Corporate Social Responsibility Applied for Rural Development: An Empirical Analysis of Firms from the American Continent

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Private Firms Involved in Rural Development through CSR

2.1. Benefits and Challenges

| Benefits | Challenges |

|---|---|

| - CSR generates positive effects on firm’s work environment, human capital attraction, and retention [30,31]. - The use of sustainability and CSR metrics helps decision-makers to set goals, gauge company’s progress, benchmark competitiveness, and compare alternatives of sustainable development [32,33,34,35]. - Access to economic incentives, favourable taxing, and preferential trade and sourcing programs [31,36]. - Companies with positive social image and responsible sourcing strategies have access to global markets and specialty niches [8,31,37]. - Stakeholder Dialog provides a way to personalize relationships with the company’s interest groups. It provides useful analytical concepts for diagnosis and prioritization of interests and strategies [1,8,33]. - Sustainable strategies can generate cost-reductions from increasing eco-efficiency, recycling, and waste management [4,36]. - Risks to profits, market share, supply, environmental treads, and reputation can be managed through CSR [4,5]. - Firms can strengthen their value chain by applying responsible sourcing initiatives [4,5,25,35]. | - CSR demands additional knowledge and resources from companies by getting involved in social concepts and areas beyond their expertise [31,38]. - Information about the performance of CSR strategies should be organized and properly displayed in a format that best supports the decision-making process [30,35]. - Firms usually must deal with bureaucratic procedures and regulations when interacting with governmental institutions [2,31,38]. - Generally managers find difficulties to demonstrate tangible-economic benefits from CSR, particularly in the short-run [4,30,33]. - Companies must identify their key stakeholders and define budgets and strategies to meet their demands according to their capacity and market conditions [1,31,35]. - Although consumers express willingness to make ethical purchases, it is not the most dominant criterion in their purchasing decision. Factors like price, quality, and convenience are still the most dominant [37,39]. |

2.2. Identification of Stakeholders and Strategies

3. Empirical Research

3.1. Methodology Applied for the Analysis of the Empirical Case Study

| Weighted Sample—All Industries | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Sample 100 | Privately Owned | Publicly Traded | FT-500 | Subsidiaries | Not Specified | State-Owned |

| Brazil | 20 | 16 | 2 | - | - | 1 | 1 |

| Colombia | 19 | 15 | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Mexico | 18 | 15 | 2 | - | - | 1 | - |

| United States | 16 | 10 | 3 | 2 | - | 1 | - |

| Argentina | 10 | 7 | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | - |

| Peru | 5 | 3 | 1 | - | 1 | - | - |

| Chile | 4 | 3 | - | - | - | 1 | - |

| Canada | 3 | 2 | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| Paraguay | 2 | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | - |

| Uruguay | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Bolivia | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Venezuela | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - |

3.2. Results from the Empirical Research

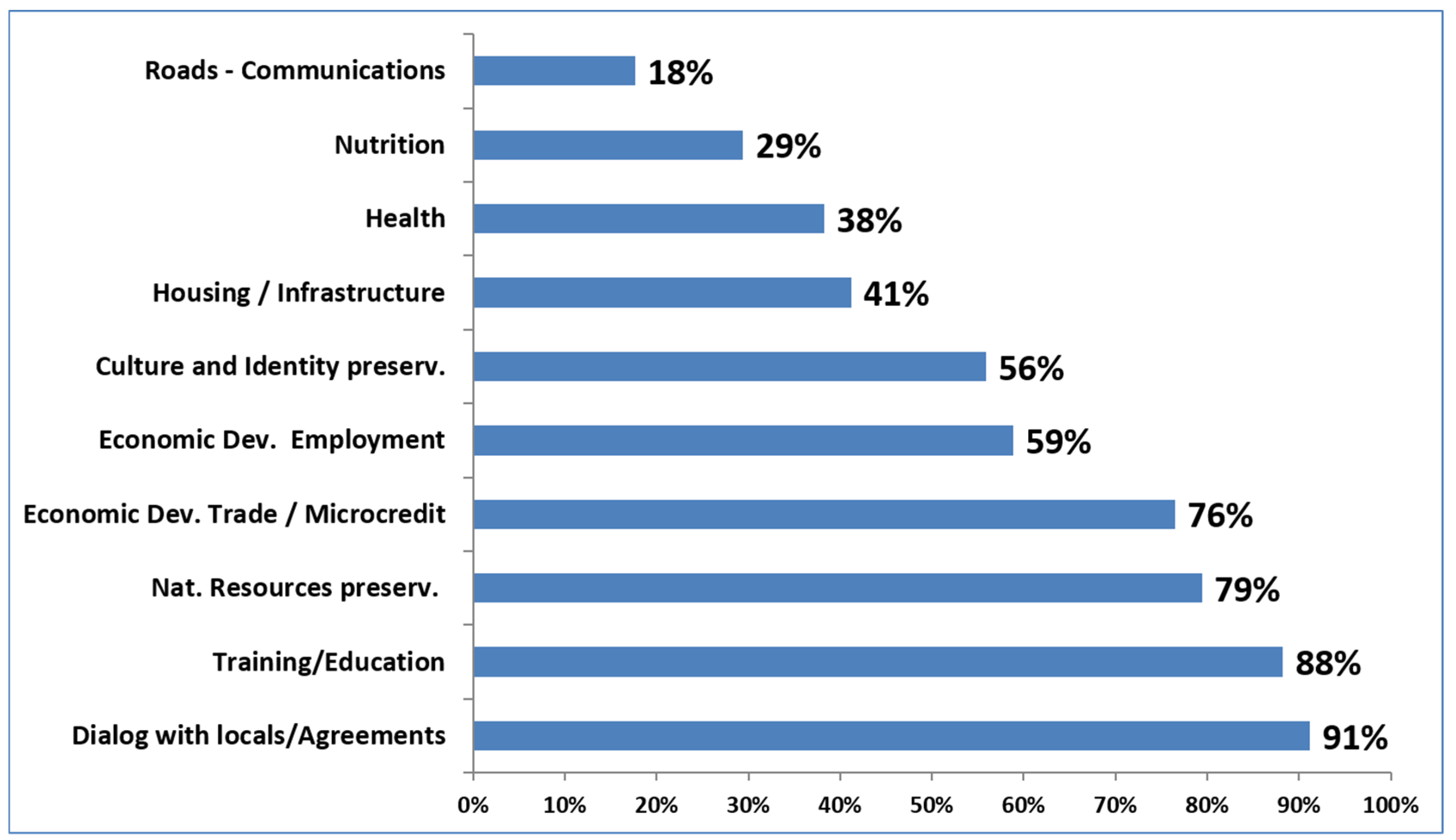

3.3. Type of Strategies for Rural Development

3.3.1. Dialog with Rural Communities and Local Organizations

| Type of Strategies | Number of Firms |

|---|---|

| Dialog with locals/Agreements | 31 |

| Direct Dialog (Surveys, Communitarian assemblies) | 23 |

| Dialog One to One (Commercial or Working relation) | 23 |

| Dialog through NGOs and local institutions | 23 |

| Committee or Responsible for Dialog | 18 |

| Indirect Dialog (workshops or public events) | 2 |

| Training/Education | 30 |

| Work related and Technical Skills training | 22 |

| Security and Safety Education | 22 |

| Material Supply Scholarships and Funding for students | 20 |

| Schools Building or Infrastructure improvement | 12 |

| Nat. Resources preservation | 27 |

| Environment technical training to Rural population | 21 |

| Support in preservation and reforestation campaigns | 17 |

| Technology Supply/Other | 13 |

| Economic Dev. Trade/Microcredit | 26 |

| Training and Microcredit for entrepreneurship | 16 |

| Supply Chain Development | 15 |

| Economic Dev. Employment | 20 |

| Employment Permanent contract | 19 |

| Employment Temporary contract | 6 |

| Culture and Identity preservation | 19 |

| Promotion of local activities, sports, and traditions | 17 |

| Support of local communitarian facilities | 9 |

| Housing/Infrastructure | 14 |

| Company + rural population involved in Construction | 11 |

| Provision of Materials | 7 |

| Credit | 3 |

| Health | 13 |

| Disease prevention Education | 10 |

| Medical brigades and check up | 4 |

| Medical Facilities (Construction or goods supply) | 1 |

| Nutrition | 10 |

| Nutrition related education | 5 |

| Supply of food goods | 4 |

| Brigades of Nutrition | 3 |

| Roads—Communications | 6 |

- (1)

- “Engagement”, in which the company assumes the role of partner in local development of the communities that are most affected by their operations.

- (2)

- “Operational Dialog”, whereby local communities, other neighbors, and local government representatives are informed about local forestry operations and discuss about possible impacts and ways to mitigate them.

- (3)

- “Constructive Dialog”, in which instruments of dialog are used to disseminate activities and to enable the exchange of information with all stakeholders with an interest in the company’s activities.

- (4)

- “Face to Face meetings”, which consists in visits by Fimbria’s representatives to communities that are not covered by engagement and operational dialogue, in order to understand the local situation.

3.3.2. Training/Education

3.3.3. Natural Resources Preservation

3.3.4. Infrastructure and Economic Development through Entrepreneurship and Employment

3.3.5. Promotion of Culture, Health, and Nutrition

4. Discussion

- -

- Importance of dialog with stakeholders: A key factor to consider is to establish channels for dialog with interest groups and development allies. Proper communication and understanding of community concerns facilitates the integration process and enables the maximization of available resources by tackling specific needs [2,33,38]. As reported by the analyzed companies, a popular measure was to establish mechanisms to facilitate dialog, reporting significant results for integration with local communities.

- -

- The involvement and management of rural development: A key element to ensure positive results in rural development strategies is the involvement of top management and executives in order and to motivate their teams and provide the necessary resources [5,30,33]. As reported by the evaluated firms, a common way to facilitate the proper management of CSR related strategies is delegating its follow-up and operation to a specific person or group of persons (depending to a great extent on the resources and time available). In the case of SMEs, the activities were generally developed by the owner or founder to guarantee the efficient use of invested resources.

- -

- The benefits of multi-institutional cooperation: An ideal measure to maximize resources and increase the scope of development projects is through cooperation with key stakeholders like governments and civil institutions [8,31,34,36]. As reported by the analyzed firms, multi-institutional interaction benefited companies by enabling access to governmental incentives, as well as to advisory services from rural development specialists and NGOs which facilitated the effective and efficient use of available resources.

- -

- To act local and to start with small projects: The number of beneficiaries and size of projects depends mainly on the available budget and the institutions involved. However, as expressed by the analyzed companies, in order to ensure positive outcomes, it is necessary to keep a close follow up and management of the deployed activities. Due to stakeholders having limited available resources, we recommended breaking down the intended development projects in different stages, in which the first stages include a reduced number of beneficiaries, to measure the performance and to learn during the implementation process in order to improve the implementation in the subsequent stages.

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix

| # | Name | Type | Sector | Counrtry | Participant Since |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | YPF S.A. | Public Company | Oil & Gas Processing | Argentina | 26/10/2005 |

| 2 | Carboclor S.A. | Private Company | Oil & Gas Processing | Argentina | 18/06/2010 |

| 3 | Xstrata Pachon S.A. | Subsidiary | Mining | Argentina | 14/07/2010 |

| 4 | Bertora & Asociados | Private Company | Financial Services | Argentina | 01/10/2010 |

| 5 | Parex Klaukol S.A. | Private Company | Construction | Argentina | 21/10/2010 |

| 6 | Ferva S.A. | Private Company | Construction | Argentina | 11/05/2011 |

| 7 | Animana Trading S.A. | Private Company | Personal Goods | Argentina | 20/06/2011 |

| 8 | Seguridad Integral Empresarial | Private Company | Support Services | Argentina | 11/10/2011 |

| 9 | Santa Fe Associates International | Private Company | Financial Services | Argentina | 23/11/2011 |

| 10 | SA San Miguel A.G.I.C | Private Company | Food Producers | Argentina | 06/09/2012 |

| 11 | BANCO FIE S.A. | Private Company | Financial Services | Bolivia | 26/11/2006 |

| 12 | TIM Participacoes S.A. | Private Company | Mobile Telecom. | Brazil | 04/04/2008 |

| 13 | Duratex S.A. | Private Company | Construction | Brazil | 20/02/2008 |

| 14 | Celulose Irani S.A. | Private Company | Forestry & Paper | Brazil | 07/11/2007 |

| 15 | BRF Brasil Foods S.A. | Private Company | Food Producers | Brazil | 28/05/2007 |

| 16 | Dudalina SA | Private Company | Personal Goods | Brazil | 23/01/2007 |

| 17 | Beraca Sabara Quimicos e Ingredientes | Private Company | Chemicals | Brazil | 04/01/2007 |

| 18 | Chemtech Servicos de Engenharia | Private Company | Industrial Equipment | Brazil | 05/12/2006 |

| 19 | Promon S.A. | Private Company | Industrial Equipment | Brazil | 08/05/2006 |

| 20 | INFRAERO | Unknown | Aerospace | Brazil | 12/03/2004 |

| 21 | CPFL Energia S.A. | Private Company | Electricity | Brazil | 17/02/2004 |

| 22 | Copagaz Distribuidora de gás ltda | Private Company | Oil Equipment | Brazil | 27/06/2003 |

| 23 | Furnas Centrais Eletricas sa | State-owned | Electricity | Brazil | 27/06/2003 |

| 24 | Klabin S.A. | Public Company | Forestry & Paper | Brazil | 27/06/2003 |

| 25 | Nutrimental S/A industria e comercio | Private Company | Food Producers | Brazil | 27/06/2003 |

| 26 | Souza Cruz | Private Company | Tobacco | Brazil | 07/01/2003 |

| 27 | Suzano Papel e Celulose | Private Company | Forestry & Paper | Brazil | 07/01/2003 |

| 28 | Samarco Mineracao S.A. | Private Company | Industrial Mining | Brazil | 31/08/2002 |

| 29 | ArcelorMittal Brasil | Private Company | Industrial Mining | Brazil | 22/08/2001 |

| 30 | Fibria Celulose S.A. | Public Company | Forestry & Paper | Brazil | 26/07/2000 |

| 31 | Natura Cosmeticos S/A | Private Company | Chemicals | Brazil | 26/07/2000 |

| 32 | Central de restaurantes aramark ltda | Unknown | Beverages | Chile | 29/03/2007 |

| 33 | Telefónica | Private Company | Fixed Line Telecom. | Chile | 19/11/2006 |

| 34 | Aguas Andinas S.A. | Private Company | Gas, Water & Oil | Chile | 07/08/2006 |

| 35 | Poch & Asociados | Private Company | Support Services | Chile | 01/05/2006 |

| 36 | Pacific Rubiales Energy | Private Company | Oil & Gas Processing | Colombia | 25/01/2011 |

| 37 | Organizacion Terpel S.A | Private Company | Oil Equipment | Colombia | 14/01/2011 |

| 38 | Pichichi S.A Sugar Mill | Private Company | Food Producers | Colombia | 28/01/2010 |

| 39 | Harinera del Valle S.A. | Private Company | Food Producers | Colombia | 18/01/2010 |

| 40 | Datexco Company | Private Company | Support Services | Colombia | 10/03/2009 |

| 41 | Central Hidroelectrica. | Private Company | Electricity | Colombia | 05/01/2009 |

| 42 | Ingenio Risaralda, S.A. | Private Company | Food Producers | Colombia | 19/03/2008 |

| 43 | Invesa S.A. | Private Company | Chemicals | Colombia | 19/03/2008 |

| 44 | Eternit Colombiana S.A. | Private Company | Construction | Colombia | 10/08/2007 |

| 45 | Sociedades Bolivar S.A. | Private Company | Financial Services | Colombia | 17/07/2007 |

| 46 | Frisby S.A. | Private Company | Beverages | Colombia | 28/06/2006 |

| 47 | Arme S.A. | Private Company | General Retail | Colombia | 27/06/2006 |

| 48 | Empresa de Acueducto y alcantarillado | State-owned | Gas, Water & Oil | Colombia | 12/10/2005 |

| 49 | Labfarve Fundacion laboratorio de farmacologia vegetal | Private Company | Support Services | Colombia | 04/10/2005 |

| 50 | Empresa de Energia del Pacifico | Private Company | Electricity | Colombia | 22/04/2005 |

| 51 | Industrial Agraria La Palma | Unknown | Food Producers | Colombia | 27/01/2005 |

| 52 | Endesa Colombia | Public Company | Gas, Water & Oil | Colombia | 25/01/2005 |

| 53 | Novartis de Colombia | Subsidiary | Pharmaceutical | Colombia | 25/01/2005 |

| 54 | Holcim (Colombia) S.A. | Private Company | Construction | Colombia | 01/10/2004 |

| 55 | BPZ Exploracion and Produccion s.r.l | Private Company | Oil & Gas Processing | Peru | 31/10/2007 |

| 56 | Corporacion Pesquera Inca | Private Company | General Retail | Peru | 06/02/2007 |

| 57 | LHH-DBM Peru | Private Company | Support Services | Peru | 13/04/2004 |

| 58 | Compania de Minas Buenaventura | Public Company | Industrial Mining | Peru | 02/04/2004 |

| 59 | Agricola Chapi S.A. | Unknown | Food Producers | Peru | 31/03/2004 |

| 60 | Banesco Banco Universal | Private Company | Banks | Venezuela | 27/04/2009 |

| 61 | Banco De Seguros Del Estado | Private Company | Nonlife Insurance | Uruguay | 03/09/2008 |

| 62 | Pollpar S.A. | Unknown | Food Producers | Paraguay | 20/12/2006 |

| 63 | Vision Banco S.A.E.C.A. | Private Company | Financial Services | Paraguay | 20/12/2006 |

| 64 | Segtec | Private Company | Aerospace | Mexico | 31/01/2011 |

| 65 | Magnekon, S.A. | Private Company | Electronic | Mexico | 05/01/2011 |

| 66 | SRNS Latinoamerica S.A. | Private Company | Industrial Telecom. | Mexico | 20/05/2010 |

| 67 | Grupo SEICI | Private Company | Support Services | Mexico | 05/03/2010 |

| 68 | Maquinaria del Humaya Tepic | Private Company | Construction | Mexico | 13/01/2009 |

| 69 | Nomitek SA de CV | Private Company | Support Services | Mexico | 13/01/2009 |

| 70 | Genomma Lab Internacional | Private Company | General Retail | Mexico | 07/04/2008 |

| 71 | Diseno y Metalmecanica | Private Company | General Industry | Mexico | 20/02/2008 |

| 72 | Eli Lilly y Compania de Mexico | Private Company | Pharmaceutical | Mexico | 24/05/2007 |

| 73 | Agricola Chaparral S.P R. de R.L | Private Company | Food Producers | Mexico | 30/03/2006 |

| 74 | Industrias Penoles, SAB de CV | Private Company | Industrial Mining | Mexico | 30/03/2006 |

| 75 | Novartis Corporativo | Private Company | Pharmaceutical | Mexico | 18/01/2006 |

| 76 | Satelites Mexicanos, SA de CV | Private Company | Fixed Line Telecom | Mexico | 18/01/2006 |

| 77 | Cooperativa La Cruz Azul | Unknown | Construction | Mexico | 16/01/2006 |

| 78 | Arca Continental, S.A | Public Company | Beverages | Mexico | 16/01/2006 |

| 79 | Riqras S.A. De C.V. | Private Company | Beverages | Mexico | 14/06/2005 |

| 80 | Fomento Economico Mexicano | Private Company | Beverages | Mexico | 24/05/2005 |

| 81 | CEMEX | Public Company | Construction | Mexico | 06/12/2004 |

| 82 | Mountain Equipment Co-op | Private Company | Personal Goods | Canada | 20/02/2006 |

| 83 | Rideau Recognition Solutions | Private Company | General Industry | Canada | 11/02/2005 |

| 84 | Talisman Energy Inc. | Public Company | Oil & Gas Processing | Canada | 10/02/2004 |

| 85 | BDP International, Inc. | Private Company | General Industry | USA | 28/01/2010 |

| 86 | Humanscale | Private Company | General Industry | USA | 20/01/2010 |

| 87 | ScienceFirst, LLC | Private Company | Media | USA | 14/04/2009 |

| 88 | Technibus, Inc. | Private Company | Electronic | USA | 19/01/2009 |

| 89 | North American Community | Private Company | Media | USA | 05/02/2008 |

| 90 | Advanced Labelworx, Inc. | Private Company | General Industry | USA | 10/01/2008 |

| 91 | Dalberg Global Development Advisors | Private Company | Support Services | USA | 01/06/2007 |

| 92 | Sinak Corporation | Private Company | Construction | USA | 14/05/2007 |

| 93 | Act Global | Private Company | General Retail | USA | 23/03/2006 |

| 94 | The Coca-Cola Company | Public Company | Beverages | USA | 14/03/2006 |

| 95 | The Omanhene Cocoa Bean Company | Unknown | Not Applicable | USA | 26/05/2004 |

| 96 | Allied Soft | Private Company | Software | USA | 11/05/2004 |

| 97 | Starbucks Coffee Company | Public Company | Beverages | USA | 08/04/2004 |

| 98 | Seagate Technology | Public Company | Technology | USA | 06/04/2004 |

| 99 | Johnson Controls Inc. | Public Company | Automobiles | USA | 31/03/2004 |

| 100 | Green Mountain Coffee | Public Company | Beverages | USA | 11/03/2004 |

References

- Carroll, A.B. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.L. The virtue matrix: Calculating the return on corporate responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2002, 80, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Blowfield, M.; Frynas, J.G. Editorial Setting new agendas: Critical perspectives on Corporate Social Responsibility in the developing world. Int. Aff. 2005, 81, 499–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utting, P. Corporate responsibility and the movement of business. Dev. Pract. 2005, 15, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, J.M. The impact of corporate social responsibility in supply chain management: Multicriteria decision-making approach. Decis. Support Syst. 2009, 48, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B.; Shabana, K.M. The business case for corporate social responsibility: A review of concepts, research and practice. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archel, P.; Husillos, J.; Spence, C. The institutionalisation of unaccountability: Loading the dice of Corporate Social Responsibility discourse. Account. Organ. Soc. 2011, 36, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J. A study on the models for corporate social responsibility of small and medium enterprises. Phys. Proc. 2012, 25, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Global Compact. Global Corporate Responsibility Report; United Nations Global Compact Office: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- UN Global Compact United Nations Global Compact Office. Available online: https://www.unglobalcompact.org (accessed on 16 August 2014).

- Frynas, J.G. The false developmental promise of corporate social responsibility: Evidence from multinational oil companies. Int. Aff. 2005, 81, 581–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narrod, C.; Roy, D.; Okello, J.; Avendaño, B.; Rich, K.; Thorat, A. Public-private partnerships and collective action in high value fruit and vegetable supply chains. Food Policy 2009, 34, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNFPA. State of World Population. 2007. Available online: http://www.unfpa.org/publications/state-world-population-2007 (accessed on 15 July 2015).

- Rio +20 United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development. Available online: http://www.uncsd2012.org (accessed on 15 July 2015).

- Goldsmith, A. The private sector and rural development: Can agribusiness help the small farmer? World Dev. 1985, 13, 1125–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraceno, E. Recent trends in rural development and their conceptualization. J. Rural Stud. 1995, 10, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, C. Further Ideas about Local Rural Development: Trade Production and Cultural Capital; Centre for Rural Economy: Newcastle University, UK, 2000; p. 49. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Heuvel, G.; Soeters, J.; Gössling, T. Global Business, Global Responsibilities: Corporate Social Responsibility Orientations within a Multinational Bank. Bus. Soc. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, J. Public-private Partnerships for Health: A trend with no alternatives? Development 2004, 47, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasche, A. Toward a model to compare and analyze accountability standards—The case of the UN Global Compact. CSR Environ. Manag. 2009, 16, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacchetta, M.; Jansen, M. (Eds.) Making Globalization Socially Sustainable; World Trade Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011.

- Murray, K.B.; Vogel, C.M. Using a hierarchy-of-effects approach to gauge the effectiveness of corporate social responsibility to generate goodwill toward the firm: Financial versus nonfinancial impacts. J. Bus. Res. 1997, 38, 141–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, A.J.; Keim, G.D. Shareholder value, stakeholder management, and social issues: What’s the bottom line? Strateg. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.; Buchholtz, A. Business and Society: Ethics, Sustainability, and Stakeholder Management; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kell, G.; Levin, D. The Global Compact network: An historic experiment in learning and action. Bus. Soc. Rev. 2003, 108, 151–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasche, A.; Gilbert, D.U. Institutionalizing global governance: The role of the United Nations Global Compact. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2012, 21, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kell, G. The global compact selected experiences and reflections. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 59, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, A.; Meister, M. Corporate social responsibility attribute rankings. Public Relat. Rev. 2008, 34, 49–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arato, M.; Speelman, S.; van Huylenbroeck, G. Benefits and Challenges of Integrated Initiatives for Sustainable Rural Development: The Case from Northern Mexico. OIDA IJSD 2014, 7, 31–48. [Google Scholar]

- Eilbirt, H.; Parket, I.R. The practice of business: The current status of corporate social responsibility. Bus. Horiz. 1973, 16, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemphill, T.A. Legislating corporate social responsibility. Bus. Horiz. 1977, 40, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celma, D.; Martínez-Garcia, E.; Coenders, G. Corporate social responsibility in human resource management: An analysis of common practices and their determinants in Spain. CSR Environ. Manag. 2012, 21, 82–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, D.; Owen, J.R.; van de Graaff, S. Corporate social responsibility, mining and “audit culture”. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 24, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharmin, S.; Khan, N.A.; Belal, A.R. Corporate Community Involvement in Bangladesh: An Empirical Study. CSR Environ. Manag. 2014, 21, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Székely, F.; Knirsch, M. Responsible leadership and corporate social responsibility: Metrics for sustainable performance. Eur. Manag. J. 2005, 23, 628–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W. Study on the relationships between corporate social responsibility and corporate international competitiveness. Energy Proc. 2012, 17, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulstridge, E.; Carrigan, M. Do consumers really care about corporate responsibility? Highlighting the attitude-behaviour gap. J. Commun. Manag. 2000, 4, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E.; Liedtka, J. Corporate social responsibility: A critical approach. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.C. Corporate Social Responsibility: Not Whether, But How; Center for Marketing: Dartmouth, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 3–701. [Google Scholar]

- Frain, J. Introduction to Marketing; Cengage Learning EMEA: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Naftalin, A. Confrontation: Part 1 Measuring social responsibility: Chimera or Reality? Organ. Dyn. 1973, 2, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giessen, L.; Böcher, M. Rural Governance, forestry, and the promotion of local knowledge: The case of the German rural development program “Active Regions”. Small Scale For. 2009, 8, 211–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shucksmith, M. Disintegrated Rural Development? Neo-endogenous Rural Development, Planning and Place-Shaping in Diffused Power Contexts. Sociol. Rural. 2010, 50, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdoch, J. Networks—A new paradigm of rural development? J. Rural Stud. 2000, 16, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shortall, S.; Shucksmith, M. Integrated rural development: issues arising from the Scottish experience. Eur. Plan. Stud. 1998, 6, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giessen, L.; Böcher, M. Integrated Rural Development Policy in Germany and Its Potentials for New Modes of Forest Governance. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Lukas_Giessen/publication/266881294_Integrated_Rural_Development_Policy_in_Germany_and_its_Potentials_for_new_Modes_of_Forest_Governance/links/5448b0170cf2f14fb8142e6c.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2016).

- Dutrénit, G.; Rocha-Lackiz, A.; Vera-Cruz, A.O. Functions of the Intermediary Organizations for Agricultural Innovation in Mexico: The Chiapas Produce Foundation. Rev. Policy Res. 2012, 29, 693–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward, D.; Edwards, P.; Birkin, F. Some evidence on executives’ views of corporate social responsibility. Br. Account. Rev. 2001, 33, 357–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IFFO Global Standards for Responsible Supply. Available online: http://www.iffo.net/iffo-rs-standard (accessed on 17 August 2015).

- Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI). Available online: https://eiti.org/es (accessed on 15 July 2015).

- Starbucks C.A.F.E. Available online: http://www.starbucks.com/responsibility/sourcing/coffee (accessed on 15 July 2015).

- IFC’s Good Practice for Strategic Community Investment. Available online: http://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/topics_ext_content/ifc_external_corporate_site/ifc+sustainability/learning+and+adapting/knowledge+products/publications/publications_handbook_communityinvestment__wci__131957690757 (accessed on 15 July 2015).

- British Retail Consortium Global Standards. Available online: http://www.brcglobalstandards.com (accessed on 23 July 2015).

- Sure Global Fair SGF. Available online: http://www.sgf.org/home (accessed on 15 July 2015).

- Starbucks 2013 Communication on Progress. Available online: https://www.unglobalcompact.org/participation/report/cop/create-and-submit/active/22257 (accessed on 11 December 2014).

- Cop Indupalma. Available online: https://www.unglobalcompact.org/participation/report/cop/create-and-submit/active/22613 (accessed on 11 December 2014).

- Holcim Colombia Informe de Desarrollo Sostenible 2012. Available online: https://www.unglobalcompact.org/participation/report/cop/create-and-submit/learner/23357 (accessed on 11 December 2014).

- Informe de Sostenibilidad 2012 Codensa. Available online: https://www.unglobalcompact.org/participation/report/cop/create-and-submit/active/34071 (accessed on 11 December 2014).

- Minera Yanacocha S.R.L. Communication on Progress 2012. Available online: https://www.unglobalcompact.org/participation/report/cop/create-and-submit/advanced/18555 (accessed on 11 December 2014).

- Industrias Peñoles 2012 Sustainability Report. Available online: https://www.unglobalcompact.org/participation/report/cop/create-and-submit/active/22010 (accessed on 11 December 2014).

- Fomento Economico Mexicano 2013 Communication on Progress. Available online: https://www.unglobalcompact.org/participation/report/cop/create-and-submit/detail/21570 (accessed on 11 December 2014).

- BRF Brasil Foods S.A. 2013 Communication on Progress. Available online: https://www.unglobalcompact.org/participation/report/cop/create-and-submit/advanced/29331 (accessed on 11 December 2014).

- Communication on Progress—Fibria’s 2012 Sustainability Report. Available online: https://www.unglobalcompact.org/participation/report/cop/create-and-submit/active/22041 (accessed on 11 December 2014).

- Furnas Centrais Eletricas S/A Relatório de Sustentabilidade 2012. Available online: https://www.unglobalcompact.org/participation/report/cop/create-and-submit/active/26641 (accessed on 11 December 2014).

- Industrias Klabin Relatório de avaliação dos compromissos assumidos com o Pacto Global 2012. Available online: https://www.unglobalcompact.org/system/attachments/57841/original/Avaliacao_dos_compromissos_assumidos_com_o_Pacto_Global_VF_com_logo.pdf?1389014151 (accessed on 11 December 2014).

- Informe de Sostenibilidad Invesa 2012. Available online: https://www.unglobalcompact.org/participation/report/cop/create-and-submit/detail/21386 (accessed on 11 December 2014).

- Independence S.A. Memoria de Sostenibilidad 2011. Available online: https://www.unglobalcompact.org/participation/report/cop/create-and-submit/active/18275 (accessed on 11 December 2014).

- Energía Eléctrica del Pacífico EPSA 2° Comunicación de Progreso CHEC-PACTO GLOBAL. Available online: https://www.unglobalcompact.org/system/attachments/13653/original/Comunicaci_n_de_progreso_CHEC_2011.pdf?1325609383 (accessed on 11 December 2014).

- Pacific Rubiales Communication on Progress 2012. Available online: https://www.unglobalcompact.org/participation/report/cop/create-and-submit/advanced/22214 (accessed on 11 December 2014).

- Pichichi Sugar Mills Communication on Progress 2012. Available online: http://www.pactoglobal-colombia.org/index.php/adheridos-1/pichichi-s-a-sugar-mill (accessed on 11 December 2014).

- Souza Cruz Communication on Progress 2011-12. Available online: https://www.unglobalcompact.org/participation/report/cop/create-and-submit/active/29311 (accessed on 11 December 2014).

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arato, M.; Speelman, S.; Van Huylenbroeck, G. Corporate Social Responsibility Applied for Rural Development: An Empirical Analysis of Firms from the American Continent. Sustainability 2016, 8, 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8010102

Arato M, Speelman S, Van Huylenbroeck G. Corporate Social Responsibility Applied for Rural Development: An Empirical Analysis of Firms from the American Continent. Sustainability. 2016; 8(1):102. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8010102

Chicago/Turabian StyleArato, Miguel, Stijn Speelman, and Guido Van Huylenbroeck. 2016. "Corporate Social Responsibility Applied for Rural Development: An Empirical Analysis of Firms from the American Continent" Sustainability 8, no. 1: 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8010102

APA StyleArato, M., Speelman, S., & Van Huylenbroeck, G. (2016). Corporate Social Responsibility Applied for Rural Development: An Empirical Analysis of Firms from the American Continent. Sustainability, 8(1), 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8010102