In Transition towards Sustainability: Bridging the Business and Education Sectors of Regional Centre of Expertise Greater Sendai Using Education for Sustainable Development-Based Social Learning

Abstract

:Nomenclature:

1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Background

2.1. The Sustainability Challenge in the Education and Business Sectors

2.2. Education and Learning for Sustainability in Schools and Companies

2.2.1. ESD

2.2.2. ESD and Business

2.2.3. ESD in Schools

2.2.4. Challenges Facing ESD Implementation

2.2.5. Partnerships and Collaboration

2.3. Learning and Social Learning: Capacity Building through ESD-Based Social Learning

2.3.1. Learning

2.3.2. Social Learning

2.4. Regional Centre of Expertise on ESD Greater Sendai (RCEGS)

3. Methods

4. Results

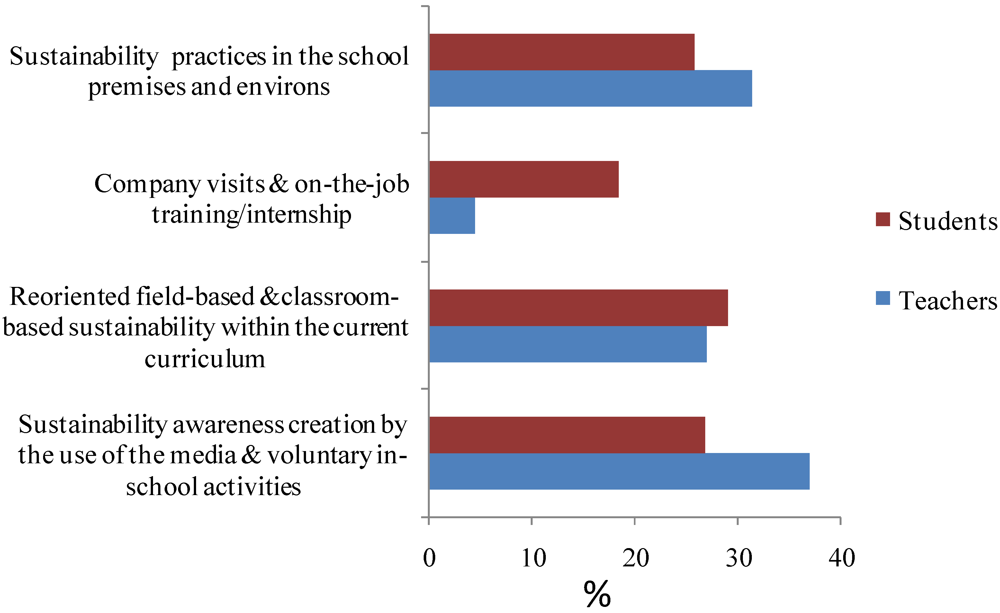

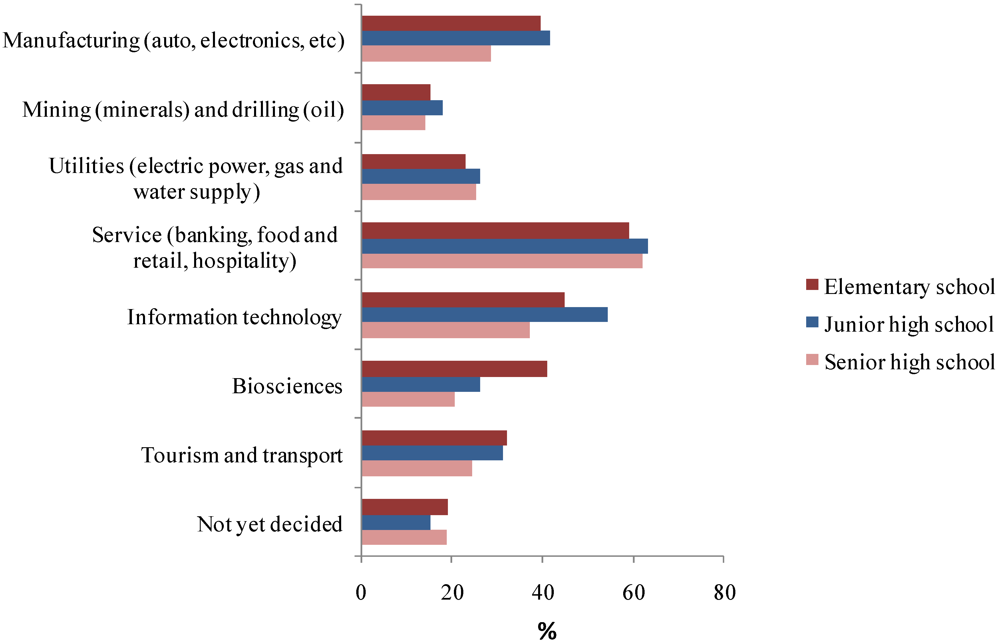

4.1. Enhancing Capacity at the Grassroots Using ESD-Based Social Learning through Collaboration between the Education and Business Sectors in RCEGS

4.1.1. ESD-Related Activities Students Participated in

| Activity | Students (n = 316) | |

|---|---|---|

| (a) | Visiting nature conservation museums | 32.0 |

| (b) | Preservation of local natural areas | 37.7 |

| (c) | Classroom-based school activity related to environmental sustainability | 27.5 |

| (d) | Participation in environmental club or other voluntary activities | 4.2 |

| (e) | Visit to a company to learn about its entire operations | 14.9 |

| (f) | Receiving short-term on-the-job training in environmental sustainability related to the company | 3.5 |

| (g) | Use of computers and the internet to learn and share environmental sustainability information | 32.0 |

| (h) | Engaging in sustainable practices in your school (e.g., separating garbage for recycling, water & energy reduction, cleaning the school and its environs) | 62.0 |

| (i) | Use of festivals, fairs, drama, documentaries, movies, etc . to develop sustainability awareness and knowledge | 19.6 |

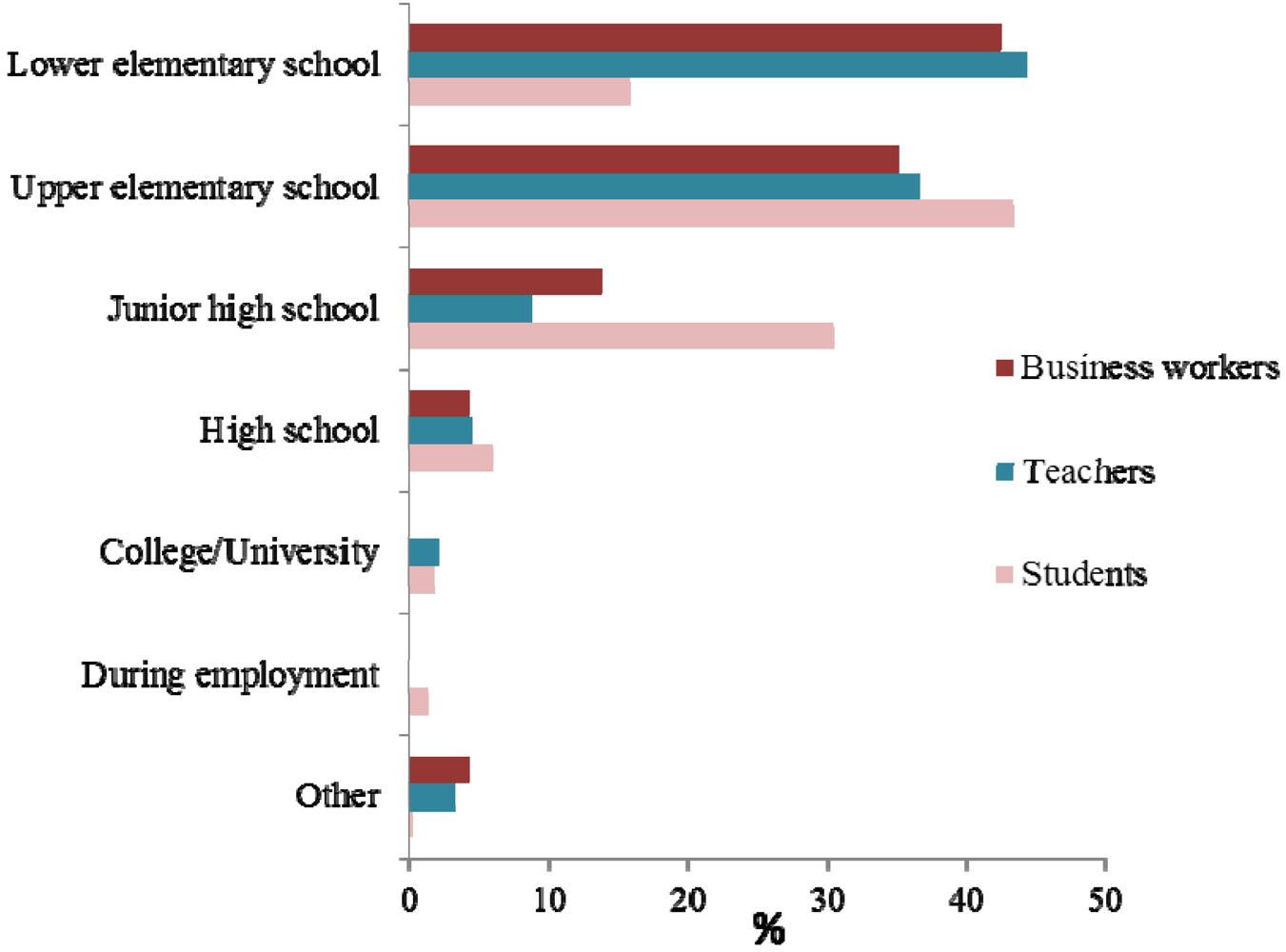

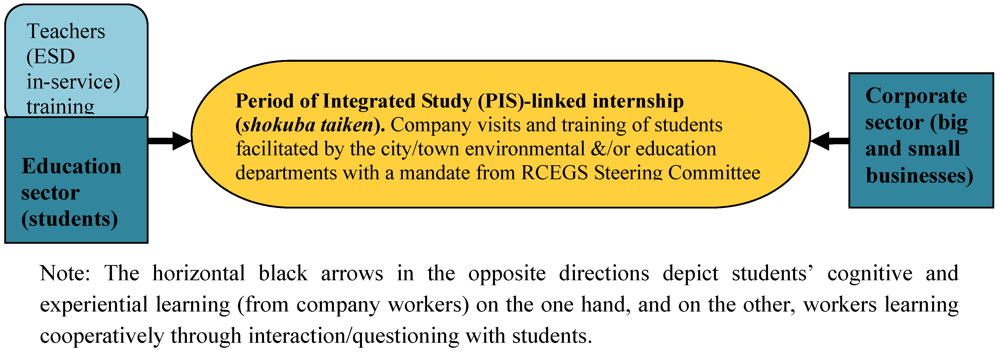

4.1.2. Company Visits and On-the-job Training (Internship) as Opportunities for Social Learning

5. Discussion

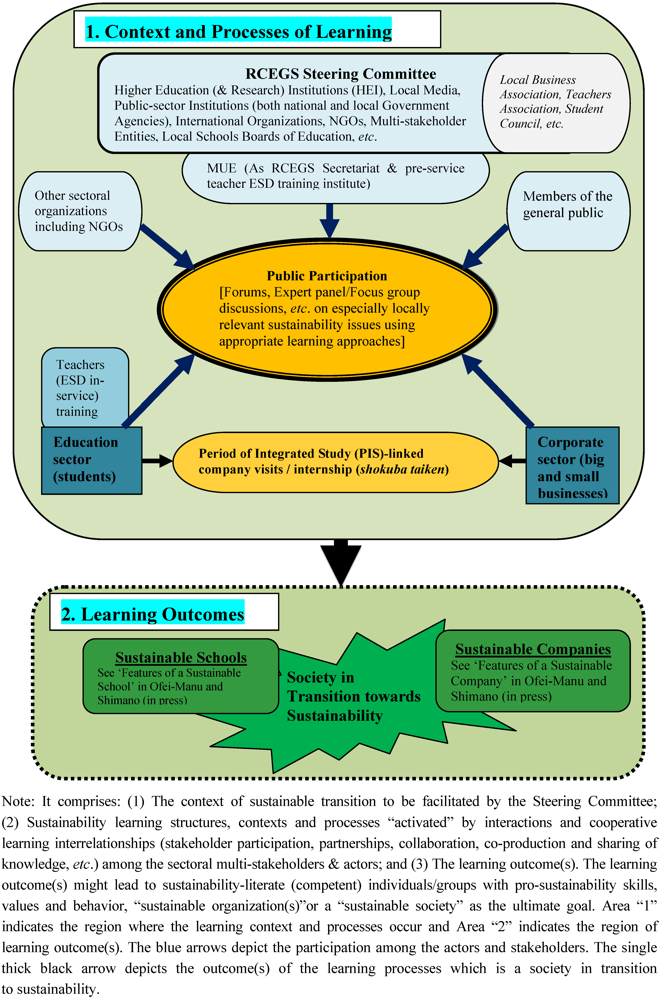

5.1. The ESD Structure/Context, Processes and Outcome(s) in RCEGS

- how the Steering Committee manages boundaries to determine those who are or are not involved in the process;

- the scope of participation of multi-stakeholder partnerships across sectors as the basis of inclusiveness and thus the possibility of overcoming a participation gap;

- the space given to boundary and bridging organizations regarding collaboration to incorporate their particular experiences of the creation of collective action for capacity building to adapt to change;

- effective coordination among team members and the leadership required to steer and coordinate the process and the type of strategies applied in the negotiation process;

- the laid-down rules established to facilitate interactions among the stakeholders;

- the involvement of the stakeholder in the process in terms of role and purpose;

- the structure of the internal capacity for interactions and the space given for democratic deliberations among social networks and in building social capital;

- how the existing culture exerts influence on the way the issues at stake are framed and defined;

- the processes in establishing managing systems of knowledge and making sense of information;

- building trust, caring for one another, nurturing shared commitment and providing the guarantee that the well-being of all stakeholders is taken into consideration;

5.2. Recommendations

“Fostering Closer Alliances, The government will promote ESD in primary and secondary schools and introduce it into teacher training courses and training programs for teachers when they renew teaching licenses. It will also take steps to promote joint community-school ESD initiatives, including school and community support headquarters and stakeholder conferences.” “At the community level, the government will support partnerships among and initiatives by individuals and organizations in the community, such as forums to promote ESD. It will also bolster ESD programs as well as the ESD promotion mechanism in public halls, civic centers, children’s centers, libraries, museums, and other social education facilities. Steps will be taken to train and deploy coordinators to promote ESD in the community” [85] (pp. 19–20).

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- Ofei-Manu, P.; Shimano, S. Sustainable organizations: Evaluating the environmental sustainability of schools and companies in a Regional Centre of Expertise. Int. J. Environ. Cult. Econ. Soc. Sustain. 2012, 7. in press. [Google Scholar]

- McKeown, R. Education for Sustainable Development Toolkit; Waste Management Research and Education Institution: Knoxville, TN, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner, R. Business Simulation for Education and Training on Sustainability Managemen. ISDRS Newsletter; ISDR Society: New York, NY, USA, 2011; Issue 1, pp. 19–21. Available online: http://isdrc17.ei.columbia.edu/sitefiles/file/isdrs%20Newsletter%201%202011%20.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2011).

- Sanusi, Z.A. The Role of the Regional Centre of Expertise in Human Resource Development for a Sustainable Society: “University of RCE”; RCE: Penang, Malaysia, 2010. Available online: http://www.unescobkk.org/fileadmin/user_upload/apeid/Conference/14th_Conference/docs/papers/Zainal_Sanusi_RCE_Penang_01.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2011).

- Richmond, M. ‘Envisioning, coordinating and implementing the UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development’ in UNESCO. In Tomorrow Today; Tudor Rose: Leicester, UK, 2010; pp. 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, I. Critical thinking, transformative learning, sustainability education and problem-based learning in universities. J. Transf. Educ. 2009, 7, 245–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilbury, D. Are we learning to change? Mapping global progress in ESD in the lead up to “Rio Plus 20”. Glob. Environ. Res. 2010, 15, 101–107. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, J. Environmental Management in Organizations: The IEMA Handbook; Earthscan: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hansmann, R. Sustainability learning: An introduction to the concept and its motivational aspects. Sustainability 2010, 2, 2873–2897. [Google Scholar]

- WCED (World Commission of Environment and Development), Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 1987.

- Lozano, R. Towards better embedding sustainability into companies’ systems: An analysis of voluntary corporate initiatives. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 25, 14–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano, R. Envisioning sustainability three-dimensionally. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1838–1846. [Google Scholar]

- Holden, M. The rhetoric of sustainability: Perversity, futility, jeopardy? Sustainability 2010, 2, 645–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czech, B.; Cleveland, J.C.; Victor, P. Steady state economy [3 Chapters]. Encyclopedia of Earth; Cleveland, C.J., Ed.; Trunity, Inc.: Newburyport, MA, USA, 2009. Available online: http://www.eoearth.org/article/Steady_state_economy (accessed on 8 January 2011).

- Nath, B. Japan education for sustainable development: The Johannesburg summit and beyond. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2003, 5, 231–254. [Google Scholar]

- Cato, M.S.; Myers, J. Education as re-embedding: Stroud communiversity, walking the land and the enduring spell of the sensuous. Sustainability 2011, 3, 51–68. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, A.D. The challenge of learning for sustainability: A prolegomenon to theory. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 2009, 16, 131–138. [Google Scholar]

- Landorf, H.; Doscher, S.; Rocco, T. Education for sustainable human development: Towards a definition. Theory. Res. Educ. 2008, 6, 221–236. [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES), Sustainable Asia 2005 and Beyond: In the Pursuit of Innovative Policies. IGES White Paper: Hayama, Japan, 2005.

- Hopkins, C.; McKeown, R.; van Ginkel, H. Challenges and roles for higher education in promoting sustainable development. Mobilizing for Education for Sustainable Development: Towards a Global Learning Space Based on Regional Centres of Expertise; Fadeeva, Z., Mochizuki, Y., Eds.; UNU/IAS: Yokohama, Japan, 2005; pp. 13–21. Available online: http://www.ias.unu.edu (accessed on 8 March 2009).

- Lenglet, F.; Fadeeva, Z.; Mochizuki, Y. ESD promises and challenges: Increasing its relevance. Global Environ. Res. 2010, 15, 95–99. [Google Scholar]

- Ofei-Manu, P.; Skerratt, G. Does the present concern and knowledge of environmental sustainability among business workers (in Greater Sendai Area RCE, Japan) reflect its occurrence in company publications? Environmentalist 2009, 88, 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ofei-Manu, P. Gender and environment in the Japanese workplace. J. Innov. Sustain. Dev. 2009, 4, 150–164. [Google Scholar]

- Netherwood, A. Environmental management systems. In Corporate Environmental Management: Systems and Strategies; Welford, R., Ed.; Earthscan: London, UK, 1998; pp. 37–60. [Google Scholar]

- De Haan, G.; Bormann, I.; Leicht, A. The midway point of the UN Decade for Education for Sustainable Development: Current research and practice. Int. Rev. Educ. 2010, 56, 199–206. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, K.; Tilbury, D. Whole-School Approaches to Sustainability: An International Review of Whole-School Sustainability Programs; Australian Research Institute in Education for Sustainability (ARIES): North Ryde, Australia, 2004; Report for The Department of the Environment and Heritage, Australian Government. Available online: http://www.aries.mq.edu.au/projects/whole school/files/international_review.pdf (accessed on 5 July 2012).

- Bourn, D. Education for sustainable development in the UK: Making the connections between the environment and development agendas. Theory Res. Educ. 2008, 6, 193–206. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, W.A.H. Judging the effectiveness of a sustainable school: A brief exploration of issues. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2009, 3, 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Wals, A. Learning our way to sustainability. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 5, 177–186. [Google Scholar]

- Ofei-Manu, P.; Shimano, S. Ramsar wetlands-rice paddies and the local citizens of Osaki-Tajiri area as a social-ecological system in the context of ESD and wetland CEPA. Global Environ. Res. 2010, 15, 95–106. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, D.; Nakayama, S. Drivers and barriers to implementing ESD with focus on UNESCO’s action and strategy goals for the second half of the Decade. Global Environ. Res. 2010, 15, 125–136. [Google Scholar]

- Filho, W.L. An overview of ESD in European countries: What is the role of national governments? Global Environ. Res. 2010, 15, 119–124. [Google Scholar]

- Slaus, I.; Jacobs, G. Human capital and sustainability. Sustainability 2011, 3, 97–154. [Google Scholar]

- Ekins, P. Environmental sustainability: From environmental valuation to the sustainability gap. Prog. Phy. Geo. 2011, 35, 629–651. [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco, P.; Motloch, J.; Vann, J. Second chance game: Local (university and community) partnerships for global awareness and responsibility. J. Clean. Prod. 2006, 14, 848–854. [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick, S.; Jones, S.; Mulford, B. Maturing School-Community Partnerships: Developing Learning Communities in Rural Australia; CRLRA Discussion Paper, University of Tasmania: Newnham, Australia, 2002.

- Gazley, B. Linking collaborative capacity to performance measurement in performance government—Nonprofit partnerships. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2010, 39, 653–673. [Google Scholar]

- Ngar-yin Mah, D.; Hills, P. Collaborative governance for sustainable development: Wind resource assessment in Xinjiang and Guangdong Provinces, China. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 20, 85–97. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A.; Kearins, K. Interorganizational collaboration for regional sustainability: What happens when organizational representatives come together? J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2011, 47, 168–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukman, R.; Krajnc, D.; Glavic, P. Fostering collaboration between universities regarding regional sustainability initiatives—The University of Maribor. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 1143–1153. [Google Scholar]

- Senge, P.; Smith, B.; Kruschwitz, N.; Laur, J.; Schley, S. The Necessary Revolution: Working Together to Create A Sustainable World; Broadway Books: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pinkse, J.; Kolk, A. Addressing the climate change-sustainable development nexus: The role of multistakeholder partnerships. Bus. Soc. 2012, 51, 176–210. [Google Scholar]

- Scales, P.C.; Foster, K.C.; Mannes, M.; Horst, M.A.; Pinto, K.C.; Rutherford, A. School-business partnerships, developmental assets, and positive outcomes among urban high school students: A mixed-methods study. Urban Educ. 2005, 40, 144–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R. Developing collaborative and sustainable organizations. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 499–509. [Google Scholar]

- Armitage, D.; Marschke, M.; Plummer, R. Adaptive co-management and the paradox of learning. Global Environ. Change 2008, 18, 86–98. [Google Scholar]

- Garmendia, E.; Stagl, S. Public participation for sustainability and social learning: Concepts and lessons from three case studies in Europe. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 1712–1722. [Google Scholar]

- Senge, P.M. The Fifth Discipline: The Art of Practice and Learning Organization; Doubleday Business: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Senge, P.; Scharmer, C.O.; Jaworski, J.; Flowers, B.S. Presence: Human Purposes and the Field of the Future; Crown Business: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick, S.; Bell, R.; Falk, I. The role of group learning in building social capital. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 1999, 51, 129–144. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.N. Compass and Gyroscope: Integrating Science and Politics for the Environment; Island: Washington, DC, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson-Palombo, C.; Gebremichael, M. Creating a learning organization to promote sustainable water resource management in Ethiopia. J. Sustain. Educ. 2012, 3. Available online: http://www.jsedimensions.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/Atkinson-PalomboGebremichaelJSE20121.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2012).

- Scott, W.A.H.; Gough, S.R. Sustainability, learning and capability: Exploring questions of balance. Sustainability 2010, 2, 3735–37463. [Google Scholar]

- Tàbara, J.D.; Pahl-Wostl, C. Sustainability learning in natural resource use and management. Ecol. Soc. 2007, 12 Article 3. [Google Scholar]

- Pahl-Wostl, C.; Mostert, E.; Tàbara, D. The growing importance of social learning in water resources management and sustainability science. Ecol. Soc. 2008, 13 Article 24. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, M.S.; Evely, A.C.; Cundill, G.; Fazey, I.; Glass, J.; Laing, A.; Newig, J.; Parrish, B.; Prell, C.; Raymond, C.; Stringer, L.C. What is social learning? Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15 Article 1. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, J. The Sustainability Mirage-Illusion and Reality in the Coming War on Climate Change; Earthscan: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pahl-Wostl, C. The importance of social learning in restoring the multi-functionality of rivers and floodplains. Ecol. Soc. 2006, 11 Article 10. [Google Scholar]

- Pahl-Wostl, C.; Craps, M.; Dewulf, A.; Mostert, E.; Tabara, D.; Taillieu, T. Social learning and water resources management. Ecol. Soc. 2007, 12 Article 5. [Google Scholar]

- Folke, C.; Colding, J.; Berkes, F. Synthesis: Building resilience and adaptive capacity in social-ecological systems. In Navigating Social-Ecological Systems: Building Resilience for Complexity and Change; Berkes, F., Colding, J., Folke, C., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003; pp. 352–387. [Google Scholar]

- Milbrath, L.W. Envisioning a Sustainable Society: Learning Our Way Out; State University of New York Press: Albany, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshizumi, M.; Miyaguchi, T. Realizing education for sustainable development in Japan: The case study of Nishinomiya City. Curr. Issues Comp. Educ. 2005, 7, 104–113. [Google Scholar]

- Oikawa, Y. Developing and implementing an inquiry based global environmental education program of Omose elementary school through collaboration with community, specialist organization and American school. Proceedings of UNESCO/JAPAN Asia Pacific Environmental Education Research Seminar,2004. Available online: http://www.eec.miyakyo-u.ac.jp/APEID2004/pdf/Oikawa.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2012).

- Hirayama, K. Corporate environmental education in Japan: Current situation and problems. Int. Rev. Environ. Strateg. 2003, 4, 55–93. [Google Scholar]

- Lotz-Sisitka, H.; O’Donoghue, R.; Wilmot, D. The Makana Regional Centre of expertise: Experiments in social learning. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 1, 73–92. [Google Scholar]

- White, P.; Petry, R. Building regional capacity for sustainable development through an ESD project inventory in RCE Saskatchewan, Canada. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 5, 89–100. [Google Scholar]

- Mochizuki, Y.; Fadeeva, Z. Regional Centres of Expertise on sustainable development (RCEs): And overview. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2008, 9, 369–384. [Google Scholar]

- Fadeeva, Z.; van Ginkel, H.; Suzuki, K. Regional Centers of Expertise on Education for sustainable development: Concepts and issues. In Mobilizing for Education for Sustainable Development: Towards a Global Learning Space Based on Regional Centres of Expertise; Fadeeva, Z., Mochizuki, Y., Eds.; UNU/IAS: Yokohama, Japan, 2005; pp. 22–28. [Google Scholar]

- UNU-IAS (United Nations University-Institute of Advanced Studies), Five Years of Regional Centres of Expertise on ESD; UNU-IAS: Yokohama, Japan, 2010.

- Ofei-Manu, P.; Skerratt, G. The current level of concern and knowledge of environmental sustainability (ES) is a reflection of its marginalization from the core school curriculum and by the media in Japan. Int. J. Environ. Cult. Econ. Soc. Sustain. 2009, 5, 15–34. [Google Scholar]

- Miyake, H. Public participation in environmental education: Prospects of Asian countries through Japanese experience. Proceedings of Kitakyushu Initiative Seminar on Public Participation, Kitakyushu, Japan, 2004; 2004. Available online: http://kitakyushu.iges.or.jp/docs/mtgs/seminars/theme/pp/Presentations/4_Modes/UKitakyushu.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2012).

- Mochizuki, Y. Articulating a Global Vision in Local Terms: A Case Study of a Regional Centre of Expertise on Education for Sustainable Development (RCE) in the Greater Sendai Area of Japan; UNU-IAS: Yokohama, Japan, 2006. Available online: http://www.ias.unu.edu/binaries2/IASWorkingPaper139.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2010).

- Ledwith, M.; Springett, J. Participatory Practice: Community-Based Action for Transformative Change; The Policy Press: Portland, OR, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart, M.; Wallis, E. Partnership approaches to learning: A seven-country study. Eur. J. Indus. Rel. 2007, 13, 301–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halog, A.; Manik, Y. Advancing integrated systems modeling framework for life cycle sustainability assessment. Sustainability 2011, 3, 469–499. [Google Scholar]

- Keen, M.; Brown, V.A.; Dyball, R. Social Learning in Environmental Management: Towards a Sustainable Future; Earthscan: Sterling, VA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Tippert, J.; Searle, B.; Pahl-Wostl, C.; Rees., Y. Social learning in public participation in river basin management. Environ. Sci. Pol. 2005, 8, 287–299. [Google Scholar]

- Mostert, E.; Pahl-Wostl, C.; Rees, Y.; Searle, B.; Tábara, D.; Tippet, J. Social learning in European river basin management; barriers and fostering mechanisms from 10 river basins. Ecol. Soc. 2007, 12 Article 19. [Google Scholar]

- Frasera, E.D.G.; Dougilla, A.J.; Mabeeb, W.E.; Reeda, M.A.; Patrick, M. Bottom up and top down: Analysis of participatory processes for sustainability indicator identification as a pathway to community empowerment and sustainable environmental management. J. Environ. Manag. 2006, 78, 114–127. [Google Scholar]

- Eisler, R. The Power of Partnership: Seven Relationships that Will Change Your Life; New World Library: Novato, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fadeeva, Z. Promise of sustainability collaboration—Potential fulfilled? J. Clean. Prod. 2004, 13, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattie, J. Visible Learning: A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement; Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Koganezawa, T. Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) at Teachers Universities; UNESCO: Bangkok, Thailand, 2010. Available online: http://www.unescobkk.org/fileadmin/user_upload/apeid/Conference/14th_Conference/docs/papers/940-230-1-DR_01.pdf (accessed on 29 May 2011).

- Fadeeva, Z.; Mochizuki, Y. Regional Centres of Expertise: Innovative networking for education for sustainable development. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2007, 1, 229–237. [Google Scholar]

- Folke, C.; Hahn, T.; Olsson, P.; Norberg, J. Adaptive governance of social-ecological systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2005, 30, 441–473. [Google Scholar]

- Establishing Enriched Learning through Participation and Partnership Among Diverse Actors; Government of Japan: Tokyo, Japan, 2009; UNDESD Japan Report. Available online: http://www.env.go.jp/en/policy/edu/undesd/report.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2012).

© 2012 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Ofei-Manu, P.; Shimano, S. In Transition towards Sustainability: Bridging the Business and Education Sectors of Regional Centre of Expertise Greater Sendai Using Education for Sustainable Development-Based Social Learning. Sustainability 2012, 4, 1619-1644. https://doi.org/10.3390/su4071619

Ofei-Manu P, Shimano S. In Transition towards Sustainability: Bridging the Business and Education Sectors of Regional Centre of Expertise Greater Sendai Using Education for Sustainable Development-Based Social Learning. Sustainability. 2012; 4(7):1619-1644. https://doi.org/10.3390/su4071619

Chicago/Turabian StyleOfei-Manu, Paul, and Satoshi Shimano. 2012. "In Transition towards Sustainability: Bridging the Business and Education Sectors of Regional Centre of Expertise Greater Sendai Using Education for Sustainable Development-Based Social Learning" Sustainability 4, no. 7: 1619-1644. https://doi.org/10.3390/su4071619

APA StyleOfei-Manu, P., & Shimano, S. (2012). In Transition towards Sustainability: Bridging the Business and Education Sectors of Regional Centre of Expertise Greater Sendai Using Education for Sustainable Development-Based Social Learning. Sustainability, 4(7), 1619-1644. https://doi.org/10.3390/su4071619