1. Introduction

Healthcare systems are increasingly recognized as complex contributors to ecological decline, not only through greenhouse gas emissions but also via intensive water consumption, chemical discharge, and the generation of hazardous and pharmaceutical waste [

1,

2]. Hospitals, in particular, consume vast amounts of energy, generate large volumes of waste, and depend on resource-intensive supply chains [

3]. These impacts have direct repercussions on human health, as climate change is linked to rising rates of stroke, myocardial infarction, respiratory diseases, and other conditions strongly associated with morbidity and mortality [

4,

5].

Within hospitals, intensive care units (ICUs) are disproportionately resource-intensive due to their reliance on advanced technologies, continuous monitoring, and single-use equipment. Material flow analyses show that non-sterile gloves, syringes, and disposable gowns are among the largest contributors to ICU waste per patient-day [

6], while studies indicate that reusable alternatives can reduce environmental footprints if managed appropriately [

7]. Reviews consistently highlight critical care as a major “hotspot” for unsustainable practices, underscoring the urgency of redesigning ICUs along greener models of care [

8,

9].

Sustainability in ICUs is not determined only by infrastructure or technology, but also by healthcare professionals’ daily choices [

10]. Nurses, as the largest workforce and primary providers of bedside care, directly influence resource use and waste generation [

11,

12]. Their contribution can be understood through the lens of knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors (KAB). Knowledge refers to awareness of environmental issues and sustainable practices; educational interventions have shown that improved knowledge enhances performance in waste management and resource use [

13,

14,

15]. Attitudes reflect the values and motivations underlying practice; nurses with strong pro-environmental attitudes tend to view sustainability as an ethical duty and are more likely to adopt environmentally responsible behaviors [

16,

17]. Behaviors represent the concrete translation of these orientations, including waste segregation, rational use of disposables, and energy-efficient patient care. Evidence confirms that such practices can reduce ICUs’ ecological footprint without compromising safety or quality [

18,

19].

Although each dimension of KAB has been explored in nursing research, existing evidence is fragmented. Most studies rely on cross-sectional designs, often outside the ICU context, and focus on isolated aspects, such as environmental awareness or waste management [

13,

14,

20]. No validated instrument currently exists to comprehensively assess ICU nurses’ KAB regarding sustainability. Available tools are either generic or limited to specific domains, making it difficult to generate robust, comparable data or to design targeted interventions. Furthermore, longitudinal research is virtually absent, leaving unanswered whether improvements in knowledge and attitudes are sustained over time, whether they lead to consistent behavioral change, and how such changes affect clinical, organizational, and environmental outcomes.

To address these gaps, this research protocol aims to develop and validate the Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behaviors Questionnaire on Environmental Sustainability in Intensive Care Units (KABQES-ICU). By integrating KAB dimensions into a single framework and applying it in a longitudinal design, this research will provide the first comprehensive evidence on how sustainable nursing practice evolves in ICUs and how it can be leveraged to improve outcomes at multiple levels.

2. Conceptual Framework

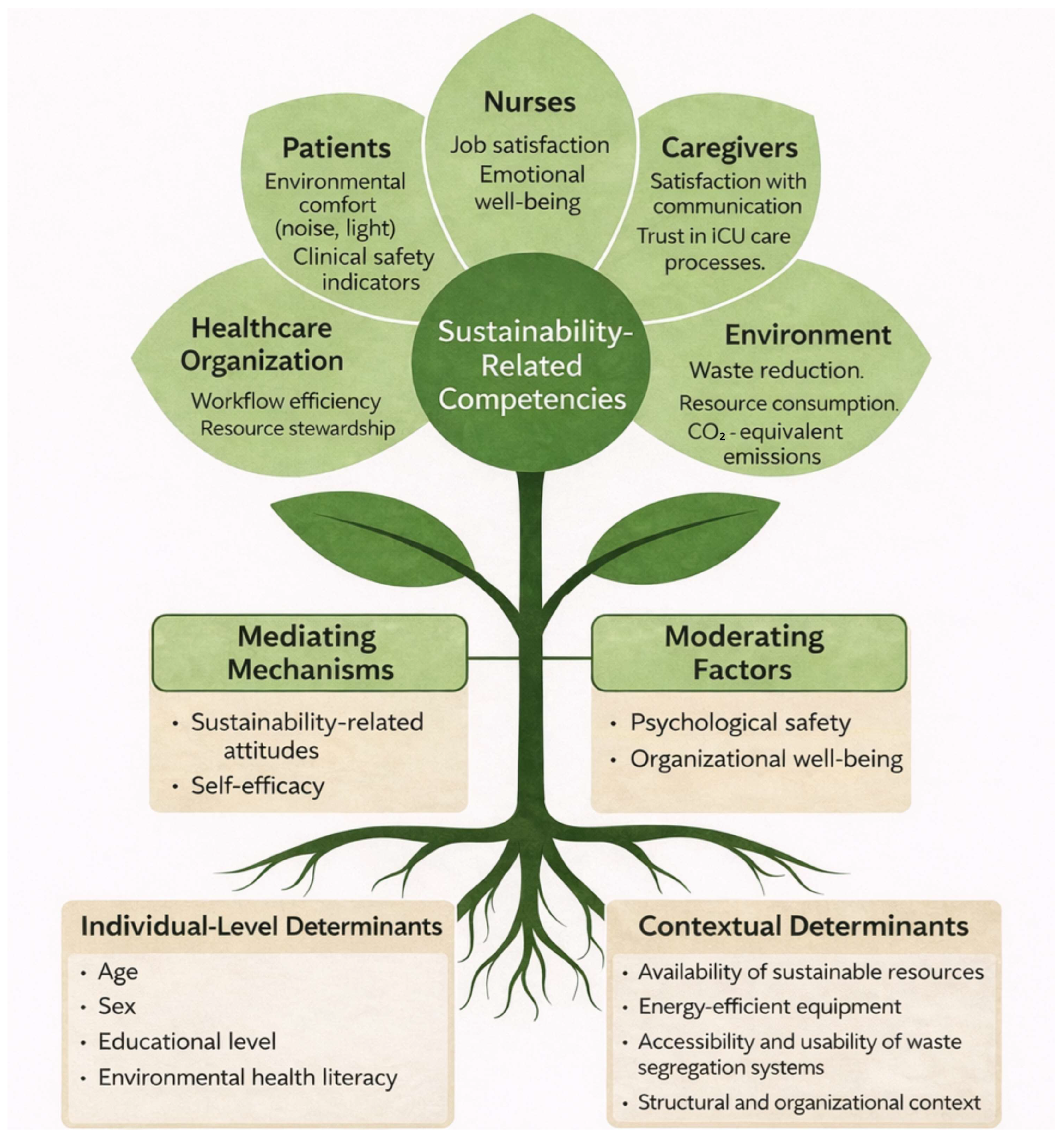

In this research protocol, the conceptual framework (

Figure 1) outlines how sustainability-related knowledge, attitudes and behaviors among ICU nurses give rise to measurable outcomes across five interrelated domains: nurses, patients, caregivers, healthcare organizations and the environment. The model is grounded on three complementary theoretical foundations. First, the concept analysis by Anåker and Elf [

21] frames sustainability as an ethical and ecological component of high-quality nursing care, requiring awareness of resource use and institutional support. Second, the grounded theory developed by Baid et al. [

22] conceptualizes sustainable practice in intensive care as an adaptive process shaped by uncertainty, multitasking, satisficing and bounded rationality typical of high-acuity environments. Third, broader healthcare sustainability literature shows that environmentally responsible practice emerges from an interaction among knowledge, values, organizational conditions and structural constraints [

23,

24,

25]. These foundations converge through the KAB model, which explains how knowledge shapes attitudes and how attitudes translate into observable behaviors [

26,

27].

Building on this structure, the framework is operationalized by distinguishing between predictive factors that shape sustainability-related knowledge and attitudes, mediating mechanisms that regulate the translation of these determinants into action and outcomes that capture the effects of sustainable behaviors across multiple system levels. This analytical distinction allows the model to move from conceptual relationships to empirically testable pathways, guiding both measurement and hypothesis development.

2.1. Predictive Factors

2.1.1. Individual-Level Determinants

Individual characteristics influence the formation and depth of sustainability-related knowledge. Research consistently shows that age, sex and educational level are associated with environmental concern and pro-environmental behavior, with younger individuals, women and more educated professionals displaying stronger ecological engagement [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. Environmental health literacy further reinforces the cognitive capacity required to understand the environmental implications of clinical activity and the relationship between health and environmental exposures. Together, these individual determinants shape the knowledge base from which sustainability-related attitudes and behaviors emerge.

2.1.2. Contextual Determinants

Contextual determinants define the environment in which knowledge is applied. Structural determinants include the availability, accessibility and usability of sustainable resources within the ICU, such as recycling stations, waste segregation systems and energy-efficient equipment. When such resources are integrated into the physical environment, sustainable actions require less cognitive effort and occur more consistently [

24,

25].

Relational determinants, particularly leadership style, influence motivation, shared norms and environmental responsibility within teams. Transformational and environmentally oriented leadership styles are linked to stronger engagement and greater adoption of sustainable behaviors [

33]. Organizational determinants influence the emotional and cognitive climate in which nurses operate. A high workload reduces cognitive bandwidth and limits capacity for sustainability-oriented decision-making [

34]. Organizational well-being and psychological safety promote trust, openness, shared learning and proactive engagement in change-oriented behaviors [

35,

36]. Exposure to sustainability initiatives and training reinforces the perception that sustainable practice is legitimate, expected and relevant to clinical care [

10]. Collectively, contextual determinants shape whether sustainability-related knowledge can be translated into meaningful practice.

2.2. Mediating Mechanisms

Mediating mechanisms describe how predictive factors influence the adoption of sustainable behaviors. Attitudes toward sustainability reflect nurses’ evaluative and motivational orientation, including beliefs about the compatibility of sustainability with patient safety and care quality. Positive attitudes increase the likelihood that knowledge produces behavioral intention.

Self-efficacy reflects the perceived capability to perform sustainable actions despite contextual barriers and has a central role in the transition from intention to behavior [

37].

Organizational well-being and psychological safety do not function as mediating mechanisms but rather as contextual moderators that influence the strength and stability of the relationship between sustainability-related attitudes, self-efficacy, and sustainable nursing behaviors over time [

35,

36]. These factors form the pathway through which individual and contextual determinants converge to produce sustainability-related actions.

2.3. Outcomes

2.3.1. Nurses

For nurses, sustainability-related behaviors influence workflow coherence, perceived control over clinical activities and psychological well-being. When waste segregation, prudent material use, and intentional equipment management are embedded into daily routines, clinical work becomes more structured and predictable. Reducing unnecessary fragmentation and operational inefficiencies alleviates cognitive and emotional strain, particularly in high-acuity environments such as the ICU. Evidence shows that pro-environmental actions can reinforce perceived professional efficacy, organizational citizenship and job satisfaction [

28,

33]. Sustainable practices may therefore reduce emotional workload by minimizing preventable stressors associated with disorganization and resource mismanagement [

34,

38].

2.3.2. Patients

For patients, sustainability-oriented behaviors can enhance safety, comfort and environmental quality. Reducing unnecessary interventions and managing resources intentionally may decrease exposure to noise, light disturbances and environmental stressors, contributing to more therapeutic ICU conditions [

34,

39]. These improvements can influence patient satisfaction and contribute to safer, more person-centered care.

2.3.3. Caregivers

For caregivers, sustainability-oriented processes support clarity, coherence and trust in the care pathway. Transparent workflows and intentional resource use can enhance communication quality and reduce perceived chaos, strengthening family satisfaction with the ICU experience [

40].

2.3.4. Healthcare Organizations

At the organizational level, sustainable behaviors influence workflow efficiency, resource stewardship and environmental performance. Reducing waste generation, improving segregation accuracy and optimizing processes contribute to organizational resilience and align with quality improvement frameworks that integrate environmental value [

10]. These outcomes highlight that sustainability is not solely an ethical imperative but also a dimension of organizational performance.

2.3.5. Environment

At the environmental level, sustainability-related behaviors reduce waste generation, improve segregation accuracy and lower energy and water consumption. These actions lessen the ecological footprint associated with intensive care practice and align healthcare operations with global sustainability and public health priorities [

41]. Environmental outcomes thus capture the direct ecological implications of clinical behavior.

Taken together, the framework describes an interconnected pathway in which individual characteristics shape sustainability-related knowledge, contextual determinants condition its application, mediating mechanisms convert determinants into behavioral engagement, and contextual moderators influence the extent to which these mechanisms operate effectively in practice. Sustainable behaviors, in turn, generate outcomes across professional, clinical, organizational and environmental domains. This conceptual structure guides the empirical investigation by identifying which determinants, mediators and outcomes require systematic evaluation throughout the research program.

3. Objectives and Hypotheses

The overarching aim of this research program is to develop and validate a theory-grounded instrument for assessing sustainability-related knowledge, attitudes and behaviors among ICU nurses (KABQES-ICU) and to evaluate, through a longitudinal intervention study, how these constructs evolve over time and contribute to multi-level outcomes following a structured educational program.

3.1. Objectives

The specific objectives are to

Develop, pretest, and psychometrically validate the KABQES-ICU among ICU nurses;

Assess longitudinal changes in sustainability-related knowledge, attitudes and behaviors among ICU nurses after a structured training program;

Evaluate how organizational and contextual conditions shape the effectiveness of a sustainability-focused educational intervention in promoting sustainable nursing behaviors in intensive care settings;

Examine the hypothesized pathways through which sustainability-related knowledge and attitudes interact with organizational conditions to produce sustained behavioral change over time;

Determine how such behavioral changes affect outcomes across nurses, patients, caregivers, organizations and the environment.

3.2. Hypotheses

H1. The educational intervention will produce significant improvements in ICU nurses’ sustainability-related knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors.

H2. Baseline organizational and contextual conditions (leadership, organizational well-being, psychological safety and workload) will moderate the effectiveness of the educational intervention on the development of sustainable nursing behaviors.

H3. Longitudinal improvements in sustainability-related knowledge and attitudes will indirectly influence sustainable nursing behaviors through increases in sustainability-related self-efficacy.

H4. Organizational well-being and psychological safety will act as contextual moderators of the relationship between sustainability-related attitudes, self-efficacy and sustainable nursing behaviors over time.

H5. Increases in sustainable nursing behaviors will lead to measurable improvements in multi-target outcomes, including professional outcomes for nurses, experiential and clinical outcomes for patients, satisfaction for caregivers, workflow and resource-based outcomes for the organization, and environmental performance indicators.

H6. Changes in multi-target outcomes will be partially explained by longitudinal changes in sustainable nursing behaviors, consistent with the hypothesized pathways proposed in the conceptual framework.

4. Design and Methods

This study employs a multi-phase research design combining psychometric instrument development with a longitudinal intervention study to examine how sustainability-related constructs evolve among ICU nurses.

4.1. Phase 1: Instrument Development and Validation (KABQES-ICU)

The first operational phase focuses on the development and validation of the KABQES-ICU. The instrument is designed to operationalize the constructs articulated in the conceptual framework by translating them into measurable dimensions while explicitly incorporating the experiential themes identified in the qualitative content analysis by Bartoli et al. [

42]. That study explored ICU nurses’ perceptions and lived experiences of environmental sustainability and highlighted fragmented and inconsistent knowledge, perceived tensions between sustainability initiatives and infection-prevention requirements, structural and logistical constraints that hinder sustainable behaviors, and competing cognitive demands associated with workload and clinical urgency. It also underscored the pivotal role of leadership, ethical motivation, and organizational culture in shaping nurses’ willingness and capacity to act sustainably. Integrating these qualitative insights ensures that the questionnaire is grounded in real-world clinical experience, accurately capturing the barriers, enablers, cognitive processes, and contextual dynamics that characterize sustainability-related practice in intensive care, thereby strengthening content validity and theoretical coherence.

Content validity will be assessed by an expert panel evaluating clarity, relevance and representativeness. A pilot study will test linguistic clarity, interpretability and distributional properties. The refined tool will undergo full psychometric evaluation, exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses, internal consistency, test–retest reliability, and construct and structural validation in order to ensure theoretical and empirical coherence with the KAB model [

26,

27].

The validated instrument will then serve as the primary measurement tool in the longitudinal phase.

4.2. Phase 2: Longitudinal Intervention Study

Phase 2 will consist of a quasi-experimental controlled longitudinal pre–post study designed to evaluate the effects of a structured sustainability training intervention on ICU nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and sustainable behaviors by comparing nurses working in hospitals implementing the intervention with a comparison group of nurses from different hospitals not receiving the intervention during the study period, and to assess whether these changes are associated with measurable improvements across the multi-target outcomes described in the conceptual framework. This phase operationalizes the causal pathways hypothesized in the KAB model by examining how individual, psychological and organizational determinants evolve after the intervention and how these changes contribute to the development of sustainable nursing behaviors and their downstream effects on nurses, patients, caregivers, the healthcare organization and the environment.

Although the inclusion of a comparison group strengthens internal validity, the quasi-experimental nature of the design remains susceptible to potential confounding factors, such as baseline differences between hospitals and concurrent organizational or policy changes occurring during the study period. Random assignment at the individual or unit level will not be feasible due to organizational and operational constraints across participating hospitals.

4.3. Sampling and Setting

The study will take place in adult ICUs within public tertiary-level hospitals in Italy that provide continuous high-acuity care, including mechanical ventilation, invasive monitoring and advanced life-support technologies. Participating units will need to demonstrate organizational stability and consistent staffing, ensuring feasibility for repeated assessments.

Sampling will follow a multi-stage strategy that will reflect both the psychometric and longitudinal components of the study. During Phase 1, ICU nurses will be recruited across multiple ICUs to obtain the sample sizes required for exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses. Assuming that the final version of the KABQES-ICU will include approximately 30 items, and following established recommendations of 5–10 participants per item for factor analysis, between 150 and 300 nurses will be required for exploratory factor analysis, while at least 200 nurses will be needed for confirmatory factor analysis to ensure stable parameter estimation and adequate evaluation of model fit [

43,

44,

45]. Recruitment will therefore continue until approximately 350–400 ICU nurses have completed the instrument, allowing for robust psychometric testing, the possibility of using partially independent subsamples for exploratory factor analyses (EFA) and confirmatory factor analyses (CFA), and a sufficient margin for incomplete responses.

For Phase 2, a longitudinal subsample of nurses will be recruited from the same ICUs involved in Phase 1. The required sample size for the longitudinal analyses will be determined through an a priori power analysis conducted with G*Power 3.1 [

46], using a repeated-measures within-subjects design with 4 time points, an expected moderate effect size (f = 0.25), an alpha level of 0.05 and a desired power of 0.80. Under these conditions, the power analysis will indicate that a minimum of 128 nurses will be needed to detect significant changes over time. To account for an anticipated attrition rate of approximately 20–25% over the 6-month follow-up period, the study will aim to enroll at least 160 ICU nurses in the longitudinal phase. Eligible nurses will have at least 6 months of ICU experience and a stable employment contract that will allow them to participate in all planned assessments (baseline, immediately post-intervention, 3 months and 6 months). Nurses on agency contracts or extended leave will be excluded to ensure consistent participation.

Patient and caregiver sampling will occur through consecutive admissions during the Phase 2 data collection period. Adult patients (≥18 years) who will have remained in the ICU for at least 48 h and who will be clinically and cognitively able to respond to patient-reported measures at the time of data collection will be invited to participate. For each participating patient, 1 informal caregiver who will have been directly involved in supporting or visiting the patient during the ICU stay will be enrolled.

4.4. Description of the Intervention

The intervention consists of a structured sustainability training program for intensive care unit (ICU) nurses, designed to promote environmentally sustainable knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors in critical care settings. The intervention is grounded in the knowledge–attitudes–behaviors (KAB) framework and integrates individual, organizational, and contextual determinants of behavior change, in line with the conceptual framework underpinning the study.

Training materials include standardized slide decks, written educational resources, and case-based learning materials specifically developed to reflect ICU workflows and environmental sustainability challenges in critical care practice. The intervention combines didactic components with interactive elements, including group discussions and applied exercises aimed at translating sustainability principles into routine nursing activities.

The training is delivered by facilitators with expertise in critical care nursing and environmental sustainability in healthcare. Sessions are conducted in person within the ICUs of participating hospitals to ensure contextual relevance and facilitate engagement. The intervention is implemented according to a predefined structure, with the number, duration, and scheduling of sessions standardized across intervention sites to ensure consistency.

While the core content of the intervention is standardized, examples and discussions are tailored to local ICU practices and organizational contexts to enhance applicability and acceptability. Any adaptations made during implementation are documented to support transparency and reproducibility.

Intervention fidelity is monitored through documentation of session delivery, facilitator adherence to the planned content, and participant attendance. These procedures are intended to ensure that the intervention is delivered as intended while allowing for context-sensitive implementation within complex ICU environments.

4.5. Data Collection

Data collection will take place at four time points: baseline (T0), immediately after the intervention (T1), and at three-month (T2) and six-month (T3) follow-ups. Baseline assessment (T0), conducted prior to the training intervention, will serve as the reference point for evaluating both the immediate (T1) and long-term (T2–T3) effects of the sustainability training program. At T0, or in any case prior to the administration of all other instruments, sociodemographic characteristics will be collected as part of the individual-level determinants of the framework. These variables will include age, sex, and educational level. At each assessment, participants will complete the validated KABQES-ICU along with a set of established measurement instruments aligned with the constructs of the conceptual framework:

Environmental health literacy will be measured using the Environmental Health Engagement Profile [

47];

Leadership perceptions will be assessed with the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire [

48];

Workload will be assessed using the NASA Task Load Index (NASA-TLX) [

49];

Emotional workload will be measured with the Emotional Labour Scale [

38];

Organizational well-being will be measured using the validated instrument by Avallone (Copenhagen, Denmark) [

35];

Psychological safety will be evaluated through Edmondson [

36];

Job satisfaction will be evaluated using the McCloskey/Mueller Satisfaction Scale (MMSS) [

50];

Sustainability-related self-efficacy will be measured using adapted items derived from validated environmental self-efficacy tools developed by Bamberg and Möser [

37] and Tabernero and Hernández [

51];

Sustainable nursing behaviors will be assessed through both the KABQES-ICU behavioral items and structured observational audits developed in accordance with WHO waste segregation guidelines [

52].

Patient-related outcomes will be collected during this phase. Environmental comfort will be measured using the Intensive Care Unit Environmental Stressors Scale [

53,

54,

55], while objective indicators of light and noise exposure will be obtained using monitoring procedures described by Delaney, Van Haren and Lopez [

39].

Caregiver satisfaction will be assessed with the Family Satisfaction in the ICU survey [

40]. Organizational outcomes, such as workflow coherence, material flows, waste segregation performance and resource consumption, will be evaluated using Material Flow Analysis [

56] and WHO-based waste audits [

52].

Environmental outcomes, including waste reduction, segregation accuracy and estimated CO

2e emissions, will be measured following guidelines from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency [

57] and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [

41].

Table 1 provides an overview of the variables and data collection instruments used to operationalize the constructs included in the conceptual framework.

Audit-based indicators will be collected at predefined time points aligned with the study timeline, using standardized sampling windows to ensure comparability across intervention and comparison sites. Audits will be conducted by trained observers who will receive standardized instruction on audit procedures, operational definitions, and data recording prior to study initiation. Inter-rater reliability will be assessed during pilot audits, with predefined agreement targets established before full data collection. Audit metrics will be standardized using appropriate denominators (e.g., per patient-day or per procedure) to enable meaningful comparison across units and time points. To minimize potential Hawthorne effects, audit procedures will be integrated into routine clinical activities where feasible, and observers will not be involved in intervention delivery or outcome assessment.

4.6. Data Analysis

Data analysis will be organized into two major stages corresponding to the psychometric validation of the KABQES-ICU (Phase 1) and the longitudinal evaluation of the educational intervention (Phase 2). In Phase 1, psychometric analyses will begin with an EFA to identify the latent structure of the instrument. EFA will be conducted using principal axis factoring with oblique rotation, appropriate when underlying psychological constructs are expected to correlate [

58]. Sampling adequacy will be evaluated through the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin index and Bartlett’s test of sphericity [

59]. Factor retention will follow parallel analysis and visual inspection of scree plots, as recommended for preventing over-extraction [

60]. The factor structure emerging from EFA will then be tested through CFA using robust maximum likelihood estimation. Model fit will be assessed using the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), following widely accepted cutoffs for structural modeling [

61]. Reliability will be examined through internal consistency coefficients (Cronbach’s α and McDonald’s ω), while construct validity will be evaluated through associations with theoretically related validated instruments, ensuring convergent and discriminant validity [

45]. Measurement invariance across demographic groups will also be assessed using multigroup CFA to ensure that scale functioning is stable across nurse subpopulations [

62].

Phase 2 will involve the evaluation of intervention effects using longitudinal data collected at baseline, immediately post-training, and at 3- and 6-month follow-ups. Analyses will explicitly account for the nested structure of the data (nurses nested within ICUs), in order to appropriately model within- and between-unit variability. Mixed-effects models will be used to estimate change trajectories in sustainability-related knowledge, attitudes and sustainable behaviors. Given the multi-level structure of the data, analyses will distinguish between individual-level outcomes (e.g., knowledge, attitudes, self-efficacy, job satisfaction) and unit-level organizational and environmental indicators (e.g., waste audits, material flows, resource consumption). Individual-level outcomes will be analyzed at the nurse level, while organizational and environmental indicators will be analyzed at the ICU-unit level using time-based comparisons and, where appropriate, multi-level modeling to account for clustering of nurses within units. Mixed-effects modeling is particularly appropriate for repeated-measures nursing research because it accounts for within-person correlations and allows estimation of both fixed and random effects [

63]. Time will be modeled both categorically and continuously to capture linear and non-linear patterns of change. Moderation effects of baseline organizational and contextual conditions will be examined by including interaction terms within mixed-effects models, while mediation pathways will be tested using longitudinal SEM.

To evaluate the mechanisms through which the intervention exerts its effects, longitudinal mediation analyses will be conducted. These analyses will examine whether changes in sustainability-related knowledge, attitudes, and self-efficacy mediate changes in sustainable nursing behaviors and related outcomes, with organizational well-being and psychological safety examined as moderators of these longitudinal relationships.

Indirect effects will be estimated using bootstrapped confidence intervals, a recommended approach for mediation in longitudinal settings [

64,

65]. To further examine causal pathways and the temporal structure of relationships among variables, longitudinal Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) will be used. Cross-lagged and autoregressive paths will allow investigation of reciprocal influences and directional effects over time, in alignment with best practices for modeling change processes in psychosocial and organizational research [

66]. Sustainable nursing behaviors will be assessed using both self-reported measures (KABQES-ICU behavioral items) and structured observational audits. Convergent validity between these sources will be examined using correlational and agreement analyses, allowing the triangulation of behavioral data and reducing the risk of common method bias.

Patient-reported outcomes (environmental comfort and satisfaction), caregiver satisfaction, and objective environmental indicators (noise, light, waste segregation accuracy and resource use) will undergo parallel longitudinal analyses using mixed-effects, generalized linear or repeated-measures models as appropriate to distributional properties. Organizational and environmental indicators derived from audits and Material Flow Analysis will be examined through time-based comparisons to detect improvements associated with the intervention.

Patterns of missing data will be assessed to determine whether data are Missing Completely at Random (MCAR), Missing at Random (MAR), or Missing Not at Random (MNAR). When appropriate, full information maximum likelihood (FIML) or multiple imputation will be applied; both are considered robust approaches for handling missingness in longitudinal designs [

67]. All analyses will be conducted using software suited to multi-level modeling and structural equation analysis.

This analytic strategy will allow the study to rigorously test the effectiveness of the educational intervention, evaluate the mediating mechanisms through which sustainability-related behaviors develop, and assess the impact of these behaviors on clinical, professional, organizational and environmental outcomes over time.

4.7. Future Cross-Cultural Adaptation of the KABQES-ICU

Although the present study focuses on the development and validation of the KABQES-ICU within a single national context, future research may extend its application through cross-cultural adaptation and validation in different healthcare systems and cultural settings. Such adaptation would follow established methodological guidelines, including forward and backward translation procedures; expert panel review to ensure semantic, conceptual, and cultural equivalence of items; and pilot testing to assess clarity and acceptability. Subsequent psychometric evaluation would involve testing measurement invariance across cultural groups to ensure the comparability of scores. These steps would support the use of the KABQES-ICU in international comparative studies and contribute to the development of globally relevant sustainability strategies in intensive care settings.

4.8. Ethical Considerations

This study is conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (1975, revised in 2013). Ethical approval for the study protocol was obtained from the appropriate Ethics Committee prior to the initiation of the study (Ethics Committee Name: Comitato Etico Territoriale Campania 2; Approval Code: AOURUGGI-0019713; Approval Date: 17 July 2025). As this manuscript describes a research protocol, data collection has not yet commenced at the time of submission. Written informed consent will be obtained from all participants prior to their participation in the study. Participation will be voluntary, and participants will be informed about the study aims, procedures, and their right to withdraw at any time without any consequences. All data will be collected and managed in accordance with applicable data protection regulations, ensuring the confidentiality and anonymity of participants.

5. Discussion

Environmental sustainability is increasingly recognized as a priority in intensive care medicine, yet existing research remains fragmented and largely focused on operational aspects such as waste metrics, carbon emissions or energy use rather than on the behavioral and organizational determinants that enable sustainable practice. Recent international initiatives, including the ESICM “Green Paper” [

18], have argued that ICUs can meaningfully reduce environmental impact without compromising patient outcomes, but they also highlight knowledge gaps regarding how ICU staff understand and enact sustainability in everyday clinical work [

68]. The present protocol responds to this gap by introducing a comprehensive, theory-driven framework that explicitly links individual cognition, psychological mechanisms, and contextual determinants to measurable sustainability-related outcomes.

While previous studies have documented the environmental burden of critical care or proposed high-level recommendations [

10,

24,

25], few have explored sustainability as a behavioral phenomenon shaped by clinical reasoning, workload, leadership and organizational culture. The qualitative findings by Bartoli, Petrosino, Midolo, Pucciarelli and Trotta [

42] show that ICU nurses experience sustainability as a cognitively demanding, ethically charged and structurally constrained process, a picture that aligns with broader research describing the tension between environmental responsibility and infection-prevention imperatives in high-acuity environments. By integrating these experiential insights into the construction of the KABQES-ICU and into the longitudinal intervention design, the present protocol advances the field beyond descriptive accounts by operationalizing sustainability within a validated theoretical structure.

Furthermore, whereas existing literature tends to examine sustainability at a single level, whether that be patient outcomes, resource use or staff perceptions, the current study adopts a multi-level perspective. This approach acknowledges that behaviors such as waste segregation, material stewardship and energy-conscious device use are not only individual actions but also embedded within relational, organizational and environmental systems. The inclusion of patient environmental comfort and caregiver satisfaction addresses concerns raised in recent studies that sustainability initiatives must not compromise, and may even enhance, patient-centered care [

39,

40]. Similarly, linking behavioral change to organizational indicators such as material flow, waste segregation accuracy and resource consumption responds to calls for empirical evidence connecting clinical behavior to quantifiable environmental outcomes.

However, the protocol also engages critically with the limitations of existing evidence. Many sustainability guidelines assume that behavior will change once staff become aware, yet research in organizational psychology suggests that knowledge alone is insufficient in environments characterized by high cognitive load and time pressure [

36,

48]. This study’s emphasis on self-efficacy, psychological safety and leadership reflects a more nuanced understanding of behavior change, consistent with theories of workplace learning and change-oriented behavior. The longitudinal design will allow the study to test whether improvements in knowledge and attitudes lead to durable behavioral change or whether structural limitations, such as availability of resources and workflow constraints, dilute intervention effects over time. This is an important gap in the literature, which currently lacks longitudinal evidence from real ICU settings.

Finally, by situating sustainability research within critical care, a setting often perceived as incompatible with environmental responsibility, the protocol challenges dominant assumptions and aligns with emerging research showing that ICUs can indeed adopt sustainable practices when supported by adequate organizational structures and staff engagement [

52,

53,

54,

57]. In doing so, it positions sustainability not as an optional add-on but as a dimension of ICU quality and safety.

6. Strengths and Limitations

A major strength of this study is its integration of qualitative foundations, concept analysis and the KAB model into a coherent conceptual framework capable of explaining how sustainable practices emerge in high-acuity settings. The development of the KABQES-ICU addresses the current lack of validated instruments specifically tailored to ICU sustainability, and the use of longitudinal modeling will allow the study to move beyond cross-sectional associations toward understanding causal pathways. The inclusion of multiple stakeholder groups, nurses, patients, and caregivers and the use of both subjective and objective indicators (e.g., environmental monitoring, waste audits, material flow analysis) provide a comprehensive and methodologically rigorous evaluation of sustainability in real clinical environments.

Nevertheless, the study is not without limitations. Conducting the intervention within ICUs in a single national context may limit generalizability, as sustainability practices are shaped by local regulations, availability of supplies and institutional priorities. The reliance on self-reported data for several constructs introduces the possibility of social desirability and recall bias, although observational and environmental measures will help mitigate this limitation. Attrition across the six-month follow-up may affect longitudinal power despite the a priori sample size adjustments. Furthermore, external organizational or policy changes occurring during the study period may influence sustainability practices independently of the intervention, complicating causal interpretation.

Despite these constraints, the protocol is expected to generate high-value empirical and methodological contributions that will support future implementation studies, cross-cultural validation efforts and the development of sustainable ICU models aligned with international environmental and clinical priorities.

In addition, the proposed framework is designed to be applicable across different levels of practice while remaining firmly rooted in the intensive care context. At the micro level, it can guide the assessment and development of sustainability-related competencies among individual ICU nurses through targeted educational interventions. At the meso level, the framework supports unit-based quality improvement initiatives by linking behavioral change to organizational conditions, workflow processes, and environmental performance indicators. At the macro level, the framework may inform institutional sustainability strategies by providing a structured model that connects staff behaviors with measurable organizational and environmental outcomes. Although the framework has been specifically developed for intensive care unit settings, its underlying structure may be adapted to other high-acuity healthcare contexts, provided that appropriate contextual modifications and validation procedures are undertaken.

7. Expected Contributions

This research program is expected to make several significant contributions to the emerging field of environmental sustainability in intensive care. First, it will provide the first rigorously validated instrument specifically designed to assess sustainability-related knowledge, attitudes and behaviors among ICU nurses, addressing a critical methodological gap in the literature. The KABQES-ICU will support future research by offering a standardized, psychometrically sound tool for evaluating competencies and monitoring the impact of educational or organizational interventions.

Second, the longitudinal design will generate empirical evidence on how sustainability-related constructs evolve over time and how educational interventions influence the psychological and organizational mechanisms underlying behavior change. By integrating individual, relational, organizational and environmental outcomes, the study will offer a comprehensive understanding of how sustainable practices are enacted within complex, high-acuity clinical environments.

Finally, by linking behavioral changes to concrete organizational and environmental indicators, such as waste segregation performance, material flows and resource consumption, the study will demonstrate how sustainability initiatives can align with ICU quality and safety objectives. This will provide hospitals and policymakers with actionable insights for designing effective sustainability strategies that are grounded in real ICU workflows and constraints.

8. Implications for Research and Practice

This study has important implications for both research and clinical practice. From a research perspective, it will establish a conceptual and methodological foundation for investigating sustainability in critical care, enabling future studies to build on validated constructs and causal pathways. The availability of a validated instrument tailored to ICU practice will facilitate cross-cultural comparisons, intervention testing, and system-level evaluations of sustainability programs.

For clinical practice, the study will offer evidence on how sustainability training can be integrated into ICU education and professional development and how such training can enhance not only environmental performance but also nurse well-being, patient experience and organizational efficiency. The findings will support ICU leaders in identifying structural and cultural elements that enable sustainable behavior, guiding the development of resource-efficient workflows, targeted training programs and supportive organizational climates.

More broadly, the results will contribute to embedding sustainability within the core values of intensive care medicine. By demonstrating that sustainable practices can be aligned with patient safety, ethical responsibility and clinical excellence, the study will help shift sustainability from a peripheral concern to a routine component of ICU quality improvement and strategic planning.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.B.; software, F.P., L.M., F.T. and D.B.; validation, G.P. and D.B.; formal analysis, F.P., D.B., F.T. and L.M.; investigation, F.T. and L.M.; data curation, F.P., L.M. and D.B.; writing—original draft preparation, L.M., F.T. and D.B.; writing—review and editing, F.P., M.F., F.T., L.M. and D.B.; supervision, M.F., F.T., G.P., M.D.M., E.V. and R.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Center of Excellence for Nursing Culture and Research, grant number 8763.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Comitato Etico Territoriale Campania 2 (protocol no. AOURUGGI-0019713-2025—17 July 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent will be obtained from all participants prior to enrollment.

Data Availability Statement

No data were generated or analyzed during the current study, as this manuscript describes a study protocol. Data generated from the study will be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, subject to ethical approval and data protection regulations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CO2e | Carbon dioxide equivalent |

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index |

| EFA | Exploratory Factor Analysis |

| EHEP | Environmental Health Engagement Profile |

| EPA | Environmental Protection Agency |

| ESICM | European Society of Intensive Care Medicine |

| EQ-5D | EuroQol 5-Dimension Questionnaire |

| FS-ICU | Family Satisfaction in the Intensive Care Unit Survey |

| GDPR | General Data Protection Regulation |

| G*Power | Statistical Power Analysis Program |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| ICUESS | Intensive Care Unit Environmental Stressors Scale |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| KAB | Knowledge, Attitudes and Behaviors |

| KABQES-ICU | Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behaviors Questionnaire on Environmental Sustainability in Intensive Care Units |

| KMO | Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure |

| MAR | Missing At Random |

| MCAR | Missing Completely at Random |

| MNAR | Missing Not at Random |

| MLQ | Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire |

| MMSS | McCloskey/Mueller Satisfaction Scale |

| NASA-TLX | National Aeronautics and Space Administration Task Load Index |

| OWBQ | Organizational Well-Being Questionnaire |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| SEM | Structural Equation Modeling |

| SRMR | Standardized Root Mean Square Residual |

| TLI | Tucker–Lewis Index |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Kümmerer, K. The presence of pharmaceuticals in the environment due to human use—present knowledge and future challenges. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 2354–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzen, M.; Malik, A.; Li, M.; Fry, J.; Weisz, H.; Pichler, P.P.; Chaves, L.S.M.; Capon, A.; Pencheon, D. The environmental footprint of health care: A global assessment. Lancet Planet Health 2020, 4, e271–e279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olawade, D.B.; Popoola, T.T.; Egbon, E.; David-Olawade, A.C. Sustainable healthcare practices: Pathways to a carbon-neutral future for the medical industry. Sustain. Futures 2025, 9, 100783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, N.; Adger, W.N.; Agnolucci, P.; Blackstock, J.; Byass, P.; Cai, W.; Chaytor, S.; Colbourn, T.; Collins, M.; Cooper, A.; et al. Health and climate change: Policy responses to protect public health. Lancet 2015, 386, 1861–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. COP26 Special Report on Climate Change and Health: The Health Argument for Climate Action; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hunfeld, N.; Diehl, J.C.; Timmermann, M.; van Exter, P.; Bouwens, J.; Browne-Wilkinson, S.; de Planque, N.; Gommers, D. Circular material flow in the intensive care unit-environmental effects and identification of hotspots. Intensive Care Med. 2023, 49, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGain, F.; McAlister, S. Reusable versus single-use ICU equipment: What’s the environmental footprint? Intensive Care Med. 2023, 49, 1523–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- See, K.C. Improving environmental sustainability of intensive care units: A mini-review. World J. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 12, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smale, E.; Baid, H.; Balan, M.; McGain, F.; McAlistar, S.; De Waele, J.J.; Diehl, J.C.; Van Raaij, E.; van Genderen, M.; Tibboel, D.; et al. The green ICU: How to interpret green? A multiple perspective approach. Crit. Care 2025, 29, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortimer, F.; Isherwood, J.; Wilkinson, A.; Vaux, E. Sustainability in quality improvement: Redefining value. Future Healthc. J. 2018, 5, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J.; Grose, J.; O’Connor, A.; Bradbury, M.; Kelsey, J.; Doman, M. Nursing students’ attitudes towards sustainability and health care. Nurs. Stand. 2015, 29, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherman, J.D.; Raibley, L.A., IV; Eckelman, M.J. Life Cycle Assessment and Costing Methods for Device Procurement: Comparing Reusable and Single-Use Disposable Laryngoscopes. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 127, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attia, N.M.; Hamed, A.E.M.; Elbakry, M.; Barakat, A.M.; Mohamed, H.S. Navigating sustainable practice: Environmental awareness and climate change as mediators of green competence of nurses. BMC Nurs. 2025, 24, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luque-Alcaraz, O.M.; Aparicio-Martínez, P.; Gomera, A.; Vaquero-Abellán, M. The environmental awareness of nurses as environmentally sustainable health care leaders: A mixed method analysis. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, H.; Mohamed, M.; Hablass, A. Effectiveness of Educational Program on Nurses’ Performance toward Sustainable Development and Green Practice in Intensive Care Unit. Egypt. J. Health Care 2025, 16, 337–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.J.; Lee, H.; Jang, S.J. Factors affecting environmental sustainability attitudes among nurses—Focusing on climate change cognition and behaviours: A cross-sectional study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoromba, M.A.; El-Gazar, H.E. Nurses’ attitudes, practices, and barriers toward sustainability behaviors: A qualitative study. BMC Nurs. 2025, 24, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Waele, J.J.; Hunfeld, N.; Baid, H.; Ferrer, R.; Iliopoulou, K.; Ioan, A.M.; Leone, M.; Ostermann, M.; Scaramuzzo, G.; Theodorakopoulou, M.; et al. Environmental sustainability in intensive care: The path forward. An ESICM Green Paper. Intensive Care Med. 2024, 50, 1729–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.T.W.; Moraga Masson, F.; McGain, F.; Stancliffe, R.; Pilowsky, J.K.; Nguyen, N.; Bell, K.J.L. Interventions to reduce low-value care in intensive care settings: A scoping review of impacts on health, resource use, costs, and the environment. Intensive Care Med. 2024, 50, 2019–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, A.A.; Abdelall, H.A.; Ali, H.I. Enhancing nurses’ sustainability consciousness and its effect on green behavior intention and green advocacy: Quasi-experimental study. BMC Nurs. 2025, 24, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anåker, A.; Elf, M. Sustainability in nursing: A concept analysis. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2014, 28, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baid, H.; Richardson, J.; Scholes, J.; Hebron, C. Sustainability in critical care practice: A grounded theory study. Nurs. Crit. Care 2021, 26, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckelman, M.J.; Sherman, J. Environmental Impacts of the U.S. Health Care System and Effects on Public Health. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0157014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacNeill, A.J.; Lillywhite, R.; Brown, C.J. The impact of surgery on global climate: A carbon footprinting study of operating theatres in three health systems. Lancet Planet Health 2017, 1, e381–e388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, J.D.; MacNeill, A.; Thiel, C. Reducing Pollution From the Health Care Industry. JAMA 2019, 322, 1043–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Wölfing, S.; Fuhrer, U. Environmental Attitude and Ecological Behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 1999, 19, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothe, E.J.; Mullan, B.A. Interaction effects in the theory of planned behaviour: Predicting fruit and vegetable consumption in three prospective cohorts. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2015, 20, 549–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R.; Nilsson, A. Personal and social factors that influence pro-environmental concern and behaviour: A review. Int. J. Psychol. 2014, 49, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2010, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Teng, M.; Han, C. How does environmental knowledge translate into pro-environmental behaviors?: The mediating role of environmental attitudes and behavioral intentions. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 728, 138126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Kalof, L. Value Orientations, Gender, and Environmental Concern. Environ. Behav. 1993, 25, 322–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelezny, L.C.; Chua, P.P.; Aldrich, C. New Ways of Thinking about Environmentalism: Elaborating on Gender Differences in Environmentalism. J. Soc. Issues 2002, 56, 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiral, O.; Talbot, D.; Paillé, P. Leading by Example: A Model of Organizational Citizenship Behavior for the Environment. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2013, 24, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carayon, P.; Schoofs Hundt, A.; Karsh, B.T.; Gurses, A.P.; Alvarado, C.J.; Smith, M.; Flatley Brennan, P. Work system design for patient safety: The SEIPS model. Qual. Saf. Health Care 2006, 15, i50–i58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avallone, F.; Paplomatas, A. Salute Organizzativa. Psicologia del Benessere nei Contesti Lavorativi; Raffaello Cortina Editore: Milan, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson, A. Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams. Adm. Sci. Q. 2016, 44, 350–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Möser, G. Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotheridge, C.M.; Lee, R.T. Development and validation of the Emotional Labour Scale. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 76, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, L.J.; Van Haren, F.; Lopez, V. Sleeping on a problem: The impact of sleep disturbance on intensive care patients—A clinical review. Ann. Intensive Care 2015, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyland, D.K.; Rocker, G.M.; Dodek, P.M.; Kutsogiannis, D.J.; Konopad, E.; Cook, D.J.; Peters, S.; Tranmer, J.E.; O’Callaghan, C.J. Family satisfaction with care in the intensive care unit: Results of a multiple center study. Crit. Care Med. 2002, 30, 1413–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. AR5 Synthesis Report: Climate Change 2014; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bartoli, D.; Petrosino, F.; Midolo, L.; Pucciarelli, G.; Trotta, F. Critical care nurses’ experiences on environmental sustainability: A qualitative content analysis. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2025, 87, 103847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comrey, A.L.; Lee, H.B. A First Course in Factor Analysis; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, A.B.; Osborne, J. Best Practices in Exploratory Factor Analysis: Four Recommendations for Getting the Most From Your Analysis. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2005, 10, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, J.K.; Hendrickson, K.C.; Ercolano, E.; Quackenbush, R.; Dixon, J.P. The environmental health engagement profile: What people think and do about environmental health. Public Health Nurs. 2009, 26, 460–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M.; Avolio, B.J. Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ); Mind Garden, Inc.: Redwood City, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.G. Nasa-Task Load Index (NASA-TLX); 20 Years Later. Proc. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. Annu. Meet. 2006, 50, 904–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, C.W.; McCloskey, J.C. Nurses’ job satisfaction: A proposed measure. Nurs. Res. 1990, 39, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabernero, C.; Hernández, B. Self-Efficacy and Intrinsic Motivation Guiding Environmental Behavior. Environ. Behav. 2010, 43, 658–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Safe Management of Wastes from Health-Care Activities; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ballard, K.S. Identification of environmental stressors for patients in a surgical intensive care unit. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 1981, 3, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çınar, S.; Aslan, F.; Kurtoğlu, T. Yoğun Bakım Ünitesi Çevresel Stresörler Ölçeği: Geçerlik ve Güvenirlik Çalışması. Yoğun Bakım Hemşireliği Dergisi 2011, 15, 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran, J.; Ganong, L.H. A comparison of nurses’ and patients’ perceptions of intensive care unit stressors. J. Adv. Nurs. 1989, 14, 1038–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allesch, A.; Brunner, P.H. Material Flow Analysis as a Decision Support Tool for Waste Management: A Literature Review. J. Ind. Ecol. 2015, 19, 753–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorneloe, S.A.; Weitz, K.; Jambeck, J. Application of the US decision support tool for materials and waste management. Waste Manag. 2007, 27, 1006–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabrigar, L.R.; Wegener, D.T.; MacCallum, R.C.; Strahan, E.J. Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychol. Methods 1999, 4, 272–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika 1974, 39, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayton, J.C.; Allen, D.G.; Scarpello, V. Factor Retention Decisions in Exploratory Factor Analysis: A Tutorial on Parallel Analysis. Organ. Res. Methods 2004, 7, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.t.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenberg, R.J.; Lance, C.E. A Review and Synthesis of the Measurement Invariance Literature: Suggestions, Practices, and Recommendations for Organizational Research. Organ. Res. Methods 2000, 3, 4–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, J.D.; Willett, J.B. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis: Modeling Change and Event Occurrence; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mackinnon, D.P.; Lockwood, C.M.; Williams, J. Confidence Limits for the Indirect Effect: Distribution of the Product and Resampling Methods. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2004, 39, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curran, P.J.; Howard, A.L.; Bainter, S.A.; Lane, S.T.; McGinley, J.S. The separation of between-person and within-person components of individual change over time: A latent curve model with structured residuals. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 82, 879–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, T.; Enders, C. Maximum Likelihood and Multiple Imputation Missing Data Handling: How They Work, and How to Make Them Work in Practice; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; pp. 27–51. [Google Scholar]

- Iliopoulou, K.; Leone, M.; Hunfeld, N.; Ferrer, R.; Baid, H.; Ostermann, M.; Scaramuzzo, G.; Touw, H.; Ioan, A.M.; Theodorakopoulou, M.; et al. Environmental sustainability in intensive care: An international survey of intensive care professionals’views, practices and proposals to the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. J. Crit. Care 2025, 88, 155079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |