1. Introduction

The idea of sustainability is by the very idea of its trisection (see, for instance, [

1,

2]) an interdisciplinary construct. Even if the roots of the concept are found in the forestry by Hans Carl von Carlowitz in the Sylvicultura oeconomica 1713 [

3], the question of whether or not a single scientific discipline is able to solve the challenges of sustainable development seems obsolete. An interdisciplinary linkage, which in its necessity is unmistakable, should be expedited in the present paper.

The topic of social justice has been discussed in both economic and educational contexts. In the economic sciences, the rising pressure placed on companies by increasing public expectations during the last few decades has caused a discussion on the sustainable behavior of companies. This has resulted, for instance, in the sustainability concept of Elkington’s [

1] Triple Bottom Line. Sustainability concepts are justified in general by the changing role of the companies. They have gone from being responsible solely for their own profit to being responsible to society with a focus on social aspects of business activity and thereby touching upon the social impact of entrepreneurial activities.

Additionally, many social justice theories are based on economic considerations (see [

4]). In the field of educational sciences, on the other hand, education has been understood as being closely related to issues of social justice for a long time [

5,

6,

7,

8]. This discipline considers the idea of social justice by education, offering promotion prospects irrespective of an individual’s social background.

The purpose of this paper is to define and substantiate the relevance of educational sciences for the sustainable development of the economy and society under a new perspective. Therefore, the reader is asked to, at least, question the matching of sustainability and capitalism (in its present form). It is a premise of this paper to understand it not as a paradigm, that sustainable development has to be realized without major changes in present economic systems.

Education in the context of this paper means the product of the societal education system and its institutions such as schools, universities, and companies with a focus on adult education. It does not mean parenting as part of raising a child or socialization. It should be understood as a design element of a sustainable society beyond isolated considerations of sustainable education concepts (regarding the long-term success of educational measures) or education for sustainable behavior (which means sustainability as the content of educational measures). The understanding of education as design system is based on Luhmann’s [

9] system-theoretical description of educational systems, describing the educational system as a societal sub-system with education as the specific product. Thereby, it may produce sustainability education, but it also has to be designed on the premise of a sustainable society. This is valid for all sustainability dimensions, yet it seems to be most essential for social sustainability since education is a social action and is oriented on social premises. Luhmann’s theory of social systems is based on the perspective on society as a system, which is defined by an environment and interacting elements (see, for instance, [

9,

10,

11]). As such, it will be necessary to identify overlaps and interdependencies between sustainability and educationally related research and concepts. Consequently, the functional link of education and sustainability that, for example, would be the education for sustainable behavior, is not discussed. For the discussion of education as an instrument of sustainable development, the description of the connection between sustainability and education will be sufficient. Indeed, the normative-theoretical linkage will be considered via a hermeneutic-analytical approach. This normative link is the basis for interdependent and interdisciplinary concepts and elucidates the equivalence of sustainability and education goals. In this manner, the foundation for a praxis-oriented linking of both areas will be created. This may result in the connection of sustainability-oriented and education-related design systems in organizations, e.g., of Corporate Social Responsibility and Human Resource Development. In a wider view, this will also be a step in defining those aspects of capitalism that are barriers for sustainable development.

Since social justice is postulated a priori as the link for this approach, it will be the focus of the following considerations. It will become obvious that existing social justice theories are useful, in general, but need modifications in order to be connected to education and sustainability and to serve as a link for both. These modifications will be designed basically.

Furthermore, new implications for research in the field of social sustainability will result. This addresses an urgent problem since sustainability and sustainable development have been considered mainly within an ecological or economic perspective. By linking social sustainability with social justice, a valid theoretical reference is employed to design and measure social sustainability related measures and engagements. Likewise, the connection of education and social justice is useful to design concepts and concrete measures in order to oppose injustices in society by educational means. In conclusion, the conjunction of social sustainability, social justice, and educational sciences will result in the identification of synergetic and interdependent aspects. This process thusly defines developments and deducts measures and concepts to support socially sustainable development and social justice within the economy and society. Since this paper will not provide a holistic synergy for the sustainability concept and educational sciences, it may be understood as a basis for discussion and further concretization of the issue. The following questions will be explicitly addressed:

- (1)

How can the concept of sustainability, especially social sustainability, be linked with theories of social justice?

- (2)

What may be the linkage between educational sciences and social justice?

- (3)

What are the aspects and determinants of such a linkage?

To address these questions, this article has been built into three parts. First, the concepts will be described separately. Second, the connections between sustainability and social justice and between educational science and social justice will be described. And third, based on this framework, the role of social justice as a link between sustainability and educational science will be discussed.

2. The State of Research

By researching and analyzing the literature regarding sustainability, it becomes obvious that the different aspects of sustainability are drawing different levels of attention in the research. There is a strong focus on ecological and environmental issues (for example, Elkington defines the health of the global eco system as the “ultimate bottom line” [

1] (p. 73)) (see, for instance, [

1,

12]), and, in contrast, relatively little research on the societal aspects of sustainability and hence on social responsibility (see, for instance, [

13,

14]). This focus can even be traced back to the origins of the political sustainability discussion and the Brundtland Commission [

15].

Social justice is mostly addressed by philosophy and social sciences (see, for instance, [

4,

16,

17]). Currently, most research regarding social justice is linked with other issues of social relevance. As a result, the focus is on migration and gender research (see, for instance, [

8,

18]). The resulting insights of this specific research seem to be extendable to a perspective on society as a whole, for the founding theories are not specific to particular aspects of social fields. Instead, they address generated suggestions that are also applicable in a broader perspective. Moreover, many scientific contributions on social justice refer to discussions and critics of the term and concept itself rather than providing suggestions on how social justice could be implemented in society.

3. Sustainability as a Claim of the 21st Century Society

Since the term society has already been and will furthermore be a descriptive reference for this paper’s argumentation, a working definition is necessary. This task seems to be challenging because a limitation of the term towards national societies is too narrow. After all, issues like globalization and environmental protection forbid a focus on single nations. The expansion towards a global society, on the other hand, seems to be too wide as we keep the very different social and economic conditions of different regions of the world in mind. A suitable definition is somewhere between these two perspectives and does not have to be clear at this point. This is because the argumentation is not limited to national circumstances and does not need an adaption on global level to work. Society is therefore functionally defined according to Luhmann [

11] as this social system that embraces all societal sub systems like education, economics, and politics.

Sustainability concepts address urgent global problems in the areas of environment, economics, and social issues such as global warming or infant mortality in the third world and are therefore designed as business paradigm for the 21st century. The wide range of sustainability concepts, the different foci and perspectives, and especially the lack of unified global sustainability theories make the linking of sustainability with other theories and concepts complicated. In the following argumentation, the definition of the Brundtland Commission will be fundamental, postulating sustainability as the principle of ensuring that the actions of present generations “do not limit the range of economic, social, and environmental options open to future generations” [

15] (p. 43). Furthermore, the tripartite dimension of economic, ecologic, and social sustainability is considered to be essential, as it has been developed in scientific and political discussion (see, for instance, [

19]) and has been concretized by different authors. It is henceforth referred to as the “triple bottom line concept” of Elkington [

1], which understands the three dimensions as being on an equal footing. This concept has been especially designed as a business guideline to promote the implementation of sustainable development. These particular sustainability dimensions are considered to be interdependent since society depends on the economy, and the economy depends on the global eco-system. The dimensions are not stable but in a constant state of flux due to social, political, economic and environmental influences. This makes the handling of sustainability completely more challenging than the simple sum of the bottom lines in isolation [

1] (p.73). In the following discourse, the dimensions are also understood as super-ordinated action systems wherein concrete approaches and developed measures have to be located in order to define clear sustainability goals and outcomes resulting from them. With the focus on the social dimension, the specific abilities of this dimension are described and also discussed as the linking points with the other theories.

It also has to be mentioned that the triple bottom line concept is not without limitations. It is criticized mostly for not hierarchizing or weighting the dimensions. This is because it seems implausible that ecology should be addressed with the same priority as economics and society if the environment is to be understood as the basis for all societal development and has therefore to be prioritized [

20,

21]. Another problem is the vague possibility of operationalizing indicators for sustainability, among other reasons, because of the undefined relations between the dimensions [

22]. Both points of criticism are relevant for this paper because a lack of concreteness also hampers the ability to link the concept with other theories. However, with a focus on the isolated dimension of social sustainability, these limitations do not affect the argumentation since the relations of social sustainability with the other dimensions will not be discussed as a part of the link so far.

In 2050, earth’s population will exceed 9 billion people. If those people demand resources similar to our needs, this will only be successfully managed with a focus on sustainability and sustainable development [

23] (p. 8). To amplify the concept of sustainability, sustainable development is understood as development “that meets the needs of the present world without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” [

1] (p. 55), [

15] (p. 1). Similarly, sustainable development means the process of society’s change towards sustainability while sustainability means the final state [

24]. The supreme goal of capitalism and consumer society, which is in substance the constant acceleration of production, consumption, and economic outcomes without limits, is considering this fact grossly unsustainable [

14] (p. 682). It is becoming more and more the expectation of Western societies that business (for this paper, the term

business is used as term for a latent construct covering the manifest constructs of corporations as organizations and their activities.) has to take responsibility for the world and interregional problems. In this context, it seems necessary to clarify that it appears wrong to make business generally responsible for all societal problems and especially for slow sustainable development. However, business is an essential institutional player in the design of a society’s economic system. Furthermore, it can be assumed that business is motivated to keep this economic system as long it is a profiteer of the said implemented order. As a consequence, criticism concerning a lack of sustainability within a society has to address business particularly. Even so, other societal actors like the state or the citizens, especially in their role as consumers, have to take responsibility for sustainable development as well.

Subsequently the question is no longer whether companies should accept this responsibility or not; it is now rather a question of conversion and realization [

12] (p. 17f.). Additionally, for its own benefits, business needs stable markets that themselves need conflict-free environments [

1] (p. 20). This is particularly true since conflict-free environments seem to be closely related to the demand of socially stable environments. Since sustainability is becoming an issue not only of special interest groups but also for the majority of society, the social dimension of society is gaining in importance.

4. Social Sustainability as an Economic Issue—The Third Bottom Line

Social sustainability regards a society or a state that is organized in a way where social tensions do not escalate but are solved in a peaceful way [

25]. Elkington deduces this social dimension of sustainability from the concept of social capital, which is equal to human capital in the form of public health, skills, and education. Also included are wider measures such as society’s health and wealth-creating potential [

1] (p. 85), [

26]. Such is the basis for an additional differentiation of this dimension in specifying social capital by its focus on the individual or with a focus on the society as a whole [

1] (p. 84), [

27]. This kind of categorization is needed because measures addressing individuals might interfere with the benefit of society and

vice versa. In this case, the primacy of what sustainability demands has to be considered as well as if the disadvantages being out of the perspective with the other values justify this primacy. In addition, the linkage to other societal constructs and theories (like social justice) will be normatively and functionally different with the focus on individuals or on society as a whole. Thus, we have a distinction between subject-perspective and societal perspective.

Social capital involves norms, social networks, moral obligations, social values, and trust [

8] (p. 287), [

27]. According to Fukuyama [

28], this capital arises from the prevalence of trust in a society and depends on their capability and a measure of the people’s ability to work in groups to reach common goals. Social capital is considered to be critical to sustainability transition and can be developed at every level of society as from international institutions down to family units and single persons [

1] (pp. 84ff.). This form of capital is therefore essential to the promotion of civil society [

8] (p. 287). Additionally, the degree of trust, e.g., between a society and its government or a corporation and its stakeholders, is a key factor that determines social sustainability. Sustainable development itself is most likely done and achieved with the lowest costs in societies with a high level of trust and other forms of social capital. This situation again depends on the levels and equity of investment in social capital, which means investing in education, health, and nutrition [

1] (p. 85). In a logical conclusion, this means that social sustainability is not only a part but is also a driver of sustainable development and therefore takes on a double role that the other dimensions of sustainability are not serving.

A possible threat to social engagement concepts is the ambition to design ways to control people’s minds and hearts. This would reduce the idea of sustainability to an approach for raising productivity and profit [

1] (p. 87). Moreover, greening, which means the implementation of measures for the improvement of environmental or social situations, has to be prohibited. These are often only short-termed and punctuated activities and should therefore not be considered indicators for the real responsible behavior of companies (see, for instance, [

12] (pp. 66f.), [

29]. Instead, a deep and revolutionary process of transforming the moral order has to be undertaken to reach real social sustainability, which “means the radical redefinition of the social contract between business and society” [

1] (p. 142). It would be the wrong approach to reduce social responsibility engagement to temporary, isolated activities. This would bring on the threat of a superficial implementation of the sustainability concept to appease stakeholders without internalizing it in the corporation. More generally, it might be stated that sustainability may only be implemented successfully if the implementation itself is sustainable, so it needs to be understood as a trend and not a temporary management fashion. This outcome might be prevented by engaging not only in projects or by implementing sustainability-related structures in corporations such as reporting-systems,

etc. However, this must be done by working towards a fundamental shift in the understanding of corporations and the economy [

12] (p. 32).

According to Elkington [

1], most business organizations are developing well in the economic and environmental sustainability dimensions, but the social dimension is still underattended and underdeveloped. Genuine sustainability demands economic and environmental aspects but also must handle questions of poverty alleviation, population stabilization, female empowerment, employment creation, human rights observance, and opportunity redistribution [

1] (p. 141), [

30]. Opportunity redistribution is especially an aspect of this argumentation. In the context of education, opportunity distribution employs an inter-generation perspective, because it can be stated that, normally, the level of education is shared from parents to children. This effect has been pointed out by the national reports on education for Germany [

31,

32]. In other words, the higher the parent’s level of education, the higher the children’s level will be. This problem is addressed with the connection of social justice and education in the second part of the paper.

5. Social Justice as a Scientific Challenge

The question of the ethical foundation of a society has challenged mankind since the dawn of civilization. With the origin of classical philosophy in Greece, the idea of social justice has become a central element of these reflections (see, for instance, [

33]). In the argumentation of this paper, the concept is used as link between educational sciences and sustainability. This possibility becomes obvious when the conceptual proximity and relation between social justice and social sustainability are explained in the following section.

Social justice is a contested research field [

34]. In general, it can be defined as the state of a society when the distribution of rights, opportunities and resources can be rated as just. The accurate definition of justice is thereby not clear and remains an issue of vagueness and dispute in political and scientific discussion [

35] (p. 3). The concept of social justice is a normative basis for the social market economy. Thereby, a close relation of the idea to economic considerations becomes obvious. In the sense of ordo-liberalism, justice means ensuring individual civil rights and liberties, ensuring real possibilities for a self-responsible shaping of life, and ensuring the minimization of constraining situations in economic activities. As a result, the possibilities and chances for the individual to achieve self-fulfillment are in the focus of this approach [

36] (p. 274). A direct reference to society as a whole is not provided by ordo-liberal principles. Its key point is the granting of freedom, ignoring the question of whether or not individual freedom might cause social injustice. Another concern is to ask if socially strong groups or individuals might dominate the socially weak groups or individuals without restriction (this might be considered a weak point for all social justice approaches with an exclusive reference to the individual level and not embedded in the perspective of the societal system as a whole). Hecker [

36] (p. 274) goes on to name three aspects of social justice: performance-related justice which is granted by the market mechanisms (this, of course, necessitates the assumption that market processes are, in principle, just - an assumption that might be doubted and whose verification depends on the definition of social justice) and equal opportunity and needs-based justice which both have to be granted by legal regulation. Performance-related justice is only given if inequalities solely depend on inequalities of performance and the relations of competition among the members of a reference group [

36] ( p. 275). The inequalities of economic starting and inherited wealth by birthright seem to be supremely unjust indeed [

37] (p. 96). This idea basically implies that, in liberal societies, real social justice cannot be reached according to the current understanding of property, a thesis that has to be considered when exploring normative links to the sustainability concept.

6. Social Justice, Economics, and Social Sustainability

An adequate theory of social justice is only possible by making claims about fundamental entitlements that are to some extent independent of individual preferences. This is because preferences are often shaped in the context of an unjust background condition [

38] (p. 34). In other words, social justice is not a subjective condition but is built by the capabilities that everyone of a specified reference group (regional, national or international context) has (this does not necessarily interfere with the assumption that being part of a socially just environment may be considered a subjective impression depending on the education, cognitive aspects, and social status of the individual). This finding becomes more important because, as Nussbaum [

38] (p. 36) further postulates, social justice is essentially subjective and caused by the heterogeneity of society. This heterogeneity causes a difference in the resources needed by every individual to reach the same condition as other individuals. For instance, invalids need other supplements than healthy persons to feel well, and pregnant women need more nutrition than non-pregnant women to stay healthy. The equality of capabilities has therefore to be the highest standard of claiming social justice within a society [

38] (p. 36).

For the connection of sustainability and social justice, different social approaches have to be considered and discussed since their specific perspectives and limitations provide important factors for the link. Distributive justice is a claim of the sustainability concept regarding the social bottom line. According to [

4], distributive justice tries to solve the justice problem by defining what has to be distributed by whom towards whom and in which way. The clear definition of these four basic variables remains an unsolved problem for philosophy and politics. This challenge should result in an explicit examination of stakeholders in socially disadvantaged sections of the population. These individuals may have relatively little participation in market transactions because of insufficient financial resources and may therefore be left outside the focus of corporations [

39].

Sustainability is also closely related to the idea of intergenerational justice, meaning that every generation has to solve their problems instead of leaving them for future generations (since generations do not follow successively one after another but overlap each other, this definition might lack concreteness. Thus, it cannot be easily defined which generation is responsible for which particular problems. The better definition might be that every generation has a responsibility to solve existing problems and to prevent future problems by all available means). This idea of justice is also valid within the same generation because every human being must be given the possibility to live in decent conditions. This postulation defines the human individual as the center of all reflections [

40] (p. 28), which is a conformity of the nature of modern pedagogics as well as the social justice approach of Amartya Sen.

According to Sen [

41], social justice is based on the capabilities approach. The central question of this concept is as such: What capabilities does a person need to achieve a successful life? This idea connects social justice closely with personal freedom because social justice with regard to equality of opportunity and capability is essential for the individual exercise of freedom. Indeed, development as freedom is an essential aspect of Sen’s theory [

38] (p. 33). Sen [

42] is stating that utility is not the purpose of development, but development is the basis for freedom. Furthermore, individual development is the result of capabilities. In Sen’s argumentation, utility is not adequate to capture the heterogeneity and incommensurability of the different aspects of development such as health or education. These entities are lowly correlated to figures of utilized development like a state’s gross domestic product. Consequently, the goal of development has to be a state or condition of persons (in other words, the object of the social justice capability approach is the individual and his/her development, not the distribution of economic power. This is especially worth considering with regard to the argumentative limits of distributive justice mentioned above.). In theory, no quantitative definition of capabilities is available. As a result, it cannot be stated what minimum level of capabilities a society needs to be just [

38] (p. 35).

Implementing social justice, regardless of the concrete approach, has diverse challenges and problems. In considering the linkage with the sustainability concept, these have to be discussed since they usually hamper the deduction of concepts and measures or the implementation of possible measures as well. This brings us to a crucial consideration: the social justice idea gains in complexity since the growth of individualism is contrary to the policies of equity and social justice [

8] (p. 1). It has been shown that immobility is essential for the reproduction of social inequalities, which is contingent on geographies of power that are located within the connections and disconnections among the global, national and local levels. Thus, it is considered to be the interest of powerful societal groups to fix other groups in less powerful spaces. As such, less powerful groups learn to accept their social position rather than learning how to become more empowered within their societies [

43] (p. 647). It might appear that the unequal participation of non-traditional students in education, for example, is traceable back to individual choice. Yet, when we consider these essential mechanisms, it becomes obvious as an indicator for social injustice (social injustice is in this paper simply referred to the state of absence of social justice in the reference group or reference system) and as an example for overestimating the meaning of making free choices [

44]. The availability and achievability of choices are determined by social structures. Access to learning has to be understood in relation to structures of inequality, which are deeply embedded in society and social structures [

45]. These circumstances have to be considered since they are by nature barriers in the societal structure that stand in the way of individual self-fulfillment. Thus, they become potential action fields of engagement for socially sustainable development.

Social sustainability can be regarded as a requirement for social justice and vice versa. Social justice has to be implemented on a long-term basis, and hence, a sustainable perspective and social sustainability may only be reached when perceived as provisions for a just society. After all, this may be a relevant aspect for long-term acceptance by the society as a whole.

7. Social Justice and Education

In the educational sciences, especially inequalities and capabilities in education are a topic that is closely related to social justice. Studies on inequalities in education show ambivalent results since there are both studies that show a decrease of inequality as well as some that show an increase [

29,

46,

47]. Explanations of educational inequalities are given through diverse approaches. The most popular are the culture-theoretical approach of Bourdieu and the decision-theoretical approach of rational choice theory [

48,

49,

50]. There is empirical evidence that social inequality is caused by transition processes in the educational system. Factors for this are (a) the family context, which mostly means children in families in educationally deprived strata of society [

46]; (b) gender-specific differences [

51]; (c) the social background that influences school performance and where it can be stated that parents might support the learning and competence-building of their children if they are capable of achieving better cultural capital [

52,

53,

54]; and (d) migration background since young people from immigrant families have greater problems in attaining apprenticeship positions [

55].

Central topics of social justice are educational opportunities, migration, and gender [

38] (p. 33), [

18]. Thus, it has become mostly a topic of recognizing demographic groups or minorities that are discriminated against. These groups can become isolated and silenced in the society system, and this may lead to oppression and the need to follow the claims of more powerful groups [

56]. Therefore, inclusion and equality in this context are often taken in the meaning of the individual’s movement between social groups [

8] (p. 4). Pedagogy can counter this social condition by enabling socially disadvantaged individuals to reflect upon their oppression. It has been designed according to this concept by Freire [

5] (p. 25). Freire’s pedagogy is closely connected to issues of oppression and social justice and being aware that education can become a means of oppression and for enforcing social injustice within a society [

8] (p. 4). Some determinants of social injustice that can be addressed by education are language, literacy, and literary practices [

6] (pp. 184ff.). Especially via language, individuals can achieve a sense of identity. By claiming or reclaiming language, people achieve the skills to critically reflect upon experiences and transfer them into personal development. Yet, although the acquisition of key basic skills and qualifications is necessary, it is not sufficient to reach social justice [

8] (p. 5).

Education is an important determinant of social justice, not only regarding formally qualifying graduations in early phases of life. The particular concept of lifelong learning is indivisibly related to this with respect to the need for and the right of education in every phase of an individual’s life [

8,

57]. Lifelong learning is of increasing relevance for educational science and as a concept to face the challenges of transforming society [

58] (p. 26), [

59] (p. 4). We must consider not only the economic but also the individual needs of lifetime education. The focus must be on compensating the tendencies of social injustice caused by the formal education system and the societal dynamics described above. Then, lifelong learning may be the central concept in addressing social justice with educational measures and, therefore, the most relevant concept for sustainable social development.

8. Normative Linkage

So far, it may already be summarized that the idea of social justice is connected to social sustainability and educational science and therefore enables the link between both. It further builds the basis and orientation for socially responsible action. Now, we should discuss which way the social justice concept has to be designed in order to build the link between sustainability and education. Principally, according to Sen’s [

41] capability approach, the opportunity distribution is relevant for this argumentation, but it has to be adapted in line with specific presumptions. While Sen [

41,

42] separates between the terms of opportunity and capability in the argumentation of his theory out of conceptual perspective, this separation is less relevant for the linkage of social sustainability with education. Assuming capabilities and opportunities both as individual dimensions of enablement means that some requirements are needed for an individual to carry out actions. Yet, their relation is irrelevant as long as the discourse is out of an effect-focused perspective. Capabilities and opportunities may be in a kind of hierarchical relationship, meaning that the presence of one depends in causality on the presence of the other, or both may have to be considered as quantities with an overlap. Either way, it is eventually about the individuals and for them the real possibilities for self-fulfillment activities. The congruency of capability and opportunity may be assumed equal to these possibilities for self-fulfillment activities. So far, a lack in capabilities may be considered just as restrictive for the individual’s development as a lack of opportunities. A separation of both factors becomes an important conceptual issue but has low relevance for discussing impact and target perspectives.

Since capabilities are different for individuals, according to Sen [

41], their adaption to a view on society as a whole through the social sustainability concept is limited. This is true as far as capabilities, and especially the resulting possibilities for self-fulfillment activities, are considered as finite quantities within a society and have therefore been distributed amongst the members of this society. Moreover, it has to be assumed that the subjective preconditions for capabilities are already a result of social disparity—for instance, this could be the case if individual demands for self-fulfillment are a result of its socialization and of the hierarchical order of societies. In this case, aspects of distribution are not to be ignored by discussing the connection of social sustainability and social justice.

In the context of educational sciences, in particular regarding the concept of lifelong learning, opportunity distribution can be considered intra- as well as inter-generational. This is because the acquirement of education not only affects the immediate individuals participating in it but also their children indirectly, depending on their level of education [

31,

32]. This interpretation is closely related to the idea of intergenerational justice, as is sustainability, which is by nature linked to the intergenerational perspective [

15].

The concept of distributive justice is also adequate for issues of social responsibility in the context of education and regarding the connection to social sustainability because of its perspective on society as a whole and its egalitarian idea of justice. This circumstance further shows the limitations of the distributive approach, because, by the egalitarian alignment, the distributive justice approach ignores subjective differences of individuals’ needs. This limitation is explicitly addressed by the capability approach. Therefore, we have the idea of distribution of possibilities along with the capability to use possibilities, as far as both approaches reflect on risks and chances via education and understanding education as resources for personal development. These may be two complementary approaches of social justice for the normative link with social sustainability and education. Instead of a clear separation, the complementary use of both approaches might be reasonable if based on the assumption that a holistic view on social justice needs both a societal and a subjective perspective. Social justice consequently has to be referred to in relation to subjects and society. The explanations above have shown that the capabilities approach focuses on the individual, whereas the distribution approach focuses on the society as a whole. Due to the current lack of a more issue-specific approach to social justice in this argumentation, justified by the explanations above, the capabilities approach is given precedence in this argumentation.

Social justice has to be implemented on a long-term, and thereby sustainable, perspective, and social sustainability may only be reached when perceived as providing social justice for a society. This argument is based on the assumption that, within a free society, long-term stability may only be reached when all members of society experience minimal divergence between their claims and the actual arrangement of the societal system. This state might be reached when the societal system is socially just. This may be the relevant aspect for long-term acceptance of social conditions or of a paradigm shift by the majority of society. According to Jackson [

8], social injustice is, for instance, the result of impermeable social classes, and respectively, the inability of individuals to move between social groups. By promoting socially disadvantaged groups, this condition may be counteracted. Thusly, educational work is essential to provide the necessary knowledge and competences. Pedagogic work then becomes highly important to promote social justice and show the relevance of education for socially sustainable action. However, as Jackson [

8] pointed out, the acquisition of key basic skills and qualifications is a necessary precondition but not sufficient to reach socially just conditions.

As far as social justice is an object of this thesis, it cannot be understood as manifest state of a society that is present or is not. It rather has to be used as a scale defining a steady state between the idealistic (but most likely unrealistic) states of total social unjustness and total social justness. In contrast, to measure a society or parts of a societal system according to their social justness on such a scale, specific conditions of societies or societal subsystems like companies may be on a level of lowest resolution being dichotomously stated as just or unjust. This consideration seems to be important to gain clarity on how social responsibility activities and engagement with the social sustainability dimension by a corporation may address issues of social justice. Through this assumption, it is logical that the social engagement of a company is well able to address particular social situations or conditions in turning them from unjust to just and raise the scale level of social justice in a society.

An essential difference between social sustainability and social justice can be determined with respect to the temporal perspective. Whether social justice inherits intra- and intergenerational considerations, the sustainability concept is, by nature, oriented to questions of intergenerational development. Thereby, the need to link the idea of social sustainability with other concepts is reasoned due to the lack of urgency for solely intergenerational issues in the individual perspective on the one hand, and the difficulty of their concretization for engagement on the other. Considering sustainability to be an intergenerational perspective might be adequate, but for social justice, the inter- and intragenerational perspectives are not consequently separable. It seems implausible that, in itself, an unjust societal system can be assumed just in relation to future generations and subsequently in its determination of future societal environments. In its trivial consequence, presence is the reference for assessing social sustainability in relation to social justice.

9. Discussion

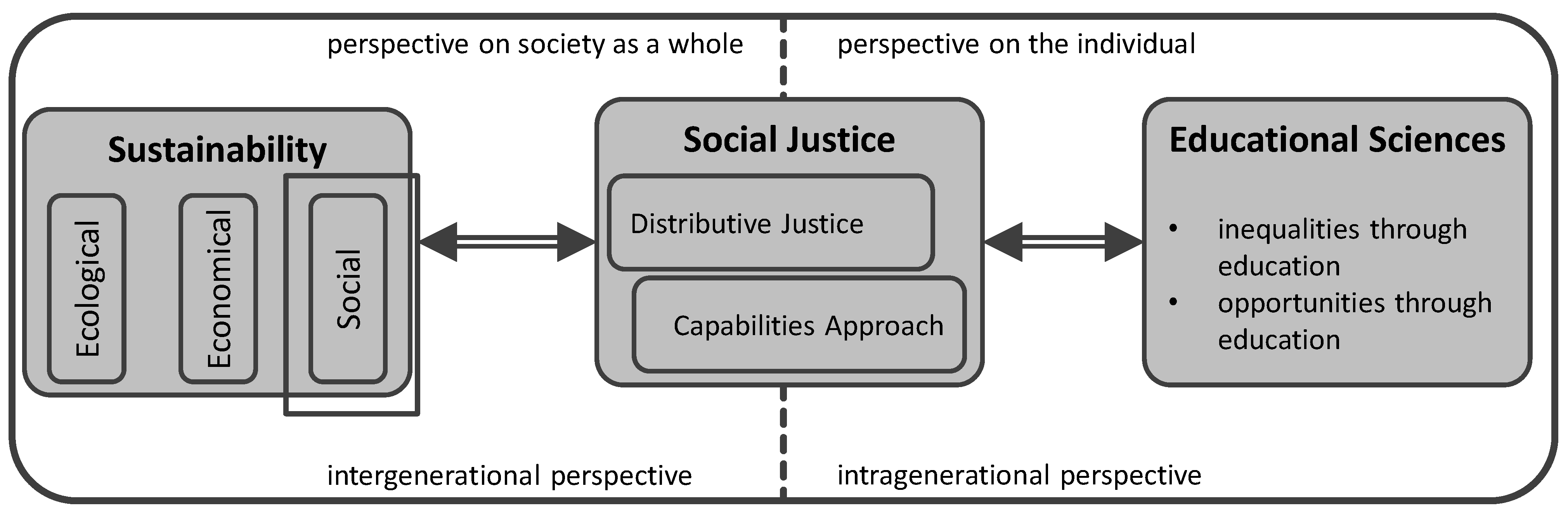

A theoretical-normative linkage of the design systems has been shown to be a complex approach with manifold facets to consider. In this regard, the concepts of social sustainability as part of the tripartite sustainability model, the social justice theory of the capabilities approach, and the distributive approach along with the role of the educational sciences have been discussed. Social sustainability and social justice have been assumed to be interdependent if not even symbiotic. The educational sciences are addressing issues of social justice by discussing inequalities in educational possibilities and as a way of promoting educational behavior and opportunities for socially disadvantaged groups. The description of the normative linkage according to the explanations above is summarized in

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Diagram of the normative linkage of sustainability, social justice and educational sciences.

Figure 1.

Diagram of the normative linkage of sustainability, social justice and educational sciences.

To define determinations of the proposed linkage, it has been stated that social sustainability inherits both a perspective on the individual and on the society as a whole [

1]. Both perspectives are reconcilable with the linkage with social justice and education theories, although the capabilities approach and most educational concepts are oriented to the individual level. Furthermore, although the focus of sustainability concepts seems to be on an intergenerational perspective and, therefore, for the linkage, on intergenerational justice, the consequent separation of the perspective from intragenerational problems seems doubtful. As a last main thesis, it has been assumed that, for a consistent functional deduction of the linkage on the normative level, an operationalization of social justice has to be prepared. This must be done in order to gain a social-justice construct that can be evaluated in terms of social-sustainability development. Hence, the definition and operationalization of relevant parameters seem useful as a method that might be applicable to different societal realms.

Thereby, the chosen theories are considered to be purposeful for the theoretical linking of sustainability and educational sciences. After all, both the individual and the societal perspectives imply not merely a connection but rather complementary objectives and approaches. Elkington’s triple bottom line concept is designed for applicability to a business context, yet it is, in most aspects, unspecific. Both are good criteria for the contention of this paper because this work is not intended to be part of the discussion of the sustainability idea itself but should build a basis for further deduction of reference frameworks and application concepts. On the other hand, it is not targeted for a specific purpose in a way that its linking with social justice and education might be restricted. Regarding the social justice approaches, it might seem that only socially disadvantaged groups are an object of reflection for social justice and also for social sustainability. However, this might be only one part of the needed perspective. In addition, above-average privileged groups and their role in socially sustainable development need to be discussed in the future.

A problem for the implementation of sustainable development with a social focus is the threat of reducing the sustainability concept. This reduction may be, in the best case, the understanding of sustainability as an entrepreneurial performance criterion. In addition, in the worst case, it may be seen as a marketing activity. Of course, to cope with the primacy of capitalism, the sustainability idea has to be made tempting for corporations in the form of sustainable economic management concepts that offer competitive advantages and business benefits. This reduction of the sustainability idea, which should concern societal development as a whole is necessary. This is because it can offer the chance to realize sustainable development in the current societal system and economic culture. This constraint inherits an aporia that endangers the sustainable implementation of sustainable development itself.

As a concluding discussion, the question of the addressed societal target state has yet to be answered, especially because both sustainability and social justice are ideas that seem to be immanent in the demand for societal change. We may define the design of society as its structure, based on generally accepted standards and values that themselves manifest in societal sub-systems and social structures; this design has to be oriented on two premises. For one, we have the idea of sustainability and on the other side, social justice with a minimum of social inequality. This might result in a maximum of personal freedom for the members of society without endangering the same possibilities for other societies or future generations. This concept, of course, is no operationalized target. It is more accurate about the idea in which this paper’s proposals are embedded.

10. Conclusions and Outlook

After we have characterized relevant theories and their relations and connections with each other, the normative linkage of all has been designed as a framework. This framework defines the specific criteria by which interdependencies and overlaps of sustainability and education can be identified. Regarding social justice, it has been shown that nearly all approaches address the question of how just or unjust the social situation of poor, respectively socially disadvantaged groups of society are. Neglected is the question of how just or unjust the privileging of a societal minority has to be defined and what impact this has on social sustainability. This question seems to be interesting as far as capabilities for living chances are considered to be a finite set of possibilities. It implies, that every living chance an individual exploits is no longer available for other individuals. This also means that opportunities for societally privileged groups have to be reduced in order to provide these to other members of society. This assumes a finitude of possibilities that is ignored by the capabilities approach so far but is part of the distribution approach.

Currently, there is no education-specific concept of social justice. This kind of approach might be useful as far as education as a societal resource seems hard to compare with other material or immaterial economic or societal resources. In a knowledge-based society, it can be assumed that unequal access to education results in social injustice. This is because education is an essential factor in the acquisition of economic capital and in the realization of living chances beyond economic issues. Therefore, this might be a current desiderate for social and educational science.

By approaching linkages of the sustainability concept with other concepts and theories, the lack of a holistic sustainability theory becomes obvious. Even with the already valid approaches (for instance, [

1]), an interdisciplinary connection is difficult since economic and ecological perspectives essentially influence the understanding(s) of sustainability.

In the next phase of this research, practice-related deductions could be valuable. These may be conducted in the form of concretized design systems or frameworks. These can offer the possibility of creating measures to address social sustainability by organizations. Hence, organization-related concepts of the three design systems have to be identified where they are already manifest and institutionalized in the organizations in order to find a practice-related link.

To conclude the presented implications, the need of a paradigm change in capitalist economies in general and in companies, in particular, should be emphasized. This change must be forced by changes in society and regarding the new global problems [

1,

12]. In consequence, there needs to be a change in the understanding of the economy’s character and its relation to society. For the paradigm change, society cannot be understood as an instrument to secure the existence of the economy, but the economy should be understood as an instrument to secure the existence and prosperity of society. As such, societal goals and interests have to be superior to entrepreneurial objectives.

Furthermore, a society that is socially just has to offer every one of its members the capabilities to reach his individual vision of life through his own performance [

36] (p. 275). The overall question in this context remains if economic principles themselves are just. This might subsequently question the justness of the societal system as a whole, since the role of companies is in the original understanding of capitalism a selfish one. For a long time, their role in society has been reduced to reaching profit maximization, and this has been widely accepted. However, to face our urgent global problems, the very nature of capitalism has to change in order to reach sustainability. Economic, ecological, and social damage resulting from business activities have to be considered and prevented by the companies themselves. The future development of capitalism becomes especially urgent since a shift in international power can be recognized as caused by the globalization of economies with transnational corporations becoming more powerful and individual nations tending to lose power [

1] (pp. 24ff.), [

12] (p. 18). Currently, it cannot be estimated whether or not capitalism is able to become sustainable or not. However, enterprises might evolve in this direction by public and regulatory pressure. During the transition of sustainability, some industries will probably be destroyed, and others will be forced into radical restructuring. Corporations have to become sustainable or they will fall before the challenges of the 21st century [

1] (pp. 35ff.). The linkage of the concept of sustainability with other disciplines, therefore, has to be the basis for a normative-theoretical framework in order to reveal and criticize the unsustainability of capitalism and understand and support these processes.