Effective Disclosure in the Fast-Fashion Industry: from Sustainability Reporting to Action

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- focal companies, due to their large size, global brands, media visibility, and reliance on demanding institutional investors based in developed countries; and/or

- Move beyond reporting towards action;

- Move beyond financial performance towards sustainable value creation; and

- Move beyond corporate boundaries towards value creation for the broader SC ecosystem.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Complex SCs in the Fast-Fashion Industry

- Downstream activities: activities carried out by retailers acting as focal companies that are characterised by high competition (prices and speed), high volume, and high visibility.

- Upstream activities: activities carried out by suppliers following focal companies’ demands that are characterised by high dynamism (and pressure), high volume, labour intensiveness, social complexity, the geographical dispersion and fragmentation of production, high levels of pollution and contamination, and generally low profit margins.

2.2. Fast-Fashion Industry Sustainable Value Creation and Collective Impact

2.3. From Sustainability Reporting to Effective Disclosure

2.4. Research Objectives

3. Methods and Data Analysis

3.1. Sample Description and Data Analysed

3.1.1. Sample Selection: The Fast-Fashion Companies

3.1.2. Inditex and H&M Sustainability and Integrated Reporting

- Annual report (Inditex; Supplementary Materials S1); and

- Sustainability report (H&M; Supplementary Materials S2).

3.1.3. Sustainability Reporting Analysis—Key Elements

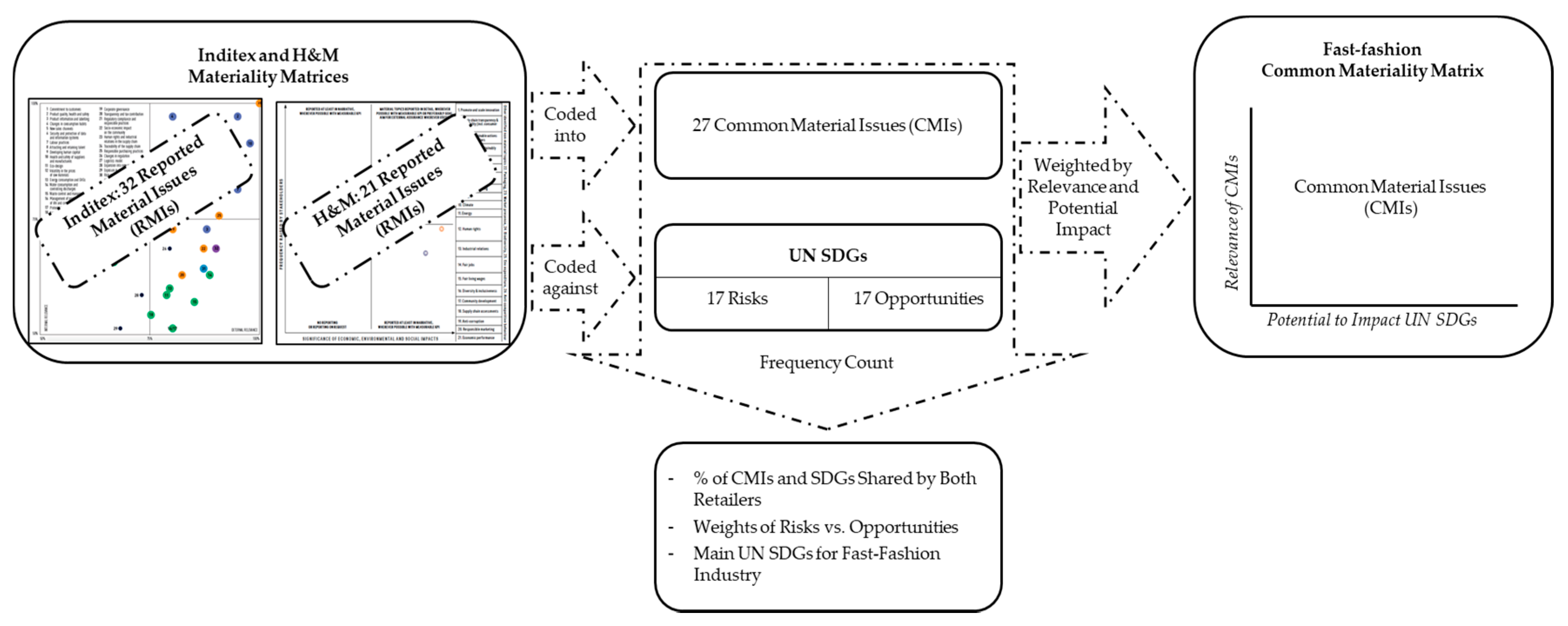

- Reported Material Issues (RMIs): The points appearing on each company’s materiality matrix (i.e., the points that are sufficiently important to report).

- Common Material Issues (CMIs): The minimum number of material issues that summarise all of the RMIs in the fast-fashion retailers’ materiality matrices, and thus can be considered important for the broader fast-fashion ecosystem. It is possible for a CMI to relate to an RMI that appears in only one of the two matrices.

- Reported Actions towards Sustainability (RASs): The activities described in each company’s annual or sustainability report as having been implemented to tackle the RMIs.

- United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Framework: Since both Inditex and H&M have declared their alignment with, commitment, and contribution to the SDGs, we take them as the frame from which we have deductively derived the categories for the analysis of the materiality matrices. We chose the SDGs, as they represent a main framework toward new actions for those companies that aim to adopt new sustainability activities and practices (UN, 2015). Based on the descriptions of the 17 goals in the main document published by the UN [21], we set up the SDG framework (Table 1), which includes risk and opportunities around the SDGs. Those descriptions led us to define actions and practices that companies and other actors can adopt to contribute to SDGs, differentiating between risks (what need to be avoid) and opportunities (what should be developed/fostered). This produced 34 possible categories through which to frame the CMIs (Table 1).

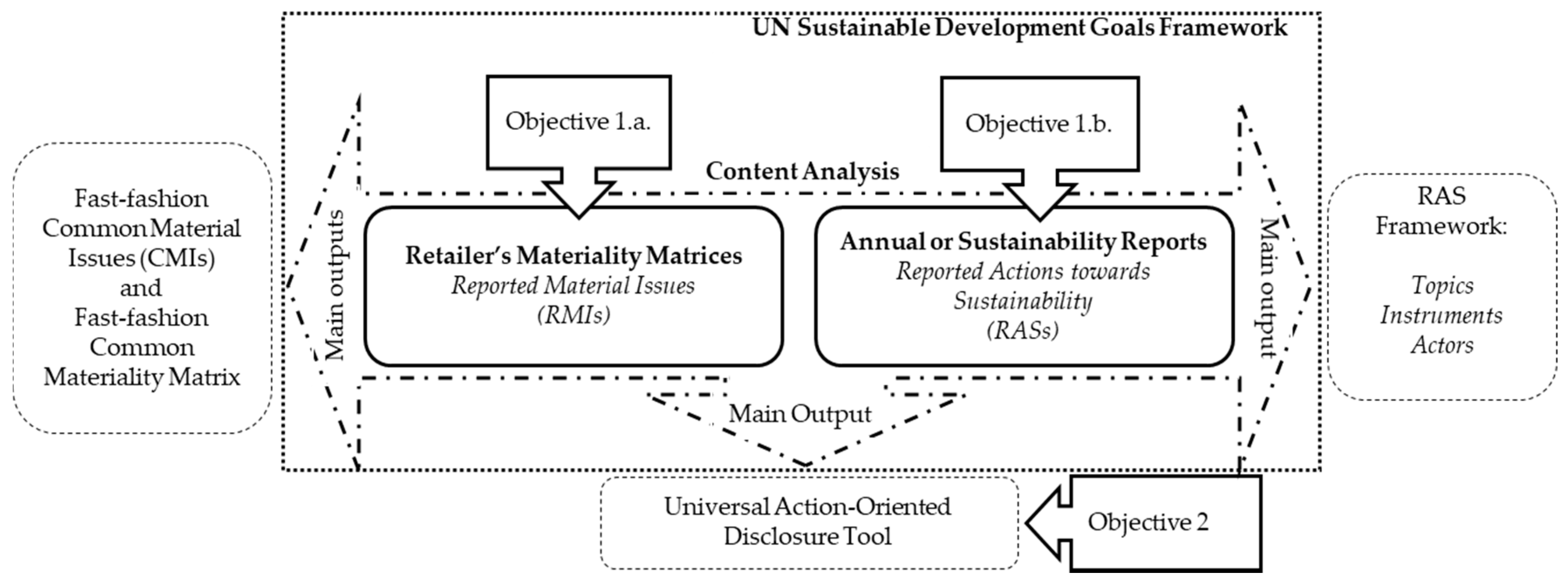

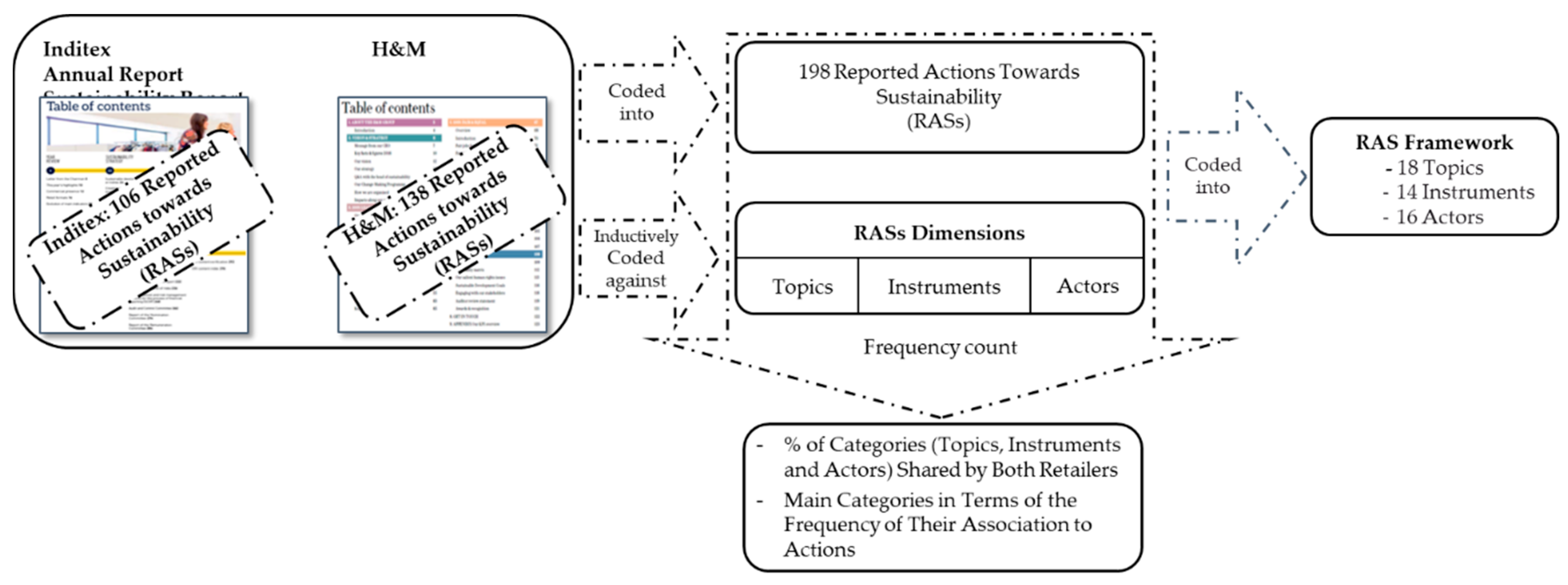

3.2. Content Analysis and Research Process

3.2.1. Objective 1.a. Retailer’s Materiality Matrices Analysis: Comprehensive Map of the Sustainability Challenges for Fast-Fashion SCs

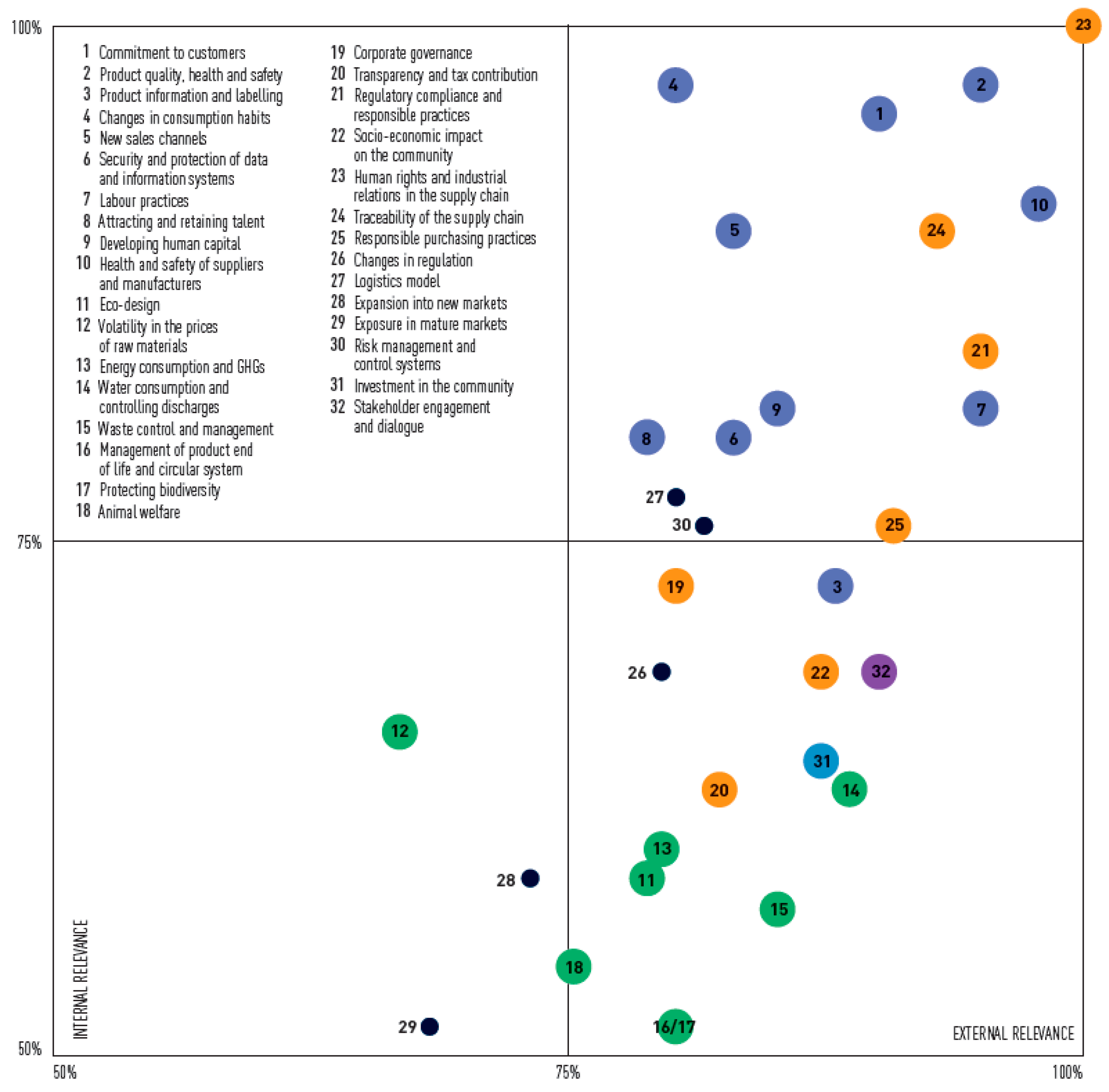

- Subject of analysis: Inditex and H&M’s materiality matrices.

- Unit of analysis: RMIs.

- Content analysis process: We coded the RMIs in the materiality matrices of the two leading fast-fashion companies against the 34 SDGs categories in Table 1. Next, we grouped all of the RMIs into 27 CMIs, which are subsequently rated per their potential to impact SDGs and their relevance in the original materiality matrices. We finally performed cross-tabulation and frequency counts on the results from the previous analysis.

- Coding reliability: The first author performed the initial coding, and the results were discussed among the three researchers until agreement was reached for each coding. In the Results section, we illustrate with an example how the agreements were reached.

- Main outcome: CMIs and a fast-fashion common materiality matrix.

3.2.2. Objective 1.b. Annual and Sustainability Reports Analysis: Analysis of Current Fast-Fashion Industry Actions in Pursuit of Sustainability

- Subject of analysis: Inditex’s annual report and H&M’s sustainability report.

- Unit of analysis: RASs.

- Content analysis process: The annual or sustainability reports of the two retailers were analysed to identify significant RASs. We followed a qualitative codification process [54,55]. The reports were analysed carefully by following three levels of codification [56]. We did this analysis for each company separately. The first level of codification includes an inductive open coding analysis of first-order concepts, which includes the list of actions connected to sustainability reported by each company. The second level of codification includes second-order themes that joined the main similarities and differences between the two companies. Finally, the third level of codification resulted in three axial codes [56]. We finally performed cross-tabulation and frequency counts on the results from the previous analysis.

- Coding reliability: The first authors of this manuscript did the first two levels of coding, while the two main authors did the third level of codification by building the aggregate codes for the three final axial codes.

- Main outcome: Framework of RASs.

4. Results

4.1. Objective 1.a. Comprehensive Map of the Sustainability Challenges for Fast-Fashion SCs

4.1.1. Materiality Matrices Coding

4.1.2. Building the Fast-Fashion Common Materiality Matrix

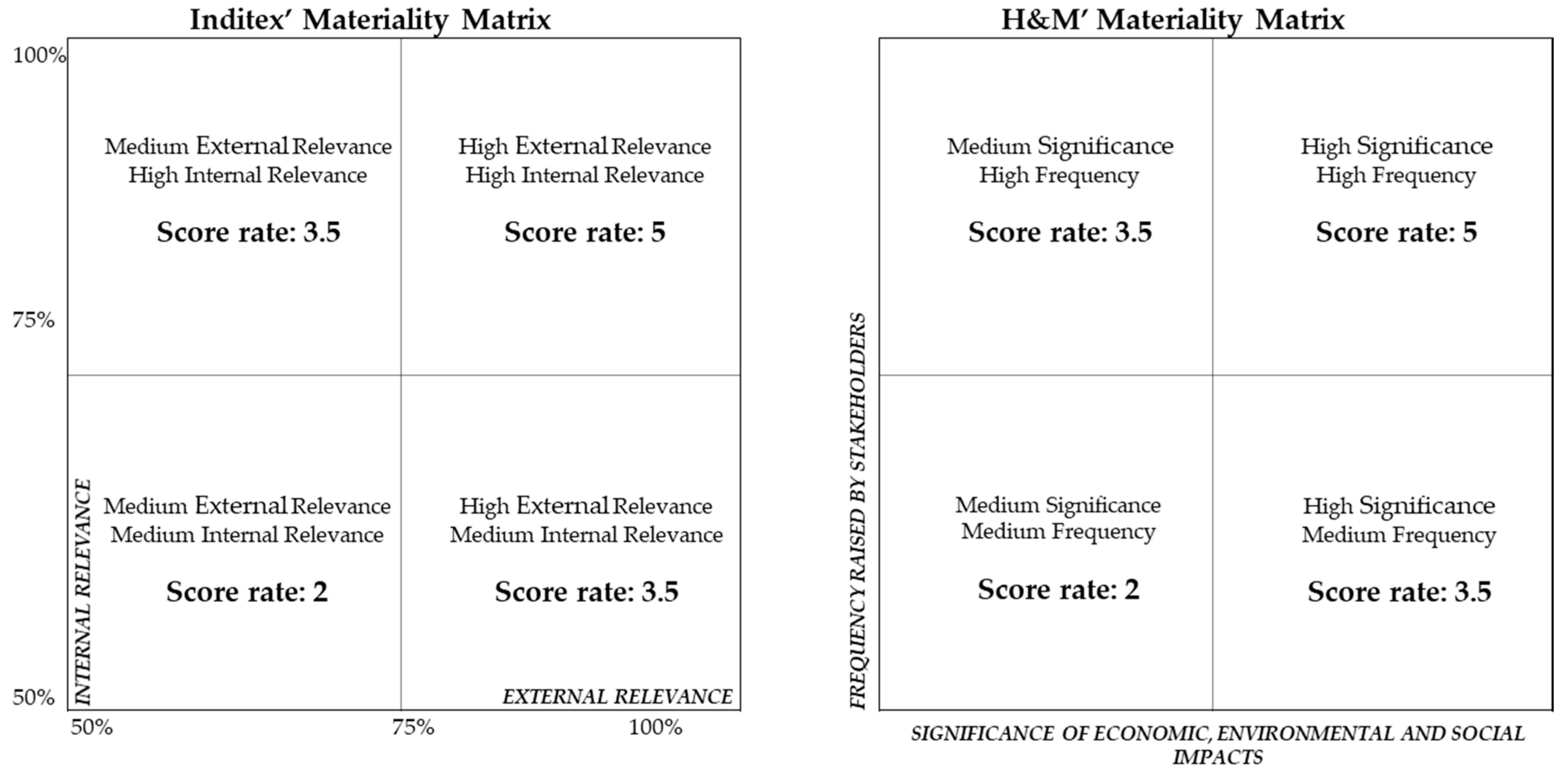

- i.

- The relevance to the focal companies and stakeholders was calculated based on the importance of each RMI that was condensed into each CMI in its original materiality matrix. Depending on the position of each RMI in the Inditex and H&M materiality matrices, we assigned a value, as shown in Figure 3.

- ii.

- The potential to impact the SDGs appears in Table 3, Column 3, which shows the percentages of risks or opportunities possibly affected by each CMI.

4.1.3. Cross-Tabulation and Frequency Counts

- the CMIs shared by the two retailers (i.e., the CMIs relating to a RMI in both materiality matrices);

- the connection between the SDGs and the CMIs; and

- the relation between risks and opportunities.

- 3.

- Opportunities clearly surpass risks (72% vs. 28%). This reinforces, on one hand, the urgency of leveraging the industry development potential of the wider fast-fashion ecosystem, and on the other hand, indicates the need to go beyond voluntary reporting, which might be positively biased (Table 4, Columns 4 and 5).

4.2. Objective 1.b.: Analysis of the Current Fast-Fashion Industry Actions in Pursuit of Sustainability

4.2.1. Annual and Sustainability Reports Coding

- Topics: The broad questions the RAS seeks to tackle.

- Instruments: Strategies, policies, and practices through which the RASs are implemented in practice.

- Actors involved: Each player (from the wider fast-fashion ecosystem) participating in the execution of the RASs.

4.2.2. Building RAS Framework

4.2.3. Cross-Tabulation and Frequency Counts

- Comparing the results of the two companies’ reports; and

- Performing frequency counts of the three RSA dimensions over the coded actions. Although we are aware of the flaws associated with frequency measurements, which we will briefly underline in the limitations section, we consider this indicator relevant and appropriate for our analysis under the rationale of communication as performative, and that talk is a precursor to action [42]. It will follow that the more times something is reported, the closer it becomes to action (and the opposite holds true). Thus, it fits our goal of pushing sustainability reporting into action, and helping reveal orphan issues that are key for sustainable value creation.

- 1.

- The three dimensions indicate a high level of coincidence between the two studied retailers (72% of the topics, 100% of the instruments, and 87.5% of the actors are shared by the two companies’ RASs) (Table 6, Column 2). These results may suggest, on one hand, that the RSAs may constitute the skeleton of the action-oriented disclosure framework we seek. However, on the other hand, it might also suggest a possibility of orphan issues not being tackled by fast-fashion retailers due to their complexity or difficulty.

- 2.

- The most frequently coded elements from each category (Table 6, Column 3) reveal that there is still an important gap between reporting and action, and that filling this gap may introduce trade-offs within the core business of fast-fashion.

- Topics. Of the 198 actions under analysis, only 1% dealt with Responsible Consumption and End of Life; 5.5% addressed Raw Materials Sustainability; and a rather low 6% had to do with Traceability and Transparency, a key aspect in complex textile SCs. The analysis also showed that the highest proportion of actions (35%) related to human rights (Compensations and Benefits, Social Equality, Bargaining Power, etc.), which was likely due to the seriousness of these topics, as well as related social pressure and media impact. The concern here is whether tackling only ‘tip-of-the-iceberg’ topics will truly solve sustainability issues in practice.

- Instruments. The analysis showed that most efforts go towards Training, Education, and Awareness Campaigns (28%) and Assessment and Monitoring (17%). Although these areas are needed as instruments of transversal support, they will not transform the industry in the short term. On the other hand, Sustainable Sourcing Strategies and Sustainability-Oriented Investments—approaches that could have more immediate and durable impacts—attracted only 5% and 2.5% of the actions reported, respectively.

- Actors. The frequency count showed that the core group of actors actively involved in the execution of the RASs was limited, for a high percentage of the actions, to retailers, suppliers (direct and indirect), workers, and NGOs. The positive reading of this result leaves room for hope, suggesting that solving sustainability issues is not impossible, but rather that many SC actors, stakeholders, and other stakeseekers have not yet begun to proactively collaborate on a solution. This interpretation supports our initial assumption concerning the urgency of building a shared disclosure framework capable of uniting the wider ecosystem’s actors around a common goal.

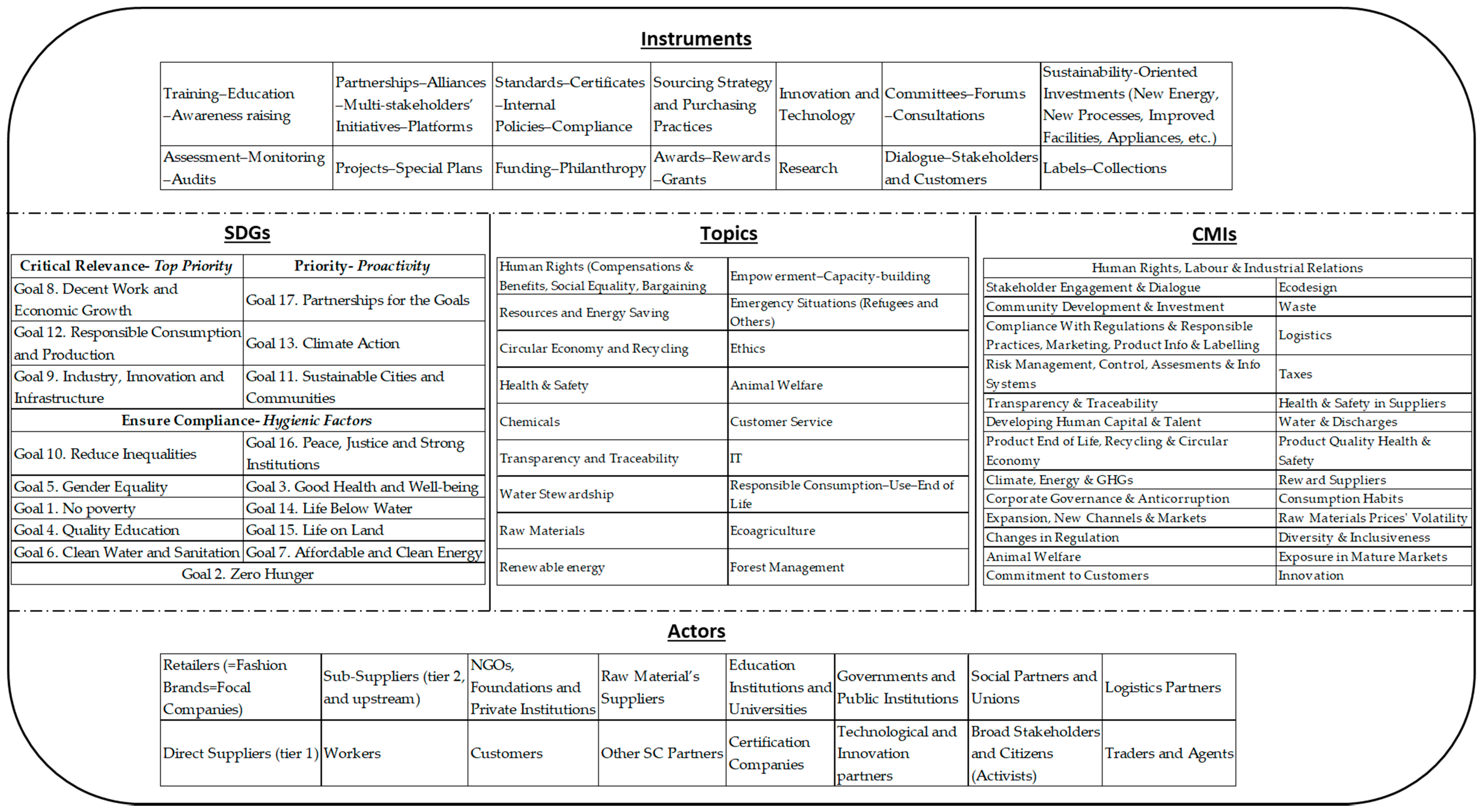

5. Action-Oriented Disclosure Tool Proposal

Objective 2: To propose a universal action-oriented tool for the fast-fashion industry that assists TBL disclosure in creating sustainable value for the whole SC ecosystem.

- The CMIs were complemented with the absent material issues, i.e., those issues not currently being reported, but found to be key for the wider fast-fashion industry ecosystem.

- The RASs were contrasted with the SDGs and the CMIs to ensure that they:

- Targeted the relevant topics.

- Leveraged the most effective instruments.

- The key actors actively involved in the implementation of the RASs were shortlisted in order to identify and push all of the relevant ecosystem actors towards a common goal.

- SDGs: The universal framework containing the broader and widely accepted sustainability goals. The 17 goals are grouped into three levels of urgency (Critical Relevance, Priority, and Ensure Compliance) inspired by previous BSC and SBSC architectures [59,63] according to their relevance to the fast-fashion industry (extracted from our previous analysis; see Table 3). By forcing companies to report on all goals (to at least a minimum compliance level), we avoid the possibility of orphan issues or easy-to-solve problem biases.

- CMIs: The concrete issues already reported by fast-fashion retailers. By disclosing the CMIs in a common framework that relates them to the other categories in the Sustainability Scorecard, we make it difficult for disclosing companies to leave any issue unaddressed and prevent retailers from reporting on accessory issues.

- RAS Topics: The particular questions retailers report that they are already actively tackling. By disclosing these in a common framework and relating them to the other categories in the Sustainability Scorecard, we make it difficult for disclosing companies to act on irrelevant questions and easier for them to compare and team up with peers in the sector.

- RAS Instruments: The strategies, policies, and practices that retailers report that they are already using to cover their RMIs. Publicly disclosing these makes it more difficult for companies to communicate only green-washing practices or other mechanisms that are far from action. Such disclosure also facilitates a sector-wide comparison and analysis to identify the most useful instruments.

- Actors Involved: The players already reported as participating in the execution of the RASs. By shortlisting these actors, we call out all actors in the wider fast-fashion ecosystem and empower relevant partners to pursue a common goal.

6. Discussion and Final Conclusions

- It focusses on immediate solutions and actions, including the topics, instruments (strategies, policies, and practices), and actors needed to deploy them. For example, rather than publishing, with a lapse of one and a half years, the percentage of CO2 reductions coming from stores (impacts), the proposed ‘Fast-Fashion Sustainability Scorecard’ facilitates the identification and exchange of solutions to tackle concerns related to “climate, energy and greenhouse gases (GHG)” (instruments). In this way, we hope to contribute to the need for a “greater emphasis in disclosures related to what apparel brands are doing to find better ways of doing things”, as pointed out by Kozlowski et al. [15] (p. 392).

- It integrates the focal company with other relevant actors in the SC and beyond. For instance, it smoothens the process used to detect and team up with key partners within or outside the SC for each activity or issue to be tackled. This would have a direct contribution to sustainability, as anticipated in the works of Li et al. [26] and Hansen and Schaltegger [63]. In the first study, the authors verified collaborations between suppliers, industries, and NGOs as true enablers of SC sustainability. In the second, Li et al. point out that “collaboration among all stakeholders will normally guarantee an increase in the level of sustainable performance in the global marketplace.” [26] (p. 834).

- In trying to avoid the reporting company being the one that decides “which kind of information to disclose and how to deepen the narrative” [13] (p. 5), our scorecard facilitates the revelation of new information on the gap between sustainability goals and material issues, on one hand, and sustainability actions and instruments, on the other. In other words, it helps to identify orphan material issues so that they can be appropriately addressed. For instance, our analysis reveals a big gap between the potential of innovation in terms of sustainability and the number of actions reported on it. As shown in Figure 4, innovation is revealed as the most material issue in the Fast-Fashion Common Materiality Matrix. However, Table 6 reveals that only 3.54% of the analysed RASs turn to Innovation (under the ‘Innovation and Technology’ instrument) as the instrument for action. This opens up the floor for stakeholders’ demands to focal companies to align their sustainability investments (and disclosure) with the real needs and potential of the broader SC ecosystem. Additionally, following Fritz et al. [64] (p. 600), if the scorecard is pushed by SC actors different from the focal firm, “the risk to report only on good performance aspects would be even better addressed”.

- If retailers allow the scorecard to be interactive, all of the actors related to a particular goal or action can report on and monitor it in almost real-time. As pointed out by Yang et al. [35], fostering SC actors to exchange information would create sustainable value and improve business operations. In this way, the scorecard can also be used to control involuntary disclosure—“what stakeholders and stakeseekers disclose about an organisation” [65] (p. 30)—in two ways. The scorecard can firstly prevent the dissemination of inaccurate or false information from outside a company, and secondly, facilitate an awareness of and reactions to key concerns from other companies and related actors, stakeholders, and stakeseekers. Companies can use our scorecard as a hedging tool against false declarations, and as an opportunity pool for proactively integrating and canalizing external information from stakeholders and stakeseekers.

- It supports the social enforcement, thereby overcoming the critique of lack of normative enforcement that exists in current reporting norms [40]. When reporting on particular and tangible issues that people can understand and see, everyone becomes capable of auditing the degree of execution of an action and claiming responsibility. A simple but clear example is that, although customers might not be able to measure the CO2 in a store, they can report on (and act against) retailers irrationally using the air-conditioning system on shop floors at 15 °C in summer time.

- Finally, our scorecard broadens the grounds for finding best practices, by focussing not on CMIs, but rather on uncovering as many different actions (topics, instruments, and operative actors) as possible. The aim is to compel companies to ‘compete’ in the TBL, thereby adding goals such as ‘I want the best partners for sustainability’ or ‘I want the most comfortable climatisation systems for the workers in the factories’ to already existing goals, such as ‘I want the best IT system’ or ‘I want the highest turnover growth’.

- Businesses and SCs can use the ‘Fast-Fashion Sustainability Scorecard’ to understand and design corporate actions to help alleviate poverty, address climate change, protect human rights, or prevent worker exploitation, thereby encouraging the implementation and commitment of new actions, tools, and actors. UN Global Compact has called for the use of instruments that increase SDG adoption and implementation. The present scorecard addresses this call by aligning CMIs currently reported in fast-fashion with the 17 SDGs, and then examining sustainability-oriented business practices (i.e., real actions in cooperation with SC actors and stakeholders). As described before, our proposed ‘Fast-Fashion Sustainability Scorecard’ aims to transform compliance tools into agents of change [46].

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Shen, B.; Li, Q.; Dong, C.; Perry, P. Sustainability Issues in Textile and Apparel Supply Chains. Sustainability 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gereffi, G.; Korzeniewicz, M. Commodity Chains and Global Capitalism; ABC-CLIO: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 1994; ISBN 0-275-94573-1. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, T.Y.; Dooley, K.J.; Rungtusanatham, M. Supply networks and complex adaptive systems: Control versus emergence. J. Oper. Manag. 2001, 19, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachizawa, E.M.; Wong, C.Y. Towards a theory of multi-tier sustainable supply chains: A systematic literature review. Supply Chain Manag. 2014, 19, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caro, F.; Martínez-de-Albéniz, V. Fast Fashion: Business Model Overview and Research Opportunities. In Retail Supply Chain Management: Quantitative Models and Empirical Studies; Agrawal, N., Smith, A.S., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 237–264. ISBN 978-1-4899-7562-1. [Google Scholar]

- Krause, D.R.; Vachon, S.; Klassen, R.D. Special topic forum on Sustainable Supply Chain Management: Introduction and reflections on the role of purchasing management. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2009, 45, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seuring, S.; Müller, M. From a literature review to a conceptual framework for sustainable supply chain management. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1699–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: Triple Bottom Line 21st Century; Capstone Publishing Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- European Commision. Corporate Social Responsibility: A New Definition, a New Agenda for Action 2011; European Commision: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- European Commision. Next Steps for a Sustainable European Future European Action for Sustainability 2016; European Commision: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ras, P.J.; Vermeulen, W.J.V.; Saalmink, S.L. Greening global product chains: Bridging barriers in the north-south cooperation. An exploratory study of possibilities for improvement in the product chains of table grape and wine connecting South Africa and The Netherlands. Prog. Ind. Ecol. 2007, 4, 401–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, C.L.; Nielsen, A.E.; Valentini, C. CSR research in the apparel industry: A quantitative and qualitative review of existing literature. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truant, E.; Corazza, L.; Scagnelli, S.D. Sustainability and risk disclosure: An exploratory study on sustainability reports. Sustainability 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Integrated Reporting. The International <IR> Framework 2013; The International Integrated Reporting Council: London, UK, 2013; Available online: http://integratedreporting.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/13-12-08-THE-INTERNATIONAL-IR-FRAMEWORK-2-1.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2017).

- Kozlowski, A.; Searcy, C.; Bardecki, M. Corporate sustainability reporting in the apparel industry an analysis of indicators disclosed. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2015, 64, 377–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacchezzini, R.; Melloni, G.; Lai, A. Sustainability management and reporting: The role of integrated reporting for communicating corporate sustainability management. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 136 Pt A, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Kim, S. Sustainable Supply Chain Based on News Articles and Sustainability Reports: Text Mining with Leximancer and DICTION. Sustainability 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelló, I.; Lozano, J.M. Searching for New Forms of Legitimacy through Corporate Responsibility Rhetoric. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 100, 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasche, A. The limits of corporate responsibility standards. Bus. Ethics 2010, 19, 280–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, S.P.; Schepers, D.H. United Nations Global Compact: The Promise-Performance Gap. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 122, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN General Assembly. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; UN General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Arrigo, E. Corporate responsibility management in fast fashion companies: The Gap Inc. case. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2013, 17, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gereffi, G. International trade and industrial upgrading in the apparel commodity chain. J. Int. Econ. 1999, 48, 37–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B. Sustainable fashion supply chain: Lessons from H & M. Sustainability 2014, 6, 6236–6249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, T.-M.; Chiu, C.-H.; Govindan, K.; Yue, X. Sustainable fashion supply chain management: The European scenario. Eur. Manag. J. 2014, 32, 821–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, X.; Shi, D.; Li, X. Governance of sustainable supply chains in the fast fashion industry. Eur. Manag. J. 2014, 32, 823–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, D.; Altuntas, C. Sustainable supply chain management in the fast fashion industry: An analysis of corporate reports. Eur. Manag. J. 2014, 32, 837–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joy, A.; Sherry, J.F., Jr.; Venkatesh, A.; Wang, J.; Chan, R. Fast fashion, sustainability, and the ethical appeal of luxury brands. Fash. Theory 2012, 16, 273–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runfola, A.; Guercini, S. Fast fashion companies coping with internationalization: Driving the change or changing the model? J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2013, 17, 190–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; Li, Q. Impacts of returning unsold products in retail outsourcing fashion supply chain: A sustainability analysis. Sustainability 2015, 7, 1172–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; Ding, X.; Chen, L.; Chan, H.L. Low carbon supply chain with energy consumption constraints: Case studies from China’s textile industry and simple analytical model. Supply Chain Manag. 2017, 22, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L.; Milstein, M.B.; Caggiano, J. Creating sustainable value. Acad. Manag. Exec. 2003, 17, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. Co-creation experiences: The next practice in value creation. J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Creating shared value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Han, H.; Lee, K.P. An Exploratory Study of the Mechanism of Sustainable Value Creation in the Luxury Fashion Industry. Sustainability 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kania, J.; Kramer, M. Collective Impact. Stanf. Soc. Innov. Rev. 2011, 9, 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, M.R.; Pfitzer, M.W. The ecosystem of shared value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2016, 94, 80–89. [Google Scholar]

- Integrated Reporting. Available online: http://www.webcitation.org/6uPaastj9 (accessed on 22 October 2017).

- Global Reporting Initiative. Available online: http://www.webcitation.org/6uPaibAHS (accessed on 22 October 2017).

- Flower, J. The international integrated reporting council: A story of failure. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2015, 27, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumay, J.; Guthrie, J.; Farneti, F. GRI sustainability reporting guidelines for public and third sector organizations: A critical review. Public Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 531–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, L.T.; Morsing, M.; Thyssen, O. CSR as aspirational talk. Organization 2013, 20, 372–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, F.; Castelló, I.; Morsing, M. The construction of corporate social responsibility in network societies: A communication view. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 115, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumay, J. A critical reflection on the future of intellectual capital: From reporting to disclosure. J. Intellect. Cap. 2016, 17, 168–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzer, B. Turning stakeseekers into stakeholders: A political coalition perspective on the politics of stakeholder influence. Bus. Soc. 2008, 47, 50–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, L.T.; Morsing, M.; Thyssen, O. License to Critique: A Communication Perspective on Sustainability Standards. Bus. Ethics Q. 2017, 27, 239–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inditex. Available online: https://www.inditex.com/en/home (accessed on 22 October 2017).

- H&M. Available online: http://www2.hm.com/en_gb/index.html (accessed on 22 October 2017).

- Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). GRI 101: Foundation 2016; GRI: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Seuring, S.; Gold, S. Conducting content-analysis based literature reviews in supply chain management. Supply Chain Manag. 2012, 17, 544–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vourvachis, P.; Woodward, T. Content analysis in social and environmental reporting research: Trends and challenges. J. Appl. Account. Res. 2015, 16, 166–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nvivo. Available online: https://www.qsrinternational.com (accessed on 22 October 2017).

- Bryman, A.; Bell, E. Business Research Methods; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.M.; Strauss, A. Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qual. Sociol. 1990, 13, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, D.A.; Corley, K.G.; Hamilton, A.L. Seeking Qualitative Rigor in Inductive Research: Notes on the Gioia Methodology. Organ. Res. Methods 2013, 16, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J. The digital divide: The special case of gender. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2006, 22, 320–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilbert, M. Digital gender divide or technologically empowered women in developing countries? A typical case of lies, damned lies, and statistics. Women’s Stud. Int. Forum. 2011, 34, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figge, F.; Hahn, T.; Schaltegger, S.; Wagner, M. The Sustainability Balanced Scorecard—Linking sustainability management to business strategy. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2002, 11, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, E.G.; Schaltegger, S. Sustainability Balanced Scorecards and their Architectures: Irrelevant or Misunderstood? J. Bus. Ethics 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.S. Conceptual Foundations of the Balanced Scorecard. In Handbooks of Management Accounting Research; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; Volume 3, ISBN 9780080554501. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, T.; Figge, F. Why Architecture Does Not Matter: On the Fallacy of Sustainability Balanced Scorecards. J. Bus. Ethics 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, E.G.; Schaltegger, S. The Sustainability Balanced Scorecard: A Systematic Review of Architectures. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 133, 193–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, M.M.C.; Schöggl, J.-P.; Baumgartner, R.J. Selected sustainability aspects for supply chain data exchange: Towards a supply chain-wide sustainability assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 141, 587–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumay, J.; Guthrie, J. Involuntary disclosure of intellectual capital: Is it relevant? J. Intellect. Cap. 2017, 18, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köksal, D.; Strähle, J.; Müller, M.; Freise, M. Social sustainable supply chain management in the textile and apparel industry-a literature review. Sustainability 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SDGs | |

|---|---|

| Risks: Avoid Practices and Policies | Opportunities: Enhance These Practices and Policies |

| SDG1 No Poverty: avoid those practices and policies that foster extreme poverty, and avoid inequality and labour exploitation | SDG1 No Poverty: enhance practices and policies that create shared value with workers and suppliers, help to create equal labour practices in particular to poor and vulnerable workers, and foster equal rights to economic resources and access to basic services |

| SDG2 Zero Hunger: avoid practices and policies that foster all forms of malnutrition | SDG2 Zero Hunger: enhance practices and policies that end hunger and ensure access to safe, nutritious, and sufficient food to workers in vulnerable situations, including company workers and the company’s supply chain |

| SDG3 Good Health and Well-being: avoid practices and policies that foster death and mortality among the company workers and across the company’s supply chain | SDG3 Good Health and Well-being: enhance labour practices and policies that improve well-being and prevent death and mortality to the company’s workers and across the company’s supply chain. Reduce diseases, injuries, and accidents. |

| SDG4 Quality Education: avoid practices and policies that foster lack of education among the company workers and across the company’s supply chain | SDG4 Quality Education: enhance practices and policies that ensure primary and secondary education to the company’s workers and across the company’s value chain, improving workers’ skills and capabilities. Ensure equal access for all women and men to inclusive equitable quality and affordable technical, vocational, and tertiary education to their workers, promoting lifelong learning opportunities for them |

| SDG5: Gender Equality: avoid labour practices and policies that foster all forms of discrimination against women that work at the company or across the company’s supply chain | SDG5 Gender Equality: enhance labour practices and policies that eliminate all forms of violence against women and girls, ensure women equal rights to economic resources, and promote equal and inclusive labour opportunities across the company’s workers and across the company’s value chain |

| SDG6 Clean Water and Sanitation: avoid practices and policies that foster pollution on clean water and do not foster sanitation for all | SDG6 Clean Water and Sanitation: enhance practices and policies that ensure the availability and use of clean water and sanitation |

| SDG7 Affordable and Clean Energy: avoid practices and policies that foster the use of non-renewable energy | SDG7 Affordable and Clean Energy: enhance practices and policies that ensure access to affordable, reliable, renewable, and modern energy |

| SDG8 Decent Work and Economic Growth: avoid labour practices and policies that foster indecent work practices to company workers and across the company’s supply chain | SDG8 Decent Work and Economic Growth: enhance practices and policies that promote sustained, inclusive, and sustainable economic growth, full productive employment, and decent work across the company’s workers and across the company’s supply chain |

| SDG9 Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure: avoid practices and policies that foster non-sustainable industrialization and lack of innovation | SDG9 Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure: enhance practices and policies that build resilient infrastructure and promote inclusive and sustainable industrialisation and innovation |

| SDG10 Reduce Inequalities: avoid practices and policies that increase inequality within and among countries | SDG10 Reduce inequalities: enhance practices and policies that reduce inequality within and among countries |

| SDG11 Sustainable Cities and Communities: avoid practices and policies that generate lack of access to affordable housing and basic services | SDG11 Sustainable Cities and Communities: enhance practices and policies that generate access to affordable housing |

| SDG12 Responsible Consumption and Production: avoid practices and policies that foster the inefficient use and scarcity of natural resources and generate environmental impacts | SDG12 Responsible Consumption and Production: enhance practices and policies that foster the efficient and long-term sustainable use of natural resources and reduce negative environmental impacts |

| SDG13 Climate Action: avoid practices and policies that increases climate change | SDG13 Climate Action: enhance practices and policies that reduce climate change |

| SDG14 Life below Water: avoid practices and policies that generate marine pollution and destroy marine and water ecosystems | SDG14 Life Below Water: enhance practices and policies that foster the conservation and sustainable use of the oceans, seas, marine resources, and water ecosystems |

| SDG15 Life on Land: avoid practices and policies that generate the unsustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems and generate biodiversity loss | SDG15 Life on Land: enhance practices and policies that foster the sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, improve biodiversity, and combat desertification |

| SDG16 Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions: avoid practices and policies that generate conflict, violence, abuse, and exploitation against workers and children | SDG16 Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions: enhance practices and policies that promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development and provide access to justice for workers and children |

| SDG17 Partnership for the Goals: avoid unilateral practices and policies that do not foster UN SDGs | SDG17 Partnership for the Goals: foster collaborative and multi-stakeholder practices and policies to strengthen the means of implementation of UN SDGs |

| Common Material Issues (CMIs) | Shared by the Two Retailers |

|---|---|

| Animal Welfare | Yes |

| Climate, Energy, and Greenhouse Gases (GHGs) | Yes |

| Commitment to Customers | Yes |

| Community Development and Investment | Yes |

| Compliance with Regulations and Responsible Practices, Marketing, Product Info and Labelling | Yes |

| Corporate Governance and Anticorruption | Yes |

| Developing Human Capital and Talent | Yes |

| Ecodesign | Yes |

| Health and Safety in Suppliers | Yes |

| Human Rights, Labour, and Industrial Relations | Yes |

| Product End of Life, Recycling, and Circular Economy | Yes |

| Risk Management, Control, Assessments, and Information Systems | Yes |

| Transparency and Traceability | Yes |

| Waste | Yes |

| Water and Discharges | Yes |

| Changes in Regulation | No |

| Consumption Habits | No |

| Diversity and Inclusiveness | No |

| Expansion, New Channels, and Markets | No |

| Exposure in Mature Markets | No |

| Innovation | No |

| Logistics | No |

| Product Quality Health and Safety | No |

| Raw Material Price Volatility | No |

| Reward Suppliers | No |

| Stakeholder Engagement, and Dialogue | No |

| Taxes | No |

| Total CMIs: 27 | % of CMIs: 56% |

| Common Material Issues (CMIs) | Final Score | SDGs Potentially Impacted |

|---|---|---|

| Animal welfare | 4.25 | 17.65% |

| Changes in regulation | 3.5 | 20.59% |

| Climate, energy, and GHGs | 4.25 | 23.53% |

| Commitment to customers | 5 | 17.65% |

| Community development and investment | 4.25 | 47.06% |

| Compliance with regulations, responsible practices, marketing, product information, and labelling | 4.25 | 44.12% |

| Consumption habits | 5 | 5.88% |

| Corporate governance and anticorruption | 3.5 | 25.00% |

| Developing human capital and talent | 5 | 29.41% |

| Diversity and inclusiveness | 3.5 | 2.94% |

| Ecodesign | 4.25 | 19.12% |

| Expansion; new channels and markets | 3.5 | 23.53% |

| Exposure in mature markets | 2 | 2.94% |

| Health and safety in suppliers | 5 | 11.76% |

| Human rights, labour, and industrial relations | 5 | 52.94% |

| Innovation | 5 | 61.76% |

| Logistics | 5 | 14.71% |

| Product end of life, recycling, and circular economy | 4.25 | 29.41% |

| Product quality health and safety | 5 | 10.29% |

| Raw material price volatility | 2 | 5.88% |

| Reward suppliers | 5 | 8.82% |

| Risk management, control, assessments, and information systems | 5 | 41.18% |

| Stakeholder engagement and dialogue | 3.5 | 52.94% |

| Tax | 3.5 | 14.71% |

| Transparency and traceability | 4.625 | 41.18% |

| Waste | 3.5 | 16.18% |

| Water and discharges | 5 | 13.24% |

| Total Topics: 27 |

| UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) | Shared by the Two Retailers | Connected to CMIs as Risks, Opportunities, or Both | Coded as | Total Frequency | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk | Opportunity | ||||

| Goal 1. No Poverty | Yes | Opportunity | 0.00% | 3.30% | 3.30% |

| Goal 2. Zero Hunger | No | Both | 0.55% | 0.55% | 1.10% |

| Goal 3. Good Health and Well-being | No | Both | 0.55% | 2.20% | 2.75% |

| Goal 4. Quality Education | No | Opportunity | 0.00% | 3.30% | 3.30% |

| Goal 5. Gender Equality | Yes | Both | 0.55% | 3.30% | 3.85% |

| Goal 6. Clean Water and Sanitation | Yes | Both | 2.75% | 0.55% | 3.30% |

| Goal 7. Affordable and Clean Energy | Yes | Both | 0.55% | 1.10% | 1.65% |

| Goal 8. Decent Work and Economic Growth | Yes | Both | 8.24% | 11.54% | 19.78% |

| Goal 9. Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure | Yes | Both | 4.40% | 9.34% | 13.74% |

| Goal 10. Reduce Inequalities | Yes | Opportunity | 0.00% | 4.40% | 4.40% |

| Goal 11. Sustainable Cities and Communities | Yes | Both | 1.65% | 4.40% | 6.04% |

| Goal 12. Responsible Consumption and Production | Yes | Both | 1.10% | 13.19% | 14.29% |

| Goal 13. Climate Action | Yes | Both | 2.75% | 4.40% | 7.14% |

| Goal 14. Life Below Water | Yes | Both | 1.65% | 0.55% | 2.20% |

| Goal 15. Life on Land | Yes | Both | 1.65% | 0.55% | 2.20% |

| Goal 16. Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions | Yes | Both | 1.10% | 2.20% | 3.30% |

| Goal 17. Partnerships for the Goals | Yes | Both | 0.55% | 7.14% | 7.69% |

| % Appearing in Both Materiality Matrices | 82% | ||||

| % Appearing in at Least One Materiality Matrix | 100.00% | ||||

| Total Risks vs. Opportunities | 28% | 72% | |||

| Topics | Instruments | Actors |

|---|---|---|

| Human Rights (Compensations and Benefits, Social Equality, Bargaining Power, etc.) | Training–Education–Awareness raising | Retailers (=fashion brand = focal company) |

| Resources and Energy Saving | Assessment–Monitoring–Audits | Direct Suppliers (tier 1) |

| Circular Economy and Recycling | Partnerships–Alliances–Multi-stakeholders’ Initiatives–Platforms | Sub-suppliers (tier 2, and upstream) |

| Health and Safety | Projects–Special Plans | Workers |

| Chemicals | Standards–Certificates–Internal Policies–Compliance | Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs), Foundations, and Private Institutions |

| Transparency, Traceability | Funding–Philanthropy | Customers |

| Water Stewardship | Sourcing Strategy and Purchasing Practices | Raw Material Suppliers |

| Raw Materials | Awards–Rewards–Grants | Other Supply Chain (SC) Partners |

| Renewable energy | Innovation and Technology | Education Institutions, Universities |

| Empowerment, Capacity Building | Research | Certification Companies |

| Emergency Situations (Refugees and Others) | Committees–Forums–Consultations | Governments and Public Institutions |

| Ethics | Dialogue–Stakeholders and Customers | Technological and Innovation Partners |

| Animal Welfare | Sustainability-Oriented Investments (New Energy, New Processes, Improved Facilities, Appliances, etc.) | Social Partners and Unions |

| Costumer Service | Labels–Collections | Broad Stakeholders and Citizens (Activists) |

| IT | Logistics Partners | |

| Responsible Consumption–Use–End of Life | Traders, Agents | |

| Ecoagriculture | ||

| Forest Management | ||

| Total Topics: 18 | Total Instruments: 14 | Total Actors: 16 |

| Topics | Shared by the Two Retailers | Total Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Human Rights (Compensations and Benefits, Social Equality, Bargaining Power, etc.) | Yes | 35.35% |

| Resources and Energy Saving | Yes | 10.61% |

| Circular Economy and Recycling | Yes | 10.10% |

| Health and Safety | Yes | 7.58% |

| Chemicals | Yes | 6.06% |

| Transparency and Traceability | Yes | 6.06% |

| Water Stewardship | Yes | 6.06% |

| Raw Materials | Yes | 5.56% |

| Renewable energy | Yes | 3.54% |

| Empowerment, Capacity Building | Yes | 3.03% |

| Emergency Situations (Refugees and Others) | Yes | 2.02% |

| Ethics | Yes | 1.52% |

| Animal Welfare | No | 1.01% |

| Customer Service | No | 1.01% |

| IT | Yes | 1.01% |

| Responsible Consumption–Use–End of Life | No | 1.01% |

| Ecoagriculture | No | 0.51% |

| Forest Management | No | 0.51% |

| Total Topics: 18 | Total Topics Shared: 72% | 198 Actions |

| Instruments | Shared by the Two Retailers | Total Frequency |

| Training–Education–Awareness-raising | Yes | 27.78% |

| Assessment–Monitoring–Audits | Yes | 17.17% |

| Partnerships–Alliances–Multi-stakeholders’ Initiatives–Platforms | Yes | 14.65% |

| Projects–Special Plans | Yes | 13.13% |

| Standards–Certificates–Internal Policies–Compliance | Yes | 13.13% |

| Funding–Philanthropy | Yes | 8.59% |

| Sourcing Strategy and Purchasing Practices | Yes | 5.05% |

| Awards–Rewards–Grants | Yes | 3.54% |

| Innovation and Technology | Yes | 3.54% |

| Research | Yes | 3.54% |

| Committees–Forums–Consultations | Yes | 2.53% |

| Dialogue–Stakeholders and Customers | Yes | 2.53% |

| Sustainability-Oriented Investments (New Energy, New Processes, Improved Facilities, Appliances, etc.) | Yes | 2.53% |

| Labels–Collections | Yes | 1.52% |

| Total Instruments: 14 | Total Topics Shared: 100% | 198 Actions |

| Actors | Shared by the Two Retailers | Total Frequency |

| Retailers (=fashion brand = focal company) | Yes | 100.00% |

| Direct Suppliers (tier 1) | Yes | 25.25% |

| Sub-suppliers (tier 2, and upstream) | Yes | 18.69% |

| Workers | Yes | 17.17% |

| NGOs, Foundations, and Private Institutions | Yes | 15.66% |

| Customers | Yes | 10.10% |

| Raw Material Suppliers | Yes | 8.59% |

| Other SC Partners | Yes | 8.08% |

| Education Institutions–Universities | Yes | 6.06% |

| Certifications Companies | Yes | 5.05% |

| Governments and Public Institutions | Yes | 4.04% |

| Technological and Innovation Partners | Yes | 3.54% |

| Social Partners and Unions | Yes | 3.03% |

| Broad Stakeholders and Citizens (Activists) | Yes | 2.02% |

| Logistic Partners | No | 1.52% |

| Traders–Agents | No | 0.51% |

| Total Actors: 16 | Total Actors Shared: 87.5% | 198 Actions |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Garcia-Torres, S.; Rey-Garcia, M.; Albareda-Vivo, L. Effective Disclosure in the Fast-Fashion Industry: from Sustainability Reporting to Action. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2256. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9122256

Garcia-Torres S, Rey-Garcia M, Albareda-Vivo L. Effective Disclosure in the Fast-Fashion Industry: from Sustainability Reporting to Action. Sustainability. 2017; 9(12):2256. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9122256

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcia-Torres, Sofia, Marta Rey-Garcia, and Laura Albareda-Vivo. 2017. "Effective Disclosure in the Fast-Fashion Industry: from Sustainability Reporting to Action" Sustainability 9, no. 12: 2256. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9122256

APA StyleGarcia-Torres, S., Rey-Garcia, M., & Albareda-Vivo, L. (2017). Effective Disclosure in the Fast-Fashion Industry: from Sustainability Reporting to Action. Sustainability, 9(12), 2256. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9122256