1. Introduction

With the ongoing deepening of China’s rural revitalization strategy, the cultural and creative industries are increasingly becoming a core engine for stimulating rural endogenous motivation and promoting industrial optimization and upgrading [

1,

2]. Globally, the deep integration of culture, creativity, and local development has emerged as a significant trend in rural revival, as evidenced by initiatives such as the EU’s LEADER program, Japan’s “One Village, One Product” movement, and South Korea’s “Sixth Industrialization of Agriculture.” These examples demonstrate that activating local cultural resources is a crucial pathway toward achieving sustainable and inclusive rural development [

3,

4]. In this process, the unique cultural heritage accumulated in China’s rural areas—specifically, the agricultural civilization system that carries historical memory, local knowledge, and ecological wisdom—constitutes its distinctive and irreplicable “cultural DNA,” setting it apart from urban cultural and creative practices. How to effectively transform this profound cultural resource into a new productive force driving rural development (i.e., “rural innovation”) through creative design and technological means, thereby achieving a positive interaction between cultural continuity and economic revitalization, has become a critical issue of common concern in both domestic and international academic and practical circles [

5,

6].

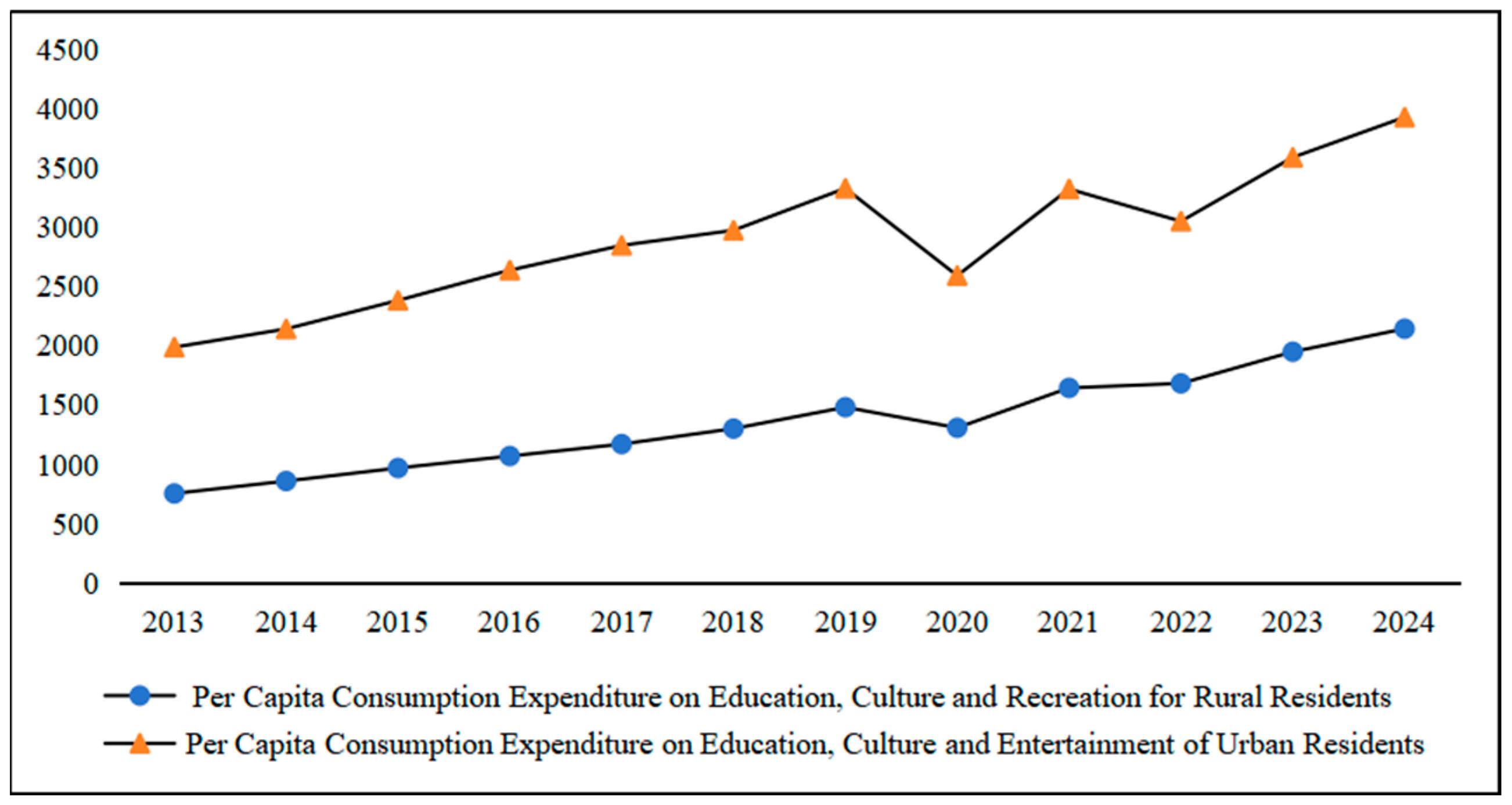

The rise in rural cultural and creative industries is underpinned by a market demonstrating both breadth and dynamic growth. As illustrated in

Figure 1, per capita expenditure on education, culture, and entertainment among rural residents in China surged from 754.61 yuan in 2013 to 2144 yuan in 2024, representing a striking increase of 184%—significantly outpacing the 98% growth recorded in urban areas. This trajectory not only underscores the substantial potential and vitality embedded within the rural cultural consumption market but also mirrors an elevated demand for spiritual and cultural enrichment among rural populations. Nevertheless, a nuanced examination reveals that, by 2024, rural per capita spending in this category remained at only 54.6% of the urban level. This persistent disparity highlights structural gaps in the cultivation of rural cultural markets and points to the pressing need for more targeted institutional and policy interventions. Rather than merely indicating a deficit, however, this gap also delineates a considerable scope for future expansion, suggesting that the rural cultural economy resides in a phase of accelerated catch-up growth. Such a context invites further scholarly attention to the mechanisms through which latent demand can be translated into sustained market development and equitable cultural participation.

Despite the promising prospects, many rural areas still face the structural dilemma of a “dormant cultural context” and “silent rural innovation”. Rich cultural heritage often exists in fragmented forms, making it difficult to form systematic contemporary narratives and industrial value [

7,

8]. At the same time, brain drain and a lack of capital lead to insufficient endogenous motivation in rural areas, causing externally implanted cultural and creative projects to easily become short-lived “isolated landscapes.” To resolve the paradox of “abundant cultural resources but weak industrial transformation,” there is an urgent need to explore a localized path that can effectively activate cultural genes and achieve sustainable development [

9]. Against this backdrop, the practice of Jiande City in Zhejiang Province provides a valuable county-level case study. Leveraging the opportunities presented by Zhejiang Province’s “Cultural Gene Activation Project” and “Artistic Rural Construction” initiatives, Jiande City has drawn upon the distinctive landscapes and cultural heritage of the upper Qiantang River region to systematically explore diverse models for revitalizing rural areas through cultural and creative industries [

10]. From the integrated development of agriculture, culture, and tourism in “Strawberry Town” and “Rice Fragrance Town” to the successful operation of the “139 Homestay” brand in Hangtou Town, Jiande’s practice demonstrates that cultural context is far from a static heritage. Rather, through creative transformation and innovative development, it can evolve into a high-level production factor that drives endogenous rural growth.

Based on the author’s tracking research conducted in Jiande City from 2021 to 2024, this study adopts a mixed-methods approach that integrates literature analysis, case study, participatory observation, in-depth interviews, and focus group discussions. Literature analysis was employed to systematically review policies and theoretical frameworks in rural revitalization and cultural innovation. Using the case study method, typical towns and villages—including Meicheng Town—were selected for multi-site fieldwork and in-depth analysis. Throughout the research process, the author immersed themselves deeply in local cultural practice settings, systematically documenting interactions between everyday governance and creative production through participatory observation lasting over six months. In addition, multiple in-depth interviews were conducted with 42 key informants, covering policy implementers, rural entrepreneurs, inheritors of intangible cultural heritage, and returning youth, yielding rich firsthand qualitative data.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 delves into the conceptual foundation of “cultural decoding,” examining three layers of rural cultural resources and their transformation into creative capital.

Section 3 explores the mechanisms of “creative transformation” through design empowerment, industrial integration, technology, and academic innovation.

Section 4 analyzes the multi-stakeholder symbiosis model that drives rural cultural creativity.

Section 5 outlines future prospects, proposing a shift toward ecosystem-based development, global dialog, and long-term sustainability.

Section 6 fundamentally reimagines how culture interacts with community, economy, and technology. Finally,

Section 7 concludes with key findings and discusses the pathways for innovation within the tension between locality and modernity.

2. Cultural Decoding: The “Root” and “Soul” of Rural Cultural and Creative Industries

Within the grand narrative of rural revitalization, culture serves not only as a historical legacy but also as a core engine driving innovation. This section aims to systematically examine three layers of rural cultural resources—material cultural heritage, intangible cultural heritage, and emerging local culture—and explore how they can be transformed from static heritage into dynamic cultural and creative capital through creative decoding. This process of decoding acts as a critical bridge connecting traditional memory with contemporary value, activating rural endogenous motivation, and laying the foundation for understanding the “cultural gene decoding—creative transformation” framework proposed in this study.

2.1. Material Cultural Heritage: Tangible Carriers of Local Memory

Rural material cultural heritage—encompassing ancient village architecture, traditional farming facilities, and handicraft artifacts—serves as the most intuitive cultural symbol, bearing profound historical memories and regional characteristics that link the past with the present. These are not merely “living fossils” whispering stories of bygone eras but also precious resources for modern cultural and creative industries, fueling the inheritance and innovation of rural culture.

Take Xinye Ancient Village in Jiande, a national key protected site, as an example. It preserves over 200 well-maintained Ming and Qing dynasty buildings, where every brick seems to breathe history. Its innovative “Ancient Village + Research-Based Learning” model transforms static relics into vivid experiences: visitors can admire the delicate architecture up close and participate in hands-on activities such as ancient building surveys and agricultural cultural practices. This immersive approach has significantly enriched tourism experiences, attracting over 600,000 visitors in five years and boosting the local economy. From my perspective, the protection and utilization of heritage must also embrace modern technology—digital recording and display can break temporal and spatial barriers, allowing more people to appreciate the unique charm of rural heritage.

2.2. Intangible Cultural Heritage: Living Inheritance of Life Wisdom

Intangible cultural heritage represents the most dynamic core of rural culture, encompassing traditional skills, folk festivals, oral literature, and more. It embodies not only cultural diversity but also carries the most authentic local memories—serving as a vital source of authenticity for contemporary cultural and creative industries.

For instance, Jiande’s Nine-Surname Fishermen’s Water Wedding Custom, recognized as a national intangible cultural heritage, has been revitalized through live reenactments, experiential activities, and creatively designed products such as wedding-themed tea sets and apparel. This tradition is no longer confined to historical records; visitors can immerse themselves in its unique charm while purchasing items that reinterpret tradition through a modern lens. In my view, this approach does more than generate economic returns—it fosters a cultural ecosystem where intangible heritage naturally integrates into tourism, leisure, and community life, sustaining itself through active participation rather than static preservation.

That said, preserving intangible heritage should avoid turning it into a museum exhibit. The emphasis must be on living transmission—encouraging inheritors to pass down skills through mentorship and hands-on workshops. At the same time, we cannot ignore the role of technology [

11]. Digital tools like VR and immersive recording can expand its reach and engagement, especially among younger audiences. Yet, technology alone is not enough. What truly matters is how heritage connects to contemporary life. Developing cultural products that resonate with modern esthetics and daily use helps intangible heritage remain relevant rather than relic-like. From what we have observed, the most successful cases are those where tradition is not just displayed but lived—where cultural practice meets creative interpretation, allowing heritage to evolve while keeping its soul intact.

2.3. New Local Culture: Cultural Renewal in the Process of Modernization

Driven by modernization, contemporary rural areas have fostered a cluster of new cultural phenomena with notable cultural and creative value. These phenomena reflect rural culture’s adaptation to the times and point to its future innovative trajectory.

Among them is the “new farmer culture” spearheaded by returning youth, who bring back modern know-how—from organic farming concepts to digital marketing skills—and inject fresh vitality into rural development. By setting up cooperatives and e-commerce platforms, these new farmers not only boost the branding and marketization of agricultural products but also propel the diversified growth of the rural economy.

Two other prominent phenomena are “host-guest shared culture” from rural tourism and “smart rural culture” empowered by digital technology. The former thrives on frequent villager-tourist interactions, with co-hosted festivals and cultural exchanges becoming a new normal in rural life; it enriches tourists’ experiences while strengthening villagers’ cultural confidence and belonging. The latter, through short videos and VR-restored ancient village scenes, presents rural culture vividly, drawing young audiences and opening new dissemination channels. From my perspective, Jiande’s Strawberry Town offers a stellar example: its “Strawberry + Technology + Cultural Creativity” model integrates traditional agriculture with modern industries, turning villagers from “displayed objects” into “cultural narrators.” This identity shift, alongside economic gains, lays a solid foundation for rural culture’s sustainable innovation.

2.4. Conclusions

The three dimensions of rural culture—material heritage, intangible heritage, and emerging local culture—collectively form a rich, multi-layered “cultural gene pool” for rural creativity. Decoding these genes is not about mechanically extracting symbols but about deeply understanding their historical context, living wisdom, and contemporary relevance. Through creative translation and value reshaping, these cultural resources can be transformed into narratives, experiences, and products that resonate with modern society. This decoding process, as demonstrated by the cases from Jiande, is fundamental to enabling rural culture to evolve from a static legacy into a living, innovative force—truly becoming the “root” and “soul” of rural cultural and creative industries.

3. Creative Transformation: How to Make Culture “Come Alive” and “Become Popular”?

Following the systematic decoding of rural cultural resources, the core practical challenge lies in effectively transforming these cultural “genes” into creative forms that are perceptible, disseminable, and consumable in the contemporary market. This section aims to construct a multi-dimensional action framework for “creative transformation.” Based on three years of longitudinal research (2021–2024) in areas such as Jiande, Zhejiang, utilizing methods including participatory observation, in-depth interviews, and focus groups, we systematically examine the pathways of design empowerment, industrial integration, technological enablement, and academic innovation. These pathways collectively drive the leap of rural culture from static heritage to dynamic creative capital.

3.1. Design Empowerment: The Leap from “Local Product” to “Cultural Trendsetter”

The genuine breakthrough in rural cultural innovation often begins with design thinking—not merely as esthetic enhancement but as an act of cultural reinterpretation. When design intervenes, it can challenge the outdated notion that “rural” equates to “crude,” helping traditional symbols resonate with contemporary life.

Take Jiande’s “Qiumei Daoducai” as an example. This project transcended the typical preserved vegetable initiative by delving deeper into regional food culture, seasonal agricultural rhythms, and ancient fermentation techniques. Through thoughtful redesign, what was once an ordinary—even rustic—product was transformed into a storytelling artifact. Its “Culture Gift Box,” featuring clean, eco-conscious packaging and a booklet detailing small-batch fermentation, turned a side dish into a cultural keepsake—something to be experienced, read, and gifted. Recognized as a top intangible heritage tourism product in Zhejiang, its 160 g package sells for 99 yuan, earning nicknames like “the Hermès of pickles.” The lesson here extends beyond branding; it illustrates how design, when rooted in cultural essence, builds emotional bridges. A successful rural creative product should evoke memory and spark connection. Buyers are not merely purchasing an item—they are entering a narrative. This is why every touchpoint—material, visuals, function, even the unboxing experience—must weave storytelling into the encounter. Only then does a local specialty evolve into something meaningful: not just consumed, but deeply felt.

3.2. Industrial Integration: Building a Diverse “Culture+” Ecosystem

For rural cultural creativity to genuinely take root and flourish, focusing on isolated products is insufficient. A more dynamic path involves weaving culture into the fabric of local industries—agriculture, tourism, education, technology—through what can be termed a “culture-plus” strategy. This creates an interconnected ecosystem where each element strengthens the others. Consider “Culture + Agriculture.” It is no longer solely about growing crops; it is about growing stories. In Wuyuan, Jiangxi, seas of rapeseed flowers are cultivated not just for harvest but also for photography, transforming fields into seasonal destinations. Elsewhere, “adoptive agriculture” allows urban residents to remotely nurture a tree or a patch of rice, receiving curated harvest boxes that convey not only produce but also a sense of participation and place.

“Culture + Tourism” is evolving beyond souvenir stalls. In Weifang, Shandong, kite culture is not confined to museum displays. Visitors participate in workshops—framing, painting, flying—turning a visit into a hands-on immersion in intangible heritage. In Lijiang’s Naxi homestays, learning Dongba script or dressing in traditional attire transforms overnight stays into deep cultural experiences, naturally extending visitor duration and expenditure. Then there is “Culture + Technology.” Digital tools are breathing new life into ancient narratives. At the Liangzhu ruins in Zhejiang, VR/AR reconstructions allow visitors to walk through 5000-year-old streets and rituals. Sichuan’s Sanxingdui Museum has sparked engagement through digital stickers and collectibles, attracting younger audiences to archeological storytelling while opening new revenue streams. What unites these examples is connectivity. Culture acts as a living core—a source of meaning and differentiation—while partner industries provide context, scale, and relevance. Together, they build something greater: a resilient, multi-layered rural economy where culture is not merely preserved but actively evolves.

3.3. Technology Empowerment: Connecting Ancient Culture with Modern Needs

Digital technology provides an unprecedentedly powerful tool for the “breakthrough” development of rural cultural creativity. It not only transforms how traditional culture is preserved and disseminated but also injects new vitality into innovative creation, becoming a key force in promoting the modernization and enhancement of market value for rural cultural resources [

12].

On one hand, digital preservation enables the systematic and accurate retention of rural cultural heritage, allowing it to “live longer” and “live better.” Through technologies such as high-precision 3D scanning, drone mapping, 360-degree panoramic imaging, and high-definition video recording, detailed digital archives can be created for many endangered traditional structures, artisanal processes, and folk rituals. These digital resources are invaluable for protection and research while also providing authentic, rigorous source material for subsequent cultural and creative product development, establishing a foundation for the credibility and uniqueness of rural creativity from the outset.

On the other hand, new media dissemination has significantly expanded the reach of rural culture, enabling it to “spread more widely” and “reach more targeted audiences” [

13]. Content platforms such as Douyin, Xiaohongshu, and Bilibili have become new windows for showcasing rural culture. Themes like “rural intangible heritage artisans,” “handicraft restoration diaries,” and “returning youth entrepreneurship” have garnered tens of billions of views through authentic, vivid, and heartfelt narratives. A successful example is “Yuanjia Village” in Xi’an, Shaanxi. Its specialty snacks and folk experiences gained widespread exposure through short videos, transforming it from a local brand into a nationally recognized internet-famous destination. This form of dissemination not only directly boosts tourism consumption but also helps shape an appealing rural cultural brand image, laying the groundwork for the sales of cultural and creative products.

At the innovation level, the application of cutting-edge technologies like artificial intelligence is profoundly reshaping the production and creation models of traditional cultural creativity. For instance, silverware craftsmen in Heqing, Yunnan, collaborating with tech teams, have introduced AI design tools to intelligently identify, deconstruct, and recombine traditional patterns, generating new designs that retain ethnic styles while conforming to modern esthetics. This significantly shortens the product development cycle—a process that previously took half a month can now be compressed to just three days, tripling production efficiency. This not only lowers the barrier to innovation but also enables traditional crafts to respond more swiftly to changes in market demand.

3.4. Academic Innovation: Building a “Research-Practice-Policy” Closed Loop

Agricultural & Rural Studies (hereinafter “A&R”) employs a “research-practice-policy” closed-loop approach, positioning academia as an engine for sustaining the vitality and popularity of rural cultural and creative industries. In collaboration with domestic and international institutions such as the University of Novi Sad in Serbia and Zhejiang A&F University, the journal has established a “Cultural Rural IP System.” This system leverages academic perspectives to excavate rural cultural resources and facilitate the global dissemination of rural brands.

The journal invites influential scholars to conduct in-depth grassroots research and produce cover stories based on firsthand materials, tightly integrating academic inquiry with rural praxis. The cover feature of Volume 2, Issue 4 focused on Jiande’s Tuanjie Village, systematically tracing the village’s developmental trajectory—from historical-cultural context and ethnic characteristics to models of agricultural-tourism integration [

14,

15]. It highlighted Jiande’s strawberry industry and the high-skilled talent brand of “Strawberry Masters,” shaping the distinctive rural IP of “Jiande Masters” and pioneering the international academic dissemination of Jiande’s rural brand.

Furthermore, the journal innovatively launched an “A&R” video public account, publishing rural diaries accompanied by short videos that document the authentic practices and reflections of diverse rural stakeholders—scholars, designers, entrepreneurs, and others—forging a new paradigm of “visualized academia.” Through multimodal content like short videos and visual narratives, the journal transforms academic findings into publicly accessible, participatory, and shareable rural knowledge products, dismantling barriers between academia and the public.

The journal also regularly organizes “International Workshops on Rural IP,” convening policymakers, village Party secretaries, returnee youth, researchers, investors, and other stakeholders to discuss rural development issues. This promotes the translation of research outcomes into policy recommendations, forming a closed-loop mechanism of “academic research—practical implementation—policy feedback.”

3.5. Summary

Centered around the core question of “how to bring culture to life and make it popular,” this chapter constructs a multi-dimensional action framework for “creative transformation.” Based on three years of longitudinal research in areas such as Jiande, we argue that the transition of rural culture from static heritage to dynamic creative capital is not the result of a single force, but rather a process of synergistic empowerment and co-evolution through multiple pathways such as design, industry, technology, and academia.

Design empowerment fundamentally reconfigures how rural cultural value is perceived and expressed. Its essence lies in a process of deep cultural decoding paired with contemporary articulation—transforming localized symbols into narrative vehicles that resonate emotionally. This journey shifts a product from being merely a “local specialty” to becoming a “cultural beacon,” redefining its place in the modern imagination. Industrial integration, meanwhile, builds out varied arenas where cultural value can be realized and amplified. Through what we might call a “culture-plus” logic, cultural genes are woven into the very structure of sectors like agriculture, tourism, and technology. This weaving fosters a resilient, interdependent ecosystem—a kind of living soil—where culture finds sustained nourishment and continues to evolve through practical engagement. When it comes to technology empowerment, we see the emergence of a new language and toolkit that bridges ancient wisdom and contemporary desires. Digital approaches do more than safeguard and spread cultural heritage; they unlock fresh potential for creative reinvention. By harnessing tools from AI to immersive media, traditional culture enters into a dynamic dialog with present-day life—speaking directly, and often powerfully, to younger generations in particular. In this ecology, academic innovation acts as both catalyst and connective tissue. It weaves local practice into communicable knowledge, channels scholarly insight into actionable momentum, and helps shape institutional conditions that nurture further innovation. By closing the loop between research, practice, and policy, academia provides not just ideas but a sustained support system—ensuring that rural culture remains vital, adaptive, and continually revitalized.

4. Multi-Stakeholder Symbiosis: Who Drives the “Wheel” of Rural Cultural and Creativity?

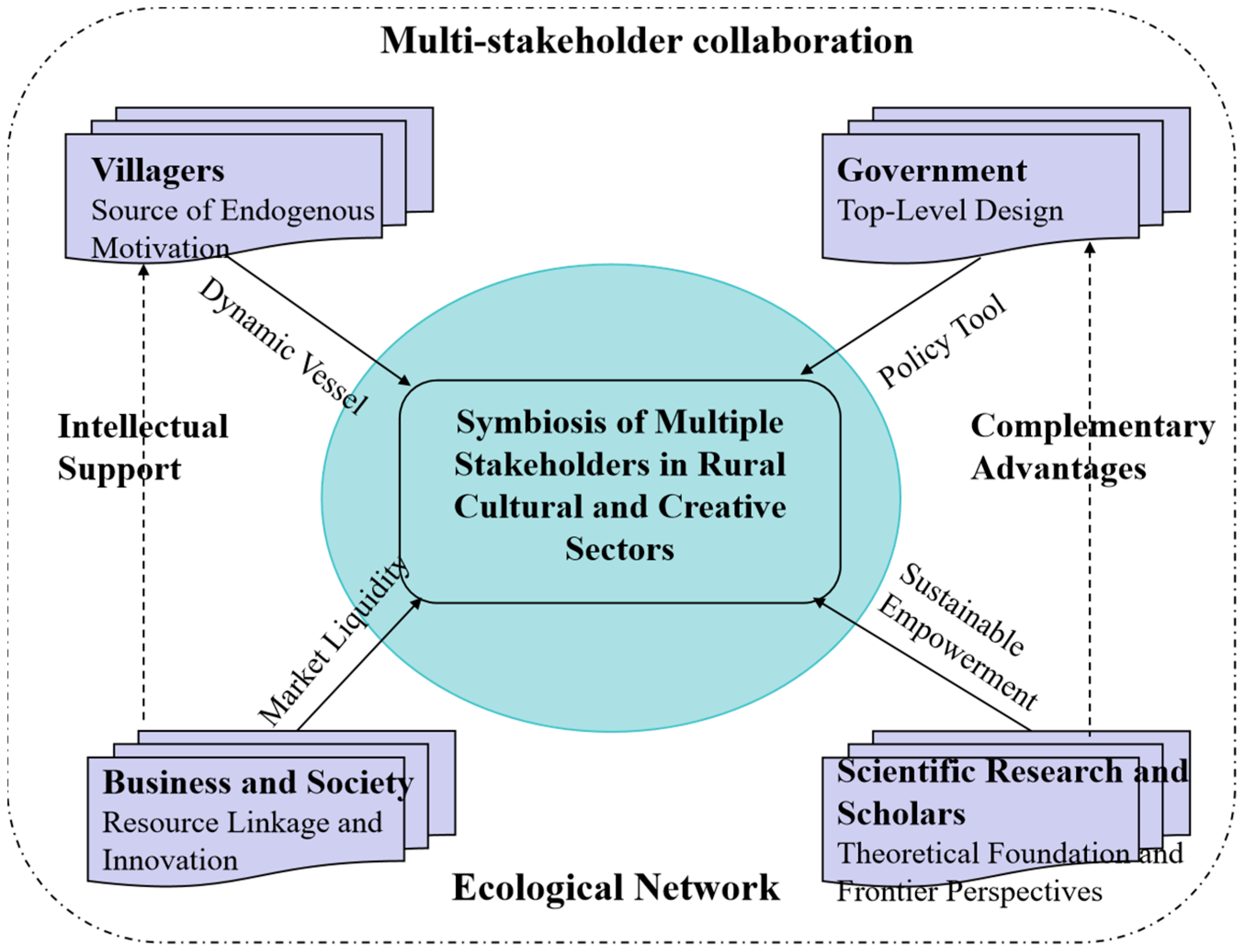

This section systematically deconstructs the roles and interactive mechanisms of the four key actors—government, villagers, enterprises, and social organizations, and research institutions—within the rural cultural and creative ecosystem. It reveals that rural cultural innovation is not the product of any single force, but an organic symbiotic process shaped through the collision, negotiation, and collaboration of multiple stakeholders. These actors function like different spokes driving a giant wheel forward, collectively forming the core dynamic system for the sustainable development of rural cultural creativity (as shown in

Figure 2).

In this system, the government provides the institutional foundation and directional guidance, acting as both a “guide” and a “foundation builder” that shapes the ecosystem through top-level design, policy support, and infrastructure investment. Villagers, as the living carriers of culture and the source of endogenous motivation, ensure the authenticity and local character of cultural projects, allowing innovation to be rooted in tradition and culture to be revitalized through inheritance. Enterprises and social organizations inject resources, efficiency, and innovative reach, serving as “resource linkers” and “innovation catalysts” that introduce market thinking, creative design, and modern technology to help transform cultural outcomes from artworks into products and industries. Meanwhile, academia contributes theoretical depth and forward-looking vision, acting as “theoretical support” and “frontier scouts” that provide intellectual grounding and future-oriented insight, ensuring innovation possesses both cultural depth and contemporary vitality.

4.1. Government: Top-Level Designer and Ecosystem Builder

The government plays a dual role as “guide” and “foundation builder” in the development of rural cultural and creativity. Its role is manifested not only in macro-level policy guidance and resource coordination but also in providing systematic support for nurturing the cultural and creative ecosystem through institutional innovation and public service provision. Firstly, policy supply and strategic guidance have become key drivers for the initial stages of rural cultural and creativity. In recent years, from the central government to local levels, a series of policies related to cultural revival and rural revitalization have been introduced, significantly enhancing the policy visibility and resource accessibility for rural cultural and creativity. These workshops not only continue skill inheritance but also gradually develop composite formats integrating experience, sales, and research-based learning, becoming rural cultural landmarks and nodes of economic growth. Secondly, the government plays an irreplaceable role in infrastructure and platform construction.

From a broader perspective, the government, through institutional innovation, has effectively stimulated the intrinsic vitality of both the market and society. Many localities have introduced targeted support policies, such as tax incentives, loan interest subsidies, and land-use guarantees. These measures have significantly reduced the various risks and actual costs for social capital and cultural-creative enterprises entering rural areas. At the same time, the government has gradually expanded its focus to “soft” investments like standard-setting and talent development. For instance, the implementation of the “One Village, One Product” certification system aims to strengthen regional cultural identity and branding, while initiatives such as advanced training classes for intangible cultural heritage inheritors and courses for rural cultural-creative brokers are designed to enhance practitioners’ professional skills and market operation capabilities. Together, these approaches help steer previously fragmented and spontaneous rural cultural-creative practices toward a more systematic and sustainable development path.

However, the government must also guard against suppressing endogenous growth momentum through “excessive intervention.” The more successful rural cultural-creative projects often follow the model of “the government sets the stage, and the people put on the show.” This means that while setting boundaries and providing support, the government should also fully respect the autonomy of villagers and cultural entities, avoiding the simplistic replacement of market principles and the inherent logic of cultural development with administrative will.

4.2. Villagers: The Endogenous Driving Force of Cultural Inheritance

If rural culture is to remain alive and relevant, villagers must be more than its keepers—they must be its narrators, innovators, and driving force. Turning passive cultural “carriers” into active creators is what gives authenticity and energy to rural creative industries. In Jiande, Zhejiang, this shift is embodied in the “Jiande Masters” initiative. Locals skilled in strawberry farming or bun-making are now recognized as “Masters,” equipped not only with traditional know-how but also with branding, e-commerce, and experiential service skills. Take the “Jiande Aunties.” They no longer just sell steamed buns; they host making classes, organize food festivals, and craft related souvenirs—transforming simple trade into cultural storytelling and sensory experience. It is this deeply rooted participation that lends rural creativity its irreplaceable texture. In Xinhua Village, Yunnan, generational silversmithing has grown into a community-led tourism and craft economy, involving over 70% of households. Here, creativity is not imposed—it is an organic extension of daily life, a bridge between heritage and today’s values.

Yet sustaining this agency is not without challenges: balancing tradition with contemporary taste, bridging generations, and connecting local artisans with wider markets. Beyond policy or market interventions, what’s needed are lasting structures for capacity-building—continuous training, exchange opportunities, and fair benefit-sharing systems. Only then can villagers feel truly engaged, accomplished, and empowered in the creative process they help shape.

4.3. Enterprises and Social Organizations: Resource Linkers and Innovation Catalysts

Enterprises and social organizations have become indispensable in scaling up and bringing rural cultural creativity to the market. They fill gaps where public services may fall short and individual villagers face limitations—by injecting resources, introducing technology, and opening up new channels. Their role often shifts creativity from being an “artwork” to becoming a viable “product,” and eventually, a sustainable “industry.” Companies like Zhejiang Qiumei Food are good examples of this push. Building on the traditional Daoducai fermentation technique, founder Pan Qiumei introduced modern production and quality controls. This moved the craft from small-batch making to standardized output, without losing its authentic flavor. Through thoughtful packaging and multi-channel distribution—from supermarkets to e-commerce—what was once a local condiment became a recognized provincial brand, lifting farmers’ incomes and enriching the regional identity.

Beyond traditional producers, design studios, tech firms, and cultural agencies are entering the scene. They bring tools like VR to restore historic village layouts, livestreaming to showcase crafts, and IP development to turn local tales into creative assets—dramatically widening how rural culture can be expressed and shared.

Meanwhile, social organizations—cooperatives, industry associations, and NGOs—often act as connectors and facilitators. They organize workshops where designers collaborate directly with artisans, help farmers pool orders to negotiate better terms, and build bridges between villages and markets. Because these groups work close to the ground, they tend to foster more grounded collaboration models, like “company + cooperative + farmer” or “designer + craftsperson,” which stand a better chance of mutual benefit. That said, when external organizations engage with rural communities, one principle is vital: respect local context and strengthen local agency. Short-term commercial gain or forced “modernization” can easily distort cultural meaning. The most enduring partnerships are those rooted in genuine understanding—where innovation honors tradition, and growth is shared, creating value that is at once economic, cultural, and social.

4.4. Research and Academia: Theoretical Support and Frontier Scouts

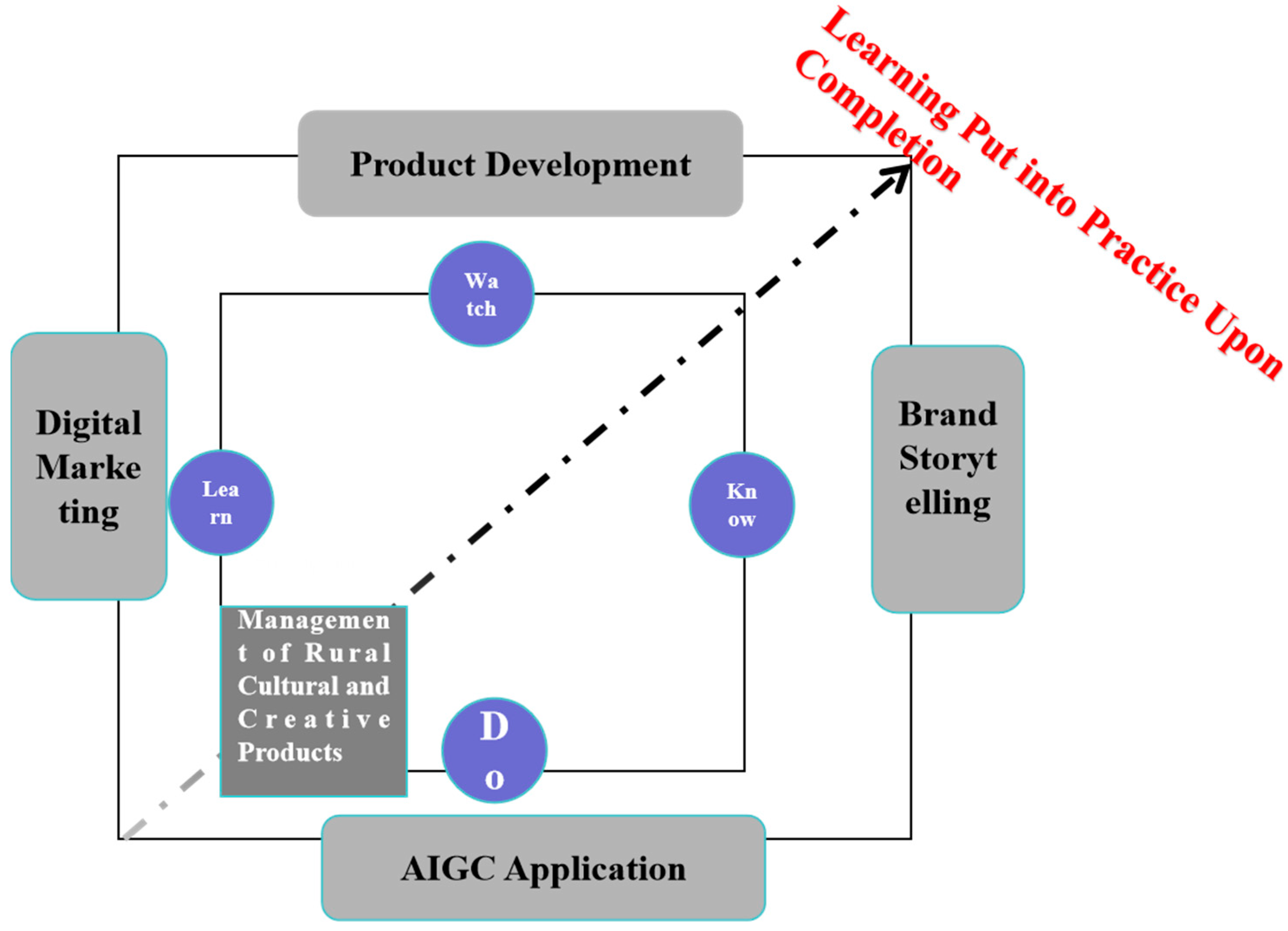

Research institutions and scholars are becoming the “strongest brains” driving the development of rural cultural and creativity, continuously empowering the industry through the “troika” of theoretical innovation, technological research and development, and talent cultivation. In terms of theoretical sourcing, Professor Wu Yanxiong of Zhejiang A&F University founded the academic journal Agricultural & Rural Studies, which has successively published landmark research results such as “Cultural Gene Decoding” and the “Industrial Integration Double Helix,” transforming scattered rural narratives from the fields into replicable, disseminable academic syntax, providing theoretical support for rural cultural and creativity. In terms of talent cultivation, the National Social Science Fund Art Project “Training for Management Talents in Rural Cultural and Creative Products (2025-A-05-118-649)” focuses on 30 industry pioneers nationwide, constructing a four-stage training system of “Learning-Observing-Reflecting-Practicing” to systematically enhance trainees’ four core competencies: product development, brand storytelling, AIGC application, and digital marketing, achieving an efficient conversion closed loop of “implementation upon completion” (as shown in

Figure 3). In terms of scenario embedding, relying on industry-university-research platforms such as the Rural Operation Research Institute of Zhejiang A&F University and the A&R Scholars’ Home, scholar teams regularly go to the grassroots, deeply participating in county-level development planning, leading the organization of rural cultural and creativity competitions, and establishing “Field Roundtable” dialog mechanisms, truly “writing their papers on the land” and running academic models in real business scenarios, promoting the synchronization and resonance of the academic pace with rural revitalization.

4.5. Summary

However, the sustained and healthy functioning of this symbiotic system still faces multiple tensions and challenges: how to strike a balance between government guidance and community autonomy? How to safeguard villagers’ agency rights and equitable benefits in the process of cultural capitalization? How can external market forces operate while respecting local cultural logic? And how to establish a more efficient knowledge conversion cycle of “research-education-production-policy”? The future deepening of rural cultural and creative development depends not only on the enhancement of the capabilities of each stakeholder but also on the ability to build a more inclusive, equitable, and resilient collaborative governance framework and value-sharing mechanism. This requires continuous reflection and adaptation in practice, ultimately achieving the harmonious integration of cultural heritage, industrial development, and community well-being.

5. Future Prospects: A New Vision for Rural Cultural and Creativity Driven by the Cultural Engine

This section aims to propose an integrated and forward-looking framework for rural cultural and creative development, situating it within a broader academic discourse. The study posits that the future of rural cultural creativity should undergo three key shifts: from scattered product innovation to systematic ecological construction, from closed displays of local characteristics to open participation in global dialog, and from a pursuit of short-term traffic to long-term sustainable development. These perspectives resonate with and extend recent scholarly discussions on “cultural ecosystems” [

16], the “globalization of place branding”, and “cultural sustainability” [

17]. The following discussion will elaborate on the connotations, pathways, and challenges of these three shifts, integrating specific cases and existing research.

5.1. From a “Product-Oriented” to an “Ecosystem-Based” Approach: The Imperative for Systemic Development

Currently, rural cultural and creative practices in many regions remain entrenched in a “product-oriented” model, characterized by specialty crafts and festival activities. While capable of generating short-term attention, this model is vulnerable to market fluctuations, struggles to yield sustained benefits, and often falls into homogenized competition. This mirrors issues identified in earlier discussions on the risks of “cultural commodification” [

18]. The future breakthrough lies in shifting from isolated innovation to constructing an integrated “rural cultural and creative ecosystem” that harmonizes production, daily life, and ecology.

At the core of this system is the cultivation and operation of “cultural IP” as a central thread, breaking away from singular product forms to create an industrial chain with diversified, integrated formats. A successful rural cultural IP can connect various forms such as creative merchandise, immersive experiences, themed tourism, and digital content. For instance, using traditional solar term culture as an IP core, one can not only develop corresponding foods and handicrafts but also systematically create “Solar Term Life Festivals,” themed homestay experience packages, and online audio-video courses [

19,

20]. This diversifies cultural expression and stabilizes revenue structures. Digital technology will further expand the ecosystem’s boundaries—constructing “digital twin villages” through VR/AR technology allows users to roam online and participate in virtual farming activities, thereby breaking physical constraints and enabling all-weather, cross-regional cultural experiences. This aligns with the frontier research trend of “digital empowerment for cultural heritage” [

21,

22].

The healthy functioning of the ecosystem depends on “human” connections. Future rural cultural and creative industries will increasingly emphasize “community-based operation,” leveraging online and offline platforms to integrate multiple stakeholders—villagers, creators, tourists, enterprises, investors—into a “cultural community” dedicated to co-creation, co-management, and shared benefits. In this model, villagers transition from passive cultural providers to active storytellers, experience designers, and even partners; tourists may also shift from mere consumers to content co-creators (e.g., sharing travelogs, participating in public art). Such deep engagement not only enhances user stickiness and loyalty but also fosters brand identity and social support networks. Policy and institutional safeguards form the cornerstone for the ecosystem’s robust development. Future efforts should further refine intellectual property protection for intangible heritage skills and local symbols, encouraging patent applications, geographical indication certifications, and copyright registrations. Simultaneously, more scientific certification standards for rural cultural and creative enterprises and products should be established, with strengthened market oversight to curb counterfeit products and excessive commercialization that undermine cultural authenticity. In talent cultivation, more training bases for rural cultural and creative talents are needed, offering comprehensive courses covering traditional crafts, design innovation, e-commerce operations, and brand management to systematically nurture “local experts” and “new cultural-creative farmers.” This systemic view on talent resonates with the critical role of “community capacity building” in sustainable development [

23].

5.2. From “Local Characteristics” to “Global Dialog”: The Worldwide Expression of Rural Cultural Value

The countryside is a carrier of regional culture but also contains universal values capable of resonating globally. Future rural cultural creativity should not be confined to the positioning of “local specialties” or “domestic tourist hotspots.” Instead, it should adopt a global perspective, elevating Chinese rural culture from a “local symbol” to a “world language” and actively engaging in global cultural exchange and dialog. This shift is deeply connected to international academic topics such as “glocalization” [

24] and the construction of “cultural soft power” [

25].

Pioneering cases offer inspiration. For example, Qianhe Village in Jiande City, a significant birthplace of the idea that “women hold up half the sky,” has attracted domestic attention for its historical practices and cultural spirit. Through in-depth cover feature reporting in the international academic journal Agricultural & Rural Studies, its story has been elevated to a globally significant “Model of Chinese Rural Development” [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. This indicates that the internationalization of rural cultural creativity is not simply about exporting products but involves skillfully excavating and refining the universal themes inherent in local culture—such as the wisdom of harmonious coexistence between humans and nature, traditions of community co-governance, and the philosophy of manual labor—and expressing them through internationalized, contemporary modes, making them an important medium for the world to understand Chinese civilization (As shown in

Figure 4).

Achieving effective global dialog requires diverse channels and strategies. On one hand, collaborations with international brands, designers, and art festivals can launch co-branded products and participation in international events like the Venice Biennale or Milan Design Week to enhance visibility. On the other hand, actively utilizing digital platforms for cross-cultural communication—such as creating multilingual rural culture accounts on international social media platforms like YouTube and Instagram to tell rural stories and showcase artisan skills—is crucial. More importantly, while encouraging rural culture to “go global,” it is essential to design deep experiential products that attract international audiences to “come in,” such as international intangible heritage research camps and rural artist residency programs, transforming Sino-foreign exchange from one-way communication into two-way interaction [

33,

34]. This combination of “bringing in” and “going out” aligns with the emphasis on “reciprocal understanding” in cultural exchange theory.

The ultimate goal is to transform the cultural practices of China’s countryside into civilizational IPs with global influence. They are both Chinese and global, both traditional and modern, capable of responding to globally shared sustainable development issues and providing “Chinese solutions” to worldwide challenges such as rural governance, ecological protection, and cultural inheritance, thereby establishing the cultural subjectivity and discourse power of the Chinese countryside on the global stage.

5.3. From “Short-Term Hype” to “Long-Term Development”: Safeguarding the Foundations of Cultural Sustainability

The ultimate goal of rural cultural and creative development is not to chase fleeting traffic and immediate profits but to activate rural endogenous motivation through cultural power, achieving long-term revitalization where economy, society, culture, and ecology advance in coordination. This requires shifting the development model from “momentary popularity” to “enduring vitality,” adhering to the basic principles of sustainability. This section is closely related to research fields such as “sustainable heritage management” and “community resilience” [

35,

36,

37].

The primary principle is “protection first, rational utilization.” In the development process, it is essential to resolutely prevent excessive commercialization from eroding cultural authenticity and rural landscapes [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42]. In reality, some ancient villages have been transformed into uniform “imitation ancient commercial streets” to cater to tourists, and traditional rituals have been simplified into superficial performances, which not only lose cultural depth but also destroy the unique appeal of rural tourism. Ecological protection is equally important—ancient trees must not be felled, waterways filled, or basic farmland damaged for the construction of cultural and creative facilities or the opening of tourist areas [

43]. A negative list system for the development of rural cultural resources should be established, defining protection red lines and advocating for an ecological cultural and creative model characterized by low intervention, light investment, and integration with nature. This aligns with UNESCO’s advocacy for “nature-based solutions for cultural heritage.”

The key to cultural inheritance lies with “people.” Therefore, “intergenerational transmission” is the core of sustainable development. Efforts must be made to solve the dilemma of “skills being lost when people pass away.” This can be addressed by implementing “Intangible Heritage in Schools” programs, embedding local culture courses in primary and secondary basic education; improving the “Vitalization Plan for Traditional Crafts,” encouraging veteran artisans to take on young apprentices and providing subsidies for transmission and learning; and establishing rural maker centers to attract young people to return home and start businesses, injecting new perspectives and vitality into traditional culture. Only when more young people recognize the value of rural culture and can derive decent income and professional pride from it can the cultural bloodline truly flow perpetually. This focus resonates with the continued emphasis on “inheritors” and “living heritage” in heritage studies.

Finally, mechanisms that guarantee “community participation” and benefit-sharing must be established, making villagers the main agents and primary beneficiaries of cultural development. Specific measures may include: allocating a certain percentage of revenue from cultural and creative projects to a “Rural Cultural Development Fund” for public facility construction and traditional skill protection; prioritizing the hiring of local villagers for operational and service positions; and encouraging villagers to contribute land, houses, or skills as shares to obtain long-term equity income. When villagers tangibly enjoy development dividends, their cultural awareness and participation initiative will significantly increase, forming a virtuous cycle of “protection—development—benefit—re-protection.” This community-based benefit mechanism is recognized as key to sustainable models in the international rural development field (e.g., Bebbington, 1999) [

44].

5.4. Summary

Based on proposing the three future developmental shifts for rural cultural creativity, this section attempts to situate them within a broader academic discourse for dialog and positioning. The study finds that constructing a creative ecosystem, participating in global dialogue, and consolidating the foundations of sustainable development are not only summaries of experience based on Chinese local practice but also highly relevant to international scholarly discussions on cultural economy, globalization-local interaction, and heritage sustainability. However, this study also recognizes that these shifts will inevitably face numerous challenges in practical implementation, such as: How to balance the interests of multiple stakeholders in ecosystem construction? How to maintain the autonomy of cultural expression in global dialogue rather than being dominated by an “other” perspective? How to establish truly fair and effective community governance and benefit distribution mechanisms for sustainable development? These questions warrant further in-depth analysis in subsequent research incorporating more diverse cases. The framework proposed in this paper aims to provide an integrated analytical perspective for understanding the complex evolution of rural cultural creativity in China and to offer reference for future theoretical exploration and policy practice.

6. The Path Ahead: Where Culture Fuels Rural Creativity

Looking forward, the evolution of rural cultural creativity demands more than incremental improvements—it calls for a fundamental reimagining of how culture interacts with community, economy, and technology. The following sections outline three interconnected shifts that could redefine its trajectory.

6.1. From Making Products to Growing Ecosystems

In many places, rural creativity remains anchored in a “product-first” approach: a craft item here, a seasonal festival there. While such initiatives can spark interest, they often struggle to withstand market shifts or create lasting impact. A more resilient path lies in cultivating what might be termed a cultural ecosystem—an interconnected web where production, daily life, and ecological awareness nourish one another.

Central to this ecosystem is the idea of cultural IP—not as a logo to stamp on goods, but as a living narrative that threads through diverse forms of engagement. Imagine a rural region grounding its identity in solar term culture. This could translate not only into specialty foods and crafts, but also into curated “Solar Term Life Festivals,” themed homestay experiences, and even online courses that reconnect urban audiences with seasonal rhythms. Digital tools like VR and AR could extend this further, allowing “digital twin villages” to offer immersive farming experiences or virtual heritage walks—breaking geographical barriers and enabling cultural participation across distances.

Of course, an ecosystem cannot thrive without people at its heart. The future points toward community-driven operation, where villagers shift from being passive cultural “sources” to active storytellers and experience designers. Tourists, too, may become co-creators—contributing travel narratives or collaborating on public art. This deeper engagement builds not only loyalty but also a shared sense of ownership. Supportive policies will remain crucial: clearer IP protection for local symbols and crafts, sensible certification systems to guard against cultural dilution, and sustained investment in training a new generation of “cultural-creative farmers” who blend traditional knowledge with contemporary skills.

6.2. From Local Identity to Global Conversation

Rural cultures carry within them truths that transcend locality. The challenge—and opportunity—ahead is to help these cultures speak not only to domestic visitors but to the world. This means moving beyond framing rural creativity as “local specialty” or “domestic tourism highlight,” and instead positioning it as a meaningful participant in global cultural dialog.

Consider Qianhe Village in Jiande. Known historically as a cradle of the “women hold up half the sky” ethos, its story has attracted international academic attention, featuring as a cover study in Agricultural & Rural Studies. Such recognition underscores an important lesson: going global is not just about exporting products—it is about identifying the universal themes nested within local contexts (be it gender equality, community governance, or ecological wisdom) and expressing them through forms that resonate across cultures.

Practical pathways for this include strategic collaborations—joint branding with international designers, participation in global forums like the Venice Biennale—as well as digital outreach through multilingual social media channels that showcase rural artisans and stories. Equally vital is creating invitations for deeper engagement: artist residencies, international heritage research camps, and immersive exchange programs that transform one-way cultural export into two-way dialog. The aim, in the long run, is to nurture rural cultural practices into what could be called civilizational IPs: unique yet universally relevant contributions that offer Chinese perspectives on shared global concerns—from sustainable living to cultural continuity—and in doing so, strengthen the voice of the Chinese countryside on the world stage.

6.3. Beyond Short-Term Buzz: Ensuring Culture Endures

The true test of rural cultural creativity will be its endurance. If the goal is lasting revitalization—where economic, social, cultural, and ecological well-being reinforce one another—then the approach must shift from seeking viral moments to fostering continuous, rooted growth [

45,

46,

47].

This begins with a clear ethic: protect first, then develop wisely. In practice, that means resisting the pressure to turn ancient villages into uniform “old-town shopping streets,” or reducing sacred rituals to staged performances for tourists. Ecological sensitivity is non-negotiable; no cultural project should come at the cost of centuries-old trees, natural waterways, or fertile farmland [

48]. One practical step could be establishing “negative lists” for rural cultural development—clear boundaries that safeguard what must remain untouched—while encouraging light-touch, ecologically integrated creative interventions.

Crucially, sustainability depends on people. Intergenerational transmission remains a fragile link. Embedding local culture and intangible heritage into school curricula, supporting master-apprentice programs with tangible incentives, and creating rural maker spaces to attract young returnees are all ways to keep skills and stories alive. When youth see a future—both meaningful and viable—in rural cultural work, the lineage sustains itself.

Finally, none of this holds without fair and inclusive benefit-sharing. Villagers should be recognized as core agents and primary beneficiaries. Mechanisms might include allocating a share of creative project revenues to a community cultural fund, prioritizing local hiring, or enabling villagers to contribute land or skills in exchange for long-term stakes. When people tangibly gain from cultural development, their motivation to steward and innovate grows—creating a virtuous cycle where protection enables development, and development reinforces protection [

49].

In the end, the future of rural cultural creativity rests on seeing culture not as a resource to be extracted, but as a living force to be nurtured—one that can help villages thrive on their own terms, while conversing confidently with the world.

7. Conclusions and Discussion

7.1. Conclusions: Cultural Decoding and Multi-Stakeholder Symbiosis Drive Endogenous Rural Innovation

Through an in-depth analysis of rural cultural and creative practices in Jiande City, Zhejiang, this study finds that the high-quality development of the rural cultural and creative industry is essentially a systematic process of “cultural gene decoding—creative value transformation—multi-stakeholder symbiosis.” This process is neither a simple replication of traditional culture nor a one-way implantation of external resources. Instead, through deep local decoding and creative transformation, fragmented cultural resources are converted into cultural capital with modern communicative power, consumption appeal, and emotional resonance.

Firstly, effective cultural decoding must move beyond symbolic extraction to deeply excavate the “spiritual core” within local culture that possesses contemporary value. In Jiande’s practice, the transformation of the “Nine-Surname Fishermen’s Water Wedding Custom” from a traditional ritual into an immersive cultural tourism experience, and the extension of agricultural production in “Strawberry Town” into a pastoral life narrative, demonstrate that only by identifying the spiritual convergence point between traditional culture and modern life can cultural resources achieve sustainable activation.

Secondly, creative transformation must be built upon an ecosystem of synergistic symbiosis among multiple stakeholders. Entities such as the government, villagers, enterprises, and academia form a dynamic balance through their distinct roles of “guiding, carrying, linking, and enabling.” It is particularly noteworthy that the shift in villagers’ identity from “cultural holders” to “cultural narrators” is a key indicator of whether a project can truly take root in the local context. Furthermore, the bridging role played by academic platforms like Agricultural & Rural Studies in theoretical refinement and international dissemination opens new possibilities for rural stories to reach a global audience.

Finally, the sustainable development of rural cultural and creativity ultimately depends on its ability to construct a virtuous cycle of “culture-industry-community.” This requires both respecting the laws of cultural development to avoid the erosion of cultural authenticity by excessive commercialization, and establishing reasonable benefit-sharing mechanisms to ensure villagers become the primary participants and long-term beneficiaries of cultural development. Jiande’s exploration shows that when culture truly becomes an endogenous driver of rural areas, it brings not only economic benefits but also the reconstruction of community identity and the awakening of cultural confidence.

7.2. Discussion: Innovation Pathways Within the Tension Between Locality and Modernity

In the practice of rural cultural and creative industries, we consistently face a fundamental tension: how to maintain cultural locality while achieving modern innovation? Although there is no standard answer to this question, the practice in Jiande provides us with multi-layered and deepen-able pathways for reflection.

- (1)

Moving beyond the binary framework of “preservation versus development” toward “embedded innovation.” Based on insights gained through multiple field studies, the most vital rural cultural and creative projects often do not simply choose between “conservation” and “renovation.” Instead, grounded in a deep understanding of the local cultural fabric, they develop a form of “rooted innovation” (embedded innovation). For instance, the enduring appeal of the research-based learning program in Xinye Ancient Village does not stem from the perfect restoration of ancient architecture but from its reinterpretation of Ming and Qing dynasty life wisdom through contemporary educational experiences. This type of innovation is not a departure from tradition but a living continuation of local cultural context in modern settings—essentially a process of “cultural re-embedding,” weaving traditional elements into contemporary life and meaning systems.

- (2)

Reconstructing “locality” and shifting narrative authority in the digital wave. It is worth further exploring how digital technology redefines the “locality” of rural areas. Do practices such as “rural internet celebrities” on short-video platforms and VR restorations of traditional crafts inevitably dilute cultural locality? Our observations in Jiande suggest that when villagers actively use smartphones to document their lives and showcase their skills via livestreams, digital technology becomes a new tool for expressing cultural agency. The key issue may not lie in the technology itself but in who holds the narrative authority. The formation of a digital sense of place depends on whether technology enhances rather than replaces the expression opportunities of local actors. In this process, the integration of “digital literacy” and “cultural autonomy” becomes the core mechanism for the preservation and re-creation of locality in the digital era.

- (3)

Shifting from “product-oriented” to “relationship-building”: social capital as the soil for innovation. Rural cultural and creative endeavors are undergoing a notable shift from “creating objects” to “creating connections.” Successful cases often not only produce cultural and creative products but also construct new forms of social relationships—such as long-term adoption ties between urban families and rural households, co-creation partnerships between designers and artisans, and knowledge dialogs between scholars and villagers. These relationships themselves constitute social capital for cultural innovation, whose value may even surpass that of tangible products. In this process, rural areas transform from consumed “cultural landscapes” into co-produced “relational fields,” making the innovation process more participatory and sustainable.

- (4)

Confronting structural challenges: deficiencies in institutional design and systemic collaboration. It must be clearly recognized that the development of rural cultural and creative industries still faces deep-seated challenges. Research has found that some villages experience a sense of “being designed” when introducing external creative forces; some intangible cultural heritage projects risk simplification of skills and hollowing out of meaning during marketization; and barriers in translating discourse systems persist between academic research and grassroots practice. These issues are not merely operational but reflect shortcomings in the current institutional design regarding participation mechanisms, benefit distribution, and evaluation systems. The future requires establishing more inclusive and adaptive governance frameworks to promote the formation of a genuine “co-governance” model.

- (5)

The countryside as method: a potential shift in the perspective on development. The deeper significance of rural cultural and creative industries may lie in offering a new perspective for rethinking “development”—one that does not view the countryside as an object in need of transformation but as a source from which modern people can draw wisdom and find solace. This shift in perspective demands sufficient “cultural patience” and “local reverence” in practice, as genuine innovation often grows out of a profound understanding of tradition and emerges from the synergistic evolution of local networks, institutional environments, and cultural rhythms.

In summary, the practice of rural cultural and creative industries reveals that locality and modernity are not binary opposites but are mutually reshaped through ongoing dialog. Effective innovation is not exogenously transplanted but emerges from the creative activation of local contexts. Future research should further explore the interplay of institutional innovation, digital empowerment, and social networks in rural cultural development to foster the formation of a more resilient and inclusive rural cultural ecosystem.

7.3. Policy Recommendations

Based on an analysis of rural cultural and creative practices in areas such as Jiande, this study identifies several institutional and structural obstacles that hinder their sustainable development. To better stimulate the endogenous driving force of rural culture and effectively transform “cultural genes” into “innovative momentum,” the following policy recommendations are proposed, aiming to build a more inclusive, equitable, and resilient governance system for rural cultural and creative industries.

- (1)

Deepen the systematic decoding and localized transformation of cultural resources to avoid symbolic exploitation. Currently, cultural development in many regions remains at the stage of superficial symbol extraction, lacking respect for and systematization of the deeper context of local knowledge. It is recommended that provincial cultural and tourism departments take the lead, collaborating with universities, research institutions, and local cultural workers to conduct in-depth cultural surveys following a “one village, one archive” approach, focusing on recording oral traditions, ecological wisdom, and community memories that have not yet been textualized. The decoding work should not be outsourced solely to design teams disconnected from the local context. Instead, a collaborative research mechanism involving “scholars + villagers + creators” should be established to ensure that the right to cultural interpretation remains partly within the community. For transformation outcomes, a cultural authenticity assessment process should be set up to prevent the emergence of “pseudo-cultural and creative products” that are divorced from their context and distort the original meaning.

- (2)

Construct a collaborative governance framework of “government guidance—villager-led—market operation—academic support,” clarifying the boundaries of rights, responsibilities, and benefits for all parties. The role of government should transition from a “dominant actor” to an “enabler” and “service provider,” focusing on institutional supply, infrastructure construction, and the maintenance of a fair market environment. Examples include establishing special funds for rural cultural and creative development, simplifying approval processes for cultural micro-enterprises, and building shared digital resource platforms. The principal role of villagers in industrial development must be strengthened, promoting practical models such as “transforming resources into assets, funds into shares, and villagers into shareholders,” and encouraging the contribution of skills, houses, land, etc., as shares to participate in profit distribution. Simultaneously, support should be given to the development of social intermediary organizations like industry associations and cooperatives, enabling them to serve as crucial buffers linking farmers with the market and balancing commercial interests with cultural preservation.

- (3)

Innovate mechanisms for cultivating and retaining rural cultural and creative talents to address the “talent shortage” dilemma. Efforts should focus on nurturing both “local experts” and “rural innovators,” as well as attracting “new farmers” and “returnees.” Recommendations include the following: (1) incorporating local traditional skills and folk knowledge into the local education curriculum of county-level primary and secondary schools to sustain the community foundation of cultural heritage; (2) implementing a “rural cultural and creative broker” training program, emphasizing the enhancement of capabilities in product development, brand storytelling, digital marketing, and intellectual property operation; (3) providing returning entrepreneurial youth with a “policy package” including startup funding, venue leasing, tax reductions, and children’s education support, while establishing cross-regional entrepreneur community networks to foster experience exchange and mutual emotional support; (4) encouraging universities and vocational colleges to establish “paired stations” with key villages, extending classrooms to the fields, and promoting student and teacher participation in rural construction through study, practical training, and project-based engagements.

- (4)

It is crucial to bolster technological empowerment and foster digital inclusion, while simultaneously maintaining vigilance against the potential for cultural alienation in the application of such technologies. Proactive measures should involve leveraging digital tools for high-definition capture, three-dimensional reconstruction, and dynamic documentation of endangered cultural heritage, thereby creating an openly accessible digital repository for rural culture. The use of new media platforms—including short-form video, live streaming, and virtual or augmented reality—should be encouraged to amplify rural narratives. However, a critical stance must be upheld toward a purely “traffic-first” mentality. Platforms ought to prioritize visibility and allocate resources toward creators who produce substantive content and convey authentic rural experiences. When integrating tools like AI-aided design and big data analytics into the creative process, an ethical review framework should be instituted. This ensures that technological application preserves, rather than erodes, the authentic essence of cultural meaning, and serves to augment—not replace—human creative agency.

- (5)

It is essential to explore business models that are sustainable both ecologically and culturally, while establishing a long-term developmental evaluation system. There should be a shift away from assessment methods that rely solely on short-term tourism revenue as a single indicator. Instead, a comprehensive evaluation framework should be developed, covering multiple dimensions such as cultural heritage transmission, community participation, ecological impact, and economic benefits. The development of eco-cultural and creative projects characterized by “light investment, integration with nature, and enriched experiential depth” should be encouraged. A “negative list” for rural cultural development should be established, explicitly prohibiting actions that compromise historical integrity, lead to excessive commercialization, or cause environmental pollution. Furthermore, the creation of a “Rural Cultural Revitalization Fund” should be promoted, allocating a certain percentage of revenue from cultural and tourism projects to reinvest in cultural heritage protection, public cultural services, and community welfare.

- (6)

Efforts should be made to promote the creative transformation of rural culture from “local knowledge” into a “globally dialogic discourse.” Qualified rural cultural projects should be supported in connecting with internationally renowned art festivals, design exhibitions, and academic forums, fostering in-depth exchanges such as residency programs and collaborative curatorial initiatives. Funding should be allocated to academic journals, publishers, and other platforms to systematically translate and introduce representative cases and theoretical reflections on rural innovation in China, thereby engaging in international academic dialogs on rural revitalization, cultural heritage, and ecological civilization. Throughout this process, cultural subjectivity must be upheld, avoiding self-exoticizing repackaging merely to cater to external perspectives. Instead, there should be a dedicated effort to distill and disseminate Chinese rural wisdom and practical solutions that carry universal significance.