1. Introduction

Although the term

sustainable development had then been in wide circulation for almost two decades, Dryzek [

1] insisted in 2005 that it still referred “not to any accomplishment, still less to a precise set of structures and measures to achieve collectively desirable outcomes” but that it remained “a discourse”. Another decade on, and confirming his view that meanings of the term are still being explored, this special issue of

Sustainability will provide “an environmental sociology approach to understanding and achieving the widely used notion of sustainability” [

2]. The particular focus of this article is on how business corporations with a commitment to sustainable development are beginning to understand what sustainability means for them and what their particular practice of the term is achieving.

For some time already, scholars have expressed their misgivings that the corporations’ implementation of what they choose to call

sustainability is not that at all. In 2004, Gray and Milne [

3] point out that triple-bottom-line (TBL) accounting is in danger of being confused with sustainability reporting, a key argument for which is the organization-level

vs. system-level perspective that separates the two. In 2010, Gray’s [

4] literature survey is able to observe that “most business reporting on sustainability and much business reporting on activity around sustainability has little, if anything, to do with sustainability” (p. 48). Nine years later, in 2013, Milne and Gray [

5] question whether TBL is helpful at all in moving us towards sustainability. I shall discuss these misgivings in the methodological rationale. My own view is that such terms as

sustainability start their lives as labels for new ideas that will move the arguments forwards. Then meanings (plural) develop as a consequence of practices (plural)—both intellectual and behavioral. We can learn about how the term is being understood by its practitioners, as we study their practice; and there may be value in that knowledge. Understanding how business corporations might move towards more sustainable modes of operation is one of many research projects within environmental sociology. However, according to a leading researcher, scholars have not yet developed comprehensive theories for sustainability management; we do not have a clear view of where to get to or how to get there [

6].

Shifting focus from “there” to “here”, knowledge about how far business has gotten in managing for sustainability is also in short supply. In a recent article reviewing research in the field, Zollo, Cennamo, and Neumann [

7] observe that a great deal of research effort to date has been allocated to the two “broad sets of questions: why should companies move beyond serving merely economic purposes and what makes a company more sustainable” (p. 242). As a supplement to work on the theoretical, long-term models, they argue, we should also study the stepwise process of organizational evolution towards sustainability

i.e., where “sustainable” business practice is now and where it may be going. This article makes a contribution to knowledge of how one category of business organization, very large, British-based, natural resource extraction corporations, has begun to manage its operations for sustainability.

2. Hypothesis Development

The corporations in the object of study include British Petroleum, Rio Tinto, Shell, and Anglo-American, (see

Section 4. Method for details of selection criteria). These companies have made public commitments to pursuing a sustainable future and they make use of nature both in terms of resource extraction and as a sink for unwanted byproducts of production processes. Their intention to move towards “sustainable” modes of operation means that they will also be at the forefront of any measures undertaken to organize for a sustainable relationship with the natural environment. Studying how they are implementing practices whose aim is a sustainable co-existence with nature and how they represent these practices’ interaction with nature, will provide an insight into how they understand the term

sustainability and where this understanding may be taking us.

The primary object of study was an electronic text database of social and environmental reports and press releases describing how 25 different business corporations, dominated by the extractive MNCs previously mentioned, are managing for sustainability. In order to identify patterns in the selection and arrangement of words, very large volumes of text, ideally running upwards of millions of words, are necessary. Only then will individual words occur often enough in the database for usage patterns to become apparent. As one among many tools of discourse analysis, the corpus linguistic approach can provide findings at a macro-level. However, with such volumes of text to be analyzed, a computer search method has to be employed. The researcher must approach the corpus having worked out some hypothesis regarding what may (or may not) be found in the object of study. This procedure is described below.

Such words as

targets,

reporting, and

controls, have long been key words in the discourse of modern business, and it is no surprise that these corporations take a similarly managerial approach in the implementation of their environmental commitments. Taking British Petroleum’s annual sustainability report [

8] as an example of the genre and word searching through the downloaded PDF document, one finds the word

management in regular use. BP cares “about the safe

management of the environment” (emphasis added) (p. 3). Drilling down from this overview perspective, the report includes representations of more specific aspects of managing the environment:

“We take steps to assess and manage potential impacts on biodiversity, such as compiling a wildlife or biodiversity management plan or consulting with relevant experts and agencies to assess suitable actions.”

(emphasis added) (p. 45)

From the perspective of this article, it is also interesting to note how management, understood as a social, organizational process, combines the various objectives of the corporation in one system:

“BP’s operating management system (OMS) (.) brings together BP requirements on health, safety, security, the environment, social responsibility and operational reliability, as well as related issues, such as maintenance, contractor relations and organizational learning, into a common management system.”

(emphasis added) (p. 25)

If we interpret this statement through the lens of environmental sociology, it would seem that BP’s perception of the natural landscape is mediated through its operational management system (OMS). If the OMS includes a similarly managerial approach to sustainability as it does to the corporation’s traditional, oil and gas activities, then we should expect it to contain targets for BP’s sustainable relationship with the natural landscape as well as records of actual performance and accounts of the discrepancy—positive or negative—between the two. Making the safe assumption that the other so-called “green” corporations are also using the same managerial approach to their sustainability ambitions, it ought to be possible to find evidence in their textual representations that helps us to understand how nature is incorporated into their operating “management-for-sustainability” processes. In the remainder of this article, the terms green business and sustainable business are used simply as a convenient label for the corporations in this study. No normative claim regarding the achievement of sustainable goals is intended.

Hypotheses

In searching through the database of green business texts, therefore, the first hypothesis is that we should find words representing (i) the natural landscape and (ii) management processes. In addition to finding this evidence, a review of the words may provide clues to how the corporations perceive natural space through the lens of their operating management system. More significantly, the second hypothesis is that we should find textual evidence in which the corporations make representations of nature as the object of the sorts of processes of monitoring, reporting and control that one associates with a typical operational management system e.g., words from category (i) ought to appear as objects of verbs in category (ii).

The computer-based process of searching for particular words can, of course, only identify the presence of particular textual signs. The move from a word—understood purely as a textual signifier—to meaning is a necessarily interpretive process in which ambiguity can exist and must be resolved by human intervention. The linguistic evidence presented in the findings section contains no greater interpretive intervention than such avoiding of ambiguities.

In the final section, however, and responding to the call of this special issue, the “linguistic discourse” presented in the findings is interpreted within the context of corporate “managing-for-sustainability” practice. The article suggests how this social process influences corporate perceptions and understandings of the natural landscape.

3. Methodological Rationale: A Theory of Words, Meaning, and Practice

The theoretical underpinning for the interpretation of the findings brings together a theory of words, meaning and, most importantly, practice, which corresponds closely with Hajer’s [

9] understanding of discourse:

“Discourse is here defined as a specific ensemble of ideas, concepts, and categorizations that are produced, reproduced and transformed in a particular set of practices and through which meaning is given to physical and social realities.”

(emphasis added) (p. 44)

His understanding of discourse contextualizes its ideas within certain actions and he argues that actors assign meanings to reality through social processes of practice (see also van Leeuwen [

10]). Using Hajer’s meaning, a particular discourse derives some of its uniqueness from the particular practices of the actors. Assuming that the extractive MNCs in this sample are approaching the challenge of sustainable development by implementing broadly similar practices, the ideas, concepts, and categorizations circulating within their discourse of sustainability will be broadly homogeneous. Some environmental scholars have already argued along these lines

i.e., that terminology acquires meaning for a given group of practitioners through the operationalization of ideas [

11,

12]. Wenger’s

Communities of Practice [

13] provides the central theory of meaning formation in this conceptualization of discourse and in this article. Sociolinguistics had previously linked language use to variables such as race, gender, age, and social class (see Labov [

14], Macaulay and Trevelyan [

15], and Wolfram [

16]). The introduction of the concept of a community of practice, however, provides greater explanatory power in accounting for linguistic variation for example, between two ethnically British, middle-class, university-educated women, one of whom works, say, for British Petroleum while the other works for Greenpeace.

This latter point illustrates one implication of Hajer’s “practice-dependent” understanding of discourse and offers one possible explanation for the often-observed phenomenon of conceptual fuzziness. Scholars in many different research environments have already pointed out the variation in meanings of particular terms or attempted normative definitions of key terminology [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Such fuzziness is not necessarily undesirable. The term

sustainable development has been an extremely powerful driver of change, partly perhaps because its fuzziness has enabled it to appeal to a broad constituency of opinion. This article takes no normative stance on what definition should be assigned to the term. Neither, however, does it ignore the plasticity of some so-called sustainability discourse. Milne, Kearins, and Walton [

23] (see also [

24]) is an example of scholarship that deconstructs the discourse of self-styled sustainable business, by drawing attention to the intellectual inconsistencies that lie within the rhetorically-persuasive representations. In my reading of green business discourse, it is the more general statements—often delivered by the CEOs and/or the communications departments and often focused on goals, values, principles, or the future—that are most prone to this sort of fanciful sustainability discourse. Such discourse needs critical examination with a view to exposing its inconsistencies.

Increasingly, therefore, I have turned my attention to the nuts and bolts of the environmental management reports as a more reliable representation of what the corporation is doing. I concede that the corporations are making only partial representations of a much more complicated reality and that their decision what to represent and what not to represent is, most probably, weighted by instrumental interests. However, I think the language representations of practice are sincere albeit partial, attempts by the corporation to describe its reality.

Returning to the relationship between words and meaning, the second theoretical assumption of this article is that the meaning a community of practice associates with a word is reflected in the way in which the community uses the word. This position belongs to theory of language in use. The chronology in the study, as well as the associated development of theories of language in use, can be traced through Firth [

25], Austin [

26], Searle [

27], and Halliday [

28]. In parallel with the development of computing power in the later decades of the 20th century, corpus linguistics—the study of authentic texts or speech acts made by language communities—demonstrated, using very large quantities of text, that “meaning can be associated with a distinct formal patterning” [

29] ((p. 6); see also Stubbs [

30]). Thus, we have a three-way correlation in which the patterns of wording found in the texts of green business correlate with their organizational practices which, in turn, provide us with insights into the meaning which this group of social actors assigns to a particular word. One can identify both how green businesses are starting to practice sustainability and how they understand the term.

4. Method

A more comprehensive account of the method can be found in previously published work [

31,

32] as, in the interests of brevity, just a brief overview is provided here. The selection criterion for what qualified as a British sustainable corporation was public membership of the World Business Council for Sustainable Development [

33] and/or the UN Global Compact [

34]. The first stage of the methodology was to build a database of texts that were representative of this community of practice and this was done by copying material down from the websites of the 25 businesses identified and saving it as txt files. In searching for distinctive patterns of wording in a body of texts, it is necessary to have a point of comparison and two references were set up. The first was publically available; the British National Corpus (BNC) [

35]. BNC had several advantages as a benchmark. First, it was created by a group of highly-respected project partners, that included the British Library Research and Development Department, Oxford University Computing Services, Lancaster University, Oxford University Press, and Longman Group Ltd. Second, since one of its design goals was to construct a language corpus typical of British English, it provided a very good match for British sustainable businesses; national differences in the usage of the English language could be eliminated as a possible variable. A third advantage with the BNC was its ready availability. Finally, its very large size, 90 million words, provided confidence that it was representative of typical English, against which other databases could be compared.

The second point of comparison was a database composed of texts written by British social and environmental NGOs; 37 in total. In designing language databases that are to be compared, there are two mutually exclusive design objectives which must be reconciled as best one can. On the one hand, it is important that each body of texts is representative of the organizations that have provided the material. On the other hand, one wants to be able to compare the texts of the two databases, with a view to saying something interesting about them. If the communities of practice that have produced the text have very different representations of experience, then one runs the risk of merely demonstrating that different people talk about different things. The compromise solution was to define, in advance of the text selection activity, what ideational content I was looking for in order for a text to be downloaded into its respective database (see Brown [

31] for a more detailed treatment of this process).

The PC program I used is called Wordsmith and is marketed by Oxford University Press [

36]. The author of the software has published work that describes the linguistic phenomena which Wordsmith can identify [

37]. There are also many previous studies that have used a similar keyword approach to that presented in this article [

38,

39,

40,

41]. In its first processing of the texts of the two communities—sustainable businesses and the environmental NGOs—it made a list of words that appeared in each of the two sample databases, ranking them in order of frequency. A moment’s reflection is all that is necessary to realize that the most frequently used words in any wordlist are ones that we all use: “the, and, a, of, but”

etc. and that these simple frequency-based word lists were of no value. However, Wordsmith then compared the two frequency-based word lists in turn with the corresponding reference list for the benchmark of “typical English” provided by the BNC, which also ranks words such as “the, and, a, of, but”

etc. as the most frequent. This first comparison procedure generated a list of statistical keywords, ranking highest those words that appeared much more frequently in the green business and environmental NGO word lists than when they were used in the “typical English” of the BNC.

The first running of this process produced two keyword lists in which the representation of sustainability management was recognizable. However, Wordsmith is simply a very fast counting machine and, lacking any form of human intelligence, it records the appearance of absolutely everything in the texts. Consequently, this first processing included keywords that were statistically key to these environmental reports but not semantically significant to the process of identifying the representations of managing-for-sustainability practice. A cleaning up procedure was necessary in order to remove different categories of these uninformative keywords. Examples included proper nouns (Shell, Rio Tinto, GreenPeace, Africa, US, Doha), units of measurement (tonnes, GWH, litres), products and materials (gasoline, platinum, bauxite), acronyms (ACCP, WBCSD), and terms referring to the internal organization of reports (appendix, pdf, section). The top 20 key words used by the green businesses in their representations of management-for-sustainability practice are presented in

Table 1 to give an impression of the results from this mechanistic process. The Wordsmith software generates the keyness value shown in the table. It is an indicator of how much more frequent the usage of a word is, compared with its usage in the benchmark database. The value 1.0 would indicate that it is no more frequent, so one can see that keyness values in the tens of thousands indicate that these particular terms are used massively more often by sustainable business than is the case for “typical English”.

Table 1.

The top twenty one-word keywords used by sustainable business.

Table 1.

The top twenty one-word keywords used by sustainable business.

| Sustainable Business—the Top 20 One-Word Keywords |

|---|

| N | Keyword | Keyness | N | Keyword | Keyness |

|---|

| 1 | ENVIRONMENTAL | 50,282.01 | 11 | ENVIRONMENT | 17,173.10 |

| 2 | BUSINESS | 33,236.84 | 12 | BIODIVERSITY | 17,137.79 |

| 3 | ENERGY | 32,561.70 | 13 | COMPANIES | 16,551.74 |

| 4 | SUSTAINABLE | 28,694.50 | 14 | DEVELOPMENT | 15,605.07 |

| 5 | EMISSIONS | 27,957.12 | 15 | GLOBAL | 15,575.64 |

| 6 | EMPLOYEES | 21,345.17 | 16 | REPORT | 15,331.68 |

| 7 | SAFETY | 21,059.48 | 17 | STAKEHOLDERS | 15,162.41 |

| 8 | MANAGEMENT | 20,525.46 | 18 | GROUP | 14,986.09 |

| 9 | WASTE | 19,852.47 | 19 | CORPORATE | 14,716.54 |

| 10 | PERFORMANCE | 19,044.42 | 20 | OPERATIONS | 14,448.74 |

Table 1 presents just the top 20 keywords of green business in a list that extends to several hundred whose keyness is statistically very significant. For example, the 500th most key word for sustainable business: wetlands, had a keyness of over 1000 in comparison with the “typical English” of the BNC. Using the same process, I also generated keyword lists for the top 100 two-word and top 50 three-word keywords. The top 20 of these keywords are presented in

Table 2.

Table 2.

The top twenty two- and three-word keywords used by sustainable business.

Table 2.

The top twenty two- and three-word keywords used by sustainable business.

| Sustainable Business—the Top Twenty Two-Word and Three-Word Keywords |

|---|

| N | Keyword | Keyness | N | Keyword | Keyness |

|---|

| 1 | SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT | 18,026.69 | 11 | GROUP COMPANIES | 4885.16 |

| 2 | HEALTH AND SAFETY | 9373.65 | 12 | HIV AIDS | 4822.87 |

| 3 | CLIMATE CHANGE | 8229.32 | 13 | CORPORATE SOCIAL | 4781.19 |

| 4 | ENVIRONMENTAL PERFORMANCE | 7138.26 | 14 | ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL | 4558.15 |

| 5 | CORPORATE RESPONSIBILITY | 7077.07 | 15 | BEST PRACTICE | 4237.95 |

| 6 | ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT | 6598.33 | 16 | MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS | 4156.79 |

| 7 | BUSINESS PRINCIPLES | 6256.01 | 17 | CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY | 4134.68 |

| 8 | GREENHOUSE GAS | 5405.60 | 18 | NATURAL GAS | 4090.75 |

| 9 | ENERGY EFFICIENCY | 5316,.6 | 19 | RESPONSIBILITY REPORT | 3804.73 |

| 10 | SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY | 5283.72 | 20 | HUMAN RIGHTS | 3798.92 |

At this point in the method, the search technique changed from Wordsmith’s efficient but mechanistic process to a humanly slow, hopefully intelligent and certainly interpretive approach. These lists of the top 500 one-word, top 100 two-word and top 50 three-word keywords of green business and the environmental NGOs became the objects of study for identifying groups of words that shared certain semantic similarities, some of which I report in the findings.

The first hypothesis that I proposed involved representations of (i) the natural landscape and (for green business) (ii) representations of managing for sustainability in such locations. The first semantic search, therefore, was to look for words that made representations of some aspect of the natural landscape. Some of the words were easily identifiable—forest, for example—whereas others with a more ambiguous meaning were checked for their intended meaning. In order to do this, Wordsmith generated a list of 20 randomly picked occurrences of the word. From a careful reading of the context in which it was used, I interpreted the meaning. Using this technique, for example, the word

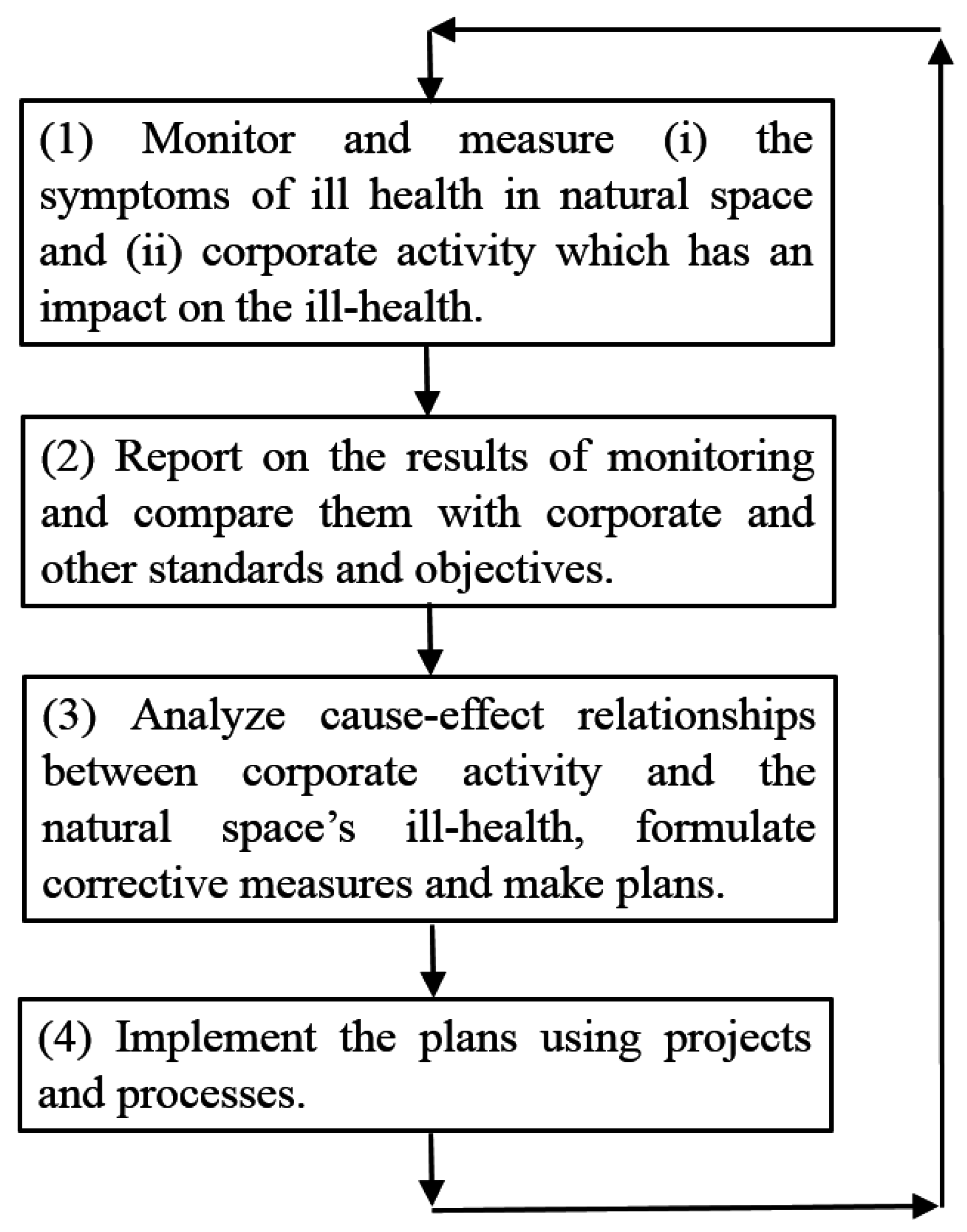

growth was not included in the semantic field of representations of natural space because it was clear that business used the word exclusively as a representation for economic expansion. Pursuing evidence to test part (ii) of the first hypothesis, the second search was to look for words that made representations of a process of management that might be applied to the natural landscape. As an aid to identifying the sorts of words for which I would be searching, I prepared a schematic describing the different stages of a process of operational management-for-sustainability. The schematic evolved out of my reading various environmental reports that were a part of the database the circular process of monitoring, reporting, analyzing, deciding, planning, and implementing is presented in

Figure 1. It functioned as a sort of “semantic template” as I searched through the two- and three-word keywords of sustainable business looking for representations of a process of management.

Figure 1.

A process of operational management for sustainability.

Figure 1.

A process of operational management for sustainability.

Summarizing, this procedure identified words in the green business database representing (i) the natural landscape and (ii) processes of operational management. The logical place to look for evidence that sustainable businesses might have started the process of managing the natural landscape, was where the words in category (i) functioned, grammatically as objects of the processes in (ii). Wordsmith has a function that enables one to study this phenomenon. It picks out 20 random occurrences of the same operator-selected word from the entire database. For each of the 20 occurrences it extracts the string of text in which the word appears with a cut off of 200 characters of text on each side of the selected word. This is normally sufficient contextualizing text for the operator to check for any possible ambiguities and confirm the writer’s intended meaning. This process is discussed further in the findings in which just such a problem is illustrated.

6. Discursive Interpretation

In this section, the linguistic findings are interpreted within corporate managing-for-sustainability practice in an attempt to flesh out its discourse. First, however, I need to make explicit the conceptualization of business corporations which is assumed in this interpretation. I conceive of them as being the business processes which are managed by the corporation’s officers. For example, I conceive of a sustainable MNC as a process engineer’s technical drawings, dictating the material and energy flows from which useful products are synthesized from raw materials; or as the financial controller’s spreadsheets modeling the flows of assets into, around and out of the P and L and balance sheet. In this particular understanding of the organization, free human agency and human moral consciousness have no role; the employees of the corporation are reduced to instruments who manage the execution of business processes. I shall return to this assumption in the closing section.

6.1. The Vantage Point from Which One Views the Natural Landscape Affects Its Representation

In their role of guardians of nature, the environmental NGOs are in the privileged position of being able to position themselves—rhetorically—within the natural landscape. From this local vantage point, they see the detail of the natural spaces and this accounts for representations such as crops, forest, soil, whale, and villagers that are reported in the findings. In the sustainability reports of green business, however, the natural spaces in which their operations are located are viewed from corporate headquarters, often on the other side of the globe. This affects the language of representation in two ways. First, there are so many natural spaces, corporate headquarters must aggregate them by making abstractions of their physical reality. Second, since the physical materiality of a particular location cannot be known by the corporation’s senior management at first hand, a form of representation of the natural space must be chosen that communicates meaningful information to these senior officers. At present, the meaningfulness has to be quantifiable. This is a “linguistic” discourse that is understood within the corporation and connects with the next point.

6.2. Centralized Management Systems Require Numbers to Be Able to Manage

In order for a global enterprise to manage its far-flung operations effectively from HQ, it has its own internal models of the different installations. For example, the mining company’s primary concentrator, which operates in the sand dunes running along South Africa’s Atlantic coast, is controlled from a head office in central London. Day-to-day operational control is under the local plant manager and her engineers, but she reports the key numbers back to London on a regular basis in a spreadsheet. These numbers provide senior management with a sufficiently detailed representation of the complex physical materiality of the primary concentrator. At HQ they are compared in the spreadsheet with the expected year-to-date numbers and any variations are analyzed before instructions are sent back to South Africa. In short, the corporation’s productive installations are operationally managed from headquarters using numbers.

Confirming one of the conclusions of Bansal and Knox-Hayes ([

42] p. 77), if the MNC now commits itself to becoming a sustainable MNC, it is likely to utilize its existing management processes in its attempts to manage for sustainability. In order to be able to manage them, the natural spaces—just like the MNC’s productive installations—need to be represented in a set of key numbers that can be recorded in a spreadsheet so that comparisons can be made between actual and expected year-to-date, variations analyzed, and new instructions issued to the local manager. This interpretation accounts for the second type of representation of nature that was presented in the findings; a vocabulary for being managed. Words such as

habitats,

sites,

areas, and

communities have the advantage—for an MNC—of being quantifiable.

Returning to the mining company’s challenge, the unique physical materiality of the natural space around the primary concentrator is represented, for example, as a habitat. Within the MNC’s corporate model, the habitat is “understood” by a selection of key measurements; its area, the air quality measured daily at specific GPS coordinates, a series of biodiversity indicators etc. These are measured, recorded in the spreadsheet and, along with the production numbers for the concentrator, communicated back to London where they can be analyzed, decisions made, instructions issued, and action taken. One way, then, in which green corporations relate to natural spaces in their managing-for-sustainability project, is by constructing representations of nature that can be incorporated within a spreadsheet.

With its perception based on an admittedly limited range of indicators, green business is able to describe the health of a natural space. One might balk at the notion suggested in the previous section, that MNCs are engaging in a process of managing nature. However, such a response might be mitigated by changing the representation from the term management to nurturing or stewardship. Continued corporate practice and its study will help us understand which of the practices are desirable and clarify what meanings the green corporations are investing in sustainability through their actions.

6.3. Incorporating the Local within the Global?

The abstract “vocabulary for being managed” is not, necessarily, a sign that these global green businesses are wholly ignorant of the local natural landscape around their productive installations. Certainly, when examining the macro-level characteristics of their texts, I was unable to find natural language representations. However, they do occasionally focus their gaze on a particular, local, natural space. For example, in line 15 of the report for the usage of

habitats (

Table A1,

Appendix), the MNC describes its “employment of two rangers to help protect and enhance the wildlife habitats at our Musselburgh and Valleyfield ash lagoons”. Pursuing this line of inquiry, on the webpages of ScottishPower [

43], there are several natural representations of specific plants and animals, which belong to a particular habitat; not enough to register at the macro-level among the sustainable corporations’ keywords, but some nevertheless. This practice is an example of Crane

et al.’s idea [

44] of corporate ecological citizenship which “requires corporate managers to be “embedded” in local environments to foster sustainable behaviors” (p.95). The two rangers who are employed by ScottishPower to protect and enhance the wildlife habitats at the Musselburgh and Valleyfield ash lagoons might be considered as “embedded” in the ash lagoons. This idea raises the possibility that within an MNC, pockets of local sustainability practice might be established by the corporation.

Pursuing this idea further, one intuitive impression I have gained from reading the corporate environmental reports is of occasional sustainability projects that are spared from the “vocabulary-for-managing” representation. These projects appear to be characterized by their being selected and then presumably funded, from the very highest levels of the corporation. Another avenue for further research would be to test for the existence of such a category of project. The working hypothesis is that corporate managing-for-sustainability practice might be divided into different categories. One category, following the main findings of this article, could be called operational sustainability practice. These would be all of the practices that are the consequences of the green corporation seeking to maintain a sustainable balance between its particular business operations and the natural landscapes around them. Their representation in reports would be characterized by the managerial vocabulary presented in this article. A second category, which might be called intrinsic sustainability practice, would be interventions in natural space that were not necessarily related to specific business processes but which the MNC, nevertheless, wished to implement. The representations of these projects might not be reduced to a language that Bell and Morse [

17] characterize as having “quantification at its heart” (p. 42). The study of such projects in managing-for-sustainability business practice might point the way to finding practices that can know the local natural landscape in a more holistic way than the managerial techniques that are in evidence in these findings.

In closing this interpretive section, I revisit my assumed conceptualization of an MNC as different business processes from which human agency and moral consciousness are absent. In this article, I have referred to

nature,

natural space, and the

natural landscape while deliberately avoiding using the term

place. Without wishing to appear to be summarizing a very large debate, one generally-agreed distinction between

space and

place is the role of human sense-making in the latter. Place “has a history and meaning. Place incarnates the experiences and aspirations of a people. Place is not only a fact to be explained in the broader frame of space, but it is also a reality to be clarified and understood from the perspective of the people who have given it meaning” ([

45], p. 387). Following Tuan, and assuming the conceptualization of an MNC that I advanced at the start of this section, when the sustainable corporation implements its operational managing-for-sustainability practices, the best we can get is a mechanistic sensitivity to natural space. Some researchers have argued that one promising avenue towards sustainability is for global MNCs to make a transition towards a place-based sensitivity to the natural landscape [

46]. The process of knowing place is a practice that I think belongs in the Milne and Gray project for growing

ecological literacy [

5]. My tentative response to this challenge is that the MNC needs to find a way in which its business processes merge with its human stakeholders’ moral consciousness so that the corporation can truly be said to give meaning to natural spaces in the construction of meaningful places.

7. Limitations and Future Research

It is, perhaps, not surprising that some form of direct management of nature will be a part of the sustainability response by these natural resource extraction companies. It is harder to imagine that an international bank’s environmental reports would have so much focus on managing natural space. Further work needs to be done to find out how generalizable these findings are.

A second limitation is that the companies that were selected to be representatives of sustainable business were selected, because they had made a commitment to working towards a sustainable future. Making a commitment to a goal, however, is not the same as successful, authentic practice. A great deal of research using different methodologies for measuring sustainability practice in different types of organizations must be done in order to test the managing-nature hypothesis.

The third limitation concerns a distinction between operational, as opposed to strategic, management processes. There is no space here to do more than point out the general organizational challenge of making connections between the two, both in theory and practice. Non-alignment between the corporation’s strategic objectives and its Performance Management System (PMS) has been a recognized phenomenon in the literature for over 40 years [

47]. Business-as-usual strategic goals are usually fairly easy to articulate, so the focus is normally on bringing the PMS into alignment with long term strategy. In contrast, managing-for-sustainability strategic models are, as mentioned in the introduction, only vaguely understood [

6]. Recognizing that nature itself is in a constant state of flux, the likelihood is that long-term models of the sustainable firm will co-evolve with changing natural landscapes [

48]. It is at this stage, therefore, very difficult to ascertain with certainty if the sort of findings identified in this article—where we are—help or hinder a corporation’s transition to more strategically-sustainable forms of operation and organization.