provincial documents place more emphasis on the wealthier cities on the mainland (Shenzhen and Guangzhou). The other cities attract less attention and have more freedom to adopt economic city brands, but their efforts to live up to their promise are quite limited due to their weak financial position.

1. Introduction

China, while becoming the second largest economy in the world, experienced quite serious environmental degradation in the last a few decades [1,2]. Taking account of these mounting problems, the Chinese central government has chosen to prioritize “ecological civilization”, which involves a synthesis of economic, educational, political, agricultural, and other reforms towards a sustainable society [3]. The term “ecological civilization” first appeared in 2007, in a report to the 17th National People’s Congress. At the Third Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee in 2013, “ecological civilization reforms” were once again stressed by President Xi Jinping. However, although it is a key national policy goal, since China considers it an imperative not to let ecological preservation go at the expense of economic growth, the absorption of environmental considerations into the broader developmental strategy has taken the shape of a discourse along the lines of ‘ecological modernization’. It means producing higher economic value with fewer natural resources, thus increasing eco-efficiency in industrial production and consumption [4,5,6]. In most cases, this does not only include various forms of industrial upgrading, but also a shift from manufacturing to services. Thus far, the desire to transition in this direction has been most notable in the more developed Eastern and Southern regions of China, and in the Greater Pearl River Delta (GPRD) in particular. Most of the eleven cities in the region to which Guangzhou, Shenzhen and Hong Kong belong, are making strong efforts to try and phase out heavy and polluting industries and replace them with lighter and less damaging forms of manufacturing and high-tech services. Alongside this, they promote environmental protection, provide smart infrastructures, and aim to build an attractive liveable environment.

This transformation is far from being an automatic transition: a variety of policy measures has been deployed to encourage it and speed it up. Government communication is conceived as a policy tool or instrument, that is, as a means to give effect to policy goals [7]. In this line of argument, city branding by local governments has been recognized as a policy instrument by various scholars, especially for European cases [8]. Due to fiercer competition among cities and towns in China, the policies of local governments should be more eco-friendly to attract investors, industry, residents and visitors. In this context, economic city brands, i.e., brands specifically related to the industrial profile, are considered an important instrument to support economic and ecological initiatives undertaken by local governments. In planning documents, the terms “eco city”, “low-carbon city”, “smart city” and “resilient city” are paramount. This begs the following questions:

- (1)

- how is this policy instrument of economic city branding utilized by municipalities?

- (2)

- in which intergovernmental context can its use be explained, given the fact that it is expected to contribute to the broader goals of an ecological civilization, and

- (3)

- to what extent can positive effects of the application of economic city brands be discerned in physical developments on the ground?

Economic city brands are partly chosen by municipalities because they are able to adopt certain profiles by themselves, based on their industrial and cultural background and aspirations for future development. It is also possible that cities choose their brands copying from other cities [9]. In this paper, we argue that these choices are partly influenced by guidance from national and provincial governments, as they issue various national and provincial policies that local governments are supposed to adopt. This inter-governmental relationship of economic city brands has been rarely studied, but is especially meaningful in national administrative contexts that are as top-down and hierarchical as the Chinese one is, at least in name. A multilevel governance (MLG) perspective offers insight in the way local governments navigate between the national eco-civilization objectives and practical urban development needs at the district level. The latter then adds the aspect of actual reflection from the symbolic urban projects on the ground: do the emerging symbolic urban projects in any way live up to the promise of their economic city brands?

In this article, we will address the above mentioned questions. It consists of seven sections, of which this introduction is the first. In Section 2, we will focus on the theoretical debate surrounding city branding, and how multilevel governance (MLG) influences the decision making on city branding. Section 3 subsequently unfolds the methodology which we have used in our data collection. Section 4 provides the evidence as to which economic city brands were chosen by the eleven cities in the GPRD, nine in the mainland part of the Pearl River Delta and two which are known as the Special Administration Regions of Hong Kong and Macau. Section 5 inserts the MLG perspective into the discussion by introducing the urban planning system and its key actors, and examines the impact the national and provincial governments have on municipal economic city branding practices. Section 6 then takes us down to the level of symbolic urban projects. In it, we make an attempt to establish the congruence between chosen economic city brands and their impact on a particular and rather dominant type of urban development projects, new towns. With observations at that level, we have stretched all the way from national eco-civilization goals as formulated from the central government through local economic city profiles accommodating ecological modernization to physical investment projects acting as profit centers for developers. In Section 7, we will wrap up with conclusions.

2. City Branding and Multi-Level Governance

2.1. City Branding

City branding as a topic has been debated in a variety of disciplines, especially in public policy [10,11,12,13], marketing [14,15,16,17] and political economy [18]. Recent books also deal with city branding in an interdisciplinary way [19,20,21,22,23,24], whereas a more specific and singular focus on the nature of city branding as an entrepreneurial strategy for cities is offered by some scholars [8,18].

In general, a city brand has been defined as the unique, multi-dimensional blend of elements, which provide the city with culturally grounded differentiation and relevance for all of its target audiences [21]. Branding is thus about conveying a brand or symbolic essence of a city to target audiences for strategic gain [25,26].

In this article, the focus is a broadly defined economic development brand [15], which is in the context of urban economic development policy. As many cities in China strive to obtain international fame, they need to increase and capitalize on their attractiveness [27]. With the strong will from city governments to control their city brands, there is always a power struggle between brand creator and brand receiver. Thus, it is necessary to distinguish between desired and registered brands [28]. The idea of the latter includes not only what the city government wants or the perceptions of narrowly defined targets groups, but also inputs from various key stakeholders [29,30]. Brands are diffused when customers, outsiders and the media discuss these cases in an open environment, but they may also risk becoming more diffuse [31,32].

This research will focus on desired economic city branding, which is what governments do in their urban and economic development plans. A number of elements, features and beneficial attributes cities have, are stressed. As the core element of a brand, identity reflects how producers want their brand to be perceived by the outside world. Seen in this way, a branded product requires a brand identity, which differentiates it from others in a defined competitive area [33]. Similarly, city brand identity differentiates a given city from other cities, combining its spatial configuration and cultural values in a complex way [25]. Cities benefit from a clear awareness of their major strengths and assets as well as a vision for the future [34].

In a broad sense, city branding not merely refers to city brands as found in brochures and formal policy documents, but also to real life activities. As branding can also be regarded as a mode of communication, both the formal intentional communication (advertising, public relations, graphic design etc.), and informal ones (word of mouth), rely on the actions of cities in the beginning [35]. In other words, only city branding will not make a better city, but making a better city will create a better reputation.

In our empirical study below, we will focus on the consistency of urban development strategies (brand-related expressions) and the symbolic actions connected to them. In line with Anholt’s analysis of national brands, we assume that effective execution of a strategy must be coupled with frequent symbolic actions if it is to result in an enhanced reputation in the end [19]. In the context of cities, brand-related expressions in urban and economic planning documents show the self-perception of these cities. Symbolic actions are a particular species of the effective execution of this strategy that happens to have intrinsic communicative power. They might be innovations, structures, legislation, reforms, investments, institutions, or policies, which are emblematic of the strategy of city [20].

The symbolic actions of cities based on their city brands include many aspects, including both spatial and non-spatial interventions [36,37,38]. Spatial interventions aim to improve the physical quality of the city, such as large-scale redevelopment and infrastructure projects. Many scholars choose to study the interventions on the ground through urban design, architecture [37], green spaces and generally public spaces in the city [39]. New town projects are regarded as the exemplar of urban development strategy in China, and can thus be understood as symbolic urban projects.

To conclude, we will be focusing on desired economic city brands as formulated by local governments, and further analyze the intergovernmental context in which they are chosen as well as their impact on the ground.

2.2. Multi-Level Governance

City branding is considered a response to intensified inter-urban competition [11,12,40,41]. However, city branding practices are complex, due to the variety of rationales behind the brands and the context these brands are embedded in [42]. This is particularly true in China, where economic city brands are used as a policy tool in an intergovernmental context. Policy making is still influenced by the legacy of state socialism, and local governments are influenced in their policy formulation by the central and provincial governments [43].

Multi-level governance has emerged as an approach to understanding the dynamic inter-relationship within and between different levels of governance and government [44,45]. Economic city branding in an intergovernmental context thus refers to the creation of economic city profiles in the interactions between municipal and higher level governments, as well as to the reflection of these profiles in flagship projects, which are urban projects primarily carried out by district governments and developers ‘below’ the municipal government.

Multilevel governance can typically be analyzed vertically [46]. It essentially combines top-down and bottom-up actions between interdependent levels of government. This is relevant to China, since its urban planning system is also based on the idea of command and control regulation, inherited from China’s planned economy and hierarchical political system [47]. Some earlier studies also characterize governance in China as predominantly top-down (from national to subnational), with subnational (provincial and municipal) governments merely being held responsible for implementing national mandates [48,49].

However, in city branding processes, things are rarely as uncomplicated as that. Municipal governments are not mere automatic executors of national goals, but can make their own economic city brand choices within certain margins. They are required to take national goals and guidelines into account and convert them into targets applicable to their own level, but also take the freedom to consider local economic growth and other needs and wishes when choosing their desired brand identity and city profiles. To attract investors, clean companies and talented workforce, local governments compete with each other and give their economic branding their own specific color [50,51]. Consequently, guidance provided by higher tiers of governments and local circumstances and preferences intersect when developing economic city brands, and below we will examine how these influences are interwoven with each other in China.

In the context of multi-level governance in China, the most accessible sources for these desired economic brands are the public planning documents at the various governmental levels. To express urban development strategies is one of the main motivations to draft urban and economic planning documents in the Chinese context [52]. The economic city profiles, which are aggregate city profiles distilled from policy documents from independent academic researchers, may not necessarily be the same desired brand by local government. However, this illustrates the different aspects that governments focus on and how they deviate from each other. Through relating (1) economic city profile choices made by municipal governments in their own municipal planning documents with (2) the direction higher tiers of government offer for the territories of these respective municipalities in their national and provincial planning documents and (3) the labelling used for brand flagship projects, we can derive a systematic understanding of the multi-level governance on economic city profiles.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Source

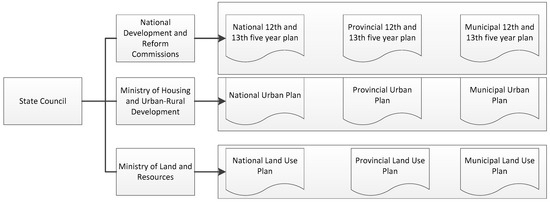

In Chinese urban planning, three types of plans are important for urban and regional development. These are the Five Year Economic and Social Plan, the Urban Master Plan and the Land Use Plan. Specifically, the Five Year Plan reflects the strategic and comprehensive planning for the economic and social development of a city; it is drafted by the National, Provincial and Municipal Development and Reform Commissions (NDRC). The Urban Master Plan elaborates on the spatial structure and urban function of the city by the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development (MOHURD) at the various tiers of government. The Land Use Plans aim to control land use by allocating land to different functions in a detailed way by the Ministry of Land and Resources (MLR) at the national, provincial and municipal levels [47,53]. All three are relevant to explore the desired brand identity and economic city profiles of GPRD cities. The plans and their issuing institutions in China are shown in Figure 1 (These planning documents of mainland cities in China can be found in a database (The doi of the file in 4TU database is: 10.4121/uuid:ddaabf62-530e-4df2-a0b2-30c75679c7e7)). As for Urban System or Master Plans, we should add here that they are the most important formal documents in urban planning and guide the drafting of detailed plans.

Figure 1.

The planning documents and their issuing institutions in mainland China [52,54].

The National Economic and Social Five Year Plan is issued by the NDRC before its provincial equivalent is issued by its provincial counterpart. Similarly, the municipal Five Year Plan is drafted following the leads of the national and provincial Five Year Plans (Supplementary Materials). The same top-down principles apply to the Urban Plan and Land Use Plan. Therefore, national and provincial plans provide the context within which the GPRD municipalities set their city development targets.

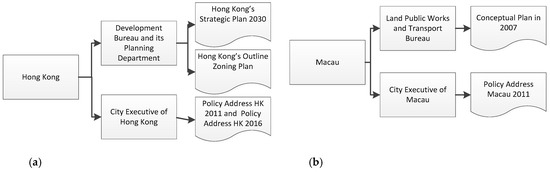

The planning context in Hong Kong and Macau is different from the one in the mainland cities, which is demonstrated in Figure 2. Hong Kong’s policies on urban transformation are primarily based on its strategic plan ‘Hong Kong 2030 planning vision and strategy’, prepared by its Development Bureau and its Planning Department, a policy document similar to that of other global cities like London, New York and Singapore [55]. Due to political tensions and public sentiments, the five year plan was not adopted directly in Hong Kong as it was in Macao. The Yearly Policy Address can be seen to shed recent direction of its social and economic development. The Policy Address is drafted by the City Executive of Hong Kong and is consulted with other departments (same level). Similar to Hong Kong 2030, Macau issued its Conceptual Plan in 2007 [56]. Interestingly, more recently, Macau decided to follow the mainland approach and drafted its own Five Year Plan (2016–2020) [57], which can be understood as a symbol of emerging integration.

Figure 2.

The planning documents and their issuing institutions in its two special administrative regions (a) the planning documents and their issuing institutions in Hong Kong [55,58,59,60]; (b) the planning documents and their issuing institutions in Macau [56,61].

3.2. Qualitative Data Analysis

Our systematic analysis of economic city branding in the Greater Pearl River Delta embedded within the wider intergovernmental practice in China took place in three distinct steps, each described in a separate chapter:

Step 1: Economic city brand identities

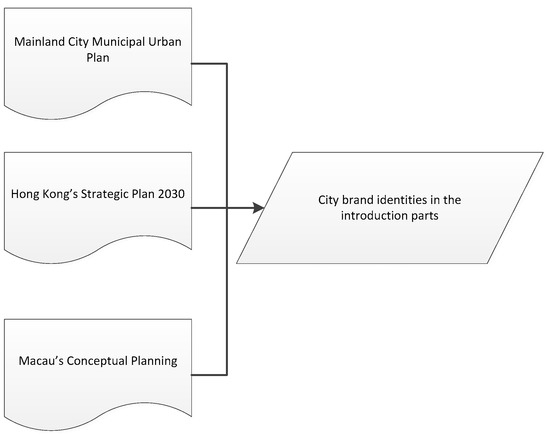

Our analysis begins with an economic and demographic introduction of the eleven cities in the GPRD which constitute our entry point in Section 4. We first map how they present themselves in characteristic sentences or quotes that reveal how they see their economic brand identity (see Table A1). These economic brand identities were collected from the introduction from Urban Master Plans in the case of the mainland cities. These plans are the most important formal documents in urban planning, undergo several rounds of review from different levels of governments and used as the most important reference to understand city band identities in China. In the case of two Special Administrative Regions, Hong Kong and Macau, we based their ideas on their equivalent planning documents, as illustrated in Figure 3. These documents are in English as they are more referred to by local planners.

Figure 3.

Economic city brand identities from the municipal planning documents.

The result of step 1 is an overview of the city brand identities for all eleven GPRD cities, which may indicate their current self-perception and wished future course of development.

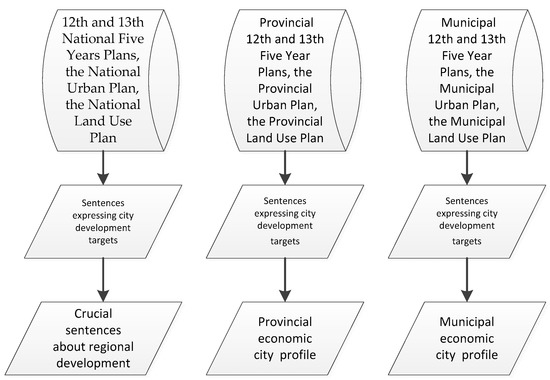

Step 2: National and provincial planning guidance on economic city profiles

We then collected economic city profiles from the sentences expressing city’s development targets from three parallel documents mentioned above. At the national level, only crucial sentences about regional development of the GPRD as a whole is given by the central government. At the provincial and municipal levels, a collection of economic city profiles in the GPRD was derived from provincial and municipal planning documents. The analytical procedure is presented in Figure 4 and the content of provincial and municipal economic city profiles are shown in the database (The doi of the file in 4TU database is: 10.4121/uuid:ddaabf62-530e-4df2-a0b2-30c75679c7e7).

Figure 4.

Economic city brand identities from the municipal planning documents.

The results of step 2 make it possible to compare the economic city profiles formulated at the municipal level with the guidance on the national and provincial level, and thus to establish to what extent there is intergovernmental congruence. Strictu sensu, higher levels of congruence do not prove causality between national and provincial guidance and municipal adoption, but since national plans tend to precede provincial plans, and provincial plans are drafted before municipal plans, such causality is highly likely. We will also base a number of observations regarding the mechanisms behind multi-level governance in economic city branding in China on these findings.

Step 3: Reflection from symbolic urban projects

As a final step in Section 6, the link with symbolic urban projects at the municipal level is made by relating the economic city profiles chosen by municipal governments with the themes chosen in symbolic urban projects. Urban projects, particularly new towns, are chosen in most of these cities to be flagship projects which can also be the exemplars or pilots for other places.

It was not possible to conduct this third and last step with the same level of analytical rigor and precision as the previous steps. New town projects in each city were collected from lists given in municipal master plans, when a new town was chosen as a targeted development area for the city. We examined how the central ideas in economic city profiles were reflected in the new towns. A field study of four new towns (in Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Foshan and Zhuhai respectively) also provides us their development targets and current status.

The results from step 3 enable us to comprehend to what extent the economic city profiles given in the planning documents at the national, provincial and municipal levels effectively influence development initiatives on the ground and are therefore a preliminary indication whether economic city brands have impact on physical project development.

4. Economic Brand Identities and City Profiles in the GPRD

4.1. The GPRD and Its Eleven Cities

As the biggest mega city region in the world, the GPRD occupies 39,415 km2. It had a population of 66.71 million at the end of 2015 (4.9% of China’s total population). As a key manufacturing base of the world, the GDP growth rate of the GPRD has been over 11% over the last twenty years. This region contributes about a tenth of the nation’s output. It consists of nine cities in the Pearl River Delta (PRD) and two Special Administration Regions (SAR), Hong Kong and Macau.

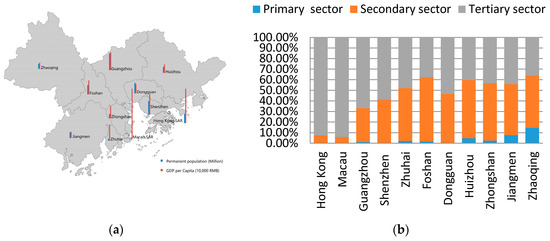

According to Figure 5, Hong Kong and Macau have the highest GDP per capita among these cities. Guangzhou and Shenzhen have the largest population and their GDP contribution in 2014 still lagged behind that of the SARs. Huizhou and Zhaoqing occupy a large territory, but have lower population density, and lag terms of economic development.

Figure 5.

The demographic and economic data of the GPRD cities by the end of 2014. (a) the permanent population and GDP per Capita; (b) the structure of three sectors in GDP for each city.

Moreover, in spite of impressive economic development in the GPRD region as a whole, marked differences in industrial activity exist across the two SARs, Ghuangzhou, Shenzhen and other municipalities. Since the 1980s, manufacturing industries in Hong Kong and Macau have relocated to places with lower land rent and labor costs, most notably the mainland part of the GPRD. Currently, tertiary services represent more than 90% of GDP in Hong Kong and Macau.

As for two Guangzhou and Shenzhen, their tertiary sector has also overtaken other industries in terms of their contribution to GDP. Just like Hong Kong and Macau in the last century, Shenzhen and Guangzhou, along with two economically more advanced cities, Dongguan and Foshan, are actively upgrading their industrial structure. Current manufacturing industries in these cities are relocating to inland China and to poorer countries with less costs [62,63]. The knowledge economy and innovation have become a new form of economic development in the PRD [27,64]. This transition also is made in response to environmental challenges caused by industrial pollution in the last few decades [1]. As for the other cities, the secondary sector, especially manufacturing, still plays a dominant role in their economy. However, they have tended to seize the opportunity and benefit from the industrial relocation from the leading cities to develop their own economies.

4.2. Desired Economic Brand Identity

For each of the eleven GPRD cities, we have taken the desired economic brand identities from their planning documents. The crucial sentences or quotations reflecting economic branding identity are presented in Table A1. From this table, SARs, Guangzhou and Shenzhen have come to adopt sophisticated brand identities, while others have formulated them almost at the level of rather generic policy aspirations. As to Hong Kong and Macau, their identities focus on their regional and global functions, namely “Asia’s World City” and “a world tourism and leisure center”. Besides, it is necessary to mention that Hong Kong’s emergence as a service center for local, regional and international companies and it is now predominantly seen as an international city [65], and the clear identity is also developed in a long term rather than the catch-up cities.

Guangzhou sees itself as a “Provincial capital” and “International Commercial Trade Center”, which can be explained by its key position in the national strategy. Shenzhen describes itself as “Special Economic Zones” and “International City”, expressing its desire to maintain its primary role through developing service and high-tech industries, and maintaining the collaborations with Hong Kong. These desired economic brand identities are not stand-alone, but also show the city’s strategies in the national background. It suggests that cities like Hong Kong, Macau, Guangzhou and Shenzhen attempt to enhance their visibility and reputation through continued and regular use of particular image and discourse [65,66,67].

The majority of the other seven municipalities adopt the term “advanced manufacturing” to reconfirm that manufacturing is still the dominant industry in their economy, but that they strive for an upgrade. Dongguan claims to be “an important information technology R&D center”, whereas Jiangmen profiles as a waterfront city led by “modern manufacturing”. Similarly, Foshan focuses on becoming “an advanced manufacturing base” and also declares its willingness to transform into a “service center for industries”. Huizhou aims to strengthen its economy and focuses on different aspects, such as “petrochemical base”, “electronic information industry” and “light manufacturing” in South China. Alongside initiatives to attract and develop advanced manufacturing industries, other mainland municipalities lack of strong industrial base and have to verge towards reinforcing ecological protection and tourism. For instance, Zhongshan states it is “a liveable entrepreneurial city” and Zhuhai profiles itself as “the coastal tourist city”. Zhaoqing self-portrays as a “a national historical and cultural city” and “tourism city”.

To sum up, the less developed mainland cities don’t have a clear city identity yet, at least they set their policy goals for future development in rather non-descript ways. It seems that they feel the urge to respond to the pressure of ecological modernization and incorporate this need in the way they brand themselves [68]. To further understand how the economic city brands are influenced by national and provincial government, we further focus on their economic city profiles.

4.3. Economic City Profiles at the Municipal Level

We went through the sentences of urban development targets in the municipal 12th and 13th Five Year Plans, Urban Master Plans and Land Use Plans, and made an inventory of all possible brand-related expressions. To ensure the clarity and interpretability of these expressions, we subdivided them according to a generic economic city profile typology based on the main economic sectors [28] and some sustainable city concepts extensively adopted in city development in China [69,70,71,72,73]. Referring to the economic development in the GPRD, we chose agricultural city, advanced manufacturing city and service city to represent the main economic activities in the GPRD cities. Based on the brand-related expressions and their corresponding terms widely used in literature, we also included tourism city (Tourism city is prominent in most cities because many cities make use of their existing natural, or cultural resources to attract tourist, benefiting both their economy and reputation.), sustainable city, smart city, innovation city, eco city, low carbon city, resilient city and liveable city. The ones that could not be classified are included under “others”. Table A2 offers an overview of all economic city profiles and their variations in municipal planning documents. The summary of economic city profiles of the eleven GPRD cities is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

The summary of economic city profiles of the eleven GPRD cities.

Above all, advanced manufacturing and service are the targets of mainland cities in the GPRD, and agriculture city is not mentioned as the targets in any of these cities. This reflects the fact that industrial upgrading and service-oriented activities are the targets of these cities, instead of agriculture or low-end manufacturing.

Specifically, both Hong Kong and Macau emphasize their green aspects (liveable, sustainable), and their main development direction. Hong Kong values innovation and services, while Macau focuses on tourism. This may well reflect the post-materialistic production and consumption pattern of more prosperous urban economies, which are eager for both a high-quality environment and a knowledge economy. Guangzhou and Shenzhen, on the other hand, focus especially on innovation, services and tourism (with Shenzhen also referring to advanced manufacturing) and appear to engage in the shift towards a high-end innovation and service driven economy, which are the main features that distinguish them from their neighbours.

Among the other cities, Dongguan clearly expresses its orientation towards innovation and advanced manufacturing, acknowledging its current industrial position in manufacturing and a wish to upgrade it. Foshan pays some attention to ecological aspects in its profile, but cherishes innovation and smartness as well. Zhuhai and Huizhou lean towards banking on their large green space for the exploitation of tourism and eco-friendly services. The others (Jiangmen, Zhongshan and Zhaoqing) arguably have the least specific economic city profiles, since they mention and embrace many profiles at the same time and therefore seem concerned not to lose out on any opportunities. This can probably be best explained in that they have lower GDP and GDP per capita levels, little advanced industry and the disposal of vast areas of agricultural and open land.

5. Economic City Profiles in an Intergovernmental Context

5.1. City Administrative Hierarchy

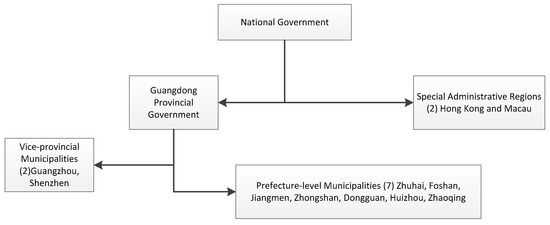

To understand urban development in China, it is necessary to realize that cities operate within an administrative hierarchy, which impacts their administrative power, resource allocation and institutional arrangements [53]. In the GRPD, the eleven cities fall into three different levels, including the special administrative region (SAR), vice-provincial city and prefecture-level city (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Administrative hierarchy of cities in the Greater Pearl River Delta [53].

In administrative terms, the two SARs (Hong Kong and Macau) fall directly under the jurisdiction of the central government, and have separate institutional arrangements due to their colonial past. Compared with the cities in the mainland, they enjoy the highest degree of autonomy in their economic, social and urban planning and development.

Among the nine mainland cities, Guangzhou and Shenzhen are defined as vice-provincial municipalities under the jurisdiction of both the central and the Guangdong provincial governments. Guangzhou is the provincial capital and has a long history of being the center of the Pearl River Delta, and Shenzhen has been a Special Economic Zone since China’s economic reform began four decades ago. Being vice-provincial cities implies that their urban master and land use plans need to be approved both by the provincial and central government (the State Council).

The rest of the seven cities are prefecture-level municipalities, which is lower than vice-provincial cities and SARs in the administrative hierarchy. They enjoy slightly different economic and social administrative authority according to their types. Zhuhai is a Special Economic Zone in China and it is treated as vice-provincial city in certain occasions, and one example is that its urban master and land use plans also subject to approval from the State Council. Foshan, Dongguan, Zhongshan, Huizhou and Jiangmen are regarded as somewhat important by the central government, so they are required to submit their land use plan to the State Council. Compared with them, Zhaoqing is paid the least attention, and its urban master and land use are under the supervision of the province government. In general, cities lower in the administrative hierarchy are subject to less supervision from the central government, but also receive less support.

5.2. Economic City Profiles as Promoted by Higher Level Governments

5.2.1. Guidance by the National Level

In the four national planning documents (see Section 3.1), we conducted a detailed review of the future development of individual cities. To begin with, in the 12th and 13th Five Year Plan, Hong Kong and Macau receive ample attention from the central government, but the nine mainland cities are hardly mentioned. Hong Kong remains important in its functions for the economic development of the mainland [74]. Hong Kong is referred to quite specifically in China’s 12th and 13th Five Year Plans as being a global offshore RMB business hub, as well as an international finance, trade, and shipping center. As seen above, Hong Kong brands itself as Asia’s World City. Compared with Hong Kong, Macau relies more on mainland guidance, probably because of dependence on growing numbers of tourists from the mainland. Macau is encouraged to become a world tourism and leisure center in the national 13th Five Year Plan, in line with the way Macau brands itself. In the National Urban System Plan and the National Land use Plan, Hong Kong and Macau are not mentioned since they have their independent planning system. As for the mainland cities, they are not mentioned in any of these planning documents at the national level, and only the Pearl River Delta is mentioned occasionally as an important metropolitan region.

5.2.2. Guidance by the Provincial Level

At the provincial level (see Section 3.1), the development targets for the nine PRD cities are discussed in detail, but the two SARs are less often mentioned. This is not surprising, given the fact that Hong Kong and Macau do not belong to Guangdong Province. They are mentioned in provincial and regional planning documents as context information, as an advantage for the nine mainland cities if they cooperate with them.

To illustrate how provincial plans affect economic city profiles at the municipal level, we present the number of economic city profiles in municipal and provincial level planning documents, and the overlap between them in Table 2 and Table 3. We collected the economic city profiles from the sentences of urban development targets in these documents. As mentioned above, provincial governments issue their plans first and then municipal governments follow in their wake. Additionally, urban master plans and land use plans of mainland cities must be approved by the provincial government and sometimes even the State Council. Therefore, the overlapping economic city profiles are explained as the municipal governments follow the leads of the provincial government. The complete list of economic city profiles in above provincial documents can be found in economic city profile database.

Table 2.

Consistency of Provincial and Municipal Economic City Profiles in 12th and 13th FYPs.

Table 3.

Consistency of Provincial and Municipal Economic City Profiles in Urban and Land Use Plan.

As for the Five Year Plans, only Shenzhen, Guangzhou and Zhuhai adopt economic city profiles from the Provincial 12th Five Year Plan. However, in the 13th Five Year Plan, Guangdong and Shenzhen’s economic city profiles are less related to provincial documents. Moreover, we can observe that the attention of the provincial Development and Reform Committee centers almost exclusively on Guangzhou and Shenzhen. Table 2 also shows that provincial governments release only one or even no economic city profiles concerning the other mainland cities, and it is not surprising that they have put more efforts in key cities instead of the cities without strategic role at the provincial level.

In the Urban Master Plans, some of the economic city profiles appear to be imported from provincial documents, ranging from 20% to 44%. Huizhou tops among the nine PRD cities by adopting 44% of its economic city profiles from provincial documents, followed by Guangzhou and Shenzhen with both 38%. The impact of the provincial level can be found in all nine cites in their Urban Master plans. Besides, in the Land Use Plans, we find that only 33% of Guangzhou’s and 13% of Shenzhen’s economic city profiles come from provincial documents. Here too, other cities than Guangzhou and Shenzhen do not seem to matter much. As the ‘leading’ cities in the administrative hierarchy and economic development, they are strategic to Guangdong province and even China’s future development.

5.3. Key Observations on Multi-Level Governance

The two Special Administrative Regions Hong Kong and Macau, operating under China’s “One Country, Two Systems” policy, receive more attention from the central government. In contrast, the nine mainland cities are mentioned as one region, and the function and role of individual cities is hardly considered, even for Guangzhou and Shenzhen. Although Hong Kong’s chosen profile is not in contradiction with ideas formulated at the national level, it clearly chooses its own language and flavor. Macau, on the other hand, drafted its first Five Year Plan in 2016, which should be considered a big step in increasing its consistency with the planning system of the mainland.

Guangzhou, Guangdong’s capital city, and Shenzhen, the most successful of all Special Economic Zones, attract by far the most attention from Guangdong province and they also adopt more economic city profiles than all other cities in the PRD. They receive more resources from higher governments to further their economic development, but they are also controlled more by these higher governments and give up part of their autonomy in exchange for this support.

All other cities barely figure in both the national and provincial plans and they seem to be left mostly to their own devices. They are seen as not being of strategic importance. They are comparatively free in their adoption of economic city profiles, but they can also count on quite limited attention and support. When reviewing the economic city profiles, the provincial government’s impact is more to encourage economic development, such as to be economic or innovation center. It is remarkable that the greener images are proposed by these prefecture-level cities by themselves, such as eco, liveable or low carbon city. The question is whether they truly do so for ecological reasons or whether there are other motives. This will be investigated in Section 6.

6. Economic City Brands and Urban Projects

6.1. Project Context and Key Actors

In economic city branding, some symbolic urban projects are selected as promotional tools by governments [38,75,76]. As a key type of urban projects in China, eco city, low carbon city, smart city pilot projects have become paramount in China since 2000 [1,9]. Most of these flagship projects are new towns, characterized by a mix of residential, commercial and industrial clusters in suburban areas [77]. Because of the sheer size of these construction projects, residential buildings, facilities and infrastructures can normally be exploited on such a scale that new towns provide potential markets for green technologies, such as green buildings, waste recycling systems and water purification plants [78,79]. Besides, industrial parks planned in these new towns can be used as demonstration zones for industrial upgrading [80].

The actors involved in new town projects are various, but the key players tend to be different levels of government, project developers (often state-owned), while banks, architects, designers, and non-governmental organizations operate in the background [49,81]. Most new town projects are led by management organizations established by either municipal or district governments with the involvement of developers. The economic city profiles are established by municipal governments, but the complexity and uncertainty in the local context of these symbolic projects requires strong involvement and organizational capacity of district governments or even bodies operating at the level of neighborhoods [71]. Some very prestigious new town projects are supported by ministries at the national or provincial level which then also contribute funds, support and knowledge and encourage the consultation of foreign experts with specific technical knowledge [9].

6.2. Urban Projects at the Municipal Level

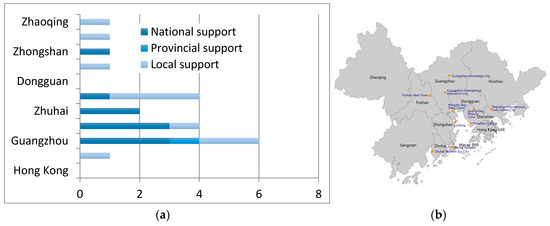

We collected the set of new town projects in the GPRD from the various Urban Master Plans (from 2010 to 2020). Since the Urban Master Plan guides urban development in cities for the next decade or so, these new towns are in the planning or constructing phase. To examine how these new town projects aim to deliver on the promises made in the economic city profiles, we made an inventory of pilot projects associated with municipal economic city profiles, which is shown in Figure 7. Their supporting programs are presented in Table A3.

Figure 7.

(a) the Number of New towns in each city in the GPRD; (b) the Locations of National support ones

We found no new town projects in Hong Kong’s Strategic Plan 2030. Due to its high urbanization level, urban transformation projects are preferred over urban expansion. In Macau’s Conceptual Plan, Macau New District stands out in its ambition to help the city become a “World Tourist and Leisure Center”. Guangzhou and Shenzhen have more new towns planned than the rest of the cities, and more than half of their new towns receive support from the national government as demonstration areas. As for the prefecture-level cities, numbers of new towns launched per city vary from 0 to 3, with most have 1. Of those, only one in Foshan, one in Zhuhai and one in Zhongshan receive some form of national support.

6.3. Key Observations on the Local Project Context

National ministries attempt to promote certain economic city profiles not just through planning guidance, but also through supporting symbolic urban projects. Although the province only supports one new town project in Guangzhou, most projects are also allocated financial or other support by the central government. In that sense, the interventions from the central and provincial governments are not restricted to the dissemination of concepts alone; they can also selectively offer funding, expertise and political help. Their selectiveness becomes apparent when we examine which of the eleven GPRD cities benefit from this support and how this affects the economic city profile-related terminology in their project documentation.

Hong Kong and Macau as Special Administrative Regions are not eligible for national support. Hong Kong does not have any urban extension projects, while Macau has one. That one is fully in line with national and municipal desired brand identities and city profiles. National subsidies do not reach Hong Kong and Macau’s local projects. Guangzhou and Shenzhen are both quite active in urban extension and most of their new towns receive support from primarily the national government. In our interviews with staff working in these new towns, we found that the targets of their new towns are also largely consistent with their economic city profiles, although it is hard to identify to what extent actual project delivery honors the expectations evoked by these economic city profiles is “truly realized”.

The other seven cities essentially draft and organize their new town projects by themselves, only incidentally receiving support from high above. In Foshan and Zhuhai, their actual goals are largely the same: building new residential areas and industrial parks to attract investment and talented workforce in fierce competition with other cities, generate GDP growth through real estate development and enhance the flow of municipal revenue. This also holds for other cities: in their promotion documents they tend to adopt similar city profiles as the SARs and vice-provincial cities. However, because of their limited financial and organizational capabilities, their application of economic city profiles appears to be more ad hoc and untargeted. In fact, if anything, their focus on “green” rather than ‘industrial’ aspects of new towns appears to be stronger than in Guangzhou and Shenzhen. This can be explained by the fact their new towns contain relatively more residential property development instead of science and technology parks. Additionally, although they boast to develop service industries, these are limited to real estate development, retail and wholesale and tourism, rather than finance, logistics or other professional services. While the more prosperous cities have negotiation power vis-à-vis developers to push through their own strategic targets and develop more in line with their city profiles, the less developed cities in the GPRD depend heavily on investments in infrastructure from developers and their negotiation power is far weaker. The greenness therefore rather reflects the wish to lure investors and future inhabitants to spend resources in their new towns than anything else.

7. Conclusions

Economic city branding is actively used by municipal governments in the Greater Pearl River Delta as a policy instrument to set targets for their economic development. However, it operates as a double-edged sword. Its goal is to promote urban greening in all its different facets on existing urban land, but it also aims to enhance local attractiveness to investors, inhabitants and (re)locating corporations outside it. The former may make existing urban assets more environmentally friendly, the latter leads to a further expansion of urban territory extremely likely to generate more emissions and to sacrifice growing amounts of unbuilt land.

In this contribution, we have mapped both the desired brand identities for all eleven cities in the GPRD and identified a generic typology of economic city profiles which these cities use. It appears that they all realize the importance of giving themselves a brand identity, but the cities advanced in economic development and high in the administrative hierarchy, such as Hong Kong, Macau, Guangzhou and Shenzhen have adopted more sophisticated brand identities than the other ones.

Among the economic city profiles, we found that to be a tourist city, advanced manufacturing city and/or service city reflects the goals for most GPRD cities. Here the wealthier SARs turned out to have more post-materialist city profiles focusing on liveability. The economically upcoming but more materialist cities Guangzhou and Shenzhen combined a service orientation with tourism and innovation, while the least wealthy ones opted for either primarily advanced manufacturing with other features (Dongguan, Jiangmen), or strong tendency towards tourism (Foshan, Zhongshan, Zhaoqing, Huizhou), or a less distinct mixture of various city profiles (Huizhou and Zhuhai) to ensure they would not lose out on any developmental opportunities.

The economic city profile choices made at the municipal level in China cannot be seen as a stand-alone activity, but occur in a multi-level governance context. The various national and provincial plans have impact on them. The national and provincial plan documents set the tone for development in general. The ecological modernization themes, such as ecological preservation, low carbon development and smartness, are mentioned in both national and provincial documents. As for individual cities, the national plan documents mention Hong Kong and Macau and their ideas on how these SARs should promote themselves. The national plans leave the individual mainland cities in the Pearl River Delta largely undiscussed. At the provincial level exactly the opposite is the case: Hong Kong and Macau are the context, while the focus is on the eleven cities on the mainland. The attention is unevenly divided, however: ‘leading’ cities, Guangzhou and Shenzhen are the province’s main concern and the others receive far less attention. This extra attention and support is helpful because it places them at the apex of the PRD’s future development, but this comes with strings attached: they are required to follow and adopt the urban concepts and targets as elements in their city profiles. The less privileged ones, the prefecture-level cities, tend to enjoy a lot of autonomy in their city profile choices, but also lack most national and provincial support and guidance in going through their ecological modernization pathways. Some of them make relatively clear and recognizable choices, such as advanced manufacturing or tourism city, while others seem to throw in a bit of all concepts hoping to combine the attraction of industrial corporations while still banking on an ecological and tourist-friendly image.

At the level of symbolic urban projects, we find how economic city profiles chosen at the municipal level, but in a multi-level governance context, trickle down in the promotion documents of new town projects. Here, we see largely the same patterns back as above: Hong Kong is mostly on a post-materialist path of development and does not engage in new town projects, Macau has one and brands it fully in line with Chinese national wishes, Guangzhou and Shenzhen develop many new town projects and many of them are actively supported by the national government and their branding is well aligned with national and provincial wishes, while the other cities enact their new town projects mostly by themselves and use their freedom to conveniently replicate city profiles from others they think fit market wishes well. But since these cities depend for their urban revenue and GDP growth more on real estate investment than on anything else, their position vis-à-vis developers and (re)locating companies on the negotiation table is normally weak. Consequently, guarantees that their economic city profiles will indeed lead to real substance of ecological modernization are extremely flimsy. Selecting the right corporations and inhabitants for their new towns and keeping polluting industries and space-wasting residential areas at bay when dependency on project developers is so intense is a difficult and painful process at best.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/9/4/496/s1, Table S1: Economic city profiles of 11 cities in GPRD in municipal 12th Five Year Plan, Table S2: Economic city profiles of nine cities in GPRD in municipal 13th Five Year Plan, Table S3: Economic city profile number and types of the GPRD cities in municipal Urban Master Plan, Table S4: Economic city profiles of nine cities in GPRD in municipal Land Use Plan, Table S5: Economic city profiles of nine cities in Provincial Urban Master Plan, Table S6: Economic city profiles of nine cities in Provincial 12th Five Year Plan, Table S7: Economic city profiles of nine cities in Provincial 13th Five Year Plan, Table S8: Economic city profiles of nine cities in Provincial Land Use Plan (2006–2020).

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to two anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback and thank the Urban Knowledge Network Asia (UKNA) project and the Delft Initiative for Mobility & Infrastructures (DIMI) for their financial support. The authors are also grateful for the comments provided during the INOGOV workshop in Amsterdam, 2016 on this manuscript. Finally, the authors express their gratitude to Yanchun Wei for help with the figures and Xuanzi Wei for her information about planning institutions.

Author Contributions

First author Haiyan Lu is the key author and did most of the writing in this contribution. Second author Martin de Jong verified and solidified the argument, edited the text and drafted the conclusions. Third author Yawei Chen contributed to the insights on economic city branding in Hong Kong and Macau, provided insight into the desired brand identities from planning documents for the GPRD cities, and verified the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Economic brand identities in the GPRD cities.

Table A1.

Economic brand identities in the GPRD cities.

| City | Economic Brand Identity (Key Elements Are Bold-Faced) |

|---|---|

| Hong Kong | The long-term vision for Hong Kong to strengthen its position as Asia’s world city … “Asia’s world city” is not only about economic growth and competitiveness, but ensuring we have a city that is proud for being Asia’s exemplary city in achieving true sustainable development (HK2030). |

| Macau | With gambling and tourism as its main industries, Macau regards delicacy and pleasance as its development targets, continued prosperity as its goals, and openness and inclusiveness as its characteristic. Macau is a tourism and liveable city, sustainable development city, world vibrant city (Macau Conceptual Plan 2007). |

| Guangzhou | Guangzhou is one of National Center Cities, provincial capital, International Commercial Trade center, External Exchange Center, Comprehensive Transportation Hub, and a an International Shipping Center in South China (UMP). It builds into a National Innovation city (12th FYP). |

| Shenzhen | Shenzhen is the Special Economic Zones, National Economic Center and an International City in China. Shenzhen is the service base to support Hong Kong’s prosperity and stability. Under the framework of “one country two systems”, Shenzhen aims to be an international financial, trade and shipping center with the development of Hong Kong. Shenzhen is also the national high-tech industrial base and cultural industry base (UMP). |

| Foshan | Foshan will be built into an advanced manufacturing base, a service centre for industries, a Lingnan Cultural city, a beautiful home with happiness. |

| Dongguan | Dongguan is the central city in the PRD. It is an important information technology R&D, an industrial base in China, as well as a modern city with beautiful environment. |

| Jiangmen | Jiangmen is one of the central city and portal cities in west of PRD… It is a waterfront city led by modern manufacturing, trade logistics and cultural tourism industries (Urban Master Plan). Jiangmen strives to be Livable Eco Model city (12th FYP). |

| Zhongshan | Zhongshan is the regional central city in the West Bank of PRD, a livable entrepreneurial city with an attractive ecological and investment environment for startups in Guangdong Province, a tourist city as the hometown of Sun Yat-sen (UMP). |

| Huizhou | Huizhou is one of the central cities in the PRD. Huizhou will be a petrochemical base, as well as an important cluster of electronic information industry and light manufacturing in South China, Huizhou will be a scenic coastal city in Guangdong, a historical and cultural city, as well as an important area of leisure base (UMP). |

| Zhaoqing | Zhaoqing is the local central city in Guangdong Province, a national historical and cultural city and tourist city (UMP). |

| Zhuhai | Zhuhai is a national Special Economic Zone, the central city in the West Bank of the PRD and the coastal tourist city…Zhuhai aims to be a modern service center in the West Bank of PRD. Zhuhai strives to a leading heavy strategic manufacturing base. Zhuhai targets to be a high-tech industry-oriented research and education (UMP). |

Table A2.

Economic city profiles and their variations in municipal planning documents.

Table A2.

Economic city profiles and their variations in municipal planning documents.

| Economic City Profiles | Their Varieties Found in Planning Documents |

|---|---|

| Agriculture | none |

| Advanced manufacturing city | National High-tech Industrial Base and Cultural Industry Base, High-tech Industrial Development and Production Base in South China, First tier manufacturing city in China, Model city of industrial upgrading |

| Service city | Service Centre for Industry, International Commercial Centre, Regional Financial Centre, Regional Business Centre, Modern Service Centre in the West Bank of PRD, Logistics Centre |

| Tourism city | National Historical and Cultural City, Famous International Tourist City, Regional Tourist Destination, Cultural City , International Business Travel resort; Coastal Tourist City |

| Sustainable city | City of pluralistic cultural heritage and sustainable development, Sustainable development, Sustainable Development Capital |

| Smart city | Smart Foshan |

| Eco city | Sustainable Development Capital, Model city for ecological restoration, Model City of Coordinated Development with Economic, Social, and Environmental Resources; National Forest City |

| Low carbon city | Demonstration area for national low-carbon eco development |

| Resilient city | Sponge city |

| Liveable city | Liveable high-density city, Travel liveable City, Liveable Eco City with Overseas Chinese Characteristics, the ideal liveable city in the PRD. International Liveable City |

| Innovation city | National Innovation Centre City, National Innovation Demonstration Zone, Pioneer in innovation-driven city, Important innovation and technology center, Modern Industrial City for Start-ups, National Innovation-type SEZ |

| others | A Perfect City in Guangdong Province, International Metropolis, National Center City, City for People’s livelihood and Happiness, Model City of Socialism with Chinese characteristics, Modern International Advanced City, Beautiful and Wealthy Home, Harmonious Zhongshan Harmonious Huizhou, Active Zhaoqing |

Table A3.

National or Provincial Support Programs of GPRD New Towns.

Table A3.

National or Provincial Support Programs of GPRD New Towns.

| City (New Town Number) | New Town Name | Support Program |

|---|---|---|

| Guangzhou (3) | Guangzhou Knowledge City | Pilot for National Smart City (Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development, or MOHURD) |

| Guangzhou International Innovation City | National Modern Service Industry International Innovation Park, approved by National Science Ministry | |

| Mingzhu Bay in Coastal City in Nansha | National Free Trade Zone; Demonstration area for cooperation between Guangdong, Hong Kong and Macau | |

| Shenzhen (3) | Qianhai | National Free Trade Zone; Modern Service Industry Pilot (Ministry of Finance and Commerce) |

| Shenzhen International Low Carbon City | Pilot National Low Carbon City (National Development and Reform Committee) | |

| Guangming Phoenix Town | Pilot National Sponge City (Ministry of Finance, MOHURD, Ministry of Water Resources) | |

| Foshan (1) | Foshan New Town | Pilot China-EU cooperation urbanization demonstration (MOHURD and EU) |

| Zhuhai (2) | Hengqin | National Free Trade Zone; pilot for National Low Carbon City (National Development and Reform Committee) |

| Zhuhai Western Eco City | Pilot China-EU cooperation urbanization demonstration (MOHURD and EU) | |

| Zhongshan (1) | Cuiheng New District | pilot for National Smart City (MOHURD) |

References

- Liu, H.; Zhou, G.; Wennersten, R.; Frostell, B. Analysis of sustainable urban development approaches in China. Habitat Int. 2014, 41, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. Environmental pollution emissions, regional productivity growth and ecological economic development in China. China Econ. Rev. 2015, 35, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Zhang, L.; Mol, A.P.J.; Lu, Y.; Liu, J. Revising China’s Environmental Law. Science 2013, 341, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, Y.; Sarkis, J.; Ulgiati, S. Sustainability, wellbeing, and the circular economy in China and worldwide. Science 2016, 120, 76–79. [Google Scholar]

- Bayulken, B.; Huisingh, D. A literature review of historical trends and emerging theoretical approaches for developing sustainable cities (part 1). J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 109, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mol, A.P.J. Ecological Modernization: Industrial Transformation and Environmental Reform; Edward Elgar Publishing, Inc.: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Howlett, M. Government Communication as a Policy Tool: A Framework for Analysis. Can. Polit. Sci. Rev. 2009, 3, 23–37. [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Berg, L.; Braun, E. Urban Competitiveness, Marketing and the Need for Organising Capacity. Urban Stud. 1999, 36, 987–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, M.; Yu, C.; Joss, S.; Wennersten, R.; Yu, L.; Zhang, X.; Ma, X. Eco city development in China: addressing the policy implementation challenge. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 134, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshuis, J.; Edwards, A. Branding the City: The Democratic Legitimacy of a New Mode of Governance. Urban Stud. 2012, 50, 1066–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucarelli, A.; Giovanardi, M. The political nature of brand governance: A discourse analysis approach to a regional brand building process. J. Public Aff. 2016, 16, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, E. City Marketing—Towards an Integrated Approach; Erasmus University Rotterdam, Erasmus Research Institute of Management: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, E. Putting city branding into practice. J. Brand Manag. 2012, 19, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avraham, E.; Ketter, E. Media Strategies for Marketing Places in Crisis: Improving the Image of Cities, Countries and Tourist DESTINATIONS; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, B. Destination Branding for Small Cities: The Essentials for Successful Place; Creative Leap Books: Portland, OR, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Paddison, R. Editorial: Urban Studies at 50. Urban Stud. 2012, 50, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavaratzis, M. City Marketing: The Past, the Present and Some Unresolved Issues. Geogr. Compass 2007, 1, 695–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anttiroiko, A.-V. The political Economy of City Branding; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Anholt, S. What is Competitive Identity? In Competitive Identity: The New Brand Management for Nations, Cities and Regions; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2007; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Anhott, S. Places: Identity, Image and Reputation; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dinnie, K. City branding: Theory and cases. Place Brand. Public Dipl. 2011, 7, 218–222. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, P.O.; Bjorner, E. Branding Chinese Mega-Cities: Policies, Practices and Positioning; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Govers, R.; Go, F. Place Branding—Glocal, Physical and Virtual Identities Constructed, Imagined or Experienced; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Moilanen, T.; Rainisto, S. How to Brand Nations, Cities and Destinations: A Planning Book for Place Branding; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Zhao, S.X. City branding and the Olympic effect: A case study of Beijing. Cities 2009, 26, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judith, K. The State and the Arts: Articulating Power and Subversion; Berghahn Books: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Björner, E. Imagineering Chinese mega-cities in the age of globalization. In Branding Chinese Mega-Cities: Policies, Practices and Positioning; Berg, P.O., Björner, E., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2006; pp. 106–120. [Google Scholar]

- Anttiroiko, A. City brands in the mediatised world. Scand. J. Public Adm. 2016, 20, 97–118. [Google Scholar]

- Merrilees, B.; Miller, D.; Herington, C. Multiple stakeholders and multiple city brand meanings. Eur. J. Mark. 2012, 46, 1032–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henninger, C.E.; Foster, C.; Alevizou, P.J.; Frohlich, C. Stakeholder engagement in the city branding process. Place Brand. Public Dipl. 2016, 12, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graby, F. Product-Country Images: Impact and Role in International Marketing. In Product-Country Images: Impact and Role in International Marketing; Papadopoulos, N.G., Heslop, L., Eds.; The Haworth Press: Binghamton, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Askegaard, S.; Ger, G. Product-country images: Towards a contextualized approach. In European Advances in Consumer Research Volume 3; Association for Consumer Research: Duluth, MN, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Aaker, D. Measuring brand equity across products and markets. Calif. Manage. Rev. 1996, 38, 102–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trueman, M.; Klemm, M.; Giroud, A. Can a city communicate? Bradford as a corporate brand. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2004, 9, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavaratzis, M. City Branding Communication Model. Eur. Inst. Brand Manag. 2012, 12, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, S.; Bai, C. The Discussion on the Conceptual Framework of City Brand from the Perspective of Customer. Urban Probl. 2008, 5, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Ashworth, G.; Kavaratzis, M. Beyond the logo: Brand management for cities. J. Brand Manag. 2009, 16, 520–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prilenska, V. City Branding as a Tool for Urban Regeneration: Towards a Theoretical Framework. Archit. Urban Plan. 2012, 6, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulsrud, N.; Gooding, S.; van den Bosch, C. Green space branding in Denmark in an era of neoliberal governance. Urban For. Urban 2013, 12, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquinelli, C. Competition, cooperation and co-opetition: Unfolding the process of inter-territorial branding. Urban Res. Pract. 2012, 6, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anttiroiko, A.-V. City Branding as a Response to Global Intercity Competition. Growth Change 2015, 46, 233–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucarelli, A.; Berg, P.O. City branding: A state-of-the-art review of the research domain. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2011, 4, 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F. Place promotion in Shanghai, PRC. Cities 2000, 17, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bache, I.; Flinders, M. Themes and Issues in Multi-level Governance. In Multi-level Governance; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Guy Peters, B.; Pierre, J. Developments in intergovernmental relations: Towards multi-level governance. Policy Polit. 2001, 29, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooghe, L.; Marks, G. Unraveling the Central State, But How? Types of Multi-Level Governance. Am. Polit. Sci. Ser. 2003, 97, 233–243. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, F. Planning for Growth: Urban and Regional Planning in China; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, F. China’s Changing Urban Governance in the Transition Towards a More Market-oriented Economy. Urban Stud. 2002, 39, 1071–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, B.; Lang, G. A Tale of Two Eco-Cities: Experimentation under Hierarchy in Shanghai and Tianjin. Urban Policy Res. 2015, 33, 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.H. A Comparative Study on the Development Model of China’s City Brands (in Chinese). Commer. Times 2005, 22, 4–5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.H. Qingdao Brand from a Perspective of Economy. Master’s Thesis, Ocean University of China, Qingdao, China, 1 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y. Planning Institutions. In International Encyclopedia of Housing and Home; Elsevier: San Diego, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 196–201. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, H. The Administrative Hierarchy and Growth of Urban Scale in China. Chin. J. Urban Environ. Stud. 2015, 3, 1550001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- City Planning Act. Available online: http://www.china.com.cn/zhuanti2005/txt/2003–07/22/content_5370682.htm (accessed on 21 March 2017).

- Development Bureau Planning Department Hong Kong 2030 Planning Vision and Strategy Final Report. Available online: http://www.epd.gov.hk/epd/SEA/eng/file/FinalSEAReport.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2017).

- Macau Conceptual Plan. Available online: http://www.hkip.org.hk/admin/ewebeditor3.7/uploadfile/Macau Concept Plan 2008.pdf (accessed on 22 Feburary 2017).

- Macau Five Year Development Plan (2016–2020). Available online: http://www.cccmtl.gov.mo/files/projecto_plan_cn.pdf (accessed on 20 Febuary 2017).

- Planning Department Outline Zoning Plans-Hong Kong Plannning Areas. Available online: http://www.pland.gov.hk/pland_en/info_serv/tp_plan/stat_plan/hkozp.html (accessed on 22 March 2017).

- City Executive of Hong Kong Hong Kong Policy Address 2011. Available online: http://www.policyaddress.gov.hk/11-12/ (accessed on 22 March 2017).

- City Executive of Hong Kong Policy Address 2016. Available online: http://www.policyaddress.gov.hk/2016/eng/ (accessed on 22 March 2017).

- City Executive of Macau Policy Address for the Fiscal Year 2011 of the Macao Special Administrative Region (MSAR) of the People’s Republic of China. Available online: http://www.policyaddress.gov.mo/policy/download/en2011_policy.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2017).

- Yang, C. Restructuring the export-oriented industrialization in the Pearl River Delta, China: Institutional evolution and emerging tension. Appl. Geogr. 2012, 32, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Kloosterman, R.C. Connecting the “Workshop of the World”: Intra- and Extra-Service Networks of the Pearl River Delta City-Region. Reg. Stud. 2016, 50, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Wei, Y.D. Domesticating Globalisation, New Economic Spaces and Regional Polaristion in Guangdong Province, China. Tijdschr. voor Econ. en Soc. Geogr. 2007, 98, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bie, J.; De Jong, M.; Derudder, B. Greater Pearl River Delta: Historical Evolution towards a Global City-Region. J. Urban Technol. 2015, 732, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Yeh, A.G.O. City repositioning and competitiveness building in regional development: New development strategies in Guangzhou, China. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2005, 29, 283–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, K.Y.; Lee, K.M.; Poon, C. Challenges to the city imagineering in Hong Kong: Place making and struggle between globalization and local concerns. Int. J. Interdiscip. Soc. Community Stud. 2013, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, M.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, M.; Lu, H. Urban transformation and city branding in the Greater Pearl River Delta. In Sustainable Urbanization in Asia; Caprotti, F., Yu, L., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, in press.

- De Jong, M.; Joss, S.; Schraven, D.; Zhan, C.; Weijnen, M. Sustainable-Smart-Resilient-Low Carbon-Eco-Knowledge Cities. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 108, 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- Khanna, N.; Fridley, D.; Hong, L. China’s pilot low-carbon city initiative: A comparative assessment of national goals and local plans. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2014, 12, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, K. China’s low-carbon city initiatives: The implementation gap and the limits of the target responsibility system. Habitat Int. 2014, 42, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Doberstein, B.; Fujita, T. Implementing China’s circular economy concept at the regional level: A review of progress in Dalian, China. Waste Manag. 2009, 29, 996–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taddeo, R.; Simboli, A.; Ioppolo, G.; Morgante, A. Industrial Symbiosis, Networking and Innovation: The Potential Role of Innovation Poles. Sustainability 2017, 9, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, H.M.; Lu, Q.W. Culture and planning: How can Hong Kong’s urban planning system facilitate comprehensive culturaldevelopment? Master’s Thesis, Hong Kong University, Hong Kong, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzen, M.; Frederiksen, L. Why do cultural industries cluster? Localization, urbanization, products and projects. In Creative Cities, Cultural Clusters and Local Economic Development; Edward Elgar Publishing, Inc.: Cheltenham, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.; von Krogh Strand, I. Oslo’s new Opera House: Cultural flagship, regeneration tool or destination icon? Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2011, 18, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsing, Y.-T. The Great Urban Transformation: Politics of Land and Property in China; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Caprotti, F. Critical research on eco-cities? A walk through the Sino-Singapore Tianjin Eco-City, China. Cities 2014, 36, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hult, A. Swedish Production of Sustainable Urban Imaginaries in China. J. Urban Technol. 2013, 20, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Dijkema, G.P.J.; de Jong, M.; Shi, H. From an eco-industrial park towards an eco-city: A case study in Suzhou, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 102, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joss, S.; Molella, A. The Eco-City as Urban Technology: Perspectives on Caofeidian International Eco-City (China). J. Urban Technol. 2013, 20, 115–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).