Abstract

Building on a case study of three animation companies in the Chinese cultural and creative industry, this study aims to understand how profit model innovation is promoted. Due to the rapidly changing environments and resource scarcity, cultural and creative companies need to select the appropriate profit model according to their own key resources. The study uncovers two critical factors that promote profit model innovation in animation projects: the quantity of consumers and their consumption intention. According to these two dimensions, the authors’ analysis shows profit model innovation in animation projects can be divided into Fans mode, Popular mode, Placement mode, and Failure mode, respectively. This study provides an empirical basis for advocating profit model innovation and discusses the resource requirements of Fan mode, Popular model, and Placement mode in China’s cultural and creative industry. The authors’ research also has managerial implications that might help firms promote profit model innovation. Finally, learning and promoting the profit model of China’s animation industry in the Northeast Asia area will be conducive to Northeast Asia’s cooperation and sustainable development.

1. Introduction

The development of cultural and creative industries in Northeast Asia plays an important role in promoting the sustainable development of the entire region [1]. China is typically an important part of Northeast Asia. Since 2002, the Chinese government has issued a series of policies to promote the development of the cultural and creative industry, especially the animation industry [2,3]. The industrial chain of the animation industry has been taking shape gradually since then. Under such market opportunities and preferential policies, more and more companies have begun to get involved in the animation industry. Through summarizing and drawing on some good models of China’s animation industry, and promoting it in Northeast Asia, it can promote regional cooperation and sustainable development. Therefore, this article makes an in-depth study of the profit model of animation projects in China’s cultural and creative industries.

According to the experience of the United States of America (U.S.A.) and Japan, the market value of the animation industry is remarkably large. The growing number and variety of types of animation companies show the booming trend in China. Since Chinese culture is low-cost, low-energy, and high value-added, which is the foundation of the creative idea of animation, China’s animation industry captures the world’s attention [4]. The Chinese market has great potential for development. It is conducive to make better use of the Chinese market in Northeast Asia to achieve the management and sustainable development of the cultural and creative industries in the entire region, through the exploration of the profit model of China’s animation industry.

When compared to Japan and Korea, the domestic consumer market of the animation industry in China is not mature enough, and the animation companies are late-comers [5,6]. Some successful animation companies illustrate a variety of modes in communication channels, profit models, and other aspects. It is an important issue to find out the general factor of the profit model in these existing successful cases, which will help to promote the balanced development of cultural and creative industries in Northeast Asia. The successful application of the animation industry profit model will also be conducive to the economic development of Northeast Asia to promote the sustainable development of the entire region.

Therefore, this paper tries to analyze the communication channel and profit model of three successful animation companies, and summarizes successful profit models in the animation industry. The research could provide implications for practices of Chinese animation companies. Consequently, summarizing the profit model in animation industry has great meaning.

2. Literature Review

2.1. An Overview of the Cultural and Creative Industry

Many scholars focus on the development of the cultural and creative industry. Zeng et al. [3] compare the efficiency differences in different areas of the world and hold the opinion that the cultural industry in China is relatively inefficient [4]. Liu and Chiu [7] emphasize the core position of the cultural and creative industry in cities, and explain how they enhance a city’s competitiveness. Bai [8] introduces four essential factors for studying the cultural and creative industries in three different countries, including economic environment, creativity, communication, and technology.

When considering that the animation industry is an important part of the cultural and creative industry, scholars try to find the implications for the Chinese animation industry. Zhou and He [9] analyze the basic documents for the development of the Chinese animation industry, and provide the basis for further research. Xu and Schirato [5] analyze the impact of the Chinese animation industry from three aspects: politics, economy, and culture. Based on the research, Liu [10] explores animation production, communication media, and other processes in the Chinese animation industrial chain, and summarizes three development models, which are essentially driven by TV, driven by derivative products, and pushed by animation technology. Dai [11] presents that in the Chinese animation industry, the animation companies should play the dominant role in integrating resources, and extend the industrial chain both vertically and horizontally.

2.2. Business Model in the Cultural and Creative Industry

Scholars discuss different models of the cultural and creative industry, most of them focusing on the business model. Horng [12] presents a Culture Creative-Based Value Chain, based on where three different business models in Taiwan are compared. Dai et al. [13] introduce the business model, profit model and value chain in Shanghai. Yi [14] focuses on the cultural industry in Shenzhen and summarizes several cross-development models of the industry. Benghozi and Lyubareva [15] consider innovation as a kind of competitive advantage for the cultural industry and introduce three kinds of online business models. Vassiliki [16] point out that new business models in creative industries can be used in certain areas, which is an opportunity for European Union (E.U.) counties. Lerro and Schiuma [17] introduce the impact of European business models on the value creation mechanisms.

Meanwhile, Zhao [18] analyzes the animation industry in Europe, and presents three models: the French government-led model, the British government coordination patterns, and the German model based on local coordination. Chen [19] introduces the stages of Japanese animation development, the relationship between Japanese animation and the comics publishing industry, and the growth mechanism of the animation industry. Zhang et al. [20] focus on the Japanese animation industry and present two developing models, including cartoon creation-oriented and commercial operation-oriented. Cui et al. [21] compare the Chinese animation industry with the Korean animation industry and try to find countermeasures to enhance the competitiveness of the Chinese animation industry.

2.3. Operation Model in the Cultural and Creative Industry

Some other scholars mainly investigate the operation model of the cultural and creative industry. Dalecka and Szudra [22], for instance, analyze the operation of the cultural and creative industry and how it plays an important role in the development of cities. The article presents that the basic factors of the industry are creativity, skills, and talent. Magdalena [23] analyzes family business operation and discusses their value system. Chen [24] presents a decision-making model to evaluate the performance of the cultural industry. Strazdas and Cerneviciute [25] point out that some small firms are faced with complex markets, so creativity is essential in the operation process.

Scholars also focus on the industrial chain structure of the cultural and creative industry. Cai [26], for example, analyzes the diversified industrial chain structure and the profit-oriented product development model. Wang [27] uses Disney and DreamWorks as examples to analyze the animation industrial chain of the U.S.A., and presents a customer-value, creation-based mechanism. Wang et al. [28] list some problems of cultural and creative industries in China and put forward the management mode by analyzing the value chain. Both Wang et al. [29] and Madudova and Emilia [30] analyze the factors that affect the value chain model in the creative industry.

Therefore, few researchers put their emphasis on the profit model of the animation industry. The existing relevant literature is more descriptive research than in-depth theoretical analysis. The models in the existing literature are incomplete. Thus, an in-depth research, which is based on case studies, is needed to analyze the Chinese animation industry.

2.4. Profit Model in the Animation Industry

Based on the survey, Yu and Song [31] analyze the profit model of Chinese animation companies. Their research divides the profit model into six categories: original animation-driven, brand licensing, channel-driven, derivatives-driven, new media-driven, and the integration of OEM (Original Equipment Manufacturer) original design. Yuan [32] clusters the animated film industry chain into three types, and explores the profit model of animated film companies. His research finds three profit models, including profit from box office, profit from TV, video products and other new media distribution, and profit from stage opera based on animation and toys. Li [33] compares the profit models of the animation industry in the United States, Japan, and South Korea, and summarizes several profit-making models of the current network animation in China. Fu and Tang [4] suggest using online teaching and animation methods to develop animation education. Choi [34] analyzes the Korean animation industry and points out that the industry is the most profitable business model in modern society, which also promotes the development of related industries. Gu [6] compares the development experiences of Korea and China, and analyzes the problems of the Chinese animation industry. Ye and Zheng [35] present that the Chinese animation industry should optimize the industry chain, model, and rules and regulations. These researchers get some interesting findings, but most of them are only descriptive summaries without in-depth analysis of the mechanism behind the profit models of the companies.

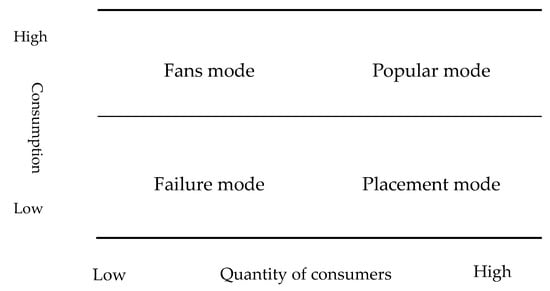

The product in the animation industry is a kind of cultural product for consumption. The fundamental profit comes from the consumer. Therefore, it is concluded that fundamental profit is decided by the quantity of consumers and their consumption intention. Based on this, the following chart is produced (Figure 1). The profit model innovation chart in the animation industry is divided into four types of scenarios, Fan mode, Popular mode, Placement mode, and Failure mode, respectively.

Figure 1.

Profit model innovation in animation industry in Chinese Cultural and Creative Industry.

2.4.1. Fan Mode

The first part of the cycle is the Fan mode, which has a high consumption intention but a low quantity of consumers. This situation has loyal consumers who would like to buy the animation products even at a high price. The best strategy in this scenario is to cultivate a repeated direct purchase habit of the consumer for a variety of forms of animation and derivative products to mine customer experience value and train and expand the fan community.

2.4.2. Placement Mode

The Placement mode cycle deals with low consumption intention and high quantity of consumers. Although there are many consumers, they do not like to purchase the animation product directly and substantially. This scenario requires enhancing the consumer’s attention and letting them realize the value of the animation product. To specify, the situation needs the support from advertisements to increase the ratings and hits of animation products.

2.4.3. Popular Mode

The Popular mode is the scenario where there is the optimum situation of a high quantity of consumers and high consumption intention. This method is the optimal condition, since it can make a profit from a small number of loyal consumers and a large quantity of non-loyal consumers, simultaneously.

2.4.4. Failure Mode

The Failure mode is the situation where the quantity of consumers is low, and the consumption intention is low. This is the worst situation. This situation occurs when the animation products are not delivering profits making it best to liquidate. Therefore, this situation is not discussed in this paper.

The following profit model innovation chart (Figure 1) for the animation industry can help an animation project to increase and monitor its market share and growth. All animation projects, whether big or small, should have a specific type of profit model on which to base their products, in order to track the market and what consumers want. Some animation projects in China will be employed to illustrate how to innovate in the profit model.

3. Methodology

Given the relatively new and unexplored nature of the phenomenon, this study adopted an exploratory research strategy [36,37]. Qualitative research is particularly useful for exploring implicit assumptions and examining new relationships, abstract concepts, and operational definitions [38,39]. The objective was to conduct an analysis of the profit model in the Chinese animation industry that would help to build theory and develop constructs that would facilitate future hypothesis testing [36].

The initial research questions provided guidance for this study, and helped to identify meaningful and relevant activities [37]. This paper adopted the following criteria for selecting the cases. First, the selected cases should have profit model innovation. Second, local firms should play a dominant role in the industry. Third, the selected cases should be financially sustainable and scalable. That is, the business in the case should have the potential for large-scale commercialization.

According to the above criteria and theoretical sampling [36], three companies were selected from the animation industry. All the companies were similar in terms of products, so exploration of similar challenges regarding technology, sourcing, production, distribution and marketing was possible. The cases varied in terms of organizational structure and positioning in the industrial chain, so comparison of the effect of different models adopted by different companies was accomplished. The interactive strategy was adopted for the overall research design. That is, the cases were selected, dumped, re-selected, and confirmed as research progressed, rather than determined at the very beginning.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Fan Mode

4.1.1. An Overview of Fan Mode

The Fan mode was defined as the profit model with high consumption intention but low quantity of consumers, the purpose of which was to cultivate repeated direct purchase by the consumer for a variety of forms of animation and derivative products. Japanese Season broadcast television animation demonstrated that the Fan mode was engaged in a wide variety of profitable ways:

Animation Sales

Box office earnings first, then sales of animation broadcasting rights for television and internet platform, and finally sales of audio-visual products are the typical animation sales process. There are some examples where firms directly sell audio-visual products without the first two processes mentioned above, but it is not common.

Brand Licensing and Collaboration

Get the copyright fees from authorizing other manufacturers to use the image works and design concept, and even from collaborating with them to design, produce, and sell products. These products always include, for example, stationery, toys, food, and authorized bank cards.

Content-Based Peripheral Product Sales

Sell other forms of film and television works, novels, comic books, radio plays, and stage plays adapted from the initial contents of animation; sell phased or partial results of animation, for example, Materials Collection, Original Art, OST (Original Sound Track), etcetera.; recreation based upon original content, for example, music collection, the side story novels, and comics etcetera.

Image and Design-Based Peripheral Product Sales

Sell dolls or models of representative animation characters; sell decorative or practical items of the animation; sell products that combine FMCG (Fast Moving Consumer Goods) with characters or designs in the animation.

To summarize, the Fan mode mainly focused on the development and sale of peripheral products based on the content or design, which was a key to determining whether the operation of an animation project was successful. Next, is a discussion of a typical Fan mode feature, Kuiba, an animation project lunched by Vasoon Animation Co., Ltd. in 2011.

4.1.2. A Case of Fan Mode: Kuiba

Kuiba, launched in 2011 and produced through combining two-dimensional hand-drawn and three-dimensional rendering technology, was a series of passionate, realistic works that were focusing on animated films, which told the growth story of the protagonist “Man Gi” who fought in a fantasy world. Kuiba, at the time of its launch, was positioned to target an audience of people over the age of 14, with a “realistic beauty” style. Domestic animation in 2011 featured only works for younger children, such as Pleasant Goat and Big Big Wolf, which were successful. Kuiba was popular with supporters of the animation industry and both Chinese and Japanese animation fans.

Kuiba was the first time Vasoon Animation engaged in original animation filming (Table 1). Its Research and Development began in 2006 and production in 2008. The beginning of the project planning stage had “Mountain Lingshan” shown in the marketing film out of the network in 2009, which originally planned to produce 156-episodes of TV animation and five animated films. According to the relevant report after Kuiba launched, the budget of television animation reached 80,000 yuan per minute and the television pre-sale maximum price reached several million. Simultaneously, the preferential policies in China provided subsidies for the length of time, which caused Vasoon Animation to receive approximately 1000–2000 yuan per minute. Thus, Vasoon gave up the plan of “making first the T.V. show, and, later, the movie”, rather, Kuiba was made as an animated film immediately.

Table 1.

The descriptive analysis on Animation Film-Kuiba.

Vasoon Animation, founded in 1992, was one of the earliest domestic private animation companies. It had participated in the production of scripts, sub-images, and medium-term processing of many animated works, as well as several original award-winning television animations, so it had mature TV animation production skills and production management experience. However, after deciding to make animated film, the play based television animation had to be rewritten, and technical differences between television and film also increased the difficulty of the production, which made the cost per minute increase dramatically. The total production cost for 83 min for the first episode of Kuiba, released in the 2011 Summer Edition, was about 35 million yuan. Due to the fear of the company being overtaken by venture capitalists, the production of funds came from self-financing, which did not include the cost of publicity and distribution. Although it won the praise of the target audiences of 14-year-olds, secondary school, and college students, and formed a positive reputation in the animation fan base, the box office was not very good initially. Producers spontaneously requested the stars to advertise with microblogs, which was ineffective, but the movie finally gained 3.09 million yuan, which was far away from the cost. Pleasant Goat and Big Big Wolf 3, launched during the Spring festival of the same year, captured 139.23 million yuan, and became the highest grossing animated movie. Although widely considered to be average, the Chinese animation, Seer, launched at the same time, and having a similar amount of investment as Kuiba, gained 43,510 million yuan. By contrast, it seemed that the box office earning of Kuiba was bleak.

Wu Hanqing, the producer and CEO of Vasoon Animation, said in many media interviews that the main reason for the loss of box office in the first episode of the Kuiba series was due to the lack of experience in the promotion of movie distribution. Vasoon only invited their dubbing voice actors to engage in the activities once in the early advertising, and that impact was quite limited. Moreover, the co-distribution company, Toonmax Media Co., Ltd., took a similar strategy with Pleasant Goat and Big Big Wolf that targeted young children, a process that did not fit for the older target market for Kuiba. Moreover, less row, less time, and a low attendance rate formed a vicious circle. Consequently, Kuiba fell into an awkward situation with good reviews but bad box office earnings. Based on the good reputation on the internet and the formation of the fan community, Vasoon Animation felt that it might be better to produce Kuiba continually and share the cost in the early phase. Additionally, improvements to deficiencies in film distribution, operation, and production were needed to recover the cost.

Therefore, after the launch of Kuiba, Vasoon Animation set out to continue the production of the second animated film Kuiba 2, while also mining outside the box office income, including the network and overseas distribution, exploring content based supporting roles stories and serializing it on the Comic Show. Furthermore, Vasoon re-edited Kuiba 2 and added a new title and trailer into the eleven-minute, ten-episode version of the television animation, and broadcast on Kaku Children's channel. Vasoon also simultaneously published graphic setting and original painting-based original novels, Book of Kuiba, and designed and explored image and vision-based peripheral products. However, Vasoon Animation substantially expanded its acquisition of other products in the cultural and creative industries in the form of IP (Internet Protocol) rights. The company sold peripheral products that were customized by the manufacturer through Taobao. Additionally, Vasoon employed two comic creators to adapt the animation. However, due to a lack of understanding by Vasoon Animation of comic cartoons, cooperation with the author on the basic concepts created conflict, ending the collaboration. The comic author then wrote a long diary in blogs online to criticize the company’s lack of professionalism in comic creation, utilitarian work, choice to ignore the quality of the content, and their disrespect toward the labor. These papers were widely reprinted on microblogs and forums, which caused heated discussions among fans of online animation and had a negative impact on the reviews and brand image after Kuiba launched. This was in early May 2013, not long before the release of the animated film Kuiba 2 on Children’s Day. Finally, Kuiba 2 earned 3 million yuan on the first day, the first week box office breakthrough was 20 million yuan, and the final box office earning was 25.27 million yuan.

Drawing on the lessons of Kuiba, Kuiba 2 cooperated with Tianjin Bona Media Co., Ltd., taking appropriate marketing that was more in line with the norms of film publicity, and launched planned network marketing. Since Vasoon Animation could not afford large outreach costs, Vasoon tried making the best use of Weibo, a social media channel that built on social media presence to enhance the character of the animation and the interaction between the founders and fans. Vasoon also made efforts to adjust the Kuiba 2 content to cater to young children. Based on the Research and Development and technology of Kuiba, the cost of Kuiba 2 was reduced to 20 million yuan per part, which made the box office earnings of Kuiba 2 grow dramatically when compared with Kuiba. The total box office earnings of Chinese animation films nearly doubled in 2013, as compared with two years prior, reaching 628 million yuan. The number of Chinese animated films also increased from 15 to 24, which meant that the box office earning of Kuiba 2 only approached the average level. Although there was an obvious increase, it was still a money-losing film.

To contrast, although Kuiba 2 was more mature in business operation and achieved the market-average box office earning, review among target audiences shows differentiation. The scandal about the comic destroyed the corporate image among the animation fans community, and the concession to the younger market affected the older audience as well. Having a wide range of online publicity attracting much more animation fans focus caused some audiences who had watched many works or who had some professional basis, to point out that Kuiba 2 plagiarized Japanese animation shots and had some technical problems of production. The intellectual property in other areas of the industrial chain extension capabilities and strategic integration capabilities of the weaknesses began to emerge at the same time.

4.1.3. Lessons from Kuiba

Kuiba’s series of animation projects operation experience made it easy to notice that the starting point of creative planning of Kuiba was high and it interacted well with the target audience’s fan base. Although the master team denied the imitation of the Japanese animation style, there was an obvious overlap between target audiences and the Japanese animation fan community. Given that the box office earning was limited, the audience was small enough to make money by brand licensing. Vasoon Animation also combined with the domestic market and animation fan group spending habits for toys, garage kits, and commodities, as well as re-creation novels, comics, and original net anime. Unfortunately, Kuiba, as a case of Fan mode, was not a success in the Chinese market. These experiences and lessons are meaningful to animation project operation regarding Fan mode in a domestic market. This is summarized as follows:

Insufficient Commercial Planning and Unreasonable Cost Allocation

Vasoon Animation increased the production cost at the beginning and hoped to cover that with “projected” box office earnings of Chinese animation film. It was impossible to solve the problem that television animation could not cover the high production cost that way, and this reflected the lack of awareness of the movie industry and the commercialization of the animation company that had operated for many years in a traditional manner with television. Due to a hurried transformation from television animation to animated film, the company blindly pursued the first-class technical level and image quality, but neglected the important aspect of publicity in the norm of the film industry. Based on this, the company was concerned that they might lose control of intellectual property if they chose venture capital, but in not doing so, they also lost the opportunity to promote and operate Kuiba with better capital. The self-made production cost of 35 million yuan put financial pressure on the company and it became a heavy burden on the follow-up operation, allowing the enterprise to fall into the dilemma of short-sighted behavior due to financial pressure.

Poor Strategic Integration and the Blind Expansion of Internal Chain

After the loss of box office earning by Kuiba, Vasoon Animation considered using the good reviews to develop other forms of derivative products in the cultural and creative industry. Adaptation of the works for comics, books, and development of peripheral products was adapted, for example. However, Vasoon Animation turned to unfamiliar parts, like comic production, development of peripheral products, and sales, rather than the common way, like cooperating with other companies or licensing, which ignored the condition and capacity of the company and violated the commercial discipline. It increased the burden on business operation and affected the enterprises’ investment in the development of animation works as the core of the content.

4.2. Placement Mode

4.2.1. An Overview of Placement Mode

The Placement mode is defined as the profit model with low consumption intention but high quantity of consumers, the purpose of which is to capture the value of consumers’ attentions by placing advertisements in the animation product. The mode is quite popular in the film, television, and other industries, and plays an important supporting role in the profit model. However, it is not common in the field of animation because the audience base is quite limited.

When compared to the Fan mode, the Placement mode seems to be rather simple, only profiting from advertisement placement. However, the cost of the placement mode is much lower, the operation is easier, and the collaboration space is much broader, thus allowing it a stronger practical feasibility. Next, a typical Placement mode of Miss Puff, an animation project lunched by Youku.com and Beijing Hutoon Co., Ltd. in 2011 will be discussed.

4.2.2. A Case of Placement Mode: Miss Puff

Miss Puff was an original net anime about an urban white-collar female with the theme of urban life and emotion, with the aim of pursuing quality of life and spending power (Table 2). Each episode within an animated cartoon told an independent story of Miss Puff in just over 10 min. It was well received by viewers on Youku since it was launched in 2011, and produced a total of 63 episodes in five seasons, a 28-episode miniseries, and a microfilm. The cumulative number of broadcasts was more than 300 million.

Table 2.

The descriptive analysis of Animation Film-Miss Puff.

The division of Youku.com and Beijing Hutoon Co., Ltd. was clear in the process of cooperation. Hutoon took charge of content production, while Youku took charge of promotion and broadcast, and they shared the production cost. They also developed derivative products together and shared copyright, and divided earnings by a certain percentage. Regarding technology, Hutoon had a director, Pi San, who was a leading figure in the Chinese animation industry. Pi San innovatively made Miss Puff a combination of FLASH and live photography, which not only created a unique artistic style, many live shots also largely reduced the difficulty and cost of using animated technology. More importantly, this creation made Miss Puff less animated and more likely to break the general public’s notion of animating younger people, allowing for Youku to promote the network animation as a homemade drama.

Although Miss Puff succeeded in ratings, from the perspective of the animation project, the audience did not pay to watch the video on the network. The traditional source of online video revenue was only video patch ads for Miss Puff to develop brand value and turn the attention of the audience into revenue for the animation project. When considering the content of the form of Miss Puff features, the main role was very small, and the prominent visual image was only the main character, Miss Puff. Each episode told the story in the independent form, which made it difficult to shape the character and relationship. This made Miss Puff in accordance with the traditional ideas according to the work itself, but to develop derivative products or content was more limited; only the small pylons, picture books and other forms of print were suitable for the style of the work. Thanks to the high click-through rate of Youku’s platform and its clear and accurate target audience positioning, Miss Puff realized the groundbreaking profit through the placement of advertisements. The company also realized commercial cooperation through Youku because the work illustrated female urban life, and the characteristics of the real part of the screen through the Youku platform helped to obtain business cooperation, food, commodities, devices, and cars, which helped them to gain broader profit space. Since the animation was produced continually, and there was gradual formation of brand influence, Miss Puff also started to operate the official product online shop, sell its own brand of cosmetics, fashion accessories and daily necessities, and tried the packaging and management of fashion brands.

4.2.3. Successful Experience of Miss Puff

Miss Puff was produced by both Youku.com and Beijing Hutoon Co., Ltd. and was exclusively broadcast in Youku, so the companies only benefitted from pre-movie advertising and advertisement placement at the very beginning. The companies began to expand the animation brand based on fashionable brand, in the long run. The successful case provides Placement mode with the classical paradigm as to how the content producer cooperated with the internet platform. It also was not hard to see that the animation project could profit through the implantation mode and the relationship with the development of Internet media was also inseparable. The company did not succeed by accident, and there were some critical factors included.

High-Quality Content and Precise Market Positioning

Pi San, the director of Miss Puff, graduated from the art department with the major of oil painting from Shanxi University, had rich experience in independent animation production and cooperation with television, film, and music, as well as strong aesthetic art competence and sensitivity to business. The content of the film came from city life, which included true feelings and easily aroused the resonance of the audience. When considering that the target audience was white-collar females and college students that were prepared to enter society, the companies accurately segmented the market and found consumers who had high purchase capacity and commercial cooperation intention, which created a solid foundation for success.

Achieve Low-Cost and Efficient Dissemination through the Network Media

The dissemination of online media itself had the characteristics of low copy cost, fast transmission, and strong interaction. The convenience and availability met the habit of target audiences at any time. The highly interactive nature of online media enabled Miss Puff to quickly gather feedback and opinions from audiences through click through rates, reviews, and social media channels, and to reflect on follow-up productions. It was also important for Miss Puff to maintain sound comment and incremental communications.

Sound Forms of Cooperation and Reasonable Division of Labor

Thorough cooperation of Youku.com and Beijing Hutoon Co., Ltd. was one of the necessary factors for Miss Puff to be successful. The common interests of a clear division of labor, complementary advantages, and close cooperation made the team focus on the creativity and production of animation and ensured the quality of work. Furthermore, Youku provided excellent online and offline marketing resources and a professional business cooperation platform to achieve the optimal allocation of resources, which helped Miss Puff to succeed in the long term.

4.3. Popular Mode

4.3.1. An Overview of Popular Mode

The Popular mode is defined as the profit model with high consumption intention and high quantity of consumers, the purpose of which is to cultivate a direct, repeated purchase habit of the consumer for a variety of forms of animation and derivative products, and to capture the value of consumers’ attentions by placing advertisements in the animation product.

Although combining the revenue model of Fan mode and the Placement mode, the Popular mode also engaged in a wide variety of profitable ways, including animation sales, brand licensing and collaboration revenues, content-based peripheral products sales, and image and design-based peripheral product sales, and sales of placed advertisements, there were still differences between the Popular mode, the Fan mode, and the Placement mode.

Similar to the Fan mode, the two key points of Popular mode are the formation and cultivation of audiences and consumers, as well as a mechanism for perfecting the brand authorization and derivative product development and sales in the industrial chain.

The difference between the Popular mode and the Fan mode is that the former has much stronger profiting capability of animation sales and brand licensing and collaboration revenues, while the latter has stronger profit capability of peripheral products sales. Moreover, the difference between the Popular mode and the Placement mode was that the former did not only depend on the profit from advertisement placed in the animation, since the advertisement sale was one of the supporting profitable ways.

The difference between the Popular mode and the Fan mode in terms of cultivation of audiences and consumers was that the former emphasized the accumulation of quantity, thus the cultivation of audiences and consumers relied more on strong channel resources as compared with Fan mode, which depended on symbolized content that was based on creativity and artistic creation to interact with fans. Presently, Popular mode, as a typical mode in China, mainly cultivates audiences by television, and has difficulty in operation due to the long cash conversion cycle and high entry threshold of the channel. However, with the development of the internet, smart mobile devices and new media, it is realizable to cultivate audiences and consumers by the low entry threshold of channel-like video websites, so there is a future possibility of more successful cases.

Popular mode was also different from Fan mode in terms of brand licensing and development of derivative products and sales, due to the limited rights protection capacity and pirated market environment, rather than lacking a cooperation mechanism. The recent increase in the awareness of copyrights and laws, as well as capital infusion by large culture media companies (e.g., Fantawild Animation Inc., Hong Kong, China), toy corporations (Guangdong Alpha animation, Guangdong, China), video websites (Youku and Tudou), and absorption and adaption of qualitative creativity and content, has made it hopeful to see the development of Popular mode with the increasing channel resources and capacity of strategic integration and expansion of the industrial chain. To summarize, it is a huge challenge for the creative planning, production, and operation of an animation project to achieve both high consumption intention and high quantity of consumers. Next, illustration of a typical Popular mode of Pleasant Goat and Big Big Wolf, an animation project lunched by Creative Power Entertaining Co., Ltd. from 2005 will follow.

4.3.2. A Case of Popular Mode: Pleasant Goat and Big Big Wolf

Pleasant Goat and Big Big Wolf, launched by Creative Power Entertaining Co., Ltd., was a television animation, which was voluminous, funny, and intellective. The basic information is as follows (Table 3).

Table 3.

The descriptive analysis on Animation Film-Pleasant Goat and Big Big Wolf.

The company formulated the marketing strategy of “broadcasting to the market first through television”, then targeting local children’s channels and developing audiences with the exposure rate. When considering that the unmanageable cost of producing animated films and the long-term exposure needed to foster the audience, Pleasant Goat and Big Big Wolf opted to minimize production costs by using FLASH technology (about 10,000 yuan per minute), to attract audiences with simple and vivid images and an interesting plot. Workers of Creative Power Entertaining Co., Ltd. told the media, to achieve the high visibility of the work, Pleasant Goat and Big Big Wolf did not benefit in the first two years to increase exposure.

Since television animation premiered on Hangzhou TV Children’s Channel it experienced stable ratings and unprecedented popularity with the audience, so the TV and television broadcasters gradually expanded 75 TV stations, which had broadcast Pleasant Goat and Big Big Wolf repeatedly by 2013, including 14 seasons and 530 episodes. Between 2005 and 2009, Pleasant Goat and Big Big Wolf had built its own Chinese animation brand gradually and cultivated large amounts of audiences and consumers through television.

During the production of the television edition, Creative Power Entertaining Co., Ltd. had begun to consider the production of movie plans. However, domestic animation film faced a high production cost and low box office earnings before 2008, so the company waited for a right time. Domestic animation film in 2008 started to enter a stage of rapid increase in output and growing demand, and thus the company believed that the film of Pleasant Goat and Big Big Wolf could cover the cost based on market research, and even make profits. Following negotiations with Shanghai Media Group, which had animated marketing and distribution experience, Creative Power Entertaining decided to produce the animation film of Pleasant Goat and Big Big Wolf, taking the “whole family concept” as its marketing strategy to bring the movie box office growth effect by “hand in hand”.

The television animation of Pleasant Goat and Big Big Wolf finished in 2009 and was successful in its first animated film. Following that, Creative Power Entertaining started to transform from television animation to animated film. Pleasant Goat and Big Big Wolf had launched one film per year during the Spring festival since 2009, earning sound profit.

The important thing to note is, after the peak of 167.55 million at the box office of the fourth film in 2012, there was a declining trend since 2013 and the box office earning in 2015 was even lower than that of 2009. There were two reasons behind it: one was the change in the market environment. Increasing quantities of domestic animation films and distribution of new brands like Boonie Bears, for example; another was internal change at Creative Power Entertaining in terms of asset structures and leaving of creators.

Following the end of television animation in 2009, Huang Weiming, one of the creators, left Creative Power Entertaining due to disagreements with the company’s overall direction of development. Between 2009 and 2011, Pleasant Goat and Big Big Wolf became popular all over the country. Although the value of works and brands was recognized in the market, Creative Power Entertaining lacked the bargaining power in the market due to the strong position of television and film distribution channels. That meant the company could not cover the cost although the ratings were high. The box office earning was tens of millions of yuan, while the revenue was only several million yuan. Furthermore, the profit from content-based derivative product sales was discounted due to the undisciplined market of derivative products and lacking copyright protection. Creative Power Entertaining, in 2011, maintained the copyright of the animation and story, as well as the right of content creation, but sold trademarks of image and derivative products and licensing, in the form of capital operation, to Disney and Imagi International Holdings Limited (IMAGI) and made a tripartite agreement of brand management. An investor named Su Yongle and another master named Lu Yongqiang then sold shared cash, Guangdong Alpha animation and Culture Co., Ltd., in 2013, took full control of both IMAGI and Creative Power Entertaining, capturing the majority of copyright and operation rights. However, during the capital operation of different owners, the acquirer’s lack of innovation and construction of brand image and content, added to the departure of creators one after another, and made the animation film gradually fall into the embarrassment of overdraft brand value. Box office earnings also reduced in the context of intense competition in the animation film market. Whether Pleasant Goat and Big Big Wolf could change the unfavorable trend and recreate the success depended on, ultimately, whether the present team could achieve innovation and break the audience for the series of animation films aesthetic fatigue.

4.3.3. Lessons from Pleasant Goat and Big Big Wolf

It was easy to notice that the most commonly successful path of animation project, Popular mode, was still from a young television animation to an animated movie with children driving parents into theaters. CCTV (China Central Television) started broadcasting the new Chinese animation brand Boonie Bears (Fantawild Animation Inc., Hong Kong, China) in 2012 and its animation films in 2014 and 2015 hit a staggering 247.9 million yuan and 29.291-million yuan, respectively. The box office series of Boonie Bear domestic animation brands, was also a case of Popular mode other than Pleasant Goat and Big Big Wolf. Their enlightenments include:

Preheating the Market with Promotion

Although Creative Power Entertaining used the lowest cost by producing television animation with FLASH, it took the company over four years to cover the cost. Boonie Bears was an animation brand that was popular with audiences as soon as possible, but also showed a loss while broadcasting on television for two years before being released in 2014. Therefore, although saturating the market with high exposure through television channels was feasible, it put forward very high requirements on the capital input and working ability of enterprises in the pre-operation of animation projects.

Strategic Integration and Expansion Capacity of Industrial Chain

Although Pleasant Goat and Big Big Wolf had made success in television animation, film, and branding, it was difficult for Creative Power Entertaining to capture the value through content and derivative products. It eventually acquired it by capitalization, showing strong domestic channels and weak copyright protection, with the original motivation similar to the lack of strategic integration capabilities.

5. Conclusions

This paper divides feasible profit models of animation projects into Fan mode, Popular mode, and Placement mode, and discusses the domestic cases of them and their operation, after discussing the operation and profit model of animation projects.

There are few successful cases of Fan mode among domestic animation projects. These animation projects (e.g., Kuiba) reflect that in the case of lacking in-depth cooperation on the industrial chain, Fan mode should be considered cautiously for companies that are weak in the whole business plan and internal management due to the high production cost and investment risk. Regarding domestic development of animation projects using Fan mode, animation companies should explore how to find a balance between satisfying the fans’ cultural taste and controlling the production cost. How the Fan mode should be formed within the Chinese market and industrial environment with reasonable cooperation in the industrial chain path also needs more practical attempts and discussions.

Placement mode is a typical model that was formed by the rise of the online media industry in China’s animation industry. Similar to the movie media industry in the United States of America, or the animation and television media in Japanese animation, there is a close relationship between online media and the implanted model. The cooperation model of Miss Puff, which was launched by Youku.com and Beijing Hutoon Co., Ltd., also provides Placement mode with a classical cooperation paradigm of content producer and channel platform. Placement mode is very suitable for transforming independent animation to commercial ones, but it is limited by the content and creation based on the unique profit model. Thus, it cannot meet the needs, in most cases, if a project depends on this mode totally, and, as for most projects, they can partly draw on the experience of cooperation with other platforms or introduce advertisement placement as a supplement of profit model.

Popular mode is the most mainstream development path for Chinese animation projects. Taking Pleasant Goat and Big Big Wolf as the example, this project cultivates the market through long-time television broadcast at first, and then extends the box office receipts through animation films and other links to toys, peripheral products, entertainment industry income, etcetera. Placement mode requires a lot of upfront capital investment, strategic integration and expansion of the industrial chain for the main actors in animation projects, when considering that its profitability is greatly affected by the market environment, such as copyright protection and piracy. The biggest problem is how to protect the interests of enterprises and market environment. However, it should be noted that with the capital market’s concern for the animation industry, other links of cultural and creative industries, such as cultural media groups, online video media, entertainment industry, and toy industry began to integrate capital, channel resources, strategic integration, and industrial chain expansion capabilities into the animation industry. This improvement of the market environment makes it possible for the Placement mode to extend the industrial chain vertically, and to be widely applied to cultural media companies, large cultural and creative companies, or media based on successful experiences abroad.

There are both distinctions and relations among Fan mode, Placement mode, and Popular mode, and it is possible for these three modes to transform under the market and media environment. A work, based on Fan mode, introduces the profit model of placement advertisement with the increase in the fan community and impacts, and then transforms into Popular mode. Additionally, work based on the Placement mode might promote the consumption intention of consumers by content-based innovation and improvement, and then turn to Popular mode; when separating fan community from audiences of Popular mode, it can also include Fan mode. Therefore, much more possibilities of translation and combination among profit models for the animation industry remain to be explored for the future practice of the animation industry. Moreover, the case study method was employed to explore the profit model innovation. Therefore, quantitative research can be adapted in the future.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support from a grant awarded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (71572017; 71472186; 71772014), Beijing Social Science Research Foundation of China (15JGC144) and The Workshop in Department of Strategy, Business School, Beijing Normal Univesity, Beijing, China (312231103).

Author Contributions

Hao Jiao, Yupei Wang, Hongjun Xiao, Jinaghua Zhou and Wensi Zeng designed the research and wrote the paper. Hao Jiao and Yupei Wang made the literature review. Hongjun Xiao, Jinaghua Zhou and Wensi Zeng interviewed the companies. Jianghua Zhou analyzed the data. Hao Jiao, Yupei Wang, Hongjun Xiao and Wensi Zeng wrote the discussion and conclusion.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Choi, Y.; Lee, E.Y. Optimizing risk management for the sustainable performance of the regional innovation system in Korea through metamediation. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. Int. J. 2009, 15, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangwook, K. Developments and prospects of animation industry in China. China Sinol. 2012, 16, 125–156. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, S.H.; Hu, M.M.; Su, B. Research on investment efficiency and policy recommendations for the culture industry of China based on a three-stage DEA. Sustainability 2016, 8, 324–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, D.; Tang, L. The present situation of animation industry in China and the development of the native animation talents. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Applied Social Science, Changsha, China, 19–20 March 2011; Zhou, Q.Y., Ed.; Information Engineering Research Inst.: Newark, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 508–512. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.Y.; Schirato, T. Chinese creative industries, Soft power and censorship: The case of animation. Commun. Politics Cult. 2015, 48, 24–43. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, X.M. Analysis and implications of development experiences of Korea’s animation industry. Agro Food Ind. Hi-Tech 2017, 28, 2916–2918. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.Y.; Chiu, Y.H. Evaluation of the policy of the creative industry for urban development. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, R. The Economic, Creation, Communication and Technology (ECCT) model of cultural and creative industry development. In Proceedings of the International Symposium—Management, Innovation & Development (MID2014), Beijing, China, 25–26 October 2014; Kuek, M., Zhang, W., Zhao, R., Eds.; St Plum-blossom Press: Hawthorn East, Australia, 2014; pp. 746–749. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, W.; He, W. Chinese Animation Industry and Consumer Survey Report: 2008~2013; Beijing Normal University Press: Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. China’s Animation Industry Development Pattern Research. Master’s Thesis, University of Electronic Science and Technology, Chengdu, China, 20 June 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, X.L. Construction of China’s Animation Industry Chain. Master’s Thesis, Tongji University, Shanghai, China, 20 June 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Horng, S.C.; Chang, A.H.; Chen, K.Y. The business model and value chain of cultural and creative industry. In Proceedings of the World Marketing Congress/Cultural Perspectives in Marketing Conference, Ruston, LA, USA, 28 August–1 September 2012; Plangger, K., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2012; pp. 198–203. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, W.H.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, X. Creative Industries: Business model and current situation analysis in China. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Engineering Management Conference, Lost Pines, TX, USA, 29 July–1 August 2007; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 282–287. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, X.L. Innovation development model research in Shenzhen cultural industries. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Engineering and Business Management, Wuhan, China, 22–24 March 2011; Scientific Research Publishing: Irvin, CA, USA, 2011; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Benghozi, P.J.; Lyubareva, I. When organizations in the cultural industries seek new business models: A case study of the French online press. Int. J. Arts Manag. 2014, 16, 6–19. [Google Scholar]

- Vassiliki, C. Digital dividend aware business models for the creative industries: Challenges and opportunities in EU markets. Commun. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2009, 49, 565–569. [Google Scholar]

- Lerro, A.; Schiuma, G. Business model innovation in cultural industries: State-of-the-are and first empirical evidences. In Proceedings of the 10th International Forum on Knowledge Asset Dynamics (IFKAD), Bari, Italy, 10–12 June 2015; Spender, J.C., Schiuma, G., Albino, V., Eds.; Ikam-Inst Knowledge Asset Management: Matera, Italy, 2015; pp. 1616–1627. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.B. Research and Development Mode of the European Animation Industry-in France, Britain, Germany Case. Ph.D. Thesis, Zhejiang University, Hang Zhou, China, 20 June 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q.J. Animation Art of Japan; Shanghai Jiao Tong University Press: Shanghai, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Lin, C.F.; Wu, S.S. Structure analysis of Japanese comics & animation industry. Packag. Eng. 2010, 31, 98–100, 107. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, L.L.; Lee, S.W. Study for consolidating competitiveness of Chinese animation through the Comparison of animation industry between Korea and China. Korean J. Anim. 2008, 4, 225–242. [Google Scholar]

- Dalecka, M.; Szudra, P. The identification and operation of creative industry enterprises in the context of economic security in the region. In Proceedings of the 5th Central European Conference in Regional Science (CERS), Kosice, Slovakia, 5–8 October 2014; Nijkamp, P., Kourtit, K., Bucek, M., Eds.; Inst. Regional & Community Development, Faculty Economics, Technical University of Kosice: Kosice, Slovakia, 2014; pp. 156–165. [Google Scholar]

- Magdalena, R. Family businesses in creative industries. In Proceedings of the 8th International Scientific Entre Conference on Advancing Research in Entrepreneurship in the Global Context, Krakow, Poland, 7–8 April 2016; Wach, K., Zur, A., Eds.; Foundation Cracow University Economics: Krakow, Poland, 2016; pp. 897–905. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z. Decision-making model for performance assessment of cultural industry. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Electronic, Information Technology and Intellectualization (ICEITI), Guangzhou, China, 18–19 June 2016; DEStech Publications, Inc.: Lancaster, PA, USA; pp. 343–348. [Google Scholar]

- Strazdas, R.; Cerneviciute, J. Continuous improvement model for creative industries enterprises development. Transform. Bus. Econ. 2016, 15, 46–60. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Y.N. Characteristics of Japanese Animation Industry. Ph.D. Thesis, Shandong University, Jinan, China, 20 June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.L. On International Competitiveness of Contemporary U.S. Animation Industry: Based on Innovative Advantages. Ph.D. Thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 20 June 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Liu, L.Q.; Li, Y.S. Research on management mode of cultural and creative industries park. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Applied Social Science (ICASS 2012), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 1–2 February 2012; Hu, J., Ed.; Information Engineering Research Inst.: Newark, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.Y.; Sun, M.; Xu, A. Research on the economic value and the value chain of creative industry. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Management and Information Technology (CMIT), Yichang, China, 26–28 October 2013; Peng, A., Ed.; DEStech Poblications, Inc.: Lancaster, PA, USA, 2013; pp. 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- Madudova, E. Sustainable creative industries value chain: Key factor of the regional branding. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference on Marketing Identity 2016: Brands We Love, Slovak Academic Science, Smolenice, Slovakia, 8–9 November 2016; Petranova, D., Cabyova, L., Bezakova, Z., Eds.; Faculty Mass Media Communication, University of Ss Cyril & Methodius Trnava-UCM Trnava: Trnava, Slovakia, 2016; pp. 372–382. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, P.X.; Song, L. The innovation of Chinese animation’s profit model. J. Chengdu Univ. 2013, 1, 93–95. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, D. Animated Films Profit Model Study. Ph.D. Thesis, China Art Research Institute, Beijing, China, 20 June 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.D. A comparative research on profit model of web animation. Art Des. 2014, 6, 74–76. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S.H. How to promote animation industry in Korea-with emphasis on the importance of creative animation for theaters and proportion of animation programs relative to the total television shows. Korean J. Anim. 2005, 1, 323–348. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, B.; Zheng, B. The research of the way on promoting the development of animation industry and the Chinese cultural soft power. In Soft Power Theory Development, Practise and Innovation: Proceedings of the 3rd (2013) International Academic Seminar of Soft Power, Jinan, China: (ICNSP); Zhu, K., Zhang, H., Eds.; Aussino Academic Publishing House: Marrickville, Australia, 2013; pp. 169–173. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory; Aldine: Chicago, IL, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Weick, K.E. The generative properties of richness. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).