1. Introduction

Polyurethanes (PUR) represent one of the most versatile groups of polymers and are widely applied across numerous branches of industry. Their chemical structure is formed through the polyaddition reaction of isocyanates with polyols, resulting in the formation of urethane bonds (–NH–COO–), which determine their physicochemical properties [

1]. Depending on formulation and synthesis conditions, polyurethanes can be produced as flexible elastomers or rigid foams with a closed-cell structure. Owing to their favorable combination of chemical resistance, thermal and acoustic insulation, and mechanical strength, PUR materials are indispensable in many engineering applications [

2,

3,

4].

Due to these properties, polyurethanes are extensively used in construction as spray foams and rigid insulation boards, in the automotive industry for interior components, in furniture manufacturing as flexible upholstery foams, and in thermal and acoustic insulation systems. In addition, PUR materials are applied in medicine, adhesives, protective coatings, and varnishes, where durability and resistance to environmental factors are required [

5,

6,

7].

Among the various polyurethane materials, rigid polyurethane foams (RPUFs) play a particularly important role in modern industrial technologies. Their low thermal conductivity makes them irreplaceable insulation materials in construction and refrigeration applications [

8,

9,

10,

11]. The closed-cell structure of RPUFs ensures high mechanical strength, dimensional stability, and excellent dielectric properties, enabling their use in electrical engineering. Furthermore, their resistance to chemicals and moisture allows application in pipeline insulation, storage tanks, and protective systems [

12,

13,

14].

Despite these advantages, RPUFs exhibit several critical limitations that restrict their broader application. The most significant drawback is their high flammability, which poses serious fire safety concerns. Thermal degradation begins at approximately 200 °C with the breakdown of urethane bonds, while complete decomposition occurs above 300 °C, accompanied by the release of flammable and toxic gaseous products such as CO, CO

2, and HCN [

15,

16,

17]. Additionally, RPUFs show limited resistance to long-term mechanical loading, leading to crushing and deformation under dynamic conditions [

18]. Recycling of rigid polyurethane foams remains challenging due to their complex crosslinked structure, which is inconsistent with circular economy principles [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23].

To address these limitations, extensive research has focused on modifying RPUFs using mineral fillers, which can enhance thermal stability, mechanical performance, and fire resistance while maintaining low density [

24,

25]. Natural minerals such as calcium bentonite, almandine (garnet), halloysite, meionite, sepiolite, montmorillonite, and clinoptilolite have been reported to improve selected properties of polyurethane foams by acting as structural reinforcements, thermal barriers, and suppressants of smoke and toxic gas evolution [

15,

16]. These fillers may also reduce the need for synthetic additives, contributing to more sustainable material solutions.

However, most previously reported studies investigate individual mineral fillers or apply different formulations and processing conditions, which makes direct comparison of their effects difficult and often inconclusive. As a result, there is a lack of systematic knowledge regarding how different natural minerals, introduced under identical technological conditions, influence foaming behavior, cellular structure, and the resulting macroscopic properties of rigid polyurethane foams [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36].

The scientific novelty of the present study lies in a systematic and comparative evaluation of a broad range of natural mineral fillers incorporated into rigid polyurethane foams using a unified formulation and processing framework. By maintaining constant synthesis parameters, the observed differences in foaming kinetics, cellular morphology, mechanical performance, thermal stability, dimensional stability, and moisture-related properties can be directly attributed to the intrinsic physicochemical characteristics and morphology of the mineral fillers. This approach enables a reliable structure–process–property analysis that is rarely addressed in an integrated manner for mineral-modified polyurethane foams.

The results demonstrate that natural minerals do not act merely as passive fillers but perform distinct functional roles within the polyurethane matrix, including mechanical reinforcement, thermal stabilization, modulation of dimensional stability, and control of moisture uptake. Such functional differentiation enables a rational, application-oriented selection of mineral additives, replacing empirical trial-and-error approaches commonly used in foam formulation. From a sustainability perspective, the use of naturally occurring, low-cost mineral fillers represents an effective strategy for reducing reliance on synthetic modifiers while maintaining or improving key performance parameters of rigid polyurethane foams. To the authors’ knowledge, no previous study has reported such a comprehensive, side-by-side comparison of multiple natural mineral fillers in rigid polyurethane foams under strictly identical formulation and processing conditions. This approach provides practical guidelines for selecting mineral fillers tailored to specific performance requirements of insulation materials, rather than relying on empirical formulation strategies.

The aim of this study is to evaluate the influence of selected natural minerals on the physical, mechanical, and thermal properties of rigid polyurethane foams. The investigation employs scanning electron microscopy (SEM) for microstructural analysis, density and water absorption measurements, dimensional stability testing at elevated temperatures, thermogravimetric and calorimetric analysis (TGA/DSC), thermal conductivity measurements, and flammability assessment using the limiting oxygen index (LOI) method. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was additionally applied to examine possible interactions between mineral fillers and the polyurethane matrix. The study focuses on the macroscopic performance and durability-related properties of the foams rather than on detailed surface chemistry or interfacial bonding mechanisms.

The ultimate goal of this work is to assess the potential of natural minerals as environmentally friendly alternatives to synthetic additives in rigid polyurethane foams, with particular emphasis on durability, thermal stability, and sustainability in line with current resource-efficiency and circular economy principles.

2. Results

Table 1 presents the results of studies on the effect of natural minerals, used as fillers, on the foaming behavior of polyurethane foams. The key parameters of the process—creaming time, rise (expanding) time, and drying time—were analyzed for different minerals, including calcium bentonite, almandine, halloysite, mironecton, sepiolite, montmorillonite, and clinoptilolite. The reference foam (4.0), without any filler, exhibited a creaming time of 68 s, a rise time of 43 s, and a drying time of 0 s. These values served as the baseline for comparison.

The addition of calcium bentonite (4.3) increased the creaming time to 94 s, indicating a slower foaming reaction. Due to its high specific surface area and adsorption capacity, bentonite can interact with water and polyurethane reactants, reducing the rate of the polyaddition reaction. The rise time (42 s) remained close to the reference value, suggesting a stabilizing effect of bentonite on the foam’s cellular structure.

For almandine (4.4), the creaming time was 86 s, while the rise time decreased to 31 s. The shorter rise time compared with the control foam may result from the high hardness and low permeability of the mineral, which hinders gas propagation. Consequently, the foam achieves dimensional stability more quickly.

Halloysite (4.5) showed the longest creaming time of all fillers (103 s), indicating a significant delay in the initial foaming stage. Its nanotubular structure allows the adsorption of reactants (polyols and isocyanates), prolonging the network formation. The rise time (40 s) also suggests slower gas release and expansion, which may lead to a more uniform and stable cell structure.

Mironecton (4.6) exhibited a creaming time of 89 s and a relatively short rise time of 31 s, indicating a moderate influence on the initial reaction stage combined with faster stabilization of the foam structure. A similar effect was observed for montmorillonite (4.8), with a creaming time of 86 s and a rise time of 34 s. Both clay minerals, due to their layered structure and hydrophilicity, delay the early reaction phases while stabilizing foam expansion.

Sepiolite (4.7) demonstrated a shorter creaming time (81 s) and a rise time of 33 s. Its fibrous structure may facilitate easier gas diffusion during the reaction, accelerating foam expansion. An even faster effect was observed for clinoptilolite (4.9), a natural zeolite, which exhibited the shortest creaming time (79 s) and rise time (28 s). The water adsorption and ion-exchange capacity of clinoptilolite enhance CO2 generation through the isocyanate–water reaction, resulting in faster foaming.

For all tested samples, the drying time remained constant at 0 s, indicating that, regardless of the filler type, the foams were fully dry after growth and did not adhere to powder substances, eliminating the need for an additional drying stage.

In summary, the results demonstrate that clay minerals (bentonite, montmorillonite, mironecton) and halloysite slow down the initial foaming stages, which promotes structural stabilization and potentially improves mechanical properties. Conversely, minerals such as almandine, sepiolite, and clinoptilolite accelerate the process, leading to more dynamic foam expansion but potentially lower long-term stability. Appropriate selection of fillers thus provides an effective tool for controlling both the foaming kinetics and the final performance of polyurethane foams.

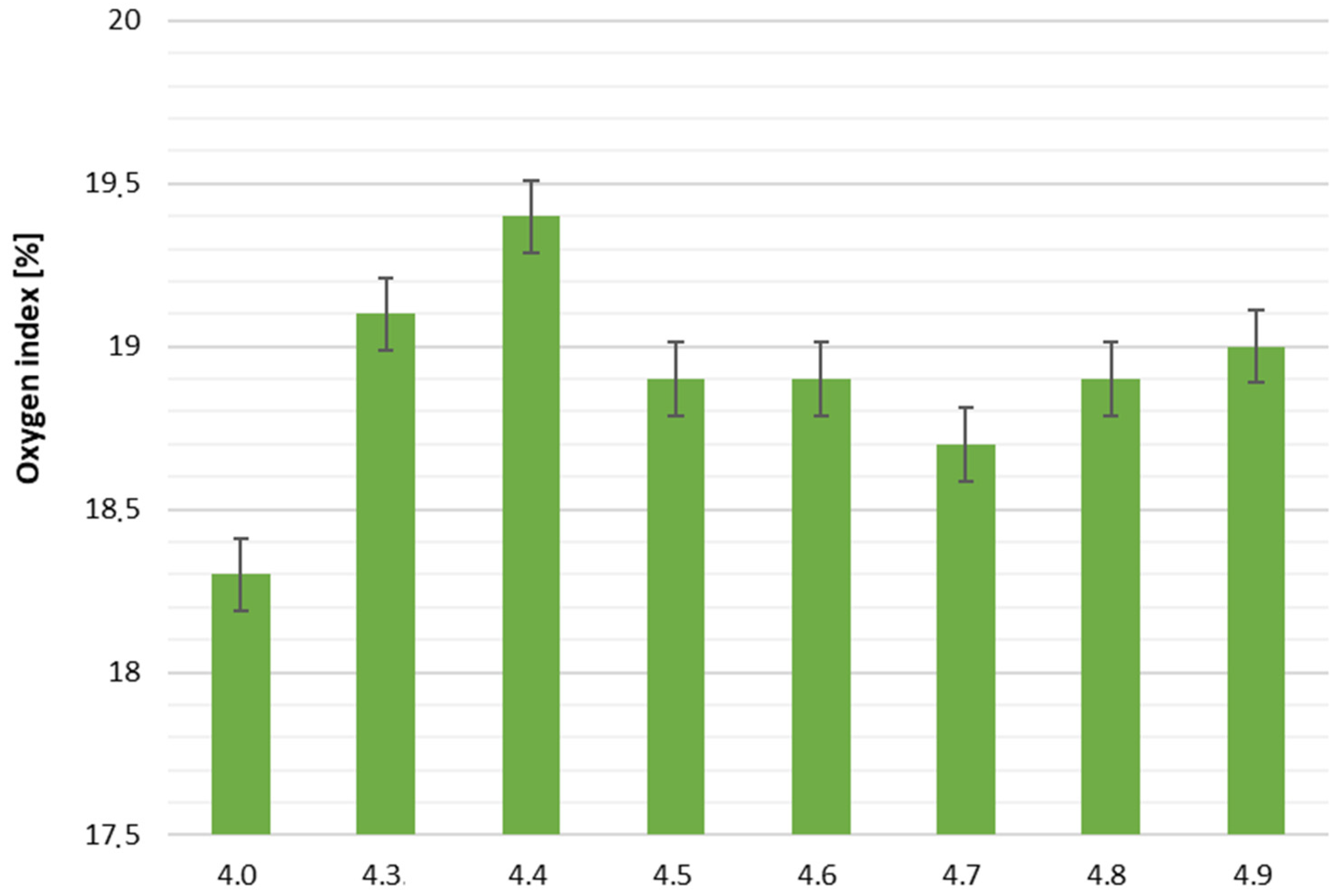

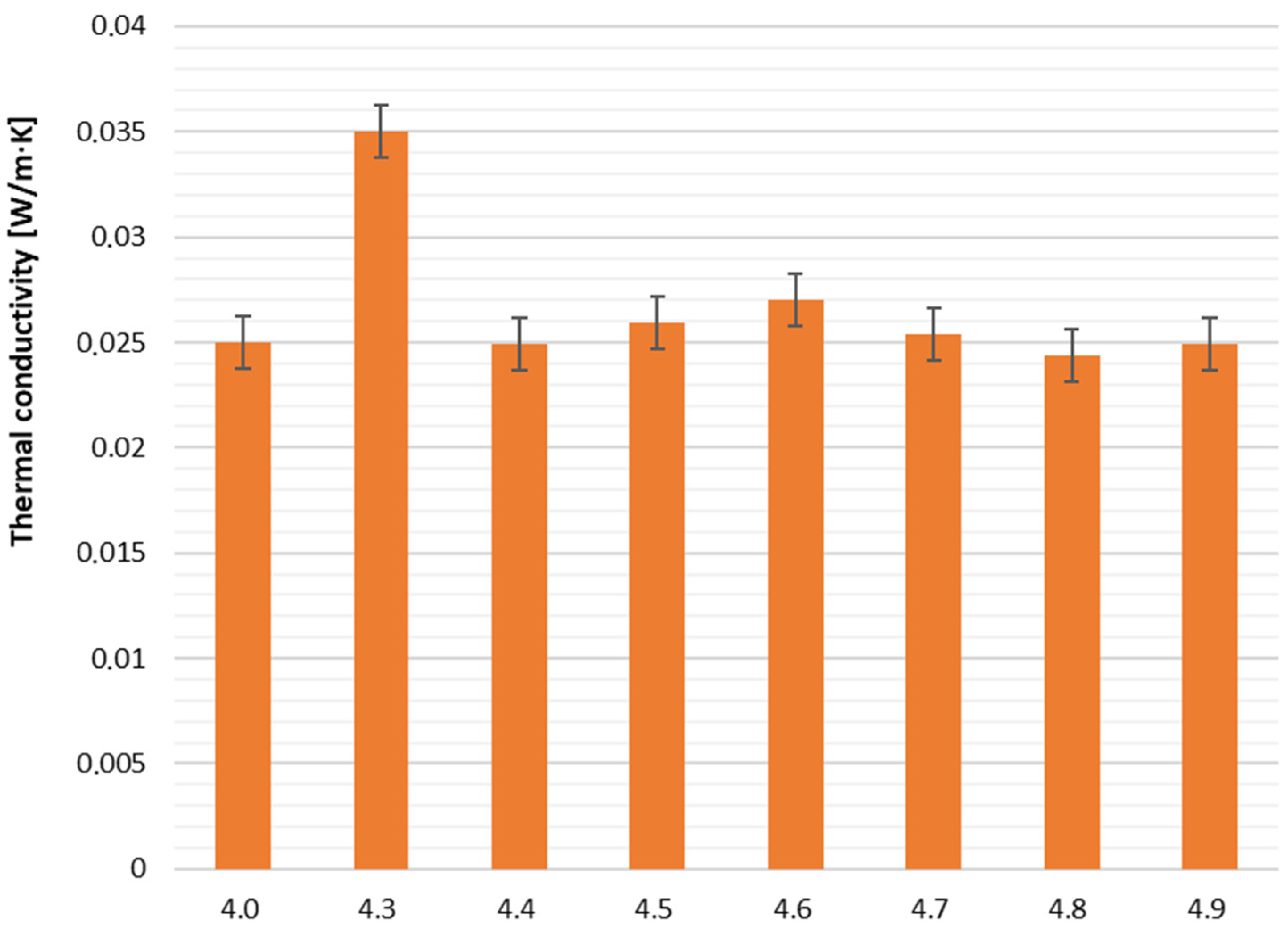

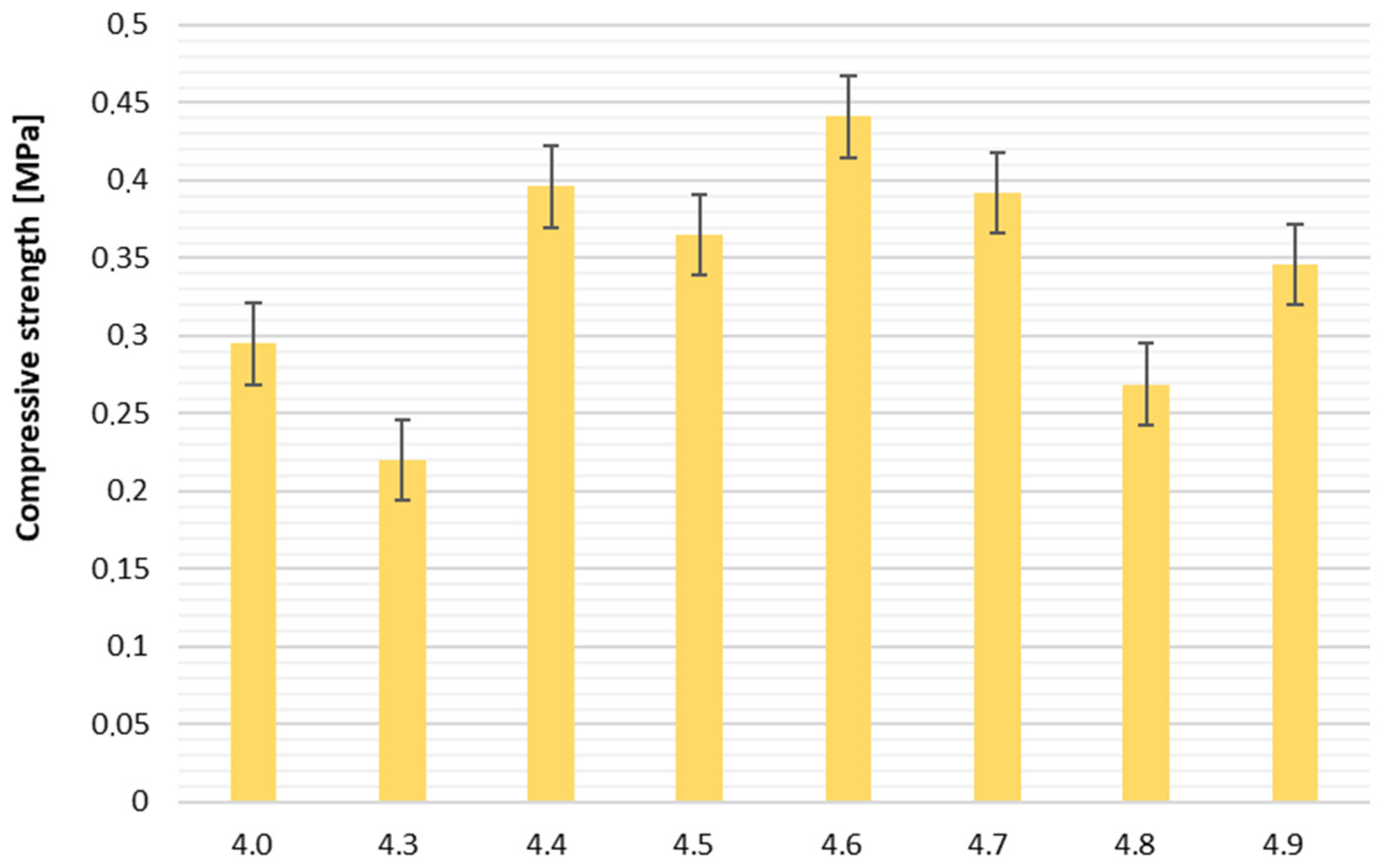

Table 2 and

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 present the results of physical measurements for various polyurethane foam samples, differing in the type of filler used. The study analyzed apparent density, water uptake, thermal conductivity coefficient (Λ), and oxygen index (OI). Water uptake was measured at specific time intervals—after 5 min, 3 h, and 24 h of immersion—according to the standard PN-EN ISO 845:2018-12 [

37].

The apparent density of the foams with mineral fillers ranged from 55.74 kg/m3 (sample 4.3) to 65.62 kg/m3 (sample 4.6), while the reference foam without filler (sample 4.0) had a density of 69.59 kg/m3. Higher density indicates a more compact structure, which can improve mechanical strength but may slightly reduce thermal insulation performance. Conversely, lower-density foams, such as 4.3, are lighter and may provide better thermal insulation, although their mechanical strength is lower. These differences are important when selecting foams for specific industrial applications.

Water uptake varied significantly among samples, which is critical for applications in high-humidity environments. Sample 4.6 exhibited the lowest water absorption after 5 min (1.00 vol.%), indicating good initial moisture resistance. Samples 4.3 (1.30 vol.%) and 4.9 (1.55 vol.%) absorbed more water. After 24 h, the differences became more pronounced, ranging from 2.19% (sample 4.4) to 5.93% (sample 4.9). All foams except 4.9 showed lower water uptake than the reference foam 4.0 (3.83%), suggesting a generally positive effect of mineral fillers on moisture resistance. The higher water uptake of clinoptilolite (4.9) reflects its porous structure and strong water adsorption capacity.

The thermal conductivity coefficient (Λ) is a key parameter for evaluating insulation performance, with lower values indicating better thermal insulation. For the tested samples, Λ ranged from 0.0244 W/m·K (sample 4.8) to 0.0350 W/m·K (sample 4.3), demonstrating generally favorable insulation properties. These variations can influence foam selection depending on specific thermal requirements.

The oxygen index (OI) of all samples ranged from 18.3% to 19.4%, indicating that the foams remain highly flammable. While the addition of mineral fillers slightly increased the oxygen index compared to the reference foam (18.3%), the highest value (19.4% for sample 4.4) still corresponds to easily flammable materials. Therefore, any claims regarding improved fire resistance should be interpreted cautiously, and the foams should be considered readily flammable.

Compressive strength ranged from 0.220 MPa (sample 4.3) to 0.441 MPa (sample 4.6), with the reference foam 4.0 exhibiting 0.295 MPa. Sample 4.6 showed the highest mechanical resistance, making it suitable for applications requiring higher load-bearing capacity.

In summary, the type of mineral filler significantly affects the physical properties of polyurethane foams, including density, water absorption, thermal conductivity, and mechanical strength. Fillers influence moisture uptake and thermal performance, while their effect on flammability is limited. Selecting the appropriate filler allows optimization of foam properties for specific applications, considering both mechanical and thermal requirements as well as the inherent flammability of the material.

Studies on the dimensional stability of polyurethane foams at elevated temperature (150 °C) revealed significant differences in the behavior of individual samples. Dimensional changes, measured after 20 and 40 h of exposure, included variations in length, width, and thickness, and were expressed as percentages relative to the initial dimensions of the materials (

Table 3,

Figure 5).

Regarding length changes, the largest deformations occurred in foams containing sepiolite (4.7) and clinoptilolite (4.9), whose lengths decreased by −25.52% and −30.30%, respectively, after 40 h. The high susceptibility of these foams to temperature exposure is associated with the presence of structural and adsorbed water in the porous, channel-like mineral structures, leading to dehydration and partial collapse of the crystalline framework. In contrast, samples 4.3 (calcium bentonite) and 4.5 (halloysite) exhibited relatively small length changes (+0.48% and −4.08% after 40 h, respectively), indicating improved dimensional stability. This behavior can be attributed to the more stable layered structure of calcium bentonite and the regular morphology of halloysite, which contains little interlayer water.

Analysis of width changes showed the largest deformations in samples 4.3 (−11.84%) and 4.6 (mironekuton, −10.12%) after 40 h. In bentonite-filled foams, the anisotropic shrinkage is related to the orientation of aluminosilicate layers within the polymer matrix, while in mironekuton-containing samples, the presence of numerous hydrophilic groups may promote localized structural rearrangements. The smallest width changes were observed in the reference foam (4.0) and sample 4.5 (halloysite), suggesting that both the absence of fillers and the presence of low-hydrated mineral phases limit lateral deformations.

The largest reductions in thickness were again observed for foams containing sepiolite (4.7, −27.16%) and clinoptilolite (4.9, −31.46%), resulting from intensive dehydration and collapse of their porous structures. In contrast, samples 4.6 (mironekuton) and 4.8 (montmorillonite) showed thickness changes not exceeding 5%, which can be attributed to strong interlayer interactions in montmorillonite and the fine-grained structure of mironekuton, which restricts deformation perpendicular to the layers.

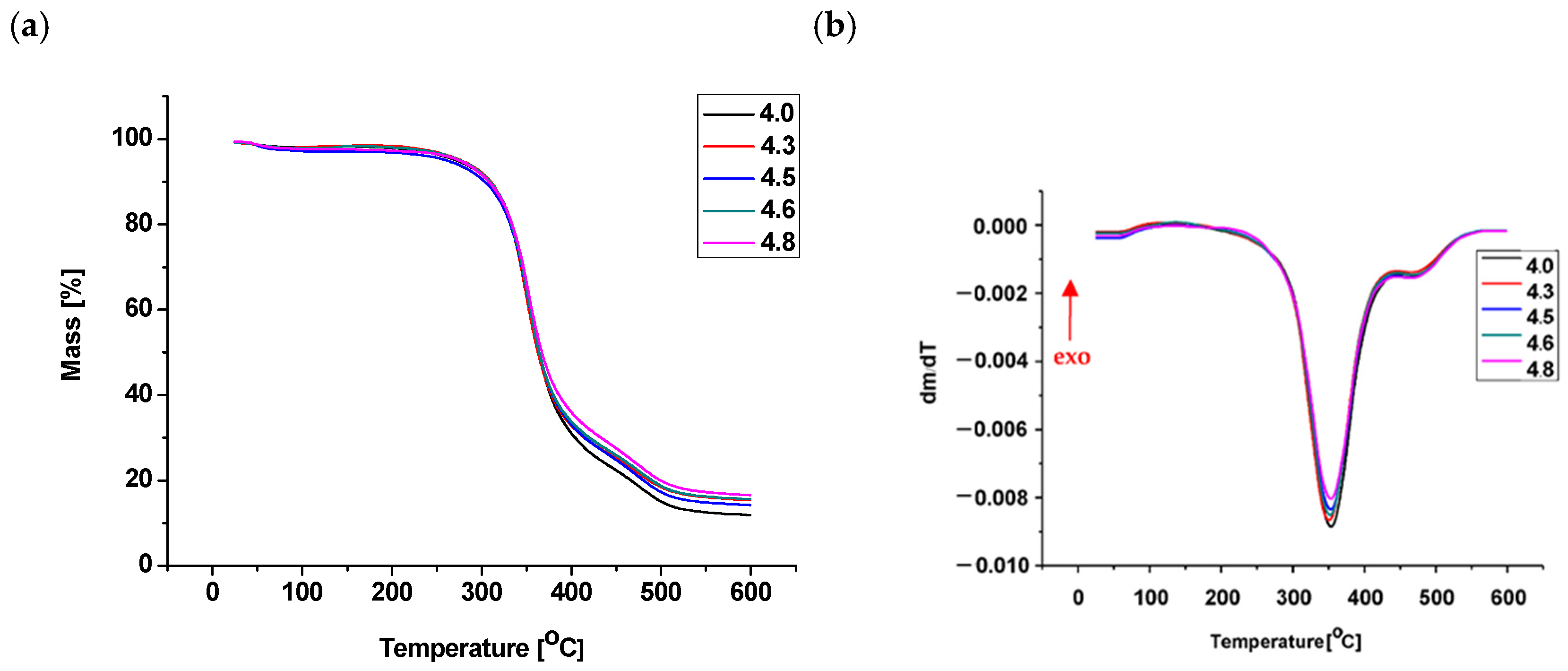

Thermogravimetric analysis (TG and DTG) indicated that all foams exhibited similar degradation profiles, particularly in the temperature range of 250–290 °C, suggesting that the degradation mechanism of the polyurethane matrix was essentially unchanged by the addition of mineral fillers. The temperature corresponding to 5% mass loss ranged from 240 to 277 °C, with slightly higher values observed for samples containing calcium bentonite (4.3), mironekuton (4.6), and montmorillonite (4.8) compared to the unfilled foam (4.0). These differences indicate a moderate improvement in thermal resistance, which can be attributed to the physical barrier effect of the mineral fillers rather than a significant enhancement of intrinsic thermal stability. The temperature of maximum degradation rate was similar for samples 4.0, 4.5, and 4.8 (approximately 353 °C).

In summary, the results demonstrate that dimensional stability at elevated temperature strongly depends on the type of mineral filler. Foams containing calcium bentonite, halloysite, mironekuton, and montmorillonite exhibited relatively better resistance to deformation at 150 °C, whereas samples containing sepiolite and clinoptilolite showed pronounced dimensional changes, limiting their suitability under such conditions. While thermogravimetric analysis reveals only minor changes in thermal degradation behavior, the appropriate selection of mineral fillers can improve resistance to thermal deformation through structural and physical effects.

Thermal analysis (TG) and DTG confirmed that the obtained foams exhibited good thermal resistance (

Table 4,

Figure 5). The introduction of mineral fillers increased the onset temperature of decomposition compared to the unfilled foam. Specifically, the onset temperature rose from 236 °C in the unfilled foam (4.0) to 248 °C and 244 °C in foams 4.3 and 4.6, containing calcium bentonite and mironekuton, respectively. In contrast, foams 4.8 and 4.5 showed lower onset temperatures of decomposition, at 227 °C and 187 °C, respectively.

The temperature at which the foams lose 5% of their mass fell within a narrower range of 283–294 °C. Sample 4.3 exhibited the highest temperature for 5% mass loss, confirming that the incorporation of calcium bentonite positively influences the thermal stability of the foam. Foam 4.6 also showed an improved 5% mass loss temperature of 276 °C compared to foam 4.8 (291 °C) and the unfilled foam 4.0 (T5% = 291 °C), demonstrating that the use of mineral fillers—bentonite and mironekuton—enhances the thermal properties of the polyurethane foams.

The temperature of maximum decomposition rate was similar for all foams, ranging from 351 to 353 °C. The addition of mineral fillers also increased the residue remaining after decomposition up to 600 °C. The highest residue was observed in foam 4.8, containing montmorillonite, at 18.6% by weight, compared to 13.9% for the unfilled foam.

These results indicate that the presence of mineral fillers such as calcium bentonite, montmorillonite, and mironekuton improves the thermal behavior of polyurethane foams by delaying the onset of mass loss and helping maintain structural integrity at elevated temperatures.

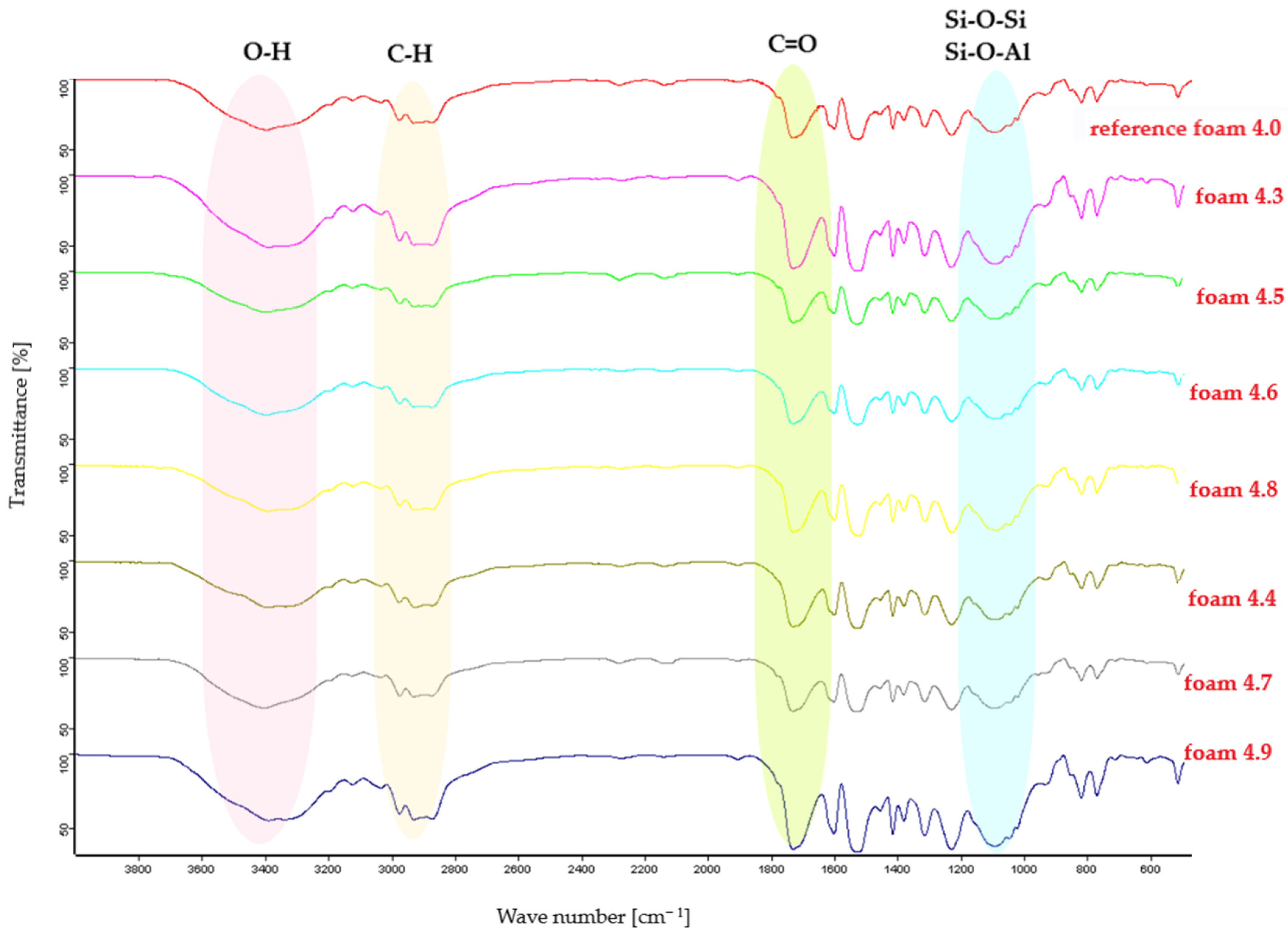

Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was employed to identify functional groups and to assess the influence of mineral fillers on the chemical structure of polyurethane foams. The FTIR spectrum of the unfilled polyurethane foam exhibits characteristic bands at approximately 3300 cm−1, corresponding to N–H stretching vibrations, 2900 cm−1 associated with C–H stretching vibrations, and a band near 1700 cm−1 attributed to C=O stretching vibrations, which are typical of the polymer matrix.

The incorporation of mineral fillers leads to the appearance of additional absorption bands characteristic of silicate materials, as well as to changes in band intensity and slight shifts in band positions. Clay-based fillers such as calcium bentonite and montmorillonite display broad hydroxyl bands in the 3600–3400 cm−1 range, related to the presence of interlayer water, and a band near 1650 cm−1, attributed to adsorbed surface water. The intense band observed in the 1100–1000 cm−1 region corresponds to overlapping stretching vibrations of the silicate framework, involving Si–O–Si and Si–O–Al bonds, which are typical of aluminosilicate structures. Minor differences in band positions between calcium bentonite and montmorillonite can be associated with the presence of Ca2+ ions in the interlayer structure.

Almandine (garnet), as a silicate mineral with a different crystal structure, exhibits strong Si–O vibration bands in the 1000–800 cm−1 region with minimal hydroxyl absorption, distinguishing it from clay minerals. Sepiolite is characterized by the presence of hydroxyl bands and an intense silicate framework band in the 1100–1000 cm−1 region, as well as additional bands in the 700–500 cm−1 range associated with Mg–OH vibrations. Halloysite exhibits pronounced hydroxyl bands in the 3690–3260 cm−1 region, indicative of structural water, whereas clinoptilolite, a zeolitic aluminosilicate, shows characteristic Si–O–Al framework bands in the 1100–1000 cm−1 region and a band near 1650 cm−1 corresponding to adsorbed water.

The FTIR spectra highlight differences in structural water content, hydroxyl group availability, and silicate framework structure among the fillers. Overall, FTIR analysis confirms the presence of characteristic mineral absorption bands within the polyurethane matrix and enables differentiation of the applied fillers based on variations in band intensity and position, without indicating the formation of new chemical bonds (

Figure 6).

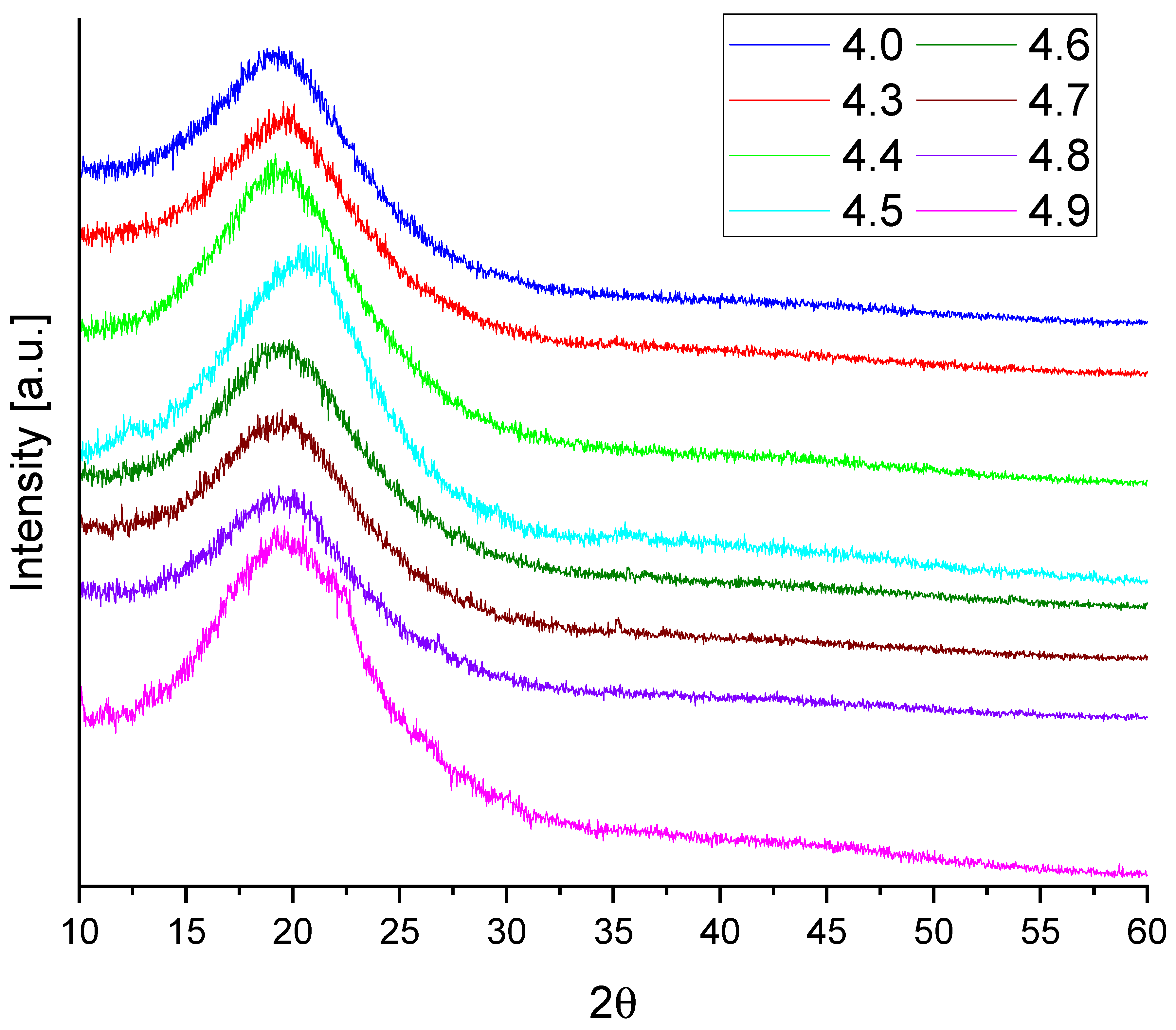

Figure 7 shows the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the reference polyurethane foam (sample 4.0) and foams modified with various fillers. All samples exhibit a broad diffraction maximum in the range of 2θ ≈ 10–30°, which is typical for amorphous polymeric materials. This diffractogram shape is characteristic of polyurethane, reflecting the absence of long-range crystalline order in its structure.

The addition of fillers did not result in the appearance of new sharp peaks or notable shifts in the main maximum, suggesting that the fillers were well dispersed within the polyurethane matrix and did not form detectable crystalline phases.

For samples containing calcium bentonite and mironekuton (4.3 and 4.6), the diffraction patterns were virtually indistinguishable from the reference foam. A slight decrease in the intensity of the main peak was observed for composites with sepiolite and montmorillonite (4.7 and 4.8), which may indicate a disruption in the local arrangement of polymer chains.

In contrast, samples modified with almandine, halloysite, and clinoptilolite (4.4, 4.5, and 4.9) showed an increase in peak intensity, suggesting a tendency toward more locally ordered structures in the presence of these fillers. These observations indicate that almandine, halloysite, and clinoptilolite may promote partial organization of the polyurethane matrix, whereas sepiolite and montmorillonite appear to inhibit this effect.

Similar effects of different silica types on XRD peak intensity in polyurethane-based composites have been previously reported by Nunes et al. [

38].

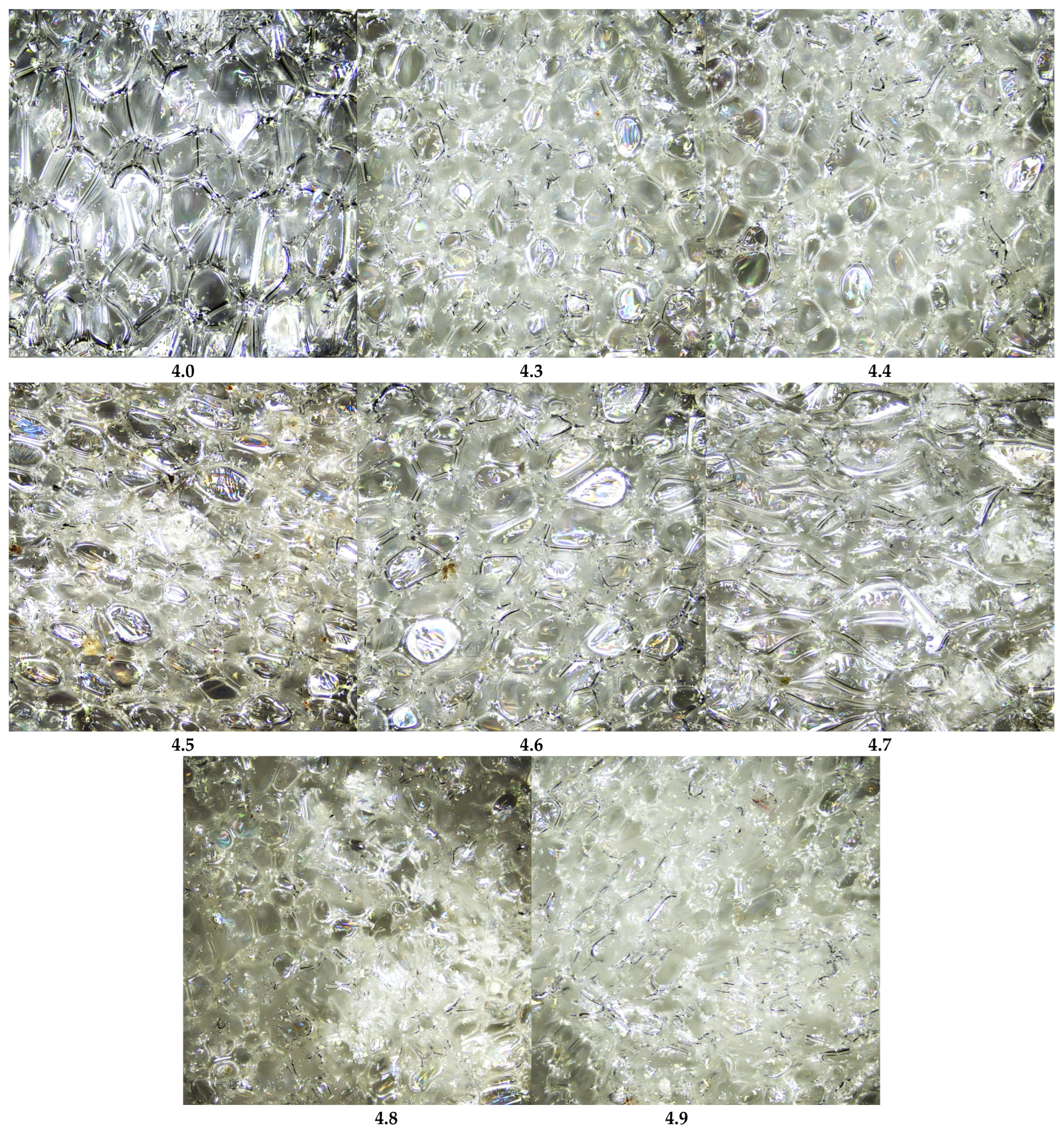

Figure 8 presents laser scanning microscope (LSM) images of the studied polyurethane foams. The reference foam (sample 4.0), without any additives, exhibits an open-cell structure with thin, transparent walls separating air-filled voids. Most cells are oval or polyhedral, typical of polyurethane foams. Minor local deformations are observed, likely due to internal stresses developed during foaming and curing. The smooth, transparent walls indicate good chemical uniformity and the absence of solid-phase additives. Partial interconnections between cells suggest a partially open porous structure, facilitating air permeability.

The introduction of mineral fillers significantly alters the foam morphology. In sample 4.3 (calcium bentonite), cells are smaller, more densely packed, and occasionally flattened, with thicker, less transparent walls. Sample 4.4 (almandine) displays medium-sized but highly irregular cells, thickened and uneven walls, and visible filler agglomerates. Sample 4.5 (halloysite) retains relatively uniform small-to-medium cells, slight wall thickening, matte surfaces, and occasional small filler clusters.

In sample 4.6 (palygorskite, mironekuton), cells are flattened and elongated with thicker matte walls, and the filler appears as darkened zones and clusters. Sample 4.7 (sepiolite) exhibits a looser, heterogeneous structure with varying cell sizes, thickened walls, occasional defects, and fine fibrous inclusions. Sample 4.8 (montmorillonite) shows very small, densely packed, irregular cells with rough matte walls and dark zones indicating filler presence. Sample 4.9 (clinoptilolite) displays a highly heterogeneous structure with elongated or distorted cells, thick and partially discontinuous walls, and visible filler streaks and agglomerates.

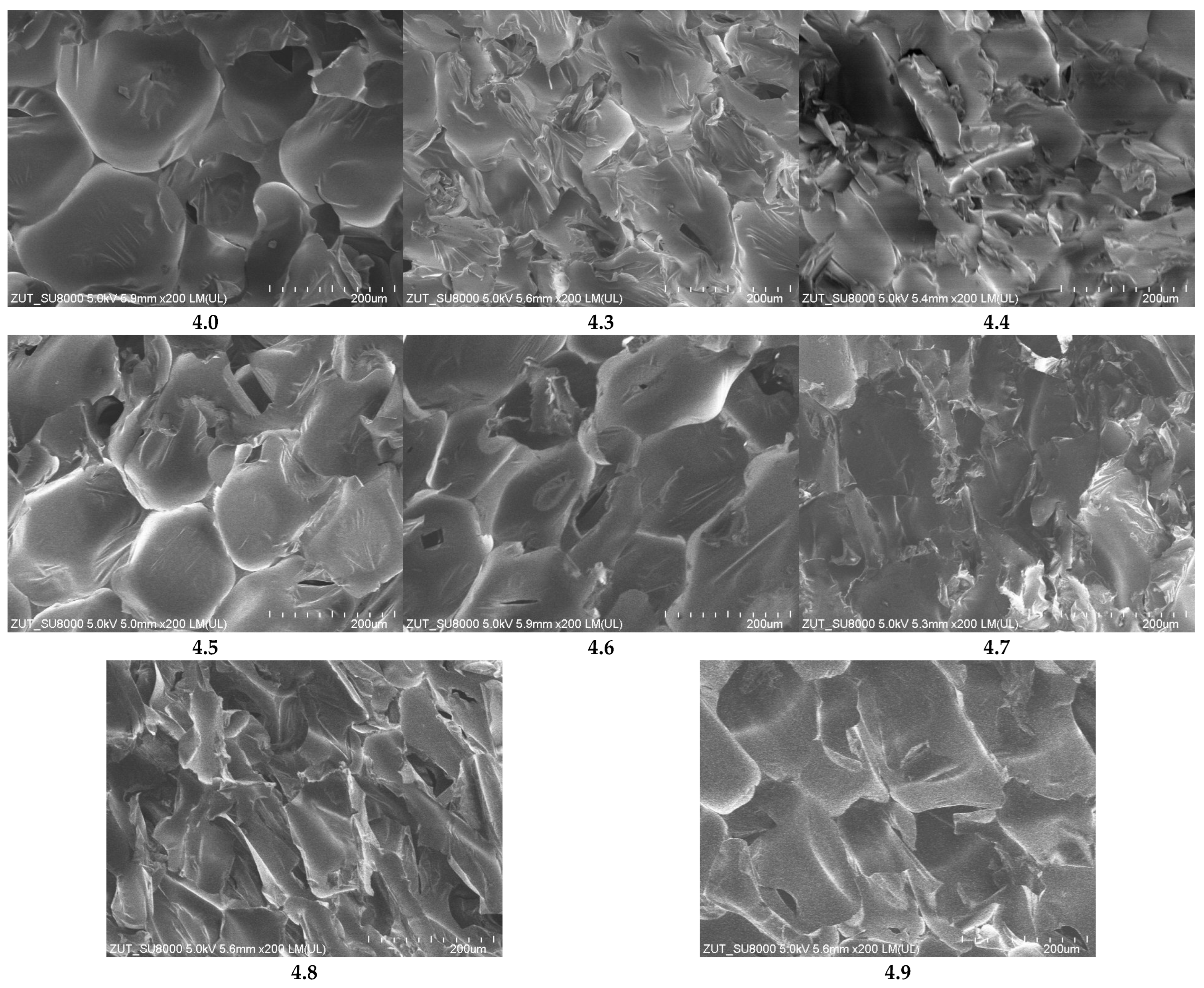

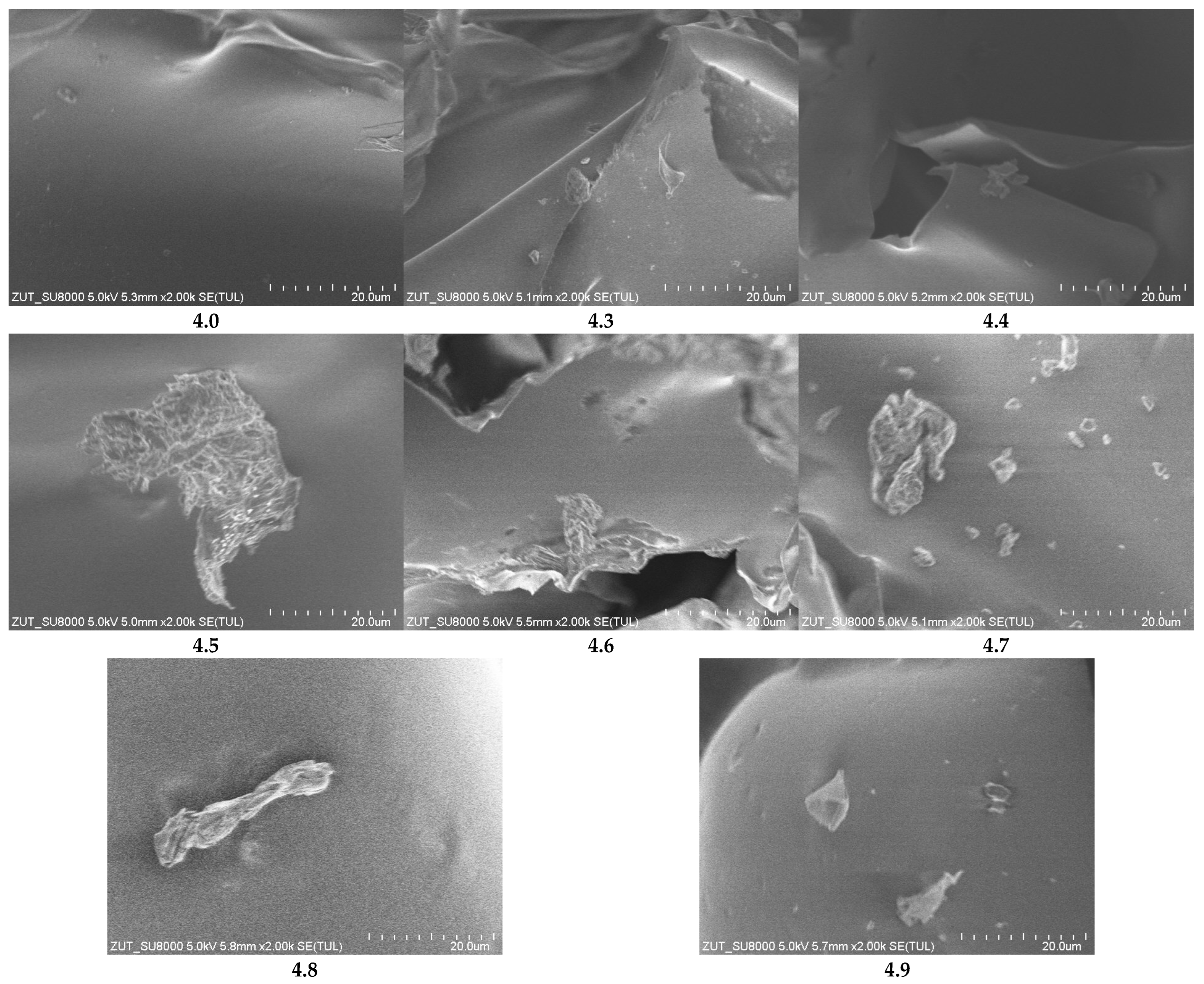

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images at 200× magnification (

Figure 9) confirm the trends observed in LSM. The reference foam shows well-defined cells with thin, smooth walls forming a regular, defect-free structure. Foams with fillers exhibit more compacted, irregular, or elongated cells with locally thickened or uneven walls. Significant microstructural disruption is particularly evident in samples 4.4, 4.7, and 4.9, with filler agglomerates and localized wall damage. Other samples display moderate morphological changes while retaining relatively ordered structures.

The addition of mineral fillers clearly affects the microstructure and surface morphology of polyurethane foams, influencing cell shape, wall thickness, and local heterogeneity. However, XRD and SEM analyses show no evidence of new crystalline phases or chemical bonding, and FTIR primarily reflects the chemical nature of the fillers themselves. Therefore, no definitive conclusions on chemical interactions between polyurethane and the minerals can be drawn from the current data. Complementary techniques, such as EDX or XPS, would be required to confirm potential polymer–filler interactions. Despite these microstructural changes, the bulk density of the foams remains relatively stable, indicating that local morphological modifications influence the microstructure more than the overall volumetric density.

Laser scanning microscopy (LSM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) were employed to examine the microstructure and surface morphology of polyurethane foams modified with various mineral fillers. The reference foam (sample 4.0), without additives, exhibited an open-cell structure with thin, transparent walls separating air-filled voids. Most cells were oval or polyhedral, typical of polyurethane foams, and only minor local deformations were observed, likely resulting from internal stresses during foaming and curing. The smooth and continuous cell walls confirmed the absence of solid-phase particles and good chemical uniformity. Partial interconnections between cells indicated a partially open porous structure, which could facilitate air permeability.

The addition of mineral fillers resulted in noticeable changes in foam morphology. Sample 4.3 (calcium bentonite) displayed smaller, more densely packed cells with occasional flattening and thicker, less transparent walls. Sample 4.4 (almandine) showed medium-sized but highly irregular and distorted cells, thickened and uneven walls, and visible filler agglomerates. Sample 4.5 (halloysite) retained relatively uniform small-to-medium cells, with slight wall thickening and occasional filler clusters. In sample 4.6 (palygorskite, mironekuton), cells were flattened and elongated, with thicker matte walls and darkened zones corresponding to filler clusters. Sample 4.7 (sepiolite) exhibited a looser, heterogeneous structure, with cells of varying size and shape, thickened walls, occasional defects, and fine fibrous inclusions characteristic of the filler. Sample 4.8 (montmorillonite) showed very small, densely packed, irregular cells with rough matte walls and darkened areas indicating filler presence. Finally, sample 4.9 (clinoptilolite) displayed a highly heterogeneous structure, with elongated or distorted cells, thick and partially discontinuous walls, and filler particles appearing as streaks or agglomerates.

High-magnification SEM images (2000×,

Figure 10) further highlighted the influence of fillers on cell wall topography. The reference foam exhibited smooth, homogeneous surfaces, while foams with fillers showed localized roughness, densifications, minor delamination, surface folding, microcracks, and protruding or partially embedded particles. The severity of surface disruption varied with filler type and was most pronounced in samples 4.4, 4.7, and 4.9.

These observations demonstrate that mineral fillers significantly affect the microstructure and surface morphology of polyurethane foams, modifying cell shape, wall thickness, and local heterogeneity. However, XRD patterns showed no new crystalline phases and only minor changes in peak intensity, and FTIR spectra primarily reflected the chemical characteristics of the fillers. Therefore, SEM and LSM observations alone cannot confirm chemical interactions between the polymer matrix and the fillers. Verification of polymer–filler chemical bonding would require complementary techniques such as EDX or XPS. Despite pronounced microstructural modifications, the bulk density of the foams remained relatively stable, indicating that local morphological changes influence microstructure and mechanical properties more than overall volumetric density.

The elemental composition of the studied sorption materials was determined via quantitative analysis, and the results are presented in

Table 5. Concentrations are reported as mass fractions [%] with corresponding statistical errors, indicating the reliability of the measurements.

The elemental composition reveals clear differences reflecting the mineralogical nature and potential sorption properties of the materials. The unfilled polyurethane foam contains only chlorine (0.237%, statistical error 2.86%), confirming its synthetic polymeric character and the absence of mineral fillers.

Calcium bentonite is primarily composed of iron (0.635%), silicon (0.398%), chlorine (0.201%), and calcium (0.167%), characteristic of a layered aluminosilicate structure with exchangeable cations, which can contribute to ion-exchange and adsorption processes. Almandine (garnet) is dominated by iron (0.565%) and chlorine (0.224%), reflecting its silicate garnet framework and suggesting limited cation-exchange capacity but potential for metal adsorption due to its iron content.

Halloysite exhibits a more complex composition, containing iron (2.109%), silicon (0.366%), chlorine (0.202%), aluminum (0.195%), and titanium (0.181%), indicative of a multi-element aluminosilicate structure with numerous active sites suitable for adsorption. Mironekuton shows a similar but slightly less diverse profile, with iron (0.567%), silicon (0.367%), calcium (0.240%), and chlorine (0.226%), suggesting moderate sorption capacity.

Sepiolite, with chlorine (0.222%), iron (0.188%), calcium (0.084%), and silicon (0.126%), has a fibrous clay structure that provides high surface area and potential for selective adsorption of ions or polar molecules. Montmorillonite contains silicon (1.08%), iron (0.410%), chlorine (0.208%), potassium (0.143%), and aluminum (0.105%), reflecting its layered silicate structure and high cation-exchange capacity. Clinoptilolite is characterized by silicon (1.14%), potassium (0.333%), iron (0.33%), calcium (0.302%), chlorine (0.207%), and aluminum (0.131%), consistent with its zeolitic framework and strong ion-exchange properties.

Overall, the results highlight significant compositional variability between synthetic and natural sorption materials. Clay minerals and zeolites exhibit multi-elemental profiles with high silicon, aluminum, and iron contents, supporting their structural complexity and high sorption potential. In contrast, polymeric foams and garnets show limited elemental diversity, correlating with lower sorption activity. These findings provide a comprehensive basis for understanding the chemical behavior of the materials and their potential applications in adsorption and polymer composite systems.