1. Introduction

In political science, the social integration of Europe is rather a neglected topic [

1,

2,

3]. A likely reason for this is the reduced visibility of social consequences of the unification process in comparison to institutional and governmental changes. Obviously there has been a stronger emphasis on measures facilitating sustainable economic and political integration than on the social aspects of the integration process on the side of EU politics, social integration sometimes even being met with an overt lack of interest. This political strategy—if one wants to call it such—is guided by the hope that integration on the system and the institutional level will lead to a convergence of wealth that will quasi-automatically be followed by cultural and social convergence (social integration).

The differentiation of system and social integration goes back to work by Lookwood [

4]. System integration refers to the level of coordination between certain subsystems of a society, whereas social integration concentrates on the inclusion and participation of individuals in a community. A central question for the present-day EU then is if the now 28 member states of the EU will develop into an integrated social system that fosters the inclusion and participation of individual citizens. Based on the long-term hope that the European Union will develop into a new form of society beyond the nation state [

5,

6], the process of social integration is likely to manifest itself in transnational civil-society engagement of EU citizens—if at all.

Supranationalism, intergovernmentalism, and the EU’s quasi-domestic market are concrete forms of transnational society-building in the political and the economic sphere. The social integration process proceeds much slower [

7,

8]. In contrast to political or systemic processes of integration, transnational social integration takes place in actual border-crossing interaction among citizens of the member states. Fox [

9] sees such activities as aspects of a “globalization from below”. Border regions—the focus of the present study—are a particular case in this context because of their special opportunity structure for face-to-face interaction. Border region residents are agents of transnational social integration different from other agents (as migrants or sojourners or tourists); the speculation seems in place that their potential investment into transnational social integration may

a priori be more sustainable, as they do not have to struggle with the typical chores of migrants or sojourners, nor is there the superficiality of mere touristic endeavors.

The current study of veteran citizens of four EU countries examines potentials for the development of sustainable transnational civil society engagement in adjacent Czech, French, German, and Polish border regions. For a theoretical framing of the construct “transnational civil society” we refer to the social capital approach in the tradition of Putnam [

10]. We assume that social capital in the form of social networks facilitates social integration and with it the development of a sustainable civil society.

The development of a transnational civil society demands particular forms of social capital, because in this case social networks must cross nation-state borders. Transnationality in our context is characterized by the everyday crossing of borders between regions that belong to different nation states. The present study focuses on transnational civil-society engagement as a core component of transnational social capital and—in our view—central building block on the trajectory toward sustainable transnational civil society engagement. Civil-society engagement brings together the concepts and theoretical approaches of the civic society and social capital theory. This clarification makes it obvious that we are not looking at changing governance structures, as has recently been done by Fioramonti [

11] in an important collection of papers, nor at transnational activities of migrants, as done by Snel

et al. [

12] or Nwana [

13], but at grass-roots engagement and the interest in cross-border civil-society activities.

It is the aim of the present paper to characterize different forms of social capital in the border regions as “bridging” or “bonding” [

10], and to identify promoting and constraining factors for the development of a sustainable transnational civil-society engagement. In the analysis of these aspects we concentrate on purposively sampled cities in the Czech Republic, France, Germany, and Poland. Transnationality is brought in by choosing cities near the common borders of these countries, easily accessible for the border-region residents of two neighboring nation states.

2. Social Capital and (Transnational) Civil Society

Both concepts were revived in the 1990s in reaction to a discussion that asserted a decline of norm acceptance, value-guidedness, and solidarity in society, and a rise of individualism, elbow mentality, and hierarchic self-interest [

14,

15,

16,

17]. Although the two concepts originate from different intellectual traditions, both approaches underscore the importance of strong formal and informal social networks in the community as an important foundation for a stable democracy [

18]. As Putnam and Cross [

19] put it, “…recent work on social capital has echoed the thesis of classical political theorists from Alexis de Tocqueville to John Stuart Mill that democracy itself depends on active engagement by citizens in community affairs … there is mounting evidence that the characteristics of civil society affect the health of our democracies, our communities, and ourselves” (p. 6). Looking at individuals (“ourselves”) in a 22-year panel study, Boehnke and Wong [

20] showed that informal political participation in adolescence can have positive mental health consequences in mid-adulthood under certain circumstances.

The concept “civil society” is not clearly defined in the literature [

21]. Kocka [

22] describes civil society as a space of social self-organization between state, market, and private sphere, a locale of clubs, circles, networks, and NGOs that offer a place for public discussion, conflict, and communication, a space for efforts in the interest of common welfare. It is also argued that civil-society engagement is characterized by a particular logic of action, namely a strong connection with common interest in lucid autonomy from state or market interests.

Although the production of common welfare seems to be the focus of civil-society engagement there is also a discussion about the dark sides of civil society [

23]. It is argued, that civil-society engagement is not

per se a source of normatively positive sequelae for society as a whole. Kopecky and Mudde [

24] speak of “uncivil society … as a subset of civil society” (p. 11). Chambers and Kopstein [

25] assert the existence of a “bad civil society”, referring to consequences of network building that are well known, but theoretically and empirically not really integrated into the concept of civil society. Another critique pertains to the overly normative content of the concept “civil society” that elucidates a particular idea of a good or ideal society. Nonetheless, in stressing the relevance of a vibrant and strong civil society, essentially all authors are united. They see predominantly positive consequences for society as a whole. A vibrant civil society is seen as the solution for problems of social integration and stability of communities [

26]. A decline in civil-society activities is seen as problematic [

10,

11,

27].

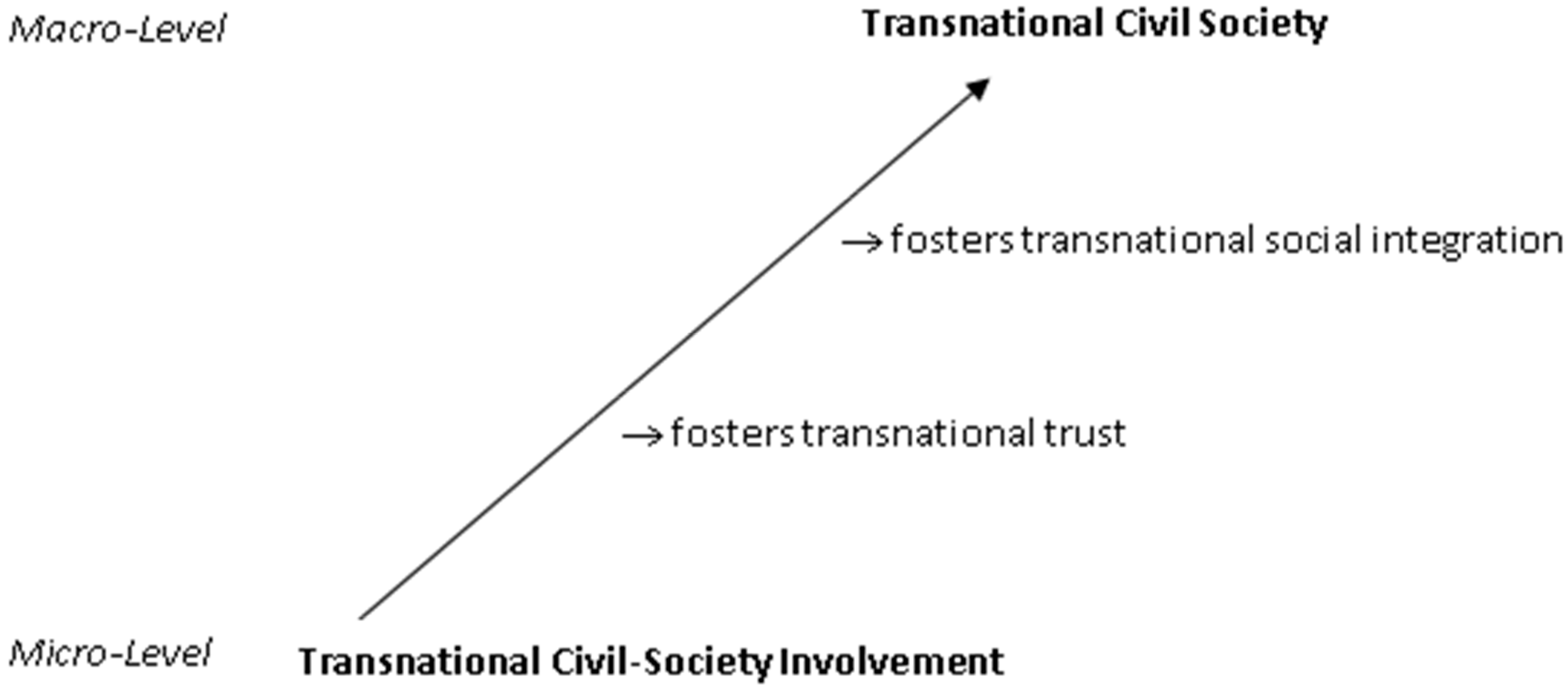

Civil-society engagement of individuals is at the core of civil society development on the micro-level. Without individual civil-society activities there obviously is no civil society. This applies to the local, national, and transnational level (see

Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The development of a transnational civil society.

Figure 1.

The development of a transnational civil society.

The definition of the concept “transnational civil society” is as fuzzy as the civil-society concept in general, but additionally a spatial aspect must obviously be incorporated. Especially in the context of the European integration process, one finds a spatial contextualization of the concept in the discussion about the development of a European civil society [

28,

29]. In discourse addressing the development of civil structures in the context of globalization one finds the terms of a global or a transnational or international civil society [

30,

31]. Gilson [

32] recently, however, drew our attention to the French sociologist-philosopher Henri Lefebvre and his work on the

Production of Space [

33] as a point of departure in defining what transnational civil society is. A somewhat lengthy quote from Gilson nicely portrays our own position; she defines transnational civil society as “

the ongoing process resulting from intersecting and diverse experiences of individuals and groups. In so doing, it aims further to redefine the spatiality of activism, by questioning how advocates determine the physical borders within which they function alongside those cognitive borders to which they attach themselves, and how those very borders are constantly redefined by their interactions” (p. 288). Typically transnational civil society studies evolve around organizational structures, like NGOs [

34], but such meso- and macro-level aspects are not in focus here. We rather define transnationality in the tradition of anthropologist Glick Schiller [

35], who speaks of it as “

the creation of a new social space [one spanning at least two nations] that is fundamentally grounded in the daily lives, activities, and social relationships of quotidian actors” (p. 5).

In the current paper we try to examine the potential for the development of a sustainable transnational civil society in border regions. Thereby we do use a territorial contextualization that offers an opportunity structure for cross-border contacts. We assume that certain opportunity structures are spatially bound: Proximity to nation-state borders in combination with the availability of urban infrastructure is likely to constitute a hotbed for transnational civil society, even if—to stretch the metaphor a bit further—engagement of citizens in cross-border civil-society activities is currently still lukewarm. We are convinced that sustainability of cross-border civil-society engagement rests to a large degree on the production of a common social space (in the sense of Lefebvre) across nation-state borders. Hereby we implicitly, unlike Korac [

36], assume that real (and not, e.g., virtual) cross-border contact is needed to construct or produce this common space.

Our emphasis on the relevance of formal and informal interpersonal networks as a sort of glue for the common social space points to the close connection between social capital theory, especially in the tradition of Putnam [

10], and the discussion about the integrative role of a vibrant civil society. Civil-society engagement constitutes an intersection of both approaches. Putnam broadens the view of Coleman [

37] and Bourdieu [

38] by arguing that social capital as constituted by social ties, networks, and norms has benefits not only for individuals but in addition also for collectivities. Social capital is a private

and a public good with benefits accruing not only to those people making the investment in social networks but also to the wider community in the form of positive externalities [

39]. Thus, Putnam in particular brings the research agendas of civil society and social capital together.

From Putnam’s [

10] point of view, it is especially civil-society engagement in associations and clubs that boosts social trust, common values, and norms of reciprocity. The structural elements of engagement and social networks and the cultural elements of trust and values of solidarity foster the social capital of a society. The amount of social capital arising from civil-society engagement augments social integration and stability of a society. A vibrant civil society becomes the focus of sustainable social integration. Following Putnam’s argument, the amount of social capital of a society is an important determinant of the political and economic development of a region [

15]. The present study’s focus on transnational social capital in the border regions of four EU countries suggests a distinction between local, national, and transnational social capital. For a more concrete characterization of these forms of social capital a differentiation into “bonding” and “bridging” capital is necessary. This differentiation is used by Putnam [

10,

40] in newer publications as a reaction to the critique [

41,

42,

43] that in his approach the potential negative consequences of social networks are neglected [

44]. As argued before, civil-society engagement and the resulting social capital does not in all instances have positive effects for the whole community. Putnam [

10] differentiates “bonding” and “bridging” structures of networks. Earlier work by Bourdieu [

38] or Coleman [

37] stressed that associations and networks have a tendency to reproduce social inequality because they are often built upon processes of exclusion and not inclusion. Exclusive network structures, in particular, like extremist parties or sects or associations like the Ku-Klux-Klan cement homogenous groups. This so-called “bonding” social capital has negative effects for society as a whole and damages democratic goals, but may have positive effects for the members belonging to this kind of closed social group or network. Bonding structures are characterized by a high level of exclusivity—the members form a homogenous social group. Inside the group reciprocity and trust are strongly emphasized, corresponding with little openness to outsiders. In contrast, bridging structures are characterized by openness for contact with different groups or networks. In the context of a transnational civil society networks with bridging structures are particularly important, because transnational civil-society engagement has a bridging, open structure per definition, offering room for contact with foreign neighbors. Putnam [

10] sees the development of bridging social capital as a highly challenging task, because the cooperation of individuals that are different from one another in one or more ways is a main feature of contact in these types of groups or networks. Putnam [

40] assumes to find a lower level of social trust in such heterogeneous networks, “

people find it easier to trust one another and cooperate when the social distance between them is less” (p. 159). In the case of cross-border activities the typically different native language of people is the most obvious external attribute that has to be “bridged.” Moreover, different mentalities forged by different historical and biographical backgrounds, often embedded in a common history of conflict, must come together.

Against this background the present study examines and compares local and transnational forms of social capital in different border regions and additionally analyzes their relation amongst each other and further determinants for their development. It thereby intends to uncover the bases for the creation of sustainable cross-border civil-society engagement.

3. Hypotheses

In the first step of unfolding our hypotheses, we refer to a survey of civil-society engagement and social trust in the border regions under scrutiny. In a further step we focus on the relationship between different forms of national/local and transnational civic engagement. Finally, we come to the more comprehensive question which circumstances foster or constrain transnational engagement. Here we turn to the impact of existing local (non-transnational) social capital and of other structural and individual/dispositional factors on the development of transnational social capital.

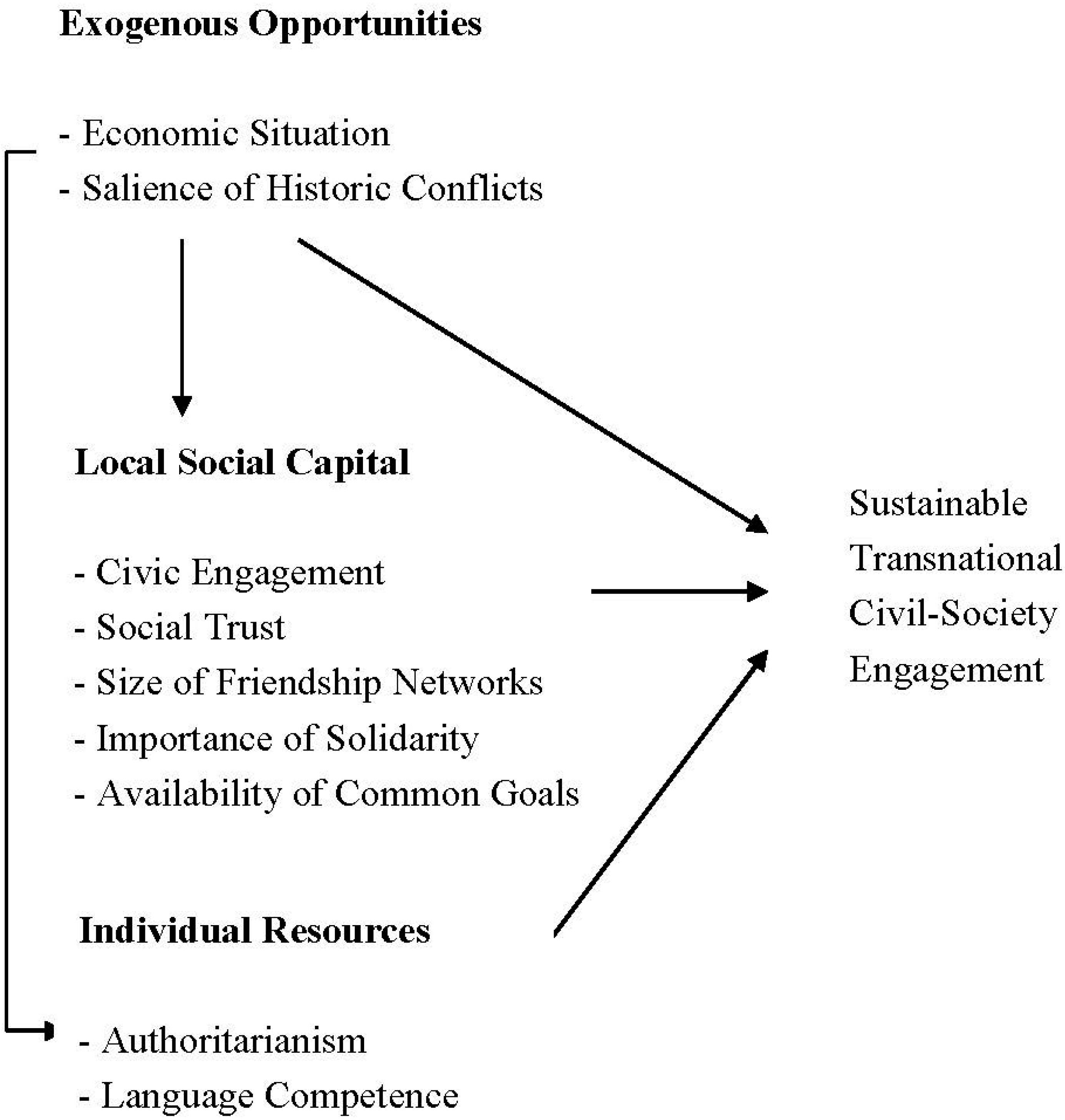

Figure 2 gives an overview of factors under scrutiny in our model.

Figure 2.

Conceptual model.

Figure 2.

Conceptual model.

Starting with the assumption that existing local social capital influences the development of transnational civil society a number of indicators like social trust among members of the ingroup, sizes of friendship networks, and locally-focused social engagement were integrated into the model. We assume that a high amount of existing engagement stands for a more heterogeneous and open structure of existing networks, whereas a small amount indicates a tendency towards more closed structures. Additionally, we assume that individual dispositions like an authoritarian personality and a lack of competence in the neighbor’s language also influence the willingness for transnational civil-society engagement. Authoritarianism has been discussed in the human geography literature as one of the barriers against border-crossing activities, because of its defining component of fearing “the other” [

45]. Intuitively, the importance of competencies in the neighbor’s language can be seen as a prerequisite for a sustainable trans-border civil-society engagement. Variability in competencies is likely to be high; frequencies of learning a foreign language that is not English differ greatly in Europe, with Germany being the country that has fewest learners of a non-English foreign language in high school [

46]. Last but not least, macro-level conditions like the economic situation in the region or the salience of historic conflicts in the area are integrated into the model. Based on the model depicted in

Figure 2, the following hypotheses will be tested:

H1:

Local social capital fosters transnational civil-society engagement.

This assumption is by no means trivial. It is, on the contrary, often assumed that social capital acquired in interaction with an ingroup (and, thus, having bonding qualities), serves as a barrier against activities that cross group borders. Putnam [

40], however, does not

per se see such a mechanism at work: “Bonding social capital can be a prelude to bridging social capital, rather than precluding it” (p. 165). Arguments that back our hypothesis are based on presumed similarities in the motivation to join local and transnational activities. Personal attributes like optimism, elevated life satisfaction, and a high level of self-control and self-confidence have been shown to be important determinants for the development of social trust and, thus, important common motives for local/national and transnational civic engagement [

47,

48]. Furthermore, a prior positive experience with civil-society participation should strengthen the willingness to engage in trans-border engagement. Using longitudinal data, Stolle and Hooghe [

49] demonstrated the sustainable socialization effect of a positive participation experience.

H2:

The lower the level of competence in the “neighboring” language, the lower the likelihood of transnational civil-society engagement.

The lack of common language competencies does not

a priori mean that involved individuals are unable to communicate with each other; younger citizens, in particular, are often able to communicate in English. Nevertheless, the lack of a common language is a sizable obstacle for transnational activities as reported by experts in all cities included in the present study [

50]. Transaction costs increase enormously in comparison to local activities [

51].

H3:

The more authoritarian the attitudes of an individual, the lower the likelihood of his/her engagement in transnational civil-society activities.

Authoritarianism is a classic concept [

52] that, while having been “revamped” conceptually on different occasions [

53,

54,

55], has proven powerful in explaining dispositional openness for contact with “the other” [

56,

57]. It seems highly plausible to assume that due to their strong conventionalism authoritarians will perceive the crossing of group borders—national borders in this case—as a potential threat of the status quo. Authoritarians should, thus, have a strong tendency toward bonding structures in their social networks that stand against cross-border activities.

H4:

The better the economic situation in a region, the higher the likelihood of engagement in transnational civil society.

The economic prosperity of a region is an important macro-level context condition for the development of civic engagement [

58]. A better infrastructure advances activities; higher levels of life satisfaction in wealthier regions increase the willingness of individuals to get involved in civil-society activities.

H5:

The more salient historic conflicts in a region, the lower the likelihood of transnational civil-society engagement.

Beyond economic prosperity, the mental preparedness of a region for transnationality is another important factor. In the regions adjacent to the common border of Germany and its eastern neighbors, but also to some degree to France, the consequences of World War II until today serve as an important frame for intergroup relations [

59]. Historical antagonisms and conflicts still purport certain attitudes towards the neighbor and influence the willingness to engage in contact. This is particularly true for the regions on the German-Polish, and the German-Czech border, but to some degree even

vis-à-vis France.

H6:

The smaller the spatial distance between centers of civil society on either side of a common border, the higher the likelihood that individuals engage in transnational civil-society activities.

Our focus of analysis is on border regions. This choice of a study design is based on the assumption that the inhabitants of these regions enjoy advantageous conditions for cross-national activities due to high spatial proximity in the offering of opportunity structures for sustainable transnational civil-society engagement. Spatial aspects of civil society formation have long been emphasized (e.g., [

60]), but have rarely been researched empirically.

4. Research Design, Sample and Instruments

The study utilizes data from representative surveys conducted under the supervision of the authors in late 2006 on both sides of the border in the mentioned regions. In Germany and France telephone interviews were conducted, whereas in Poland and the Czech Republic surveying occurred in face-to-face interviews due to the then still somewhat lower density of—land-line—telephone access.

The sample consists of individuals from 14 years of age onward. Two pairs of cities were chosen from each border region. For the German-Czech border region an additional split into East and West German regions was undertaken, because the contemporary German-Czech borderland encompasses areas that on the German side had been part of East Germany and part of West Germany before the fall of the Iron Curtain. This resulted in the inclusion of altogether four pairs of urban centers in that region (see

Figure 3). Only urban centers situated closely to the common border were included, thus allowing relatively easy access for the foreign neighbors.

Exogenous opportunities (see

Figure 2) were operationalized as being reflected by the average household income of residents of a particular city, by the salience of historic conflicts among study participants from a particular city, and by the distance of the city to the border. Information about the net household income per capita was extracted from Eurostat data for the various regions. The salience of historic conflicts was measured by asking respondents to indicate to what degree they feel emotionally strained by historic events pertaining to a specific region, e.g., German occupation in World War II, or the expulsion of Germans in the

sequelae of the war. The items were developed for the current project. Here survey data were aggregated to the city level. Distance of a city to the border was operationalized as the linear distance between the city center and the closest border crossing point.

Figure 3.

Survey sampling points.

Figure 3.

Survey sampling points.

An individual’s local social capital was assessed by an adaptation or verbatim use of well-established measures from other surveys, e.g., the so-called

Freiwilligensurvey (volunteer survey) of the German government [

61]; or various waves of the Eurobarometer [

62], and work by van Deth [

63]. Civil-society engagement was captured by asking for the frequency of having been active during the last year in 13 different domains (protection of the environment, animal rights/Third World, peace, human rights/activism against right-wing extremism or xenophobia/regional matters/church, religion/social care, neighborly help/voluntary fire brigade/arts, theater, cultural events/folklore or heritage association/sports, hobby groups, organized leisure get-togethers/youth club, PTA/professional associations, unions/politics (parties)) on a five-point frequency scale ranging from “never” to “very often”. Domains were randomly sequenced in interviews with participants. Cronbach’s

α for the four countries were: Germany 0.78; France 0.69; Poland 0.87; Czech Republic 0.82. In this case, “being active” encompassed participation, cooperation, and honorary work and/or donations. Enlarging the definition of engagement,

i.e., not confining it to activities in associations or clubs only, makes it possible to also consider short-term engagement or historically more recent forms of engagement such as contributing to a citizens’ initiative.

In each of the 16 localities, respondents were selected by a random probability process. Sample sizes are documented in

Table 1.

Table 1.

Design and sample sizes.

Table 1.

Design and sample sizes.

| Border Region | City in the German Border Region | Cities in the Adjacent Neighboring Border Region |

|---|

| East Germany–Poland | Görlitz 75 | Zgorzelec 80 |

| | Frankfurt on the Oder 78 | Słubice 80 |

| N = 313 | 153 | 160 |

| East Germany–Czech Republic | Pirna 75 | Děčín 75 |

| | Annaberg-Buchholz 75 | Karlovy Vary 75 |

| N = 300 | 150 | 150 |

| West Germany–Czech Republic | Marktredwitz 77 | Cheb 77 |

| | Furth im Wald 82 | Domažlice 77 |

| N = 313 | 159 | 154 |

| West Germany–France | Müllheim 75 | Mulhouse 75 |

| | Kehl 75 | Strasbourg 75 |

| N = 300 | 150 | 150 |

The size of an individual’s social network was identified by asking respondents for the number of people that belong to their “circle of friends.” The item was adapted from the International Social Survey Program (ISSP) study 2001 [

64]. Family members were explicitly excluded. Response categories were “1 to 5”, “6 to 10”, “11 to 15”, “16 to 20” and “more than 20”.

Trust was measured by a direct question for the extent of trust towards people of one’s own nationality. The item was taken from the 1999 wave of the World Values Survey [

65]. Solidarity and common welfare orientation respectively were covered by a question for the respondents’ preference regarding the social norm “to bear responsibility for each other”, an item taken from the German Allbus study of 2002 [

66].

Regarding individual resources questions referred to the level of competence in speaking the neighbor country’s language and to level of authoritarianism. The language question had response options ranging from “not at all” to “very good” on a 4-point scale. Authoritarianism was measured using three items, “Crimes should be punished more severely”, “To preserve law and order, one should be more restrictive towards outsiders and trouble makers”, and “Obedience to and respect for the superior belong to the most important features someone should have”. Items were taken from the so-called

Zusammenstellung sozialwissenschaftlicher Items und Skalen (ZIS), a German collection of social science items and scales [

67]. The three items were averaged to form a scale of authoritarianism. Cronbach’s α for the four countries were: Germany 0.74; France 0.64; Poland 0.49; Czech Republic and 0.63. The consistency coefficients certainly leave room for improvement, but in light of a rule of thumb that can be traced back to Nunally [

68]—namely that above a minimum value of 0.40 short scales can be seen as having satisfactory consistency if their alpha exceeds the number of items multiplied by 0.10—consistency is sufficient.

The level of engagement in transnational civil-society activities was surveyed by the question how often the person has taken part in activities that necessitated crossing the border and in which individuals from both sides of the border were involved. The enumeration of areas of engagement was formulated in analogy to the question that asked for local social capital, but participants only had to give one overall assessment. In order to also capture potential of transnational activities, the questionnaire additionally contained an item asking for the respondents’ interest in either starting or continuing engagement in cross-border civil-society activities. Finally, trust towards neighbors was measured by a direct question about the trustworthiness of people from the other side of the border. This information will also be utilized for marking social capital as “bridging” insofar as a difference score between trust towards one’s compatriots and people from the respective neighbor country was calculated and included in the analyses.

Raw data as well as instruments in German, French, Polish, and Czech (not English) can be made available to academic users upon a request sent to the corresponding author.

5. Results

In order to form a first impression of the extent of both local and transnational civil-society engagement in the four border regions a comparison of means was undertaken (see

Table 2). Data were aggregated across cities within the four countries.

Table 2.

Civil-society engagement in border regions.

Table 2.

Civil-society engagement in border regions.

| Variable | Poland | Czech Republic | France | Germany |

|---|

| Local engagement | M | 1.71 | 1.90 | 2.30 | 2.72 |

| SD | 0.65 | 0.63 | 0.67 | 0.63 |

| N | 119 | 265 | 142 | 594 |

| Transnational engagement | M | 1.91 | 1.95 | 1.78 | 2.09 |

| SD | 0.99 | 1.16 | 1.06 | 1.21 |

| N | 160 | 298 | 149 | 610 |

| Interest in transnational engagement | M | 2.38 | 2.13 | 2.81 | 2.80 |

| SD | 0.94 | 1.16 | 1.17 | 1.15 |

| N | 154 | 297 | 149 | 609 |

For the nation states, the differences obtained confirm well-known results from other studies, according to which—local—civil-society engagement in post-socialist countries (here in the Polish and Czech border regions) is comparatively low [

69]. Differences to the German and French border regions were sizable: One-way ANOVAs with subsequent Scheffé tests were significant at

p < 0.01. Looking at engagement in transnational civil-society activities, the picture emerged as less clear. Here, respondents from the French border region showed a considerably lower level than respondents from all other regions, which did not differ significantly (

p < 0.01) from each other. Interest in transnational engagement revealed the same differentiation between new and old members of the European Union (as portrayed for local engagement), indicating a lesser interest among persons from the Polish and Czech sample sites.

A differential correlation between overall transnational engagement and specific areas of local activities could not be corroborated; the degree of engagement in all 13 activities correlated significantly positively (

p < 0.01) with the frequency of transnational engagement. Assuming a ‘bridging’ character of transnational engagement thus seems in place; since, in addition, none of the 13 activities correlated positively with authoritarian attitudes. There is no indication for a tendency of social closure toward outgroups. An exploratory factor analysis for each of the four countries suggested that three distinct fields of local activities can be distinguished in all subsamples. Generating additive indices for each of these and relating them to transnational engagement and interest, respectively, also yields consistently positive and significant effects (see

Table 3). Hence, local civil-society engagement features rather “bridging” than “bonding” characteristics even though some of the activities such as cultivation of heritage and home might have been suggesting something else.

Table 3.

Pearson’s correlation coefficients for different fields of local activities and transnational engagement/interest.

Table 3.

Pearson’s correlation coefficients for different fields of local activities and transnational engagement/interest.

| Country | Engagement/Interest | Local Engagement “Politics” | Local Engagement “Leisure” | Local Engagement “Heritage” |

|---|

| Germany | Transnational engagement | 0.23 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.27 ** |

| Transnational interest | 0.27 ** | 0.26 ** | 0.19 ** |

| Poland | Transnational engagement | 0.44 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.24 ** |

| Transnational interest | 0.30 ** | 0.40 ** | 0.22 ** |

| Czech Republic | Transnational engagement | 0.36 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.31 ** |

| Transnational interest | 0.33 ** | 0.44 ** | 0.27 ** |

| France | Transnational engagement | 0.33 ** | 0.15 ** | 0.33 ** |

| Transnational interest | 0.47 ** | 0.43 ** | 0.14 * |

Social trust is presumed to be another element of social capital. A subsequent analysis compares trust in one’s compatriots with trust in people from the respective neighbor country (see

Table 4).

Except for France, social trust in one’s compatriots is stronger than trust in the neighbors. In this case a repeated-measures ANOVA with the two trust measures as the within-subject and country as the between-subject factor showed that both factors and their interaction were highly significant (p < 0.001). The difference for the two measures was most pronounced for respondents from Poland and the Czech Republic.

In a next step of analysis the factors introduced in the theoretical model (see

Figure 2) were tested for their specific impact on transnational civil-society engagement. The potential predictors refer to the contextual as well as to the individual level. It is; thus, necessary to change the method of statistical data analysis. Such relationships are most adequately modeled by means of multilevel techniques, as they allow for a simultaneous estimation of the predictive power of predictors on different levels [

70,

71,

72,

73]. In the present case, the hierarchical data structure comprises 1031 respondents on the individual level after listwise deletion of missing data, which are nested under the 16 urban regions at the contextual level. The subsequent analyses differ from the above-documented descriptive analyses insofar as the country level is now replaced by the less strongly aggregated regional level. Due to the small number of cases at the country level, the introduction of country as a third level of aggregation did not seem feasible. Also, the fact that the cities included in the analyses were coupled by design had to be disregarded for the subsequent analysis.

Table 4.

Social trust towards compatriots and towards the neighbor country’s population.

Table 4.

Social trust towards compatriots and towards the neighbor country’s population.

| Variable | Poland | Czech Republic | France | Germany |

|---|

| Social Trust towards Compatriots | M | 2.56 | 2.65 | 2.49 | 2.49 |

| SD | 0.72 | 0.71 | 0.67 | 0.65 |

| N | 158 | 300 | 150 | 602 |

| Social Trust towards Persons from the Neighbor Country | M | 2.19 | 2.32 | 2.67 | 2.38 |

| SD | 0.83 | 0.81 | 0.66 | 0.72 |

| N | 150 | 282 | 142 | 584 |

In multilevel analyses, estimating effects typically proceeds stepwise: first, the proportion of the total variance in the two dependent variables explained by the urban region of residence is determined; statisticians call this the null model(s). Subsequently, the relative importance of individual and contextual predictors is tested in separate so-called “random intercept” models, followed by a test as to whether the strength of individual-level predictors varies between contexts (so-called “random slope” models), and finally by a test whether these differences in strength of individual-level predictors between contexts can be accounted for by the variables measured on the context level (so-called cross-level interactions). All calculations were performed using the restricted-maximum-likelihood technique provided by the multilevel modeling software package HLM 6.01 [

73]. Everything taken together, it is clear that,

vis-à-vis a strict interpretation of the mathematical assumptions of random effects modeling with HLM, our approach is suboptimal; there is, however, emerging evidence that HLM is largely robust against violations of several of its assumptions [

74,

75,

76].

The analytic purpose of estimating an unconstrained null model first is to decompose variance in the dependent variable into the variances allocated to each of the examined levels under scrutiny. The importance of the variance proportions is accessed by the so-called intra-class correlation coefficient. Looking at how much of the systematic variation in transnational civil-society engagement (the variance explainable by any of the predictors included in the model) could be accounted for by variables on either level showed that the regional context explained some 4% of the systematic variation for engagement and some 10% for interest. Nine-tenths, or more, of the systematic variation in transnational civil-society engagement were, thus, accounted for by individual-level predictors.

The computation of the subsequently tested “random-intercept” models rests upon the assumption of a context-invariant prediction of transnational civil-society engagement at the individual level (“fixed effects”). In other words, it is postulated that the observed individual characteristics affect transnational engagement in the same way across contexts, independent of the respondents’ place of residence. Detailed results are omitted here, because substantive findings strongly resemble those documented later in

Table 5.

For two individual level predictors the fixed-slopes assumption did not hold: The predictive power of local civil-society engagement and of the ability to speak the neighbor’s language varied among the 16 cities. The level of local activities mattered most in predicting transnational civil-society engagement in Děčín and least on the German side of the Polish border in Frankfurt on the Oder (activities) and Görlitz (interest). As for the impact of knowledge of the neighbor’s language, it mattered most in Furth im Walde for both activities and interest, and least in the two most “touristy” sites, Karlovy Vary (activities) and Strasbourg (interest). Neither of the two random slopes could be explained on the grounds of the three variables measured on the context level. All cross-level interactions were far from significant.

In sum, transnational civil-society engagement can largely be ascribed to differences among respondents as to their personal features.

Table 5 illustrates the relevance of these features in detail and shows the regression coefficients for the three context factors as well: The various facets of local social capital at the individual level (see

Figure 2) mostly prove to be relevant predictors. Looking at the effect sizes reveals local civil-society activities as the by far most important factor for both aspects of transnational involvement (engagement and interest).

In the same way, a small difference in trust towards compatriots versus citizens from the neighbor country as well as a strong common welfare orientation enhance participation in transnational civil-society activities and the interest in such activities respectively, the latter effect, however, being statistically rather weak.

Contrary to our assumption, for the number of friends—as a further structural aspect of the social capital of a person—neither an impact on engagement nor on interest in transnational engagement was corroborated. Nonetheless, the first hypothesis regarding the—positive—relevance of local social capital is largely confirmed by the data. One must say, however, that differences in the importance of local activities were found between contexts that are difficult to explain ex post, noting, though, that coefficients were always positive.

In line with our expectations, a high competence in communicating in the language of the respective neighbor country had a promoting effect on engagement and interest in transnational civil-society activities (Hypothesis 2). Also, here, however, differences in impact between cities were found that are difficult to interpret ex post. Likewise in line with our assumption, authoritarian attitudes constitute a significant barrier for both aspects of transnational civil-society engagement (Hypothesis 3). While male persons are more strongly involved in transnational activities, and also signal a higher interest, age does play a noteworthy role only for the behavioral aspect of transnational engagement. Members of the older birth cohorts and particularly senior respondents turn out to be much more active in comparison to adolescents and young adults. For educational background it can be stated that persons with a higher educational attainment articulate somewhat more interest than persons with lower educational attainments, but interestingly enough do not show more actual engagement in transnational civil-society activities.

Table 5.

Social trust towards compatriots and towards the neighbor country’s population.

Table 5.

Social trust towards compatriots and towards the neighbor country’s population.

| Predictor | Range of Scores | Transnational Engagement |

|---|

| | | Participation in Civil-Society Activities | Interest in Civil-Society Activities |

|---|

| Context-Level Effects | | | |

| Average net household income | Standardized (in 1.000 Euro) | 0.05 * (0.23) | 0.05 * (0.22) |

| Salience of historical conflicts | 1 “not at all salient”–5 “very strongly salient” | −0.36 + (−0.15) | 0.21 (0.09) |

| Distance to the border | Continuous (in km) | −0.01 * (−0.12) | −0.01 * (−0.11) |

| Individual-Level Effects | | | |

| Gender (ref.: male) | Female | −0.22 ** (−0.09) | −0.23 *** (−0.10) |

| Age (ref.: 14 to 29 years) | 30 to 49 years | 0.18 * (0.07) | 0.06 (0.02) |

| 50 to 64 years | 0.15 + (0.06) | 0.00 (0.00) |

| 65 years and older | 0.32 ** (0.10) | −0.04 (−0.01) |

| Education (ref.: lower level) | Secondary school qualification | 0.09 (0.04) | 0.14 * (0.06) |

| Participation in local civil-society activities | 0 “never took part in a single activity”–52 “very often involved in all 13 activities” | 0.05 *** (0.41) | 0.06 *** (0.42) |

| Random Slope Model |

| 0.03–0.11 | 0.02–0.12 |

| Social network size (reference category: “1 to 5 friends”) | “6 to 10 friends” | 0.07 (0.03) | 0.00 (0.00) |

| “11 to 15 friends” | 0.09 (0.03) | 0.10 (0.03) |

| “16 to 20 friends” | 0.13 (0.04) | 0.01 (0.00) |

| “20 friends and more” | 0.15 (0.06) | 0.07 (0.03) |

| Neighbors’ language mastery | 1 “not at all”–4 “very good” | 0.21 ** (0.16) | 0.19 * (0.14) |

| Random Slope Model |

| −0.08–0.72 | −0.18–0.63 |

| Difference in trust in neighbors as opposed to compatriots | 0 “same trust in own group and in neighbors”–6 “no trust in neighbors, highest trust in compatriots” | −0.19 *** (−0.11) | −0.31 *** (−0.18) |

| Common welfare orientation | 1 “not important at all”–5 “very important” | 0.06 (0.05) | 0.07 * (0.06) |

| Authoritarian attitudes | 1 “not at all authoritarian”–4 “very strongly authoritarian” | −0.15 ** (−0.09) | −0.17 ** (−0.10) |

| Explained Variance | | | |

| Variance on the individual level (σ2) | 0.91 | 0.80 |

| Variance on the contextual level (τ2) | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| Intra-class correlation coefficient (ρ) | 0.021 | 0.033 |

| R2 contextual variance | | 66.3% | 81.4% |

| R2 total variance | | 30.4% | 40.8% |

Models portrayed in

Table 5 include three context-level predictors concerning the 16 urban regions in addition to the individual predictors. These context features are the available average household income as an indicator for the mean prosperity level, the average historic conflict burden perceived by the respondents of each locality as an indicator of the salience of historical conflicts in a region, and the distance between the sampled city and the next border crossing as an element of the opportunity structure. Unlike the conflict variable, the two other variables concur with our expectations regarding their impact on transnational civil-society engagement. A higher welfare standard has a rather positive impact (Hypothesis 4), whereas a greater spatial distance has a significantly impeding effect (Hypothesis 6). Problematic neighborhood relations due to historical conflicts are the only factor that yields a trend contrary to our assumptions (Hypothesis 5). The level of conflict salience in a region is essentially unrelated to the interest in transnational civil-society activities, but fosters the actual participation in transnational civil-society activities (

p < 0.10).

After taking into account the additional predictors at contextual level, the share of explained total variance rests at 30.4% for engagement and at 40.8% for interest in transnational civil-society engagement.

6. Conclusions

In the present study we examined potentials and determinants of sustainable transnational civil-society engagement. We compared conditions in border regions in the Czech Republic, France, Germany, and Poland. Germany and France represent “old” members of the European Union, whereas Poland and Czech Republic are rather new members. To identify advancing and restricting aspects and especially the role of pre-existing local social capital, eight city pairs were examined with multilevel methods.

Our theoretical framework comes from the social capital approach in the tradition of Putnam. Referring to transnational civil-society engagement, we proposed that especially pre-existing locally garnered social capital advances cross-border activities because of similarities in the motivation for both forms of activities. We also assumed that, because of the bridging character of transnational engagement, there are also factors that impede this form of engagement. Descriptively, our results confirm the expected level differences in the potential for local and transnational civil-society engagement and in transnational trust. People in the post-socialist new member states of the EU (Poland and Czech Republic) surveyed in our study showed a significantly lower level of civil-society engagement and were also less interested in civic participation in comparison to respondents in the old member states (Germany and France). Reasons for this seem to lie in the aftermath of a socialization in a centralized hierarchical society and negative experience with mostly enforced “civil” activities that generally lead to reserved attitudes of the population towards institutionalized forms of engagement [

68]. Pre-existing locally garnered social capital is the strongest predictor for transnational engagement as well as interest. Worth highlighting is the fact that we did not find in any region a negative relation between certain sub-domains of local engagement (like sports or cultural activities) and transnational activities. A generally positive attitude towards civil-society engagement is the most important predictor for transnational engagement. So, although the difference between in- and outgroup separates local and transnational engagement, both forms of engagement are positively correlated. Other predictors like authoritarianism, history-based resentments, low cross-border trust, or language competencies exhibited a significantly smaller impact. A tradition and socialization experience that advances a civil-society orientation (as obtainable in local clubs or informal groups) advances transnational engagement. What remains puzzling is that civil-society engagement is rather a masculine form of citizen participation and that it is in particular the older cohorts that get involved in cross-border activities. The finding that men engage more strongly in transnational civil-society activities than women needs further research attention. Is it, maybe, that such activities offer power, an aspect more appealing to men? Or is this finding a consequence of a possible unavailability of engagement options attractive for women? As for the age variation it could be that one just needs a longer socialization into civil-society engagement, and that there is no cohort effect at work, but also this needs further research attention. It might also have been the case that our list of activities did not encompass enough activities most attractive to youth.

The multilevel analysis showed that context factors are also relevant, but they have a significantly smaller influence than individual attributes of citizens. Also here the study offers a nut to crack in further research: Why is context so much less relevant than individual competencies? It is clear after this study that the exact quality of a context makes local civil-society experience (and for that matter knowledge of the neighbor’s language) differentially important for transnational engagement, but which exact quality that is, remains in the dark.

Binding our research back to the literature is difficult, because individual level quantitative research on trans-border civil-society engagement is extremely scarce. Of course, recent literature on global and transnational civil-society networks exists in large quantities (e.g., [

11,

12]), but inclinations of ordinary citizen to get involved in such activities are rarely if ever in the focus of such studies. One would probably best turn to the political socialization literature to find a link [

77], but also here studies are typically concerned with cross-border activities of migrants with their neighboring heritage country. Conceptually, the impact of trans-border activities of non-migrants has been discussed by Paasi [

78].

As with any research it is obvious that the study has certain limitations. We see the fact that all evidence (beyond the estimate of economic prosperity in the countries included and the spatial distance of the sampled cities to borders) is self-reported. It would have been ideal to also include objective data about opportunities for civil-society engagement in the cities (and the opportunity structure as a whole) into our model. The almost exclusive inclusion of self-report data is likely to downplay the importance of the exact infrastructure for a transnational civil society and augment the impact of personal resources. In view of our finding that specific opportunity structures per city differ in their impact on transnational engagement the inclusion of objective data on what is available as a field of transnational engagement in a particular city would have been helpful. Our conclusion regarding the high impact of individual-level variables should thus be treated with some caution. To revert to Putnam’s famous metaphor on “bowling alone”, one should emphasize that it obviously matters how people use the available opportunity structures and what matters when strengthening sustainable civil society has been the policy-related goal of the present research. What was, however, ignored (for reasons of data availability) in the current study was the question of what happens, when there just is no bowling alley, where you could either bowl with your friends or cross-border neighbors or “alone”.

When seeking an answer to the question, which precursors make trans-border civil-society engagement most sustainable, it seems legitimate to state that one has to have experience with local civil-society engagement, speak the language of the neighbor (to a sufficient degree), trust “thy” neighbor, and have a sufficient level of life experience, which comes with age. Just having a large social network is simply not enough.