Reputation, Game Theory and Entrepreneurial Sustainability

Abstract

:1. Introduction

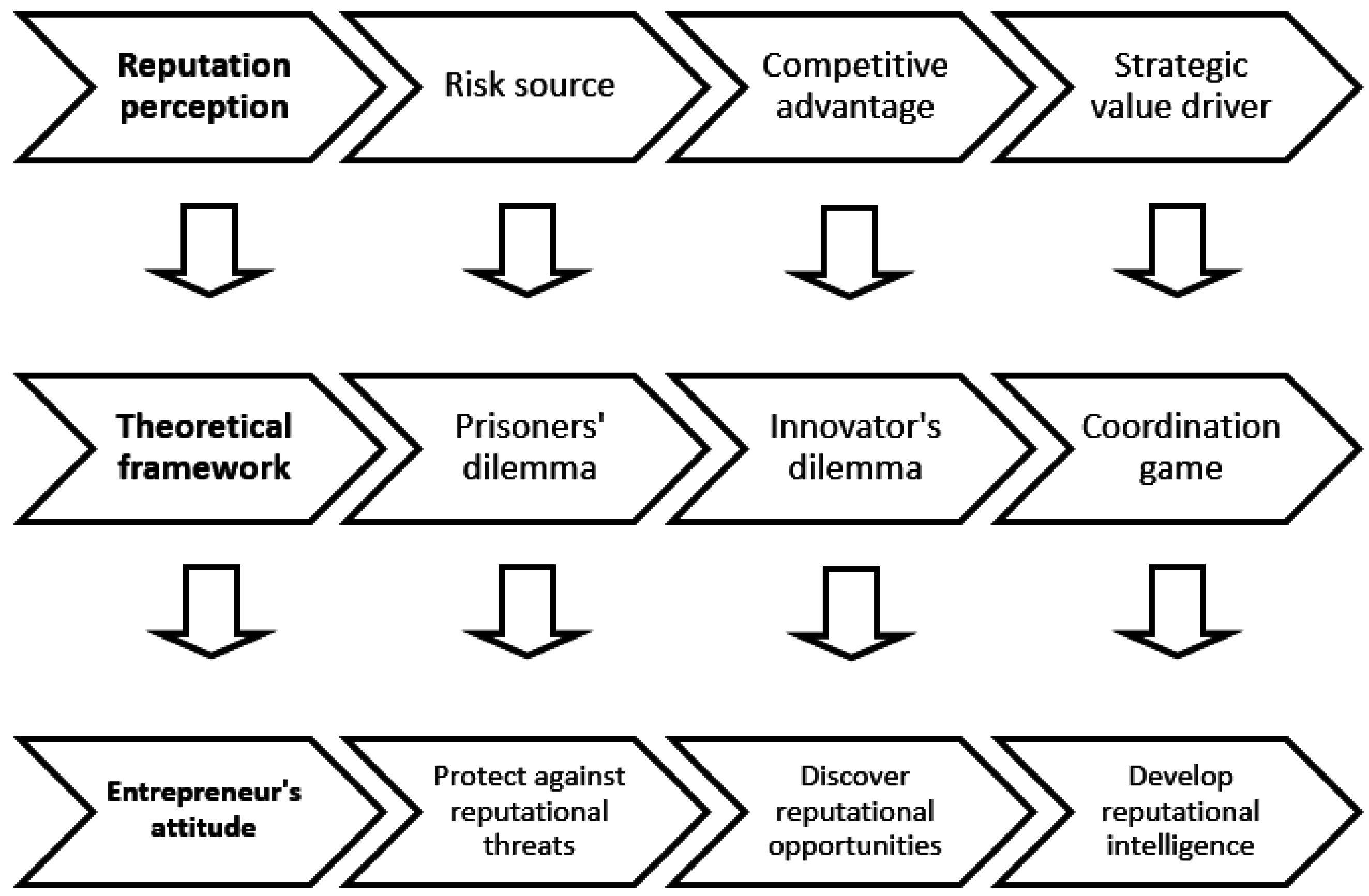

2. Reputation as a Risk Source

3. Reputation as a Competitive Advantage

4. Reputational Thinking as the Micro-Foundation of Reputational Intelligence

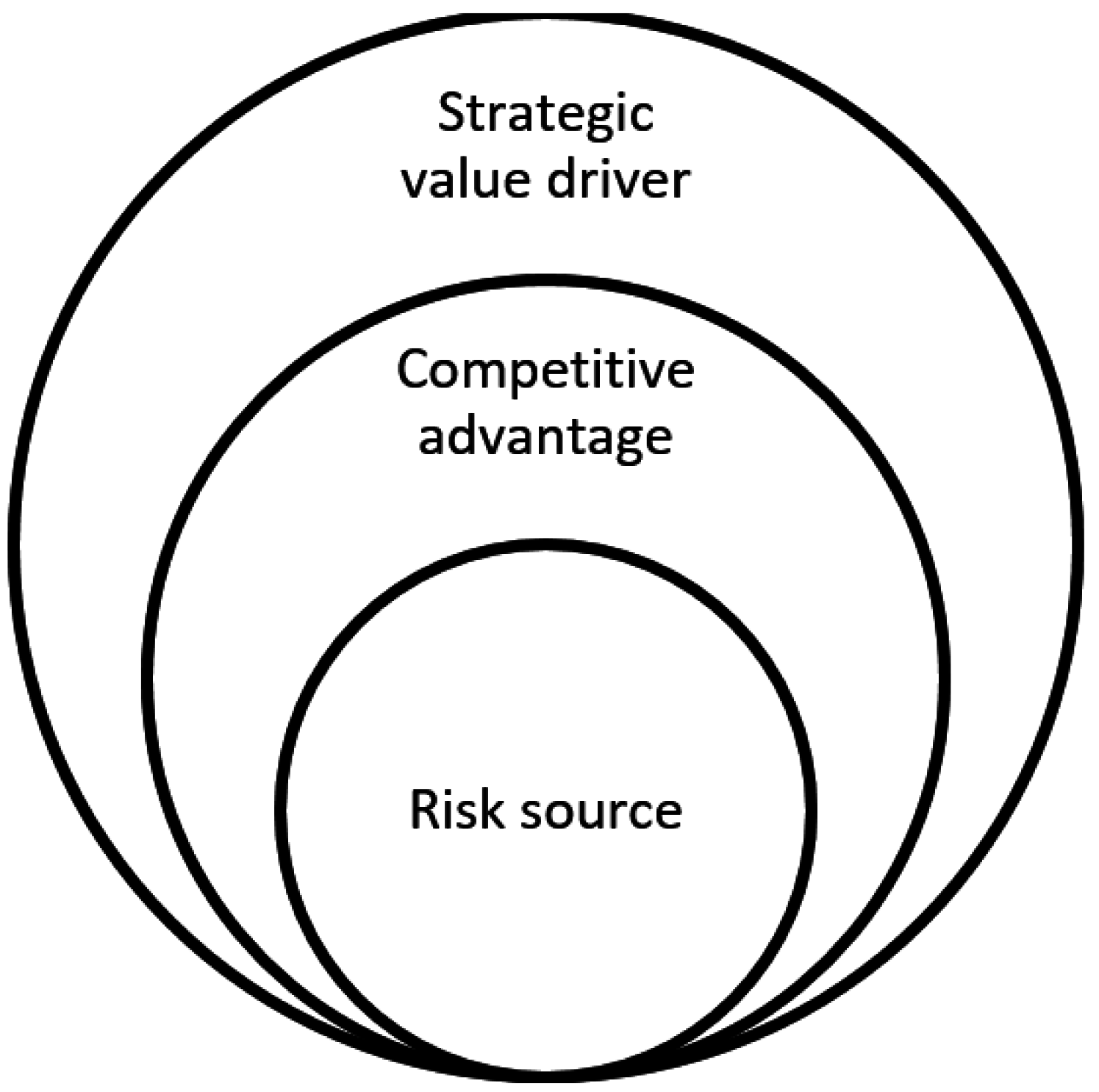

5. Integration of the Three Dimensions of Reputation

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arjoon, S. Corporate governance: An ethical perspective. J. Bus. Eth. 2005, 61, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Perez, M.; Leonard, L. International Business, Sustainability and Corporate Social Responsibility; Emerald Group Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bachev, H. Risk Management in the Agri-food Sector. Contemp. Econ. 2013, 7, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetty, S.; Naidoo, R.; Seetharam, Y. The impact of corporate social responsibility on firms’ financial performance in South Africa. Contemp. Econ. 2015, 9, 193–214. [Google Scholar]

- Surroca, J.; Tribó, J.A.; Waddock, S. Corporate responsibility and financial performance: The role of intangible resources. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 463–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, A.K.; Lai, K.; Cheng, T. Environmental governance of enterprises and their economic upshot through corporate reputation and customer satisfaction. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2012, 21, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.H.; Guidry, R.P.; Hageman, A.M.; Patten, D.M. Do actions speak louder than words? An empirical investigation of corporate environmental reputation. Account. Organ. Soc. 2012, 37, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comeig, I.; Holt, C.A.; Jaramillo-Gutiérrez, A. Dealing with Risk: Gender, Stakes, and Probability Effects; University of Valencia, ERI-CES: Valencia, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chorafas, D.N. The Management of Equity Investments; Butterworth-Heinemann: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rayner, J. Managing Reputational Risk: Curbing Threats, Leveraging Opportunities; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, C.A. A commentary on: Corporate social responsibility reporting and reputation risk management. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2008, 21, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebbington, J.; Larrinaga, C.; Moneva, J.M. Corporate social reporting and reputation risk management. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2008, 21, 337–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forstmoser, P.; Herger, N. Managing reputational risk: A reinsurer’s view. Geneva Pap. Risk Insur.-Issues Pract. 2006, 31, 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, J.; Lodhia, S. Sustainability reporting and reputation risk management: An Australian case study. Int. J. Account. Inform. Manag. 2011, 19, 267–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineiro-Chousa, J.; Vizcaíno-González, M.; Romero-Castro, N. Recent Advances in Standardizing the Reporting of Nonfinancial Information. In Organizational Change and Global Standardization: Solutions to Standards and Norms Overwhelming Organizations; Boje, D.M., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 169–185. [Google Scholar]

- Plunus, S.; Gillet, R.; Hübner, G. Reputational damage of operational loss on the bond market: Evidence from the financial industry. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2012, 24, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiordelisi, F.; Soana, M.; Schwizer, P. The determinants of reputational risk in the banking sector. J. Bank. Financ. 2013, 37, 1359–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palm, S. Why Reputational Risk Is on the Rise. Am. Bank. 2012, 177, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Csiszar, E.; Heidrich, G.W. The question of reputational risk: Perspectives from an industry. Geneva Pap. Risk Insur. Issues Pract. 2006, 31, 382–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schanz, K. Reputation and reputational risk management. Geneva Pap. Risk Insur. Issues Pract. 2006, 31, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, M.; Scheytt, T.; Soin, K.; Sahlin, K. Reputational risk as a logic of organizing in late modernity. Organ. Stud. 2009, 30, 301–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binkhorst, J.; Kingma, S.F. Safety vs. reputation: Risk controversies in emerging policy networks regarding school safety in the Netherlands. J. Risk Res. 2012, 15, 913–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckertz, A.; Wagner, M. The influence of sustainability orientation on entrepreneurial intentions—Investigating the role of business experience. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 524–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D.A.; Patzelt, H. The new field of sustainable entrepreneurship: Studying entrepreneurial action linking “what is to be sustained” with “what is to be developed”. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 137–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tregidga, H.; Milne, M.; Kearins, K. (Re)presenting ‘sustainable organizations’. Account. Organ. Soc. 2014, 39, 477–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkurinen, P.; Ketola, T. Corporate responsibility and identity: From a stakeholder to an awareness approach. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2012, 21, 326–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkurinen, P. Strategic corporate responsibility: A theory review and reconsideration of the conventional perspective. In Proceedings of the EGOS Conference, Helsinki, Finland, 5–7 June 2012.

- Gray, P.H.; Cooper, W.H. Pursuing failure. Organ. Res. Methods 2010, 13, 620–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragon-Correa, J.A. Beyond ourselves: Building bridges to generate real progress on sustainability management issues. Organ. Environ. 2013, 26, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, L.; Jackson, S.E.; Russell, S.V. Greening organizational behavior: An introduction to the special issue. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, G.F. Do theories of organizations progress? Organ. Res. Methods 2010, 13, 690–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, D. Risk management-Protecting reputation: Reputation risk management-The holistic approach. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2002, 18, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, E.M.; Hughes, J.F.; Glaister, K.W. Linking ethics and risk management in taxation: Evidence from an exploratory study in Ireland and the UK. J. Bus. Eth. 2009, 86, 177–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, J. Strategic Reputation Risk Management; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Zaman, A. Reputational Risk; Prentice-Hall/Pearson Education: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Atkins, D.; Drennan, L.; Bates, I. Reputational Risk: A Question of Trust; Global Professional Publishing: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cornescu, V.; Druică, E.; Bratu, A. An Overview on the Reputation Risk. In Proceedings of the 16th International Economic Conference Industrial Revolutions, from the Globalization and Post-Globalization Perspective, Sibiu, Romania, 7–8 May 2009; pp. 61–66.

- Weitzner, D.; Darroch, J. The limits of strategic rationality: Ethics, enterprise risk management, and governance. J. Bus. Eth. 2010, 92, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, W.; Guiral, A.; Gonzalo, J.A. Different pathways that suggest whether auditors’ going concern opinions are ethically based. J. Bus. Eth. 2009, 86, 347–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeller, M.; Harvey, M. Inpatriate marketing managers: Issues associated with staffing global marketing positions. J. Int. Mark. 2011, 19, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, R. Toward a better understanding of organizational efforts to rebuild reputation following an ethical scandal. J. Bus. Eth. 2009, 90, 453–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantelica, C. Business Ethics, A Pillar Of Corporate Reputation. Amfiteatru Econ. J. 2008, 10, 118–124. [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly, R.; Clement, J.; Le Heron, R.; St George, J. Redesigning risk frameworks and registers to support the assessment and communication of risk in the corporate context: Lessons from a corporate risk manager in action. Risk Manag. 2012, 14, 222–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waygood, S. Capital Market Campaigning: The Impact of NGOs on Companies, Shareholder Value and Reputational Risk; Risk Books: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Regan, L. A framework for integrating reputation risk into the enterprise risk management process. J. Financ. Transform. 2008, 22, 187–194. [Google Scholar]

- Lenz, H.; Ostrowski, M. Auditor choice by IPO firms in Germany: Information or insurance signalling? Int. J. Account. Audit. Perform. Eval. 2005, 2, 300–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linsley, P.; Kajuter, P. Restoring reputation and repairing legitimacy: A case study of impression management in response to a major risk event at Allied Irish Banks plc. Int. J. Financ. Serv. Manag. 2008, 3, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingales, L. In search of new foundations. J. Financ. 2000, 55, 1623–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y. Stakeholder welfare and firm value. J. Bank. Financ. 2010, 34, 2549–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizcaíno, M.; Chousa, J.P. Analyzing the influence of the funds’ support on Tobin’s q using SEM and fsQCA. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2118–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagano, M.; Volpin, P.F. Managers, workers, and corporate control. J. Financ. 2005, 60, 841–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronqvist, H.; Heyman, F.; Nilsson, M.; Svaleryd, H.; Vlachos, J. Do entrenched managers pay their workers more? J. Financ. 2009, 64, 309–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Neumann, J.; Morgenstern, O. Theory of Games and Economic Behaviour; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, W.H. Marxism, business ethics, and corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Eth. 2009, 84, 565–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopel, M.; Brand, B. Socially responsible firms and endogenous choice of strategic incentives. Econ. Model 2012, 29, 982–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambertini, L.; Tampieri, A. Corporate Social Responsibility and Firms Ability to Collude. In Board Directors and Corporate Social Responsibility; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Klempner, G. Ethics and Advertising. 2004. Available online: http://klempner.freeshell.org/articles/advertising.html (accessed on 16 November 2016).

- Sacconi, L. A social contract account for CSR as an extended model of corporate governance (I): Rational bargaining and justification. J. Bus. Eth. 2006, 68, 259–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacconi, L. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) as a Model of ‘Extended’ Corporate Governance: An Explanation Based on the Economic Theories of Social Contract, Reputation and Reciprocal Conformism. LIUC Ethics Law and Economic Paper. 2004. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=514522 (accessed on 16 November 2016).

- Harrington, J. Games, Strategies and Decision Making; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tadelis, S. Game Theory: An Introduction; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Creating shared value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Bower, J.L.; Christensen, C.M. Disruptive Technologies: Catching the Wave; Harvard Business Review: Boston, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, C.M.; Raynor, M.E. The Innovator’s Solution: Creating and Sustaining Successful Growth; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, C.M.; Baumann, H.; Ruggles, R.; Sadtler, T.M. Disruptive innovation for social change. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 94. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Christopher, M.; Gaudenzi, B. Exploiting knowledge across networks through reputation management. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2009, 38, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelo Branco, M.; Lima Rodrigues, L. Corporate social responsibility and resource-based perspectives. J. Bus. Eth. 2006, 69, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boje, D.M.; Rosile, G.A.; Durant, R.A.; Luhman, J.T. Enron spectacles: A critical dramaturgical analysis. Organ. Stud. 2004, 25, 751–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J.L.; Ponsaing, C.D.; Thrane, S. Risk, resources and structures: Experimental evidence of a new cost of risk component—The structural risk component and implications for enterprise risk management. Risk Manag. 2012, 14, 152–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glückler, J.; Armbrüster, T. Bridging uncertainty in management consulting: The mechanisms of trust and networked reputation. Organ. Stud. 2003, 24, 269–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, R.; Inkpen, A.C. Understanding institutional-based trust building processes in inter-organizational relationships. Organ. Stud. 2011, 32, 281–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebb, T.; Hamilton, A.; Hachigian, H. Responsible Property Investing in Canada: Factoring Both Environmental and Social Impacts in the Canadian Real Estate Market. J. Bus. Eth. 2010, 92, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, B.J. Keeping ethical investment ethical: Regulatory issues for investing for sustainability. J. Bus. Eth. 2009, 87, 555–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, S. Supply chain specific? Understanding the patchy success of ethical sourcing initiatives. J. Bus. Eth. 2003, 44, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, T.J.; Roth, M.S.; Dillon, W.R. Global product quality and corporate social responsibility perceptions: A cross-national study of halo effects. J. Int. Mark. 2012, 20, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyles, J.; Fried, J. ‘Technical breaches’ and ‘eroding margins of safety’—Rhetoric and reality of the nuclear industry in Canada. Risk Manag. 2012, 14, 126–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaultier-Gaillard, S.; Louisot, J.; Rayner, J. Managing Reputational Risk—From Theory to Practice. In Reputation Capital; Klewes, J., Wreschniok, R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2009; pp. 161–178. [Google Scholar]

- Coldwell, D.; Joosub, T.; Papageorgiou, E. Responsible Leadership in Organizational Crises: An Analysis of the Effects of Public Perceptions of Selected SA Business Organizations’ Reputations. J. Bus. Eth. 2012, 109, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaultier-Gaillard, S.; Louisot, J. Risks to reputation: A global approach. Geneva Pap. Risk Insur. Issues Pract. 2006, 31, 425–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanaland, A.J.; Lwin, M.O.; Murphy, P.E. Consumer perceptions of the antecedents and consequences of corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Eth. 2011, 102, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombrun, C.J.; Gardner, N.A.; Barnett, M.L. Opportunity Platforms and Safety Nets: Corporate Citizenship and Reputational Risk. Bus. Soc. Rev. 2000, 105, 85–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigue, M.; Magnan, M.; Cho, C.H. Is Environmental Governance Substantive or Symbolic? An Empirical Investigation. J. Bus. Eth. 2013, 114, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balch, D.R.; Armstrong, R.W. Ethical Marginality: The Icarus Syndrome and Banality of Wrongdoing. J. Bus. Eth. 2010, 92, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festinger, L. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Fontanari, J.F.; Bonniot-Cabanac, M.; Cabanac, M.; Perlovsky, L.I. A structural model of emotions of cognitive dissonances. Neural Netw. 2012, 32, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahgal, A.; Elfering, A. Relevance of cognitive dissonance, activation and involvement to branding: An overview. Escr. Psicol. 2011, 4, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawronski, B. Back to the future of dissonance theory: Cognitive consistency as a core motive. Soc. Cognit. 2012, 30, 652–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavris, C.; Aronson, E. Mistakes Were Made (but Not by Me): Why We Justify Foolish Beliefs, Bad Decisions, and Hurtful Acts; Harvest Books: Orlando, FL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lowell, J. Managers and Moral Dissonance: Self Justification as a Big Threat to Ethical Management? J. Bus. Eth. 2012, 105, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champagne, F.A.; Francis, D.D.; Mar, A.; Meaney, M.J. Variations in maternal care in the rat as mediating influence for the effects of environment on development. Physiol. Behav. 2003, 79, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, A. Early experiences change DNA and thus gene expression. Psychiatric News, 6 June 2009; 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, I.C.; Cervoni, N.; Champagne, F.A.; D’Alessio, A.C.; Sharma, S.; Seckl, J.R.; Dymov, S.; Szyf, M.; Meaney, M.J. Epigenetic programming by maternal behaviour. Nat. Neurosci. 2004, 7, 847–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, D.; Diorio, J.; Liu, D.; Meaney, M.J. Nongenomic transmission across generations of maternal behaviour and stress responses in the rat. Science 1999, 286, 1155–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meaney, M.J. Epigenetics and the biological definition of gene× environment interactions. Child Dev. 2010, 81, 41–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suderman, M.; McGowan, P.O.; Sasaki, A.; Huang, T.C.; Hallet, M.T.; Meaney, M.J.; Turecki, G.; Szyf, M. Conserved epigenetic sensitivity to early life experience in the rat and human hippocampus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 17266–17272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hensch, T. Controlling the critical period. Neurosci. Res. 2003, 47, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölzel, B.K.; Carmody, J.; Vangel, M.; Congleton, C.; Yerramsetti, S.M.; Gard, T.; Lazar, S.W. Mindfulness practice leads to increases in regional brain gray matter density. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 2011, 191, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Draganski, B.; Gaser, C.; Busch, V.; Schuierer, G.; Bogdahn, U.; May, A. Neuroplasticity: Changes in grey matter induced by training. Nature 2004, 427, 311–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, R.J.; McEwen, B.S. Social influences on neuroplasticity: Stress and interventions to promote well-being. Nat. Neurosci. 2012, 15, 689–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khazanchi, S.; Masterson, S.S. Who and what is fair matters: A multi-foci social exchange model of creativity. J. Organ. Behav. 2011, 32, 86–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagi, Y.; Tavor, I.; Hofstetter, S.; Tzur-Moryosef, S.; Blumenfeld-Katzir, T.; Assaf, Y. Learning in the fast lane: New insights into neuroplasticity. Neuron 2012, 73, 1195–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iacoboni, M.; Mazziotta, J.C. Mirror neuron system: Basic findings and clinical applications. Ann. Neurol. 2007, 62, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keysers, C.; Gazzola, V. Social neuroscience: Mirror neurons recorded in humans. Curr. Biol. 2010, 20, R353–R354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liew, S.; Aziz-Zadeh, L. The Human Mirror Neuron System, Social Control, and Language. In Handbook of Neurosociology; Franks, D.D., Turner, J.H., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 183–205. [Google Scholar]

- Bernhardt, B.C.; Singer, T. The neural basis of empathy. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2012, 35, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, T. The neuronal basis and ontogeny of empathy and mind reading: Review of literature and implications for future research. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2006, 30, 855–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, T.; Lamm, C. The social neuroscience of empathy. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2009, 1156, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iacoboni, M.; Woods, R.P.; Brass, M.; Bekkering, H.; Mazziotta, J.C.; Rizzolatti, G. Cortical mechanisms of human imitation. Science 1999, 286, 2526–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerrans, P.S. Imitation, mind reading, and social learning. Biol. Theory 2013, 8, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, L.J.; Mackey, A.; Whetten, D. Taking responsibility for corporate social responsibility: The role of leaders in creating, implementing, sustaining, or avoiding socially responsible firm behaviors. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2014, 28, 164–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.L.; Barling, J. Greening organizations through leaders’ influence on employees’ pro-environmental behaviors. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 176–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, D.A.; Adolphs, R. Toward a neural basis for social behavior. Neuron 2013, 80, 816–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, G.J.; Hawkley, L.C.; Cole, S.W.; Berntson, G.G.; Cacioppo, J.T. Social neuroscience: The social brain, oxytocin, and health. Soc. Neurosci. 2012, 7, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson-Cramer, M.; Berman, S.; Post, J. Re-examining the Concept of ‘Stakeholder Management’. In Unfolding Stakeholder Thinking: Relationships, Communication, Reporting and Performance; Andriof, J., Waddock, S., Husted, B., Rahman, S., Eds.; Greenleaf Publishing: Sheffield, UK, 2003; pp. 145–161. [Google Scholar]

- Morsing, M.; Schultz, M. Corporate social responsibility communication: Stakeholder information, response and involvement strategies. Bus. Eth. A Eur. Rev. 2006, 15, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B. The Hidden Wealth of Customers: Realizing the Untapped Value of Your Most Important Asset; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ricard, M. The Art of Happiness: A Guide to Developing Life’s Most Important Skill; Atlantic Books: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Trivers, R.L. The evolution of reciprocal altruism. Q. Rev. Biol. 1971, 16, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batson, C.D. Altruism in Humans; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Compton, W.C.; Hoffman, E. Positive Psychology: The Science of Happiness and Flourishing; Wadsworth Publishing Company: Wadsworth, OH, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rilling, J.K.; Gutman, D.A.; Zeh, T.R.; Pagnoni, G.; Berns, G.S.; Kilts, C.D. A neural basis for social cooperation. Neuron 2002, 35, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavides Espinosa, M.D.M.; Comeig, I.R.; Darós, L.C. Adaptación organizativa a los cambios tecnológicos en la industria cultural: Un estudio a partir de la economía experimental. Econ. Ind. 2013, 389, 95–106. [Google Scholar]

- Van Huyck, J.B.; Battalio, R.C.; Beil, R.O. Tacit coordination games, strategic uncertainty, and coordination failure. Am. Econ. Rev. 1990, 80, 234–248. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, H. Intelligence Reframed: Multiple Intelligences for the 21st Century; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, H. Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Emmerling, R.J.; Boyatzis, R.E. Emotional and social intelligence competencies: Cross cultural implications. Cross Cult. Manag. Int. J. 2012, 19, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goleman, D. Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ; Bantam Books: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Goleman, D. Social Intelligence: The New Science of Social Relationships; Bantam Books: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Goleman, D. Ecological Intelligence: How Knowing the Hidden Impacts of What We Buy Can Change Everything; Random House Digital, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Todd, P.M.; Gigerenzer, G. Ecological Rationality: Intelligence in the World; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Earley, P.C.; Ang, S. Cultural Intelligence: Individual Interactions Across Cultures; Stanford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Livermore, D. Leading with Cultural Intelligence: The New Secret to Success; AMACOM: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fleisher, C.S.; Bensoussan, B.E. Business and Competitive Analysis: Effective Application of New and Classic Methods; FT Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fuld, L.M. Competitor Intelligence: How to Get It, How to Use It; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Garriga, E.; Melé, D. Corporate social responsibility theories: Mapping the territory. J. Bus. Eth. 2004, 53, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windsor, D. Corporate social responsibility: Three key approaches. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. Corporate social responsibility evolution of a definitional construct. Bus. Soc. 1999, 38, 268–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, P.L. The evolution of corporate social responsibility. Bus. Horiz. 2007, 50, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Unconcerned Entrepreneur | Concerned Entrepreneur | |

|---|---|---|

| Unconcerned stakeholders | Exposure to reputational threats | Entrepreneur looks for concerned stakeholders |

| Concerned stakeholders | Stakeholders leave entrepreneur | Protection against reputational threats |

| Reactive Entrepreneur | Proactive Entrepreneur | |

|---|---|---|

| Stakeholders not perceiving advantange (short term) | Overperformance | Underperformance |

| Stakeholders perceiving advantage (long term) | Worse competitive position | Competitive advantage |

| Entrepreneur Deploying Minimum Effort | Entrepreneur Deploying Maximium Effort | |

|---|---|---|

| Stakeholders deploying miminum effort | Reputation lacks strategic value | Entrepreneur thinking reputationally |

| Stakeholders deploying maximum effort | Stakeholders thinking reputationally | Reputational intelligence |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pineiro-Chousa, J.; Vizcaíno-González, M.; López-Cabarcos, M.Á. Reputation, Game Theory and Entrepreneurial Sustainability. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1196. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8111196

Pineiro-Chousa J, Vizcaíno-González M, López-Cabarcos MÁ. Reputation, Game Theory and Entrepreneurial Sustainability. Sustainability. 2016; 8(11):1196. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8111196

Chicago/Turabian StylePineiro-Chousa, Juan, Marcos Vizcaíno-González, and M. Ángeles López-Cabarcos. 2016. "Reputation, Game Theory and Entrepreneurial Sustainability" Sustainability 8, no. 11: 1196. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8111196

APA StylePineiro-Chousa, J., Vizcaíno-González, M., & López-Cabarcos, M. Á. (2016). Reputation, Game Theory and Entrepreneurial Sustainability. Sustainability, 8(11), 1196. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8111196