Identification of Regional Disparities and Obstacle Factors in Basic Elderly Care Services in China—Based on the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

1.2. Literature Review

2. Data Sources and Indicator Selection

3. Research Methods

3.1. Entropy Weight Method

3.2. Dagum Gini Coefficient

3.3. Kernel Density Estimation

3.4. Spatial Exploratory Analysis

3.5. Obstacle Degree Model

4. Empirical Results and Discussion

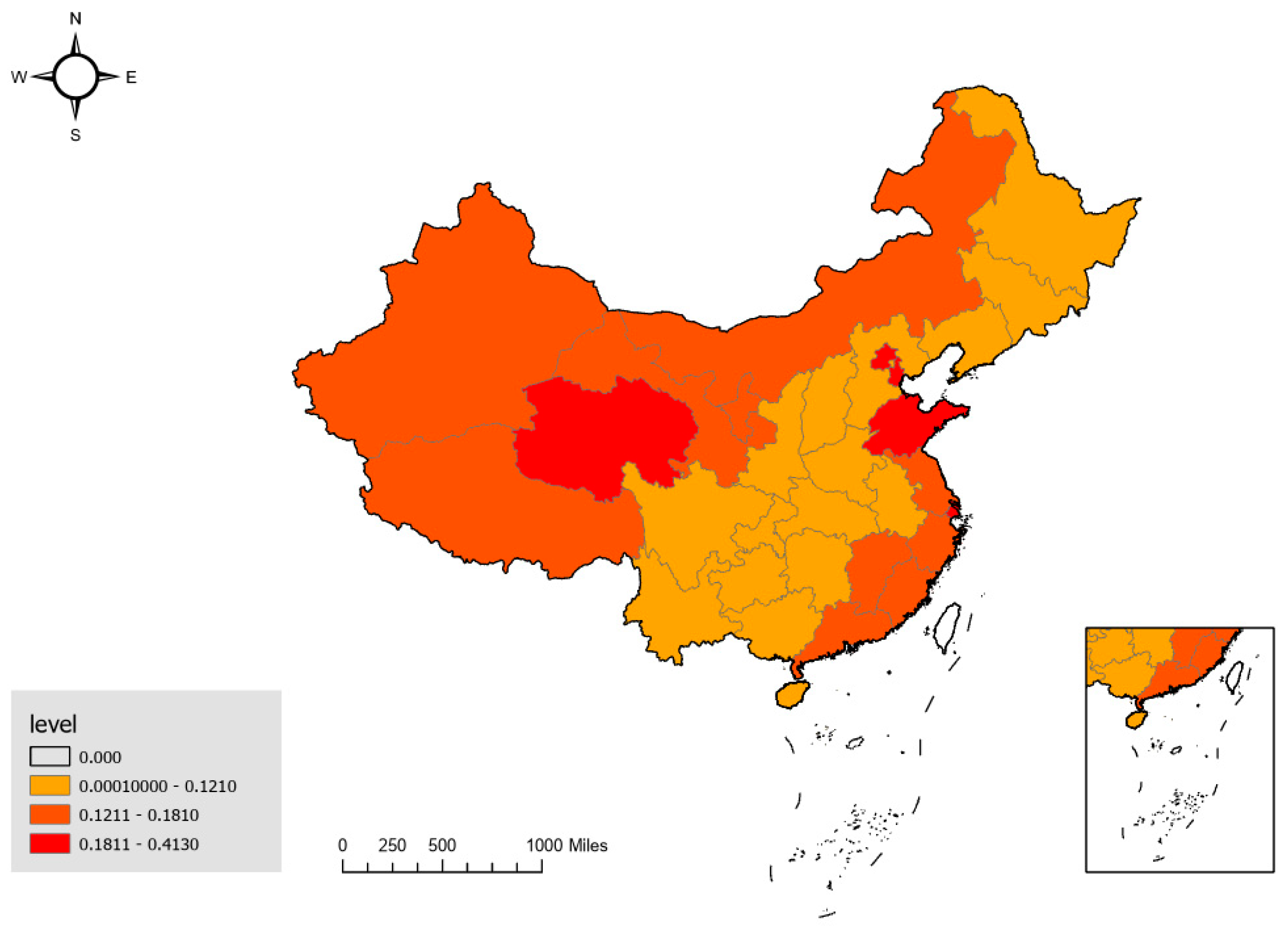

4.1. Entropy Weight Method

4.2. Dagum Gini Coefficient

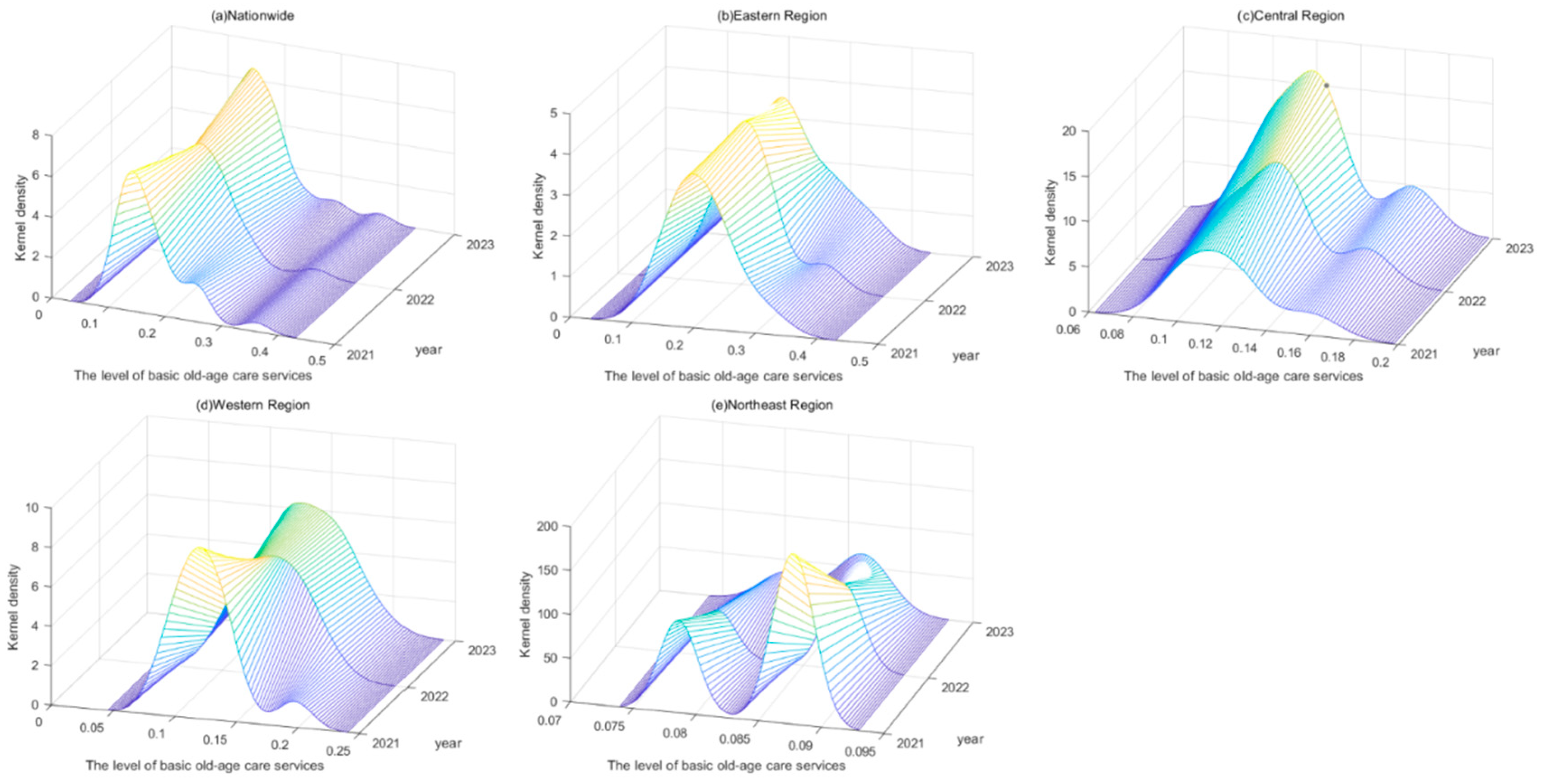

4.3. Kernel Density Estimation

4.3.1. Distribution Position

4.3.2. Peak Distribution

4.3.3. Distribution Extensibility

4.3.4. Number of Peaks

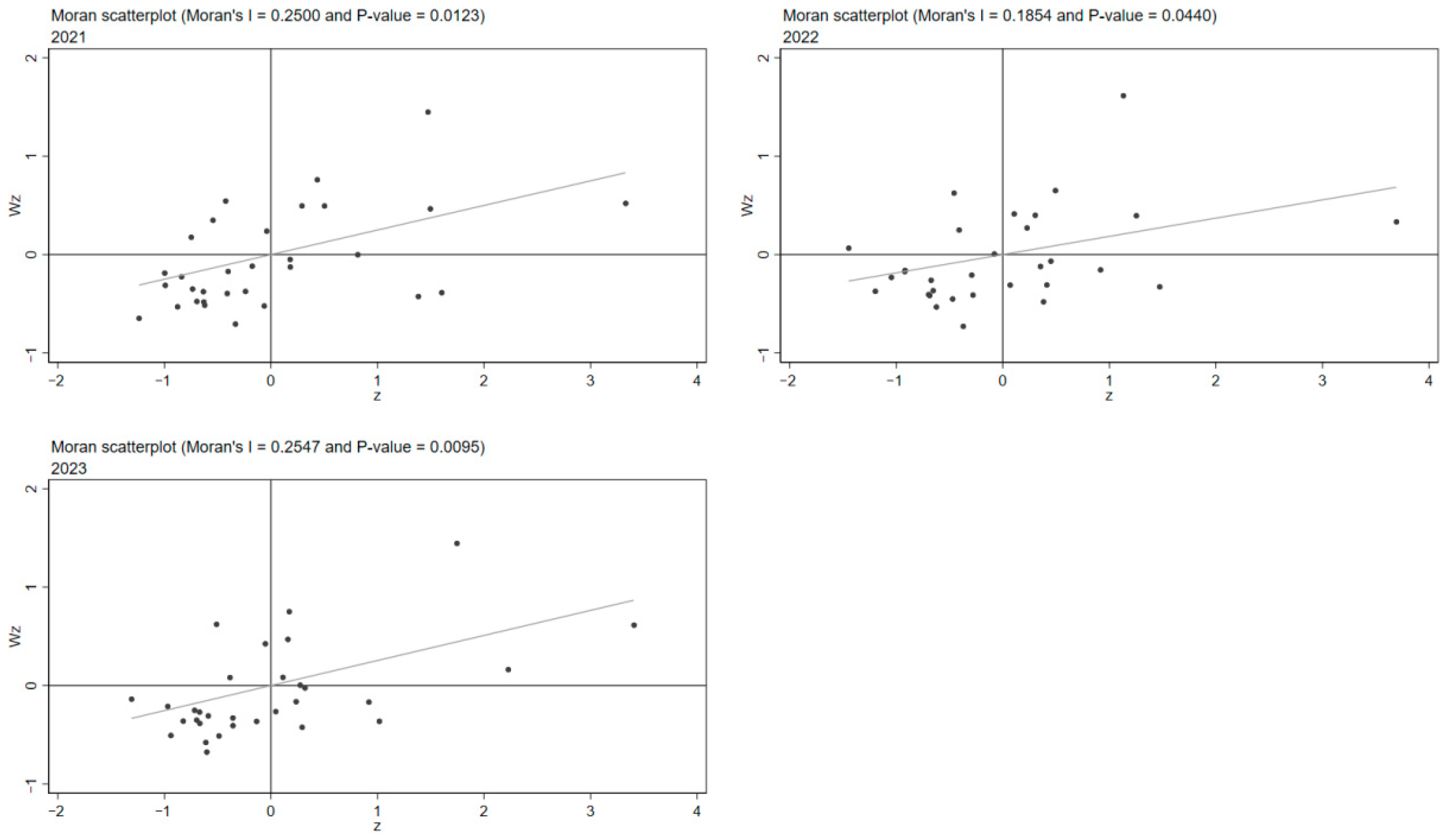

4.4. Exploratory Spatial Analysis

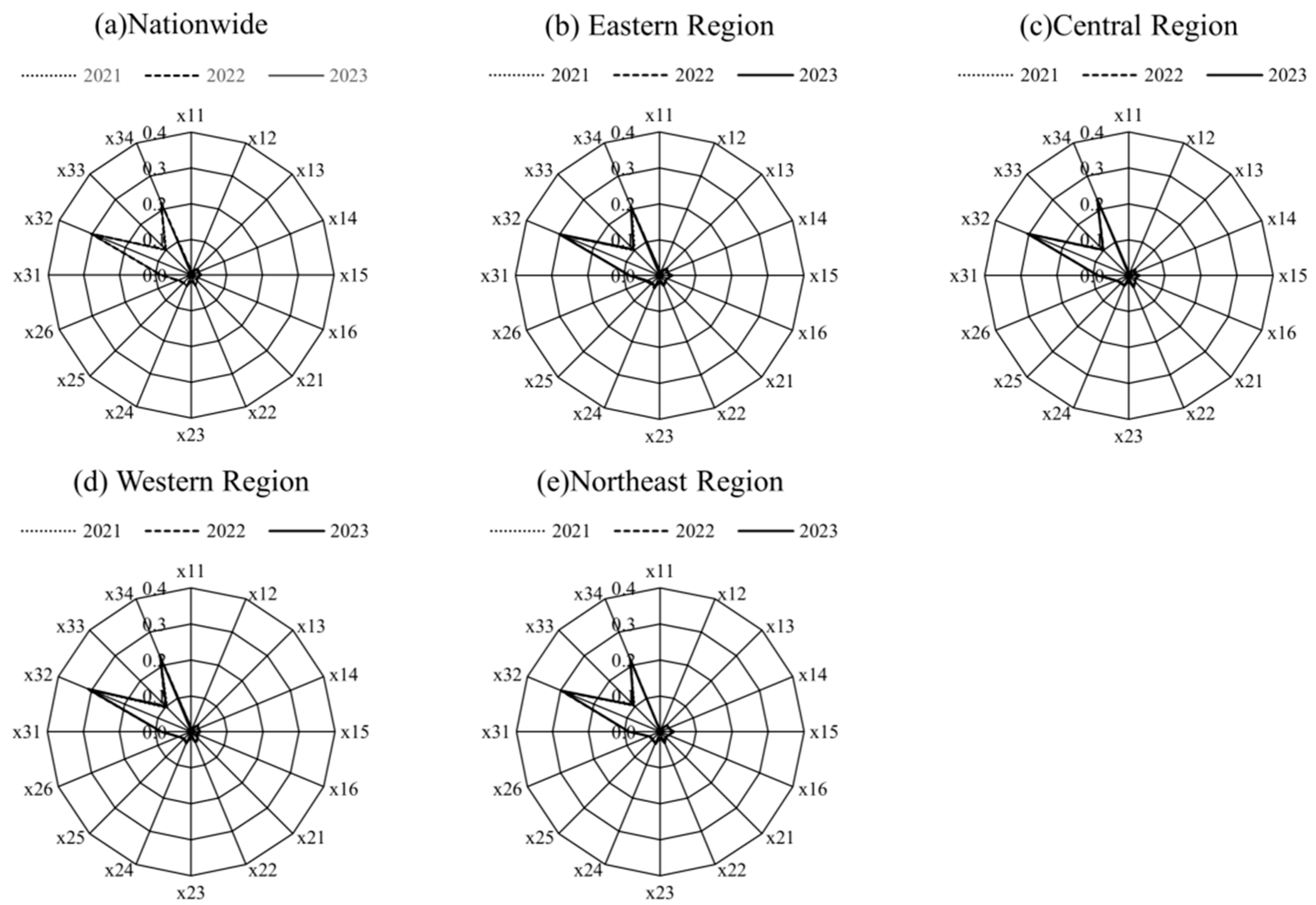

4.5. Degree of Obstacle

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

5.1. Strengthen the Construction of a Multi-Subject Supply Network to Enhance the Comprehensive Efficiency of BECS

5.2. Promote the Coordinated Development of Human, Financial, and Material Resources Across Regions and Bridge the Gap in BECS Levels

5.3. Enhance the Government’s Governance Capacity and Promote the Quality and Efficiency Improvement of BECS Levels

6. Research Outlook and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tanaka, K.; Johnson, N.E. The Shifting Roles of Women in Intergenerational Mutual Caregiving in Japan: The Importance of Peace, Population Growth, and Economic Expansion. J. Fam. Hist. 2008, 33, 96–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, K.T. An Exploration of Actions of Filial Piety. J. Aging Stud. 1998, 12, 369–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, K.; Teerawichitchainan, B. Living Arrangements and Psychological Well-Being of the Older Adults After the Economic Transition in Vietnam. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2015, 70, 957–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Mu, X.; Yang, W.; Gui, Q. The Spatial Mobility Network and Influencing Factors of the Higher Education Population in China. Sci. Public Policy 2024, 51, 406–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y. Money for Time? Evidence From Intergenerational Interactions in China. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2026, 45, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, Q.; Huang, Y. The Influence of Intergenerational Support on the Consumption Choice of Elderly Institutions. Consum. Econ. 2021, 37, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, T.; Ma, D. Evaluation on the Resource Density Distribution and Equalization of Community Home-Based Services for the Elderly from the Perspective of Inclusive Development. J. Northwest Univ. 2020, 50, 108–119. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, H.; Cheng, H.; Yang, Y.; Fan, C.; Huang, N.; Huang, A. Research on the Evaluation Method of Senior Care Service Resources Allocation Scheme Based on the Perspective of Data Elements. Oper. Res. Manag. Sci. 2023, 32, 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, S.; Hu, Y. Measurement of New Quality Productivity Development Level and Factor Identification of Obstacle Factors Based on the Analysis of Provincial Panel Data in China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedel, M.; Kraus, M.; Mayer, S. Organization and Supply of Long-Term Care Services for the Elderly: A Bird’s-Eye View of Old and New EU Member States. Soc. Policy Adm. 2016, 50, 824–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Xu, T.; Huang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Gui, J.; Fu, Y.; Chen, C. The Temporal and Spatial Discrepancies in the Home and Community—Based Services Supply for the Disabled Elderly in China: Evidence from the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey (CLHLS), 2008—2018. Mod. Prev. Med. 2022, 49, 3535–3547. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Zhang, C. Regional Differences, Spatial Misalignment and Equalization Paths in Resource Allocation for Community Elderly Services. Public Financ. Res. 2024, 3, 94–110. [Google Scholar]

- Devroey, D.; Van Casteren, V.; De Lepeleire, J. Revealing Regional Differences in the Institutionalization of Adult Patients in Homes for the Elderly and Nursing Homes: Results of the Belgian Network of Sentinel GPs. Fam. Pract. 2001, 18, 39–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, J.J.; Zhu, M.; Hirdes, J.P.; Stolee, P. Rehabilitation Therapies for Older Clients of the Ontario Home Care System: Regional Variation and Client-Level Predictors of Service Provision. Disabil. Rehabil. 2015, 37, 625–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Hu, R.; Liu, H. Measurement and Regional Disparities in Equalization of Basic Elderly Care Services in the Southwest Region. East China Econ. Manag. 2024, 38, 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Shi, Z.; Lyu, H. How Do Fiscal Decentralization and Transfer Payment Disparities Widen Inequities in Elderly Care Access and Utilization in China? J. Chin. Gov. 2025, 10, 607–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trydegård, G.B.; Thorslund, M. Inequality in the Welfare State? Local Variation in Care of the Elderly: The Case of Sweden. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 2001, 10, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagenas, D.; McLaughlin, D.; Dobson, A. Regional Variation in the Survival and Health of Older Australian Women: A Prospective Cohort Study. Aust N. Z. J. Public Health 2009, 33, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, T.; Feng, D. Study on Regional Differences, Dynamic Evolution and Convergence of Carbon Emission Intensity in China. J. Quant. Technol. Econ. 2022, 39, 67–87. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Liao, K.; Zhou, X. Analysis of Regional Differences and Dynamic Mechanisms of Agricultural Carbon Emission Efficiency in China’s Seven Agricultural Regions. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 38258–38284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, L.; Tang, L. Regional Differences and Spatial-Temporal Evolution Characteristics of Digital Economy Development in China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Liu, Q. The spatio-temporal differentiation of basic elderly care services in China and its influencing factors. Dong Yue Trib. 2024, 45, 160–166. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Han, Z.; Zhu, S. Research on the Supply and Demand Coupling Coordination of the Elderly Services: Based on the Perspective of Spatial Econometrics. Popul. Dev. 2024, 30, 122–134, 162. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, B. Improving cyberspace security situation from perspective of “Talent, Finance and Infrastructure”. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. 2022, 37, 53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, J.; Song, Q.; Liu, H.; Jiang, Z.; Ge, C.; Li, D. The Coupling Coordination between Health Service Supply and Regional Economy in China: Spatio-Temporal Evolution and Convergence. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1352141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozcan, K.A. Sustainability Ranking of Turkish Universities with Different Weighting Approaches and the TOPSIS Method. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Yan, J. The Measurement of Integration Development Level of Digital Economy and Cultural Tourism Industry and Analyze of Its Spatiotemporal Differentiation Evolution. Resour. Dev. Mark. 2025, 41, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, J.; Wang, G.; Meng, X.; Zhang, Q. Agricultural New-Quality Productivity in China: Statistical Measurement and Spatial-Temporal Evolution. World Surv. Res. 2025, 7, 26–39. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Du, G. Regional Inequality and Stochastic Convergence in China. J. Quant. Technol. Econ. 2017, 34, 43–59. [Google Scholar]

- Di, Y.; Lu, Y.; Razzaq, A. International Differences and Dynamic Evolution of Trade in Digitally Deliverable Services. Technol. Soc. 2025, 81, 102781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Gong, R.; Feng, D. Regional Differences, Dynamic Evolution and Convergence Characteristics of High-quality Development Level of Manufacturing Industry in China. Stat. Decis. 2023, 39, 84–90. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Guo, L.; Qiao, L. Spatial-Temporal Pattern and Dynamic Evolution of Logistics Efficiency in China. J. Quant. Technol. Econ. 2021, 38, 57–74. [Google Scholar]

- Gedamu, W.T.; Plank-Wiedenbeck, U.; Wodajo, B.T. A Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis of Road Traffic Crash by Severity Using Moran’s I Spatial Statistics: A Comparative Study of Addis Ababa and Berlin Cities. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2024, 200, 107535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, A. Analysis on Evolution of Radiation Effect of Sericulture Industry in Jiangsu. Sci. Seric. 2023, 49, 568–574. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, S.; Yin, F. Interaction Mechanism and Coupling Strategy of Higher Education and Innovation Capability in China Based on Interprovincial Panel Data from 2010 to 2022. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Jia, J.; Liu, Y. Coupling and Coordination of Agricultural Digitalization and Green, Low-Carbon Development in China and Obstacle Factors Analysis. Environ. Sci. 2025, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Yan, Q.; Pan, Q.; Chen, X.; Li, G. Identification and Classification of Urban Shrinkage in Northeast China. Land 2023, 12, 1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Yao, C. Exploring the Association between Shrinking Cities and the Loss of External Investment: An Intercity Network Analysis. Cities 2021, 119, 103351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, X.; Guo, Q.; Lin, R. Research on Optimal Subsidy Policy to Increase Effective Supply of Elderly Services. Oper. Res. Manag. Sci. 2025, 34, 30–36. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, J. “Reverse Feeding”, the Structure of Children and the Labor Participation of the Elderly Population. Popul. Dev. 2021, 27, 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative Platforms as a Governance Strategy. J. Publ. Adm. Res. Theory 2018, 28, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blokland, T.; Van Eijk, G. Do People Who Like Diversity Practice Diversity in Neighbourhood Life? Neighbourhood Use and the Social Networks of ‘Diversity-Seekers’ in a Mixed Neighbourhood in the Netherlands. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2010, 36, 313–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, J.; Rao, K. Spatio-temporal evolution of the coordinated development of China’s pension resources alloca-tion and service utilization: Based on the hierarchical analysis framework of institutions. Chin. J. Health Policy 2022, 15, 30–40. [Google Scholar]

- Le Galès, P.; Vitale, T. Governing the Large Metropolis. A Res. Agenda 2024, 2, 115–134. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, X.; Qu, Y.; Mishra, A.K.; Mann, M.E.; Zhang, L.; Bai, C.; Li, M.; Lin, J.; Wei, J.; Yu, Q.; et al. Elderly Vulnerability to Temperature-Related Mortality Risks in China. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eado5499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grekousis, G. Geographical-XGBoost: A New Ensemble Model for Spatially Local Regression Based on Gradient-Boosted Trees. J. Geogr. Syst. 2025, 27, 169–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criterion Layer | Indicator Layer | Indicator Direction | Directly Related SDGs | Indirectly Related SDGs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elderly Care Facilities | x11 Number of elderly care institutions | + | SDG9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure), SDG11 (Sustain-able Cities and Communities) | SDG10 (Reduced Inequalities), SDG16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions), SDG17 (Partnerships for the Goals) |

| x12 Number of beds in elderly care institutions at the end of the year | + | |||

| x13 Building area of elderly care institutions | + | |||

| x14 Number of community elderly care service institutions and facilities | + | |||

| x15 Total number of beds in community elderly care services | + | |||

| x16 Building area of community elderly care service institutions | + | |||

| Human Resources Assurance | x21 Number of employees in elderly care institutions at the end of the year | + | SDG4 (Quality Education), SDG8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) | |

| x22 Number of employees with a bachelor’s degree or above in elderly care institutions | + | |||

| x23 Number of social workers in elderly care institutions | + | |||

| x24 Number of employees in community elderly care services at the end of the year | + | |||

| x25 Number of employees in community elderly care services at the end of the year | + | |||

| x26 Number of social workers in community elderly care services | + | |||

| Welfare Subsidy | x31 Subsidy for the Elderly Aged 80 and above | + | SDG1 (No Poverty), SDG3 (Good Health and Well-being) | |

| x32 Care Subsidy | + | |||

| x33 Elderly Care Service Subsidy | + | |||

| x34 Comprehensive Subsidy | + |

| Year | G | GW | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern | Central | Western | Northeast | ||

| 2021 | 0.275 | 0.229 | 0.211 | 0.225 | 0.020 |

| 2022 | 0.268 | 0.268 | 0.150 | 0.207 | 0.049 |

| 2023 | 0.277 | 0.299 | 0.113 | 0.200 | 0.034 |

| Year | Gnb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| East-Central | East-West | East-Northeast | Central-West | Central-Northeast | West-Northeast | |

| 2021 | 0.327 | 0.328 | 0.389 | 0.225 | 0.190 | 0.190 |

| 2022 | 0.322 | 0.298 | 0.430 | 0.195 | 0.176 | 0.248 |

| 2023 | 0.339 | 0.321 | 0.438 | 0.181 | 0.148 | 0.231 |

| Year | Gt (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Within the Region | Between Regions | Super Variable Density | |

| 2021 | 24.864 | 55.084 | 20.052 |

| 2022 | 26.336 | 51.390 | 22.274 |

| 2023 | 26.451 | 53.166 | 20.383 |

| Year | Global Moran Index | p-Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 0.250 | 0.012 | Significant |

| 2022 | 0.184 | 0.044 | Significant |

| 2023 | 0.255 | 0.009 | Significant |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cao, Y.; Liu, H.; Li, K.; Wu, F. Identification of Regional Disparities and Obstacle Factors in Basic Elderly Care Services in China—Based on the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2026, 18, 312. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010312

Cao Y, Liu H, Li K, Wu F. Identification of Regional Disparities and Obstacle Factors in Basic Elderly Care Services in China—Based on the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):312. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010312

Chicago/Turabian StyleCao, Yiming, Hewei Liu, Kelu Li, and Fan Wu. 2026. "Identification of Regional Disparities and Obstacle Factors in Basic Elderly Care Services in China—Based on the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 312. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010312

APA StyleCao, Y., Liu, H., Li, K., & Wu, F. (2026). Identification of Regional Disparities and Obstacle Factors in Basic Elderly Care Services in China—Based on the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability, 18(1), 312. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010312