1. Introduction

The hospitality and tourism sector is among the most dynamic service sectors worldwide. Yet, it is increasingly criticized for its ecological footprint, and tourism contributes substantially to global greenhouse gas emissions through energy-intensive transportation, accommodation, and leisure activities [

1]. As climate change and biodiversity loss intensify, pressure from policymakers, environmental organizations, and consumers has accelerated the adoption of sustainability strategies within the industry. In response, hotels are increasingly positioning environmental responsibility not only as a moral obligation but also as a competitive differentiator, leading to growing consumer interest in green hotels and eco-certified services.

Green consumerism refers to deliberate choices favoring products and services that minimize environmental harm, including organic food, fair-trade goods, low-emission transport, and sustainable travel options [

2,

3]. In tourism and hospitality, such behavior extends beyond isolated transactions and reflects broader environmental values and social identity [

4]. Thus, preferences for eco-certified services, green hotels, and sustainable travel methods are examples of such behaviors in the context of tourism and hospitality. Therefore, green purchasing behavior is more than just a transactional decision; it also reflects social identity and broader environmental values [

5].

Several studies have identified several psychological and social determinants of green consumption [

6,

7], and the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) [

8] is one of the most adopted applied frameworks, proposing that subjective norms, attitude, and perceived behavioral control influence intentions, which subsequently shape behavior. While TPB has been effective in explaining pro-environmental actions, its explanatory power is limited in complex decisions such as hotel selection, where emotions, habits, and contextual constraints are highly influential [

9,

10]. In such contexts, emotions and habitual decision routines shape attitudes and perceived control, while post-intentional processes determine whether favorable intentions are translated into actual behavior. To address these limitations, scholars have incorporated additional variables, such as environmental concern, trust, and personal identity, thereby providing a more extensive understanding of consumer decision-making [

11,

12].

Within this framework, several antecedents stand out, and social influence and subjective norms remain essential drivers of green purchase intentions, particularly in collectivist or community-oriented societies where individuals seek validation from peers and significant others [

13]. Also, environmental knowledge provides consumers with the awareness to identify eco-friendly options and make informed choices [

14,

15]. In addition, the rapid digital transformation of markets has also made social media marketing a powerful influence on consumer attitudes, and social media platforms not only disseminate sustainability information but also foster engagement, co-creation, and peer endorsement of green brands [

16]. Furthermore, Cheung et al. [

17] propose that digital platforms play a critical role in building trust and forming a positive perception of eco-friendly hotels.

Another factor shaping consumer behavior is the visibility of organizational green practices; as consumers become more skeptical of superficial or unverifiable claims, they increasingly seek tangible evidence of environmental commitment. Eco-labels, third-party certifications, and transparent communication about sustainability initiatives serve as credible trust-building mechanisms, reinforcing positive attitudes toward green hotels [

18]. In addition, self-image in environmental protection, defined as the degree to which people consider themselves as environmentally responsible, has been shown to influence hotel choices that align with their desire to project a sustainable identity [

19,

20]. These factors collectively indicate that both personal motivations and organizational practices are critical in shaping green consumption.

Despite these advances, a persistent challenge in the literature is the intention–behavior gap: consumers often express strong pro-environmental intentions, but these do not always translate into actual purchases [

21]. One explanation lies in information-seeking behavior. Before making decisions, consumers frequently consult online reviews, sustainability disclosures, and third-party endorsements [

22]; such behavior helps reduce uncertainty, mitigates perceptions of risk, and enhances purchasing confidence. However, TPB-based studies provide limited and inconsistent evidence on whether information-seeking behavior strengthens the intention–behavior relationship or operates as an independent post-intentional driver of green hotel purchase behavior. Clarifying this role is essential for both theory and practice, as it can inform how hotels communicate sustainability initiatives to prospective guests.

Turkey provides a particularly relevant context for addressing these gaps. As a major tourism destination and emerging economy, Turkey faces challenges in balancing economic growth with environmental sustainability. Despite policy commitments to emissions reduction, international assessments highlight ongoing environmental performance concerns [

23,

24,

25]. Given the central role of tourism in Turkey’s economy, understanding the psychological, digital, and organizational drivers of green hotel consumer behavior offers valuable theoretical contributions and practical guidance for advancing sustainable tourism in emerging markets.

Research Gap and Contribution

Although the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) is widely used to explain pro-environmental consumption, important gaps remain in its application to green hotel behavior. Prior TPB-based hospitality studies have typically examined determinants such as environmental knowledge, social influence, or organizational practices in isolation, offering limited insight into their combined effects on consumer attitudes and decision-making. Consequently, the integrated influence of social media marketing, organizational green practices awareness, environmental knowledge, and self-image in environmental protection within a unified TPB framework remains insufficiently understood. Moreover, TPB assumes a direct progression from intention to behavior, yet hospitality research consistently reports an intention–behavior gap. Information-seeking behavior has been proposed as a mechanism to explain this discrepancy; however, empirical findings remain fragmented. Existing studies provide inconsistent evidence regarding whether information seeking strengthens the intention–behavior link, mediates this relationship, or operates as an independent post-intentional predictor in digitally mediated hotel booking contexts.

Finally, the majority of TPB-based green consumption research focuses on developed economies, limiting the generalizability of findings to emerging tourism markets. Countries such as Turkey, which are highly dependent on tourism but face sustainability governance challenges, remain underrepresented despite their growing global significance. To address these gaps, this study extends TPB by jointly examining multiple antecedents, clarifying the role of information-seeking behavior, and testing the model in Turkey’s hospitality sector. In doing so, it advances TPB theory and enhances the contextual relevance and explanatory power of green hotel consumer behavior research.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews the relevant literature and develops the study’s hypotheses.

Section 3 presents the research methodology and data sources.

Section 4 reports the empirical findings and provides the analysis.

Section 5 discusses these results in relation to prior studies.

Section 6 highlights the study’s limitations, offers directions for future research, and concludes by summarizing the main contributions, policy implications, and managerial recommendations.

2. Literature Review

Consumers are making increasingly ethical decisions as a result of growing environmental consciousness, and psychological theories of green consumption emphasize how moral principles, values, attitudes, and perceived behavioral control (PBC) influence intentions and behavior. Pro-environmental behavior is primarily motivated by psychological variables, including beliefs and motivations, while sociodemographic and contextual factors also play a part. According to the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), people should think about the effects of their actions before taking them [

26]. Building on this, the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) introduced the concept of perceived behavioral control, highlighting people’s capacity to act and anticipated outcomes [

8].

TPB has been used extensively to forecast green consumer behavior [

11,

12,

27,

28]. According to Judge et al. [

29], intentions to buy sustainable housing were significantly predicted by perceived behavioral control, subjective norms, and attitude. TPB is limited, though, because it presumes rational decision-making, whereas travel choices often involve feelings, routines, and cultural familiarity. Therefore, rather than making a conscious assessment, travelers can rely on past experiences, social influence, or convenience. Furthermore, external factors are frequently ignored by TPB’s linear “attitude–intention–behavior” paradigm. To increase TPB’s explanatory power, researchers have added variables by introducing concepts such as environmental awareness, perceived value, and innovation [

10,

30,

31].

2.1. The Relationship Between Social Media Marketing and Consumer Attitude

Social media is now an essential marketing tool in the hospitality sector because sites like Facebook and Instagram allow companies to connect with travelers, promote eco-friendly practices, and build trust through user-generated content and influencer endorsements [

32,

33]. In Turkey, where sustainability certification enforcement and consumer trust in green claims remain uneven, such organizational signals may play a particularly critical role in shaping consumer evaluations. Social media exposure affects travel choices and fosters positive attitudes and a greater awareness of sustainability [

17,

34]. However, in the data-driven and personalized marketing era, digital marketing has become even more critical for client contact. Therefore, we postulate the following:

Hypothesis 1. Social media has a significant positive influence on consumer attitude.

2.2. The Relationship Between Environmental Knowledge and Consumer Attitude

Environmental knowledge, defined as the comprehension of facts and interrelationships within ecosystems [

35], is widely recognized as essential for sustainable behavior [

36]. Prior studies show that it predicts green decision-making and purchases [

30,

37,

38] and that tourists with greater environmental knowledge are more likely to translate positive attitudes into purchases [

39]. This study focuses on everyday environmental knowledge, which is more relevant to typical consumer decisions. Within the proposed framework, environmental knowledge functions as a foundational cognitive antecedent that enhances consumers’ ability to evaluate green hotel attributes, thereby shaping attitudes that subsequently influence intention and downstream decision-making processes. Therefore, we postulate the following:

Hypothesis 2. Environmental knowledge has a significant positive influence on consumer attitudes.

2.3. The Relationship Between Organizational Green Practices Awareness and Consumer Attitude

In tourism, knowledge of green products increases tourists’ familiarity with eco-friendly practices and supports sustainable development and prior research shows that green product knowledge positively influences tourists’ attitudes toward environmentally friendly services [

40,

41], as consumers recognize their reduced resource and energy consumption [

42,

43]. In the hotel sector, sustainability-related policies and practices strongly affect consumer perceptions and choices. Green certifications such as EarthCheck enhance transparency and credibility, shaping positive attitudes and encouraging green purchase behavior. As consumers increasingly seek information beyond certifications, organizations must provide credible, verifiable communication of their environmental practices. Therefore, we postulate the following:

Hypothesis 3. Organizational green practices awareness has a significant positive influence on consumer attitudes.

2.4. The Relationship Between Self-Image in Environmental Protection and Consumer Attitude

Self-image, or self-concept, reflects how individuals perceive and evaluate themselves, and according to the self-image congruity theory [

19], consumers are more likely to prefer products that align with their sense of identity. Consequently, when individuals hold a strong pro-environmental self-image, they tend to develop more favorable attitudes toward green practices and are more likely to engage in environmentally responsible purchasing behaviors [

44,

45]. In the context of hotel guests, this means that as their personal identity becomes more closely aligned with sustainability values, their loyalty to green hotels increases, and they become more willing to support eco-friendly brands. As a result, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 4. Self-image in environmental protection has a significant positive influence on consumer attitude.

2.5. The Relationship Between Perceived Behavioral Control, Consumer Intention, and Consumer Purchase Behavior

Perceived behavioral control refers to individuals’ confidence in their ability to perform a behavior, which is shaped by factors such as available resources, convenience, and financial constraints [

8]. As a result, perceived behavioral control emerges as a strong predictor of consumer intentions and actual behaviors, particularly for high-cost decisions such as booking eco-friendly hotels [

46,

47]. Moreover, existing studies consistently demonstrate that consumers who possess greater control over resources, access, and knowledge are significantly more inclined to take sustainable actions [

48,

49]. Within the proposed framework, perceived behavioral control operates both as a motivational antecedent shaping consumer intention and as a direct enabling or constraining factor influencing purchase behavior, reflecting the practical feasibility of translating pro-environmental intentions into green hotel booking decisions. Drawing on the reviewed literature, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 5. Perceived behavioral control has a significant positive influence on consumer intention.

Hypothesis 6. Perceived behavioral control has a significant and positive influence on consumer purchase behavior.

2.6. The Relationship Between Subjective Norms and Consumer Intention

Subjective norms represent the perceived social pressure to perform or avoid a behavior, and they are shaped by the expectations of family, peers, colleagues, and other significant reference groups. Within the Theory of Planned Behavior [

8], subjective norms function as a key determinant of behavioral intention. Consistent with this, prior studies have repeatedly confirmed their significant role in shaping green consumption patterns [

13,

50,

51]. Nevertheless, the influence of subjective norms is not uniform across all populations, as their strength tends to vary depending on cultural values and contextual factors [

52,

53]. Furthermore, evidence suggests that subjective norms may also interact with perceived behavioral control, jointly shaping consumers’ intentions toward sustainable behaviors [

54]. As a result, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 7. Subjective norms have a significant positive influence on consumer intention.

2.7. The Relationship Between Consumer Attitude and Consumer Intention

According to Ajzen [

55], attitudes toward the environment play a central role in shaping consumers’ intentions, which subsequently drive actual behavior. When these attitudes are positive, they are often strengthened by effective green marketing efforts and tend to increase consumers’ willingness to pay premium prices for environmentally sustainable options [

56,

57]. Within the hospitality sector, this pattern is especially evident, as favorable attitudes toward green hotels have been shown to significantly heighten guests’ booking intentions and preference for eco-friendly accommodation [

58]. Within the proposed framework, consumer attitude represents a central evaluative mechanism that integrates the effects of social media marketing, environmental knowledge, organizational green practices, and self-image, and subsequently translates these evaluations into motivational readiness to engage in green hotel purchasing behavior. As a result, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 8. Consumer attitude has a significant and positive influence on consumer intention.

2.8. The Relationship Between Consumer Intention and Consumer Information-Seeking Behavior

According to Yang et al. [

59], information seeking is a critical consumer activity aimed at reducing uncertainty and perceived risk before forming intentions toward a specific product or service, and Cheng and Zhang [

60] study reported that to reduce risk and uncertainty, tourists use information acquired from their surroundings as well as information stored in memory to shape their consumer intention. Furthermore, tourists engage in information seeking through both internal and external sources, with the process typically beginning from prior experiences and knowledge retained in memory. Therefore, this initial, experience-based information search constitutes a foundational stage that significantly influences the formation of consumer intention. Within the TPB framework, this relationship positions consumer information-seeking behavior as a post-intentional process, whereby intention initiates active information search that subsequently influences purchase behavior, thereby linking motivational and behavioral stages of decision-making. As a result, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 9. Consumer Intention has a significant, positive influence on consumer information-seeking behavior.

2.9. The Relationship Between Consumer Information Seeking Behavior and Consumer Purchase Behavior

Consumer information-seeking behavior refers to the process through which customers intentionally obtain and evaluate information based on their past experiences and their existing knowledge of a product or service. This ongoing search for relevant information not only shapes customers’ attitudes but also influences their subsequent behaviors toward the product or service [

61]. Effective information-seeking behavior increases consumers’ understanding and awareness, thereby strengthening their willingness to purchase [

62]. Their search for information influences consumers’ purchase behavior. Information seeking enables customers to understand and evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of a product or service. High-quality information seeking strengthens consumers’ confidence in their purchase decisions and increases their assurance when choosing a product or service. As a result, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 10. Consumer information-seeking behavior has a significant positive influence on Consumer purchase behavior.

2.10. The Relationship Between Consumer Intention and Consumer Purchase Behavior

Behavioral intention reflects willingness to engage in a specific action [

26]. Research shows intention is a strong predictor of actual behavior in online and offline green purchases [

63,

64]. In tourism, intention to book eco-friendly hotels often translates into behavior, especially among consumers willing to pay more for sustainable services [

65,

66]. Within the proposed framework, consumer intention represents the central motivational mechanism linking attitudinal evaluations and perceived feasibility to actual purchase behavior, while also interacting with perceived behavioral control and post-intentional information-seeking processes. Based on the existing literature, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 11. Consumer intention has a significant positive influence on Consumer purchase behavior.

2.11. The Moderating Role of Information-Seeking Behavior in the Relationship Between Consumer Intention and Consumer Purchase Behavior

Information seeking is essential for lowering uncertainty and enhancing consumer confidence, as individuals rely on relevant cues to evaluate their choices. In the tourism context, this process becomes even more important, since guests frequently consult websites, online reviews, and sustainability certifications to inform their decisions before making a booking [

22]. While prior research shows it enhances decision-making and reduces perceived risk [

67], its role as a moderator between intention and behavior remains underexplored. It may either strengthen this link or act as a direct determinant of purchases. As a result, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 12. Consumer information-seeking behavior moderates the relationship between consumer intention and consumer purchase behavior.

2.12. The Mediating Role of Information-Seeking Behavior in the Relationship Between Consumer Intention and Consumer Purchase Behavior

Information-seeking behavior enables consumers to take essential steps in reducing the risk and uncertainty associated with a service or product [

68]. In addition, the relationship between consumer intention and actual purchasing behavior is strengthened by information-seeking behavior, such as hotel selection and booking [

69]. Although consumers might intend to purchase a product or service or to lodge in a hotel, this intention is usually supported by active consumer information-seeking behavior. However, information-seeking behavior enables consumers to reduce uncertainty and increase their confidence in their product or service decisions [

70]. Consequently, this process transforms consumer intention into consumer purchase behavior. Therefore, consumer information-seeking behavior is a crucial mediator between consumer intention and consumer purchase behavior. As a result, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 13. Consumer information-seeking behavior has a mediating role between consumer intention and consumer purchase behavior.

2.13. Conceptual Framework

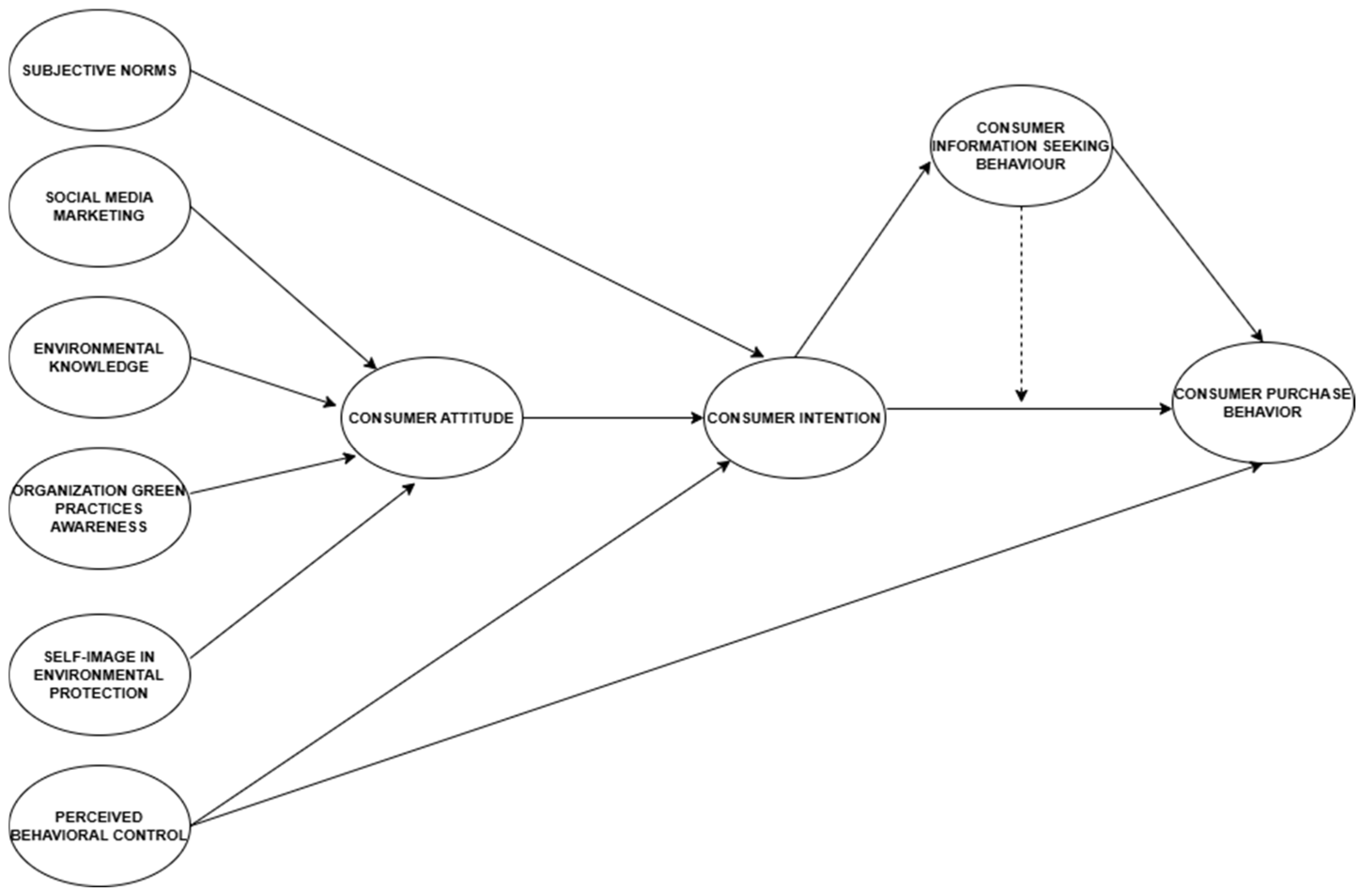

Based on the reviewed literature, this study introduced new antecedents to the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) model to examine the green hotel consumer behavior. As shown in

Figure 1, the model integrates both traditional TPB constructs and additional predictors to better capture the complexity of consumer decision-making in hospitality. In the framework, subjective norms and perceived behavioral control are hypothesized to directly influence consumer intention. At the same time, attitude is modeled as a central mediator, shaped by four key antecedents: social media marketing, environmental knowledge, awareness of organizational green practices, and self-image in environmental protection. These factors reflect the influence of digital communication, knowledge and understanding, organizational credibility, and personal identity on the formation of favorable environmental attitudes. Attitude, together with subjective norms and perceived behavioral control, is therefore expected to shape consumer intention. Moreover, both perceived behavioral control and intention are hypothesized to exert direct influences on actual purchase behavior, thereby reflecting the dual pathways emphasized within the Theory of Planned Behavior.

To address the well-documented intention–behavior gap, this model incorporates information-seeking behavior as a potential moderator and mediator of the consumer intention–behavior relationship, recognizing that consumers often rely on reviews, certifications, and disclosures to reduce uncertainty before booking green hotels. By integrating antecedents into TPB in this manner, the paradigm highlights the significant roles of digital information sources, consumer identity, and corporate sustainability practices while simultaneously positioning attitude, intention, and behavior as essential outcomes. This integrated approach provides a more thorough understanding of the elements influencing green hotel purchases in Turkey’s hospitality sector.

Taken together, the proposed hypotheses form a hierarchical decision-making structure grounded in the Theory of Planned Behavior. Social media marketing, environmental knowledge, organizational green practices awareness, and self-image in environmental protection operate as upstream antecedents, shaping consumer attitudes toward green hotels (H1–H4). Attitude, together with subjective norms and perceived behavioral control, then functions as a proximal determinant of consumer intention (H5, H7, H8), which represents the central motivational mechanism within TPB. At the behavioral stage, intention and perceived behavioral control directly influence purchase behavior (H6, H11), while information-seeking behavior is positioned as a post-intentional mechanism that facilitates or conditions the translation of intention into action (H9–H13). This hierarchical structure explicitly addresses the intention–behavior gap identified in prior TPB-based hospitality studies.

3. Materials and Methods

We employed a cross-sectional quantitative design using a structured questionnaire to test the proposed model. The instrument consisted of two sections: Section I incorporates eligibility and demographic questions. Section II consists of items measuring the constructs.

3.1. Measures

Based on the literature review, well-validated variables were chosen to measure the constructs in the research model, and the final survey questionnaire comprised 10 constructs and 51 items. The traditional Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) with four additional independent variables: social media marketing, environmental knowledge, organizational green practices awareness, and self-image in environmental protection. The social media marketing construct included thirteen items adapted from Khan and Jan [

71], and environmental knowledge was measured using five items from Mostafa [

72], while organizational green practices awareness was captured using seven items from Rizwan et al. [

73]. Self-image in environmental protection was measured with three items adapted from Lee [

74] and for the TPB core constructs, six items assessed attitudes [

75], three items measured consumer intention [

76], five items captured consumer purchase behavior [

74], three items evaluated subjective norms [

77], and three items assessed perceived behavioral control [

78]. Finally, information-seeking behavior was measured with four items adapted from Wang and Wang [

79]. The measurement instruments were selected based on their prior validation in hospitality, tourism, and sustainability-related consumer research, as well as their relevance to digitally mediated hotel decision-making. Scales related to social media marketing, organizational green practices awareness, and information-seeking behavior were specifically chosen to capture hotel-specific communication channels, online review reliance, and sustainability disclosures that are central to contemporary hotel booking processes. Environmental knowledge and self-image measures were adapted to reflect everyday consumer understanding and identity-based evaluations relevant to green hotel selection rather than abstract environmental concern. Moreover, the use of previously validated instruments enhances cross-study comparability while ensuring construct reliability in an emerging tourism market such as Turkey, where sustainability communication, certification credibility, and consumer trust vary considerably across hotels. Collectively, these instruments are well suited to capturing both the cognitive and behavioral dimensions of green hotel consumption in the Turkish hospitality context. We obtained ethics committee unanimous approval from the Cyprus International University (CIU) Scientific Research and Publication Board. A complete list of the constructs, measurement items, and sources is provided in

Appendix A. The survey was pretested with 20 respondents to check clarity and readability, and minor edits were made to reduce ambiguity before full deployment.

3.2. Sampling and Data Collection Procedure

Eligibility required participants to be 18 years or older, to have stayed in a hotel in Turkey within the last 12 months, and to be foreign tourists only. Convenience sampling was used, and data were collected over a two-month period. Participation was voluntary and anonymous, with informed consent obtained from all respondents. A total of 538 usable questionnaires were received. The respondents represented a diverse range of nationalities. The largest groups of respondents were Polish (110), German (103), Russian (97), British (96), and Dutch (91), reflecting the significant sources of visitors to Turkey’s hospitality sector. In addition, 34 respondents were Nigerian, while smaller representations included Congolese (2), Burkinabé (1), Burundian (1), Canadian (1), Rwandan (1), and Zimbabwean (1). The demographic profile of respondents suggests meaningful implications for green hotel behavior. Prior research indicates that age, education level, and income are associated with variations in environmental awareness, digital information use, and perceived behavioral control in sustainability-related decisions. The predominance of respondents aged 31–50 reflects a segment more likely to engage in frequent hotel stays and to balance environmental values with financial and convenience considerations. Higher education levels among respondents may enhance environmental knowledge and critical evaluation of green claims, while income differences can influence perceived behavioral control and willingness to pay for eco-certified hotels. Gender composition may further shape sustainability attitudes and risk perception, as earlier studies report stronger environmental concern and information engagement among female consumers. Accordingly, these demographic characteristics provide important context for interpreting the relationships among TPB constructs, information-seeking behavior, and green hotel purchase behavior.

This sample size exceeds standard SEM guidelines, including the N:q rule of thumb (≥10 cases per estimated parameter) [

80], and comfortably exceeds the typical minimum sample size of 200 recommended for complex PLS-SEM models. Respondents who had not stayed in a hotel in the past 12 months were excluded to ensure sample relevance. However, both guests with and without experience in eco-certified hotels were retained in the analysis, reflecting the study’s focus on the intention–behavior gap, and also individuals who have never stayed in a green hotel still provide meaningful insights into pro-environmental intentions and the factors that may prevent these intentions from translating into actual purchase behavior.

As shown in

Table 1, female respondents (54.3%) slightly outnumbered male respondents (45.7%), consistent with prior research indicating stronger female participation in green consumer studies [

81,

82], and the largest age group was 41–50 years (39.2%), followed by 31–40 years (35.3%), while only 12.5% were aged 21–30 whereas 13.0% were above 50 years. The age distribution, skewed toward 31–50 years, reflects the demographic most likely to engage in frequent hotel stays, consistent with prior hospitality research. Educationally, a majority held tertiary qualifications, with 36.1% holding a bachelor’s degree, 25.5% a master’s degree, and 12.4% a doctorate, and regarding income, most respondents earned between USD 1000 and USD 5000 per month (52.6%), while 18.2% reported below USD 1000 and 12.5% above USD 10,000. Collectively, this demographic profile reflects a diverse yet relatively educated consumer group, which is typical in sustainability-oriented research [

83,

84].

4. Results

Data analysis was conducted using SmartPLS version 4.1.1.6 and SPSS version 24. SPSS was used to carry out Harman’s single-factor analysis, while SmartPLS was used to implement Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) for testing the hypothesized model [

85,

86]. Following the two-step procedure recommended by Ringle et al. [

85], the measurement model was first assessed to evaluate indicator reliability, construct reliability, and validity, before proceeding to evaluate the structural model.

4.1. Common Method Bias and Endogeneity

To mitigate the risk of common method variance (CMV), both statistical and procedural methods were put into practice in accordance with the suggestions of Podsakoff et al. [

87]. First, respondents were guaranteed total anonymity and confidentiality, which helped reduce evaluation apprehension and encouraged more honest responses. Second, the survey instructions clearly emphasized that there were no “right or wrong” answers and that participation was entirely voluntary, thereby minimizing social desirability bias. Third, to limit systematic response tendencies and reduce the possibility of participants inferring relationships among constructs, the questionnaire items were presented in a randomized sequence, following the procedural guidelines outlined by [

87].

Statistically, both SPSS and SmartPLS were employed to examine possibility of common method bias (CMB). Two diagnostic tests were conducted; Harman’s single-factor test was carried out by loading all reflective items into an unrotated principal component analysis. The results indicated the presence of multiple factors, with the first factor explaining only 28.53% of the variance, well below the critical 50% threshold, thereby suggesting that CMB was not a major concern [

88]. Second, in line with Kock’s [

89] full collinearity test, we examined the variance inflation factor (VIF) values in the inner model. As presented in

Table 2, all VIF values were comfortably below the recommended cutoff of 3.33, further confirming that neither multicollinearity nor CMB posed a danger to the validity of the analysis.

Lastly, to further ensure the robustness of our findings, we implemented the Gaussian copula approach to assess potential endogeneity, following the procedures outlined by Hult et al. [

90]. Endogeneity testing is essential for obtaining unbiased structural estimates in PLS-SEM models, as prior research [

90,

91] highlights that failing to address endogeneity can distort causal inferences and recommends corrective techniques capable of detecting and accounting for hidden sources of variability. Consistent with recent methodological guidelines, the Gaussian copula approach [

92] was therefore employed to evaluate whether endogeneity was present in the model. Under this method, a copula

p-value greater than 0.05 indicates that the residual correlation between the predictor and the endogenous construct is not statistically different from zero, thereby confirming the absence of endogeneity. As shown in

Table 2, only one copula term was statistically significant: the path from Perceived Behavioral Control to Consumer Purchase Behavior (β = −0.404,

p = 0.010). This result confirms the presence of endogeneity in this relationship, suggesting that the original PLS estimate was upwardly biased due to omitted variables or simultaneity effects. All remaining copula terms were non-significant (

p > 0.05), indicating no endogeneity concerns for the other structural paths. Accordingly, only the PBC → CPB path was interpreted using the GC-adjusted estimate, while the remaining relationships were evaluated based on the standard PLS results.

4.2. Measurement Model

This section presents the evaluation of the measurement model, with particular attention to the scales’ validity and reliability. In line with the guidelines of Hair et al. (2019) [

86], we assessed construct reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity to ensure the robustness of the measurement structure. Furthermore, all standardized factor loadings exceeded the suggested threshold of 0.70, as shown in

Table 3, thereby demonstrating satisfactory indicator reliability [

93].

Composite Reliability (CR), Cronbach’s alpha (α), and rho_A were used to examine the internal consistency reliability. All CR values were greater than 0.70, Cronbach’s alpha values were below the conservative threshold of 0.95, and rho_A values were within acceptable limits, thereby confirming construct reliability. Convergent validity was established, as all Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values exceeded the minimum threshold of 0.50, indicating that each construct explained more than half of its indicators’ variance. Lastly, discriminant validity was assessed using the Fornell–Larcker criterion [

94], and the heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT) [

93,

95]. The results confirmed that discriminant validity was achieved across all constructs, as shown in

Table 3.

Furthermore, the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values ranged from 0.624 to 0.745, exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.50 [

93,

96], which indicates adequate convergent validity for all constructs. In addition, the Composite Reliability (CR) values surpassed the standard threshold of 0.70, as suggested by Henseler et al. [

95], thereby confirming the internal consistency of the measures. Discriminant validity was then assessed using both the Fornell–Larcker criterion and the Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio (HTMT). As presented in

Table 4, the square root of the AVE for each construct was greater than its correlations with other constructs, thereby satisfying the Fornell–Larcker criterion [

94]. Moreover, the HTMT values were all below the recommended cutoff of [

97], providing further evidence of discriminant validity. Taken together, the results presented in

Table 3 and

Table 4 demonstrate that the measurement model exhibits adequate reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity.

4.3. Structural Model

Hair et al. [

98] emphasized that model fit indices enable researchers to evaluate how well a proposed model aligns with empirical data. Hu and Bentler [

99] recommended two widely used criteria for assessing model fit: the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR < 0.08) and the normed fit index (NFI > 0.90). As presented in

Table 5, the SRMR values were 0.035 for the saturated model and 0.060 for the estimated model, both of which fall below the recommended threshold of 0.08, indicating good model fit. The NFI values of 0.878 (saturated) and 0.874 (estimated) are slightly below the suggested benchmark of 0.90, indicating a marginally weaker comparative fit. However, Singh [

100] noted that an acceptable NFI may range between 0.60 and 0.90, suggesting that the values obtained in this study still fall within acceptable limits.

As shown in

Table 6, the path coefficient analysis demonstrates several significant relationships among the constructs. Specifically, Consumer Attitude was found to influence Consumer Intention strongly (β = 0.304, t = 7.447,

p < 0.005), indicating that a positive attitude substantially drives the intention to engage in consumer purchase behavior. Moreover, Consumer Intention exerted a significant positive effect on Consumer Purchase Behavior (β = 0.178, t = 4.146,

p < 0.005), thereby confirming intention as a key predictor of actual consumer purchase decisions. In addition, Consumer Information-Seeking Behavior showed a significant direct effect on Consumer Purchase Behavior (β = 0.197, t = 4.687,

p < 0.005), highlighting its role in shaping consumers’ final choices. However, the moderating effect of Consumer Information-Seeking Behavior on the connection between Consumer Intention and Consumer Purchase Behavior was not statistically significant (β = 0.023, t = 0.550,

p = 0.582), suggesting that although information seeking directly influences purchase behavior, it does not amplify or diminish the effect of consumer intention. Furthermore, the mediation analysis revealed that Information-Seeking Behavior significantly mediates the relationship between Consumer Intention and Consumer Purchase Behavior (β = 0.059, t = 4.143,

p < 0.005), thereby underscoring its indirect role in transforming consumer intentions into actual behavior.

With respect to the antecedents of Consumer Attitude, all hypothesized predictors were significant, these included Social Media Marketing (β = 0.143, t = 3.293, p < 0.005), Environmental Knowledge (β = 0.125, t = 3.037, p < 0.005), Organization Green Practices Awareness (β = 0.253, t = 5.713, p < 0.005), Self-Image in Environmental Protection (β = 0.158, t = 3.928, p < 0.005). These findings highlight that both personal and organizational factors, as well as external marketing efforts, significantly shape consumers’ attitudes. Additionally, Subjective Norms (β = 0.138, t = 3.431, p < 0.005), and Perceived Behavioral Control (β = 0.187, t = 4.497, p < 0.005) were a significant determinant of Consumer Intention, consistent with the Theory of Planned Behavior.

Hair et al. [

98] emphasized the importance of calculating the R

2 level, as it measures the variance explained by the exogenous constructs in the model’s endogenous constructs. The R

2 value ranges between 0 and 1, with higher values indicating stronger explanatory power and, in this study, the R

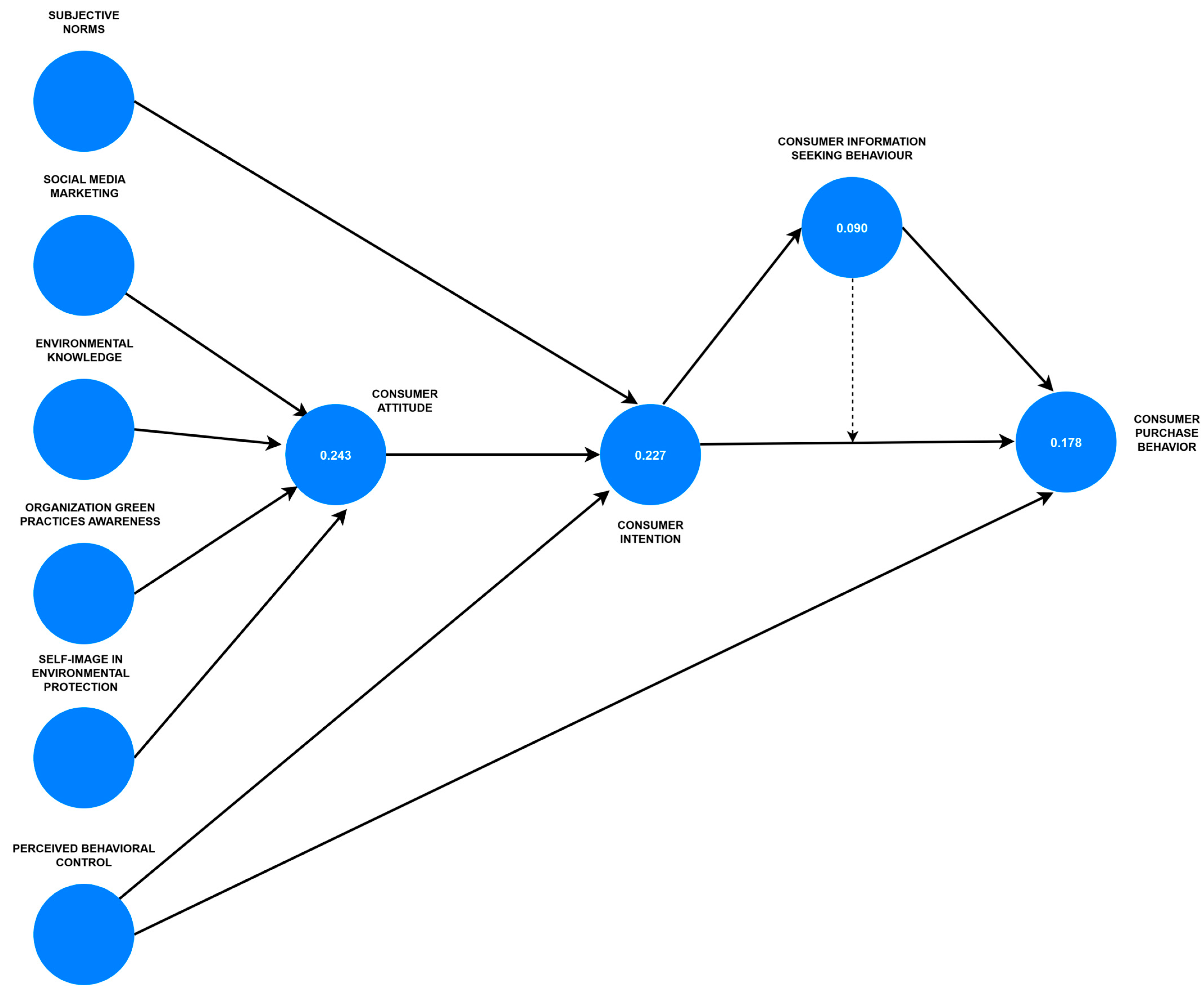

2 value for Consumer Attitude was 0.243, indicating that 24.3% of the variance in consumer attitude was explained by its predictors (Environmental Knowledge, Organization Green Practices Awareness, Self-Image in Environmental Protection, and Social Media Marketing). The R

2 value for Consumer Intention was 0.227, showing that 22.7% of its variance was explained by Subjective Norms, Consumer Attitude, and Perceived Behavioral Control. Similarly, the R

2 value for Consumer Purchase Behavior was 0.178, suggesting that 17.8% of the variance was explained by Consumer Intention, Consumer Information Seeking Behavior, and Perceived Behavioral Control.

Following Cohen’s [

101] guidelines, where R

2 values of 0.26, 0.13, and 0.02 are considered substantial, moderate, and weak, respectively, the R

2 values obtained in this study (Consumer Attitude = 0.243; Consumer Intention = 0.227; Consumer Purchase Behavior = 0.178) demonstrate moderate explanatory power of the model across the targeted endogenous constructs (See

Figure 2). Taken together, these findings provide empirical support for the hypothesized model, highlighting the critical role of consumer attitude and intention in predicting green consumer behavior, while also emphasizing the importance of both individual and organizational factors in shaping pro-environmental decision-making.

5. Discussion

Green hotel consumption represents a complex form of pro-environmental decision-making in which consumers balance ethical values, perceived credibility, social influence, and practical constraints. Unlike routine green behaviors, hotel selection involves higher financial commitment and experiential risk, making trust and verification particularly salient. The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) provides a useful foundation for understanding such decisions by emphasizing the roles of attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control [

8]. However, hospitality decisions often extend beyond purely rational evaluation, requiring additional explanatory mechanisms related to identity, organizational credibility, and information processing. In this regard, the present study contributes to the literature by extending TPB to account for these contextual and behavioral complexities within the green hotel domain.

The findings indicate that consumer attitudes toward green hotels are shaped primarily by awareness of organizational green practices, followed by environmental knowledge, social media marketing, and self-image in environmental protection. This pattern suggests that in hospitality contexts, where services are intangible and environmental claims may be difficult to verify consumers place greater weight on visible and credible organizational actions than on abstract environmental values alone. Prior research has similarly shown that certifications, transparent sustainability initiatives, and tangible green practices strengthen consumer evaluations and trust in hotels [

102,

103]. In emerging tourism markets such as Turkey, where concerns about greenwashing and inconsistent enforcement of sustainability standards persist, organizational credibility appears to play a particularly decisive role in shaping favorable attitudes.

Environmental knowledge and social media marketing also contributed positively to attitude formation, consistent with studies demonstrating that sustainability awareness and digital engagement influence green evaluations and preferences [

22,

67,

72]. However, their comparatively weaker influence suggests that awareness and exposure alone may be insufficient to generate strong attitudes unless they are supported by verifiable organizational practices. This contrasts with findings from some developed-market studies, where environmental knowledge plays a more dominant role in shaping green attitudes [

9,

39]. The present findings therefore highlight a contextual distinction, indicating that consumers in tourism-dependent emerging economies may adopt a more cautious, evidence-oriented approach when evaluating green hotels. Self-image in environmental protection further shaped attitudes, supporting self-congruity theory, which posits that individuals prefer behaviors aligned with their self-concept [

19,

104]. Nevertheless, its secondary role suggests that identity-based motivation complements rather than substitutes for organizational trust in high-risk consumption contexts.

With respect to intention formation, consumer attitude emerged as the most influential determinant, reinforcing TPB’s central proposition that favorable evaluations drive behavioral intentions [

8]. This finding aligns with prior hospitality research showing that positive environmental attitudes significantly enhance intentions to patronize green hotels [

39,

57,

105]. Subjective norms also influenced intention, reflecting the role of social expectations and peer influence in sustainability-related decisions [

106]. However, their weaker effect suggests that hotel booking decisions often made privately and through digital platforms may be less socially observable than other pro-environmental behaviors, thereby reducing the salience of normative pressure. Perceived behavioral control further contributed to intention and behavior, consistent with prior evidence that consumers are more likely to engage in sustainable actions when they feel capable of doing so [

107,

108]. At the same time, the moderate strength of this relationship indicates that structural constraints, such as price sensitivity, hotel availability, and travel convenience, continue to shape the feasibility of green hotel choices.

A particularly important contribution of this study lies in clarifying the role of information-seeking behavior within the extended TPB framework. While prior research has emphasized the importance of information search in reducing uncertainty and facilitating purchase decisions [

109,

110], the present findings suggest that information-seeking behavior functions primarily as a post-intentional process. Consumers appear to engage in information search after forming an initial intention, using online reviews, sustainability disclosures, and third-party endorsements to validate their choices and reduce perceived risk [

111,

112]. The absence of a significant moderating effect indicates that information seeking does not necessarily strengthen the intention–behavior relationship; rather, it operates as an independent driver that directly influences purchase behavior while partially mediating the transition from intention to action. This interpretation differs from studies suggesting that information seeking enhances intention–behavior consistency by reinforcing confidence [

17] and instead highlights its role as a verification mechanism in high-risk service decisions.

Consumer purchase behavior ultimately reflected the combined influence of intention, perceived behavioral control, and information-seeking behavior, underscoring the multifaceted nature of green hotel decision-making. This pattern is consistent with TPB’s assertion that intention alone is insufficient to predict behavior and that situational and contextual factors play a critical role [

8]. Prior studies similarly show that pro-environmental intentions do not always translate into actual behavior, particularly in hospitality contexts where economic and informational constraints intervene [

113,

114]. The mediating role of information seeking further illustrates how consumers navigate uncertainty by seeking reassurance before committing to a green hotel booking.

The findings of this study support an extended TPB framework that better captures the realities of sustainable consumption in hospitality settings. By highlighting the importance of organizational credibility, feasibility conditions, and post-intentional information verification, this study advances theoretical understanding of the intention–behavior gap in green hotel consumption. From a practical perspective, the results suggest that hotel managers should prioritize transparent and verifiable sustainability communication rather than relying solely on awareness campaigns or symbolic green messaging. Facilitating access to credible information through digital platforms, certifications, and third-party reviews is likely to play a critical role in converting favorable attitudes and intentions into actual booking behavior, particularly in emerging tourism markets.

Managerial Implications

The findings of this research provide several actionable insights for hospitality managers and policymakers, particularly regarding how to strengthen consumers’ pro-environmental engagement. Given the strong influence of subjective norms and attitudes, hotels should design marketing campaigns that simultaneously highlight social approval and peer endorsement of eco-friendly behaviors. By showcasing positive guest testimonials, emphasizing community support for sustainable practices, and promoting collective achievements, such as “X tons of waste recycled by our guests”, hotels can more effectively reinforce social validation and encourage environmentally responsible choices. Moreover, this strategy is consistent with the evidence from Abdou et al. [

115] and Zhang et al. [

116], which demonstrate that peer influence plays a significant role in shaping pro-environmental decisions within the tourism sector.

Second, the significant role of social media marketing underscores the growing importance of digital engagement, particularly as consumers increasingly rely on online platforms to inform their sustainability-related decisions. Hotels should therefore actively leverage platforms such as Instagram, Facebook, and TikTok to communicate their sustainability initiatives, share behind-the-scenes content, and co-create narratives with environmentally conscious influencers who can enhance message credibility. This approach is supported by the work of Ummar et al. [

117], which demonstrates that persuasive, informative, and credible green social media communication plays a critical role in shaping sustainable attitudes and behavioral intentions.

Third, strengthening environmental knowledge through targeted guest education initiatives can further reinforce pro-environmental attitudes and encourage sustainable behavior. Practical measures, such as providing in-room sustainability guides, offering eco-tours, integrating interactive mobile applications, and introducing gamified recycling incentives, can make green practices more engaging and accessible. At the same time, organizational green practices, including the display of eco-certifications, the implementation of visible recycling programs, the adoption of renewable energy solutions, and the transparent reporting of sustainability performance, serve as trust-building signals that enhance perceived credibility. This is consistent with findings from Godovykh et al. [

118], whose work on sustainable labeling in hospitality shows that visible certifications directly improve guest trust and increase willingness to pay for green services.

Fourth, the results demonstrate that self-image and perceived behavioral control (PBC) serve as critical determinants of both intention and behavior, thereby highlighting the need for hotels to design strategies that enhance guests’ sense of identity and agency. Hotels can capitalize on this by framing sustainable choices as expressions of personal identity, such as through campaigns that emphasize messages like “Stay green, stay proud”, while simultaneously increasing convenience through default green booking options, widely accessible recycling bins, or discounted rates for low-carbon travel. By reducing practical barriers and empowering guests to make environmentally responsible choices, these measures help translate pro-environmental intentions into actual behaviors.

Finally, the finding that information-seeking behavior directly influences purchase decisions underscores the importance of ensuring that sustainability-related information is accurate, detailed, and easily accessible. Creating dedicated sustainability sections on hotel websites, offering transparent environmental disclosures, and obtaining third-party verified certifications can substantially reduce uncertainty and strengthen consumer confidence. This aligns with the findings of Papallou et al. [

119], whose research on sustainable tourism trends demonstrates that transparency and credibility remain decisive in converting positive consumer attitudes into actual bookings. By implementing these strategies collectively, hospitality firms can enhance consumer engagement, strengthen brand credibility, and secure a competitive advantage in an increasingly sustainability-driven market.

6. Conclusions

This research provides deeper insight into the drivers of green hotel consumer behavior by extending the TPB through the integration of environmental knowledge, self-image in environmental protection, awareness of organizational green practices, social media marketing, and consumer information-seeking behavior. By modeling these constructs as upstream antecedents shaping consumer attitudes, the study demonstrates how personal values, digital influence, and organizational credibility jointly affect sustainable consumption decisions in the hospitality sector.

From a theoretical perspective, the study makes a primary theoretical contribution by advancing TPB beyond its traditional structure. First, it refines attitude formation by incorporating digital, organizational, and identity-based mechanisms, thereby addressing limitations in prior TPB-based hospitality studies that treated these factors in isolation. Second, the findings explicitly clarify the intention–behavior gap by demonstrating that information-seeking behavior operates as a post-intentional mediating mechanism, rather than as a moderator, providing a clearer theoretical explanation of how pro-environmental intentions are translated into actual purchase behavior. Third, the dual influence of perceived behavioral control on both intention and behavior highlights the importance of feasibility and resource constraints in sustainable hotel decision-making.

In addition, the study offers contextual contribution by empirically validating this extended TPB framework in Turkey, an emerging tourism market that remains underrepresented in sustainability research despite its economic reliance on tourism. While the contribution is primarily theoretical, the contextual evidence strengthens the external validity of TPB extensions in service-oriented and digitally mediated consumption settings. From a practical standpoint, the results underscore the importance for hospitality managers of transparent green practices, credible sustainability communication, and effective digital engagement strategies. By aligning sustainability initiatives with consumer identities and information needs, hotels can strengthen trust, reduce uncertainty, and encourage the translation of pro-environmental attitudes into actual booking behavior.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Although this research provides valuable insights into consumer behavior in the hospitality industry, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, although the respondents represented diverse cultural backgrounds, the data were collected exclusively within the Turkish hospitality context and relied on convenience sampling of foreign tourists who had stayed in hotels in Turkey within the past 12 months. While this sampling strategy ensured contextual relevance, it may limit the generalizability of the findings to other settings, such as domestic tourists, repeat visitors, or consumers with long-term engagement in green hotel consumption. Future research should therefore test the proposed model across broader geographical contexts and tourist segments using probability-based or comparative sampling designs.

Second, the age distribution of the sample was uneven, with a higher concentration of respondents in the 31–50 age group. Although this cohort is highly relevant to hotel consumption, attitudes toward sustainability, digital information use, and risk perception may vary across age groups. As a result, the findings may not fully capture the perspectives of younger or older travelers. Future studies could adopt stratified sampling techniques or multi-group analyses to examine whether age moderates the relationships among TPB constructs, information-seeking behavior, and green hotel purchase decisions.

Third, tourist experience was not explicitly controlled for in the analytical model. Respondents likely differed in terms of travel frequency, familiarity with eco-certified hotels, and prior exposure to sustainable tourism practices. Such experiential differences may influence perceived behavioral control, information-seeking behavior, and the extent to which pro-environmental intentions translate into actual purchase behavior. Future research is encouraged to incorporate tourist experience as a control or moderating variable, or to distinguish between first-time visitors and experienced green hotel consumers.

Fourth, the study relied on self-reported, cross-sectional survey data, which may be subject to recall bias and social desirability effects, particularly given the sensitivity of sustainability-related topics. Although procedural and statistical remedies were applied to mitigate common method bias, future research could strengthen causal inference by employing longitudinal designs or integrating objective behavioral indicators, such as booking records or platform-based data.

Fifth, although this study extended the TPB by introducing antecedents such as social media marketing, organizational green practices awareness, and self-image in environmental protection, several potentially influential constructs, including environmental concern, consumer trust, price sensitivity, and perceptions of greenwashing were not incorporated. Including these variables in future research could provide a more comprehensive understanding of green hotel decision-making processes.

Finally, while Consumer Information-Seeking Behavior exerted a significant direct effect on purchase behavior and partially mediated the intention–behavior relationship, its moderating effect was not supported. Future studies should re-examine this relationship using longitudinal or stage-based decision-making frameworks to assess whether the role of information seeking varies across pre-purchase, purchase, and post-purchase phases.

Despite these limitations, the study offers meaningful implications for both practice and policy. For hospitality managers, the findings underscore the importance of transparent sustainability communication, credible eco-certifications, and digital information accessibility to translate pro-environmental attitudes into actual bookings. For policymakers, the results highlight the need to support standardized sustainability reporting, incentivize certification schemes, and promote public awareness initiatives to accelerate the transition toward sustainable tourism. By addressing these limitations, future research can refine the theoretical model, strengthen its predictive validity, and provide more generalizable insights into sustainable consumer behavior in the global hospitality and tourism sectors.