An Overview and Lessons Learned from the Implementation of Climate-Smart Agriculture (CSA) Initiatives in West and Central Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

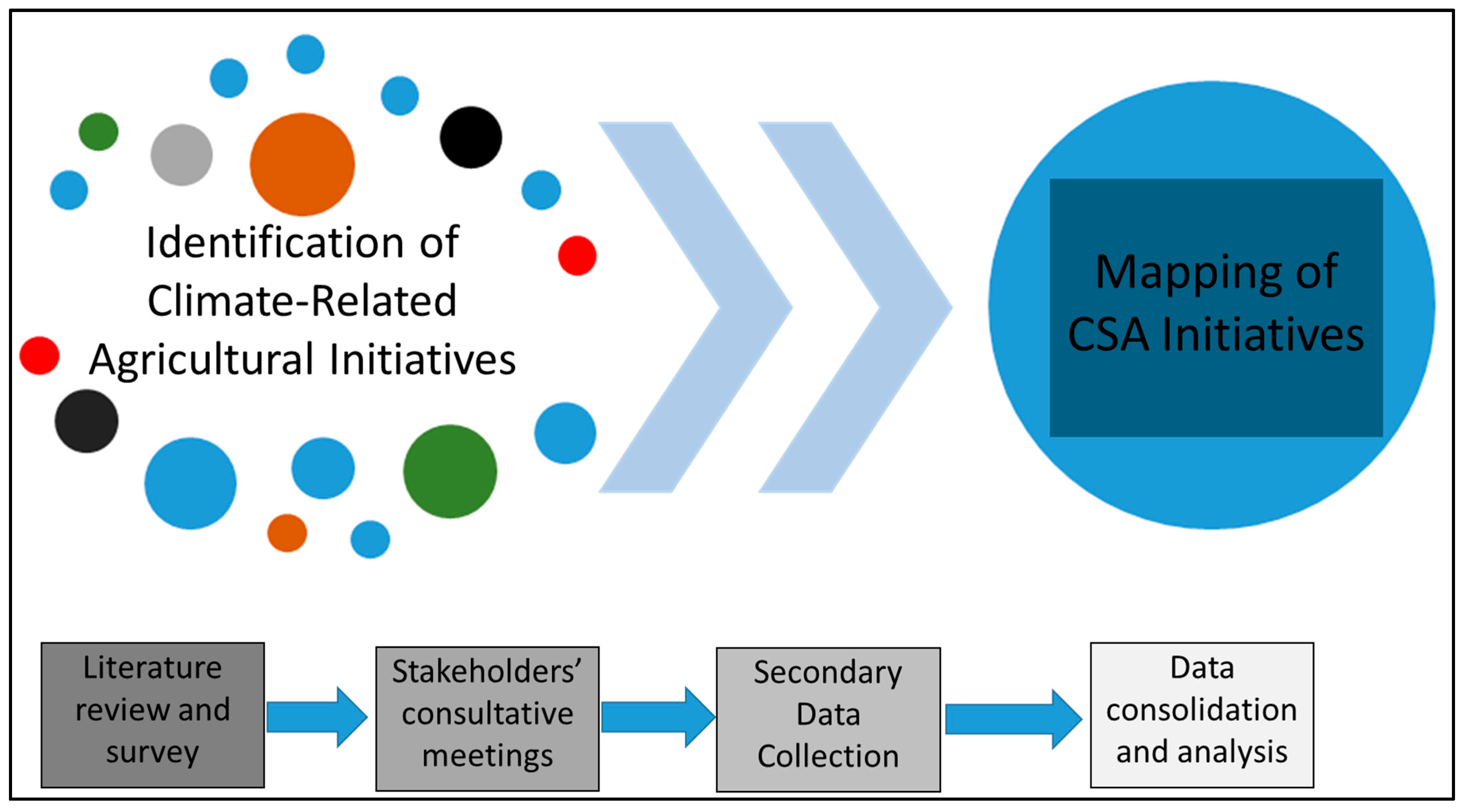

2. Methodology

2.1. Scope of the Study

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

- Literature review and survey: systematic review of the peer-reviewed literature and gray literature screening was conducted using Scopus, Web of Science, and institutional repositories to identify CSA-related initiatives. In addition, an online survey (using the CAWI: Computer-Assisted Web Interview approach) powered using google-form comprising 30 questions (both closed- and open-ended) was administered to CSA stakeholders across 20 countries between September 2021 to February 2022, yielding an average of 30 valid responses per country. The CAADP-XP 4 project national focal points served as entry for national data collection using CAWI questionnaire provided, and for which they were trained before data collection. Data collected were related to CSA initiatives, their objectives, achievements and impacts supported by documented evidence. CSA-related initiatives here are referred to as projects or programs, policy/regulation initiatives, research/academy project, multi-stakeholder/innovation platform and network/set of practices or initiatives.

- CSA stakeholders’ consultative meetings: an online consultation meeting was organized per country (making a total of 20 national consultative meetings) to re-check the validity of the databases together with the focal points and coordination team. Afterwards, two online regional stakeholders’ engagement meetings were organized (one for West African region and the second for the Central Africa region).

- Secondary data collection: Secondary data on funding, sectoral focus, and geographic distribution were extracted from validated project documents collected during the survey and stakeholder focus group meeting, as well as donor reports covering the period 2015–2025.

- Data consolidation and analysis: All datasets were harmonized, cleaned, and triangulated to ensure consistency and reliability prior to analysis. National databases were bulked for the 20 countries and served as regional database for the analysis, mainly conducted using descriptive statistics. Spatial analysis and Maps were made using QGIS. Output per country was prepared based on the following:

- An overview of the implementation of CSA-related initiatives in each country:

- ○

- Initiatives and thematic targeted according to agricultural sub-sectors (crop production, livestock production, fisheries production, forestry, value-added chain).

- ○

- Impacts of the initiatives on production, communities, natural resources, and climate change.

- Lessons learned and gaps analysis in CSA initiatives identified for each country.

- Possible CSA policy orientations for each country.

2.3. Limitations

3. Results

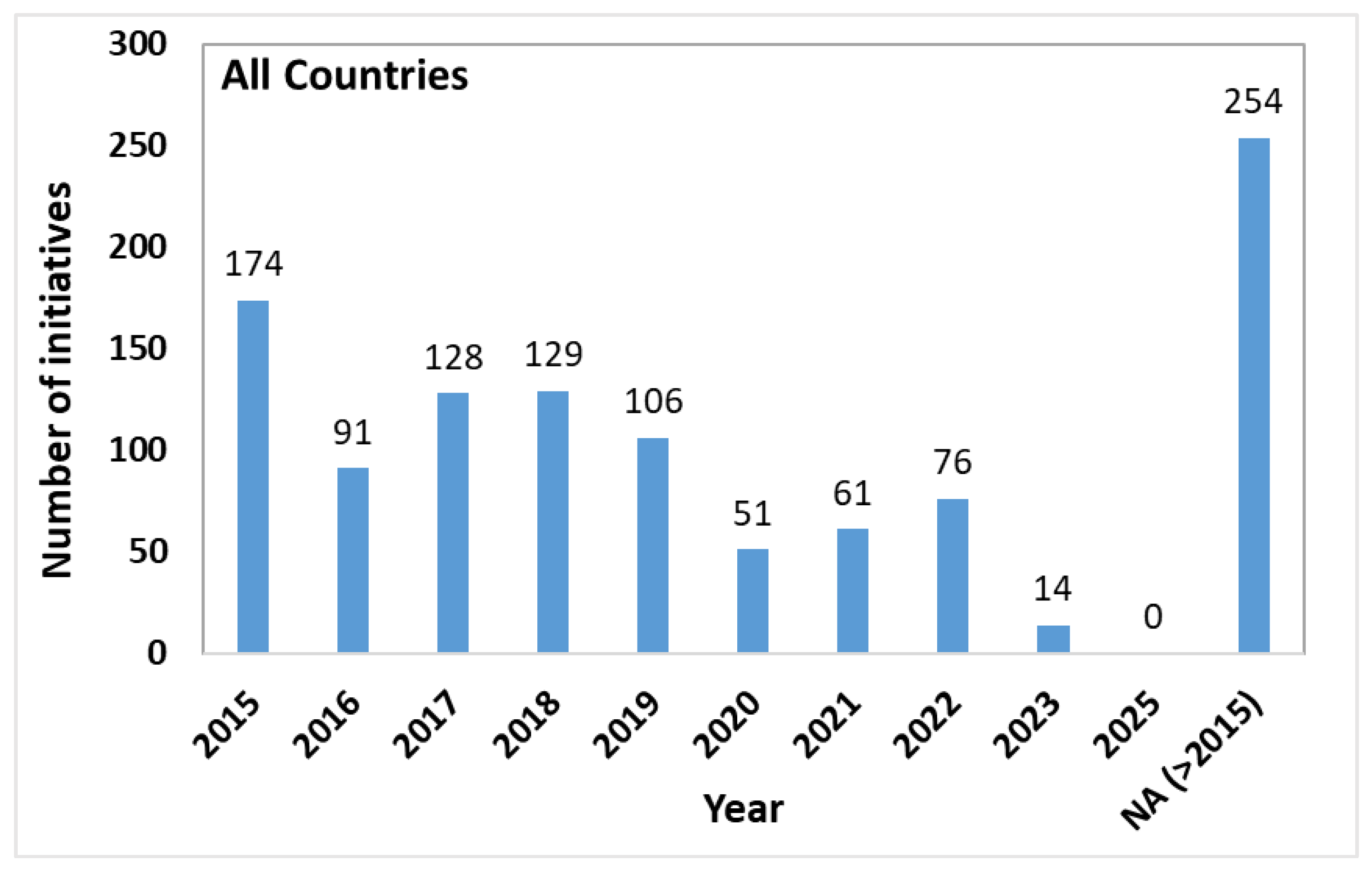

3.1. Overview of CSA Initiatives in WCA Countries

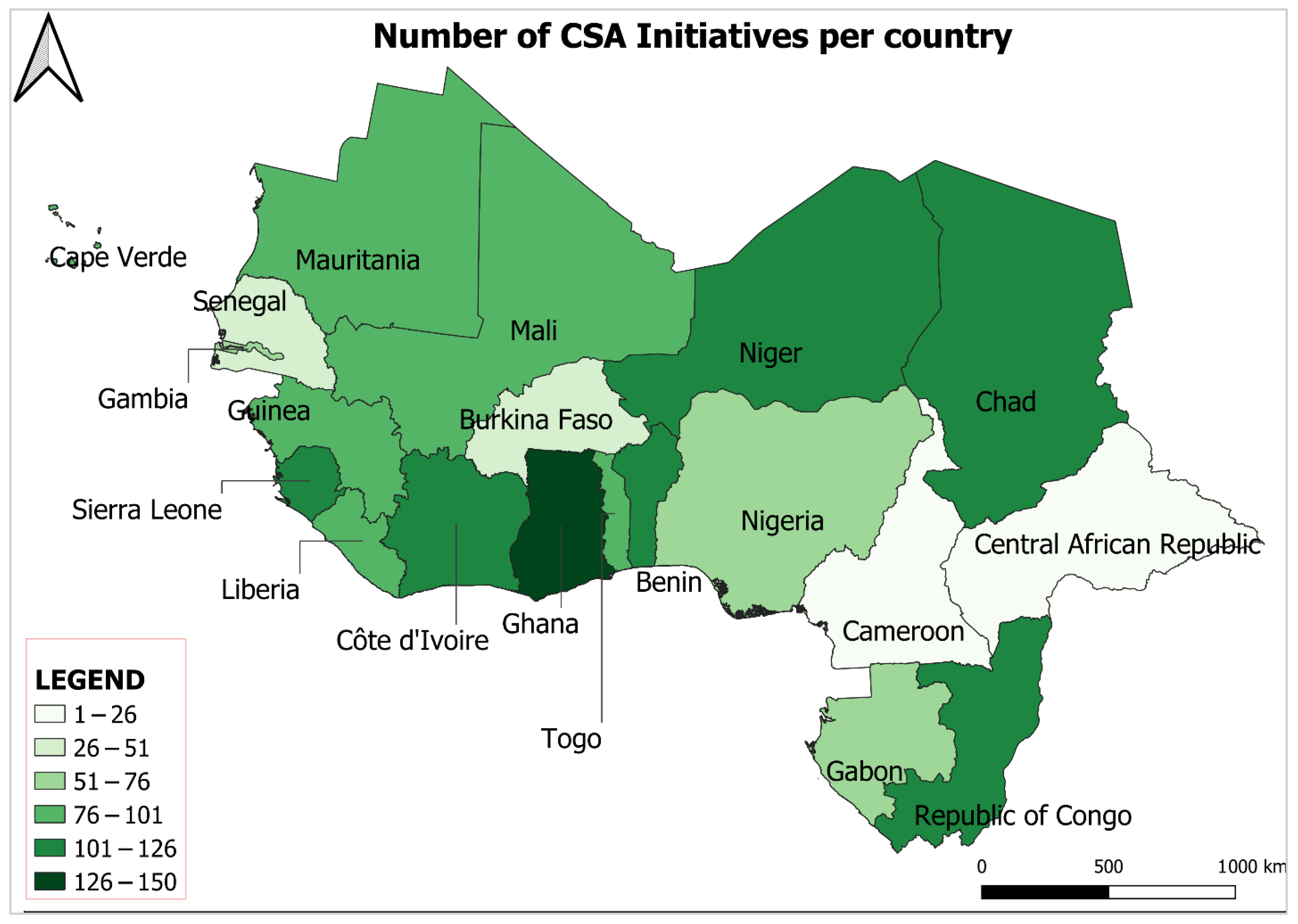

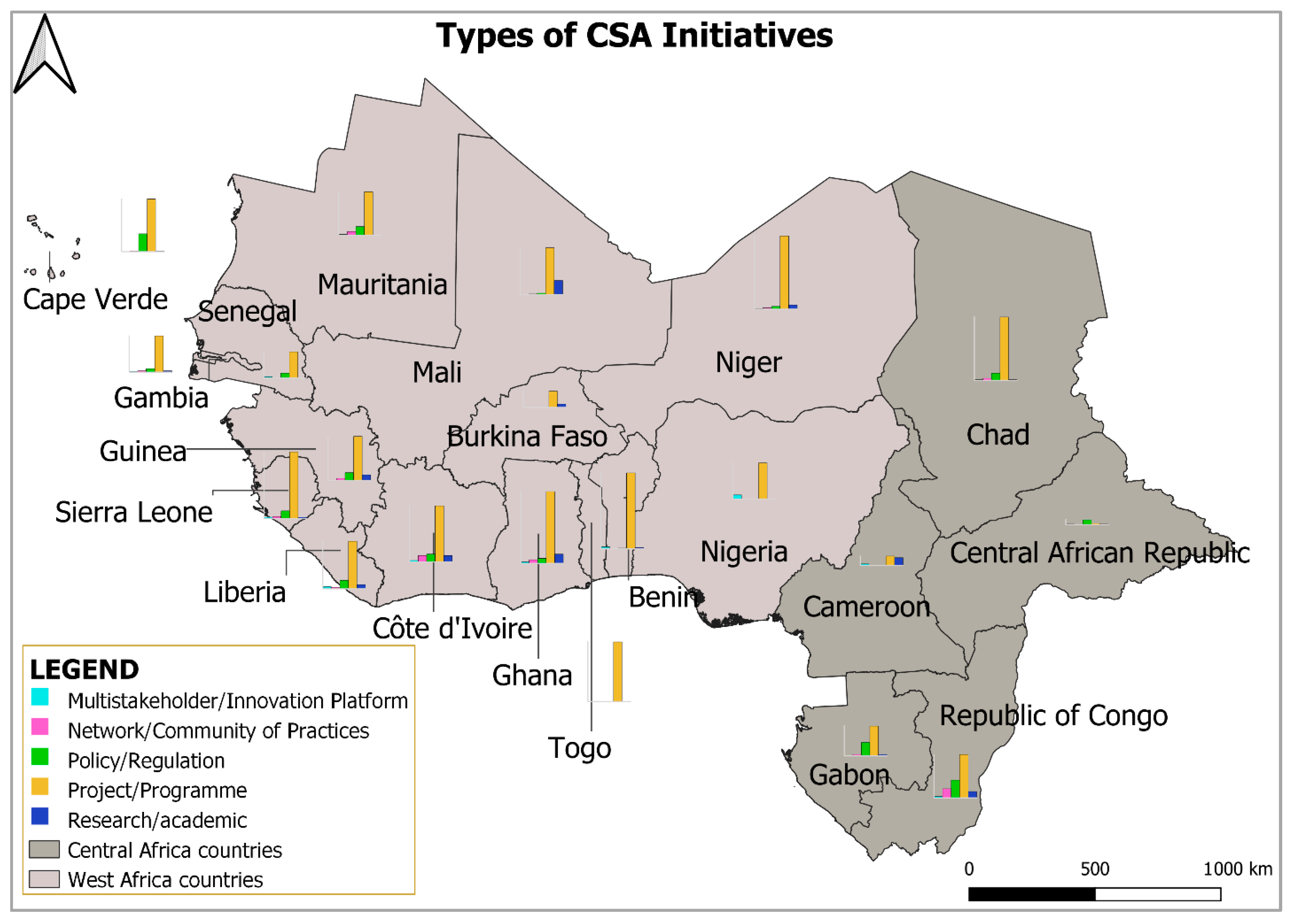

3.1.1. Spatial Distribution of CSA Initiatives in WCA

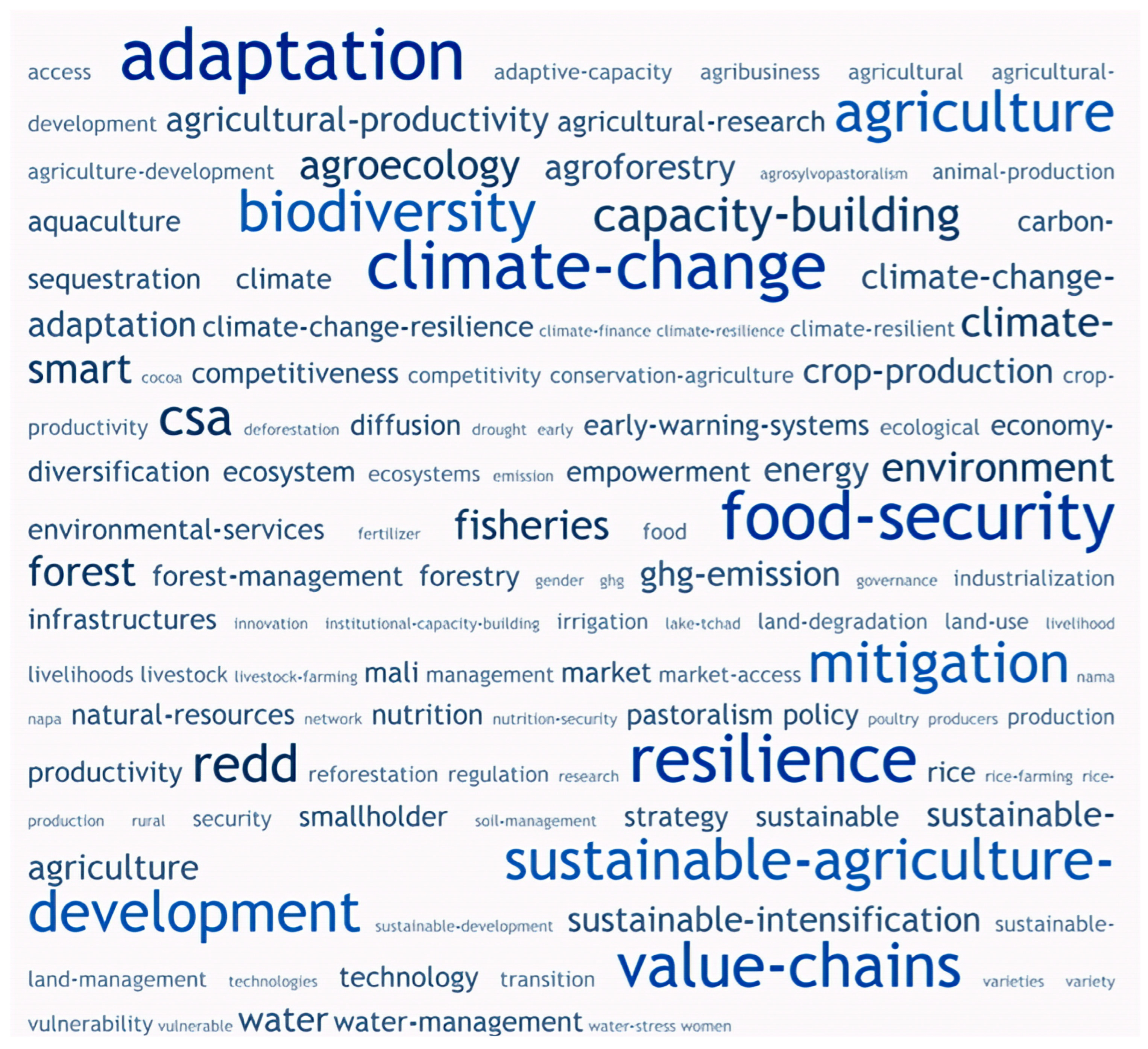

3.1.2. Major Motivations Area of Investments of the CSA Initiatives

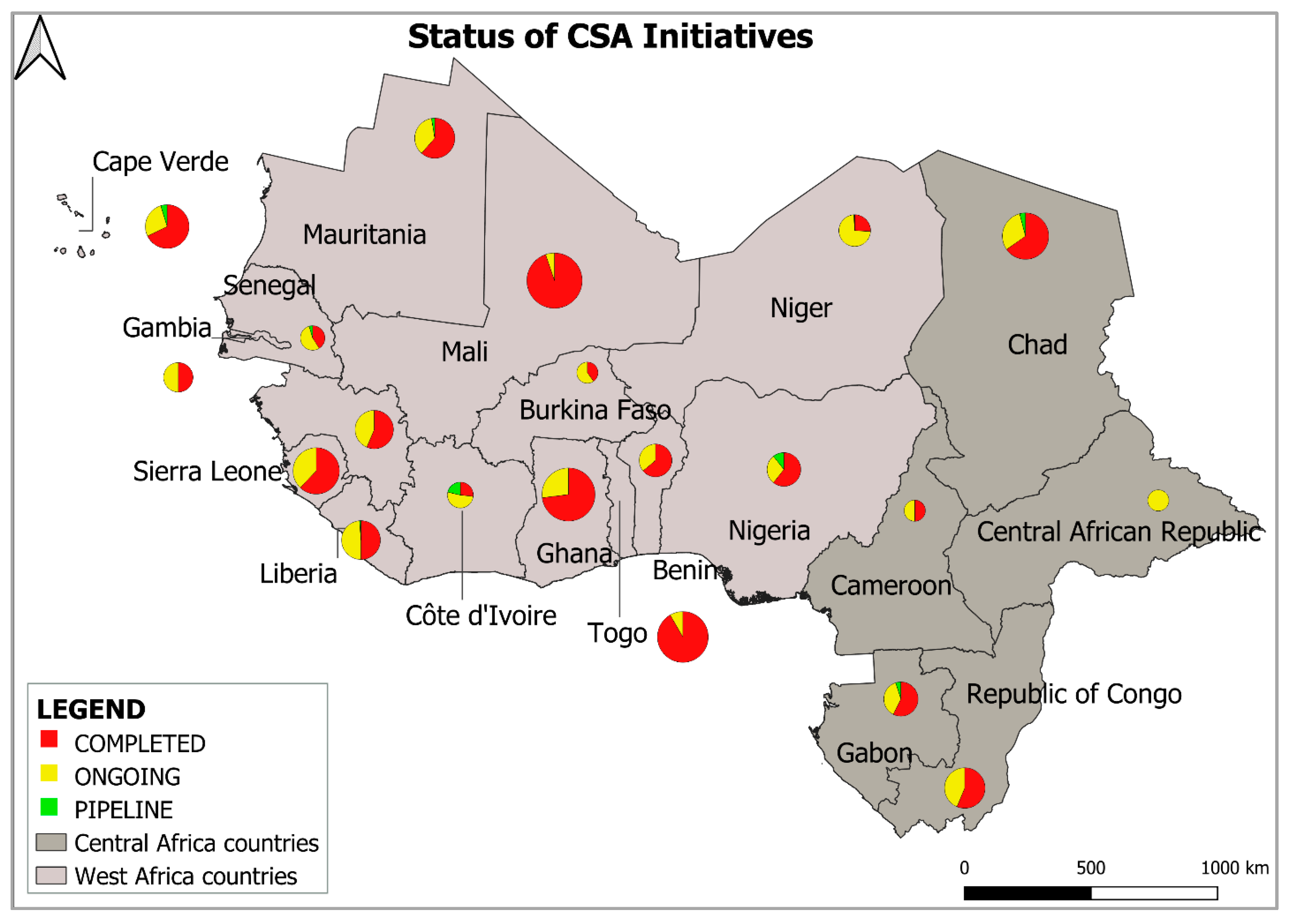

3.1.3. Status of the CSA Initiatives

3.1.4. Categorization of the CSA Initiatives

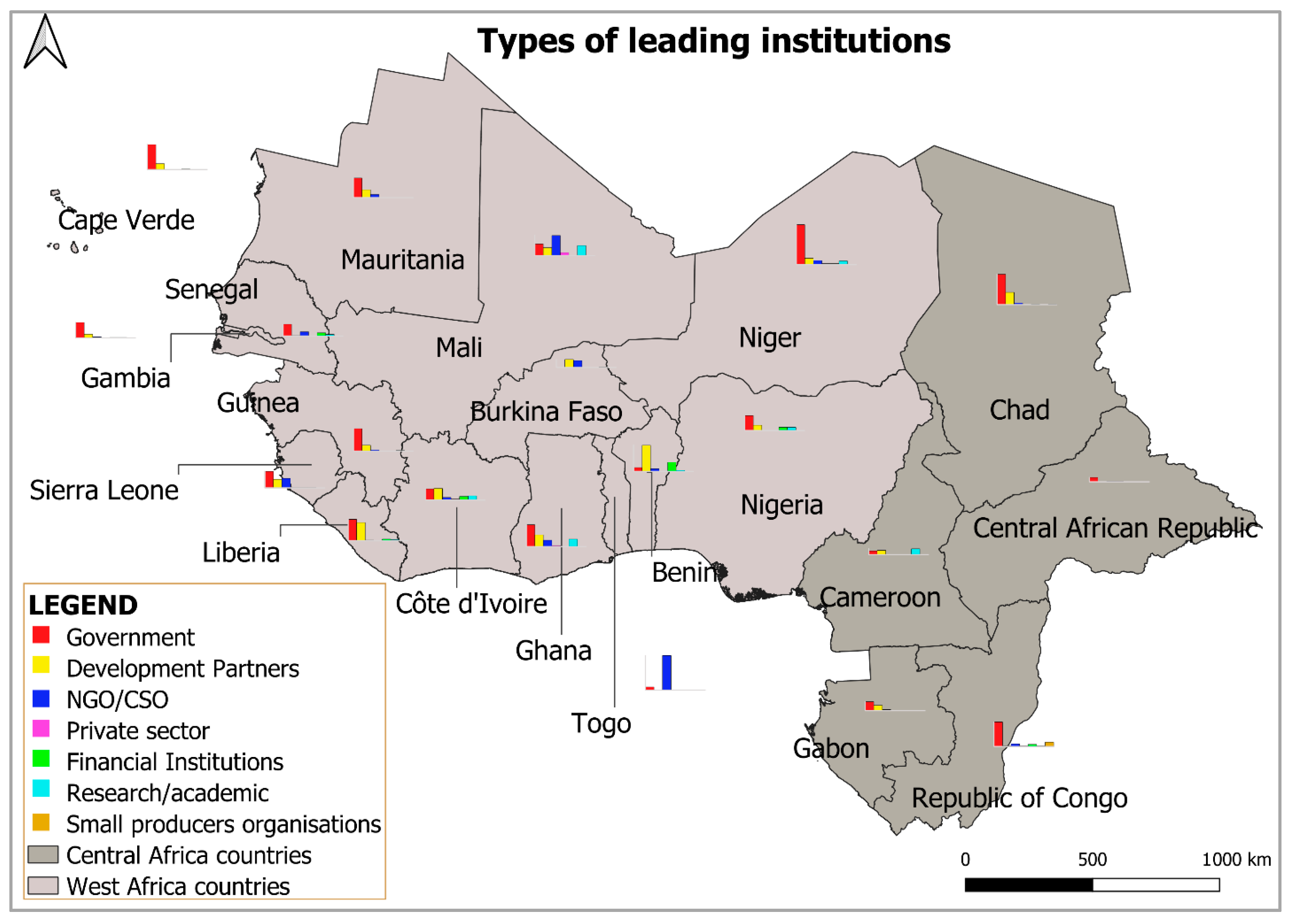

3.1.5. Implementing Institutions

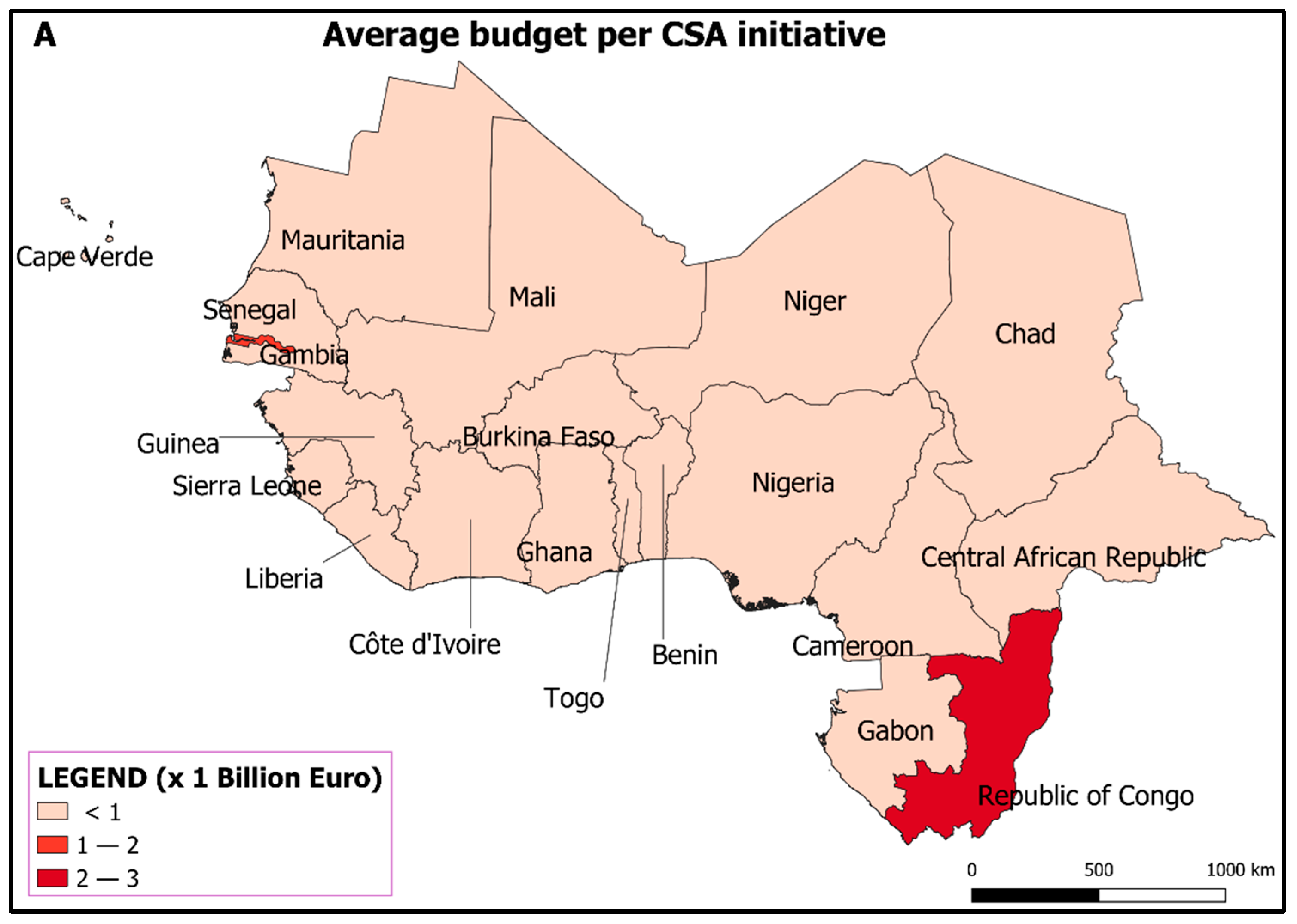

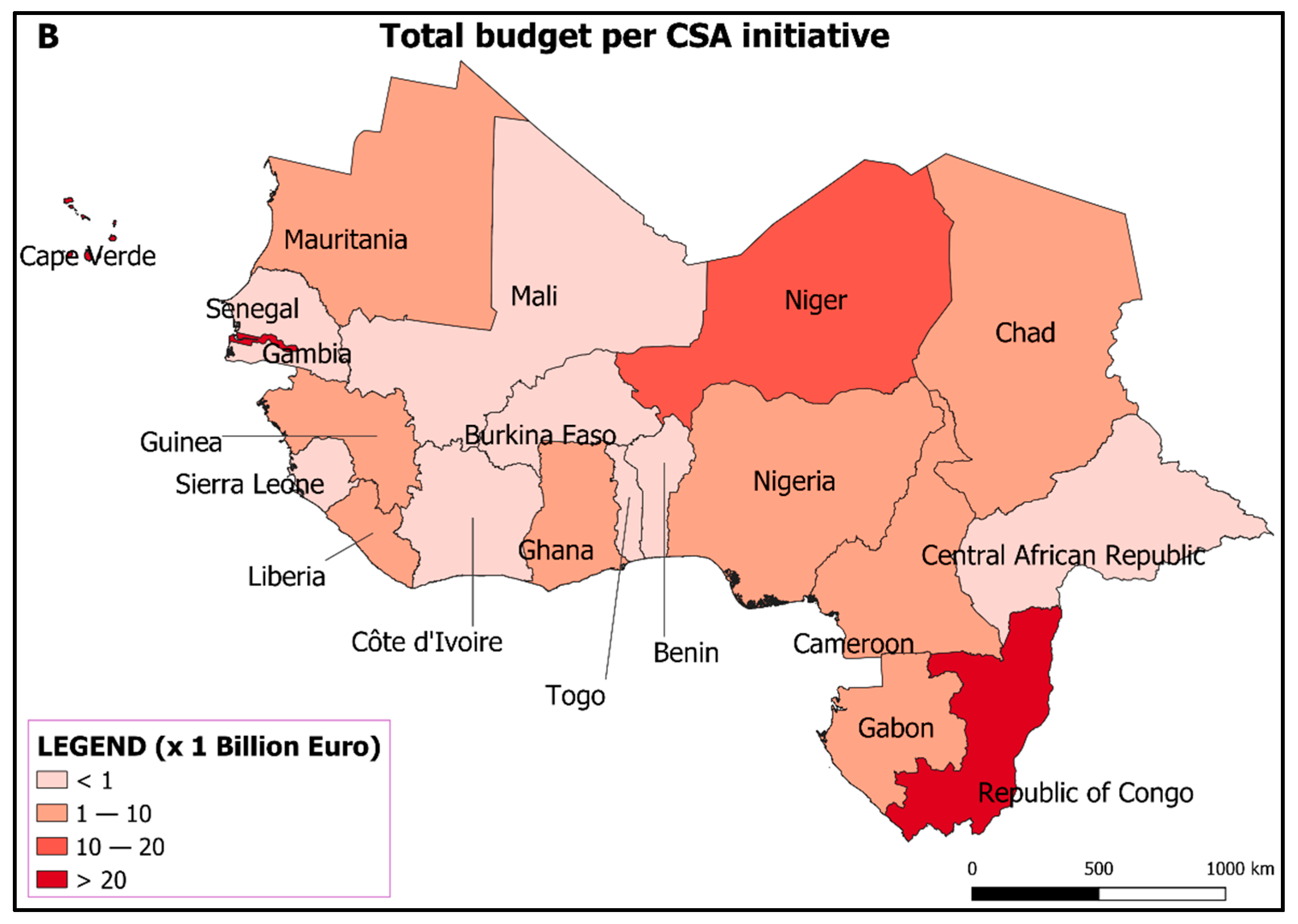

3.1.6. Financial Resources

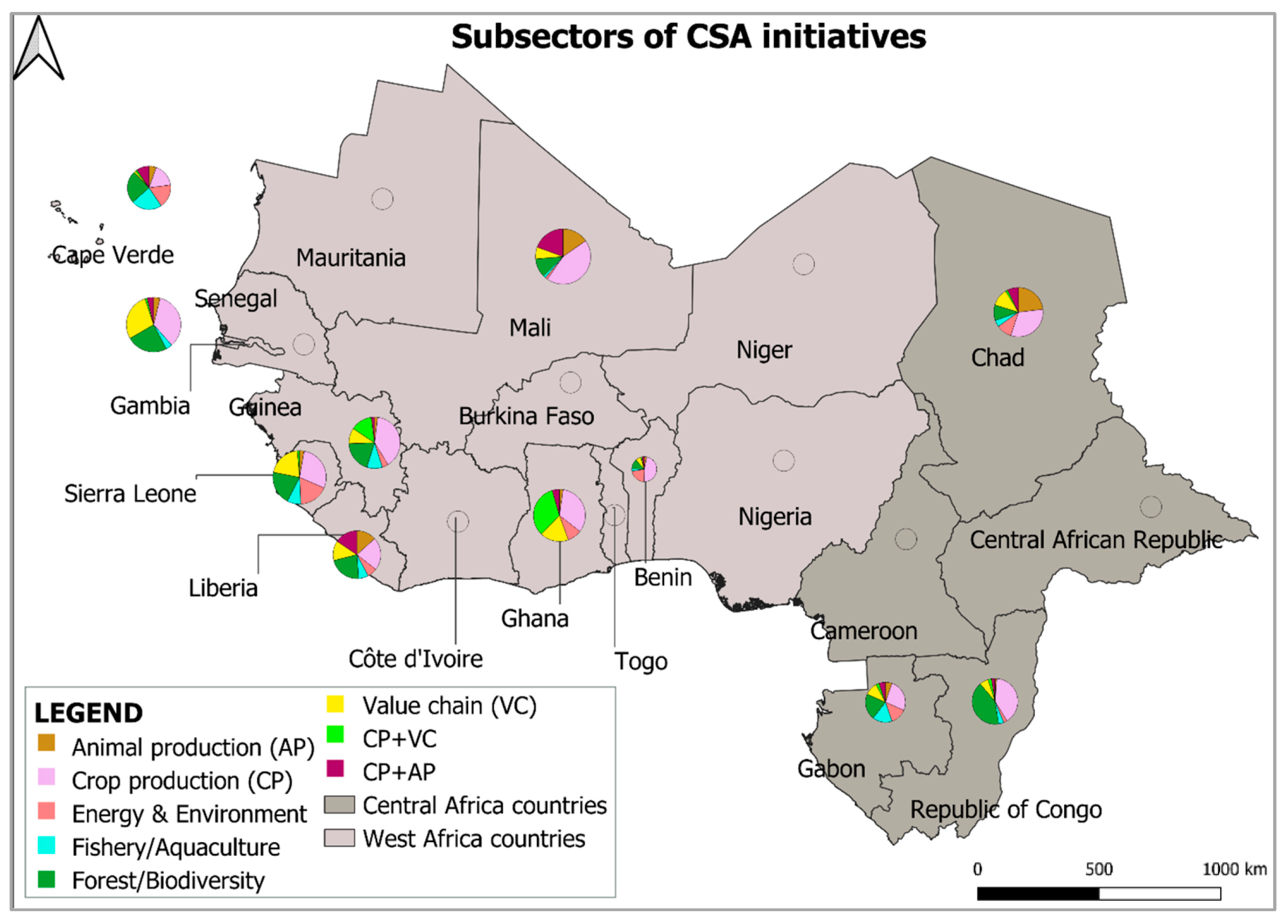

3.2. Agricultural Sub-Sectors and Thematic Areas Targeted by the CSA Initiatives

- (i)

- Crop Production (CP);

- (ii)

- Animal Production (AP);

- (iii)

- Aquaculture and fishing (AF);

- (iv)

- Energy and Environment (EE);

- (v)

- Forestry and Biodiversity (FB) and;

- (vi)

- Value-added chains, Access to markets and financing (VAF).

3.3. Impacts of CSA Initiatives on Production, Natural Resources and Community Resilience

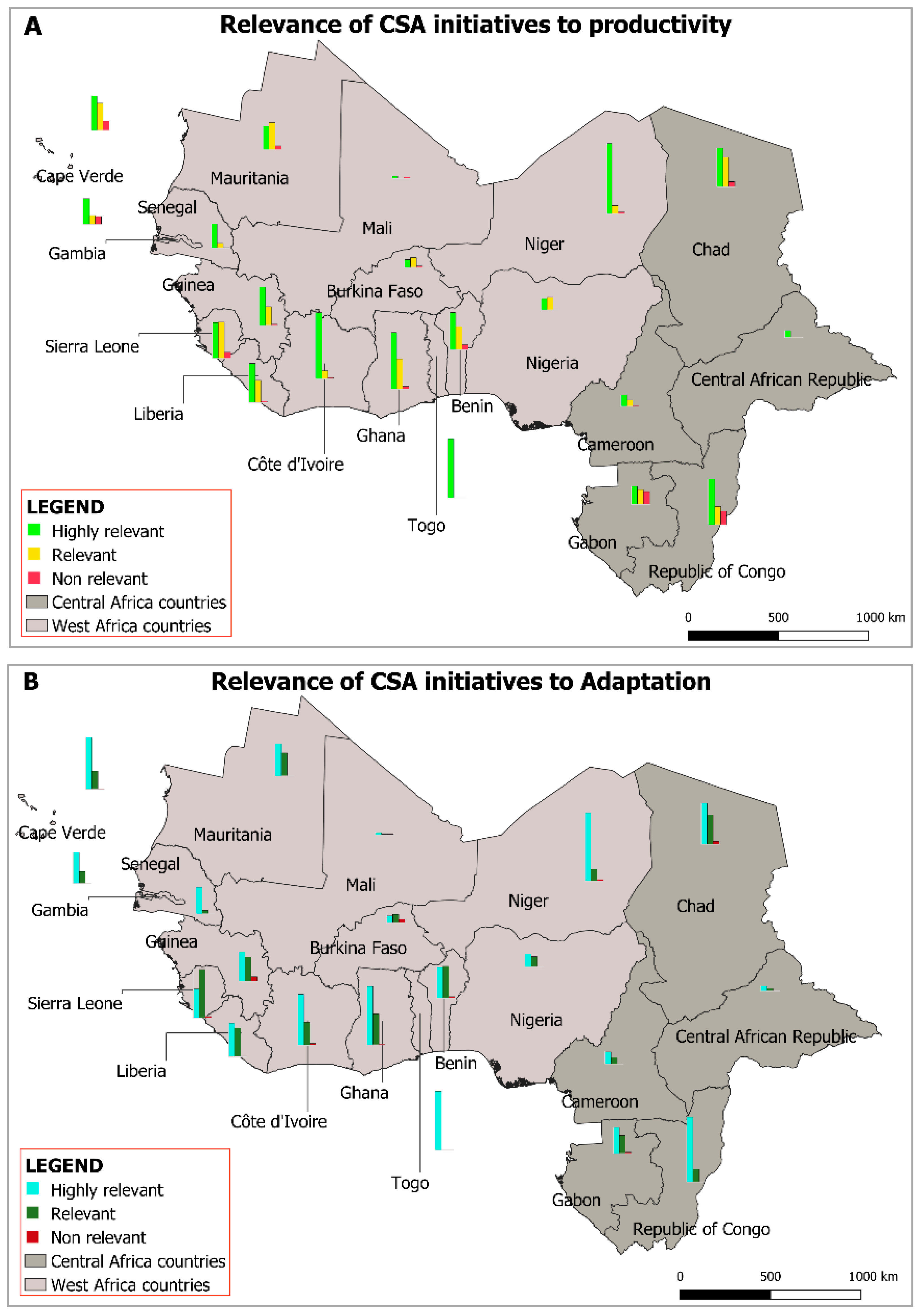

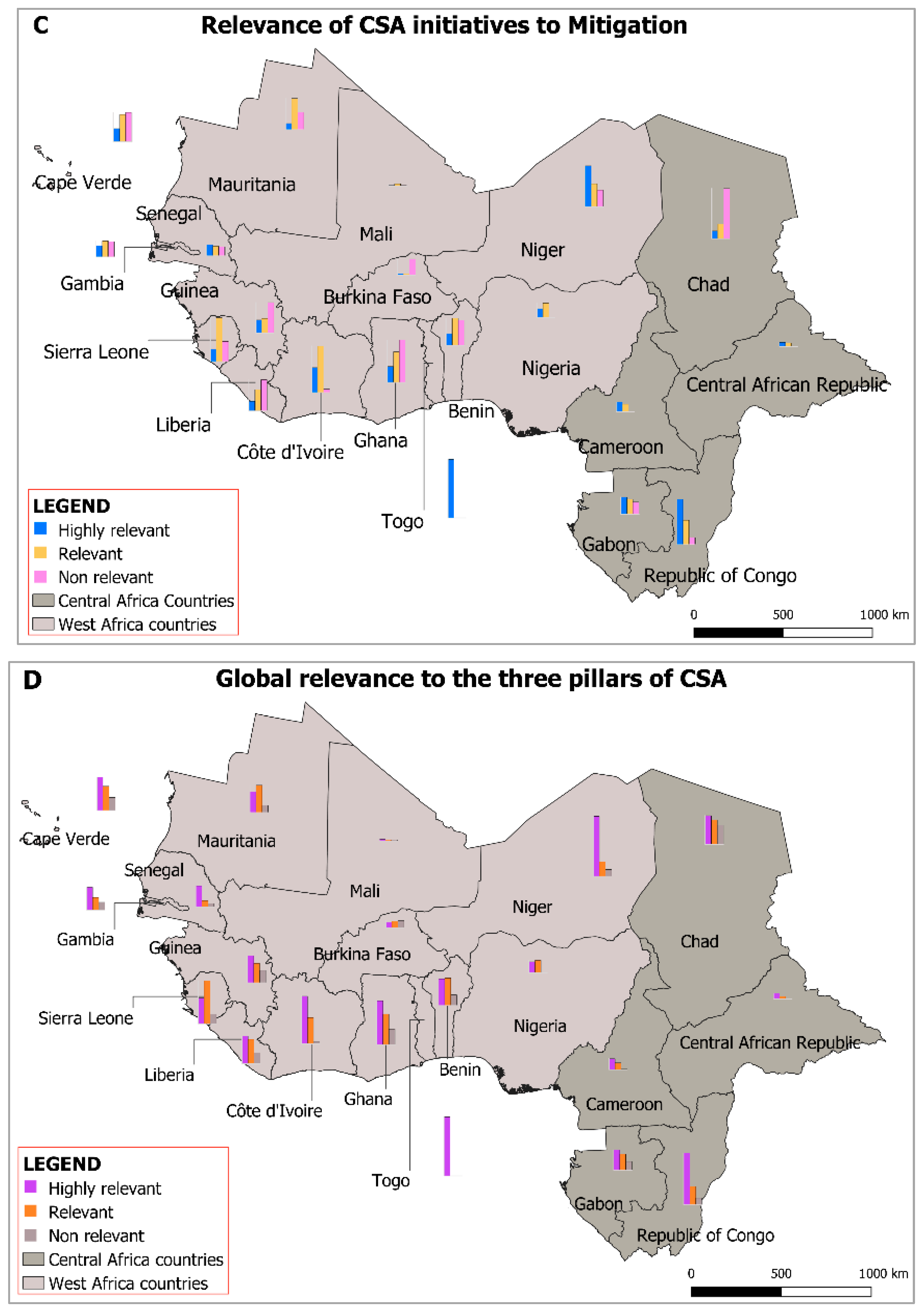

3.3.1. Climate Smartness and Relevance of the Initiatives

- (i)

- Productivity and food safety;

- (ii)

- Adapting to climate change and;

- (iii)

- Mitigating the effects of climate change.

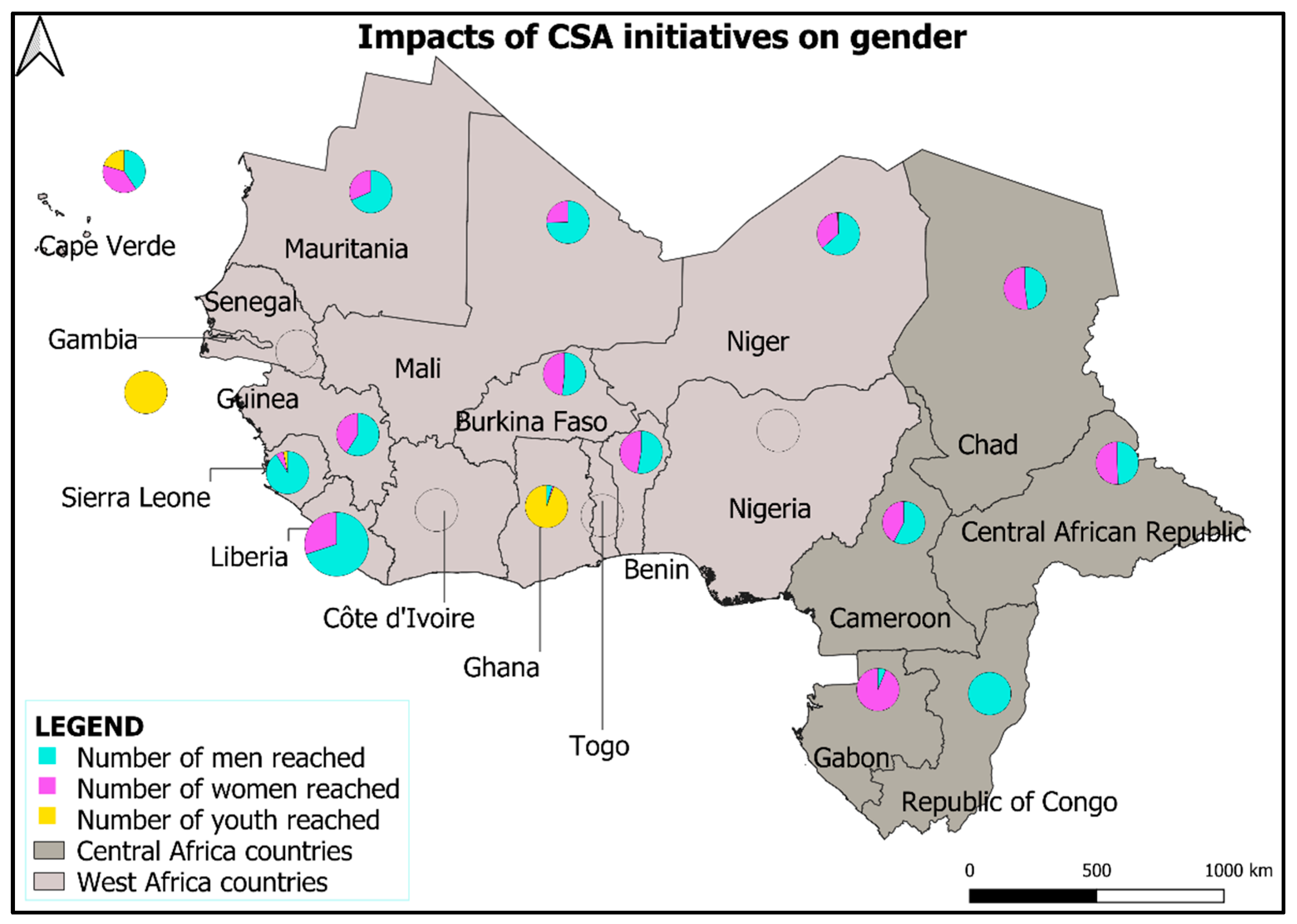

3.3.2. Gender-Related Impacts

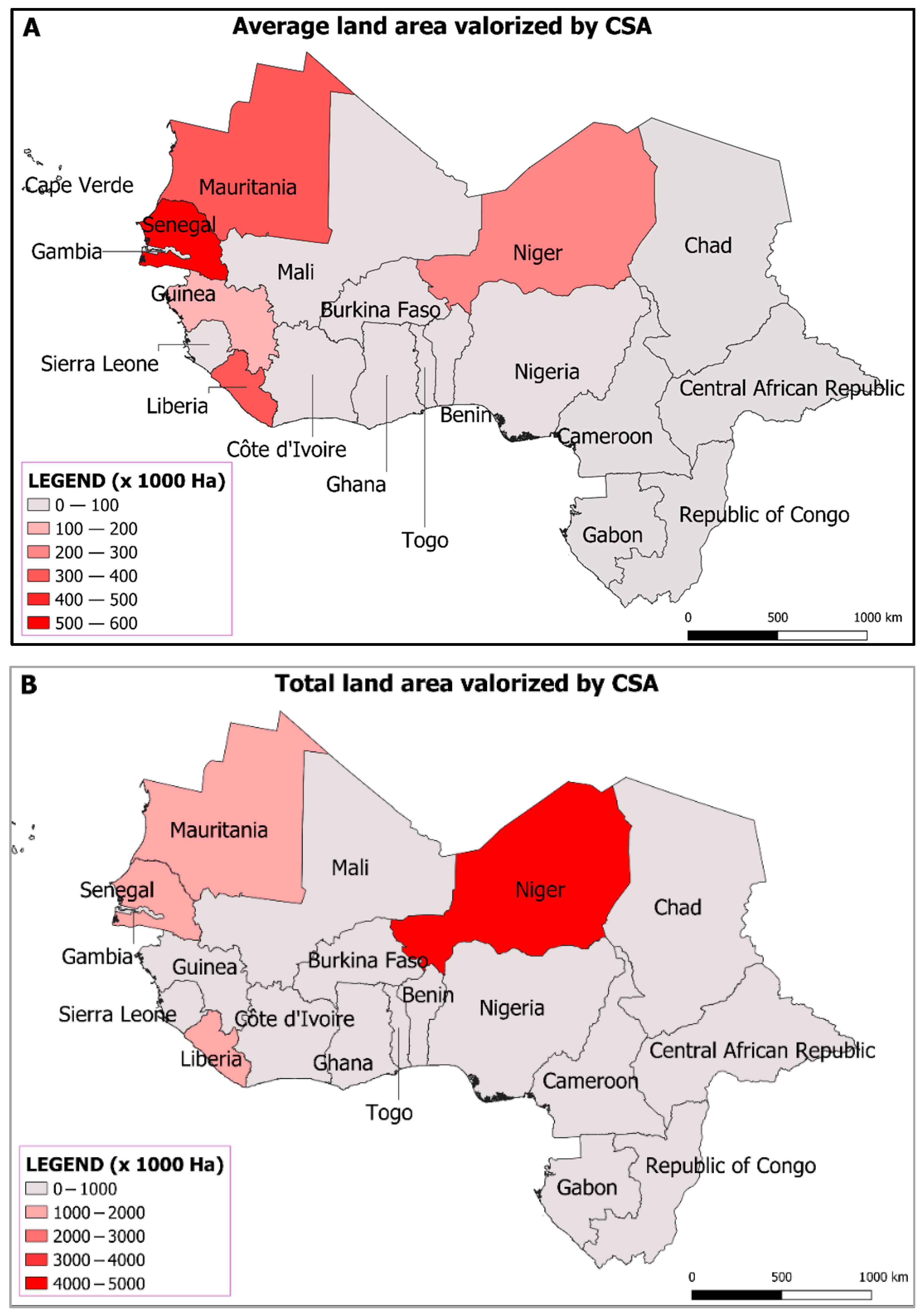

3.3.3. Surface Area of Reclaimed Farmland Under CSA Initiatives

3.4. Lessons Learned and Gaps Analysis

3.4.1. Gaps Analysis

- CSA initiatives in the form of innovation platforms, networks and cooperations, as well as scientific research projects, are very poorly represented, even though they play a vital role in energizing and consolidating the achievements of projects/programs. While scientific research would effectively support the understanding of CSA mechanisms and achievements, the identification of sustainable options and practices in package form (combining practices into a technological package), the designing and testing of new CSA technologies, and the documentation and valorization of CSA actions. Refs. [21,22] have already highlighted the importance and role of research as the backbone for successful implementation of innovative CSA initiatives. Also rare are policy-oriented programs that would constitute the coordinating guideline for CSA actions and initiatives in WCA. The observed disconnection between research outputs and policy uptake reflects structural weaknesses in CSA national innovation systems, including limited science–policy interfaces, weak demand articulation by policymakers, and fragmented institutional mandates. Ref. [23] had already underscored the importance of interaction between science, development, and policy in CSA implementation process. On the other hand, CSA practices and technologies have high potential in overcoming humanitarian challenges that may result from political situations, terrorism, and climate change in West Africa [24].

- CSA initiatives are very rare in sub-sectors such as animal production, value chain improvement, access to markets and financing, and energy and environment. This same observation has already been made by [24,25], who identified more potential CSA practices in the crop production sub-sector than the others.

- Women benefit very little from the implementation of the CSA initiatives listed and hence are not much involved in the CSA initiatives. Meanwhile, the role of women and the need to take them into account in agriculture and particularly in CSA initiatives has been demonstrated by several scientific studies [26,27,28].

- Private organizations (NGOs/CSOs) are in the minority when it comes to implementing CAS initiatives. Similarly, they invest very little in CSA. As for the public sector, its contribution to funding remains low (around 10%) and could therefore be improved. Public–private partnerships could also make a significant contribution to the financing, design, and implementation of CSA initiatives.

- In general, over 90% of the initiatives are geared towards improving productivity and achieving food security, as well as climate change adaptation strategies, rather than mitigation, while CSA itself advocates a perfect symbiosis between its three pillars of productivity, adaptation, and mitigation.

3.4.2. Lessons Learned

- -

- Little attention paid to the mitigation pillar.

- -

- A larger budget for the environment and energy (EE) and crop production (CP) sub-sectors.

- -

- Few initiatives underway.

- -

- Very few CSA initiatives dedicated to research, innovation platforms or practice networks.

- -

- Little consideration for gender.

3.5. Policy Orientations for Accelerating CSA Implementation in WCA

- -

- Short-term actions: strengthen extension services, improve technology awareness, support pilot financing mechanisms.

- -

- Medium-term actions: develop national CSA investment plans, harmonize standards, strengthen public–private partnerships.

- -

- Long-term actions: institutionalize CSA in national development strategies, integrate mitigation incentives, and establish regional monitoring frameworks.

- -

- Development of a CSA country profile for certain WCA countries such as Burkina-Faso, Cameroon, Congo, Gabon, Guinea, Liberia, Mauritania, Sierra Leone, Central African Republic, and Togo, as well as a national CSA strategy and action plan for the coming years in countries that have not yet established one.

- -

- Elaboration of a legal and regulatory framework to support the implementation of CSA initiatives, including legislation on the accessibility of agri-inputs, agricultural financing and credit, agricultural insurance, land tenure and public–private partnerships in the agricultural sector, could expedite the implementation of climate-smart agriculture in WCA.

- -

- Creation and management of a directory/repository of the best-bet CSA practices and technologies for the region.

- -

- Setting up an innovation platform on a regional scale to enable the agricultural actors involved in CSA to discuss, exchange, and find appropriate solutions to the difficulties encountered. These include farmers’ organizations, agricultural cooperatives or groups, the private sector, NGOs, civil society, and the government through research centers involved in agricultural production and technical agricultural services. This should enable the various networks/platforms to be strengthened by learning about, and participating effectively in, what is being done at the level of the climate-smart agriculture alliance (CSA).

- -

- Beyond ordinary farmers’ organizations and farmers cooperatives, the establishment of innovation platforms, networks and purely pro-CSA farmers’ cooperatives could promote effective scaling-up of CSA practices and technologies. State institutions in charge of climate change should facilitate the creation and management of these platforms. Better still, the design of CSA initiatives could be integrated from the outset into agricultural development projects/programs/plans at both national and regional level, to define future regional strategies to be adopted.

- -

- Encouraging scientific research to find sustainable solutions to current challenges in CSA, based on the socio-cultural realities of each region of the country. Research funding is therefore essential. In addition to the first two pillars, these research projects should focus much more on the third CSA pillar, mitigation, and/or combine the three CSA pillars.

- -

- Initiation and implementation of more CSA initiatives in all WCA countries. This recommendation seems to be more imminent in the next two years, to avoid a lack of initiatives towards the end of 2025.

- -

- These initiatives should be geared more towards the animal production, aquaculture and fisheries sub-sectors, energy, environment and value chains, and market access. However, initiatives in the crop production and forestry/biodiversity sub-sectors should be strengthened, especially for the mitigation. This would make it possible to reduce and/or halt greenhouse gas emissions and promote a climate-smart environment. The initiative should be orientated towards mitigation pillar. Sustainable forestry within CSA frameworks should be guided by multiple pillars, including increasing forest cover, enhancing water retention, protecting ecosystem health, improving forest productivity, strengthening monitoring systems, promoting non-productive forest functions, supporting forest-based livelihoods, and fostering intersectoral cooperation between agriculture, forestry, and timber industries.

- -

- Capacity building in the design, formulation, mobilization of financial resources and implementation of CSA projects for the benefit of public agricultural development institutions, research centers, farmers’ organizations, agricultural groups and technical agricultural extension services, in basic infrastructure, equipment and technical tools, environmentally friendly practices, appropriate agricultural technical itineraries and quality human resources. This should enable agricultural actors to benefit from a good awareness of environmentally friendly practices, available agri-inputs, regular technical monitoring of activities and to be well trained in the core principles of climate-smart agriculture. These capacity-building initiatives may be facilitated by adopting the content of the manual on “Formulation and implementation of climate-smart agriculture projects integrated, participatory, and village-based approaches: Training manual and orientation guide” by [29].

- -

- State institutions to strengthen and support private sector actors by setting up a national fund for CSA.

- -

- Development of strategies that encourage collaboration between private-sector actors and those involved in research would increase the share of private-sector investment in research, especially for issues relating to intellectual property on genetic innovations, and the global integration of markets for agricultural inputs and products [30].

- -

- Strategies need to be developed to further engage women and young people in CSA initiatives, not only as beneficiaries but also as co-constructors and actors in the implementation of these initiatives.

- -

- Train and strengthen NGOs agricultural advisory staff in the implementation of CSA initiatives.

- -

- In addition to external funding, strengthening internal trade, mobilizing domestic financial resources, and encouraging private-sector contributions to investment and operational costs are critical for reinforcing market mechanisms and ensuring the long-term sustainability of CSA initiatives.

- -

- Investing in education systems that foster creativity, problem-solving skills, and technical competencies is essential for strengthening human capital and enabling sustained adoption and adaptation of CSA innovations.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Omokpariola, D.O.; Agbanu-Kumordzi, C.; Samuel, T.; Kiswii, L.; Moses, G.S.; Adelegan, A.M. Climate change, crop yield, and food security in Sub-Saharan Africa. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofori, S.A.; Cobbina, S.J.; Obiri, S. Climate change, land, water, and food security: Perspectives from Sub-Saharan Africa. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 680924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirba, H.Y.; Chimdessa, T.B. Review of impact of climate change on food security in Africa. Int. J. Res. Innov. Earth Sci. 2021, 8, 40–66. [Google Scholar]

- Feliciano, D.; Recha, J.; Ambaw, G.; MacSween, K.; Solomon, D.; Wollenberg, E. Assessment of agricultural emissions, climate change mitigation and adaptation practices in Ethiopia. Clim. Policy 2022, 22, 427–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.S.; Banga, S.S. Global agriculture and climate change. J. Crop Improv. 2013, 27, 667–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Challenges and Opportunities for Mitigation in the Agricultural Sector; Technical Paper; United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change: Bonn, Germany, 2008; 101p. [Google Scholar]

- Kabato, W.; Getnet, G.T.; Sinore, T.; Nemeth, A.; Molnár, Z. Towards climate-smart agriculture: Strategies for sustainable agricultural production, food security, and greenhouse gas reduction. Agronomy 2025, 15, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azadi, H.; Moghaddam, S.M.; Burkart, S.; Mahmoudi, H.; Van Passel, S.; Kurban, A.; Lopez-Carr, D. Rethinking resilient agriculture: From climate-smart agriculture to vulnerable-smart agriculture. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 319, 128602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Liu, D.; Huang, R. A review of climate-smart agriculture: Recent advancements, challenges, and future directions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipper, L.; Zilberman, D. A short history of the evolution of the climate smart agriculture approach and its links to climate change and sustainable agriculture debates. Clim. Smart Agric. 2018, 52, 13–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, S.; Amin, A.; Mubeen, M.; Khaliq, T.; Shahid, M.; Hammad, H.M.; Sultana, S.R.; Awais, M.; Murtaza, B.; Amjad, M.; et al. Climate smart agriculture (CSA) technologies. In Building Climate Resilience in Agriculture; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 319–338. [Google Scholar]

- Kpadonou, G.E.; Akponikpè, P.B.I.; Adanguidi, J.; Zougmore, R.B.; Adjogboto, A.; Likpete, D.D.; Sossavihotogbe, C.N.A.; Djenontin, A.J.; Baco, M.N. Quelles bonnes pratiques pour une Agriculture Intelligente face au Climat (AIC) en production maraîchère en Afrique de l’Ouest ? Ann. Univ. Parakou 2019, 3, 31–48. [Google Scholar]

- Abegunde, V.O.; Obi, A. The role and perspective of climate smart agriculture in Africa: A scientific review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barasa, P.M.; Botai, C.M.; Botai, J.O.; Mabhaudhi, T. A review of climate-smart agriculture research and applications in Africa. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyekum, T.P.; Antwi-Agyei, P.; Dougill, A.J.; Stringer, L.C. Benefits and barriers to the adoption of climate-smart agriculture practices in West Africa: A systematic review. Clim. Resil. Sustain. 2024, 3, e279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanogo, K.; Touré, I.; Arinloye-Ademonla, D.; Dossou-Yovo, E.R.; Bayala, J. Factors affecting the adoption of climate-smart agriculture technologies in rice farming systems in Mali. Smart Agric. Technol. 2023, 5, 100283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negera, M.; Alemu, T.; Hagos, F.; Haileslassie, A. Determinants of adoption of climate smart agricultural practices among farmers in Bale-Eco region, Ethiopia. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, E. Farm households’ adoption of climate-smart practices in subsistence agriculture: Evidence from Northern Togo. Environ. Manag. 2021, 67, 949–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anuga, S.W.; Gordon, C.; Boon, E.; Surugu, J.M.I. Determinants of climate smart agriculture adoption among smallholder food crop farmers in Ghana. Ghana J. Geogr. 2019, 11, 124–139. [Google Scholar]

- Westermann, O.; Förch, W.; Thornton, P.; Körner, J.; Cramer, L.; Campbell, B. Scaling up agricultural interventions: Case studies of climate-smart agriculture. Agric. Syst. 2018, 165, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenwerth, K.L.; Hodson, A.K.; Bloom, A.J.; Carter, M.R.; Cattaneo, A.; Chartres, C.J.; Hatfield, J.L.; Henry, K.; Hopmans, J.W.; Horwath, W.R.; et al. Climate-smart agriculture global research agenda: Scientific basis for action. Agric. Food Secur. 2014, 3, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torquebiau, E.; Rosenzweig, C.; Chatrchyan, A.M.; Andrieu, N.; Khosla, R. Identifying climate-smart agriculture research needs. Cah. Agric. 2018, 27, 26001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zougmoré, R.B.; Partey, S.T.; Totin, E.; Ouédraogo, M.; Thornton, P.; Karbo, N.; Sogoba, B.; Dieye, B. Science–Policy Interactions for Climate-Smart Agriculture Uptake; CCAFS Working Paper No. 265; CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS): Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kpadonou, G.E.; Ganyo, K.K.; Segnon, A.C.; Lamien, N.; Zougmoré, R.B. Potential of Agricultural Technologies and Innovations to Overcome Humanitarian Challenges Caused by Climate Change in West Africa; AICCRA Report; Accelerating Impacts of CGIAR Climate Research for Africa (AICCRA): Accra, Ghana, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yo, T.; Adanguidi, J.; Nikiema, A.; De Ridder, B.; Akponikpè, I. Pratiques et Technologies Pour une Agriculture Intelligente Face au Climat (AIC) au Bénin; FAO: Cotonou, Benin, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Oyawole, F.P.; Shittu, A.; Kehinde, M.; Ogunnaike, G.; Akinjobi, L.T. Women empowerment and adoption of climate-smart agricultural practices in Nigeria. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Stud. 2020, 12, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, S.; Huyer, S. A Gender-Responsive Approach to Climate-Smart Agriculture; GACSA/FAO/CGIAR-CCAFS Practice Brief; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- WBG; FAO; IFAD. Gender in Climate-Smart Agriculture. Module 18, Gender in Agriculture Sourcebook; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Akponikpè, P.B.; Kpadonou, G.E.; Zakari, S.; Adjogboto, A.; Orou Barre Fousseni, I.; Segnon, A.C.; Zougmoré, R.B. Formulation and Implementation of Climate-Smart Agriculture Projects; CIAT: Cali, Colombia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Save and Grow: A Policymaker’s Guide to the Sustainable Intensification of Smallholder Crop Production; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kpadonou, G.E.; Ganyo, K.K.; Allakonon, M.G.B.; Ngaido, A.; Diallo, Y.; Lamien, N.; Akponikpe, P.B.I. An Overview and Lessons Learned from the Implementation of Climate-Smart Agriculture (CSA) Initiatives in West and Central Africa. Sustainability 2026, 18, 1351. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031351

Kpadonou GE, Ganyo KK, Allakonon MGB, Ngaido A, Diallo Y, Lamien N, Akponikpe PBI. An Overview and Lessons Learned from the Implementation of Climate-Smart Agriculture (CSA) Initiatives in West and Central Africa. Sustainability. 2026; 18(3):1351. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031351

Chicago/Turabian StyleKpadonou, Gbedehoue Esaïe, Komla K. Ganyo, Marsanne Gloriose B. Allakonon, Amadou Ngaido, Yacouba Diallo, Niéyidouba Lamien, and Pierre B. Irenikatche Akponikpe. 2026. "An Overview and Lessons Learned from the Implementation of Climate-Smart Agriculture (CSA) Initiatives in West and Central Africa" Sustainability 18, no. 3: 1351. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031351

APA StyleKpadonou, G. E., Ganyo, K. K., Allakonon, M. G. B., Ngaido, A., Diallo, Y., Lamien, N., & Akponikpe, P. B. I. (2026). An Overview and Lessons Learned from the Implementation of Climate-Smart Agriculture (CSA) Initiatives in West and Central Africa. Sustainability, 18(3), 1351. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031351